Abstract

Objective

To assess whether gaining prescription drug coverage produces cost offsets in Medicare spending on inpatient and physician services.

Data Source

Two-year panels constructed from 1995 to 2000 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, a dataset of Medicare claims and health care surveys from the Medicare population.

Study Design

We estimated a series of fixed-effects panel models to calculate adjusted changes in Medicare spending as drug coverage was acquired (Gainers) relative to the spending of beneficiaries who never had drug coverage (Nevers). Explanatory variables in the model include age, calendar year, income, and health status.

Principal Findings

Assessments of inpatient and physician services spending provided no evidence of overt selection behavior prior to the acquisition of drug coverage (i.e., there were no preswitch spikes in Medicare spending for Gainers). After enrollment, the medical spending of Gainers resembled those of beneficiaries who never had drug coverage. Overall, the multivariate models showed no systematic postenrollment changes in either inpatient or physician spending that could be attributed to the acquisition of drug coverage.

Conclusions

We found no consistent evidence that drug coverage either increases or reduces spending for hospital and physician services. This does not necessarily mean that drug therapy does not substitute for or complement other medical treatments, but rather that neither effect predominates across the Medicare population as a whole.

Keywords: Medicare, prescription drug coverage, physician expenditures, inpatient expenditures

Far-reaching changes in the Medicare program are expected with the passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (PL 108-172), not the least of which is planning for the expenditures of the approximately 8 million beneficiaries who lacked any drug benefits beforehand. This group is particularly intriguing as they are likely to see the most significant improvement in their access to medications: if lack of drug coverage posed a barrier to getting necessary medications then beneficiaries without any drug coverage should exhibit considerable increases in prescription drug use once enrolled in the Medicare benefit. For policy makers trying to anticipate the impact of giving drug benefits to people without prior coverage, there are many questions about health and quality of life, but two relate to costs: (1) how much will the new benefit directly impact drug spending and (2) how much will it indirectly affect other medical spending, such as hospitalization and physician visits? The first question is straightforward and has been the subject of some study, although estimates vary depending on the study population and the analytic method. The second question stems from a less studied but widely held view that providing drug coverage may create cost-offsets through savings in other health care expenditures. The clinical literature cites many examples where pharmacological interventions reduce emergency and acute care treatments, although it is unclear how these findings translate to an entire population with diverse medical conditions. Both issues are important for informing expectations about the Medicare drug program as projections predict that the majority of Medicare beneficiaries without drug coverage will participate (Shea, Stuart, and Briesacher 2003–2004). This study addresses the questions framed above through comparisons of before and after spending patterns of Medicare beneficiaries who pick up drug coverage (Gainers), relative to those who never had it (Nevers). The analysis used 6 years of data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey and modeling techniques suitable for studying insurance transitions. We treated gaining coverage as plausibly exogenous for the following reasons. Our study covered a period of large expansions in Medicare drug coverage, from 65 percent in 1995 to 77 percent in 1999 (Briesacher, Stuart, and Shea 2002). Previous studies have found most changes in private health plans are because of external circumstances of different plan offerings or new enrollment opportunities rather than pure consumer choice (Cunningham and Kohn 2000; Stuart, Shea, and Briesacher 2001; Rice et al. 2002). In addition, we tested the exogeneity assumption in this study by reestimating the models with only individuals least likely to select into drug coverage—those who gained employer-sponsored coverage.

We expected from prior research to find increases in medication use after gaining prescription coverage because of decreases in patients' out-of-pocket prices (Leibowitz, Manning, and Newhouse 1985; Gianfrancesco, Baines, and Richards 1994; Gluck 1999; Lillard, Rogowski, and Kington 1999; Pauly 2004). However, the literature was less clear about how medications influence spending for physician services and hospitalization. Economic theory specifies that the relationships depend on whether the medical services are complements or substitutes. The empirical research is quite meager on this topic, although it seems reasonable to believe physician services are a complement to medications since patients must visit physicians to get prescriptions. In contrast, hospitalizations may act as substitutes if outpatient medications prevent acute events, although this association is also largely untested in diverse patient cohorts like the Medicare population. Thus, we had a cautious expectation of an inverse relationship between inpatient costs and prescription drugs.

Our analytical approach addresses two important weaknesses in the literature on health insurance coverage and medical care utilization. The first is our use of longitudinal data. Most analyses use cross-sectional data, which cannot be used to assess changes in medical care need or deteriorations in health (Kasper, Giovanni, and Hoffman 2000). This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to isolate the impact of insurance on health care spending from other influences because of differences within and across individuals. If, instead, individuals are followed over time, the temporal path of medical expenditures can be identified prior to the decision to acquire insurance coverage. Our longitudinal analysis assessed this observable element of selection as well as used a fixed-effects framework to control for time invariant factors.

