Abstract

The function of the 5′ region of the upstream regulatory region (URR) in regulating E6/E7 expression in cancer-associated papillomaviruses has been largely uncharacterized. In this study we used linker-scanning mutational analysis to identify potential cis regulatory elements contained within a portion of the 5′ region of the URR that are involved in regulating transcription of the E6/E7 promoter at different stages of the viral life cycle. The mutational analysis illustrated differences in the transcriptional utilization of specific regions of the URR depending on the stage of the viral life cycle. This study identified (i) viral cis elements that regulate transcription in the presence and absence of any viral gene products or viral DNA replication, (ii) the role of host tissue differentiation in viral transcriptional regulation, and (iii) cis regulatory regions that are effected by induction of the protein kinase C pathway. Our studies have provided an extensive map of functional elements in the 5′ region (nuncleotides 7259 to 7510) of the human papillomavirus type 31 URR that are involved in the regulation of p99 promoter activity at different stages of the viral life cycle.

Cancer of the cervix is the most common cancer in developing countries and the second most common malignancy in women worldwide (40). Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) have been associated with over 90% of all cervical cancers examined, and HPV types that are associated with an increased risk of cervical malignancy include types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 (8, 15, 55). The E6 and E7 genes of these high-risk HPVs encode oncoproteins which interact with the cell cycle regulatory proteins p53 and retinoblastoma protein, respectively (19, 59). The E6/E7 promoter (known as p99 in HPV31) is regulated by cis-acting elements located in the upstream regulatory region (URR) of the viral genome (24, 29, 31, 49). As the rate of viral transcription controlled by the URR is a major determinant of E6 and E7 levels, considerable effort has been made to delineate sequences that are important for the transcriptional regulation of the E6 and E7 oncogenes and to identify the cellular factors that interact with these elements.

The activity of the E6/E7 promoter is regulated by a complex interplay of cellular and viral factors that bind to the URR. These factors act as either inducers or repressors of transcription depending on the state of differentiation of the host cell, the stage of the viral life cycle, and the particular combination of cellular and viral factors involved (1, 2, 45, 51). In identifying cis elements that regulate E6/E7 expression, attention has largely been focused on the sequences that are immediately proximal of the E6/E7 transcription start site. A number of cellular transcription factors, including AP-1 family members, AP-2, CCAAT displacement factor, C/EBP, GRE, KRF-1, Oct-1, Sp1, Sp3, TEF-1, and YY1, have been reported to contribute to HPV E6/E7 gene regulation (3, 4, 20, 22, 27, 28, 34, 46, 70, 74). The viral E2 protein is a major regulator of transcriptional control and has been shown by others to function primarily as a repressor of E6 and E7 expression (7, 10, 12, 56). Transcriptional regulation by the E2 protein is facilitated by its binding as a dimer to the conserved palindromic sequence ACCN6GGT, known as the E2 binding site (E2BS) (18, 41). The distribution and locations of the four E2BS in the URR of genital HPVs are highly conserved.

In HPV31, the epithelial cell-specific keratinocyte enhancer (nucleotides [nt] 7495 to 7789) is the major transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 expression (24). The activity of the keratinocyte enhancer is regulated through a synergistic interaction of AP-1 with cellular factors (31). Directly upstream of the keratinocyte enhancer is an auxiliary enhancer domain, comprised of TEF-1 and YY1 binding sites, that augments keratinocyte enhancer function (29). The function of the remaining 5′ URR region of HPV31 in regulating early viral gene expression has been largely uncharacterized (29) (Fig. 1). Previous studies with low-risk HPV6 have identified negative regulatory sequences in this region that bind the CCAAT displacement factor (54). Recently, a nuclear matrix attachment region was mapped to the 5′ domain in HPV16 (68). Since little else is known about the cis elements contained within the 5′ portion of the URR that controls gene expression from the E6/E7 promoter, we analyzed a portion of this region in the URR of HPV31 to delineate potential cis regulatory regions.

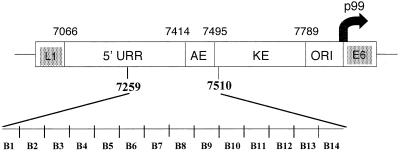

FIG. 1.

Map of the HPV31 URR, located between the end of the late gene L1 and the start of the early gene E6, showing the 252-bp region (nt 7259 to 7510) replaced in 14 linker-scanning mutants. The positions of known URR elements such as the 5′ URR domain (nt 7066 to 7413), auxiliary enhancer domain (AE, nt 7414 to 7494), keratinocyte enhancer element (KE, nt 7495 to 7789), the minimal origin of DNA replication (ORI), and the p99 promoter where the E6/E7 transcripts originate are shown. B1 to B14 represent consecutive 18-bp sequences replaced with the NdeI-ApaI-BclI polylinker to generate the mutants described in this study.

The life cycle of HPV is tightly linked to the differentiation state of its natural host tissue, the squamous epithelium. Transcription of HPVs is regulated in a complex manner according to the infected epithelial cell type, the differentiated state of the host, the physiological state of the host, the stage in the viral life cycle, and the episomal or chromosomally integrated state of the viral genome. Despite the extensive studies already performed to identify transcriptional regulatory regions in the URR, there has been no systematic mutational analysis of the URR, particularly in the 5′ portion.

In this study, we systematically analyzed the 5′ region of the URR spanning nt 7259 to 7510 by sequentially replacing 18-bp sequences with a polylinker to generate 14 linker-scanning mutants. To understand how HPV transcription is regulated during its differentiation-dependent life cycle, we used these linker-scanning mutants to define areas of the 5′ URR important for the control of transcriptional activity at different stages of the viral life cycle. The results obtained in this study identified viral cis elements with a transcriptional regulatory role in model systems that represent early and late stages of the viral life cycle. Our mutational analysis has illustrated the differences in the transcriptional utilization of specific regions of the URR depending on the state of the viral life cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and oligonucleotides.

A 1,112-bp sequence (nt 6921 to 121) encompassing the complete URR of HPV31 was amplified by PCR using complementary primers containing a 5′ KpnI site and a 3′ HindIII site. The 1,112-bp amplified sequence was digested with KpnI and HindIII and cloned into the pGL2 Basic vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.) upstream of the firefly luciferase reporter gene. Using this nt 6921 to 121 URR wild-type construct, 18-bp linker-scanning mutations were introduced within the URR by the method described previously (58, 61, 62, 73). A schematic representation of the construction of linker-scanning mutants is shown in Fig. 2. Two external primers, common to all mutants, were synthesized; one complementary to sequences 5′ of the KpnI site (α) and the other complementary to the sequence 3′ of the HindIII site (β) of the pGL2 Basic vector. The sequences of the α and β primers are 5′-CGCGGTACCCGGGGATCCTCTAGAGTCGAC-3′ and 5′-CGCAAGCTTGCCTGCAGG ATTTTTGAACAT-3′, respectively.

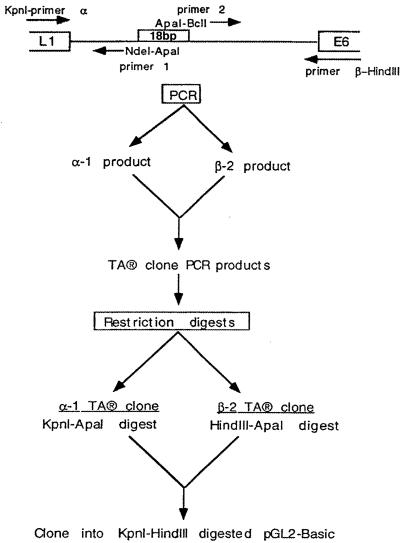

FIG. 2.

Construction of linker-scanning mutants. By using matched external and internal primers, two half products were synthesized by PCR and cloned into the pCRII vector. The two fragments were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, and appropriate fragments were then ligated into the pGL2 Basic vector upstream of the luciferase reporter gene.

