Abstract

Glycoprotein B (gB) is the most highly conserved of the envelope glycoproteins of human herpesviruses. The gB protein of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) serves multiple roles in the life cycle of the virus. To investigate structural properties of gB that give rise to its function, we sought to determine the disulfide bond arrangement of gB. To this end, a recombinant form of gB (gB-S) comprising the entire ectodomain of the glycoprotein (amino acids 1 to 750) was constructed and expressed in insect cells. Proteolytic fragmentation and mass spectrometry were performed using purified gB-S, and the five disulfide bonds that link 10 of the 11 highly conserved cysteine residues of gB were mapped. These bonds are C94-C550, C111-C506, C246-C250, C344-C391, and C573-C610. This configuration closely parallels the disulfide bond configuration of herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2) gB (N. Norais, D. Tang, S. Kaur, S. H. Chamberlain, F. R. Masiarz, R. L. Burke, and F. Markus, J. Virol. 70:7379-7387, 1996). However, despite the high degree of conservation of cysteine residues between CMV gB and HSV-2 gB, the disulfide bond arrangements of the two homologs are not identical. We detected a disulfide bond between the conserved cysteine residue 246 and the nonconserved cysteine residue 250 of CMV gB. We hypothesize that this disulfide bond stabilizes a tight loop in the amino-terminal fragment of CMV gB that does not exist in HSV-2 gB. We predicted that the cysteine residue not found in a disulfide bond of CMV gB, cysteine residue 185, would play a role in dimerization, but a cysteine substitution mutant in cysteine residue 185 showed no apparent defect in the ability to form dimers. These results indicate that gB oligomerization involves additional interactions other than a single disulfide bond. This work represents the second reported disulfide bond structure for a herpesvirus gB homolog, and the discovery that the two structures are not identical underscores the importance of empirically determining structures even for highly conserved proteins.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a highly prevalent human pathogen that causes significant disease in the immunocompromised host. CMV is a member of the Herpesviridae family of enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses that establish a lifelong relationship with their host. The complexity of the CMV life cycle is paralleled by the structural intricacy of the virion. CMV has at least nine membrane-associated glycoproteins in its envelope (10, 16-19). Of these, glycoprotein B (gB) is the most abundant and highly conserved glycoprotein among the herpesviruses.

gB plays key roles in the process of CMV entry into host cells. This process is a multistep cascade beginning with attachment of the virus to the cell surface and ending with fusion of the virus envelope with the cell plasma membrane. Attachment of CMV to host cells is mediated by an initial interaction between viral gB and/or gM and cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (12, 18). The virus then transitions to a more stable binding state as gB engages its non-heparin cellular receptor (1). The current model suggests that gB, in cooperation with other viral glycoproteins, directs the fusion of the viral and cell plasma membranes by a pH-independent fusion event (11). Although gB and gH are thought to have a direct role in the fusion process, the complete molecular composition of the fusion machinery remains to be characterized (25). gB also plays a key role in the “priming” of the host cell's transcriptional machinery prior to viral replication. In addition to facilitating the attachment of the virion to the cell surface, a significant biological consequence of the interaction of gB with its non-heparin, cellular receptor is the profound reprogramming of cellular gene expression. Indeed, upon binding of gB to host cells, the transcriptional profile of hundreds of cellular genes is altered in a manner that is analogous to treatment with interferon α/β (29). The full biological consequence of the initiation of an antiviral state induced by gB has yet to be elucidated, but the response is ultimately dampened in CMV-infected cells (6).

gB is encoded by the UL55 gene of the AD169 strain of human CMV and is synthesized as a 906-amino-acid precursor molecule in infected cells (3). An amino-terminal signal sequence directs the nascent polypeptide to the endoplasmic reticulum wherein gB rapidly associates into disulfide bond-dependent homodimers (4). The ectodomain of gB is highly decorated with asparagine-linked oligosaccharides although which of the 19 potential NXS/T consensus sites are utilized is not certain (5). Late in the trafficking pathway, gB is proteolytically processed by the host subtilisin-like enzyme, furin, into the amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal fragments, gp116 and gp55, respectively (3). The two fragments remain covalently associated by disulfide bonds. gB has a broad and complex trafficking pattern in infected cells that includes expression at the cell surface, where it can be internalized and recycled back to the cell plasma membrane. It is of particular interest to this study that the structure of the mature form of gB is highly dependent on both intermolecular and intramolecular disulfide bonds.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) also encodes a gB homolog (7). Like its CMV counterpart, it is known to play a role in HSV-2 entry into cells and is essential for fusion of the virus envelope with the cell plasma membrane (8). The sequence of HSV-2 gB shows many similarities to CMV gB, including 10 highly conserved cysteine residues (13). As is the case for other viral envelope glycoproteins, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) gp120 and HSV-2 gD, all of the ectodomain cysteine residues of HSV-2 gB are disulfide bonded (22, 23, 26). Presumably, these disulfide bonds create or stabilize important functional conformations in these glycoproteins. Prior to this work, HSV-2 gB was the only gB homolog for which the disulfide bond configuration was known.

Paramount to a full understanding of the function of gB in CMV entry is a detailed knowledge of its structure. In this study, we sought to establish a framework of structural information for gB; thus, our goal was to determine the disulfide bond configuration of the 11 ectodomain cysteine residues in gB. These results provide the foundation for higher resolution models that endeavor to explain the functions of gB in the context of its structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of gB-S.

