Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether fiduciary trust in a physician is related to unmet health care needs and delayed care among patients who have a regular physician, and to investigate whether the relationships between trust and unmet health care needs and delays in care are attenuated for disadvantaged patients who face structural obstacles to obtaining health care.

Data Sources/Study Setting

The 1998–1999 Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey, a cross-sectional sample representative of the U.S. noninstitutionalized population. This study analyzes adults who usually see the same physician for their health care (n=29,994).

Study Design

We estimated logistic regression models of the association of trust with unmet health care needs and delayed care. We tested interactions between trust and barriers to obtaining care, including minority race/ethnicity, poverty, and the absence of health insurance. Control variables included patients' sociodemographic characteristics, health status, satisfaction with the available choice of primary physicians, and the number of physician visits during the last year.

Principal Findings

Patients' fiduciary trust in a physician is negatively associated with the likelihood of reporting delayed care and unmet health care needs among most patients. Among African Americans, Hispanics, the poor, and the uninsured, however, fiduciary trust is not significantly associated with the likelihood of delayed care. For unmet needs, only the uninsured have no significant association with trust.

Conclusions

Results show that trust is associated with improved chances of getting needed care across most subgroups of the population, although this relationship varies by subpopulation.

Keywords: Unmet health care needs, delayed care, utilization of services, patient–physician trust, barriers to care

Unmet health care needs and delays in needed care are widespread problems in the United States. The Institute of Medicine (2002, p. 227) asserts that “much of the population fails to receive recommended preventive services, and many patients do not receive the full range of clinically indicated services for acute and chronic conditions.” Approximately 16 million Americans were unable to get needed medical care in 2001, and another 26 million people delayed getting the care they needed (Strunk and Cunningham 2002). Understanding the factors that contribute to unmet health care needs and delayed care is important as the failure to obtain health care in a timely fashion is associated with negative outcomes, including more costly care (Tidikis and Strasen 1994), delays in diagnosis or treatment and poorer health outcomes (Institute of Medicine 2002), and premature death (Kerlikowske et al. 1995). Previous research has established that health care access and utilization are affected by factors enabling individuals to obtain care (e.g., income, type of health care insurance and provider, etc.), factors representing the need for health care (e.g., type and seriousness of illness, health status, perceived symptoms, etc.), predisposing factors (e.g., preferences and styles of health care use and other nonhealth-related factors affecting demand for care), and major social stratification variables, including gender, age, education, race, and ethnicity (Blendon et al. 1989; Andersen and Newman 1993; Institute of Medicine 1993; King and Williams 1995; Ford, Bearman, and Moody 1999; Fiscella et al. 2000; Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2002; Agency for Health Research and Quality 2003). Worrying about cost is the most frequently cited barrier to getting needed care (Strunk and Cunningham 2002).

The patient–physician relationship could be an important factor in preventing unmet needs and delayed care among health care system users, but its role is poorly understood. In this study, we focus on one aspect of this relationship: a patient's fiduciary trust in his/her physician.1 Fiduciary trust in a physician captures the patient's belief that the physician will act in the patient's best interests and not take advantage of her or his vulnerability (Hall et al. 2001). Patients' trust in their physicians is associated with a number of health care outcomes, including better physician–patient communication; higher patient satisfaction (Thom et al. 1999); higher acceptance, compliance, and adherence to therapeutic regimens (Altice, Mostashari, and Friedland 2001); greater continuity of the physician–patient relationship (Safran et al. 1998; Thom et al. 1999; Mainous et al. 2001); lower patient disenrollment (Safran et al. 2001); and a higher likelihood that a patient will have his or her expectations met during the visit (Bell et al. 2002). Additionally, Safran et al. (1998) and Thom et al. (2002) linked patients' trust in their physicians to better health outcomes.

Health care system users with high fiduciary trust in a physician may be less likely to put off or completely forego visiting a doctor when a health problem arises than patients with low trust. In addition, they may be more likely to feel that the care they received met their needs. Timely and effective care may further increase their fiduciary trust in a feedback loop. This reasoning leads to the following hypothesis:

H1: A patient's fiduciary trust in her/his physician is negatively associated with delayed care and unmet health care needs.

There is limited research on patient–physician trust and other aspects of the patient–physician relationship among racial and ethnic minorities, low-income groups, and the uninsured (Pearson and Raeke 2000). Such patients face substantial structural obstacles to getting care, including practical and financial considerations and racial or ethnic discrimination (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2002). Furthermore, some disadvantaged health care users, especially members of racial and ethnic minority groups, may be vulnerable to lower trust in their physicians (Doescher et al. 2000; LaViest, Nickerson, and Bowie 2000; Boulware et al. 2003). Therefore, it is currently unclear how trust in a physician relates to unmet needs and delayed care among these health care system users who are vulnerable to health care underuse.

