Abstract

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are potentially powerful tools for therapeutic gene regulation. DNA cassettes encoding RNA polymerase III promoter-driven hairpin siRNAs allow long-term expression of siRNA in targeted cells. A variety of viral vectors have been used to deliver such cassettes to cells. Here we report on the development and use of a self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vector for siRNA delivery into mammalian cells. We demonstrate that this modified vector efficiently delivers siRNA into multidrug-resistant human breast and oral cancer cells and suppresses MDR1 gene expression. This results in rapid, profound, and durable reduction in the expression of the P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter and a substantial reversion of the drug-resistant phenotype. This research suggests that scAAV-based vectors can be very effective agents for efficient delivery of therapeutic siRNA.

Introduction

An important evolving aspect of cancer therapeutics is the selective regulation of genes associated with cancer causation or progression. RNA interference has emerged as a powerful technique for the selective suppression of gene expression in mammalian cells. Short double-stranded RNAs (siRNAs)3 of approximately 19–22 nt trigger specific catalytic degradation of complementary mRNAs through a multiprotein cytoplasmic complex without initiating the generalized cytotoxicity associated with longer dsRNAs [1–3]. While transfection of chemically synthesized siRNA can be partially effective, long-term targeted gene suppression in cells and whole organisms is best attained with RNA polymerase III promoter-driven hairpin siRNA-producing cassettes; these are commonly used in connection with vector-based systems [4,5].

An important aspect of vector based cancer therapeutics is the efficient delivery of therapeutic genes into the target cells. Although in some studies plasmid vectors are delivered into cells by transfection using polymers or liposomes, viruses usually provide higher gene delivery efficiency in most cell types, including primary cells. Thus various groups have developed different viral vectors for delivery of hairpin siRNA-producing cassettes [6–9]. Among these viral-based vectors, the adeno-associated viral vector (AAV) has many advantages including: (1) the ability to transduce both dividing and nondividing cells, (2) broad tropism, (3) lack of pathogenic and immunogenic effects, and (4) long-term expression due to persistent episomal status [10]. However, AAV is a single-stranded DNA virus, and complementary strand synthesis must take place prior to gene expression. The requirement for complementary-strand synthesis is one of the rate-limiting factors in the efficiency of expression from conventional AAV vectors. Recently, McCarty et al. [11] have developed self-complementary AAV (scAAV) to bypass this step by packaging both strands of an AAV genome as an inverted repeat. These scAAV vectors have demonstrated higher transduction efficiencies and faster onset of gene expression in HeLa cells [11] as well as mouse liver, muscle, and brain [12,13]. The scAAV vector cannot accommodate inserts longer than 2150 bp, but seems ideal for the short Pol III-based cassettes used for hairpin siRNA expression. Thus we have evaluated the potential of scAAV as a vector for siRNA targeted to an important cancer-associated gene.

A major obstacle to chemotherapy in cancer patients is the resistance to multiple anticancer drugs. One form of multidrug resistance (MDR) is associated with overexpression of the P-glycoprotein (the product of the MDR1 gene), a 170-kDa transmembrane ATPase that exports a variety of structurally and functionally diverse chemotherapeutic drugs from cells [14]. Many different approaches have been pursued to reverse the MDR phenotype. These approaches range from small-molecule organic compounds [15] to various types of large molecules, such as antisense oligonucleotides [16], ribozymes [17], and designed zinc-finger transcription factors [18,19]. In a previous study [20], we evaluated RNA interference as an approach for reversal of MDR. We concluded that long-term inhibition of P-glycoprotein expression could be attained if anti-MDR1 hairpin siRNAs were persistently expressed in cells. Here, we have used scAAV vectors successfully to deliver hairpin siRNA into multidrug-resistant human breast cancer cells (NCI/ADR-RES) and oral cancer cells (KB-C1). P-glycoprotein expression levels were dramatically reduced, resulting in substantial reversal of the MDR phenotype in the cells.

