Abstract

Late blight, caused by the notorious pathogen Phytophthora infestans, is a devastating disease of potato (Solanum tuberosum) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and during the 1840s caused the Irish potato famine and over one million fatalities. Currently, grown potato cultivars lack adequate blight tolerance. Earlier cultivars bred for resistance used disease resistance genes that confer immunity only to some strains of the pathogen harboring corresponding avirulence gene. Specific resistance gene-mediated immunity and chemical controls are rapidly overcome in the field when new pathogen races arise through mutation, recombination, or migration from elsewhere. A mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade plays a pivotal role in plant innate immunity. Here we show that the transgenic potato plants that carry a constitutively active form of MAPK kinase driven by a pathogen-inducible promoter of potato showed high resistance to early blight pathogen Alternaria solani as well as P. infestans. The pathogen attack provoked defense-related MAPK activation followed by induction of NADPH oxidase gene expression, which is implicated in reactive oxygen species production, and resulted in hypersensitive response-like phenotype. We propose that enhancing disease resistance through altered regulation of plant defense mechanisms should be more durable and publicly acceptable than engineering overexpression of antimicrobial proteins.

The timely recognition of invading microbes and the rapid induction of defense responses are essential for plant disease resistance. At least two recognition systems are used by plants (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Parker, 2003). Plant defenses are often initiated by a gene-for-gene interaction between a dominant plant resistance (R) gene and a pathogen avirulence (Avr) gene, which provides race-specific resistance that is easily overcome by pathogen mutations. Plants also use a much less specific recognition system that identifies pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as flagellin (Zipfel et al., 2004) and lipopolysaccharides (Zeidler et al., 2004), so-called general elicitors. Both animals and plants can recognize invariant PAMPs that are characteristic of pathogenic microorganisms. Perception of the peptide fragment of flagellin in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) depends on the Leu-rich repeat-type receptor kinase flagellin sensing 2 (FLS2; Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000). The fls2 mutant Arabidopsis is more susceptible to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 than wild-type plants (Zipfel et al., 2004), suggesting that recognition of PAMPs by plant cells potentiates defense responses. Understanding these plant signaling systems creates an opportunity to manipulate these systems to enhance resistance in crops. FLS2- and R-gene products share similarities with components of the animal innate immune system, suggesting that some downstream signaling components are common between plants and animals (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Staskawicz et al., 2001).

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade is one of the major and evolutionally conserved signaling pathways utilized to transduce extracellular stimuli into intracellular responses among eukaryotes (Ligterink et al., 1997; Nakagami et al., 2005). In these protein kinase cascades, MAPK kinase (MAPKK) is activated by upstream MAPKK kinase (MAPKKK) and finally activates MAPK. It was shown that a MAPK cascade is involved in both FLS2- and R-gene products-mediated innate immunity (Asai et al., 2002). NtMEK2, a tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) MAPKK, is known to activate both salicylic acid (SA)-induced protein kinase (SIPK) and wound-induced protein kinase (WIPK). Expression of NtMEK2DD, a constitutively active allele of NtMEK2, induced hypersensitive response (HR)-like cell death, defense gene expression, and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS; Yang et al., 2001; Ren et al., 2002). We also showed that the constitutively active mutant of potato (Solanum tuberosum) ortholog of tobacco NtMEK2, StMEK1DD (the prefix St indicates S. tuberosum), provokes SIPK and WIPK activities (Katou et al., 2003) followed by induction of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (rboh) gene expression, which is implicated in ROS production, in Nicotiana benthamiana (Yoshioka et al., 2003). Loss of function of either SIPK (or Arabidopsis ortholog AtMPK6) or WIPK compromised N gene-mediated gene-for-gene resistance to tobacco mosaic virus infection (Jin et al., 2003) and resistance to bacterial pathogens (Sharma et al., 2003; Menke et al., 2004). These results indicate that SIPK and WIPK are convergent points in the signaling pathway of defense responses in plant-pathogen interactions. The facts led us to propose that modulation of MAPK cascades enables plants to resist pathogen invasion. When multiple defense responses are triggered rapidly and coordinately during plant-pathogen interactions, the plant shows resistance to the pathogens. In contrast, susceptible plants respond more slowly than resistant plants with an onset of defense mechanisms after pathogen attack. We propose that StMEK1DD can accelerate MAPK signal transduction efficiently and enable plants to resist pathogen invasion. However, constitutive activation of the defense mechanism can be lethal to a plant.

Exposure of potato plants to only an avirulent Phytophthora infestans (late blight pathogen) causes multiple defense responses, including the oxidative burst, nitric oxide production, and accumulation of antifungal sesquiterpenoid phytoalexins (lubimin and rishitin) dependent upon de novo synthesis of the enzymes involved in their production (Doke, 1983; Oba et al., 1985; Yamamoto et al., 2003). However, the R-mediated immunity is rapidly overcome in the field when new pathogen races arise through mutation, recombination, or migration from elsewhere (Turkensteen, 1993). During the 1840s, the late blight pathogen caused the Irish potato famine and over one million fatalities. Most of currently grown potato cultivars lack durable resistance. To generate transgenic potato plants, which have enhanced disease resistance without the yield penalty associated with constitutive defense expression, a virulent pathogen-inducible potato promoter is required. Phytoalexins are generally synthesized in plants primarily at sites of pathogen infection. Sesquiterpene cyclase is a key branch enzyme of isoprenoid pathway for the synthesis of sesquiterpenoid phytoalexins (Fig. 1; Zook and Kuc, 1991; Back and Chappell, 1995). Complementary DNAs encoding potato vetispiradiene synthase (PVS), a sesquiterpene cyclase, which catalyzes farnesyl diphosphate into vetispiradiene, a precursor of lubimin and rishitin, were isolated. Infection of P. infestans with potato tubers caused transient increases in the transcript level of PVS during not only incompatible but also compatible interactions (Yoshioka et al., 1999). Here we show that the transgenic potato plants, which were introduced by a constitutively active form of MAPKK (StMEK1DD) driven by the pathogen-inducible promoter of potato, developed normally and showed high resistance to early blight pathogen Alternaria solani as well as a virulent P. infestans.

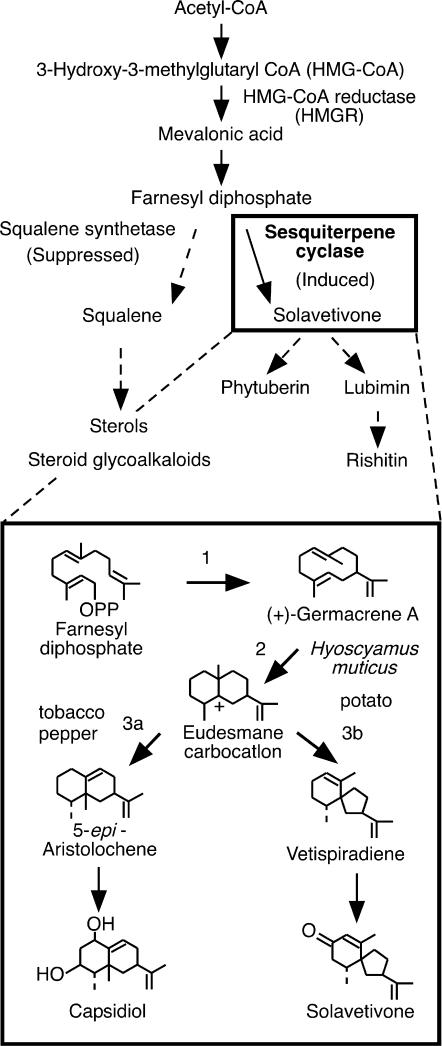

Figure 1.

A scheme of stimulus-responsive isoprenoid biosynthesis in solanaceous plants. Sesquiterpene cyclase is a key branch enzyme of isoprenoid pathway for the synthesis of sesquiterpenoid phytoalexins. Vetispiradiene synthase, which catalyzes farnesyl diphosphate into vetispiradiene (1, 2, 3b), produces a precursor of lubimin and rishitin in potato and H. muticus. 5-epi-Aristolochene synthase is a key enzyme for capsidiol production in tobacco and pepper (1, 2, 3a). Wound-induced sterol and steroid glycoalkaloid syntheses are suppressed in favor of sesquiterpenoid phytoalexin synthesis during expression of the HR.

