Abstract

Serial passage of yellow fever 17D virus (YF5.2iv, derived from an infectious molecular clone) on mouse neuroblastoma (NB41A3) cells established a persistent noncytopathic infection associated with a variant virus. This virus (NB15a) was dramatically reduced in plaque formation and exhibited impaired replication kinetics on all cell lines examined compared to the parental virus. Nucleotide sequence analysis of NB15a revealed a substitution in domain III of the envelope (E) protein at residue 360, where an aspartic acid residue was replaced by glycine. Single mutations were also found within the NS2A and NS3 proteins. Engineering of YF5.2iv virus to contain the E360 substitution yielded a virus (G360 mutant) whose plaque size and growth efficiency in cell culture resembled those of NB15a. Compared with YF5.2iv, both NB15a and G360 were markedly restricted for spread through Vero cell monolayers and mildly restricted in C6/36 cells. On NB41A3 cells, spread of the viruses was similar, but all three were generally inefficient compared with spread in other cell lines. Compared to YF5.2iv virus, NB15a was uniformly impaired in its ability to penetrate different cell lines, but a difference in cell surface binding was detected only on NB41A3 cells, where NB15a appeared less efficient. Despite its small plaque size, impaired growth, and decreased penetration efficiency, NB15a did not differ from YF5.2iv in mouse neurovirulence testing, based on mortality rates and average survival times after intracerebral inoculation of young adult mice. The data indicate that persistence of yellow fever virus in NB41A3 cells is associated with a mutation in the receptor binding domain of the E protein that impairs the virus entry process in cell culture. However, the phenotypic changes which occur in the virus as a result of the persistent infection in vitro do not correlate with attenuation during pathogenesis in the mouse central nervous system.

Yellow fever virus (YFV) is the prototype member of the genus Flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae (48). Flaviviruses cause numerous globally important arthropod-transmitted infectious diseases such as hemorrhagic fever and acute encephalitis. Safe, highly effective vaccines remain to be established for some members of this family, particularly dengue and Japanese encephalitis viruses. With regard to live attenuated viral vaccines, a rational approach to their development requires knowledge of the molecular determinants of virulence and attenuation, and how they affect host range and tissue tropism. A detailed understanding of these factors will facilitate efforts to ensure the safety of such vaccines for human use.

Flaviviruses are small, enveloped viruses containing a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 11 kb. A single open reading frame encodes three structural proteins, C (capsid), prM (precursor to membrane protein), and E (envelope), and at least seven nonstructural proteins (NS1 to NS5) (48). Infection of host cells by these viruses proceeds by initial attachment to cellular receptors that remain unidentified, but in some cases appear to involve glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans (5, 18, 33). Entry into the cell is believed to occur by receptor-mediated endocytosis, in which conformational changes in the E protein, triggered within a low pH compartment, lead to fusion of viral and endosomal membranes and release of the RNA genome into the cytoplasm (17, 48). The E protein is also the principal antigen that elicits neutralizing antibodies, which confer protective immunity in rodent and primate models (15, 16, 23, 35).

Collectively, data from many studies have indicated that amino acid substitutions in the E protein can influence virulence properties (25, 31, 40, 41, 49, 50; reviewed in reference 38). The crystal structure of the soluble fragment of the tick-borne encephalitis virus E protein is widely regarded as a model common to all flaviviruses (46). This has led to the development of hypotheses concerning the possible functional effects of various virulence determinants. According to this model, domain III has been implicated in binding to cellular receptors (2, 7, 31, 46), and virulence determinants have been mapped to the lateral edge of this domain (46). These findings suggest that mutations which affect the binding properties of the virus towards cellular receptors can affect the virulence phenotype, presumably through effects on virus attachment and/or postreceptor events associated with virus entry.

Flaviviruses can cause persistent infection in various cell types, and this process is often associated with diminished virus production, defective interfering particles, and reduced cytopathic effects in such cultures (4, 24, 44, 51). However, the precise mechanisms involved in establishment of viral persistence in cell culture remain unknown and may vary from one model system to another. In this study, we characterized the properties of a YFV variant associated with persistent infection of a mouse neuroblastoma cell line. During passage of the virus in NB cells, a small-plaque virus emerged in conjunction with establishment of the persistent infection. This variant exhibited a lower efficiency of infection, impaired growth, reduced penetration, and poor spread in different cell lines compared to the parental virus. A nucleotide substitution in the E protein region of the variant, which predicts replacement of aspartic acid with glycine at position 360 in the putative receptor-binding domain (domain III) of the protein, appeared to be important for these properties, since a virus engineered to contain this substitution was defective in assays designed to evaluate steps in virus entry (attachment and penetration of host cells). Two additional substitutions were found in the NS2A and NS3 proteins.

Although we confined our analysis to the effects of the E protein substitution, one or both of these nonstructural region substitutions could also contribute to the properties of the NB15a variant. Our findings add to many previous studies which implicate domain III of the E protein in the process of virus attachment and entry into host cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Vero cells and SW13 cells (derived from human adrenal adenocarcinoma) were grown at 37°C in alpha-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL). NB41A3 (mouse neuroblastoma [NB]) cells (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC]) were grown in F10 medium supplemented with 15% horse serum and 2.5% certified FBS (Gibco-BRL) at 37°C.

Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells were maintained at 32°C in alpha-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. YF5.2iv virus was derived from an infectious clone of the YFV 17D virus (47). NB15a (the variant virus described in this study) was derived through passage of YF5.2iv in NB cells by splitting the infected cells at 10- to 14-day intervals. After appearance of small-plaque variants on Vero cells, the virus was plaque purified on Vero cells and amplified on NB cells. Titers of parental and variant viruses were determined by plaque assays on Vero cells at 37°C as described below.

Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis.

To prepare viral RNA, confluent monolayers of Vero cells were infected with NB15a at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.0. At 3 to 4 days postinfection, total RNA was extracted from infected cells using Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was resuspended in 10 mM Tris-chloride, pH 7.5, containing 0.1 mM EDTA, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C.

Primers were designed to regions of the YFV 17D virus genome for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). The 3′ primers were 5′-ATTTGTGTCCTTTGTAACCCTCAT-3′, 5′-GTGTATTCAAAGACTGCGTCCATG-3′, 5′-GCCAACACAAGAGTGCGCAAGCG-3′, 5′-AGGGTGAAGCACTAGATGG-3′, 5′-GCCACATATACCATATGGCACGGC-3′, and 5′-GTGGTTTTGTGTTTGTCATCCAAAGG-3′. The 5′ primers were 5′-AGTAAATCCTGTG TGCTAATTG-3′, 5′-GTGTGGAGAGAGATGCATC-3′, 5′-GAGAGAGCTCAAGTGCGGAGAT-3′, 5′-TTGTCGGGTATGGTGGC-3′, 5′-GTGCTTCACCCTGGAGTTGGCC-3′, and 5′-GCCGTGCCATATGGTATATGTGG-3′.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) and approximately 1.5 μg of total RNA at 46°C for 1 h, followed by incubation at 70°C for 10 min. Portions of the cDNA products were then subjected to PCR amplification using Deep Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), using the same 3′ primers and a corresponding set of 5′ primers to produce PCR products between 2.0 and 2.5 kb in length. Typical reactions were run at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 36 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and then 7 min at 72°C. PCR products were isolated from low-melting-temperature agarose gels (BioWhittaker) and purified using Wizard PCR Prep kits (Promega).

Purified PCR products were cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO using a Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen), and the ligation products were transformed into TOP10 Escherichia coli cells. Selected colonies were grown in small-scale cultures in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth plus ampicillin. DNA was purified from bacterial cells using a Wizard Preps DNA purification system (Promega). Plasmids were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion for presence of YFV 17D sequences. Two clones originating from two separate RT reactions were characterized for each cloned PCR product. Large-scale preparations of plasmid DNA were purified on cesium chloride gradients, and the resulting samples were sequenced using the Perkin Elmer/ABI cycle sequencing protocol and Big Dye Terminator reaction mixes and analyzed on an ABI Prism automated sequenator.

Construction of the G360 virus mutant.

A two-plasmid system for generation of infectious YFV 17D virus was used to reconstruct YFV virus harboring the NB15a E protein mutation (47). To construct pYFM5.2 containing the G360 mutation, a fragment spanning the region from nucleotide 1659 to nucleotide 2948 (YFV numbering) in the E protein was exchanged with the corresponding fragment of NB15a cDNA contained in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. These fragments were obtained by digestion with MluI and NsiI. The full-length YF5.2iv[G360] template was obtained by in vitro ligation of appropriate fragments of pYFM5.2[G360] with pYF5′3′IV, after digestion with AatII and NsiI and isolation of the DNA fragments from agarose gels and purification with Wizard DNA purification kits. The fragments were ligated using T4 DNA ligase (NEB). The assembled cDNA was used as a template for the synthesis of infectious RNA transcripts using SP6 RNA polymerase (NEB) in the presence of 5′ cap analog as described previously (47).

