Abstract

Immunogenicity and protective activity of four cell-based feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) vaccines prepared with autologous lymphoblasts were investigated. One vaccine was composed of FIV-infected cells that were paraformaldehyde fixed at the peak of viral expression. The other vaccines were attempts to maximize the expression of protective epitopes that might become exposed as a result of virion binding to cells and essentially consisted of cells mildly fixed after saturation of their surface with adsorbed, internally inactivated FIV particles. The levels of FIV-specific lymphoproliferation exhibited by the vaccinees were comparable to the ones previously observed in vaccine-protected cats, but antibodies were largely directed to cell-derived constituents rather than to truly viral epitopes and had very poor FIV-neutralizing activity. Moreover, under one condition of testing, some vaccine sera enhanced FIV replication in vitro. As a further limit, the vaccines proved inefficient at priming animals for anamnestic immune responses. Two months after completion of primary immunization, the animals were challenged with a low dose of homologous ex vivo FIV. Collectively, 8 of 20 vaccinees developed infection versus one of nine animals mock immunized with fixed uninfected autologous lymphoblasts. After a boosting and rechallenge with a higher virus dose, all remaining animals became infected, thus confirming their lack of protection.

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is an important pathogen of domestic cats and a valuable model for AIDS studies (51). In particular, FIV has been extensively used for testing strategies for the development of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vaccines, with outcomes that have ranged from complete immunity to absolute lack of protection or even enhanced susceptibility, depending on the types of immunogen and viral challenge used (for reviews, see references 4, 13-15, 28, and 64). For example, in experiments in which the challenge consisted of ex vivo-derived FIV never passaged in vitro and therefore representative of difficult-to-neutralize field strains, a vaccine composed of cells of the T-lymphoid line MBM acutely infected and paraformaldehyde fixed at the FIV expression peak (FCMBM vaccine) efficiently protected specific-pathogen-free (SPF) cats against homologous virus, whereas inactivated cell-free virus vaccines did not (37-39). Of note, the cell-based vaccine proved promising also when tested in field cats (40).

The present extension of our studies was prompted by several findings. First, a number of HIV-1-neutralizing, gp120-specific human and murine monoclonal antibodies were seen to react with increased affinity with receptor-complexed gp120, suggesting that the epitopes involved are especially exposed on cellular surface-bound virions (30, 60). Second, immunization of specific transgenic mice with paraformaldehyde-fixed mixtures of cells expressing HIV-1 Env glycoproteins (gp) and receptors yielded antibodies that neutralized an unusually broad range of primary HIV-1 isolates, suggesting that, after interaction with appropriate cell receptors and transition to a “fusion-competent” conformation, the Env of HIV-1 expresses otherwise cryptic conserved neutralization epitopes (32, 47). Third, anti-HIV monoclonal antibodies produced by immunizing mice with virus-infected cells were often neutralizing (11). Finally, the FCMBM vaccine was seen to absorb neutralizing antibodies from infected cat sera in vitro more efficiently than inactivated whole FIV vaccines (23). These findings, in conjunction with the observation that day-of-challenge FIV neutralizing titers of FCMBM-vaccinated cats correlated with protection (23), made it feasible that the superior protective efficacy of this and similar cell-based vaccines tested by other groups (3, 16, 27, 67, 68) relative to the ones composed of cell-free virions was due to viral epitopes rendered immunologically functional by FIV interaction with cell surfaces (designated here as interaction dependent [ID]).

In an attempt to test such possibility, we prepared and tested in SPF cats four differently formulated cell-based vaccines having as a common feature the use of autologous primary lymphoblasts (PLB). It was, in fact, reasoned that formulating the vaccines with autologous instead than allogeneic cells would minimize the load of nonviral antigens in the inocula, thus favoring the generation of immune effectors directed at viral determinants—especially the ones less powerful or less represented—and hopefully affording a solid protection. Except for substrate cells, one autologous vaccine (FCPLB) was formulated exactly as the FCMBM vaccine discussed above. The others (ID-1, ID-2, and ID-3) were attempts to enrich the immunogens in putative ID determinants and consisted of cells mildly fixed after near saturation of their surface with adsorbed, internally inactivated FIV particles. None of these vaccines induced adequate levels of FIV-neutralizing antibodies in immunized cats. On the contrary, under one condition of testing, the sera of ID vaccine groups enhanced FIV replication in vitro. Also, formation of anti-cell antibodies was not prevented, and the vaccinees failed to respond anamnestically to a booster dose. Furthermore, all vaccine groups proved unprotected against the homologous virus, and some possibly exhibited an augmented susceptibility compared to animals mock immunized with fixed uninfected autologous PLB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, cells, and viruses.

Female SPF cats, 7 months old when received from Iffa Credo (L'Arbresle, France), were housed individually in our climatized animal facility under European Community law conditions, sorted at random into groups, and clinically examined once per week. Several weeks before the experiment started, all animals were bled under slight anesthesia to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). The PBMC of each individual animal were then immediately and separately stimulated with 5 μg of concanavalin A (ConA)/ml in mass culture, and PLB generated 3 days later were washed and used to prepare the entire set of vaccine doses needed for the immunization schedule in Fig. 1 with the formulations described below. Between-animal variations in PLB ability to support FIV growth in vitro were minimal to none (data not shown). Unless otherwise stated, the virus was the Italian isolate FIV-M2 of clade B, which has been widely used in our laboratory (37-39). The stocks of this virus used in vaccines preparation and in neutralization assays, as well as the stocks of FIV-M45 and M73 used in some neutralization tests, had been propagated a limited number of times in vitro and consisted of supernatant harvested from acutely infected MBM cells at the time of peak reverse transcriptase (RT) production. MBM cells are a line of interleukin-2- and ConA-dependent feline T-lymphoid cells established in our laboratory from the PBMC of an uninfected SPF cat (38). The stock of FIV-M2 used for challenging vaccinees had instead been passaged only in cats and consisted of plasma prepared and titrated in vivo as previously described (38).

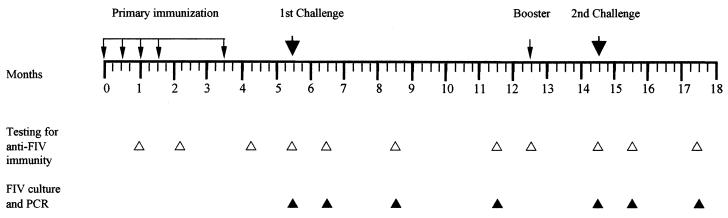

FIG. 1.

Experimental plan. Groups of five cats (four in the case of the mock-1 vaccine) were given five subcutaneous doses of the immunogens mixed 1:1 with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant in a total volume of 2 ml (small arrows). The immunogens used and their FIV contents are shown in Table 1. Two months after completion of this primary immunization, all cats were challenged intravenously (large arrows) with 5 CID50 of homologous virus (plasma of infected cats). The animals that after 7 months were still virus negative were given a booster dose of their respective immunogens and, after 2 additional months, challenged again with 10 CID50 of the same virus.

FCPLB vaccine.

This immunogen was prepared exactly as previously described (38) except that autologous PLB substituted for the MBM cells. In brief, PLB were infected with FIV at a multiplicity of infection of 0.02 and, 8 days later, i.e., at the peak of virus expression as determined by indirect membrane immunofluorescence (IF), were fixed with 1.25% paraformaldehyde at 37°C for 24 h. Inactivation of infectivity was verified by inoculating MBM cells, which were maintained in culture for 8 weeks without recovery of virus. Each vaccine dose consisted of 5 × 106 total cells in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), corresponding to ca. 2.7 × 106 cells FIV antigen-positive by membrane IF (Table 1). This was considerably less than the 3 × 107 cells per dose, more than 1.8 × 107 of which were virus-positive cells, that had been used in FCMBM vaccine studies (38) but was the maximum we could achieve with autologous PLB.

