Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) encodes several proteins that inhibit major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-dependent antigen presentation. The HCMV products US2 and US11 are each sufficient for causing the dislocation of human and murine MHC class I heavy chains from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol, where the heavy chains are readily degraded. The apparent redundancy of US2 and US11 has been probed predominantly in cultured cell lines, where differences in their specificities were shown for murine and human MHC class I locus products. Here, we expressed US11 and US2 via adenovirus vectors and show that US11 exhibits a superior ability to degrade MHC class I molecules in primary human dendritic cells. MHC class II complexes are unaffected by US2- and US11-mediated attack. We suggest that multiple HCMV-encoded immunoevasions have evolved complementary functions in response to diverse host cell types and tissues.

The CD8+ T-cell response plays a key role in containing viral infections. Induction of a T-cell response requires the display of virus-derived peptides by host major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules. The ability to interfere with antigen presentation has been documented for a number of viruses, including human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (21). HCMV evades detection by the immune system by a variety of functions encoded by the genomic US and UL regions. Two of these gene products, US2 and US11, target class I heavy chains (HCs) for dislocation from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cytosol (23, 24). The HCs are then deglycosylated by N-glycanase and subsequently degraded by the proteasome. US2 and US11 are both ER-resident membrane glycoproteins, and they are expressed concomitantly during HCMV infection. Their general modes of action appear to be similar, but in mouse cells they differ in their abilities to attack allelic class I HC products (15). Perhaps in the human system, US2 and US11 also differ in specificity of interaction with class I molecules. Indeed, locus-specific preferences have been described: US2 and US11 mediate degradation of HLA-A and -B locus products but not HLA-C and -G locus products (18). Data obtained for a soluble, recombinant fragment of US2 likewise suggest differences in interaction with HLA-A and HLA-B locus products (9). Interestingly, a possible interaction between US2 and MHC class II products that results in downregulation of DM-α and DR-α has also been reported (20), although these observations were made with cells that do not normally express MHC class II molecules.

In vivo, HCMV infection can enhance MHC class I expression on bystander cells by induction and release of beta interferon. Therefore, a second possibility is that cooperation of US2 and US11 is necessary in vivo in secondary rounds of infection to overcome the increased MHC class I expression in newly infected cells (14).

In principle, multiple cell types can present antigen. HCMV can establish latency in hematopoietic progenitor cells and macrophages, while infection of dendritic cells (DCs) varies according to DC differentiation stage and HCMV strain studied (10, 13, 17, 19, 26). The importance of DCs for the initiation of antiviral T-cell responses results not only from their unique ability to capture antigen (2) but also from their susceptibility to virus infection itself.

To probe the efficiency and specificity of US2 and US11 in primary cells, we chose human DCs of myeloid origin. DCs express not only MHC class I HCs but also MHC class II proteins, whose expression is limited to professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs). A mature class II molecule is composed of an αβ heterodimer and an antigenic peptide (25). Loading of a peptide in the ER is precluded by the association of the αβ dimer with the invariant chain Ii. The αβIi complex is then transported to the trans-Golgi network and to lysosome-like compartments, where peptide is loaded in a reaction facilitated by HLA-DM. Interference with the class II antigen-presenting pathway could provide a selective advantage for HCMV. Upon phagocytosis or receptor-mediated endocytosis of virus particles or remnants of infected cells, virus-derived antigens intersect the class II secretory route. APCs would then display their virus-peptide cargo and activate CD4+ T cells.

Here we observed downregulation of class I molecules in human DCs. We demonstrate that US2 and US11 differ in their capacity to degrade class I HCs, with US11 being more effective. We could not confirm downregulation or degradation of MHC class II molecules in adenovirus US2-transduced DCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of human DCs.

DCs were prepared from peripheral blood mononuclear cells as previously described (22). Briefly, these cells were incubated (37°C and 5% CO2) in six-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/2 ml per well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 4 mM glutamine (Gibco BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany), 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco BRL) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), and 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml for 3 h. Nonadherent cells were gently washed out, and the remaining plastic-adherent cells were further cultured in medium containing 100 ng of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland) per ml and 1,000 U of interleukin 4 (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, N.J.) per ml. Cells were fed every other day with 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium containing the same amounts of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin 4. On day 7, nonadherent immature cells were rinsed off the plates and transferred to fresh six-well plates in the same medium. This fraction is further referred to as DCs.

Cell lines.

U373-MG astrocytoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin (1/1,000 dilution; 100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 2 mM glutamine at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2.

Antibodies.

