Abstract

Aims

To elucidate the factors influencing the sensitivity of Bacillus subtilis spores to killing and disruption by mechanical abrasion, and the mechanism of stimulation of spore germination by abrasion.

Methods and Results

Spores of B. subtilis strains were abraded by shaking with glass beads in liquid or the dry state, and spore killing, disruption and germination were determined. Dormant spores were more resistant to killing and disruption by abrasion than were growing cells or germinated spores. However, dormant spores of the wild-type strain with or without most coat proteins removed, spores of strains with mutations causing spore coat defects, spores lacking their large depot of dipicolinic acid (DPA) and spores with defects in the germination process exhibited essentially identical rates of killing and disruption by abrasion. When spores lacking all nutrient germinant receptors were enumerated by plating directly on nutrient medium, abrasion increased the plating efficiency of these spores before killing them. Spores lacking all nutrient receptors and either of the two redundant cortex-lytic enzymes behaved similarly in this regard, but the plating efficiency of spores lacking both cortex-lytic enzymes was not stimulated by abrasion.

Conclusions

Dormant spores are more resistant to killing and disruption by abrasion than are growing cells or germinated spores, and neither the complete coats nor DPA are important in spore resistance to such treatments. Germination is not essential for spore killing by abrasion, although abrasion can trigger spore germination by activation of either of the spore’s cortex-lytic enzymes.

Significance and Importance

This work provides new insight into the mechanisms of the killing, disruption and germination of spores by abrasion and makes the surprising finding that at least much of the spore coat is not important in spore resistance to abrasion.

Keywords: spores, Bacillus, spore killing, spore disruption, spore germination

INTRODUCTION

Spores of various Bacillus species are metabolically dormant and much more resistant than the corresponding growing cells to a variety of environmental stresses including heat, desiccation and toxic chemicals (Nicholson et al. 2000). Spore resistance is due to a number of factors including the: i) low water content of the spore core; ii) protection of spore DNA by its saturation with a spore-specific group of DNA binding proteins; iii) repair of DNA damage following spore germination; iv) relative impermeability of the inner spore membrane to hydrophilic chemicals; and v) multilamellar spore coats that restrict access of enzymes and chemicals to the spore’s interior (Gerhardt and Marquis 1989; Setlow and Setlow 1996; Driks 1999; Nicholson et al. 2000; Driks 2002a,b; Takamatsu and Watabe 2002; Cortezzo and Setlow 2005).

Spores are also quite resistant to mechanical forces, including sonication and high pressure (Belgrader et al. 1999; Nicholson et al. 2000; Chandler et al. 2001). While the mechanism of spore killing by sonication is not known, high pressure kills spores by first promoting spore germination (Nicholson et al. 2000). Pressures of 100–200 megaPascals (MPa) trigger spore germination by activating the spore’s nutrient germinant receptors, while germination triggered by pressures of 500–600 MPa does not require these germinant receptors (Wuytack et al. 2000; Paidhungat et al. 2002). Rather the latter high pressures appear to directly cause the release of the spore core’s large depot (20% of core dry wt) of pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid (DPA)) that is chelated with divalent cations, predominantly Ca2+ (Wuytack et al. 2000; Paidhungat et al. 2002). This release of Ca2+-DPA then triggers the hydrolysis of the spore’s peptidoglycan cortex leading to completion of the germination process (Setlow 2003).

A third mechanical treatment that can kill spores is abrasion, which has generally been effected by shaking spores with glass beads either in liquid or the dry state. Abrasion in liquid has been used in some cases to disrupt spores prior to PCR analyses of spore DNA, with varying degrees of success (Johns et al. 1994; Reif et al. 1994; Levi et al. 2003; Priha et al. 2004). Abrasion in the dry state has also been used to allow extraction and eventual purification of spore-specific proteins that are rapidly degraded and/or modified during spore germination (Setlow 1975; Loshon et al. 1982). While there is thus some applied interest in spore disruption by abrasion, the factors that determine spore abrasion resistance are not known. It has been suggested that one function of the spore coat is to protect spores against abrasion (Minamu et al. 1977; Driks 1999; Henriques and Moran 2000; Driks 2002b; Takamatsu and Watabe 2002). While this is logical given the significant cross-linking of proteins in the spore coat and thus the potential rigidity of this structure (Driks 1999; Henriques and Moran 2000; Driks 2002a,b; Takamatsu and Watabe 2002; Ragkousi and Setlow 2004), this suggestion has never been tested. Much is known about the composition and structure of the B. subtilis spore coat and many strains are available lacking individual coat proteins, including proteins involved in coat assembly. Thus it should be possible to test the role of the spore coat as well as individual coat proteins in spore resistance to abrasion, and the results of such tests comprise some of the information in this report.

In addition to spore disruption and killing, abrasion in liquid also triggers the germination of spores of B. megaterium (Rode and Foster 1960). There are a variety of ways in which germination of spores of Bacillus species can be triggered including the: i) binding of specific nutrients to receptors located in the spore’s inner membrane; ii) activation of CwlJ, one of the spore’s two redundant cortex-lytic enzymes (the other is SleB) located in the spore’s outer layers by Ca2+-DPA; and iii) degradation of the spore’s peptidoglycan cortex by exogenous lytic enzymes (Bagyan and Setlow 2002; Chirakkal et al. 2002; Setlow 2003). The availability of mutant strains of B. subtilis lacking one or many of the gene products involved in spore germination should make it possible to determine how abrasion stimulates spore germination, and this information might provide new insight into germination itself and the regulation of proteins involved in germination. The outcomes of studies on this topic comprise a second group of results reported in this communication.