TABLE 1.

Immunogens used and their FIV contentsa

| Immunogen | Composition | Mean % IF-positive cells ± SDb | Mean virus content/106 cells ± SD |

Infectivity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinc (μg) | RNAd (no. of copies) | In vitroe | In vivof | |||

| FCPLB | Infected, fixed PLB | 54 ± 1 | 50 ± 2 | (5.0 ± 0.6) × 109 | − | − |

| ID-1 | PLB + AT2-FIV | 23 ± 2 | 15 ± 1 | (5.8 ± 0.8) × 108 | − | − |

| ID-2 | PLB + AT2-FIV + peptide SU5 | 20 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 | (2.6 ± 0.5) × 108 | − | − |

| ID-3 | PLB + AT2-FIV + peptide TM59 | 24 ± 1 | 12 ± 2 | (2.4 ± 0.3) × 108 | − | − |

| Mock-1 | PLB | 0 | 0 | <103 | − | − |

| Mock-2 | PLB + peptides SU5 and TM59 | 0 | 0 | <103 | − | − |

Values shown are the means ± the standard deviations of the immunogens prepared for each prospective vaccinee.

That is, the percent membrane IF-positive cells when probed with anti-FIV serum and anti-cat IgG polyclonal serum conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Cells were lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-electrophoresis sample buffer at 60°C for 30 min, electrophoresed, and examined by using a semiquantitative Western blot assay.

Cells were lysed and tested for viral RNA by TM-PCR.

Cells were tested for FIV infectivity by inoculation into MBM cells, which were then monitored for FIV production for 8 weeks.

Based on testing immunized cats by virus isolation and TM-PCR 5.5 months after the first inoculation of the immunogens.

Internal inactivation of FIV and preparation of ID vaccines.

The ID immunogens were prepared by using FIV internally inactivated with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine (aldrithiol-2 [AT2]). After appropriate pilot experiments (see below), the viral stock to be used for vaccine preparation was incubated with 300 μM AT2 at 4°C for 2 h, pelleted in the cold at 20,000 × g for 90 min, and resuspended at 1 mg/ml in PBS (AT2-FIV). Immunogen ID-1 was then produced by incubating AT2-FIV with PLB at the ratio of 20 μg per 5 × 105 cells at 4°C for 2 h and, after having pelleted and resuspended them, fixing the virus-PLB complexes with 0.2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h with gentle agitation. The cells were finally washed four times with abundant PBS, resuspended at 5 × 106 cells per ml in PBS, divided into aliquots, and stored in liquid nitrogen. For the ID-2 and ID-3 immunogens, the formulation was modified slightly to include two synthetic peptide inhibitors of FIV active at different steps of cell entry and potentially capable of stabilizing the viral Env in an optimal conformation for putative ID epitopes expression. The inhibitors were peptides 5 (for ID-2) and 59 (for ID-3), derived from the amino-terminal region of the surface gp and from the membrane-proximal domain of the transmembrane gp of FIV (35) and designated here SU5 and TM59, respectively. The conditions of AT2-FIV-cell contact were chosen on the basis of observations with HIV-1 (10, 21) partly confirmed with FIV (8), showing that at 4°C Env adsorption to cells and its initial consequent changes take place within minutes, but the eventual modifications that lead to fusion do not occur until the temperature is switched to 37°C. The peptides were thus added at 6.4 μg/106 cells to AT2-FIV-PLB mixtures prepared exactly as described for ID-1 formulation and already incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The mixtures were then further kept an additional h each at 4 and at 37°C and finally fixed and further processed exactly as for ID-1. Immunizing doses contained 5 × 106 cells, corresponding to 1 to 1.2 × 106 cells FIV antigen-positive by membrane IF (Table 1).

Mock immunogens.

Two mock immunogens were obtained by processing PLB as for preparation of ID-1 (mock-1) and ID-2 and ID-3 (mock-2), except that FIV was omitted and mock-2 contained both peptides SU5 and TM59. Each immunizing dose consisted of 5 × 106 cells (Table 1).

Quantitation of FIV in the immunogens.

FIV antigen on the surface of vaccine cells was determined by IF with the sera of FIV-infected cats as a probe exactly as previously described (38). Western blotting was also performed as described previously (6), except that it was rendered semiquantitative by electrophoresing the vaccines in parallel with scaled concentrations of whole AT2-FIV. The numbers of FIV RNA copies present in the vaccines were determined by TaqMan-PCR (TM-PCR) as detailed below.

Assays for antibodies.

The total immunoglobulin G (IgG) binding antibodies to gradient-purified and sonicated whole FIV, lectin-purified FIV gp, and immunodominant linear domains of FIV gp were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (41). The titers were expressed as reciprocals of the highest serum dilutions that gave optical density readings at least threefold higher than the average values obtained with 10 control FIV-negative sera plus three times the standard deviation. Neutralizing antibodies were measured, with or without prior adsorption of test sera with MBM cells (23), against 10 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) of low-passage FIV by using MBM cells as indicator and 50% inhibition of RT production as the readout. Unless otherwise stated, the test was carried out by incubating the virus-serum mixtures at 4°C for 1 h, exactly as previously described (23). Neutralizing titers were defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution which reduced by ≥50% the levels of RT activity produced by virus exposed to the same dilution of serum pooled from 10 normal cats and calculated by the method of Reed and Münch (54).

Lymphoproliferation assay.

Freshly harvested Ficoll-separated PBMC (1.5 × 105) were incubated with 0.1 μg of gradient-purified and sonicated whole FIV, lectin-purified FIV gp, or lectin-purified MBM cell gp in 200 μl of RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated, AB-positive human serum and 2 mM l-glutamine and, after 4 days, were pulsed with [3H]thymidine for 18 h. The stimulation index (SI) was calculated as the ratio of radioactivity incorporated in the presence of antigen to that in the absence. Only SI values of ≥2 were considered indicative of FIV-specific lymphoproliferation.

Qualitative and semiquantitative FIV reisolation.

Virus reisolation from cats was carried out by cocultivating 106 ConA-stimulated PBMC with 5 × 105 MBM cells and assaying the supernatants for RT once a week (38). Cultures were considered negative if they showed no evidence of RT activity during the 5-week culture period. Infectious cell loads in the PBMC were determined by limiting-dilution reisolation.

Detection and quantitation of FIV DNA and RNA.

Genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coat cells by using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy). Provirus DNA was quantitated by amplifying 0.3 to 0.6 μg of extracted DNA by TM-PCR on the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Monza, Italy), with 900 nM M2-S sense primer (AGACCGCTGCCCTATTTCACT; nucleotide positions 1296 to 1316 and referred to as FIV-Petaluma [59]), 300 nM M2-AS antisense primer (TTCTGGCTGGTGCAAATCTG; nucleotides 1367 to 1386), and 100 nM M2-P probe (TGCCTGTTGTTCTTGAGTTAATCCTATTCCCA; nucleotides 1330 to 1359) and under conditions described elsewhere (52). The standard curve was generated by coamplifying serial 10-fold dilutions (102 to 107) of pGEM-M2 plasmid containing the whole p25 region of FIV-M2. The lowest limit of detection was 100 copies, as determined by amplifying pGEM-M2 dilutions in a background of 1 μg of genomic DNA.