The second contribution of this study is a narrow focus on gaining drug coverage. Analyses of losing insurance may be less useful for understanding the impact of acquiring coverage if these behaviors are not inversely related (Burstin et al. 1998; Long, Marquis, and Rodgers 1998). For example, individuals who lose their coverage may attempt to maintain the levels of care established while insured, in contrast to people who gain coverage and must learn to use the health care system as insured people (Stuart and Coulson 1993). In a study of adults who gained Medicaid or private health insurance, Kasper, Giovanni, and Hoffman (2000) detected relatively high levels of access problems for Gainers even after becoming insured. Alternatively, research that combines the gaining and losing samples together as the “intermittently uninsured” may be masking the unique issues facing people when acquiring insurance (McWilliams et al. 2003).

The literature specific to drug coverage is growing but much of it suffers from the methodological issues described above (Stuart and Coulson 1993; Lillard, Rogowski, and Kington 1999; Atherly 2002). Studies with pre- and postenrollment data on expansions in Medicaid or state drug assistance programs offer mixed findings. A large decline in hospital spending followed an expansion in the drug formulary of the South Carolina Medicaid program for an under age 65 population (Kozma, Reeder, and Lingle 1990). Similarly, Lingle, Kirk, and Kelly (1987) detected lower inpatient expenditures after the implementation of New Jersey's pharmaceutical assistance program for adults aged 65 or older. In contrast, Gilman et al. (2003) examined changes in Medicare spending after Vermont implemented two prescription drug programs for the state's low income Medicare beneficiaries. Their study found no cost offsets to the Medicare program—in fact, inpatient spending increased between 25 and 45 percent in the first year and physician services increased 9–17 percent, although subsequent expenditures returned to preenrollment levels.

METHODS

Data Source

The dataset for this study is a set of 2-year panels constructed from the 1995 to 2000 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). The MCBS is a longitudinal panel survey of a representative national sample of the Medicare population conducted under the auspices of CMS. Begun in the fall of 1991, over 12,000 Medicare beneficiaries are sampled from Medicare enrollment files and surveyed three times a year with computer-assisted personal interviews. The MCBS links Medicare claims to survey-reported events to provide complete expenditure and source of payment data on all health care services, including prescription drugs. The interview also collects information on public and private forms of health insurance such as the beginning and end dates of coverage and whether coverage includes prescription drugs.

Sample Selection Criteria

Our sampling frame included all fee-for-service beneficiaries with Parts A and B coverage during years 1995–2000. This criterion excluded beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare HMOs because they have no itemized Medicare claims. We examined the health insurance information of each sampled individual over a period of 2 years and excluded persons for the following reasons: no enrollment dates or multiple gains into and out of drug coverage (n=1,601); lost drug coverage (n=1,439); or held it continuously (n=12,210). Our final sample consisted of two mutually exclusive groups: people who gained drug coverage (Gainers, n=1,488) during the observation period and people who had no evidence of drug coverage (Nevers, n=4,366).

We also identified a subsample of people who gained drug coverage near the end of the year (n=60). This group was necessary to address an MCBS data limitation of providing drug-spending levels at only the annual level while the duration of drug coverage spanned one to eight quarters. The calendar-end subsample had at least three quarters of drug spending without drug coverage in a calendar year followed by at least three quarters of drug spending with drug coverage in the following calendar year. Our subsample provides pilot evidence on the magnitude of changes in drug spending after gaining drug coverage. This information is necessary for establishing the mechanism by which drug coverage might influence medical care spending through increased use of medications.

Study Variables

We examined three dependent variables in the models: total prescription drug expenditures (out-of-pocket costs isolated for subanalysis), Medicare inpatient hospital expenditures, and Medicare physician expenditures. Prescription drug spending comes from the MCBS interview, includes only prescribed medications and is available as annual estimates. We assessed Medicare spending for inpatient hospital and physician expenditures directly from the Medicare claims records with the dates of service. Medicare inpatient spending covers hospitalization and emergency room visits. Medicare physician spending includes doctor visits, outpatient hospitalization, physical therapy, laboratory tests, durable medical equipment, and some outpatient mental health services. Claims estimates were summed for each month and then averaged over a quarter to smooth out the estimates.1 For the multivariate models, we also trimmed the quarterly expenditure data at 2 standard deviations above the mean (>$3,684 for inpatient and >$548 for physician) to address extreme outlier values.2