Finally, since germinated spores are invariably more sensitive to stress treatments than are dormant spores (Nicholson et al. 2000), it seems likely that germinated spores will be more sensitive to abrasion than are dormant spores. Consequently, it is possible that spore germination is essential for spore killing by abrasion, as it is for spore killing by high pressures (Nicholson et al. 2000). Again, the availability of strains of B. subtilis with specific defects in spore germination should make it feasible to test the latter proposal, and the outcomes of such tests comprise the third group of results reported in this communication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. subtilis strains used and preparation of spores and growing cells

The B. subtilis strains used in this work are isogenic derivatives of strain 168 and are listed in Table 1. The wild-type strain was PS533. Spores were prepared at 37°C on 2xSG medium plates without antibiotics, and the spores were harvested, cleaned and stored as described (Nicholson and Setlow 1990; Paidhungat et al. 2000). Spores of strain FB122 were also prepared on plates containing 100 mg l−1 DPA (Paidhungat et al. 2000). FB122 spores prepared without and with added DPA had ≥2% and 75% of wild-type spore levels of DPA, respectively, determined as described (Rotman and Fields 1967; Paidhungat et al. 2001). All spore preparations used were free (≥98%) of germinated spores, sporulating cells and cell debris as determined by phase contrast microscopy. Spores were chemically decoated with urea-SDS-dithiothreitol and washed as described (Bagyan et al. 1998). For one experiment spores were incubated in 1 mol l−1 NaOH for 4 hr at 23°C, either with or without prior sonication as described (Minamu et al. 1977), giving ~ 99% apparent spore killing (Setlow et al. 2002); the killed spores were washed six times with sterile water.

Table 1.

B. subtilis strains used*

| Strain | Genotype and description | Source (reference)a |

|---|---|---|

| FB72b | ger3 (gerA::spc gerB::cat gerK::ermC) Cmr MLSr Spr | (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000) |

| FB111b | cwlJ::tet Tcr | (Paidhungat et al. 2001) |

| FB112b | sleB::spc Spr | (Paidhungat et al. 2001) |

| FB113b | cwlJ::tet sleB::spc Spr Tcr | (Paidhungat et al. 2001) |

| FB114b | ger3 sleB::tet Cmr MLSr Spr Tcr | (Paidhungat et al. 2001) |

| FB115b | ger3 cwlJ::tet Cmr MLSr Spr Tcr | (Paidhungat et al. 2001) |

| FB122b | sleB spoVF | (Paidhungat et al. 2001) |

| JZ50c | cotXYZ::neo Kmr | (Zhang et al. 1993) |

| KB29b | gerQ::spc Spr | (Ragkousi and Setlow 2004) |

| KB81b | tgl::ermC MLSr | (Ragkousi and Setlow 2004) |

| KB99b | cotA::cat Cmr | RL50→PS832 |

| PS533b | wild type [pUB110] Kmr | (Setlow and Setlow 1996) |

| PS832b | wild-type | laboratory stock |

| PS2495b | sodA::cat Cmr | (Casillas-Martinez and Setlow 1997) |

| PS3328b | cotE::tet Tcr | (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000) |

| PS3634b | cotXYZ::neo Kmr | JZ50→PS832 |

| RL50d | cotA::cat Cmr | (Donovan et al. 1987) |

Abbreviations used are: Cmr – chloramphenicol (3 mg l−1) resistance; Kmr- resistance to kanamycin (10 mg l−1); MLSr – resistance to erythromycin (1 mg l−1) and lincomycin (25 mg l−1); Spr – spectinomycin (100 mg l−1) resistance; and Tcr – tetracycline (10 mg l−1) resistance.

DNA from the strain to the left of the arrow was used to transform the strain to the right of the arrow.

Genetic background is PS8322.

Genetic background is JH642.

Genetic background is PY17.

Prior to germination spores in water were heat shocked (30 min; 70°C) to synchronize and accelerate subsequent germination. After the heat shocked spores were cooled, they were germinated at 37° and an optical density at 600 nm (O.D.600nm) of 1 in LB medium (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000) plus 4 mmol l−1 L-alanine. After 45 min when ≥95% of the spores had initiated germination as seen by phase contrast microscopy, the suspension was centrifuged, washed once at 24°C with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (25 mmol l−1 KPO4 (pH 7.4) - 0.15 mol l−1 NaCl) and suspended at an O.D.600nm of 10 in PBS at 24°C. Vegetative cells of B. subtilis were prepared by growth at 37°C in LB medium (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000) to an O.D.600nm of ~0.75, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with PBS at 24°C and were suspended at an O.D.600nm of 10 in PBS at 24°C. Prior to freeze-drying, germinated spores and vegetative cells were suspended in 5 g l−1 trehalose to preserve viability upon drying (Leslie et al. 1995; Potts 1994).