FIV RNA copies in the immunogens and in plasma were enumerated by extraction with the RNeasy Mini kit and the QIAamp Viral RNA kit (Qiagen), respectively, reverse transcribing 10 μl of the extracts with 300 nM M2-AS and then amplifying by TM-PCR with 900 nM M2-S and 100 nM M2-P. Serial 10-fold dilutions (102 to 107) of gag p25 RNA transcripts produced by runoff transcription of pGEM-M2 were used to produce the standard curve. The sensitivity of the assay was 200 copies per ml of plasma or 103 copies per 106 cells as determined by amplifying FIV-negative plasma or cells spiked with serial 10-fold dilutions of pGEM-M2 RNA transcripts.

Lymphocyte T-cell counts.

CD4+ T lymphocytes were enumerated with monoclonal antibody FE1.7B12 (obtained from P. F. Moore, Davis, Calif.) and analyzed in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). CD8+ T-lymphocyte counts were also performed but did not provide important information for this study.

RESULTS

Production and characterization of the immunogens.

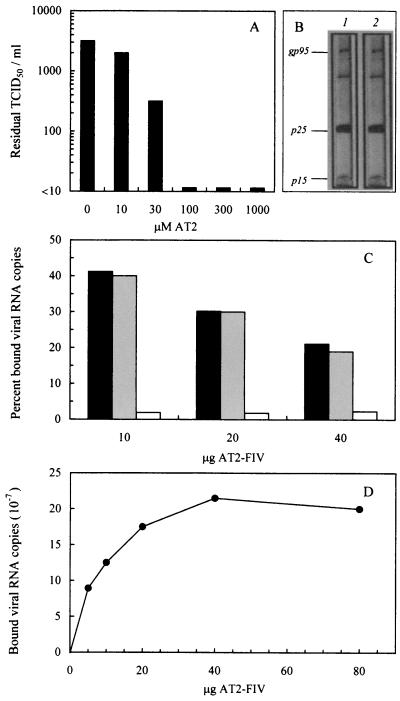

Formulation of ID vaccines required that FIV was rendered noninfectious, but conformation and function of its Env remained in a native state. For this reason, we inactivated FIV by targeting an internal structure. This was attained by using AT2, a compound which blocks multiple essential functions of the nucleocapsid protein of retroviruses by covalently binding its zinc fingers and ejecting the coordinated Zn2+ (24). AT2 had been shown to effectively block the infectivity of HIV-1 and SIV at a step preceding reverse transcription and to leave the viral surface conformationally and functionally intact, as determined by normal virion binding to cell receptors, virus-induced membrane fusion, and immunoreactivity (1, 56, 62), but had never been used to inactivate FIV. Thus, we preliminarily investigated this aspect. As shown in Fig. 2A, treatment with ≥100 μM AT2 at 4°C for 2 h completely ablated FIV infectivity for highly permissive MBM cells. Based on this result, we chose to use 300 μM AT2 for routine inactivation. AT2-FIV showed no appreciable deviations in electrophoretic mobility of the antigens revealed by an immune serum (Fig. 2B) and bound feline PLB as efficiently as native FIV (Fig. 2C). Importantly, because the number of virus particles that bound PLB reached near saturation at ca. 20 μg of AT2-FIV per 5 × 105 cells (Fig. 2D), this virus to cell ratio was chosen for formulating the ID immunogens.

FIG. 2.

Effects of AT2 treatment on FIV properties. (A) Effect on infectivity. The FIV stock used for vaccine production was incubated at 4°C for 2 h with the indicated concentrations of AT2 and then titrated for residual infectivity in MBM cell cultures. Values shown are the viral titers obtained at day 8 of culture expressed as TCID50. (B) Effect on electrophoretic mobility. Viral samples treated at 4°C for 2 h with no AT2 (lane 1) or with 300 μM AT2 (lane 2) were electrophoresed and then probed with FIV-immune cat serum, followed by peroxidase-conjugated anti-cat IgG polyclonal antibody. (C) Effect on ability to bind PLB. A total of 5 × 105 PLB was mixed with the indicated amounts of FIV, which was either native (▪), inactivated with 300 μM AT2 ( ), or AT2-inactivated and then disrupted by sonication (□). After 2 h at 4°C, the PLB were pelleted and examined for bound FIV RNA copies by quantitative TM-PCR. The results are expressed as the percent viral RNA copies found associated with the cells relative to the number of input copies. (D) Dose curve of AT2-FIV binding to PLB. Indicated amounts of AT2-FIV were incubated with 5 × 105 PLB which, after 2 h at 4°C, were pelleted and examined as described above for bound viral RNA. The results are expressed as the numbers of viral RNA copies found associated with the cells.

Prior to use in vivo, all of the immunogens prepared as described in Materials and Methods were characterized. As summarized in Table 1, they exhibited the expected characteristics. (i) The FCPLB vaccine had the highest content in viral components by all of the parameters investigated, a finding consistent with the fact that it was based on cells productively infected and fixed at the peak of FIV production. Notably, the proportion of cells expressing viral antigen on their surface (54%) was moderately reduced relative to the FCMBM vaccine of our previous studies which contained >60% virus-positive cells (38). (ii) Compared to FCPLB, the three ID vaccines showed about half the number of cells that stained FIV-positive by membrane IF, ca. one-fourth of the total viral proteins, and ca. one-tenth of the viral RNA copies, a finding in line with the fact that FIV had only been fixed onto PLB from without. (iii) The ID-2 and ID-3 vaccines had viral contents similar to that of ID-1, a finding consistent with the fact that contained peptides inhibited FIV entry at steps subsequent to attachment (35). (iv) Mock-1 and mock-2 immunogens were virus negative by all of the parameters investigated. (v) All immunogens proved noninfectious in tissue culture.

We had previously observed that the protective FCMBM vaccine was more effective than other nonprotective vaccines at depleting immune sera of their FIV-neutralizing antibodies and proposed this as an in vitro test for screening candidate vaccines (23). The immunogens were evaluated also in this respect. Three FIV-infected cat sera, diluted 1:64, were adsorbed in microwells with 2 × 105 vaccine cells at 4°C for 1 h, incubated for 1 h at 37°C with fresh cells, clarified, and finally examined for neutralizing activity (23). The specimens tested were the FCPLB vaccine, a pool of the ID vaccines, a pool of the mock vaccines and, as a positive control, the FCMBM vaccine. As shown in Table 2, the mock immunogens had no effect on the neutralizing power of immune sera, the FCPLB vaccine reduced it uniformly but less efficiently than FCMBM, and the ID vaccines slightly reduced the titer of one serum only.

TABLE 2.

Ability of different immunogens to consume the FIV-neutralizing activity of three immune sera

| Serum no.a | Neutralizing titer after adsorption with immunogen |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | FCPLB | IDb | Mockc | FCMBM | |

| 753 | 512 | 64 | 512 | 512 | <64 |

| 1694 | 512 | 64 | 512 | 512 | <64 |

| 2508 | 256 | 64 | 64 | 256 | <64 |

All sera were from cats FIV infected 12 months earlier and diluted 1:64 prior to incubation with the immunogens. The experiment was repeated twice, with comparable results.

Pool of ID-1, ID-2, and ID-3.

Pool of mock-1 and mock-2.

Immune responses to the immunogens.

All immunogens were finally used to immunize cats with the schedule in Fig. 1. The animals remained clinically healthy and, as assessed by culture and PCR assays, FIV-free for at least 5.5 months after the initiation of immunization when they were challenged (data not shown). Antibody responses were monitored by two IgG ELISA assays against purified and disrupted whole FIV or lectin-purified gp derived thereof. As shown by Fig. 3A, binding antibodies to whole FIV were detected after the second vaccine dose, peaked 4 months after initiation of immunization, and had slightly declined at the time of challenge. When measured with purified FIV gp (Fig. 3B), antibody responses appeared especially prompt since they peaked 1 to 2 months after initiation of immunization in all groups; however, there was no further increase in antibody level thereafter, suggesting that the increases in titers detected by the whole-FIV ELISA at later samplings were mainly due to antibodies against internal virus antigens. No major differences were noted among groups, but in general the antibody titers elicited by ID immunogens were moderately higher than those elicited by the FCPLB vaccine.