To generate mutations spanning across the URR, specific sets of multiple internal primers were synthesized. The oligonucleotide primers used in the construction of the linker-scanning mutants are shown in Table 1. Primers for the 5′ half (designated 1) include CGC, 12 bases making up ApaI and NdeI sites, and 17 bases complementary to the wild-type sequence of the viral URR. Primers for the 3′ half (designated 2) include CGC, 12 bases making up ApaI and BclI sites, and 17 bases complementary to the antisense wild-type sequence of the viral URR. Using the external and matched internal primers, the two half products (α-1 and β-2) were synthesized by PCR and subsequently cloned into the pCRII vector using the TA cloning kit as per the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The 5′ product (α-1) was digested with KpnI and ApaI, and the 3′ product (β-2) was digested with ApaI and HindIII. Each fragment was gel purified, and the appropriate fragments were ligated into the pGL2 Basic vector that had been digested with KpnI and HindIII, creating mutant constructs in place of the wild-type URR sequence. The clones were sequenced to ensure that the proper sequence was maintained. We generated 14 linker-scanning mutants, designated B1 to B14, spanning nt 7259 to 7510 of the URR by replacing 18 bp of the wild-type sequence with an NdeI-ApaI-BclI polylinker as described above.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in the construction of linker scanning mutants B1 to B14

| Primer | Sequence

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 5′ half | 3′ half | |

| B1 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGTACACAACACACACAGG-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCACCTATTAGTAACATACT-3′ |

| B2 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGGTGTATATAAGGACAAC-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCATTACTATTTTATAAACT-3′ |

| B3 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGTAGTATGTTACTAATAG-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCATTGTTCCTACTTGTTCC-3′ |

| B4 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGTAGTTTATAAAATAGTA-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCAACTTGTTCCTGCTCCTC-3′ |

| B5 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGAGGAACAAGTAGGAACA-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCACAATAGTCATGTACTTA-3′ |

| B6 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGGGAGGAGCAGGAACAAC-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCATTCTGCCTATAATTTAG-3′ |

| B7 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGATAAGTACATGACTATT-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCATGTCACGCCATAGTAAA-3′ |

| B8 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGCCTAAATTATAGGCAGA-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCAGTTGTACACCCGGTCCG-3′ |

| B9 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGTTTTACTATGGCGTGAC-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCATTTTTGCAACTAAAGCT-3′ |

| B10 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGACGGACCGGGTGTACAA-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCACTCCATTTTGATTTTAT-3′ |

| B11 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGTAGCTTTAGTTGCAAAA-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCACAGCCATTTTAAATCCC-3′ |

| B12 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGCATAAAATCAAAATGGA-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCAAACCGTTTTCGGTTGCA-3′ |

| B13 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGAGGGATTTAAAATGGCT-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCATGTTTAAACATGCTAGT-3′ |

| B14 | 5′-CGCGGGCCCCATATGATGCAACCGAAAACGGT-3′ | 5′-CGCGGGCCCTGATCACAACTATGCTGATGCAG-3′ |

Cell culture.

C33A, an HPV-negative cell line derived from a cervical carcinoma, was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and gentamicin. The CIN-612 9E cell line was established from a cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade I biopsy and contains HPV31b DNA (6). In the CIN-612 clonal derivative 9E, the HPV31b genome is maintained episomally at 50 to 100 copies per cell (25). 9E cells were grown in E medium containing 5% FBS in the presence of mitomycin C-treated J2 3T3 feeder cells as previously described (36, 37, 38). Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK cells) were maintained as monolayer cultures without feeder cells in KGM-2 (Clonetics, San Diego, Calif.).

Transfection and luciferase assay.

Transfection experiments were performed with each of the above cell lines using PerFect Lipids (Pfx-8) (Invitrogen) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. At 80% confluence, cells were trypsinized and counted. A total of 2 × 105 cells were seeded per 35-mm well and incubated at 37°C for 12 to 16 h. For each transfection, 6 μl of Pfx-8 lipid was mixed with 1 μg of luciferase reporter plasmid DNA in 1 ml of KGM-2. The DNA-lipid complex was then added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 4 h, after which the transfection solution was replaced with fresh medium. The cells were incubated in their medium for an additional 48 h, at which time cell extracts were prepared with passive lysis buffer (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Luciferase activity was assayed using the luciferase assay system kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For differentiation studies, 9E and NHEK cells were transfected as described above. In the case of 9E, cells were first allowed to adhere to the wells for 3 to 4 h in E medium, after which the medium was replaced with KGM-2. The 9E cells were incubated in KGM-2 for an additional 8 h prior to transfection. Immediately following transfection, cells were switched to E medium containing 1.68% methylcellulose as described previously (57). To prepare methylcellulose, half the final volume of E medium containing 5% FBS was added to dry autoclaved methylcellulose (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and heated to 60°C for 20 min. The remaining volume, consisting of E medium containing 10% FBS, was added, and the medium was stirred overnight at 4°C.

Transfection with each construct was carried out in quadruplicate in 35-mm dishes. Four hours posttransfection, the cells were detached by incubation with trypsin-EDTA (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) at 37°C for 10 min. The trypsin was inactivated by suspending the cells in E medium containing 5% FBS. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1 ml of E medium, and the suspension was added dropwise to a 50-ml conical tube (Becton Dickinson, Piscataway, N.J.) containing 15 ml of 1.68% methylcellulose. Cells were mixed gently to ensure uniform suspension and then incubated for 48 h in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and pelleted by centrifugation. Cell extracts were prepared using the passive lysis buffer, and luciferase activity was assayed as described before.

To study the effect of induction of the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway, a 10 μM concentration of the synthetic diacylglycerol 1,2 dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol (C8; Sigma) was added to monolayer and differentiated cultures. Transfection studies and measurement of luciferase activity were carried out as described before. The effect of the URR linker-scanning mutants was determined by directly comparing the luciferase activity of the mutant construct with that of the wild-type URR construct. The relative luciferase activity of each mutant URR is expressed as fold change compared with the wild-type URR, which was set at 1.0.

Western blot analysis.

Protein extracts of 9E and NHEK cells grown in monolayer and methylcellulose cultures were made by lysing the cells with lysis buffer as described previously with some modifications (66). 9E and NHEK cells grown in monolayer culture or in methylcellulose were lysed in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The lysed cells were subjected to constant agitation at 4°C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatant was collected, and the total protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). A 30-μg amount of protein was heated in a 100°C water bath for 5 min and electrophoresed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and then incubated with either keratin-10-specific monoclonal antibody (1:2,000 dilution) (Biogenix, San Ramon, Calif.) or involucrin monoclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution) (Sigma) at 4°C overnight. Blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham Life Science, Boston, Mass.). The proteins were detected using a chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham Life Science) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

The URR of HPV31 has been divided into functional segments: a 5′ region (5′ URR domain), an auxiliary enhancer domain, the cell-specific keratinocyte enhancer element, the minimal origin, and the p99 promoter, where early viral transcripts originate (24). In HPV31, the keratinocyte enhancer (nt 7495 to 7789) is regarded as the major transcriptional activator of early viral gene expression (24). Directly upstream of the keratinocyte enhancer is an auxiliary enhancer domain (nt 7414 to 7495) that augments keratinocyte enhancer function (29). The 5′ URR domain (nt 7066 to 7414) has been shown to be dispensable for transient and stable viral replication as well as for viral DNA amplification (24).

Little is known about the cis regulatory elements in the 5′ URR domain of HPV31 that influence viral transcriptional regulation during different stages of the viral life cycle. We were interested in identifying and characterizing the potential cis regulatory elements involved in viral transcriptional control contained within a portion of the 5′ region of the URR made up by the auxiliary enhancer and 5′ URR domains. In this study, we used linker-scanning mutational analysis to define areas within the HPV31b 5′ URR region from nt 7259 to 7510, important for the induction or repression of transcriptional activity under conditions representing different stages of the viral life cycle.

Generation of linker-scanning mutants.

To investigate the role of cis regulatory elements contained within a region of the HPV31 5′ URR in regulating viral early gene expression, we constructed a series of linker-scanning mutants. We used linker substitution mutational analysis for mapping cis elements in order to maintain spatial positioning of the various cis elements involved in transcription with respect to the promoter. Consecutive 18-bp linker substitution mutations were engineered across a 252-bp stretch of the HPV31 URR (nt 7259 to 7510) as described in Materials and Methods. A map of the HPV31 URR indicating the region that has been replaced by polylinkers is shown in Fig. 1. For convenience of nomenclature, the entire URR has been divided into four regions, A, B, C, and D, each of which consists of 252 bp. The region of interest in this study, B1 to B14, is shown in Fig. 1.

cis sequences involved in viral transcriptional control have the potential to influence transcription at several levels. These include the ability to modify HPV transcription during the earliest stage of the viral life cycle, immediately following infection, when there is minimal viral replication and viral gene product expression. As monolayer keratinocyte cultures model the basal cell environment seen by the virus immediately upon infection, we first analyzed the effect of the p99 URR mutants in monolayer culture.