Results

Inhibition of MDR1 Expression by scAAV-Delivered siRNA

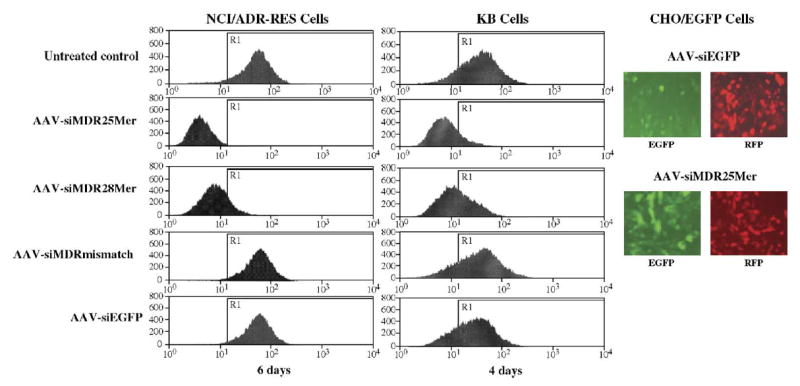

To evaluate initially the ability of self-complementary AAV vectors to deliver siRNA, we generated scAAVs containing a red fluorescent protein expression cassette and U6-promoter-based siRNA expression cassettes that express hairpin 25-mer, 28-mer, or mismatch siRNAs for MDR1 or hairpin siRNA for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). We infected drug-resistant human breast cancer cells NCI/ADR-RES and oral cancer cells KB-Cl with the above scAAV at 1200 particles (genome copies)/cell (with the exception of 5000 particles/cell for AAV-siMDR28mer) and cultured them for 6 and 4 days, respectively. We detected changes in P-glycoprotein expression level by flow cytometry and they are shown in Fig. 1. Self-complementary AAV-mediated expression of hairpin 25-mer and 28-mer siRNAs caused significant reduction in MDR1 gene expression and thus in the level of cell surface P-glycoprotein in both cell lines, while the mismatch MDR1 siRNA and siRNA targeting EGFP did not. On the other hand, as seen in the fluorescence microscope photographs, the scAAV-delivered hairpin EGFP siRNA dramatically reduced EGFP expression level in CHO/EGFP cells, while the 25-mer MDR1 siRNA did not. The red fluorescence is from the RFP coexpressed from the scAAV vector as a marker for transduction efficiency. It is noted that more particles of AAV-siMDR28mer were used because of the lower transducing efficiency of this particular virus.

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of cell surface P-glycoprotein expression by scAAV-delivered siRNA. NCI/ADR-RES, KB-Cl, and CHO/EGFP cells were infected with the indicated scAAV vectors at 1200 particles/cell (with the exception of 5000 particles/cell for AAV-siMDR28mer) and cultured for 6 or 4 days. Cell surface P-glycoprotein expression was estimated by immunostaining and flow cytometry as described under Materials and Methods. On the right EGFP and RFP expression were examined by fluorescence microscopy. On the left the abscissa represents the relative fluorescence from an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody bound to the primary anti-P-glycoprotein antibody. The ordinate is the number of cells at each level of fluorescence. The line marked R1 is a value of the P-glycoprotein fluorescence 2 standard deviations below the mean of the peak of the untreated control.

