Abstract

Objective

To develop data collection methods suitable to obtain data to assess the costs, cost-efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of eight types of HIV prevention programs in five countries.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Primary data collection from prevention programs for 2002–2003 and prior years, in Uganda, South Africa, India, Mexico, and Russia.

Study Design

This study consisted of a retrospective review of HIV prevention programs covering one to several years of data. Key variables include services delivered (outputs), quality indicators, and costs.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Data were collected by trained in-country teams during week-long site visits, by reviewing service and financial records and interviewing program managers and clients.

Principal Findings

Preliminary data suggest that the unit cost of HIV prevention programs may be both higher and more variable than previous studies suggest.

Conclusions

A mix of standard data collection methods can be successfully implemented across different HIV prevention program types and countries. These methods can provide comprehensive services and cost data, which may carry valuable information for the allocation of HIV prevention resources.

Keywords: HIV prevention, cost, cost-effectiveness, voluntary counseling and testing, risk reduction

There is wide agreement that an effective response to the global HIV epidemic requires very substantial resources. This consensus has been partially translated into increasing contributions to combat the epidemic (UNAIDS 2004). The need to spend this money efficiently can hardly be overstated: the lives of millions depend upon how effectively available funds are allocated. Available studies on the cost and cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention programs in developing countries are very limited in number, as well as in the range of prevention strategies and geographic settings examined (Marseille, Hofmann, and Kahn 2002).

“Prevent AIDS: Network for Cost-Effectiveness Analysis” (PANCEA), is a three-year, five-country study funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. It has the purpose of providing essential information and analysis for an improved allocation of HIV prevention funds in developing countries. The study includes five countries: India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Uganda.

This article reviews PANCEA's data collection methods. Our purpose is two-fold. First, we aim to explicate the methods and data sources used in PANCEA. Second, we want to give other health services researchers sufficient information to judge the potential suitability of adapting PANCEA's approach to their own efforts. Further details on the project and key documents (e.g., instruments) can be found in the online-only Appendix to this article available at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com, at the PANCEA link at http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=pancea, and from the authors.

The remainder of the paper addresses PANCEA's conceptual approach, data collection tools, data collection process, challenges and limitations, early findings, and applications for other health program assessments.

Conceptual Approach

PANCEA's approach to cost and services data has two purposes. The descriptive purpose is to document the range in observed program efficiency. As noted below, early data suggest a much larger range than published reports, which have typically been derived from research settings. The analytic and more challenging, but potentially more practical, purpose is to understand the causes of variation in the cost per service delivered, that is, of efficiency.

Assessing Efficiency

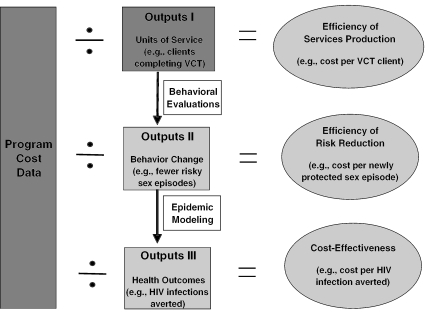

PANCEA is designed to generate three indicators of efficiency: cost per unit of service, cost per change in risk behavior, and cost per HIV infection averted. The measurement strategy (Figure 1) illustrates how these measures build on each other. Program costs are essential for all efficiency indicators, and are measured directly as described below. The first type of prevention output, also measured directly, is units of service provided by the program, such as condoms distributed or individuals receiving voluntary counseling and testing (VCT). This output allows comparison of the efficiency of prevention programs with similar services. The second type of output, reduction in risky behaviors, is assumed to be caused by units of service, as estimated from published evaluations of similar types of prevention programs. This output facilitates comparison of programs with different services but similar risk reduction goals. The final output, or outcome, is HIV infections averted. This output is assumed to be caused by risk reductions, and is estimated using computer epidemic models of HIV transmission that incorporate the estimates of reduction in behavioral risk. It allows comparison of programs with different risk reduction approaches but a shared ultimate goal of fewer HIV infections. The epidemic models will describe, based on the best available empirical data, the effect of various HIV prevention spending patterns on HIV incidence in specified epidemiologic settings. Thus, they can provide policy-relevant epidemiologic and cost-effectiveness information.

Figure 1.

PANCEA Conceptual Approach

This diagram shows the data and methods used to generate three measures of HIV prevention efficiency. Data on costs and outputs (darker gray rectangles) are collected from programs. Units of service are assumed to cause behavior change (light gray rectangle), to an extent estimated from published behavioral evaluations. Behavior change in turn affects health outcomes, as assessed with epidemic modeling. Finally, efficiency ratios (lighter gray ovals) are calculated as program costs divided by each type of output.

