Abstract

Objective

To assess patients' use of and preferences for information about technical and interpersonal quality when using simulated, computerized health care report cards to select a primary care provider (PCP).

Data Sources/Study Setting

Primary data collected from 304 adult consumers living in Los Angeles County in January and February 2003.

Study Design/Data Collection

We constructed computerized report cards for seven pairs of hypothetical individual PCPs (two internal validity check pairs included). Participants selected the physician that they preferred. A questionnaire collected demographic information and assessed participant attitudes towards different sources of report card information. The relationship between patient characteristics and number of times the participant selected the physician who excelled in technical quality are estimated using an ordered logit model.

Principal Findings

Ninety percent of the sample selected the dominant physician for both validity checks, indicating a level of attention to task comparable with prior studies. When presented with pairs of physicians who varied in technical and interpersonal quality, two-thirds of the sample (95 percent CI: 62, 72 percent) chose the physician who was higher in technical quality at least three out of five times (one-sample binomial test of proportion). Age, gender, and ethnicity were not significant predictors of choosing the physician who was higher in technical quality.

Conclusions

These participants showed a strong preference for physicians of high technical quality when forced to make tradeoffs, but a substantial proportion of the sample preferred physicians of high interpersonal quality. Individual physician report cards should contain ample information in both domains to be most useful to patients.

Keywords: Quality, health care, primary care, physician profiling

The release of performance data about health care providers to the public as a means of improving quality of care has been advocated by government agencies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), nonprofit accreditation organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), and private sector organizations such as the Leapfrog Group (National Committee for Quality Assurance 2003; The Leapfrog Group Purchasers 2003; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2004). In theory, increased access to information about providers will produce better-informed consumers and set the stage for quality improvement (Marshall et al. 2000). These consumers who have information about the quality of prospective providers will tend to select providers who deliver care of higher quality, increasing the market share of high-quality providers and creating incentives for improving quality of care (Marshall et al. 2000). Convincing consumers that quality problems are real and improving the dissemination of quality information are among other important considerations in this conceptual framework (Shaller et al. 2003).

Report cards that summarize performance data are widely available for health plans (The Pacific Business Group on Health 2003; United States Office of Personnel Management 2003a; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2004) and hospitals (The Pacific Business Group on Health 2003; U.S. News and World Report 2003), but not individual providers. However, there is increasing interest in the use of physician performance measures. For example, CMS is developing physician-level performance measures as part of the Doctor's Office Quality project (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2003). The Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS®) investigators are also developing survey instruments to assess individual physicians and physician groups (Solomon et al. 2005; Hays et al. 2003; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2004a). Because individual provider-level information is potentially more salient and directly applicable to patients (Schauffler and Mordavsky 2001; Gandhi et al. 2002), patients may use report cards of individual providers more extensively than they use existing report cards.

The effectiveness of physician-specific report cards will depend, in part, on their content and the relevance of the information to consumers (Shaller et al. 2003). In theory, report cards could contain information about technical and/or interpersonal quality, and this information could come from a variety of sources. Thus far, however, report cards on individual providers have been largely limited to reporting surgical mortality data (Damberg, Chung, and Steimle 2001; Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council 2002; New York State Department of Health 2003). These report cards are based on data collected from systems or records and emphasize patient outcomes that depend on technical aspects of care. Survey-based tools to evaluate patients' experiences with primary care physicians are another potential source information (Safran et al. 1998). Report cards that summarize patients' assessments for other consumers have been developed as part of CAHPS (Farley et al. 2002; CAHPS-SUN 2003). Although some Supplemental CAHPS questions clearly focus on technical aspects of care (e.g., Have you had a flu shot in the past 12 months?) (CAHPS-SUN 2003), CAHPS and other survey-based tools emphasize interpersonal over technical aspects of care. Focus groups and interviews conducted as part of CAHPS demonstrated early on that consumers were most interested in consumers' reports about aspects of care such as communication and respectful relationships (CAHPS-SUN 2003). Future report cards of individual providers may include measures of technical quality, measures of interpersonal quality, or a mixture of both types of measures. Greater understanding of patients' values for technical and interpersonal quality may improve the content and relevance of provider report cards and help providers improve the quality of their practice.

Previous studies have helped us understand the values patients place on technical and interpersonal quality in a primary care setting. Wensing et al. (1998) reviewed the literature on patient priorities for general practice care and found that both technical and interpersonal quality are important to patients. Studies that go beyond assessing attitudes to elicit patient choices are important, because “separate attitudes to two objects do not necessarily predict the outcome of a choice or direct comparison between them” (Kahneman, Ritov, and Schkade 2000). Few studies have examined how patients would set priorities, if forced to make choices or tradeoffs between technical and interpersonal quality in the primary care setting (Fletcher et al. 1983; Jung et al. 1998; Wensing et al. 1998). Without concrete information about technical quality, patients may perceive that they are receiving high-quality technical care if their provider has strong interpersonal skills (Ware and Williams 1975). No studies have assessed patient priorities in the context of report cards, which have the capability of providing patients with information about both the interpersonal and technical quality of a prospective physician.