Identification of cis regulatory sequences modulating p99 promoter activity in monolayer culture.

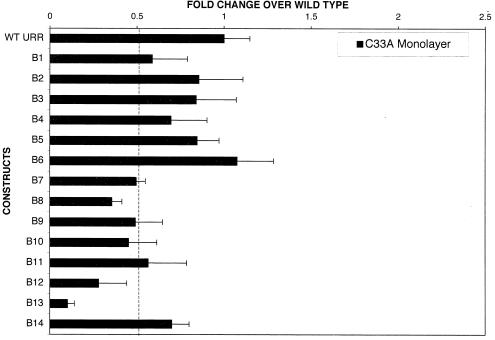

In order to identify the cis regulatory sequences that regulate transcription from the p99 promoter immediately upon infection, we carried out transfection of the wild-type construct and mutant constructs B1 to B14 in monolayer cell culture. C33A, an HPV-negative cell line derived from a cervical carcinoma, has been commonly used by numerous investigators to analyze HPV transcriptional activity. Transfection with linker-scanning mutants B12 and B13 decreased the transcriptional activity from the p99 promoter by 70 and 90%, respectively, in C33A cells, suggesting that these regions are required for normal p99 promoter activity (Fig. 3). Transfection with the B7, B8, B9, and B10 mutants showed an approximately 50% decrease in promoter activity (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional regulation of p99 promoter activity by cis regulatory elements located within a 252-bp region (nt 7259 to 7511) of the HPV31 URR in monolayer cultures of C33A cells. C33A cells were transfected with 1 μg of either the wild-type or a mutant URR luciferase reporter construct. The luciferase activity of the wild-type (WT) construct was set at 1.00. For each linker-scanning mutant B1 to B14, the luciferase activity was expressed as fold change over the activity the wild-type URR. The dashed line represents 50% of the wild-type activity. Transfection experiments were done in duplicate, and values are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of at least three individual experiments.

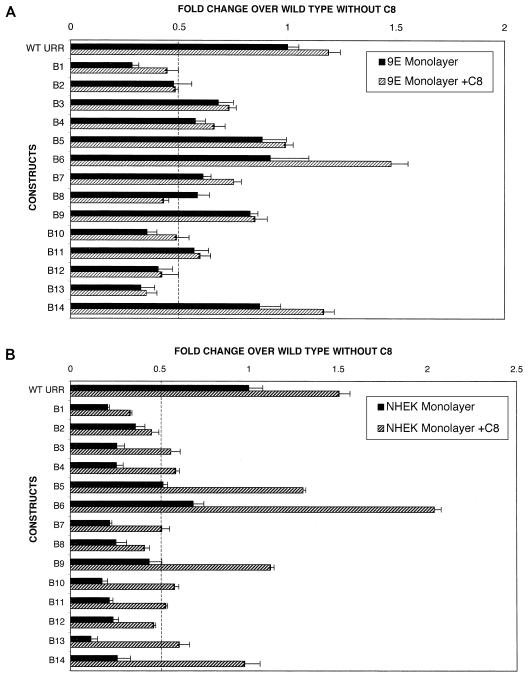

To dissect the role of viral cis elements in transcriptional regulation in the presence of viral gene products, monolayer cultures of 9E cells, which are HPV31b positive, were transfected with linker-scanning mutants B1 to B14. Similar to C33A, mutants B10, B12, and B13 resulted in a significant decrease in activity following transfection into 9E cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast to C33A, transfection of 9E cells with the B1 and B2 mutants decreased transcriptional activity by 70 and 50%, respectively, compared to the wild-type construct. Therefore, regulation of p99 promoter activity by cis elements located in the region replaced in mutants B1 and B2 is cell type specific and may be effected by the presence of viral gene products.

FIG. 4.

(A) Transcriptional regulation of p99 promoter activity in CIN-612 9E monolayer culture by linker-scanning mutants B1 to B14 in the absence and presence of the PKC inducer C8. 9E monolayer cultures were transfected with either the wild-type URR construct or linker-scanning mutants B1 to B14 as described in Materials and Methods. The fold change in promoter activity for each mutant over that with the wild-type URR was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Transfection experiments were performed in duplicate, and values are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of four individual experiments. To study the effect of induction of the PKC pathway on p99 promoter activity, following transfection with either the wild-type or a linker-scanning mutant (B1 to B14) construct, monolayer cultures of 9E cells were treated with medium containing 10 μM C8. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were harvested and the luciferase activities were assayed. The fold change in luciferase activity for each mutant over that with the wild-type construct without C8 treatment is shown (hatched bars). The dotted line represents 50% of the wild-type activity. Transfections were done in duplicate, and values are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of at least three individual experiments. (B) Transcriptional regulation of p99 promoter activity by cis regulatory elements located within a 252-bp region (nt 7259 to 7511) of the HPV31 URR in monolayer cultures of NHEK cells in the absence and presence of PKC inducer. Transfection with linker-scanning mutants was performed as for panel A. The dotted line represents 50% of the wild-type activity. Transfections were done in duplicate, and values are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of at least three individual experiments.

Analysis of transcriptional regulation by viral cis elements was also performed in NHEK cells, as they represent the initial target for HPV infection. As with C33A and 9E cells, transfection of NHEK cells with mutant B13 resulted in a significant decrease in activity relative to the wild-type construct. While transfection of NHEK cells with mutants B1, B2, B3, B4, B7, B8, B9, B10, B11, B12, and B14 decreased transcriptional activity by 60 to 70%, mutants B5 and B9 reduced activity by about 50% (Fig. 4B). The reduction in promoter activity observed upon transfection with mutants B1, B2, B3, B4, B7, B8, B10, B12, B13, and B14 suggests that the regions replaced in these mutants have a positive role in the regulation of early gene expression in the NHEK monolayer culture (Fig. 4B). NHEK cells appear to be sensitive to all the mutations analyzed, as there was a generalized repression in promoter activity upon transfection with mutants B1 through B14. Therefore it seems likely that NHEK cells are more dependent on the wild-type sequence for transcriptional activity. The difference in p99 promoter activity seen upon transfecting the three different cell types with the linker-scanning mutants suggests that a difference in the nature of the cell type and/or the presence of viral gene products influences the regulation of p99 activity by the cis elements. Transfection experiments were repeated four to six times, demonstrating highly reproducible results.

To analyze the influence of E2 on p99 promoter activity by cis elements, the E2 expression vector was cotransfected with either the wild-type or mutant constructs. It was observed that ectopic expression of E2 in both 9E and NHEK monolayer cultures resulted in greater than 90% repression of the transcriptional activity both from the wild-type and mutant URR constructs (data not shown).

Effect of a PKC pathway induction on promoter activity.

Induction of the PKC pathway not only increases the differentiation potential of HPV-infected tissues but also increases HPV virion synthesis, probably through upregulation of capsid gene expression (26, 35, 37, 47, 50). Therefore, we investigated the effect of C8, a PKC inducer, on the regulation of p99 transcriptional activity by cis elements contained in a portion of the HPV31 5′ URR during the early stages of the viral life cycle. The presence of C8 in general had no effect on transcriptional activity from the wild-type or mutant URR constructs compared to transcriptional activity in 9E monolayers grown in the absence of C8 (Fig. 4A). Treatment with C8 was also unable to restore the transcriptional repression of wild-type or mutant constructs seen with ectopic expression of E2 (data not shown). Therefore, induction of the PKC pathway in the 9E monolayer had no effect on transcriptional regulation.

A threefold increase in promoter activity was observed upon induction of the PKC pathway in NHEK cells transfected with B13 (Fig. 4B). Addition of C8 to monolayer cultures of NHEK cells transfected with B5, B6, B9, B10, and B14 resulted in an approximately twofold increase in promoter activity compared to the activity in similar transfection studies conducted in the absence of C8 (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these data suggest that in NHEK cells, induction of the PKC pathway plays a role in transcriptional regulation by modulating the cis regulatory elements contained in the regions replaced in the mutants B5, B6, B9, B10, B13, and B14. Transcriptional regulation in NHEK cells, which lack any HPV gene products, is influenced by the induction of the PKC pathway. Therefore, it seems likely that the presence of HPV gene products in 9E cells may directly or indirectly enable these cells to bypass a need for the PKC pathway.