Rabbit anti-class I HC serum recognizes nonassembled or unfolded HCs (23, 24). Rabbit anti-US2 serum and polyclonal anti-US11 serum were raised as described previously (23, 24). The HLA class II-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) TÜ35 (anti-DR and -DP), TÜ169 (anti-DQ), TÜ39 (anti-DR, -DP, and -DQ), TÜ36 (anti-DR), TÜ34 (anti-DR), and TÜ22 (anti-DQ) have been described before (27) (generously provided by Andreas Ziegler, Institute of Immunogenetics, Universitätsklinikum Charite, Berlin, Germany). MAb TAL.1B5 was obtained from Dako (Hamburg, Germany) (11). The Ii chain-specific MAb LN2 was obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.).

Generation of adenovirus vectors and transduction of DCs and cell lines.

Recombinant adenovirus (Ad) vectors encoding US11, US2, green fluorescent protein (GFP), and β-galactosidase (LacZ) all contain deletions in the E1 and E3 regions and are based on serotype 5. Briefly, a US11-encoding expression cassette containing a CMV immediate-early promoter and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal was blunt-end ligated into the shuttle vector pHVAd2 (obtained from Peter Löser, Devellogen AG, Berlin, Germany). Homologous recombination with the viral backbone vector pHVAd1 was performed with Escherichia coli strain BJ5183. A US2-encoding expression cassette under the same transcriptional control and polyadenylation site as US11 was subcloned into the shuttle vector pQBI-AdCMV5 (Qbiogene, Heidelberg, Germany). Homologous recombination was performed in HEK-293A cells. Ad-5CMVβ-GAL (Ad-LacZ), Ad-GFP, Ad-US2, and Ad-US11 were propagated on 293A cells and purified twice on cesium chloride gradients. Titrations were done as described elsewhere (5). Transduction of DCs and U373-MG cells was performed in 2% FCS Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium for 3 h or 90 min, respectively.

Flow-cytometric analysis.

For immunophenotyping of DCs at day 7 of culture, cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated MAbs specific for HLA class I, HLA-DR, CD80, CD83, CD86, CD19, CD3, CD14, CD4, CD8, CD1a, and CD11c (Pharmingen). According to these criteria and according to light-microscopic evaluation, 70 to 85% of the cells were DCs. Analysis of HLA class I (YTH862; Biozol, Eching, Germany) and HLA class II (TÜ36; Pharmingen) expression after adenovirus transduction was done after a 40-h infection period on a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). MAb YTH862 recognizes a monomorphic epitope on the α1 domain, shared by all HLA-A, -B, and -C antigens (8).

Pulse-chase experiments, immunoprecipitation, and gel electrophoresis.

Cells were incubated with methionine- and cysteine-free RPMI with or without the proteasome inhibitor ZL3H (25 μM) or ZL3VS (50 μM) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were labeled by incubation with 500 μCi of [35S]methionine-cysteine per 1 ml at 37°C for various times and chased with methionine and cysteine to final concentrations of 1.5 and 0.5 mM at 37°C for various periods. Cell lysis, immunoprecipitation, and endoglycosidase H (EndoH) digestion were done essentially as described elsewhere (23, 24). Reimmunoprecipitations for class II α chains were performed after denaturing of samples with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-phosphate-buffered saline and boiling. SDS was diluted with NP-40 containing lysis buffer before immunoprecipitation. All samples were boiled and analyzed by SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under reducing conditions.

Immunoblotting.

Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-12.5% PAGE and blotted to nitrocellulose. The blots were incubated with the first antibodies (see figure legends), followed by horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.) antibody. Bound antibody was visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL kit; Amersham-Pharmacia, Braunschweig, Germany).

In vitro transcription and translation.

In vitro transcription was performed essentially as described previously (12). cDNA constructs encoding HLA-A2 HC, β2 microglobulin (β2m), US2, and HLA-DR α and β chains were transcribed with either SP6 or T7 polymerase (Promega). In vitro translations in rabbit reticulocyte lysates and dog pancreas microsomes were essentially as described previously (12). Translations were performed for 1.5 to 2 h at 30°C and terminated by sedimentation of microsomes and lysis in 1% digitonin in 25 mM HEPES-150 mM potassium acetate, pH 7.7.

RESULTS

Adenoviral expression of US2 and US11 induces class I HC degradation in astrocytoma cells.

Most studies on the action of the immunomodulatory HCMV-encoded genes US2 and US11 have been performed on established human cell lines. The effects of isolated HCMV gene products on primary cells are not well understood. We therefore examined the ability of US2 and US11 to downregulate class I molecules in human DCs cultured from peripheral blood as described previously (22).

