Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous infectious pathogen that, when transmitted to the fetus in utero, can result in numerous sequelae, including late-onset sensorineural damage. The villous trophoblast, the cellular barrier between maternal blood and fetal tissue in the human placenta, is infected by HCMV in vivo. Primary trophoblasts cultured on impermeable surfaces can be infected by HCMV, but release of progeny virus is delayed and minimal. It is not known whether these epithelial cells when fully polarized can release HCMV and, if so, if release is from the basal membrane surface toward the fetus. We therefore ask whether, and in which direction, progeny virus release occurs from HCMV-infected trophoblasts cultured on semipermeable (3.0-μm-pore-size) membranes that allow functional polarization. We show that infectious HCMV readily diffuses across cell-free 3.0-μm-pore-size membranes and that apical infection of confluent and multilayered trophoblasts cultured on these membranes reaches cells at the membrane surface. Using two different infection and culture protocols, we found that up to 20% of progeny virus is released but that <1% of released virus is detected in the basal culture chamber. These results suggest that very little, if any, HCMV is released from an infected villous trophoblast into the villous stroma where the virus could ultimately infect the fetus.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is endemic, infecting 40 to 80% of urban populations in developed countries (10). The incidence of congenital HCMV infection is between 0.2 and 2.2% of all live-born infants. Such infections are one of the most common causes of mental retardation and nonhereditary sensorineural deafness in children (46, 48). Only 40% of pregnant women with primary HCMV infections give birth to infected infants (47) suggesting an effective fetal barrier, either physical or immunological. How HCMV is transmitted to the fetus during pregnancy is unknown; however, congenital infections are associated with chronic villitis (38, 41) and infection of the placenta (1, 4, 16, 32, 36-39, 41, 44, 45), which may also act as a viral reservoir (19). Passage through the placenta (2, 3) could occur in two directions: through the cytotrophoblast (CT) columns in anchoring villi or across the villous syncytiotrophoblast (ST) in the intervillous space.

Infection originating in the uterine wall could lead to infection of extravillous CT involved in either interstitial or endovascular invasion. Infection could then progress in a cell-to-cell manner through the CT columns of anchoring villi to the chorionic stroma and eventually infect the fetus (15). Although this route is possible during a reactivated uterine infection, endovascular CT comes into direct contact with maternal blood and therefore could also be exposed to a primary infection.

The ST lines all chorionic villi within the intervillous space, thereby interfacing maternal blood and fetal tissues. The ST is thus positioned to either physically prevent or to actively participate in the dissemination of virus across the placenta (3). The most probable routes of passage through the villous ST are (i) by damage of the ST resulting in gaps through which infected cells or virus could pass, (ii) by ST infection that spreads basally into the villous stroma and ultimately into the fetal circulation, and (iii) by transport of immunoglobulin-virus complexes across the ST. Evidence of permissive HCMV infection of the ST in the guinea pig model (18, 19) and the detection of infected trophoblasts in placentas from congenitally infected babies (16, 37, 43, 45, 52) suggest that transmission via ST infection may occur. However, little is known of the origin, nature, or consequences of such infections.

We and others have shown that trophoblasts isolated from the chorionic villi of first-trimester or term placentas can be permissively infected with HCMV (15, 20, 22). The infection is relatively inefficient even in the presence of a high virus inoculum and progresses slowly, and progeny virus remains predominantly cell associated with limited release into the supernatant (22). However, ST cells are epithelial cells with distinct apical and basal surfaces (7, 12, 23, 26, 42, 51). Since release of virus in a basal direction could result in direct transmission to fetal tissue, a more physiologic assessment of a productive HCMV infection of ST would be measurement of basal release. This approach requires culture of ST on semipermeable membranes that allow apical and basal virus diffusion.

Semipermeable membrane cell culture models have been used to demonstrate polarized infection by herpes simplex virus type 1 of Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells (21, 49, 50) but not retinal pigment epithelial cells (49, 50). HCMV infections in semipermeable membrane cultures of retinal pigment epithelial cells (50) and a colon epithelial cell line, Caco-2 (13, 27), have been explored (13, 27) to compare the susceptibilities of apical and basolateral membranes and to investigate directional release of progeny virus.

Construction of suitable confluent tight-junction membrane cultures of villous trophoblasts has been a particular challenge, primarily because isolated primary trophoblasts do not replicate and culture integrity must be maintained for at least a week after virus challenge. However, such cultures are available and are completely impenetrable, over a 6-hour period, by high levels of HCMV (23). Upon HCMV infection of these trophoblast membrane cultures, we find that the majority of progeny virus remains cell associated, with some apical, and relatively little basal, release.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells. (i) Isolation of term villous CT.

Placentas were obtained after normal term delivery or elective cesarean section from uncomplicated pregnancies. Villous CT cells (>99.99% pure) were isolated by trypsin-DNase digestion of minced chorionic tissue and immunoabsorption onto immunoglobulin (Ig)-coated glass bead columns (Biotex, Edmonton, Alberta) as previously described (28, 55), using anti-CD9 (clone 50H.19 [30, 35]) anti-major histocompatibility complex class I (W6/32; Harlan Sera-Lab, Crawley Down, Sussex, England) and anti-major histocompatibility complex class II (clone 7H3) antibodies for immunoelimination. Trophoblasts isolated from nine different placentas were cryopreserved for use in this study. Fully formed membrane cultures from all trophoblast preparations contained fewer than five vimentin-positive cells (nontrophoblasts) per insert as assessed by immunohistochemistry with vimentin antibody (Vim, clone V9; Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, Calif.).

(ii) Culture of CT on semipermeable insert membranes.