A recombinant baculovirus strain encoding amino acids 1 to 750 of CMV AD169 gB (gB-S) with a carboxyl-terminal His6 tag was constructed by PCR amplification using the following primer pair: 5′-CGG GAT CCG ACG AAC ATG GAA-3′ and 5′-GCT CTA GAA TTA TGA TGA TGA TGA TGA TGG GGG TTT TTG AGG AAG-3′ (accession number X04606). This fragment was cloned into the baculovirus transfer vector pVL1393 by using the BamHI and XbaI restriction sites. The recombinant baculovirus was produced in BTI-TN-5B1-4 cells by using BaculoGold DNA (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Recombinant protein was purified from culture medium essentially as described previously (9). In brief, BTI-TN-5B1-4 insect cells were grown in monolayers and infected with the recombinant baculovirus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. The viral inoculum was removed 18 to 24 h postinfection, and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.2). The infected cells were maintained in serum-free insect medium for the duration of the infection. At 72 h postinfection, the supernatants were harvested and dialyzed against PBS for approximately 16 h using a 60,000-molecular-weight-cutoff SpectraPor dialysis membrane. The dialyzed culture medium was supplemented with glycerol to a final concentration of 10%, and imidazole was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose beads were added to the dialyzed culture medium and incubated in batch for 2 h at 4°C. The slurry was placed in a column, and the settled beads were washed in sequence with 20 bed volumes of both a low pH wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 10% glycerol, pH 6.0) and an imadazole-containing wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M sodium chloride, 10% glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.0). The His6-tagged protein was eluted by the addition of elution buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M sodium chloride, 10% glycerol, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.5). The eluted protein was dialyzed against PBS for approximately 16 h in a 60-kDa MWCO SpectraPor dialysis membrane. Glycerol was added to the dialyzed product to a final concentration of 10% prior to storage at −80°C.

Generation of peptides.

Purified gB-S (approximately 2 mg) was deglycosylated by the addition of 50,000 U of PNGase F (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.). The reaction mixture was incubated for 16 to 24 h at 37°C. The products were dialyzed against 5% acetic acid (pH 2.5, 4°C) for approximately 16 h, and the protein was dried in a SpeedVac concentrator. The dried protein was suspended in 70% formic acid containing a 100- to 300-fold molar excess of cyanogen bromide (CNBr) to methionine residues. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 24 h at room temperature and in the dark. The digest products were diluted twofold by the addition of water, and the products were dried in a SpeedVac concentrator. The CNBr-digested peptides were suspended in water and an additional 10,000 U of PNGase F was added. The reaction mixture was incubated for an additional 14 to 16 h at 37°C. The CNBr-generated gB-S peptides were separated on a Beckman System Gold High Performance Liquid Chromatography instrument with a 5-μm-diameter-particle Vydac C18 column (4.6 by 250 mm) at 1 ml per min with a linear gradient of 0.09 to 63% acetonitrile in 0.088% trifluoroacetic acid. Absorbance was measured at 215 nm. Individual fractions containing gB-S peptides were concentrated in a SpeedVac concentrator and buffered with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 7.9). For reduced gB-S peptides, dithiothreitol (DTT) was added at a fivefold molar excess to total thiols and the tube headspace was purged with nitrogen. The reaction vessel was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Iodoacetamide was added at a fivefold molar excess to total thiols and the tube headspace was purged with nitrogen. The reaction vessel was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and in the dark. All gB-S peptides were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) and/or matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MS) [MALDI-TOF (MS)] as described below.

Mass spectrometry.

Electrospray ionization MS (ESIMS) was performed with an Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex API 365 LC/MS/MS triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. MALDI-TOF (MS) was performed in positive-ion linear mode on a Bruker BIFLEX III instrument.

Generation of cysteine mutant.

A full-length, mutant version of CMV AD169 gB (C185A) was constructed by amplifying a region upstream of and including the cysteine residue 185 codon with the following primer pair: 5′-GCC TGG TAG TCT GCG TTA ACC TGT GTA TCG TCT GTC TGG GT-3′ (OML1) and 5′-CGC GGC TGT AGG AAC TGT AAG CTT GAG CAA ACT TGT TGA TG-3′ (OML8). This product introduced a cysteine-to-alanine substitution at cysteine residue 185 (bold). A region downstream of and including the cysteine residue 185 codon was amplified with the following primer pair: 5′-CAT CAA CAA GTT TGC TCA AGC TTA CAG TTC CTA CAG CCG CG-3′ (OML7) and 5′-ATG ATA AGG ATA CTT GGA GCG CGC AGT AGT GAT GGT CAG C-3′ (OML9). This product also introduced a cysteine-to-alanine substitution at cysteine residue 185 (bold). The two products are complementary across a region encompassing OML7 and OML8, and this allowed the two fragments to be spliced by PCR amplification using OML1 and OML9. The primers OML1 and OML9 contain an HpaI site and a BssH II site, respectively, for ligation into a mammalian expression vector encoding full-length gB. The resulting plasmid, pML10, encodes full-length gB with cysteine residue 185 mutated to alanine. The fidelity of this mutation was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

Transient transfections.

Human 293T cells were transiently transfected with pML10 by calcium phosphate precipitation (15). Following incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the transfection reagents were removed and replaced with fresh 10% fetal bovine serum-supplemented Dulbecco minimal essential medium containing 5 mM sodium butyrate. Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection in 1% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate} and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting with the monoclonal anti-gB antibody 27-78 (2).

RESULTS

Notes on nomenclature.

Digestion of gB-S by cyanogen bromide is expected to result in 16 fragments under reducing conditions (Fig. 1). Each of the nine fragments containing a cysteine residue is named according to the number of the cysteine residue within that fragment. For example, the CNBr-generated fragment from amino acids 24 to 96 that contains cysteine residue 94 is denoted CNBr-C94.

