Abstract

We examined the immune response to DBY, a model H-Y minor histocompatibility antigen (mHA) in a male patient with chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant from a human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical female sibling. Patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells were screened for reactivity against a panel of 93 peptides representing the entire amino acid sequence of DBY. This epitope screen revealed a high frequency CD4+ T cell response to a single DBY peptide that persisted from 8 to 21 mo after transplant. A CD4+ T cell clone displaying the same reactivity was established from posttransplant patient cells and used to characterize the T cell epitope as a 19-mer peptide starting at position 30 in the DBY sequence and restricted by HLA-DRB1*1501. Remarkably, the corresponding X homologue peptide was also recognized by donor T cells. Moreover, the T cell clone responded equally to mature HLA-DRB1*1501 male and female dendritic cells, indicating that both DBY and DBX peptides were endogenously processed. After transplant, the patient also developed antibodies that were specific for recombinant DBY protein and did not react with DBX. This antibody response was mapped to two DBY peptides beginning at positions 118 and 536. Corresponding DBX peptides were not recognized. These studies provide the first demonstration of a coordinated B and T cell immune response to an H-Y antigen after allogeneic transplant. The specificity for recipient male cells was mediated by the B cell response and not by donor T cells. This dual DBX/DBY antigen is the first mHA to be identified in the context of chronic GVHD.

Keywords: minor histocompatibility antigen, chronic graft-versus-host disease, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, H-Y antigen, class II epitope

Introduction

Minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAs) are critical targets of immune responses after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT; 1). In patients who receive stem cell transplants from HLA-matched donors, mHAs are presumed to be the primary antigenic targets of GVHD (1). This immune response results in significant morbidity and mortality after allogeneic HSCT. However, mHAs are also expressed on recipient leukemia cells, and targeting these same antigens on tumor cells results in a graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect that reduces the incidence of relapse after transplant (2, 3). With the importance of these antigens as targets of both GVHD and GVL, their precise identification and characterization of the immune responses they elicit can have significant impact on the outcome of allogeneic HSCT.

mHAs have traditionally been identified as discrete peptides recognized by donor T cells after allogeneic HSCT. These peptides can be presented by either MHC class I or class II molecules and both CD8+ and CD4+ donor T cell responses have been described. Although alternative mechanisms for generating mHAs have recently been identified (4), most mHAs reflect genetic disparities between recipient and donor in regions outside of the MHC gene complex. For example, HA-1, HA-2, HA-3, and HA-8 are each encoded by autosomal genes with a coding single nucleotide polymorphism that distinguishes the recipient from the stem cell donor (5–8). Each single nucleotide polymorphism results in the generation of an immunogenic T cell antigen in recipient cells that is recognized by donor T cells after HSCT. In male patients with female donors, H-Y antigens constitute a distinct class of mHAs (9). In H-Y mHAs, the antigenic peptides are encoded by ubiquitously expressed male-specific genes located on the nonrecombining region of the Y chromosome. Although each of these genes has an expressed X homologue, each gene pair has significant disparity at the amino acid level (10–17). Thus far, all T cell H-Y epitopes that have been identified include disparate amino acid residues that appear to be essential for their immunogenicity. Upon transplantation into male patients, female donor T cells recognize these H-Y mHAs as “non-self” and elicit a strong immune response directed at recipient cells in vivo. Clinically, the relevance of H-Y antigens is evidenced by the increased risk of GVHD in male patients transplanted with female stem cells by comparison to other recipient/donor sex combinations (18).

In recent studies, our laboratory has demonstrated that H-Y mHAs also elicit a potent B cell response after allogeneic HSCT (19). Using DBY as a model H-Y mHA, we demonstrated that ∼50% of male patients who receive stem cells from female donors develop a high titer antibody response to recombinant DBY protein. Antibodies to DBY did not react with recombinant DBX homologue, were not present before transplant, and were rarely detected in male patients with male stem cell donors. Using a set of synthetic peptides encompassing the entire sequence of the DBY protein, the antibody response after transplant was primarily mapped to regions of amino acid disparity between DBY and DBX.

In this study, we undertook a comprehensive analysis of T and B cell immune responses elicited by DBY mHA in a male patient who developed chronic GVHD after transplantation with HLA-identical female donor stem cells. Using ELISPOT to detect specific T cell responses, unmanipulated patient T cells were screened for reactivity against a panel of 93 peptides representing the entire amino acid sequence of DBY. We subsequently isolated clonal CD4+ T cells in vitro that reacted with a single DBY peptide. In parallel, patient serum was also screened for antibodies specific for DBY. Here we demonstrate that DBY elicited a coordinated and sustained CD4+ helper T and B cell response. Both T and B cell epitopes were mapped to distinct regions of the DBY protein. Remarkably, the differential recognition of DBY compared with DBX was only observed at the B cell level, emphasizing the potential significance of the antibody component in the development of mHA-specific immune responses in chronic GVHD.

Materials and Methods

Patient Characteristics.

The patient studied in this report is a 44-yr-old male diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (M2 subtype) in December 2000. He responded to induction chemotherapy and achieved complete remission before undergoing allogeneic HSCT. In April 2001 he received a myeloablative preparative regimen consisting of 120 mg/kg cyclophosphamide and 1,400 cGy total body irradiation followed by infusion of G-CSF–mobilized blood stem cells from an HLA-identical female sibling. He remains in complete remission 2 yr after HSCT. His prophylactic immunosuppressive treatment included tacrolimus and methotrexate. 5 wk after transplantation, he developed acute GVHD of the skin (grade 2 GVHD). Acute GVHD responded to treatment with prednisone, daclizumab, and mycophenolate mofetil but did not resolve completely. He was subsequently treated for limited chronic GVHD with involvement of skin and oral mucosa with a combination of mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone. Chronic GVHD persists 2 yr after transplantation and the patient remains on immunosuppressive drugs.

Peptides.

Synthetic peptides were obtained from New England Peptide. Peptides were either unpurified (93 screening peptides), or >85% purity (DBX34–47, DBY34–47, DBX30–48, DBY30–48, DBX120–136, DBY118–134, DBX538–554, DBY536–552). Each peptide was reconstituted at 10 mg/ml DMSO and stored at −20°C.

Cell Culture.

Patient and allogeneic EBV-transformed B cell lines were generated by incubating PBMCs with supernatant from EBV–producing B95-8 marmoset cells. Once established, cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 4 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes, and antibiotics. T cell lines and clones were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum, glutamine, sodium pyruvate, Hepes, and antibiotics (referred to as T cell medium) in the presence of 100 U/ml recombinant IL-2. Medium was replenished twice weekly with fresh IL-2. Immature DCs were obtained as previously described (20). In brief, 40–60 × 106 PBMCs were incubated for 15 min in a 75-cm2 Costar culture flask (Corning Inc.). Nonadherent cells were removed by thoroughly washing the flask three times with medium. The remaining adherent cells were incubated for 1 wk in medium supplemented with 1,000 U/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems) and 1,000 U/ml GM-CSF (R&D Systems). Cells were then harvested, washed, and used as immature DCs. Maturation of DCs was achieved by incubating cells for 24 h with 25 ng/ml poly-IC (Amersham Biosciences) or 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich).