Spore abrasion in liquid

Spores were abraded in liquid in either PBS or in 50 mmol l−1 Tris-HCl (pH 7.0); where tested results in PBS or in Tris-HCl were identical. Prior to abrasion in liquid, dormant spores were first heat shocked (30 min; 70°C) to kill any contaminating germinated spores or growing cells and then cooled to 24°C. This heat treatment had no effect on wild-type spore killing. For abrasion in liquid, 1.6 ml of dormant or germinated spores or growing cells at an O.D.600nm of 1, 5, 10 or 25 were shaken at 24°C in a Mini-Beadbeater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) with 2 g of 100 μm glass beads. For analysis of spore or cell viability, aliquots (10 μl) were removed from the Beadbeater capsule, diluted serially in water (most dormant spores) or PBS (germinated spores, some dormant spores and growing cells) and 10 μl aliquots of various dilutions spotted in duplicate on LB medium (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000) agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics. The plates were incubated for ~24 h at 37°C and colonies were counted; incubation for longer times gave no increase in colonies. In some experiments, dormant spores were initially diluted 1/100 in 50 mmol l−1 Ca2+-DPA (pH 8.0), the mix incubated for 60 min at 24°C (Paidhungat et al. 2001) and then further diluted and aliquots spotted on plates and survivors determined as described above. This method will recover spores that lack all nutrient germinant receptors, as well as FB122 spores that lack DPA (Paidhungat et al. 2001; Paidhungat and Setlow 2000). In one experiment with decoated wild-type and FB113 (cwlJ sleB) spores, the spores were incubated in a hypertonic medium containing lysozyme (25 mg l−1) prior to dilution and plating to recover the spores (Popham et al. 1996). Spores that lack both CwlJ and SleB cannot complete germination, since they are unable to degrade their peptidoglycan cortex, but if they are first decoated to allow access of exogenous enzymes to the spore cortex, cwlJ sleB spores can be germinated and recovered by treatment with lysozyme (Popham et al. 1996; Paidhungat et al. 2001; Setlow et al. 2001). However, this lysozyme treatment must be carried out in a hypertonic medium, since lysozyme degrades the peptidoglycan of both the spore cortex and germ cell wall and this can result in the lysis of the germinated spore. In contrast, CwlJ and SleB act only on the spore cortex (Popham et al. 1996). Spores incubated with NaOH were also recovered by lysozyme treatment in hypertonic medium, since NaOH inactivates both CwlJ and SleB (Setlow et al. 2002).

In some experiments, spores were abraded in liquid at an O.D.600nm of 25 as described above, aliquots (50 μl) were removed from the Beadbeater capsule at various times, centrifuged in a microcentrifuge and the O.D.260nm of the supernatant fluid was measured to assess the release of both DPA and nucleic acids. Control experiments showed that after 5 min of abrasion in liquid <5% of additional material absorbing at 260 nm was released with an additional 2 min of abrasion, and that ~35% of the released O.D.260nm was due to nucleic acids and ~60% was due to DPA with the remainder due to protein. In other experiments, the protein in the supernatant fluid from abraded spores obtained as described above was determined directly (Bradford 1976). All breakage experiments in liquid were carried out at least twice, and there was ≤ 12% variation in the rates of spore killing or release of protein or material absorbing at 260 nm between replicates.

Spore abrasion in the dry state

For breakage of spores or growing cells in the dry state, approximately 3 mg dry wt of lyophilized spores or growing cells were shaken with 75 mg of glass beads and a stainless steel ball in a dental amalgamator (Wig-L-Bug; Crescent Dental Mfg. Co., Chicago, IL, USA). Samples were shaken at room temperature for intervals of at most 1 min, and aliquots of ~10 mg dry wt were removed from the Wig-L-Bug capsule at various times, suspended in 0.6 ml of PBS, incubated on ice with intermittent vortexing for 30 min and spore viability determined as described above. 0.5 ml of the latter suspension was also mixed with 0.5 ml of 1 mol l−1 perchloric acid, the mix incubated at 70°C for 30 min to release and hydrolyze all nucleic acid, the samples centrifuged and the O.D.260nm of the supernatant fluid measured to determine the relative amounts of spores or growing cells in different samples. All breakage experiments in the dry state were carried out at least twice, and there was ≤ 15% variation in the rates of cell or spore killing between replicates.

RESULTS

Sensitivity of dormant and germinated spores and growing cells to abrasion

As expected, growing cells of wild-type B. subtilis were killed more rapidly by abrasion in liquid than were dormant spores, while germinated spores were intermediate in their sensitivity (Fig. 1A). Rates of dormant spore killing by abrasion in liquid were essentially identical (within 8%) with spores at an initial O.D.600nm of 1, 10 or 25 (data not shown), indicating that material released from disrupted spores (e.g.-Ca2+-DPA) was not stimulating the germination and thus perhaps the killing of other spores in the population. Growing cells were also most sensitive to abrasion in the dry state and dormant spores were the most resistant (Fig. 1B; note that the kink after 1 min in the inactivation curve, in particular for cotE spores, was not seen in all experiments). The same relative sensitivities to abrasion in liquid were also seen when growing cell or spore disruption was assessed by measurement of the release of either protein or material absorbing at 260 nm (Fig. 2; and data not shown).

Fig. 1A, B.

