Abstract

RNA aptamers derived by SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) and specific for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) bind at the template-primer cleft with high affinity and inhibit its activity. In order to determine the potential of such template analog RT inhibitors (TRTIs) to inhibit HIV-1 replication, 10 aptamers were expressed with flanking, self-cleaving ribozymes to generate aptamer RNA transcripts with minimal flanking sequences. From these, six aptamers (70.8,13, 70.15, 80.55,65, 70.28, 70.28t34, and 1.1) were selected based on binding constants (Kd) and the degree of inhibition of RT in vitro (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]). These six aptamers were each stably expressed in 293T cells followed by transfection of a molecular clone of HIVR3B. Analysis of the virion particles revealed that the aptamers were encapsidated into the virions released and that the packaging of the viral genomic RNA or the cognate primer, tRNA3Lys, was apparently unaffected. Infectivity of virions produced from 293T cell lines expressing the aptamers, as measured by infecting LuSIV reporter cells, was reduced by 90 to 99.5% compared to virions released from cells not expressing any aptamers. PCR analysis of newly made viral DNA upon infection with virions containing any of the three aptamers with the strongest binding affinities (70.8,13, 70.15, and 80.55,65) showed that all three were able to form the minus-strand strong-stop DNA. However, virions with the aptamers 70.8 and 70.15 were defective for first-strand transfer, suggesting an early block in viral reverse transcription. Jurkat T cells expressing each of the three aptamers, when infected with HIVR3B, completely blocked the spread of HIV in culture. We found that the replication of nucleoside analog RT inhibitor-, nonnucleoside analog RT inhibitor-, and protease inhibitor-resistant viruses was strongly suppressed by the three aptamers. In addition, some of the HIV subtypes were severely inhibited (subtypes A, B, D, E, and F), while others were either moderately inhibited (subtypes C and O) or were naturally resistant to inhibition (chimeric A/D subtype). As virion-encapsidated TRTIs can predispose virions for inhibition immediately upon entry, they should prove to be efficacious agents in gene therapy approaches for AIDS.

Inhibitors that target human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) used in current highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens can block viral replication and retard the onset of AIDS. However, toxicity (4) and the rapid appearance of drug-resistant viral strains (24) are serious concerns and diminish their merit. Current anti-RT drugs have exploited the presence of two binding pockets on this viral DNA polymerase. The nucleoside analog RT inhibitors (NRTI) bind to the deoxynucleoside triphosphate-binding pocket, which is formed partly by the template-primer nucleic acid and partly by the protein surfaces (29). The other site, the nonnucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI)-binding pocket, is a hydrophobic pocket exclusively present in the RT of the M subgroup of HIV-1 (29). A key surface on the RT, the template-primer-binding cleft, in spite of its central importance in viral reverse transcription, has been minimally explored as a target to obstruct viral replication.

Small nucleic acid aptamers with high affinity for HIV-1 RT were previously isolated in vitro from a library of randomized DNA and RNA sequences via the SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) procedure (5, 9, 26, 30, 31). The anti-RT aptamers are small RNA molecules that lack primary sequence homology to each other, display high affinity and specificity for HIV-1 RT, and competitively inhibit its enzymatic activity in vitro. Thus, their three-dimensional structures all recognize the same surface on the RT, the template-primer-binding cleft. Some of the anti-HIV-1 RT aptamers have the potential to form pseudoknot-like secondary structures, often with a sharp bend reminiscent of the conformation of template-primer bound to HIV-1 RT (5). The crystal structure of HIV-1 RT bound to one of the RNA aptamers shows that the aptamer makes extensive contacts with the template-primer cleft of RT (12). It has been shown that the association constant of such aptamers for HIV-1 RT correlates with the degree of inhibition. Thus, these aptamers are termed here template analog RT inhibitors (TRTIs).

Despite the unique nature of the anti-HIV-1 RT RNA aptamers, their utility as inhibitors of viral replication has remained unexploited till now. Therefore, we examined their suitability for intracellular expression via gene delivery and their ability to block HIV replication. In this report, we show that such aptamers efficaciously block HIV-1 replication in cell culture. The aptamers block an early stage of the viral life cycle: they inhibit drug-resistant viruses as well a several subtypes of HIV-1. Furthermore, we report that even under potent onslaught, such as a high ratio of virions to cells, HIV could be effectively blocked by the intracellularly expressed TRTI aptamers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Anti-RT aptamers.

The anti-HIV-1 RT aptamers used for this study were selected from those described by Tuerk and Gold (30) and Burke et al. (5) and include 1.1, 70.8,13, 70.12,16, 70.15, 70.24,67, 70.28, 70.28t34, 80.10, 80.18, and 80.55,65.

The construction of the aptamer cassette (Fig. 1) with the flanking ribozymes was essentially as described by Benedict et al. (2) except that EcoRI and ApaI restriction sites were present between the two ribozymes placed under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter within the vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Double-stranded adapters encoding different aptamer sequences were inserted via ligation between the EcoRI and ApaI sites.

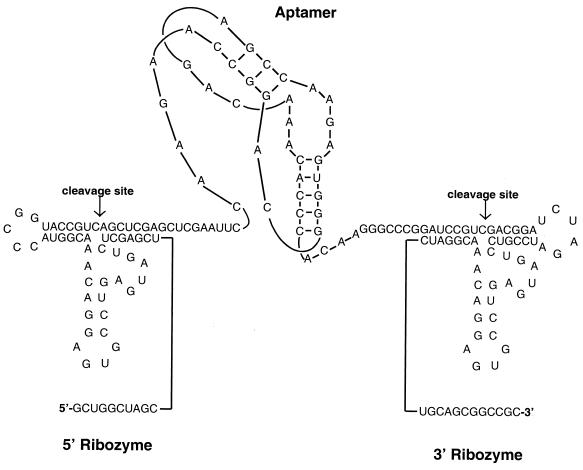

FIG. 1.

Expression of anti-HIV-1 RT aptamer pseudoknots with minimal flanking sequences. A schematic diagram of a representative anti-RT aptamer, 70.28, flanked by self-cleaving ribozymes is presented. The aptamer is represented as a pseudoknot to reflect the secondary structure proposed by Burke et al. (5). The ribozyme sequences are positioned to cleave the required sites according to Benedict et al. (2).

In vitro binding.