Generation of a DBY-reactive T Cell Clone.

A T cell line was generated by stimulating 6 × 106 PBMCs collected from the patient 16 mo after HSCT in the presence of peptide DBY34–50 at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml in the presence of 100 U/ml IL-2. 1 wk after stimulation, CD4+ T cells were immunopurified from the cell line using anti-CD4+ microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and subsequently cloned by limiting dilution on feeder cells consisting of irradiated patient EBV B cells (1.5 × 104 cells/well; 60 Gy) and allogeneic PBMCs (7 × 104 cells/well; 35 Gy) in the presence of 100 U/ml recombinant human IL-2. All of the T cell clones generated were assessed for specific reactivity with the DBY peptide. Clone 2F9 displayed strong reactivity and was further expanded under the same culture conditions with the addition of PHA (Invitrogen).

ELISPOT Assays.

ELISPOT assays were performed as previously described (21). In brief, 1–2 × 105 PBMCs were incubated in duplicate cultures in the presence of 10 μg/ml different peptides in multiscreen-IP microplates (Millipore) previously coated with anti–IFN-γ mAb (Mabtech). After an overnight incubation, plates were washed six times in PBS and incubated with a biotinylated anti–IFN-γ mAb (Mabtech) at room temperature for 75 min. The plates were washed again and incubated with streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (Mabtech) for 45 min at room temperature. The plates were finally washed and spots were revealed using nitroblue tetrazolium and brom-chlor-indolyl phosphate color development substrates (Promega). Spots were counted in duplicate wells and results were presented as number of spot forming cells/106 PBMCs.

IFN-γ Secretion Assays.

IFN-γ secretion by T cell clone 2F9 was assessed by incubating 5 × 104 responder cells in 96-well, U-bottom microplates with 5 × 104 stimulator cells in 200 μl T cell medium containing 50 U/ml IL-2. Stimulator cells consisted of autologous or allogeneic EBV B cells pulsed with synthetic peptides (10 μg/ml or as otherwise stated) for 1 h at 37°C and washed twice to remove excess peptide. After 18 h of incubation, 50 μl/well supernatant was harvested and IFN-γ was measured using an ELISA kit (Endogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In experiments with DCs, 10,000 immature DCs/well were incubated in 100 μl medium with or without LPS or poly-IC for 24 h at 37°C. 4 × 104 2F9 cells were then added to the culture in the presence of 50 U/ml IL-2, and secretion of IFN-γ was measured after 18 h of incubation.

Cytotoxicity Assay.

Target cells were labeled with 51Cr for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times, pulsed with the corresponding peptide for an additional hour at 37°C, washed three times again, and then plated at 2,000 cells/well in conical-bottom, 96-well microplates. Clonal 2F9 cells were added at varying effector/target ratios and 51Cr release was measured in the supernatant after 4 h of incubation at 37°C. In cold target inhibition experiments, HLA-DR*1501 female or male unlabeled matured DCs were incubated with 51Cr-labeled targets at various ratios for 1 h before adding the T cell clone.

Recombinant Protein Production and Western Blot Assays.

Recombinant DBX and DBY protein production and purification has been described (19). In brief, full-length DBX and DBY cDNA were cloned using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen) into pDEST42 prokaryotic expression vector introducing V5 and 6 HIS Tag epitopes at the protein C terminus. After transformation in Escherichia coli, DBX and DBY expression was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and proteins were purified from bacterial lysates by affinity chromatography on nickel columns (Invitrogen). For Western blotting, 5 μg of each protein was run by electrophoresis on a 4–12% polyacrylamide gel in denaturing conditions using the NuPAGE system (Invitrogen), transferred on a nitrocellulose membrane, and blocked for 1 h in blocking buffer (1X TBST, 5% nonfat dry milk). Membranes were incubated overnight with either horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-V5 epitope mAb (Invitrogen) or patient serum diluted at 1:10 in blocking buffer, and then with HRP-conjugated goat anti–human IgG antisera (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Proteins were subsequently detected using the “Western Lightning” chemiluminescence HRP reagents (PerkinElmer).

DBY ELISA Assays.

Antibodies to DBX and DBY recombinant protein, as well as DBX and DBY peptides, were measured by ELISA (19). In brief, high protein adherence Nunc-Immunoplates (Nunc) were coated overnight with either 5 μg/ml purified recombinant protein or 10 μg/ml synthetic peptides in carbonate-binding buffer, washed in TBST, and then blocked with 2% nonfat dry milk in TBST. Serum diluted in blocking buffer was then added to the plates and incubated either overnight at 4°C for the recombinant protein–coated plates, or for 3 h at 20°C for the peptide-coated plates. Plates were then washed in TBST, incubated for 1 h at 20°C with alkaline phosphatase–conjugated goat anti–human IgG antisera (Pierce Chemical Co.), diluted in blocking buffer, washed again, and developed using pNPP alkaline phosphatase substrate colorimetric reagents (Sigma-Aldrich). Optical density was read at 405 nm.

Results

DBY mHA Elicits a Sustained T Cell Response after HSCT.