Approximately 350 ng of RNA was transfected into Vero cells in the presence of 20 μg of Lipofectin (Gibco-BRL), followed by incubation at 37°C in alpha- minimal essential medium plus 5% FBS. Virus was harvested from the cell culture at time of onset of cytopathic effect, and the yield was titrated by plaque assay on Vero cells. Stock virus of the mutant G360 was prepared by three rounds of plaque purification on Vero cells and amplification in NB cell cultures.

Growth curves and plaque assay.

Monolayers of SW13 or C6/36 cells in triplicate wells were infected with YF5.2iv, NB15a, or G360 viruses at a multiplicity of infection of 0.3 PFU per cell at 37°C (SW13 cells) or 32°C (C6/36 cells) for 1 h. The growth curves of the NB15a and G360 viruses compared to YF5.2iv in NB cells were performed at MOI of 0.3 and 0.2 PFU/cell, respectively, in NB cell medium as described above. SW13 and C6/36 cells were maintained in alpha-minimal essential medium plus 3% FBS, and NB cells were maintained in Ham's F10 medium plus 15% horse serum and 2.5% certified FBS. Media were harvested and replaced at 24-h intervals.

Virus titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells. Viruses were serially diluted in alpha-minimal essential medium containing 10% FBS and used to infect confluent Vero cell monolayers. After infection for 1 h, virus was removed and the monolayers were overlaid with 1% (wt/vol) SeaKem ME agarose (BioWhittaker) in alpha-minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% FBS without penicillin-streptomycin. Plaques were visualized after 5 days of incubation at 37°C for YF5.2iv or 7 or 8 days for NB15a by staining with 1.5% crystal violet in 20% ethanol, after fixation in 7% formalin.

Infectious center assay.

NB, C6/36, and SW13 cells in six-well plates were infected with virus at an MOI of 0.4 PFU/cell at 37 or 32°C (C6/36 cells). Virus was then removed, and the medium was replaced. After incubation for 4 h at 37°C (NB and SW13) or 32°C (C6/36), the monolayers were trypsinized to disperse cells and inactivate any noninternalized virus, washed five times with alpha-minimal essential medium containing 10% FBS by low-speed centrifugation at 4°C, and resuspended in alpha-minimal essential medium plus 10% FBS. An aliquot of the cell suspension was counted using trypan blue to quantitate viable cells. Cell suspensions were then serially diluted (10-fold) and plated on confluent monolayers of Vero cells at 37°C. First and second washes of the cell suspension (alpha-minimal essential medium plus 10% FBS) were also diluted and plated onto Vero monolayers to verify that no residual unbound virus was detectable in the cell suspensions. After 1 h of incubation, the Vero monolayers were overlaid with 1% agarose in alpha-minimal essential medium plus 10% FBS and incubated at 37°C (NB and SW13) for 5 days (YF5.2iv) or 7 days (NB15a) or at 32°C (C6/36) for 24 h and then at 37°C for 4 days (YF5.2iv) or 6 days (NB15a). Infectious centers were counted after staining of plaques with crystal violet, and the efficiency of infection of the original cell substrates was determined as the ratio of the number of plaques to the number of PFU used in the initial input virus, which were titrated in parallel on Vero cells.

Fluorescent focus assay.

Confluent monolayers of Vero cells were infected with viruses for 1 h at 37°C at an MOI of 10 to 20 PFU per well. Virus was removed and monolayers were overlaid with 1% agarose (BMA) in alpha-minimal essential medium plus 3% FBS or with alpha-minimal essential medium plus 3% FBS and incubated at 37°C. At intervals of 24 h, liquid cultures were processed for measurement of virus yields as described above, and cultures under agarose were processed for immunofluorescence. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (90 min at room temperature), followed by removal of the agarose and permeabilization with 100% methanol (6 min at −20°C). Fixed cells were incubated with primary antiserum (anti-YFV hyperimmune ascitic fluid [ATCC] diluted 1:500) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 1% FBS for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times with PBS, and then incubated with secondary antibody (affinity-purified fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G [IgG] antibody, 1:50) (ICN) in PBS plus 1% FBS for 30 min at 37°C.

Cells were examined using a Nikon TE-300 fluorescence microscope equipped with a standard fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) fluorescence cube and a SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Digitized images of the fluorescent foci were used to determine their size by taking at least three area measurements per fluorescent focus using an image analysis tool standardized with a micrometer. Ten to 20 fluorescent foci per sample were analyzed to determine the average focus size. Fluorescent focus assays on C6/36 and NB cells were performed in an essentially similar manner as for Vero cells.

Adsorption and penetration assays.

The kinetics of adsorption were determined by an adsorption assay as previously described (22) with slight modifications. Monolayers of Vero cells in 60-mm tissue culture plates were infected with viruses in duplicate at an MOI of 50 PFU per plate for 5, 10, 20, 30, or 60 min at 37°C. Residual virus then was removed; the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and overlaid with agarose as for the standard plaque assay. Plaques were visualized after 5 to 8 days of incubation as described above. The number of plaques on cells incubated with virus for 60 min was considered 100%, and the adsorption at each time point was expressed as a percentage of the adsorbed virus for 60 min.

Penetration rate was determined by a previously described method (20). Cell monolayers were inoculated at 37°C using an input quantity of approximately 100 PFU of virus per plate. At various intervals up to 60 min, unbound virus was removed, and duplicate samples were treated with a solution of acid glycine (pH 3.0) (0.1 M glycine and 0.1 M sodium chloride) for 2 min to inactivate uninternalized virus. Following one wash with PBS plus 3% FBS, the cells were overlaid with agarose and incubated at 37°C to allow plaque formation. A third replicate sample for each time point (non-acid-treated control) received two washes with PBS before being overlaid with agarose. Percentage of penetrated virus for each time point was calculated as the ratio of the number of plaques on the acid-treated cells to the number of plaques on the non-acid-treated cells for each time point × 100.

On NB cells, infectious foci were determined by immunostaining of the cells as described above, after 4 days of incubation, and counting of the foci with a fluorescence microscope. In all of these experiments, the vast majority of input virus was found to be cell associated by 5 to 10 min, based on plaques or infectious foci produced in the non-acid-treated control samples. Of this fraction, between 92 and 97% were sensitive to acid inactivation.

In vitro cell binding assays.

Confluent monolayers of C6/36, Vero, or NB cells chilled to 4°C for 1 h were incubated with virus at 4°C at multiplicities of infection of 0.5 to 1.0 PFU/cell for intervals of time ranging from 15 min to 120 min. At each time point, residual virus was removed, monolayers were washed two times with PBS plus 5% BSA, and the washes were pooled with the residual virus. The cell monolayers and residual virus were either used for titration immediately or frozen at −70°C for subsequent analysis. Cells were resuspended in PBS plus 5% bovine serum albumin and sheared through a 30-gauge needle three times, and the suspension was used for plaque titration on Vero cells. The amount of cell-associated infectious virus was determined by the number of plaques. Residual virus in the washes was also measured by plaque assay on Vero cells.

Mouse neurovirulence testing.

Virulence of the NB15a and YF5.2iv viruses for mice was determined by intracerebral inoculation of young adult mice (5-week-old ICR mice; Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, Ind.). Viruses were diluted in alpha-minimal essential medium plus 10% FBS and injected in 40-μl volumes after anesthetization of the mice. Mice were observed daily for signs of illness and were euthanized when found in a moribund condition. Differences in average survival times were evaluated for statistical significance using Wilcoxon rank order testing. Brains of some moribund mice which received either YF5.2iv or NB15a were recovered by dissection for analysis of the virus titer and plaque morphology. Brains were homogenized as 20% (wt/vol) suspensions in PBS plus 10% FBS, and virus content and plaque size were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells.

RESULTS

Derivation of the NB15a variant.

In initial experiments with NB cells infected with YF5.2iv virus, no obvious cytopathic effects were observed over a period of several days after infection. During this interval, the cells exhibited a morphology consisting of subconfluent monolayers of cells of heterogeneous size, with primitive arborized cell processes indicative of a neuronal phenotype. Virus production reached a peak titer of approximately 6.7 log PFU/ml. The cells were then passaged, and persistence of virus infection was determined by plaque assay of the medium at the time of passage. Following eight passages, small-plaque variants began to emerge and became predominant after 10 passages. By passage 15, large plaques were completely undetectable. The NB cell-adapted virus (NB15a) was then plaque purified and amplified on NB cells, and this stock virus preparation was used for all subsequent experiments.

