Abstract

Research suggests that the development of emotional regulation in early childhood is interrelated with emotional understanding and language skills. Heuristic models are proposed on how these factors influence children’s emerging academic motivation and skills.

Recently there has been extensive discussion of the construct of emotion-related regulation, including its conceptualization, measurement, and relation to developmental outcomes. Definitions of the construct vary, but in general emotion-related regulation refers to processes used to manage and change if, when, and how one experiences emotions and emotion-related motivational and physiological states, and how emotions are expressed behaviorally. It is accomplished in diverse ways, notably through attentional and planning processes, inhibition or activation of behavior, and management of the external context.

Children’s emotion-related regulation (labeled herein regulation) is increasingly viewed as a core skill relevant to many aspects of their socio-emotional and cognitive functioning. A recent Academy of Science committee concluded that “the growth of self-regulation is a cornerstone of early childhood development that cuts across all domains of behavior” (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000, p. 3). Similarly, in a report funded by the National Institutes of Health concerning risk factors for academic and behavioral problems at the beginning of school, Huffman, Mehlinger, and Kerivan (2000) concluded that emotion regulation is critical for children’s competence.

Like the members of the National Academy of Science committee, we believe that regulatory skills, including those involved in managing emotions and their expression, are central to many aspects of children’s functioning. However, children’s emotion-related regulation and other early developing abilities likely influence one another while they are emerging. In this chapter, we discuss links between children’s regulation and two emerging skills: language and emotion understanding. In addition, we review findings on the relation of all three of these constructs to developmental outcomes that have infrequently been studied in relation to regulation: school readiness and academic skills. Finally, we propose a heuristic model for the interrelations among these variables, a model that has implications for research and for interventions with young people.

Emotion Regulation and Language

Kopp (1989, 1992) suggested that language skills provide important tools for understanding and regulating children’s emotions. Young children use language as a means to influence their environment. Specifically, children may use language in agentic self-managing talk, to communicate about social interactions, or to learn about appropriate ways to manage emotions. Consistent with this view, preschoolers’ language skills have been positively correlated with their ability to use distraction in a frustrating situation (Stansbury & Zimmerman, 1999). In addition, language impairment is associated with boys’ difficulty with emotion regulation (even for boys with age-appropriate abilities in other areas; Fujiki, Brinton, & Clarke, 2002). However, it is likely that emotion-related regulation and language affect one another, perhaps because better-regulated children elicit more complex language from others in their social environment (that is, adults may perceive well-regulated children as more attentive and advanced in their language skills). Consistent with the notion that language skills and regulation affect one another, infants’ regulation (as evidenced by factors such as attention span and attentional persistence) predicts their language skills eight to nine months later (Dixon & Smith, 2000).

Regulation and Emotion Understanding

Emotion-related regulation is associated with children’s language skills and also their emotion understanding. Emotion understanding involves being able to successfully attend to relevant emotion-laden language and information in one’s environment, identify one’s own and others’ experienced and expressed emotions, understand which emotions are appropriate given the circumstances, and recognize the causes and consequence of emotions. Regulation is probably integrally involved in the ability to focus on emotion-laden environmental cues in order to develop and fine-tune emotion understanding. Moreover, as suggested by Hoffman (1983), children who can avoid emotional overarousal likely learn more about emotion-related issues. Overaroused children are likely to attend to their own emotional experience and avoid an aversive situation, both of which are expected to reduce learning about others’ emotions. Consistent with these ideas, preschoolers’ level of regulation has predicted their understanding of emotion two years later (Schultz, Izard, Ackerman, & Youngstrom, 2001), and emotion understanding mediates the relations of regulation to adaptive social behavior (Izard, Schultz, Fine, Youngstrom, & Ackerman, 1999–2000; compare Lindsey & Colwell, 2003).

Conversely, emotion understanding may foster emotion regulation. Denham and Burton (in press) suggested that emotion understanding gives children a way to identify their internal feelings, which can then be made conscious. Such conscious emotional awareness allows children to immediately attach feelings to events, which can then facilitate successful and appropriate regulation (see also Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997). Because emotion understanding involves not only verbal labeling of internal states but also knowledge about emotion-related processes and their causes and consequences, children can use their emotion understanding to choose effective regulatory tactics when upset (Liew, Eisenberg, & Reiser, in press). Researchers have found that children who are able to understand emotions, communicate about them, and learn and remember how to manage them are better able to regulate themselves (Denham & Burton, in press; Kopp, 1992).

