Abstract

Background

In the past decade, the countries that emerged from the Soviet Union have experienced major changes in the inherited Soviet model of health care, which was centrally planned and provided universal, free access to basic care. The underlying principle of universality remains, but coexists with new funding and delivery systems and growing out-of-pocket payments.

Objective

To examine patterns and determinants of health care utilization, the extent of payment for health care, and the settings in which care is obtained in Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine.

Methods

Data were derived from cross-sectional surveys, representative of adults aged 18 and over in each country, conducted in 2001. Multistage random sample of 18,428 individuals, stratified by region and area, was obtained. Instrument contained extensive data on demographic, economic, and social characteristics, administered face-to-face. The analysis explored the health seeking behavior of users and nonusers (those reporting an episode of illness but not consulting).

Results

In the preceding year, over half of all respondents visited a medical professional, ranging from 65.7 percent in Belarus to 24.4 percent in Georgia, mostly at local primary care facilities. Of those reporting an illness, 20.7 percent of all did not consult although they felt they should have done so, varying from 9.4 percent in Belarus to 42.4 percent in Armenia and 49 percent in Georgia.

The main reason for not seeking care was lack of money to pay for treatment (45.2 percent), self-treatment with home-produced remedies (32.9 percent), and purchase of nonprescribed medicine (21.8 percent). There are marked differences between countries; unaffordability was a particularly common factor in Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova (78 percent, 70 percent, 54 percent), and much lower in Belarus and Russia.

In Georgia and Armenia, 65 percent and 56 percent of those who had consulted paid out-of-pocket, in the form of money, gifts, or both; these figures were 8 percent and 19 percent in Belarus and Russia respectively and 31.2 percent overall.

The probability of not consulting a health professional when seriously ill was significantly higher among those over age 65, and with lower education. Use of health care was markedly lower among those with fewer household assets or a shortage of money, and those dissatisfied with their material resources, factors that explained some of the effects of age. A lack of social support (formal and informal) decreases further the probability of not consulting, adding to the consequences of poor financial status.

The probability of seeking care for common conditions varies widely among countries (persistent fever: 56 percent in Belarus; 16 percent in Armenia) and home remedies, alcohol, and direct purchase of pharmaceuticals are commonly used. Informal coping strategies, such as use of connections (36.7 percent) or offering money to health professionals (28.5 percent) are seen as acceptable.

Conclusions

This article provides the first comparative assessment of inequalities in access to health care in multiple countries of the former Soviet Union, using rigorous methodology. The emerging model across the region is extremely diverse. Some countries (Belarus, Russia) have managed to maintain access for most people, while in others the situation is near collapse (Armenia, Georgia). Access is most problematic in health systems characterized by high levels of payment for care and a breakdown of gate-keeping, although these are seen in countries facing major problems such as economic collapse and, in some, a legacy of civil war. There are substantial inequalities within each country and even where access remains adequate there are concerns about its sustainability.

Keywords: Utilization, access, Soviet Union, inequalities, out-of-pocket payments

A decade after the transition from communism, health systems in the countries that emerged from the Soviet Union have moved, at different speeds, away from the Soviet model of health care. The Soviet system sought to achieve universal, free access to basic health services, centrally planned according to strict norms with the goal of delivering services of uniform quality in all parts of the Soviet Union. Although it made considerable progress toward this goal, in reality, it was never fully achieved. Thus, in 1987, there were more than twice as many physicians per thousand population (5.7 versus 2.7) in Georgia than in Tajikistan, and infant mortality varied five-fold among the 15 republics, from 11.3 per 1,000 births in Latvia to 56.4 in Turkmenistan (Rowland and Telyukov 1991). In addition, although the Soviet health care system was often seen as monolithic, there were several parallel systems run by other ministries, for example, for the defense forces and KGB, although they were relatively unimportant numerically, with the Ministry of Health in Moscow responsible for 96 percent of hospital beds and 94 percent of ambulatory care in the U.S.S.R. in the late 1980s (Peoples Economy of the U.S.S.R. in 1989 1999). However there was some diversity among facilities under the control of the Ministry of Health, with those attached to major enterprises, such as factories, often receiving considerable subsidies from their associated enterprise while facilities for the Communist Party elite in Moscow, also under the control of a section of the Ministry of Health, received substantially higher levels of funding. Finally, in part reflecting difficulties in communications and supply, individual accounts by health professionals suggest that facilities were often less well developed in isolated rural areas, especially in the far north where populations were nomadic, although despite the enormous problems involved, some basic services were always maintained in these areas. Yet, in most respects, a physician moving from one part of the U.S.S.R. to another would be familiar with the overall operation of the system.

The events that accompanied the break up of the Soviet Union made it inevitable that this system would change, for two reasons. First, in many countries there was a widespread rejection of the Soviet model, with its symbolic association with the communist system. Second, in many countries, the economic collapse caused by the disruption of production and trading relationships and, in some cases, civil disorder, exacerbated by a widespread break down in the power of the state, meant that government revenues were no longer able to sustain the inherited system (Shishkin 1999).

The systems that have emerged vary considerably although all countries have formally retained the principle of universal access to care. Changes have been both planned and unplanned. Planned changes include a move to more pluralistic systems of both funding and delivery. New systems of funding have included shifts to health insurance and expansion of out-of-pocket payments (Field 1999). Planned reforms of health care delivery include decentralization of the organization of the system.

However, in many countries it is the unplanned changes that have been more important in shaping the new system. They include a substantial increase in informal payments in some countries (Lewis 2002) and a breakdown of existing systems for health system governance.

While there is extensive anecdotal evidence that access to care has suffered in this region, some small-scale studies indicating how particular groups, such as those with chronic diseases, have suffered considerably (Hopkinson et al. 2004; Telishevska, Chenet, and McKee 2001). Secondary analysis of survey data revealed that 0.6 percent of households in Kyrgyzstan and 3.9 percent in Ukraine faced catastrophic expenditure due to health costs in one year (Xu et al. 2003), and a recent study in Tajikistan documents large inequalities in access to care related to affordability (Falkingham 2004). However, there is, to our knowledge, no systematic research comparing how changes in different ex-Soviet countries have affected access to health care. This study begins to fill this gap by examining patterns of health system utilization in eight former Soviet Union countries, exploring the socioeconomic determinants of utilization and the extent of payment for health care, looking in detail at those who, despite illness, do not have access health care.