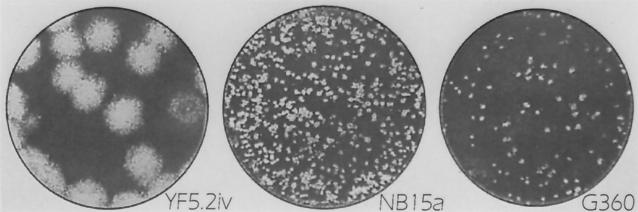

The plaque size of NB15a on Vero cells was considerably smaller than that of the parental virus (Fig. 1). At 8 days postinfection, NB15a formed minute plaques which were approximately 10% the size of those produced by YF5.2iv virus. Moreover, the NB15a plaques did not visibly enlarge beyond 7 days of plaque formation on Vero cells, while the plaque size of the parental YF5.2iv virus became progressively larger. Similar results were obtained on SW-13 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Plaque morphology of parental YF5.2iv virus, the NB15a variant, and the engineered G360 mutant on Vero cells. Plaque assay was done as described in the text. Plaques were visualized by crystal violet staining on day 8 for all viruses. Stained monolayers were magnified by low-power microscopy and photographed with an electronic imaging device.

Nucleotide sequence of NB15a and construction of G360 virus mutant.

To identify the nucleotide sequence differences which accounted for the reduction in plaque formation and growth efficiency (see below) of the NB15a virus, the complete nucleotide sequence of this virus was determined. A total of three nucleotide substitutions were identified in the genome of this virus relative to that of the parental YF5.2iv virus (47). All three substitutions cause predicted amino acid substitutions, which include residue 360 of the envelope (E) protein (aspartic acid to glycine), residue 173 of the NS2A protein (valine to leucine), and residue 582 of the NS3 protein (threonine to isoleucine).

To determine if the substitution mutation in the envelope protein was involved in the small-plaque phenotype of NB15a, the YF5.2iv infectious clone virus was engineered to encode a glycine residue at position 360 of the E protein. The resulting virus (G360) exhibited a small-plaque phenotype on Vero cells, essentially identical to that of the original NB15a variant (Fig. 1). This indicates that the glycine mutation is an important determinant of the plaque properties of the NB15a variant.

Growth kinetics in cell culture.

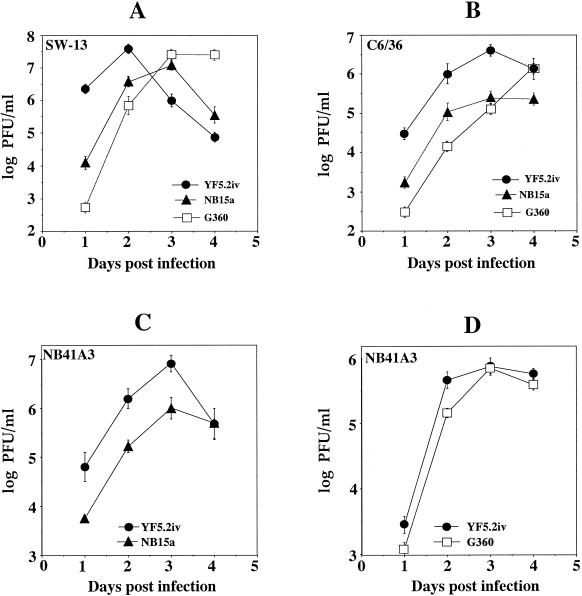

To determine if there were differences in the growth properties of the parental YF5.2iv virus, the NB15a variant, and the G360 mutant, virus production was compared in various cell lines after low-multiplicity infection (Fig. 2). Cells of different host origins (human, mosquito, and mouse) were used in these experiments to see if the NB15a or G360 virus would exhibit a host-restricted growth phenotype. In SW-13 cells (Fig. 2A), YF5.2iv reached maximal virus production (4.2 × 107 PFU/ml) at 2 days, followed by rapid reduction in yield. In contrast, NB15a initially gave a lower virus yield, which increased to a peak titer of 1.3 × 107 PFU/ml at 3 days before diminishing. Growth of the G360 virus was initially less efficient than that of the NB15a virus, but reached a similar peak virus yield of 2.8 × 107 PFU/ml at 3 days postinfection.

FIG. 2.

Growth curve analyses of parental and variant viruses. Monolayers were infected and virus yields were determined as described in the text. (A and B) YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses in SW13 and C6/36 cells, respectively. (C and D) Growth of parental YF5.2iv and the NB15a and G360 variant viruses in NB cells, respectively.

In C6/36 cells (Fig. 2B), growth of the NB15a and G360 viruses was impaired relative to YF5.2iv, but G360 was less efficient than NB15a over the initial 2 days. Peak virus titers of NB15a, but not G360, were lower than that achieved by YF5.2iv. In NB cells, NB15a exhibited less efficient replication than the YF5.2iv parent (Fig. 2C). Both viruses reached the peak of virus production at 3 days postinfection. However, the maximal yield of NB15a was approximately 1 log lower than that of the YF5.2iv virus (1 × 106 versus 8.4 × 106 PFU/ml, respectively).

The G360 virus exhibited mild impairment in growth efficiency compared to YF5.2iv (Fig. 2D). This impairment was on the order of 0.5 log PFU/ml at 1 and 2 days postinfection, followed by an increase to a similar peak titer as seen with YF5.2iv by 3 days. Thus, NB15a exhibited a delay in virus production in all cell lines tested compared to YF5.2iv and also a lower peak titer in all cell lines. The G360 virus was more impaired than NB15a in non-NB cell lines during the early period of infection, but appeared less impaired than NB15a in the NB cell line. The rise in titers of the variant viruses, in some cases to levels similar to those of YF5.2iv after several days of culture, suggests that revertants may have been generated. However, parental-size plaques were observed only rarely in the NB15a and G360 virus samples titrated in these experiments. Since growth studies in C6/36 cells were done at 32°C, we also cannot exclude that additional differences in growth properties may exist among the viruses at temperatures which are customary for this cell line (28 to 30°C).

Infectious center assay.

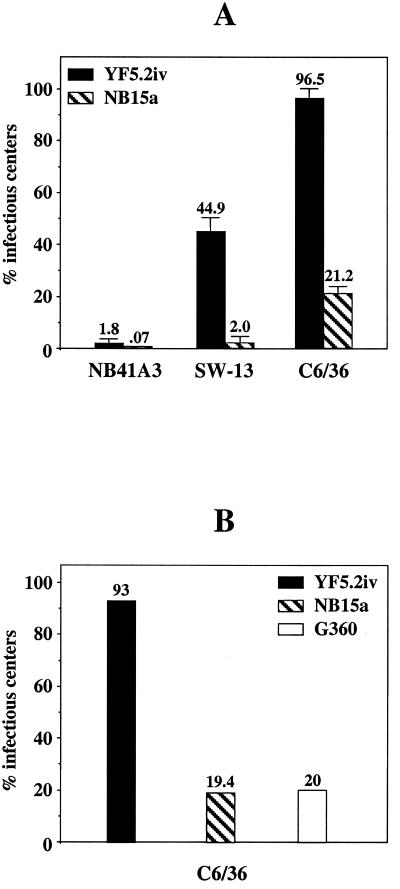

As an initial approach to determining the functional basis for the defect in plaque formation and growth exhibited by the NB15a virus, an infectious-center assay was used to compare its efficiency of infection to that of YF5.2iv on various cell lines (NB, SW13, and C6/36 cells). In these experiments, a standardized amount of virus (based on titration in Vero cells) was allowed to infect the test cell line, and then the cells were harvested and plated on Vero cell monolayers for quantitation of infectious foci by plaque formation. Essentially, this assay compares infectivity for Vero cells after a single round of infection on the other cell types. In different experiments at a low MOI, NB15a exhibited an efficiency of infection which varied from fivefold less (on C6/36 cells), to 22-fold less (on SW13 cells), to 25-fold less (on NB cells) than that of the YF5.2iv parent (Fig. 3A). On NB cells, the efficiency of infection of the YF5.2iv virus was particularly low (1.8%) compared to what was seen on the other cell lines, and the NB15a virus exhibited very little infectivity (0.07%).

FIG. 3.

Infectious center assays of parental YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 mutant viruses. Cells were infected as described in the text and titrated as single-cell suspensions on Vero cells. (A) Results for YF5.2iv and NB15a viruses on NB, SW-13, and C6/36 cells. Values indicate means ± standard deviations (SD) for triplicate samples. (B) An identical experiment on C6/36 cells, in which the G360 mutant was included. Efficiency of infectious center formation is based on ratio of infectious centers to input PFU as determined by parallel titration of the input virus on Vero cells.

In a separate experiment to evaluate the effect of the G360 mutation on infectivity, the YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses were compared on C6/36 cells. In this case, infectivity of the G360 virus was found to resemble that of the NB15a virus. The percentage of infectious centers produced by G360 was 20, compared to 19.4 for the NB15a virus (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that the small plaque size and reduced growth efficiency of NB15a might involve an impairment in an early step in the replication cycle, conceivably at the level of virus binding, penetration, or virion disassembly. However, the decreased infectivity could also reflect defects at later stages of infection, such as RNA replication or events involved in virus assembly.