Dose- and Time-Dependent Inhibition of MDR1 Expression

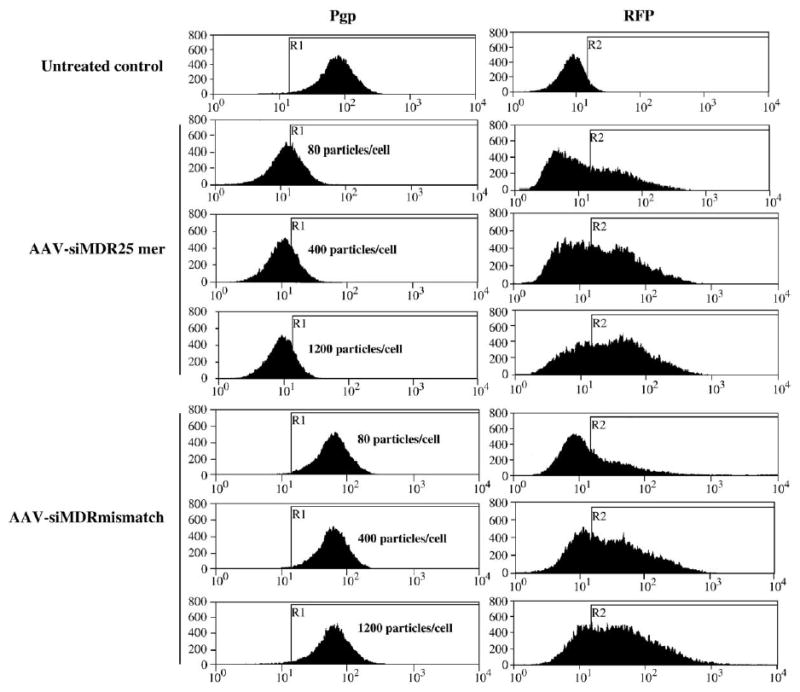

We infected NCI/ADR-RES cells with siRNA-carrying scAAVs at different dosages and cultured them for different time periods. We detected the changes in cell surface P-glycoprotein expression levels by flow cytometry. Fig. 2 shows a progressive reduction in P-glycoprotein expression with increasing viral titer, with 1200 particles per cell providing the greatest inhibition. However, the same dose of scAAV-siMDRmismatch did not affect P-glycoprotein expression.

FIG. 2.

Dose-dependent inhibition of P-glycoprotein expression by scAAV-delivered siRNA. NCI/ADR-RES cells were infected with scAAVs expressing anti-MDR1 25-mer or mismatch hairpin siRNAs at different titers and cultured for 3 days. P-glycoprotein (Pgp) and RFP expression levels were estimated by flow cytometry as described under Materials and Methods. The abscissa represents the relative fluorescence from an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (left) or from RFP (right). The ordinate is the number of cells at each level of fluorescence. The line marked R1 is a value of the P-glycoprotein fluorescence 2 standard deviations below the mean of the peak of the untreated control. The line R2 marks 1 standard deviation above the background fluorescence in the red channel in the untransfected controls.

In terms of time course, substantial inhibition began 2 days after viral infection, was sustained for several days, and started to decline approximately 7 days after infection (Table 1). This is substantially longer than effects we had previously attained with delivery of chemically synthesized siRNAs [20]. This may be due to the greater stability of scAAV episomes compared to synthetic siRNAs. To see whether even longer suppression could be achieved, we incubated the cells in 2% serum after the infection to prevent cells from dividing. We observed a prolonged effect on P-glycoprotein expression; cells started to reexpress P-glycoprotein only at about 14 days after the infection. As controls, the MDR1 mismatch siRNA and EGFP siRNA delivered by scAAV did not have any effect on the expression of P-glycoprotein 6 days after infection. Table 1 also shows the inhibition of P-glycoprotein by transfection of chemically synthesized siRNA; in this case, the effect observed 3 days after the treatment (at which the maximum inhibition was obtained) was much less significant than the effect caused by scAAV-delivered siRNA at the same time point.

TABLE 1.

Percentage reduction in cell surface P-glycoprotein

| Day | AAV-siMDR28mer | AAV-siMDR25mer | AAV-siMDR25mer (2% serum) | AAV-siMDR mismatch | AAV-siEGFP | Synthesized siMDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2 | 71% | 78% | —a | — | — | — |

| 3 | 85% | 82% | — | — | — | 38% |

| 5 | 89% | 88% | — | — | — | — |

| 6 | 88% | 92% | — | 2% | 0% | — |

| 7 | 69% | 84% | 94% | — | — | — |

| 10 | — | — | 91% | — | — | — |

| 12 | 0% | 0% | — | — | — | — |

| 14 | — | — | 80% | — | — | — |

Time-dependent inhibition of cell surface P-glycoprotein expression by scAAV-delivered siRNA. NCI/ADR-RES cells were infected with scAAVs expressing 25-mer (1200 particles/cell) or 28-mer (5000 particles/cell) hairpin siRNA for MDR1 and cultured for various times. P-glycoprotein expression levels were estimated by flow cytometry as above. The percentage reductions in P-glycoprotein levels were calculated as [(average fluorescence of untreated control − average fluorescence of treated sample)/average fluorescence of untreated control] × 100. The first two columns represent cells cultured in normal (10%) serum, while the third column represents cells cultured in low (2%) serum. The fourth and fifth columns represent the effects of control vectors expressing mismatch or EGFP siRNA. For comparison, the last column indicates the effects of transfecting 200 nM chemically synthesized MDR1 siRNA (delivered using Lipofectamine 2000) on P-glycoprotein expression levels when measured at 3 days (the time of maximal effect).