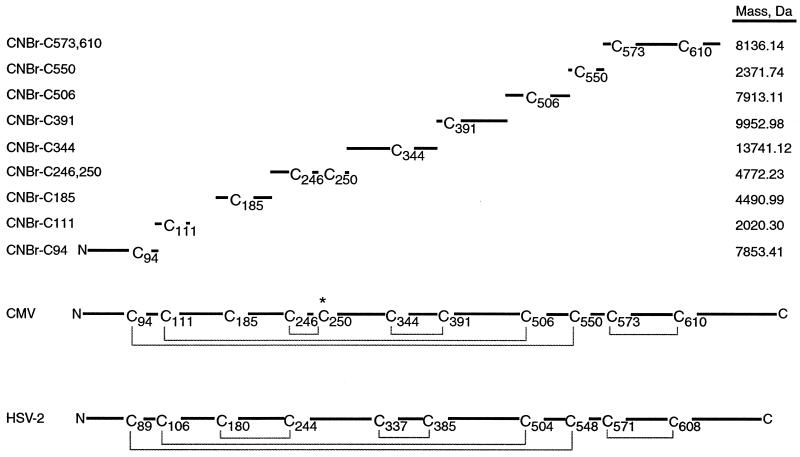

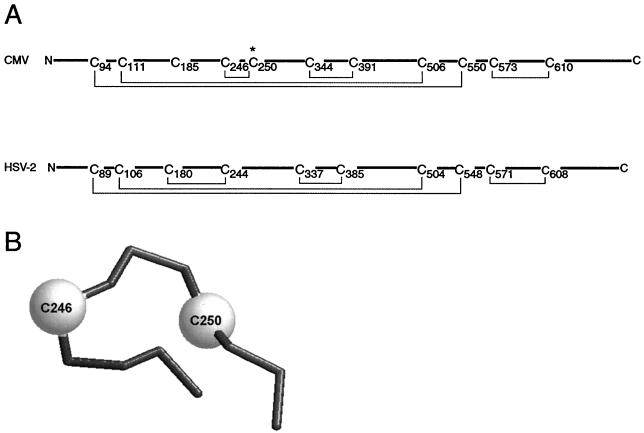

FIG. 1.

gB-S peptides expected from CNBr digestion and initial model of disulfide bonds of CMV gB. Shown is a sequence alignment of the ectodomains of gB from CMV and HSV-2. The amino terminus of each glycoprotein is oriented at left and cysteine residues are numbered sequentially. The asterisk denotes the additional cysteine residue of CMV gB that is predicted to be unpaired. The disulfide bond configuration of HSV-2 gB is indicated by solid lines connecting appropriate cysteine pairs. Due to the high conservation of cysteine residues between the two gB homologs, our initial model for the disulfide bond configuration of CMV gB paralleled that of HSV-2 gB. Shown above the CMV gB sequence are the positions and sizes of cysteine-containing fragments of CMV gB expected from cyanogen bromide digestion. Peptide fragments that do not contain cysteine residues were omitted for clarity.

Initial model of disulfide bonds of gB.

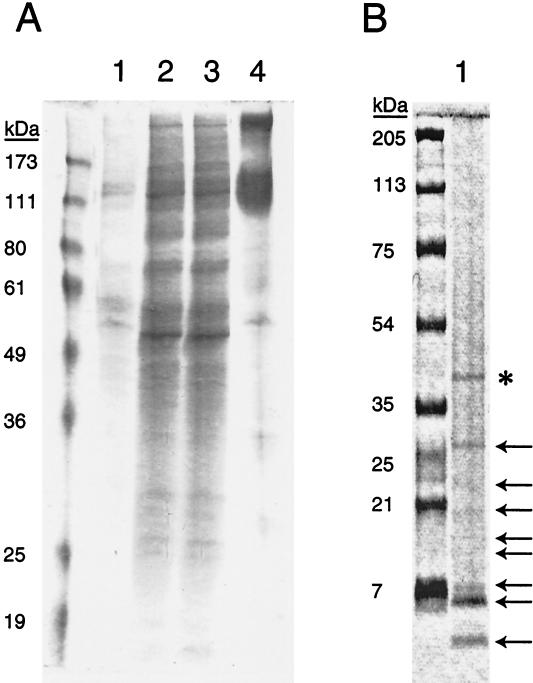

A sequence alignment of gB homologs from distinct herpesviruses shows that many features are conserved. Among these are the amino-terminal signal sequence, transmembrane domain, a membrane-proximal hydrophobic region, and a variable number of consensus sites for asparagine-linked oligosaccharride addition. Most remarkable, however, is the conservation of 10 ectodomain cysteine residues in all but one gB homolog. The exception to this trend is CMV gB, which has 11 cysteine residues. As disulfide bonds can be major determinants of stabilizing structural folds and motifs in proteins, it is probable that this conservation of cysteine residues translates into a conservation of tertiary structure for these gB homologs. The disulfide bonding pattern for HSV-2 gB was previously solved, and it represented the only gB homolog for which this element of structure was known prior to this work (26). Therefore, we applied that model to predict the disulfide bonding pattern of CMV gB (Fig. 1). The disparity between the 11 cysteine residues of CMV gB and the 10 residues of HSV-2 gB can potentially be explained in terms of the different oligomerization strategies employed by these glycoproteins. Although both glycoproteins form dimers, HSV-2 gB dimerizes through noncovalent interactions (21) while CMV gB dimerizes in a disulfide bond-dependent manner (3). Thus, the extra, unpaired cysteine residue of CMV gB is likely involved in dimerization. To solve the disulfide bonding pattern of gB, a soluble, recombinant form of gB (gB-S) encoding the entire ectodomain (amino acids 1 to 750) was produced. Expression in recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells resulted in a mixture of monomeric and dimeric gB-S that were both enriched in the final, purified product from nickel affinity chromatography (Fig. 2). Purified gB-S was recognized by several conformation-specific anti-gB antibodies, and cell stimulation assays showed that the purified gB-S was biologically functional (27).

FIG. 2.

Purification of gB-S and digestion with CNBr. Fractions collected during the purification of gB-S were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. (A) Lane 1, predialysis supernatant; lane 2, postdialysis supernatant; lane 3, column flowthrough; lane 4, elution. (B) Digestion of gB-S with cyanogen bromide (lane 1) resulted in 16 fragments. Shown in this Coomassie blue-stained gel of CNBr-digested gB-S are numerous gB-S fragments (arrows) as well as PNGase F used to deglycosylate the peptides (*).

Peptide mapping strategy.