Objective

The objective of this article is to assess the extent to which universal access to care has been maintained in eight of the countries that emerged from the U.S.S.R. It is part of a larger study on living conditions, lifestyle, and health (LLH), undertaken within the European Union's Copernicus program. The study included surveys in eight of the fifteen newly independent states: Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine (Institute for Advanced Studies 2003). Of the remaining countries, three (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) are now members of the European Union and in the other four (Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) survey research is extremely difficult and we were unable to identify local partners.

In this article we examine the health-seeking behavior of two groups of people. The first are those who consult a health care provider (regardless of whether they have had experienced an illness), looking at the situations in which they consult, where, whether they pay for these services, and their views on when it is appropriate to seek care. The second group are those who, despite experiencing illness, did not consult, even though they felt they should have done so.

Methods

In the autumn of 2001 quantitative cross-sectional surveys were conducted in eight countries (Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine) by local organizations with expertise in survey research, and using standardized methods (Living Conditions, Lifestyle and Health Project n.d.). The methods have been described in detail elsewhere (Pomerleau et al. 2003). In brief, each survey sought to include representative samples of the national adult population aged 18 years and older, although a few small regions had to be excluded because of geographic inaccessibility, sociopolitical situation or prevailing military actions: Abkhazhia and Osetia in Georgia, the Trans-Dniester region and municipality of Bender in Moldova, and the Chechen and Ingush republics and the autonomous districts located in the far north of the Russian Federation.

Samples were selected using multistage random sampling with stratification by region and area. Within each primary sampling unit, households were selected using standardized random route procedures, except in Armenia where random sampling from household lists was used. Within each household the adult with the nearest birthday was selected for interview.

It was decided to include at least 2,000 respondents in each country, but to boost this number to 4,000 in the Russian Federation, and to 2,500 in Ukraine to reflect the larger and more regionally diverse populations in those countries. The combined dataset contained valid data on health-seeking behavior for 18,428 individuals.

The first draft of the questionnaire was developed in consultation with country representatives from pre-existing surveys conducted in other transition countries and from the New Russia Barometer surveys (Post-Communist Barometer Surveys n.d.) adjusted to the national context. It was developed in English, translated into appropriate national languages, back translated to check consistency, and piloted in each country. The questionnaire covered a wide range of issues related to living conditions, lifestyle, and health, supplemented by an extensive battery of questions on sociodemographic and economic characteristics, experience of and attitudes to political transition, psychosocial characteristics, and social networks and support. This article utilizes responses to questions on decisions to seek care, the circumstances of obtaining care, and coping strategies substituting for formal treatment in the health system.

The questionnaire was administered by trained interviewers using face-to-face interviews conducted in respondents' homes. Statistical analysis was undertaken using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc. 2003).

Results

Utilization Rates

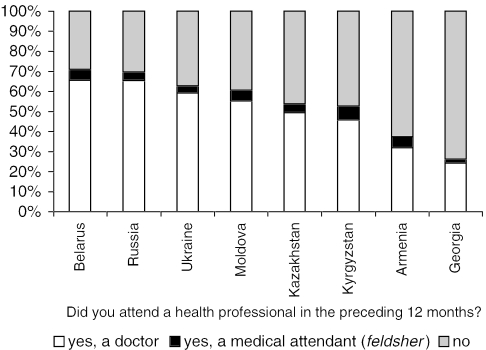

In the preceding 12 months, in the sample as a whole, 52 percent of respondents visited a medical doctor, 5 percent visited a medical assistant (feldsher), and 44 percent did not visit any health professional. When weighted for the differing populations of the countries, the corresponding figures for them as a regional grouping are 61.1 percent, 4.3 percent, and 34.7 percent, respectively. However, the probability of attending a health professional in the previous year varied widely across countries, ranging from 65.7 percent in Belarus to 24.4 percent in Georgia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Probability of Consulting a Health Care Professional in the Preceding Twelve Months, by Country

Affordability and Access to Care

The first step in interpreting these figures is to separate those who did or did not experience an episode of illness that they felt justified in consulting a health professional. Overall, of those reporting an illness they felt justified seeking attention, 20.7 percent did not do so. The probability of not seeking attention when it seemed justified varied greatly among countries (Figure 2). Only 9.4 percent did not seek care in Belarus while the corresponding figures were 42.4 percent in Armenia and 49 percent in Georgia.

Figure 2.

Probability of Consulting a Health Care Professional (Physician or Feldsher) in the Preceding Twelve Months, by Country (of Those Reporting an Illness They Felt Justified Attendance)

The reasons cited for not seeking care, including alternative strategies to cope with the illness, among those who reported being ill but not obtaining care (n=2,478), were explored in more detail. Of respondents, 77.8 percent cited one reason, and 21.8 percent two or more reasons for not consulting. The most important reason for not seeking care was lack of money to pay for treatment, at 45.2 percent. Reporting self-treating with home-produced remedies was 32.9 percent and about a fifth (21.8 percent) purchased medicine directly from a pharmacist, without obtaining a doctor's prescription. Reasons such as long waiting times to see a health professional (8.8 percent), or lack of trust in the health system in general or health professionals in particular (7.7 percent) were less common reasons for not consulting.

These aggregate results mask dramatic differences between countries (Table 1). The countries appear to fall into three groups. The first consists of Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova, where unaffordability was particularly common, with 77.5 percent, 70 percent, and 53.6 percent, respectively, of those ill reporting being unable to afford to attend a skilled health worker. In Belarus, and Russia, few of those reporting having been ill said that they had been unable to afford care. Kazakhstan and Ukraine occupied intermediate positions, with about one in three people reporting illness unable to afford care. In most countries the combined percentage of those reporting not seeking care but instead either self-treating or buying something from a pharmacist was similar, with the precise division between the two options varying; the exceptions were Belarus and Kyrgyzstan, where these options were rarely used.

