Abstract

The recruitment of DNA polymerase α-primase (pol-prim) is a crucial step in the establishment of a functional replication complex in eukaryotic cells, but the mechanism of pol-prim loading and the composition of the eukaryotic primosome are poorly understood. In the model system for simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA replication in vitro, synthesis of RNA primers at the origin of replication requires only the viral tumor (T) antigen, replication protein A (RPA), pol-prim, and topoisomerase I. On RPA-coated single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), T antigen alone mediates priming by pol-prim, constituting a relatively simple primosome. T-antigen activities proposed to participate in its primosome function include DNA helicase and protein-protein interactions with RPA and pol-prim. To test the role of these activities of T antigen in mediating priming by pol-prim, three replication-defective T antigens with mutations in the ATPase or helicase domain have been characterized. All three mutant proteins interacted physically and functionally with RPA and pol-prim and bound ssDNA, and two of them displayed some helicase activity. However, only one of these, 5030, mediated primer synthesis and elongation by pol-prim on RPA-coated ssDNA. The results suggest that a novel activity, present in 5030 T antigen and absent in the other two mutants, is required for T-antigen primosome function.

Replication of the papovavirus simian virus 40 (SV40) minichromosome has been used extensively as a model to study the mechanism of eukaryotic DNA replication (see references 8 and 24 and references therein). The SV40 tumor (T) antigen is the sole viral protein required for SV40 DNA replication, making the virus dependent on the host cell replication machinery. Initially, T antigen recognizes and binds to two pairs of GAGGC pentanucleotides that are arranged in a head-to-head orientation within the SV40 origin of replication. In the presence of ATP, T-antigen monomers assemble cooperatively into a double hexamer on this sequence (2, 13, 34, 52, 56), causing a structural distortion in the flanking DNA (4, 5). The double hexamer undergoes a poorly understood remodeling event that is thought to transfer one hexamer to each of the template strands, where each hexamer tracks in a 3′ to 5′ polarity to unwind the parental duplex (47, 48, 50, 51, 66). A growing body of genetic, biochemical, and electron microscopic evidence suggests that the DNA is actually spooled through the double hexamer during unwinding and that interactions between the hexamers are required for unwinding (39, 50, 51, 64, 66). Other papovaviruses encode initiator proteins that are related in structure to SV40 T antigen and appear to carry out similar functions in viral DNA replication (10, 18, 22, 33, 42, 46, 53, 55).

Ten cellular factors have been identified that are sufficient to replicate SV40 DNA in vitro (reviewed in reference 59). Three of these, replication protein A (RPA), DNA polymerase α-primase (pol-prim), and topoisomerase I, are necessary, together with T antigen, for the initial stage of replication. RPA facilitates unwinding, stabilizes the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) template, and cooperates with T antigen and pol-prim to coordinate the assembly of the replication forks (reviewed in references 26 and 68). pol-prim initiates DNA synthesis on the leading- and lagging-strand templates by synthesizing short RNA primers that are elongated into RNA-DNA primers (1, 8, 19, 43, 59, 61). In a “polymerase switch” reaction, pol-prim is then displaced by RF-C, which loads PCNA and DNA polymerase δ to synthesize the leading and lagging strands (59, 72).

The role of T antigen in mediating priming by pol-prim during viral DNA replication is not well defined. Clearly, the DNA helicase activity of T antigen is essential to generate the template. Binding of T antigen to RPA and pol-prim is also likely to participate in primosome function (7, 11, 12, 14-17, 36, 40, 41, 62, 65), although this interpretation has not yet been confirmed with mutant T antigens that are specifically deficient in either of these activities. The origin DNA-binding domain of T antigen contains the major RPA-binding site (65), while the C-terminal half of T antigen contains the major binding site for pol-prim (14, 63) (Fig. 1). In solution, T antigen binds as a hexamer to pol-prim and makes contact with all four subunits of pol-prim (25, 62). Nevertheless, it remains unknown how the physical interactions among these proteins facilitate primer synthesis and elongation and whether they are sufficient for primosome function.

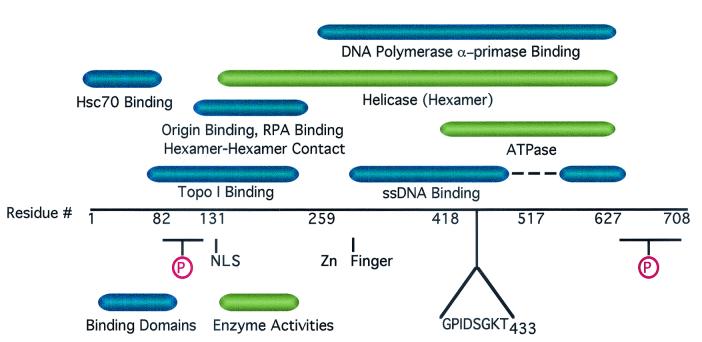

FIG. 1.

Functional domains of SV40 T antigen in viral DNA replication. The protein regions necessary and sufficient for each of the indicated biochemical activities are diagrammed by the colored bars above the linear map of the amino acid sequence. Approximate domain boundaries inferred from partial proteolysis studies are indicated by the residue numbers below the linear sequence. Other features of the protein are depicted below the linear sequence. NLS, nuclear localization signal; circled P, clusters of phosphorylated Ser/Thr residues; Zn finger, structurally essential putative zinc-binding motif. The Walker A motif sequence ends at Thr-433. The genetic and biochemical mapping data summarized in the figure are published elsewhere (see references 6, 8, 17, 20, 42, 54, 63-65, and 70 and references therein).

To begin to define how T antigen mediates priming by pol-prim in the presence of RPA, we investigated the properties of three replication-defective T antigens with mutations in the helicase or ATPase domain: 5030 (P417S), 5031 (D402N, V404 M, V413 M), and 5061 (G431 ALE) (9) (Fig. 1). The mutant T antigens were previously shown to bind to viral origin DNA and to have reduced helicase activity (9), suggesting possible defects in primosome functions. We report that the mutant proteins are unable to initiate SV40 DNA replication in vitro in a reaction with purified initiation proteins. All three mutants display reduced ssDNA-binding activity but interact physically and functionally with RPA and pol-prim. Interestingly, the 5030 mutant retains the ability to stimulate priming and elongation on RPA-coated ssDNA, while the other two mutants have little or no activity in this assay. The results suggest that the 5030 mutant T antigen harbors a novel activity that is absent in the other two mutant proteins and is required for primosome activity of T antigen. Possible models for how T antigen may promote priming by pol-prim on RPA-coated DNA are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein purification.

Recombinant baculoviruses for mutant T-antigen expression were kindly provided by J. M. Pipas (9). T antigen was purified by immunoaffinity chromatography from extracts of Hi-5 insect cells infected with recombinant baculovirus for 48 h. Briefly, infected cells (5 × 108) were resuspended in 4 volumes of lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and transferred to a cold Dounce homogenizer. Cells were lysed with several strokes of the homogenizer pestle and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The clarified lysate was added to Pab101-Sepharose beads (14) that had been preequilibrated with lysis buffer and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with mixing by end-over-end rotation. The beads were collected by centrifugation and washed four times with 10 volumes of NET buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5% NP-40) and twice with 10 volumes of PIPES buffer {10 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)]-KOH [pH 7.0], 5 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol}. The protein was then eluted from the column in several fractions of 0.5 volume with elution buffer (20 mM triethylamine [pH 10.8], 20% glycerol). Fractions were neutralized by addition of 50 mM PIPES-KOH (pH 7.0) and frozen at −80°C. The yield of wild-type (WT) T antigen was 2.5 mg of purified protein.