Insert membranes (6.4 mm; 3.0-μm pores) precoated with fibronectin (Biocoat; Becton Dickinson) were soaked in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) (GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GIBCO) and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml for 1 h prior to cell plating. Trophoblasts were seeded three times as previously described (23) to ensure confluency as detected by low diffusion rates of radiolabeled compounds and high transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) (see below). Briefly, 2 × 105 cells in 100 μl of 10% FBS-IMDM were seeded into soaked membrane inserts and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in specialized Falcon companion 24-well tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson). Nonadherent cells were removed 4 h later by three gentle shaking washes with prewarmed IMDM, and the cultures were replenished with 200 μl (per insert) and 800 μl (per culture well) of 10% FBS-IMDM containing 10 ng of recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Prepro-Tech, Rocky Hill, N.J.) (17, 34) per ml to promote syncytialization (33). On each of the third and seventh days of culture, freshly thawed and washed trophoblasts from the same placental preparation were added to the insert cultures as described above. The medium in both the insert and lower chambers was changed every 2 days. Syncytialization was confirmed by immunohistochemically staining fixed cells with desmoplakin antibody (Sigma Immunochemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) to visualize desmosome-containing junctions (11) as previously described (55).

(iii) HEL fibroblasts.

Human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts (supplied by J. Preiksaitis, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta) were propagated in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM), supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml. To assess stock and progeny viral titers of supernatants and cell lysates, 4 × 104 HEL fibroblasts were plated in 100 μl of 10% FBS-MEM in 96-well tissue culture wells and cultured to confluency. To assess progeny virus in the basal compartment (see below), HEL fibroblasts were plated in 800 μl of 10% FBS-MEM at a concentration of 105 cells per well in 24-well Falcon companion plates and grown to confluency. All cultures were used within 48 h of plating.

HCMV. (i) Virus stock preparations.

HCMV laboratory strain AD169 and a clinical isolate, Kp7 (from J. Preiksaitis), were propagated in HEL fibroblasts. The infectious virus titer was assessed by expression of HCMV immediate-early (IE) antigen after an 18-h culture of serial dilutions in HEL fibroblast microcultures as previously described (22). Each IE antigen-positive nucleus was equated to one infection focus (IF) of virus, and the titer was determined within a linear dose-response concentration range as IFs per milliliter.

(ii) Virus challenge protocols.

Challenge with AD169 or Kp7 at the multiplicities of infection (MOIs) indicated in the figure legends was carried out in 2% FBS-IMDM containing 10 ng of recombinant human EGF per ml for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The virus challenge for each experiment was calculated as IFs = MOI × number of nuclei per insert. The number of nuclei per insert was calculated in parallel inserts (for enumeration only) by multiplying the mean number of nuclei counted in five 0.25-mm2 fields by the total number of fields per insert (123 fields at a magnification of ×200). Trophoblast insert cultures were exposed to virus in two different ways.

In method 1, insert cultures were initially challenged with HCMV strain AD169 at an MOI of 10 after triple-seeded cultures achieved high TER and low [14C]dextran diffusion (see below) (23). After 24 h of challenge, both sides of the culture inserts were washed five times with serum-free IMDM and incubated with a pH 3.0 saline solution for 2 min to remove residual virus (8). The cultures were again washed with IMDM, resuspended in 2% FBS-IMDM, and further incubated as described in individual figure legends.

In method 2, after the first seeding and 3-day culture, trophoblasts were challenged with either AD169 or Kp7 for 24 h, followed by washing and a low-pH treatment as described above. The cultures were then replenished with 2% FBS-IMDM and cultured for 24 h. Following further washing to remove residual virus, the second and third seedings of trophoblasts were carried out as described above.

(iii) Assessment of infection.

Infection in trophoblast cultures is reported as percent IE antigen-positive nuclei, obtained by counting the total IE antigen-positive nuclei per insert and dividing by the estimated total nuclei per insert. Expression of the early-late HCMV antigen pp65 was assessed as the absolute number of pp65-positive foci, where each focus consisted of one or more closely associated positive nuclei. All trophoblast preparations were assessed for initial or reactivated HCMV infection by staining uninfected control cultures for IE and pp65 antigens as described below.

(iv) Monitoring of infectious progeny virus.

Progeny virus was monitored over time in three compartments: the supernatant of the culture insert (apical), the cell lysate (cells), and the supernatant in the underlying culture well (basal). At various times after viral challenge, each insert was carefully washed on both sides with IMDM, replenished with medium, and placed into a well containing confluent HEL fibroblasts. After 24 h, the insert was removed and the HEL culture was incubated for a further 18 h before fixing and staining for IE antigen (basal compartment). Insert culture supernatants were removed at various times after virus challenge and frozen at −80°C until they were assessed for viral titer (apical compartment). Adherent cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with a pH 3.0 saline solution for 2 min to remove external virus. After further washing, the cells were lysed in 100 μl of 2% FBS-IMDM by freezing and thawing three times and were stored at −80°C for assessment of viral titer (cell lysate). Virus titers in culture supernatants or cell lysates were assayed on confluent HEL cultures as described above and calculated as IFs per compartment. Monitoring of progeny virus as described above began in individual experiments only after demonstration of high TER (>60 Ω × cm2) and low [14C]dextran diffusion (<1.0 pmol/h/cm2) across infected insert cultures.

Immunohistochemical staining.