PANCEA analysis of the cost per HIV infection averted requires assumptions about the links between services, behavior, and HIV transmission. PANCEA is willing to rely on these assumptions because of the importance of comparing different types of HIV prevention strategies. The methods to specify these assumptions, literature review and epidemic modeling, have established methodological approaches on which PANCEA builds (Merson, Dayton, and O'Reilly 2000; Garnett 2002). This article focuses on the collection and analysis of cost and services data, which use less established methods.

Principal–Agent Model

PANCEA's approach to understanding the reasons for high or low efficiency builds on a conceptual model of health service production specific to developing country settings. Health care providers are viewed as “Agents” of two “Principals”—the user of their services (a perspective commonly adopted in the economic literature on physicians in private practice) and also their employer, whether government or private (Laffont and Martimort 2002; Hammer and Jack 2002; Devarajan and Reinikka 2003; Vick and Scott 1998). The patient can bring pressure to bear directly on the service provider through the market (by electing to use a different provider) or through community governance mechanisms (Bolduc, Fortin, and Fournier 1996; Hirschman 1970; 1980). Depending on the nature of the local political system, patients may also influence the behavior of public sector providers indirectly by expressing dissatisfaction to elected representatives (World Bank 2003).

The PANCEA project applies both “intensive” and “econometric” methods to draw inferences from collected data regarding the determinants of efficiency. The intensive analysis of 40 HIV prevention programs uses qualitative and quantitative data on governance, incentives, market structure, and the intrinsic motivation of providers, together with data on inputs and factor prices, in order to analyze the reasons for variation in efficiency. In addition to collecting quantitative data from program inception to the present, the intensive approach includes extensive discussions with senior program managers regarding program implementation. Analysis focuses on individual programs to describe patterns of costs and outputs over time as well as events in the program and community that may have influenced those patterns. The intensive approach generates detailed case histories with qualitative conclusions regarding predictors of efficiency. It is similar to methods often used in health program cost-effectiveness analyses.

The econometric analysis uses data for a single year from multiple programs to estimate a modified version of the traditional cost function. The need for cost functions has been emphasized by UNAIDS (UNAIDS 2000a). Since the structural equations describing the principal-agent relationships underlying program performance are difficult to identify or solve, we interpret our cost function as a reduced form of the implicit structural model. Our modified cost function includes variables suggested by the implicit principal–agent structural model, including governance, market structure (i.e., demand, patient information, competition), and the intrinsic goals and external incentives that motivate the provider.

The econometric analysis will estimate a multiple-output cost function of the form

where Cit is the total cost of operating program i in period t, ykit is the number of units of output k produced in program i in period t and xit is a vector of factor prices or proxies for the cost of doing business. The vector zit includes variables other than factor prices or output levels which are also measured and affect technical and price efficiency of the production process. Because the zit vector includes measures of governance, market structure, intrinsic goals and external incentives, it will capture some of the otherwise unexplained variation in efficiency across sites. The rest of the variation in efficiency is subsumed into the disturbance term ɛit. We will exploit data envelope analysis and stochastic frontier techniques in order to allocate variance in ɛit between the technical and price efficiency components (Newhouse 1994). Under maintained hypotheses about the functional form and the implicit principal–agent model of provider performance, the econometric approach will apply formal statistical methods to test hypotheses about efficiency variation.

We expect that VCT sites (our largest econometric sample) will produce three to five services. If we can obtain data for 75 prevention programs with overlapping outputs, the subscript i will range from 1 to 75. We are collecting multiple data points for many facilities to capture changes over time; thus, we anticipate a total of 200 to 500 observations. By measuring the relative influence of a wide range of possible predictors of efficiency, the econometric analysis should allow us to narrow the set of indicators needed in future analyses. The intensive and econometric approaches can together provide a richer understanding of efficiency and thus a better foundation for policy prescriptions.

Principals' use of incentives is captured in PANCEA through questions about supervision, monitoring, and reward structures. There is a large set of closed-ended questions; for example, the proportion of counseling sessions that are supervised, whether rewards or penalties are tied to staff performance, and mechanisms of program oversight. The broad constellation of influences affecting the behavior of agents is also captured through the qualitative questionnaire that inquires about how efficiency is affected by factors such as cash flow, political support, staffing, staff experience, and perceived service quality. The experience of clients is captured in service exit interviews with 10 to 20 clients, in which their views on the quality of the services are solicited.

