Abstract

A critical aspect of AIDS pathogenesis that remains unclear is the mechanism by which human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) induces death in CD4+ T lymphocytes. A better understanding of the death process occurring in infected cells may provide valuable insight into the viral component responsible for cytopathicity. This would aid the design of preventive treatments against the rapid decline of CD4+ T cells that results in AIDS. Previously, apoptotic cell death has been reported in HIV-1 infections in cultured T cells, and it has been suggested that this could affect both infected and uninfected cells. To evaluate the mechanism of this effect, we have studied HIV-1-induced cell death extensively by infecting several T-cell lines and assessing the level of apoptosis by using various biochemical and flow cytometric assays. Contrary to the prevailing view that apoptosis plays a prominent role in HIV-1-mediated T-cell death, we found that Jurkat and H9 cells dying from HIV-1 infection fail to exhibit the collective hallmarks of apoptosis. Among the parameters investigated, Annexin V display, caspase activity and cleavage of caspase substrates, TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) signal, and APO2.7 display were detected at low to negligible levels. Neither peptide caspase inhibitors nor the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-xL or v-FLIP could prevent cell death in HIV-1-infected cultures. Furthermore, Jurkat cell lines deficient in RIP, caspase-8, or FADD were as susceptible as wild-type Jurkat cells to HIV-1 cytopathicity. These results suggest that the primary mode of cytopathicity by laboratory-adapted molecular clones of HIV-1 in cultured cell lines is not via apoptosis. Rather, cell death occurs most likely via a necrotic or lytic form of death independent of caspase activation in directly infected cells.

AIDS pathogenesis is characterized by a major decline in circulating CD4+ T cells, resulting in susceptibility to opportunistic infections that pose a lethal threat as the afflicted individual becomes immunocompromised (12). It remains unclear, however, how human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), the causative infectious agent of AIDS, depletes this critical immune cell population. During the long period of infection that typically precedes the onset of AIDS-defining illnesses, there appears to be a constant and inexorable attrition of CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, kinetic modeling of plasma viremia and CD4+ T-cell levels suggests that this cell population is constantly turned over in a cycle of infection, elimination, and replenishment in HIV-1-infected individuals (23, 61). Since viral replication occurs principally within CD4+ T lymphocytes, direct cytopathic effects may be responsible for the death of these cells. Bystander death may also play a role in the elimination of these cells, given the low frequency of infected T cells at any given time, as may cell-mediated cytotoxicity against HIV-1-infected cells, but their relative importance is still unresolved and remains an area of active investigation. Therefore, elucidating the mechanism of direct HIV-1 cytopathicity may be instrumental in understanding, and ultimately preventing, the decline in CD4+ T cells among infected individuals.

Apoptosis has been implicated in the cytopathicity of several human and animal viruses, including retroviruses such as HIV-1 (7, 9, 26). Apoptosis is defined as an active physiological process of cellular self-destruction, distinguished by a specific series of morphological and biochemical changes that stem from the activation of the caspase family of cysteine proteases (45). Caspases have an evolutionarily conserved role in programmed cell death from nematodes to humans (46). For the purposes of this study, we define apoptosis as caspase activation resulting in DNA fragmentation, proteolytic cleavage of cellular substrates, loss of membrane phospholipid asymmetry, and characteristic cellular condensation evident by electron microscopy. In contrast, necrotic cell death or oncosis, featuring cytoplasmic swelling and lysis, generally occurs in a nonsystematic fashion after traumatic or toxic stimuli without coordination by a specific cellular machinery involving caspase activation (56). Recently, the serine-threonine kinase, receptor-interacting protein (RIP), that enters the death pathways via “death domain” interactions has been implicated in a caspase-8-independent Fas-induced pathway of necrosis (24).

Apoptosis-inducing caspases are activated through proteolysis of a proenzyme form via four principal pathways. The receptor-mediated pathway involves cross-linking various death domain-containing receptors such as CD95/Fas/APO-1 or other tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily members resulting in a cascade of caspase activation (42, 46). This can be readily studied by triggering apoptosis with agonist antibodies against the Fas molecule (anti-Fas) or the natural ligands for the individual TNF receptor-like receptors such as Fas ligand (FasL), TNF, or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (63). A second pathway of apoptosis induction may occur via mitochondria, whereby opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore releases apoptogenic proteins such as cytochrome c, apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (APAF-1), and caspase-9 (49). The mitochondrial pathway is triggered by treating cells with agents such as staurosporine, sodium butyrate (NaB), and irradiation (25, 50). A third pathway, whose significance for cellular homeostasis is not known, is the cytoplasmic aggregation of proteins containing “death effector domains” (DEDs) to form “death effector filaments” (DEFs) that recruit and activate caspases causing rapid apoptosis (53). A fourth pathway involving the activation of caspase-12 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) has been recently described (43, 44). These pathways have the common feature of activating apoptosis-inducing caspases, but they can be distinguished by inhibitors. Apoptosis due to death receptors and DEFs can be inhibited by a viral FLICE-inhibitory protein called MC159, whereas the mitochondrial and ER pathways of death are blocked by Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (34, 44, 53). As such, we further define apoptosis as a cell death process accomplished via one of the above pathways.

Apoptosis has been previously implicated in the death of T cells during HIV-1 infection. Evidence has suggested that apoptosis could play a role in both direct killing of infected CD4+ T cells, as well as in the death of uninfected bystander CD4+ T cells (26). The first reports documenting HIV-1-induced apoptosis demonstrated fragmentation of cellular DNA among infected T-cell cultures (32, 55). Other reports on apoptosis in HIV infection have largely drawn upon the theory of bystander killing in which uninfected CD4+, as well as CD8+, T cells die as a result of gp120-CD4 interactions (3, 13, 19, 20). Failure to correlate the level of apoptosis in lymph nodes of HIV-infected patients with the stage of disease or viral burden, however, casts further doubt on the role of apoptosis in direct cell killing (40).

There has been wide disagreement on the attributes of apoptosis that occur during HIV-1 infection and which viral proteins are required for apoptosis induction. Nearly all of the HIV-1 proteins have been suggested to account for HIV-1-induced death in reports that are often contradictory. For example, Tat has been proposed to induce apoptosis in some studies but to prevent apoptosis in other studies (4, 18, 35, 38, 52, 62). Controversy has also been raised by reports that observe necrosis or caspase-independent death pathways instead of apoptosis in cultured HIV-1 systems (10, 31, 48, 52). In an attempt to reconcile the mixed reports describing HIV-1-induced cell death, we investigated T lymphoma cell lines infected in vitro with laboratory strains of HIV-1 to determine what role apoptosis or proteins involved in apoptotic pathways play in HIV-1 cytopathicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell cultures.

CD4+ Jurkat T cells, H9 T cells, and CEM 5.25 T cells were maintained in RPMI complete medium (RPMI 1640; BioWhittaker) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin/ml, 2.4 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. The CEM 5.25 cells were carried in 400 μg of Geneticin (G418; Gibco-BRL)/ml to maintain expression of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat-promoted green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (17). Mutant Jurkat cell lines deficient in RIP, caspase-8 (Jurkat 192), and Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD) (Jurkat I2.1) were kindly provided by Brian Seed and John Blenis. Mycoplasma-free Jurkat T cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were sorted for high expression of CD4 and CXCR4 by single-cell cloning of anti-hCD4 fluorescein isothiocyanate-stained (Pharmingen) Jurkat cells on a FACScan into a 96-well round-bottom plate. A resulting CD4hi cell clone, Jurkat 5.5, was used for infections and the generation of stable Jurkat T-cell lines expressing MC159 by cotransfection (BTX EC600 electroporator; 260 V, 1,040 μF, 720 Ω) with pCI-MC159 and pcDNA3 bearing the neomycin resistance gene for selection (6). The cultures were selected with 800 μg of G418/ml and cloned by limiting dilution in 96-well plates. Bcl-xL stable clones were generated in a similar fashion by using pcDNA3−Bcl-xL or pcDNA3 alone for electroporation (8). After selection, all clones were carried in 400 μg of G418/ml until inoculation with virus, at which point selection media were removed. An alternate CD4hi Jurkat T-cell line, Jurkat 1.9, derived from JAK3 cells was created in a similar fashion and used for infections.

HIV stock and infections.

