Abstract

Objective

Patients in the U.S. often turn to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and may use it concurrently with conventional medicine to treat illness and promote wellness. However, clinicians vary in their openness to the merging of treatment paradigms. Because integration of CAM with conventional medicine can have important implications for health care, we developed a survey instrument to assess clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine.

Study Setting

A convenience sample of 294 acupuncturists, chiropractors, primary care physicians, and physician acupuncturists in academic and community settings in California.

Data Collection Methods

We used a qualitative analysis of structured interviews to develop a conceptual model of integrative medicine at the provider level. Based on this conceptual model, we developed a 30-item survey (IM-30) to assess five domains of clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine: openness, readiness to refer, learning from alternate paradigms, patient-centered care, and safety of integration.

Principal Findings

Two hundred and two clinicians (69 percent response rate) returned the survey. The internal consistency reliability for the 30-item total scale and the five subscales ranged from 0.71 to 0.90. Item-scale correlations for the five subscales were higher for the hypothesized subscale than other subscales 75 percent or more of the time. Construct validity was supported by the association of the IM-30 total scale score (0–100 possible range, with a higher score indicative of greater orientation toward integrative medicine) with hypothesized constructs: physician acupuncturists scored higher than physicians (71 versus 50, p<.001), dual-trained practitioners scored higher than single-trained practitioners (71 versus 62, p<.001), and practitioners' self-perceived “integrativeness” was significantly correlated (r=0.60, p<.001) with the IM-30 total score.

Conclusion

This study provides support for the reliability and validity of the IM-30 as a measure of clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine. The IM-30 survey, which we estimate as requiring 5 minutes to complete, can be administered to both conventional and CAM clinicians.

Keywords: Integrative medicine, complementary and alternative medicine, clinicians' orientation, reliability, validity

Patients commonly use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in combination with conventional medical treatment outside the purview of their physicians (Eisenberg, Davis, and Ettner 1998). Such patient-initiated “integrative medicine” has the potential for adverse effects, evidenced by the rising reports of adverse herb–drug interactions (Fugh-Berman 2000). A lack of perceived openness between patients and their physicians may contribute to patients not sharing information with their physicians and may result in poor coordination between clinician-initiated therapies and those patients start on their own (Mootz and Bielinski 2001; Hsiao, Wong, and Kanouse 2003). Thus, clinicians' attitudes toward integrative medicine may play an important role in patient safety.

Contrary to presenting a hazard, some clinicians and researchers hypothesize that actively combining CAM and conventional medicine by practicing integrative medicine is more cost-effective and safer than either conventional medicine or CAM alone (Pelletier, Astin, and Haskell 1999; Weil 2000). However, the few small studies to date have not supported these assertions (Cherkin and Barlow 1998; Fugh-Berman 2000; Ernst 2002). Investigation in this area has been impeded by a lack of consensus on the definition and measurement of integrative medicine. For example, acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation combined with exercise was found to be ineffective in treating chronic low back pain (Deyo et al. 1990). In contrast, acupuncture combined with physical therapy was found to be an effective approach for this condition (Gunn, Milbrndt, and Little 1980). The contradictory nature of these results could stem from differences in the way in which clinicians practice and integrate CAM with conventional therapy (Weeks 1996; Mootz and Bielinski 2001).

The conventional and CAM literature does not suggest a unified conceptual framework to operationalize integrative medicine. Bell et al. (2002) viewed integrative medicine as a new medical paradigm and defined it as “a comprehensive, primary care system that emphasizes wellness and healing of the whole person (bio-psycho-socio-spiritual dimensions) as major goals, above and beyond suppression of a specific somatic disease.” In this model, the patient and the integrative practitioner are partners in the development and implementation of a comprehensive treatment plan. Kailin (2001) conceptualized integrative medicine using an organizational systems model that takes into account all members who have a vested interest in the welfare of the organization. Another model views integrative medicine from an economic perspective (Weeks 1996). Although various researchers have endeavored to define integrative medicine, the lack of an operational definition has impeded the study of this construct.