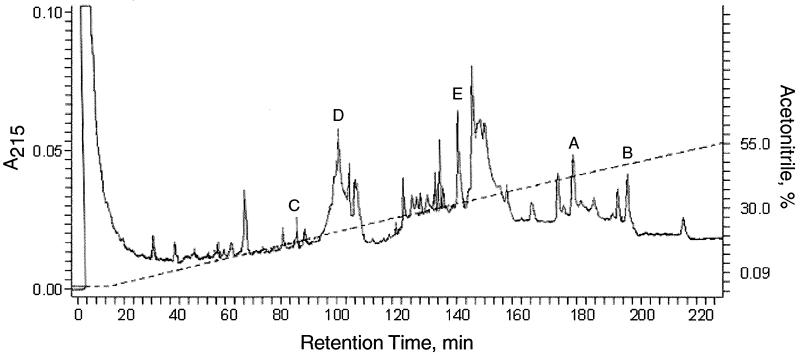

To elucidate the pattern of disulfide bonding in gB-S, we employed a general strategy involving proteolytic fragmentation under oxidizing conditions using CNBr followed by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation of the peptide fragments (Fig. 3). Sixteen peptide fragments are predicted from CNBr digestion of gB-S, and nine of these peptide fragments contain cysteine residues (Fig. 1). HPLC-separated peptides were subjected to either ESIMS or MALDI-TOF (MS). When the observed mass of a gB-S peptide corresponded to the theoretical mass of two cysteine-containing gB-S fragments disulfide bonded together, the peptides were reduced and modified with iodoacetamide and further analyzed by MALDI-TOF (MS). Utilizing this technique, 10 of the 11 ectodomain cysteine residues of gB-S were assigned to specific disulfide bonds.

FIG. 3.

HPLC separation of CNBr-generated gB-S peptides. All of the peaks visible in this trace were analyzed by MALDI-TOF (MS) as indicated in Materials and Methods, and fractions labeled A through E were assigned to gB-S peptides that contain cysteine residues. All gB-S peptides that did not contain cysteine residues were identified by MALDI-TOF (MS) but are not labeled in this HPLC trace.

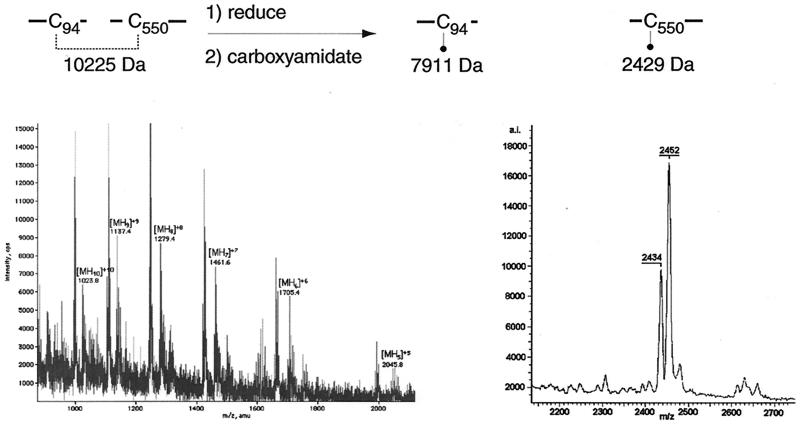

Disulfide bond Cys94-Cys550.

The ESIMS spectrum of fraction A contained evidence for two gB-S peptides linked by a disulfide bond between cysteine residues 94 and 550 (Fig. 4). The linked peptides were identified from the ion series of m/z 1,023.62, 1,137.22, 1,279.23, and 1,461.83, which corresponds to a peptide fragment with the following protonation states, respectively: [MH10]+10, [MH9]+9, [MH8]+8, and [MH7]+7. The mass was calculated at 10,225.89 ± 0.18 Da, which corresponds to the theoretical mass (10,225.12 Da) of CNBr-C94 (7,853.41 Da) disulfide bonded to CNBr-C550 (2,371.74 Da). In addition, as CNBr-C94 contains the amino terminus of the mature gB molecule, these data show that cleavage of the signal sequence occurs between amino acids 23 and 24, thus making Ser24 the first amino acid in the mature form of gB. Upon reduction with DTT and carboxyamidation with iodoacetamide, this peptide was resolved by MALDI-TOF (MS) into a peptide with a mass of 2,434 Da. This mass corresponds to CNBr-C550 with a carboxyamidated cysteine residue. Also present in this spectrum is a water adduct of the carboxyamidated CNBr-C550 peptide with a mass of 2,452 Da. The peptide fragment corresponding to CNBr-C94 was not identified after reduction and carboxyamidation with iodoacetamide. This may have been due to ion suppression in the mass spectrometer.

FIG. 4.

Disulfide bond C94-C550. Spectra of fraction A before (left) and after (right) treatment with DTT and iodoacetamide. The fragment corresponding to CNBr-C94 was not identified in the spectrum following reduction and carboxyamidation. The m/z ratio and charge state of each peak are indicated.

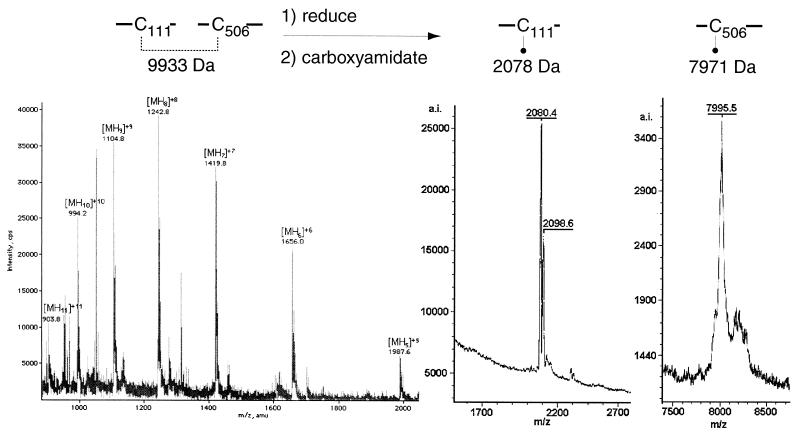

Disulfide bond Cys111-Cys506.