Loss of viability during abrasion in A) liquid or B) the dry state of dormant and germinated spores and growing cells. Dormant and germinated spores and growing cells of various strains were abraded in liquid (PBS) at an O.D.600nm of 10 or in the dry state, and viability was measured as described in Methods. The symbols used are: ○, dormant PS533 (wild-type) spores; τ, germinated PS533 spores; σ, growing PS533 cells; ν, dormant PS3328 (cotE) spores; □, dormant PS3634 (cotXYZ) spores; and λ, dormant KB81 (tgl) spores. Values for dormant spores of strains KB29 (gerQ), KB99 (cotA) and PS2495 (sodA), and for chemically decoated dormant spores of strain PS533 were within the range of values for the dormant spores shown in this figure (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Disruption of dormant spores, germinated spores and growing cells by abrasion in liquid. Dormant and germinated spores and growing cells of strain PS533 (wild-type), all at an O.D.600nm of 25, were abraded in liquid (PBS) and release of protein was measured as described in Methods. The symbols used are: ○, dormant spores; σ, germinated spores; and τ, growing cells.

Lack of a role for the spore coat or DPA in spore abrasion resistance

Analysis of the killing by abrasion in liquid or the dry state of dormant spores of strains with mutations giving rise to spore coat defects revealed no notable effects of any of the mutations tested (Fig. 1). The spores tested included those of strains with mutations in: i) cotE that eliminates production of the spore’s outer coat and assembly of some inner coat proteins (Donovan et al. 1987; Driks 1999; Driks 2002b); ii) gerQ that encodes a major cross-linked protein in the spore coat (Ragkousi et al. 2003; Ragkousi and Setlow 2004); iii) tgl that encodes an enzyme that catalyzes at least some of the cross-linking of spore coat proteins (Kobayashi et al. 1996; Ragkousi and Setlow 2004); iv) cotX, Y and Z that encode components of the insoluble fraction of the spore coat (Zhang et al. 1993); v) sodA encoding the coat associated superoxide dismutase suggested to be involved in cross-linking of spore coat proteins (Henriques et al. 1998); or vi) cotA that encodes a laccase that may be involved in modification of coat proteins (Hullo et al. 2001). Chemical decoating of wild-type dormant spores with urea-SDS-dithiothreitol also did not reduce spore resistance to killing by abrasion in liquid or the dry state (data not shown); previous work showed that decoating also did not reduce spore resistance to high pressure (Paidhungat et al. 2002). Spores of strain FB122 (sleB spoVF) lacking DPA were also killed by abrasion in liquid or the dry state at the same rate as were either wild-type spores or FB122 spores containing DPA, when the spores were recovered with or without a Ca2+-DPA treatment (data not shown).

The lack of effect of mutations altering spore coat structure on spore resistance to abrasion in liquid was also seen when spore disruption was assessed by monitoring the release of either material absorbing at 260 nm or protein (Fig. 3; and data not shown). The rate of disruption of chemically decoated wild-type spores by abrasion in liquid as assessed by release of either material absorbing at 260 nm or protein was also essentially identical (within 5%) to that of intact wild-type spores (Fig. 3; and data not shown). The loss of the two spore cortex lytic enzymes, CwlJ and SleB, also did not alter the sensitivity of dormant spores to disruption by abrasion in liquid, as assessed by the release of either material absorbing at 260 nm or protein (Fig. 3; and data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Disruption of dormant spores of various strains by abrasion in liquid. Dormant spores of various strains at an O.D.600nm of 25 were abraded in liquid (Tris-HCl) and release of material absorbing at 260 nm was measured as described in Methods. The symbols for the strains used are: ○, PS533 (wild-type); λ, PS3328 (cotE); σ, PS3634 (cotXYZ); and, υ, KB81 (tgl). Values for dormant spores of strains KB29 (gerQ), KB99 (cotA), PS2495 (sodA) and FB113 (cwlJ sleB), and decoated spores of strain PS533 were within the ranges of values for spores shown in this figure (data not shown).

Previous work has shown that spores of a strain of B. thiaminolyticus can be sensitized to disruption by abrasion in liquid by removal of much coat protein by sonication followed by further removal of coat protein by incubation in NaOH (Minamu et al. 1977). However, a similar sonication regime and/or an even harsher NaOH treatment did not alter the rate of killing of B. subtilis spores by abrasion in liquid, when spores were recovered by lysozyme treatment in hypertonic medium (data not shown). Release of material absorbing at 260 nm was also essentially identical when untreated and NaOH-treated wild-type B. subtilis spores were abraded in liquid (data not shown).

Spore germination is not essential for spore killing by abrasion

The pathway for spore killing by abrasion in the dry state cannot be through triggering of spore germination by abrasion and then rapid killing of the less resistant germinated spores, since spore germination requires water. However, germination of B. megaterium spores can be triggered by abrasion in liquid (Rode and Foster 1960). As an initial test of the role of germination in the killing of B. subtilis spores by abrasion, we subjected wild-type spores abraded in liquid to a heat treatment (30 min; 70°C) that kills germinated spores but has no effect on dormant spores (Gerhardt and Marquis 1989; Paidhungat et al. 2000). This treatment did not reduce the viability of the abraded spores noticeably (Fig. 4). A 1 hr incubation of the abraded spores at 37°C followed by heat treatment also had no effect on spore viability (Fig. 4), indicating that abrasion in liquid does not potentiate the germination of a significant percentage of spores.