Fundamental to the assessment of integrative medicine's impact on health care processes and outcomes is construction of a definition and a method of measurement of integrative medicine at the provider level. Clinicians' “orientation” toward integrative medicine is defined as their attitudes toward and practice of merging conventional and CAM modalities. Clinicians' attitudes toward integrative medicine may be influenced by numerous factors, such as their training, education, and practice setting, which will in turn affect how clinicians practice integrative medicine (Weil 2000; Weeks 2001). Since clinicians' attitudes toward integrative medicine may span a continuum from highly negative to highly positive, we need an instrument that can distinguish the level of clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine across its various dimensions.

No reliable and valid instrument to measure integrative medicine at the provider level is currently available. The Integrative Medicine Attitude Questionnaire measures a physician's attitude toward integrative medicine, but this instrument does not address the CAM practitioners' perspective (Schneider, Meek, and Bell 2003). Another tool incorporates conventional and CAM practitioners' perspectives, but fails to capture various dimensions of attitudes toward integrative medicine, education, training, and practice (Long, Mercer, and Hughes 2000). These existing measures do not adequately cover the dimensions of integrative medicine or the variety of applicable practitioners. We describe the development and psychometric assessment of a self-administered survey instrument to assess clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine.

Methods

Because we were unable to locate a comprehensive conceptual model of clinicians' “orientation” toward integrative medicine, we used a grounded, qualitative method, using semi-structured interviews, to develop a conceptual model of integrative medicine (Bernard 2002). We then developed a survey, based on the interview results, to measure this construct. Lastly, we administered the revised survey instrument to a convenience sample of conventional and CAM health care practitioners to assess its reliability and validity. The UCLA Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Semi-Structured Interview

We used semi-structured interviews to elicit relational data across practitioners because the interviewer can deeply probe and openly explore practitioner attitudes and behaviors toward integrative medicine. This method was selected rather than conducting focus groups in order to maximize participant response variance (Bauman and Adair 1992). In addition, focus groups suffer from lack of independence among participants and unequal participation. In contrast, the semi-structured interview is able to elicit complete and independent data from all participants.

In-depth interviews were conducted using a standard interview guide (Bauman and Adair 1992), consisting of open-ended questions with probes for clarification and additional detail. Following the layout of a “funnel” interview, the conversation started with broad topics and then probed each response. The interview began with the standard “grand tour” (Bernard 2002) question by asking: “What does integrative medicine mean to you?” If, for example, the respondent answered that integrative medicine is defined by using the best of traditional Chinese medicine and western medicine, then the subject was asked more focused questions, such as “What types of practitioners would provide this care? How would these two types of medicine be mixed?” The interviewer continued to ask narrower questions until the informant exhausted all responses or the topic changed.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of 50 health care practitioners: 13 physicians, 13 physician acupuncturists (physicians who also completed acupuncture training), 12 chiropractors, and 12 acupuncturists. Two investigators (A. H. and G. R.) reviewed the 50 transcripts and agreed that theoretical saturation was reached. Equal distribution across clinician groups aimed to yield maximal variance of provider attitudes and behaviors concerning integrative medicine. The mean duration of each interview was 30 minutes (range 20–55 minutes). Interview audiotapes were transcribed. The validity of the transcription process was assessed by reviewing the match of audiotape to transcript.

Free Pile Sorting

To identify key dimensions of integrative medicine, we used an exploratory technique (Lincoln and Guba 1985) in which transcripts were read to uncover “core statements” that represent key constructs of a practitioner's orientation toward integrative medicine. We printed these core statements onto cards. All core statements were laid on a large table. Three investigators (A. H., G. R., and N. W.) free pile sorted the core statements into similar groups or themes; this initial pile sorting was followed by a group discussion to produce consensus. After multiple iterations of free pile sorting with these pairs of researchers, we found four domains and 11 subdomains representing the key dimensions of clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine.

A Conceptual Model of Integrative Medicine at the Provider Level

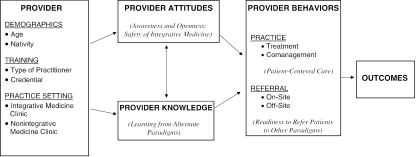

Our qualitative analysis uncovered four key domains of integrative medicine: provider attitudes, knowledge, referral, and practice. Provider training and practice setting also emerged as important factors in determining clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine. Based on the relationships among provider attitudes, provider knowledge, provider behaviors, and other factors, we developed a conceptual model of integrative medicine at the provider level that was grounded in the interview results (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model of Integrative Medical Care at the Provider Level

Note: Corresponding IM-30 subscale (s) for each domain is given in italics.