To drive expression of US2 and US11, we used recombinant adenoviruses. Among APCs infected by HCMV, human DCs in particular have been successfully transduced with adenovirus vectors, with efficiencies exceeding 90% at high multiplicities of infection (MOI) (6, 7).

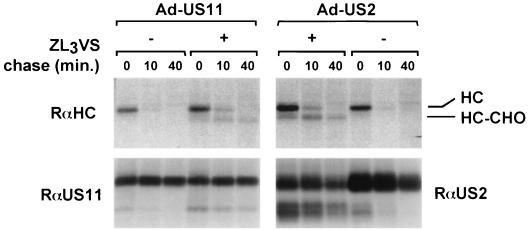

Recombinant adenovirus vectors encoding US2 and US11 were generated by homologous recombination and tested for their capacity to downregulate HLA class I in human U373-MG cells. The astrocytoma cell line U373-MG was chosen because it was employed previously (23, 24) to elucidate the mechanisms of US2- and US11-mediated MHC class I degradation. Furthermore, U373-MG cells are susceptible to adenovirus infection. These cells were infected with Ad-US11 or Ad-US2 at an MOI of 50 for 40 h. Transduced cells were then metabolically labeled in a pulse-chase experiment, and lysates of these cells were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-HC, -US2, or -US11 (Fig. 1) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The rabbit anti-HC antiserum recovered a deglycosylated intermediate after 10 and 40 min of chase only in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor ZL3VS, whereas in the absence of the inhibitor, fully glycosylated HCs rapidly disappeared. Both observations are indicative of a cytosolic disposition of the HC, prior to proteasomal degradation (23), as described for astrocytoma cells. US11 and US2 were both capable of degrading the human MHC class I HC, confirmed by flow-cytometric analysis of Ad-US2- and Ad-US11-transduced U373-MG cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Adenovirus-mediated transfer of US2 and US11 causes MHC class I destruction in MG-U373 cells. MG-U373 cells were infected with Ad-US2 or Ad-US11 at an MOI of 50 for 40 h. Cells were treated with ZL3VS, pulse-labeled for 5 min, and chased for the times indicated. Immunoprecipitations from NP-40 lysates were carried out with rabbit anti-US11 serum (RαUS11), anti-US2 serum (RαUS2), and anti-HC serum (RαHC). The precipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12.5%). The bands corresponding to glycosylated HC, deglycosylated HC (HC-CHO), US11, glycosylated US2, and deglycosylated US2 (US2-CHO) are labeled.

US11 efficiently targets MHC class I HCs for destruction in DCs.

HCMV-encoded US2 and US11 are each sufficient for causing the premature destruction of class I HCs. The apparent redundancy of US2 and US11 remains to be explained in terms of a selective advantage for HCMV in the course of a natural infection.

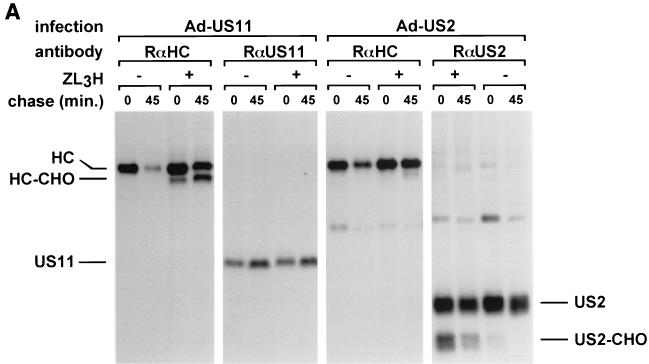

After establishing full reactivity of recombinantly expressed US2 and US11 in U373-MG astrocytoma cells, we compared the effects of US2 and US11 in human DCs. Human DCs were infected with Ad-US2 or Ad-US11 at the same MOI (Fig. 2A). Cells were metabolically labeled in a pulse-chase experiment in the presence of ZL3H, which retards the degradation of dislocated class I HCs and results in the cytosolic accumulation of an unfolded, deglycosylated HC intermediate. Comparable amounts of biosynthetically labeled US2 and US11 were recovered in all experiments. The rabbit anti-HC antibody recovered a deglycosylated intermediate in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor in US2- and US11-infected DCs. In contrast to US2-infected DCs, the deglycosylated HC was observed in US11-infected cells at the beginning of the chase and accumulated after 45 min of chase. The ratio of fully glycosylated HC to deglycosylated intermediate at the later chase point was approximately 1:1. US2 infection generated a smaller amount of deglycosylated HC intermediates, as visualized by the accumulation of deglycosylated intermediate at the later chase point only. The ratio of intact HC to intermediate was estimated to be at least 5:1. In addition, immunoblotting of transduced DCs and U373-MG was performed to compare total expression rates of US2 and US11 (Fig. 2B) at the same MOI. At steady state, expression levels of US11 were higher in both cell populations, yet US11 exhibited significantly stronger HC dislocation activity in DCs. This difference in US2 and US11 expression is best explained by the difference in the half-lives of US2 and US11. Whereas US11 is relatively long lived (half-life of >2 h) (data not shown), US2 itself is more rapidly degraded. Although the US2 and US11 quantification in both DCs and U373-MG cells is only semiquantitative, the ratios of US2 and US11 in U373-MG cells and DCs are similar. Therefore, the differences in degradation efficiency between cell populations cannot be accounted for by different expression levels of US2 and US11. Even after infection of native human fetal fibroblasts with HCMV strain Ad169 we observed strong expression of US11 and only marginal expression of US2, as measured by immunoblotting (data not shown). Nevertheless, deletion mutants of HCMV strain Ad169 have proven that US2 alone is fully competent to cause rapid class I degradation (14).