Not shown (—).

Reversal of the MDR Phenotype by scAAV-Delivered Hairpin siRNA

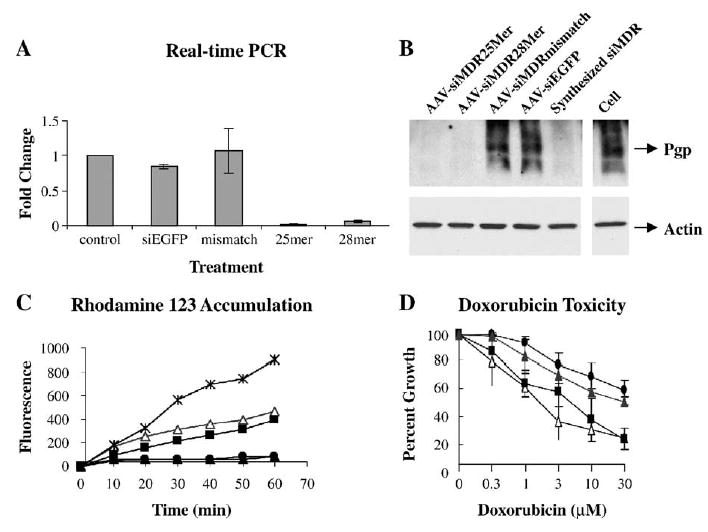

To evaluate the efficacy of scAAV as a potential therapeutic agent to suppress MDR, we further analyzed the effects of scAAV-delivered hairpin 25-mer and 28-mer MDR1 siRNA on MDR1 expression and the MDR phenotype in NCI/ADR-RES cells. Real-time reverse transcription PCR performed 3 days after infection (Fig. 3A) and Western blot (Fig. 3B) performed 5 days after infection showed correlated degrees of reduction in the MDR1 mRNA level and total P-glycoprotein level. Cells infected with scAAV-delivered mismatch hairpin MDR1 siRNA and EGFP hairpin siRNA expressed levels of MDR1 message and P-glycoprotein similar to those of untreated controls. The strong inhibition of P-glycoprotein expression by hairpin 25-mer and 28-mer MDR1 siRNA led to dramatic increases in drug uptake as assayed 5 days after infection by flow cytometry using rhodamine 123 (Rh123) as a P-glycoprotein substrate (Fig. 3C); by contrast, the drug uptake in the mismatch-siRNA-carrying AAV-infected cells remained the same as that of the control cells. Cytotoxicity assays of infected cells (Fig. 3D) showed doxorubicin dose–response profiles of scAAV-siMDR25mer- and scAAV-siMDR28mer-infected cells to be significantly left-shifted, with IC50 values of 1.5 and 2.5 μM, respectively, compared to 50 μM in the control cells. Therefore, delivery of 28-mer and 25-mer hairpin siRNAs with scAAV vectors led to a substantial reversal of doxorubicin resistance in these cells.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of MDR1 and reversal of the drug-resistant phenotype by scAAV-delivered hairpin siRNA in NCI/ADR-RES cells. (A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of MDR1 mRNA level. MDR1 mRNAs from the cells treated with scAAV (1200 particles/cell, or 5000 particles/cell for 28-mer) were quantified by real-time PCR. Values were normalized to those of GAPDH and expressed as fold change over untreated cells. Each experiment was repeated three times and means and standard errors are shown. (B) Western blot of P-glycoprotein. The scAAV treatments were as in A; in addition one set of cells was treated with the chemically synthesized anti-MDR1 siRNA described in Table 1 (200 nM, using Lipofectamine 2000). Top: P-glycoprotein was detected with C219 antibody. Bottom: The same membrane was reprobed with anti-actin antibody. (C) Rhodamine 123 uptake. Cells infected with scAAV producing 25-mer (open triangles), 28-mer (solid squares), or mismatch (solid triangles) hairpin MDR1 siRNA or untreated cells (solid circles) were exposed to 1 μg/ml Rh123 for various times. A comparison is shown to non-drug-resistant MCF7 breast carcinoma cells (X marks). Repeat experiments gave similar results. (D) The cytotoxicity profile of Adriamycin. Cells infected with scAAV (1200 particles/cell, or 5000 particles/cell for 28-mer) producing 25-mer (open triangles), 28-mer (solid squares), or mismatch (solid triangles) hairpin MDR1 siRNA or untreated cells (solid circles) were exposed for 24 h to various concentrations of Adriamycin (doxorubicin). After a further 48 h in complete growth medium, cell numbers were determined and expressed as percentage of control.