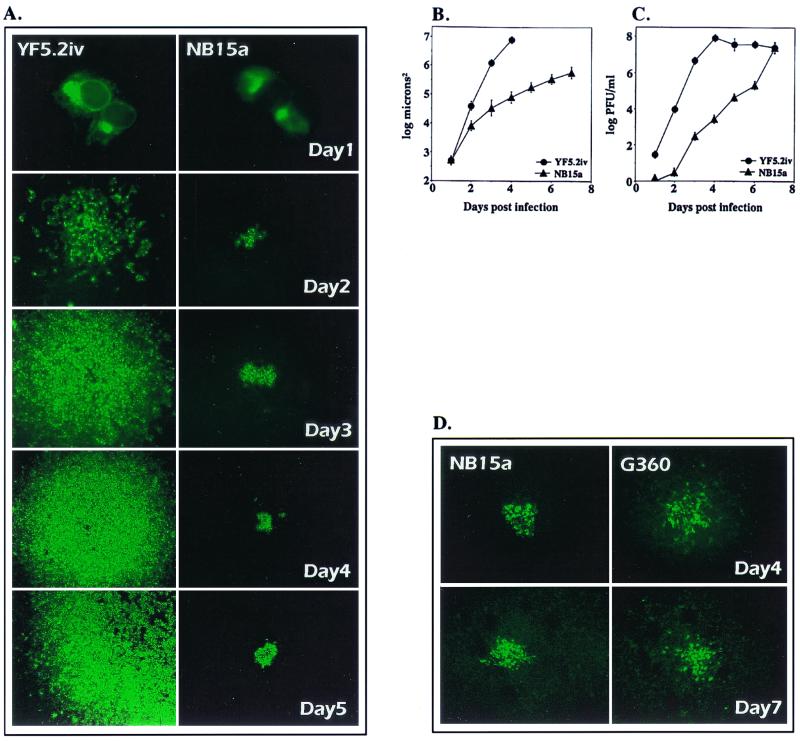

Fluorescent focus assay.

If the NB15a virus is impaired in the process of cell entry relative to the YF5.2iv virus, this might result in a defect in its ability to spread from cell to cell. To address this question, we examined virus spread in cell culture monolayers using a fluorescent focus assay. This assay was considerably more sensitive than plaque assay for examining virus spread and enabled detection of infected cells within 24 h of infection using a very low multiplicity (Fig. 4A). This high sensitivity was therefore expected to permit discrimination of whether the YF5.2iv and NB15a viruses differed only in plaque size or in the overall size of the infectious focus. If the fluorescent focus size of NB15a was as large as that of YF5.2iv, this would suggest that NB15a formed small plaques because of reduced cytopathic effects but was not necessarily defective in spread.

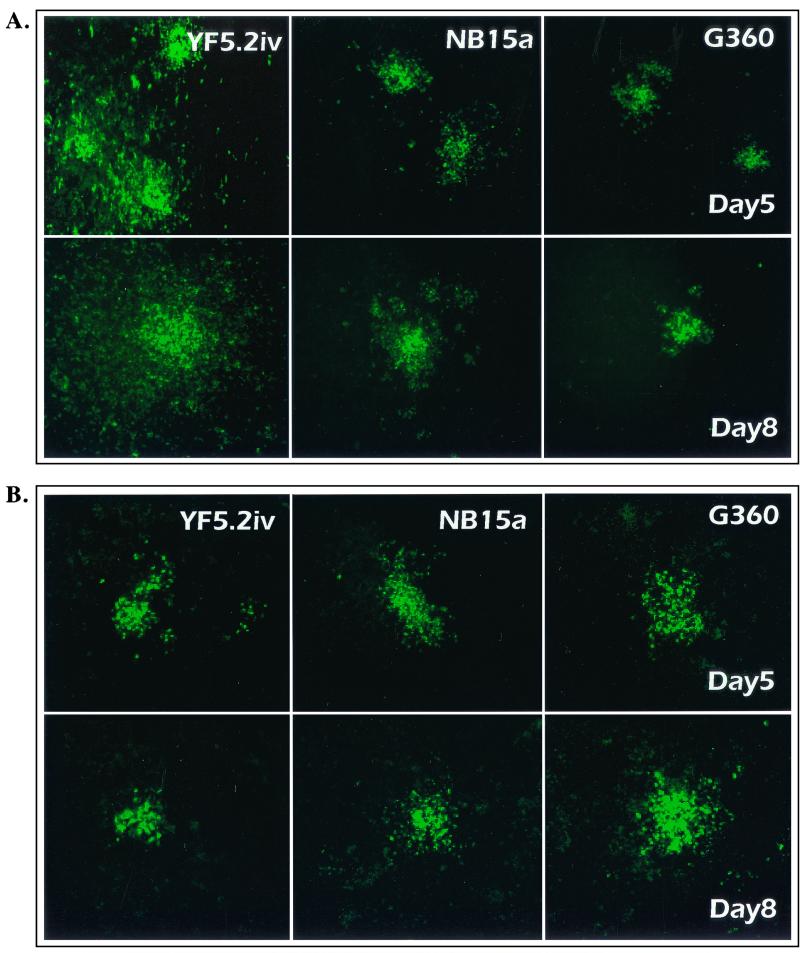

FIG. 4.

Fluorescent focus formation assay. (A) Vero cells were infected with YF5.2iv or NB15a virus at low MOI, and serial samples were processed for indirect fluorescence at 24-h intervals between days 1 and 5, as described in the text. Images are representative of approximately 10 foci examined for each time point for each virus. Images were taken at ×400 (day 1), ×200 (day 2), ×100 (day 3), and ×40 (days 4 and 5). (B) Quantitative determination of relative focus sizes of YF5.2iv and NB15a viruses as shown in panel A. Foci were measured as described in the text. Each value represents mean focus size ± SD. (C) Growth curve of parallel cultures of viruses YF5.2iv and NB15a on Vero cells infected at the multiplicity used for the fluorescent focus assay. Virus yields were measured by titration on Vero cells. (D) Vero cells were infected with the G360 mutant or NB15a, and foci were analyzed as described for panel A. Images were taken at ×100 at days 4 and 7.

In Vero cells, fluorescent foci of both the NB15a virus and the YF5.2iv virus under agarose consisted of one or two cells at 24 h (Fig. 4A). Foci produced by the YF5.2iv virus enlarged between days 2 and 4 and reached confluence beyond 6 to 7 days. In contrast, the NB15a virus generated foci which involved only a small number of cells on the second and subsequent days after infection, and these foci did not reach confluence. The sizes of foci formed by NB15a were 21.4, 2.7, and 1.2% of those produced by YF5.2iv at 2, 3, and 4 days postinfection, respectively (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the small plaque size of NB15a on Vero cells is caused by reduced virus spread, rather than simply diminished cytopathic effects. It is also possible, however, that sensitivity of the NB15a virus to impurities in the agarose may contribute to the small plaque size.

To verify that reduced virus yields were generated during infections done at the multiplicity used for the fluorescent focus experiment, parallel cultures of viruses grown in liquid medium were sampled for virus yields over the same intervals. Figure 4C demonstrates that the NB15a virus required longer to reach the peak titer achieved by YF5.2iv (7 versus 4 days, respectively), indicating that the reduced spread of the variant correlated with diminished virus production in these cultures over the interval from 0 to 6 days. We observed that the reduction in spread of the NB15a virus was less dramatic in liquid cultures than in cultures under agarose (data not shown), which could in part account for the similar peak titers eventually reached by the two viruses in Fig. 4C. As with the experiments in Fig. 2, we cannot exclude the emergence of revertants, but the plaque sizes of the titrated samples were consistent with retention of the NB15a phenotype.

To determine if the substitution of glycine at position 360 of the E protein was involved in the defective virus spread, the G360 mutant was tested for fluorescent focus formation. Similar to the result seen with NB15a, this virus was markedly restricted in its ability to spread on Vero cells (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that the ability of the NB15a virus to spread through Vero cell monolayers was dramatically impaired relative to that of the YF5.2iv virus, and substitution of glycine for aspartic acid at residue 360 of the E protein was sufficient to confer this property.

In further experiments, we addressed whether the limitation of spread of the NB15a variant was a host-restricted property. Figure 5A compares the spread of the YF5.2, NB15a, and G360 viruses in C6/36 cells. The parental YF5.2iv virus produced well-formed foci by 5 days, and these continued to enlarge by 8 days postinfection, but in contrast to results in Vero cells, the expansion involved subconfluent spread surrounding a dense focus of fluorescence. NB15a formed smaller, discrete foci, which did not exhibit areas of surrounding spread seen with the YF5.2iv virus at 8 days. The G360 mutant resembled NB15a in its capacity to spread in C6/36 cells.

FIG. 5.