HIV Prevention Types

PANCEA is assessing eight key HIV prevention types. These are VCT; prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (pMTCT); risk reduction for injecting drug users; risk reduction for sex workers (SW); treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STI), information-education-communication (IEC); condom social marketing (CSM); and school curricula. These were selected because they are part of the core prevention response to the HIV epidemic in most countries. For several, there is a sizable body of scientific evidence suggesting that they are effective (Merson, Dayton, and O'Reilly 2000). For others, (IEC, CSM, and school curricula), the evidence of effectiveness is less clear. Nevertheless, sizable portions of the total HIV prevention spending are used for these interventions, and this alone makes them worth understanding better.

Data Collection Tools

PANCEA examines multiple interventions in varied organizational settings and countries. Therefore, a central PANCEA task was to develop an integrated set of data collection instruments that simultaneously respond to two conflicting imperatives. We needed to portray program operations with sufficient detail and flexibility to capture variation among nominally similar program types; and we needed sufficient standardization to permit valid comparisons across multiple programs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data Collection Approaches

| Time Period, Cost and Output Data | Data Types | |

|---|---|---|

| Abbreviated (Econometric) (N=200) | Last Fiscal Year and Most Recent Month | Costs |

| Outputs | ||

| Limited Interpretive Data | ||

| Intensive (n=40) | From Inception to Last Month | Costs |

| Outputs | ||

| Extensive Interpretive data |

Further, since PANCEA must identify the determinants of efficiency for a wide range of possible variables, we gathered qualitative data to help interpret quantitative data on costs and outputs. This differs from approaches in more mature areas of health services research that seek to test a small number of previously-identified variables thought to be related to the outcome of interest.

Measuring Outputs

PANCEA gathers information on several service outputs for each intervention type. These include both intermediate and final outputs. The “final” outputs are those thought to have the greatest potential to reduce HIV transmission and are the project's raison d'etre. For example, in VCT programs we define two final outputs: clients who received posttest counseling, and HIV-positive clients who received posttest counseling. These outputs are the basis for predicting reduction in risky behaviors and HIV infections (Table 2).

Table 2.

HIV Prevention Program Outputs by Intervention Type

| Essential Outputs | Secondary Outputs | |

|---|---|---|

| VCT | Clients (All and HIV+) Receiving Posttest Counseling. | Pre-Test Counseling; HIV Tests; Results Received; HIV+; Condoms. |

| pMTCT | Women-infant pairs receiving ARVs. | Pre-test counseling, HIV tests; results received; HIV+; substitute feeding; condoms. |

| Sex Workers | Determined during data collection, typically includes: outreach contacts, vocational training, STI management, condoms. | |

| Injecting Drug Users | Determined during data collection, typically includes: drug treatment, outreach contacts, needle exchange, STI management, condoms, bleach. | |

| Sexually Transmitted Infections | Cases diagnosed/treated, by pathogen/syndrome. | First and follow-up visits; condoms. |

| Information-Education-Communication | Media contacts. | Campaigns; mix of media types. |

| Condom Social Marketing | Condoms distributed (own brand). | Condom market volume. |

| Schools | Students completing curriculum. | Hours of curriculum completed; teachers trained. |

For some interventions, such as VCT, outputs are relatively standardized. In others, varied activities are conducted under one rubric, for example, risk reduction for sex workers and injecting drug users and IEC campaigns. These interventions are defined more by the target population than by intervention content, even though certain activities appear repeatedly. To capture all activities, we ask respondents to define all their activities and outputs, rather than attempting to impose a predetermined structure. We use a uniform set of questions to furnish a clear picture of the resources required for each activity (e.g., see the “Activity Output Grid” of ARQsw at http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=pancea). The instruments also record information on the programs' governance and organizational setting, as these may affect “agent” behavior and thus the type, quantity, and quality of program outputs.

Measuring Inputs (Costs)

We perform a comprehensive assessment of the costs of running HIV prevention interventions. Cost instruments were extensively adapted from templates produced by others (UNAIDS 2000b). This adaptation incorporated a time element, prespecified items, and also key characteristics of many inputs. It was piloted and revised, and programmed into an MS Access database.

Cost data (expenditures) are grouped in three standard categories, each with finer detail: personnel, other recurrent goods and services, and capital. Working with program staff, we collect data on personnel expenditures from financial and staffing records, including salaries and other compensation paid to employees. Recurrent nonpersonnel cost data include such diverse items as medicines, laboratory tests, supplies, office and administrative expenses, and utilities. Lastly, capital expenses include purchases of durable items such as medical equipment, vehicles, computers, training, and buildings.