HIV stocks and plasmids were obtained from the NIAID AIDS Repository unless otherwise indicated. The NL4-3HSA strain HIV-1 stock was prepared from cell-free supernatant from infected H9 T cells by using an original stock from Ned Landau (Salk Institute) (21) or by plasmid transfection of 293T cells by using FuGENE (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. IIIB and SF162 strains of HIV-1 were generated by direct passage on Jurkat cells. In addition, we obtained the original IIIB strain of HIV-1 from Mark Feinberg (Emory University Vaccine Research Center). Pseudotyped viral stocks of NL4-3HSA were harvested 48 h after cotransfection of 293T cells with pLVSV-G and pNL4-3HSA env+ or env− (blunt-ended NdeI site). Viral titers were assessed by the β-Gal MAGI assay (29) or by infection of Jurkat T cells by using various dilution to determine a functional viral titer for Jurkat cells. This latter assay is based on a predicted frequency of 66.67% infected cells after viral inoculation with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) equal to one in a single-round infection according to the Poisson distribution. H9, CEM 5.25, and Jurkat T cells (0.5 × 106 to 1.0 × 106 in 6-ml Falcon 2063 tubes) were inoculated with 100 μl of HIV-1 (3.8 × 105 infectious units/ml) in 200 μl of medium with 1 μg of Polybrene/ml. Samples were centrifuged for 2 h at 1,800 rpm at room temperature and then resuspended in 5 ml of medium in T25 flasks. All infections except for those involving apoptosis inhibitors and mediators were performed in this manner. For the zVAD/Boc-D, MC159, and Bcl-xL infections, high-efficiency spinfection was performed by prolonged centrifugation (12 to 14 h, 800 × g, 30°C; Fisher Scientific Marathon 3200R centrifuge) of the cell-virus mixture, followed by resuspension in 2 ml of medium in a 12-well plate. Experiments involving cell lines deficient in RIP, caspase-8, and FADD were infected by inoculation of 106 cells in 12-well fibronectin-coated plates (Biocoat; Becton Dickinson) at an MOI of 0.75 in 5 μg of Polybrene/ml and centrifugation for 30 min at 800 × g at 25°C. Cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 5 × 105 to 10 × 105 cells/ml by feeding and splitting cultures as needed. The reagent lamivudine (3TC) (obtained from Raymond F. Schinazi) was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health (NIH). Cells were cultured in the presence of 10 μM 3TC for 24 h prior to inoculation and then replenished every 24 to 48 h. zVAD-fmk or BocD-fmk (Enzyme Systems Products) was added to cultures at 100 μM when the level of infection peaked and then replenished with the same amount of inhibitor every 48 h.

Assays for viral production and cell viability.

HIV-1 cytopathicity was assessed by flow cytometric forward scatter-side scatter (FSC-SSC) profiles (Coulter EPICS XL-MCL and FACScalibur) of 10,000 live cells daily throughout the course of infection. Simultaneously, these samples were stained with 1:200-diluted anti-mouse HSA phycoerythrin (PE) (CD24; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) to quantitate the level of infection. Intracellular HIV-1 p24 antigen production was measured by using cells permeabilized with the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells fixed in formaldehyde were incubated in 1:200-diluted anti-p24 PE antibody, KC57-RD1 (Coulter), at 4°C for 30 min, washed twice, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Apoptosis assays.

Infected and mock-infected Jurkat cells were treated with 100 ng of anti-CD95 antibody and CH11 (Kamiya Biomedical, Thousand Oaks, Calif.) per ml for 6 h; parallel control cultures received no antibody treatment. Similarly, infected and mock-infected H9 cells were treated with 0.75 μg of staurosporine (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, Calif.)/ml for 16 h or anti-CD95 and APO-1 (Kamiya Biomedical) at 50 ng/ml plus 1% protein A (Sigma) for 16 h.

(i) Annexin V.

Phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane was quantitated by incubating 106 cells in 1:30 diluted fluoresceinated Annexin V (Pharmingen) in Annexin V binding buffer (10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 5 mM KCl; 1 mM MgCl2; 2 mM CaCl2) for 15 min. Cells were washed prior to analysis on a Coulter EPICS XL-MCL.

(ii) TUNEL.

DNA fragmentation was measured by using the APO-DIRECT assay (Pharmingen/Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, suspension cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, incubated for 10 min at room temperature, pelleted, and resuspended in 80% ethanol. Terminal 3′-OH fragments were labeled by incubation with fluorescein-conjugated dUTP and deoxynucleotidyl transferase and analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) detection performed with kits from other manufacturers, such as the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), yielded similar results.

(iii) Caspase activity.

Whole-cell protein extracts prepared by lysis in 140 mM NaCl-10 mM Tris (pH 7.2)-2 mM EDTA-1% NP-40 were assessed for caspase activity by incubation with DEVD-4-methyl-7-amino-coumarin (DEVD-AMC) and fluorometric measurement of released AMC.

(iv) APO2.7.

Exposure of the mitochondrial membrane protein, 7A6 antigen, was detected with the APO2.7 antibody (Immunotech/Coulter, Marseilles, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In short, 106 cells were pelleted and resuspended in 100 μg of digitonin/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.02 M phosphate with 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.4]) with 2.5% fetal calf serum and 0.1% NaN3 (PBSF) for 20 min on ice. Samples were then washed in PBSF, incubated in 1:5 diluted APO2.7-PE for 15 min at room temperature, and washed again prior to analysis on a FACSCalibur apparatus (Becton Dickinson). To exclude nonspecific binding of the staining reagents to dead or necrotic cells, all quantitative flow cytometric analyses were gated on a “viable” FSC-SSC population such that the data reflect only cells that are viable or early in the apoptotic process, prior to changes in cell size, granularity, or membrane permeability.

Immunoblotting.

Whole-cell protein extracts of infected H9 cells were prepared by lysis for 30 min on ice in modified Laemmli buffer (60 mM Tris, pH 6.8; 10% glycerol; 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]), followed by sonication. The detergent-insoluble fraction was pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm in an Eppendorf centrifuge for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants were boiled in SDS loading buffer. Samples containing equal cell numbers were electrophoresed on a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine-SDS gel (Novex) and blotted onto nitrocellulose by using a semidry transfer apparatus. The blot was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 0.1% PBS-Triton X-100 (PBS-T) for 30 min and probed with a 1:200 dilution of mouse anti-PARP [poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; Research Diagnostics], followed by donkey anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.) at a 1:10,000 dilution, with three washes in PBS-T after each incubation. All antibody probes were performed in 5% nonfat dry milk-0.1% PBS-T. The blot was then stripped in 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol-62.5 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8)-2% SDS and reprobed with rabbit anti-D4-GDI (Pharmingen) at a 1:5,000 dilution and with donkey anti-rabbit HRP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) at a 1:7,500 dilution. Bands were imaged with SuperSignal HRP substrate (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.). Extracts of Jurkat MC159-hemagglutinin (HA) and Bcl-xL stable clones were blotted similarly, following lysis in buffer containing 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.2), 2 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40. Membranes were probed with 1:1,000-diluted anti-HA HRP monoclonal antibody (Berkeley Antibody Co., Inc.) or 1:200 mouse anti-Bcl-xL (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, Md.) plus donkey anti-mouse HRP, respectively.

Kill assays.

Functional protection afforded by MC159 stable expression against death-receptor apoptosis inducers was determined by treatment with APO-1-3 anti-Fas antibody at 800 ng (Kamiya Biomedical Co., Seattle, Wash.)/ml and 1% protein A (Sigma), TRAIL at 100 ng/ml in the presence of 2 μg of Enhancer (Alexis Co., San Diego, Calif.)/ml, and 10 ng of TNF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.)/ml with 1 μg of cycloheximide (Sigma)/ml. Then, 105 cells were plated per well in a 96-well round-bottom plate, treated for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, and analyzed for viable cell loss relative to untreated controls by the number of live (large forward scatter, propidium iodide [PI] negative) events per constant time on a FACScan. All samples were performed in duplicate. Similarly, Bcl-xL-expressing clones and vector alone clones were subjected to irradiation (1,000 rads), 4 and 8 mM NaB (Sigma), or 800 ng of APO-1 anti-Fas antibody/ml plus 1% protein A. Irradiated cells were harvested at 2, 4, and 6 days after treatment; NaB- and anti-Fas-treated cells were harvested after 48 h. Protection was measured by the percentage of viable cells at these time points.

RESULTS

HIV-1 infection in CD4+ T-cell lines is highly cytopathic.

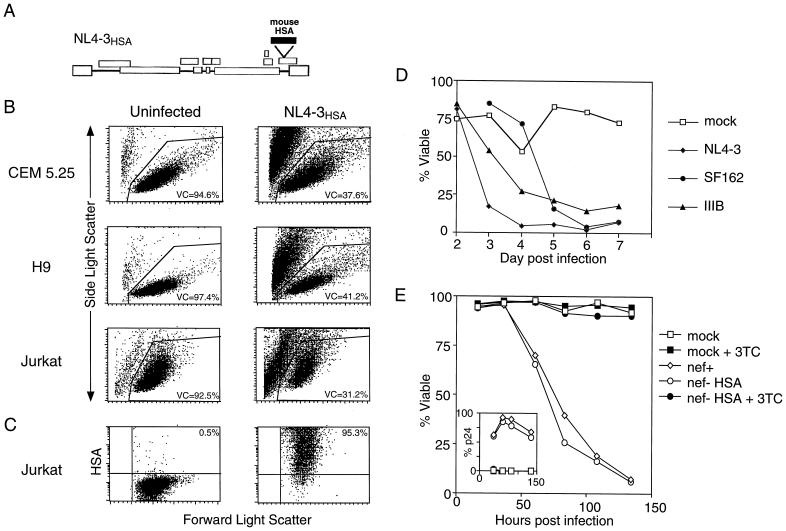

To investigate cell death caused by HIV-1, we infected human T-cell lines, including CEM 5.25, H9, and Jurkat, with the laboratory-adapted NL4-3HSA strain of HIV-1 harboring the coding sequence for mouse heat-stable antigen (HSA) in place of the viral gene nef (21). This allowed us to precisely distinguish infected and uninfected cells by flow cytometric analysis of HSA expression (Fig. 1A). NL4-3 utilizes the CXCR4 chemokine coreceptor for viral entry and fusion and therefore infects and potentially elicits cytopathic effects in CD4+ T lymphoid cell lines (1). We found that cell viability declined severely in all infected cultures within 3 to 11 days postinfection (p.i.) compared to mock-infected negative controls (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the dead cell debris in these cultures incorporated PI (data not shown), which is characteristic of a cell that has lost membrane integrity and undergone lysis either by necrosis or secondary necrosis after apoptosis. The death was positively correlated with the degree of viral infection as indicated by the number of HSA-positive cells, as well as the intensity of HSA staining, and was also observed in CD4+ peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) (33). We consistently observed cell death after >95% HSA surface staining selectively within the infected cells that most highly expressed the provirus as indicated by very high levels of surface HSA (Fig. 1C). However, the cytopathic effect in no way depended on the NL4-3HSA molecular clone, since we observed similar or equivalent prominent cell death effects with other HIV-1 laboratory-adapted strains, SF162, IIIB, and the standard NL4-3 virus that lacks the mouse HSA gene insert and thus had intact nef genes (Fig. 1D and E). In the latter experiments, death also correlated with the degree of viral infection since it occurred preferentially in cells expressing high levels of p24 assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