Immunofluorescent focus formation of YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses. Experiments were conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 4. (A) C6/36 cells at days 5 and 8 postinfection. (B) NB cells at days 5 and 8 postinfection. Magnification, ×100.

Figure 5B compares the spread of the three viruses in NB cells. The YF5.2iv virus exhibited poor spread relative to what was observed in Vero cells, with the fluorescent foci not enlarging much between 5 and 8 days postinfection. In contrast to its reduced spread in Vero and C6/36 cells, however, the NB15a virus did not appear to differ dramatically from YF5.2iv virus in spread through NB cell monolayers. The G360 mutant was similar to NB15a in its spread through NB cells. To ensure that the results in this cell line were not merely due to sampling errors, multiple individual foci were examined for the YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses. In at least 10 different foci tested, spread of YF5.2iv and NB15a was generally similar, although some foci appeared somewhat larger or smaller than the representative ones depicted in Fig. 5B. However, the density of staining in the center of the foci usually appeared greater for YF5.2iv than for NB15a.

Taken together, these various experiments indicate that the efficiency of spread of the YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses differed depending on the cell line tested. YF5.2iv spread efficiently on Vero cells, less efficiently on C6/36 cells, and poorly on NB cells. The NB15a and G360 viruses spread very poorly on Vero cells and poorly on C6/36 cells. These viruses did not differ markedly from YF5.2iv in spread through NB cells, at least over the 8-day interval examined in these experiments.

Adsorption and penetration assays.

The results of the fluorescent focus experiments suggested that the NB15a virus might be defective in the process of cell entry. To address this possibility, the three viruses were compared for the properties of adsorption and penetration of cultured cells. Initially, the rates of plaque formation on Vero cells over time intervals varying from 0 to 60 min postinoculation of virus were compared. In simple adsorption experiments at 37°C, using approximately 100 PFU per 3 × 106 cells, large percentages of the input viruses (between 50 and 100%) were found to form plaques after an adsorption time of as little as 5 min (data not shown). Although there was no major time dependence of adsorption under these conditions, greater amounts of the YF5.2iv virus than of NB15a were consistently adsorbed at each interval tested from 0 to 60 min. We interpreted this to indicate that with the very low multiplicities used for these experiments, initial binding interactions of the two viruses with the cells occurred quite rapidly.

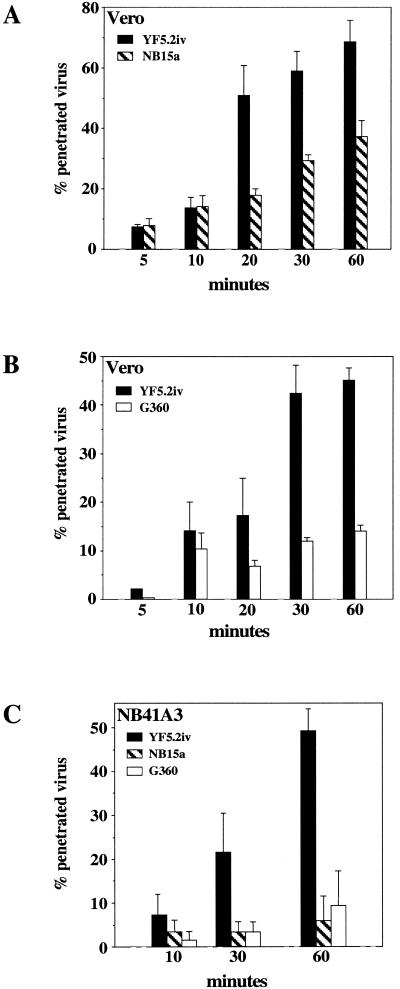

In subsequent experiments, this assay was modified to compare penetration of cells by the two viruses. This was done by including an acid pH treatment at each time point to discriminate virus which had undergone internalization from the background of bound but noninternalized virus. Results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 6. The values for penetrated virus at each time point are indicated as a percentage of a non-acid-treated control for the same time point in order to account for any differences in efficiency of binding between the two viruses over the 1-h interval of the experiment. The percentage of YF5.2iv virus which penetrated Vero cells was in the range of 5 to 10% over the initial 10 min of infection, rose to 50% by 20 min, and reached levels as high as 70% by 60 min (Fig. 6A). The NB15a virus exhibited an initial level of penetration that was similar to that of YF5.2iv, but did not rise greatly at 20 min and reached a level at 60 min that was only about 35% of input virus. Differences between the percentage of YF5.2iv and NB15a which had penetrated were significant at 20, 30, and 60 min (P < 0.005, 0.02, and 0.01, respectively).

FIG. 6.

Virus penetration assay. The percentage of plaques formed by the YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses which were resistant to low-pH treatment as a function of time on Vero cells (A and B) and NB41A3 cells (C). Experimental procedures were as described in the text. Standard plaque assay was used for experiments on Vero cells. On NB cells, infectious foci were quantitated by indirect immunofluorescence. All values are means ± SEM.

Similar experiments were conducted to compare penetration of the G360 virus with that of YF5.2iv in Vero cells (Fig. 6B). YF5.2iv again showed a rise in penetration by 20 min and reached levels approaching 50% by 60 min, but penetration by the G360 virus was in the range of only 10 to 15% between 10 and 60 min postinfection. Some variation in the extent of penetration of the parental YF5.2iv virus at a given time point was observed in different experiments (Fig. 6A and B); however, the same time-dependent pattern was observed, with significant rise in penetration of YF5.2iv virus occurring after 20 to 30 min. Differences in the condition of the monolayers among separate experiments may affect the kinetics of virus penetration versus inactivation at individual time points.

Experiments were also done to compare the penetration of NB cells by the three viruses (Fig. 6C). YF5.2iv virus reached levels of penetration of 7, 20, and 50% at 10, 30, and 60 min, respectively. In contrast, levels for the NB15a and G360 viruses were greatly diminished at all time points and reached only approximately 10% by 60 min. These results suggest that the NB15a virus is defective in virus entry, involving one or more steps which are required for penetration of the host cell membrane. Furthermore, results with the G360 mutant indicate that the defect in penetration is dependent upon the glycine substitution at position 360 of the E protein. These data are consistent with the lower infectivity of NB15a virus seen in the infectious center assay (Fig. 3) and suggest that a defect in the penetration phase is partly responsible for its impaired replication efficiency.

Cell surface binding experiments.

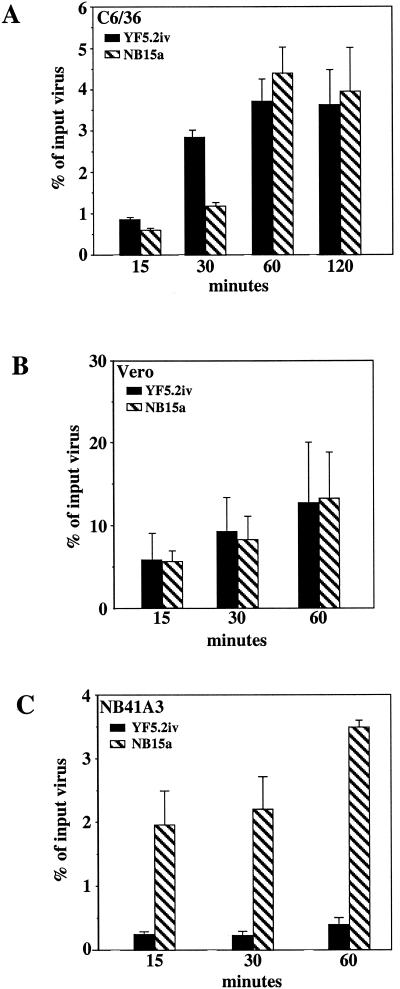

To further investigate the differences seen in studies of absorption of YF5.2 and NB15a viruses to cultured cells mentioned above, binding of these viruses to Vero, C6/36, and NB cells was compared. In these experiments, viruses were bound to cell monolayers chilled to 4°C, and the percentage of input virus which was detectable in the cell-associated fraction at intervals from 0 to 60 min was measured by plaque assay of cell homogenates. The higher multiplicity used in these experiments (0.5 to 1.0 PFU per cell) and the use of low temperature to block endocytosis resulted in more discernible time-dependent differences in association of virus with cells than were observed in preliminary adsorption experiments done at 37°C.

Figure 7 shows the results of the experiments. On C6/36 cells (Fig. 7A), NB15a exhibited a lower amount of cell-associated virus than YF5.2iv at 15 and 30 min of adsorption. At 60 and 120 min, NB15a exhibited slightly higher levels of binding. On Vero cells (Fig. 7B), the NB15a virus did not differ from YF5.2iv in the level of cell-associated virus at any time point. On NB cells (Fig. 7C), the NB15a virus exhibited a greater amount of infectious cell-associated virus than YF5.2iv at all time points examined, although the levels did not appear to increase much as a function of time.

FIG. 7.