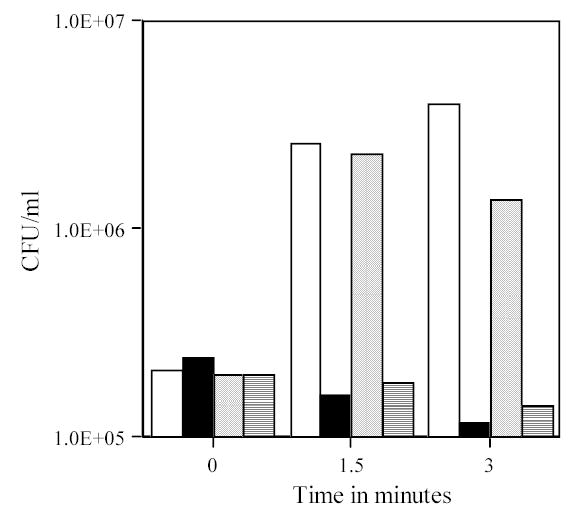

Fig. 4.

Viability and heat sensitivity of wild-type spores following abrasion in liquid. Spores of strain PS533 (wild-type) at an O.D.600nm of 25 were abraded in liquid (Tris-HCl) as described in Methods. At various times aliquots were diluted 1/100 in PBS and: 1) colony forming units (CFU) determined (open bars); 2) the 1/100 dilution heated 30 min at 70°C and CFU determined (solid bars); 3) the 1/100 dilution incubated 60 min at 37°C and CFU determined (dotted bars); and 4) the 1/100 dilution incubated for 60 min at 37°C, heated 30 min at 70°C and CFU determined (cross-hatched bars). All values shown are the CFU/ml in the spores at an O.D.600nm of 25, and are +/− 8%.

The results of the experiment noted above are consistent with germination not being necessary for spore killing by abrasion in liquid. However, the presence of a small percentage of germinated spores in abraded spore populations would not have been detected in this experiment. Indeed, the percentage of germinated spores in abraded spore populations might be expected to be low, since killing of germinated spores by abrasion is faster than is killing of dormant spores. To further assess the role of germination in spore killing by abrasion in liquid we examined the rates of killing of spores of strains with defects in the spore germination apparatus. Spores of strain FB113 lack the cortex-lytic enzymes CwlJ and SleB, either of which is essential for cortex hydrolysis during spore germination; these spores do not complete germination triggered by either nutrients or Ca2+-DPA but can be recovered by pretreatment of decoated spores with lysozyme in a hypertonic medium (Paidhungat et al. 2001; Setlow et al. 2001). When the viability of decoated cwlJ sleB spores was assessed after this pretreatment, these spores were killed at the same rate by abrasion in liquid as were decoated wild-type spores also given the same pretreatment (Fig. 5A). As expected from the latter result, spores of strains FB111 (cwlJ) and FB112 (sleB) that do not require lysozyme pretreatment for germination (Paidhungat et al. 2001) were also killed at the same rates by abrasion in liquid as were wild-type spores (data not shown).

Fig. 5A, B, C.

Loss of viability of dormant spores with germination defects during abrasion in liquid or the dry state. (A) Decated spores or (B) intact spores were abraded in liquid (Tris-HCl) at (A) an O.D.600nm of 5 or (B) at an O.D.600nm of 25 or (C) in the dry state, and viability measured after a pretreatment with either (A) lysozyme in hypertonic medium or (B, C) Ca2+-DPA as described in Methods. The symbols used are: □, PS533 (wild-type) spores; ○, FB72 (ger3) spores; and λ, FB113 (cwlJ sleB) spores. In (A) the CFU/ml of the PS533 spores at time zero was 8·108 and that for the FB113 spores was 6.2·108; in (B) at time zero the CFU/ml for the PS533 spores was 3·109, and for FB72 spores was 7·108; in C) at time zero the CFU/ml for the PS533 spores was 4·109 and for the FB72 spores was 109.

Spores of strain FB72 lack functional nutrient germinant receptors; these spores (termed ger3) do not respond to nutrients and only exhibit a low rate (0.02–0.2% total spores/day) of spontaneous germination (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000). However, a large percentage of ger3 spores can be recovered after a pretreatment with Ca2+-DPA that stimulates the germination of these spores (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000; Setlow 2003). When abraded spores were pretreated with Ca2+-DPA, both wild-type and ger3 spores exhibited very similar rates of killing by abrasion either in liquid or the dry state (Fig 5B, C). Spores lacking all three germinant receptors and either CwlJ or SleB (strains FB115 and FB114, respectively) also exhibited the same rates of killing by abrasion in liquid or the dry state as wild-type spores, when the viability of abraded spores was assessed after pretreatment with Ca2+-DPA (data not shown).

Stimulation of spore germination by abrasion

The findings given above indicate that germination is not a prerequisite for the killing of B. subtilis spores by abrasion in liquid. However, such treatment might still trigger or stimulate B. subtilis spore germination to some extent, as it does for B. megaterium spores (Rode and Foster 1960). Indeed, when plating of spores abraded in liquid was carried out without a pretreatment with Ca2+-DPA, ger3 spores exhibited a large increase in colony forming units (CFU) early in the abrasion process (Fig. 6, 7A; note log scale on vertical axis). The spores responsible for this large increase in CFU upon abrasion were heat sensitive, although incubation of abraded spores for 1 hr at 37°C gave no further increase in heat sensitive forms (Fig. 6). This increase in CFU with ger3 spores was seen during abrasion in both liquid and the dry state (Fig. 7A, B). During abrasion in liquid, similar results were obtained with spores at an O.D.600nm of 25 (Fig. 7A) and 1 (data not shown), again indicating that material released from spores disrupted early in the abrasion is not stimulating the germination of other spores in the population. Note that only 0.1–0.2% of total ger3 spores were detected in this experiment at time zero, as spore viability was measured without Ca2+-DPA pretreatment and consequently ger3 spores germinate extremely poorly (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000). Therefore, stimulation of germination of ger3 spores by abrasion will greatly increase apparent spore viability and make it only appear that these spores are more resistant to abrasion. Indeed, when the viability of ger3 spores during abrasion in liquid or the dry state was measured with a Ca2+-DPA treatment prior to plating, there was no difference in the rate of killing of wild-type and ger3 spores (Fig. 5B, C).