FIG. 2.

US2 and US11 differ in their ability to attack MHC class I HC in DCs. (A) DCs were infected with Ad-US2 or Ad-US11 at an MOI of 500 for 40 h. Cells were labeled for 10 min in the presence of ZL3H and chased for the times indicated. HC were recovered with rabbit anti-HC serum and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The breakdown intermediate is indicated as HC-CHO. (B) DCs were infected with Ad-US2 or Ad-US11 at MOIs of 300 and 500 for 40 h; equal numbers of cells were directly lysed in SDS sample buffer and loaded on SDS-PAGE. Likewise, U373-MG cells were infected with Ad-US2 or Ad-US11 at MOIs of 20 and 50 and processed as before. Proteins were separated and transferred to nitrocellulose. Immunoblotting was performed with rabbit anti-US2 and -US11 antisera.

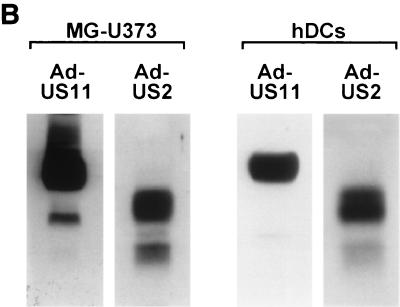

Analysis by immunostaining and flow cytometry was largely confirmatory of the results obtained in immunoprecipitation and pulse-chase experiments (Fig. 3). Even at an MOI of 1,200, Ad-US2 infection in DCs led to only modest downregulation of HLA class I antigens. In contrast, Ad-US11 at an MOI between 300 and 500 induced a 80% (±15%) reduction of HLA class I expression. Double infection with Ad-US2 and Ad-US11 had no additive effect and did not exceed the immunomodulatory capacity of US11 infection alone. We can largely exclude the idea that the differential effects of US2 and US11 in human DCs are due to differential recognition of HLA class I alleles, since the antibody employed, YTH862, recognizes a monomorphic epitope on the α1 domain, shared by all HLA-A, -B, and -C antigens. Furthermore, we obtained identical results with a second HLA class I-specific monomorphic reagent, G46-2.6 (Pharmingen), not known to have allelic preferences (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Surface expression of MHC class I complexes in Ad-US2-transduced DCs is only modestly downregulated. DCs were left uninfected, infected with Ad-GFP (MOI, 500), Ad-US2 (MOI, 1,200), Ad-US11 (MOI, 500) or a combination of Ad-US11 and Ad-US2 (MOI, 500 each). Cells were analyzed by immunostaining with YTH862 (HLA class I) and TÜ36 (HLA class II), followed by flow cytometry. All antibodies used were purified and biotinylated, and streptavidin-phycoerythrin served as the fluorescence marker.

Given the rather similar rates of synthesis for US2 and US11, it appears that in human DCs US11 is more efficient at dislocating class I molecules than US2.

MHC class II molecules are unaffected by US2 mediated degradation.

US2 has been claimed to cause degradation of two components of the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway, DR-α and DM-α. (20). This observation was further examined in human DCs. DCs express MHC class II antigens in abundance and provide a natural host for HCMV infection and persistence.