In our study, we sought first, to determine if patients would make use of information about both technical and interpersonal quality and second, to assess patients' preferences for technical versus interpersonal quality when using computerized report cards to select a new primary care provider (PCP).

Methods

Participants

A professional survey recruitment firm enrolled 304 participants who were 18 years of age or older, lived in Los Angeles County, and had a regular or primary care physician. We restricted our sample to participants with a primary care physician, because we believed that their established patient–provider relationship would allow them to have context for completing the study task. Participants came from a large proprietary database (approximately 40,000) containing a broad spectrum of people with diverse ethnic background from Los Angeles County and who all have one characteristic in common, their agreement to be on a list of potential participants in focus groups or survey studies. Recruiters screened for subjects who were comfortable reading English on a computer screen, although they did not specifically screen for prior computer use.

Recruiters obtained a quota sample to achieve equal numbers by gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black), and age group (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, ≥65 years). Project staff conducted 22 two-hour sessions in seven locations across Los Angeles County selected to increase socioeconomic and racial/ethnic diversity. The project was determined by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee and the Greater Los Angeles Veterans Administration Institutional Review Board to be exempt from review under 45 CFR 46.101 (b) (2). The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles in the Belmont Report (National Institutes of Health 1979).

Study Design

Overview of Sessions

The lead staff member explained the purpose of the project, computer use, and task, and read aloud the introductory pages, while 15 participants at each session followed along on the computers provided to them. Participants were told that the purpose of the project was to help us learn more about how patients choose a new doctor. Then, participants were presented with comparative information in computerized report card format about physicians and allowed to work at their own pace, although hands-on computer assistance was available throughout the session. Participants viewed information about two physicians at any given time, reviewing information for a total of seven pairs of physicians. After viewing each pair of report cards, participants recorded the physician they selected on the computer. Then, participants completed a self-administered paper questionnaire, which collected demographic information and asked a series of open-ended questions designed to assess in their comprehension of the report cards. Participants received $75 at the end of the session.

Description of Introductory Pages and Task

The introductory pages, which included an overview of the role of primary care physicians, instructed participants to imagine that they had moved to a new city. With the help of family, friends, and co-workers, they had narrowed their list of new primary care physicians to two that were equal in all respects, except for the information contained in the health care report cards provided to them by a trustworthy nonprofit organization.

Subjects then learned that the report cards contained the following categories of evaluations of physicians: (1) limited sickness or injury care (acute care), (2) care for ongoing health conditions (chronic care), (3) preventive care, (4) communication, (5) courtesy and respect, and (6) promptness. We identified the first three categories as technical quality and labeled them “Technical Evaluation.” We labeled the last three categories “Patient Experiences,” which represented the concepts of interpersonal quality and getting care quickly. In these introductory pages, we informed subjects that ratings for “Technical Evaluation” came from review of medical charts and insurance bills and ratings for “Patient Experiences” came from asking patients about their experience with the doctor. In constructing the introductory pages that provided this information, we ensured that the two categories were also similar visually, with definitions of similar length and symmetric placement on the screen.

The ratings assigned to five of the seven pairs of physicians forced participants to make varying degrees of tradeoff between technical and interpersonal quality for each decision. For example, one physician had high technical quality and low interpersonal quality ratings, while the other physician had low technical quality and high interpersonal quality ratings (Table 1). Two of the seven pairs tested for internal validity by including a physician who was superior in both dimensions, and who was therefore the dominant choice regardless of which dimension the patient considered more important. Although “Technical Evaluation” and “Patient Experiences” each had three subheadings, the ratings among the three subheadings were highly correlated, enabling us to test tradeoffs only between technical and interpersonal quality rather than among the different subheadings of technical and interpersonal quality. High correlation among the “Patient Experiences” subheadings (communication, courtesy/respect, promptness) has been found in the community (Hargraves, Hays, and Cleary 2003).

Table 1.

Description of Seven Pairs of Physicians Presented to All Participants

| Physician A | Physician B | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Average technical | High technical | Tradeoff |

| High interpersonal | Average interpersonal | |

| High technical | Low technical | Tradeoff |

| Low interpersonal | High interpersonal | |

| Average technical | Low technical | Tradeoff |

| Low interpersonal | Average interpersonal | |

| High technical | Average technical | Tradeoff |

| Low interpersonal | Average interpersonal | |

| Low technical | Average technical | Tradeoff |

| High interpersonal | Average interpersonal | |

| Average technical | High technical | Internal validity check |

| Average interpersonal | High interpersonal | |

| Average technical | Low technical | Internal validity check |

| Average interpersonal | Low interpersonal |

High, above community average; low, below community average.