We believe that the link between fiduciary trust in a physician and reporting timely care is likely to be weaker or nonexistent in disadvantaged populations. Fiduciary trust may be more positively related to getting needed health care promptly among privileged patients who would easily be able to go to their doctors if they chose to do so. Among disadvantaged groups, discrimination in the health care system or practical considerations such as unavailability of child care, inability to take time off from work, lack of transportation, or unavailability or lack of choice of a health care provider, among other factors, may weaken the association between trust and getting needed care. For disadvantaged patients, worrying about how much they trust their physicians when making health care decisions may be a luxury that they, unlike more advantaged groups, cannot afford. Based on this line of reasoning, we propose three additional hypotheses concerning the relationship between trust and getting needed care in specific disadvantaged groups:

H2: Among black and Hispanic patients, iduciary trust in a physician has a weaker association with delayed care and unmet needs than among white patients.

H3: Among poor patients, fiduciary trust in a physician has a weaker association with delayed care and unmet needs than among higher-income patients.

H4: Among uninsured patients, fiduciary trust in a physician has a weaker association with delayed care and unmet needs than among privately insured patients.

METHODS

Sample

We use data from the 1998–1999 wave of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey (Center for Studying Health System Change 2001a). The data were collected from a representative sample of the U.S. noninstitutionalized population in 1998 and 1999. Stratified sampling with probabilities proportionate to the general U.S. population was used.2 A majority of households from 60 sampled communities were selected by random-digit dialing. Households without telephones were also represented. A total of 58,956 individual interviews were completed.

In the survey, questions about trust were asked of 40,558 adults comprising two conceptually distinct groups: (1) patients who had a regular physician, and (2) those who did not, but who saw a doctor at some point in the past year. Because trust in the physician–patient relationship is our main theoretical interest, we only include the former group of patients, who had a relationship with a regular physician. The criteria for inclusion in this group were based on three questions. First, respondents were asked, “Is there a place that you usually go to when you are sick or need advice about your health?” This question determined whether respondents had a regular source of care. Second, respondents who answered “yes” to the first question were asked, “When you go there, do you usually see a physician, a nurse, or some other type of health professional?” This question determined whether respondents saw a physician. Third, respondents needed to indicate that they usually see the same provider at each visit. All three restrictions are necessary because in the survey, only respondents with a regular source of care who also knew which type of provider they saw were asked about whether they usually see the same provider. Because of survey restrictions on questions about unmet health care needs and delayed care, our sample necessarily includes only respondents 18 years and older who completed the self-response module. After the listwise deletion of cases missing information on any of the variables used in multivariate analyses, we obtained a final sample of 29,994 respondents.3

Variables

Delayed Care and Unmet Health Care Needs

Delayed care is measured using the question, “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you didn't get the medical care you needed?” Unmet health care needs are measured using the question, “Was there any time during the past 12 months when you put off or postponed getting medical care you thought you needed?” Reponses to both these questions were coded as “yes”=1 and “no”=0. The same or similar survey items have been used previously to measure unmet health care needs (Newacheck et al. 1998, Newacheck et al. 2000), ability to obtain medical care (Berk, Schur, and Cantor 1995; Cunningham and Kemper 1998), and foregone care (Ford, Bearman, and Moody 1999). It is important to note that delayed care and unmet health care needs are independent concepts. It is possible to get care without delay but not to have one's medical needs met, if, for instance, the care is of poor quality. Similarly, it is possible to postpone care, yet eventually to receive care that meets one's health care needs.

Patients' Fiduciary Trust in a Physician

The measure of patients' fiduciary trust in a physician is an additive index of four items: (1) “I trust my doctor to put my medical needs above all other considerations when treating my medical problems,” (2) “I think my doctor is strongly influenced by insurance rules when making decisions about my medical care,” (3) “I think my doctor may not refer me to a specialist when needed,” and (4) “I sometimes think my doctor might perform unnecessary tests or procedures.” Respondents were instructed to think about the doctor they usually see when they are sick or need advice about their health. Response categories include “strongly agree,”“somewhat agree,”“neither agree/disagree,”“somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” Items (2)–(4) were reverse coded. The items were selected from an instrument authored by Paul Cleary (Center for Studying Health System Change 2001b) and are similar to items in other established scales measuring patient's trust in their physicians, including those developed by Anderson and Derrick (1990), Kao et al. (1998), and Thom et al. (1999). Positive and negative response items are combined to counter response bias problems.4 Exploratory factor analyses using principal components revealed that the four items constitute a single factor, with loadings >0.6. Reliability analysis of the unstandardized scale yielded a Cronbach's α of 0.6.