HIV-1 infection results in substantial cytopathicity in T cells. CEM 5.25, H9, and Jurkat T-cell lines were infected and monitored for changes in viability. (A) Diagram of the HIV-1 NL4-3HSA construct commonly used in our infection system. The mouse gene encoding HSA is inserted into the coding region of nef, an accessory HIV-1 gene. (B) Plots represent forward and side scatter profiles of uninfected and NL4-3HSA-infected cultures of CEM 5.25 (day 3 p.i.), H9 (day 11 p.i.), and Jurkat (day 7 p.i.). Cells were infected by centrifugation for 2 h in the presence of viral supernatant and Polybrene (1 μg/ml). The percent viable cells (VC) reflected by total events within the live gate, as determined by size and granularity, is indicated. The VC gate was confirmed by PI incorporation by the dead cell debris. A total of 10,000 live events were collected per panel. (C) Single-stain HSA dot plots were generated by gating on the live Jurkat population in both the uninfected and infected samples from panel B, quantitating the level of infection. The fraction of HSA-positive cells is given in the right upper quadrant. (D) Death curves of CEM 5.25 cells after infection with three laboratory strains of HIV-1—NL4-3, SF162, and IIIB—were compiled by daily flow cytometric analysis of cultures as described for panel B. (E) Death and infection curves of Jurkat cells after infection with NL4-3 (nef+) and NL4-3HSA (nef− HSA) with or without 3TC (10 μM). The fraction of viable cells was determined as described for panel B, and the fraction of infected cells, as measured by intracellular p24 staining, is shown in the inset.

HIV-infected cells maintain membrane phospholipid asymmetry during cell death.

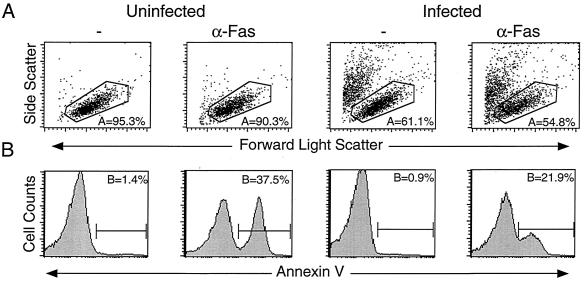

To characterize the cytopathic effect, we performed various assays to detect the hallmarks of apoptosis on highly infected cultures with declining cell viability. Extracellular PS flux from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane represents an early marker of apoptosis that can be detected by Annexin V staining (11, 54). Uninfected cells treated with anti-Fas antibody yielded a high proportion of annexin-binding cells (Fig. 2). In contrast, during the course of HIV-1 infection, we were surprised to find little or no annexin binding (Fig. 2). In addition, the infected cells were susceptible to Fas-induced PS display, demonstrating that HIV-1-infected cells can expose PS when provided with an appropriate stimulus (Fig. 2 and 7B). It is important to note that these cultures were treated with the anti-Fas for only 5 to 8 h, which causes the commitment to apoptosis, as indicated by PS display, but not complete cell death, so that most annexin-staining cells remain within the viable gate. Furthermore, it is essential to measure annexin staining only on cells within the viable gate to avoid the artifactual staining of dying cells that have lost membrane integrity and expose PS irrespective of whether the cells were caused to die by apoptotic, necrotic, or other uncharacterized processes (58). Examination of other cell lines revealed 10 to 50% annexin binding in some HIV infections; however, this varied from culture to culture in both infected and uninfected cells (see below). CD4+ PBLs infected with NL4-3 in vitro show similar low levels (5 to 10%) of annexin binding despite high levels of infection and significant loss in viability (33). This lack of correlation between PS display on cells within the viable gate and the degree of virus-induced cytopathicity in this system raised a question as to whether apoptosis mechanisms were essential for the profound cell death caused by HIV infection.

FIG. 2.

HIV-1-infected cells fail to translocate PS to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. Jurkat T cells were mock infected or were infected with NL4-3 for 2 days and treated with anti-Fas (CH11; 100 ng/ml) for 6 h. Cultures were stained for PS flux in 2 mM Ca2+ Annexin V-FACS buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Forward and side scatter profiles show the percent live cells in each culture, as determined by size and granularity. (B) Gating on the live cell events collected in panel A, with Annexin V positivity quantitated by histogram analysis. A total of 100,000 live events were acquired per panel.

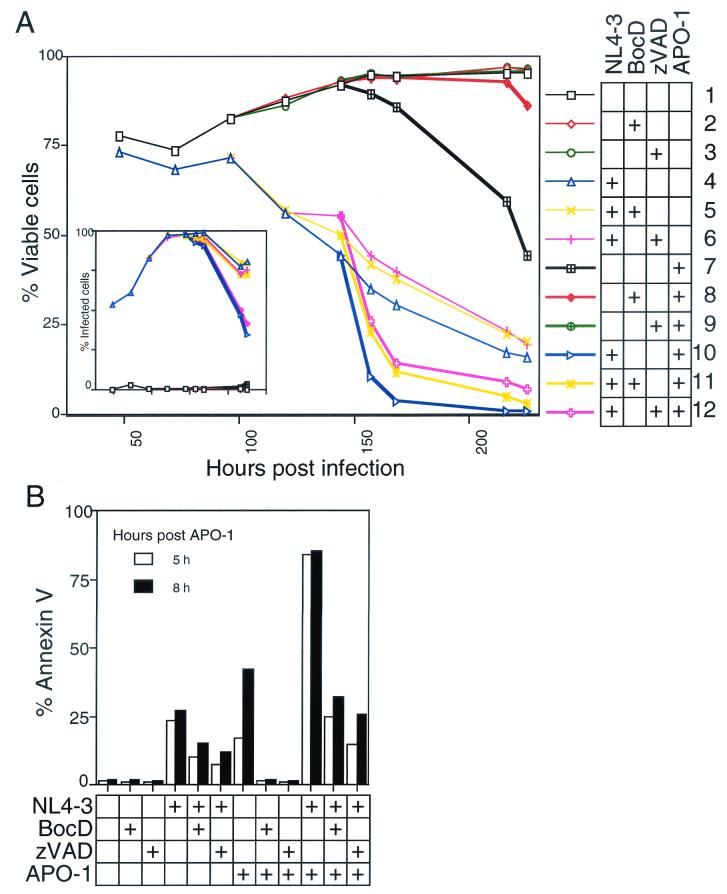

FIG. 7.

Caspase inhibitors fail to prevent HIV-1 cytopathicity. (A) The viability of Jurkat cells mock infected or HIV-1 infected (NL4-3HSA), with or without BocD-fmk or zVAD (100 μM), and in the absence or presence of an apoptosis inducer, APO-1 (25 ng/ml + 1% protein A), is shown against time. APO-1 was added 148 h p.i. The insert indicates the level of infection, as measured by the percent HSA-positive viable cells. (B) In an infection similar to that described for panel A, Jurkat cells were examined for extracellular PS flux by Annexin V staining. More than 90% of the cells were HSA positive at the time of APO-1 addition. Flow cytometric analysis was performed after treatment with APO-1. All analyses were performed on 10,000 live events, as determined by FSC-SSC analysis. Graphs are representative of three or more independent experiments.

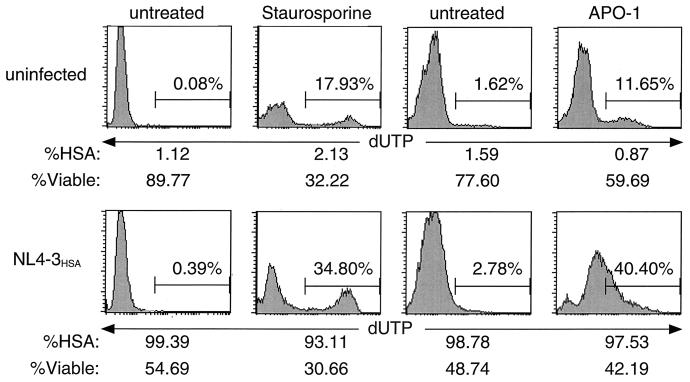

Infected cells show minimal TUNEL staining.