RESULTS

PVS3 Promoter Is Induced in Potato Tubers and Leaves by the Inoculation with Pathogens

PVS, the key enzyme of the phytoalexin synthesis of potato, is encoded by a multiple-gene family (PVS1 to 4; Yoshioka et al., 1999). As one molecular approach to elucidation of the mechanisms that regulate the phytoalexin synthesis in potato after inoculation with P. infestans, here we isolated and characterized the genome clones encoding PVS1, 3, and 4. The sequence comparison between deduced amino acid sequences for PVSs, Hyoscyamus muticus vetispiradiene synthase (HVS), and other related enzymes, such as tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (TEAS) and pepper (Capsicum annuum) 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (PEAS), which are key enzymes for capsidiol production in tobacco and pepper (Fig. 1), is presented in Figure 2A. Functional domains for endogenous sesquiterpene cyclase (EAS) and VS are predicted by the domain-swapping experiments (Back and Chappell, 1996). The amino acid sequences of each domain among VS showed high homology. Interestingly, PVS1 and PVS4 lack the sixth intron, whereas PVS3 contains the intron identical to other synthases. These results suggest that PVS1 and PVS4 have evolved independently from other genes.

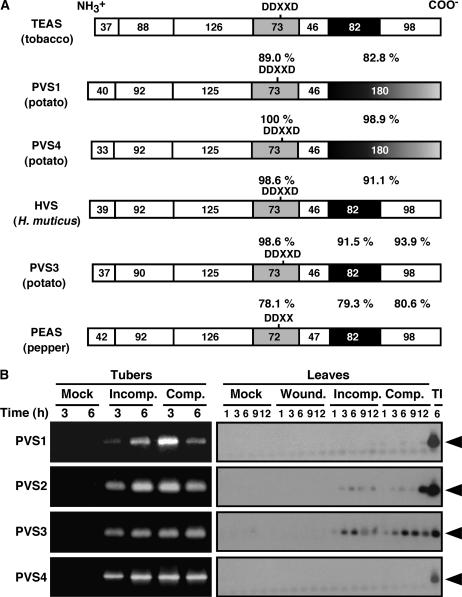

Figure 2.

PVS3 gene is activated by virulent and avirulent isolates of P. infestans in potato tubers and leaves. A, A schematic representation of amino cid sequence alignment between tobacco (TEAS), potato (PVS1, 3, and 4), H. muticus (HVS), and pepper (PEAS). Solid vertical bars correspond to intron positions within the tobacco, potato, H. muticus, and pepper genes. Numbers within the boxes indicate the number of amino acids encoded by exons. Aristlochene-specific domains and vetispiradiene-specific domains are shown as gray and black boxes, respectively. Percentages refer to identity scores between the indicated domains, and DDXXD (or DDXX) refers to Asp-rich (and known as the substrate-binding site) residues. Adapted from Back and Chappell (1995). B, The PVS3 gene is induced in both incompatible (Incomp.) and compatible (Comp.) interactions of P. infestans, but not by wounding (Wound.). RNA was extracted from tubers and leaves after the inoculation with virulent (race 1.2.3.4) and avirulent (race 0) isolates of P. infestans or wounding with Carborundum, and used for RT-PCR. Member-specific primers of PVS1 to 4 were used for PCR. RT-PCR products from leaves were separated on an agarose gel and blotted onto nylon membranes. The membranes were hybridized with each 32P-labeled PCR product as probes. Lane TI shows RT-PCR products of RNA isolated from potato tubers in incompatible interaction as a positive control.

Transgene activation to trigger the defense responses should occur only at the time and the site of pathogen challenge and not under other circumstances. In the field, disease caused by P. infestans can be initiated on the leaves. The virulent pathogen-inducible gene promoter in potato leaves is indispensable to drive the transgene that cues cell death. As shown in Figure 2B, PVS3 was significantly induced in leaves in both incompatible and compatible interactions of P. infestans, but not by wounding. We tested whether PVS3 promoter is useful to drive the StMEK1DD in response to P. infestans. The PVS3 promoter was fused to the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene, and the temporal and spatial expression patterns of GUS were monitored in the transgenic potato plants. No GUS activity was detected in leaves, roots, and growth points of unstimulated transgenic plants (data not shown). These results suggest that PVS3 promoter is suitable for generation of disease-resistant transgenic potato plants.

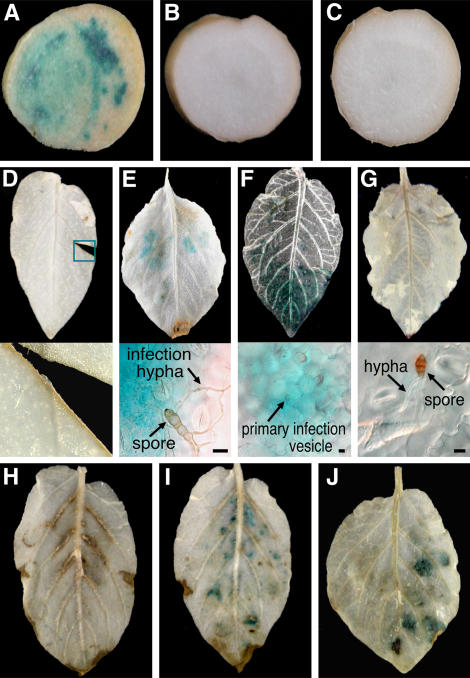

To investigate the adaptable range of the PVS3 promoter, we monitored GUS activities in the PVS3::GUS transgenic potato leaves under biotical or physical stimuli. Inoculation with mock (Fig. 3B) and nonpathogen Escherichia coli (Fig. 3C), and Alternaria alternata Japanese pear (Pyrus serotina Rehd.) pathotype strain 15A (Fig. 3G), did not induce the GUS activity because these microbes cannot invade inside the plant cells. Importantly, wounding of the potato plants also did not activate the PVS3 promoter (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the promoter was strongly activated in transgenic potato plant by inoculation with the virulent P. infestans (Fig. 3, A and F) and early blight pathogen A. solani strain A-17 (Fig. 3E) in the restricted sites where pathogens tried to infect. These results confirm that the PVS3 promoter is specifically and locally activated by pathogens and thus suitable to drive StMEK1DD.

Figure 3.

Expression profile of GUS gene under the control of PVS3 promoter in the transgenic potato tubers and leaves. Transgenic potato tubers harboring PVS3::GUS were inoculated with the virulent P. infestans (A), mock (B), and E. coli (C). The transgenic potato leaves were treated with wounding (D) or inoculated with A. solani (E), P. infestans (F), and A. alternata Japanese pear pathotype (G). Agrobacterium-carrying vector (H), 35S::Avr9/Cf-9 (I), or 35S::StMEK1DD (J) was infiltrated into transgenic potato leaves. Genes for Avr9/Cf-9 and StMEK1DD were driven by the 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus. Tubers and leaves were stained with GUS staining solution 9 h (A), 24 h (F), or 48 h (B–E, and G–J) after the treatments. Scale bars = 10 μm.

PVS3 Promoter Is Controlled by MAPKs

We investigated the control mechanism of the PVS3 promoter by Agrobacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens) infiltration (agroinfiltration). PVS3 promoter was not activated by inoculation with Agrobacterium-carrying vector (control; Fig. 3H). In contrast, the promoter was activated in response to Agrobacterium-carrying Avr9/Cf-9, Avr-R interaction (Thomas et al., 2000; Fig. 3I), or StMEK1DD (Fig. 3J). The promoter was also activated by treatment with general elicitors, such as cell wall and arachidonic acid of P. infestans (data not shown). It has been reported that treatment with these elicitors, Avr9/Cf-9 interaction, and StMEK1DD activate SIPK and WIPK (Katou et al., 1999, 2003; Romeis et al., 1999). Taken together, these observations suggest that the activation of PVS3 promoter is controlled by the MAPK cascade.