Details about Report Cards

Previous studies in this area have focused primarily on health plan report cards (Hibbard, Slovic, and Jewett 1997; Hibbard et al. 2000; 2001) and have demonstrated that multiple factors affect consumer use of health care report cards, including presentation format (Jewett and Hibbard 1996; Knutson et al. 1996; Hibbard, Slovic, and Jewett 1997; Hibbard et al. 2000; 2001; 2002; Marshall et al. 2000; Harris-Kojetin et al. 2001; Scanlon et al. 2002; Vaiana and McGlynn 2002). In designing our report cards, we incorporated key features in the literature on health care report card use.

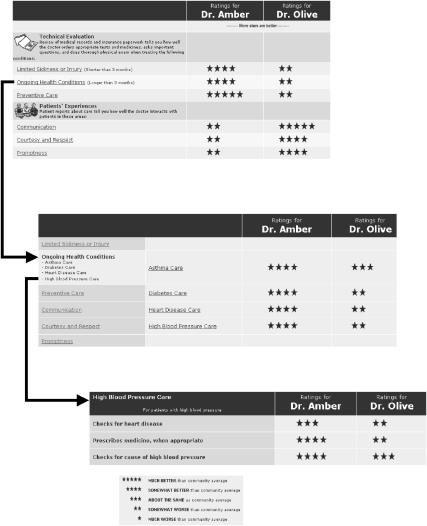

For example, we enabled participants to control the amount of information that they would view at any given time to decrease cognitive overload (Figure 1) (Vaiana and McGlynn 2002). We chose to present the report cards on computer so that we could employ technology that people frequently encounter on websites, including existing health care report card sites (The Pacific Business Group on Health 2003; United States Office of Personnel Management 2003a): click on an underlined word or phrase with the computer mouse to access more information about the word or phrase on a new web page. This feature enabled us to provide both summaries and details about the quality of each physician. The ratings on each set of web pages were the arithmetic mean, rounded to the nearest integer, of more detailed ratings found on the next set of web pages. For instance, Dr. Amber received a three-star rating and two four-star ratings for his care of high blood pressure (Figure 1). Since the arithmetic mean of these ratings after rounding equals four, his overall rating for high blood pressure care, which is displayed next to the label “high blood pressure,” was represented with four stars.

Figure 1.

Example of hypothetical report with three layers of information

Furthermore, we tried to improve the evaluability of our report cards by using techniques suggested in prior studies (Hibbard et al. 2001). For instance, we provided a consistent number of subheadings for technical and interpersonal quality on the top layer of the report card. In addition, we enabled participants to select the presentation format that they preferred: stars, bars, letter grades, or numbers, because it is not clear that one presentation format facilitates decision making more than others, and allowing participants to select the format they prefer could make the report cards more useful (Vaiana and McGlynn 2002). Each participant viewed all technical and interpersonal quality ratings in the format he or she selected so that visual cues were consistent for both types of quality information.

Moreover, a health literacy consultant applied the Fry Readability Formula1 to sections of the introductory and report card pages that had sufficient text to yield valid results, identified words and concepts that might be difficult for some readers, and provided overall comments based on the consultant's expertise. The Fry Readibility Formula applied to the introduction and to the section titled “Details about Today's Session” yielded an eighth grade reading level. Furthermore, in two pilot sessions participants provided verbal and written feedback on the introductory and report card pages, indicating areas that were confusing. The majority of pilot participants found the report cards “not at all” confusing. Of the three who found the report cards “somewhat” or “a lot” confusing, two participants stated that the source of their confusion was that they were forced to make difficult tradeoffs, which demonstrates comprehension of the purpose of the study. In the main sessions, we asked respondents to describe in their own words on paper the meaning of all six subheadings under “Technical Evaluation” and “Patient Experiences.” Ninety-four percent of respondents' answers were judged appropriate by two independent reviewers (κ=0.56).

A computer program randomized the order in which each participant viewed the seven pairs of report cards to minimize any effects of order. We also constructed two sets of report cards to minimize any bias that might occur from placement of different types of provider ratings (“Technical Evaluation” versus “Patient Experiences”) on the top versus the bottom of the report card. Participants in the odd- and even-numbered sessions saw report cards with alternate placement of provider ratings. Finally, we alphabetized categories in the first drill-down layer to avoid biases associated with order and carefully selected and paired physician names.