Fig. 6.

Viability and heat sensitivity of ger3 spores following abrasion in liquid. Spores of strain FB72 (ger3) at an O.D.600nm of 25 were abraded in liquid (Tris-HCl) as described in Methods. At various times aliquots were diluted 1/100 in PBS and: 1) CFU determined (open bars); 2) the 1/100 dilution heated 30 min at 70°C and CFU determined (solid bars); 3) the 1/100 dilution incubated 60 min at 37°C and CFU determined (dotted bars); and 4) the 1/100 dilution incubated for 60 min at 37°C, heated 30 min at 70°C and CFU determined (cross-hatched bars). All values shown are the CFU/ml in the spores at an OD600nm of 25, and are +/− 8%.

Fig. 7A, B.

Loss of viability of ger3 spores with or without cortex-lytic enzymes during abrasion in liquid or the dry state. Spores were abraded in (A) liquid (Tris-HCl) at an O.D.600nm of 25 or (B) in the dry state, and viability measured without Ca2+-DPA pretreatment as described in Methods. The symbols used are: □, PS533 (wild-type) spores; ○, FB72 (ger3) spores; υ, FB114 (ger3 sleB) spores; and σ, FB115 (cwlJ ger3) spores. In A) at time zero the CFU/ml from PS533 spores at an OD600nm of 25 was 3·109, and the corresponding values for FB72, FB114 and FB115 spores were 3·106, 6·106 and 1.5·106, respectively. In B) the values for CFU/ml at time zero for spores of FB72, FB114 and FB115 were 0.1%, 0.1% and 0.03% of that for intact PS533 spores.

The findings noted above strongly suggested that abrasion triggers B. subtilis spore germination by a pathway that does not require the spore’s nutrient germinant receptors. Alternative proteins whose activation by abrasion could stimulate spore germination include either or both of the spore’s cortex-lytic enzymes or one of the several spore-associated autolysins that normally do not gain access to the cortex in intact spores (Paidhungat and Setlow 2000; Setlow et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2001; Setlow 2003). To distinguish between these latter possibilities, we first examined the effects of abrasion in liquid on cwlJ sleB spores, determining the viability of the abraded spores without a pretreatment with lysozyme in hypertonic medium. The viability of cwlJ sleB spores analyzed without lysozyme pretreatment is <0.001% of the CFU/O.D.600nm of wild-type spores (Paidhungat et al. 2001; Ragkousi et al. 2003) and there was no increase in this value after 1 to 7 min of abrasion either in liquid or the dry state (data not shown).

The finding noted above suggested that it is through activation of CwlJ and/or SleB that abrasion triggers spore germination. Consequently, we measured the viability of ger3 cwlJ and ger3 sleB spores during abrasion either in liquid or the dry state, without pretreatment of the abraded spores with Ca2+-DPA (Fig. 7A, B). Strikingly, both ger3 cwlJ and ger3 sleB spores exhibited the same increases in apparent viability early in abrasion seen with ger3 spores alone (Fig. 7A, B).

CwlJ and SleB are both located in the spore’s outer layers (Bagyan and Setlow 2002; Chirakkal et al. 2002) and might be readily released from spores by abrasion. These released cortex-lytic enzymes might in turn trigger the germination of other abraded spores, since at least exogenously added SleB can cause germination of decoated spores (Makino et al. 1994). To test this scenario for triggering of spore germination by abrasion, a 1:1 mixture of cwlJ sleB (FB113) and wild-type (PS533) dormant spores was subjected to abrasion in liquid and spore viability was measured without lysozyme pretreatment on plates containing kanamycin (to identify wild-type spores) or spectinomycin plus tetracycline (to identify cwlJ sleB spores). While the wild-type spores exhibited the same rate of killing as seen when these spores were tested alone, there was no appearance of Spr Tcr colonies (≤0.001% of input FB113 spores; Fig. 8) as also found when the cwlJ sleB spores were abraded alone (data not shown), indicating that any CwlJ and SleB that may be released from wild-type spores by abrasion do not trigger the germination of cwlJ sleB spores. In addition, when the decoated FB113 spores in the spore mixture abraded in liquid were recovered by lysozyme treatment in hypertonic medium, the rate of FB113 spore killing was essentiall y identical to that of wild-type spores (data not shown), as expected based on results with FB113 spores abraded alone in liquid (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 8.

Viability of wild-type and cwlJ sleB spores abraded together in liquid. A 1:1 mixture of wild-type (PS533) and cwlJ sleB (FB113) spores each at an O.D.600nm of 2 was abraded in liquid (Tris-HCl) as described in Methods. At various times aliquots were plated directly on plates containing either kanamycin to recover wild-type spores or spectinomycin plus tetracycline to recover cwlJ sleB spores. The open bars denote values for wild-type spores and the dark bars give the maximum values for the cwlJ sleB spores, since no Spr Tcr colonies were recovered at any time.