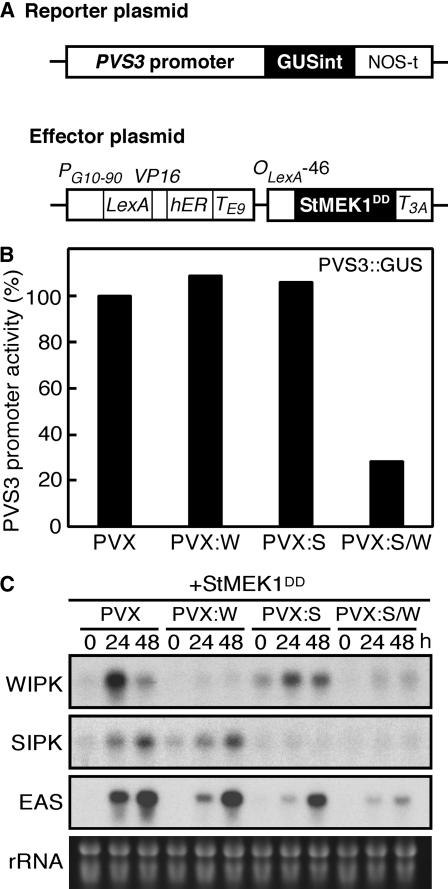

To investigate this possibility, we employed virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in N. benthamiana using a potato virus X (PVX) vector (Lu et al., 2003). SIPK- and/or WIPK-silenced leaves were coinfiltrated with a mixture of Agrobacterium cultures containing PVS3::GUSint (reporter; pPVS3-1), which carried an intron (int) to avoid expression in Agrobacterium, and pER8::StMEK1DD (effector) T-DNA constructs (Fig. 4A). To synchronize expression of the effector genes in N. benthamiana leaves and to make a time lag (48 h) between the reporter and effector genes following agroinfiltration, we used an estradiol-inducible expression system developed for use in plant cells (Zuo et al., 2000). Transcripts for SIPK and/or WIPK were substantially less abundant in gene-silenced N. benthamiana infected with PVX (WIPK, SIPK, SIPK/WIPK) than those in controls infected with an empty PVX vector (Fig. 4C). Only VIGS of both SIPK and WIPK reduced GUS activity in response to StMEK1DD (Fig. 4B), indicating that the PVS3 promoter is controlled by both SIPK and WIPK. In addition, we confirm that EAS, a key enzyme for capsidiol production (Yin et al., 1997) in N. benthamiana, is also regulated by SIPK and WIPK (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

PVS3 promoter is controlled by both SIPK and WIPK. A, Scheme of reporter and effector plasmids used in transient assays. The reporter plasmid PVS3 promoter fragment (positions −2,334 to +30) was translationally fused to the GUS gene containing intron (GUSint). The effector plasmid estradiol-inducible promoter was fused to the StMEK1DD gene. B, Half leaf of gene-silenced N. benthamiana was coinfiltrated with a mixture of Agrobacterium harboring PVS3::GUSint (reporter) or pER8::StMEK1DD (effector). Estradiol (10 μm) was injected 48 h after agroinfiltration to activate the effector. GUS activities driven by PVS3 promoter in response to StMEK1DD were measured in gene-silenced N. benthamiana by PVX (PVX-control [PVX], WIPK [PVX:W], SIPK [PVX:S], SIPK/WIPK [PVX:S/W]) 24 h after estradiol injection. Results are presented as relative values calibrated by GUS activity, which were measured by fluorometric quantitation of 4-MU, under the control of 35S promoter in another half leaf. The PVX-control with StMEK1DD was arbitrarily assigned as 100% value against which all other values were plotted. C, Expression profiles of EAS in the gene-silenced N. benthamiana. Total RNA was isolated from gene-silenced N. benthamiana leaves after infiltration with Agrobacterium harboring 35S::StMEK1DD, and transcript levels of WIPK, SIPK, and EAS were determined by RNA gel-blot hybridization.

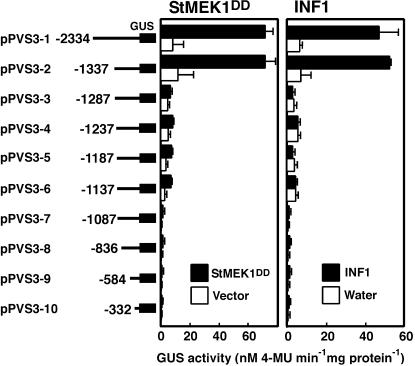

To determine the 5′ boundary of the region that is important for the activity of the PVS3::GUSint fusion in response to StMEK1DD and INFESTIN (INF1; Kamoun et al., 1997), elicitor derived from P. infestans in N. benthamiana, a series of 5′ deletions of the PVS3 promoter was constructed. GUS activity driven by each construct was measured in the transient gene expression assay 24 h after treatment with effectors. The promoter region of PVS3, pPVS3-1 (2,334 bp), conferred responsiveness to the StMEK1DD and INF1 (Fig. 5). Deletion to pPVS3-3 (−1,287) resulted in a clear reduction of the effector-responsive GUS activity. Further deletions from pPVS3-4 to pPVS3-10 did not affect the GUS activity. A 50-bp promoter region of PVS3 (positions −1,337 to −1,287) was shown to play an important role in transcriptional activation in response to both StMEK1DD and INF1 (Fig. 5). Both StMEK1DD and INF1 elicitor activate the SIPK and WIPK (Katou et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2003), indicating that the PVS3 promoter is controlled by these MAPKs.

Figure 5.

Deletion analysis of the PVS3 promoter in response to StMEK1DD and INF1 in N. benthamiana leaves. A series of 5′-deleted PVS3 promoter fragments was translationally fused to the GUSint reporter gene. The number indicates the distance from the PVS3 translation start site. To induce the expression of StMEK1DD, 20 μm estradiol was injected into the leaves 48 h after a mixture of Agrobacterium cultures containing PVS3::GUSint (reporter) and pER8::StMEK1DD (effector) was coinfiltrated. Ten micrograms mL−1 INF1 was injected into leaves 48 h after a mixture of Agrobacterium cultures containing PVS3::GUSint was infiltrated. GUS activities were determined 24 h after the treatments and measured by fluorometric quantitation of 4-MU. Each value and bar represents the mean of three independent experiments and sd from the mean, respectively.

Potato Ortholog of Tobacco SIPK, StMPK1, Is Activated by the Inoculation with a Virulent Isolate of P. infestans

Previous studies have shown that a 51-kD MAPK is activated in potato tuber tissue by treatment with an elicitor, hyphal wall components (HWC) prepared from P. infestans or SA and arachidonic acid, which are known to induce various defense responses in potato plants (Katou et al., 1999). The molecular mass and activation profile of this kinase to a variety of elicitors, including SA, suggested that it might be a potato ortholog of tobacco SIPK. We recently purified the 51-kD MAPK, which was activated in potato tubers treated with HWC, and isolated the corresponding cDNA, designated StMPK1 (Katou et al., 2005). The deduced amino acid sequence of the StMPK1 showed strong similarity to stress-responsive MAPKs, such as SIPK and Arabidopsis AtMPK6.

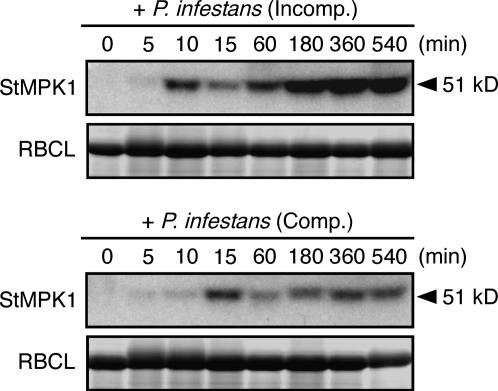

To gain a better understanding of the involvement of the MAPK cascade in the defense responses of potato leaves, we investigated the MAPK activity after the inoculation with a virulent or an avirulent isolate of P. infestans. In-gel kinase assay using myelin basic protein (MBP) as a substrate revealed that activation of the 51-kD MAPK (StMPK1) was rapidly induced in response to both virulent and avirulent P. infestans, which clearly precedes the expression of PVS3 (Figs. 2B and 6). These results suggest that components of the innate immunity system are induced not only in incompatible but also in compatible interactions.

Figure 6.

A 51-kD MAPK is activated during incompatible and compatible P. infestans-potato interactions in potato leaves. A 51-kD MAPK activity, which was identified as StMPK1 (AB062138), was indicated by in-gel kinase assay using MBP as a substrate. The same samples were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, and the bands corresponding to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit (RBCL) are shown.