RNA aptamers for RT-binding studies were generated by in vitro transcription using T3 RNA polymerase. The T3 promoter was linked to each of the ribozyme-aptamer-ribozyme sequences via PCR by using the upstream primer T3-Start, 5′AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGTAGACAATTCACTGC3′, and the downstream primer pcDNA3.1END, 5′GCATGCCTGCTATTGTCTTCCC3′. PCR products generated by using each ribozyme-aptamer-ribozyme construct served as the templates for in vitro transcription with the Ambion (Austin, Tex.) MEGAshortscript kit. The transcripts were radiolabeled internally with [α-32P]UTP, and the reaction products were resolved on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Radiolabeled, processed RNA aptamers were gel purified and eluted in solution containing 500 mM ammonium acetate (NH4OAc), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). RNA was then treated with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed by incubating 10 fmol of purified RNA aptamer with increasing amounts of purified HIV-1 RT at 25°C in 10 μl of buffer containing 50 mM KCl, 25 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 300 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) per ml. The reaction products were electrophoresed on native polyacrylamide gels. Dried gels were exposed to a phosphorimager screen, and Kd was calculated by using ImageQuant software. To determine binding strengths, the percentage of band shift observed with increasing concentrations of RT (1 to 500 nM) with respect to the no-protein control lane was first determined. The Kd values were determined by fitting data from three independent experiments to a dose-response curve by using nonlinear regression (6) (GraphPad Software Inc.).

In vitro RT inhibition.

To determine the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s), self-cleaved RNA aptamers were gel purified and eluted in 500 mM NH4OAc-1 mM EDTA-0.2% SDS. RNA was then treated with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated. RT reaction mixtures (50 μl) contained 80 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 6 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mg of BSA per ml, 10 μM [α-32P]dTTP, 25 μM concentrations of each of the remaining three deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and a range of concentrations of RNA aptamers (1 to 1,000 nM). Mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 25 ng of purified HIV-1 RT, and at the end of the reaction, aliquots were spotted onto DE81 filter paper and washed with 2× SSC (30 mM sodium citrate, 300 mM NaCl [pH 7.0]). Dried filters were then counted, and individual IC50s were determined by fitting results to a dose-response curve by using nonlinear regression (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Cells and viruses.

Drug-resistant HIV isolates and different subtypes of HIV-1 were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The drug resistance of each of these viruses is listed below (NIH reagent program catalog numbers for the strains are in parentheses): zidovudine (AZT) resistant (2529), with the mutations L74V, M41L, V106A, and T215Y; lamivudine (3TC) resistant (2970), with M184V; dideoxyinosine (ddI) and dideoxycytosine (ddC) resistant (2528), with L74V; nevirapine and TIBO {tetrahydroimidazo[4,5,1-jk][1,4]-benzodiazepin-2-(1H)-one and -thione} resistant (1413), with K103N and Y181C; and protease inhibitor (PI) resistant (resistant to multiple anti-HIV protease drugs; 2840), carrying L10R, M46I, L63P, V82T, and I84V.

Viral titers were determined by p24 assay and multiplicity of infection (MOI) calculated using P4 cells. Aptamer-expressing Jurkat cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 and viral kinetics monitored by p24 antigen measurements over a period of 18 to 20 days. The p24 measurements were via antigen capture assay using a commercial p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (NEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

To generate clonal cell lines stably expressing each of the aptamer RNAs, purified plasmid DNA was transfected into 293T and Jurkat cells by using the GenePorter reagent (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, Calif.). Stable ribozyme-aptamer cell lines were selected using 500 μg of G418 (Invitrogen) per ml. For 293T cells, multiple G418-resistant colonies were separately expanded and expression of the respective aptamer RNA was confirmed by RNase protection assay (RPA). For Jurkat T cells, 12 h after the start of drug selection, cells were cloned by dilution, single cell clones were expanded, and the expression of aptamer RNA was confirmed.

RPA.

We examined the cytoplasmic RNA of 293T cells expressing various aptamers by RPA. RPA analysis was performed by using the RPA III kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cytoplasmic RNA was extracted from aptamer-expressing 293T cells by Trizol (Invitrogen). In vitro transcripts corresponding to the aptamer sequences were generated by T3 RNA polymerase. The aptamer sequences were flanked by sequences unrelated to those present in the ribozyme constructs. Each protection assay was performed on equal amounts of cytoplasmic RNA (10 μg) with 4 × 104 cpm of the corresponding antisense aptamer probe internally labeled with [α-32P]UTP. Reaction mixtures were heated to 95°C for 5 min and then incubated overnight at 42°C. Digestion of the single-stranded sequences was carried out with a mixture of RNase T1 and RNase A for 30 min at 37°C. Protected fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis through an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and were quantified directly with a phosphorimager. Each sample was also probed with an antisense probe to human β-actin (Ambion).

Western blot analysis.

Virion particles released from aptamer-expressing 293T cells were collected from filtered supernatants and were concentrated by centrifugation through a 25% sucrose cushion in Tris-NaCl-EDTA at 4°C for 2 h at 23,000 rpm (Beckman SW55 Ti rotor). Pelleted virus was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline for RNA extraction for dot blot analysis or in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM KCl, 0.025% Triton X-100, and 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate for Western blot analysis. For this, the virus sample was boiled for 5 min and run on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel. Viral proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and the Western blot was probed with anti-HIV-1 immunoglobulin G (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program).

Dot blot analysis.

RNA was extracted from purified virus particles with Trizol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was blotted on to Hybond nylon membranes (Amersham) and probed for viral genomic RNA, aptamer RNA, and tRNA3Lys with antisense oligonucleotide probes. The aptamer probe consisted of a pool of six different oligonucleotides. The oligonucleotides were end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by using polynucleotide kinase and hybridized to the target RNA in Ultrahyb buffer as suggested by the manufacturer (Ambion).

Measuring infectivity and replication capacity of HIV.

Reporter cell lines with lentiviral tat-driven expression of luciferase (CEM-LuSIV cells) (25) or β-galactosidase (P4-HeLa cells) (7) were used to quantitate viral infectivity. Equal inputs of virus (10 ng of p24) were used to infect CEM-LuSIV cells, and 24 h later, the cell lysate was assayed for luciferase activity (Promega, Madison, Wis.), which was measured with a luminometer. The output was expressed as relative light units (RLU). Virus equivalent to 25 ng of p24 was used to infect P4-HeLa cells, and 36 h postinfection, the cells were fixed in 0.1% glutaraldehyde and stained with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). P4-HeLa cells were used to calculate the MOI.

Wild-type HIV-1 was generated by transfecting a replication-competent and infectious molecular clone of HIV-1R3B into 293T cells. The supernatant was assayed for virus, and MOI was tested on P4-HeLa cells. Aptamer-expressing Jurkat cell lines were infected at an MOI of 0.1, and viral kinetics was monitored by p24 antigen production.

RESULTS

Design of aptamer expression system.

Although both DNA and RNA aptamers have been described (5, 26, 30), the RNA aptamers are advantageous since they can be introduced into cells via gene therapy-based approaches. A large number of RNA aptamers have been isolated, but their utility for blocking HIV replication is untested. We surmised that RNA aptamers with the strongest affinity to RT in vitro would also efficiently inhibit HIV replication. On the basis of their relative capacity for binding to RT, we selected 10 aptamer sequences from those described by Tuerk and Gold (30) and Burke et al. (5).