Cognitive Interviews

We developed a 63-item initial version of the survey to measure clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine based on the key domains of integrative medicine. Survey items were constructed directly from phrasing found in the core statements. Response categories to survey items assessing clinicians' attitudes toward integrative medicine consisted of a 4-point categorical response scale (strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree). Response categories to survey items about clinicians' practice of integrative medicine consisted of a 5-point categorical response scale reflecting the frequency of the behavior (never, rarely, sometimes, often, or always). Items asking about sources of education had response options on a 5-point scale, ranging from “more than once a week” to “never.”

Survey items were evaluated by conducting cognitive interviews with 10 practitioners who had not participated in the semi-structured interview. This technique is designed to increase the quality of self-reported data obtained through questionnaires by querying respondents about the meaning of questions and using feedback to refine item wording. Respondents were encouraged to verbalize their thought processes aloud as they comprehended and responded to survey items. Information obtained from these interviews also identified skip pattern inconsistencies and difficulties with question order. Based on the cognitive interviews, we revised the items and produced a 56-item version for the field test.

Field Test of Survey

The revised 56-item version of the survey, supplemented with questions about demographics, practice setting, and training, was mailed to a convenience sample of 294 practitioners. This sample included the 50 practitioners who had participated in the interviews plus an additional 71 primary care physicians, 58 physician acupuncturists, 55 chiropractors, and 60 acupuncturists. The survey was accompanied by a letter of introduction, a $10 honorarium, and an information sheet. Participants provided consent to participate by completing the survey instrument.

Data Analysis

We used multitrait scaling analysis to evaluate the field test items (Hays and Hyashi 1990). In multitrait scaling analysis, item-scale correlations are examined to evaluate whether each item correlates more highly with its hypothesized scale (corrected for item overlap with the scale) than with the other scales. We eliminated items with low correlations with their hypothesized scale (domain) and combined scales with poor item discrimination. Specifically, we eliminated four items with correlations less than 0.30 with their hypothesized scales (Stewart, Hays, and Ware 1992), eight redundant items that overlapped with items having higher item-scale correlations, and 14 items that were correlated weakly with all scales. Several scales were collapsed because of weak item discrimination. Items derived from the pile sorting domains of Comanagement and Practice style were collapsed into a single “Readiness to refer patients” subscale; items from two domains focusing on proficiency and training were collapsed into a “Learning from alternate paradigms” subscale.

The final instrument consisted of 30 items comprising five scales: awareness and openness to working with practitioners from other paradigms (10 items), readiness to refer patients to other paradigms (7 items), learning from alternate paradigms (5 items), patient-centered care (3 items), and safety of integrative medicine (5 items). We conducted all subsequent psychometric analyses on the 30-item (IM-30) survey.

Mean scores for the IM-30 as well as for each subscale were transformed linearly to a possible range of 0–100, with higher scores indicative of greater orientation toward integrative medicine. We calculated the mean, median, standard deviation, skewness of scale, and percentage of participants scoring the minimum (floor) and maximum (ceiling) for each item and scale. Internal consistency reliability was estimated for each subscale and for the 30-item scale using Cronbach's coefficient α (Cronbach 1951). For each subscale, we evaluated item discrimination (extent to which items correlate most with the scale they are designed to measure) by calculating the percentage of times that items in the subscale correlated significantly higher (at least two standard errors higher) with the hypothesized subscale (correcting for overlap) compared with other scales (Hays and Hyashi 1990). Analyses were conducted using SAS 8.0 (Cary, NC, USA) and STATA 8.0 (College Station, TX, USA).