Transgenic Potato Plants Harboring PVS3::StMEK1DD Show Resistance to Virulent Isolates of P. infestans and A. solani

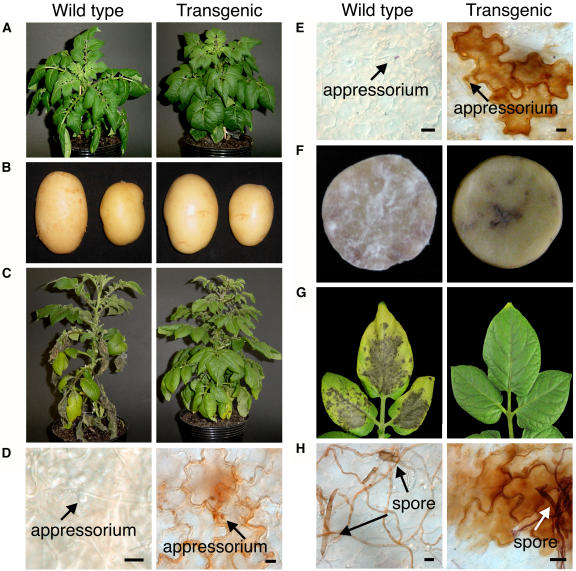

We produced transgenic potato plants carrying the StMEK1DD allele expressed from the PVS3 promoter. The transgenic plants and tubers developed normally (Fig. 7, A and B). The transgenic potato leaves as well as tubers showed high resistance to a virulent P. infestans (Fig. 7, C and F) and displayed an HR-like cell death phenotype (Fig. 7, D and F) accompanied by accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) around the infected cell (Fig. 7E). We also examined whether PVS3::StMEK1DD transgenic potato plants show resistance to the necrotrophic pathogen A. solani. Six days after inoculation, typical disease symptoms appeared on the wild-type potato leaves. In contrast, transgenic potato leaves showed an HR-like cell death phenotype (Fig. 7G) and accumulated H2O2 around infected tissue (Fig. 7H). These results suggest that the transgenic potato plants provoke oxidative burst and show high resistance not only to the biotrophic pathogen P. infestans but also to the necrotrophic pathogen A. solani.

Figure 7.

Transgenic potato plants harboring PVS3::StMEK1DD show resistance to P. infestans and A. solani. A, The transgenic plants developed normally. B, The transgenic tubers developed normally. C, Eleven days after inoculation of wild-type and transgenic leaves with virulent P. infestans. D, HR-like cell death was observed under the microscope 24 h after inoculation with virulent P. infestans in transgenic leaves. E, H2O2 accumulation visualized by DAB was observed under the microscope 12 h after the inoculation. F, Three days after inoculation of wild-type and transgenic potato tubers with virulent P. infestans. G, Six days after inoculation of wild-type and transgenic leaves with A. solani. H, H2O2 accumulation was observed 24 h after the inoculation. Scale bars = 10 μm.

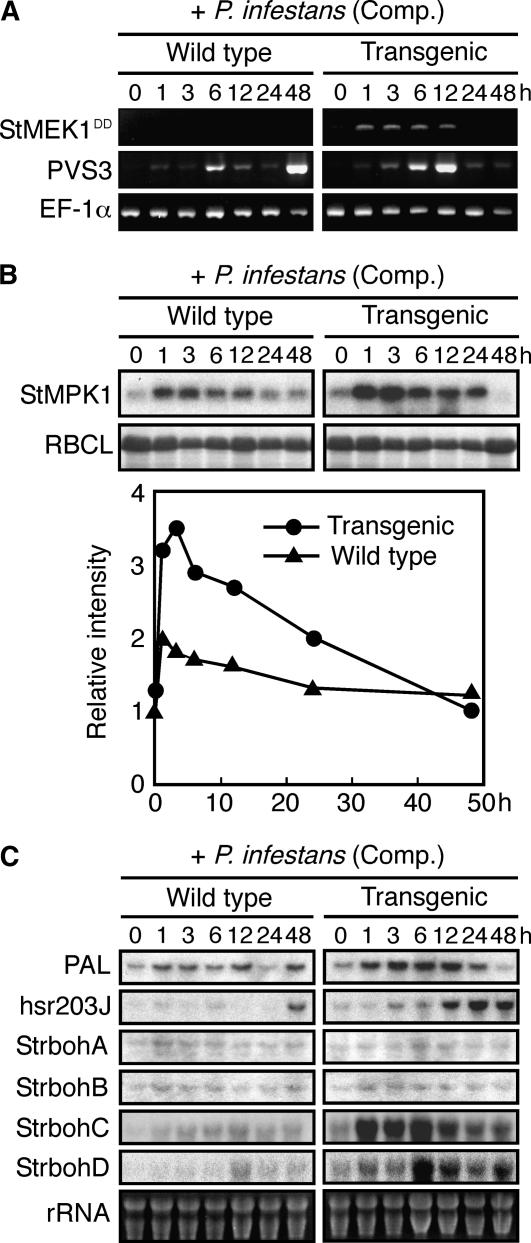

Transgenic Potato Plants Indicate Elevation of MAPK Activity and Up-Regulation of Defense-Related Genes during Compatible P. infestans-Potato Interactions

To investigate whether the HR-like phenotype correlated with introduced StMEK1DD expression, we analyzed RNA and protein extracts from leaves of transgenic plants in compatible P. infestans-potato interactions. The induction of StMEK1DD and rapid elevation of MAPK activity compared to wild-type plants was observed within 1 h (Fig. 8, A and B). The transcript level of StMEK1DD was decreased 24 h after pathogen inoculation (Fig. 8A) in agreement with profile of StMPK1 activity (Fig. 8B). These data suggest that the switch off of the gene resulted from localized cell death induced by the pathogen attack because HR-like cell death was observed 24 h after inoculation (Fig. 7D). In-gel kinase assay detected only StMPK1 activity; however, immunoprecipitation analyses using specific antibodies showed that both StMPK1 and StWIPK are activated in response to P. infestans (data not shown). A likely explanation for this is that basal levels of StMPK1 in unstimulated plant cells are much higher (10-fold) than those of StWIPK (Zhang and Klessig, 1998). Alternatively, StWIPK proteins may be more unstable under denaturing conditions in SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Figure 8.

Transgenic potato plants indicate elevation of MAPK activity and up-regulation of defense-related genes during compatible P. infestans-potato interactions. Total RNA and proteins were isolated from potato leaves after the inoculation with virulent P. infestans at indicated times and used for RT-PCR (A), in-gel kinase assay (B), or RNA gel-blot analyses (C). For RT-PCR, 28, 40, and 30 amplification cycles were applied with specific primers for StMEK1DD transgene, endogenous PVS3, and constitutively expressed EF-1α, respectively. The MAPK activity was assayed with in-gel kinase assay using MBP as a substrate. The same samples were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, and the bands corresponding to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit (RBCL) are shown. The transcript levels of defense-related genes were determined by sequential probing with cDNA probes indicated on the left side of the sections.

To examine whether the activation of endogenous MAPKs by introduced StMEK1DD provokes the expression of defense-related genes, expression profiles for Phe ammonia-lyase (PAL) and hsr203J (HR marker) were determined (Fig. 8C) because it was reported that their expression is regulated by a MAPK cascade (Yang et al., 2001; Yoshioka et al., 2003; Takahashi et al., 2004). These genes were up-regulated in transgenic leaves in comparison with wild-type potato leaves. In addition, the expression pattern of StrbohA to D (plant NADPH oxidases) was also investigated. Oxidative burst is proposed to be responsible for HR cell death correlated with defense responses. StrbohC and StrbohD were drastically induced in the infected transgenic plants.

DISCUSSION

Ever since the initial discovery of the molecules and genes involved in disease resistance in plants, attempts have been made to engineer disease resistance in economically important crop plants. Genetic engineering has proved to be a powerful tool for controlling plant diseases and to be an alternative to economically costly and environmentally undesirable chemical control. To date, transgenic disease-resistant plants include constitutively overproducing α-thionin (Carmona et al., 1993) and the Ustilago maydis killer toxin (Park et al., 1996), and expressing genes encoding enzymes that are involved in the biosynthesis of antimicrobial compounds (Hain et al., 1993) have been produced. Other approaches have been based on the overexpression of genes encoding proteins that are produced during the natural defense responses, such as PR-1a (Alexander et al., 1993), chitinase (Broglie et al., 1991), or osmotin (Liu et al., 1994). An additional possibility involves the production of proteins that generate a signaling event and trigger the permanent onset of an array of defense responses, such as H2O2-generating Glc oxidase (Wu et al., 1995, 1997). Constitutive expression of the Arabidopsis NIM1/NPR1 gene, which is a mediator of systemic acquired resistance, results in varying degrees of resistance to different pathogens (Cao et al., 1998; Friedrich et al., 2001). Furthermore, enhanced disease resistance mutants have been identified (Bowling et al., 1994; Frye et al., 2001). Most plants possessing constitutive expression of a defense pathway show reduced yield or other deleterious phenotypes. Recently, R genes, which confer broad-spectrum late blight resistance in cultivated potato, were identified from wild-type potato (Song et al., 2003; van der Vossen et al., 2003). It remains to be seen if the use of these broad-spectrum late blight R genes is durable under conditions of large-scale agricultural production because races of the pathogen that were able to overcome these genes emerged within a few years after market introduction (Turkensteen, 1993).