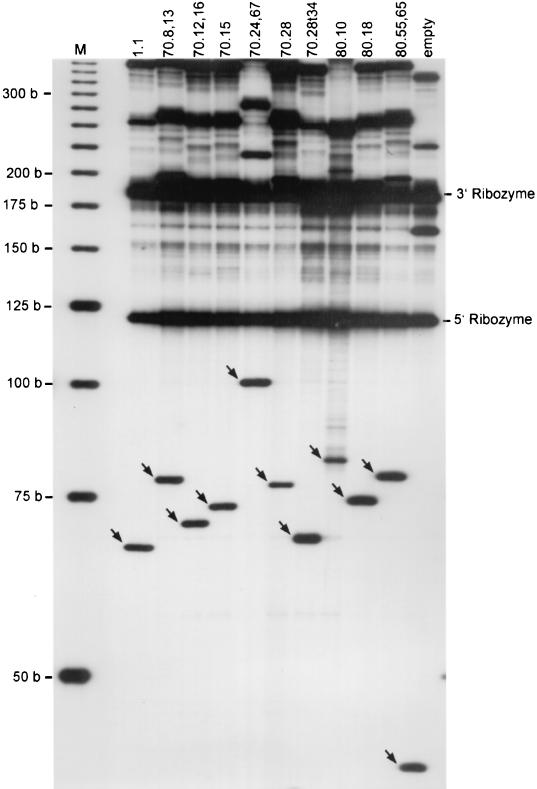

As the selectivity of RNA aptamers is directly related to their three-dimensional structure, unrelated flanking sequences are likely to interfere with proper folding and need to be minimized. Therefore, we created an expression vector in which the aptamer sequence was flanked by self-cleaving ribozymes (Fig. 1). The ribozymes were designed to recognize the GUC cleavage motifs that were present in the primary transcript immediately bordering the aptamer sequence. Upon cleavage by the ribozymes, the aptamer RNA would be released. The in vitro transcripts of the selected aptamers were analyzed on a polyacrylamide gel. Efficient processing of the ribozymes (>50% fully processed for all aptamers) was observed in each case, releasing the aptamer RNA and the 5′ and the 3′ ribozyme fragments (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Autocatalytic processing of the ribozyme-aptamer-ribozyme transcripts in vitro. Denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis shows the products of T3 RNA polymerase-mediated in vitro transcription of ribozyme-aptamer-ribozyme constructs. The 5′ and 3′ flanking ribozyme fragments (118 and 193 nucleotides, respectively) released by self-cleavage are indicated. The sizes of the liberated aptamer fragments range from 66 to 101 nucleotides (arrows). The empty vector releases a 44-nucleotide fragment containing just the flanking ribozymes and the linker sequence containing the restriction sites (rightmost lane).

Identifying the most potent RT aptamers.

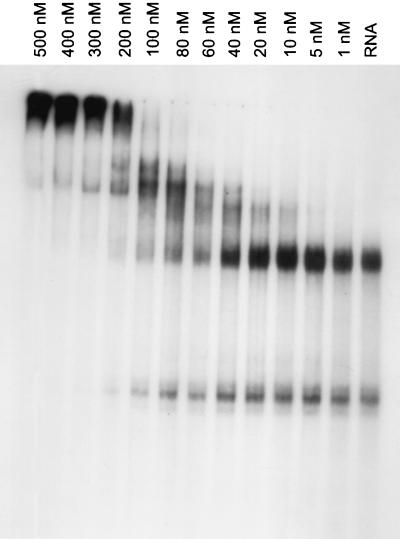

We hypothesized that the strongest-binding aptamer would also be the most potent inhibitor of HIV replication. Therefore, the ability of each of the 10 selected RNA aptamers to bind recombinant purified HIV-1 RT was evaluated in vitro via EMSA, and the dissociation constants were determined for each individual aptamer in its processed form. In vitro transcription of the primary transcripts with T3 RNA polymerase was followed by gel purification of the processed aptamers. The aptamer RNAs were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified recombinant HIV-1 RT, the products were resolved on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 3), and Kd values were calculated based on the degree of band shift caused by the formation of RNA-protein complexes (see Materials and Methods). The binding affinities ranged from 27 to 2,001 nM (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

EMSAs to determine binding affinities. A native polyacrylamide gel showing electrophoretic mobility shift of the radiolabeled RNA aptamer 80.55,65 upon binding to increasing concentrations of purified, recombinant HIV-1 RT (1 to 500 nM) is presented. The bands that represent free RNA can be seen in the lane marked “RNA,” which represents the aptamer incubated in the absence of RT. All bands above the major band in lane RNA represent those complexed with HIV-1 RT.

TABLE 1.

Dissociation constants (Kd) of various aptamers for interaction with HIV-1 RT and their ability to inhibit RT activity in vitro (IC50)

| RNA aptamer | Kd (nM) | IC50 (nM) | Length (nt)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70.8,13 | 27 | 89 | 78 |

| 70.15 | 63 | 159 | 73 |

| 80.55,65 | 129 | 143 | 79 |

| 70.12,16 | 184 | 210 | 71 |

| 70.28 | 201 | 254 | 77 |

| 80.10 | 180 | 309 | 89 |

| 70.28t34 | 219 | 327 | 67 |

| 80.18 | 197 | 334 | 74 |

| 1.1 | 270 | 607 | 65 |

| 70.24,67 | 2,001 | >1,000 | 101 |

Includes short, 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences of 12 and 11 nucleotides (nt), respectively.

Next, the ability of each of the 10 selected RNA aptamers to inhibit recombinant purified HIV-1 RT was evaluated in vitro, and the degree of inhibition (IC50) by each aptamer was determined. In vitro transcription of the primary transcripts with T3 RNA polymerase was followed by gel purification of the processed aptamers. IC50s ranged from 89 to >1,000 nM (Table 1). Six RNA aptamers were selected for further study, to test their effectiveness in inhibiting HIV-1 replication. Of these, 70.8, 70.15, and 80.55 were the best binders (with Kd values of 27, 63, and 129 nM, respectively) (Table 1). Furthermore, these three aptamers were also the best inhibitors of HIV-1 RT in our in vitro assays, displaying IC50s of 89, 143, and 159 nM, respectively (Table 1). The other three aptamers, 70.28 (254 nM), 70.28t34 (327 nM), and 1.1 (607 nM), were selected because they were previously shown by other laboratories to have a high specificity and tight binding to HIV-1 RT (5, 14).