Academics and Emotion Regulation

Children’s emotion regulation also has been conceptually linked to their academic success (Raver, 2002; Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). For example, investigators have argued that emotion regulation (particularly attentional regulation and planning skills involved in executive attention) contributes directly to children’s school readiness and academic competence because children who have difficulty controlling their attention and behavior are likely to be challenged when attempting to learn and focus in the classroom (Blair, 2002). In addition, as is discussed later, emotion regulation may contribute to children’s motivation at school, which undoubtedly is linked to their academic performance.

Consistent with the view that regulatory processes affect academic performance, in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Childcare Research Network study (2003) attentional regulation at fifty-four months of age was positively related to high scores on achievement in reading and math, as well as linguistic ability (for example, auditory comprehension and expressive language). In another study, kindergartners’ behavioral tendencies to self-regulate attention and teachers’ ratings of second-graders’ self-regulation were significant predictors of reading achievement scores (Howse, Lange, Farran, & Boyles, 2003). Similarly, youths’ emotion regulation has been positively related to reading and math scores (Hill & Craft, 2003), teacher-rated academic behavior skills (Hill and Craft), young adolescents’ achievement scores, and teacher-rated academic competence, as well as with GPA when controlling for the effects of various cognitive variables (Gumora & Arsenio, 2002; Kurdek & Sinclair, 2000; Wills et al., 2001).

It is likely that the relation between children’s regulation and academic competence is partly mediated by their social competence because socially competent children tend to do better in school. In a series of studies, Eisenberg and colleagues (as well as numerous others) have found that emotion regulation is related to children’s social skills, popularity, and adjustment (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Eisenberg, Smith, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2004). These skills in turn may be related to children’s academic competence through their effect on children’s social relationships at school, which appear to influence their motivation and performance at school (Furrer & Skinner, 2003). Consistent with an association between children’s social and academic competence, Welsh, Parke, Widaman, and O’Neil (2001) found that young school children’s positive (prosocial) behavior, social competence, and academic competence (that is, math and language grades and reported work habits) were reciprocally related. Similarly, peer competence (for instance, peer acceptance) in the early school years has been negatively related to concurrent and subsequent deficits in work habits, math and language or reading, negative school attitude, school avoidance, and underachievement during the first year or two of schooling (Ladd, 2003; O’Neil et al., 1997). Thus, if regulation affects children’s social competence, then it likely also affects academic skills.

There is initial evidence that motivational factors such as liking school may at least partially mediate the relation between children’s regulation and their academic competence. Valiente, Lemery, and Castro (2004) found such a relation with concurrent measures of the three constructs. Also consistent with such a mediated relation, children’s reports of school liking and school participation have been positively related to classroom engagement, academic progress, and achievement (Buhs & Ladd, 2001; Ladd, Buhs, & Seid, 2000; Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Ladd, Kochenderfer, & Coleman, 1996).

The Model

To summarize thus far, the empirical literature, albeit limited in some respects, is consistent with the assertions that (1) there are relations among children’s regulation, language skills, and emotion understanding; and (2) these variables have implications for children’s academic motivation and performance. In Figure 12.1, we present a model of the proposed relations among young children’s emerging language, emotion knowledge and understanding, and regulation. As is indicated in the model, language abilities likely promote emotion understanding and emotion-related regulation; moreover, emotion understanding may partly mediate the relation of language skills to emotion-related regulation. In support of the latter relation, verbal abilities have been correlated with children’s emotion understanding (Cutting & Dunn, 1999; De Rosnay & Harris, 2002) and predict such understanding years later (Schultz et al., 2001). Children who are better able to communicate with others have more opportunity to learn about mental states, including emotion. In addition, as previously noted, children’s emotion-related regulation likely affects their emotion understanding.

Figure 12.1.

Hypothesized Interrelations of Children’s Language Skills, Emotion Knowledge, and Emotion-Related Regulation over Time