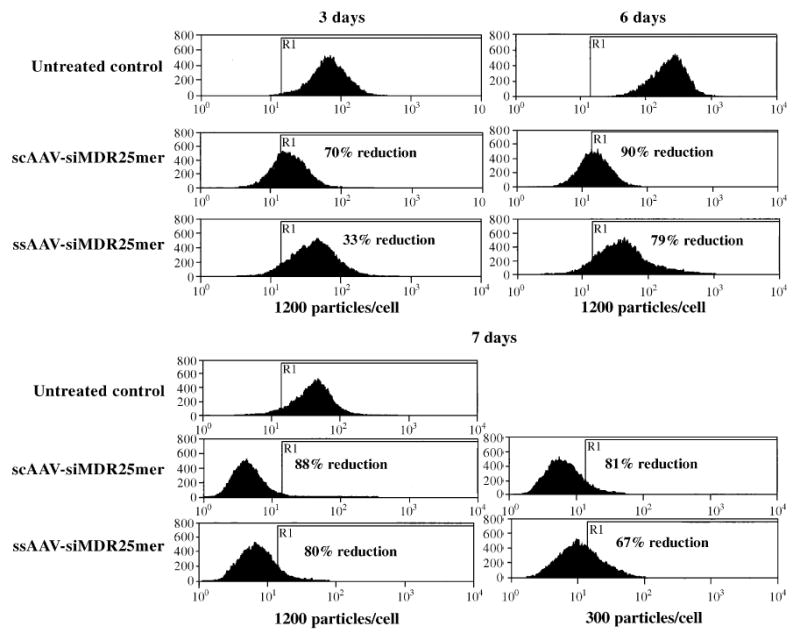

Comparison of the Efficacy of Hairpin siRNA Delivered by scAAV and ssAAV

We evaluated the relative efficiencies of ssAAV (conventional single-stranded AAV) and scAAV as tools to deliver siRNA into cells by transducing NCI/ADR-RES cells with the same number of particles of ssAAV-siMDR25mer and scAAV-siMDR25mer (Fig. 4). Self-complementary AAV-delivered hairpin MDR siRNA provided a greater inhibitory effect than the same construct delivered by single-stranded AAV. In particular, we observed a more rapid onset of action with the scAAV siRNA vector (for example, at 3 days after treatment). In addition the scAAV vector was more potent, even several days after transduction, particularly when lower doses of viral particles were used (for example, with 300 particles/cell).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the efficacy of hairpin siRNA delivered by scAAV and ssAAV. NCI/ADR-RES cells were infected with scAAVs or ssAAVs expressing 25-mer hairpin siRNA of MDR1 at 1200 or 300 particles (genome copies)/cell and cultured for various times. P-glycoprotein expression levels were estimated by flow cytometry. The percentage reductions in P-glycoprotein levels shown were calculated as [(average fluorescence of untreated control − average fluorescence of treated sample)/average fluorescence of untreated control] × 100.

Specificity of scAAV-Delivered Hairpin MDR1 siRNA

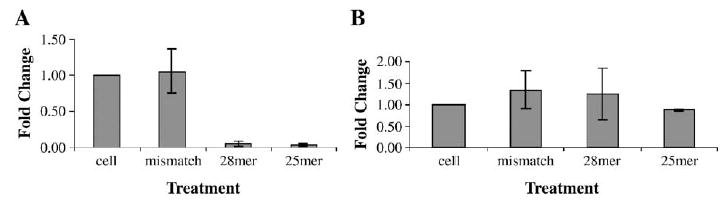

We evaluated the specificity of scAAV-delivered hairpin siRNA by real-time RT-PCR analysis comparing MDR1 expression with expression of MDR2, a closely related gene. Fig. 5 shows the reduction in the MDR1 mRNA level (Fig. 5A) but not in the MDR2 mRNA level (Fig. 5B) in the NCI/ADR-RES cells infected with scAAV-delivered hairpin 25-mer and 28-mer MDR1 siRNA. Cells infected with scAAV-delivered mismatch hairpin MDR1 siRNA expressed levels of MDR1 and MDR2 message similar to those of untreated controls.