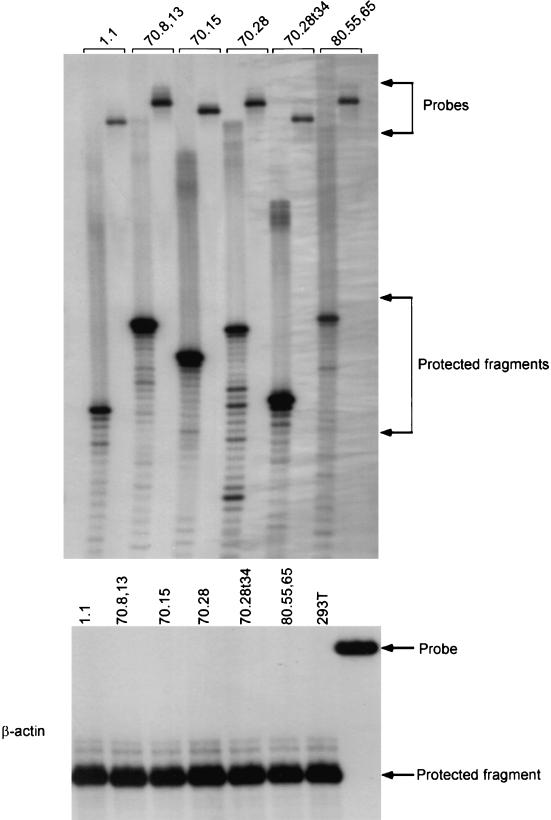

Intracellular levels of aptamers.

In order to ensure that the aptamer transcripts are expressed at significant levels within the 293T transfectants, we isolated cytoplasmic RNA from each of the six cell lines, and RPAs were performed. The intensity of the protected fragment corresponds to the cytoplasmic level of the respective aptamer RNA (sum of the processed and unprocessed forms). As a control for loading, we also probed the same RNA preparations for the level of transcripts of the housekeeping β-actin gene, and these results are shown in Fig. 4. When the protected fragments for each aptamer were quantitated as percentages of the level of actin transcripts for the respective cell line, the aptamers were found to be at 7, 34, 22, 7.7, 34, and 5.6%, respectively, for the aptamers 1.1, 70.8,13, 70.15, 70.28, 70.28t34, and 80.55,65. Thus, variations in the level of expression of these aptamers are within sixfold.

FIG. 4.

RNase protection analysis to quantitate aptamer RNA levels in 293T cell lines. Denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis shows the protected RNA fragments corresponding to each of the six aptamer RNAs in the cytoplasm of the respective cells. As an internal control, cytoplasmic RNAs were also probed for the levels of human β-actin mRNA.

Effect of aptamers on the assembly and production of HIV.

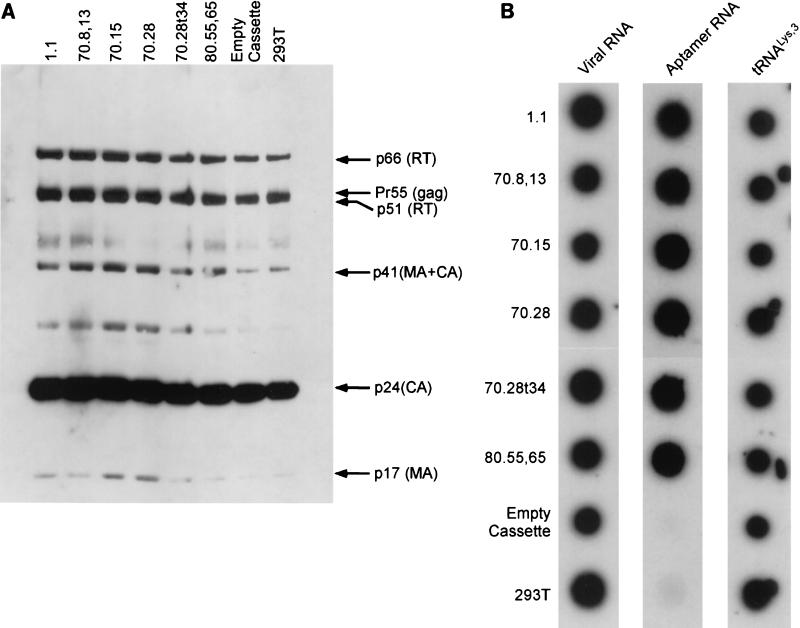

In order to assess the effect of these aptamers on viral replication, 293T cell lines stably expressing each ribozyme-aptamer were transfected with an infectious molecular clone of HIV-1R3B, and the virus was harvested 36 h posttransfection. Quantitation of the virus released via measurement of p24 released revealed that there were no significant differences in the amount of virus produced between parental 293T cells and cells expressing aptamers. Immunoblot analysis of viral proteins in the medium indicated that there was no noticeable difference between the viral proteins from the aptamer-expressing cell lines and the controls (Fig. 5A), indicating that the assembly and maturation of the virus particles were not affected. These results reveal that the presence of the aptamer in the producer cells does not interfere with virus production or maturation.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of virion proteins and of RNAs encapsidated by virions. (A) Virion proteins were extracted from all the viruses in this study, resolved on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing a 4-to-20% gradient of polyacrylamide, and immunoblotted with anti-HIV antiserum (human HIV immunoglobulin). (B) Dot blot hybridizations of virus particles harvested from aptamer-expressing 293T cells. Total RNA from purified virions spotted on nitrocellulose was hybridized to oligonucleotide probes specific for viral genomic RNA, aptamer RNA, and  . “Empty cassette” and “293T” correspond to virus released from cells expressing the empty, dual ribozyme transcript and that produced in plain 293T cells.

. “Empty cassette” and “293T” correspond to virus released from cells expressing the empty, dual ribozyme transcript and that produced in plain 293T cells.

Since the TRTI aptamers were identified as molecules capable of tightly binding to mature HIV-1 RT, we surmised that they could be packaged in the virions. However, the ability of aptamers to bind to RT in its unprocessed precursor form, the Gag-Pol polyprotein, had not been demonstrated. We tested whether the aptamers are packaged into the virions via their ability to bind to Gag-Pol polyprotein. Purified virions were obtained from culture supernatants of aptamer-expressing cell lines by density gradient centrifugation. Viral pellets were lysed, and total RNA was extracted. Dot blots of the total RNA were probed with antisense-labeled oligonucleotides to confirm the presence of the aptamers. In every case tested, the aptamer was detected in the mature viral particles, indicating that aptamers are indeed able to bind to Gag-Pol (Fig. 5B).

It is known that the HIV virions specifically encapsidate tRNA3Lys and that one of the determinants of this specificity is the RT within Gag-Pol polyprotein (20). Therefore, we wondered if the binding of aptamers to the RT portion of Gag-Pol precludes the encapsidation of tRNA3Lys . Our dot blot hybridizations reveal that along with the viral RNA, the cognate tRNA3Lys primer was also present in the virions, suggesting that packaging of aptamers does not preclude the packaging of tRNA (Fig. 5B).