Binding of parental YF5.2iv and NB15a viruses to cultured cells. Experimental details were as described in the text. Percent input virus (y axis) indicates the percent total virus added to the cells, which was detected as infectious virus in the cell-associated fraction by plaque assay at each time point. (A) Vero cells; (B) C6/36 cells; (C) NB cells. Values represent means ± SEM.

In all of these experiments, only small percentages of the input viruses were detected in the cell-associated fractions. This could reflect loss of infectivity (as assessed by plaque assay) of bound virus as a result of conformational changes induced by interaction with cellular receptors or, alternatively, during preparation of the cell extracts. To further analyze this, and to assess whether differences in the stability of the viruses might account for the lower levels of YF5.2iv virus than NB15a in the cell-associated fraction of NB cells, residual unbound virus in the medium was also measured for each time point. For YF5.2iv virus in Vero cells, at 15, 30, and 60 min, these values were 34% ± 16%, 31% ± 13.4%, and 50.4% ± 25% of input virus, respectively (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). For NB15a on Vero cells, the values were 38.6% ± 10.4%, 51.6% ± 7.6%, and 53.6% ± 26.4% of input virus, respectively. On NB cells, the values for YF5.2iv at 15, 30, and 60 min were 20.7% ± 0.5%, 25.5% ± 9.2%, and 31.3% ± 1% of input virus, respectively, whereas for NB15a, the values were 62.6% ± 1.3%, 54.8% ± 10.2%, and 71.7% ± 9.5% of input virus, respectively.

Thus, the relatively similar quantities of viruses in the medium in Vero cells suggest no substantial difference in virus stability in the medium. In the case of NB cells, less NB15a virus was depleted from the medium than YF5.2iv (approximately two- to threefold), and more was detectable in the cell-associated fraction. These results suggest that in contrast to the other cell lines, a difference exists between the two viruses in their initial interactions with the NB cell surface. One possibility is that YF5.2iv is more rapidly and efficiently bound than NB15a, but once bound is more readily rendered into a noninfectious state, based on detection by plaque assay. This interpretation is speculative, and further experimentation is required to substantiate this hypothesis.

Mouse neurovirulence testing.

The impairment exhibited by the NB15a virus in penetration, infectivity, and growth properties in cultured cells suggested that it might have an attenuated neurovirulence phenotype in mice. To determine if this was the case, young adult mice (ICR males, 5 weeks of age) were subjected to intracerebral inoculation with either a low or a high dose of the NB15a or YF5.2iv virus and monitored for illness and mortality (Table 1). At the low dose, YF5.2iv virus caused 100% mortality, with an average survival time of 11.6 days (range, 10 to 20 days). The NB15a virus also caused 100% mortality at the low dose, with an average survival time of 11.8 days (range, 11 to 20 days). At the high dose, mortality from the YF5.2iv virus was 100%, with an average survival time of 8.5 days (range, 8 to 9 days). Mortality from the NB15a virus at the high dose was 92%, with an average survival time of 9.6 days (range, 8 to 11 days). The differences in mortality rates and average survival times were not significant at either dose between the two viruses.

TABLE 1.

Intracerebral inoculation of ICR mice

| Virus | Dose (log10 PFU) | Mortality (no. dead/total) | % Dead | Avg survival time (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YF5.2iv | 1.5 | 10/10 | 100 | 11.6 |

| NB15a | 1.6 | 11/11 | 100 | 11.8 |

| YF5.2iv | 3.5 | 12/12 | 100 | 8.5 |

| NB15a | 4.2 | 11/12 | 92 | 9.6 |

To determine if the fatal infections caused by the NB15a virus involved any reversion to the parental YF5.2iv virus during replication in mouse brain, virus was recovered from the brains of some moribund mice and analyzed by plaque assay on Vero cells. In four such mice analyzed from each of the high- and low-dose groups, the plaque size of the brain-associated virus was the same as that of the original NB15a variant. Thus, selection of a revertant was not the basis for the lethality of NB15a in these mice. The virus burdens in the brains of mice succumbing to NB15a were similar to those of mice succumbing to YF5.2iv (4.4 × 107 PFU/g versus 7.0 × 106 PFU/g of brain tissue, respectively [mean for four mice tested in the high-dose group for each virus]). Thus, no dramatic difference in the neurovirulence of NB15a and YF5.2iv was observed at the doses tested, based on mortality rates, average survival times, and accumulation of virus burdens in the central nervous system.

DISCUSSION

A variety of experimental systems have been developed for investigating the viral molecular determinants which influence the interactions of flaviviruses with cultured cells. As a result, it has been demonstrated that mutations in the E protein can limit entry of virus into host cells presumably through their effects on attachment, penetration, or fusion (9, 13, 14, 25, 29, 32, 36, 37). However, there are still relatively few experimental data directly implicating specific structural elements of the E protein in these functions (reviewed in reference 17). In the present study, we characterized the properties of a YFV variant which had been selected during persistent infection of a mouse neuroblastoma cell line. Compared to its parental YF5.2iv virus, this variant (NB15a) formed very small plaques on Vero and SW13 cells, and its replication efficiency was impaired to some extent in cell lines of different host origins. NB15a was also defective in its ability to spread through cell monolayers. This defect was most evident on Vero cells and least evident on NB cells.

The molecular basis for the cell culture properties of the NB15a variant involved an amino acid substitution of glycine for aspartic acid at position 360 in the putative receptor-binding domain of the E protein. This conclusion is based on the fact that the YF5.2iv virus engineered to contain this substitution (the G360 mutant) resembled NB15a in its plaque-forming efficiency, growth kinetics, and spread through cell monolayers. Functionally, these properties were related to differences in attachment and penetration of the viruses conferred by the presence of the G360 mutation. Further investigation is needed to determine if the substitutions in the NS2A and NS3 regions also contribute to reduced replication efficiency of the NB15a virus.

The small plaque sizes of the NB15a and G360 viruses resulted from a defect in their ability to spread from cell to cell, rather than merely a diminished cytopathic effect, since fluorescence focus assays in Vero cells revealed that the overall sizes of their infectious foci were very restricted compared to those of the YF5.2iv virus. This defect in spread may contribute to the lower virus yields of NB15a observed early after low-multiplicity infection in Vero cells (Fig. 4C). The NB15a and G360 viruses also showed diminished spread in C6/36 cells, although the differences from YF5.2iv were not as striking as in Vero cells. The impairment in spread in C6/36 cells also correlated with reduced growth of the variants in such cells, at least during the first 3 days of infection. In contrast to these results, the focus sizes of the YF5.2iv, NB15a, and G360 viruses in NB cells were generally similar. However, the fact that the parental YF5.2iv virus spread poorly in this cell line made it very difficult to detect any decrease in the ability of the NB15a virus to spread. Despite this limitation, a defect in penetration of NB15a into NB cells was readily demonstrated, and this may be an important factor in its restricted growth after low-multiplicity infection in these cells.

One might expect that the defects in penetration and spread of the NB15a and G360 viruses would cause greater reductions in virus yields than seen in the growth curve experiments. These defects may be less significant at multiplicities which occur during multiple rounds of infection in growth curve experiments. Thus, simple correlations between these defects and growth kinetics cannot easily be made. In any case, it is clear that the G360 mutation does cause a measurable impairment of replication efficiency of YFV in cell culture. The data also indicate host-restricted effects of the G360 mutation on virus spread through cultured cells. Persistent infections are known to involve viruses which exhibit host range effects on cell culture properties (44, 45). In the case of the NB15a variant, this differential effect further complicates attempts to make such correlations.

The decreased ability of the NB15a and G360 viruses to penetrate cultured cells compared to YF5.2iv suggests that the mutation in the E protein impairs interactions between the virus and host cell surface molecules required for virus entry. Because the defect was observed in both Vero and NB cell lines, it seems likely that some specific functional property of the E protein beyond the level of initial attachment is affected by the mutation. In contrast, in adsorption experiments, a difference in the properties of the NB15a and YF5.2iv viruses was observed only on NB cells. As mentioned previously, this may involve a lower initial affinity of NB15a than YF5.2iv virus for the NB cell surface, although this hypothesis remains to be proven. Substitution of the aspartic acid residue at position 360 with glycine lowers the net negative charge of the E protein and is expected to increase the affinity of NB15a for glycosaminoglycans, which have been implicated in the process of flavivirus attachment to cultured cells (5, 8, 18, 20, 25, 32). Despite potential effects of this charge neutralization, the presence of the glycine substitution itself may be a more important factor affecting the properties of the E protein. Residue 360 corresponds to position 368 of the tick-borne encephalitis virus envelope protein, which lies in an exposed surface loop joining two beta strands (Dx and E) on the upper medial surface of domain III. The inherent conformational freedom of glycine within loosely structured loops can in some cases significantly affect local folding of proteins and profoundly alter their function (6). In fact, mutation of the E protein of tick-borne encephalitis virus at position 368 has been observed to raise the pH threshold for fusion, but also reduce the efficiency of fusion (17, 19; F. X. Heinz, personal communication). Studies of flaviviruses with mutations in adjacent laterally exposed loops of domain III have also shown that certain substitutions can diminish glycosaminoglycan-dependent binding, alter growth efficiency, and in some cases attenuate mouse neurovirulence (25, 31, 32). Thus, the region surrounding residue 360 in YFV and related viruses appears to be another example of determinants in domain III that can affect virus tropism based on receptor and postreceptor interactions of virus with the host cell during virus entry (46).