Sample Size

Our sample size (304) allowed excellent power to detect all but very small differences in preference within each pair of physicians. We had 93 percent power to detect a difference of 55 versus 45 percent and 80 percent power to detect a difference of 54 versus 46 percent between choices for a doctor who was better technically versus one who was better interpersonally.

Measures

Our main outcome measures were based on the participant's responses to each of the seven pairwise choices. These responses also enabled us to construct the dependent variable used in our multivariate analysis, the number of times the participant selected the physician who excelled in technical quality for the tradeoff pairs. Secondary measures were based on responses to our paper questionnaire, which assessed on a five-point response scale patients' trust in two sources of information (patient reports and medical charts/insurance claims) and the importance of each aspect of technical and interpersonal (patient experience) quality when looking for a new primary care physician.

For our independent variables, we collected demographic information from a paper questionnaire, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, computer use in the past year, income, and education. We categorized participants as having a chronic illness if they responded “yes” to at least one pair of questions adapted from CAHPS 2.0 Medicare Managed Care Questionnaire items on chronic conditions: “(1a). Have you ever seen any doctor, not just a primary care doctor, 3 or more times for the same condition? (1b). Was your visit for a condition that lasted at least 3 months? (2a). Do you need or take a prescribed medicine? (2b). Is this for a condition that has lasted at least 3 months?” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 1998). We asked participants to record the number of visits to the primary care physician in the past year and to indicate whether they were the primary caregiver or medical decision maker for another family member, friend, or neighbor who has a medical condition that has lasted longer than 3 months. We assessed on a five-point response scale participants' own evaluation of their understanding of the computerized task.

Statistical Analysis

Initial univariate analyses examined demographic variables. For each pair of physicians, we determined if the proportion of participants that selected each provider differed from chance alone (p=.5) at the α=0.05 level by using the one-sample binomial test of proportion (Stata, version 7). We also calculated the mean value for responses to the questions assessing patient attitudes on a five-point scale towards different dimensions of technical and interpersonal quality. We considered the mean to be the best single-number summary for descriptive purposes, because it is more precise than the median in capturing true differences in population medians for an ordinal scale with a small range of integers.

We used χ2 tests of independence to determine whether computer use was associated with the type of physician selected in the validity check and tradeoff pairs. We calculated the correlation coefficients between trust in different sources of information and our main outcome variable, the number of times the participant selected the physician who excelled in technical quality for the tradeoff pairs. We performed Wilcoxon's signed-rank tests to compare patients' trust in the two sources of information.

Finally, we estimated an ordered logit model to determine whether patient characteristics such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, chronic disease, number of visits to the primary care physician in the past year, caregiver status, subject understanding of the report cards (self-rated), computer use, income, and education were significant predictors of our main outcome variable, the number of times the participant selected the physician who excelled in technical quality for the tradeoff pairs (SAS, version 8).

Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of participants according to gender, age, race/ethnicity, educational level, health insurance, marital status, total combined family income in the past 12 months, computer use, employment status, caregiver status, number of PCP visits in past year, and chronic illness.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Sample (n=304)

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 153 (51) |

| Female | 150 (49) |

| Data missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–34 | 76 (25) |

| 35–49 | 76 (25) |

| 50–64 | 74 (24) |

| ≥65 | 77 (25) |

| Data missing | 1 (.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic caucasian | 79 (26) |

| Black | 65 (21) |

| Hispanic | 80 (26) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 67 (22) |

| Data missing | 13 (5) |

| Educational level | |

| <High school/GED | 18 (6) |

| High school/GED | 42 (14) |

| >High school, but <4 years college | 117 (39) |

| 4 years college | 80 (27) |

| >4 years college | 43 (14) |

| Data missing | 4 (1) |

| Health insurance (self-reported) | |

| Health maintenance organization | 157 (52) |

| Preferred provider organization | 84 (28) |

| Point-of-service | 8 (3) |

| Fee-for-service | 2 (1) |

| Veterans administration | 9 (3) |

| Uninsured | 20 (7) |

| Do not know | 15 (5) |

| Data missing | 9 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/life partner | 148 (49) |

| Widowed | 20 (7) |

| Divorced | 43 (14) |

| Separated | 6 (2) |

| Never married | 84 (28) |

| Data missing | 3 (1) |

| Total combined family income over past 12 months ($) | |

| <20,000 | 33 (11) |

| 20–34,999 | 43 (14) |

| 35–49,999 | 62 (20) |

| 50–64,999 | 48 (16) |

| 65–79,999 | 41 (13) |

| 80–94,999 | 23 (8) |

| 95–104,999 | 16 (5) |

| >105,000 | 34 (11) |

| Data missing | 4 (1) |

| Computer use | |

| Never | 30 (10) |

| One or two times | 7 (2) |

| Three to 11 times | 10 (3) |

| Once per month | 10 (3) |

| Once per week | 21 (7) |

| Daily | 225 (74) |

| Data missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time employed | 161 (54) |