To assess construct validity, we examined the associations of the IM-30 score with items assessing dual training, practice setting, practitioner type, and self-perceived “integrativeness.” We hypothesized that practitioners who had received formal training in at least two healing paradigms would score higher on the IM-30 than “single-trained” practitioners. These dual-trained practitioners include physician acupuncturists (e.g., Western medicine and traditional Chinese medicine) and CAM practitioners (e.g., chiropractic and traditional Chinese medicine). We also hypothesized that practitioners who work in an integrative medicine setting would score higher on the overall IM-30 scale than those who work in a solely conventional or CAM setting. Moreover, we hypothesized that chiropractors and acupuncturists would score higher on the IM-30 total scale than physicians because prior work has shown that they are more open and ready to refer to practitioners from other medical paradigms (Coulter 1991; Barnes 2003). Lastly, we hypothesized that practitioners who self-perceived a higher level of “integrativeness” would score higher on the IM-30 scale compared with practitioners who rated themselves as less integrative.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Surveys were completed by 202 of 294 (69 percent) participants: 56 were physician acupuncturists, 52 were physicians, 49 were chiropractors, and 45 were acupuncturists. The adjusted response rate was 75 percent if undeliverable questionnaires and providers who were no longer in practice were removed from the denominator. The mean age of the practitioners was 47 years. Two-thirds of the practitioners were men. Seventy percent were nonLatino white, 23 percent were Asian, and 4 percent were Latino. Twenty-nine percent of practitioners were dual trained and the others were trained in only one paradigm. Two-thirds worked in a private, nonintegrative setting, and 13 percent worked in an integrative medicine setting. Respondents and nonrespondents were comparable in terms of practitioner type and zip code, the only two variables available for nonrespondents. Overall, 2 percent of items were missing. The subscale with the greatest number of missing responses was the Awareness and openness subscale: eight respondents (4 percent) had missing responses. Since respondents were able to answer six items, on average, in 1 minute during the cognitive interviews, we estimated that respondents required about 5 minutes to complete the IM-30.

Descriptive Statistics and Reliability of the IM-30 and Subscales

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliability, and item discrimination rates of each of the subscales and the IM-30 scale. The mean score of the IM-30 scale was 64 and scores of the five subscales ranged from 43 (Learning from alternate paradigms) to 74 (Safety of integrative medicine). Standard deviations ranged from 17 (Patient-centered care) to 20 (Awareness and openness). Most of the subscales were negatively skewed. Floor effects were generally small. Ceiling effects were more common, with 11 percent of respondents having the highest possible score on “Patient-centered care.” All subscales had an internal consistency reliability of 0.70 or above. All but one subscale had item discrimination successes of 80 percent or above. The IM-30 scale had an internal consistency reliability of 0.90.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Internal Consistency Reliability, and Item Discrimination of Clinicians' Orientation toward Integrative Medicine Scale and Subscales

| Scale/Domain | No. of Items | Mean Score* | Median Score* | SD | Skewness of Scale† | % Scoring Minimum | % Scoring Maximum | Internal Consistency‡ | Item Discrimination§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness and openness to working with practitioners from other paradigms | 10 | 69 | 72 | 20 | −0.72 | 1 | 2 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Readiness to refer patients to other paradigms | 7 | 64 | 67 | 18 | −0.13 | 1 | 2 | 0.74 | 0.75 |

| Learning from alternate paradigms | 5 | 43 | 40 | 20 | 0.21 | 3 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.95 |

| Patient-centered care | 3 | 73 | 75 | 17 | −0.56 | 1 | 11 | 0.71 | 1.0 |

| Safety of integrative medicine | 5 | 74 | 80 | 19 | −0.98 | 1 | 4 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| Clinicians' orientation toward Integrative Medicine Scale (IM-30) | 30 | 64 | 66 | 14 | −0.66 | 1 | 1 | 0.90 | — |

Possible range 0–100, with higher scores indicative of greater orientation toward integrative medicine.

Unbounded.

Cronbach's coefficient α.

Mean percentage of times that items in the scale correlated at least two standard errors higher with its hypothesized scale compared with other scales, correcting for overlap.

Table 2 presents the correlations among the five subscales and the IM-30 scale. The strongest correlation between subscales was for “Awareness and openness” and “Safety of integrative medicine” (0.57); “Awareness and openness” also correlated strongly with “Readiness to refer” (0.52) and “Learning from alternate paradigms” (0.49). “Readiness to refer” also was strongly correlated with “Safety of integrative medicine” (0.43). The overall IM-30 scale correlated significantly with all five subscales: the strongest correlations were with “Awareness and openness” (0.91), “Readiness to refer” (0.71), “Safety of integrative medicine” (0.70), and “Learning from alternate paradigms” (0.65). The subscales mapped to the domains in our conceptual model as seen in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Correlations among Subscales of Clinicians' Orientation toward Integrative Medicine Scale

| Scale | Awareness and Openness to Working with Practitioners from Other Paradigms | Readiness to Refer Patients to Other Paradigms | Learning from Alternate Paradigm | Patient-Centered Care | Safety of Integrative Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness and openness to working with practitioners from other paradigms | — | ||||

| Readiness to refer patients to other paradigms | 0.52 | — | |||

| Learning from alternate paradigms | 0.49 | 0.27 | — | ||

| Patient-centered care | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.26 | — | |

| Safety of integrative medicine | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.10 | — |

| Clinicians' orientation toward Integrative Medicine Scale (IM-30) | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.70 |