The principal independent variable was a set of 14 indicators representing the time order of medical spending relative to the quarter of drug coverage enrollment. First, we identified all beneficiaries acquiring drug coverage and isolated the quarter in which the change occurred. We then tracked quarterly Medicare spending as relative to the switch quarter, allowing us to observe up to seven quarters of prior spending (e.g., a person gaining in the last quarter of study observation) and seven quarters postspending (e.g., a person gaining in the first quarter of study observation). For example, an indicator of “+4” means the fourth quarter after gaining drug coverage, while “−4” means the fourth quarter before the gain. For the Nevers group, we assigned a random switching quarter to serve as their pre- and postpoint of reference. The other independent variables are: age (coded as a continuous variable and age squared), a set of dummy variables indicating the calendar year, and a health status index derived from the Diagnostic Cost Group Hierarchical Condition Category (DCG/HCC) risk adjuster. The DCG/HCC risk adjuster identifies the presence of up to 189 medical conditions in the diagnoses fields in Medicare claims records. The adjuster applies previously calibrated weights to create a single risk score (denoted as ybase) of the patient's expected Medicare expenditure. In our models, we normalize ybase by dividing each predicted value by the mean ybase in the main population-based sample. Thus, a person with mean predicted expenditure equal to the population average is scored 1.0. The use of predicted as opposed to actual health care expenditures isolates individuals' need for medical care (presumably exogenous) from their actual use of medical care (presumably jointly determined with their insurance choices).

Multivariate Model

We chose a fixed-effects panel estimator and difference-in-difference (DD) model to explore the dynamic aspects of individual behavior around gaining drug coverage. The fixed-effects estimator is well suited for our data structure, and its strengths include direct assessments of spending changes and explicit handling of individual-level heterogeneity.3 The unit of observation was the person-quarter. The specification of the model occurred in two steps. In the first step, we assessed the extent that observable selection exists between drug insurance and nondrug spending. The basic model can be summarized as:4

| (1) |

where Yit is quarterly Medicare expenditures for beneficiary i in quarter t; αi is the intercept for each individual; Zit indicates the time order of each quarter relative to enrollment date, ZitRi is an interaction term indicating quarterly observations from Gainers,5Xit represents a vector of time-varying beneficiary-level demographic characteristics; Hit is the annual HCC risk index measured as a ratio of predicted individual spending over predicted average spending; and Ct is a set of year dummy indicators.

The main coefficients of interest are the β2's, which express the difference in Medicare spending between Gainers and Nevers in each quarter relative to the reference quarter. These coefficients capture differences in spending conditioned on the model covariates, Z, X, H, C, and the fixed effects. We plotted these coefficients in graphs to provide a visual expression of the likelihood that the postgain effects are influenced by unmeasured factors in the preperiod (i.e., adverse selection). If significant differences are present in the pregain coefficients, then an additional step is needed to control for them. This approach is not a definitive test of selection but rather a guide on the magnitude of influence.

The second step is a traditional DD model that compares both the pre- and postspending of Gainers to the period-matched spending of the Nevers. This model is reasonable if any changes in spending over time would have been the same for both groups except for any induced spending attributable to drug coverage. Controlling for observable factors, our DD model holds that the difference between Gainers and Nevers in the postperiod constitutes the insurance effect and period-related factors, while the difference in the preperiod reflects only the period-related factors. Thus, any remainder between the two differences equals the insurance effect for Gainers. The model elements are same as for equation (1) except the Z variables have been replaced by a single indicator of postenrollment observations, and the main effect of being a Gainer has been added as R and specified below:

| (2) |

The coefficient of β3 is the test that changes in spending for Gainers are different from preenrollment levels and from those of Nevers. We used SAS and STATA statistical software to conduct all analyses. None of the estimates used the MCBS sampling probability weights.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the sample sizes and descriptive characteristics of the Gainer and Never samples from the 1995 through 2000 MCBS. The average duration of drug coverage for Gainers is 4.8 quarters and the types of sources are: 46.2 percent self-purchased, 37.3 percent employer-sponsored, 10.4 percent Medicaid, 13.3 percent other public programs, and 3.4 percent undetermined (note percentages are greater than 100 percent because of people enrolling into multiple plans). In general, the groups are similar with a few exceptions: Gainers are more likely to be disabled beneficiaries under age 65 than the Nevers (9.7 versus 2.3 percent, p<.05) and also less likely to be the oldest old (35.6 versus 43.8, p<.05). The Gainer sample more often lived in metropolitan areas compared with the Never sample (64.2 versus 58.3 percent, p<.05) and in the Middle Atlantic area of the country (16.6 versus 12.3 percent, p<.05). The Gainer group also generated a higher average HCC risk ratio than the Never group (0.94 versus 0.91, p<.05).