| Part-time employed | 40 (13) |

| Retired | 40 (13) |

| Unemployed | 57 (19) |

| Data missing | 6 (2) |

| Chronic illness | |

| Yes | 206 (68) |

| No | 98 (32) |

| Caregiver status | |

| Yes | 76 (25) |

| No | 225 (74) |

| Data missing | 3 (1) |

| Number of primary care physician visits in past year | |

| None | 6 (2) |

| 1–3 visits | 145 (48) |

| 4–6 visits | 80 (26) |

| ≥7 | 71 (23) |

| Data missing | 2 (1) |

The two internal validity check pairs evaluated each participant's level of attention to the task. Ninety percent of participants chose the dominant provider both times, a figure consistent with the 90 percent of respondents who answered the dominant pair questions correctly in the conjoint analysis component of Phillips, Johnson, and Maddala's (2002) study on valuation. Infrequent computer users (computers less than once per month), who comprised 15 percent of the sample, were more likely to choose at least one nondominant physician in the validity check pairs (p<.0001).2

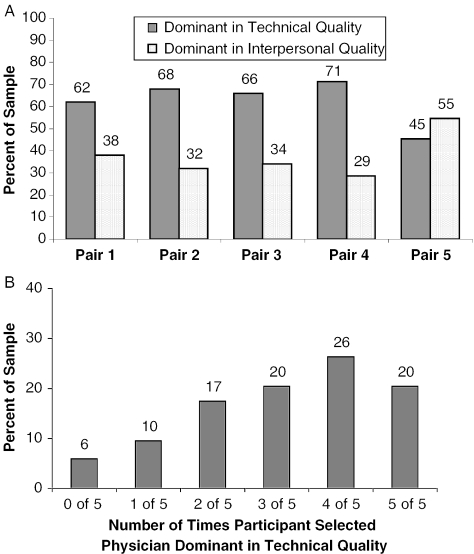

Figures 2A and B summarize the results of the tradeoff pairs. Two-thirds of our sample (95 percent CI: 62, 72 percent) chose the physician who excelled in technical care three or more times out of five, demonstrating an overall preference for technical quality of care. However, 33 percent (95 percent CI: 28, 38 percent) of the sample, chose the physician who excelled in interpersonal quality at least three times of five, suggesting that interpersonal quality was important for a substantial number of people in our sample. Figure 2A, which provides details about the choices participants made for each pair of physicians, also shows that the only pairing for which a majority of subjects did not choose the physician who excelled in technical quality was the one in which a physician average in both dimensions was paired with a physician with high technical and low interpersonal ratings (95 percent CI: 40, 51 percent).

Figure 2.

(A) Distribution of preferences for each of the five pairwise choices (n=304). Pair 1, HiT/AvgI (left) versus AvgT/Hi I (right); pair 2, HiT/LowI versus LowT/HiI; pair 3, AvgT/LowI versus LowT/AvgI; pair 4, AvgT/AvgI versus LowT/HiI; pair 5, HiT/LowI versus AvgT/AvgI (T, technical; I, interpersonal; Hi, high; Avg, average). (B) Distribution of preferences across five pairwise choices (n=304)

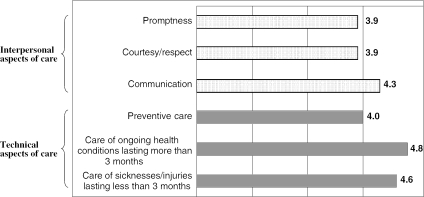

Figure 3, which displays mean values for the responses to the questions in the paper questionnaire that assessed attitudes towards different dimensions of technical and interpersonal quality, indicates that dimensions of both technical and interpersonal quality are important to subjects. For example, participants rated communication as at least as important as preventative care.

Figure 3.

Mean values for questions assessing attitude to different aspects of care (n=304)

Wilcoxon's signed-rank test results indicate that the median trust in expert review of medical records is significantly higher than for patient reports (p<.001), with the differences being most apparent at the highest levels of support (35 percent of participants trusting medical records “a lot,” as compared with 19 percent trusting patient reports “a lot”). Trust in expert review of medical records was correlated with trust in patient reports (r=0.34, p<.001), but neither of these variables was correlated with our main dependent variable, the number of times the participant selected the physician who excelled in technical quality for the tradeoff pairs (trust in expert review of medical records r=−0.04, p=.52; trust in patient reports r=0.08, p=.16).