DNA fragmentation is a hallmark of intermediate-stage apoptosis resulting from caspase-dependent activation of endonucleases that degrade the chromatin structure into discrete fragments (64). Reports of apoptotic cell death in HIV-1 infection typically show 10 to 15% of the cells display DNA fragmentation, as measured by TUNEL (4, 15, 39). However, in systems such as in vitro expression of HIV-1 Env, no apoptosis was detected by TUNEL (10). In our infection system, we detected a minimal level (<2%) of DNA fragmentation in infected H9 cultures despite high levels of cell death (Fig. 3). This is in contrast to cells induced to undergo apoptosis by staurosporine or anti-Fas, where distinct cell populations with a substantial TUNEL signal could be observed. The fraction of TUNEL-positive cells was even greater in infected cultures treated with staurosporine or anti-Fas. Since these data contrasted with previous reports (15), we made high titer viral stocks of the original HIV IIIB strain used previously and repeated the experiment but still obtained little TUNEL signal (data not shown). These data suggest that cells highly infected with HIV-1 may be especially sensitive to apoptogenic stimuli, but the HIV-1 infection itself does not potently induce the DNA fragmentation typically found in apoptosis.

FIG. 3.

Nuclear chromatin degradation leading to the development of a TUNEL signal is not evident during HIV infection. Panels represent terminal fluorescein-conjugated dUTP nucleotide labeling (TUNEL) of fragmented DNA in H9 cells. Cells were either mock infected or infected with NL4-3HSA and assayed for TUNEL positivity when HIV-associated cytopathicity was evident (10 days p.i.). As positive controls, subsets of each culture were treated with the apoptosis inducers, staurosporine (0.75 μg/ml) for 16 h or APO-1 (anti-Fas, 50 ng/ml) for 16 h. Prior to fixation for TUNEL staining, cell viability and infection level were measured by flow cytometric analysis of forward scatter-side scatter profiles and surface HSA expression among viable cells, respectively. All analyses were performed on 10,000 live events.

HIV infection does not induce caspase activation.

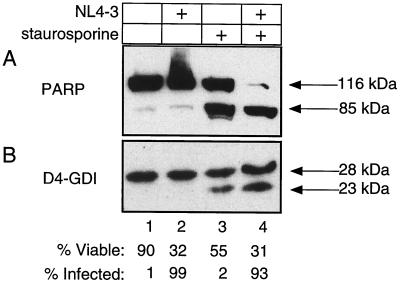

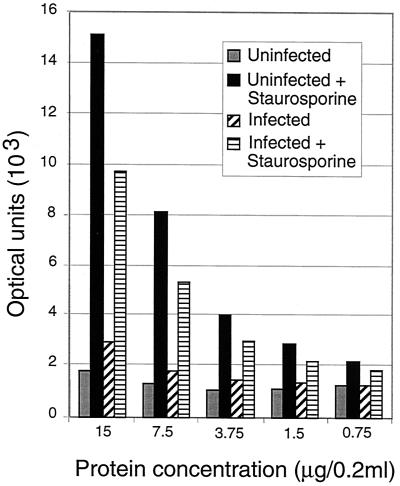

The principal characteristic of apoptosis is the proteolytic activation of caspases (46). To assess caspase activation, we studied the cleavage patterns of two prototypic cellular caspase substrates, PARP and D4-GDI (41). Consistent with previous findings (31), these proteins remain intact in infected cultures of H9 cells (Fig. 4). Despite a striking loss of viability in the HIV-1-infected sample (>60%), we did not detect any increase in the levels of PARP and D4-GDI cleavage products relative to the uninfected culture (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2). Similar to the results obtained with TUNEL and Annexin V staining, we found that infected samples treated with staurosporine displayed marked proteolysis of PARP and D4-DGI, indirectly indicating strong caspase activation (Fig. 4, lane 4). In fact, staurosporine treatment in conjunction with HIV-1 infection reproducibly resulted in nearly complete degradation of PARP, indicating more-robust caspase activation than in staurosporine-treated control cultures (Fig. 4, lane 3 versus 4). We also assayed lysates from the same infections for caspase enzyme activity by using the DEVD-AMC tetrapeptide substrate. Concordant with the above biochemistry and TUNEL data, we failed to detect a significant increase in caspase activity in infected samples relative to mock-infected controls (Fig. 5). Both the uninfected and the infected samples did show increased activity upon treatment with staurosporine, indicating again that the caspase activation machinery was intact in these cells but required a stimulus other than HIV infection to become operative. These data argue against the required involvement of apoptotic pathways that employ caspases in HIV infection.

FIG. 4.

HIV-1-induced cell death fails to activate caspase proteolysis of known cellular substrates. (A) PARP cleavage was detected by immunoblot analysis of the H9 experiment described in legend to Fig. 3. Cells were lysed in 2% SDS-Laemmli buffer. Lanes 1 and 3 represent the mock-infected sample; lanes 2 and 4 represent HIV-1-infected samples. Lanes 3 and 4 were treated with staurosporine (0.75 μg/ml) for 16 h as positive apoptosis controls. Full-length PARP, at 116 kDa, is cleaved to 85 kDa in apoptotic cells. Viability and the level of infection were measured as described for Fig. 3. (B) D4-GDI protein levels of the samples described for panel A were also examined by immunoblotting. The 23-kDa fragment represents the apoptotic cleavage product of D4-GDI.

FIG. 5.

Caspase activity is increased by the apoptosis inducer staurosporine but not by HIV infection. Increasing protein concentrations were used in a caspase assay with DEVD-AMC as a substrate with fluorometric measurement of the released AMC. Protein extracts from various infected and control H9 cell populations from the experiment described in the legend to Fig. 3 are shown. Optical units are arbitrary fluorescence based on a standard curve of free AMC. All values are from duplicate determinations, and the fluorescence could be blocked with a caspase inhibitory peptide, indicating that it is specific enzyme activity.

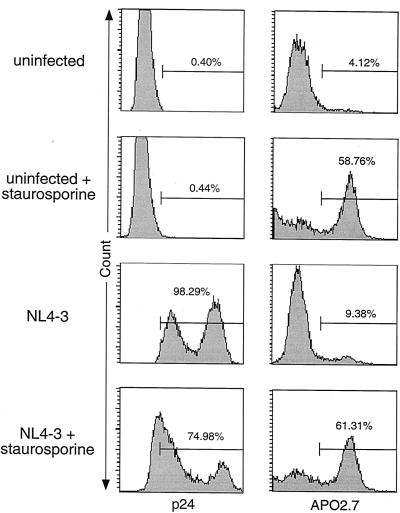

Mitochondrial apoptosis marker antibody APO2.7 does not react with HIV-infected cells.

Apoptotic events can also be detected by intracellular staining for a novel mitochondrial membrane protein recognized by the antibody APO2.7 (30, 66). APO2.7 reactivity is specific for cells undergoing apoptosis and is caused by alterations in the mitochondrial transmembrane potential that expose the APO2.7 target antigen on the outer mitochondrial membrane. HIV-1-infected H9 cells that were permeabilized and stained with APO2.7 show modest evidence of this marker (10%) relative to cultures treated with staurosporine (60%), despite high levels of infection and cell death (Fig. 6). In addition, intracellular p24 staining of these infected H9 samples revealed two distinct cell populations expressing low or high levels of the viral capsid protein. Interestingly, apoptosis induction in the infected culture by staurosporine preferentially deleted the high p24 population, providing additional evidence that there is a greater susceptibility to apoptotic stimuli among the subset of cells that have the greatest expression of the HIV provirus. Nonetheless, the APO2.7 staining cast further doubt on the participation of apoptosis in death induced solely by high level of infection with HIV-1. Similar results were also obtained with PBLs (33).

FIG. 6.

Despite high levels of viral protein expression and cytopathicity, HIV-1-infected H9 cells show little positivity for the apoptotic mitochondrial membrane marker, APO2.7. Intracellular flow cytometric staining for the HIV-1 capsid protein, p24, and the mitochondrial membrane protein recognized by APO2.7 (7A6 antigen) was performed on the H9 experiment described in the legend to Fig. 3. Cells were permeabilized with formaldehyde or digitonin prior to staining for p24 and APO2.7 staining, respectively. All panels represent analysis of 10,000 live events as determined by FSC-SSC analysis.

Caspase inhibitors are unable to prevent HIV-induced cell death.

In each of the foregoing assays, a minimal level of apoptosis was detected in infected cultures. In principle, this could be explained by one of at least two possibilities. On the one hand, apoptosis could be an essential but transient stage of HIV-induced death that occurs rapidly and asynchronously and is not readily apparent in the infected cultures. Alternatively, the modest level of apoptosis we observed in infected cultures may have been due to apoptosis that is randomly and nonspecifically triggered in cultured cells which is perhaps accentuated by the vulnerability of infected cells. To distinguish these possibilities, we carried out a series of experiments with well-characterized inhibitors of apoptosis so that, if apoptosis was essential, even transiently, we would observe a clear protective effect by blocking apoptosis. To test whether caspases, the effectors of apoptosis, play any role in HIV-1 cytopathicity, we compared viability trends in infected cultures with or without the inclusion of the irreversible peptide caspase inhibitors zVAD-fmk and BocD-fmk. At concentrations sufficient to inhibit Fas-induced apoptosis, neither zVAD-fmk nor BocD-fmk blocked HIV-induced cell death in Jurkat T cells (Fig. 7A, compare curves 7, 8, and 9 to curves 4, 5, and 6). The presence of these inhibitors reproducibly increased viability in infected cultures by ca. 10%, indicating that caspases are involved in the death of only a small fraction of cells. The general slope of the viability curve remained unchanged, however, suggesting that HIV-1 kills its host cells primarily by a caspase-independent pathway. We also treated subsets of these cultures with anti-Fas (APO-1) to determine whether peptide caspase inhibitors are equally effective at blocking apoptotic stimuli among HIV-1-infected cells. While uninfected samples cultured with BocD-fmk and zVAD-fmk were fully protected against anti-Fas, viability in parallel infected cells dropped substantially upon anti-Fas stimulation and was only partly reversed by the inhibitors (Fig. 7A). Annexin V surface staining of these cultures indicated that the synergistic cytopathic effect between HIV-1 infection and anti-Fas is associated, at least partially, with PS exposure consistent with apoptosis (Fig. 7B). In the presence of caspase inhibitors, however, PS display is reduced to near-baseline levels for infected, anti-Fas-treated samples, despite an unmitigated decline in viability. This suggests that HIV-1-infected cells are especially sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis but that enhanced death caused by Fas stimulation of infected cells continues to proceed in a largely caspase-independent manner.