Identification of cis elements affecting p99 promoter activity during differentiation.

Having identified the cis elements important for viral transcriptional control during the initial stages of the viral life cycle, we wanted to investigate the effect of viral cis elements on transcriptional control in differentiating host tissue in the late stages of the viral life cycle. As suspension in methylcellulose is a simple system for the induction of keratinocyte differentiation (16, 57), we used this system to discern the effect of host tissue differentiation on viral transcriptional control. Differentiation studies were done with HPV31-positive 9E cells to investigate the influence of viral gene products and viral replication on differentiation-dependent transcriptional activity. The ability of 9E cells to differentiate in methylcellulose has been well established (16, 57). Transfection of 9E cells with mutants B5, B6, and B9 with subsequent differentiation in methylcellulose resulted in an approximately 50% increase in promoter activity relative to the wild-type construct (Fig. 5A). Transfection of 9E cells with mutants B4, B7, B12, and B13 resulted in 60 to 70% reduction in activity upon differentiation compared to the wild type, while transfection with mutants B1, B2, and B14 decreased transcriptional activity by 50% upon differentiation (Fig. 5A).

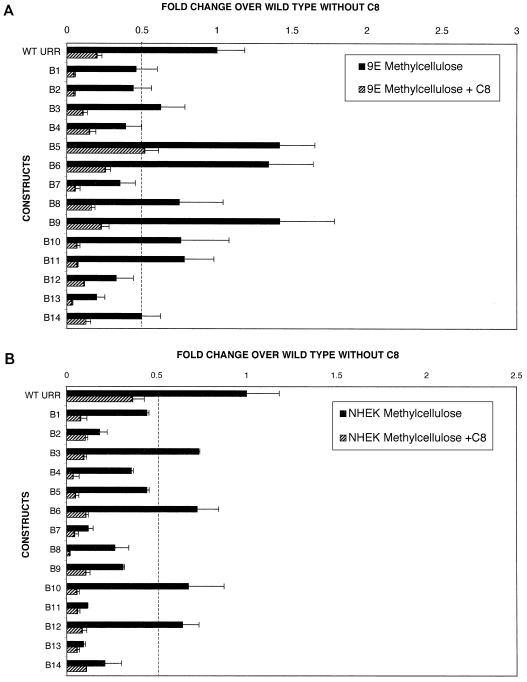

FIG. 5.

(A) Effect of host tissue differentiation on p99 transcriptional control by cis regulatory elements located within the URR in the presence and absence of the PKC inducer C8. CIN-612 9E cells were transfected as described in Materials and Methods. Following transfection, they were suspended in methylcellulose for 48 h, and cell lysates were subsequently assayed for luciferase activity. The fold change in activity for each mutant construct over that with the wild-type URR, represented by solid bars, was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Results are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of at least five to six individual experiments. To study the effect of induction of the PKC pathway on p99 promoter activity by cis elements in a differentiating system, 9E cells were transfected with either the wild-type or a mutant construct, and following transfection, they were suspended in methylcellulose containing 10 μM C8. Luciferase activity was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The effect of C8 in regulating the transcriptional activity of each mutant construct compared to the wild-type without C8 treatment is shown as hatched bars. The dotted line represents 50% of the wild-type activity. Results are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of at least four individual experiments. (B) Transcriptional regulation of p99 promoter activity by linker-scanning mutants B1 to B14 in differentiating NHEK cells. Transfection experiments and differentiation in methylcellulose were performed as described for panel A. To study the effect of C8 on the regulation of p99 promoter activity by cis elements in differentiating NHEK cells, cells were transfected with either the wild-type or a mutant construct, and following transfection, they were suspended in methylcellulose containing 10 μM C8. Fold change in promoter activity for each mutant construct in the presence of C8 was determined as described for panel A. The dotted line represents 50% of the wild-type activity. Results are expressed as the mean and standard deviations of at least five individual experiments.

To identify the specific effects that host tissue differentiation has on viral transcriptional regulation in 9E cells, the results obtained upon differentiation were compared to those from the monolayer experiments. By correlating data from the differentiating system with those obtained from the monolayer experiments, we were able to demarcate regions where transcriptional regulation is influenced by host tissue differentiation in the presence of viral gene products. Some regions replaced by the linker-scanning mutations were not affected by differentiation, as the level of transcriptional activity obtained upon transfection relative to the wild-type construct remained approximately the same between the monolayer and differentiated systems. However, transfection with other mutants increased the promoter activity by 30 to 50% upon differentiation in methylcellulose (Table 2). These studies indicate that the activities of specific cis elements are regulated differently in undifferentiated and differentiated host cell environments.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of transcriptional regulation of p99 promoter activity by linker-scanning mutants B1 to B14 in undifferentiated and differentiated CIN-612 9E cultures

| Construct | Fold change in activity vs. wild-type URR

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 9E undifferentiated | 9E differentiated | |

| Wild-type URR | 1 | 1 |

| B1 | 0.28 | 0.46 |

| B2 | 0.47 | 0.44 |

| B3 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| B4 | 0.57 | 0.39 |

| B5 | 0.88 | 1.41 |

| B6 | 0.92 | 1.34 |

| B7 | 0.61 | 0.35 |

| B8 | 0.58 | 0.75 |

| B9 | 0.83 | 1.41 |

| B10 | 0.35 | 0.76 |

| B11 | 0.57 | 0.78 |

| B12 | 0.40 | 0.33 |

| B13 | 0.32 | 0.20 |

| B14 | 0.87 | 0.49 |

NHEK cells were also transfected with the wild-type construct and linker-scanning mutant constructs and allowed to differentiate in methylcellulose. The ability of NHEK cells to differentiate in methylcellulose has also been well established (1, 57). Transfection with linker-scanning mutants B3, B6, B10, and B12 showed promoter activity similar to that with the wild-type URR construct (Fig. 5B). However, transfection with B2, B7, B11, B13, and B14 caused a substantial reduction (80 to 90%) in promoter activity compared to the wild-type construct upon differentiation. On the other hand, transfection of NHEK cells with mutants B1, B4, B5, B8, and B9 resulted in a 50 to 70% reduction in promoter activity (Fig. 5B).

The role of host tissue differentiation in viral transcriptional regulation was again evaluated by correlating data from the monolayer experiments with those obtained from the differentiation studies with NHEK cells. Though no marked change in promoter activity was observed between the differentiated and undifferentiated systems when NHEK cells were transfected with mutants B4, B5, B6, B8, B9, B13, and B14, an approximately two- to threefold increase in promoter activity compared to the monolayer culture was observed when NHEK cells transfected with mutants B1, B3, B10, and B12 were allowed to differentiate (Table 3). All transfection experiments were repeated four to six times, and the results were reproducible.

TABLE 3.

Differences in transcriptional regulation of p99 promoter activity caused by linker-scanning mutants B1 to B14 in undifferentiated and differentiated NHEK culture

| Construct | Fold change in activity vs. wild-type URR

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NHEK undifferentiated | NHEK differentiated | |

| Wild-type URR | 1 | 1 |

| B1 | 0.21 | 0.44 |

| B2 | 0.36 | 0.18 |

| B3 | 0.26 | 0.73 |

| B4 | 0.26 | 0.36 |

| B5 | 0.52 | 0.44 |

| B6 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| B7 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

| B8 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| B9 | 0.44 | 0.31 |

| B10 | 0.18 | 0.67 |

| B11 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| B12 | 0.24 | 0.64 |

| B13 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| B14 | 0.26 | 0.21 |

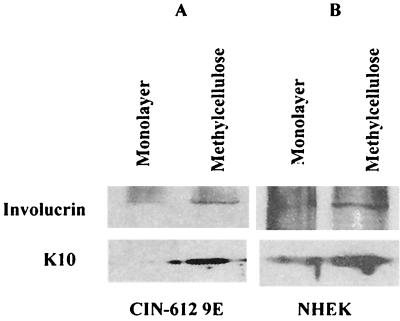

To ensure that the 9E and NHEK cells had differentiated upon suspension in methylcellulose, the expression of markers of epithelial differentiation, involucrin and K10, was analyzed. Western blot analysis revealed that compared to the monolayer culture, the expression of both K10 and involucrin was increased upon differentiation of 9E and NHEK cells in methylcellulose (Fig. 6). An increase in the expression of epithelial markers suggested that the changes in promoter activity observed upon suspension of 9E and NHEK cells in methylcellulose were related to the differentiation of the cells.