The ESIMS spectrum of fraction B contained evidence for two peptides linked by a disulfide bond between cysteine residues 111 and 506 (Fig. 5). The linked peptides were identified from the ion series of m/z 904.02, 994.22, 1,104.82, 1,242.42, 1,419.83, and 1,656.24, which corresponds to a peptide fragment with the following protonation states, respectively: [MH11]+11, [MH10]+10, [MH9]+9, [MH8]+8, [MH7]+7, and [MH6]+6. The mass was calculated at 9,933.79 ± 1.18 Da, which corresponds to the theoretical mass (9,933.41 Da) of CNBr-C111 (2,020.3 Da) disulfide bonded to CNBr-C506 (7,913.11 Da). Upon reduction with DTT and carboxyamidation with iodoacetamide, this peptide was resolved by MALDI-TOF (MS) into two smaller peptides with masses of 2,078 and 7,971 Da. These masses correspond to CNBr-C111 with a carboxyamidated cysteine residue and a water adduct of CNBr-C506, also with a carboxyamidated cysteine residue. Also present in the spectrum of reduced, carboxyamidated CNBr-C506 is a water adduct of this peptide.

FIG. 5.

Disulfide bond C111-C506. Spectra of fraction B before (left) and after (right) treatment with DTT and iodoacetamide. The m/z ratio and charge state of each peak are indicated.

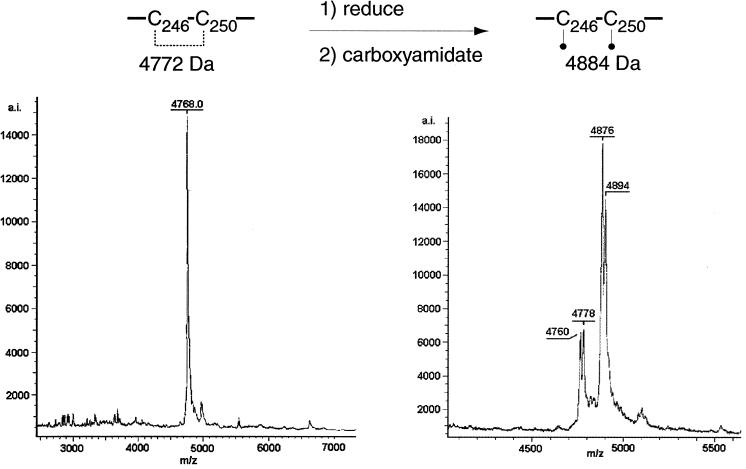

Disulfide bond Cys246-Cys250.

The MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of fraction C contained evidence for one peptide with an intramolecular disulfide linkage between cysteine residues 246 and 250 (Fig. 6). The peptide was identified as a singly charged ion with a mass of 4,768 ± 4.8 Da, which corresponds to the theoretical mass (4,772.23 Da) of CNBr-C246,C250 with an intramolecular disulfide bond between the two cysteine residues. Upon reduction with DTT and carboxyamidation with iodoacetamide, this peptide was resolved by MALDI-TOF (MS) into a peptide with a mass of 4,876 Da. This mass corresponds to CNBr-C246,C250 with two carboxyamidated cysteine residues. Also present in this spectrum is a water adduct of the peptide.

FIG. 6.

Disulfide bond C246-C250. Spectra of fraction C before (left) and after (right) treatment with DTT and iodoacetamide. The m/z ratio and charge state of each peak are indicated.

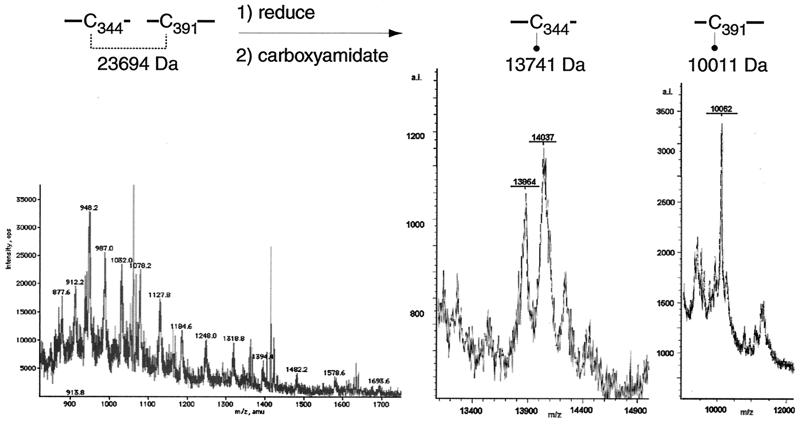

Disulfide bond Cys344-Cys391.

The ESIMS spectrum of fraction D contained evidence for two peptides linked by a disulfide bond between cysteine residues 344 and 391 (Fig. 7). The linked peptides were found with protonation states from [MH26]+26 to [MH11]+11. The mass was calculated at 23,694 Da, which corresponds to the theoretical mass (23,694.1 Da) of CNBr-C344 (13,741.12 Da) disulfide bonded to CNBr-C391 (9,952.98 Da). It must also be noted that this mass includes 1,345 Da that are predicted to be removed from CNBr-C391 by the proteolytic activity of furin. Analysis of gB-S by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions reveals that some of the mature gB monomer is not cleaved by furin in this insect cell expression system as it does not collapse to its constituent amino- and carboxyl-terminal fragments. This uncleaved form of the monomer is apparently what gives rise to the peptide identified in this fraction. Upon reduction with DTT and carboxyamidation with iodoacetamide, this peptide was resolved by MALDI-TOF (MS) into two smaller peptides with masses of 13,864 and 10,062 Da. The peptide with a mass of 13,864 Da is larger than the predicted mass of the CNBr-C344 fragment by approximately 120 Da while the peptide with a mass of 10,062 Da is larger than the predicted mass of the CNBr-C391 fragment by approximately 51 Da. The discrepancies between the predicted and observed masses may be attributed to the presence of two and one additional modifications by iodoacetamide on each peptide, respectively.