FIG. 3.

FIV-binding IgG antibodies in vaccinated and mock-immunized cats, as determined by ELISA with purified and disrupted whole FIV (A and C) or lectin-purified gp derived thereof (B and D) as the test antigen. (A and B) Responses to primary immunization. (C and D) Responses of animals that had escaped infection after the first virus challenge to a booster given 9 months after the completion of primary immunization. Symbols represent geometric means, and bars indicate 95% confidence limits. For symbols without bars, the limits lie within the symbols. Arrowheads indicate immunogen doses. Immunogen: ▪, FCPLB; ♦, ID-1; ▴, ID-2; •, ID-3; □, mock-1; ○, mock-2.

In the ELISAs described above, mock-immunized cats also exhibited substantial levels of reactivity (Fig. 3). Since this finding raised the clear possibility that a large proportion of the binding antibodies induced by the vaccines reacted to determinants derived from the host cells used for test antigens production (61), we proceeded to evaluate the effect of preadsorbing the sera with such cells. Adsorption was carried out by incubating selected pools of sera diluted 1:200 with 106 MBM cells at 4°C for 1 h, followed by 1 h at 37°C with fresh cells. As shown in Table 3, this treatment completely removed the ELISA reactivity of mock-immunized cat sera and markedly reduced the titers of vaccine sera. It was thus apparent that only a fraction of the binding antibodies elicited by the vaccines were directed to truly viral antigens.

TABLE 3.

Effect of preadsorbing with MBM cells on the titers of FIV-binding antibodies exhibited by vaccinated, mock-immunized, and control sera

| Cat group | Time of serum collection | ELISA antibody titera with: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole FIV |

FIV gp |

||||

| Untreated | Adsorbed | Untreated | Adsorbed | ||

| FCPLB | Peakb | 5,200 | 1,600 | 4,800 | 3,000 |

| First challenge | 2,500 | 800 | 3,600 | 800 | |

| Second challengec | 1,200 | 600 | 1,200 | 600 | |

| ID-1 | Peak | 8,000 | 1,600 | 5,400 | 2,500 |

| First challenge | 4,400 | 1,600 | 4,200 | 1,800 | |

| Second challenge | 1,400 | 1,000 | 1,800 | 1,200 | |

| ID-2 | Peak | 4,200 | 1,000 | 5,200 | 1,800 |

| First challenge | 2,900 | 800 | 4,000 | 1,200 | |

| Second challenge | 1,400 | 800 | 1,600 | 800 | |

| ID-3 | Peak | 12,000 | 3,200 | 18,000 | 3,200 |

| First challenge | 6,200 | 1,800 | 12,000 | 2,200 | |

| Second challenge | 2,200 | 1,000 | 2,000 | 1,600 | |

| Mock-1 | Peak | 3,000 | <200 | 2,200 | <200 |

| First challenge | 1,400 | <200 | 1,400 | <200 | |

| Second challenge | 800 | <200 | 800 | <200 | |

| Mock-2 | Peak | 2,400 | <200 | 2,500 | <200 |

| First challenge | 2,000 | <200 | 2,000 | <200 | |

| Second challenge | 400 | <200 | 400 | <200 | |

| Infectedd | 12 mo post infection | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 |

| Uninfected, unvaccinated | <200 | <200 | <200 | <200 | |

The experiment was performed twice with comparable results.

Peak, four months after initiation of immunization.

Second challenge, animals that had escaped infection after the first challenge alone.

Pool of sera 753, 1694, and 2508 described in Table 2.

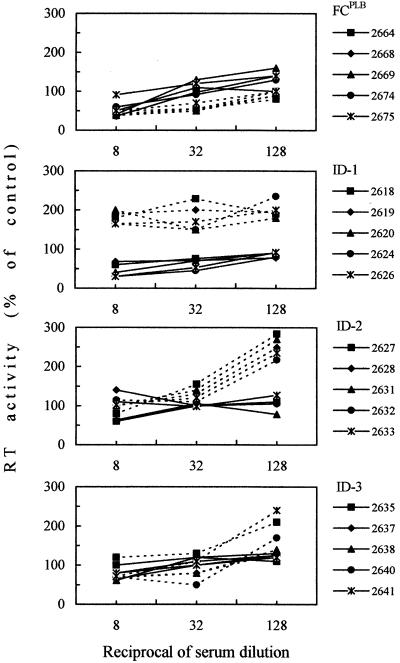

Day-of-challenge sera were also assayed for IgG antibodies to two synthetic peptides representing immunodominant linear domains of FIV Env (Table 4). Mock-immunized animals tested uniformly negative (data not shown), whereas vaccinated cats exhibited generally moderate levels of reactivity (Table 4). Day-of-challenge sera also exhibited no (ID-3 sera) or very low inhibitory activity for the virus used in vaccine preparation when examined with a sensitive neutralization test (Table 4). All sera also failed to neutralize FIV-M45 and FIV-M73, two heterologous clade B Italian isolates (data not shown). Furthermore, adsorption of sera with substrate cells—a procedure that in a previous study had revealed the presence of otherwise-masked neutralizing antibodies (23)—and various modifications of the neutralization test suggested to us by recent studies with HIV-1 (57, 70) failed to augment the inhibitory power of sera. On the contrary, when the conditions for virus-serum contact were modified to facilitate the action of putative antibodies to ID epitopes (Fig. 4), some vaccine sera exerted an evident virus-enhancing effect. Specifically, this was observed with sera from all of the ID groups but not with FCPLB (Fig. 4) or mock immunogen sera (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Antibodies to two immunodominant epitopes of FIV Env and virus-neutralizing activity in day-of-challenge sera of vaccinated cats

| Group | No. of positive animals/total no. of animals (mean titer ± SD)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding antibodies to peptideb |

Neutralizing antibodiesc | ||

| V3.3 | TM | ||

| FCPLB | 5/5 (40) | 5/5 (40) | 4/5 (13 ± 3) |

| ID-1 | 4/5 (36 ± 26) | 3/5 (40 ± 26) | 5/5 (16 ± 9) |

| ID-2 | 5/5 (64 ± 53) | 3/5 (67 ± 26) | 3/5 (8) |

| ID-3 | 3/5 (53 ± 30) | 4/5 (50 ± 24) | 0/5 |

Values are presented as the number of positive animals/the total number of animals examined, with the mean antibody titer in positive sera ± the standard deviation given in parentheses.

V3.3 is a 22-mer peptide of the V3 region of FIV surface gp, TM a 20-mer peptide in the apex region of the transmembrane gp.

Neutralizing antibody titers with or without prior adsorption of sera with the MBM cells used as substrate for the neutralization assay did not significantly differ. Preimmunization sera were constantly devoid of neutralizing activity.

FIG. 4.

FIV neutralization curves with day-of-challenge vaccine sera as determined by two different procedures. In the standard procedure (solid lines), sera were reacted with FIV at 4°C for 1 h before inoculation into MBM cell cultures, which were then immediately incubated at 37°C. In the other procedure (dashed lines), aimed at facilitating antibody interaction with ID epitopes, MBM cell cultures were reacted with FIV at 4°C for 1 h, inoculated with cold test sera, further incubated at 4°C for 1 h, and finally transferred to 37°C. All sera were preadsorbed with MBM cells prior to testing.