Allocations

Many facilities that provide HIV prevention services, such as hospitals and clinics, also provide other services that share the same personnel and other inputs. These facilities usually do not keep separate accounts for the intervention of interest to PANCEA. Therefore, we use two approaches to allocate inputs to the intervention. First, we explicitly allocate inputs. Personnel allocations are based on the proportion of time spent by each staff member on tasks relevant to the HIV prevention intervention under study, or based on the proportion of space dedicated to the intervention. Capital and recurrent costs are allocated to the intervention based on the proportional use of each item. Explicit allocations are sometimes based on project management documents; more typically they are estimated through a sequence of questions in which managers are asked to account for the division of inputs among various activities. Second, we collect data on all facility services (e.g., outpatient visits). These can be used in econometric regressions to analytically derive allocations of inputs among purposes, if statistical power is adequate.

Interpretive Data

In addition to the quantitative data discussed above, PANCEA seeks qualitative information on the history of each program, from conceptualization through implementation, stabilization, and possible expansion or contraction. Events occurring during program implementation can have profound effects on costs, outputs, and efficiency. For example, a program may initially have more staff than it needs; may have trouble recruiting clients; or may quickly reach an initial set of clients, but later need to invest heavily in outreach to maintain its clientele. There may be periodic trainings for staff or meetings to address community concerns that lead to spikes in costs. By linking output and cost data over time to an understanding of the events, decisions, and circumstances affecting the program's development, PANCEA seeks a better understanding of the factors affecting efficiency over time. This approach reveals much about the economics of starting, maintaining, and building programs. It also underscores common themes that suggest general lessons applicable across settings and intervention types.

Selected tentative findings from qualitative data relate to costs, demand, and worker morale. Gaining community acceptance through meetings and trainings can use a large part of sex worker program expenditures; perceived effectiveness of HIV prevention mass media campaigns on generating VCT demand appear uncorrelated with efficiency; and lowering user fees does not necessarily increase effective demand for services. In selected VCT sites, lower fees caused reductions in staff compensation, reducing morale. This in turn was accompanied by lower productivity as clients were discouraged from seeking services due to longer waiting times.

Exit Interviews

Perceived quality is an important influence on demand for services. Thus, PANCEA conducts 15–20 randomly selected client exit interviews per program with reachable clients. Each of these interviews lasts about 10 minutes and asks about socioeconomic characteristics such as income and educational level, the time and money it required to access services, the reasons why the client selected this site, the services received, waiting time, and satisfaction with those services. These exit interviews provide an important alternative to the perspective of programs staff who provide all other PANCEA data.

Data Collection Process

Research Network

At the writing of this article, data collection was in its final phase and was to be completed by July 2004. Data collection in each country is carried out by a team of 8 to 15 HIV researchers. Professional background varies: physicians, health services researchers, economists, epidemiologists, and social scientists. Collaborators were selected on the basis of a prior record of high quality data collection and analysis; ability to assemble an appropriately skilled and managed team, and network of contacts among HIV prevention agencies. In-country collaborative teams are: India (Administrative Staff College of India), Mexico (Instituto Nationale de Salud Publica), Russia (Pavlov University and AIDS Infoshare); South Africa (HIVAN and Axios International), and Uganda (Axios International).

Training and Piloting

Each team underwent a two-week training program. The first week reviewed the theoretical basis of PANCEA and the details of instrument administration. Training formats included structured lectures; review of key instrument and manual sections, and role-playing. The second week comprised pilot data collection at an HIV prevention site, usually with oversight by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The pilots served the dual purpose of training the data team and of piloting the instruments for that country.

A key concept of the training is, “Do not miss the forest for the trees.” Because PANCEA entails the collection of a large volume of data, this concept is crucial. By “trees” we mean details that contribute little to our understanding of prevention efficiency or its determinants; whereas “forest” refers to data that largely determine efficiency. Examples of the “tree” data include the exact amount of the project's monthly water bill; or the year of manufacture of the project's van. Although both of these items ultimately enter into the numerator of the cost-effectiveness ratio, they affect the ratio only minimally. We asked our teams to make common sense judgments about how much effort to expend for marginal gains in precision.

“Forest” items, by contrast, have a powerful influence on estimates of efficiency, so we were willing to devote many person-hours to obtaining good estimates. These key data elements always include final outputs used as the denominator for the cost-effectiveness ratio (e.g., the number of individuals receiving VCT, or the number of SW receiving services). For inputs, “forest” items are those that represent a significant portion of costs, e.g., HIV test kits, staff compensation, and community outreach.