Human p68 with an amino-terminal His tag (R. D. Ott, C. Rehfuess, and E. Fanning, unpublished data) was purified from Hi-5 cells (5 × 108) infected with a recombinant baculovirus for 48 h. The infected cells were resuspended in 4 volumes of lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The suspension was transferred to a cold Dounce homogenizer, and the cells were lysed by several strokes of the pestle. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was applied to DEAE-Sephacel (5-ml packed volume) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) previously equilibrated with binding buffer (40 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.8], 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with end-over-end rotation. The column was washed with 20 volumes of DEAE wash buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.8], 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), and proteins were eluted with elution buffer (250 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.8], 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) in 10 fractions of 0.5 column volumes each. Fractions containing protein were pooled and applied to 0.5 ml of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose previously equilibrated with 20 volumes of binding buffer (250 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.8], 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 35 mM imidazole [pH 7.9]). The proteins were incubated with the resin for 1.5 h at 4°C with end-over-end rotation. The column was washed with 20 volumes of wash buffer (250 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.8], 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM imidazole [pH 7.9]). Bound proteins were then eluted with elution buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.0], 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 mM imidazole [pH 7.5]) in 10 fractions of 0.5 column volume each. Fractions containing protein were dialyzed against dialysis buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.0], 1 mM EDTA, 3.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50% glycerol) for 15 h at 4°C before being frozen in aliquots at −80°C.

Recombinant human DNA pol-prim was purified by immunoaffinity chromatography as described previously (58), and recombinant human RPA was also expressed and purified as described earlier (23). Escherichia coli ssDNA-binding protein (SSB) was purified as described previously (32). Calf thymus topoisomerase I was purified as described by Moarefi et al. (39).

SV40 initiation assay.

Reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 250 ng of pUC-HS plasmid DNA containing the complete SV40 origin (45), 600 ng of RPA, 300 ng of topoisomerase I, 200 ng of pol-prim, 250 to 1,000 ng of T antigen in initiation buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 7 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 0.2 mM GTP, 0.2 mM UTP, 0.01 mM CTP, 40 mM creatine phosphate, 0.04 mg of creatine kinase/ml) supplemented with 20 μCi of [α-32P]CTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Dupont NEN, Boston, Mass.). Reactions were assembled at 4°C and incubated at 37°C for 90 min. Reaction products were precipitated with 2% NaClO4 in acetone. The washed and dried products were redissolved in loading buffer (45% formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.08% xylene cyanol FF, 0.08% bromophenol blue) at 65°C for 10 min and then resolved by denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) for 3 to 4 h at 500 V. The reaction products were visualized by autoradiography.

Primer synthesis and elongation in the presence of RPA.

Reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 25 ng of M13 ssDNA were preincubated with 250 to 1,000 ng of RPA in elongation buffer (30 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 7 mM magnesium acetate, 0.01 mM ZnCl2, 1 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 0.2 mM GTP, 0.2 mM UTP, 0.2 mM CTP, 0.02 mM dATP, 0.1 mM dGTP, 0.1 mM dTTP, 0.1 mM dCTP, 40 mM creatine phosphate, 0.04 mg of creatine kinase/ml). The reaction mixture was supplemented with 3 μCi of [α-32P]dATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.), and 1.5 U of pol-prim and 300 to 600 ng of T antigen were added where indicated in the figure. Reactions were assembled at 4°C, incubated at 37°C for 45 min, and then digested with 0.1 mg of proteinase K/ml in the presence of 1% SDS and 1 mM EDTA for 30 min at 37°C. Radiolabeled DNA was purified over Sephadex G-50 columns (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). The products were precipitated with 10 volumes of cold acetone and resuspended in loading buffer (60 mM NaOH, 2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 20% Ficoll, 0.10% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.10% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol). The reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels in running buffer (30 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA) for 2 h at 50 V and visualized by autoradiography. In addition, a sample of the radiolabeled products from each reaction was acid precipitated and analyzed by scintillation counting.

Stimulation of priming and elongation by T antigen.

Reactions (20 μl) containing 25 ng of M13 ssDNA, 0.1 U of pol-prim, and 250 ng of T antigen were incubated in elongation buffer supplemented with 3 μCi of [α-32P]dATP. Reactions were assembled at 4°C, incubated at 37°C for 45 min, and then digested with 0.1 mg of proteinase K/ml in the presence of 1% SDS and 1 mM EDTA for 30 min at 37°C. Reaction products were purified and analyzed as described above.

Far-Western blots.

Proteins were incubated in loading buffer (2.5% SDS, 2.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 100 mM DTT, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, and 0.025% pyronin Y) for 5 min at room temperature and separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels (0.5 mm thick). The gel was then soaked in refolding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 20% glycerol) for 1 h at room temperature. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose in transfer buffer (10 mM NaHCO3, 3 mM Na2CO3) at 150 mA for 2 h. Nonspecific sites on the nitrocellulose were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk solution in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl) for 30 min. The blots were incubated with the soluble T antigen at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h and then washed 10 times with TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20). The blot was incubated with polyclonal anti-T antiserum (1:10,000) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) in succession with washing between antibodies, and bound antibody was detected by using a Supersignal chemiluminescence kit as directed by the manufacturer (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

T-antigen binding to RPA or p68 subunit.

A total of 3 μg of T antigen was bound to Pab101 antibody (21) covalently coupled to Sepharose beads. The beads were incubated with 5 μg of purified RPA (or 4 μg of purified p68) in binding buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.8], 10 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2), containing 2% nonfat dry milk for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were washed once with binding buffer and four times with wash buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.8], 75 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.25% inositol, 0.01% NP-40). The beads were resuspended in 30 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then detected by immunoblotting. Alternatively, T-antigen-bound beads were incubated with RPA in TBS (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl) containing 2% nonfat milk for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were washed once with TBS and four times with TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20). The 70-kDa subunit of RPA was detected by immunoblotting with the monoclonal antibody 70C (27). The p68 subunit was detected with the monoclonal antibody 9D5 (a generous gift from David Lane, Dundee, United Kingdom) as described previously (57).

Native gel electrophoresis of RPA-ssDNA complexes.

A total of 9 pmol of RPA or 19 pmol of SSB was incubated with 3 pmol of 5′ 32P-end-labeled ssDNA (dT30) in binding buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 40 mM creatine phosphate, 7 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 10 μM ZnCl2) for 10 min at 25°C to form a saturated complex. Then 18 pmol of T antigen was added, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Reaction products were resuspended in sample buffer (0.05% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.05% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol, 2.5% [wt/vol] Ficoll 400) and loaded on 7.5% native polyacrylamide gels. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by electrophoresis in Tris-borate buffer (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 10 μM ZnCl2) for 2 h at 120 V. The gel was dried and complexes were detected by autoradiography.

ssDNA-binding assays. (i) Mobility shift assay.

A total of 10 pmol of T antigen was incubated with 3 pmol of 5′ 32P-end-labeled ssDNA (dT30) in binding buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 40 mM creatine phosphate, 7 mM MgCl2, 10 μM ZnCl2) in the presence or absence of 4 mM ATP for 30 min at 37°C. Reactions were resuspended in sample buffer (0.05% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.05% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol, 2.5% [wt/vol] Ficoll 400) and loaded on 7.5% native polyacrylamide gels. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by electrophoresis in Tris-borate buffer (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 10 μM ZnCl2) for 2 h at 120 V. The gel was dried, and the complexes were detected by autoradiography.