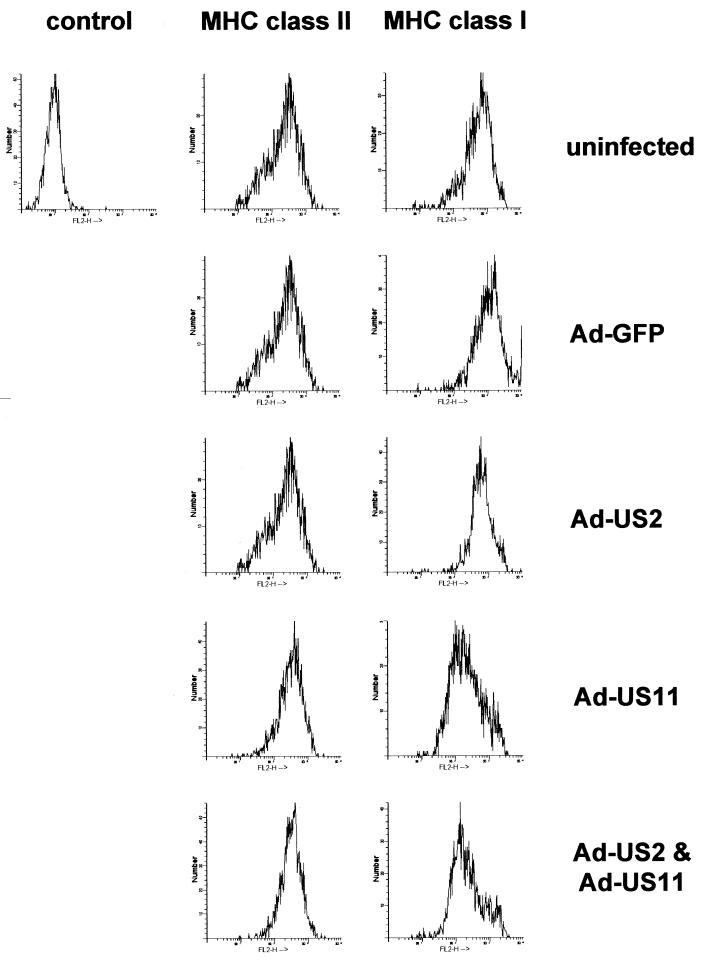

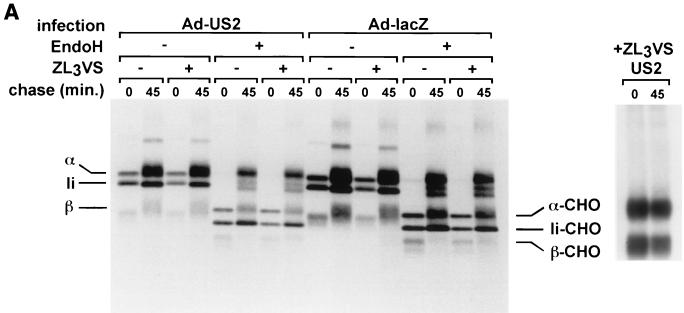

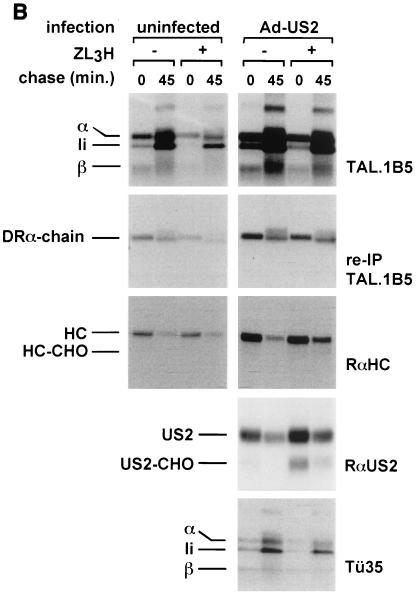

DCs were transduced with either Ad-US2 or Ad-LacZ, and infected cells were metabolically labeled in a pulse-chase experiment (Fig. 4A). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-DR antibody TÜ36, and the precipitates were subjected to EndoH treatment. TÜ36 recognizes fully assembled DR complexes only; therefore, free α chains and their degradation products might escape detection (see below). In DCs, we observed stable expression of properly conformed class II complexes with no evidence for deglycosylated intermediates.

FIG. 4.