The forest-trees distinction represents a departure from ideals of precision in data. We believe that, given the volume of PANCEA data and the varied forms these data take across programs, the pertinent question is not whether there will be compromises away from the ideal. Instead, it is, “Can compromises be managed so that imprecision is tolerable?” Before developing the forest-tree distinction, we found that data teams were expending large and sometimes frustrating effort on details with little payoff in final results. By confronting the issue explicitly and including it in our training and reviews of collected data, we found that we greatly increased the likelihood of confining imprecision to acceptable levels.

Data Collection Visits

Each data team consists of two data collectors, with part-time supervision by a team leader. The econometric data collection sites require three to four full days of the team at each site. Often data collection is done in a greater number of partial days or spread over several weeks, to accommodate respondent schedules. Along with data cleaning and data entry performed off-site, each case study site thus requires seven to twelve person-days of work.

Data collection begins with the first section of the interpretative data instrument. These questions ask about the program's history and development and obtain the perspective of the project director on the program's greatest accomplishments and challenges, and how these affected costs and outputs. The data teams then collect information on program outputs by month or by quarter for the last month and most recent fiscal year. With the help of fiscal staff, the team then collects detailed cost data, broken down by the same time periods as the output data. Exit interviews are conducted throughout the visit. Data are entered into the MS Access database created for this purpose.

The organization of data collection at the intensive data collection sites matches the sequence described above. However, because more detailed interpretive data are collected about the determinants of efficiency, and because costs and output data are collected over the project's entire history, the data collection at the “full” sites lasts about 50 to 75 percent longer.

Quality Assurance

Rigorous training increases the likelihood that the data collected will be valid. PANCEA also developed three further mechanisms to encourage high quality data and to correct errors: “data reviews” and “data verification visits” (discussed below) and “technical notes” (see online-only Appendix).

PANCEA's in-country teams review data before sending them to UCSF. The UCSF team then conducts an additional in-depth review of all data gathered at each site. Each response is scrutinized to determine its “face validity” and consistency with other information gathered at the same program. For example, in the interpretive instrument, respondents may report that the inability to maintain condom supplies was a major factor inhibiting program outputs. However, there is also a question in the outputs instrument about stock interruptions, and if it indicates that stock interruption was not an issue, the UCSF data reviewers would point out this discrepancy and ask for clarification. These requested clarifications (prioritized according to the forest-tree distinction) are assembled into a structured memo and sent to the data collection teams. The data are returned to UCSF for a second systematic review, and further revisions are made as necessary. The final data are entered into the database.

Data verification visits are conducted at 10 percent of the sites (typically four per country) to verify the accuracy of PANCEA data. Half of the sites are chosen on the basis of surprising or interesting findings. The other half are chosen randomly. During these visits, a UCSF staff person and members of the in-country team spend a day at each chosen site, reviewing a list of issues that are potentially problematic or important to reconfirm with the project director or other staff until full resolution. Examples of data verified in these visits include key program outputs and the allocation of staff effort narrowly to the HIV prevention activities of interest to PANCEA.

Data Sources

Ideally, all quantitative data should be drawn directly from written project records, especially those overseen by outside reviewers such as funders or auditors. When such documents were available, we used them. For example, VCT programs often have detailed records on the specific intervention steps (pretest counseling, etc.), and some sex worker programs record each outreach worker contact.

However, available written records were often incomplete or imperfectly matched to PANCEA instruments. For example, clinic attendance records might not record all visits for suspected STIs, instead only if a test was done. Or, financial records might not contain detail on intervention-specific supplies. Thus, records often required interpretation by respondents to provide needed PANCEA data, or we relied on respondent recall.

Without inclusion of less-formal data sources, many HIV prevention programs would have been excluded. For example, without relying on managers' estimates of the portion of a nurse's time spent on MTCT, our only alternative would have been prohibitively expensive time and motion studies. We were willing to sacrifice some precision for a much more inclusive portrayal of the universe of HIV prevention programs.

PANCEA data collectors documented sources for all of the information they collected, using a classification scheme that ranks data sources (Table 3). This approach serves four purposes. It is basic research documentation. Second, during data verification visits, having a description of data sources makes it easier to retrieve them. Third, in analysis, it can help determine the proper weight to assign to particular data items, that is, data from more reliable sources may be more heavily weighted. Finally, quality of record keeping could itself prove to be a quality marker.

Table 3.