FIG. 6.

Keratinocyte differentiation markers in cells suspended in methylcellulose. Thirty micrograms of whole-cell extracts from 9E cells (A) and NHEK cells (B) grown in monolayer culture and in methylcellulose was separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and probed with antibodies to involucrin and keratin-10 (K10).

A comparison of the results obtained with 9E cells and NHEK cells provides insight into whether the presence of endogenous viral gene products and viral DNA replication influence transcriptional regulation by cis elements in a differentiating system. Though the promoter activities seen upon transfecting 9E and NHEK cells with mutants B1, B3, B4, and B10 were similar, a two- to threefold decrease in activity was observed in NHEK cells compared to the 9E cells upon transfection with mutants B5 and B9 in a differentiating system. While transfection of NHEK cells with mutant B11 resulted in a fivefold decrease in activity compared to 9E cells, transfection with mutant B12 led to an approximately 50% increase in activity in NHEK cells compared to 9E cells. Together, these data suggest a role for viral gene products and vegetative viral DNA replication in transcription during the late stages of the viral life cycle.

Induction of PKC pathway in a differentiating system.

Addition of a PKC pathway activator to the culture medium of raft tissue not only induces a more complete differentiation program but also increases HPV virion synthesis (26, 35, 37, 47, 50). We therefore investigated whether induction of the PKC pathway has any effect on promoter activity during the late stages of the viral life cycle. The induction of the PKC pathway in differentiating 9E cells significantly repressed p99 promoter activity from both the wild-type and mutant constructs (Fig. 5A). A comparison of p99 activity in the presence and absence of C8 in the differentiating system showed that addition of C8 to the differentiating medium resulted in a 70 to 80% reduction in promoter activity for most of the mutants except mutant B5, which showed an approximately 50% decrease in activity upon induction of the PKC pathway.

Differentiation of NHEK cells in the presence of C8 caused a general reduction in transcriptional activity for both the wild-type URR and all other mutant constructs (Fig. 5B). Transfection with mutant B8 decreased activity by 99%, while a 70 to 80% decrease in activity was observed for all the other mutants (Fig. 5B). Comparison of p99 promoter activity in the presence of C8 in NHEK monolayer culture versus the differentiating system revealed that C8 works differently in the two systems. While induction of the PKC pathway in monolayer culture rescues the inhibition of promoter activity for all the mutants, addition of C8 in differentiating medium resulted in a significant reduction in promoter activity. These studies indicate that the cellular environment of the infected cell at different stages of the differentiation-dependent viral life cycle plays a role in determining the effect of the PKC pathway on the regulation of cis elements located in the 5′ portion of the URR. All transfection experiments were repeated four to six times, and the results were reproducible.

DISCUSSION

The expression of the HPV E6 and E7 genes is regulated by viral and cellular factors that bind to sequences located in the URR of the viral genome. Initial studies of URR transcriptional regulation focused on the identification of DNA-protein interactions giving rise to enhancer functions. Several cellular factors, including AP-1 family members, AP-2, CDP, GRE, KRF-1, NF1, Oct-1, Sp1, Sp3, TEF-1, and YY1, have been proposed to regulate the URR of various HPV types. These factors modulate promoter activity in correlation with the nature of the infected epithelial cell (4, 11, 27), the state of differentiation (1, 14, 52), and viral feedback loops (69). In addition to the involvement of the above cellular factors in regulating HPV gene expression, it has been shown that the HPV E2 protein is capable of repressing transcription from the E6/E7 promoter (7, 10, 12, 13, 56).

While much effort has been invested in studying promoter-proximal cis-acting elements within the URR of different HPV types, little is known about how the 5′ end of the URR regulates early viral gene expression. It has been reported for HPV18 that deletion of 128 bp from the 5′ terminus of the URR results in a marked increase in transcriptional activity (21). Pattison et al. (54) have shown that binding of CDP to a negative transcriptional regulatory element within the 5′ end of the HPV6 URR is important in maintaining the tight link between keratinocyte differentiation and HPV gene expression. The presence of a matrix attachment region in the 5′ URR has also been demonstrated (68). Besides these findings, little is known about the regulatory interactions that control gene expression from the E6/E7 promoter relative to its role in the viral life cycle.

The complete replicative cycle of HPVs is tightly linked to the differentiation state of the natural host cell (37). Viral DNA maintenance and replication occur along with cellular DNA replication in the mitotically active basal layer, ensuring that both parent and daughter cells maintain a constant number of viral genomes (32). As cells migrate up through the epithelium, they undergo a complex pattern of differentiation. Concomitant with cellular differentiation in virally infected cells is the vegetative amplification of the viral genome, the expression of the late proteins, and the assembly of the virions (6, 17, 37, 39, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51). Therefore, all aspects of the HPV differentiation-dependent life cycle are controlled by the temporal and spatial growth mechanisms of its natural host tissue, the squamous epithelium.

In this study we used linker-scanning mutational analysis to identify cis regulatory elements contained within the 5′ URR involved in the control of transcriptional activity at different stages of the viral life cycle. Our aims were (i) to define the transcriptional regulatory role of viral cis elements in an undifferentiated basal environment, which represents the initial host cell seen by the virus immediately following infection, (ii) to determine the effect of cellular differentiation on transcriptional control by viral cis elements, (iii) to identify cis elements that regulate transcription in the presence or absence of all viral gene product and viral replication, and (iv) to determine the effect of induction of the PKC pathway in regulating p99 transcriptional activity by cis elements.

The computer-assisted sequence analysis program TRANSFAC (72) has shown that the 5′ region of the URR (nt 7259 to 7510) contains numerous abutting and overlapping putative binding sites for several cellular transcription factors. Table 4 lists all of the linker-scanning mutants used in this study along with putative regulatory sequences affected by each mutation. The purpose of our study was to identify cis elements located within a portion of the 5′ URR that are involved in transcriptional regulation depending on the cellular environment of the host cell at different stages of the differentiation-dependent viral life cycle.

TABLE 4.

Transfac analysis identifying known and putative control elements replaced in each of the linker-scanning mutants used in this study

| Mutant | Known and putative binding sites affected by each mutation | Refer- ence |

|---|---|---|

| B1 (nt 7259-7276) | C/EBPα, GATA-1, Oct-1, SRF, TBP, TFIID | |

| B2 (nt 7277-7294) | GRE | |

| B3 (nt 7295-7312) | GRE, C/EBPα, TBP | |

| B4 (nt 7313-7330) | ||

| B5 (nt 7331-7348) | Sp1, NF1 | |

| B6 (nt 7349-7366) | Sp1, NF1, AP-1 | |

| B7 (nt 7367-7384) | C/EBPβ, AP-1, c-Fos, CREB | |

| B8 (nt 7385-7402) | C/EBPβ, AP-1, c-Fos, CREB, YY1, SRF, c-Jun, NF1, C/EBPα | 29 |

| B9 (nt 7403-7420) | NF1, C/EBPα, GRE, Sp1, E2 | |

| B10 (nt 7421-7438) | ||

| B11 (nt 7439-7456) | YY1, C/EBPα, TBP, SRF, NF1 | 29 |

| B12 (nt 7457-7474) | TBP, SRF, NF1, YY1, NFκB, Oct-1 | 29 |

| B13 (nt 7475-7492) | Oct-1, E2, IRF-1, c-Myb, C/EBPα | 24 |

| B14 (nt 7493-7510) | Oct-1, GRE, C/EBPβ |

Early stages of the viral life cycle.

Monolayer keratinocyte culture, which mimics the basal cell environment seen by the virus immediately following infection, was used to analyze transcriptional regulation of the p99 promoter during the initial stage of the viral life cycle. Compared to C33A and 9E monolayer cultures, NHEK cells appear to be more dependent on the wild-type sequence for p99 promoter activity, as a general repression in transcriptional activity was observed upon transfection with any of the 14 linker-scanning mutants. Our finding suggests that the region replaced in mutant B12 is involved in the positive regulation of p99 promoter activity in all three cell types.