Barriers to Obtaining Care

Race/ethnicity, poverty, and access to health insurance identify the presence or absence of structural and demographic barriers to health care. Respondents’ self-reported race/ethnicity is coded by the CTS into four mutually exclusive categories: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and all other races. Poverty status is a dichotomous variable coded as 1 for those whose annual household income falls below the U.S. Census Bureau poverty level for their household size and 0 for others. We created a set of indicator variables to describe patients’ health insurance coverage. Private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid/other public insurance, military insurance, and no health insurance are mutually exclusive and coded 0 or 1.5

Control Variables

Respondents report their level of education in years. For confidentiality reasons, the CTS data set uses a bottom code for education at 6 years and a top code at 19 years.6 Annual household income is top coded at $150,000. Respondents' gender is included. Age in years is top coded at 91 years. Mental and physical health status measures are based on SF-12 Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores, calculated using the Health Institute's scoring algorithm.7 The physical health index ranges from 9.95 to 69.04, while the mental health index varies from 7.54 to 71.36.

For frequency-based utilization of care, we measure the frequency of visits. Respondents report the number of times they have been to the doctor in the 12 months preceding the time of interview. Responses are top coded at 20 visits in the CTS for reasons of confidentiality. Respondents' satisfaction with their available choice of primary physicians is based on the question: “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the choice you personally have for primary care doctors?” Response categories include “very satisfied”=5, “somewhat satisfied”=4, “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied”=3, “somewhat dissatisfied”=2, and “very dissatisfied”=1.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software (StataCorp 2001a) and weighted to represent the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the continental United States. After obtaining univariate and bivariate statistics, we estimated logistic regression models to evaluate the relationships between patients’ fiduciary trust in a physician and two dependent variables: unmet needs and delayed care. The models control for potential structural obstacles and other factors suggested by previous research to affect health care access, utilization, and perceptions of care, including patient sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and the context of care. We use robust estimators of variance (Huber 1967; White 1980, White 1982) that are suitable for weighted data (StataCorp 2001b). First, we examine the association between fiduciary trust and unmet needs and delayed care among all respondents in our sample. To clarify whether trust works differently among disadvantaged health care system users who face substantial structural obstacles to care, we next model unmet needs and delayed care among patients grouped by race/ethnicity, poverty level, and health insurance status.

RESULTS

Univariate Analyses

The results of univariate analyses, weighted to be nationally representative, are reported in Table 1. Of those respondents who have a regular physician, 21.7 percent reported delayed care, and 6.4 percent of respondents reported unmet needs. Delayed care and unmet needs have a strong positive relationship (p <.001; χ2 test).

Table 1.

Weighted Means, Confidence Intervals, and Ranges for Variables Used in the Analysis of Unmet Health Care Needs and Delayed Health Care Services

| Delayed Care | No Delayed Care | Unmet Needs | No Unmet Needs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.7%; N =6,502 | 78.3%; N =23,492 | 6.4%; N =1,913 | 93.6%; N =28,081 | |||||||

| Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Min | Max | |

| Fiduciary trust in physician | 15.85••• | (15.74; 15.97) | 17.01 | (16.96; 17.06) | 14.44••• | (14.19; 14.69) | 16.92 | (16.87; 16.97) | 4 | 20 |

| Health insurance type | ||||||||||

| Private insurance† | 0.66 | (0.64; 0.67) | 0.66 | (0.66; 0.67) | 0.58*** | (0.55; 0.61) | 0.67 | (0.66; 0.67) | 0 | 1 |

| Medicare recipient | 0.13*** | (0.12; 0.14) | 0.23 | (0.22; 0.23) | 0.12*** | (0.10; 0.14) | 0.21 | (0.21; 0.22) | 0 | 1 |

| Medicaid/public insurance | 0.06*** | (0.05; 0.06) | 0.04 | (003; 0.04) | 0.07*** | (0.06; 0.09) | 0.04 | (0.04; 0.04) | 0 | 1 |

| Military insurance | 0.01 | (0.01; 0.02) | 0.01 | (0.01; 0.01) | 0.02 | (0.01; 0.02) | 0.01 | (0.01; 0.01) | 0 | 1 |

| No health insurance | 0.14*** | (0.13; 0.15) | 0.06 | (0.06; 0.07) | 0.21*** | (0.18; 0.24) | 0.09 | (0.08; 0.09) | 0 | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.11 | (0.11; 0.12) | 0.11 | (0.10; 0.11) | 0.12 | (0.10; 0.13) | 0.11 | (0.10;0.11) | 0 | 1 |

| Non-Hispanic white† | 0.77 | (0.75; 0.78) | 0.78 | (0.77; 0.79) | 0.73*** | (0.71; 0.76) | 0.78 | (0.77;0.79) | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 0.08 | (0.07; 0.09) | 0.08 | (0.08; 0.09) | 0.11*** | (0.10; 0.13) | 0.08 | (0.08;0.08) | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0.04 | (0.03; 0.04) | 0.03 | (0.03; 0.04) | 0.04 | (0.03; 0.05) | 0.03 | (0.03;0.04) | 0 | 1 |