During the past few years, efforts have been made to generate transgenic plants that express the introduced gene under controlled conditions only. Successful approaches satisfy for this point; disease-resistant transgenic tobacco was produced by expressing pathogen elicitor-related genes fused to plant-inducible promoter (Keller et al., 1999; Rizhsky and Mittler, 2001; Takakura et al., 2004). But expression of microbial genes in genetically modified crops has provoked public concern, or these promoters are responsive not only to pathogen attack but also to wounding. We suggest that by using the pathogen-inducible PVS3 promoter and a constitutively active allele of the master switch, StMEK1, we can sufficiently enhance the defense response elicited during a compatible interaction to provide potato late blight resistance without the deleterious consequences of constitutive defense expression.

Transgenic Plants Resistant to Both Necrotrophic and Biotrophic Pathogens

Plants have evolved the complex and sophisticated defense systems to withstand a variety of pathogens (Greenberg and Yao, 2004). It has been known for a long time that infection attempts of microbial pathogens on plants trigger a complex set of defense responses requiring activation of distinct signaling pathways. Plant defense needed to be adapted to two different types of pathogen. Necrotrophs are pathogens that produce toxic enzymes and metabolites that kill the tissue directly upon invasion. In contrast, biotrophs initially feed on plants parasitically, keeping the cells in infected plant tissue alive for a significant fraction of the pathogen's life cycle (Stuiver and Custers, 2001). Necrotrophic pathogens induce pathogenesis-related genes via a jasmonic acid (JA)-dependent pathway, whereas hemibiotrophic and biotrophic pathogens induce an SA-dependent pathway. It has shown that coi1-1, a MeJA-insensitive mutant unable to induce basic-PR genes on pathogen challenge, is more susceptible than wild-type plants to infection by the necrotrophic pathogens Alternaria brassicicola and Botrytis cinerea, but not biotrophic pathogen Hyaloperonospora parasitica. In contrast, SA-deficient NahG plants, which show enhanced susceptibility to H. parasitica and P. syringae, do not have any effects on the fungal pathogens A. brassicicola and B. cinerea (Thomma et al., 1998). Because of the antagonistic effect of SA and JA on the expression of pathogenesis-related genes (Niki et al., 1998), resistance to necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens seems to conflict. Moreover, activation of ethylene responses by ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR 1 overexpression in Arabidopsis confers resistance to necrotrophic fungi B. cinerea and Plectosphaerella cucumeria, but reduces tolerance against P. syringae pv tomato DC3000 (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002). These results suggest that negative crosstalk between ethylene and SA-signaling pathways, and that positive and negative interactions between both pathways, can be established depending on the type of pathogen. Here we demonstrated that the transgenic plants harboring PVS3::StMEK1DD resistant to both necrotrophic pathogen A. solani and biotrophic pathogen P. infestans. The expression of endogenous StMEK1DD might cause the up-regulation of defense-related genes involved in distinct JA-dependent and SA-dependent signaling pathways. In fact, transgenic tobacco plants in which the WIPK gene was constitutively expressed accumulated JA at a high level and exhibited induction of gene for JA-inducible proteinase inhibitor II (Seo et al., 1999).

MAPK Cascade Is Involved in the Induction Process of PVS3 Promoter by INF1

Perception of pathogen by plant cells triggers rapid defense responses via a number of signal transduction pathways. The interaction between transcription factors and cis-acting regulatory sequences presented in plant promoters is a key step involved in the regulation of plant gene expression. cis-Acting elements within the promoters of many of these genes have recently been defined, and investigators have started to isolate their cognate trans-acting factors. To identify the cis-acting elements and cognate trans-acting factors is a first step of elucidation of signal transduction mechanism. Transient expression experiments of the N. benthamiana-Agrobacterium system suggest that cis-element, which is activated by both StMEK1DD and INF1, exists in a 50-bp region of the PVS3 promoter (positions −1,337 to −1,287; Fig. 5). These results suggest that MAPK cascade is involved in the induction process of PVS3 promoter by INF1. INF1 is an elicitor derived from P. infestans and is known to activate SIPK and WIPK in N. benthamiana (Sharma et al., 2003). In contrast to strains of P. infestans that produce elicitin INF1, strains that are engineered to be deficient in INF1 induce disease lesions on N. benthamiana, suggesting that INF1 functions the same as PAMPs that condition resistance in this species (Kamoun et al., 1998). In addition, HWC elicitor or arachidonic acid, a lipid elicitor, of the pathogen also activated StMPK1 activity (Katou et al., 1999) and PVS3 promoter (data not shown) in potato plants. Taken together, PAMPs of P. infestans may contribute to the activation of MAPK and the PVS3 promoter in the compatible interactions (Fig. 6).

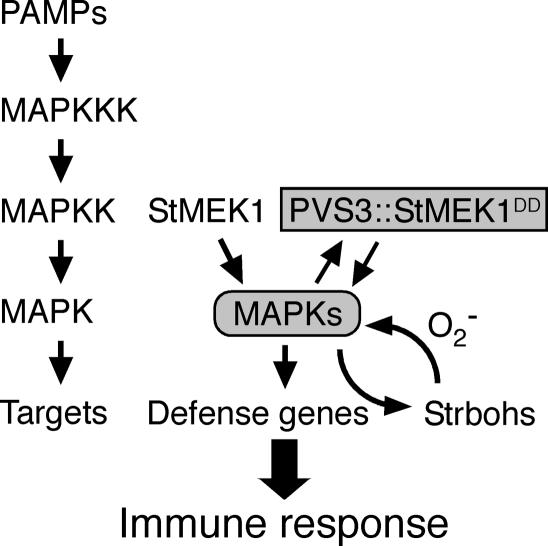

Predicted Mechanism of Defense Responses in Transgenic Potato Plants

Figure 9 shows a hypothetical mechanism of enhanced immune response in the transgenic potato plants in response to pathogen attack. In the absence of pathogens, the transgenic plant displayed normal phenotype similar to that of wild type because transgene was not induced and little increase in MAPK activity can be detected in transgenic plant. In contrast, infection with virulent pathogen induces endogenous MAPKs (StMPK1 and StWIPK) to some extent. Following the activation of MAPK, the PVS3 promoter is induced, and then StMEK1DD driven by PVS3 promoter is expressed. This creates a positive feedback genetic circuit because StMEK1DD induces phosphorylation of MAPKs and enhancing its own induction, resulting in long-lasting activation of MAPKs. The kinetics of SIPK activation in response to abiotic stresses is transient, whereas biotic elicitors that induce cell death result in prolonged activation (Zhang and Klessig, 1998). Conditional gain-of-function studies have shown that SIPK overexpression is sufficient to induce both defense gene expression and cell death (Zhang and Liu, 2001). The activation of MAPKs by StMEK1DD induces a large array of defense genes, including StrbohC and StrbohD. Generation of ROS is considered to be an important component for triggering defense responses in plants (Doke, 1983; Dietrich et al., 1996; Jabs et al., 1996; Lamb and Dixon, 1997; Orozco-Cardenas et al., 2001). It has been shown that rboh is plant NADPH oxidase that generates ROS (Groom et al., 1996; Desikan et al., 1998; Keller et al., 1998; Simon-Plas et al., 2002; Torres et al., 2002; Sagi et al., 2004). Recent works provided evidence for the involvement of a MAPK cascade in the regulation of rboh (Taylor et al., 2001; Yoshioka et al., 2003). Surprisingly StrbohB, an elicitor-inducible gene in potato tubers (Yoshioka et al., 2001), was not up-regulated in transgenic leaves. We isolated two rboh cDNAs, StrbohC and StrbohD, from potato leaves using sequence information from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) whitefly-induced gene 1 or NbrbohB of N. benthamiana, respectively. Both genes were induced in infected transgenic plants, suggesting that StrbohC and StrbohD may be responsible for the oxidative burst in response to the pathogen attack in the leaves. These results indicate enhanced MAPK activity altered the pattern of rboh gene expression (Fig. 8C). It was demonstrated that H2O2 triggers activation of SIPK and WIPK orthologs through the OXIDATIVE SIGNAL-INDUCIBLE 1 kinase in Arabidopsis (Rentel et al., 2004). Here we demonstrated that this activation circuit may induce HR and could confer disease resistance if appropriately rewired as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of mechanism of immune responses in transgenic potato plants. PAMPs derived from pathogenic microorganisms activate endogenous MAPKs (StMPK1 and StWIPK) to some extent. Following the activation of MAPKs, StMEK1DD driven by PVS3 promoter is expressed. The expression of StrbohC and StrbohD by MAPKs produces H2O2 that triggers activation of MAPKs. These create positive feedback genetic circuits resulting in long-lasting activation of MAPKs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions

Potato plants (Solanum tuberosum) and Nicotiana benthamiana were grown at 20°C or 25°C, respectively, with 70% humidity under a 16-h photoperiod and an 8-h-dark period in biotron or environmentally controlled growth cabinets.

Pathogen Inoculation

Races 0 and 1.2.3.4 of Phytophthora infestans were maintained on susceptible potato (cv Irish cobbler) tubers. Suspensions of Phytophthora zoospores were prepared as described previously (Yoshioka et al., 2003). Zoospores were applied to the attached leaves under high humidity at 20°C. In the case of RNA and protein isolation, potato leaves were inoculated with 1 × 104 zoospores mL−1 using a lens paper to disperse the zoospores. Alternaria solani and Alternaria alternata Japanese pear (Pyrus serotina Rehd.) pathotype were grown on oatmeal agar for 5 d. Aerial mycelia on the 5-d-old cultures were washed off by rubbing mycelial surfaces with cotton balls. Cultures were exposed to Black Light Blue light at 25°C for 4 d to induce sporulation. The produced conidia were suspended in water and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 105 spores mL−1.

Methyl-Umbelliferyl-β-d-Glucuronide Assays

GUS activity was assayed in tissue extracts by fluorometric quantitation of 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) produced from the glucuronide precursor using a standard protocol (Jefferson et al., 1987). GUS activity was expressed in nanomoles of product generated per minute per milligram of protein.

GUS Staining

Histochemical localization of GUS activity in situ was performed by vacuum infiltration with a solution consisting of 50 mm sodium phosphate and 0.5 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronide mL−1, and incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Leaf discs containing the inoculum were excised and then fixed on the filter paper by immersion in a 3:1 solution of ethanol:acetic acid. The fixed samples were stained carefully with 0.1 μg mL−1 trypan blue solution to avoid washing spores away, and then examined by microscopy for plant responses and growth of pathogens. Alternatively, samples were fixed with lactophenol, then destained and viewed in 2.5 g mL−1 chloral hydrate solution (Wilson and Coffey, 1980) on an Olympus BX51 microscope under either bright-field illumination or differential interference contrast.

DNA Constructs and Seedling Infection for VIGS

A 230-bp fragment of NbSIPK and a 178-bp fragment of NbWIPK, each starting from the ATG codon, were subcloned into a PVX vector pGR106 (Ratcliff et al., 2001). Additionally, both fragments were ligated in tandem into pGR106 for dual silencing. The constructs contained these inserts in the antisense orientation and were designated PVX-NbWIPK (PVX:W), PVX-NbSIPK (PVX:S), and PVX-NbSIPK/WIPK (PVX:S/W) dual-silencing insert. PVX that does not contain any inserts was used as a control. Second leaves of 2-week-old N. benthamiana seedlings were inoculated with Agrobacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens) GV3101 harboring PVX constructs using needleless syringe. After an additional 2 to 3 weeks, the fourth and fifth leaves above the inoculated leaves of each plant were analyzed for transcript levels and used for Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression (agroinfiltration).

Isolation of PVS Genomic Clones

Approximately 6.0 × 105 recombinant plaques of a potato genomic library (CLONTECH) were screened using a 32P-labeled PVS1 cDNA probe (Yoshioka et al., 1999). Types of isogenes of first-screened positive phage clones were identified by PCR with PVS1 to 4-specific primer pairs used for reverse transcriptase-mediated (RT)-PCR (see below). The representative phage clones of each isogene were purified. The only gene for PVS2 was not obtained. The XhoI-digested DNA fragments of each phage clone were subcloned into pBluescript KS (+) (Stratagene) and sequenced. The clone, which includes the longest PVS3 promoter, was selected for further analysis. All cloning and DNA-blotting procedures were performed as described previously (Sambrook et al., 1989).

Generation of Transgenic Plants

Potato plants (cv Sayaka carrying R1 and R3) were transformed with PVS3::GUS or PVS3::StMEK1DD construct. The PVS3 promoter up to −2,648 bp that includes 30 nucleotides of PVS3 open reading frame was amplified by PCR and introduced into the HindIII and SpeI sites of pBluescript SK (−) (Stratagene). S-Tag and StMEK1DD fusion or GUS gene were amplified by PCR and cloned into the SpeI and SmaI sites of pBluescript SK (−). This HindIII and SmaI cDNA fragment was amplified and Nos-terminator of pBI121 (CLONTECH) was amplified with SmaI and EcoRI sites, and introduced into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pGreen0029 (Hellens et al., 2000). The constructs were verified by sequencing. Stable transgenic lines were generated with the Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer procedure. Independent transformed plant pools were kept separate for the selection of independent transgenic lines based on their kanamycin resistance.

Construction of the PVS3::GUSint Gene and Its Deletion

The plasmid pPVS3-1 was constructed by inserting the PVS3 promoter fragment into the EcoR1-ClaI sites of the pGreen0229 binary vector (Hellens et al., 2000). The promoter fragments were generated by PCR. The initial PVS3::GUSint construct contained a 2,334-bp promoter region including the 5′-untranslated region, the initiator ATG, and the first 10 amino acid residues from PVS3 fused in-frame with a GUSint coding sequence, which carried an intron. The terminator sequence from the nopaline synthase gene flanks the 3′ end of the GUS gene. The 5′ deletions of the PVS3 promoter were produced by PCR using appropriate primers. The sequence integrity of the final constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

H2O2 Detection by the 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine Uptake Method

To visualize H2O2 in the infection site of P. infestans or A. solani, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining was performed as described by Thordal-Christensen et al. (1997). Potato leaves were inoculated with 1 × 104 Phytophthora zoospores mL−1 or 1 × 105 A. solani spores mL−1 using a lens paper. Detached leaf samples were collected at 8 h after incubation with 1 mg mL−1 DAB solution. Leaves were then fixed on the filter paper by immersion in a 3:1 solution of ethanol:acetic acid.

In-Gel Kinase Assay

In-gel kinase assays were performed as described previously (Katou et al., 2003). Briefly, the protein extracts (20 μg) were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel polymerized in the presence of MBP 0.25 mg mL−1 (Sigma). After electrophoresis, SDS was removed by washing the gel in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 20% 2-propanol, four times for 30 min each. After equilibration in buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol), the proteins were denatured at room temperature in buffer A containing 6 m guanidine twice for 30 min each time. They were renatured overnight at 4°C by incubating the gel in buffer A containing 0.03% Tween 20 with four changes of the solution. After equilibration in 20 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 10 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, the gel was incubated in the same buffer containing 25 μm ATP and 0.5 μCi mL−1 [γ-32P]ATP (4,000 Ci mmol−1) for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by washing the gel in 5% trichloroacetic acid and 1% sodium pyrophosphate. The gel was washed extensively with this solution, dried under vacuum, and autoradiographed with an intensifying screen.