Infected and uninfected cultures were washed twice with PBS, fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min at −20°C, and washed three times with PBS. Membranes were fully immersed (both top and bottom) in staining reagents. Endogenous peroxidase activity was neutralized by a 30-min incubation at room temperature with 3% H2O2, which was followed by a 1-h blocking incubation at room temperature in 10% nonimmune goat serum (Zymed/Intermedico, Markham, Calif.). Primary antibodies detecting either HCMV IE antigen (detecting p72; Specialty Diagnostics, Dupont) or HCMV pp65 antigen (detecting pp64/pp65; Biotest, Dreieich, Germany) and their respective isotype controls, IgG2a (Zymed/Intermedico) and IgG1 (Dako Corporation) were added, and the plates or inserts in plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated overnight at 4°C. After thorough washing with PBS, secondary antibody (biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG) and streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (Streptavidin Biotin System, Histostain-SP Kit; Zymed) were added according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following a PBS wash, either Ni-DAB substrate (95 mg of diaminobenzidine, 1.6 g of NaCl, 0.136 g of imidazole, and 2 g NiSO4, made up to 200 ml with 0.1 M acetate buffer [pH 6.0]), yielding a dark brown precipitate, or aminoethyl carbazole substrate, yielding a red precipitate, was added and left for 2 to 5 min. The wells or inserts were then washed with double-distilled water. All insert cultures were counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma) to visualize nuclei and Stat Stain (VWR, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) to visualize cytoplasm. All HEL cultures were counterstained with hematoxylin alone. Once dry, the membrane was cut out of each insert and mounted in GVA mounting medium (Zymed) on a glass slide. Photographs were taken within a week of mounting.

TER.

TER was measured in an Endohm tissue resistance measurement chamber (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, Fla.) and monitored with a Millicell-ERS meter (Millipore/Continental Water Systems, Bedford, Mass.) as previously described (23). To obtain values independent of the membrane area, TER measurements were multiplied by the effective membrane area (0.3 cm2) and reported as Ω × cm2. All measurements are reported as net TER (total minus the mean TER of two cell-free inserts [22.8 Ω × cm2]).

Transepithelial diffusion of radiolabeled compounds.

The diffusion of 14C-labeled methylated dextran ([14C]dextran; molecular weight, 2,000,000; Sigma Radiochemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) (12.4 pmol/200 μl = 85,000 dpm) across trophoblast culture inserts was monitored as a function of time as previously described (23). The initial transepithelial flux was calculated as the diffusion velocity in the first 15 min normalized to the surface area of the membrane and expressed as picomoles per hour per square centimeter. A 100-fold excess of unlabeled (cold) dextran (molecular weight, 2,000,000; Sigma) was added with [14C]dextran in some experiments to a final volume of 200 μl per insert. Fresh inserts placed in culture medium 24 h prior to each diffusion assay were used as cell-free insert controls.

Confocal microscopy.

Triple-seeded trophoblast insert cultures were prepared as described above, challenged with HCMV AD169 at an MOI of 10 for 24 h, and cultured for a further 11 days with medium changes every 48 h. The cultures were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min at −20°C, washed well with PBS, and incubated with antibodies to HCMV IE antigen or pp65 as described above. After thorough washing with PBS, a fluoresceinated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse Ig conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546 [Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.]) was added at 10 μg/ml and left for 30 min. After washing, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dilactate (DAPI) (Molecular Probes) was added and left for 10 min to counterstain nuclei, and the inserts were washed well and then mounted on glass coverslips. Confocal analysis was carried out on a Zeiss microscope with an F-Fluar 40× objective lens and analyzed with the LSM510 software program. The inserts were scanned for Alexa Fluor 546 (excitation, 556 nm; emission, 573 nm) using the krypton-argon laser and for DAPI (emission, 461 nm) using a UV laser. The insert surface was also visualized using the UV laser.

RESULTS

HCMV diffuses through 3.0-μm pores of cell-free insert membranes.

Because of its large size (200 nm) (reviewed in reference 31), confirmation of HCMV diffusion through membrane insert pores was essential. Infectious virus was not detected in the basal chamber after a 2-h apical incubation over 0.45-μm-pore-size membranes (data not shown). However, infectious virus readily diffused through 3.0-μm pores. In the first hour after virus addition to the upper chamber, 5.69% ± 4.53% (n = 3 independent experiments) of the infectious virus diffused through 3.0-μm-pore-size membranes to infect HEL fibroblasts cultured in the basal chamber. Because of absorption and/or heat inactivation (53), infectious virus is rapidly lost from supernatants in cell-free tissue culture wells (94.5% ± 0.8% in the first hour [data not shown]). Thus, the above initial diffusion rate is a minimum estimate suggesting that relatively free diffusion occurs. All subsequent experiments were carried out using 3.0-μm-pore-size insert membranes.

Progeny virus in apical, cellular and basal compartments of infected triple-seeded trophoblast cultures.

To determine if virus can reach the basal compartment of a confluent infected trophoblast culture, the distribution of progeny virus in apical, cellular, and basal compartments was investigated. Confluent trophoblast layers on 3.0-μm-pore-size semipermeable insert membranes were prepared by seeding primary CT three times, interspersed with 3- to 5-day incubations in EGF (23). The cultures were infected when high TER and low [14C]dextran transepithelial diffusion were evident (data not shown). Data on infectious virus compartmentalization were gathered only while TER remained high (54.2 ± 12.4 Ω × cm2; n = 5) and [14C]dextran transepithelial diffusion remained low (0.18 ± 0.01 versus 9.12 ± 0.70 pmol/h/cm2; n = 5) compared to cell-free inserts. In four independent experiments only 0.02% ± 0.03% of infectious virus was captured in the basal culture compartment, with 8.6% ± 10.8% in the apical compartment (data not shown). As previously found in solid-substratum cultures (22), most (91.3% ± 10.8%) progeny virus was found in the cell lysates. On the date of assessment of progeny virus distribution, <1% HCMV IE antigen-positive nuclei and fewer than 100 pp65-positive foci containing 5 to 10 nuclei per focus were detected in any experiment performed.

Infected trophoblasts were found directly adjacent to the insert membrane.