| Education (years)‡,§ | 13.19 | (13.11; 13.28) | 13.24 | (13.20; 13.28) | 13.07• | (12.92; 13.21) | 13.24 | (13.20; 13.28) | 6 | 19 |

| Household income ($10,000)‡ | 4.67••• | (4.57; 4.77) | 5.12 | (5.06; 5.17) | 4.36••• | (4.17; 4.55) | 5.07 | (5.02; 5.12) | 0 | 15 |

| Household income<poverty level | 0.12*** | (0.11; 0.13) | 0.09 | (0.09; 0.10) | 0.17*** | (0.15; 0.20) | 0.09 | (0.09; 0.10) | 0 | 1 |

| Delayed Care | No Delayed Care | Unmet Needs | No Unmet Needs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22.7%; N =7,685 | 77.3%; N =26,203 | 7.0%; N =2,360 | 93.0%; N =31,528 | |||||||

| Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Min | Max | |

| Female | 0.62*** | (0.60; 0.64) | 0.54 | (0.53; 0.55) | 0.62*** | (0.59; 0.65) | 0.56 | (0.55; 0.56) | 0 | 1 |

| Age (years)‡ | 42.64••• | (42.14; 43.14) | 47.49 | (47.21; 47.78) | 41.40••• | (40.61; 42.19) | 46.78 | (46.52; 47.04) | 18 | 91 |

| Physical health index | 45.84••• | (45.43; 46.25) | 49.16 | (48.99; 49.32) | 44.03••• | (43.31; 44.75) | 48.74 | (48.58; 48.90) | 9.95 | 69.04 |

| Mental health index | 48.69••• | (48.34; 49.04) | 53.66 | (53.52; 53.80) | 46.73••• | (46.07; 47.39) | 52.98 | (52.84; 53.11) | 7.54 | 71.91 |

| Satisfaction w/choice for phys. | 4.31••• | (4.28; 4.35) | 4.66 | (4.65; 4.68) | 3.98••• | (3.90; 4.05) | 4.63 | (4.62; 4.64) | 1 | 5 |

| Number of visits‡ | 4.88••• | (4.72; 5.04) | 4.03 | (3.96; 4.09) | 5.46••• | (5.15; 5.77) | 4.13 | (4.06; 4.19) | 0 | 20 |

| Delayed needed care | 0.73*** | (0.70; 0.75) | 0.18 | (0.18; 0.19) | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Unmet health care needs | 0.22*** | (0.20; 0.23) | 0.02 | (0.02; 0.03) | 0 | 1 | ||||

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998–1999 (N =29,994).

Reference category.

Top-coded variable.

Bottom-coded variable.

p <.05.

p <.001 (T-test for difference between weighted means compared with other category of variable; two-tailed test).

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001 (Pearson design-based F-test for independence compared with other category of variable; two-tailed test).

CI, confidence interval.

Bivariate Analyses

Table 1 also reports the results of bivariate analyses. As predicted, health care system users who report delayed care during the past year have significantly lower levels of fiduciary trust in their physicians (mean=15.85; p <.001) than those who did not report delayed care (mean=17.01). Similarly, respondents reporting unmet health care needs had lower trust levels (mean=14.44; p <.001) than those without unmet needs (mean=16.92). Bivariate analyses also provide some evidence that the hypothesized obstacles are indeed negatively related to obtaining timely care. There are significantly higher proportions of poor and uninsured among those reporting delayed care than among those not reporting delayed care. There are significantly higher proportions of Hispanic, poor, and uninsured patients among those who reported unmet health care needs than among those who did not (p <.001, for all cases).

Multivariate Analyses

Full Sample

Table 2 shows results of multivariate analyses for the full sample of patients who have a regular physician. Net of the effects of barriers to care, health status, characteristics of health care, and sociodemographic variables, trust in a physician has a substantial negative association both with delayed care and with unmet health care needs (p <.001, in all instances). A one-unit higher score on the 16-point fiduciary trust scale (approximately 0.3 standard deviations) is associated with 6 percent lower odds of reporting delayed care. The relationship between trust and unmet health care needs is even stronger. A one-unit higher score on the fiduciary trust scale is associated with 12 percent lower odds of having unmet needs. These findings support Hypothesis 1.

Table 2.