RT-PCR

Total RNA samples were prepared from wild-type or transgenic plants and used for RT-PCR as templates. Gene-specific primers of each sequence were as follows: PVS1 (176 bp; 5′-CATCGATTGTTTTGTACATCT-3′, 5′-AATAATGATACAAAAAAAAATTAAGG-3′), PVS2 (132 bp; 5′-TATCAATTCACCAAGGAACACT-3′, 5′-GAAGTAATTAAATTTAAATATTATCAA-3′), PVS3 (326 bp; 5′-TTGTCTGCTGCTGCTTGTGG-3′, 5′-TCTCCATGAGTCCTTACATG-3′), PVS4 (131 bp; 5′-CATCCCTTAAAATTATAAGTATTC-3′, 5′-AATAATGATACAAAATAAATTAAGG-3′), StMEK1DD transgene (527 bp; 5′-ATGAAAGAAACCGCTGCTGCTAAATT CGAA-3′, 5′-ATATCGTGACACCTAACGACGTTAGGGTTG-3′), and EF-1α (621 bp; 5′-CACATCAGCATTGTGGTCATTGGCCACGT-3′, 5′-TCCCTTGTACCAGTCGAGGTTGGTAGACC-3′).

RNA Gel-Blot Hybridization

Total RNA was extracted from wild-type or transgenic plants. Total RNA (10 μg) was fractionated by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose-formaldehyde gel. The separated RNA was transferred from the agarose gel to a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham). The membrane was incubated for 2 h at 42°C in 50% (v/v) formamide, 5× Denhardt's solution, 5× sodium chloride/sodium phosphate/EDTA (SSPE; 1× SSPE; 10 mm NaH2PO4, pH 7.7, 180 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA), 0.5% SDS, and denatured salmon sperm DNA 200 μg mL−1. Hybridization was performed overnight under the same conditions with the addition of 32P-labeled fragments of the probe. The probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a random-primed DNA labeling kit (Megaprime; Amersham). Final washing was performed in 4× SSPE and 0.1% SDS at 65°C.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AB062138, AB022598, AB022719, AB022720, AB023816, L04680, U20187, AJ005588, AB198716, and AB198717 for StMPK1, PVS1, PVS2, PVS3, PVS4, TEAS, HVS, PEAS, StrbohC, and StrbohD, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We deeply thank David C. Baulcombe of Sainsbury Laboratory for providing PVX vector pGR106; Philip M. Mullineaux and Roger P. Hellens of John Innes Centre for pGreen binary vectors; Klaus Hahlbrock of Max-Planck-Institute for potato Phe ammonia-lyase cDNA; Joseph Chappell of University of Kentucky for EAS cDNA; Sophien Kamoun of Ohio State University for INF1 elicitor; Nam-Hai Chua of Rockefeller University for pER8 vector; the Leaf Tobacco Research Center, Japan Tobacco, for N. benthamiana seeds; Takashi Tsuge of Nagoya University for A. solani strain A-17 and A. alternata Japanese pear pathotype strain 15A; and Motoyuki Mori of NARCH for valuable suggestions. We also thank Naoki Ikeda, Miki Yoshioka, and the Radioisotope Research Center, Nagoya University, for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists; by the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [S], grant no. 14104004); and by the Research for the Future Program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area [A]).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Hirofumi Yoshioka (hyoshiok@agr.nagoya-u.ac.jp).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.105.074906.

References

- Alexander D, Goodman RM, Gut-Rella M, Glascock C, Weymann K, Friedrich L, Maddox D, Ahl-Goy P, Luntz T, Ward E, et al (1993) Increased tolerance to two oomycete pathogens in transgenic tobacco expressing pathogenesis-related protein 1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 7327–7331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu W-L, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J (2002) MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415: 977–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back K, Chappell J (1995) Cloning and bacterial expression of a sesquiterpene cyclase from Hyoscyamus muticus and its molecular comparison to related terpene cyclases. J Biol Chem 270: 7375–7381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back K, Chappell J (1996) Identifying functional domains within terpene cyclases using a domain-swapping strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 6841–6845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Lobo M, Molina A, Solano R (2002) Constitutive expression of ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1 in Arabidopsis confers resistance to several necrotrophic fungi. Plant J 29: 23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling SA, Guo A, Cao H, Gordon AS, Klessig DF, Dong X (1994) A mutation in Arabidopsis that leads to constitutive expression of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6: 1845–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broglie K, Chet I, Holliday M, Cressman R, Biddle P, Knowlton S, Mauvais J, Broglie R (1991) Transgenic plants with enhanced resistance to the fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Science 254: 1194–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Li X, Dong X (1998) Generation of broad-spectrum disease resistance by overexpression of an essential regulatory gene in systemic acquired resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6531–6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona MJ, Molina A, Fernandez JA, Lopez-Fando JJ, Garcia-Olmedo F (1993) Expression of the α-thionin gene from barley in tobacco confers enhanced resistance to bacterial pathogens. Plant J 3: 457–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JDG (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R, Burnett EC, Hancock JT, Neill SJ (1998) Harpin and hydrogen peroxide induce the expression of a homologue of gp91-phox in Arabidopsis thaliana suspension cultures. J Exp Bot 49: 1767–1771 [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich RA, Richberg MH, Schmidt R, Dean C, Dangl JL (1996) A novel zinc finger protein is encoded by the Arabidopsis LSD1 gene and functions as negative regulator of plant cell death. Cell 88: 685–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doke N (1983) Involvement of superoxide anion generation in the hypersensitive response of potato tuber tissues to infection with an incompatible race of Phytophthora infestans and to the hyphal wall components. Physiol Plant Pathol 23: 345–357 [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich L, Lawton K, Dietrich R, Willits M, Cade R, Ryals J (2001) NIM1 overexpression in Arabidopsis potentiates plant disease resistance and results in enhanced effectiveness of fungicides. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 1114–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Tang D, Innes RW (2001) Negative regulation of defense responses in plants by a conserved MAPKK kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 373–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gómez L, Boller T (2000) FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the reception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell 5: 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JT, Yao N (2004) The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant-pathogen interactions. Cell Microbiol 6: 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groom QJ, Torres MA, Fordham-Skelton AP, Hammond-Kosack KE, Robinson NJ, Jones JDG (1996) rbohA, a rice homologue of the mammalian gp91phox respiratory burst oxidase gene. Plant J 10: 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hain R, Reif HJ, Krause E, Langebartels R, Kindi H, Vornam B, Wiese W, Schmeizer E, Schreier PH, Stocker RH, et al (1993) Disease resistance results from foreign phytoalexin expression in a novel plant. Nature 361: 153–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Edwards AE, Leyland NR, Bean S, Mullineaux PM (2000) pGreen: a versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol 42: 819–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs T, Dietrich RA, Dangl JL (1996) Initiation of runaway cell death in an Arabidopsis mutant by extracellular superoxide. Science 273: 1853–1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW (1987) GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J 6: 3901–3907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Liu Y, Yang K-Y, Kim CY, Baker B, Zhang S (2003) Function of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in N gene-mediated resistance in tobacco. Plant J 33: 719–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun S, van West P, de Jong AJ, de Groot KE, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Govers F (1997) A gene encoding a protein elicitor of Phytophthora infestans is down-regulated during infection of potato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 10: 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun S, van West P, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Groot KE, Govers F (1998) Resistance of Nicotiana benthamiana to Phytophthora infestans is mediated by the recognition of the elicitor protein INF1. Plant Cell 10: 1413–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katou S, Senda K, Yoshioka H, Doke N, Kawakita K (1999) A 51 kDa protein kinase of potato activated with hyphal wall components from Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell Physiol 40: 825–831 [Google Scholar]

- Katou S, Yamamoto A, Yoshioka H, Kawakita K, Doke N (2003) Functional analysis of potato mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, StMEK1. J Gen Plant Pathol 69: 161–168 [Google Scholar]

- Katou S, Yoshioka H, Kawakita K, Rowland O, Jones JDG, Mori H, Doke N (2005) Involvement of PPS3 phosphorylated by elicitor-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in the regulation of plant cell death. Plant Physiol 139: 1914–1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, Pamboukdjian N, Ponchet M, Poupet A, Delon R, Verrier J-L, Roby D, Ricci P (1999) Pathogen-induced elicitin production in transgenic tobacco generates a hypersensitive response and nonspecific disease resistance. Plant Cell 11: 223–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller T, Damude HG, Werner D, Doerner P, Dixon RA, Lamb C (1998) A plant homolog of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase gp91phox subunit gene encodes a plasma membrane protein with Ca2+ binding motifs. Plant Cell 10: 255–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C, Dixon RA (1997) The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48: 251–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligterink W, Kroj T, zur Nieden U, Hirt H, Scheel D (1997) Receptor-mediated activation of a MAP kinase in pathogen defense of plants. Science 276: 2054–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Raghothama KG, Hasegawa PM, Bressan RA (1994) Osmotin overexpression in potato delays development of disease symptoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 1888–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Martin-Hernandez AM, Peart JR, Malcuit I, Baulcombe DC (2003) Virus-induced gene silencing in plants. Methods 30: 296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke FLH, van Pelt JA, Pieterse CMJ, Klessig DF (2004) Silencing of the mitogen-activated protein kinase MPK6 compromises disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Pitzschke A, Hirt H (2005) Emerging MAP kinase pathways in plant stress signalling. Trends Plant Sci 10: 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki T, Mitsuhara I, Seo S, Ohtsubo N, Ohashi Y (1998) Antagonistic effect of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid on the expression of pathogenesis-related (PR) protein genes in wounded mature tobacco leaves. Plant Cell Physiol 39: 500–507 [Google Scholar]