(ii) Filter-binding assay.

For the filter-binding assays, increasing amounts of T antigen were incubated with a 5′ 32P-end-labeled 17-mer oligonucleotide annealed to M13 DNA or with a 5′ 32P-end-labeled ssDNA (dT30) in binding buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 40 mM creatine phosphate, 7 mM MgCl2, 4 mM [γ-S]ATP, 10 μM ZnCl2) for 20 min at 37°C. Reactions were spotted on alkali-treated nitrocellulose filters (35). The filters were washed five times with wash buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 7 mM MgCl2), dried, and analyzed by scintillation counting.

RESULTS

The mutant T antigens 5030, 5031, and 5061 are defective in initiation of SV40 DNA replication.

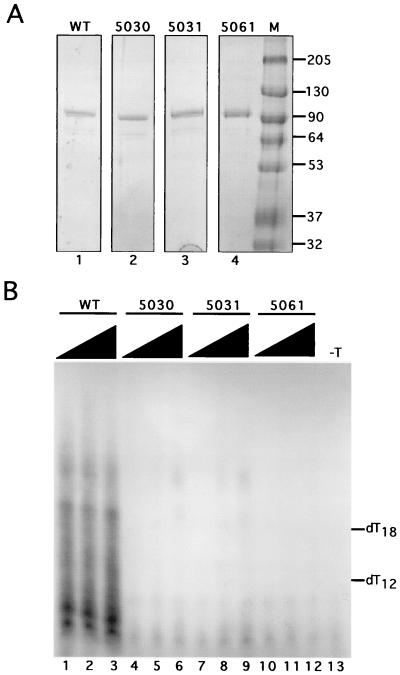

The three mutant T antigens—5030, 5031, and 5061—were previously reported to be unable to replicate SV40 DNA in monkey cells in culture or in human cell extracts in a cell-free system (9). Biochemical characterization of the mutant proteins indicated that they could recognize their binding sites in the viral origin of DNA replication but failed to carry out one or more subsequent steps in the replication process. To directly assay the activity of the mutant proteins in initiation of SV40 DNA replication, recombinant WT T antigen and the mutant T antigens 5030, 5031, and 5061 were purified by immunoaffinity chromatography. The purified mutant proteins were obtained in yields similar to those of WT T antigen and migrated with mobilities similar to that of the WT protein (Fig. 2A). The activity of the mutant T antigens in the initiation of replication at the SV40 origin of replication was tested in reactions containing purified supercoiled origin DNA, RPA, pol-prim, topoisomerase I, ribonucleoside triphosphates, and increasing amounts of T antigen. Radiolabeled RNA primers of the expected length were synthesized in reactions containing the WT protein (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 3), but little or no initiation was detected in reactions containing the three mutant T antigens (lanes 4 to 12) or in the control reaction lacking T antigen (lane 13). These results are consistent with published work (9) and demonstrate that the mutant proteins are deficient in one or more activities required for primer synthesis during initiation at the viral origin of replication. In addition to their reduced helicase activity (9), the mutant T antigens could also have defects in other activities thought to participate in primosome function, such as ssDNA binding and protein-protein interactions with RPA and pol-prim.

FIG. 2.

Mutant SV40 T antigens fail to initiate SV40 DNA replication in the presence of purified initiation proteins. (A) Purified recombinant WT (lane 1), 5030 (lane 2), 5031 (lane 3), and 5061 (lane 4) T antigens were analyzed by SDS-10% PAGE and Coomassie staining. Lane M, marker proteins of known molecular masses (indicated in kilodaltons at the right). (B) Initiation of SV40 replication was assayed in reactions containing SV40 origin DNA, topoisomerase I, RPA, pol-prim, and 250, 500, or 1000 ng of WT or mutant SV40 large T antigen as indicated (lanes 1 to 12). Primers synthesized by pol-prim were visualized by denaturing 20% PAGE and autoradiography. Products synthesized in a control reaction without T antigen are shown (lane 13). The positions of end-labeled oligonucleotides dT12-18 used as markers are indicated.

The 5030, 5031, and 5061 mutant T antigens have reduced ssDNA-binding activity.

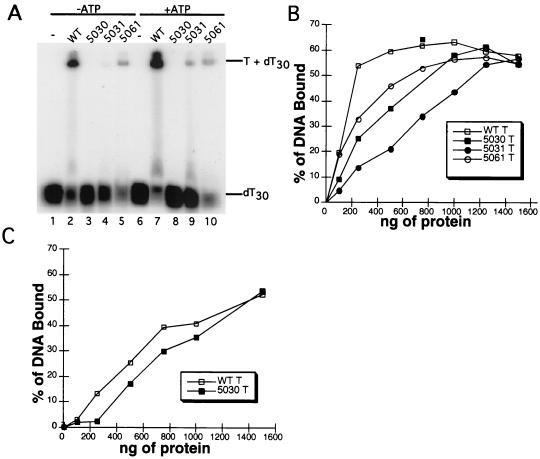

The ssDNA-binding domain of T antigen has recently been mapped to a region within residues 259 to 627 (69, 70) that encompasses the 5030, 5031, and 5061 mutations (Fig. 1). The low ATPase activity exhibited by the 5030 and 5031 mutant T antigens was not stimulated by ssDNA (9), suggesting a defect in ssDNA binding. The ability of the mutant T antigens to bind to radiolabeled ssDNA in the presence or absence of ATP was examined in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Fig. 3A). The WT protein bound efficiently to ssDNA, and binding was enhanced in the presence of ATP (lanes 2 and 7). Stable ssDNA binding was not detected with the 5030 mutant (lanes 3 and 8). Binding of the 5031 T antigen without ATP was barely detectable but was stimulated by ATP (lanes 4 and 9). The 5061 T antigen bound weakly to ssDNA and was not affected by ATP (lanes 5 and 10). Thus, the mutations in the 5030, 5031, and 5061 proteins appear to strongly reduce their ssDNA-binding activity.

FIG. 3.

ssDNA-binding activity of WT and mutant T antigens. (A) ssDNA-binding activity was tested in the presence (lanes 1 to 5) or absence of ATP (lanes 6 to 10). Reactions containing 10 pmol of WT (lanes 2 and 7), 5030 (lanes 3 and 8), 5031 (lanes 4 and 9) or 5061 (lanes 5 and 10) T antigen, as indicated, were incubated with end-labeled ssDNA in binding buffer for 30 min at 37°C. Protein-DNA complexes were visualized by native gel electrophoresis and autoradiography (overexposed here to show traces of bound DNA in lane 9). Lanes 1 and 6 show the products of a control reaction without T antigen. (B and C) Increasing amounts of T antigen were incubated with a partially duplex DNA template (B) or dT30 (C) for 20 min at 37°C. Protein-DNA complexes were immobilized on nitrocellulose filters, and bound DNA was quantitated by scintillation counting. The background was subtracted, and the percentage of input DNA bound was plotted as a function of input protein mass.

However, it is possible that the weak ssDNA binding observed in the mobility shift assay reflects either an activity too labile to withstand the mobility shift assay or a low affinity for this particular DNA. To distinguish between these alternatives, filter-binding assays were used to test the ssDNA-binding activity of the mutant T antigens in the presence of an ATP analog. Two DNA ligands were used: a partial duplex helicase substrate (Fig. 3B) or oligodeoxythymidylate as in Fig. 3A (Fig. 3C). Binding of the mutant T antigens to both DNA ligands in the filter-binding assay was more easily detectable than in the mobility shift assay but remained weaker than that of the WT protein (Fig. 3B and C). The results confirm that all three mutant proteins bind to ssDNA with reduced activity.