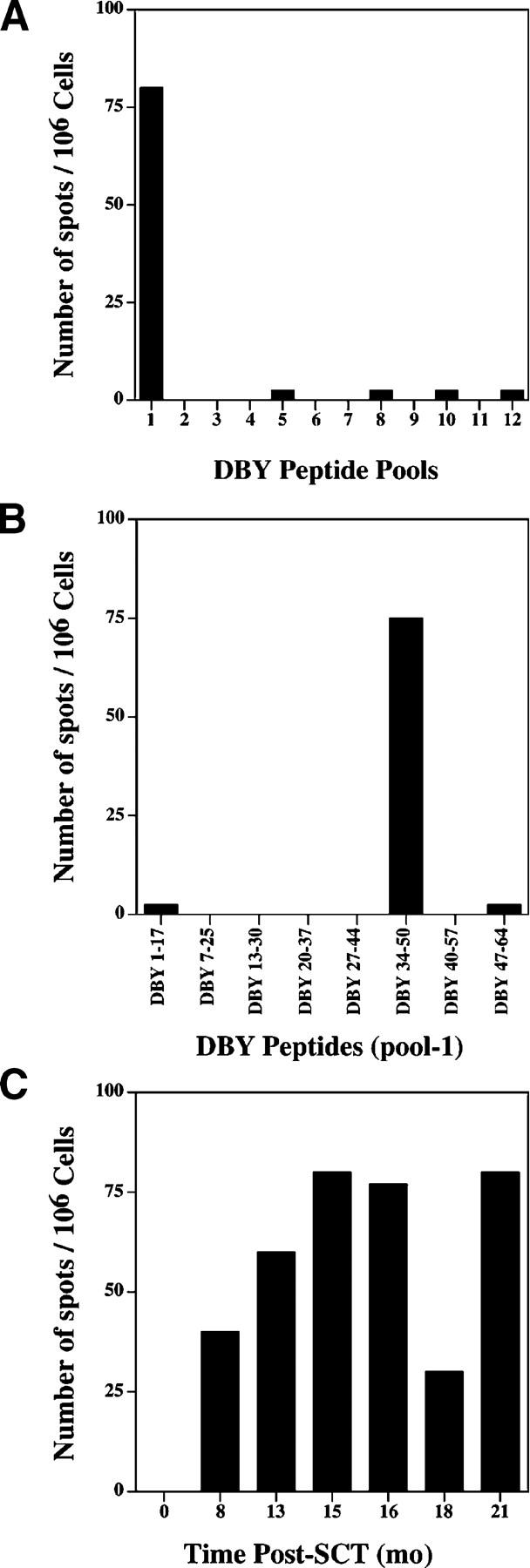

Initial experiments were designed to assess T cell reactivity to a prototypic H-Y antigen, DBY. 93 overlapping peptides representing the entire amino acid sequence of DBY were synthesized and distributed in 12 pools of either 8 or 5 peptides. PBMCs collected from a male patient 15 mo after receiving allogeneic stem cells from a female donor were tested for reactivity to each peptide pool using an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. To avoid skewing the representation of potential DBY-reactive cells, ELISPOT assays were performed using unmanipulated PBMCs without in vitro sensitization or expansion. As shown in Fig. 1 A, patient PBMCs were highly reactive with DBY peptide pool 1 and no T cell reactivity against any of the other 11 peptide pools was present. Further testing of individual peptides in pool 1 demonstrated that this reactivity was specific for a single peptide, DBY34–50 (Fig. 1 B). These results demonstrated the presence of a vigorous anti-DBY T cell response in vivo 15 mo after transplant that targeted a single peptide epitope. Although these experiments do not exclude the possibility that T cells specific for other DBY peptides were present at lower frequency, DBY34–50 was the only DBY peptide that was recognized by unstimulated PBMCs. The high level T cell reactivity against this peptide was confirmed by testing unstimulated PBMCs collected at various times before and after HSCT. As shown in Fig. 1 C, no reactivity was detected by ELISPOT before transplant but persistent T cell reactivity was present in all PBMC samples available for testing between 8 and 21 mo after transplant.

Figure 1.

DBY elicits a sustained T cell response after allogeneic HSCT. (A) IFN-γ secretion ELISPOT assay was performed using unstimulated PBMCs collected 15 mo after HSCT and 93 overlapping DBY peptides distributed into 12 pools. Results are presented as number of spot-forming cells/106 PBMCs. (B) The eight peptides included in pool-1 were tested individually using the same cells and according to the same procedure. (C) Patient PBMCs collected at various times before and after HSCT were tested by ELISPOT assay for reactivity to the DBY antigenic peptide. Time 0 corresponds to a sample collected before HSCT.

The DBY Peptide-specific CD4+ T Cell Response Is Restricted By HLA-DRB1*1501.

ELISPOT experiments using PBMCs depleted of either CD4+ or CD8+ T cell subsets revealed that DBY peptide–reactive cells were only present in the CD4+ T cell population. PBMCs collected 16 mo after HSCT were stimulated once with peptide DBY34–50 in the presence of IL-2. After 1 wk of stimulation, CD4+ T cells were purified and cloned by limiting dilution. Several CD3+ CD4+ T cell clones were obtained that reacted with donor EBV-immortalized B (EBV B) cells pulsed with DBY34–50. One clone, 2F9, was expanded in vitro for further studies. TCR Vβ repertoire analysis was performed using RNA extracted from 2F9 cells and showed the expression of a single rearranged TCR β chain derived from the RBV12.151 segment. DNA sequencing confirmed the presence of a single TCR Vβ rearrangement.

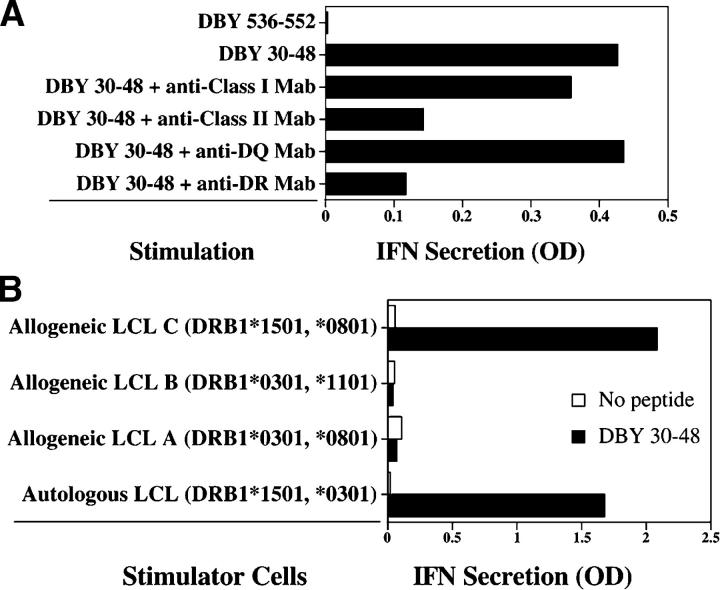

The optimal DBY antigenic epitope was characterized by testing the reactivity of clone 2F9 to synthetic peptides of different lengths in dose response experiments. Starting with the putative epitope DBY34–50, we tested peptide variants with longer or shorter N and C terminus for their ability to stimulate clone 2F9. The highest reactivity was obtained using the 19-mer peptide DBY30–48. As shown in Fig. 2 A, stimulation of clone 2F9 with EBV B cells pulsed with DBY30–48 was inhibited by anti–HLA class II and anti–HLA-DR mAbs, but not by anti–HLA class I or anti–HLA-DQ antibodies. These results indicated that TCR recognition was restricted by HLA-DR. To determine which HLA-DR allele was recognized by the 2F9 clone, we used a series of allogeneic EBV B cells expressing either HLA-DRB1*0301 or HLA-DRB1*1501, the HLA-DR alleles expressed by both patient and donor. As shown in Fig. 2 B, cells expressing DRB1*1501 stimulated clone 2F9 when pulsed with the DBY peptide, whereas cells expressing DRB1*0301 were not recognized. These experiments indicate that the DBY30–48 peptide was specifically presented by HLA-DRB1*1501.

Figure 2.

The CD4+ T cell response to DBY antigen is restricted by HLA-DRB1*1501 molecules. (A) CD4+ T cell clone, 2F9, was stimulated with autologous EBV-immortalized B cells pulsed with DBY peptide (DBY30–48) or another irrelevant DBY peptide. Anti–HLA class II mAb (9.49) and anti–HLA-DR mAb (G46.6) blocked antigen recognition, whereas anti–HLA class I (W6/32) or anti–HLA-DQ (SPVL.3) mAb did not. Results represent quantitative measurement of IFN-γ secretion in the coculture supernatant obtained by ELISA. (B) Clone 2F9 was stimulated with different DBY30–48–pulsed EBV B cells (LCL) sharing the expression of either HLA-DRB1*0301 or HLA-DB1*1501 with the patient cells. After overnight incubation, IFN-γ secretion was measured in the coculture supernatant.