Bold variables represents Pearson product–moment coefficient, p<.01.

Relationship of IM-30 with Demographic Characteristics and Hypothesized Constructs

Comparisons between the IM-30 and its subscales with demographic characteristics and hypothesized constructs are shown in Table 3. Age, gender, and ethnicity were not significantly associated with the IM-30. As hypothesized, dual-trained practitioners scored higher than single-trained practitioners on the IM-30 total scale (71 versus 62, p<.001). Practitioner's training was also significantly correlated with all subscales. Chiropractors and acupuncturists scored significantly higher on the IM-30 scale and its subscales than did primary care physicians. Practitioner's self-perceived “integrativeness” was significantly correlated (r=0.60, p<.001) with the IM-30 scale. Practitioners with the highest level of self-perceived integrativeness scored higher than practitioners in the middle level, who scored higher than those in the lowest level (72, 66, and 53, respectively, p<.001). Contrary to the hypothesis, a higher score on the IM-30 was not significantly associated with working in an integrative medicine setting.

Table 3.

Comparison of Clinicians' Orientation toward Integrative Medicine Scale and Subscales with Demographic Characteristics and Hypothesized Constructs

| IM-30 Score | Awareness and Openness | Readiness to Refer | Learning from Alternate Paradigms | Patient-Centered Care | Safety of Integrative Medicine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0–100) | (0–100) | (0–100) | (0–100) | (0–100) | (0–100) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| (continuous) | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.01 |

| <40 years | 62 | 64 | 66 | 37* | 74 | 69 |

| 40–60 years | 67 | 72 | 65 | 45 | 75 | 78 |

| >60 years | 59 | 63 | 58 | 44 | 71 | 66 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 64 | 68 | 62* | 42 | 75 | 73 |

| Female | 66 | 69 | 69 | 43 | 71 | 75 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 65 | 68 | 65 | 42 | 75 | 75 |

| Asian | 62 | 68 | 62 | 39 | 68 | 70 |

| Latino | 63 | 68 | 68 | 39 | 69 | 64 |

| Other | 66 | 60 | 56 | 63 | 82 | 81 |

| Nativity | ||||||

| U.S. born | 65 | 68 | 65 | 44 | 76*** | 75 |

| Foreign born | 63 | 71 | 62 | 39 | 67 | 71 |

| Type of practitioner | ||||||

| Physician acupuncturists | 71*** | 77*** | 68*** | 49*** | 82*** | 78*** |

| Physicians | 50 | 48 | 54 | 29 | 70 | 50 |

| Chiropractors | 69 | 76 | 66 | 46 | 76 | 87 |

| Acupuncturists | 69 | 74 | 70 | 48 | 65 | 81 |

| Practice setting | ||||||

| Integrative clinic | 67 | 74 | 68 | 45 | 75 | 73** |

| Nonintegrative (academic) | 57 | 58 | 61 | 36 | 71 | 62 |

| Nonintegrative (private) | 66 | 71 | 64 | 44 | 74 | 78 |

| Providers' training | ||||||

| Credential† | ||||||

| Dual-trained | 71*** | 77*** | 68* | 49** | 82*** | 79* |

| Single-trained | 62 | 65 | 63 | 40 | 70 | 72 |

| Main medical paradigm | ||||||

| Conventional | 50*** | 48*** | 53*** | 31*** | 72 | 51*** |

| CAM | 69 | 75 | 67 | 47 | 70 | 84 |

| Providers' attitude | ||||||

| Self-perceived integrativeness | ||||||

| (continuous) | 0.60*** | 0.57** | 0.39** | 0.33** | 0.20** | 0.53** |

| Lowest (0–4) | 53*** | 53*** | 55*** | 35*** | 69** | 60*** |

| Middle (5–7) | 66 | 71 | 67 | 43 | 73 | 76 |

| Highest (8–10) | 72 | 79 | 69 | 48 | 77 | 82 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Chiropractors are classified as dual-trained if they have dual credentials of D.C. and L.Ac.