FIG. 7.

Disulfide bond C344-C391. Spectra of fraction D before (left) and after (right) treatment with DTT and iodoacetamide. The m/z ratio and charge state of each peak are indicated.

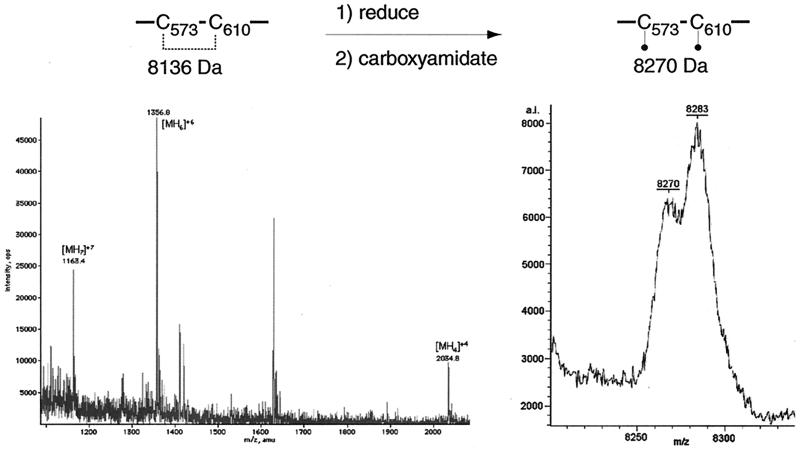

Disulfide bond Cys573-Cys610.

The ESIMS spectrum of fraction E contained evidence for one peptide with an intramolecular disulfide linkage between cysteine residues 573 and 610 (Fig. 8). The peptide was identified from the ion series of m/z 1,163.42, 1,356.83, 1,628.04, and 2,034.82, which corresponds to a peptide fragment with the following protonation states, respectively: [MH7]+7, [MH6]+6, [MH5]+5, and [MH4]+4. The mass was calculated at 8,136 ± 0.91 Da, which corresponds to the theoretical mass (8,136.14 Da) of CNBr-C573,C610 with an intramolecular disulfide bond between the two cysteine residues. Upon reduction with DTT and carboxyamidation with iodoacetamide, this peptide was resolved by MALDI-TOF (MS) into a peptide with a mass of 8,270 Da. This mass corresponds to CNBr-C573,C610 with two carboxyamidated cysteine residues. Also present in this spectrum is a water adduct of the doubly carboxyamidated CNBr-C573,C610 peptide fragment.

FIG. 8.

Disulfide bond C573-C610. Spectra of fraction E before (left) and after (right) treatment with DTT and iodoacetamide. The m/z ratio and charge state of each peak are indicated.

Oligomerization.

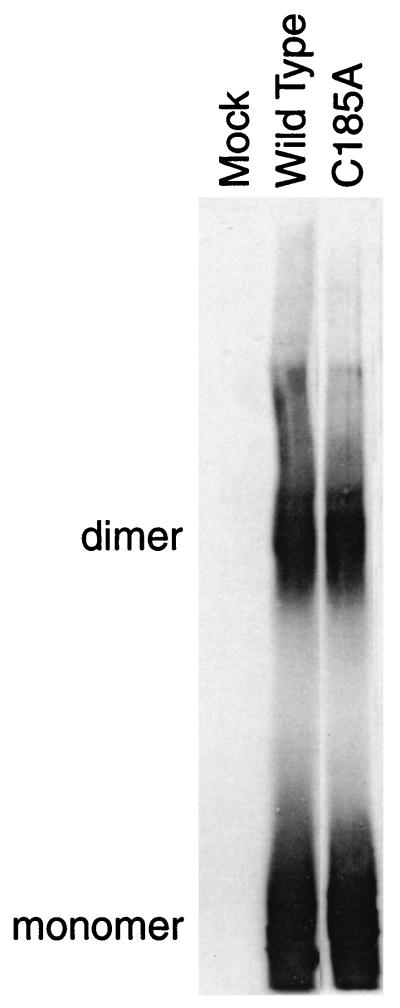

The gB-S peptide fragment containing cysteine residue 185 was not identified by MS. To address the role of cysteine residue 185 in disulfide bond-dependent dimerization, we generated a full-length, mutant gB with cysteine residue 185 substituted with alanine (C185A). This mutant protein was transiently expressed in human 293T cells, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and detected by immunoblotting with an anti-gB antibody. We hypothesized that this cysteine substitution mutant would be defective in forming the gB dimer. In contrast to our predictions, this mutant did not show a defect in disulfide bond-dependent dimerization compared to wild-type gB (Fig. 9). This result suggests that multiple interactions are required for oligomerization rather than a single disulfide bond.

FIG. 9.

Cysteine substitution mutant C185A. The additional cysteine residue of CMV gB, C185, was predicted to be involved in dimerization between two gB monomers. Shown is an immunoblot of 1% CHAPS-soluble cell lysates from wild-type gB or C185A mutant gB expressing 293T cells. In contrast to predictions, the C185A mutant does not show a significant defect in dimerization.

DISCUSSION

Model of disulfide bonds of gB.

These data lead to a model for the disulfide bonding pattern of CMV gB that is similar but not identical to that of HSV-2 gB (Fig. 10A). In this model, disulfide bonds exist between cysteine residues C94 and C550, as well as C111 and C506, and these two disulfide bonds maintain the association of the proteolytically derived amino- and carboxy-terminal fragments of gB. These two disulfide bonds are consistent with those of HSV-2 gB despite the fact that the HSV-2 gB homolog is not proteolytically processed (26). In light of this difference in processing, it is possible that a major structural difference exists between these two gB homologs in the organization of the amino terminus and the carboxy terminus of the glycoprotein. Cleavage of CMV gB by furin may allow for conformational freedom of the amino-terminal fragment relative to the carboxy-terminal fragment that would not exist for HSV-2 gB. The significance of this possible structural difference is not yet clear. Cysteine residues C344 and C391, as well as cysteine residues C573 and C610, are also linked by disulfide bonds in gB. These two disulfide bonds are conserved in HSV-2 gB and likely reflect similarities in the structures of these two glycoproteins.