DISCUSSION

The work in this communication leads to a number of new conclusions. First, most spore coat proteins are not essential for spore resistance to killing or disruption by abrasion. While many individual coat proteins can be lost with no loss in spore resistance properties, cotE spores and chemically decoated wild-type spores generally have greatly reduced resistance to a number of chemical agents as well as to lysozyme (Driks 1999, Nicholson et al. 2000; Driks 2002b; Ragkousi et al. 2003). However, cotE and chemically decoated spores exhibited resistance to killing and disruption by abrasion in liquid or the dry state that were essentially identical to that of intact wild-type spores. The spore core’s large depot of DPA is also not involved in protection of spores against abrasion, even though DPA is very important in protecting spores from several other treatments, including wet heat (Paidhungat et al. 2000). The identity of the component(s) essential for spore resistance to mechanical disruption is thus not clear. Possible candidates for such components are other parts of the insoluble fraction of the spore coat that comprises ~ 30% of coat protein and the very thick peptidoglycan cortex.

Second, the mechanism whereby spore germination is triggered by abrasion is through the activation of either of the spore’s two redundant cortex-lytic enzymes. These enzymes are present in the spore in an active form but do not act until triggered in some way by germination stimuli, Ca2+-DPA for CwlJ or some other stimulus for SleB (Bagyan and Setlow 2002; Chirakkal et al. 2002; Setlow 2003). Our work suggests that CwlJ and SleB can also be activated by mechanical damage to spores, perhaps by damage to the peptidoglycan cortex. Indeed, it has been suggested that physical changes in the cortical peptidoglycan may trigger activation of cortex-lytic enzymes (Setlow 2003). It is also tempting to speculate that the germination of spores damaged by abrasion may even be advantageous, since such damaged spores will undoubtedly be sensitive to exogenous lytic enzymes and thus at risk for destruction. Indeed, spore germination induced by abrasion in liquid is rapid, as this takes place during the abrasion process itself and not during subsequent incubation of the abraded spores. Spores abraded in the dry state must of course trigger germination only after resuspension in liquid and we would predict this would also be very rapid, but have not studied this further.

Third, it is somewhat surprising that it is not through spore germination that dormant spores are killed by abrasion in liquid. Presumably the rate of killing of spores that have suffered sufficient damage to trigger spore germination is fast relative to the rate of spore germination, such that spore germination is not an obligatory step in spore killing, although it can take place. Indeed, if the germination upon abrasion of ger3 spores mimics the situation with wild-type spores, as seems likely, then the percentage of total spores actually triggered to germinate by abrasion is very small, perhaps never being higher than 1%.

Finally, it appears clear that the mechanism of spore killing by abrasion is not through damage to the spore’s nutrient germinant receptors or to either or both of the spore’s cortex-lytic enzymes, since rates of killing by abrasion of spores lacking these proteins are essentially identical to that of wild-type spores, if appropriate conditions are used to recover the mutant spores. In addition, the rates of killing of decoated wild-type spores by abrasion in liquid are essentially identical when the abraded spores are plated directly or only after pretreatment with lysozyme in a hypertonic medium, a pretreatment that leads to recovery of spores lacking all germinant receptors or both cortex-lytic enzymes. A more likely mechanism for spore killing by abrasion is that killing is due to some physical damage to the cortical and germ cell wall peptidoglycan such that the spore’s inner membrane ruptures, as it will do when these peptidoglycan layers are removed, and rupture of the spore’s inner membrane does lead to spore death (Popham et al. 1996; Setlow et al. 2001, 2002).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM19698) and the Army Research Office. We are grateful to Katerina Ragkousi and Jenny Lee for some early experiments on this project, and to Arthur Aronson and Patrick Eichenberger for strains.

References

- Bagyan I, Noback M, Bron S, Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Characterization of yhcN, a new forespore-specific gene of Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1998;212:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagyan I, Setlow P. Localization of the cortex lytic enzyme CwlJ in spores of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1289–1294. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1219-1224.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgrader P, Hansford D, Kovacs GTA, Venkateswaran K, Mariella R, Jr, Milanovich F, Nasarabadi S, Okuzumi M, Pourahmadi F, Northrup MA. A minisonicator to rapidly disrupt bacterial spores for DNA analysis. Anal Chem. 1999;71:4232–4236. doi: 10.1021/ac990347o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein using the principles of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas-Martinez L, Setlow P. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, catalase, MrgA, and superoxide dismutase are not involved in resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to heat or oxidizing agents. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7420–7425. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7420-7425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DP, Brown J, Bruckner-Lea CJ, Olson L, Posakony GJ, Stults JR, Valentine NB, Bond LJ. Continuous spore disruption using radially focused, high-frequency ultrasound. Anal Chem. 2001;73:3784–3789. doi: 10.1021/ac010264j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirakkal H, O’Rourke M, Atrih A, Foster SJ, Moir A. Analysis of spore cortex lytic enzymes and related proteins in Bacillus subtilis endospore germination. Microbiology. 2002;148:2383–2392. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-8-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortezzo DE, Setlow P. Analysis of factors influencing the sensitivity of spores of Bacillus subtilis to DNA damaging chemicals. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:606–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan W, Zheng L, Sandman K, Losick R. Genes encoding spore coat polypeptides from Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driks A. The Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.1-20.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driks, A. (2002a) Proteins of the spore core and coat. In Bacillus subtilis and its Closest Relatives: from Genes to Cells ed. Sonenshein, A.L., Hoch, J.A. and Losick, R. pp. 527–535. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology.