The 5030, 5031, and 5061 mutant T antigens interact physically and functionally with human RPA.

Previous studies suggested that specific physical interactions of T antigen with human RPA may be required for primosome function, but mutant T antigens specifically defective in RPA interactions have not been reported (12, 36, 65). The ability of the mutant T antigens to bind to RPA was assayed by coimmunoprecipitation. Equal amounts of the WT and mutant proteins immobilized on an immunoaffinity resin were incubated with purified RPA in a buffer comparable to that used for replication assays (Fig. 4A). Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody against the RPA70 subunit or against T antigen. The results show that all three mutant proteins could bind to RPA in replication buffer (Fig. 4A, upper panel, lanes 2 to 4), but they bound less RPA than WT T antigen (lane 1). The control immunoblots demonstrate that equal amounts of T antigen were present in each immunoprecipitation reaction (Fig. 4A, lower panel), confirming that the mutant T antigens bind to RPA, albeit more weakly than the WT protein.

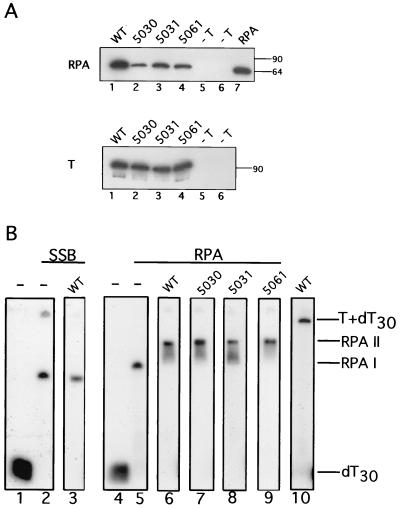

FIG. 4.

T-antigen interactions with RPA. (A) WT and the indicated mutant T antigens (3 μg of each) prebound to Pab101-Sepharose beads were incubated with purified RPA (5 μg) in a buffer analogous to that used in replication assays. Negative controls were carried out without T antigen. The beads were washed in the corresponding buffer, and immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE. RPA was detected by immunoblotting with the monoclonal antibody 70C (upper panel). A sample of purified RPA run as a blotting control is shown in lane 7. The amount of T antigen in each reaction was verified by immunoblotting with the monoclonal antibody Pab101 (lower panel). The electrophoretic mobilities of marker proteins are noted at the right (in kilodaltons). (B) Reactions containing SSB-saturated ssDNA (lanes 2 and 3) or RPA-saturated ssDNA (lanes 5 to 9) were incubated with WT T antigen (lanes 3 and 6), 5030 (lane 7), 5031 (lane 8), and 5061 (lane 9) for 15 min at 37°C. Protein-DNA complexes were visualized by native gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. WT T antigen incubated with ssDNA in the absence of RPA formed a T-ssDNA complex as indicated (lane 10). Control reactions lacking protein are shown in lanes 1 and 4.

The functional interactions of the mutant T antigens with RPA bound to ssDNA were examined in a mobility shift assay (Fig. 4B). A 30-mer oligodeoxythymidylate was incubated with a saturating amount of either bacterial SSB or recombinant human RPA, resulting in an SSB- or RPA-ssDNA complex (RPAI) (lanes 2 and 5). When WT T antigen was added to the RPA-saturated ssDNA, a more slowly migrating DNA-protein complex (RPAII) was generated (lane 6). The addition of WT T antigen to the SSB-saturated ssDNA had no effect on the electrophoretic mobility of the complex (lane 3), suggesting that the physical interactions of T antigen with RPA, rather than ssDNA binding of the T antigen, play a role in generating the RPAII complex. Consistent with this notion, a T antigen-ssDNA complex migrated even more slowly than RPAII (lane 10). Moreover, results to be published elsewhere demonstrate that the RPAI and RPAII complexes contain RPA but not T antigen (R. D. Ott and E. Fanning, unpublished data), implying that the interaction of T antigen with RPA must be labile under electrophoretic conditions. When the mutant T antigens were added to RPA-saturated ssDNA, they also generated the slowly migrating RPAII complex (Fig. 4B, lanes 7 to 9), indicating that they were competent to interact functionally with RPA-ssDNA complexes.

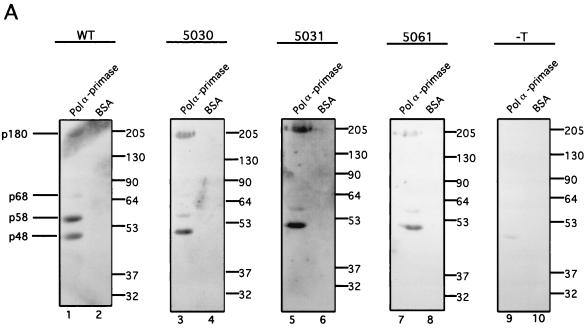

The 5030, 5031, and 5061 mutant T antigens interact physically with human polymerase α-primase.

Considerable evidence suggests that primosome function in SV40 DNA replication requires physical contacts of T antigen with human pol-prim (12, 40, 41, 45, 49, 62, 65, 67). To test whether the mutant proteins interact physically with human pol-prim, binding of the WT and mutant proteins to pol-prim was initially tested in a far-Western blot (Fig. 5A). Blots containing the four-subunit complex of human pol-prim, and an equimolar amount of purified bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a negative control, were incubated with soluble WT or mutant T antigens. T-antigen binding to the subunits of pol-prim was detected by immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-T antibodies (Fig. 5A). The WT protein bound to three of the four pol-prim subunits, p180, p58, and p48 (Fig. 5A, lane 1), but not to the BSA control (lane 2). In a control reaction, only background staining was detected with a pol-prim blot that had not been incubated with T antigen (lane 9), verifying the specificity of the far-Western detection. The 5030 and 5031 mutant proteins bound specifically to the p180 and p48 subunits, but p58 binding was decreased relative to that with p180 and p48 in the same lane (compare lanes 3 and 5 with lane 1). The 5061 T antigen bound to p48, but binding to both p180 and p58 was diminished relative to that with p48 in the same lane (compare lane 7 with lanes 1, 3, and 5). None of the mutant T antigens bound to BSA (lanes 4, 6, and 8).

FIG. 5.

T-antigen binding to DNA polymerase α-primase. (A) WT and the indicated mutant T antigens were tested for the ability to interact with human pol-prim in a far-Western blot. First, 5 μg of purified pol-prim (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9) and an equivalent molar amount of BSA (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Then, the blots were incubated with purified T antigen at 10 μg/ml (lanes 1 to 8) or as a control without T antigen (lanes 9 to 10). Bound T antigen was detected with rabbit polyclonal anti-T antiserum and goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. (The p180 band in lane 1 was partially obscured by a background smear of unknown origin.) The electrophoretic mobility of the pol-prim subunits is noted on the left, and the mobility of protein markers (in kilodaltons) is noted on the right. (B) A total of 3 μg of the indicated T antigen bound to Pab101-Sepharose beads was incubated with 4 μg of purified p68. The beads were washed, and immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE (lanes 1 to 4). Control reactions were performed without T antigen (lane 5). The presence of p68 was detected by immunoblotting with the monoclonal antibody 9D5 (upper panel). The electrophoretic mobility of purified p68 is noted on the left, and the mobility of protein markers (in kilodaltons) is noted on the right. The amount of T antigen in each reaction was tested by immunoblotting with the monoclonal antibody Pab101 (lower panel).

