Abstract

Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) in human heart transplantation is an immunopathologic process in which injury to the graft is in part the result of activation of complement and it is poorly responsive to conventional therapy. We evaluated by immunofluorescence (IF), 665 consecutive endomyocardial biopsies from 165 patients for deposits of immunoglobulins and complement. Diffuse IF deposits in a linear capillary pattern greater than 2+ were considered significant. Clinical evidence of graft dysfunction was correlated with complement deposits. IF 2+ or higher was positive for IgG, 66%; IgM, 12%; IgA, 0.6%; C1q, 1.8%; C4d, 9% and C3d, 10%. In 3% of patients, concomitant C4d and C3d correlated with graft dysfunction or heart failure. In these 5 patients AMR occurred 56–163 months after transplantation, and they responded well to therapy for AMR but not to treatment with steroids. Systematic evaluation of endomyocardial biopsies is not improved by the use of antibodies for immunoglobulins or C1q. Concomitant use of C4d and C3d is very useful to diagnose AMR, when correlated with clinical parameters of graft function. AMR in heart transplant patients can occur many months or years after transplant.

Keywords: Antibody-mediated rejection, C3d, C4d, complement, heart transplant, macrophages

Introduction

Transplants are capable of eliciting strong cellular and humoral immune responses (1). In general, the effects of the cellular arm of the immune response can be controlled in an adequate manner by current immunosuppressive therapy. Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) in human heart transplantation is an immunopathologic process in which injury to the graft is in part the result of activation of complement and it is poorly responsive to conventional therapy. However, the role of the humoral arm of the immune response is not fully understood. The features that allow the identification of this entity on endomyocardial biopsies are not defined in the current working formulation of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) for the diagnosis of cardiac allograft rejection (2). Recently, there has been consensus among pathologists and clinicians that AMR is a real entity (3). However, the incidence and prevalence of AMR have not been documented in cardiac transplants using newer and more sensitive markers in tissue, and a unified set of diagnostic criteria of AMR in biopsies or explanted hearts has not been established (3). Some studies have defined light microscopic findings attributed to AMR (4,5), but at the Banff Conference on Allograft Pathology it was clear that the experience in making this diagnosis is sparse and there is no reproducibility of criteria among heart transplant centers as to what constitutes AMR. Pathologic markers of AMR identifiable in endomyocardial biopsy tissue suggested for study included IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3d and C4d. (3).

On the basis of this discussion, we analyzed endomyocardial biopsies in our cardiac pathology service. In this article, we report the incidence of AMR at a single center. This center was found to have a low incidence, but AMR was identified as a real clinical entity that may appear years after transplantation. AMR produced clinical dysfunction of the graft that was potentially fatal, but could be controlled with a therapy directed to the humoral immunity. Newer, more sensitive immunopathologic markers such as monoclonal antibodies for the activated complement split products C4d and C3d are clearly shown to be superior to other markers, and very specific when interpreted along with the clinical signs at the time of the biopsy.

Materials and Methods

Six hundred and sixty-five consecutive endomyocardial biopsies from cardiac allograft recipients received in the cardiac pathology service of the Johns Hopkins Hospital were studied prospectively from January 2001 to December 2003. For standard clinical evaluation we usually receive four or more pieces of formalin-fixed tissue for light microscopy and one frozen piece for immunofluorescence (IF). The light microscopy examination of the biopsies was graded according to the Working Formulation (2).

The frozen biopsies were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). The frozen sections were dried and fixed in acetone (4°C) for 10 min and rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice for 5 min. Normal goat serum (10% in PBS) was used as a blocking agent. IF microscopy was performed using the direct method for IgG, IgM, IgA and C1q (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA ), incubating for 35 min in a humid chamber. The indirect IF method was used for complement components C4d (1:40 in PBS) and C3d (1:20 in PBS) using monoclonal antibodies against these complement activation split products (Quidel, Santa Clara, CA). Fluorescein isothicyanate (FITC) conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) was used as the secondary antibody at 1:100 dilution in PBS with a 30-min incubation followed by two 5-min rinses in PBS. A Positive control (fibrinogen) and negative control (normal mouse IgG1 1:20 in PBS) were used in each case.