HIV-mediated cell death occurs independently of both death receptor- and mitochondrion-mediated apoptosis.

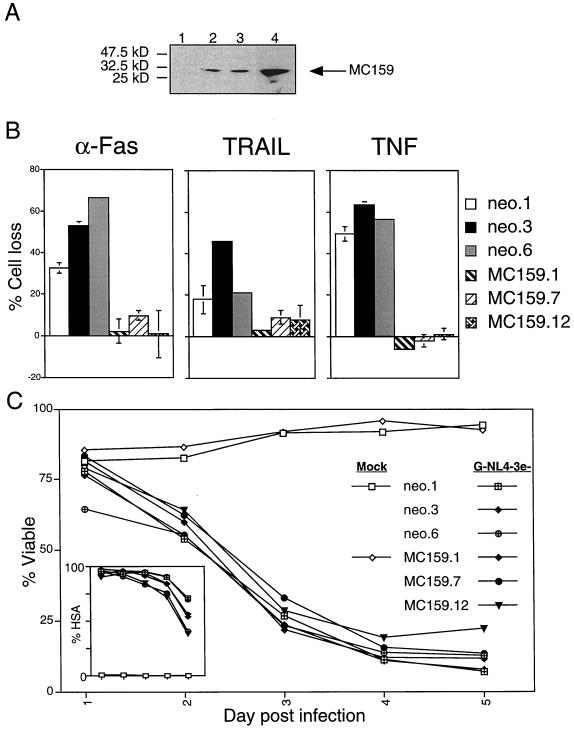

Commercially available caspase inhibitors such as zVAD-fmk and BocD-fmk are not absolutely effective against all caspases, however, and their half-life in aqueous solution is limited to 40 min (16, 59; D. W. Thornberry, unpublished data). Therefore, our conclusion from these inhibition data was limited by the possibility that in the time period after administration of the inhibitor, newly activated caspases could trigger apoptosis. We therefore established T-cell lines in which apoptosis inhibitors were continuously present. We generated stable transfectants of CD4hi Jurkat T cells by using expression constructs encoding protein inhibitors blocking the four main apoptotic pathways. To address the receptor-mediated and DEF-mediated death pathways, we generated stable CD4+ Jurkat T-cell clones expressing the antiapoptotic viral protein MC159 from Molluscum contagiosum (6). MC159 dominantly interferes with apoptotic signaling by binding to DED-containing proteins, thus blocking procaspase-8 recruitment. Jurkat cells were transfected with pCI-neo for selection with or without pCI-MC159 and cloned by limiting dilution. The clones were screened for protein expression by Western immunoblotting, and several clones with increasing amounts of the MC159 protein were further analyzed (Fig. 8A). All vector alone and MC159 clones expressed similar levels of surface CD4 receptor and CXCR4 coreceptor (data not shown). The MC159 clones were substantially protected against apoptosis induced through Fas, TNF receptor, and TRAIL, indicating potent protection against death receptor-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 8B). Despite this resistance to death receptor-induced apoptosis, the cells remained sensitive to death caused by HIV-1 infection (Fig. 8C). These data demonstrate that direct HIV-1 cytopathicity does not depend on DED interactions within the host cell, a finding consistent with previous reports that the Fas pathway is not involved in HIV-1 T-cell killing (15, 47, 65).

FIG. 8.

MC159 expression protects against death receptor-mediated apoptosis but not HIV-1-induced cell death. Jurkat 5.5 cells were stably transfected with MC159 or vector alone (neo), selected in G418medium (400 μg/ml), and cloned from single cells. (A) MC159 expression was detected by immunoblot analysis on 20 μg of whole-cell lysates from selected MC159 (lanes 2 to 4, clones 1, 7, and 12, respectively) and vector alone (lane 1, neo.6) clones subjected to SDS-4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. HA-tagged MC159 was probed with anti-HA antibody, yielding a 30-kDa band corresponding to the size of MC159. Then, 20 μg of protein extract was loaded per lane. (B) Clones were screened in functional assays by treatment with apoptosis inducers that act via extracellular death receptors, anti-Fas (APO-1, 800 ng/ml), TRAIL (100 ng/ml, in the presence of 2 μg of enhancer antibody/ml), and TNF (10 ng/ml, in the presence of 1 μg of cycloheximide/ml). All kill assays were harvested 24 h after treatment and analyzed by flow cytometry for percent cell loss as the number of live events acquired per constant time relative to untreated controls. The error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate samples. (C) Clones testing positive for MC159 expression, as well as three vector alone controls (neo.1, neo.3, and neo.6), were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped NL4-3HSA env− by using our high-efficiency spinfection protocol in the presence of Polybrene (1 μg/ml) and monitored for changes in viability. The inset depicts the level of infection for each culture, as measured by HSA surface expression. Both viability and HSA data were collected by flow cytometric analysis as described for Fig. 1.

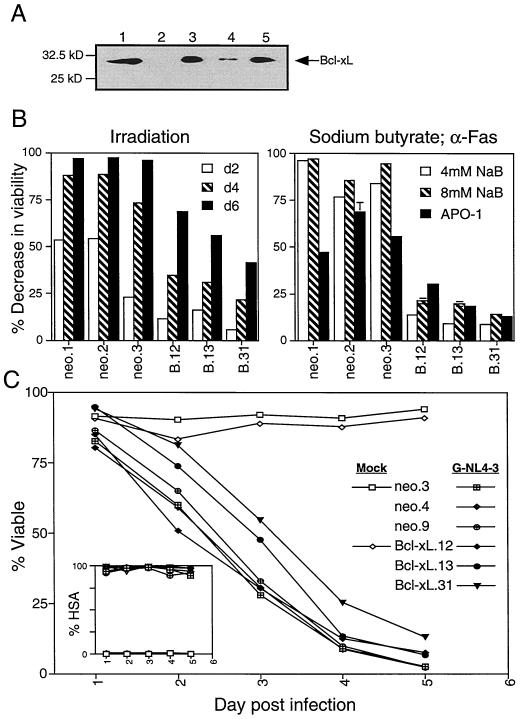

To examine whether the mitochondrial or ER apoptotic pathways participate in HIV-1-induced cell death, we established stable Jurkat T-cell clones overexpressing the mitochondrial antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL. A relative to the oncogene Bcl-2, Bcl-xL inhibits multiple forms of mitochondrially mediated apoptosis in T cells (8). After introduction of the expression construct, clones that overexpress the Bcl-xL protein were isolated (Fig. 9A). These clones showed substantial protection against irradiation and NaB-induced apoptosis (Fig. 9B). Although the expression of Bcl-xL afforded considerable protection against apoptotic stimuli acting via the mitochondrial pathway, as well as anti-Fas (Fig. 9B), the clones were only minimally protected against HIV-1-induced cell death (Fig. 9C). Similar to results observed with Bcl-2 (31), viability was slightly greater among two of the three Bcl-xL transfectants (clones 13 and 31, Fig. 9C) at days 2 and 3 p.i., for example. This 10 to 20% difference reflects a prolonged stage among Bcl-xL transfectants in which infected cells remained enlarged, PI negative, and highly granular (data not shown). Thus, consistent with the slight improvement in viability upon addition of caspase inhibitors (Fig. 7), Bcl-xL expression appears to block a relatively small fraction of the cell death occurring among infected T cells. Bcl-xL clone 12, which failed to exhibit any protection against HIV-1 cytopathicity, expressed relatively higher levels of surface CD4 (data not shown) and therefore most likely succumbed to a more rapid course of infection disguising any protective effects. Thus, neither successful inhibition of apoptosis mediated by death receptors, DEFs, ER, or mitochondrial alterations could prevent the lethal effect of HIV on CD4+ T-cell lines.

FIG. 9.