Since binding of T antigen to the p68 subunit was not detected in the far-Western assay shown in Fig. 5A, it was tested by immunoprecipitation. Equal amounts of WT and mutant T antigens immobilized on an immunoaffinity resin were incubated with purified p68 in a buffer comparable to that used for the priming and elongation assays. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by denaturing PAGE, and p68 was detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 5B, upper panel). All three mutant T antigens bound to p68, although the signal was weaker with 5031 T antigen (lane 3) than the others (lanes 2 and 4). Immunoblotting with antibody against T antigen as a control revealed that the amounts of T antigen (Fig. 5B, lower panel) correlated well with the amounts of bound p68 (Fig. 5B, upper panel). The results confirm that all three mutant T antigens bound to p68 as efficiently as the WT protein.

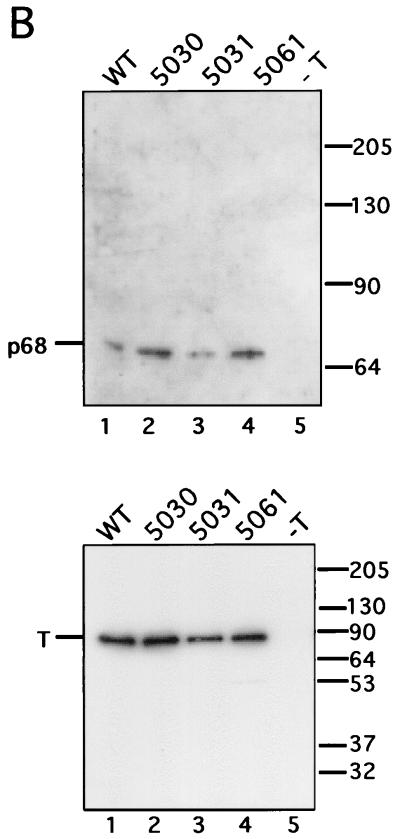

The 5030, 5031, and 5061 mutant T antigens retain the ability to stimulate the activity of human DNA polymerase α-primase.

Previous studies indicated that T antigen stimulates the catalytic activities of pol-prim when the amount of the enzyme is limiting. This stimulation depends upon physical interactions between T antigen and pol-prim but may require additional activities of T antigen (11, 12, 28, 36, 41, 45). The WT and mutant T antigens were tested for the ability to stimulate priming and elongation by pol-prim on ssDNA in the absence of RPA (Fig. 6). Without T antigen, the small amount of pol-prim synthesized only traces of products (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7), but its activity was strongly stimulated in the presence of WT and all three mutant T antigens (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Quantitation of the results by densitometry confirmed that the 5030, 5031, and 5061 mutant T antigens stimulated pol-prim activity 2.7-, 3.5-, and 4.4-fold, respectively, comparable to 3.5-fold stimulation observed with WT T antigen. Control reactions without pol-prim showed no products (lanes 9 to 12). These results indicate that all three mutant proteins interact functionally with pol-prim to stimulate priming and elongation.

FIG. 6.

Stimulation of DNA polymerase α-primase by T antigen. Primer synthesis and elongation activity of limiting amounts of DNA pol-prim were assayed on ssDNA template in the absence (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or the presence of 250 ng of WT (lane 2), 5030 (lane 4), 5031 (lane 6), and 5061 (lane 8) T antigens. Control reactions were carried out without pol-prim (lanes 9 to 12). Reaction products were resolved by alkaline electrophoresis, visualized by autoradiography, and quantitated by densitometry. The electrophoretic mobility of end-labeled marker DNA fragments of the indicated lengths in nucleotides is shown at the right.

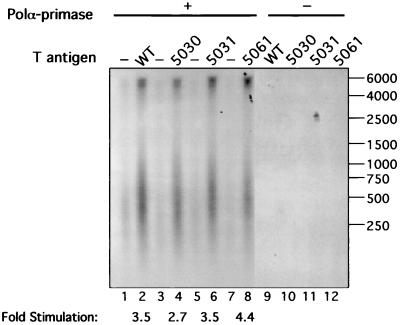

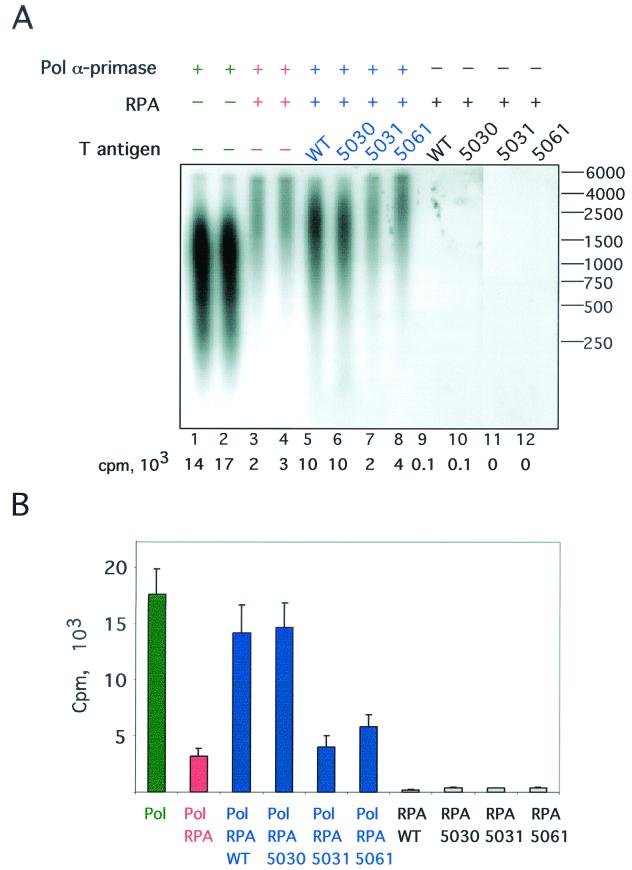

The 5030 T antigen relieves RPA-mediated inhibition of priming and elongation on an RPA-coated ssDNA template, but the 5031 and 5061 proteins do not.

The mutant T antigens appear to undergo physical and functional interactions with RPA and pol-prim, raising the question of whether their defects in DNA unwinding and helicase activity (9) may be the major or only reason for their inability to initiate SV40 DNA replication. If defective DNA unwinding were solely responsible for the observed initiation defects, the mutant proteins might still be able to promote primer synthesis and elongation on an RPA-coated ssDNA template, since unwinding would not be necessary.

To test this possibility, the mutant T antigens were assayed for the ability to relieve the RPA-mediated inhibition of primer synthesis and elongation (12, 36). The complete reaction mixture contained ssDNA, RPA, pol-prim, T antigen, unlabeled ribo- and deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates, and a radiolabeled deoxyriboadenosine triphosphate. Thus, radiolabeled reaction products would be detected only if unlabeled RNA primers were synthesized and then elongated with the radiolabeled deoxyribonucleotide. Reaction products synthesized by pol-prim in the absence of the other proteins were easily detectable (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 to 2). Preincubation of the template with purified RPA inhibited primer synthesis and elongation 7- to 10-fold as expected (lanes 3 to 4), but the length of the products was somewhat greater than in the absence of RPA, in agreement with previous reports (68). Addition of purified WT T antigen to the reaction partially relieved the inhibition (lane 5), and the length of the products was intermediate. An equal amount of the 5030 mutant T antigen also relieved the RPA-mediated inhibition of primer synthesis and elongation (lane 6). However, inhibition of priming and elongation was not significantly relieved by the 5031 (lane 7) or 5061 (lane 8) T antigen. When pol-prim was omitted in control reactions, essentially no reaction products were detected (lanes 9 to 12). Quantitation of data from three independent experiments confirmed these results (Fig. 7B). The specificity of this assay was confirmed in another control by using purified bacterial SSB to inhibit primer synthesis. The addition of WT T antigen to reactions containing SSB-coated DNA did not relieve the inhibition of primer synthesis and elongation (data not shown), in agreement with previous work (36). The results demonstrate that the 5030 T antigen can promote priming and elongation on RPA-coated ssDNA, while the other two mutants cannot. The data are consistent with the idea that the DNA unwinding defect of the 5030 T antigen may be primarily responsible for its replication deficiency.