Cell-mediated immunity was studied in lymphoproliferation assays by examining PBMC harvested at the time of challenge and at two earlier time points. As shown in Table 5, a substantial proportion of vaccinees reacted positively to whole FIV and FIV gp at all three times, with no appreciable differences among groups and samplings. Mock-immunized animals were uniformly negative. The same was true for responses to control gp from the host cells in which the viral antigens had been produced (data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Proliferative responses of PBMC from vaccinated cats to FIV antigens at different times after initiation of immunization

| Group | Lymphoproliferative responsea at: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mo |

4.25 mo |

5.5 mob |

14.5 moc |

|||||

| FIV | FIV gp | FIV | FIV gp | FIV | FIV gp | FIV | FIV gp | |

| FCPLB | 2/5 (2-3) | 2/5 (2.1) | 4/5 (2-7) | 3/5 (4-6) | 4/5 (3-4) | 2/5 (3-4) | 1/2 (2) | 1/2 (3) |

| ID-1 | 3/5 (4-5) | 2/5 (2-3) | 3/5 (3-5) | 3/5 (2-4) | 3/5 (2-3) | 2/5 (3-5) | 2/3 (2) | 2/3 (2-3) |

| ID-2 | 3/5 (2-8) | 2/5 (7-8) | 3/5 (6-11) | 2/5 (3-7) | 2/5 (2-3) | 2/5 (2-3) | 2/3 (2-5) | 2/3 (2-3) |

| ID-3 | 4/5 (3-15) | 4/5 (2-15) | 4/5 (2-8) | 3/5 (3-4) | 3/5 (2-4) | 2/5 (2-3) | 3/4 (3-5) | 3/4 (3-4) |

| Mock-1 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Mock-2 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

Results are presented as the number of animals with an SI of ≥2/the total number of animals examinated. In parentheses, the range of values observed is given. Responses to control gp from uninfected MBM cells, in which the viral antigens were produced, were uniformly negative at all times tested.

First challenge.

Second challenge.

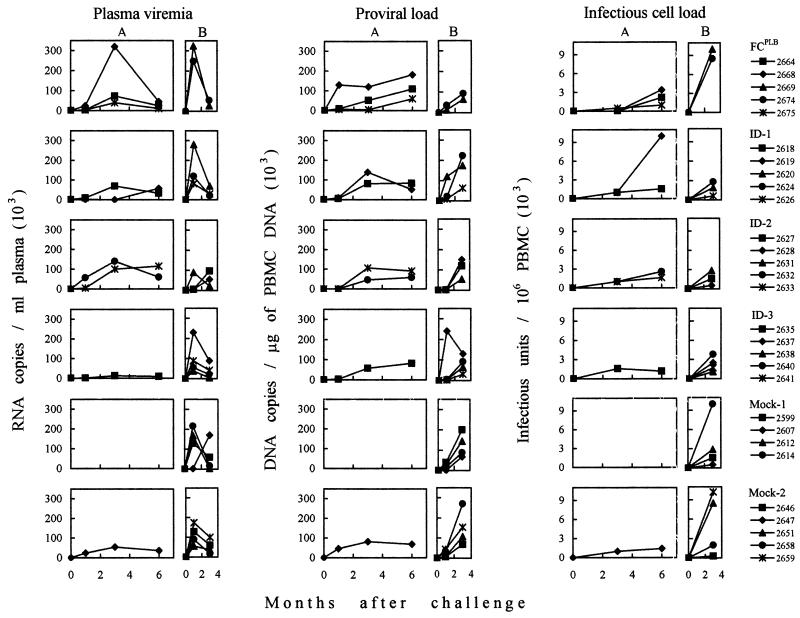

Outcome of a first, low-dose virus challenge.

Two months after completion of immunization, all cats were injected intravenously with 5 50% cat infectious doses (CID50) of FIV plasma. Table 6 summarizes the results of the 6-month follow-up. Only one of nine animals in the mock-1 and mock-2 groups became FIV infected, a result most likely reflecting the suboptimal virus dose used. However, due to the lack of an untreated control group, we could not exclude that mock immunization contributed to prevent the full success of challenge by stimulating innate resistance or otherwise (16, 58, 63). In the vaccine groups the FCPLB-, ID-1-, ID-2-, and ID-3-infected animals were three, two, two, and one of five, respectively (Table 6 and Fig. 5). Thus, none of the vaccines had protected the animals, in spite of the weakness of the challenge dose used, and some had possibly facilitated infection. It should be noted, however, that the different rates of infection did not reach statistical significance even when pooled vaccine groups were compared to pooled control animals. Virus-positive animals exhibited substantially similar plasma and PBMC viral burdens and dynamics (Fig. 5) and similar declines of circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes (Table 6) regardless of the immunogen administered but were too few in each group to provide valuable information about the infection course.

TABLE 6.

Virological, serological, and immunological markers of infection in vaccinated and mock-immunized cats after FIV challenge

| Cat group and no.a | Presence of marker at indicated time after first challengeb |

Cats with productive infection (no. of cats positive/total no. of cats) at: |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mo |

3 mo |

6 mo |

6 mo after first challenge | 3 mo after second challenge | ||||||||||

| VI | PCR | S | CD4 | VI | PCR | S | CD4 | VI | PCR | S | CD4 | |||

| FCPLB | 3/5 | 2/2 | ||||||||||||

| 2664 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2668 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2669 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2674 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2675 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| ID-1 | 2/5 | 3/3 | ||||||||||||

| 2618 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | ||

| 2619 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2620 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2624 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2626 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| ID-2 | 2/5 | 3/3 | ||||||||||||

| 2627 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2628 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2631 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2632 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2633 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| ID-3 | 1/5 | 4/4 | ||||||||||||

| 2635 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | ||

| 2637 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2638 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2640 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2641 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| Mock-1 | 0/4 | 4/4 | ||||||||||||

| 2599 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2607 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2612 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2614 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| Mock-2 | 1/5 | 4/4 | ||||||||||||

| 2646 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2647 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2651 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2658 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2659 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

All animals were virus isolation and PCR negative at the time of challenge.

VI (+ and −), positive and negative virus isolation by coculture with MBM cells, respectively; PCR (+ and −), positive and negative TM-PCR for proviral FIV gag sequences in PBMC, respectively; S (+ and −), ELISA antibody titer at least fourfold higher than and not significantly different from the time-of-challenge level, respectively; CD4 (+ and −), CD4+ T-lymphocyte count reduced by ≥50% and not significantly different from the time-of-challenge level, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Plasma viremia and proviral and infectious cell burdens in the PBMC of vaccinated and mock-immunized cats that became infected after the first (A) and second (B) FIV challenges.

Response to a booster vaccine dose.

Seven months after the first challenge all cats that had remained uninfected showed markedly reduced levels of antibodies as determined by ELISA (Fig. 3C and D). Because it was of interest to rechallenge these animals, they were administered a booster of the respective immunogens and, 2 months later, i.e., at the time of second challenge, they were monitored again. All animals (i) were found to have undergone very modest or no increases of total (Fig. 3C and D) and truly FIV-specific binding antibodies (Table 3), (ii) tested completely negative for neutralizing antibodies (data not shown), and (iii) were poorly reactive in lymphoproliferation tests (Table 5), findings indicative of the absence of an appreciable anamnestic immune response.

Outcome of a second, regular-dose virus challenge.