Table 1.

Percentages of Those Reporting Illness Not Seeking Care for Different Reasons

| No Money to Pay | Self-Treatment | Bought Medicine from a Pharmacist | No Trust in Staff Qualification | Visit Takes Too Much Time | Other | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | |

| Armenia | 77.5% | 366 | 24.2% | 114 | 10.0% | 47 | 5.1% | 24 | 1.5% | 7 | 3.2% | 15 |

| Georgia | 70.0% | 332 | 10.3% | 49 | 25.1% | 119 | 1.1% | 5 | 2.7% | 13 | 3.2% | 15 |

| Moldova | 53.6% | 127 | 38.8% | 92 | 21.9% | 52 | 5.1% | 12 | 2.5% | 6 | 3.4% | 8 |

| Kazakhstan | 34.8% | 92 | 43.9% | 116 | 31.8% | 84 | 8.3% | 22 | 11.0% | 29 | 6.1% | 16 |

| Ukraine | 33.9% | 118 | 39.7% | 137 | 20.9% | 72 | 14.2% | 49 | 10.4% | 36 | 11.6% | 40 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 26.4% | 43 | 16.7% | 65 | 16.7% | 27 | – | – | 16.7% | 11 | 100.0% | 6 |

| Russia | 11.0% | 42 | 46.9% | 177 | 26.8% | 101 | 14.1% | 53 | 21.0% | 79 | 17.2% | 65 |

| Belarus | 0.7% | 1 | 47.4% | 65 | 28.5% | 39 | 10.9% | 15 | 20.4% | 28 | 14.6% | 20 |

Note: Each individual can cite more than one reason for not seeking care.

Another perspective on the relationship between health and expenditure can be obtained by asking whether the household had to do without necessary medical services or drugs in the previous year because of affordability. If the figures from Table 1 concerning not seeking treatment because of inability to pay are compared with the percentages reporting that they never have to do without medical care or drugs (Table 2), then there is a generally consistent inverse relationship.

Table 2.

In the Previous Year Did Your Household Have to Do without Medical Services or Drugs (%)?

| Medical Services | Drugs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constantly | Sometimes | Never | Not Applicable | Constantly | Sometimes | Never | Not Applicable | |

| Armenia | 38.0 | 29.6 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 31.6 | 36.5 | 21.7 | 10.3 |

| Belarus | 4.5 | 22.6 | 67.2 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 30.6 | 56.3 | 5.7 |

| Georgia | 10.9 | 62.1 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 7.9 | 66.1 | 16.0 | 10.0 |

| Kazakhstan | 12.9 | 36.7 | 40.9 | 9.6 | 15.2 | 37.7 | 40.7 | 6.5 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 17.4 | 51.0 | 21.6 | 10.1 | 19.9 | 53.3 | 20.8 | 6.0 |

| Moldova | 17.4 | 55.8 | 19.3 | 7.5 | 17.5 | 56.3 | 19.9 | 6.3 |

| Russia | 11.3 | 27.4 | 53.4 | 8.0 | 16.8 | 32.0 | 45.5 | 5.7 |

| Ukraine | 25.3 | 37.3 | 29.2 | 8.2 | 27.4 | 37.9 | 28.5 | 6.2 |

Another perspective can be gained by looking at respondents' experiences in their most recent consultations. Overall, 31.2 percent of those who had consulted paid out-of-pocket, whether in the form of money, gifts, or both. In 3.6 percent of cases a fee was paid, but by the employer, and 65 percent made no contribution. However, the figures vary widely among countries. As expected, the highest probability of making an out-of-pocket payment or a gift was in Georgia and Armenia (65 percent and 56 percent, respectively), with the lowest in Belarus and Russia, at 8 percent and 19 percent respectively (Figure 3). Among those who reported the value of the payment or gift, the median amount was US$6.30.

Figure 3.

Percentage Paying Informally or Making a gift during Most Recent Consultation, by Country

Determinants of Utilization

Those who report being ill but do not consult are of particular interest. To understand their characteristics better, the analysis examined how the probability of not consulting when ill varied with a range of covariates that might be expected to exert an influence on health-seeking behavior (Table 3). The probability of not consulting was highest among those over age 65, those with lower educational attainment, or who were single, in all countries. In most countries those living in rural areas were less likely to obtain care when ill, although the relative difference between those in urban and rural settings varied. There is also a clear relationship with material status, with the probability of consulting when ill increasing as the number of key household assets increased. The probability of consulting also increased with subjective measures of well-being, such as satisfaction with income and material living conditions. These subjective measures have, elsewhere, been found to correlate better with health-related behavior than more “objective” measures of income, a finding that is unsurprising given the widespread informal economy and nonmonetary transactions in this region (Falkingham and Kanji 2000).

Table 3.

Covariates of Being Ill but Not Obtaining Care

| Armenia | Belarus | Georgia | Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Moldova | Russia | Ukraine | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Total N | % | Total N | % | Total N | % | Total N | % | Total N | % | Total N | % | Total N | % | Total N | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 43.0 | 712 | 9.6 | 890 | 49.9 | 637 | 18.9 | 794 | 14.1 | 704 | 16.2 | 789 | 13.0 | 1805 | 19.8 | 1128 |

| Male | 41.4 | 401 | 9.3 | 560 | 47.3 | 330 | 24.7 | 461 | 17.0 | 376 | 19.7 | 554 | 12.4 | 1197 | 19.5 | 640 |

| Age group | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–34 | 29.1 | 251 | 5.5 | 401 | 22.4 | 152 | 15.4 | 435 | 10.4 | 395 | 10.3 | 321 | 7.9 | 825 | 9.6 | 415 |

| 35–49 | 43.3 | 372 | 7.0 | 444 | 42.1 | 271 | 21.6 | 394 | 15.2 | 356 | 16.1 | 436 | 12.4 | 878 | 15.4 | 436 |