Jurkat 5.5 Bcl-xL stable transfectants are protected against mitochondrial pathway apoptosis inducers but not HIV-1-induced cell death. Stable Jurkat cell lines were generated by electroporation with 8 μg of vector (pcDNA3) or pcDNA3−Bcl-xL and selection in G418 (800 μg/ml). (A) Bcl-xL expression in Jurkat stable clones (lanes 3 to 5, Bcl-xL0.12, -xL0.13, and Bcl-xL0.31, respectively) relative to a vector alone stable clone (lane 2, neo.3) was detected by Western blot analysis following SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 4 to 20% gel. 293T cells transiently transfected with Bcl-xL were used as a positive control (lane 1). Then, 60 μg of Jurkat extracts was analyzed for each clone; 2 μg was used for 293T lysates. (B) Clones were tested for functional protection from apoptosis inducers that act via the mitochondrial pathway and from anti-Fas. Vector alone (neo.1, neo.2, and neo.3) and Bcl-xL clones (B.12, B.13, and B.31) were irradiated at 1,000 rads and measured for changes in viability relative to untreated controls at 2, 4, and 6 days posttreatment. The graph is representative of two independent experiments. Similarly, the clones were treated with sodium butyrate (NaB, 4 and 8 mM) and anti-Fas (APO-1, 800 ng/ml) and harvested after 48 h. The percent viable cell analysis was performed by flow cytometric quantification of large, PI-negative events. The error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate samples. (C) Bcl-xL and vector alone clones with matched CD4 receptor expression (neo.3, neo.4, and neo.9) were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 (NL4-3HSA) by our high-efficiency spin protocol in the presence of Polybrene (1 μg/ml) and then monitored for changes in viability. Infection level, as determined by surface HSA expression, and viability were measured and analyzed as described for Fig. 1. Graphs are representative of three or more independent experiments.

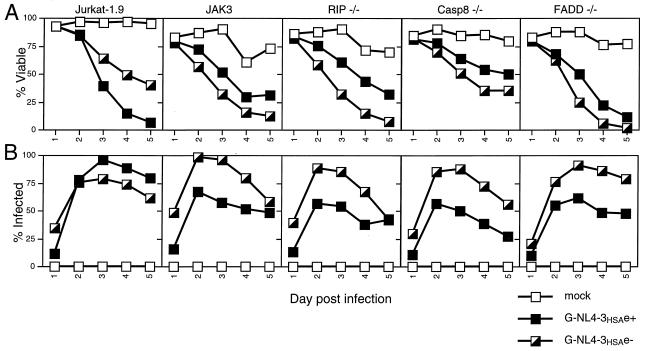

To further explore possible death pathways in the cytopathic effect caused by HIV-1, we infected Jurkat cell lines deficient in capsase-8, FADD, or RIP, all of which have been implicated in apoptosis or an alternate cell death pathway. Caspase-8 and FADD are essential for Fas-induced apoptotic signaling (27, 28), whereas RIP has been shown to be required for a caspase-independent necrotic death pathway initiated by either Fas, TRAIL, or TNF (24). Deficiencies in each of these proteins failed to confer resistance to HIV-1-mediated cytopathicity, since the mutant cell lines died at a comparable rate to wild-type Jurkat cells after infection with vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G)-pseudotyped NL4-3HSA env− virus (Fig. 10A). This is in agreement with the relative lack of protection afforded by peptide caspase inhibitors and MC159 overexpression, as well as the low caspase activity detected in vitro. Variation in susceptibility to the env+ strain of NL4-3HSA among the mutant and JAK3 T-cell lines is due to low CD4 surface expression on these cell lines (data not shown), preventing productive infection beyond VSV-G-mediated viral entry (Fig. 10B). Taken together, these results indicate that the best-known pathways of apoptosis are unable to account for the ability of HIV-1 to cause T-cell lines to die under these culture conditions.

FIG. 10.

Jurkat cells deficient in RIP, caspase-8, or FADD remain susceptible to HIV-1-mediated cytopathicity. Wild-type Jurkat cells, JAK3, CD4hi Jurkat 1.9, and mutant Jurkat T-cell lines were mock infected or were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 (NL4-3HSA env+ and env−; MOI = 0.75, as determined by Poisson distribution) and analyzed daily for viability (A) and fraction of infected cells (B) by flow cytometry. The infection level, as determined by surface HSA expression, and viability were measured and analyzed as described for Fig. 1. The graphs are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this report we show that the cell death process induced by direct HIV-1 infection does not rely on caspase activation and overall is not characteristic of apoptosis. Neither DNA fragmentation nor disruption of membrane phospholipid asymmetry, two established hallmarks of apoptosis (11, 64), were prominent among infected, dying T-cell lines. In addition, these cells fail to exhibit substantial levels of caspase activation, as measured by proteolysis of cellular caspase substrates, PARP and D4-GDI, or by in vitro cleavage of an aspartate-containing peptide. These data clearly suggest that apoptotic cell death does not account for the concurrent cytopathicity observed in HIV-1-infected cultures. Furthermore, peptide and molecular inhibitors of both the major apoptotic pathways were unable to prevent infected cell death. Cells stably expressing MC159, which dominantly interferes with death receptor and death effector filament signaling, were equally susceptible to HIV-1-induced cell death relative to vector alone cell lines. Moreover, HIV-1 cytopathicity was only slightly mitigated by the addition of caspase inhibitors, as well as by Bcl-xL overexpression. Infected cell viability improved by 10 to 15% on average under these conditions, suggesting that a minor population of infected cells could die by apoptosis but that apoptosis is not the predominant mode of cell death. APO2.7 staining of the mitochondrial membrane apoptotic marker revealed similar low levels of apoptotic cells. While minimal levels of apoptosis are detectable by some indicators (primarily those specific for the mitochondrial pathway), the amount of apoptosis observed does not correlate with the massive cytopathicity caused by infection. Thus, we propose that HIV-1 does not inherently induce apoptosis among cells hosting a productive infection, nor is apoptosis required for HIV-1-induced cytopathicity.

Our results provide important insight into the mechanism by which HIV-1 kills its host cells, although these results are not entirely consistent with previous reports documenting HIV-1-induced apoptosis. The discrepancy between our findings and those of other groups may be explained by several possibilities. First, we examined direct single-cell killing rather than bystander- or syncytium-associated cell death. Many reports documenting signs of apoptosis showed that cocultured uninfected CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells display characteristics of apoptosis similar to those of infected CD4+ T cells (22, 32, 39), suggesting that apoptosis observed in these studies is not due to direct HIV-1 infection but potentially to other adverse conditions within the cultures. Furthermore, in situ labeling of lymph nodes from HIV-infected patients has revealed that apoptosis occurs primarily in uninfected bystander cells and not in productively infected cells, possibly due to general immune activation (13, 40). In light of the CD4+ T-cell rapid turnover model (23) and the fact that AIDS pathogenesis results from a specific decline in CD4+ T cells, the death of uninfected CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets may not describe critical steps in HIV-1 infection. As such, our data, derived from CD4+ T-cell cultures that reached >95% infection, primarily reflect direct HIV-1 cytopathicity.

Second, the methods used to detect apoptosis analyzed in this and other reports vary in their ability to quantitate the fraction of cells expressing apoptotic features and then correlate them with this infection. Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation, for example, may not accurately differentiate between apoptosis and necrosis and may be inconclusive without adjacent necrotic and apoptotic controls (5). In fact, DNA fragmentation is observed during both forms of death, although degradation resulting from necrosis is more random than that resulting from apoptosis. Furthermore, it is difficult to demonstrate that DNA fragmentation occurs in conjunction with direct infection. Unless the infection system is extremely efficient, this assay depicts biochemical characteristics of a mixed population, including uninfected and infected cells, whose identity cannot be linked to the observed DNA ladder. Although some studies have attempted to correlate DNA fragmentation with direct infection by use of dual-parameter flow cytometry analyzing TUNEL staining with GFP-tagged HIV-1 (22), high levels of background fluorescence among uninfected samples make these results difficult to interpret. In particular, dead cells that have already lost membrane integrity may autofluoresce, as well as stain positive, in apoptosis assays such as Annexin V staining, which binds to PS, which is usually restricted to the inner leaflet of the cell membrane. To address this issue, all of our flow cytometric analyses were performed exclusively on cells with intact membranes in highly infected (>95%) cultures. This minimizes the possibility of nonspecific reaction with apoptosis detection reagents and ensures that our results characterize infected cell death.

Other reasons that account for the difference between our results and previous studies on HIV-1 apoptosis may relate to matters of interpretation. A vast and growing literature indicates that apoptosis is not manifested by a single cellular change but rather by a constellation of cellular alterations that occur in a concerted manner. At the center of these changes is the activation, in most cell types and under most conditions, of caspases (45). This has been well documented, especially for T lymphocytes (34). In contrast, it is very difficult to distinguish the mode of death based on a single parameter. For example, TUNEL signal, a widely used marker of apoptosis, has been also found to occur in necrotic death (14, 36, 51). Annexin staining, another widely used indicator of apoptosis, can be displayed in virtually any type of death depending on how the analysis is carried out (58). This is because it is essential to evaluate annexin staining by using proper gating on cells with intact plasma membrane at early stages of apoptosis. Once the membrane integrity is compromised, whether due to the leakage of PS to the cell exterior or to the ingress of the annexin reagent to the cell interior, cells become uniformly stained with annexin irrespective of the mode of death, thereby eliminating its specificity for apoptosis. Even caspases may be activated for the purposes of cytokine maturation rather than as part of a cellular death program (60). Therefore, the reliance on a single indicator of apoptosis in many previous studies is insufficient evidence for the apoptosis induction by HIV-1. This interpretative problem is compounded by reports that show only a minor fraction of cells exhibiting the putative marker of apoptosis, since we, and others previously, have documented that the cytopathic effect inflicted by HIV-1 is massive and can affect essentially all infected cells within a short time. Careful quantitation of the numbers of dead versus apoptotic cells would be required in many previous studies in order to determine the significance of apoptosis in these systems. Finally, we examined the morphological characteristics of the HIV-1 cytopathic effect on T cells and found that, compared to the morphology of apoptotic T cells generated by Fas or T-cell receptor stimulation, there is no resemblance. In the accompanying paper, we document these differences by electron microscopy (see reference 33). Thus, direct HIV-1 cytopathicity bears neither the morphological nor the molecular attributes of apoptosis.