FIG. 5.

Specificity of scAAV-delivered hairpin MDR1 siRNA measured by real-time PCR analysis. (A) MDR1 or (B) MDR2 mRNAs from NCI/ADR-RES cells treated with scAAV (1200 particles/cell, or 5000 particles/cell for 28-mer) were quantified by real-time PCR. Values were normalized with those of GAPDH and expressed as fold change over untreated cells. Each experiment was repeated three times and means and standard errors are shown.

Discussion

There is currently substantial interest in the possibility of using RNA interference in therapy. The prospect of selectively regulating key genes in various disease processes is an enticing one. However, a key limitation for therapeutics based on siRNA is the ability to deliver or express these molecules efficiently in disease-relevant cell settings. Obviously viral vectors bearing siRNA expression cassettes will be one important approach to this issue. The AAV vector has many appealing aspects as a gene delivery system, including the ability to transfect a broad range of dividing and nondividing cells, lack of pathogenic effects, and persistence of episomal expression. However, one problem has been the relatively slow onset of gene expression from AAV because of the need for second-strand DNA synthesis prior to RNA expression. However, the recently described scAAV vector system overcomes this limitation and allows rapid onset of expression [12,13].

In this report we have evaluated the merits of scAAV as a delivery system for siRNA in the context of MDR1, a gene that is important in cancer therapeutics. The MDR phenomenon is a difficult target for approaches that rely on regulation of gene expression. In many types of multidrug-resistant cells the MDR1 gene is highly amplified, its message is very abundant, and its protein product, the P-glycoprotein, is very stable and turns over slowly [21]. Thus MDR has proven a challenge for approaches based on antisense or ribozyme suppression of message levels [16,17].

Based on the above considerations, our experience with scAAV siRNA vectors is extremely positive. Both the 28-mer and the 25-mer anti-MDR1 hairpin siRNA vectors produced rapid (within 2 days) and dramatic reductions in P-glycoprotein levels in the entire cell population. In scAAV-treated NCI/ADR-RES cells, at the nadir, the cell surface expression of P-glycoprotein was only a few percent of that in the untreated controls. Further, the inhibition of expression was very durable, extending to 7 or more days in cells cultured in 10% serum or 10–14 days in cells in 2% serum. In addition, based on morphological observations, there was no indication of any cytotoxicity due to the vector. The reduction in expression of P-glycoprotein caused by scAAV siRNA was accompanied by an equally dramatic shift in cell phenotype. Thus the fluorophore Rh123, a P-glycoprotein substrate, was largely excluded from control drug-resistant cells, but was readily accumulated by cells treated with the scAAV vectors. This change in drug accumulation was paralleled by a change in drug toxicity profile. Thus untreated NCI/ADR-RES cells are quite resistant to the anti-tumor drug doxorubicin, with an IC50 of approximately 50 μM. Treatment with scAAV siRNA vectors directed at MDR1 strongly altered the toxicity profile, with the resulting IC50s being at least 10-fold less. In addition the action of the MDR1-directed scAAV vectors seemed quite selective, since expression of the closely related MDR2 gene was not affected. Thus the anti-MDR1 scAAV siRNA vectors produced a rapid, profound, durable, selective, and functionally significant change in MDR1 gene expression. Based on this experience we extrapolate that this type of vector may be a valuable tool in siRNA-based therapy of cancer and other diseases.

Materials and Methods

SiRNA sequences and plasmid construction.