Table 1.

Sample Size and Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries in 2-year Study Panels, n=5,854

| Status of Drug Coverage during 2 Years | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size (Unweighted) | Gainers | Nevers |

| Total (n) | 1,488 | 4,366 |

| Panel y9596 | 282 | 960 |

| Panel y9697 | 269 | 951 |

| Panel y9798 | 308 | 900 |

| Panel y9899 | 311 | 839 |

| Panel y9900 | 318 | 716 |

| Type of gained drug coverage (%) | ||

| Self-purchased | 46.2% | NA |

| Employer-sponsored | 37.3 | |

| Medicaid | 10.4 | |

| Other public programs | 13.3 | |

| Undetermined | 3.4 | |

| Average duration of coverage (quarters) | 4.8 | 0 |

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) |

| Male | 617 (41.5) | 1,709 (39.1) |

| Female | 871 (58.5) | 2,657 (60.9) |

| Age | ||

| <65 | 145 (9.7*) | 100 (2.3) |

| 65–69 | 165 (11.1) | 430 (9.8) |

| 70–74 | 359 (24.1) | 1,004 (23.0) |

| 75–79 | 290 (19.5) | 921 (21.1) |

| 80+ | 529 (35.6*) | 1,911 (43.8) |

| Metropolitan status | ||

| Nonmetro area | 532 (35.8*) | 1,819 (41.7) |

| Metro area | 956 (64.2*) | 2,547 (58.3) |

| Detailed census region | ||

| New England | 59 (4.0) | 117 (2.7) |

| Middle Atlantic | 247 (16.6*) | 537 (12.3) |

| East North Central | 259 (17.4) | 897 (20.5) |

| West North Central | 119 (8.0*) | 587 (13.4) |

| East South Central | 102 (6.9) | 341 (7.8) |

| West South Central | 159 (10.7) | 471 (10.8) |

| Mountain | 82 (5.5) | 229 (5.2) |

| Pacific | 135 (9.1) | 285 (6.5) |

| South Atlantic | 326 (21.9) | 902 (20.7) |

| YBase index | ||

| Panel average | 0.94* | 0.91 |

p<.05.

Source: 1995–2000 MCBS.

MCBS, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey; NA, not applicable.

Tables 2 and 3 show the annual expenditures for prescription drugs, inpatient hospitalizations and physician services arrayed according to drug coverage status. Table 2 summarizes the medical spending levels for the entire sample as well as shows the proportion with any utilization. Here, the spending levels for prescription drugs matched a priori expectations for the two groups but expenditures for the other services varied in conformance: Gainers had higher drug expenditures than Nevers, but the average physician and inpatient spending is notably similar. On average, Gainers spent about 20 percent more on medications than Nevers ($711 versus $565, p<.05), but were equally likely to purchase any prescription drugs (86.9 versus 88.2 percent, NS). In comparison, average inpatient spending is about the same ($1,560 Gainers versus $1,527 Nevers, NS) as is physician spending ($1,006 Gainers versus $1,024 Nevers, NS).

Table 2.

Univariate Statistics on Annual Prescription Drug, Inpatient, and Physician Expenditures of Medicare Beneficiaries by Drug Coverage Status, n=5,854

| Status of Drug Coverage during 2 Years | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medical Expenditures | Gainers | Nevers |

| Prescription drug | ||

| Mean (SE) | $711 (26) | $565 (10) |

| Percent with expenditures | 86.9 | 88.2 |

| Mean among those with any expenditures (SE) | $818 (29) | $641 (10) |

| Inpatient | ||

| Mean (SE) | $1,560 (158) | $1,527 (84) |

| Percent with expenditures | 16.9 | 16.0 |

| Mean among those with any expenditures (SE) | $9,247 (773) | $9,549 (404) |

| Physician | ||

| Mean (SE) | $1,006 (38) | $1,024 (24) |

| Percent with expenditures | 89.9 | 92.0 |

| Mean among those with any expenditures (SE) | $1,119 (41) | $1,114 (25) |

Source: 1995–2000 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.