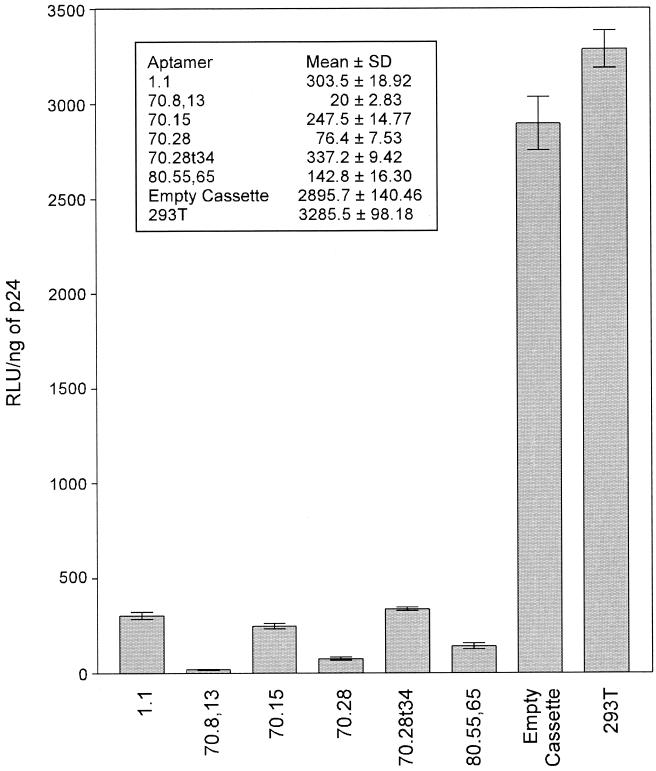

Aptamers inhibit HIV infectivity via an early block to reverse transcription.

The infectivity of the virus particles released from aptamer-expressing cells was assayed with the indicator cell line CEM-LuSIV (25), containing the luciferase reporter gene, which is responsive to Tat protein. Virus particles obtained from all cells expressing the aptamers displayed a dramatic reduction in infectivity that ranged from 90 to 99% compared with the control virus harvested from the parental 293T cells (Fig. 6). Of all the aptamers tested, aptamer 70.8, which was the strongest RT inhibitor in vitro (IC50, 89 nM), displayed the most dramatic reduction in infectivity (99%) (Fig. 6). Results obtained with an alternate indicator cell line, HeLa-P4, were comparable to those obtained with LuSIV cells (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Infectivity of virions produced in cells expressing different aptamers. Infectivity of virus harvested following transfection with a molecular clone of HIV into 293T cell lines stably expressing each of the six aptamers was determined by infection of LuSIV cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means of three independent determinations and standard deviations. The inset shows the mean RLU ± standard deviations.

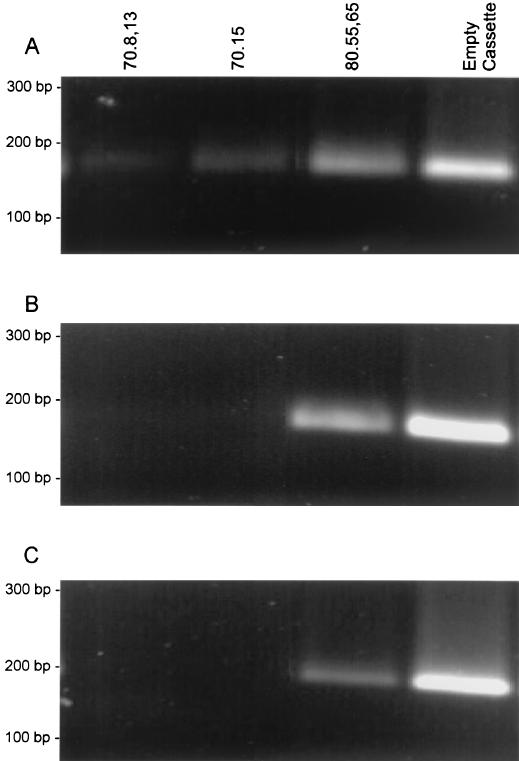

In order to delineate the stage of the virus life cycle at which the aptamers exert their inhibitory influence in Jurkat cells, we selected three aptamers, 70.8,13, 70.15, and 80.55,65, which showed the strongest inhibition in vitro (IC50s, 89, 143, and 159 nM, respectively). The virion particles were harvested from 293T cells expressing each of these aptamers. Jurkat T cells were infected with virions, and total genomic DNA was extracted 12 h postinfection and subjected to reverse transcription stage-specific PCR to determine the extent of reverse transcription at three key steps in viral reverse transcription (34) (Fig. 7). Our results indicate that synthesis of the earliest intermediate, minus-strand strong-stop DNA synthesis, was unaffected by the presence of any of the six aptamers in the virus (Fig. 7A). However, continued viral DNA synthesis, as assessed by minus-strand transfer product (Fig. 7B) and the formation of completed proviral DNA (Fig. 7C), was not evident for virions produced in the presence of the aptamers 70.8,13 and 70.15, suggesting that in these two cases, the aptamer blocks reverse transcription in its early stages. Even though the other promising aptamer, 80.55,65, appeared to not completely prevent synthesis of proviral DNA, our data reproducibly show a considerable reduction in the level of DNA synthesized (Fig. 7C, lane 3).

FIG. 7.

Analysis of the proviral DNA synthesis in Jurkat cells. Agarose gels showing the products of PCR using reverse transcription stage-specific primers with infected Jurkat T-cell DNA as the template. Primers were specific for minus-strand strong-stop DNA (R-U5) (A), an intermediate formed after the minus-strand transfer (U3-R) (B), and full-length proviral DNA (R-gag) (C).