Trophoblasts cultured on insert membranes exist in multiple layers with an average thickness of 2.7 cells (23). Thus, the very low levels of progeny virus detected in the basal compartment could be explained by a superficial infection that never reached the layer of trophoblasts in direct contact with the semipermeable insert membrane. To determine if infected cells were in direct contact with the membrane, IE antigen-positive (data not shown) or pp65-positive nuclei were spatially localized by confocal microscopy. Figure 1 shows that pp65-positive nuclei can be detected in the first 0.5 μm above the insert membrane. In this experiment, 26.5% ± 15.0% of pp65-positive nuclei were found at the membrane surface. This suggests that the infection spread laterally down through the trophoblast layers and reached cells attached directly to the insert membrane. Further, these data imply that if progeny virus is released basally, approximately one-fourth of the virus released would be proximal to membrane pores and therefore free for diffusion into the basal chamber.

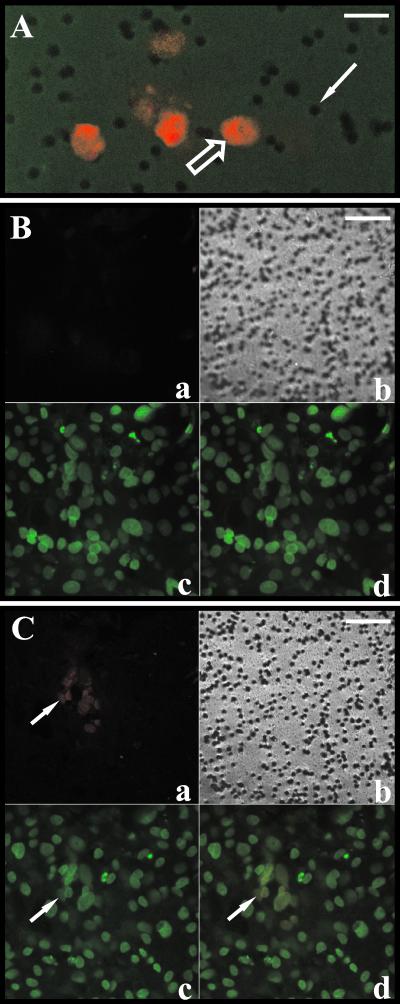

FIG. 1.

Infection reaches triple-seeded trophoblasts directly adjacent to the insert membrane. Trophoblast insert cultures were infected with HCMV as described in Materials and Methods. At 11 days after viral challenge, cultures were prepared for confocal analysis as described in Materials and Methods (HCMV pp65-positive nuclei stained red with Alexa Fluor 546, and all nuclei stained green [falsecolor] with DAPI; the insert surface also stained green). (A) A 0.5-μm optical section at the insert surface (green) showing the 3.0-μm pores (solid arrow) in focus and pp65-positive nuclei (open arrow). Bar, 12 μm. (B and C) Optical sections of the same field at different depths relative to the insert surface, i.e., 11.1 μm above (B) and 0.5 μm above (C). Bars, 30 μm. Arrows indicate a pp65-positive nucleus in the Alexa Fluor 546 scan (a), the DAPI scan (b), and the combined Alexa Fluor 546 and DAPI scans (c). Panels b are phase-contrast tungsten light images showing the insert membrane in focus in panel C but not in panel B.

Viral challenge after the first trophoblast seeding.