Since boosted animals remained virus negative, as determined by culture and PCR (data not shown), they could be challenged again with the same virus stock and route as for the first challenge but with a dose increased to 10 CID50. As a result, all animals became infected regardless of the immunogens received (Table 6). Furthermore, at least during the 3-month follow-up, the different groups exhibited comparable viral burdens (Fig. 5) and circulating CD4+ T-lymphocyte losses (data not shown). Notably, postinfection ELISA antibody titers showed no evidence of an anamnestic response in the vaccinees (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have produced and tested four cell-based FIV vaccines, all of which were custom made, i.e., prepared for each prospective vaccinee with its own PLB. One vaccine (FCPLB) was “conventional” in that it was composed of fixed massively infected cells similar to other previously tested cell-based FIV vaccines (3, 16, 27, 31, 38, 67, 68). The others were variations around the feasibility of producing immunogens enriched in ID epitopes and consisted of cells fixed after adsorption of internally inactivated FIV particles onto the cell surface in the presence or absence of two peptide inhibitors of virus entry. Disappointingly, none of these vaccines protected against challenge with homologous ex vivo-derived FIV, thus proving clearly inferior to the previously described FCMBM vaccine (37, 38). In fact, after a suboptimal-dose challenge, the rates of infection in the vaccinees were similar or higher than in parallel animals mock immunized with fixed autologous PLB alone and, after a larger challenge, all animals became equally infected. Thus, the present results are in line with a report by Karlas et al. (31), who observed that cats immunized with six shots of 5 × 106 fixed autologous PLB containing 1 to 5% FIV-expressing cells were not protected and exhibited an accelerated course of FIV infection.

Substantial evidence indicates that, to confer protection, candidate antilentiviral vaccines have to stimulate and sustain robust humoral and cell-mediated immune responses (25). For example, the need for neutralizing antibodies to be high in titer in order to correlate with vaccinal protection has recently been emphasized with FIV (23) and other animal models of AIDS vaccination as well (22, 43, 49). The levels of FIV-specific lymphoproliferation generated by the present autologous cell-based vaccines were only moderately lower than those previously observed in FCMBM vaccine-protected cats, but elicited antibodies were scarce in specificity, as shown by the considerable reductions in FIV and FIV gp binding titers observed after adsorption of sera with host cells. In addition, antibodies had very poor virus-neutralizing activity, and under one condition of testing the ID vaccines sera caused an enhancement of in vitro FIV replication. As a further weakness, the vaccines appeared to be incapable of priming animals for anamnestic immune responses.

A stringent comparison of the performances of the present vaccines and the previously tested FCMBM vaccine (38) is not possible because, due to the different cell substrate, the immunizing doses of the former contained between 7-fold (FCPLB) and 18-fold (ID-3) fewer virus-expressing cells. This probably reflected a lower ability of fresh PLB to support FIV replication relative to highly susceptible lymphoid cell lines (18, 29). Some of the frustrating results obtained here are, however, hard to explain solely on the basis of the lower quantity of virus antigen administered. For example, enhancement of FIV infection and failure to prime for secondary immune responses are best explained on the basis of differences in the quality of the immunogenic stimuli provided. Except for the type of substrate cell used, FCPLB was formulated exactly as was the FCMBM vaccine, which had been prepared with a lymphoid T-cell line. Thus, it seems logical to attribute the unsatisfactory performance of at least this immunogen to the use of autologous PLB. Interestingly, the FCPLB vaccine consumed less neutralizing antibody activity in vitro than did the FCMBM vaccine, a finding suggestive of a less efficient expression of neutralization epitopes. Why this should occur is unclear, but understanding it is clearly important.

The use of autologous PLB as a substrate was suggested by the desire for keeping the contents in nonrelevant, competing antigenic determinants of the vaccines as low as possible, thus favoring immune responses to viral determinants. Although the induction of anti-cell antibodies by in vitro-cultured autologous cells is not unprecedented (33), the development of the remarkably high levels of such antibodies that were observed was unexpected. Because the virus-negative mock immunogens also produced abundant anti-cell antibodies, the effect is most likely attributable to paraformaldehyde fixation, possibly in combination with mitogen stimulation of vaccine cells and adjuvant administration (36). In any case, the occurrence of a robust humoral response to cell antigens may have reduced responses to viral determinant by mechanisms such as antigenic competition and rapid immune elimination of repeatedly inoculated vaccine cells. Notably, in contrast to what was previously observed with the sera of FCMBM-vaccinated cats (23), we found no evidence here nor in our previous study that anti-autologous cell antibodies interfered with detection of virus neutralizing antibodies. Also, lymphoproliferative assays showed no evidence that the vaccinees had mounted cell-mediated responses to cellular antigens.