Data Sources (Selected)

| • SR: Written summaries or reports whose numbers are used directly. Example: Recurrent spending from audited report. |

| • RR: Raw written records whose numbers are used directly. Examples: Complete registers of salary payments; register of HIV tests completed. |

| • RR-R: Raw written records informed by recall. Example: Invoices for condom purchases, with recall for number purchased and thus price. |

| • WP: Written policies/protocols. Example: Counseling protocol. |

| • RO: Recall only. Example: Percent effort on two interventions. |

| • EE: Estimation extrapolated from similar data. Example: Salary to hire someone to do volunteer's work, based on a similar employee's salary. |

| • Guess: Really rough estimate. No basis in data. |

Challenges and Limitations

In implementing PANCEA, we faced substantial challenges. This section reviews some of these challenges, how we addressed them, and how they may limit study implications.

Intervention Mix

In deciding the intervention-type composition of the sample, we faced competing considerations. We wanted the sample to be representative of all potential interventions. However, we also wanted sample size adequate to provide statistical power for econometric regressions within intervention type, which might be facilitated by focusing on selected interventions. Further, we wanted to compare the same intervention across countries, but also study intervention types uniquely important to specific countries. Ultimately, we decided to have substantial data collection for VCT in all countries, plus a second focus on a different intervention in each country. Thus, VCT is being studied in 90 of 200 total sites. This is due to VCT's central role in prevention and treatment, as well as good evidence of effectiveness and a relatively standard implementation format amenable to cross-program comparison. Several interventions are the focus of country-specific efforts (e.g., risk reduction for IDUs in Russia, risk reduction for sex workers in India and South Africa, IEC in Mexico). Other interventions are studied one per country (for IEC and CSM, there is often only one). This approach means that for most interventions we have only a limited sample, and thus can do intensive but not econometric analyses.

Stand-Alone versus Integrated

Another major challenge is that for some intervention types in some countries, the usual delivery mode is full integration into other clinical activities. In these instances, the programs that are easier to study are the smaller subset of programs that are “stand-alone,” whereas the programs more representative of how that intervention is delivered are harder to study. We decided to maintain a substantial, if not completely proportional, focus on the major mode of delivery.

Sampling

PANCEA found pure random sampling to be impractical, for several reasons. First, the country teams reported that obtaining comprehensive lists of common programs was extremely difficult. This was because of studying multiple interventions, and since program variation of interest (e.g., smaller size, or nongovernmental management) might lead to exclusion from established lists. The lists that were found were incomplete and included stale information due to rapidly changing organizational and programmatic mixes. Further, the teams reported that cold calls were unlikely to succeed, given the time-consuming and intrusive nature of the site visit; instead, a prior direct or indirect relationship was essential for access. Thus, PANCEA used purposive sampling, when possible, from a working list up to four times larger than the required sample. We selected sites varied on ownership (government/nongovernmental), size, and rural/urban. This approach may limit generalizability, though we believe the accumulated sample captures important variation in program implementation.

Documenting Temporal Change in Predictors of Efficiency

One major PANCEA goal is to examine the temporal relationship of potential predictors of efficiency (e.g., events in the program and community) and observed costs, outputs, and efficiency. However, we could not ask about such predictors (e.g., the length of a counseling session or staff incentive systems) for each month. Instead, we developed a “query change” approach, which involves asking if practices in place in the last month were also in place for the preceding fiscal year, and if not, when and how they changed. This proved to be an efficient mechanism to document change or stability in these predictors.

Integral Volunteers

As noted above, PANCEA assigns economic costs to donated resources. However, there is a class of volunteer whose role as a volunteer is so integral to the mission of the intervention that the intervention would not pay them even if it could. An example is when volunteerism helps clarify the motivation of a volunteer peer educator in the eyes of intervention clients. If this volunteer were paid for her work, she would lose credibility in her community and thus be unable to perform her function. To determine if a volunteer is “integral,” we ask, “Would paying this volunteer a salary run counter to the mission of this intervention?” If the answer is “yes,” no economic costing is done.

Interaction of Analytic Techniques

As discussed above, PANCEA is a study of both multiple intervention types, and multiple analytic approaches. In particular, 40 sites receive an “intensive” single-site evaluation, while a majority of sites (VCT for all countries, plus other interventions for selected countries) are also subject to econometric analyses. Quantitative and qualitative data are collected in parallel in all sites (plus one formal anthropological case study). Thus, we hope to learn more about the substantive consistency and relative merits of different analytic approaches. Further, we hope to demonstrate how the methods complement each other. Can findings from intensive sites serve as hypotheses to be tested with econometrics? Can intensive analyses or qualitative data explain relationships observed with econometrics?