FIG. 10.

Model of disulfide bonds of CMV gB. (A) Shown is an alignment of the ectodomains of gB from CMV (top) and HSV-2 (bottom). The amino terminus is oriented at left and cysteine residues are numbered sequentially. The disulfide bond configurations of both HSV-2 gB and CMV gB are indicated by solid lines connecting appropriate cysteine pairs. The similarity of disulfide bonding reflects the high conservation of cysteine residues between these two glycoproteins although significant differences exist in the region from C185 to C250 of CMV gB. The asterisk denotes the additional cysteine residue of CMV gB that was predicted to be unpaired but was found in a disulfide bond with C246. (B) The disulfide bond between CMV gB C246 and C250 likely maintains these residues in a tight loop that may not exist in the HSV-2 gB homolog. This model shows a wireframe view of the alpha carbon atoms of the putative C246-C250 loop. The structure was modeled using the 3D-PSSM protein fold recognition (threading) server (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/∼3dpssm/).

Disulfide bond-stabilized loop.

The importance of disulfide bond-stabilized loops in glycoproteins is underscored by the disulfide-bonded loop/chain reversal region of human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 and murine leukemia virus TM proteins as well as HIV-1 gp41. In these viral glycoproteins, a disulfide bond-stabilized loop connects the antiparallel N- and C-terminal helical regions and mediates the chain reversal of the two modular domains to promote helical packing. It has also been shown that conservative substitutions in the HIV-1 gp41 disulfide-bonded loop abolished association with gp120 as well as cell-cell fusion activity (24). In CMV gB, a disulfide bond exists between residues C246 and C250. This likely creates a tight loop in the structure of gB (Fig. 10B) because only three amino acids separate the two cysteine residues in the primary sequence (14, 20). This particular disulfide bond differs from the analogous disulfide bond of HSV-2 gB and may represent a major structural difference between these two gB homologs. However, the functional significance of this disulfide bond and the tight loop that it likely creates is unknown. An in-frame, four-amino-acid insertion mutant six amino acids downstream of C250 (mutant I-256) resulted in the loss of recognition by monoclonal antibody 27-39, which recognizes a folded and conformation specific epitope, indicating that this region may be important in the final folded form of gB (28). The I-256 insertion mutant also showed a defect in proteolytic processing by furin despite the fact that the furin cleavage site is over 200 amino acids downstream of the insertion. Therefore, it is probable that the region encompassing the C246-C250 disulfide bond and associated loop is an important structural component of the glycoprotein. Based on these data, we predict that the disulfide bond between cysteine residues C246 and C250 and the loop that this bond likely creates is important for the function of gB, perhaps as a surface loop involved in interactions with the gB receptor or as a structural component linking two functional domains. Since CMV gB does not have heptad repeat regions indicative of coiled coils on both sides of the C246-C250 loop, it is unlikely that this region facilitates the packing of coiled, helical domains, as is the case for HIV gp41 (24). However, it remains possible that this region is important for linking important functional domains of gB. We are currently investigating the role of this region in more depth.

Oligomerization.

The peptide fragment of gB-S containing cysteine residue 185 was not identified by mass spectrometry following proteolytic fragmentation and HPLC separation. It is possible that this peptide has inefficient binding or that release from the C18 reverse-phase column used to separate the gB-S peptide fragments was such that it never eluted in a concentrated peak that could be collected and analyzed. Alternatively, the presence of one or more contaminating peptide fragments coeluting from the C18 column with the C185-containing gB-S peptide fragment may have resulted in ion suppression of the C185-containing gB-S peptide at the ion detector in the mass spectrometer. Due to the lack of detection of CNBr-C185, no disulfide bond could be assigned to this cysteine residue. A cysteine substitution mutant was constructed (C185A) and tested for its ability to form dimers in human 293T cells in a transient-transfection assay. In contrast to our predictions, this mutant did not show a defect in dimerization in this assay. It is possible that cysteine residues other than C185 are directly involved in forming the disulfide bond-dependent dimer. One limitation of the proteolytic fragmentation strategy employed is that we can not discriminate between disulfide bonds that are intermolecular and those that are intramolecular for cysteine residues C94, C111, C344, C391, C506, and C550. We have determined that C94 is disulfide bonded to C550, and we have designated this as an intramolecular disulfide bond in the above model, but C94 from one monomer may be disulfide bonded to C550 in an adjacent monomer, thus contributing to the disulfide bond-dependent dimerization of gB. This holds true for the disulfide bonds between C111-C506 and C344-C391 as well. Since CNBr-C246,C250 and CNBr-C573,C610 both contain the disulfide-bonded cysteine residues within the same proteolytically derived gB-S peptide fragment, these disulfide bonds are clearly intramolecular and do not contribute to dimerization. We are currently constructing and testing a panel of cysteine substitution mutants to test the hypothesis that cross talk occurs between cysteine residues from one monomer to an adjacent monomer in the gB dimer.

These results clearly show that the pattern of disulfide bonding in CMV gB is both extensive and complex. Although showing similarity to the closely related HSV-2 gB homolog, CMV gB has significant differences in its disulfide bond arrangements that likely lead to differences in its overall structure compared to that of HSV-2 gB. We now have a foundation of structural information for CMV gB upon which to build more refined models. In addition to defining the mature amino terminus of gB, beginning at amino acid 24, we have identified a potential disulfide-bonded loop between cysteine residues 246 and 250. We have also shown that oligomerization is more complex than a single disulfide bond between monomers. It is probable that multiple interactions involving intermolecular disulfide bonds between adjacent monomers are responsible for forming the gB dimer. These data allow us the opportunity to dissect the various domains of CMV gB in search of structure/function correlates. Ultimately, we hope to apply these results towards the acquisition of higher-resolution models to be attained by X-ray crystallography. The possibility of applying structure-assisted, rational drug design to herpesvirus envelope glycoproteins would open new, unexplored avenues toward the development of vaccines and anti-viral treatments.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by U. S. Public Health Service grant RO1 AI-34998 and by Molecular Biosciences Training Grant T32 GM 07215.