- Oba K, Kondo K, Doke N, Uritani I (1985) Induction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase in potato tubers after slicing, fungal infection or chemical treatment, and some properties of the enzyme. Plant Cell Physiol 26: 873–880 [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Cardenas ML, Narvaez-Vasquez J, Ryan CA (2001) Hydrogen peroxide acts as a second messenger for the induction of defense genes in tomato plants in response to wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell 13: 179–191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CM, Berry JO, Bruenn JA (1996) High-level secretion of a virally encoded anti-fungal toxin in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Mol Biol 30: 359–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JE (2003) Plant recognition of microbial patterns. Trends Plant Sci 8: 245–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff F, Martin-Hernandez AM, Baulcombe DC (2001) Tobacco rattle virus as a vector for analysis of gene function by silencing. Plant J 25: 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Yang H, Zhang S (2002) Cell death mediated by MAPK is associated with hydrogen peroxide production in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 277: 559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentel MC, Lecourieux D, Ouaked F, Usher SL, Petersen L, Okamoto H, Knight H, Peck SC, Grierson CS, Hirt H, et al (2004) OXI1 kinase is necessary for oxidative burst-mediated signalling in Arabidopsis. Nature 427: 858–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L, Mittler R (2001) Inducible expression of bacterio-opsin in transgenic tobacco and tomato Plants. Plant Mol Biol 46: 313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeis T, Piedras P, Zhang S, Klessig DF, Hirt H, Jones JDG (1999) Rapid Avr9- and Cf-9-dependent activation of MAP kinases in tobacco cell cultures and leaves: convergence of resistance gene, elicitor, wound, and salicylate responses. Plant Cell 11: 273–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagi M, Davydov O, Orazova S, Yesbergenova Z, Ophir R, Stratmann JW, Fluhr R (2004) Plant respiratory burst oxidase homologs impinge on wound responsiveness and development in Lycopersicon esculentum. Plant Cell 16: 616–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Seo S, Sano H, Ohashi Y (1999) Jasmonate-based wound signal transduction requires activation of WIPK, a tobacco mitogen-activated protein kinase. Plant Cell 11: 289–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma PC, Ito A, Shimizu T, Terauchi R, Kamoun S, Saitoh H (2003) Virus-induced silencing of WIPK and SIPK genes reduces resistance to a bacterial pathogen, but has no effect on the INF1-induced hypersensitive response (HR) in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol Gen Genomics 269: 583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Plas F, Elmayan T, Blein J-P (2002) The plasma membrane oxidase NtrbohD is responsible for AOS production in elicited tobacco cells. Plant J 31: 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Bradeen JM, Naess SK, Raasch JA, Wielgus SM, Haberlach GT, Liu J, Kuang H, Austin-Phillips S, Buell CR, et al (2003) Gene RB cloned from Solanum bulbocastanum confers broad spectrum resistance to potato late blight. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9128–9133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staskawicz BJ, Mudgett MB, Dangl JL, Galan JE (2001) Common and contrasting themes of plant and animal diseases. Science 292: 2285–2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuiver MH, Custers JHHV (2001) Engineering disease resistance in plants. Nature 411: 865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Uehara Y, Berberich T, Ito A, Saitoh H, Miyazaki A, Terauchi R, Kusano T (2004) A subset of hypersensitive response marker genes, including HSR203J, is the downstream target of a spermine signal transduction pathway in tobacco. Plant J 40: 586–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura Y, Ishida Y, Inoue Y, Tsutsumi F, Kuwata S (2004) Induction of a hypersensitive response-like reaction by powdery mildew in transgenic tobacco expressing harpinpss. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 64: 83–89 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ATS, Kim J, Low PS (2001) Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in the signal-transduction pathways of the soya bean oxidative burst. Biochem J 355: 795–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CM, Tang S, Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JDG (2000) Comparison of the hypersensitive response induced by the tomato Cf-4 and Cf-9 genes in Nicotiana spp. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13: 465–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma BPHJ, Eggermont K, Penninckx IAMA, Mauch-Mani B, Vogelsang R, Cammue BPA, Broekaert WF (1998) Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 15107–15111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H, Zhang Z, Wei Y, Collinge DB (1997) Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants: H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J 11: 1187–1194 [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Dangl JL, Jones JDG (2002) Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkensteen LJ (1993) Durable resistance of potatoes against Phytophthora infestans. In T Jacobs, JE Parlevliet, eds, Durability of Disease Resistance. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 115–124

- van der Vossen E, Sikkema A, te Lintel-Hekkert B, Gros J, Stevens P, Muskens M, Wouters D, Pereira A, Stiekema W, Allefs J (2003) An ancient R gene from the wild potato species Solanum bulbocastanum confers broad-spectrum resistance to Phytophthora infestans in cultivated potato and tomato. Plant J 36: 867–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson UE, Coffey MD (1980) Cytological evaluation of general resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato foliage. Ann Bot (Lond) 45: 81–90 [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Shortt BJ, Lawrence EB, Léon J, Fitzsimmons KC, Levine EB, Raskin I, Shah DM (1997) Activation of host defense mechanisms by elevated production of H2O2 in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol 115: 427–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Shortt BJ, Lawrence EB, Levine EB, Fitzsimmons KC, Shah DM (1995) Disease resistance conferred by expression of a gene encoding H2O2-generating glucose oxidase in transgenic potato plants. Plant Cell 7: 1357–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Katou S, Yoshioka H, Doke N, Kawakita K (2003) Nitrate reductase, a nitric oxide-producing enzyme: induction by pathogen signals. J Gen Plant Pathol 69: 218–229 [Google Scholar]

- Yang K-Y, Liu Y, Zhang S (2001) Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in disease resistance in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 741–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S, Mei L, Newman J, Back K, Chappell J (1997) Regulation of sesquiterpene cyclase gene expression: characterization of an elicitor- and pathogen-inducible promoter. Plant Physiol 115: 437–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Numata N, Nakajima K, Katou S, Kawakita K, Rowland O, Jones JDG, Doke N (2003) Nicotiana benthamiana gp91phox homologs NbrbohA and NbrbohB participate in H2O2 accumulation and resistance to Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell 15: 706–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Sugie K, Park H-J, Maeda H, Tsuda N, Kawakita K, Doke N (2001) Induction of plant gp91 phox homolog by fungal cell wall, arachidonic acid, and salicylic acid in potato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 725–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Yamada N, Doke N (1999) cDNA cloning of sesquiterpene cyclase and squalene synthase, and expression of the genes in potato tuber infected with Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell Physiol 40: 993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler D, Zähringer U, Gerber I, Dubery I, Hartung T, Bors W, Hutzler P, Durner J (2004) Innate immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana: Lipopolysaccharides activate nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and induce defense genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15811–15816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Klessig DF (1998) The tobacco wounding-activated MAP kinase is encoded by SIPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7225–7230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Liu Y (2001) Activation of salicylic acid-induced protein kinase, a mitogen-activated protein kinase, induces multiple defense responses in tobacco. Plant Cell 13: 1877–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Navarro L, Oakeley EJ, Jones JDG, Felix G, Boller T (2004) Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 248: 764–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook MN, Kuc JA (1991) Induction of sesquiterpene cyclase and suppression of squalene synthetase activity in elicitor treated or fungal infected potato tuber tissue. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 39: 377–390 [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J, Niu Q-W, Chua N-H (2000) An estrogen receptor-based transactivator XVE mediates highly inducible gene expression in transgenic plants. Plant J 24: 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]