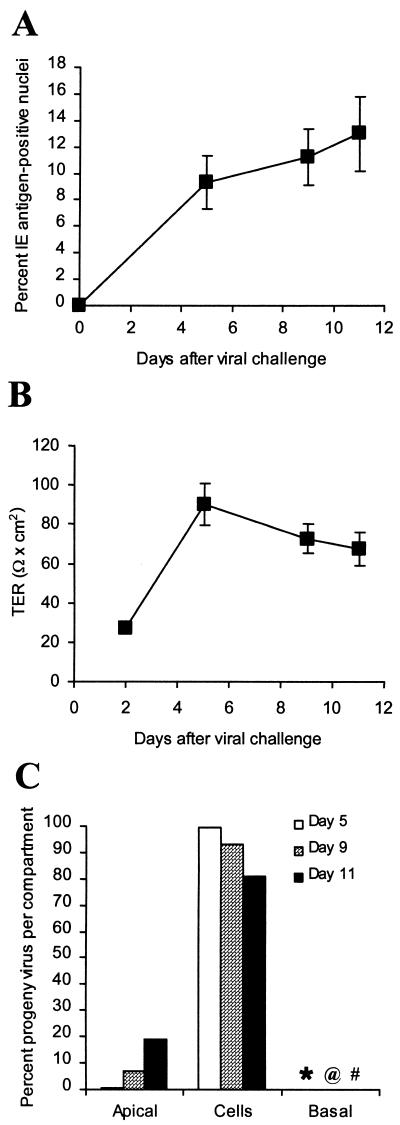

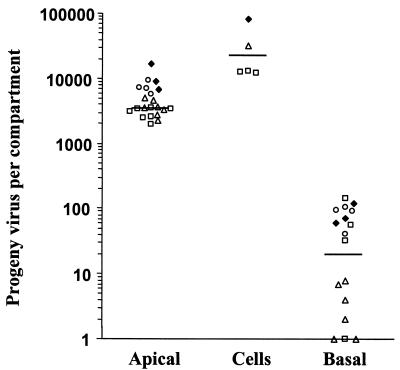

To increase the probability of virus-producing cells being adjacent to the insert membrane, trophoblasts were infected after the first of the three seedings required for confluency. At this stage of membrane culture formation, the cells are subconfluent and more closely resemble a monolayer (23). The culture was then bought to confluency with the usual second and third seedings. The time course of a representative experiment carried out with this protocol (out of a total of four performed) is depicted in Fig. 2. The low TER (25 Ω × cm2) observed 2 days after viral challenge illustrates the lack of tight-junctioned confluence in these cultures 1 day after the second seeding of trophoblasts (Fig. 2B). From the day after the third and final seeding of trophoblasts (day 5 after virus challenge) until the end of the experiment, the TER remained high (in the range of 70 to 90 Ω × cm2), indicating maintenance of a tight-junctioned and confluent culture (23). A much higher initial infection level was detected in these cultures compared to cultures infected after the third seeding of trophoblasts (>10% compared to <1%). The 10-fold increase in infection level in trophoblasts located in close proximity to the filter did not alter the progeny virus distribution pattern observed in trophoblast cultures infected after the third seeding. In the experiment depicted, >80% remained cell associated at the three time points tested, with <0.25% at any time found in the basal chamber (Fig. 2C). A summary of the results of four independent experiments with three different preparations of trophoblasts is presented in Fig. 3. The distribution of progeny virus, using median percentages, was 13.7% in apical supernatants, 83.7% in cell lysates, and 0.07% in the basal compartment. The data presented are from the final day of each experiment, just before TER fell and transepithelial diffusion increased, both indications of loss of culture integrity. As noted in the legend to Fig. 3, this final day varied in different experiments, depending on the trophoblast preparation. Increasing the virus challenge from an MOI of 10 to 20 did not alter the results (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Time course of infection in culture inserts infected after the first trophoblast seeding. Trophoblasts were cultured on inserts for 3 days with EGF and challenged after this first seeding with HCMV strain AD169 at an MOI of 10 for 24 h, followed by two additional seedings, as described in Materials and Methods. Cultures were as-sessed on days 5, 9, and 11 after viral challenge. (A) Mean ± standard deviation of percent IE antigen-positive nuclei determined in three replicate inserts. (B) Net TER measured in seven replicate inserts. Where error bars are not seen, the error was less than the width of the marker. (C) Distribution of progeny virus in each compartment determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values for the basal compartment: ∗, 0.04%; @, 0.07%; #, 0.21%. The data are from one of the four independent experiments partly summarized in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of progeny virus in apical, cellular, and basal compartments of trophoblast insert cultures infected after the first seeding of cells. A compilation of results from four independent experiments with trophoblasts infected on inserts after the first seeding, as described in the legend to Fig. 2, is shown. The amount of progeny virus in each compartment was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The percent IE antigen-positive nuclei on the day of assessment ranged from 13.0 to 25.0%. The day of assessment after viral challenge varied with each experiment and was dependent on maintenance of high TER and low [14C]dextran transepithelial diffusion. □, challenged at an MOI of 20 and assessed on day 11; ▵, challenged at an MOI of 20 and assessed on day 8; ♦, challenged at an MOI of 10 and assessed on day 18; ○, challenged at an MOI of 10 and assessed on day 8. Solid lines depict the median values for each compartment: apical, 3,522; cells, 22,250; and basal, 20.

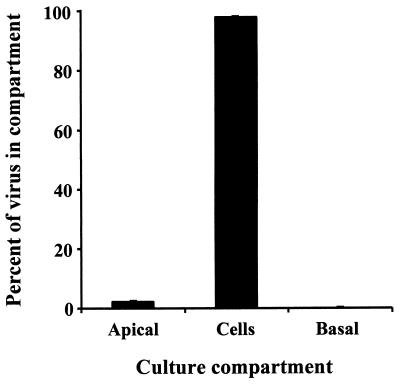

Very similar results were obtained with a clinical isolate of HCMV (Kp7) (Fig. 4). The infection frequency was consistently higher than that found with AD169 (28.6% ± 1.06% on day 8 and 45.3% ± 0.35% on day 10 for Kp7 compared to 10 to 12% for AD169) (Fig 2A). The total progeny virus produced exceeded by 10-fold that produced by AD169 infections (4.86 × 105 PFU/culture on day 10 for Kp7 compared to 2.57 × 104 for AD169 on approximately day 11) (Fig 3). By day 13 (Fig. 4), total progeny virus exceeded 8.07 × 106 PFU/culture. However, as with AD169, most (>98% on day 13) of the progeny virus was cell associated and most released virus was into the apical compartment, with only 0.4% of the total being released into the basal compartment.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of progeny virus in apical, cellular, and basal compartments after infection with a clinical isolate, Kp7. Trophoblasts were cultured on inserts for three days with EGF and challenged after the first seeding with an HCMV clinical isolate, Kp7, at an MOI of 10 for 24 h followed by two additional seedings, as described in Materials and Methods. Cultures were assessed for infection on day 13 after viral challenge, and the distribution of progeny virus in each compartment was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

A previous observation that progeny virus from HCMV-infected trophoblasts remains predominantly cell associated when cultured on nonpermeable plastic dishes (22) suggested that, although they are infectible, placental trophoblasts may not readily transmit virus to underlying fetal tissue. However, trophoblasts are polarized epithelial cells that may not manifest full transport and secretion functions when cultured on nonpermeable plastic. We have examined this important question more physiologically with a villous trophoblast semipermeable membrane culture model that allows trophoblast polarization and both apical and basal diffusion of secreted progeny virus (23). The trophoblasts in this model differentiate into a syncytial patchwork that forms an effective physical barrier as evidenced by high TER and low transepithelial diffusions of both high-molecular-weight ([14C]dextran) and low-molecular-weight ([3H]inulin) molecules as well as organisms such as HCMV. Using this model, we first found that the trophoblast layer could be infected by HCMV, albeit at lower efficiency than comparable cultures on solid plastic surfaces (up to 10-fold lower [D. G. Hemmings and L. J. Guilbert, unpublished data]). Interestingly, when cells were challenged with HCMV lab strain AD169 3 days after the first of three trophoblast seedings, the infection level was comparable to that observed in cultures on solid surfaces. This observation is in accord with findings that primary trophoblasts become more resistant to infection as they age in culture, suggesting that optimal infection occurs at an immature differentiation state (Hemmings and Guilbert, unpublished data). Second, we found that the infection in semipermeable membrane cultures progressed from immediate-early to late productive stages with some release of progeny virus. Although the amount of progeny virus released relative to the total produced was somewhat greater in membrane than solid-surface cultures, the majority remained cell associated after infection with either the lab strain AD169 or the clinical isolate Kp7. Taken together, these findings show that polarized and differentiated villous trophoblasts can be productively infected by HCMV with progeny virus remaining predominantly associated with the cellular compartment. This is the first study examining viral infection of polarized trophoblasts.