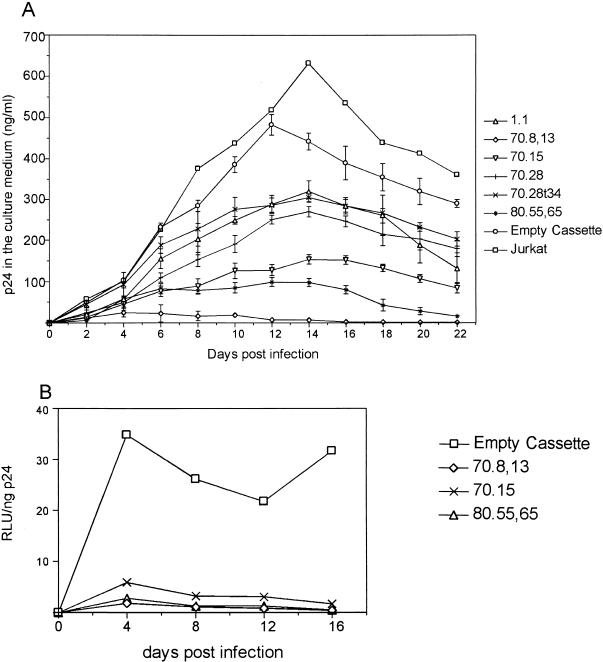

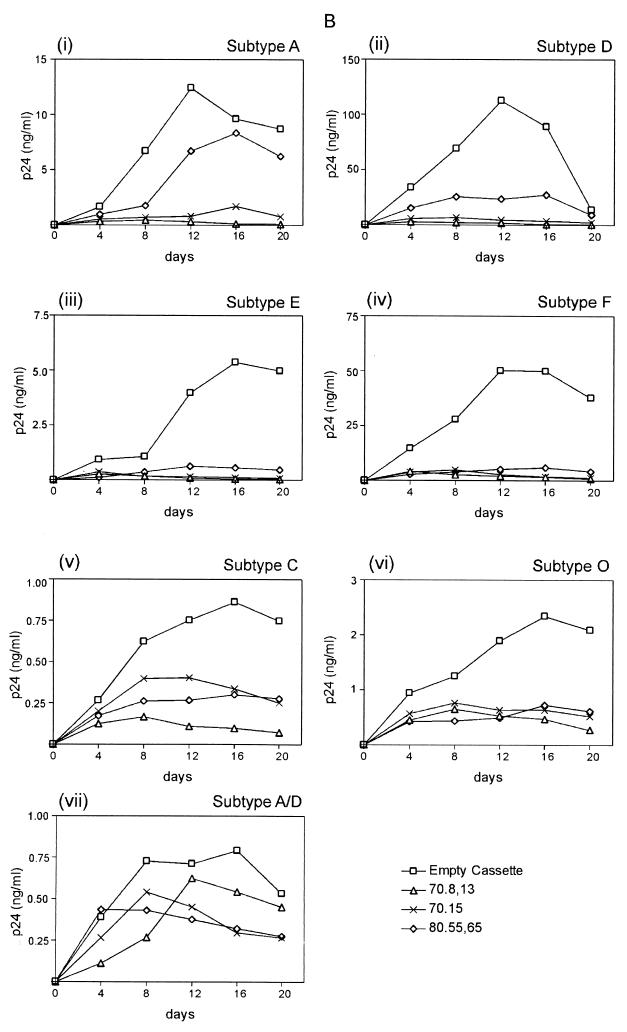

Anti-RT aptamers limit the spread of virus in cultured T cells.

In order to estimate the potential of the aptamers to suppress successive virus replication cycles, stable Jurkat cell lines expressing each of the six aptamers were generated. These stable cell lines were infected with wild-type HIV-1R3B at a low MOI (0.1). Spread of the virus in the culture was then monitored by measuring p24 in the culture supernatants. In each case, the aptamers exerted a significant influence on the dynamics of viral replication and the propagation of infectious virus was severely compromised in stable cell lines expressing the aptamers 70.8,13, 70.15, and 80.55 (Fig. 8A). While peak p24 production in the absence of the aptamers was observed at day 14, there was a range of levels of inhibition in the presence of various aptamers. The most dramatic inhibitory effect was observed in the case of aptamer 70.8,13, where virus production was minimal from the onset of infection (Fig. 8A). In fact, for this aptamer, virtually no detectable p24 was present in the culture supernatant for up to 22 days. In order to ensure that the differences between different virus growth curves (in the absence of aptamer and the presence of different aptamers) are significant, we performed Student's t test for p24 values for day 14 (which represents the peak virus production for plain Jurkat cells). In a repeated-measures test, for all the cultures in parallel, this yielded a P value of <0.0001. When paired tests were performed between the “empty cassette” and viruses growing in the presence of each aptamer, for the same time point, all P values obtained were <0.0017, showing that the differences are significant.

FIG. 8.

Replication kinetics of HIV-1 in Jurkat cells expressing RNA aptamers. (A) Patterns of inhibition of HIV-1 replication in Jurkat cells expressing various RNA aptamers. Subsequent to infection at an MOI of 0.1, Jurkat cell lines expressing each of the six aptamers, the parental Jurkat cell line, and the control cell line (empty cassette) were maintained for 22 days. The data for Jurkat cell lines expressing each of the aptamers and the control cell line are averages for three independently derived cell lines. HIV in the culture medium was monitored via p24 determination every 2 days. (B) Infection of Jurkat T cell lines expressing the three best aptamers at a high MOI. The Jurkat cell lines expressing the empty cassette and the aptamers 70.8, 70.15, and 80.55,65 were infected with 50 MOI of HIV. The infectivity of the virus in the medium was measured by RLU on LuSIV indicator cells.

For such dramatic results to be effective in HIV-infected individuals, the aptamers should be able to thwart infection by levels of input virus much higher than those tested here. Therefore, Jurkat cells expressing the aptamers 70.8,13, 70.15, and 80.55,65 were challenged with HIV-1R3B at an MOI of 50. Cells were cultured for 16 days, and the virus output and its infectivity were measured via p24 antigen capture and LuSIV reporter assays, respectively, at regular intervals of 4 days. When the ratio of infectivity to particle (RLU per nanogram of p24) was measured for virus released from each of the aptamer-expressing Jurkat cells, it appeared that the infectivity of the viruses in the supernatant was severely reduced in comparison with that in parental Jurkat cells (Fig. 8B).

RT aptamers are effective against drug-resistant variants and other HIV subtypes.

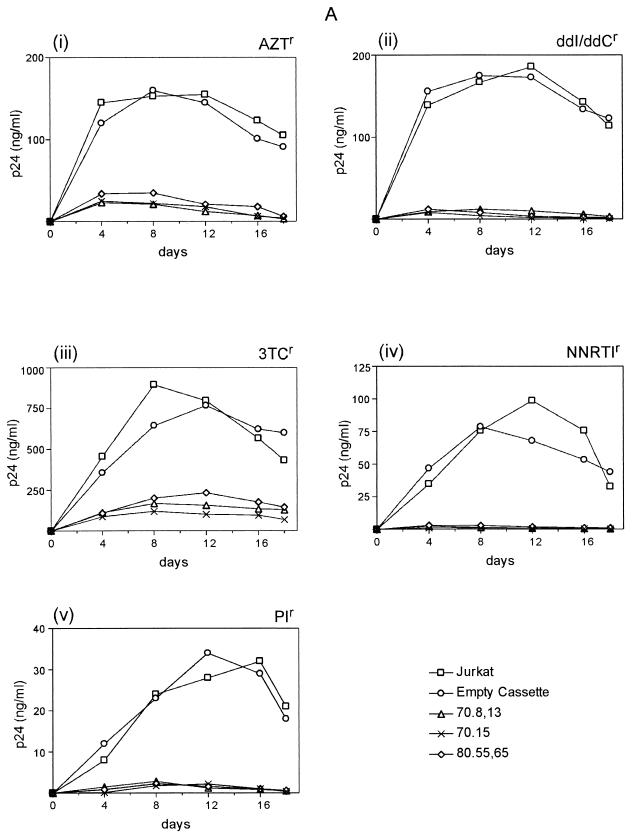

In order for the TRTI aptamers, a new class of HIV inhibitors, to be useful to a wider segment of the global population, they should be effective against a broad spectrum of HIV-1 variants, including variants resistant to antiretrovirals, as well as various subtypes of HIV-1. Therefore, cell lines expressing the aptamers 70.8,13, 70.15, and 80.55,65 were infected with different drug-resistant viruses. For each drug-resistant isolate, the aptamers demonstrated drastic inhibition of viral replication, with 70.8 being consistently the most potent (Fig. 9A). It should be noted that the NNRTI-resistant viruses were most potently inhibited, followed by ddI- and ddC-resistant and PI-resistant HIV isolates. Thus, the aptamers are effective against variants that can no longer be inhibited by a variety of potent antiretrovirals.