It is notable that the G360 substitution confers host-restricted differences in virus spread but not in efficiency of penetration. This could reflect the use of different cell surface molecules for initial attachment and high-affinity binding of YFVs to the cell lines tested in this study. Studies with dengue virus have suggested that cell surface proteins involved in virus attachment and entry may differ among cell lines (18; also reference 8 and references therein). It is possible that the host range differences in spread of NB15a could involve altered binding of virus to the same receptors utilized by YF5.2iv or, alternatively, interaction with different cell surface proteins.

It is not presently clear how the adaptation of YF5.2iv virus to NB cells and the resulting difference in binding interactions with NB cells relates to persistent infection. One possibility is that efficient binding of YF5.2iv virus to NB cells is followed by a high frequency of abortive or nonproductive infections. NB15a may have a selective advantage if it can avoid such a process either by maintaining a conformation which resists inactivation or engages an alternative receptor which is more permissive for virus entry.

It should be mentioned that mutations in domain III of the YFV E protein have been observed to reduce efficiency of focus size and plaque formation through defects in virus assembly (52). In considering this possibility, we examined the production and stabilities of the E proteins of the YF5.2iv and NB15a viruses in cell culture, using immunoprecipitation of radiolabeled E proteins with specific antiserum, and did not observe any obvious difference in the levels of the proteins (data not shown). In addition, although yields of NB15a virus were consistently lower than those of YF5.2iv in growth curve experiments, titers of NB15a ranging between 5 and 6 log PFU/ml were readily generated (Fig. 2 and 4C). These findings suggest that no major defect in virus assembly or stability accounts for the phenotype of NB15a, although subtle effects on these properties cannot be excluded.

Although the G360 mutation confers a decrease in infectivity of YFV virus, the mutations identified in the NS2A and NS3 proteins could also contribute to reduced virus yields if they affect efficiency of RNA replication. In this regard, the fluorescent focus sizes of the YF5.2iv, NB15a and G360 viruses in NB cells appeared generally similar, but the density of antigen staining in the foci was less for NB15a than for YF5.2iv. This may indicate that less virus is produced by any given cell infected with NB15a than with YF5.2iv or, alternatively, that the percentage of antigen-positive cells which are actually producing virus is less in foci of NB15a-infected cells. Results of the infectious center assays on NB and other cell lines (Fig. 3) are consistent with the latter hypothesis, since infection with NB15a was less often productive compared with that of YF5.2iv.

It is also notable that the G360 virus was only mildly impaired in replication in NB cells compared with NB15a (Fig. 2D), which could reflect a role of mutations in the NS2A and NS3 proteins in limiting growth of the NB15a virus in this cell line. Restricted or abortive replication by viruses associated with persistent infections has been observed in other cell culture systems, although the mechanisms responsible have not been determined (4, 51). Since both the NS2A and NS3 proteins encode functions involved in viral RNA replication (12, 30, 53, 54), mutations in these proteins could potentially restrict viral RNA synthesis through cis-acting effects on the activity of viral replication complexes or interactions with host factors required for viral replication.

The basis for persistence of YFV virus in NB cells cannot be defined at this time. Since these cells do not exhibit any apparent cytopathic effects from YFV infection, a reduced ability of the virus to induce cell death may be an important factor. Expression of apoptosis regulators such as bcl-2 has been implicated in Japanese encephalitis virus persistence in mammalian cells (27, 28). It is possible that such factors are involved in the resistance of the NB cells to cytopathic effects and in the establishment of NB15a virus persistence. Another mechanism for persistence is the production of defective interfering virus particles (3, 24, 43). Although we cannot exclude this possibility as a basis for persistence of the NB15a variant, it is worth emphasizing that the G360 virus, which phenotypically resembles NB15a, was prepared by RNA transfection and plaque purification under low-multiplicity, low-passage conditions. This would not be expected to lead to accumulation of defective particles, although we cannot formally exclude a role for these in the process of persistence in this model.

Persistent infections are also known to generate viruses with reduced mouse neurovirulence (21). This could result from either a ts phenotype or host range effects, which reduce the growth efficiency of such viruses in vivo relative to those with higher virulence. Flavivirus mutants which have reduced replication efficiency in cell culture are often attenuated for mouse neurovirulence, indicating that cell culture properties can in some cases predict attenuation phenotypes in the mouse model (39, 42). Mutations in domain III of the E protein have also been observed to modulate mouse neurovirulence, presumably through effects on interactions with membrane receptors (2, 31, 38, 40, 41). Although NB15a exhibited cell culture features which suggested the possibility of reduced mouse neurovirulence, no obvious difference was observed in this property compared with YF5.2iv virus, other than a slightly prolonged survival time after high dose inoculation. However, it remains possible that differences in mortality rates or survival times may occur at doses lower than 1.5 logs used in these experiments, where the ability of the virus to spread may be a more critical factor. Further studies are also needed to evaluate whether the three mutations identified in the NB15a virus differentially affect the neurovirulence properties of YFV in vivo.

Substitutions in the NS2A and NS3 regions of the NB15a virus could influence neurovirulence properties independently, if they affect the efficiency of RNA synthesis and either alter the virus burden generated within infected neural cells or the cellular response to the infection. For instance, a determinant in the helicase domain of the NS3 protein of neuroadapted dengue 1 virus has been implicated in modulation of apoptosis in mouse neuroblastoma cells (11). Since high virus loads have been correlated with increased neurovirulence and with neuronal apoptosis in some models of acute central nervous system viral infections (10, 26), mutations which restrict or enhance the functions of nonstructural proteins in viral replication may act as neurovirulence determinants.