Table 3 provides preliminary information on changes in prescription drug use before and after a gain in coverage. The sample is limited to Gainers with year-end changes and Nevers with matched switching dates. Estimates for total drug spending are statistically the same for the Nevers and Gainers in the year before the switch ($664 Gainers versus $547 Nevers, NS), however, spending levels diverge significantly in the year after the switch ($1,101 Gainers versus $592 Nevers, p<.05). On average, Gainers spent almost 66 percent more on prescription drugs in the year following the acquisition of drug coverage, compared with the Never sample, which spent 8.3 percent more. Out-of-pocket spending dropped over 20 percent for Gainers compared with increasing 8.3 percent for Nevers, however this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Sample Size and Annual Prescription Drug Spending before and after Drug Coverage Switch for Medicare Beneficiaries with Calendar-End Changes in Drug Coverage

| Sample Size (unweighted) | Year before Switch | Year after Switch | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | |||

| Gainers | 60 | 60 | – |

| Nevers | 177 | 177 | – |

| Average total Rx spending (SE) | |||

| Gainers | $664 (125) | $1,101* (194) | +65.8% |

| Nevers | $547 (47) | $592 (51) | +8.3% |

| Average out-of-pocket Rx spending (SE) | |||

| Gainers | $650** (125) | $506 (77) | −22.1% |

| Nevers | $547 (47) | $592 (51) | +8.3% |

p<.05, test is Gainers versus Nevers in year after switch.

OOP not equal to total because of rounding of partial quarters to full quarters.

Source: 1995–2000 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.

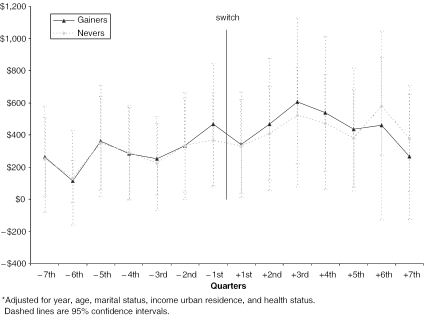

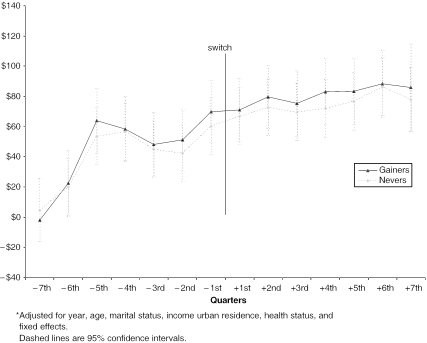

The next set of figures (Figure 1 and Figure 2) displays patterns in quarterly Medicare inpatient and physician spending by the Gainer group before and after the change in drug coverage, relative to the no coverage group. The estimates have been adjusted for calendar year, demographics, and health status (regression output for these graphs are available from the authors). For inpatient spending, we see similar increases during the entire period for both groups. Right before the acquisition of drug coverage by Gainers, we observe a slight gain in inpatient spending, although nothing of statistical significance (Figure 1). Following the switch, there appears to be no apparent sensitivity to the new coverage until after the 5th quarter—inpatient spending shows slight evidence of divergence as Gainers begin spending less than Nevers, although the difference is not statistically significant until the 7th quarter (p<.10). We see similar patterns for Medicare physician spending. In comparing the physician spending of the Gainer to the Never sample (Table 4), there is again no apparent change around the immediate period of gaining drug coverage. Here too, the Gainers show no statistically significant difference in Medicare spending from Nevers. Taken together, the adjusted patterns of inpatient spending and physician spending suggest no obvious relationship to drug coverage.

Figure 1.

Adjusted* Average Changes in Inpatient Spending before and after Drug Coverage Switch for Gainers versus Nevers

Figure 2.

Adjusted* Changes in Average Physician/Supplier Spending before and after Drug Coverage Switch for Gainers versus Nevers

Table 4.

Difference-in-Differences Model of Total Inpatient Spending for Gainers and Nevers

| Fixed-effects (within) Regression Group Variable (i): baseid R2: within=0.0036 between=0.0035 overall=0.0007 Corr(u_i,Xb)=-0.8453 |

Number of obs=13,680 Number of groups=1,401 Obsper group: min=8 avg=9.8 max=16 F(14, 12265)=3.19 Prob> F=0.0000 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Inpatient | Coefficent | SE. | t | p>∣t∣ | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

| y1996 | 187.791 | 54.95742 | 3.42 | 0.001 | 80.06581 | 295.5162 |

| y1997 | 197.1407 | 79.44047 | 2.48 | 0.013 | 41.42485 | 352.8565 |

| y1998 | 278.7367 | 103.0436 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 76.75515 | 480.7183 |