FIG. 9.

Ability of TRTI aptamers to inhibit drug-resistant variants and multiple subtypes of HIV. (A) Inhibition of drug-resistant isolates of HIV. Jurkat cell lines expressing the RNA aptamers 70.8, 70.15, and 80.55 were infected with HIV-1 strains having the indicated drug resistance at an MOI of 0.1. (B) Inhibition of different HIV subtypes by RNA aptamers. The same three cell lines were infected with HIV isolates of the indicated subtypes at an MOI of 0.1. Viral spread in both cases was monitored by p24 antigen capture assay.

In a similar experiment, seven different subtypes of HIV-1 were used to infect the three strongest aptamer-expressing Jurkat clones, and their replication was monitored via measurement of p24 in the culture supernatants. The three aptamers most strongly inhibiting subtype B HIV-1 displayed a range of effects that could be broadly divided in two. One group of viruses, comprising subtypes A, D, E, and F, were inhibited to a high degree, similar to subtype B. Subtypes C and O and the chimeric HIV-1 subtype A/D were moderately or poorly inhibited (Fig. 9B). While these results show that the nature of the pocket that accommodates the aptamer and the template-primer pocket is variable among the subtypes of group M HIVs tested, they clearly demonstrate the potency of the aptamers across a wide spectrum of viral strains and subtypes (Fig. 9B).

DISCUSSION

Although a large number of nucleic acid-based anti-HIV inhibitors have been developed (15, 17, 21, 27, 28), only a few target RT. These include inhibitors that compete with the template-primer (8, 18, 32), those that block RT function by irreversibly annealing to template primer (16), and those developed by SELEX to specifically bind to HIV-1 RT (5, 26, 30). While the HIV-1 RT-specific RNA aptamers are known to bind RT (14) strongly, their ability to inhibit HIV replication is untested so far. In this report, we have demonstrated the inhibitory capacity of such RNA aptamers when produced in T cells. Analysis of the reverse transcription in HIV-1-infected cells revealed that at least for two of the three best inhibitors, the block in viral kinetics was at an early stage of reverse transcription and the presence of the aptamer prevented the successful elongation of the viral genome. It is known that the unprocessed RT (in Gag-Pol polyprotein) in the budding virus actively recruits tRNA3Lys (19). In this report, we demonstrate that it could also sequester the high-affinity RNA aptamer. The high-affinity aptamers exert a strong influence on viral replication, and three of the aptamers severely compromised viral infectivity and the ability of the virus to spread in culture. Furthermore, in the case of the three strongly binding aptamers, there was no emergence of drug-resistant viruses.

The TRTI class of aptamers affords a number of advantages for use as anti-HIV agents. First, the use of SELEX for developing anti-RT molecules led to TRTI aptamers with an unprecedented level of specificity and avidity of binding. Since they inhibit HIV-1 RT competitively and are unlikely to inhibit other viral or cellular proteins, they should have little to no toxicity (5, 26, 30). Second, the expression of aptamers in the infected cell results in encapsidation of the aptamer in the virion particles. Thus, the virions are preloaded with an inhibitor that would block the next replication cycle as soon as DNA synthesis begins. Results of the experiments using a high MOI showed that at the level of expression achieved here, the aptamers were capable of strongly suppressing a 50-to-1 ratio of viruses to cells. Third, the large interacting interface of the aptamer-binding pocket makes the appearance of resistance mutations a significantly low-probability event (11, 30). More than one mutation may be required to prevent binding to such a large surface, thus making it a less likely occurrence than single mutations. Furthermore, mutations in an essential binding pocket such as the template-primer-binding pocket are likely to render the RT unable to bind its normal template, namely, the viral genome. In fact, mutants of HIV-1 RT resistant to DNA aptamers that we isolated in vitro displayed only low levels of resistance with single mutations (10). Furthermore, the mutations led to defective processivity in vitro and, when placed in the context of a molecular clone of HIV, produced replication-defective viruses. Although this optimism is tempered by HIV's success in developing resistance to every approved drug, one remains hopeful that a drug to which HIV will not become resistant will be found.

Intracellular immunization is a powerful approach to inhibiting HIV replication, and it requires the introduction, into susceptible cells, of genes encoding anti-HIV molecules. Thus, the development of gene therapy approaches using hematopoietic stem cell therapy for AIDS patients is an active area in multiple laboratories (1, 3, 13, 23, 33). Use of a therapeutic gene whose product is RNA rather than protein has an added advantage, as it prevents the loss of the delivered gene via immune response. We speculate that when gene therapy approaches for HIV become available, such approaches will be of abundant help (i) in cases of therapy failure due to antiretroviral resistance, (ii) for individuals who will need a “drug holiday” due to complications such as secondary infections, and (iii) for those undergoing structured treatment interruptions.

The extended and efficient intracellular expression of TRTI aptamers via a competent delivery system could lead to powerful alternative drug therapies when combined with the use of enriched hematopoietic stem cells. Prior to their use in humans, hematopoietic stem cell therapy in primates followed by challenge with simian-human chimeric immunodeficiency viruses containing HIV-1 RT can now be attempted (22).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ganjam V. Kalpana, Jürgen Brojatsch, and William Drosopoulos for critically reading the manuscript, T. Fisher and R. Lee for providing purified recombinant HIV-1 RT, and Janice Clements (Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, Md.) for LuSIV indicator cells. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS (DAIDS), NIAID, NIH, as indicated (Reagent Program catalog numbers are shown in parentheses): HIV-1 subtype O from Lutz Gürtler (2878), subtypes A (1650), A/D (1647), C (4165), D (1647), and E (2166) from the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization and DAIDS, subtype F (2329) from Therion Biologics Inc., the AZT-resistant and ddI- and ddC-resistant isolates from Brendan Larder, the 3TC-resistant isolate from John Mellors and Ray Schinazi, the NNRTI-resistant and PI-resistant isolates from Emilio Emini, and HIV immunoglobulin from NABI and NHLBI.