Of the three YY1 binding sites present in the auxiliary enhancer (nt 7383 to 7510) region in HPV31, only two sites have been demonstrated to be important as transcriptional activators (29). The region replaced in mutant B12 corresponds to one of these two YY1 binding sites. YY1 has been shown to act as a positive regulator of HPV18 URR activity, which is dependent on its physical interaction with C/EBPβ, and the functional interplay between YY1 and C/EBPβ plays a critical role in regulating HPV18 URR activity in a cell type-specific manner (5). However, transfection with mutant B8, in which a known YY1 binding site was also replaced (31), resulted in the reduction of promoter activity in C33A and NHEK but not in 9E cells, indicating that this region acts as a positive regulator of transcription in C33A and NHEK cells. However, the YY1 binding site replaced in mutant B8 corresponds to the YY1 binding site in the auxiliary enhancer region, which had previously been shown to have no significant role in augmenting enhancer function (29). On the other hand, transfection with mutant B13, in which a known E2BS and a putative c-Myb binding site were replaced, resulted in significant reduction in promoter activity in C33A (Fig. 3), 9E (Fig. 4A), and NHEK (Fig. 4B) monolayer cultures. These observations suggest that the cis elements contained within the region replaced in mutant B13 are involved in the positive regulation of HPV31 p99 activity irrespective of the cell type.

In the URR of genital HPVs, the distribution and locations of the four E2BS are highly conserved. In HPV18, the promoter-distal-most E2BS possesses the strongest affinity for E2, and binding of E2 to this site mediates stimulatory transcriptional effects and counteracts repression of promoter activity (63). Moreover, the interaction of E2 with the distal E2BS in HPV18 was found to be the most stable compared to the binding affinity to the other three E2BS (13). In HPV31b, the distal E2BS is required for the stable maintenance of viral episomes (67). Our findings coupled with those of the previous studies suggest that the region replaced in mutant B13 acts as a positive regulator of p99 promoter activity. Besides an E2BS, this region contains a putative c-Myb binding site. A previous study on HPV16 has shown that overexpression of c-Myb is able to transactivate p97-dependent E6/E7 gene expression (43). Therefore, the effect of the B13 mutation may also be due to the loss of a c-Myb site.

Transfection with mutant B14, in which a putative C/EBPβ and two Oct-1 binding sites were replaced, decreased promoter activity significantly in NHEK monolayer culture but had no effect in the other cell types. Therefore, this region functions as a positive regulator of p99 transcriptional activity in NHEK cells. Oct-1 is known to activate the HPV16 enhancer via a synergistic interaction with NF1 at a conserved composite NFA/NF1 element (44). It is therefore possible that a cellular environment that affects Oct-1 binding or its interaction with NF1 will result in an altered level of viral transcriptional activity. Cell type-specific activity of this region may be the result of synergism of factors that occur in different quantities in different cell types. Previous studies in HPV18 have shown that binding of a C/EBPβ-YY1 complex to the switch region of the HPV18 URR plays a critical role in conferring cell type-specific transcriptional activity (5). Besides YY1, other transcription factors that have been shown to complex with C/EBPβ include NF-κB (64, 65), glucocorticoid receptor (42), Jun and Fos (23), and Sp1 (33). Like the switch region in HPV18, which specifically recruits C/EBPβ-YY1 (5), it is possible that different C/EBPβ binding sites may select different C/EBPβ dimers, resulting in different functional outcomes.

The addition of PKC pathway activators such as the synthetic diacylglycerol C8 to the culture medium of raft tissue has been shown to induce a more complete differentiation program (35, 37, 47, 50). We were therefore interested in determining whether treatment with C8 would influence the transcriptional activity of the p99 promoter. Induction of the PKC pathway in 9E monolayer culture had no effect on transcriptional regulation, as the promoter activity from the wild-type and mutant constructs showed no significant change in the presence of C8 compared to that in similar studies done in the absence of C8. However, the addition of C8 to monolayer cultures of NHEK cells transfected with either the wild-type or mutant constructs resulted in an increase in promoter activity compared to similar transfection studies conducted in the absence of C8 (Fig. 4). The increase in p99 promoter activity observed upon induction of the PKC pathway was most significant when NHEK cells were transfected with B5, B6, B9, B13, and B14. Taken together these data suggest that in NHEK cells, the induction of the PKC pathway plays a role in the transcriptional regulation of the p99 promoter by modulating certain cis regulatory elements.

Late stages of viral life cycle.

The HPV life cycle is closely related to the differentiation program of its host cell, the squamous epithelium. Depending on the state of differentiation of the host cell, some cellular factors can act as either inducers or repressors of promoter activity (1, 2, 45, 52). Transfection of 9E cells with mutants B1, B2, B4, B7, B12, B13, and B14 represses p99 activity compared to the wild-type construct, indicating that the cis elements that are affected in these mutants are involved in positive transcriptional regulation in differentiating 9E cells. By correlating data between the monolayer and differentiating systems, we were able to identify regions in the 5′ URR whose activities were affected by host tissue differentiation. The difference in promoter activity observed between undifferentiated and differentiated 9E cells upon transfection with mutants B7 and B14 suggests that the cis elements replaced in these mutants are also regulated by changes in the cellular environment. Sequence analysis revealed that the region replaced in mutants B7 and B14 both contained putative C/EBPβ binding sites. Studies have shown that C/EBPβ negatively regulates the URR in HPV11 and that changes in C/EBPβ expression during differentiation relieve this negative regulation (71).

Besides a C/EBPβ binding site, mutant B7 also has putative AP-1, CREB, and c-Fos binding sites, while the B14 mutation replaces a putative Oct-1 and GRE binding site. In HPV31, each Jun family member has been shown to be capable of activating E6/E7 expression in cooperation with c-Fos (30). Thus, differences between the Jun family members present under different differentiation states and in different cell types may contribute to the expression of E6/E7. Moreover, the interaction of AP-1 with cellular factors such as glucocorticoid receptors (60) could effect or alter AP-1 function in different cell types and growth states. Previous studies in HPV31 have shown that E6/E7 expression in differentiating epithelium is critically regulated by AP-1 (30). Previous studies in HPV16 have shown that E6 interacts with CBP/p300 (53). The loss of a putative CREB binding site in mutant B7 coupled with the induction of differentiation in 9E cells may alter subsequent binding of CBP to the CREB and diminish promoter activity. The replacement of the putative GRE and Oct-1 binding sites in mutant B14 may have led to the loss of promoter activity observed in 9E cells (9, 75). Differences in the relative concentration of a particular transcription factor or its interaction with other transcription factors or both between the undifferentiated and differentiated cellular environment could cause the difference in promoter activity observed in 9E cells upon transfection with these mutants. The difference in promoter activity observed between undifferentiated and differentiated 9E cells upon transfection with mutants B7 and B14 suggests that the cis elements replaced in these mutant are regulated by changes in the cellular environment.

The role of host tissue differentiation on viral transcriptional regulation was evaluated by correlating data from the monolayer experiments to those obtained from the differentiation studies with NHEK cells. Though no marked change in promoter activity was observed between the differentiated and undifferentiated systems when NHEK cells were transfected with mutants B4, B5, B6, B9, B13, and B14, transfection with mutants B3, B10, and B12 resulted in an increase in promoter activity upon differentiation. These results indicate that the regions replaced in mutants B3, B10, and B12 are involved in the negative regulation of promoter activity in a differentiating system but not in undifferentiated monolayer cells. A general trend towards a significant reduction in promoter activity was observed for all the mutants in differentiating NHEK cells. Though reduction in promoter activity was also observed for some mutants in differentiating 9E cells, the inhibition in transcriptional activity was not as drastic as that seen in NHEK cells. As 9E cells contain episomal copies of HPV31, it is possible that the differentiation program of 9E cells will differ from that of an uninfected nonimmortalized normal keratinocyte population. This could play a role in the reduced p99 promoter activity in NHEK cells following differentiation.

Previous studies have shown that the more complete differentiation of 9E cell rafts upon PKC activation is accompanied by a strong induction of HPV31 late gene expression and the assembly of virions (37, 47). Though the induction of the PKC pathway in monolayer cultures of 9E cells had no influence on the regulation of promoter activity by the cis elements, the induction of the PKC pathway in the differentiating system resulted in significant reduction in p99 promoter activity for most of the mutants. In NHEK cells, induction of the PKC pathway in a differentiating system resulted in a general reduction in promoter activity for all mutants. A 70 to 80% reduction was observed for all mutants except B6, which exhibited 99% inhibition (Fig. 5B). This observation is in striking contrast to similar studies conducted in NHEK monolayer cultures, where addition of C8 rescued repression of promoter activity. As addition of C8 dramatically reduced promoter activity in differentiating 9E and NHEK cells, it is possible that C8 might induce a regulatory protein that inhibits p99 transcription. As the addition of PKC activator C8 also induced a more complete differentiation program, it is possible that the regulatory factor induced by C8 is differentiation specific.