| y1999 | 384.1231 | 127.8534 | 3.00 | 0.003 | 133.5104 | 634.7359 |

| y2000 | 441.7032 | 150.1892 | 2.94 | 0.003 | 147.3087 | 736.0976 |

| Age | −336.8673 | 434.3684 | −0.78 | 0.438 | −1,188.298 | 514.5632 |

| Age2 | 1.850741 | 2.72236 | 0.68 | 0.497 | −3.485513 | 7.186995 |

| Married | 10.11199 | 241.6825 | 0.04 | 0.967 | −463.6238 | 483.8478 |

| Income | .1033875 | 1.45629 | 0.07 | 0.943 | −2.751171 | 2.957946 |

| Metro | −145.9165 | 716.1161 | −0.20 | 0.839 | −1,549.617 | 1,257.784 |

| HCC Index | 121.5006 | 35.7935 | 3.39 | 0.001 | 51.33974 | 191.6615 |

| Postperiod | 44.89839 | 37.38742 | 1.20 | 0.230 | −28.38683 | 118.1836 |

| Gain | −22.63968 | 135.5702 | −0.17 | 0.867 | −288.3786 | 243.0992 |

| Post × gain | −14.70328 | 63.81229 | −0.23 | 0.818 | −139.7854 | 110.3789 |

| _cons | 14,946.69 | 17,388.75 | 0.86 | 0.390 | −19,138 | 49,031.38 |

| sigma_u | 931.39804 | |||||

| sigma_e | 1,420.2969 | |||||

| rho | .30072056 (fraction of variance because of u_i) | |||||

The last two tables (Table 4 and 5) summarize the findings of the difference-in-difference models. Each estimate in this table shows the residual spending of persons gaining drug coverage in the postperiod relative to spending in the preperiod and by persons without any drug coverage. Number of groups refers to the unique persons with spending. Each person has a minimum of eight quarters of observations, creating a total of 45,384 person quarters. Observations differ across inpatient and physician models because people without spending changes contribute no observations to the models. The coefficients on “Post × Gain” indicate the test of Gainer spending after acquiring drug coverage relative to preacquisition spending and that of the Nevers. In the case of inpatient spending, the postcoverage differences are negative for Gainers versus Nevers and in the expected direction, although the estimates are not statistically significant. For physician spending, the annual postperiod differences are again negative for Gainers versus Nevers and not in the hypothesized direction, although the difference is not statistically significant. As a sensitivity test, we reestimated our models with only people gaining employer-sponsored coverage and found essentially the same results, although the standard errors were relatively large with the smaller sample.

DISCUSSION

We draw two conclusions from this study. First, our subsample analysis suggests that gaining prescription coverage may increase drug expenditures by as much as 66 percent in the first year following a year without prior coverage. The increase was expected, but the size of the estimated effect is among the largest found in prior research, where estimates ranged from 18 to 60 percent (Leibowitz, Manning, and Newhouse 1985; Gianfrancesco, Baines, and Richards 1994; Gluck 1999; Lillard, Rogowski, and Kington 1999; Pauly 2004). These results are based on a small, nonrandomly selected sample and offer only preliminary evidence of how much drug costs might rise for the large group of uninsured beneficiaries likely to take up the new Medicare drug plan. Additionally, it is clear that Medicare is offering a less generous plan than what beneficiaries have traditionally had through employers or the public sector. The difference in generosity would ameliorate the demand-inducing effect of coverage and thus limit additional spending. Our sample of people who gained drug benefits found, on average, over half of their medication expenses (54 percent) covered after gaining insurance coverage.

Second, the higher spending on drugs among those gaining coverage appears to have had little aggregate impact on spending for Medicare-covered services. This was a somewhat surprising finding given the higher spending that our total sample of Gainers incurred for medications relative to Nevers. During a period of increasing medication spending, we found physician spending remained relatively stable for Gainers, while their inpatient spending showed modest signs of dropping after about a year and a half, although these predictions are not statistically significant. Overall, we found no consistent evidence that gaining drug coverage reduces spending for hospital and physician services. These findings concur with those of the Congressional Budget Office and Gilman et al. in the Vermont drug plan evaluation (U.S. Congressional Budget Office 2002; Gilman et al. 2003).