DISCUSSION

The IM-30 is a brief self-administered survey instrument whose purpose is to provide a comprehensive measure of clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine. This is the first instrument to measure both conventional and CAM practitioners' orientation toward integrative medicine across its key dimensions. We estimate that it will require about 5 minutes to complete this survey based on the pilot study. Initial support for the reliability and validity of the IM-30 was provided in a field test with conventional and CAM health care practitioners. These findings provide support that the IM-30 successfully captures constructs integral to clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine. It is also important to emphasize that in contrast to existing measures of integrative medicine, the IM-30 captures additional dimensions of practitioner education, openness, and patient-centered care.

All subscales exceeded the 0.70 internal consistency reliability threshold of adequacy for group comparisons (Nunnally and Berstein 1994). Item discrimination across subscales was good, with all subscales except “Readiness to refer” having at least 80 percent of items correlating significantly better with their own scale than with any other subscale. Since “Readiness to refer” was consistently expressed as an important theme during the semi-structured interviews, we retained this subscale despite this scaling characteristic.

Tests of construct validity were mostly consistent with our a priori hypotheses regarding constructs related to a practitioner's orientation toward integrative medicine. As hypothesized, the IM-30 scale and its subscales correlated strongly with practitioners having dual-training in CAM and conventional medicine. The strong association of the IM-30 total scale and its subscales with practitioner type and self-perceived integrativeness provided further support for the construct validity of the instrument. Only our hypothesis regarding practice setting was not supported. The latter finding may be related to Southern California practitioners in private practice expressing more favorable than expected attitudes toward integrative medicine, or practitioners in integrative settings being focused more on CAM and less on integration (Baer 1998). These hypotheses should be investigated in future studies conducted in other regions of the country.

A limitation of this study pertains to the sampling frame. Participants represented a convenience sample recruited from a single geographic region, and thus do not comprise a representative sample. Although our response rate was good, response bias may have influenced the findings. It is possible that practitioners who completed the survey had a more favorable attitude toward integrative medicine than those who did not complete the survey. In addition, clinicians who are hostile toward integrative medicine may be reluctant to express their negative feelings. Hence, the IM-30 may overestimate their openness and readiness to refer patients to other paradigms. Future studies should examine the performance of the IM-30 among clinicians who may be very hostile toward integrative medicine. Psychometric assessment should be repeated on the 30-item instrument when it is administered on its own, not as part of the 56-item draft survey. Moreover, future studies should examine the performance of the IM-30 among naturopaths, massage therapists, and medical specialists because they may play a significant role in integrative medicine.

The lack of a consensus on the definition and the practice of integrative medicine at the provider level has hindered efforts to evaluate the effects of merging medical paradigms on patient care and outcome. The results from this study suggest that the IM-30 provides an adequate assessment of the key dimensions of clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine. This instrument may permit the rigorous evaluation of the impact of integration on health care processes and outcomes, such as cost-effectiveness, health-related quality of life, and patient satisfaction. For instance, this instrument may facilitate evaluation of health care outcomes of low back pain care delivered by physician acupuncturists with higher versus lower orientation toward integrative medicine. The development a reliable and valid instrument represents a necessary first step to evaluate the association between clinicians' orientation toward integrative medicine and health care outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin McNamee, L.Ac., D.C.; Eric Mumbauer, D.C.; Richard Niemtzow, M.D., Ph.D.; Christina Choi, L.Ac.; Rebecca Buckles; the Medical Acupuncture Research Foundation; and the California Society of Oriental Medical Association for their help in recruiting practitioners. We also thank Tony Kuo, M.D., and Adam Burke, Ph.D., L.Ac., for their helpful suggestions in survey revision. We acknowledge the technical assistance of Victor Gonzalez and James Chih.

Dr. Hsiao was an NRSA fellow under a training grant PE19001-09 from the Health Resources Services Administration, and a Specialty Training and Advanced Research (STAR) fellow in the UCLA Department of Medicine. Ron D. Hays, Ph.D., was supported by the UCLA/DREW Project Export, National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20-MD00148-01), and the UCLA Center for Health Improvement in Minority Elders/Resources for Minority Aging Research, National Institutes of Health, and National Institute of Aging (AG-02-004).