The T Cell Response Recognizes both DBX and DBY Antigenic Peptides.

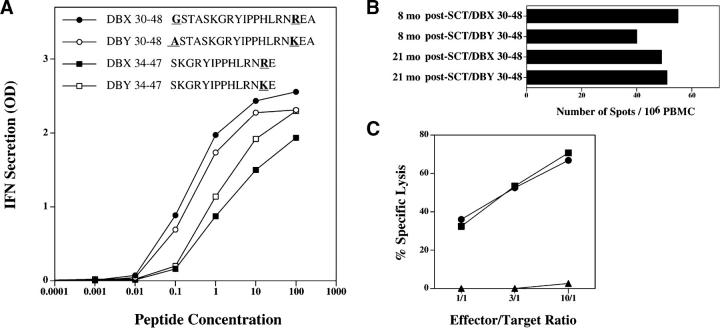

We then tested whether clone 2F9 would also recognize the corresponding X-encoded peptide, DBX30–48, which differs from DBY30–48 by two residues at positions 30 and 46. Despite the two disparate amino acids, both X and Y peptides stimulated clone 2F9 at a similar level (Fig. 3 A). A shorter peptide starting at residue 34, which only included disparate position 46, was also tested. Although less reactive than the longer peptide, the X and Y alleles of the shorter peptide were equally recognized by clone 2F9 (Fig. 3 A). To confirm that clone 2F9 was representative of the T cell response that developed in vivo, we examined the reactivity of unmanipulated patient cells to both DBX and DBY peptides. As shown in Fig. 3 B, equivalent reactivity against the two peptides was detected in ELISPOT assays using unmanipulated PBMCs collected at 8 and 21 mo after HSCT, indicating that the T cell response in vivo also recognized both epitopes. T cell clone 2F9 also displayed substantial cytolytic activity toward patient EBV B cells pulsed with either DBY30–48 or DBX30–48 but not an irrelevant peptide, DBY536–552 (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

DBX and DBY epitopes are both recognized by patient T cells. (A) 2F9 T cells were stimulated with autologous EBV B cells pulsed with different concentrations of DBX and DBY peptides. IFN-γ secretion was measured in the coculture supernatant after overnight incubation. The optimal 19-mer DBX and DBY peptides are shown in • and ○, respectively. Shorter, 14-mer suboptimal epitopes are also shown (▪ and □). Disparate residues between DBX and DBY versions of the peptides are represented with bold underlined characters. Peptide concentrations are expressed in microgram/milliliter. (B) IFN-γ secretion ELISPOT assays were performed using unstimulated PBMCs collected 8 and 21 mo after HSCT and both DBX30–48 and DBY30–48 peptides. (C) Clone 2F9 cytolytic activity was tested against EBV B cells pulsed with either DBX30–48 (▪), DBY30–48 (•), or an irrelevant peptide, DBY536–552 (▴).

T Cell Clone 2F9 Recognizes Endogenously Processed DBX and DBY Antigens in Mature DCs.

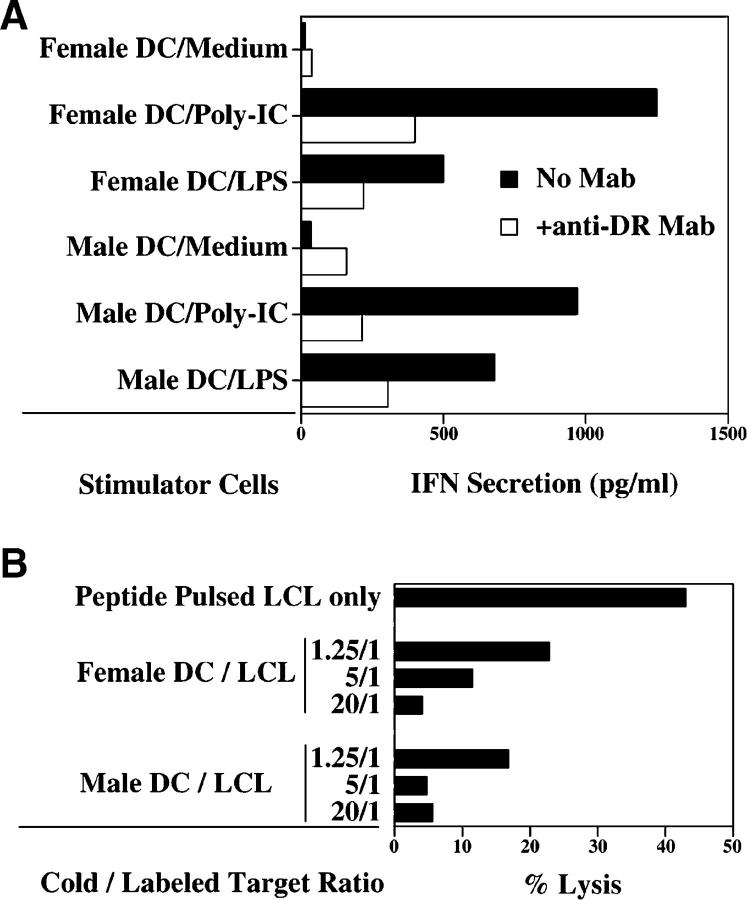

Because the T cell response did not distinguish between DBX and DBY peptides, we undertook further experiments to determine whether DBX and DBY epitopes were equally presented after exogenous processing of full-length recombinant protein. Using an IFN-γ release assay, clone 2F9 was tested for reactivity against HLA-DRB1*1501 male DCs pulsed with recombinant DBX and DBY proteins as well as a control irrelevant recombinant protein (HIV p24). Clone 2F9 responded to DCs pulsed with either of the three recombinant proteins but not to unpulsed DCs (unpublished data). These results suggested that maturation of DCs might result in presentation of endogenous DBY or DBX epitopes to the T cells. We then tested the capacity of female and male DCs matured with synthetic poly-IC or LPS to stimulate T cell clone 2F9. As shown in Fig. 4 A, both male and female DCs were recognized after in vitro maturation, indicating that both endogenous DBX and DBY epitopes were processed and presented to the T cell clone. In both male and female DCs, T cell recognition was inhibited by anti–HLA-DR mAb (Fig. 4 A). The endogenous processing of DBX and DBY peptides in mature female and male DCs was further confirmed in cold target inhibition experiments. As shown in Fig. 4 B, cytolytic activity of clone 2F9 toward DBY30–48–pulsed and 51Cr-labeled EBV B cells was significantly inhibited by the addition of unlabeled female or male DCs that had previously been matured with LPS.

Figure 4.