FIG. 7.

Stimulation of DNA polymerase α-primase on RPA-coated ssDNA by T antigen. The ability of T antigen to stimulate primer synthesis and elongation by DNA pol-prim on RPA-coated ssDNA was tested. (A) Reactions were performed in duplicate and contained 300 ng of the indicated T antigen and 750 ng of RPA, pol-prim, ribo- and deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates, and radiolabeled dATP. The reaction products were resolved by alkaline gel electrophoresis and then visualized by autoradiography. Reaction products made in the absence of RPA (lanes 1 and 2) or pol-prim (lanes 9 to 12) are shown. The radioactivity (in counts per minute [cpm]) incorporated in each reaction is shown below each lane. The mobility of end-labeled marker DNA fragments of the indicated lengths in nucleotides is shown at the right. (B) Data from three independent experiments were quantitated, and the mean is plotted for each reaction. The brackets indicate the standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

Biochemical nature of the replication defects in 5030, 5031, and 5061 T antigens.

A number of biochemical activities of the three replication-defective mutant T antigens used in this study were previously characterized, including SV40 origin DNA binding, double-hexamer formation on the origin, origin distortion, origin unwinding, hexamer assembly, helicase activity, and DNA replication in vitro (9). All three mutant proteins were able to recognize and bind to SV40 origin DNA, but defects in their nucleotide binding and hydrolysis properties appeared to abrogate their ability to replicate viral DNA. The 5061 protein was unable to bind to ATP, causing the loss of hexamer assembly, origin distortion and unwinding, and helicase activities. The 5030 mutant assembled into double hexamers on origin DNA and had significant helicase activity but failed to coordinate these properties properly to distort and unwind the origin. The 5031 mutant exhibited all of these activities at a level at least 25% that of the WT protein and yet lacked replication activity. The properties of these mutants could also be consistent with defects in T-antigen primosome functions beyond its helicase activity.

To explore the primosome functions of these mutant T antigens, we tested their ability to initiate SV40 DNA replication, in a reaction containing purified proteins, to bind to ssDNA, to interact physically and functionally with pol-prim and RPA, and to mediate priming and elongation on RPA-coated ssDNA. The results confirm that all three mutant T antigens were unable to initiate SV40 DNA replication in vitro, a finding consistent with the previously reported unwinding defects and with possible additional defects in primosome function. All three mutant T antigens displayed defects in binding to ssDNA, RPA, and pol-prim compared to the WT protein (Fig. 3, 4A, and 5). The weak RPA binding of the mutant T antigens was somewhat unexpected, since the major RPA-binding domain of T antigen was mapped to an N-terminal region of T antigen (Fig. 1) (65). It is possible that the C terminus of T antigen may make additional weaker contacts with RPA that are abolished by the mutations. Alternatively, the reduced RPA binding could arise through conformation changes in the N terminus of T antigen that were induced by the mutations in the C terminus. Additional work will be needed to distinguish among these alternatives. In any case, the reduced physical interactions of the mutants with ssDNA, RPA, and pol-prim were sufficient to support their functional interactions with RPA-ssDNA (Fig. 4B) and with pol-prim (Fig. 6) at a level similar to that of the WT protein.

SV40 T-antigen requirements for primosome function on RPA-coated ssDNA.

Despite its multiple biochemical defects, the 5030 mutant protein was able to stimulate primer synthesis and elongation by pol-prim on RPA-coated ssDNA with an activity comparable to that of WT T antigen (Fig. 7). In contrast, the 5031 mutant protein, with similar biochemical defects, did not promote priming and elongation on RPA-coated ssDNA. The results suggest that 5030 T antigen may possess an undefined activity that is present in WT T antigen and missing in the 5031 protein. This putative activity could be responsible for the ability of 5030 T antigen to mediate priming. What might this activity be? One candidate is the ability of T antigen to bind efficiently to ssDNA or partial duplex DNA, since the activity of the 5031 protein appears to be weaker than those of 5030, 5061, and WT proteins (Fig. 3). A requirement for ssDNA binding by proteins that mediate loading of another protein onto SSB-coated ssDNA has been documented in other systems. For example, bacteriophage T4 encodes a protein, gp59, that mediates loading of the gp41 helicase onto ssDNA saturated with the phage ssDNA-binding protein gp32 (3). The requirements for gp59-mediated loading of gp41 onto gp32-coated ssDNA include gp59 binding to gp32, to gp41, and to ssDNA (31, 71). Similarly, E. coli DnaC-mediated loading of DnaB helicase onto ssDNA depends upon DnaC binding to DnaB and to ssDNA (29, 44). Binding of the mediator protein to ssDNA in these examples is an intermediate step in exchanging the ssDNA-binding protein for the gp41 or DnaB protein.

Another candidate for this unidentified activity is the previously reported ability of T antigen to bind to the C terminus of the 32-kDa subunit of RPA (30, 60), which was reported to be required for SV40 replication under some conditions (30). Binding of the C terminus of RPA32 to several DNA repair and recombination proteins is thought to be involved in ordering the assembly of the participating proteins in several repair and recombination pathways (37, 38). Unfortunately, although T-antigen binding to the 70-kDa RPA subunit is easily detectable, the attempts by us and others to demonstrate the binding of WT T antigen to RPA32 by using purified proteins have so far been unsuccessful (7; Ott and Fanning, unpublished).

A third possibility is that the biochemical activities common to 5030 and 5031 T antigens are in fact sufficient to mediate priming by pol-prim on RPA-coated ssDNA but that 5030 and 5031 T antigens differ in their ability to functionally coordinate an RPA-pol-prim exchange. Based on the electron microscopic structure of the T-antigen double hexamer and on genetic evidence, the amino-terminal parts of the two hexamers are oriented head to head, whereas the two C-terminal propeller-like parts of the hexamers reside at opposite ends of the complex (56, 64). Biochemical and electron microscopic evidence suggests that this overall orientation is retained during unwinding (50, 51, 66). Thus, the two parts of each T-antigen hexamer would be positioned on ssDNA to coordinate RPA binding to its N-terminal sites with pol-prim binding to its C-terminal sites (Fig. 1). We speculate that the T-antigen hexamer must bind coordinately to RPA-ssDNA and pol-prim to mediate priming. In this scenario, the 5030 hexamer would position the RPA and pol-prim correctly on the hexamer, perhaps to exchange RPA for pol-prim, and hence maintain the ability to stimulate primer synthesis on RPA-coated ssDNA. Conversely, the relative positioning of RPA and pol-prim by the 5031 hexamer may be faulty, compromising its ability to mediate primer synthesis on RPA-ssDNA. Consistent with the idea that T-antigen hexamers may be required to mediate priming on RPA-ssDNA, the 5061 T antigen fails to form hexamers or promote priming, despite its ability to bind ssDNA and undergo functional interactions with RPA-ssDNA and pol-prim that are similar to those of 5030 and 5031 T antigens.