- Driks A. Maximum shields: the assembly and function of the bacterial spore coat. Trends Microbiol. 2002b;10:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt, P. and Marquis, R.E. (1989) Spore thermoresistance mechanisms. In Regulation of Prokaryotic Development ed. Smith, I., Slepecky, R.A. and Setlow, P. pp. 43–63. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology.

- Henriques AO, Melsen LR, Moran CP., Jr Involvement of superoxide dismutase in spore coat assembly in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2285–2291. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2285-2291.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques AO, Moran CP., Jr Structure and assembly of the bacterial endospore coat. Methods. 2000;20:95–110. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullo MF, Moszer I, Danchin A, Martin-Verstraete I. CotA of Bacillus subtilis is a copper-dependent laccase. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5426–5430. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5426-5430.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns M, Harrington L, Titball RW, Leslie DL. Improved methods for the detection of Bacillus anthracis spores by the polymerase chain reaction. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Kumazawa Y, Miwa K, Yamanaka S. ɛ-(γ-Glutamyl)lysine cross-links of spore coat proteins and transglutaminase activity in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie SB, Israeli E, Lighthart B, Crowe J, Crowe L. Trehalose and sucrose protect both membranes and proteins in intact bacteria during drying. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3592–3597. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3592-3597.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi K, Higham JL, Coates D, Hamlyn PF. Molecular detection of anthrax spores on animal fibres. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;36:418–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2003.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loshon CA, Swerdlow BM, Setlow P. Bacillus megaterium spore protease: synthesis and processing of precursor forms during sporulation and germination. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:10838–10845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Ito N, Inoue T, Miyata S, Moriyama R. A spore-lytic enzyme released from Bacillus cereus spores during germination. Microbiology. 1994;140:1403–1410. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-6-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamu J, Ichikawa T, Kondo M. Studies on the bacterial spore coat. 6. Effect of alkali extraction on the spore of Bacillus thiaminolyticus. Microbios. 1977;18:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, W.L. and Setlow, P. (1990) Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In Molecular Biological Methods for Bacillus ed. Harwood, C.R. and Cutting, S.M. pp. 391–450. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Paidhungat M, Ragkousi K, Setlow P. Genetic requirements for induction of germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis by Ca2+-dipicolinate. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4886–4893. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4886-4893.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paidhungat M, Setlow B, Driks A, Setlow P. Characterization of spores of Bacillus subtilis which lack dipicolinic acid. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5505–5512. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.19.5505-5512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paidhungat M, Setlow B, Daniels WB, Hoover D, Papafragkou E, Setlow P. Mechanisms of induction of germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis by high pressure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3172–3175. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.3172-3175.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Role of Ger-proteins in nutrient and non-nutrient triggering of spore germination in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2513–2519. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2513-2519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popham DL, Helin J, Costello CE, Setlow P. Muramic acid lactam in peptidoglycan of Bacillus subtilis spores is required for spore outgrowth but not for spore dehydration or heat resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15405–15410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts M. Desiccation tolerance in prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:755–805. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.755-805.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priha O, Hallamaa K, Saarela M, Raaska L. Detection of Bacillus cereus group bacteria from cardboard and paper with real-time PCR. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;31:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s10295-004-0125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragkousi K, Eichenberger P, van Ooij C, Setlow P. Identification of a new gene essential for germination of Bacillus subtilis spores with Ca2+-dipicolinate. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2315–2329. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2315-2329.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragkousi K, Setlow P. Transglutaminase-mediated cross-linking of GerQ in the coats of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5567–5575. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5567-5575.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif TC, Johns M, Pillai SD, Carl M. Identification of capsule-forming Bacillus anthracis spores with the PCR and a novel dual-probe hybridization format. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1622–1625. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1622-1625.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rode LJ, Foster JW. Mechanical germination of bacterial spores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1960;46:118–128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.46.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotman Y, Fields ML. A modified reagent for dipicolinic acid analysis. Anal Biochem. 1967;22:168. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow B, Loshon CA, Genest PC, Cowan AE, Setlow C, Setlow P. Mechanisms of killing of spores of Bacillus subtilis by acid, alkali and ethanol. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:362–375. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow B, Melly E, Setlow P. Properties of spores of Bacillus subtilis blocked at an intermediate stage of spore germination. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4894–4899. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4894-4899.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow B, Setlow P. Role of DNA repair in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3486–3495. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3486-3495.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. Purification and properties of some unique low molecular weight basic proteins degraded during germination of Bacillus megaterium spores. J Biol Chem 250, 8168–8173. Setlow, P. (2003) Spore germination. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1975;6:550–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Blackman SA, Foster SJ. Autolysins of Bacillus subtilis: multiple enzymes with multiple functions. Microbiology. 2000;146:249–262. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu H, Watabe K. Assembly and genetics of spore protective structures. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:434–444. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuytack EY, Soons J, Poschet F, Michiels CW. Comparative study of pressure-and nutrient-induced germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:257–261. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.257-261.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Fitz-James PC, Aronson AI. Cloning and characterization of a cluster of genes encoding polypeptides present in the insoluble fraction of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3757–3766. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3757-3766.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]