| 50–64 | 44.6 | 222 | 12.5 | 319 | 56.3 | 293 | 24.1 | 266 | 17.2 | 163 | 22.1 | 317 | 13.7 | 728 | 24.2 | 466 |

| 65+ | 51.9 | 268 | 15.4 | 286 | 64.1 | 251 | 30.0 | 160 | 24.1 | 166 | 23.8 | 269 | 19.1 | 571 | 28.4 | 451 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||||

| Higher | 30.1 | 219 | 8.4 | 251 | 41.0 | 329 | 13.3 | 286 | 8.0 | 238 | 12.5 | 240 | 9.4 | 669 | 11.7 | 359 |

| Secondary vocational | 39.7 | 282 | 7.8 | 477 | 51.7 | 242 | 22.6 | 452 | 22.3 | 287 | 16.4 | 379 | 11.7 | 948 | 16.6 | 537 |

| Secondary/incomplete higher | 44.6 | 397 | 7.4 | 434 | 55.6 | 306 | 19.1 | 356 | 12.7 | 465 | 14.5 | 330 | 12.7 | 795 | 18.9 | 529 |

| Incomplete secondary | 54.2 | 212 | 15.8 | 279 | 50.0 | 76 | 35.0 | 160 | 23.6 | 89 | 24.8 | 383 | 18.3 | 589 | 34.7 | 329 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 41.3 | 780 | 8.0 | 887 | 46.7 | 630 | 20.6 | 814 | 14.8 | 755 | 16.6 | 915 | 12.7 | 1,856 | 17.6 | 1,046 |

| Single | 30.4 | 102 | 7.5 | 199 | 36.5 | 96 | 15.3 | 183 | 9.2 | 119 | 15.0 | 113 | 8.3 | 422 | 14.0 | 193 |

| Divorced/widowed | 51.5 | 229 | 13.7 | 358 | 60.8 | 232 | 26.4 | 250 | 20.1 | 194 | 21.9 | 311 | 15.7 | 715 | 25.4 | 508 |

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||

| Russian Orthodox | 9.2 | 1,149 | 50.2 | 852 | 18.2 | 1,190 | 12.5 | 2,018 | 19.3 | 1,195 | ||||||

| Muslim | 17.1 | 469 | 12.6 | 785 | ||||||||||||

| Armenian | 42.6 | 974 | ||||||||||||||

| Other | 51.1 | 47 | 10.7 | 131 | 36.7 | 98 | 24.6 | 564 | 21.0 | 238 | 12.2 | 49 | 11.3 | 240 | 17.0 | 200 |

| None | 33.0 | 88 | 10.7 | 159 | 61.5 | 13 | 19.4 | 201 | 25.0 | 48 | 14.8 | 88 | 13.8 | 723 | 21.1 | 356 |

| Urban/rural | ||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 39.1 | 709 | 8.4 | 1075 | 46.4 | 610 | 20.0 | 745 | 15.6 | 550 | 13.4 | 651 | 12.2 | 2,291 | 16.8 | 1,242 |

| Rural | 48.3 | 404 | 12.5 | 375 | 53.5 | 357 | 22.5 | 510 | 14.5 | 530 | 21.7 | 692 | 14.5 | 711 | 26.4 | 526 |

| Possession of assets | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 assets | 19.8 | 101 | 6.5 | 387 | 20.5 | 83 | 12.8 | 219 | 10.5 | 114 | 9.4 | 128 | 8.6 | 765 | 10.8 | 268 |

| 4 assets | 27.5 | 153 | 5.8 | 326 | 35.6 | 101 | 17.3 | 226 | 3.5 | 113 | 8.7 | 184 | 9.2 | 588 | 11.9 | 268 |

| 3 assets | 40.0 | 235 | 11.4 | 352 | 44.0 | 150 | 22.4 | 339 | 15.3 | 216 | 13.0 | 284 | 13.5 | 680 | 16.4 | 428 |

| 2 assets | 48.8 | 248 | 10.3 | 214 | 49.2 | 197 | 23.0 | 296 | 16.6 | 223 | 17.4 | 276 | 14.6 | 561 | 21.1 | 383 |

| 1 assets | 44.8 | 221 | 15.5 | 84 | 53.7 | 257 | 30.6 | 111 | 19.5 | 231 | 21.6 | 190 | 18.6 | 258 | 29.7 | 283 |

| No assets | 61.4 | 153 | 21.4 | 56 | 66.9 | 166 | 36.0 | 50 | 17.6 | 182 | 31.3 | 252 | 30.4 | 112 | 47.2 | 53 |

| Material living conditions | ||||||||||||||||

| Money enough for durables/luxuries | 3.6 | 28 | 6.4 | 313 | 24.6 | 69 | 12.8 | 274 | 7.2 | 181 | 11.6 | 138 | 6.6 | 693 | 9.9 | 181 |

| Money enough for nutrition/basic items | 31.9 | 486 | 9.7 | 969 | 42.5 | 433 | 18.8 | 780 | 15.1 | 642 | 15.4 | 805 | 12.9 | 1867 | 15.9 | 1002 |

| Money not enough even for nutrition | 53.4 | 581 | 11.1 | 126 | 59.6 | 441 | 44.4 | 180 | 21.2 | 245 | 25.9 | 367 | 22.1 | 403 | 28.8 | 541 |

| Self-assessed financial status | ||||||||||||||||

| Very good/good | 11.1 | 27 | 9.7 | 134 | 15.0 | 20 | 12.4 | 186 | 7.4 | 204 | 7.6 | 92 | 5.9 | 239 | 9.7 | 72 |

| Average | 31.0 | 393 | 7.1 | 900 | 37.8 | 299 | 18.5 | 736 | 14.3 | 588 | 14.3 | 615 | 10.8 | 1682 | 14.9 | 685 |

| Bad | 49.4 | 419 | 12.8 | 328 | 55.1 | 432 | 30.2 | 291 | 20.3 | 236 | 21.6 | 449 | 16.3 | 876 | 20.0 | 654 |

| Very bad | 51.5 | 266 | 18.6 | 59 | 57.9 | 195 | 48.6 | 35 | 28.6 | 49 | 26.2 | 168 | 21.6 | 185 | 30.5 | 328 |