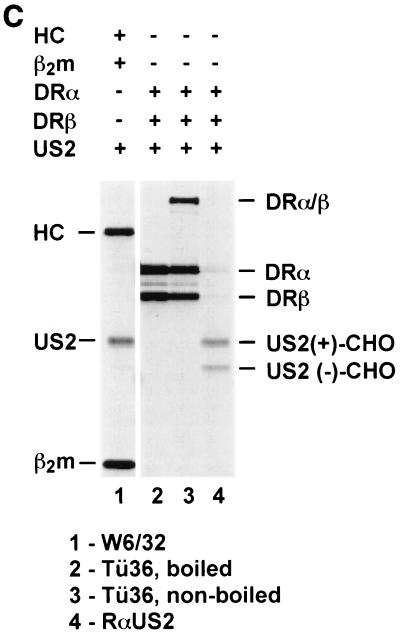

DR-α chains remain stable in Ad-US2-transduced DCs. (A) DCs were infected with Ad-US2 or Ad-LacZ (β-galactosidase) at an MOI of 500 for 40 h. Cells were metabolically pulse-labeled for 10 min in the presence of ZL3VS and chased for 45 min. NP-40 lysates were immunoprecipitated with TÜ36 (reactive with αβ dimers and αβIi complexes) and rabbit anti-US2 serum (RαUS2). TÜ36 lysates were treated with EndoH or mock treated. (B) DCs were infected with Ad-US2 at an MOI of 500 or left uninfected for 40 h. Cells were treated with ZL3H, radiolabeled for 10 min, and chased for the times indicated. The amounts of radioactivity incorporated in uninfected and Ad-US2-infected DCs were not normalized. NP-40 lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with antibodies indicated. TAL.1B5 immunoprecipitates were divided; one aliquot was loaded directly for SDS-PAGE, and a corresponding aliquot was reimmunoprecipitated with TAL.1B5. In contrast to MHC class I HC, DR-α chains remain unaffected by US2. (C) In vitro-translated US2 associates with cotranslated MHC class I HC and β2m but not with cotranslated DR-α or β chains. HLA-A2 HC was cotranslated in vitro with human β2m and US2 in the presence of pancreas microsomes. Radiolabeled translation products were recovered with W6/32, which recognizes properly conformed MHC class I complexes. Correspondingly, US2 was cotranslated at optimized amounts with DR-α and DR-β. DR complexes were recovered with TÜ36 and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

In a separate pulse-chase experiment, DCs were left uninfected or transduced with Ad-US2 at an MOI of 500 (Fig. 4B). To further evaluate the fate of free DR-α chains, immunoprecipitations were first performed with MAb TAL.1B5, a reagent capable of interacting with free DR-α chains as well as with assembled DR products. After dissociation of the αβIi complex by SDS denaturation, α chains were reimmunoprecipitated with the same antibody. In contrast to the result for MHC class I HCs, we could not detect deglycosylated DR-α chain intermediates. Flow-cytometric analysis of DCs infected with Ad-US2, Ad-LacZ, Ad-GFP, or uninfected DCs confirmed the data obtained in pulse-chase analysis and immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3) and showed no alteration in surface class II levels. A panel of nine MHC class II locus-specific MAbs was tested in immunoprecipitation and pulse-chase analysis to exclude the possibility that other MHC class II-derived chains or invariant chain were subject to US2-mediated dislocation (data shown for TÜ36, TÜ35, and TAL.1B5; see also Table 1). We conclude that the products of the DR-α and β loci, DP and DQ complexes, were resistant to rapid degradation in primary human DCs.

TABLE 1.

Reactivity of MAbs with distinct HLA class II antigens

| MAb | Reactivitya with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR | HLA-DP | HLA-DQ | Invariant chain | |

| TÜ35 | +, all | +, all | − | − |

| TAL.1B5 | +, also single α chain | − | − | − |

| TÜ169 | − | − | +, some | − |

| TÜ39 | +, all | + | + | − |

| TÜ36 | +, all | − | − | − |

| TÜ34 | +, all | − | − | − |

| TÜ22 | − | − | +, all | − |

| LN2 | − | − | − | + |

| DR β chain | + | − | − | − |

Nine MAbs specific for HLA class II molecules were tested in immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4) for downregulation of class II complexes or single α, β, and Ii chains. Their allospecificities comprise DR, DP, and DQ locus products as well as invariant chain. Essentially no degradation products or loss of class II complexes was observed in the presence of US2.

In vitro cotranslation of US2, β2m, and HLA-A2 HCs resulted in coprecipitation of the complex under conditions of mild-detergent solubilization, indicating a physical and functional association of these three components upon the dislocation process (Fig. 4C). In contrast, a specific coprecipitation of HLA-DR-α chain and US2 was not observed. Translation conditions have been optimized. Under such conditions US2 binds to MHC class I HCs but not to class II α or β chains.