Estimates of Unstandardized Coefficients from Logistic Regression Models

| Independent Variable | Delayed Care | Unmet Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Health insurance type† | ||

| No health insurance | 0.70*** (0.56; 0.84) | 1.04*** (0.81; 1.27) |

| Medicaid/public insurance | −0.10 (−0.31; 0.11) | 0.14 (−0.17; 0.45) |

| Medicare recipient | −0.64*** (−0.79;−0.49) | −0.40** (−0.66;−0.14) |

| Military insurance | 0.10 (−0.27; 0.47) | 0.12 (−0.41; 0.66) |

| Race/ethnicity‡ | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | −0.17* (−0.29;−0.04) | −0.28**−0.49;−0.08) |

| Hispanic | −0.38*** (−0.53;−0.24) | −0.09 (−0.31; 0.13) |

| Other | −0.13 (−0.34; 0.08) | −0.27 (−0.63; 0.09) |

| Education (years) | 0.05*** (0.03; 0.06) | 0.07*** (0.04; 0.09) |

| Household income ($10,000) | −0.02*** (−0.03;−0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03; 0.01) |

| Household income<poverty level | −0.21** (−0.36;−0.05) | 0.05 (−0.19, 0.29) |

| Female | 0.27*** (0.19; 0.35) | 0.21*** (0.07; 0.34) |

| Age (years) | −0.01*** (−0.02;−0.01) | −0.02*** (−0.02;−0.01) |

| Physical health index | −0.04*** (−0.04;−0.04) | −0.04*** (−0.05;−0.03) |

| Mental health index | −0.04*** (−0.05;−0.04) | −0.04*** (−0.04; 0.03) |

| Satisfaction with phys. choice | −0.26*** (−0.31;−0.22) | −0.33*** (−0.39;−0.27) |

| Number of visits | 0.01* (0.00; 0.02) | 0.03*** (0.02; 0.04) |

| Fiduciary trust in physician | −0.06*** (−0.07;−0.04) | −0.13*** (−0.15;−0.11) |

| Intercept | 4.94 (4.51; 5.38) | 4.15 (3.53; 4.77) |

| % correctly predicted probability | ||

| DV=0 | 96.9 | 99.6 |

| DV=1 | 15.7 | 6.3 |

| Overall | 79.3 | 93.7 |

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998–1999 (N =29,994).

Notes:

Reference category is privately insured.

Reference category is white.

Weighted sample used.

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001 (two-tailed test).

95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

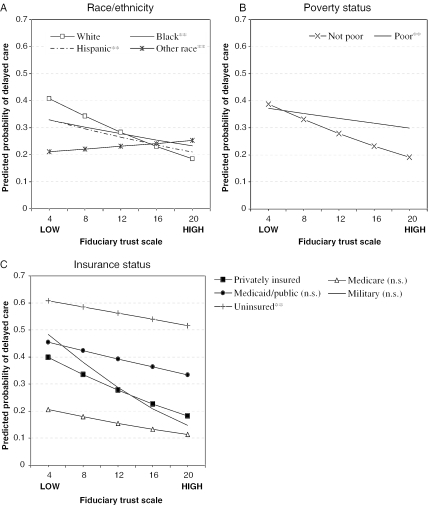

While some independent variables perform as previous research would predict and are not discussed here, others produce unexpected results not reflected in bivariate analyses. Medicare patients are significantly less likely to report delayed care (p <.001) and unmet needs (p <.01) than the privately insured. As anticipated, household income is negatively associated with delayed care (p <.001), but the relationship is not significant for unmet needs. Surprisingly, education is positively related to both delayed care and unmet needs (p <.001, in both instances). In addition, the odds of reporting delayed care are lower for non-Hispanic blacks (p <.05) and Hispanics (p <.001) than for whites when all control variables are included. The same negative relationship persists for unmet needs among non-Hispanic blacks (p <.01), but not among Hispanics. See below and Figure 1A for more information about the relationship between trust and race/ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probabilities of Delayed Care by Trust and Advantaged/Disadvantaged Subpopulations

Tests of significance for interactions between indicators of population groups and patients' fiduciary trust in a physician are reported, controlling for variables described in Table 1. Reference categories are (A) white, (B) not poor, and (C) privately insured. **p <.01 (two-tailed tests).

How important is the set of factors included in this analysis for predicting unmet needs and delayed care? We correctly predict outcomes for 96.9 percent of respondents who did not delay needed care, but for only 15.7 percent of those who did. The outcomes of 99.6 percent of respondents without unmet health care needs were correctly predicted, compared with only 6.3 percent of those with unmet needs.8

Disadvantaged Groups

The second set of multivariate analyses, reported in Figure 1, focuses on the relationship between fiduciary trust in a physician and health care outcomes for disadvantaged subpopulations (blacks, Hispanics, the poor, and the uninsured). We divide patients into subgroups on each variable to approximate their advantaged or disadvantaged status. Blacks, Hispanics, those whose household income falls below the U.S. Census Bureau poverty level for their household size, and the uninsured are considered to be disadvantaged as they are likely to face discrimination or other structural obstacles to getting care. We consider whites, those with household income at or above the federal poverty level, and the privately insured to be advantaged patients who do not face substantial obstacles to health care.9 There is a negative, statistically significant association between trust and unmet needs for all advantaged and disadvantaged subpopulations (p <.05, in all cases, results not shown), with the exception of the uninsured. The negative relationship between trust and delayed care, however, extends only to regular health care users who do not face structural obstacles to obtaining care. Fiduciary trust is not significantly associated with reporting delayed care among blacks, Hispanics, the uninsured, or the poor.