| Freedom of choice & control over life | ||||||||||||||||

| High | 41.8 | 576 | 9.2 | 741 | 40.1 | 464 | 18.5 | 627 | 15.2 | 659 | 16.0 | 582 | 10.5 | 1361 | 18.4 | 636 |

| Medium | 42.4 | 347 | 9.5 | 440 | 59.7 | 283 | 19.4 | 377 | 14.0 | 136 | 15.0 | 386 | 12.8 | 938 | 19.2 | 579 |

| Low | 46.9 | 128 | 7.5 | 160 | 52.8 | 127 | 32.1 | 190 | 15.4 | 208 | 20.2 | 208 | 16.0 | 487 | 21.3 | 380 |

| Membership in organizations | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 31.1 | 74 | 6.2 | 503 | 37.5 | 48 | 10.3 | 223 | 10.6 | 161 | 11.5 | 287 | 7.3 | 763 | 12.5 | 313 |

| No | 43.2 | 1,039 | 11.2 | 946 | 49.6 | 917 | 23.4 | 1,032 | 15.9 | 919 | 19.3 | 1,056 | 14.6 | 2,233 | 21.2 | 1,453 |

| Support score | ||||||||||||||||

| Extensive | 30.7 | 231 | 7.3 | 586 | 28 | 175 | 12.3 | 407 | 11.5 | 453 | 11.4 | 298 | 8.7 | 971 | 12.4 | 468 |

| Good | 37.7 | 268 | 5.7 | 209 | 41.5 | 130 | 20.9 | 254 | 15.9 | 138 | 15.3 | 249 | 11.2 | 492 | 18.0 | 256 |

| Some | 48.9 | 229 | 11.3 | 151 | 57.1 | 112 | 32.3 | 167 | 15.3 | 137 | 16.0 | 237 | 13.2 | 423 | 24.2 | 219 |

| None | 53.1 | 262 | 13.6 | 213 | 60.6 | 284 | 33.5 | 203 | 19.0 | 200 | 25.6 | 316 | 19.3 | 514 | 24.9 | 405 |

| TOTAL | 42.4 | 2,000 | 9.5 | 2,000 | 49 | 2,022 | 21.0 | 2,000 | 15.1 | 2,000 | 17.7 | 2,000 | 12.8 | 4,006 | 19.7 | 2,400 |

It is also plausible that health-seeking behavior will be influenced by factors related to what has become termed broadly as social capital, including the extent of social support available to the individual. There is some evidence that utilization is less among those with the least social support, for example, those who do not participate in organizations. Perceptions of freedom of choice or control over one's life have less marked relationships with utilization.

Clearly, many of these variables are interrelated. Consequently their influence was explored further by means of logistic regression, using SPSS. The dependent variable was the probability of not consulting a health professional among those reporting having been seriously ill. As no obvious differences among countries were seen in the univariate analyses, at least in terms of the nature of relationship between potential explanatory variables and health-seeking behavior, an aggregated dataset was used. Independent variables to be entered into the model were selected from among the variables listed in Table 3, in the light of the univariate relationships exhibited, and of evidence from literature on the determinants of health-seeking behavior. They were then grouped logically into several broad categories: sociodemographic (sex, age, education, and marital status); financial status (financial resources, number of assets, self-assessed financial status); and social support systems (a composite index of freedom of choice and control over life, membership in organizations, and a composite index of social support). The composite indices were taken from an earlier study using this dataset, looking at responses to transition. Each block was then entered stepwise, with forward selection according to likelihood ratio. Three models were created entering one to three blocks of variables. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Odds Ratios of Being Ill and Obtaining Care: All Countries (Only Variables Included in the Model Shown

| Block 1: Sociodemographic | Blocks 1& 2: Financial Status | Blocks 1, 2, & 3: Urban/Rural | Block 1, 2, 3, & 4: Support Systems | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Male | 1.14 | 1.04–1.26 | 1.13 | 1.03–1.25 | 1.18 | 1.05–1.32 | ||

| p<0.01 | p=0.014 | p<0.01 | ||||||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 35–49 | 1.85 | 1.61–2.12 | 1.48 | 1.28–1.71 | 1.48 | 1.28–1.71 | 1.5 | 1.28–1.76 |

| 50–64 | 2.49 | 2.16–2.86 | 1.75 | 1.51–2.04 | 1.82 | 1.56–2.11 | 1.6 | 1.35–1.9 |

| 65+ | 3.18 | 2.73–3.69 | 1.83 | 1.57–2.13 | 1.98 | 1.69–2.33 | 1.72 | 1.43–2.06 |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.045 | p<0.001 | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Higher | 1.00 | |||||||

| Secondary vocational | 1.33 | 1.16–1.52 | ||||||

| Secondary/incomplete higher | 1.55 | 1.35–1.77 | ||||||

| Incomplete secondary | 1.50 | 1.29–1.74 | ||||||

| p<0.001 | ||||||||

| Assets | ||||||||

| 5 assets | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4 assets | 1.09 | 0.88–1.33 | 1.06 | 0.86–1.3 | 0.96 | 0.78–1.23 | ||

| 3 assets | 1.47 | 1.22–1.76 | 1.43 | 1.18–1.72 | 1.31 | 1.07–1.62 | ||

| 2 assets | 1.66 | 1.38–2.01 | 1.62 | 1.34–1.96 | 1.37 | 1.11–1.69 | ||

| 1 assets | 2.16 | 1.78–2.64 | 2.02 | 1.65–2.47 | 1.61 | 1.28–2.02 | ||

| No assets | 2.92 | 2.35–3.61 | 2.66 | 2.13–3.31 | 2.16 | 1.68–2.77 | ||

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | ||||||

| Wealth | ||||||||

| Money enough for durables/luxuries | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Money enough for nutrition/basic items | 1.30 | 1.07–1.57 | 1.29 | 1.06–1.56 | 1.28 | 1.03–1.59 | ||

| Money not enough even for nutrition | 2.35 | 1.88–2.94 | 2.32 | 1.85–2.9 | 2.26 | 1.76–2.9 | ||