We have carefully considered our observation that we occasionally do observe a small amount of apoptosis induction—in assays such as Annexin V binding, TUNEL (data not shown), and APO2.7 staining—that typically ranges from 5 to 15%. These low levels of apoptosis could be explained by the following two possible kinetic models. (i) The primary mode of infected cell death is via apoptosis, but the window during which cells exhibit apoptotic features is narrow and thus only a small amount of apoptosis is detected at any give time. (ii) Apoptosis represents an epiphenomenon that occurs among a minor subset of infected cells, whereas an alternate pathway is responsible for the death of the bulk of the population. If apoptosis is a transient stage in HIV-induced cell death, then inhibitors of apoptosis should abrogate the cytopathic effect. In contrast, apoptosis blockers would only slightly improve cell viability under the epiphenomenon hypothesis. The latter accurately describes what we observed upon introducing peptide caspase inhibitors or overexpressing the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL in our infection system, supporting the model that infected cell death by apoptosis represents an incidental death pathway at most. Similarly, other apoptosis-inhibiting proteins, Bcl-2 and E1B 19K, have been found to only slightly mitigate viability among HIV-1-infected Jurkat cells (2, 31). Other studies in which Bcl-xL has been shown to significantly reduce apoptosis due to HIV-1 infection are confounded by lower infection in the Bcl-xL-expressing samples (37). It is also possible that Bcl-xL overexpression partially protects against HIV-induced necrotic cell death, since both Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL can block necrosis as well as apoptosis, but even if this is the case, the level of blockade observed is low (57). Moreover, disrupting apoptosis signaling through death receptors on the cell surface by MC159 stable expression, FADD mutation, or capsase-8 mutation had no impact on the cells' susceptibility to HIV-1 cytopathicity. RIP deficiency was equally ineffective at impairing HIV-1-induced cell death. These data not only further support the conclusion that apoptosis is not the primary cause of death for HIV-1-infected T cells, but they implicate a form of caspase-independent necrosis that does not rely on RIP (24). One possibility is that the death pathway induced by HIV-1 converges with RIP-mediated necrosis at a point downstream of RIP involvement.

Although we do not observe notable apoptotic cell death initiated by HIV-1 infection alone, cells productively infected with the virus become more sensitive to apoptosis induced by other stimuli, such as anti-Fas or staurosporine. Furthermore, the increased susceptibility to death inducers can be characteristic not only of apoptosis but also of caspase-independent death when the analyses are conducted in the presence of caspase inhibitors. This suggests that infected cells exist in a compromised state whereby subjecting them to further insults, such as apoptotic stimuli, may result in either enhanced potency of the apoptosis inducer or exacerbate the cytopathicity of HIV-1. Several possible mechanisms may account for these observations. For example, the insertion of Gag in the plasma membrane could accelerate signaling across the membrane, resulting in more rapid induction of apoptosis upon cross-linking of surface death receptors. It is also possible that HIV-1 infection is toxic to the mitochondrion and thereby lowers the threshold at which the permeability transition pore opens and releases apoptogenic proteins. Alternatively, infection may have a direct effect on caspases or caspase substrates that facilitates activation of the apoptotic machinery. It is important to recognize that, although we consider apoptosis enhancement to be a significant effect, apoptosis induction is not necessary for the powerful cytopathic effect that HIV-1 has upon T cells.

We have focused on caspase-dependent apoptosis because, for T cells, caspases appear to be required for the classic manifestations of apoptosis in the best-defined systems. Since our HIV-1-infected cultures displayed neither significant hallmarks of apoptosis nor caspase activation, whether or not caspase-independent pathways of programmed cell death exist has little bearing on our conclusions. In light of our data, future efforts to elucidate the viral component responsible for HIV-1 cytopathicity may not benefit from studies of apoptosis. Also, it is noteworthy that neither the accessory protein, Nef, nor the glycoprotein, Env, is necessary for the induction of infected-cell death, as the NL4-3HSA strain, which lacks Nef, retains cytotoxic properties with or without Env (Fig. 8). In addition, these data represent experiments performed entirely in cell lines, and it is possible that apoptosis may be more important in HIV-infected primary T lymphocytes. For this reason, we conducted comparable studies in PBLs with similar findings (33). Further studies examining the interaction between viral proteins and the host cell will be necessary to elucidate the precise mechanism by which HIV-1 kills infected T cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ned Landau and Theresa Gurney for plasmids, cells, and advice during the initiation of this project. We thank Anthony Fauci and members of his laboratory for use of P3 research facilities and for helpful advice and encouragement. We are also grateful to John Coffin, Eric Freed, Steve Hughes, and Malcolm Martin for advice and assistance, as well as Francis Chan, Richard Siegel, and Lixin Zheng for helpful insights and inspiring discussions and Keiko Sakai for critical reading of the manuscript.