Although any one of the models suggested above could account for the inability of 5031 and 5061 to mediate priming, we cannot rule out the possibility that more than one model is involved. Further experimental work will be required to test these speculative models and elucidate how T antigen mediates priming and elongation by pol-prim on RPA-coated ssDNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Pipas for providing recombinant baculoviruses to express the mutant T antigens, Vladimir Podust for E. coli SSB and M13 DNA, Christoph Rehfuess for the His-p68 baculovirus, David Lane for 9D5, and our reviewers for constructive criticism.

The financial support of NIH grant GM52948 and Vanderbilt University is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arezi, B., and R. D. Kuchta. 2000. Eukaryotic DNA primase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:572-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbaro, B. A., K. R. Sreekumar, D. R. Winters, A. E. Prack, and P. A. Bullock. 2000. Phosphorylation of simian virus 40 T-antigen on Thr124 selectively promotes double-hexamer formation on subfragments of the viral core origin. J. Virol. 74:8601-8613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beernink, H. T. H., and S. W. Morrical. 1999. RMPs: recombination/replication mediator proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowiec, J. A., F. B. Dean, and J. Hurwitz. 1991. Differential induction of structural changes in the simian virus 40 origin of replication by T antigen. J. Virol. 65:1228-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowiec, J. A., F. B. Dean, P. A. Bullock, and J. Hurwitz. 1990. Binding and unwinding—how T antigen engages the SV40 origin of DNA replication. Cell 60:181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley, M. K., T. F. Smith, R. H. Lathrop, D. M. Livingston, and T. A. Webster. 1987. Consensus topography in the ATP binding site of the simian virus 40 and polyoma large tumor antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:4026-4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, K. A., Y. Lao, Z. He, C. J. Ingles, and M. S. Wold. 1997. Role of protein-protein interactions in the function of replication protein A (RPA): RPA modulates the activity of DNA polymerase alpha by multiple mechanisms. Biochemistry 36:8443-8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock, P. A. 1997. The initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32:503-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellino, A. M., P. Cantalupo, I. A. Marks, J. I. Vartikar, K. W. C. Peden, and J. M. Pipas. 1997. Trans-dominant and non-trans-dominant mutant simian virus 40 large T antigens show distinct responses to ATP. J. Virol. 71:7549-7559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clertant, P., and I. Seif. 1984. A common function for polyoma virus large-T and papillomavirus E1 proteins? Nature 311:276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins, K. L., A. A. R. Russo, B. Y. Tseng, and T. J. Kelly. 1993. The role of the 70-kDa subunit of human polymerase α in DNA replication. EMBO J. 12:4555-4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins, K. L., and T. J. Kelly. 1991. The effects of T antigen and replication protein A on the initiation of DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase α-primase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:2108-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean, F. B., J. A. Borowiec, T. Eki, and J. Hurwitz. 1992. The simian virus 40 T antigen double hexamer assembles around the DNA at the replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14129-14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dornreiter, I., A. Hoess, A. K. Arthur, and E. Fanning. 1990. SV40 T antigen binds directly to the large subunit of purified DNA polymerase alpha. EMBO J. 9:3329-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dornreiter, I., L. F. Erdile, I. U. Gilbert, D. von Winkler, T. J. Kelly, and E. Fanning. 1992. Interactions of DNA polymerase α-primase with cellular replication A and SV40 T antigen. EMBO J. 11:769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dornreiter, I., W. C. Copeland, and T. S.-F. Wang. 1993. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication requires the interaction of a specific domain of human DNA polymerase α with large T antigen. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:809-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fanning, E., and R. Knippers. 1992. Structure and function of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:55-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fouts, E. T., X. Yu, E. H. Egelman, and M. R. Botchan. 1999. Biochemical and electron microscopic image analysis of the hexameric E1 helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4447-4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frick, D. N., and C. C. Richardson. 2001. DNA primases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:39-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gai, D., R. Roy, C. Wu, and D. T. Simmons. 2000. Topoisomerase I associates specifically with simian virus 40 large-T-antigen double hexamer-origin complexes. J. Virol. 74:5224-5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurney, E. G., R. O. Harrison, and J. Fenno. 1980. Monoclonal antibodies against simian virus 40 T antigens: evidence for distinct subclasses of large T antigen and for similarities among nonviral T antigens. J. Virol. 34:752-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han, Y., Y.-M. Loo, K. T. Militello, and T. Melendy. 1999. Interactions of the papovavirus DNA replication initiator proteins, bovine papillomavirus type 1 E1 and simian virus 40 large T antigen, with human replication protein A. J. Virol. 73:4899-4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henricksen, L. A., C. B. Umbricht, and M. S. Wold. 1994. Recombinant replication protein A: expression, complex formation, and functional characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 269:11121-11132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herendeen, D., and T. J. Kelly. 1996. SV40 DNA replication, p. 29-65. In J. J. Blow (ed.), Eukaryotic DNA replication. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 25.Huang, S.-G., K. Weisshart, I. Gilbert, and E. Fanning. 1998. Stoichiometry and mechanism of assembly of simian virus 40 T antigen complexes with the viral origin of DNA replication and DNA polymerase α-primase. Biochemistry 37:15345-15352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iftode, C., Y. Daniely, and J. A. Borowiec. 1999. Replication protein A (RPA): the eukaryotic SSB. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 34:141-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny, M. K., U. Schlegel, H. Furneaux, and J. Hurwitz. 1990. The role of human single-stranded DNA binding protein and its individual subunits in simian virus 40 DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 265:7693-7700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenny, M. K., S. H. Lee, and J. Hurwitz. 1989. Multiple functions of human ssDNA binding protein in simian virus 40 DNA replication: single strand stabilization and stimulation of DNA polymerases alpha and delta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:9757-9761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Learn, B. A., S.-J. Um, L. Huang, and R. McMacken. 1997. Cryptic single-stranded-DNA binding activities of the phage λP and Escherichia coli DnaC replicaiton initiation proteins facilitate the transfer of E. coli DnaB helicase onto DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1154-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, S.-H., and D. K. Kim. 1995. The role of the 34-kDa subunit of human replication protein A in simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12801-12807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefebvre, S. D., M. L. Wong, and S. W. Morrical. 1999. Simultaneous interactions of bacteriophage T4 DNA replication proteins gp59 and gp32 with single-stranded (ss) DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22830-22838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohman, T. M., J. M. Green, and R. S. Beyer. 1986. Large scale overproduction and rapid purification of the Escherichia coli ssb gene product. Expression of the ssb gene under λ PL control. Biochemistry 25:21-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masterson, P. J., M. A. Stanley, A. P. Lewis, and M. A. Romanos. 1998. A C-terminal helicase domain of the human papillomavirus E1 protein binds E2 and the DNA polymerase α-primase p68 subunit. J. Virol. 72:7407-7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mastrangelo, I. A., P. V. Hough, J. S. Wall, M. Dodson, F. B. Dean, and J. Hurwitz. 1989. ATP-dependent assembly of double hexamers of SV40 T antigen at the viral origin of DNA replication. Nature 338:658-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McEntee, K., G. Weinstock, and I. R. Lehman. 1980. RecA protein-catalyzed strand assimilation: stimulation by Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:857-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melendy, T., and B. Stillman. 