T cell clone 2F9 recognizes DBX and DBY antigens endogenously processed and presented by mature DCs. (A) Female and male HLA-DRB1*1501 DCs (104/well) were incubated for 24 h with medium alone or poly-(I)-poly-(C) to induce maturation. T cell clone 2F9 (104/well) was then added to the wells in the presence of IL-2. After 18 h of incubation, secretion of IFN-γ was determined in cocultures using ELISA. (B) Clone 2F9 cytolytic activity toward DBY30–48–pulsed 51Cr-labeled EBV B cells (LCL) at an E/T ratio of 1:1 was inhibited by the addition of mature unlabeled HLA-DRB1*1501 female or male DCs. Three ratios of unlabeled/labeled targets were tested in this experiment.

DBY Induces an Antibody Response after Allogeneic HSCT.

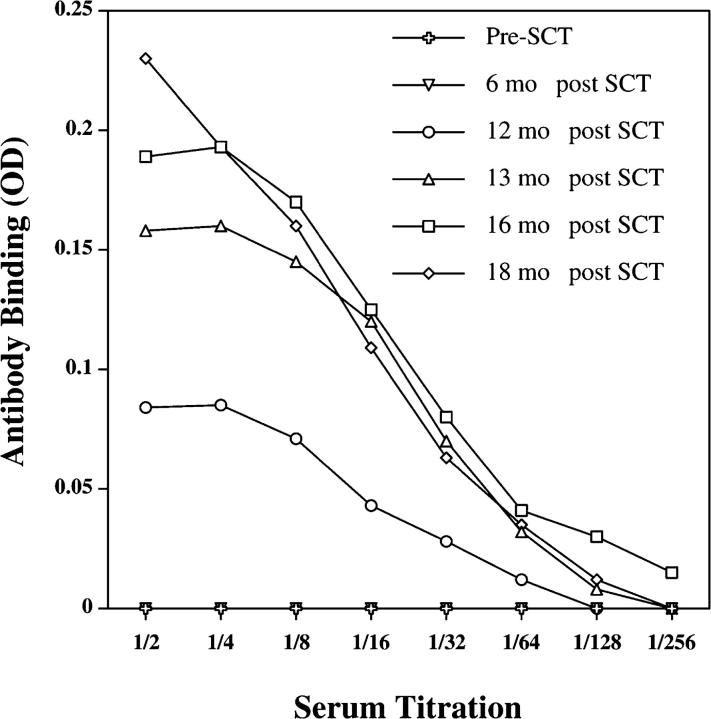

To further characterize the immune response to DBY and DBX, we also determined whether an antibody response to these antigens developed after allogeneic transplantation. Using an ELISA assay, serum samples collected at various times before and after HSCT were tested for the presence of IgG antibody to recombinant DBY protein. Titration curves shown in Fig. 5 show the presence of antibody reactive with DBY protein starting 12 mo after transplantation and increasing thereafter. No reactivity was detected before or 6 mo after transplant, indicating that the antibody response developed relatively late after HSCT. Remarkably, the DBY-specific CD4+ T cell response was readily detectable 8 mo after transplantation (Fig. 1 B). Taken together, these data provide evidence for the development of a coordinated T and B cell immune response to DBY antigen after allogeneic HSCT.

Figure 5.

DBY antigen elicits an antibody response after HSCT. IgG antibodies to recombinant DBY protein were detected by ELISA in patient serum samples collected at various times after allogeneic HSCT. Results are presented as serum titrations. Nonspecific reactivity to a control recombinant protein (HIV p24) was subtracted from each value.

The Antibody Response Is Specific for DBY Antigen.

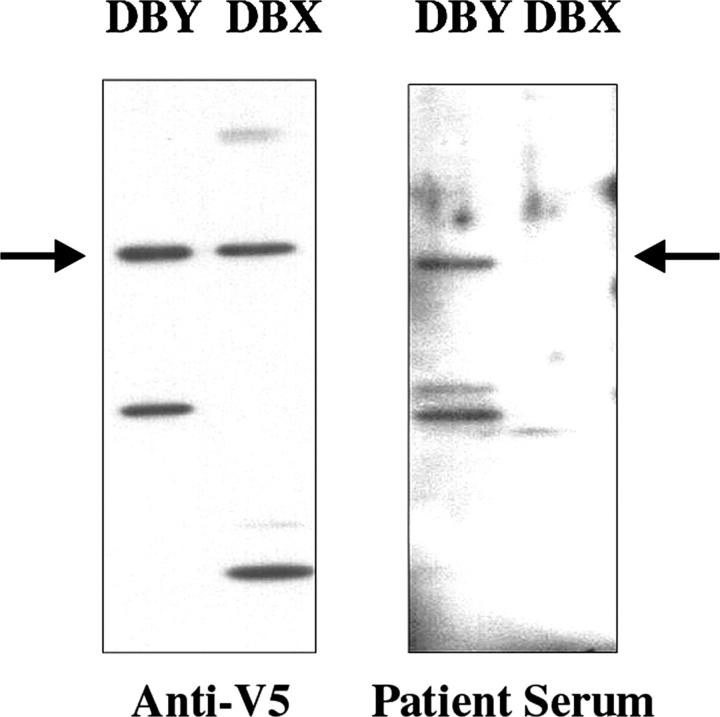

The specificity of the antibody response measured by ELISA was also examined by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 6, immunoblotting with an anti-V5 epitope antibody demonstrated equivalent loading of recombinant DBY and DBX. Patient serum collected 21 mo after HSCT was only reactive with DBY and not with recombinant DBX protein. In contrast to the T cell response, which did not appear to differentiate between DBX and DBY epitopes, the antibody response was specific for DBY.

Figure 6.

The antibody response after HSCT is specific for DBY antigen. DBX and DBY recombinant proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferred on nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with either an anti-V5 mAb (left) or patient serum collected 21 mo after HSCT (right). Degradation products generating distinct patterns for DBX and DBY are noticeable in the figure.

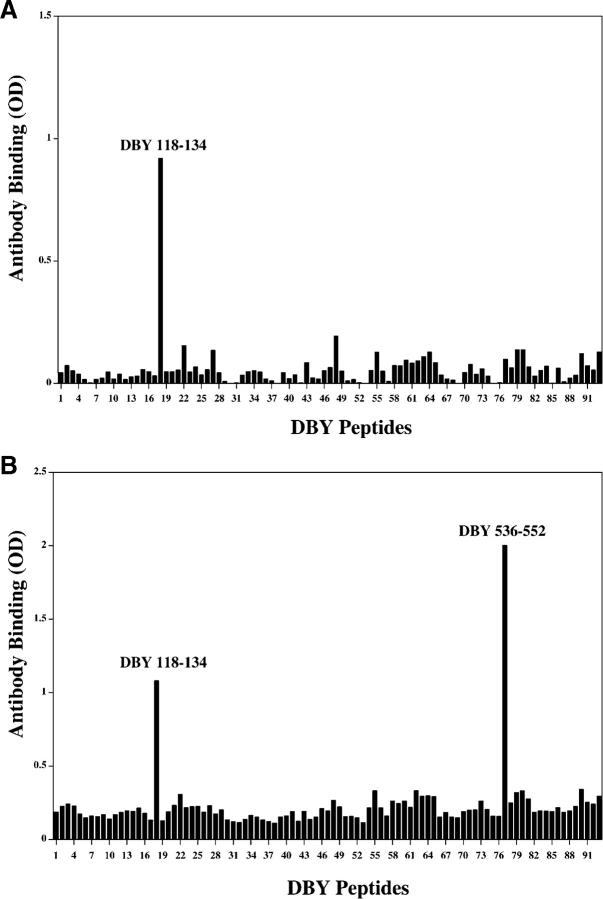

The DBY-specific Antibody Response Continues to Evolve 21 mo after HSCT.