The usual caveats apply to drawing causal inference from limited samples based on observational data. First, the distinction may be somewhat arbitrary between people who gain drug coverage and those who lose it or lack coverage for indeterminate periods. Insurance status is a highly fluid measure and people with unstable coverage are likely to experience multiple entries and exits (Short and Freedman 1998; Stuart, Shea, and Briesacher 2001). Our exclusion criteria mean that the study results cannot be generalized to the entire Medicare population, particularly those in managed care plans. It is possible that the longitudinal observation period was too short in duration to capture the clinical benefits of medications that influence use of hospitals and physicians. Many of the prescription drugs used by Medicare beneficiaries are taken over the course of many years to slow the effects of disabling disease and thus related changes on demand for medical services may share a similarly lagged effect. In an ad hoc analysis, we reestimated the DD model with postperiod defined as 1 year after gain. The Part B model coefficient changed from −2 to +2, p<.5. The Part A model coefficient changed from −14 to −58 but statistical significance was p<.3 as the standard errors were large. It is also important to note that the results reflect the marginal impact of drug benefits and not the full impact of drug therapy. Our results show high levels of medication use even among the uninsured, thus the impact of drug coverage refers to only the prescription spending above what the uninsured are spending.

On the technical side is the question of whether the analytic approach produces unbiased and precise estimates of treatment effects. The longitudinal approach attempted to assess the presence of observable selection into drug coverage, which is individuals changing their coverage status in response to anticipated changes in their expenditures. We observed no pregain patterns in Medicare spending that would indicate selection. Clearly, this finding is not definitive evidence of an exogenous relationship but it raises questions about the influence of expected hospital and physician spending on drug coverage decisions. Future research should more directly test these relationships. In the meantime, the longitudinal model of Gainers versus Nevers most closely approximates the changes that can be expected for the uninsured segment of the Medicare population once a Medicare drug benefit is implemented.

We believe the method described in this study offers a valuable approach for evaluating the impact of PL 108-172 on Medicare beneficiaries without prior drug coverage. Future research in this area should study a larger sample of Gainers for a longer period of time. Our analysis detected a tantalizing drop in inpatient spending about five quarters postgaining coverage, which needs further investigation with larger samples and longer observation periods. Future analyses should also take into account the generosity of coverage gained and the personal resources available to beneficiaries. Lastly, the impact of drug spending may be focused in particular disease areas, which should be explored in subsequent work.

Table 5.

Difference-in-Differences Model of Physician Spending for Gainers and Nevers

| Fixed-Effects (within) Regression Group Variable (i): baseid R2: within=0.0066 between=0.0242 overall=0.0098 Corr(u_i, Xb)=-0.3113 |

Number of obs=45,384 Number of groups=4,054 Obsper group: min=8 avg=11.0 max=16 F(14,41316)=19.68 Prob>F=0.0000 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Physician | Coefficent | SE | t | p>∣t∣ | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

| y1996 | 9.100585 | 3.430918 | 2.65 | 0.008 | 2.375913 | 15.82526 |

| y1997 | 14.25092 | 4.949754 | 2.88 | 0.004 | 4.549295 | 23.95254 |

| y1998 | 22.28622 | 6.533179 | 3.41 | 0.001 | 9.481051 | 35.09139 |

| y1999 | 29.73888 | 8.153666 | 3.65 | 0.000 | 13.75752 | 45.72024 |

| y2000 | 33.8768 | 9.628832 | 3.52 | 0.000 | 15.00408 | 52.74951 |

| Age | −20.6048 | 20.90089 | −0.99 | 0.324 | −61.57099 | 20.36139 |

| Age2 | .122362 | .1327581 | 0.92 | 0.357 | −.1378466 | .3825706 |

| Married | −17.61857 | 12.10421 | −1.46 | 0.146 | −41.34308 | 6.105949 |

| Income | −.0014219 | .0547972 | −0.03 | 0.979 | −.1088255 | .1059817 |

| Metro | −22.75821 | 37.74338 | −0.60 | 0.547 | −96.73604 | 51.21962 |

| HCC Index | 29.52116 | 3.312933 | 8.91 | 0.000 | 23.02774 | 36.01458 |

| Postperiod | 19.03616 | 2.345403 | 8.12 | 0.000 | 14.43912 | 23.6332 |

| Gain | .8919971 | 7.274963 | 0.12 | 0.902 | −13.36709 | 15.15108 |

| Post × Gain | −2.738953 | 4.122824 | −0.66 | 0.506 | −10.81978 | 5.341871 |

| _cons | 900.9817 | 827.3328 | 1.09 | 0.276 | −720.6082 | 2,522.572 |

| sigma_u | 94.073779 | |||||

| sigma_e | 168.21478 | |||||

| rho | .23824516 (fraction of variance because of u_i) | |||||

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under Contract number 500-00-0032 TO#4. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Dennis G. Shea, Department Head and Professor of Health Policy and Administration, Penn State, for his helpful comments.

Notes

We also assessed the model with monthly spending but found the estimates were volatile and the display prone to distracting “noise.”

We also estimated the model with logged and square-root transformations and found the model fit improved a few percentage points in some cases but the main findings remained the same. In the end, we used the trimmed raw values for ease of interpretation and presentation.