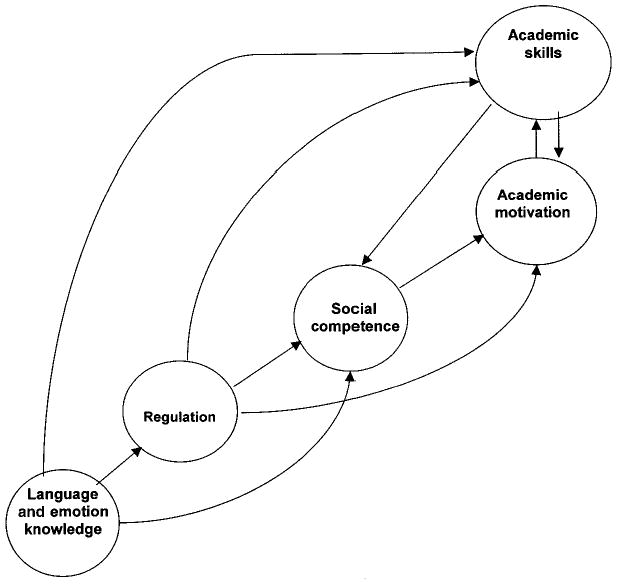

In Figure 12.2, we present a larger (yet simplified) heuristic model predicting academic outcomes. We suggest that children’s emerging emotion-related regulation—as influenced by their emerging language and emotion understanding and knowledge—affects their academic motivation and skills both directly and through its effect on their social competence (including peer acceptance and social skills, which foster positive relations with teachers). There may also be additive main effects of regulation, emotion understanding, and language on social competence and academic outcomes. Lindsey and Colwell (2003) found that preschoolers’ regulation and emotion understanding uniquely predicted their emotional competence with peers (they did not test for mediation). The complex relations among language skills, emotion knowledge, and emotion-related regulation that are depicted in Figure 12.1 are not fully depicted in Figure 12.2.

Figure 12.2.

Heuristic Model of Direct and Mediated Relations of Emotion-Related Regulation, Language, and Emotion Knowledge as Predictors of Children’s Social Competence, Academic Motivation, and Academic Skills

Research concerning the relation of regulation to other variables in the model has already been discussed, as has research on the relation of social competence to academic outcomes. In addition, in this model we suggest that language abilities and emotion knowledge contribute to social competence and academic motivation and skills. Children who understand emotions well would be expected to know when to display or mask them and to accurately interpret their own and others’ emotions—skills that appear to contribute to social competence. Fine, Izard, Mostow, Trentacosta, and Ackerman (2003) hypothesized that low emotion knowledge affects the quality of children’s social interaction, which in turn causes social alienation and emotions such as anxiety, fear, and sadness, which further undermine social interaction. Consistent with this view, young children’s emotion knowledge has been linked to their social competence (Denham & Burton, in press), and children’s verbal skills (vocabulary, receptive language) have been found to predict social skills (Izard et al., 2001; Mostow, Izard, Fine, & Trentacosta, 2002), adjustment (Ackerman, Brown, & Izard, 2003; Fine et al., 2003; Olson & Hoza, 1993), and academic skills (Izard et al., 2001). Further, in support of the model there is evidence that emotion knowledge mediates the relations between children’s verbal abilities and their social skills (and social skills did not predict emotion understanding; Mostow et al., 2002) and academic competence (Izard et al., 2001) years later. Thus, there is reason to expect language skills and emotion understanding to affect the development of social skills and adjustment and (on the basis of findings reviewed previously) for the latter to mediate relations of language skills and emotion knowledge with academic outcomes.

Developmental changes may affect the relations discussed in the model. For example, it is likely that language has a stronger effect on children’s emotion understanding and regulation in the first two or three years of life, when basic and emotion-related language skills are rapidly emerging. Emotion understanding and regulation likely continue to have moderate effects on one another (as well as on social and academic outcomes) during the preschool and school years because both are improving considerably during this period of life. As children age, other factors, such as children’s reputation with peers or peer history, may play an increasing role (along with regulation) in school liking and achievement. An important task for the future is to determine how age-related capacities and experiences affect the relations outlined in the models.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we briefly summarize relevant literature in an attempt to argue two major points: (1) emotion-related regulation is related to children’s emotion knowledge, language skills, and academic competencies; and (2) it is useful to consider all these constructs, as well as social competence, when examining the relation of regulatory capacities to emerging academic performance and motivation. In addition, our heuristic model highlights the importance of mediating processes and bidirectional causality. We believe that it is important to consider a variety of emerging skills if one pursues interest in issues such as school readiness and academic motivation. Models of the sort we have presented may be useful when planning intervention programs for improving school readiness and success. We believe that targeting children’s regulation and emotion understanding, as well as language skills, in intervention or prevention trials is likely to have a significant positive outcome for children’s social and academic competence.

References

- Ackerman BP, Brown E, Izard CE. Continuity and change in levels of externalizing behavior in school of children from economically disadvantaged families. Child Development. 2003;74:694–709. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhs E, Ladd GW. Peer rejection in kindergarten: Relational processes mediating academic and emotional outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:550–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting A, Dunn J. Theory of mind, emotion understanding, language, and family background: Individual differences and interrelations. Child Development. 1999;70:853–865. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham, S. A., & Burton, R. (in press). Social and emotional prevention and intervention programming for preschoolers. New York: Kluwer-Plenum.