Footnotes

We do not have any financial interests or conflicts of interest associated with this research project.

References

- Baer H, Jen C, Tanassi LM. “The Drive for Professionalization in Acupuncture: A Preliminary View from the San Francisco Bay Area.”. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;46:533–7. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. “The Acupuncture Wars: The Professionalizing of American Acupuncture—A View from Massachusetts.”. Medical Anthropology. 2003;3:261–301. doi: 10.1080/01459740306772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman L, Adair EG. “The Use of Ethnographic Interviewing to Inform Questionnaire Construction.”. Health Education Quarterly. 1992;19:9–23. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell I, Pher C, Schwartz GE, Grant KL, Gaudet TW, Rychener D, Maites V, Weil A. “Integrative Medicine and Systemic Outcomes Research.”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:133–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H. Research Methods in Cultural Anthropology. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cherkin DD, Barlow R, Deyo RA, Battie M, Street J, Barlow W. “A comparison of Physical Therapy, Chiropractic Manipulation, and Provision of an Educational Booklet for the Treatment of Patients with Low Back Pain.”. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339:1021–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter I. “An Institutional Philosophy of Chiropractic.”. Chiropractic Journal of Australia. 1991;21:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L. “Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests.”. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Deyo R, Walsh NE, Martin DC, Schoenfeld LS, Ramamurthy S. “A Controlled Trial of Transcutaneous Nerve Stimulation (TENS) and Exercise for Chronic Low Back Pain.”. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;322:1627–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC. “Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990–1997.”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E. The Desktop Guide to Complementary and Alternative Medicine: An Evidence-Based Approach. London: Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fugh-Berman A. “Herb–Drug Interactions.”. Lancet. 2000;355:134–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn C, Milbrndt WE, Little AS, Mason KE. “Dry Needling of Muscle Motor Points for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trials with Long-Term Follow-Up.”. Spine. 1980;5:279–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R, Hyashi T. “Beyond Internal Consistency Reliability: Rationale and User's Guide for Multitrait Analysis Program on the Microcomputer.”. Behavior Research Methods, Instrument and Computers. 1990;22(2):167–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao A, Wong MD, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, Liu H, Andersen RM, Gifford AL, McCutchan A, Bozzette SA, Shapiro MF, Wenger NS, HCSUS Consortium “Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Substitution for Conventional Therapy by Persons with HIV.”. Journal of AIDS. 2003;33:157–65. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kailin D. “Overview: Evaluating Organizational Readiness.”. In: Faass N, editor. Integrating Complementary Medicine into Health Systems. Gaitherburg, MD: Aspen; 2001. pp. 44–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publication Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Long A, Mercer G, Hughes K. “Developing a Tool to Measure Holistic Practice: A Missing Dimension in Outcomes Measurement within Complementary Therapies.”. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2000;8:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootz R, Bielinski LL. “Issues, Barriers, and Solutions Regarding Integration of CAM and Conventional Health Care.”. Topics on Clinical Chiropractics. 2001;8(2):26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J, Berstein IH. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier K, Astin J, Haskell WL. “Current Trends in the Integration and Reimbursement of CAM by Managed Care Organizations and Insurance Providers: 1998 Update and Cohort Analysis.”. American Journal of Health and Promotion. 1999;14(2):125–33. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Meek P, Bell I. “Development and Validation of the IMAQ: Integrative Medicine Attitude Questionnaire.”. BMC Med Education. 2003;3(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Hays RD, Ware JE. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks J. Operational Issues in Incorporating Complementary and Alternative Therapies and Providers in Benefits Plans and Managed Care Organizations. Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Issues Impacting Coverage Decisions. Tucson, AZ: Sponsored by U.S. National Institute of Health Office of Alternative Medicine, U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, and Arizona Prevention Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks J. “Major Trends in the Integration of Complementary and Alternative Medicine.”. In: Faass N, editor. Integrating Complementary Medicine into Health Systems. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publications; 2001. pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Weil A. “The Significance of Integrative Medicine for the Future of Medical Education.”. American Journal of Medicine. 2000;108:441–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]