As another method of comparing the relationship between trust and health care outcomes across subpopulations, we introduce interactions between each group and trust into the models reported in Table 2.10 There are no significant differences in the strength of the positive relationship between fiduciary trust in a physician and eventually getting care between any advantaged and disadvantaged subgroup in the analysis of unmet needs, with the exception of the uninsured, who have a weaker association than others (p <.001; results not shown). As can be expected given the nonsignificant relationship between trust and delayed care in disadvantaged subpopulations, however, the negative association between trust and delayed care is significantly more modest among these groups than among their advantaged counterparts (see legend in Figure 1 for significance levels). Figure 1A graphically displays the predicted probabilities of delayed care at various levels of trust, based on analyses split by racial/ethnic category.11 There is very little racial/ethnic variation in the predicted probability of delayed care among respondents with high levels of trust, who constitute the majority of the sample (overall mean=16.76). However, the negative relationship between trust and delayed care is stronger among whites than among other groups (p <.01, in all instances), so whites with the lowest levels of trust have the highest predicted probability of delayed care at greater than 0.4.

Figure 1B displays the relationship between patients' fiduciary trust in a physician and the predicted probabilities of delayed care by poverty status. Poor respondents are more likely to delay care across all except the very lowest level of trust, and the negative association between trust and delayed care is dampened compared with others (p <.01). Figure 1C graphs the same relationship by insurance status and shows a similar pattern. While there are no significant differences in the slope of the relationship between trust and predicted probabilities of delayed care among the privately insured and military, Medicaid, and Medicare patients, uninsured respondents are much more likely to report delayed care across all levels of trust compared with the privately insured, and they have a dampened positive relationship between trust and delayed care (p <.01).12

Hypotheses 2–4 expect an attenuated relationship between trust and delayed care/unmet needs among disadvantaged respondents. The negative association between fiduciary trust in a physician and delays in care is not only diminished among disadvantaged health care users as hypothesized, but it is also not significant. In terms of unmet health care needs, these hypotheses are only supported among the uninsured.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Our research suggests that trust in patient–physician relationships is associated with meeting health care needs among patients who have a regular physician. Most patients who have a trusting relationship with their physicians are less likely than those with less trust to report having unmet health care needs. This relationship holds true for both advantaged and disadvantaged patients, with the exception of uninsured patients, for whom trust is not significantly associated with unmet needs. Fiduciary trust is negatively related to the likelihood of reporting delayed care among whites, the above-poverty population, and the privately insured. Trust is not, however, significantly related to delayed care among those who face structural obstacles to care, including blacks, Hispanics, the poor, and the uninsured.

Our findings on the associations between health care system users' race/ethnicity and getting prompt care are worth noting. It is known that minorities are underrepresented among people with a regular source of care (Weinick, Zuvekas, and Cohen 2000; Doescher et al. 2001). In our sample of patients who have a regular physician, however, there is no evident racial/ethnic disadvantage in getting prompt care. It seems plausible that minority patients who have a regular physician may not face the same disadvantages in obtaining prompt care as those who are less regular health care system users. Our findings imply that once blacks and Hispanics gain access to the health care system and become regular users, they are able to get prompt care when needed.

It is important to note the limitations of this research. Our study relies on cross-sectional data and thus does not speak on the directions of causality among fiduciary trust in a physician, barriers to care, unmet health care needs, and delayed care. The relationships between patients' trust in a physician and delayed care and between patients' trust in a physician and unmet health care needs may be reciprocal. Past experiences with physicians are likely to influence patients' trust, which then affects care-seeking behavior when medical needs arise. Similarly, past experiences with physicians and with health care may influence people's decisions to become insured and to continue insurance coverage. Experiences may also interact in complex ways with other factors influencing insurance status, including race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Further research, preferably using longitudinal data, is needed to provide a fuller assessment of the direction and strength of the causal paths in these reciprocal relationships.

What are the practical implications of these findings? Given our lack of knowledge about the relative importance of the causal directions between trust and health care use, our recommendations can only be preliminary and focus on one causal direction. Increasing patients' trust in a physician may be associated with improvement among patients in two important areas: getting care promptly and getting needed health care. Patient-centered physician communication is positively associated with patients' trust (Thom and Campbell 1997; Roberts and Aruguete 2000; Thom 2001; Keating et al. 2002). Therefore, training physicians in patient-centered communication might prove beneficial for raising trust levels among patients. Based on our findings, however, efforts to improve patients' trust in their physicians can only have limited results among disadvantaged patients in the absence of efforts to decrease racial/ethnic discrimination as well as more structural obstacles to obtaining care. A two-pronged approach, combining strategies to build patient trust with efforts to reduce practical and financial obstacles to obtaining care and discrimination in the health care system, may prove more effective. Further research on the causal effects of trust on health care access and utilization is needed, however, to support our recommendations.