- De Rosnay M, Harris PL. Individual differences in children’s understanding of emotion: The role of attachment and language. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:39–54. doi: 10.1080/14616730210123139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WE, Jr, Smith PH. Links between early temperament and language acquisition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N., Smith, C. L., Sadovsky, A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2004). Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 259–282). New York: Guilford Press.

- Fine SE, Izard C, Mostow A, Trentacosta CJ, Ackerman BP. First grade emotion knowledge as a predictor of fifth grade self-reported internalizing behaviors in children from economically disadvantaged families. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:331–342. doi: 10.1017/s095457940300018x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki M, Brinton B, Clarke D. Emotion regulation in children with specific language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2002;33:102–111. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2002/008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furrer C, Skinner E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1997). Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Gumora G, Arsenio WF. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and school performance in middle school children. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:395–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Craft SA. Parent-school involvement and school performance: Mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African American and Euro-American families. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M. L. (1983). Affective and cognitive processes in moral internalization. In E. T. Higgins, D. N. Ruble, & W. W. Hartup (Eds.), Social cognition and social development: a sociocultural perspective (pp. 236–274). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Howse RB, Lange G, Farran DC, Boyles CD. Motivation and self-regulation as predictors of achievement in economically disadvantaged young children. Journal of Experimental Education. 2003;71:151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, L. C., Mehlinger, S. L., & Kerivan, A. S. (2000). Risk factors for academic and behavioral problems at the beginning of school. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Izard CE, Fine S, Schultz D, Mostow A, Ackerman B, Youngstrom E. Emotion knowledge as a predictor of social behavior and academic competence in children at risk. Psychological Science. 2001;12:18–23. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Schultz D, Fine SE, Youngstrom E, Ackerman BP. Temperament, cognitive ability, emotion knowledge, and adaptive social behavior. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 1999–2000;19:305–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, C. (1992). Emotional distress and control in young children. In N. Eisenberg & R. A. Fabes (Eds.), Emotion and its regulation in early development. New Directions in Child Development, no. 55 (pp. 41–56). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kurdek LA, Sinclair RJ. Psychological, family, and peer predictors of academic outcomes in first- through fifth-grade children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G. W. (2003) Probing the adaptive significance of children’s behavior and relationships in the school context: A child by environment perspective. In R. Kail (Ed.), Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 31, 43–103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ladd GW, Buhs E, Seid M. Children’s initial sentiments about kindergarten: Is school liking an antecedent of early classroom participation and achievement? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:255–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Do relational risks and protective factors moderate the linkages between childhood aggression and early psychological and school adjustment? Child Development. 2001;72:1579–1601. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer BJ, Coleman CC. Friendship quality as a predictor of young children’s early school adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:1103–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew, J., Eisenberg, N., & Reiser, M. (in press). Preschoolers’ effortful control and negative emotionality, immediate reactions to disappointment, and quality of social functioning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindsey EW, Colwell MJ. Preschoolers’ emotional competence: Links to pretend and physical play. Child Study Journal. 2003;33:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mostow AJ, Izard CE, Fine S, Trentacosta C. Modeling emotional, cognitive, and behavioral predictors of peer acceptance. Child Development. 2002;73:1775–1787. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. Do children’s attention processes mediate the link between family predictors and school readiness? Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:581–593. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Hoza B. Preschool developmental antecedents of conduct problems in children beginning school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil R, Welsh M, Parke RD, Wang S, Strand C. A longitudinal assessment of the academic correlates of early peer acceptance and rejection. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:290–303. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC. Emotions matter: Making the case for the role of young children’s emotional development for early school readiness. Social Policy Report. 2002;16:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hemphill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13:142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Izard CE, Ackerman BP, Youngstrom EA. Emotion knowledge in economically disadvantaged children: Self-regulatory antecedents and relations to social difficulties and withdrawal. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:53–67. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [PubMed]

- Stansbury K, Zimmerman LK. Relations among child language skills, maternal socializations of emotion regulation, and child behavior problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1999;30:121–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1021954402840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente, C., Lemery, K. S., & Castro, K. (2004). Children’s effortful control and academic functioning: Mediation through school liking. Unpublished manuscript. Arizona State University, Tempe.

- Welsh M, Parke RD, Widaman K, O’Neil R. Linkages between children’s social and academic competence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;30:463–481. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary S, Filer M, Shinar O, Mariani J, Spera K. Temperament related to early-onset substance use: Test of a development model. Prevention Science. 2001;2:145–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1011558807062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]