This work was supported by a Public Health Service research grant to V.R.P. (AI30861).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bai, J., J. Rossi, and R. Akkina. 2001. Multivalent anti-CCR ribozymes for stem cell-based HIV type 1 gene therapy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:385-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedict, C. M., W. Pan, S. E. Loy, and G. A. Clawson. 1998. Triple ribozyme-mediated down-regulation of the retinoblastoma gene. Carcinogenesis 19:1223-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridges, S. H., and N. Sarver. 1995. Gene therapy and immune restoration for HIV disease. Lancet 345:427-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkmann, K., A. Smeitink, A. Romijn, and P. Rieiss. 1999. Mitochondrial toxicity induced by nucleoside-analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors is a key factor in the pathogenesis of anti-retroviral therapy-related lipodystrophy. Lancet 354:1112-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke, D. H., L. Scates, K. Andrews, and L. Gold. 1996. Bent pseudoknots and novel RNA inhibitors of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase. J. Mol. Biol. 264:650-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cann, J. R. 1996. Theory and practice of gel electrophoresis of interacting macromolecules. Anal. Biochem. 237:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charneau, P., G. Mirambeau, P. Roux, S. Paulous, H. Buc, and F. Clavel. 1994. HIV-1 reverse transcription: a termination step at the center of the genome. J. Mol. Biol. 241:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirani-Diab, R. E., L. Sarih-Cottin, B. Delord, B. Dumon, S. Moreau, J.-J. Toulme, H. Fleury, and S. Litwak. 1997. Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) primer tRNALys3 are strong inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and arrest viral replication in infected cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2141-2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellington, A. D., and J. W. Szostak. 1990. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346:818-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher, T. S., P. J. Joshi, and V. R. Prasad. 2002. Mutations that confer resistance to template analog inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase lead to severe defects in HIV replication. J. Virol. 76:4068-4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirao, I., M. Spingola, D. Peabody, and A. D. Ellington. 1998. The limits of specificity: an experimental analysis with RNA aptamers to MS2 coat protein variants. Mol. Divers. 4:75-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaeger, J., T. Restle, and T. A. Steitz. 1998. The structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an RNA pseudoknot inhibitor. EMBO J. 17:4535-4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayan, G. C., P. Cordelier, C. Patel, M. BouHamdan, R. P. Johnson, J. Lisziewicz, R. J. Pomerantz, and D. S. Strayer. 2001. SV40-derived vectors provide effective transgene expression and inhibition of HIV-1 using constitutive, conditional, and pol III promoters. Gene Ther. 8:1033-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kensch, O., B. A. Connolly, H. J. Steinhoff, A. McGregor, R. S. Goody, and T. Restle. 2000. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-pseudoknot RNA aptamer interaction has a binding affinity in the low picomolar range coupled with high specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18271-18278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konopka, K., N. Duzgunes, J. Rossi, and N. S. Lee. 1998. Receptor ligand-facilitated cationic liposome delivery of anti-HIV-1 Rev binding aptamer and ribozyme DNAs. J. Drug Target. 5:247-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, R., N. Kaushik, M. J. Modak, R. Vinayak, and V. N. Pandey. 1998. Polyamide nucleic acid targeted to the primer binding site of the HIV-1 RNA genome blocks in vitro HIV-1 reverse transcription. Biochemistry 37:900-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, S. W., H. F. Gallardo, E. Gilboa, and C. Smith. 1994. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human T cells by a potent Rev response element decoy consisting of the 13-nucleotide minimal Rev-binding domain. J. Virol. 68:8254-8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu, Y., V. Planelles, X. Li, C. Palaniappan, B. Day, P. Challita-Eid, R. Amado, D. Stephens, D. B. Kohn, A. Bakker, P. Fay, R. A. Bambara, and J. D. Rosenblatt. 1997. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication using a mutated tRNALys-3 primer. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14523-14531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak, J., M. Jiang, M. A. Wainberg, M. L. Hammarskjold, D. Rekosh, and L. Kleiman. 1994. Role of Pr160gag-pol in mediating the selective incorporation of tRNALys into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 68:2065-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mak, J., A. Khorchid, Q. Cao, Y. Huang, I. Lowy, M. A. Parniak, V. R. Prasad, M. A. Wainberg, and L. Kleiman. 1997. Effects of mutations in Pr160gag-pol upon tRNALys3 and Pr160gag-pol incorporation into HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 265:419-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michienzi, A., L. Cagnon, I. Bahner, and J. J. Rossi. 2000. Ribozyme-mediated inhibition of HIV 1 suggests nucleolar trafficking of HIV-1 RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8955-8960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori, K., Y. Yasutomi, S. Sawada, F. Villinger, K. Sugama, B. Rosenwith, J. L. Heeney, K. Uberla, S. Yamazaki, A. A. Ansari, and H. Rubsamen-Waigmann. 2000. Suppression of acute viremia by short-term postexposure prophylaxis of simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV-RT-infected monkeys with a novel reverse transcriptase inhibitor (GW420867) allows for development of potent antiviral immune responses resulting in efficient containment of infection. J. Virol. 74:5747-5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranga, U., C. Woffendin, S. Verma, L. Xu, C. H. June, D. K. Bishop, and G. J. Nabel. 1998. Enhanced T cell engraftment after retroviral delivery of an antiviral gene in HIV-infected individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1201-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richman, D. D. 2001. HIV chemotherapy. Nature 410:995-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roos, J. W., M. F. Maughan, Z. Liao, J. E. Hildreth, and J. E. Clements. 2000. LuSIV cells: a reporter cell line for the detection and quantitation of a single cycle of HIV and SIV replication. Virology 273:307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider, D. J., J. Feigon, Z. Hostomsky, and L. Gold. 1995. High-affinity ssDNA inhibitors of the reverse transcriptase of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. Biochemistry 34:9599-9610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullenger, B. A., H. F. Gallardo, G. E. Ungers, and E. Gilboa. 1990. Overexpression of TAR sequences renders cells resistant to human immunodeficiency virus replication. Cell 63:601-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Symensma, T. L., S. Baskerville, A. Yan, and A. D. Ellington. 1999. Polyvalent Rev decoys act as artificial Rev-responsive elements. J. Virol. 73:4341-4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tantillo, C., J. Ding, A. Jacobo-Molina, R. G. Nanni, P. L. Boyer, S. H. Hughes, R. Pauwels, K. Andries, P. A. Janssen, and E. Arnold. 1994. Locations of anti-AIDS drug binding sites and resistance mutations in the three-dimensional structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Implications for mechanisms of drug inhibition and resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 243:369-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuerk, C., and L. Gold. 1992. RNA pseudoknots that inhibit HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6988-6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuerk, C., and L. Gold. 1990. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249:505-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westaway, S. K., G. P. Larson, S. Li, J. A. Zaia, and J. J. Rossi. 1995. A chimeric tRNA(Lys3)-ribozyme inhibits HIV replication following virion assembly. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 33:194-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woffendin, C., U. Ranga, Z. Yang, L. Xu, and G. J. Nabel. 1996. Expression of a protective gene-prolongs survival of T cells in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2889-2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zack, J. A., S. A. Arrigo, S. R. Weitsman, A. S. Go, A. Haislip, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1990. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell 61:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]