We acknowledge Amy Harms, Jim Brown, and Herb Grimeck of the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center for providing training and valuable expertise in ESIMS and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as well as reverse-phase HPLC separation. We also acknowledge Kathy Boyle for constructing the recombinant gB-S baculovirus and members of the Compton laboratory for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyle, K. A., and T. Compton. 1998. Receptor-binding properties of a soluble form of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 72:1826-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt, W. J. 1984. Neutralizing antibodies detect a disulfide-linked glycoprotein complex within the envelope of human cytomegalovirus. Virology 135:369-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britt, W. J., and D. Auger. 1986. Synthesis and processing of the envelope gp55-116 complex of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 58:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britt, W. J., and L. G. Vugler. 1992. Oligomerization of the human cytomegalovirus major envelope glycoprotein complex gB (gp55-116). J. Virol. 66:6747-6754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britt, W. J., and L. G. Vugler. 1989. Processing of the gp55-116 envelope glycoprotein complex (gB) of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 63:403-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne, E. P., B. Wing, D. Coleman, and T. Shenk. 2001. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J. Virol. 75:12319-12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bzik, D. J., C. Debroy, B. A. Fox, N. E. Pederson, and S. Person. 1986. The nucleotide sequence of the gB glycoprotein gene of HSV-2 and comparison with the corresponding gene of HSV-1. Virology 155:322-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai, W. H., B. Gu, and S. Person. 1988. Role of glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus type 1 in viral entry and cell fusion. J. Virol. 62:2596-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson, C., W. J. Britt, and T. Compton. 1997. Expression, purification, and characterization of a soluble form of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B. Virology 239:198-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, C. P., D. H. Vesole, J. Nelson, M. B. Oldstone, and M. F. Stinski. 1989. Identification and expression of a human cytomegalovirus early glycoprotein. J. Virol. 63:3330-3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compton, T., R. R. Nepomuceno, and D. M. Nowlin. 1992. Human cytomegalovirus penetrates host cells by pH-independent fusion at the cell surface. Virology 191:387-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compton, T., D. M. Nowlin, and N. R. Cooper. 1993. Initiation of human cytomegalovirus infection requires initial interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate. Virology 193:834-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cranage, M. P., T. Kouzarides, A. T. Bankier, S. Satchwell, K. Weston, P. Tomlinson, B. Barrell, H. Hart, S. E. Bell, A. C. Minson, et al. 1986. Identification of the human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B gene and induction of neutralizing antibodies via its expression in recombinant vaccinia virus. EMBO J. 5:3057-3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer, D., C. Barret, K. Bryson, A. Elofsson, A. Godzik, D. Jones, K. J. Karplus, L. A. Kelley, R. M. MacCallum, K. Pawowski, B. Rost, L. Rychlewski, and M. Sternberg. 1999. CAFASP-1: critical assessment of fully automated structure prediction methods, p. 209-217. In Proceedings of the 3rd meeting on the Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction. Wiley, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Graham, F. L., and A. J. van der Eb. 1973. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology 54:536-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gretch, D. R., B. Kari, L. Rasmussen, R. C. Gehrz, and M. F. Stinski. 1988. Identification and characterization of three distinct families of glycoprotein complexes in the envelopes of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 62:875-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber, M. T., and T. Compton. 1997. Characterization of a novel third member of the human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein H-glycoprotein L complex. J. Virol. 71:5391-5398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kari, B., and R. Gehrz. 1993. Structure, composition and heparin binding properties of a human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein complex designated gC-II. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Pt. 2):255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kari, B., Y. N. Liu, R. Goertz, N. Lussenhop, M. F. Stinski, and R. Gehrz. 1990. Structure and composition of a family of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein complexes designated gC-I (gB). J. Gen. Virol. 71(Pt. 11):2673-2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley, L. A., R. M. MacCallum, and M. Sternberg. 1999. Recognition of remote protein homologies using three-dimensional information to generate a position specific scoring matrix in the program 3D-PSSM. The Association for Computing Machinery, New York, N.Y.

- 21.Laquerre, S., S. Person, and J. C. Glorioso. 1996. Glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus type 1 oligomerizes through the intermolecular interaction of a 28-amino-acid domain. J. Virol. 70:1640-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonard, C. K., M. W. Spellman, L. Riddle, R. J. Harris, J. N. Thomas, and T. J. Gregory. 1990. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10373-10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long, D., W. C. Wilcox, W. R. Abrams, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1992. Disulfide bond structure of glycoprotein D of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. J. Virol. 66:6668-6685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maerz, A. L., H. E. Drummer, K. A. Wilson, and P. Poumbourios. 2001. Functional analysis of the disulfide-bonded loop/chain reversal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 reveals a critical role in gp120-gp41 association. J. Virol. 75:6635-6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milne, R. S., D. A. Paterson, and J. C. Booth. 1998. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein H/glycoprotein L complex modulates fusion-from-without. J. Gen. Virol. 79(Pt. 4):855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norais, N., D. Tang, S. Kaur, S. H. Chamberlain, F. R. Masiarz, R. L. Burke, and F. Marcus. 1996. Disulfide bonds of herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein gB. J. Virol. 70:7379-7387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmen, K. A., J. Singh, B. G. Luukkonen, M. Lopper, A. Bittner, N. E. Miller, M. R. Jackson, T. Compton, and K. Fruh. 2001. Global modulation of cellular transcription by human cytomegalovirus is initiated by viral glycoprotein B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7140-7145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh, J., and T. Compton. 2000. Characterization of a panel of insertion mutants in human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 74:1383-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu, H., J. P. Cong, and T. Shenk. 1997. Use of differential display analysis to assess the effect of human cytomegalovirus infection on the accumulation of cellular RNAs: induction of interferon-responsive RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13985-13990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]