Limitations of the fixed-effects panel model include no estimates for time-invariant effects such as gender or race, and restricted generalizability. Strictly speaking, the fixed parameters of the individual-level intercept terms mean that common-level coefficients are conditional upon the members of the sample. We accepted this limitation rather than present the results from random effects panel models as the correlation between the individual-level errors and regressors was quite high, exceeding 0.84 in some cases. We also assessed the fixed-effects models for autocorrelated disturbances as it seemed likely that the pattern of spending (and residuals) in one quarter may be a fair indicator of spending in the next period. Our evaluation found that the autocorrelation never exceeded 0.10 in estimators with first-order correction for autoregression and the resulting changes in the coefficients and standard errors were quite modest.

We considered a 2-part model but in the end used a 1-part model to provide estimates of spending changes across the entire study population rather than just for users of services.

The Z variable is specified as 14 dummy variables arrayed as seven quarters pregain and seven quarters postgain. The quarter of enrollment is always equal to zero. The R variable is a group indicator=1 for Gainers and 0 for Nevers.

References

- Atherly A. “The Effect of Medicare Supplemental Insurance on Medicare Expenditures.”. International Journal of Health Care and Finance Economics. 2002;2(2):137–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1019978531869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briesacher B, Stuart B, Shea D. “Drug Coverage for Medicare Beneficiaries: Why Protection May Be in Jeopardy.”. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2002;(505):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstin HR, Swartz K, O'Neil AC, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. “The Effect of Change of Health Insurance on Access to Care.”. Inquiry. 1998;35(4):389–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PJ, Kohn L. “Health Plan Switching: Choice or Circumstance?”. Health Affairs. 2000;19(3):158–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfrancesco FD, Baines AP, Richards D. “Utilization Effects of Prescription Drug Benefits in an Aging Population.”. Health Care Financing Review. 1994;15(3):113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman B, Age B, Mitchell J, Haber S, Pope G. The Effect of Outpatient Prescription Drug Coverage on Medicare Expenditures. Waltham, MA: RTI International; 2003. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gluck ME. “A Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit.”. Medicare Brief: National Academy of Social Insurance. 1999;(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper JD, Giovannini TA, Hoffman C. “Gaining and Losing Health Insurance: Strengthening the Evidence for Effects on Access to Care and Health Outcomes.”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(3):298–318. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700302. (discussion 319–25) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma CM, Reeder CE, Lingle EW. “Expanding Medicaid Drug Formulary Coverage. Effects on Utilization of Related Services.”. Medical Care. 1990;28(10):963–77. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199010000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz A, Manning WG, Newhouse JP. “The Demand for Prescription Drugs as a Function of Cost-Sharing.”. Social Science and Medicine. 1985;21(10):1063–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Rogowski J, Kington R. “Insurance Coverage for Prescription Drugs: Effects on Use and Expenditures in the Medicare population.”. Medical Care. 1999;37(9):926–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingle EW, Jr., Kirk KW, Kelly WR. “The Impact of Outpatient Drug Benefits on the Use and Costs of Health Care Services for the Elderly.”. Inquiry. 1987;24(3):203–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SH, Marquis MS, Rodgers J. “Do People Shift Their Use of Health Services Over Time to Take Advantage of Insurance?”. Journal of Health Economics. 1998;17(1):105–15. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams JM, Zaslavsky AM, Meara E, Ayanian JZ. “Impact of Medicare Coverage on Basic Clinical Services for Previously Uninsured Adults.”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(6):757–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly MV. “Medicare Drug Coverage and Moral Hazard.”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004;23(1):113–22. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T, Snyder RE, Kominski G, Pourat N. “Who Switches from Medigap to Medicare HMOs?”. Health Services Research. 2002;37(2):273–90. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea DG, Stuart BC, Briesacher B. “Participation and Crowd-Out in a Medicare Drug Benefit: Simulation Estimates.”. Health Care Financing Review. 2003–2004;25(2):1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short PF, Freedman VA. “Single Women and the Dynamics of Medicaid.”. Health Services Research. 1998;33(5):1309–36. part 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart B, Coulson NE. “Dynamic Aspects of Prescription Drug Use in an Elderly Population.”. Health Services Research. 1993;28(2):237–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart B, Shea D, Briesacher B. “Dynamics in Drug Coverage of Medicare Beneficiaries: Finders, Losers, Switchers.”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2001;20(2):86–99. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congressional Budget Office . Issues in Designing a Prescription Drug Benefit for Medicare. Washington, DC: The Congress of the United States; 2002. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]