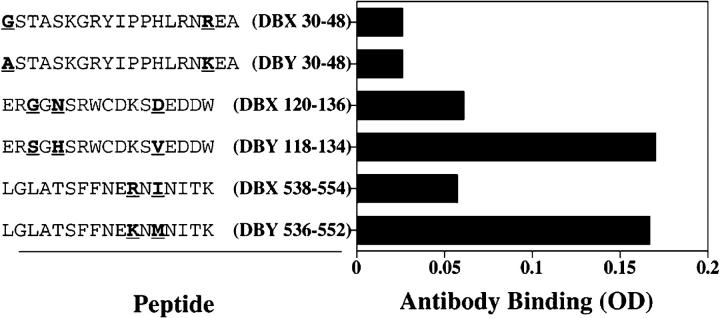

To further characterize the antibody response after allogeneic HSCT, the same set of 93 overlapping peptides used in the ELISPOT experiments was used in ELISA to define the specificity of the antibody response. As shown in Fig. 7 A, serum collected 16 mo after HSCT was reactive with a single DBY peptide (DBY118–134), distinct from the T cell epitope. The same reactivity was found with patient serum collected 5 mo later. However, the 21-mo sample also reacted with an additional epitope, DBY536–552 (Fig. 7 B). These results indicate that the antibody response to DBY antigen continued to evolve almost 2 yr after transplant by targeting a new DBY epitope. Both of the DBY peptides recognized by patient serum contained amino acid polymorphisms that are not present in DBX. The specificity of the antibody response for DBY antigen was therefore tested in ELISA using corresponding DBX and DBY peptides. Results of this analysis shown in Fig. 8, confirm that the antibody response was specifically directed against the two DBY peptides but not to the corresponding DBX peptides. In this experiment, peptides representing both DBX and DBY T cell epitopes were also tested and no antibody response to either of these peptides was detected in patient serum.

Figure 7.

The antibody response to DBY continues to evolve 21 mo after HSCT. (A) Patient serum collected 16 mo after transplant was used to map the DBY-specific antibody response. The serum was diluted at 1:10 and tested by ELISA for reactivity with each of the 93 overlapping DBY peptides. (B) The same experiment was repeated using identical procedures with serum collected 21 mo after HSCT.

Figure 8.

Antibody responses after HSCT are specific for DBY antigen. Patient serum collected 21 mo after HSCT was tested in ELISA for reactivity with two DBY B cell epitopes, the corresponding DBX peptides, and both DBY and DBX T cell epitopes. Peptide sequences are shown with the X-Y–disparate residues noted with bold underlined characters.

Discussion

mHAs play a critical role in GVHD and GVL immune responses after allogeneic HSCT. Several mHAs have previously been characterized in humans including four autosomal and eight H-Y T cell epitopes (5–8, 10–17). With only two exceptions (14, 17), these antigens have been found to be HLA class I–restricted peptides recognized by CD8+ CTLs. Increased numbers of CD8+ CTLs specific for some of these mHAs have been found in patients with active acute GVHD (22), but the role of mHA-specific CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of GVHD has received less attention. To date, only one HLA class II–restricted human mHA has been identified in T cells from a patient with acute GVHD (14) and another HLA class II–restricted mHA has been identified as a target of hematopoietic graft rejection (17). Here we describe a new HLA class II–restricted mHA presented by HLA-DRB1*1501 and recognized by CD4+ helper T cells. This epitope is the first T cell mHA associated with chronic GVHD. Like one of the previously identified HLA class II mHAs, this antigen is encoded by the male-specific gene DBY. Interestingly, another class II–restricted antigen encoded by DBY has also been identified in a murine model of GVHD after female to male transplantation (23). These observations in different species as well as the association with both acute and chronic GVHD suggest that DBY antigens are highly immunogenic to CD4+ female T cells that have not previously been exposed to these antigens during thymic maturation.

By using unstimulated PBMCs in our ELISPOT assay, we unequivocally demonstrated a relatively high level of expansion of DBY-specific T cells in vivo after transplantation. Phenotypic analysis of patient PBMCs 21 mo after HSCT showed that ∼25% of PBMCs were CD3+ CD4+ T cells (not depicted). Because the peptide ELISPOT assay detected ∼75 spot-forming cells/106 PBMCs, the frequency of CD4+ T cells specific for a single DBY peptide can be calculated to be ∼0.03%. This relatively high frequency is similar to that observed for EBV-specific CD4+ T helper cells (24). This high level of expansion of DBY-specific CD4+ T cells persisted for more than 1 yr and coincided with persistence of active chronic GVHD that required continuous immune-suppressive therapy. The persistence of this vigorous T cell response despite immune-suppressive therapy also suggests a high level of ongoing antigenic stimulation in vivo and an important role for DBY-specific T cells in the pathogenesis of chronic GVHD in this individual.

Among the 93 peptides representing the complete amino acid sequence of DBY, only 1 peptide was recognized by unstimulated patient cells. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that other DBY epitopes were also targeted, the DBY30–48 epitope appeared to be highly immunodominant in the immune response to DBY. Vogt et al. (14) have previously identified a different antigenic DBY peptide, DBY176–187, presented by HLA-DQ5. In their study, the corresponding DBX homologue was not recognized by the DBY-specific T cell clone, and X-Y–disparate residues included in the epitope were shown to be critical for its recognition by donor T cells. DBY30–48 also contains two amino acids that distinguish this peptide from its DBX homologue, but unlike the epitope presented by HLA-DQ5, both DBY30–48 and DBX30–48 were presented by HLA-DRB1*1501 and recognized by the CD4+ T cell clone. In dose-response experiments, the T cell clone responded equally well to autologous EBV B cells pulsed with either peptide. Similarly, patient PBMCs obtained at different times after transplant also responded similarly to both peptides. Class II–restricted epitopes are usually composed of a 9-mer core peptide flanked by stretches of amino acids on each side (25). The core peptide interacts directly with the HLA groove and the TCR, whereas flanking regions, sticking out of the HLA groove provide additional stability to the complex. In DBY30–48, the putative 9-mer core is 100% identical between DBX and DBY homologues. The only disparate residues are located in the flanking regions and these amino acids do not appear to affect the affinity for HLA class II molecules (DRB1*1501) or recognition by the TCR. In our experiments, relatively high concentrations of antigenic peptides were required to trigger response of the 2F9 clone, suggesting that these cells express a low affinity TCR. Remarkably, T cells specific for the previously characterized DQ5-restricted DBY peptide were also dependent on similarly high concentrations of peptide antigens in functional assays (14). It is currently unknown whether a general trend can be established from these two individual cases.