This observation argues against a specific association of US2 and DR-α, which is a prerequisite for dislocation.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here are of interest for several aspects of HCMV biology. HCMV targets CD34+ stem cells, endothelial cells, glial cells, and monocytes/macrophages but also DCs, which are key APCs in host defense (2, 10, 13, 17, 19, 26). Therefore, the ability to block class I and class II antigen presentation pathways would be beneficial for the virus to escape both a CD8+ and a CD4+ T-cell response. US2 has been claimed to cause degradation of two components of the class II antigen presentation pathway, DR-α and DM-α. (20). This result was surprising in view of the limited sequence homology between class I HC and DR-α. However, overall structural similarities (25) might allow an association of US2 with both class I and class II molecules. We were nonetheless unable to confirm an effect of US2 on the stability of class II molecules in primary human DCs. How is this discrepancy explained?

The study by Tomazin et al. (20) made use of a transformed glioblastoma cell line, U373-MG, which was induced to express class II by either gamma interferon or transfection of the transcriptional transactivator CIITA. Transactivation by CIITA might not necessarily result in the appropriate ratios of α, β, and Ii chains, thereby causing an unfolded-protein response and degradation of unincorporated single α chains (16) by a mechanism that may be independent of US2. We chose DCs which are permissive for HCMV infection in vivo as well as for adenovirus transduction in vitro. Even if class II degradation had escaped detection in biochemical analysis, surface staining of DCs after Ad-US2 infection also failed to reveal a reduction in the expression of HLA-DR. Although the maturation state of DCs can affect the expression and turnover of MHC class II molecules on the surfaces of human DCs (4), we have employed biosynthetic labeling to score for the fate of newly synthesized class II molecules. This readout is largely independent of maturation state and provides sufficient information on the interaction of MHC class II antigens with US2. We can thus exclude a modulatory effect of US2 on the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway in DCs. The levels of class II subunit expression obtained in U373-MG cells are difficult to compare to the levels seen in cells that are naturally class II positive.

An alternative explanation for the observed discrepancy between our results and those reported by Tomazin et al. would be to invoke a cell type-specific effect on degradation and dislocation of class II molecules. It is conceivable that the dislocation apparatus in astrocytoma cells is competent to engage a US2-class II α complex, whereas in DCs this is not the case. Regardless, it appears to be important to examine other cell types that naturally express class II molecules for the consequences of US2 expression as we have done for primary human DCs.

Consistent with the possibility that US2 and US11 may have been preserved by HCMV to carry out their functions with different efficiencies in distinct cell types, we found that US2 and US11 are not equally active in DCs. Over the chase period examined, US11 degraded class I HC at about 50% efficiency, whereas US2 led only to a moderate accumulation of deglycosylated HC intermediates. Differences in levels of expression of US2 and US11 are unlikely to account for this effect. Likewise, the moderate efficiency of US2 in DCs, compared to its effect in U373-MG cells, might also influence the rate of class II degradation in DCs. Notwithstanding the need for a detailed analysis for cell type-specific factors that affect dislocation, we conclude that the physiological relevance of our test system points to complementary effects of several immunomodulatory HCMV gene products in vivo, among them US2 and US11 and by inference US3 and US6 (1).

In addition to these considerations, there are structural reasons why the class II α chains are less appealing substrates than class I HCs. The class II β chains are in fact more similar structurally to class I HC than are class II α chains (3).

Multiple viral immunoevasions may have evolved not only to cover the sequence variability between different MHC class I alleles but also as an evolutionary consequence of diverse host cell types and tissues as HCMV-susceptible targets. Our analysis provides a starting point for a more systematic delineation of isolated HCMV immunoevasions in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Ziegler for providing us with HLA class II antibodies and B. Dörken and M. Lipp for critically reading the manuscript. We appreciate the assistance of K. Krüger in generating DCs.