D.L.B. is a participant in the FAES (NIH)-Johns Hopkins University Cooperative Graduate Program in Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoni, B. A., P. Sabbatini, A. B. Rabson, and E. White. 1995. Inhibition of apoptosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected cells enhances virus production and facilitates persistent infection. J. Virol. 69:2384-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banda, N. K., J. Bernier, D. K. Kurahara, R. Kurrle, N. Haigwood, R. P. Sekaly, and T. H. Finkel. 1992. Crosslinking CD4 by human immunodeficiency virus gp120 primes T cells for activation-induced apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 176:1099-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartz, S. R., and M. Emerman. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat induces apoptosis and increases sensitivity to apoptotic signals by upregulating FLICE/caspase-8. J. Virol. 73:1956-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Sasson, S. A. 1995. Anatomical methods in cell death. Methods Cell Biol. 46:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertin, J., R. C. Armstrong, S. Ottilie, D. A. Martin, Y. Wang, S. Banks, G. H. Wang, T. G. Senkevich, E. S. Alnemri, B. Moss, M. J. Lenardo, K. J. Tomaselli, and J. I. Cohen. 1997. Death effector domain-containing herpesvirus and poxvirus proteins inhibit both Fas- and TNFR1-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1172-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitzer, M., F. Prinz, M. Bauer, M. Spiegel, W. J. Neubert, M. Gregor, K. Schulze-Osthoff, and U. Lauer. 1999. Sendai virus infection induces apoptosis through activation of caspase-8 (FLICE) and caspase-3 (CPP32). J. Virol. 73:702-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boise, L. H., M. Gonzalez-Garcia, C. E. Postema, L. Ding, T. Lindsten, L. A. Turka, X. Mao, G. Nunez, and C. B. Thompson. 1993. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell 74:597-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonzon, C., and H. Fan. 1999. Moloney murine leukemia virus-induced preleukemic thymic atrophy and enhanced thymocyte apoptosis correlate with disease pathogenicity. J. Virol. 73:2434-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao, J., I. W. Park, A. Cooper, and J. Sodroski. 1996. Molecular determinants of acute single-cell lysis by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 70:1340-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadok, V. A., D. R. Voelker, P. A. Campbell, J. J. Cohen, D. L. Bratton, and P. M. Henson. 1992. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J. Immunol. 148:2207-2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fauci, A. S. 1988. The human immunodeficiency virus: infectivity and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science 239:617-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel, T. H., G. Tudor-Williams, N. K. Banda, M. F. Cotton, T. Curiel, C. Monks, T. W. Baba, R. M. Ruprecht, and A. Kupfer. 1995. Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat. Med. 1:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujikawa, D. G., S. S. Shinmei, and B. Cai. 2000. Kainic acid-induced seizures produce necrotic, not apoptotic, neurons with internucleosomal DNA cleavage: implications for programmed cell death mechanisms. Neuroscience 98:41-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi, R. T., B. K. Chen, S. E. Straus, J. K. Dale, M. J. Lenardo, and D. Baltimore. 1998. HIV-1 directly kills CD4+ T cells by a Fas-independent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 187:1113-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Calvo, M., E. P. Peterson, B. Leiting, R. Ruel, D. W. Nicholson, and N. A. Thornberry. 1998. Inhibition of human caspases by peptide-based and macromolecular inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32608-32613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gervaix, A., D. West, L. M. Leoni, D. D. Richman, F. Wong-Staal, and J. Corbeil. 1997. A new reporter cell line to monitor HIV infection and drug susceptibility in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4653-4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibellini, D., A. Caputo, C. Celeghini, A. Bassini, M. La Placa, S. Capitani, and G. Zauli. 1995. Tat-expressing Jurkat cells show an increased resistance to different apoptotic stimuli, including acute human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Br. J. Haematol. 89:24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gougeon, M. L., and L. Montagnier. 1993. Apoptosis in AIDS. Science 260:1269-1270. (Erratum, 260:1709.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groux, H., G. Torpier, D. Monte, Y. Mouton, A. Capron, and J. C. Ameisen. 1992. Activation-induced death by apoptosis in CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected asymptomatic individuals. J. Exp. Med. 175:331-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He, J., S. Choe, R. Walker, P. Di Marzio, D. O. Morgan, and N. R. Landau. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J. Virol. 69:6705-6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbein, G., C. Van Lint, J. L. Lovett, and E. Verdin. 1998. Distinct mechanisms trigger apoptosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and in uninfected bystander T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 72:660-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho, D. D., A. U. Neumann, A. S. Perelson, W. Chen, J. M. Leonard, and M. Markowitz. 1995. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature 373:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holler, N., R. Zaru, O. Micheau, M. Thome, A. Attinger, S. Valitutti, J. L. Bodmer, P. Schneider, B. Seed, and J. Tschopp. 2000. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat. Immunol. 1:489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, D. C., S. Cory, and A. Strasser. 1997. Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and adenovirus protein E1B19kD are functionally equivalent in their ability to inhibit cell death. Oncogene 14:405-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaworowski, A., and S. M. Crowe. 1999. Does HIV cause depletion of CD4+ T cells in vivo by the induction of apoptosis? Immunol. Cell Biol. 77:90-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juo, P., C. J. Kuo, J. Yuan, and J. Blenis. 1998. Essential requirement for caspase-8/FLICE in the initiation of the Fas-induced apoptotic cascade. Curr. Biol. 8:1001-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juo, P., M. S. Woo, C. J. Kuo, P. Signorelli, H. P. Biemann, Y. A. Hannun, and J. Blenis. 1999. FADD is required for multiple signaling events downstream of the receptor Fas. Cell Growth Differ. 10:797-804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimpton, J., and M. Emerman. 1992. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated beta-galactosidase gene. J. Virol. 66:2232-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koester, S. K., P. Roth, W. R. Mikulka, S. F. Schlossman, C. Zhang, and W. E. Bolton. 1997. Monitoring early cellular responses in apoptosis is aided by the mitochondrial membrane protein-specific monoclonal antibody APO2.7. Cytometry 29:306-312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolesnitchenko, V., L. King, A. Riva, Y. Tani, S. J. Korsmeyer, and D. I. Cohen. 1997. A major human immunodeficiency virus type 1-initiated killing pathway distinct from apoptosis. J. Virol. 71:9753-9763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurent-Crawford, A. G., B. Krust, S. Muller, Y. Riviere, M. A. Rey-Cuille, J. M. Bechet, L. Montagnier, and A. G. Hovanessian. 1991. The cytopathic effect of HIV is associated with apoptosis. Virology 185:829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenardo, M. J., S. B. Angleman, V. Bounkeua, J. Dimas, M. G. Duvall, M. B. Graubard, F. Hornung, M. C. Selkirk, C. K. Speirs, C. Trageser, J. O. Orenstein, and D. L. Bolton. 2002. Cytopathic killing of peripheral blood CD4+ T lymphocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 appears necrotic rather than apoptotic and does not require env. J. Virol. 76:5082-5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenardo, M., K. M. Chan, F. Hornung, H. McFarland, R. Siegel, J. Wang, and L. Zheng. 1999. Mature T lymphocyte apoptosis--immune regulation in a dynamic and unpredictable antigenic environment. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:221-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, C. J., D. J. Friedman, C. Wang, V. Metelev, and A. B. Pardee. 1995. Induction of apoptosis in uninfected lymphocytes by HIV-1 Tat protein. Science 268:429-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangili, F., C. Cigala, and G. Santambrogio. 1999. Staining apoptosis in paraffin sections: advantages and limits. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 21:273-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall, W. L., R. Datta, K. Hanify, E. Teng, and R. W. Finberg. 1999. U937 cells overexpressing bcl-xl are resistant to human immunodeficiency virus-1-induced apoptosis and human immunodeficiency virus-1 replication. Virology 256:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCloskey, T. W., M. Ott, E. Tribble, S. A. Khan, S. Teichberg, M. O. Paul, S. Pahwa, E. Verdin, and N. Chirmule. 1997. Dual role of HIV Tat in regulation of apoptosis in T cells. J. Immunol. 158:1014-1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyaard, L., S. A. Otto, R. R. Jonker, M. J. Mijnster, R. P. Keet, and F. Miedema. 1992. Programmed death of T cells in HIV-1 infection. Science 257:217-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muro-Cacho, C. A., G. Pantaleo, and A. S. Fauci. 1995. Analysis of apoptosis in lymph nodes of HIV-infected persons. Intensity of apoptosis correlates with the general state of activation of the lymphoid tissue and not with stage of disease or viral burden. J. Immunol. 154:5555-5566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Na, S., T. H. Chuang, A. Cunningham, T. G. Turi, J. H. Hanke, G. M. Bokoch, and D. E. Danley. 1996. D4-GDI, a substrate of CPP32, is proteolyzed during Fas-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 271:11209-11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagata, S., and P. Golstein. 1995. The Fas death factor. Science 267:1449-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakagawa, T., and J. Yuan. 2000. Cross-talk between two cysteine protease families. Activation of caspase-12 by calpain in apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 150:887-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakagawa, T., H. Zhu, N. Morishima, E. Li, J. Xu, B. A. Yankner, and J. Yuan. 2000. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature 403:98-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicholson, D. W. 1999. Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 6:1028-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholson, D. W., and N. A. Thornberry. 1997. Caspases: killer proteases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:299-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noraz, N., J. Gozlan, J. Corbeil, T. Brunner, and S. A. Spector. 1997. HIV-induced apoptosis of activated primary CD4+ T lymphocytes is not mediated by Fas-Fas ligand. AIDS 11:1671-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plymale, D. R., D. S. Tang, A. M. Comardelle, C. D. Fermin, D. E. Lewis, and R. F. Garry. 1999. Both necrosis and apoptosis contribute to HIV-1-induced killing of CD4 cells. AIDS 13:1827-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reed, J. C., J. M. Jurgensmeier, and S. Matsuyama. 1998. Bcl-2 family proteins and mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1366:127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadaie, M. R., and G. L. Hager. 1994. Induction of developmentally programmed cell death and activation of HIV by sodium butyrate. Virology 202:513-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saraste, A. 1999. Morphologic criteria and detection of apoptosis. Herz 24:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sastry, K. J., M. C. Marin, P. N. Nehete, K. McConnell, A. K. el-Naggar, and T. J. McDonnell. 1996. Expression of human immunodeficiency virus type I tat results in down-regulation of bcl-2 and induction of apoptosis in hematopoietic cells. Oncogene 13:487-493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siegel, R. M., D. A. Martin, L. Zheng, S. Y. Ng, J. Bertin, J. Cohen, and M. J. Lenardo. 1998. Death-effector filaments: novel cytoplasmic structures that recruit caspases and trigger apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 141:1243-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tait, J. F., and D. Gibson. 1992. Phospholipid binding of annexin V: effects of calcium and membrane phosphatidylserine content. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 298:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terai, C., R. S. Kornbluth, C. D. Pauza, D. D. Richman, and D. A. Carson. 1991. Apoptosis as a mechanism of cell death in cultured T lymphoblasts acutely infected with HIV-1. J. Clin. Investig. 87:1710-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trump, B. F., I. K. Berezesky, S. H. Chang, and P. C. Phelps. 1997. The pathways of cell death: oncosis, apoptosis, and necrosis. Toxicol. Pathol. 25:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsujimoto, Y., S. Shimizu, Y. Eguchi, W. Kamiike, and H. Matsuda. 1997. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL block apoptosis as well as necrosis: possible involvement of common mediators in apoptotic and necrotic signal transduction pathways. Leukemia 11(Suppl. 3):380-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vermes, I., C. Haanen, H. Steffens-Nakken, and C. Reutelingsperger. 1995. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods 184:39-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villa, P., S. H. Kaufmann, and W. C. Earnshaw. 1997. Caspases and caspase inhibitors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:388-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, J., and M. J. Lenardo. 2000. Roles of caspases in apoptosis, development, and cytokine maturation revealed by homozygous gene deficiencies. J. Cell Sci. 113:753-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei, X., S. K. Ghosh, M. E. Taylor, V. A. Johnson, E. A. Emini, P. Deutsch, J. D. Lifson, S. Bonhoeffer, M. A. Nowak, B. H. Hahn, et al. 1995. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature 373:117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westendorp, M. O., V. A. Shatrov, K. Schulze-Osthoff, R. Frank, M. Kraft, M. Los, P. H. Krammer, W. Droge, and V. Lehmann. 1995. HIV-1 Tat potentiates TNF-induced NF-κB activation and cytotoxicity by altering the cellular redox state. EMBO J. 14:546-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiley, S. R., K. Schooley, P. J. Smolak, W. S. Din, C. P. Huang, J. K. Nicholl, G. R. Sutherland, T. D. Smith, C. Rauch, C. A. Smith, et al. 1995. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity 3:673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wyllie, A. H. 1980. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature 284:555-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yagi, T., A. Sugimoto, M. Tanaka, S. Nagata, S. Yasuda, H. Yagita, T. Kuriyama, T. Takemori, and Y. Tsunetsugu-Yokota. 1998. Fas/FasL interaction is not involved in apoptosis of activated CD4+ T cells upon HIV-1 infection in vitro. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 18:307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang, C., Z. Ao, A. Seth, and S. F. Schlossman. 1996. A mitochondrial membrane protein defined by a novel monoclonal antibody is preferentially detected in apoptotic cells. J. Immunol. 157:3980-3987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]