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | ||||||

| Self-assessed financial status | ||||||||

| Very good/good | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Average | 1.32 | 1.02–1.70 | 1.34 | 1.03–1.73 | 1.17 | 0.89–1.54 | ||

| Bad | 1.69 | 1.29–2.21 | 1.77 | 1.35–2.31 | 1.54 | 1.15–2.05 | ||

| Very bad | 2.01 | 1.50–2.68 | 2.14 | 1.6–2.86 | 1.85 | 1.35–2.55 | ||

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | ||||||

| Urban/rural | ||||||||

| Rural | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Urban | 1.22 | 1.10–1.36 | 1.18 | 1.05–1.33 | ||||

| p<0.001 | ||||||||

| Membership in organizations | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | |||||||

| No | 2.21 | 1.86–2.62 | ||||||

| p<0.001 | ||||||||

| Support score | ||||||||

| Extensive | 1.00 | |||||||

| Good | 1.44 | 1.22–1.68 | ||||||

| Some | 1.69 | 1.44–1.99 | ||||||

| None | 1.77 | 1.52–2.05 | ||||||

| p<0.001 | ||||||||

In the model containing sociodemographic variables, the probability of not seeking care increased with age, with those over age 65 being more than three times more likely not to seek care compared to those under age 35. Education was also important, with lower use among those with lower education. Gender and marital status were not independently important. When financial factors were added to the model, the influence of age was reduced. Use of health care was markedly lower among those with fewer assets or shortage of money.

The third model added area of residence, confirming the relative advantage of those in urban areas who, after taking sociodemographic and economic factors into account, were 20 percent more likely to obtain care. The addition of variables related to social support increase explanatory power further, although also reducing the influence of age and financial status. Formal social support, defined as membership in organizations of any kind, is an important determinant of seeking care, as is the composite index of social support, while control over one's life was not important.

Care Settings

In the Soviet system, primary care was provided in two types of facilities: primary health care facilities, which were policlinics in urban areas and health posts in rural settings, each covering specified catchment areas, and in occupational facilities, for those employed in specific sectors of the economy. In six countries, more than 60 percent of those respondents who had received care in the previous year experienced their most recent contact with a health professional in one of these settings, with most contacts taking place in their local facilities (Figure 4). The exceptions were Armenia (53 percent) and Georgia (41 percent). In both of these countries, where as it was shown in Figure 1 the overall probability of consulting was lowest, the explanation seems to be a much lower use of district facilities.

Figure 4.

Location of Most Recent Encounter with a Health Professional

In Georgia, the lower use of district primary care facilities is, to some extent, counterbalanced by a much higher use of private facilities, with 16 percent of last contacts in this sector, compared with a maximum of 6 percent (Kazakhstan) in the other countries.

Utilization in Different Hypothetical Scenarios

The analyses so far have looked at actual behavior in relation to episodes of illness, with the nature of the illness undefined (of necessity, given the vast range of possible conditions and the difficulty of categorizing them for analysis). Another way to assess experience of obtaining care (combining information that respondents will have obtained from their own experiences and those of friends and relations) is to ask what they would do when faced with a range of common health conditions. The situations in which formal medical advice is most likely to be sought include fever lasting more than three days (38 percent), abdominal pain (24 percent), and chest pain (18 percent). Self-treatment, including use of home remedies and alcohol, is especially common in cases of cough or diarrhea, but is widely used for all complaints. Purchase of pharmaceuticals without prescription is also common, especially for headache, bad cough, and diarrhea.

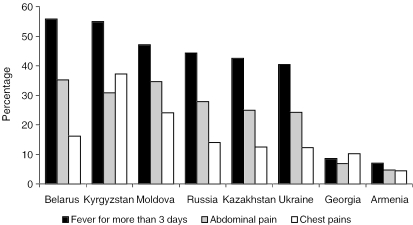

Differences between countries were explored in more detail by focusing only on the three conditions perceived to be most likely to justify seeking care (chest pains, abdominal pains, fever lasting more than three days). The probability of seeking care varies widely among countries. Whereas in Belarus 56 percent would consult with a health professional where there was a prolonged fever, only 16 percent would do so in Armenia (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Would You Consult a Health Professional in the Case of … ?

Health-seeking behavior was explored further by asking what someone should do if they were in need of urgent hospitalization but were told that there was a waiting list of several months. The most frequently mentioned course of action was using informal mechanisms, such as use of connections (36.7 percent) or offering health professionals money (28.5 percent). More transparent strategies such as seeking to persuade hospital staff or lodging a complaint scored much lower on the list. Another 7.8 percent would turn to alternative or traditional healers and 15.2 percent believed there was nothing they could do. The percentage of those saying they would pay or use connections varied (Figure 6) but there was no clear pattern, so that the figures were similar in Belarus and Georgia, despite very different access to care in the two countries as shown by responses to earlier questions.

Figure 6.

What Would You Do if You Needed Hospitalization but Were Told There Was a Long Waiting Time?

Discussion

The creation of the Soviet health care system was, by any standards, a remarkable achievement. Prior to the liberation of the serfs in 1861, health care in rural Russia was virtually nonexistent. The situation began to change in 1864 when Czar Alexander II initiated a system of local government, the Zemstvos, with responsibility for, among other things, health (Krug 1976). Yet while these entities achieved much, by the end of the nineteenth century the situation in many remote areas remained dire, as described eloquently by commentators such as Anton Chekhov (1987).

The Bolsheviks placed a high priority on health, initially emphasizing prevention in the face of widespread epidemics of typhus following the civil war. Over time the Soviet government built up a widespread network of health facilities and, while the quality of care was always better in cities than in rural areas (Davis 1979), it did manage to deliver universal access to basic care to an extremely dispersed population (Field 1957). Yet by the 1980s the weaknesses in the system were already apparent (Field 2002). The failing Soviet economy could not provide the increasingly technical model of health care emerging in the West (Prager 1987). Yet while access to modern, technically sophisticated health care varied, the system still managed to provide at least basic care to all, an achievement that, in many of the newly independent states, would not survive the break-up of the Soviet Union.