The above observations of significant progeny virus release from polarized membrane cultures led to the second question addressed with the culture model: is virus released in a polarized manner? This culture model is appropriate to the question. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 are secreted from trophoblasts in a polarized manner predominantly basal [23, 42]), and HCMV can diffuse through the 3.0-μm pores of the membrane (this paper). Two permutations of the culture model were developed to address the issue of basal release: (i) infection of the upper layer of trophoblasts after 12 days of culture (a completely formed, confluent, and differentiated membrane culture) and (ii) infection of the trophoblasts directly adjacent to the membrane after the first seeding and before full differentiation to syncytium, followed by two additional seedings and culture periods to form the confluent and differentiated culture. Both approaches gave the same result: there was very little release of progeny virus into the basal chamber (<0.4% of AD169 or Kp7 total progeny virus). To interpret results from the first model, we determined by confocal microscopy whether the infection spread from the most apical cell layer through two or three layers to cells adjacent to the semiporous membrane. Eleven days after infection, almost all infection foci consisted of vertical zones of infection reaching from the top of the culture to the membrane surface. Thus, progeny virus was available for basal secretion in both models at the membrane-most layer of cells. Once basally released from membrane-proximal cells, progeny virus has access to 3.0-μm pores, since ∼10% of the surface area of the membrane consists of pores (23) and most cells (average size, 25 μm) encounter multiple pores. A theoretical basal release can be calculated from the data in Fig. 3 as being equal to apical release of progeny virus. Detectable infectious virus actually reaching the basal chamber is <1% of this theoretical value. Thus, progeny virus is available at the membrane-most cell layer, as is the physical means for its diffusion through the membrane upon secretion, but basal secretion or diffusion of HCMV occurs minimally, if at all.

In this regard, it should also be noted that the experimental protocol was biased toward detection of basally released progeny virus. The apical supernatant and cell lysate were frozen and thawed (the latter at least three times) prior to assessment of infectious virus titer, but basal chamber detection was continuous. Virus activity is rapidly lost due to absorption and heat inactivation, and at least 10% of activity is lost on every freeze-thaw cycle (data not shown). Any correction would place more progeny virus in the lysate and apical supernatant and therefore, on a relative basis, less in the basal chamber.

It is very likely that even the small amount of virus detected in the basal compartment derives from leakage of apically released progeny virus through holes or breaks in the cell layers. In a culture model of HCMV-infected Caco-2 epithelial cells grown on 3.0-μm-pore-size insert membranes, most virus remained cell associated and some was released apically, but no basal release was observed until after the cellular monolayer began to deteriorate (20 days after viral challenge) (27). In a parallel fashion, we find that basal release from trophoblasts occurs late in culture at the time of cellular deterioration (Fig. 2). Further, we find that loss of membrane insert culture integrity almost invariably begins at the outer edge, leaving the center of the trophoblast culture intact, and that most infected HEL fibroblasts in the lower chamber are in a ring directly below the edge of the culture insert (data not shown). These observations suggest leakage, predominantly from the outer edge of the membrane culture, as the source of basal compartment virus.

The lack of detectable infectious virus in the basal chamber could be due either to the absence of basal release from the infected trophoblasts or to the presence of an intact trophoblast basement membrane (TBM) functioning as a barrier. Our results do not distinguish between these two possibilities. We have previously reported an electron-dense layer between trophoblasts and the insert membrane (23). In some cases this layer covers, but does not enter, the pores (data not shown). It has recently been shown that one component of the TBM is perlecan, a heparan sulfate proteoglycan (40), to which HCMV can bind. Perlecan could allow the TBM to absorb virus particles until removal by fetal macrophages. Future studies by electron microscopy to determine if progeny virus is sequestered in vacuoles in the trophoblast as in macrophages [14] or released and trapped in the electron-dense layer are therefore warranted. Burton and Watson (6) suggest that the basement membrane is an important placental barrier, since transient trophoblast damage down to the TBM followed by repair is often observed without concomitant fetal consequences (5, 54). Lack of basal release from infected trophoblasts and/or the presence of a TBM acting as an effective barrier may explain why vertical transmission does not occur more frequently in the first trimester than in the third trimester (9, 29) even though first-trimester trophoblasts are more readily infected (22).