1993. An interaction between replication protein A and T antigen appears essential for primosome assembly during SV40 DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 268:3389-3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mer, G., A. Bochkarev, R. Gupta, E. Bochkareva, L. Frappier, C. J. Ingles, A. M. Edwards, and W. J. Chazin. 2000. Structural basis for the recognition of DNA repair proteins UNG2, XPA and RAD52 by replication factor RPA. Cell 103:449-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mer, G., A. Bochkarev, W. J. Chazin, and A. M. Edwards. 2000. Three-dimensional structure and function of replication protein A. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 65:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moarefi, I. F., D. Small, I. Gilbert, M. Hoepfner, S. K. Randall, A. R. R. Russo, U. Ramsperger, A. K. Arthur, H. Stahl, T. J. Kelly, and E. Fanning. 1993. Mutation of the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation site in simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen specifically blocks SV40 origin DNA unwinding. J. Virol. 67:4992-5002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murakami, Y., and J. Hurwitz. 1993. DNA polymerase α stimulates the ATP-dependent binding of simian virus 40 tumor T antigen to the SV40 origin of replication. J. Biol. Chem. 268:11018-11027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakami, Y., and J. Hurwitz. 1993. Functional interactions between SV40 T antigen and other replication proteins at the replication fork. J. Biol. Chem. 268:11008-11017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pipas, J. M. 1992. Common and unique features of T antigens encoded by the polyoma group. J. Virol. 66:3979-3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salas, M., J. T. Miller, J. Leis, and M. L. DePamphilis. 1996. Mechanisms for priming DNA synthesis, p. 131-176. In M. L. DePamphilis (ed.), DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 44.San Martin, C., M. Radermacher, B. Wolpensinger, A. Engel, C. S. Miles, N. E. Dixon, and J. M. Carazo. 1998. Three-dimensional reconstruction from cryoelectron microscopy images reveal an intimate complex between helicase DnaB and its loading partner DnaC. Structure 6:501-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider, C., K. Weisshart, L. A. Guarino, I. Dornreiter, and E. Fanning. 1994. Species-specific functional interactions of DNA polymerase α-primase with simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen require SV40 origin DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:3176-3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seif, R. 1982. New properties of simian virus 40 T antigen. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:1463-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.SenGupta, D. J., and J. A. Borowiec. 1992. Strand-specific recognition of a synthetic DNA replication fork by the SV40 large T antigen. Science 256:1656-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.SenGupta, D. J., and J. A. Borowiec. 1994. Strand and face: the topography of interactions between the SV40 origin of replication and T-antigen during the initiation of replication. EMBO J. 13:982-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smale, S. T., and R. Tjian. 1986. T-antigen-DNA polymerase α complex implicated in simian virus 40 DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:4077-4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smelkova, N. V., and J. A. Borowiec. 1997. Dimerization of simian virus 40 T-antigen hexamers activates T-antigen DNA helicase activity. J. Virol. 71:8766-8773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smelkova, N. V., and J. A. Borowiec. 1998. Synthetic DNA replication bubbles wound and unwound with twofold symmetry by a simian virus 40 T-antigen double hexamer. J. Virol. 72:8676-8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sreekumar, K. R., A. E. Prack, D. R. Winters, B. A. Barbaro, and P. A. Bullock. 2000. The simian virus 40 core origin contains two separate sequence modules that support T-antigen double-hexamer assembly. J. Virol. 74:8559-8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stenlund, A. 1996. Papillomavirus DNA replication, p. 679-697. In M. L. DePamphilis (ed.), DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 54.Sullivan, C. S., S. P. Gilbert, and J. M. Pipas. 2001. ATP-dependent simian virus 40 T-antigen-Hsc70 complex formation. J. Virol. 75:1601-1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Titolo, S., A. Pelletier, A.-M. Pulichino, K. Brault, E. Wardrop, P. W. White, M. G. Cordingley, and J. Archambault. 2000. Identification of domains of the human papillomavirus type 11 E1 helicase involved in oligomerization and binding to the viral origin. J. Virol. 74:7349-7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valle, M., C. Gruss, L. Halmer, J. M. Carazo, and L. E. Donate. 2000. Large-T-antigen double hexamers imaged at the simian virus 40 origin of replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:34-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voitenleitner, C., C. Rehfuess, M. Hilmes, L. O'Rear, P.-C. Liao, D. A. Gage, R. Ott, H.-P. Nasheuer, and E. Fanning. 1999. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of human DNA polymerase α-primase activity by phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:646-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voitenleitner, C., E. Fanning, and H.-P. Nasheuer. 1997. Phosphorylation of DNA polymerase α-primase by cyclin A-dependent kinases regulates initiation of DNA replication in vitro. Oncogene 14:1611-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waga, S., and B. Stillman. 1998. The DNA replication fork in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:721-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, M., J. Park, M. Ishai, J. Hurwitz, and S.-H. Lee. 2000. Species specificity of human RPA in simian virus 40 DNA replication lies in T-antigen-dependent RNA primer synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4742-4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, T. S.-F. 1996. Cellular DNA polymerases, p. 461-493. In M. L. DePamphilis (ed.), DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 62.Weisshart, K., H. Forster, E. Kremmer, B. Schlott, F. Grosse, and H.-P. Nasheuer. 2000. Protein-protein interactions of the primase subunits p58 and p48 with simian virus 40 T antigen are required for efficient primer synthesis in a cell-free system. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17328-17337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weisshart, K., M. K. Bradley, B. M. Weiner, C. Schneider, I. Moarefi, E. Fanning, and A. K. Arthur. 1996. An N-terminal deletion mutant of simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen oligomerizes incorrectly on SV40 DNA but retains the ability to bind to DNA polymerase α and replicate SV40 DNA in vitro. J. Virol. 70:3509-3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weisshart, K., P. Taneja, A. Jenne, U. Herbig, D. T. Simmons, and E. Fanning. 1999. Two regions of simian virus 40 T antigen determine cooperativity of double-hexamer assembly on the viral origin of DNA replication and promote hexamer interactions during bidirectional origin DNA unwinding. J. Virol. 73:2201-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weisshart, K., P. Taneja, and E. Fanning. 1998. The replication protein A binding site in simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen and its role in the initial steps of SV40 DNA replication. J. Virol. 72:9771-9781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wessel, R., J. Schweizer, and H. Stahl. 1992. Simian virus 40 T-antigen DNA helicase is a hexamer which forms a binary complex during bidirectional unwinding from the viral origin of DNA replication. J. Virol. 66:804-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiekowski, M., P. Droege, and H. Stahl. 1987. Monoclonal antibodies as probes for a function of large T antigen during the elongation process of simian virus 40 DNA replication. J. Virol. 61:411-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wold, M. S. 1997. Replication protein A: a heterotrimeric, single-stranded DNA-binding protein required for eukaryotic DNA metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:61-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu, C., D. Edgil, and D. T. Simmons. 1998. The origin DNA-binding and single-stranded DNA-binding domains of simian virus 40 large T antigen are distinct. J. Virol. 72:10256-10259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, C., R. Roy, and D. T. Simmons. 2001. Role of single-stranded DNA binding activity of T antigen in simian virus 40 DNA replication. J. Virol. 75:2839-2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu, H., Y. Wang, J. S. Bleuit, and S. W. Morrical. 2001. Helicase assembly protein gp59 of bacteriophage T4: fluorescence anisotropy and sedimentation studies of complexes formed with derivatives of gp32, the phage ssDNA binding protein. Biochemistry 40:7651-7661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yuzhakov, A., Z. Kelman, J. Hurwitz, and M. O'Donnell. 1999. Multiple competition reactions for RPA order the assembly of the DNA polymerase δ holoenzyme. EMBO J. 18:6189-6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]