Early Findings: VCT and Sex Worker Programs

Here we present early findings that illustrate our methods and the lessons that may be learned from PANCEA.

Costs and Outputs

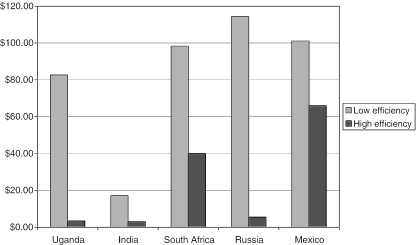

Among the most important findings are that the costs of operating HIV prevention programs are both very variable and often substantially higher than the published literature suggests. For example, the cost per person completing VCT varies 24-fold among programs in Uganda, and 20-fold in Russia (Figure 2). In South Africa and India this cost varies by a less dramatic but still sizable 2.5- and 6-fold respectively. The unit cost estimates for several of the PANCEA Uganda and South Africa sites exceed the $3.50–$48.00 range found in the published literature for sub-Saharan Africa (Alwano-Edyegu and Marum 1999; Sweat et al. 2000; Kumaranayake and Watts 2000).

Figure 2.

Range in Cost per Client Receiving VCT in Five Countries Studied by PANCEA

We found similarly large variations in unit costs for 15 peer-education based sex worker programs examined in Andhra Pradesh, India. These sites were selected as a geographically representative and near-complete sample of sex worker programs in Andhra Pradesh. The cost per client contact ranges from $0.72 to $3.01 (median, $1.65). The scale varies from 5,649 to 57,134 client contacts annually (median, 15,424), and appears to be highly and positively correlated with unit costs. Costs for SW programs are dominated by personnel and recurrent goods, which together account for 75 percent of total expenditures. Recurrent goods, in turn, are largely represented by male condoms and STI medications.

We are currently undertaking analyses to explore a range of predictors of these large variations in VCT and SW costs, outputs, and efficiency. Because the unit cost range is large, identifying efficiency predictors could have important implications as policymakers seek to direct funding to efficient programs.

Behavior Change

We reviewed seven studies of changes in condom use due to HIV prevention programs for sex workers. A study in India (Bhave et al. 1995) found an 81 percent reduction in the probability of unprotected sex episodes. Other studies found reductions of 50 to 90 percent. Because the Bhave study was done when awareness of HIV was lower in India, and to be conservative, we assumed a 70 percent reduction in unprotected sex episodes.

Epidemic Impact

HIV transmission risks in casual partnerships, including between SWs and clients, are calculated using equations that include number of partners; sex episodes per partner; HIV transmission per episode; rate and effectiveness of condom use; and HIV prevalence. Illustrative equations and calculations are presented below, using risk equations derived from past work (Fineberg 1988; Weinstein et al. 1989; Kahn, Washington, and Showstack 1992; Kahn et al. 1997). PANCEA epidemic modeling will portray HIV spread across multiple groups and years.

Risk of HIV acquisition from clients=

| (1) |

Risk of HIV transmission to clients from infected SWs=

| (2) |

where h=HIV prevalence in SW clients (estimated 8 percent for Andhra Pradesh); p=transmission per unprotected sex episode (0.004 male to female, 0.002 female to male); b=proportion of episodes in which condoms are used (0.56 baseline, 0.87 with prevention program); f=effectiveness of condoms (94 percent); n=episodes per client (1); m=number of partners (1,000 per year). These equations were modified to account for the effect of STIs in amplifying transmission risk. Application of this model to 1,000 SWs with HIV prevalence 19.5 percent yields an estimated 142 new infections in SWs and 174 in clients, for a total of 316 per year. With higher condom use due to an SW program, new infections fall to 134, a drop of 58 percent. The reduction is less than the reduction in noncondom episodes, due to imperfect protection provided by condoms and thus HIV risk that is unaffected by new condom use.

These estimates of cost and impact allow calculation of a crude but indicative cost-effectiveness ratio. Unadjusted for medical costs averted and program variation, the cost per HIV infection averted can be estimated as $1.65 / (0.316–0.134)=$9. Final PANCEA estimates of cost-effectiveness will be represented as ranges, reflecting uncertainty in inputs, and will take into account medical costs averted as well as fuller epidemic portrayals.

Applications for Other Health Program Assessments

The data collection instruments and methods created for PANCEA can be applied with little modification to other HIV prevention programs. This is because the programs selected for PANCEA, far from being idiosyncratic, represent the mainstream of HIV prevention strategies. We are willing to share instruments with other researchers (check the PANCEA link at http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=pancea).