This article provides the first detailed comparative assessment of access to health care in a majority of the former Soviet republics. Its strength is its use of standardized questionnaires administered simultaneously, with large samples in eight countries, several of which have been the subject of virtually no such research until now. The samples appear largely representative of national populations in terms of common demographic variables, although there does seem to be a slight underrepresentation of men in Armenia and Ukraine, of the urban population in Armenia, and of the rural population in Kyrgyzstan; and the oldest age groups are slightly overrepresented in Armenia, Moldova, and Ukraine. However, these deviations are minor and unlikely to affect the results significantly. Yet we must also be aware that comparisons with official data may be limited by the failure of some country data to fully capture posttransition migration and other factors (Badurashvili et al. 2001) and we cannot exclude the possibility that, as with all surveys in the former Soviet Union, we will have missed groups living on the margins of society who are especially difficult to reach. Consequently it is plausible that these findings underestimate the scale of problems that exist.

Its weaknesses are common to all population-based surveys of health care utilization. To fully understand the process of seeking health care it is necessary to have detailed information on pretreatment health status as well as utilization. Furthermore, given the many factors other than simply health status that influence whether an individual will seek care for a particular condition, it is important to supplement quantitative data with qualitative research. Such research is being undertaken as part of the larger project within which these surveys were undertaken and will be reported subsequently. Another weakness is the use of 12-month recall periods, necessitated by the need to identify adequate numbers of people reporting illness in each country. Ideally, the samples would have been much larger and would have focused on a period of only four weeks. Another limitation is that respondents defined whether an episode of illness justified seeking health care; although in a survey this is the only feasible approach, clearly the criteria used will be shaped by expectations and experiences. Unsurprisingly, the probability of having an episode of illness that met these self-defined criteria varied, and in the ways that would be expected, with 48 percent of the Georgian sample so responding, compared with 73 percent of the Belarusian sample. It is, of course, impossible to say whether respondents from Belarus are therefore overusing services or Georgians are underusing them; it is, however, clear that the threshold for considering seeking care varies, with the barrier highest in the countries where the system seems to be functioning least well. This also implies that, as with the challenge of including hard to reach populations, the findings underestimate the scale of the problem where the situation is worst. However, the inclusion of questions about the hypothetical circumstances in which it is appropriate to seek care to some extent overcomes this limitation. The surveys also are not sufficiently large to yield meaningful subnational results. For example, the implementation of health insurance has varied among regions in Russia (Twigg 1999) and it is highly likely that similar differences exist elsewhere.

The data confirm the impression that, while some countries have managed to maintain access to some form of care for most people, in others the situation is near to collapsing. In Belarus, a country that has undergone very little economic reform and has retained many features of the Soviet system (Karnitski 1997), albeit in a situation of sustained economic decline and increasing isolation, health services remain affordable for virtually everyone. Two-thirds of households stated that they never had to do without health care because of cost, and this is in a country where the threshold for seeking care is much lower than in other countries. In contrast, in Georgia, a country that has suffered a civil war and where the government is not in control of some regions (Gamkredlidze et al. 2003), only 14 percent of households report never having to do without care because of cost. Access to care also seems to have remained generally affordable in Russia, by far the largest and wealthiest of the countries included. The pattern of affordability of drugs is similar to that of access to care. Problems are less frequent in Russia and Belarus, but few households in Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, or Moldova are entirely free of problems.

When the aggregate figures are broken down according to the characteristics of respondents it is apparent that there are substantial inequalities in each country. Thus, in Georgia and Armenia, among those in the group with fewest household assets, about two-thirds of respondents had not sought care despite being ill because they could not afford it. While the multivariate analysis confirms how, taking account of other variables, those with fewest resources are most disadvantaged, it also shows that financial resources are not the only factor and others, such as social support systems, play a role, an issue that will be returned to later.

In most countries the referral system appears to have remained intact, with most people receiving care in their local or workplace primary care facility. The exception is Georgia, where a relatively high proportion of the most recent visits have been in hospitals. This provides further evidence of the breakdown of the Georgian health system (Gamkredlidze et al. 2003). This impression receives more support from the question on paying for care, with two-thirds of Georgian respondents paying or making a gift during their most recent consultation. Once again, the lowest figure is in Belarus, at fewer than 10 percent. Other work has shown that the phenomenon of informal payment is extremely complex, with its nature varying according to context (Balabanova and McKee 2002). Consequently, it is not possible to understand fully what is happening from a survey such as this. Instead, there is a need for more detailed qualitative and quantitative research on this subject. It is also of interest to note that, despite the considerable variation in the frequency of paying in different countries, when faced with a hypothetical situation of being unable to obtain necessary treatment, the proportion of respondents saying they would either pay or use connections is relatively similar. Earlier work in Russia has shown the importance of using connections to obtain health care, especially among the higher socioeconomic groups, although the situation is not entirely clear-cut, as some less well-off families benefit by having a family member who is, for example, a driver for a senior doctor (Brown and Rusinova 1997). This social stratification is also apparent in the present study. While 25 percent of those with insufficient resources for nutrition would use connections, 53 percent of those with sufficient resources for luxuries would do so. As might be expected, those who are members of organizations are more likely to say they would use connections than those who are not (44 percent versus 35 percent). Unsurprisingly, there is also a difference in the proportion of respondents who would pay, although the gap is narrower, at 24 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

The former Soviet Union is, with sub-Saharan Africa, one of only two major regions where life expectancy is currently declining (McMichael et al. 2004). The Soviet health system, despite its many weaknesses, did achieve basic universal coverage. While some of the Soviet Union's successor countries, such as the three Baltic republics (not included in this study) are now experiencing sustained economic growth and falling mortality, elsewhere the situation has deteriorated considerably and the prospects for the future are poor, with the situation especially adverse in the Caucasus republics (Armenia [Hovhannisyan et al. 2001] and Georgia [Gamkredlidze et al. 2003]). Yet even where the system still seems to be functioning, as in Belarus, there are no grounds for complacency. While recognizing the need for caution in interpreting economic statistics in this region, Belarus's gross national product per capita has fallen by almost two-thirds in a decade; it seems unlikely that its social protection systems can be sustained in the medium term. In Russia, where there has been a relatively successful (at least compared with other post-Soviet republics) transition to health insurance, some vulnerable groups remain without coverage (Balabanova, Falkingham, and McKee 2003). Variations in access to health care received little attention during the Soviet period (Tkatchenko, McKee, and Tsouros 2000) and, posttransition, there has still been relatively little research on how different groups have fared in the face of the changes to health systems in this region, with the notable exception of Russia (Field and Twigg 2000). Yet many of these countries face similar problems and there is room for shared learning. This study seeks to facilitate this process.