Most antilentiviral vaccines tested to date have failed to reproducibly elicit antibodies capable of neutralizing a wide spectrum of primary viral isolates (44-46, 50). As mentioned earlier, in the case of HIV-1 this has been attributed to the cryptic status of conserved neutralization epitopes in viral particles, based on the observation that these became functional after the viral Env was allowed to interact with cell receptors (47). One aim of the present study was to ascertain whether FIV-neutralizing antibody responses of increased breadth are evocable with variously designed cell-based vaccines. That the modest neutralizing antibody responses elicited by some such vaccines, as well as the more potent ones elicited by the FCMBM vaccine (23), failed to inhibit heterologous FIV isolates represents another disturbing finding. There are several possible explanations. First, the weak overall FIV-specific antigenic stimulus conveyed by the ID vaccines may have not permitted responses to poorly immunogenic epitopes. Increasing stimulus strength—for example, by using multiple-subtype vaccines (53)-might obviate this limitation. Second, formulations may have been inappropriate to unveil cryptic conserved neutralization epitopes. Studies with HIV-1 have indicated that ID epitopes may remain occluded at viral Env-cell interfaces, probably due to the close proximity of the interacting membranes (17, 42). Third, FIV might possess no key conserved ID neutralization determinants. According to recent data, FIV enters cells via a two-receptor mechanism like recent HIV-1 and SIV isolates (7, 8, 12, 20, 48, 55, 65, 66), but this does not necessarily imply that FIV possesses neutralization epitopes that are rendered functional by conformational changes of its Env. The present findings clearly indicate that generating broadly neutralizing antibodies to FIV will most likely require more sophisticated immunogens than were used here such as, for example, soluble compounds designed to selectively mimic the relevant target viral structures (2, 5, 9, 17, 19, 30, 69). Further, these findings suggest the possibility that putative ID immunogens elicit FIV-enhancing and -neutralizing antibodies. Precedents for this are the HIV-1-enhancing effects exerted by some antibodies raised with the gp120-CD4 binding complex (26, 34).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministero della Sanità-Istituto Superiore di Sanità (“Programma per l'AIDS”) and from the Ministero della Università e Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica, Rome, Italy. S.G. holds fellowships from ANLAIDS, Rome, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur, L. O., J. W. Bess, Jr., E. N. Chertova, J. L. Rossio, M. T. Esser, R. E. Benveniste, L. E. Henderson, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Chemical inactivation of retroviral infectivity by targeting nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers: a candidate SIV vaccine. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:S311-S319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binley, J. M., R. W. Sanders, B. Clas, N. Schuelke, A. Master, Y. Guo, F. Kajumo, D. J. Anselma, P. J. Maddon, W. C. Olson, and J. P. Moore. 2000. A recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein complex stabilized by an intermolecular disulfide bond between the gp120 and gp41 subunits is an antigenic mimic of the trimeric virion-associated structure. J. Virol. 74:627-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop, S. A., C. R. Stokes, T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, C. V. Whiting, J. E. Humphries, R. Osborne, M. Papanastasopoulou, and D. A. Harbour. 1996. Vaccination with fixed feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)-infected cells: protection, breakthrough, and specificity of response. Vaccine 14:1243-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogers, W. M. J. M., C. Cheng-Mayer, and R. C. Montelaro. 2000. Developments in preclinical AIDS vaccine efficacy models. AIDS 14:S141-S151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton, D. R., and P. W. H. I. Parren. 2000. Vaccines and the induction of functional antibodies: time to look beyond the molecules of natural infection? Nat. Med. 6:123-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calandrella, M., D. Matteucci, P. Mazzetti, and A. Poli. 2001. Densitometric analysis of Western blot assays for feline immunodeficiency virus antibodies. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 79:261-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, D. C., and P. S. Kim. 1998. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93:681-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Parseval, A., and J. H. Elder. 2001. Binding of recombinant feline immunodeficiency virus surface glycoprotein to feline cells: role of CXCR4, cell-surface heparans, and an unidentified non-CXCR4 receptor. J. Virol. 75:4528-4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Rosny, E., R. Vassell, P. T. Wingfield, C. T. Wild, and C. D. Weiss. 2001. Peptides corresponding to the heptad repeat motifs in the trasmembrane protein (gp41) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elicit antibodies to receptor-activated conformations of the envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 75:8859-8863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doranz, B. J., S. S. W. Baik, and R. W. Doms. 1999. Use of a gp120 binding assay to dissect the requirements and kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus fusion events. J. Virol. 73:10346-10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edinger, A. L., M. Ahuja, T. Sung, K. C. Baxter, B. Haggarty, R. W. Doms, and J. A. Hoxie. 2000. Characterization and epitope mapping of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies produced by immunization with oligomeric simian immunodeficiency virus envelope protein. J. Virol. 74:7922-7935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egberink, H. F., E. De Clercq, A. L. Van Vliet, J. Balzarini, G. J. Bridger, G. Henson, M. C. Horzinek, and D. Schols. 1999. Bicyclams, selective antagonists of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4, potently inhibit feline immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 73:6346-6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elder, J. H., G. A. Dean, E. A. Hoover, J. A. Hoxie, M. H. Malim, L. Mathes, J. C. Neil, T. W. North, E. Sparger, M. B. Tompkins, W. A. F. Tompkins, J. Yamamoto, N. Yuhki, N. C. Pedersen, and R. H. Miller. 1998. Lesson from the cat: feline immunodeficiency virus as a tool to develop intervention strategies against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:797-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elder, J. H., and T. R. Phillips. 1995. Feline immunodeficiency virus as a model for development of molecular approaches to intervention strategies against lentivirus infections. Adv. Virus Res. 45:225-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elyar, J. S., M. C. Tellier, J. M. Soos, and J. K. Yamamoto. 1997. Perspectives on FIV vaccine development. Vaccine 15:1437-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finerty, S., C. R. Stokes, T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, T. J. Hillman, F. J. Barr, and D. A. Harbour. 2001. Targeted lymph node immunization can protect cats from a mucosal challenge with feline immunodeficiency virus. Vaccine 20:49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnegan, C. M., W. Berg, G. K. Lewis, and A. L. DeVico. 2001. Antigenic properties of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope during cell-cell fusion. J. Virol. 75:11096-11105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flynn, J. N., C. A. Cannon, D. Sloan, J. C. Neil, and O. Jarrett. 1999. Suppression of feline immunodeficiency virus replication in vitro by a soluble factor secreted by CD8+ T lymphocytes. Immunology 96:220-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fouts, T. R., R. Tuskan, K. Godfrey, M. Reitz, D. Hone, G. K. Lewis, and A. L. DeVico. 2000. Expression and characterization of a single-chain polypeptide analogue of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120-CD4 receptor complex. J. Virol. 74:11427-11436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey, S. C. S., E. A. Hoover, and J. I. Mullins. 2001. Feline immunodeficiency virus cell entry. J. Virol. 75:5433-5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frey, S., M. Marsh, S. Gunther, A. Pelchen-Matthews, P. Stephens, S. Ortlepp, and T. Stegmann. 1995. Temperature dependence of cell-cell fusion induced by the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 69:1462-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauduin, M. C., P. W. H. I. Parren, R. Weir, C. F. Barbas III, D. R. Burton, and R. A. Koup. 1997. Passive immunization with a human monoclonal antibody protects hu-PBL-SCID mice against challenge by primary isolates of HIV-1. Nat. Med. 3:1389-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannecchini, S., D. Del Mauro, D. Matteucci, and M. Bendinelli. 2001. AIDS vaccination studies using an ex vivo feline immunodeficiency virus model: reevaluation of neutralizing antibody levels elicited by a protective and a nonprotective vaccine after removal of antisubstrate cell antibodies. J. Virol. 75:4424-4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorelick, R. J., D. J. Chabot, D. E. Ott, T. D. Gagliardi, A. Rein, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur. 1996. Genetic analysis of the zinc finger in the Moloney murine leukemia virus nucleocapsid domain: replacement of zinc-coordinating residues with other zinc-coordinating residues yelds noninfectious particles containing genomic RNA. J. Virol. 70:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heilman, C. A., and D. Baltimore. 1998. HIV vaccines-where are we going? Nat. Med. 4:532-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hioe, C. E., M. Tuen, P. C. Chien, Jr., G. Jones, S. Ratto-Kim, P. J. Norris, W. J. Moretto, D. F. Nixon, M. K. Gorny, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 2001. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 presentation to CD4 T cells by antibodies specific for the CD4 binding domain of gp120. J. Virol. 75:10950-10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hohdatsu, T., S. Okada, K. Motokawa, C. Aizawa, J. K. Yamamoto, and H. Koyama. 1997. Effect of dual-subtype vaccine against feline immunodeficiency virus infection. Vet. Microbiol. 58:155-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosie, M. J., and O. Jarrett. 1999. Analysis of the protective immunity induced by feline immunodeficiency virus vaccination. Adv. Vet. Med. 41:325-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeng, C. R., R. V. English, T. Childers, M. B. Tompkins, and W. A. F. Tompkins. 1996. Evidence for CD8+ antiviral activity in cats infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 70:2474-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang, C.-Y., K. Hariharan, P. Nara, J. Sodroski, and J. P. Moore. 1994. Immunization with a soluble CD4-gp120 complex preferentially induces neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibodies directed to conformation-dependent epitopes of gp120. J. Virol. 