Our study takes a detailed look at one dimension of patient–physician relationships, patients' fiduciary trust. Further research is needed to clarify whether other aspects of physician–patient relationships are linked to care seeking in similar or different ways. In particular, other dimensions and aspects of trust should be investigated. Along with fiduciary trust, theoretical research has identified confidentiality, competence, and honesty as dimensions of patient–provider trust (Hall et al. 2001).

Finally, the scope of our investigation is limited to consumers of medical care who have a regular physician. Our results are not generalizable to Americans who do not have a regular physician. In fact, levels of unmet health care needs are almost certainly higher among this group. Measuring fiduciary trust in a physician or other aspects of the patient–physician relationship, however, does not seem meaningful among people who do not have a regular physician. Systemic forms of trust not addressed in this paper, such as trust in the health care system and in doctors in general, on the other hand, may be substantially lower among the health care system nonusers than among the users, and may contribute to health care underuse. Trust in the system may motivate people to make use of the system by selecting a usual source of care and then seeking care at that source. Those who do not use the system may do so partially because of systemic mistrust, which may in some cases be generated by past negative experiences with health care providers and the quality of care received. Future longitudinal research should investigate the impact of various types of trust, including fiduciary trust, on adherence to medical treatment regimens, compliance, satisfaction, and health care outcomes more generally.

Increasing patients' trust in their physicians through training and the elimination of bureaucratic and other barriers to access may play a significant role in reducing failure to obtain health care when needed. Timely access to health care may in turn reduce delays in diagnosis and treatment, yielding higher quality health care outcomes and less costly care in the end.

Acknowledgments

The work reported here was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to Stefanie Mollborn and by The Dean of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Notes

It is important to distinguish patients' trust in a particular physician from trust in other objects, including physicians in general, the hospital, insurers, and health policy actors (Hall et al. 2001, 2002; Zheng et al. 2002; Gilson 2003; Kehoe and Ponting 2003).

Further information on the survey methodology is available in the CTS 1998–1999 User Guide (Center for Studying Health System Change 2001b).

Other than the trust variable for which the complicated selection process is described in the text, no variable is missing information from more than 326 eligible respondents. The data set contains imputed values for some variables. These imputations are discussed below.

Preliminary evidence suggests, however, that the items in this trust scale vary in their relationships to the respondent's sociodemographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (Stepanikova et al. unpublished manuscript).

Patients who were covered by Medicare in combination with other types of insurance have a value of 1 for the Medicare variable and 0 for the others.

Some imputed values for this variable were included in the data set. A flag for imputation was added to the multivariate analysis, and no significant negative association was found between having an imputed value for education level and either delayed care or unmet needs (p>.05, for all instances).

Some imputed values for these variables were included in the dataset. Flags for imputation were added to the multivariate analysis, and no significant effect for imputation was found.

These percentages were computed by cross-tabulating each respondent's actual outcome for the two dependent variables with the predicted outcome based on the logistic regression model, which was calculated by Stata.

We do not speculate on the level of advantage for respondents in the “other race” category or for military, Medicaid, and Medicare patients, but instead focus on the groups with the most clearly documented structural disadvantages in this analysis.

Multicollinearity among independent variables is not a serious problem in the interaction models once the trust variable has been centered (tolerances >0.48 in all models).

For the analyses reported in Figure 1, all other variables are set to their means if continuous and medians if categorical (education=13.73, income=57,811, female=1, age=47.27, physical health scale=48.96, mental health scale=52.96, physician choice satisfaction=4.62, number of visits=4.27; except for Figure 1A, white=1; except for Figure 1B, poverty=0; except for Figure 1C, privately insured=1).

While the finding is not significant (perhaps because of a larger standard error caused by only 318 patients having military insurance), it is interesting to note that unlike other insurance types, the association of trust with delayed care is greater among patients with military insurance than among the privately insured.