The sequences of the hairpin siRNAs for anti-MDR1 25-mer and 28-mer, mismatch MDR1, and anti-EGFP are given in Table 2, and the hairpin siRNA expression plasmids were described previously [20]. To create the scAAV vectors expressing hairpin siRNAs, the U6-hairpin siRNA cassettes were PCR amplified from the plasmids using the following oligonucleotide primers: 5′-TATGGTACCACGACGGCCAGTGCCAAGCTT-3′ and 5′-AGTTACGTAATGAATTCCCCAGTGGAAAG-3′. The amplified fragments were inserted into KpnI- and SnaBI-digested p-trs-U1a-RFP vector (available upon request), which generates scAAV due to a mutation in one terminal repeat [12]. The small nuclear RNA promoter, U1a [22], was used to drive expression of the red fluorescent protein gene, derived from pDSRed2-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). To create single-stranded AAV vectors expressing hairpin siRNAs, pTRcmvGFP vector, with two wild-type terminal repeats [11], was digested with KpnI and the end was filled in using T4 DNA polymerase, followed by digestion with SalI. The DNA was then ligated with the U1a-RFP-U6-siRNA cassettes removed from scAAV-based plasmids by digestion with SnaBI and SalI. The resulting DNAs were partially digested and the stuffer DNA, a 2392-bp BglII-digested λ DNA (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA) fragment was inserted to make the vector genome too large to be packaged as a self-complementary dimer. All constructs were sequenced to ensure no mutations were introduced during the cloning.

TABLE 2.

Hairpin siRNA inserts

| siRNA | Sequence |

|---|---|

| siMDR25mer | 5′-GTATTGACAGCTATTCGAAGAGTGGttcaagagaCCACTCTTCG AATAGCTGTCAATACtttttt-3′ |

| siMDR28mer | 5′-GTATTGACAGCTATTCGAAGAGTGGGCAttcaagagaTGCCCAC TCTTCGAATAGCTGTCAATACtttttt-3′ |

| siMDRmismatch | 5′-GTATTGACAGCTATTCGAAGAGTGGGCAttcaagagaTGCCCAC TCTTCGAATACTGTCAATACtttttt-3′ |

| siEGFP | 5′-CGGCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTTCttcaagagaGAACTTCAGGGTC AGCTTGCCGtttttt-3′ |

Viral vectors, titers, and assays.

The scAAV and conventional rAAV vectors were produced by three-plasmid transient transfection in HEK 293 cells [23]. Approximately 5 × 108 cells per preparation were transfected using Superfect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). At 48 h postinfection, the cells were harvested, lysed by sonication, digested with benzonase, and brought to 1.38 g/cm3 with CsCl [24]. The vector was then isolated twice on CsCl gradients and the vector-containing fraction was identified by dot-blot hybridization. Therefore, all the particles obtained contained DNA rather than being empty particles. Replication center assays were performed on C12 cells as previously described to quantify the number of functional viruses [25].

Cells, viral infections, transfection.

The NCI/ADR-RES human breast cancer cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The KB-C1 human oral cancer cell line was kindly provided by Dr. M. Gottesman [26]. The cells were cultured in minimal essential medium or RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively, both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. CHO/EGFP cells were kindly provided by Dr. Ryszard Kole (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC, USA) and cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were infected with scAAV or ssAAV at the indicated particles (genome copies of virus) per cell and cultured for the indicated periods of time. The ratio of infectious units to total virus particles (1:10) was the same in each treatment and was consistent among various preparations. In addition to viral infections, for comparison, cells were also transfected with a chemically synthesized siRNA oligonucleotide (Dharmacon Research, Inc., Lafayette, CO, USA), targeted to MDR1 (5′-GUAUUGACAGCUAUUCGAAdTdT-3′/3′-dTdTCAUAACUGUCGAUAAGCUU-5′, sense/antisense) using Lipofectamine 2000, as previously described [20].

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated, cDNA was synthesized, and real-time RT-PCR was performed as we described previously [20]. The probe and primer set for MDR2 was purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA).

Measurement of total and cell surface P-glycoprotein.

Detection of total cellular P-glycoprotein and of other proteins by Western blotting was carried out as we have described previously [19]. Measurement of cell surface expression of P-glycoprotein was carried out by immunostaining with anti-P-glycoprotein antibody, followed by FITC-labeled secondary antibody, and flow cytometry, as we have described in detail elsewhere [19].

Rhodamine 123 uptake and drug toxicity.