Polymorphic residues need not be included in the actual T cell epitope to influence the immunogenicity of an antigen. For example, recognition of HA-8 mHA results from the differential processing of an allelic gene product due to polymorphic residues located outside the actual epitope (6). We considered this possibility for DBY30–48 but we did not find any evidence of differential processing of the DBX and DBY homologous peptides. Importantly, both male and female DCs expressing HLA-DRB1*1501 were recognized at the same level after maturation. In addition, male and female DCs were equally effective in cold target inhibition assays, confirming the endogenous expression and recognition of both the DBY30–48 and DBX30–48 peptides by mature DCs. In these experiments, the processing of DBY30–48 followed the endogenous pathway of presentation similar to what has previously been described for DBY176–187 (14). However, the presentation of DBY30–48 required maturation of the DCs with either poly-IC or LPS. Previous studies have demonstrated that antigen processing in DCs is modified during maturation, resulting in the presentation of a new range of cryptic peptide antigens at the cell surface (26). Our findings suggest a similar method of antigen presentation for both DBY30–48 and DBX30–48 epitopes.

In addition to DBY-reactive T cells, the patient also developed an antibody response to the same antigen. Using synthetic DBY peptides we mapped the antibody response to two distinct B cell epitopes. In previous experiments we found that antibody responses specific for DBY mHA developed in ∼50% of male patients who received stem cell transplants from female donors (19). A map of the common DBY B cell epitopes was also established, demonstrating that antibody responses were primarily directed against regions of disparity between DBY and DBX. The two epitopes identified in this study are among these frequently targeted epitopes. It is interesting to note, however, that both DBY T cell epitopes characterized thus far (DBY30–48 and DBY176–187) were not found to be common B cell targets, presumably because the corresponding portions of the DBY protein are not readily accessible to the B cell receptor. These results further illustrate the complementary function of the two arms of the adaptive immune system to cover a wide range of epitopes within a given antigen.

Antibodies to a single DBY epitope first developed between 6 and 12 mo after HSCT, the date of the first reactive sample. Subsequently, the titer of this antibody response gradually increased until 16 mo after transplant. The acquisition of a new B cell antigen between 16 and 21 mo provided further evidence that B cell immunity to DBY was still evolving at that time. In comparison, the CD4+ helper T cell response, which was first detected 8 mo after transplant, continued to be directed against a single epitope. Also in contrast to the T cell response, the B cell response was specific for DBY and did not cross-react with recombinant DBX in Western blot assays. Antibody specificity for DBY was confirmed at the peptide level using an ELISA assay. Thus, although the patient developed both T and B cell immunity to DBY after HSCT, these results show that it was only the B cell response that distinguished between DBY and DBX.

After allogeneic HSCT, the patient developed acute GVHD, which evolved into chronic GVHD 3–4 mo after transplant. Therefore, our experiments were performed primarily with samples collected in the context of chronic GVHD. In this respect, the dual recognition of DBX and DBY by patient T cells is remarkable as it suggests the development of T cell immunity to an autoantigen. Similarities between chronic GVHD and autoimmune diseases have been well documented. In particular, common skin lesions in chronic GVHD are often similar to those seen in scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. A striking hallmark of autoimmune diseases is the development of antibodies as well as T cells reactive with a variety of autoantigens (27). Based on our findings, it is attractive to speculate that coordinated B and T cell responses similarly contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic GVHD. Donor specificity for recipient mHA is likely to be required for initiation of acute GVHD, but our studies suggest that the subsequent development of chronic GVHD might be associated with the recognition of T cell epitopes that do not discriminate between recipient and donor cells. Nevertheless, maintenance of chronic GVHD might be dependent on continuing specific recognition of recipient antigens by donor B cells. Although DBY is not expressed on the cell surface, this protein is widely expressed in many tissues and anti-DBY antibodies may contribute to the formation of immune complexes, which can enhance the uptake and presentation of the antigen from dying cells. As noted in our studies, maturation of DCs by nonspecific mechanisms can also lead to the presentation of DBY epitopes to donor T cells in vivo. Taken together, these mechanisms may well be contributing to the persistence of chronic GVHD in the patient we studied. Further studies in other individuals will be needed to confirm whether similarly coordinated B and T cell immune responses are commonly found in patients with chronic GVHD. In this regard, it should also be noted that DBY is only one of several Y-encoded proteins with closely related X homologues that are widely expressed in many tissues. Similar responses to other H-Y antigens may also play a role in the pathogenesis of chronic GVHD.

Previous mHA have been identified using T cells established in vitro and selected for their ability to differentially recognize recipient cells from donor cells in functional assays. Although such approaches have resulted in the characterization of several target antigens of acute GVHD, this method also biases the type of target epitopes that can be identified. In our series of experiments, unselected patient T cells were screened for reactivity against a large panel of potential target peptides. We subsequently isolated the reactive cells in vitro and further analyzed the specificity of the immune response. The dual recognition of DBX and DBY peptides was unexpected and illustrates the validity of our screening strategy for the identification of relevant antigens in GVHD. Although T cells specific for this new DBY epitope persisted at high levels for more than 1 yr, these cells would not have been detected if only clones reactive with recipient cells and not donor cells had been selected to characterize the GVHD response.

In summary, this study represents the first demonstration of a coordinated T cell–B cell response to mHA in the clinical context of chronic GVHD. These studies reveal a complex immune response that includes elements of autoimmunity as well as alloimmunity. The alloimmune response to DBY appears to be mediated primarily by donor B cells. In contrast, the autoimmune response to both DBY and DBX is mediated primarily by donor CD4+ T cells. These observations further emphasize the intricate balance that develops during reconstitution of donor immunity after allogeneic stem cell transplantation when immunologic distinctions between autoantigens and persisting alloantigens become uncertain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Leah Gordon for assistance in obtaining patient samples.

This study is supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI29530 and HL70149 and the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Research Fund. E. Zorn is a Special Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. R.J. Soiffer is a Clinical Research Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Abbreviations used in this paper: GVL, graft-versus-leukemia; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; mHA, minor histocompatibility antigen.