Therefore, the overall pattern of regulatory sequence utilization changes notably among different cell types and under different cellular condition. In summary, this study has provided an extensive map of functional elements in a portion of the 5′ URR region and auxiliary enhancer domain that are involved in the regulation of p99 promoter activity at different stages of the viral life cycle. In the process, we have identified cis regulatory regions which contribute to the regulation of p99 promoter activity during the differentiation-dependent HPV life cycle.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ann Roman for valuable suggestions regarding the differentiation studies with methylcellulose. The E2 expression vector was generously provided by Laimonis Laimins. We thank Samina Alam, Margaret McLaughlin Drubin, and Jason Bodily for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant CA 79006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ai, W., E. Toussaint, and A. Roman. 1999. CCAAT displacement protein binds to and negatively regulates human papillomavirus type 6 E6, E7, and E1 promoters. J. Virol. 73:4220-4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apt, D., R. M. Watts, G. Suske, and H. U. Bernard. 1996. High Sp1/Sp3 ratios in epithelial cells during epithelial differentiation and cellular transformation correlate with the activation of the HPV-16 promoter. Virology 224:281-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauknecht, T., P. Angel, H. D. Royer, and H. zur Hausen. 1992. Identification of a negative regulatory domain in the human papillomavirus type 18 promoter: interaction with the transcriptional repressor YY1. EMBO J. 11:4607-4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauknecht, T., F. Jundt, I. Herr, T. Oehler, H. Delius, Y. Shi, P. Angel, and H. zur Hausen. 1995. A switch region determines the cell type-specific positive or negative action of YY1 on the activity of the human papillomavirus type 18 promoter. J. Virol. 69:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauknecht, T., R. H. See, and Y. Shi. 1996. A novel C/EBP beta-YY1 complex controls the cell-type-specific activity of the human papillomavirus type 18 upstream regulatory region. J. Virol. 70:7695-7705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedell, M. A., J. B. Hudson, T. R. Golub, M. E. Turyk, M. Hosken, G. D. Wilbanks, and L. A. Laimins. 1991. Amplification of human papillomavirus genomes in vitro is dependent on epithelial differentiation. J. Virol. 65:2254-2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard, B. A., C. Bailly, M. C. Lenoir, M. Darmon, F. Thierry, and M. Yaniv. 1989. The human papillomavirus type 18 (HPV18) E2 gene product is a repressor of the HPV18 regulatory region in human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 63:4317-4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boshart, M., L. Gissmann, H. Ikenberg, A. Kleinheinz, W. Scheurlen, and H. zur Hausen. 1984. A new type of papillomavirus DNA, its presence in genital cancer biopsies and in cell lines derived from cervical cancer. EMBO J. 3:1151-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan, W. K., G. Klock, and H. U. Bernard. 1989. Progesterone and glucocorticoid response elements occur in the long control regions of several human papillomaviruses involved in anogenital neoplasia. J. Virol. 63:3261-3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin, M. T., R. Hirochika, H. Hirochika, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1988. Regulation of human papillomavirus type 11 enhancer and E6 promoter by activating and repressing proteins from the E2 open reading frame: functional and biochemical studies. J. Virol. 62:2994-3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong, T., D. Apt, B. Gloss, M. Isa, and H. U. Bernard. 1991. The enhancer of human papillomavirus type 16: binding sites for the ubiquitous transcription factors Oct-1, NFA, TEF-2, NF1, and AP-1 participate in epithelial cell-specific transcription. J. Virol. 65:5933-5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cripe, T. P., T. H. Haugen, J. P. Turk, F. Tabatabai, P. G. Schmid, M. Durst, L. Gissmann, A. Roman, and L. P. Turek. 1987. Transcriptional regulation of the human papillomavirus-16 E6-E7 promoter by a keratinocyte-dependent enhancer, and by viral E2 trans-activator and repressor gene products: implications for cervical carcinogenesis. EMBO J. 6:3745-3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demeret, C., C. Desaintes, M. Yaniv, and F. Thierry. 1997. Different mechanisms contribute to the E2-mediated transcriptional repression of human papillomavirus type 18 viral oncogenes. J. Virol. 71:9343-9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dollard, S. C., T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1993. Regulation of the human papillomavirus type 11 E6 promoter by viral and host transcription factors in primary human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 67:1721-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durst, M., L. Gissmann, H. Ikenberg, and H. zur Hausen. 1983. A papillomavirus DNA from a cervical carcinoma and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:3812-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flores, E. R., and P. F. Lambert. 1997. Evidence for a switch in the mode of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA replication during the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 71:7167-7179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frattini, M. G., H. B. Lim, and L. A. Laimins. 1996. In vitro synthesis of oncogenic human papillomaviruses requires episomal genomes for differentiation-dependent late expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3062-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawley-Nelson, P., E. J. Androphy, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1988. The specific DNA recognition sequence of the bovine papillomavirus E2 protein is an E2-dependent enhancer. EMBO J. 7:525-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heck, D. V., C. L. Yee, P. M. Howley, and K. Munger. 1992. Efficiency of binding the retinoblastoma protein correlates with the transforming capacity of the E7 oncoproteins of the human papillomaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4442-4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoppe-Seyler, F., and K. Butz. 1992. Activation of human papillomavirus type 18 E6-E7 oncogene expression by transcription factor Sp1. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:6701-6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoppe-Seyler, F., and K. Butz. 1993. A novel cis-stimulatory element maps to the 5′ portion of the human papillomavirus type 18 upstream regulatory region and is functionally dependent on a sequence-aberrant Sp1 binding site. J. Gen. Virol. 74:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoppe-Seyler, F., K. Butz, and H. zur Hausen. 1991. Repression of the human papillomavirus type 18 enhancer by the cellular transcription factor Oct-1. J. Virol. 65:5613-5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu, W., T. K. Kerppola, P. L. Chen, T. Curran, and S. Chen-Kiang. 1994. Fos and Jun repress transcription activation by NF-IL6 through association at the basic zipper region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:268-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubert, W. G., T. Kanaya, and L. A. Laimins. 1999. DNA replication of human papillomavirus type 31 is modulated by elements of the upstream regulatory region that lie 5′ of the minimal origin. J. Virol. 73:1835-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel, M., J. B. Hudson, and L. A. Laimins. 1992. Differentiation-induced and constitutive transcription of human papillomavirus type 31b in cell lines containing viral episomes. J. Virol. 66:6070-6080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hummel, M., H. B. Lim, and L. A. Laimins. 1995. Human papillomavirus type 31b late gene expression is regulated through protein kinase C-mediated changes in RNA processing. J. Virol. 69:3381-3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishiji, T., M. J. Lace, S. Parkkinen, R. D. Anderson, T. H. Haugen, T. P. Cripe, J. H. Xiao, I. Davidson, P. Chambon, and L. P. Turek. 1992. Transcriptional enhancer factor (TEF)-1 and its cell-specific co-activator activate human papillomavirus-16 E6 and E7 oncogene transcription in keratinocytes and cervical carcinoma cells. EMBO J. 11:2271-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jundt, F., I. Herr, P. Angel, H. zur Hausen, and T. Bauknecht. 1995. Transcriptional control of human papillomavirus type 18 oncogene expression in different cell lines: role of transcription factor YY1. Virus Genes 11:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanaya, T., S. Kyo, and L. A. Laimins. 1997. The 5′ region of the human papillomavirus type 31 upstream regulatory region acts as an enhancer which augments viral early expression through the action of YY1. Virology 237:159-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyo, S., D. J. Klumpp, M. Inoue, T. Kanaya, and L. A. Laimins. 1997. Expression of AP1 during cellular differentiation determines human papillomavirus E6/E7 expression in stratified epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 78:401-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyo, S., A. Tam, and L. A. Laimins. 1995. Transcriptional activity of human papillomavirus type 31b enhancer is regulated through synergistic interaction of AP1 with two novel cellular factors. Virology 211:184-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert, P. F. 1991. Papillomavirus DNA replication. J. Virol. 65:3417-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, Y. H., S. C. Williams, M. Baer, E. Sterneck, F. J. Gonzalez, and P. F. Johnson. 1997. The ability of C/EBP beta but not C/EBP alpha to synergize with an Sp1 protein is specified by the leucine zipper and activation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2038-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mack, D. H., and L. A. Laimins. 