Furthermore, most of the issues addressed in these instruments are likely to arise in many types of health-related programs. These include characterizing costs, inputs, and outputs over time; collecting potential predictors of efficiency; allocating inputs over a range of activities; distinguishing between financial and economic costs; defining a “facility”; documenting data sources; and verifying data quality. PANCEA, by addressing these and other issues in an explicit, documented, and systematic fashion, may be adaptable for a range of health services research projects outside of HIV prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors were responsible for developing and integrating major elements of PANCEA methods and several also contributed data for this paper. In addition, the following individuals contributed substantially to the development of one or more specific methods in PANCEA: Sergio Bautista, Jo-Ann Du Plessis, Geoff Garnett, Birgit Hansl, Nell Marshall, Sowedi Muyingo, Christian Pitter, and Anne Reeler.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Task Order no. 7, contract 282-98-0026, and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse through grant R01 DA15612.

References

- Alwano-Edyegu M, Marum E. Knowledge Is Power: Voluntary HIV Counselling and Testing in Uganda. Geneva: UNAIDS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Lindan C, Hudes E S, Desai S, Wagle U, Tripathi S P, Mandel J S. “Impact of an Intervention on HIV, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Condom Use among Sex Workers in Bombay, India.”. AIDS. 1995;9(1, supplement):S21–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolduc D, Fortin B, Fournier M A. “The Effect of Incentive Policies on the Practice Location of Doctors: A Multinomial Probit Analysis.”. Journal of Labor Economics. 1996;(14):703. [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan S, Reinikka R. “Making Services Work for Poor People.”. Finance and Development. 2003;40(3):48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg H. “Education to Prevent AIDS: Prospects and Obstacles.”. Science. 1988;239:592–96. doi: 10.1126/science.3340845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett G P. “The Geographical and Temporal Evolution of Sexually Transmitted Disease Epidemics.”. Sex Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(1, supplement):i14–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer J, Jack W. “Designing Incentives for Rural Health Care Providers in Developing Countries.”. Journal of Development Economics. 2002;69(1):297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman A O. Exit Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman A O. “‘Exit, Voice, and Loyalty’: Further Reflections and a Survey of Recent Contributions.”. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1980;58(3):430–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J G, Gurvey J, Pollack L M, Binson D, Catania J A. “How Many HIV Infections Cross the Bisexual Bridge? An Estimate from the United States.”. AIDS. 1997;11(8):1031–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J G, Washington A E, Showstack J. Updated Estimates of the Impact and Cost of HIV Prevention in Injection Drug Users. San Francisco: Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; 1992. Prepared for the Centers for Disease Control. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaranayake L, Watts C. “Economic Costs of HIV/AIDS Prevention Activities in Sub-Saharan Africa.”. AIDS. 2000;14(3, supplement):S239–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffont J J, Martimort D. The Theory of Incentives: The Principal-Agent Model. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marseille E, Hofmann B P, Kahn J G. “HIV Prevention before HAART in Sub-Saharan Africa.”. Lancet. 2002;359(9320):1851–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merson M H, Dayton J M, O'Reilly K. “Effectiveness of HIV prevention Interventions in Developing Countries.”. AIDS. 2000;14(2, supplement):S68–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse J P. “Frontier Estimation: How Useful a Tool for Health Economics?”. Journal of Health Economics. 1994;13(3):317–23. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweat M, Gregorich S, Sangiwa G, Furlonge C, Balmer D, Kamenga C, Grinstead O, Coates T. “Cost-effectiveness of Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling Cost-effectiveness of Voluntary Counseling and Testing in Reducing Sexual Transmission of HIV-1 in Kenya and Tanzania.”. Lancet. 2000;356(2000):113–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. 2000a. Report on the UNAIDS Epidemiology Reference Group Meeting, Rome, October 8–10, 2000. Geneva, Switzerland.

- UNAIDS. “Costing Guidelines for HIV Prevention Strategies.” In UNAIDS Best Practices Collection/00.31. Geneva, Switzerland.

- UNAIDS. 2004. “2004 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: 4th Global Report” Geneva, Switzerland.

- Vick S, Scott A. “Agency in Health Care: Examining Patients' Preferences for Attributes of the Doctor–Patient Relationship.”. Journal of Health Economics. 1998;17(5):587–605. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M, Graham J, Siegel J, Fineberg H. Cost-effectiveness Analysis of AIDS Prevention Programs: Concepts, Complications and Illustrations. In: Turner C, Miller H, Moses L, editors. AIDS: Sexual Behavior and Intravenous Drug Use. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Making Services Work for Poor People. Washington, DC: World Bank and Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]