Footnotes

We are grateful to all members of the LLH Study teams who participated in the coordination and organization of data collection for this working paper. The LLH Project is funded by the European Community under the FP5 horizontal programme “Confirming the International Role of Community Research” (INCO2-Copernicus; Contract No: ICA2-2000–10031, Project No: ICA2-1999–10074). However, the European Community cannot accept any responsibility for any information provided or views expressed. Dina Balabanova and Martin McKee are members of the U.K. Department for International Development's (DFID) Health Systems Development Programme, within the framework of which these particular analyses were undertaken. The DFID supports policies, programs, and projects to promote international development. The DFID provided funds for this study as part of that objective but the views and opinions expressed are those of the authors alone.

References

- Badurashvili I, McKee M, Tsuladze G, Meslé F, Vallin J, Shkolnikov V. “Where There Are No Data: What Has Happened to Life Expectancy in Georgia since 1990?”. Public Health. 2001;115:394–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanova D, Falkingham J, McKee M. “Winners and Losers: The Expansion of Insurance Coverage in Russia in the 1990s.”. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:2124–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanova D, McKee M. “Understanding Informal Payments for Health Care: The Example of Bulgaria.”. Health Policy. 2002;62:243–73. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J V, Rusinova N L. “Russian Medical Care in the 1990s: A User's Perspective.”. Social Science Medicine. 1997;45:1265–76. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekhov A P. The Island: A Journey to Sakhalin. London: Pimlico; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Davis C. The Economics of the Soviet Health System. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham J. “Poverty, Out-of-Pocket Payments and Access to Health Care: Evidence from Tajikistan.”. Social Science Medicine. 2004;58:247–58. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham J, Kanji S. “Measuring Poverty in Russia: A Critical Review.”. 2000. DFID working paper (available through enquiry@dfid.gov.uk.

- Field M G. Doctor and Patient in Soviet Russia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Field M G. “Reflections on A Painful Transition: From Socialized to Insurance Medicine in Russia.”. Croatian Medical Journal. 1999;40:202–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M G. “The Soviet Legacy: The Past as Prologue.”. In: McKee M, Healy J, Falkingham J, editors. Health Care in Central Asia. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2002. pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Field M G, Twigg J L. Russia's Torn Safety Nets: Health and Social Welfare During the Transition. New York: St. Martin's Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gamkredlidze A, Atun R, Gotsadze G, MacLehose L. Health Care Systems in Transition: Georgia. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Care Systems; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson B, Balabanova D, McKee M, Kutzin J. “The Human Perspective on Health Care Reform: Coping with Diabetes in Kyrgyzstan.”. International Journal of Health Planning Management. 2004;19:43–61. doi: 10.1002/hpm.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovhannisyan S G, Tragakes E, Lessof S, Aslanian H, Mkrtchyan A. Health Care Systems in Transition: Armenia. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Care Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Advanced Studies. EU-Copernikus Project Living Conditions Lifestyle and Health. Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies; 2003. Available at http://www.llh.at. [Google Scholar]

- Karnitski G. Health Care Systems in Transition: Belarus. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Care Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krug P. “The Debate over the Delivery of Health Care in Rural Russia: The Moscow Zemstvo, 1864–1878.”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 1976;50:226–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. “Informal Health Payments in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union: Issues, Trends and Policy Implications.”. In: Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J, Kutzin J, editors. Funding Health Care, European Observatory on Health Care Systems Series. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2002. pp. 184–205. [Google Scholar]

- Living Conditions, Lifestyle and Health Project Available at http://www.llh.at/llh_partners_start.html [accessed December 14, 2003]

- McMichael A J, McKee M, Shkolnikov V, Valkonen V. “Mortality Trends and Setbacks: Global Convergence—or Divergence?”. Lancet. 2004;363(9415):1155–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15902-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples Economy of the USSR in 1989. Moscow: Finances and Statistics Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau. J, McKee M, Rose R, Balabanova D, Gilmore A. “Living Conditions Lifestyles and Health.”. 2003 Work Package no. 26 (working paper no. 10): Comparative health report. Available at http://www.llh.at [accessed July 16, 2003]. [Google Scholar]

- Post-Communist Barometer Surveys. Glasgow: Centre for the Study of Public Policy, University of Strathclyde; Available at http://www.llh.at. [Google Scholar]

- Prager K M. “Soviet Health Care's Critical Condition.”. The Wall Street Journal. 1987 29 January p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland D, Telyukov A V. “Soviet Health Care from Two Perspectives.”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 1991;10(3):71–86. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.10.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin S. “Problems of Transition from Tax-Based System of Health Care Finance to Mandatory Health Insurance Model in Russia.”. Croatian Medical Journal. 1999;40:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS 12.0 for Windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Telishevska M, Chenet L, McKee M. “Towards an Understanding of the High Death Rate among Young People with Diabetes in Ukraine.”. Diabetes Medicine. 2001;18:3–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkatchenko E, McKee M, Tsouros A D. “Public Health in Russia: The View from the Inside.”. Health Policy Planning. 2000;15:164–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twigg J L. “Regional Variation in Russian Medical Insurance: Lessons from Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod.”. Health Place. 1999;5:235–45. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(99)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Evans D B, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray C J. “Household Catastrophic Health Expenditure: A Multicountry Analysis.”. Lancet. 2003;362:111–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]