These studies support the idea that in utero HCMV transmission is not caused solely by villous trophoblast infection. The trophoblast, like other epithelia, continuously renews its outer surface. Recent studies by Huppertz et al. suggest that ST renewal begins with CT fusion to ST and ends (with a half-life of 26 days) with the shedding of apoptotic bodies into the maternal circulation (24, 25). Our in vitro results show that mature membrane cultures retain progeny virus without concomitant cell damage for at least 20 days (Fig. 2 and 4). As previously seen in guinea pigs (19), the trophoblast may be acting as a sink for the virus, retaining it until the trophoblast is sloughed off into maternal circulation through normal trophoblast turnover. An infection of the outer ST layer in the absence of collaborative events would then be of little consequence. Such events as lateral spread to underlying CTs and consequent loss of trophoblast renewal capacity are under investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Hospital for Sick Children Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (cg 37992) to L.J.G. D.G.H. was supported by a studentship from Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

We thank Bonnie Lowen for expert technical assistance and the University of Alberta Perinatal Research Center laboratory staff and the OB/GYN nursing staff, both at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton, for placental cell preparations. The invaluable help of Xue-Jun Sun in the Cell Imaging Facility at the Cross Cancer Institute is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altshuler, G., and A. J. McAdams. 1971. Cytomegalic inclusion disease of a nineteen-week fetus. Case report including a study of the placenta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 111:295-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becroft, D. M. 1981. Prenatal cytomegalovirus infection: epidemiology, pathology and pathogenesis. Persp. Pediatr. Pathol. 6:203-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benirschke, K., and P. Kaufmann (ed.). 2000. Pathology of the human placenta. Springer Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Benirschke, K., G. R. Mendoza, and P. L. Bazeley. 1974. Placental and fetal manifestations of cytomegalovirus infection. Virchows Arch. B 16:121-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton, G. J., S. O'Shea, T. Rostron, J. E. Mullen, S. Aiyer, J. N. Skepper, R. Smith, and J. E. Banatvala. 1996. Significance of placental damage in vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. J. Med. Virol. 50:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton, G. J., and A. L. Watson. 1997. The structure of the human placenta: implications for initiating and defending against virus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 7:219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellucci, M., and P. Kaufmann. 2000. Basic structure of the villous trees, p. 50-115. In K. Benirschke and P. Kaufmann (ed.), Pathology of the human placenta. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Compton, T. 2000. Analysis of cytomegalovirus ligands, receptors, and the entry pathway, p. 53-65. In J. Sinclair (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine: cytomegalovirus protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cook, S. M., K. S. Himebaugh, and T. S. Frank. 1993. Absence of cytomegalovirus in gestational tissue in recurrent spontaneous abortion. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 2:116-119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demmler, G. J. 1991. Summary of a workshop on surveillance for congenital cytomegalovirus disease. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:315-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas, G. C., and B. F. King. 1990. Differentiation of human trophoblast cells in vitro as revealed by immunocytochemical staining of desmoplakin and nuclei. J. Cell Sci. 96:131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton, B. M., and M. P. Oakey. 1994. Sequential preparation of highly purified microvillous and basal syncytiotrophoblast membranes in substantial yield from a single term human placenta: inhibition of microvillous alkaline phosphatase activity by EDTA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1193:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esclatine, A., M. Lemullois, A. L. Servin, A. M. Quero, and M. Geniteau-Legendre. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus infects Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells basolaterally regardless of the differentiation state. J. Virol. 74:513-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fish, K. N., A. S. Depto, A. V. Moses, W. Britt, and J. A. Nelson. 1995. Growth kinetics of human cytomegalovirus are altered in monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Virol. 69:3737-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher, S., O. Genbacev, E. Maidji, and L. Pereira. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus infection of placental cytotrophoblasts in vitro and in utero: implications for transmission and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 74:6808-6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia, A. G., E. F. Fonseca, R. L. Marques, and Y. Y. Lobato. 1989. Placental morphology in cytomegalovirus infection. Placenta 10:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Lloret, M., J. Yui, B. Winkler-Lowen, and L. J. Guilbert. 1996. Epidermal growth factor inhibits cytokine-induced apoptosis of primary human trophoblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 167:324-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith, B. P., M. Chen, and H. C. Isom. 1990. Role of primary and secondary maternal viremia in transplacental guinea pig cytomegalovirus transfer. J. Virol. 64:1991-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffith, B. P., S. R. McCormick, C. K. Fong, J. T. Lavallee, H. L. Lucia, and E. Goff. 1985. The placenta as a site of cytomegalovirus infection in guinea pigs. J. Virol. 55:402-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halwachs-Baumann, G., M. Wilders-Truschnig, G. Desoye, T. Hahn, L. Kiesel, K. Klingel, P. Rieger, G. Jahn, and C. Sinzger. 1998. Human trophoblast cells are permissive to the complete replicative cycle of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 72:7598-7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi, K. 1995. Role of tight junctions of polarized epithelial MDCK cells in the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Med. Virol. 47:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmings, D. G., R. Kilani, C. Nykiforuk, J. K. Preiksaitis, and L. J. Guilbert. 1998. Permissive cytomegalovirus infection of primary villous term and first-trimester trophoblasts. J. Virol. 72:4790-4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemmings, D. G., B. Lowen, R. Sherburne, G. Sawicki, and L. J. Guilbert. 2001. Villous trophoblasts cultured on semi-permeable membranes form an effective barrier to the passage of high and low molecular weight particles. Placenta 22:70-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huppertz, B., H. G. Frank, J. C. Kingdom, F. Reister, and P. Kaufmann. 1998. Villous cytotrophoblast regulation of the syncytial apoptotic cascade in the human placenta. Histochem. Cell Biol. 110:495-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huppertz, B., H. G. Frank, F. Reister, J. Kingdom, H. Korr, and P. Kaufmann. 1999. Apoptosis cascade progresses during turnover of human trophoblast: analysis of villous cytotrophoblast and syncytial fragments in vitro. Lab. Investig. 