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, caregiver status, number of physician visits in past year, chronic disease, subject understanding of hypothetical report cards, computer use, income, and education were not significant predictors of preference for technical quality at the α=0.05 level in our ordered logit model.

Discussion

The principal findings from our study are that participants use both technical and interpersonal quality ratings when selecting a PCP and that a majority clearly favors technical quality of care, but not to the exclusion of interpersonal quality. These findings provide insight into the values people place on technical and interpersonal quality when selecting a primary care physician. The results help us understand the choices people might make if they had comparative information about the technical and interpersonal quality of care of primary care physicians in their area.

Our results are directly relevant to the movement to develop and disseminate physician-specific report cards. Although when forced to make tradeoffs, the majority of our participants selected the physician who was higher in technical quality, approximately one-third of the participants chose the physician who was higher in interpersonal quality. In particular, half of participants chose a physician dominant in interpersonal quality when the alternative was a physician with poor interpersonal quality. These findings suggest that future report cards on primary care physicians should include measures of both technical and interpersonal quality and should display these measures in a clear manner. Existing health plan and hospital-level report cards do not consistently provide both types of measures or focus primarily on one type of measure. For example, NCQA's widely used online Health Plan Report Card, which contains the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set, consists primarily of technical process measures derived from review of records or claims data and interviews of health plan staff. Patient reports on interpersonal quality are included in only one domain, “Staying Healthy,” and are aggregated with technical measures. U.S. News and World Report's“Best Hospitals” report card also focuses primarily on technical outcome and volume measures such as mortality ratio and number of discharges rather than interpersonal measures (U.S. News and World Report 2003).

Since different sources may provide varying information about technical or interpersonal quality, one approach to producing more complete reporting systems would be to piece together information from two measurement systems (Scanlon et al. 1998) and display the information in a manner that helps patients make tradeoffs between them. Patients are the best source of data on interpersonal quality (Davies and Ware 1988), but are not generally used as a primary source of information to assess technical quality (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2004b). Medical records and administrative data are not good sources for assessing interpersonal quality, but can provide valuable information about technical quality. An example of combining both sources, thereby providing information on both aspects of quality, can be found on the Office of Personnel Management website, a website that provides federal employees with information such as health plans. This website displays Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey ratings on interpersonal quality and provides links to NCQA ratings (United States Office of Personnel Management 2003b).

Our results may also be relevant to primary care physicians, clinics, and health care systems that use provider profiling for internal quality improvement. Evidence suggests that measuring and feeding back data to individual providers, if tied to appropriate incentives, will change behavior on the items that are measured (Jha et al. 2003). Without a portfolio that contains both technical and interpersonal quality measures, such profiling systems will neglect aspects of care that patients value. Our study suggests that knowing patients' age, gender, and race/ethnicity may not help providers predict the aspect of care most important to patients under conditions in which patients are forced to make tradeoffs. Finally, these results may have relevance to medical education, which is strongly weighted towards teaching and rewarding technical aspects of care. Given our results regarding the value patients place on interpersonal aspects of care, additional effort at teaching effective interpersonal communication should prove beneficial.

The primary limitation of this study is that it assesses the decisions consumers make in response to hypothetical report cards under laboratory conditions rather than the decisions they might make in response to actual report cards under real-world conditions. A study that asks patients to choose a new primary care physician based on actual report cards is not currently possible, because physician report cards that contain information about both technical and interpersonal quality are not yet available to the public. The report cards tested in this study provide a starting basis to help design such a report card. Furthermore, a real-world study would need to be observational, since randomizing patients to physicians with poor-quality ratings might be considered unethical. A second limitation of our study is that it only included participants with a PCP and who lived in Los Angeles County and involved participants that had more frequent computer use than expected in the general population. We purposively chose participants with a PCP so our participants could draw on their personal experiences with their regular provider when interpreting the information to make their choices. Consumers without PCPs who might use report cards in the real world may not have these experiences to help them when interpreting report cards. Additional studies in other samples from the U.S., especially populations that have less computer experience and do not have a primary care physician, are also needed to evaluate the generalizability of the results reported here. Additional studies that test patient preferences for different aspects of care using paper report cards and different formats are also needed.

A third limitation is that the source of the information (medical records, claims data, and patient reports) is inextricably linked with the measured domain (technical and interpersonal). Indeed, our participants reported greater trust in ratings derived from medical records and claims data than ratings derived from patient experiences, but we found no correlation between trust in the source of the information and our main outcome variable, the number of times the participant selected the physician who excelled in technical quality for the tradeoff pairs. More research is also needed to provide an estimate of the correlation between technical and interpersonal quality of care when the two dimensions are measured validly and reliably using independent measures. Furthermore, the study did not assess patient preferences for specific dimensions of technical and interpersonal quality, because testing these dimensions separately, even by such methods as conjoint analysis, would have required participants to view a prohibitively large number of report cards and to make complex tradeoffs. Specific dimensions of quality may be more meaningful or important to some patients than overall measures of technical and interpersonal quality.