1991. A keratinocyte-specific transcription factor, KRF-1, interacts with AP-1 to activate expression of human papillomavirus type 18 in squamous epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:9102-9106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer, T. J., and C. Meyers. 1998. Temporal and spatial expression of the E5a protein during the differentiation-dependent life cycle of human papillomavirus type 31b. Virology 248:208-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCance, D. J., R. Kopan, E. Fuchs, and L. A. Laimins. 1988. Human papillomavirus type 16 alters human epithelial cell differentiation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:7169-7173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyers, C., M. G. Frattini, J. B. Hudson, and L. A. Laimins. 1992. Biosynthesis of human papillomavirus from a continuous cell line upon epithelial differentiation. Science 257:971-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyers, C. 1996. Organotypic (raft) epithelial tissues culture system for differentiation dependent replication of papillomavirus. Methods Cell Sci. 18:201-210. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyers, C., T. J. Mayer, and M. A. Ozbun. 1997. Synthesis of infectious human papillomavirus type 18 in differentiating epithelium transfected with viral DNA. J. Virol. 71:7381-7386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohar, A., and M. Frias-Mendivil. 2000. Epidemiology of cervical cancer. Cancer Investig. 18:584-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moskaluk, C., and D. Bastia. 1987. The E2 “gene” of bovine papillomavirus encodes an enhancer-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:1215-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishio, Y., H. Isshiki, T. Kishimoto, and S. Akira. 1993. A nuclear factor for interleukin-6 expression (NF-IL6) and the glucocorticoid receptor synergistically activate transcription of the rat α1-acid glycoprotein gene via direct protein-protein interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:1854-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nurnberg, W., M. Artuc, M. Nawrath, J. Lovric, S. Stuting, K. Moelling, B. M. Czarnetzki, and D. Schadendorf. 1995. Human c-myb is expressed in cervical carcinomas and transactivates the HPV-16 promoter. Cancer Res. 55:4432-4437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connor, M., and H. U. Bernard. 1995. Oct-1 activates the epithelial-specific enhancer of human papillomavirus type 16 via a synergistic interaction with NFI at a conserved composite regulatory element. Virology 207:77-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Connor, M. J., W. Stunkel, C. H. Koh, H. Zimmermann, and H. U. Bernard. 2000. The differentiation-specific factor CDP/Cut represses transcription and replication of human papillomaviruses through a conserved silencing element. J. Virol. 74:401-410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Offord, E. A., and P. Beard. 1990. A member of the activator protein 1 family found in keratinocytes but not in fibroblasts required for transcription from a human papillomavirus type 18 promoter. J. Virol. 64:4792-4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozbun, M. A., and C. Meyers. 1997. Characterization of late gene transcripts expressed during vegetative replication of human papillomavirus type 31b. J. Virol. 71:5161-5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozbun, M. A., and C. Meyers. 1998. Human papillomavirus type 31b E1 and E2 transcript expression correlates with vegetative viral genome amplification. Virology 248:218-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozbun, M. A., and C. Meyers. 1998. Temporal usage of multiple promoters during the life cycle of human papillomavirus type 31b. J. Virol. 72:2715-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozbun, M. A., and C. Meyers. 1996. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces differentiation in human papillomavirus-positive keratinocytes. J. Virol. 70:5437-5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ozbun, M. A., and C. Meyers. 1999. Two novel promoters in the upstream regulatory region of human papillomavirus type 31b are negatively regulated by epithelial differentiation. J. Virol. 73:3505-3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parker, J. N., W. Zhao, K. J. Askins, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1997. Mutational analyses of differentiation-dependent human papillomavirus type 18 enhancer elements in epithelial raft cultures of neonatal foreskin keratinocytes. Cell Growth Differ. 8:751-762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel, D., S. M. Huang, L. A. Baglia, and D. J. McCance. 1999. The E6 protein of human papillomavirus type 16 binds to and inhibits co-activation by CBP and p300. EMBO J. 18:5061-5072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pattison, S., D. G. Skalnik, and A. Roman. 1997. CCAAT displacement protein, a regulator of differentiation-specific gene expression, binds a negative regulatory element within the 5′ end of the human papillomavirus type 6 long control region. J. Virol. 71:2013-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfister, H. 1987. Relationship of papillomaviruses to anogenital cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 14:349-361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romanczuk, H., F. Thierry, and P. M. Howley. 1990. Mutational analysis of cis elements involved in E2 modulation of human papillomavirus type 16 P97 and type 18 P105 promoters. J. Virol. 64:2849-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruesch, M. N., F. Stubenrauch, and L. A. Laimins. 1998. Activation of papillomavirus late gene transcription and genome amplification upon differentiation in semisolid medium is coincident with expression of involucrin and transglutaminase but not keratin-10. J. Virol. 72:5016-5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Russell, J., and M. R. Botchan. 1995. cis-Acting components of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA replication: linker substitution analysis of the HPV type 11 origin. J. Virol. 69:651-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scheffner, M., B. A. Werness, J. M. Huibregtse, A. J. Levine, and P. M. Howley. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schule, R., P. Rangarajan, S. Kliewer, L. J. Ransone, J. Bolado, N. Yang, I. M. Verma, and R. M. Evans. 1990. Functional antagonism between oncoprotein c-Jun and the glucocorticoid receptor. Cell 62:1217-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sethna, M., and J. P. Weir. 1993. Mutational analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein E promoter. Virology 196:532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steffy, K. R., and J. P. Weir. 1991. Mutational analysis of two herpes simplex virus type 1 late promoters. J. Virol. 65:6454-6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steger, G., and S. Corbach. 1997. Dose-dependent regulation of the early promoter of human papillomavirus type 18 by the viral E2 protein. J. Virol. 71:50-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein, B., and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1993. Distinct mechanisms for regulation of the interleukin-8 gene involve synergism and cooperativity between C/EBP and NF-κB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:7191-7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stein, B., P. C. Cogswell, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1993. Functional and physical associations between NF-κB and C/EBP family members: a Rel domain-bZIP interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:3964-3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Struyk, L., E. van der Meijden, R. Minnaar, V. Fontaine, I. Meijer, and J. ter Schegget. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 16 LCR by different C/EBPβ isoforms. Mol. Carcinog. 28:42-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stubenrauch, F., H. B. Lim, and L. A. Laimins. 1998. Differential requirements for conserved E2 binding sites in the life cycle of oncogenic human papillomavirus type 31. J. Virol. 72:1071-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tan, S. H., D. Bartsch, E. Schwarz, and H. U. Bernard. 1998. Nuclear matrix attachment regions of human papillomavirus type 16 point toward conservation of these genomic elements in all genital papillomaviruses. J. Virol. 72:3610-3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan, S. H., L. E. Leong, P. A. Walker, and H. U. Bernard. 1994. The human papillomavirus type 16 E2 transcription factor binds with low cooperativity to two flanking sites and represses the E6 promoter through displacement of Sp1 and TFIID. J. Virol. 68:6411-6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thierry, F., G. Spyrou, M. Yaniv, and P. Howley. 1992. Two AP1 sites binding JunB are essential for human papillomavirus type 18 transcription in keratinocytes. J. Virol. 66:3740-3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, H., K. Liu, F. Yuan, L. Berdichevsky, L. B. Taichman, and K. Auborn. 1996. C/EBPβ is a negative regulator of human papillomavirus type 11 in keratinocytes. J. Virol. 70:4839-4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wingender, E., X. Chen, R. Hehl, H. Karas, I. Liebich, V. Matys, T. Meinhardt, M. Pruss, I. Reuter, and F. Schacherer. 2000. TRANSFAC: an integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:316-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zeichner, S. L., J. Y. Kim, and J. C. Alwine. 1991. Linker-scanning mutational analysis of the transcriptional activity of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 65:2436-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao, W., L. T. Chow, and T. R. Broker. 1999. A distal element in the HPV-11 upstream regulatory region contributes to promoter repression in basal keratinocytes in squamous epithelium. Virology 253:219-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao, W., L. T. Chow, and T. R. Broker. 1997. Transcription activities of human papillomavirus type 11 E6 promoter-proximal elements in raft and submerged cultures of foreskin keratinocytes. J. Virol. 71:8832-8840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]