References

- Agency for Health Research and Quality 2003 http://www.qualitytools.ahrq.gov/disparitiesreport/download_report.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the Acceptance of and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2001;28:47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM, Newman JF. Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States. The Milbank Quarterly. 1993;51:95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the Trust in Physician Scale; A Measure to Assess Interpersonal Trust in Patient–Physician Relationships. Psychological Reports. 1990;67:1091–100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Thom D, Krupat E, Azari R. Unmet Expectations for Care and the Patient–Physician Relationship. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(11):817–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk ML, Schur CL, Cantor JC. Ability to Obtain Health Care; Recent Estimates from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation National Access to Care Survey. Health Affairs. 1995;14:139–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon RJ, Aiken LH, Freeman HE, Corey CR. Access to Medical Care for Black and White Americans. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261:278–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware EL, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and Trust in the Health Care System. Public Health Reports. 2003;118:359–65. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Studying Health System Change . Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998—1999 [Computer file]. ICPSR Version. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change [producer]; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Studying Health System Change . Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999: User Guide. ICPSR Version. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change [producer]; 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PJ, Kemper P. Ability to Obtain Medical Care for the Uninsured; How Much Does It Vary across Communities? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(10):921–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Saver BG, Fiscella K, Franks P. Racial/Ethnic Inequalities in Continuity and Site of Care; Location, Location, Location. Health Services Research. 2001;36(6, part II):78–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Perception of Physician Style and Trust. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:1156–63. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequalities in Racial Access to Health Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(16):2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CA, Bearman PS, Moody J. Foregone Health Care among Adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:2227–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L. Trust and the Development of Health Care as a Social Institution. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56(7):1453–68. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in Physicians and Medical Institutions; What Is It, Can It Be Measured, and Does It Matter? Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:613–39. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, Camacho F, Kidd KE, Mishra A, Balkrishnan R. Measuring Patients' Trust in Their Primary Care Providers. Medical Care Research and Review. 2002;59:293–318. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber PJ. The Behavior of Maximum Likelihood Estimates under Non-Standard Conditions. In: Le Cam LM, Neyman J, editors. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability Vol. 1. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services. In: Millman ML, editor. Access to Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kao AC, Green DC, Davis NA, Koplan JP, Cleary PD. Patients' Trust in their Physicians. Journal General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:681–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating NL, Green DC, Kao AC, Gazmararian JA, Wu VY, Cleary PD. How Are Patients' Specific Ambulatory Care Experiences Related to Trust, Satisfaction, and Considering Changing Physicians? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:20–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe SM, Ponting JR. Value Importance and Value Congruence as Determinants of Trust in Health Policy Actors. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(6):1065–75. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, Sandrock C, Ernster VL. Efficacy of Screening Mammography; A Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Williams DR. Race and Health; A Multidimensional Approach to African-American Health. In: Amick B, editor. Society and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- LaViest TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes and Racism, Medical Mistrust, and Satisfaction with Care among African American and White Cardiac Patients. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;75:146–61. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainous AG, III, Baker R, Love MM, Pererira Gray D, Gill JM. Continuity of Care and Trust in One's Physician; Evidence from Primary Care in the United States and the United Kingdom. Family Medicine. 2001;33(1):22–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung Y, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The Unmet Health Needs of America's Children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4, part 2):989–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, Stoddard JJ, Hughes DC, Pearl M. Health Insurance and Access to Primary Care for Children. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:513–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802193380806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson SD, Raeke LH. Patients' Trust in Physicians; Many Theories, Few Measures, and Little Data. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:509–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.11002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CA, Aruguete MS. Task and Socioemotional Behaviors of Physicians; A Test of Reciprocity and Social Interaction Theories in Analogue Physician-Patient Encounters. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50:309–15. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching Doctors; Predictors of Voluntary Disenrollment from a Primary Physician's Practice. Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50:130–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking Primary Care Performance to Outcomes of Care. Journal of Family Practice. 1998;47:213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Traeatment: Confronting Racal and Ethical Disparities Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata User's Guide: Release 7. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata 7.0 for UNIX. Statistics/Data Analysis. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanikova I, Bailey Mollborn S, Cook KS, Thom DH, Kramer RM. Patients' Race, Ethnicity, Language and Trust in Their Physicians. Unpublished manuscript. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk BC, Cunningham PJ. Treading Water; Americans' Access to Needed Medical Care, 1997-2001. Center for Health System Change Tracking Report Mar. 2002;(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom DH. Physician Behaviors That Predict Patient Trust. Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50(4):323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom DH, Campbell B. Patient-Physician Trust; An Exploratory Study. Journal of Family Practice. 1997;44:169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom DH, Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Krupat E, Azari R. Patient Trust in the Physician; Relation to Patient Requests and Request Fulfillment. Family Practice. 2002;19:476–83. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA. Further Validation of a Measure of Patients' Trust in Their Physician; The Trust in Physician Scale. Medical Care. 1999;37:510–7. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidikis F, Strasen L. Patient-Focused Care Units Improve Service and Financial Outcomes. Healthcare Financial Management. 1994;48:38–40, 42, 44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Access to and Use of Health Care Services, 1977-1996. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(1):36–54. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–30. [Google Scholar]

- White H. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Misspecified Models. Econometrica. 1982;50:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Hall MA, Dugan E, Kidd KE, Levine D. Development of a Scale to Measure Patients' Trust in Health Insurers. Health Services Research. 2002;37(1):185–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]