In summary, our study provides empirical evidence that patients value and will use information about both technical and interpersonal quality dimensions when choosing PCPs. We conclude that the content of future report cards on individual providers should include both aspects of quality to give patients information they value when choosing a new primary care physician and to focus internal quality improvement efforts on areas important to patients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the California Health Care Foundation. The California Health Care Foundation, based in Oakland, CA, is a nonprofit philanthropic organization whose mission is to expand access to affordable, quality health care for underserved individuals and communities, and to promote fundamental improvements in the health status of the people of California. Dr. Fung's salary was supported by an Ambulatory Care Fellowship from the VA. Drs. Fung and Shekelle are Staff Physicians at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. The authors thank Sue Phillips and Terry West for their help developing the computerized report cards, Mark Totten for his assistance programming, Sue Stableford of Clear Language Group for assessing the readability of the report card material, Roberto Lopez and Chi Vu for their assistance conducting the session, and Donna Mead for her assistance throughout the project. Financial Disclosures/Conflict of Interest: None. Research was supported by a research grant from a nonprofit organization. Information about the grant is available upon request to the authors.

Notes

“The Fry formula, which is validated for use with a wide range of materials, measures two items: syllables and sentence length. To use the formula, an individual randomly selects three 100-word passages from the document. Average number of syllables and average sentence length are plotted on the Fry graph to find a grade level. Materials with many multi-syllabic words and long sentences are harder to read and plot at higher grade levels on the graph.” (Fry, E. “Fry's Readability Graph: Clarifications, Validity, and Extension to Level 17.”Journal of Reading 21:242–52.)

Seventy percent of infrequent computer users chose the dominant physician for both validity check pairs, whereas 94 percent of frequent computer users chose the dominant physician for both validity check pairs.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality “Cahps 2.0 Medicare Managed Care Questionnaire, October 1998”. 1998. [accessed on May 10, 2004]. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/cahps/memcare.pdf.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality “CAHPS® and the National CAHPS® Benchmarking Database Fact Sheet”. 2004a. [accessed on April 11, 2004]. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/cahpfact.htm.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality “Frequently Asked Questions: CAHPS Questionnaire”. 2004b. [accessed on April 9, 2004]. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/cahps/faqtoc.htm.

- CAHPS-SUN “The Cahps® Survey Users Network”. [accessed on July 11, 2003]. Available at http://www.cahps-sun.org/home/index.asp.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services “Statement of the American Medical Association to the Practicing Physicians Advisory Council Re: Doctor's Office Quality (DOQ) Project: A Physician Level Measurement and Improvement Initiative”. 2003. [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/faca/ppac/amastmt.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services “Medicare Health Plan Compare”. 2004 [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://www.medicare.gov/mphCompare/home.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Damberg CL, Chung RE, Steimle A. The California Report on Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: 1997–1998 Hospital Data, Summary Report. San Francisco: Pacific Business Group on Health and the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, Ware JE. “Involving Consumers in Quality of Care Assessment.”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 1988;7(1):33–48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.7.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley DO, Short PF, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Brown JA, Hays RD. “Effects of CAHPS Health Plan Performance Information on Plan Choices by New Jersey Medicaid Beneficiaries.”. Health Services Research. 2002;37:985–1007. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.62.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher RH, O'Malley MS, Earp JA, Littleton TA, Fletcher SW, Greganti MA, Davidson RA, Taylor J. “Patients' Priorities for Medical Care.”. Medical Care. 1983;21(2):234–42. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi TK, Francis EC, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Haas JS, Brennan TA. “Inconsistent Report Cards: Assessing the Comparability of Various Measures of the Quality of Ambulatory Care.”. Medical Care. 2002;40:155–65. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. “Psychometric Properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 Adult Core Survey.”. Health Services Research. 2003;38(6):1509–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin LD, McCormack LA, Jael EF, Sangl JA, Garfinkel SA. “Creating More Effective Health Plan Quality Reports for Consumers: Lessons from a Synthesis of Qualitative Testing.”. Health Services Research. 2001;36:447–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Chong K, Brown J, Spritzer K, Horne K. “Patient Reports and Ratings of Individual Physicians: An Evaluation of the Doctor Guide and CAHPS Provider Level Surveys.”. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2003;18(5):190–6. doi: 10.1177/106286060301800503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Harris-Kojetin L, Mullin P, Lubalin J, Garfinkel S. “Increasing the Impact of Health Plan Report Cards by Addressing Consumers' Concerns.”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2000;19:138–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.5.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Peters E, Slovic P, Finucane ML, Tusler M. “Making Health Care Quality Reports Easier to Use.”. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 2001;27:591–604. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Jewett JJ. “Informing Consumer Decisions in Health Care: Implications from Decision-Making Research.”. Milbank Quarterly. 1997;75:395–414. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML. “Strategies for Reporting Health Plan Performance Information to Consumers: Evidence from Controlled Studies.”. Health Services Research. 2002;37:291–313. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett JJ, Hibbard JH. “Comprehension of Quality Care Indicators: Differences among Privately Insured, Publicly Insured, and Uninsured.”. Health Care Finance Reviews. 1996;18:75–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. “Effect of the Transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the Quality of Care.”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:2218–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HP, Van Horne F, Wensing M, Hearnshaw H, Grol R. “Which Aspects of General Practitioners' Behaviour Determine Patients' Evaluations of Care?”. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:1077–8. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Ritov I, Schkade D. “Economic Preferences or Attitude Expressions? An Analysis of Dollar Responses to Public Issues.”. In: Kahneman D, Tversky A, editors. Choices, Values, and Frames. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 642–71. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson DJ, Fowles JB, Finch M, McGee J, Dahms N, Kind EA, Adlis S. “Employer-Specific versus Community-Wide Report Cards: Is There a Difference?”. Health Care Financing Review. 1996;18:111–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. “The Public Release of Performance Data: What Do We Expect to Gain? A Review of the Evidence.”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:1866–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance “NCQA's Health Plan Report Card”. 2003. [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://hprc.ncqa.org/menu.asp.