68:5854-5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlas, J. A., K. H. J. Siebelink, M. A. van Peer, W. Huisman, A. M. Cuisinier, G. F. Rimmelzwaan, and A. D. M. E. Osterhaus. 1999. Vaccination with experimental feline immunodeficiency virus vaccines, based on autologous infected cells, elicits enhancement of homologous challenge infection. J. Gen. Virol. 80:761-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaCasse, R. A., K. E. Follis, M. Trahey, J. D. Scarborough, D. R. Littman, and J. H. Nunberg. 1999. Fusion-competent vaccines: broad neutralization of primary isolates of HIV. Science 283:357-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laube, L. S., M. Burrascano, C. E. Dejesus, B. D. Howard, M. A. Johnson, W. T. L. Lee, A. E. Lynn, G. Peters, G. S. Ronlov, K. S. Townsend, R. L. Eason, D. J. Jolly, B. Merchant, and J. F. Warner. 1994. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte and antibody responses generated in rhesus monkeys immunized with retroviral vector-transduced fibroblasts expressing human immunodeficiency virus type-1 IIIB ENV/REV proteins. Hum. Gene Ther. 5:853-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, S., K. Peden, D. S. Dimitrov, C. C. Broder, J. Manischewitz, G. Denisova, J. M. Gershoni, and H. Golding. 1997. Enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-mediated fusion by a CD4-gp120 complex-specific monoclonal antibody. J. Virol. 71:6037-6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lombardi, S., C. Massi, E. Indino, C. La Rosa, P. Mazzetti, M. L. Falcone, P. Rovero, A. Fissi, O. Pieroni, P. Bandecchi, F. Esposito, F. Tozzini, M. Bendinelli, and C. Garzelli. 1996. Inhibition of feline immunodeficiency virus infection in vitro by envelope glycoprotein synthetic peptides. Virology 220:274-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luscher, M. A., C. S. Dela Cruz, K. S. MacDonald, and B. H. Barber. 1998. Concerning the anti-major histocompatibility complex approach to HIV type 1 vaccine design. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:541-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matteucci, D., M. Pistello, P. Mazzetti, S. Giannecchini, D. Del Mauro, I. Lonetti, L. Zaccaro, C. Pollera, S. Specter, and M. Bendinelli. 1997. Studies of AIDS vaccination using an ex vivo feline immunodeficiency virus model: protection conferred by a fixed-cell vaccine against cell-free and cell-associated challenge differs in duration and is not easily boosted. J. Virol. 71:8368-8376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matteucci, D., M. Pistello, P. Mazzetti, S. Giannecchini, D. Del Mauro, L. Zaccaro, P. Bandecchi, F. Tozzini, and M. Bendinelli. 1996. Vaccination protects against in vivo-grown feline immunodeficiency virus even in the absence of detectable neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 70:617-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matteucci, D., M. Pistello, P. Mazzetti, S. Giannecchini, P. Isola, A. Merico, L. Zaccaro, A. Rizzuti, and M. Bendinelli. 1999. AIDS vaccination studies using feline immunodeficiency virus as a model: immunization with inactivated whole virus suppresses viraemia levels following intravaginal challenge with infected cells but not following intravenous challenge with cell-free virus. Vaccine 18:119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matteucci, D., A. Poli, P. Mazzetti, S. Sozzi, F. Bonci, P. Isola, L. Zaccaro, S. Giannecchini, M. Calandrella, M. Pistello, S. Specter, and M. Bendinelli. 2000. Immunogenicity of an anti-clade B feline immunodeficiency fixed-cell virus vaccine in field cats. J. Virol. 74:10911-10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazzetti, P., S. Giannecchini, D. Del Mauro, D. Matteucci, P. Portincasa, A. Merico, C. Chezzi, and M. Bendinelli. 1999. AIDS vaccination studies using an ex vivo feline immunodeficiency virus model: detailed analysis of the humoral immune response to a protective vaccine. J. Virol. 73:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montefiori, D. C., and J. P. Moore. 1999. Magic of the occult? Science 283:336-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore, J. P., and D. R. Burton. 1999. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: how full is the bottle? Nat. Med. 5:142-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore, J. P., P. W. H. I. Parren, and D. Burton. 2001. Genetic subtypes, humoral immunity, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine development. J. Virol. 75:5721-5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nabel, G. J. 2001. Challenges and opportunities for development of an AIDS vaccine. Nature 410:1002-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nathanson, N., and B. J. Mathieson. 2000. Biological considerations in the development of a human immunodeficiency virus vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 182:579-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nunberg, J. H., K. E. Follis, M. Trahey, and R. A. LaCasse. 2000. Turning a corner on HIV neutralization? Microbes Infect. 2:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overbaugh, J., A. D. Miller, and M. V. Eiden. 2001. Receptors and entry cofactors for retroviruses include single and multiple transmembrane-spanning proteins as well as newly described glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored and secreted proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:371-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parren, P. W. H. I., P. A. Marx, A. J. Hessell, A. Luckay, J. Harouse, C. Cheng-Mayer, J. P. Moore, and D. R. Burton. 2001. Antibody protects macaques against vaginal challenge with a pathogenic R5 simian/human immunodeficiency virus at serum levels giving complete neutralization in vitro. J. Virol. 75:8340-8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parren, P. W. H. I., J. P. Moore, D. R. Burton, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1999. The neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1: viral evasion and escape from humoral immunity. AIDS 13:S137-S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pedersen, N. C., E. W. Ho, M. L. Brown, and J. K. Yamamoto. 1987. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic virus from domestic cats with an immunodeficiency-like syndrome. Science 235:790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pistello, M., A. Morrica, F. Maggi, M. L. Vatteroni, G. Freer, C. Fornai, F. Casula, S. Marchi, P. Ciccorossi, P. Rovero, and M. Bendinelli. 2001. TT virus levels in the plasma of infected individuals with different hepatic and extrahepatic pathology. J. Med. Virol. 63:189-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pu, R., J. Coleman, M. Omori, M. Arai, T. Hohdatsu, C. Huang, T. Tanabe, and J. K. Yamamoto. 2001. Dual-subtype FIV vaccine protects cats against in vivo swarms of both homologous and heterologous subtype FIV isolates. AIDS 15:1225-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reed, L. J., and H. A. Münch. 1938. A simple method for estimating fifty percent end points. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richardson, J., G. Pancino, R. Merat, T. Leste-Lasserre, A. Moraillon, J. Schneider-Mergener, M. Alizon, P. Sonigo, and N. Heveker. 1999. Shared usage of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by primary and laboratory-adapted strains of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 73:3661-3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rossio, J. L., M. T. Esser, K. Suryanarayana, D. K. Schneider, J. W. Bess, Jr., G. M. Vasquez, T. A. Wiltrout, E. Chertova, M. K. Grimes, Q. Sattentau, L. O. Arthur, L. E. Henderson, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J. Virol. 72:7992-8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spenlehauer, C., A. Kirn, A.-M. Aubertin, and C. Moog. 2001. Antibody-mediated neutralization of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: investigation of the mechanism of inhibition. J. Virol. 75:2235-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stott, E. J., and G. C. Schild. 1996. Strategies for AIDS vaccines. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:185-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talbott, R. L., E. E. Sparger, K. M. Lovelace, W. M. Fitch, N. C. Pedersen, P. A. Luciw, and J. H. Elder. 1989. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of feline immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5743-5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thali, M., J. P. Moore, C. Furman, M. Charles, D. D. Ho, J. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 1993. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J. Virol. 67:3978-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tremblay, M. J., J.-F. Fortin, and R. Cantin. 1998. The acquisition of host-encoded proteins by nascent HIV-1. Immunol. Today 19:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tummino, P. J., J. D. Scholten, P. J. Harvey, T. P. Holler, L. Maloney, R. Gogliotti, J. Domagala, and D. Hupe. 1996. The in vitro ejection of zinc from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 nucleocapsid protein by disulfide benzamides with cellular anti-HIV activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:969-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang, Y. F., L. Tao, E. Mitchell, C. Bravery, P. Berlingieri, P. Armstrong, R. Vaughan, J. Underwood, and T. Lehner. 1999. Allo-immunization elicits CD8+ T cell-derived chemokines, HIV suppressor factors and resistance to HIV infection in women. Nat. Med. 5:1004-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willett, B. J., J. N. Flynn, and M. J. Hosie. 1997. FIV infection of the domestic cat: an animal model for AIDS. Immunol. Today 18:182-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willett, B. J., L. Picard, M. J. Hosie, J. D. Turner, K. Adema, and P. R. Clapham. 1997. Shared usage of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by the feline and human immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 71:6407-6415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wyatt, R., and J. Sodroski. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamamoto, J. K., T. Hohdatsu, R. A. Olmsted, R. Pu, H. Louie, H. A. Zochlinski, V. Acevedo, H. M. Johnson, G. A. Soulds, and M. B. Gardner. 1993. Experimental vaccine protection against homologous and heterologous strains of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 67:601-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto, J. K., T. Okuda, C. D. Ackley, H. Louie, E. Pembroke, H. Zochlinski, R. J. Munn, and M. B. Gardner. 1991. Experimental vaccine protection against feline immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 7:911-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang, X., R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Improved elicitation of neutralizing antibodies against primary human immunodeficiency viruses by soluble stabilized envelope glycoprotein trimers. J. Virol. 75:1165-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.York, J., K. E. Follis, M. Trahey, P. N. Nyambi, S. Zolla-Pazner, and J. H. Nunberg. 2001. Antibody binding and neutralization of primary and T-cell line-adapted isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:2741-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]