Rhodamine 123 is a transport substrate of P-glycoprotein and its failure to accumulate in cells is a reflection of the MDR phenotype [27]. Accumulation of Rh123 was quantitated by flow cytometry as we have described previously [19]. The cytotoxic effect of the anti-tumor drug doxorubicin was evaluated as previously described [19]. Briefly, cells were placed into 24-well plates (Nunc) at 5 × 104 cells/well. Cells were incubated overnight followed by the addition of different amounts (0, 0.3–30 μM) of doxorubicin for 24 h. Drug and control medium were then removed and replaced with fresh medium and incubated for an additional 48 h. The surviving fraction was determined by the MTT dye assay as described [28].

Acknowledgments

We thank Vivian Cho for insightful advice and David Rinker for expert editorial assistance. This work was supported by NIH Grants RO1 CA77340 and PO1 GM 59299 to R.L.J.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: siRNA, small interfering RNA, scAAV, self-complementary adeno-associated virus, MDR, multidrug resistance, GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, RFP, red fluorescent protein.

References

- 1.McManus MT, Sharp PA. Gene silencing in mammals by small interfering RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:737–747. doi: 10.1038/nrg908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elbashir SM, et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbashir SM, et al. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee NS, et al. Expression of small interfering RNAs targeted against HIV-1 rev transcripts in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:500–505. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sui G, et al. A DNA vector-based RNAi technology to suppress gene expression in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5515–5520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082117599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Retroviral delivery of small interfering RNA into primary cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14943–14945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242594499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubinson DA, et al. A lentivirus-based system to functionally silence genes in primary mammalian cells, stem cells and transgenic mice by RNA interference. Nat Genet. 2003;33:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen C, et al. Gene silencing by adenovirus-delivered siRNA. FEBS Lett. 2003;539:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomar RS, Matta H, Chaudhary PM. Use of adeno-associated viral vector for delivery of small interfering RNA. Oncogene. 2003;22:5712–5715. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stilwell JL, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus vectors for therapeutic gene transfer. Biotechniques. 2003;34:148–150. doi: 10.2144/03341dd01. 152, 154 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarty DM, Monahan PE, Samulski RJ. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1248–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarty DM, et al. Adeno-associated virus terminal repeat (TR) mutant generates self-complementary vectors to overcome the rate-limiting step to transduction in vivo. Gene Ther. 2003;10:2112–2118. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu H, et al. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vector: global distribution and broad dispersion of AAV-mediated transgene expression in mouse brain. Mol Ther. 2003;8:911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambudkar SV, et al. Biochemical, cellular, and pharmacological aspects of the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:361–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyland-Jones B, et al. Reversal of multidrug resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Cancer. 1993;72:3484–3488. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11+<3484::aid-cncr2820721615>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alahari SK, et al. Novel chemically modified oligonucleotides provide potent inhibition of P-glycoprotein expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata J, et al. Reversal of drug resistance using hammerhead ribozymes against multidrug resistance-associated protein and multidrug resistance 1 gene. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1021–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartsevich VV, Juliano RL. Regulation of the MDR1 gene by transcriptional repressors selected using peptide combinatorial libraries. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu D, et al. Selective inhibition of P-glycoprotein expression in multidrug-resistant tumor cells by a designed transcriptional regulator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:963–971. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu D, et al. Strategies for the inhibition of MDR1 gene expression. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richert ND, et al. Stability and covalent modification of P-glycoprotein in multidrug-resistant KB cells. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7607–7613. doi: 10.1021/bi00420a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartlett JS, et al. Efficient expression of protein coding genes from the murine U1 small nuclear RNA promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8852–8857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:2224–2232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2224-2232.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabinowitz JE, et al. Cross-dressing the virion: the transcapsidation of adeno-associated virus serotypes functionally defines subgroups. J Virol. 2004;78:4421–4432. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4421-4432.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zolotukhin S, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 1999;6:973–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akiyama S, et al. Isolation and genetic characterization of human KB cell lines resistant to multiple drugs. Somatic Cell Mol Genet. 1985;11:117–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01534700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Twentyman PR, Rhodes T, Rayner S. A comparison of rhodamine 123 accumulation and efflux in cells with P-glycoprotein-mediated and MRP-associated multidrug resistance phenotypes. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1360–1369. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmichael J, et al. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 1987;47:943–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]