In any case, we are engineering YFVs with mutations in and adjacent to position 360 of the E protein to further analyze the role of this region of domain III in the process of virus binding and entry into host cells. It will also be important to evaluate whether the G360 mutation is sufficient to establish and maintain persistence of YFV in NB cells or whether the substitutions in NS2A and NS3 are also required for this process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIAID (AI-43512) and the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr., Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison, S. L., J. Schalich, K. Stiasny, C. W. Mandl, and F. X. Heinz. 2001. Mutational evidence for an internal fusion peptide in flavivirus envelope protein. J. Virol. 75:4268-4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhardwaj, S., M. Holbrook, R. E. Shope, A. D. T. Barrett, and S. J. Watowich. 2001. Biophysical characterization and vector-specific antagonist activity of domain III of the tick-borne flavivirus envelope protein. J. Virol. 75:4002-4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinton, M. A. 1982. Characterization of West Nile virus persistent infections in genetically resistant and susceptible mouse cells. Virology 116:84-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, L. K., C. L. Liao, C. G. Lin, S. C. Lai, C. I. Liu, S. H. Ma, Y. Y. Huang, and Y. L. Lin. 1996. Persistence of Japanese encephalitis virus is associated with abnormal expression of the nonstructural protein NS1 in host cells. Virology 217:220-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, Y., T. Maguire, R. E. Hileman, J. R. Fromm, J. D. Esko, R. J. Linhardt, and R. E. Marks. 1997. Dengue virus infectivity depends on envelope protein binding to target cell heparan sulfate. Nat. Med. 3:866-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, Y., S. Gorina, P. D. Jeffrey, and N. P. Pavletich. 1994. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor:DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science 265:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crill, W. D., and J. T. Roehrig. 2001. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most efficient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J. Virol. 75:7769-7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Jesus Martinez-Barragan, J., and R. M. del Angel. 2001. Identification of a putative coreceptor on Vero cells that participates in dengue 4 virus infection. J. Virol. 75:7818-7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Despres, P., M.-P. Frenkiel, and V. Deubel. 1993. Differences between cell membrane fusion activities of two dengue type-1 isolates reflect modifications of viral structure. Virology 196:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Despres, P., M.-P. Frenkiel, P. E. Ceccaldi, C. Duarte dos Santos, and V. Deubel. 1998. Apoptosis in the mouse central nervous system in response to infection with mouse-neurovirulent dengue viruses. J. Virol. 72:823-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duarte dos Santos, C. N., M.-P. Frenkiel, M.-P. Courageot, C. F. S. Rocha, M.-C. Vazeille-Falcoz, M. W. Wien, F. A. Rey, V. Deubel, and P. Despres. 2000. Determinants in the envelope E protein and viral RNA helicase NS3 that influence the induction of apoptosis in response to infection with dengue type 1 virus. Virology 274:292-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorbalenya, A. E., E. V. Koonin, A. P. Donchenko, and V. M. Blinov. 1989. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases of flavi- and pestiviruses may be serine proteases. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:3889-3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guirakhoo, F., A. R. Hunt, J. G. Lewis, and J. T. Roehrig. 1993. Selection and partial characterization of dengue 2 virus mutants that induce fusion at elevated pH. Virology 194:219-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa, H., M. Yoshida, T. Shiosaka, S. Fujita, and Y. Kobayashi. 1992. Mutations in the envelope protein of Japanese encephalitis virus affect entry into cultured cells and virulence in mice. Virology 191:158-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinz, F. X. 1986. Epitope mapping of flavivirus glycoproteins. Adv. Virus Res. 31:103-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinz, F. X., and J. T. Roehrig. 1990. Flaviviruses, p. 289-305. In M. H. V. Van Regenmortel and A. R. Neurath (ed.), Immunochemistry of viruses II. The basis for serodiagnosis and vaccines. Elsevier Science Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 17.Heinz, F. X., and S. A. Allison. 2000. Structures and mechanisms in flavivirus fusion. Adv. Virus Res. 55:231-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilgard, P., and R. Stockert. 2000. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans initiate dengue virus infection of hepatocytes. Hepatology 32:1069-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holzmann, H., C. W. Mandl, F. Guirakhoo, F. X. Heinz, and C. Kunz. 1989. Characterization of antigenic variants of tick-borne encephalitis virus selected with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 70:219-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung, S.-L., P. L. Lee, H. W. Chen, L. K. Chen, C. L. Kao, and C. C. King. 1999. Analysis of the steps involved in dengue virus entry into host cells. Virology 257:156-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igarashi, A. 1979. Characteristics of Aedes albopictus cells persistently infected with dengue viruses. Nature 280:690-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khromykh, A. A., and E. G. Westaway. 1994. Completion of Kunjin virus RNA sequence and recovery of an infectious RNA transcribed from a stably cloned full-length cDNA. J. Virol. 68:4580-4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konishi, E., S. Pincus, E. Paoletti, R. E. Shope, T. Burrage, and P. W. Mason. 1992. Mice immunized with a subviral particle containing the Japanese encephalitis virus prM/M and E proteins are protected from lethal JEV infection. Virology 188:714-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancaster, M. U., S. I. Hodgetts, J. S. Mackenzie, and N. Urosevic. 1998. Characterization of defective viral RNA produced during persistent infection of Vero cells with Murray Valley encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 72:2474-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, E., and M. Lobigs. 2000. Substitutions at the putative receptor-binding site of an encephalitis flavivirus alter virulence and host cell tropism and reveal a role for glycosaminoglycans in entry. J. Virol. 74:8867-8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis, J., S. L. Wesselingh, D. E. Griffin, and J. M. Hardwick. 1996. Alphavirus-induced apoptosis in mouse brains correlates with neurovirulence. J. Virol. 70:1828-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao, C. L., Y. L. Lin, J. J. Wang, Y. L. Huang, C. T. Yeh, S. H. Ma, and L. K. Chen. 1997. Effect of enforced expression of human bcl-2 on Japanese encephalitis virus-induced apoptosis in cultured cells. J. Virol. 71:5963-5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao, C. L., Y. L. Lin, S. C. Shen, J. Y. Shen, H. L. Su, Y. L. Huang, S. H. Ma, Y. C. Sun, K. P. Chen, and L. K. Chen. 1998. Antiapoptotic but not antiviral function of human bcl-2 assists establishment of Japanese encephalitis virus persistence in cultured cells. J. Virol. 72:9844-9854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobigs, M., R. Usha, A. Nestorowicz, I. D. Marshall, R. C. Weir, and L. Dalgarno. 1990. Host cell selection of Murray Valley encephalitis virus variants altered at an RGD sequence in the envelope protein and in mouse virulence. Virology 176:587-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackenzie, J. M., A. A. Khromykh, M. K. Jones, and E. G. Westaway. 1998. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology 245:203-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandl, C., S. Allison, H. Holzmann, T. Meixner, and F. X. Heinz. 2000. Attenuation of tick-borne encephalitis virus by structure-based site-specific mutagenesis of a putative flavivirus receptor-binding site. J. Virol. 74:9601-9609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandl, C. W., H. Kroschewski, S. L. Allison, R. Kofler, H. Holzmann, T. Meixner, and F. X. Heinz. 2001. Adaptation of tick-borne encephalitis virus to BHK-21 cells results in the formation of multiple heparan sulfate binding sites in the envelope protein and attenuation in vivo. J. Virol. 75:5627-5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marks, R. M., H. Lu, R. Sundaresan, T. Toida, A. Suzuki, T. Imarani, M. J. Hernaiz, and R. J. Linhard. 2001. Probing the interaction of dengue virus envelope protein with heparin: assessment of glycosaminoglycan-derived inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 44:2178-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh, M., and A. Helenius. 1989. Virus entry into animal cells. Adv. Virus Res. 36:107-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason, P. W., S. Pincus, M. J. Fournier, T. L. Mason, R. E. Shope, and E. Paoletti. 1991. Japanese encephalitis virus-vaccinia recombinants produce particulate forms of the structural membrane proteins and induce high level of protection against lethal JEV infection. Virology 180:294-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMinn, P. C., E. Lee, S. Hartley, J. T. Roehrig, L. Dalgarno, and R. C. Weir. 1995. Murray Valley encephalitis virus envelope protein antigenic variants with altered hemagglutination properties and reduced neuroinvasiveness in mice. Virology 211:10-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMinn, P. C., R. C. Weir, and L. Dalgarno. 1996. A mouse-attenuated envelope protein variant of Murray Valley encephalitis virus with altered fusion activity. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2085-2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMinn, P. C. 1997. The molecular basis of virulence of the encephalitogenic flaviviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 78:2711-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muylaert, I. R., T. J. Chambers, R. Galler, and C. M. Rice. 1996. Mutagenesis of the N-linked glycosylation sites of the yellow fever virus NS1 protein: Effects on virus replication and mouse neurovirulence. Virology 222:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni, H., and A. D. T. Barrett. 1998. Attenuation of Japanese encephalitis virus by selection of its mouse brain membrane receptor preparation escape variants. Virology 241:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ni, H., K. D. Ryman, H. Wang, M. F. Saeed, R. Hull, D. Wood, P. D. Minor, S. J. Watowich, and A. D. T. Barrett. 2000. Interaction of yellow fever virus French neurotropic vaccine strain with monkey brain: characterization of monkey brain membrane receptor escape variants. J. Virol. 74:2903-2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pletnev, A. G., M. Bray, and C.-J. Lai. 1993. Chimeric tick-borne encephalitis and dengue type 4 viruses: effects of mutations on neurovirulence in mice. J. Virol. 67:4956-4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poidinger, M., R. J. Coelen, and J. S. Mackenzie. 1991. Persistent infection of Vero cells by the flavivirus Murray Valley encephalitis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 72:573-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Randolph, V. B., and J. L. Hardy. 1988. Establishment and characterization of St. Louis encephalitis virus persistent infections in Aedes and Culex mosquito cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 69:2189-2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Randolph, V. B., and J. L. Hardy. 1988. Phenotypes of St. Louis encephalitis virus mutants produced in persistently infected mosquito cell cultures. J. Gen. Virol. 69:2199-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rey, F. A., F. X. Heinz, C. Mandl, C. Kunz, and S. C. Harrison. 1995. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 A resolution. Nature 375:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rice, C. M., A. Grakoui, R. Galler, and T. J. Chambers. 1989. Transcription of infectious yellow fever RNA from full-length cDNA templates produced by in vitro ligation. New Biol. 1:85-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rice, C. M. 1996. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 931-960. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 49.Ryman, K. D., H. Xie, T. N. Ledger, G. A. Campbell, and A. D. T. Barrett. 1997. Antigenic variants of yellow fever virus with an altered neurovirulence phenotype in mice. Virology 230:376-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryman, K. D., T. N. Ledger, G. A. Campbell, S. J. Watowich, and A. D. T. Barrett. 1998. Mutation in a 17D-204 vaccine substrain-specific envelope protein epitope alters the pathogenesis of yellow fever virus in mice. Virology 244:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmaljohn, C., and C. D. Blair. 1977. Persistent infection of cultured mammalian cells by Japanese encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 24:580-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van der Most, R. G., J. Corver, and J. H. Strauss. 1999. Mutagenesis of the RGD motif in the yellow fever virus 17D envelope protein. Virology 265:83-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warrener, P., J. K. Tamura, and M. S. Collett. 1993. An RNA-stimulated NTPase activity associated with yellow fever virus NS3 protein expressed in bacteria. J. Virol. 67:989-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wengler, G., and G. Wengler. 1993. The NS3 nonstructural protein of flaviviruses contains an RNA triphosphatase activity. Virology 197:265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]