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (RE 1103/2-2). D.T. is a Charles A. King Trust postdoctoral fellow.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, K., A. Angulo, P. Ghazal, P. A. Peterson, Y. Yang, and K. Früh. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits antigen presentation by a sequential multistep process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10990-10995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, J. H., T. S. Jardetzky, J. C. Gorga, L. J. Stern, R. G. Urban, J. Strominger, and D. C. Wiley. 1993. Three-dimensional structure of the human class II histocompatibility antigen HLA-DR1. Nature 364:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cella, M., A. Engering, V. Pinet, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1997. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature 388:782-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cichon, G., H. H. Schmidt, T. Benhidjeb, P. Löser, S. Ziemer, R. Haas, N. Grewe, F. Schnieders, J. Heeren, M. P. Manns, P. M. Schlag, and M. Strauss. 1999. Intravenous administration of recombinant adenoviruses causes thrombocytopenia, anemia and erythroblastosis in rabbits. J. Gene Med. 1:360-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diao, J., J. A. Smythe, C. Smyth, P. B. Rowe, and I. E. Alexander. 1999. Human PBMC-derived dendritic cells transduced with an adenovirus vector induce cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses against a vector-encoded antigen in vitro. Gene Ther. 6:845-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz, A. B., and S. Vuk-Pavlovic. 1998. High efficiency adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to human dendritic cells. Blood 91:392-398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genestier, L., G. Meffre, P. Garrone, J.-J. Pin, Y.-J. Liu, J. Banchereau, and J.-P. Revillard. 1997. Antibodies to HLA class I α1 domain trigger apoptosis of CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. Blood 90:726-735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gewurz, B. E., E. W. Wang, D. Tortorella, D. J. Schust, and H. L. Ploegh. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus US2 endoplasmic reticulum-lumenal domain dictates association with major histocompatibility complex class I in a locus-specific manner. J. Virol. 75:5197-5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn, G., R. Jores, and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3937-3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horibe, K., N. Flomenberg, M. S. Pollack, T. E. Adams, B. Dupont, and R. W. Knowles. 1984. Biochemical and functional evidence that an MT3 supertypic determinant defined by a monoclonal antibody is carried on the DR molecule on HLA-DR7 cell lines. J. Immunol. 133:3195-3202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huppa, J., and H. Ploegh. 1997. In vitro translation and assembly of a complete T cell receptor-CD3 complex. J. Exp. Med. 186:393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahn, G., S. Stenglein, S. Riegler, H. Einsele, and C. Sinzger. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus infection of immature dendritic cells and macrophages. Intervirology 42:365-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, T. R., L. K. Hanson, L. Sun, J. S. Slater, R. M. Stenberg, and A. E. Campbell. 1995. Multiple independent loci within the human cytomegalovirus unique short region down-regulate expression of major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. J. Virol. 69:4830-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machold, R. P., E. J. H. J. Wiertz, T. R. Jones, and H. L. Ploegh. 1997. The HCMV gene products US11 and US2 differ in their ability to attack allelic forms of murine histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I HCs. J. Exp. Med. 185:363-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori, K. 2000. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 101:451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riegler, S., H. Hebart, H. Einsele, P. Brossart, G. Jahn, and C. Sinzger. 2000. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells are permissive to the complete replicative cycle of human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 81:393-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schust, D. J., D. Tortorella, J. Seebach, C. Phan, and H. L. Ploegh. 1998. The trophoblast class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) products are resistant to rapid degradation imposed by the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) gene products US2 and US11. J. Exp. Med. 188:497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Söderberg-Naucler, C., K. N. Fish, and J. A. Nelson. 1998. Growth of human cytomegalovirus in primary macrophages. Methods 16:126-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomazin, R., J. Boname, N. R. Hedge, D. M. Lewinsohn, Y. Altschuler, T. R. Jones, P. Cresswell, J. A. Nelson, S. R. Riddell, and D. C. Johnson. 1999. Cytomegalovirus US2 destroys two components of the MHC class II pathway, preventing recognition by CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 5:1039-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tortorella, D., B. E. Gewurz, M. H. Furman, D. J. Schust, and H. L. Ploegh. 2000. Viral subversion of the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:861-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westermann, J., A. Aicher, Z. Qin, S. Cayeux, K. Daemen, T. Blankenstein, B. Dörken, and A. Pezzutto. 1998. Retroviral interleukin-7 gene transfer into human dendritic cells enhances T cell activation. Gene Ther. 5:264-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiertz, E. J. H. J., T. R. Jones, L. Sun, M. Bogyo, H. J. Geuze, and H. L. Ploegh. 1996. The human cytomegalovirus US11 gene product dislocates MHC class I HCs from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Cell 84:769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiertz, E. J. H. J., D. Tortorella, M. Bogyo, J. Wu, W. Mothes, T. R. Jones, T. A. Rapoport, and H. L. Ploegh. 1996. Sec61-mediated transfer of a membrane protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the proteasome for destruction. Nature 384:432-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf, P. R., and H. L. Ploegh. 1995. How MHC class II molecules acquire peptide cargo: biosynthesis and trafficking through the endocytic pathway. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:267-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhuravskaya, T., J. P. Maciejewski, D. M. Netski, E. Bruening, F. R. Mackintosh, and S. St. Jeor. 1997. Spread of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) after infection of human hematopoietic progenitor cells: model of HCMV latency. Blood 90:2482-2491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegler, A., J. Heinig, C. Müller, H. Götz, F. P. Thinnes, B. Uchanska-Ziegler, and P. Wernet. 1986. Analysis by sequential immunoprecipitations of the specificities of the MAbs TÜ22, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 43, 58 and YD1/63.HLK directed against human HLA class II antigens. Immunobiology 171:77-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]