79:1687-1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Illsley, N. P., Z. Q. Wang, A. Gray, M. C. Sellers, and M. M. Jacobs. 1990. Simultaneous preparation of paired, syncytial, microvillous and basal membranes from human placenta. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1029:218-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarvis, M. A., C. E. Wang, H. L. Meyers, P. P. Smith, C. L. Corless, G. J. Henderson, J. Vieira, W. J. Britt, and J. A. Nelson. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus infection of Caco-2 cells occurs at the basolateral membrane and is differentiation state dependent. J. Virol. 73:4552-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilani, R., L.-J. Chang, D. Hemmings, and L. J. Guilbert. 1997. Placental trophoblasts resist infection by multiple human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 variants even with cytomegalovirus coinfection but support HIV replication after provirus transfection. J. Virol. 71:6359-6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar, M. L., and S. L. Prokay. 1983. Experimental primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy: timing and fetal outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 145:56-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maclean, G. D., T. R. Mosmann, J. J. Akabutu, and B. M. Longenecker. 1982. Preference of the early murine immune response for polymorphic determinants on human lymphoid-leukemia cells and the potential use of monoclonal antibodies to these determinants in leukemia-typing panel. Oncodev. Biol. Med. 3:223-232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mocarski, E. S. 1996. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication, p. 2447-2492. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, et al. (ed.), Fields virology. Lippencott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 32.Monif, G. R., and R. M. Dische. 1972. Viral placentitis in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 58:445-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrish, D. W., D. Bhardwaj, L. K. Dabbagh, H. Marusyk, and O. Siy. 1987. Epidermal growth factor induces differentiation and secretion of human chorionic gonadotropin and placental lactogen in normal human placenta. J. Clin. Endocrin. Metab. 65:1282-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrish, D. W., J. Dakour, H. Li, J. Xiao, R. Miller, R. Sherburne, R. C. Berdan, and L. J. Guilbert. 1997. In vitro cultured human term cytotrophoblast: a model for normal primary epithelial cells demonstrating a spontaneous differentiation programme that requires EGF for extensive development of syncytium. Placenta 18:577-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrish, D. W., A. R. Shaw, J. Seehafer, D. Bhardwaj, and M. T. Paras. 1991. Preparation of fibroblast-free cytotrophoblast cultures utilizing differential expression of the CD9 antigen. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 27A:303-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mostoufi-Zadeh, M., S. G. Driscoll, S. A. Biano, and R. B. Kundsin. 1984. Placental evidence of cytomegalovirus infection of the fetus and neonate. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 108:403-406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muhlemann, K., R. K. Miller, L. Metlay, and M. A. Menegus. 1992. Cytomegalovirus infection of the human placenta: an immunocytochemical study. Hum. Pathol. 23:1234-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura, Y., S. Sakuma, Y. Ohta, K. Kawano, and T. Hashimoto. 1994. Detection of the human cytomegalovirus gene in placental chronic villitis by polymerase chain reaction. Hum. Pathol. 25:815-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quan, A., and L. Strauss. 1962. Congenital cytomegalic inclusion disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 83:1240-1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohde, L. H., M. J. Janatpore, M. T. McMaster, S. Fisher, Y. Zhou, K. H. Lim, M. French, D. Hoke, J. Julian, and D. D. Carson. 1998. Complementary expression of HIP, a cell-surface heparan sulfate binding protein, and perlecan at the human fetal-maternal interface. Biol. Reprod. 58:1075-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sachdev, R., G. J. Nuovo, C. Kaplan, and M. A. Greco. 1990. In situ hybridization analysis for cytomegalovirus in chronic villitis. Pediatr. Pathol. 10:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sawicki, G., M. W. Radomski, B. Winkler-Lowen, A. Krzymien, and L. J. Guilbert. 2000. Polarized release of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 from cultured human placental syncytiotrophoblasts. Biol. Reprod. 63:1390-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneeberger, P. M., F. Groenendaal, L. S. de Vries, A. M. van Loon, and T. M. Vroom. 1994. Variable outcome of a congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a quadruplet after primary infection of the mother during pregnancy. Acta Paediatr. 83:986-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz, D. A., R. Khan, and B. Stoll. 1992. Characterization of the fetal inflammatory response to cytomegalovirus placentitis. An immunohistochemical study. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 116:21-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinzger, C., H. Muntefering, T. Loning, H. Stoss, B. Plachter, and G. Jahn. 1993. Cell types infected in human cytomegalovirus placentitis identified by immunohistochemical double staining. Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 423:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stagno, S. 1995. Cytomegalovirus, p. 332-353. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 47.Stagno, S., R. F. Pass, G. Cloud, W. J. Britt, R. E. Henderson, P. D. Walton, D. A. Veren, F. Page, and C. A. Alford. 1986. Primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Incidence, transmission to fetus, and clinical outcome. JAMA 256:1904-1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strauss, M. 1985. A clinical pathologic study of hearing loss in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Laryngoscope 95:951-962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Topp, K. S., A. L. Rothman, and J. H. Lavail. 1997. Herpes virus infection of RPE and MDCK cells: polarity of infection. Exp. Eye Res. 64:343-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tugizov, S., E. Maidji, and L. Pereira. 1996. Role of apical and basolateral membranes in replication of human cytomegalovirus in polarized retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 77:61-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vanderpuye, O. A., and C. H. Smith. 1987. Proteins of the apical and basal plasma membranes of the human placental syncytiotrophoblast: immunochemical and electrophoretic studies. Placenta 8:591-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Lijnschoten, G., F. Stals, J. L. Evers, C. A. Bruggeman, M. H. Havenith, and J. P. Geraedts. 1994. The presence of cytomegalovirus antigens in karyotyped abortions. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 32:211-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vonka, V., and M. Benyeshmelnick. 1966. Thermoinactivation of human cytomegalovirus. J. Bacteriol. 91:221-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watson, A. L., and G. J. Burton. 1998. A microscopical study of wound repair in the human placenta. Micros. Res. Technol. 42:351-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yui, J., M. I. Garcia-Lloret, A. J. Brown, D. W. Berdan, D. W. Morrish, T. G. Wegmann, and L. J. Guilbert. 1994. Functional, long-term cultures of human term trophoblasts purified by column-elimination of CD9 expressing cells. Placenta 15:231-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]