- National Institutes of Health “Regulations and Ethical Guidelines: The Belmont Report Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research”. 1979. [accessed on August 18, 2004]. Available at http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/belmont.html.

- New York State Department of Health “New York State's Cardiac Surgery Reporting System”. 2003. [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://www.health.state.ny.us/nysdoh/heart/heart_disease.htm.

- Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council “Pennsylvania's Guide to Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery 2000”. 2002. [accessed on August 11, 2003]. Available at http://www.phc4.org/reports/cabg/00/default.htm.

- Phillips K, Johnson F, Maddala T. “Measuring What People Value: A Comparison of “Attitude” and “Preference. Health Services Research. 2002;37(6):1659–79. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, Rogers WH, Taira DH, Lieberman N, Ware JE. “The Primary Care Assessment Survey: Tests of Data Quality and Measurement Performance.”. Medical Care. 1998;36:728–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon DP, Chernew M, Mclaughlin C, Solon G. “The Impact of Health Plan Report Cards on Managed Care Enrollment.”. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21:19–41. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon DP, Chernew M, Sheffler S, Fendrick AM. “Health Plan Report Cards: Exploring Differences in Plan Ratings.”. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 1998;24:5–20. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauffler HH, Mordavsky JK. “Consumer Reports in Health Care: Do They Make a Difference?”. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22:69–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaller D, Sofaer S, Findlay SD, Hibbard JH, Lansky D, Delbanco S. “Consumers and Quality-Driven Health Care: A Call to Action.”. Health Affairs. 2003;22(2):95–101. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon L, Hays RD, Zaslavsky A, Cleary PD. “Psychometric Properties of the Group-Level Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (G-CAHPS®) Instrument.”. Medical Care. 2005;43:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Leapfrog Group Purchasers “The Leapfrog Group Purchasers/Role”. 2003. [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://www.leapfroggroup.org/purchase1.htm#B.

- The Pacific Business Group on Health “Healthscope”. 2003. [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://www.healthscope.org.

- U.S. News and World Report “Best Hospitals”. 2003. [accessed on April 12, 2004]. Available at http://www.usnews.com/usnews/nycu/health/hosptl/rankings/specihqotol.htm.

- United States Office of Personnel Management “Federal Employees Health Benefit Program”. 2003a. [accessed on June 9, 2003]. Available at http://fehb.opm.gov/03/spmt/plansearch.aspx.

- United States Office of Personnel Management “Satisfaction Surveys”. 2003b. [accessed on July 18, 2003]. Available at http://www.opm.gov/insure/health/quality/satisfaction.asp.

- Vaiana ME, McGlynn EA. “What Cognitive Science Tells Us about the Design of Reports for Consumers.”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2002;59:3–35. doi: 10.1177/107755870205900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Williams RG. “The Dr. Fox Effect: A Study of Lecturer Effectiveness and Ratings of Instruction.”. Journal of Medical Education. 1975;50:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensing M, Jung HP, Mainz J, Olesen F, Grol R. “A Systematic Review of the Literature on Patient Priorities for General Practice Care. Part 1: Description of the Research Domain.”. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:1573–88. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]