References

- 1.Simpson, E., D. Scott, E. James, G. Lombardi, K. Cwynarski, F. Dazzi, M. Millrain, and P.J. Dyson. 2002. Minor H antigens: genes and peptides. Transpl. Immunol. 10:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkenburg, J.H., W.A. Marijt, M.H. Heemskerk, and R. Willemze. 2002. Minor histocompatibility antigens as targets of graft-versus-leukemia reactions. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 9:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riddell, S.R., M. Murata, S. Bryant, and E.H. Warren. 2002. Minor histocompatibility antigens–targets of graft versus leukemia responses. Int. J. Hematol. 76:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murata, M., E.H. Warren, and S.R. Riddell. 2003. A human minor histocompatibility antigen resulting from differential expression due to a gene deletion. J. Exp. Med. 197:1279–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.den Haan, J.M., N.E. Sherman, E. Blokland, E. Huczko, F. Koning, J.W. Drijfhout, J. Skipper, J. Shabanowitz, D.F. Hunt, V.H. Engelhard, et al. 1995. Identification of a graft versus host disease-associated human minor histocompatibility antigen. Science. 268:1476–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brickner, A.G., E.H. Warren, J.A. Caldwell, Y. Akatsuka, T.N. Golovina, A.L. Zarling, J. Shabanowitz, L.C. Eisenlohr, D.F. Hunt, V.H. Engelhard, et al. 2001. The immunogenicity of a new human minor histocompatibility antigen results from differential antigen processing. J. Exp. Med. 193:195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spierings, E., A.G. Brickner, J.A. Caldwell, S. Zegveld, N. Tatsis, E. Blokland, J. Pool, R.A. Pierce, S. Mollah, J. Shabanowitz, et al. 2003. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-3 arises from differential proteasome-mediated cleavage of the lymphoid blast crisis (Lbc) oncoprotein. Blood. 102:621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.den Haan, J.M., L.M. Meadows, W. Wang, J. Pool, E. Blokland, T.L. Bishop, C. Reinhardus, J. Shabanowitz, R. Offringa, D.F. Hunt, et al. 1998. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1: a diallelic gene with a single amino acid polymorphism. Science. 279:1054–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson, E., D. Scott, and P. Chandler. 1997. The male-specific histocompatibility antigen, H-Y: a history of transplantation, immune response genes, sex determination and expression cloning. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:39–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meadows, L., W. Wang, J.M. den Haan, E. Blokland, C. Reinhardus, J.W. Drijfhout, J. Shabanowitz, R. Pierce, A.I. Agulnik, C.E. Bishop, et al. 1997. The HLA-A*0201-restricted H-Y antigen contains a posttranslationally modified cysteine that significantly affects T cell recognition. Immunity. 6:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce, R.A., E.D. Field, J.M. den Haan, J.A. Caldwell, F.M. White, J.A. Marto, W. Wang, L.M. Frost, E. Blokland, C. Reinhardus, et al. 1999. Cutting edge: the HLA-A*0101-restricted HY minor histocompatibility antigen originates from DFFRY and contains a cysteinylated cysteine residue as identified by a novel mass spectrometric technique. J. Immunol. 163:6360–6364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogt, M.H., R.A. de Paus, P.J. Voogt, R. Willemze, and J.H. Falkenburg. 2000. DFFRY codes for a new human male-specific minor transplantation antigen involved in bone marrow graft rejection. Blood. 95:1100–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogt, M.H., E. Goulmy, F.M. Kloosterboer, E. Blokland, R.A. de Paus, R. Willemze, and J.H. Falkenburg. 2000. UTY gene codes for an HLA-B60-restricted human male-specific minor histocompatibility antigen involved in stem cell graft rejection: characterization of the critical polymorphic amino acid residues for T-cell recognition. Blood. 96:3126–3132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogt, M.H., J.W. van den Muijsenberg, E. Goulmy, E. Spierings, P. Kluck, M.G. Kester, R.A. van Soest, J.W. Drijfhout, R. Willemze, and J.H. Falkenburg. 2002. The DBY gene codes for an HLA-DQ5-restricted human male-specific minor histocompatibility antigen involved in graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 99:3027–3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, W., L.R. Meadows, J.M. den Haan, N.E. Sherman, Y. Chen, E. Blokland, J. Shabanowitz, A.I. Agulnik, R.C. Hendrickson, C.E. Bishop, et al. 1995. Human H-Y: a male-specific histocompatibility antigen derived from the SMCY protein. Science. 269:1588–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren, E.H., M.A. Gavin, E. Simpson, P. Chandler, D.C. Page, C. Disteche, K.A. Stankey, P.D. Greenberg, and S.R. Riddell. 2000. The human UTY gene encodes a novel HLA-B8-restricted H-Y antigen. J. Immunol. 164:2807–2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spierings, E., C.J. Vermeulen, M.H. Vogt, L.E. Doerner, J.H. Falkenburg, T. Mutis, and E. Goulmy. 2003. Identification of HLA class II-restricted H-Y-specific T-helper epitope evoking CD4+ T-helper cells in H-Y-mismatched transplantation. Lancet. 362:610–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kollman, C., C.W. Howe, C. Anasetti, J.H. Antin, S.M. Davies, A.H. Filipovich, J. Hegland, N. Kamani, N.A. Kernan, R. King, et al. 2001. Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood. 98:2043–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miklos, D.B., H.T. Kim, E. Zorn, E.P. Hochberg, L. Guo, A. Mattes-Ritz, S. Viatte, R.J. Soiffer, J.H. Antin, and J. Ritz. 2004. Antibody response to DBY minor histocompatibility antigen is induced after allogeneic stem cell transplantation and in normal female donors. Blood. 103:353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallusto, F., and A. Lanzavecchia. 1994. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor α. J. Exp. Med. 179:1109–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Currier, J.R., E.G. Kuta, E. Turk, L.B. Earhart, L. Loomis-Price, S. Janetzki, G. Ferrari, D.L. Birx, and J.H. Cox. 2002. A panel of MHC class I restricted viral peptides for use as a quality control for vaccine trial ELISPOT assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 260:157–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutis, T., G. Gillespie, E. Schrama, J.H. Falkenburg, P. Moss, and E. Goulmy. 1999. Tetrameric HLA class I-minor histocompatibility antigen peptide complexes demonstrate minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in patients with graft-versus-host disease. Nat. Med. 5:839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott, D., C. Addey, P. Ellis, E. James, M.J. Mitchell, N. Saut, S. Jurcevic, and E. Simpson. 2000. Dendritic cells permit identification of genes encoding MHC class II-restricted epitopes of transplantation antigens. Immunity. 12:711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leen, A., P. Meij, I. Redchenko, J. Middeldorp, E. Bloemena, A. Rickinson, and N. Blake. 2001. Differential immunogenicity of Epstein-Barr virus latent-cycle proteins for human CD4(+) T-helper 1 responses. J. Virol. 75:8649–8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rammensee, H.G. 1995. Chemistry of peptides associated with MHC class I and class II molecules. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delamarre, L., H. Holcombe, and I. Mellman. 2003. Presentation of exogenous antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II molecules is differentially regulated during dendritic cell maturation. J. Exp. Med. 198:111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Muhlen, C.A., E.K. Chan, E. Angles-Cano, M.J. Mamula, I. Garcia-De La Torre, and M.J. Fritzler. 1998. Advances in autoantibodies in SLE. Lupus. 7:507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]