The IF stains were scored, in a semi-quantitative fashion from grades 0 to 4+, independently by two pathologists at the time of evaluation of these biopsies during patient care activities. Inter-observer variability did not occur in any case with a score above 2+. The location (pericapillary, perimyocytic) and pattern (linear, granular) were recorded. Clinical information including age, gender, race, time after transplantation, surgery for assist devices, retransplantation, results of panel reactive antibody screening (PRA), heart rate, blood pressure, right atrial pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, ejection fraction and cytomegalovirus serology was obtained from the Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplant database at the time of the biopsy and recorded in an anonymized electronic spreadsheet database created for this study (Excel, Microsoft Co., Redmond, WA)

Immunohistochemical stains for the monocyte/macrophage marker CD68 were performed retrospectively on paraffin sections of the same biopsy material that was evaluated by light microscopy in all the cases that had positive IF >2+ for C4d and C3d.

Anti-HLA class I and class II were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Donor-specific antibodies (DSA) were tested by flow beads with specific HLA antigens as targets; specifically, GTI Quik-ID™ and GTI Quick-ID ClassII™ (GTI Diagnostics, Waukesha, WI) assays were utilized. All titers for DSA represent IgG antibodies. (6)

Patients

Consecutive endomyocardial biopsies (n = 665) from 165 adult patients were studied. These represent all the patients transplanted and followed at our center. This included 107 males and 58 females (a ratio of 2.5:1) with an average age of 49.6 and 49 years respectively, at an average of 88.8 and 72.4 months after transplantation respectively. Of the 165 patients, 34 were newly transplanted during the period of study.

Results

Immunoglobulins

IF staining for immunoglobulin deposits with an intensity of 2+ or higher was found in approximately 30% of all biopsies (Table 1). Over 70% of the patients had immunoglobulin deposits on one or more biopsies at different times. IgG was the most frequent reactant (Table 1), but it was often deposited in a perimyocytic pattern. IgM and IgA deposits were detected less frequently, and usually had a focal or granular pattern in capillaries.

Table 1.

Immunofluorescence positive >2+ in 665 endomyocardial biopsies (EMB) from 165 patients

| IgG | IgM | IgA | C1q | C4d | C3d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMB | 176 (26.4%) | 21 (3.1%) | 7 (0.15%) | 3 (0.45%) | 27 (4%) | 27 (4%) |

| Patients | 110 (66.6%) | 20 (12.1%) | 6 (0.6%) | 3 (1.8%) | 16 (9.6%) | 17 (10.3%) |

Complement

Table 2 shows that complement activation was detected at a 2+ or higher intensity in the tissue from about 10% of patients. There was a small percentage of C1q positive biopsies. The split products C4d and C3d were present in roughly 4% of all biopsies and 9–10% of patients. The IF patterns of deposits of different complement components are shown in Figure 1. The typical pattern seen in AMR was a linear pattern of fluorescence, which was discretely localized to the capillary endothelial cells (Figure 1). It was also seen in arterial endothelium, when arterioles were present in the biopsy. This pattern of fluorescence was identical for C4d and C3d, with the caveat that C3d was occasionally more intense. The linear deposits of complement in capillaries became weaker and eventually disappeared as a function of time in those patients who received therapy for AMR (7).

Table 2.

Immunofluorescence deposits of C4d, C3d or both in endomyocardial biopsies (EMB) from patients with and without clinical signs of clinical dysfunction of the allograft (CDA) or second heart transplants (2nd Tx)

| AMR Patient | DSA | C4d > 2+ | C3d > 2+ | C4d and C3d | AMR by IF + CDA | Intravascular macrophages | 2nd Tx | ISHLT grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103* | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1B |

| 99* | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1A |

| 17* | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| 65* | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | 1B |

| 60* | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 1A |

| 98 | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | 1A |

| 139 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 1A |

| 42 | ND | + | + | + | − | − | − | 1A |

| 131 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 0 |

| 105 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 1A |

| 30 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 1A |

| 108 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 1A |

| 40 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 0 |

| 153 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| 4 | ND | + | − | − | − | − | − | 1A |

| 126 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | 1A |

| 119 | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | 1A |

| 38 | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| 3 | ND | − | + | − | − | − | − | 1A |

| 34 | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | 1A |

| 16 (9.6%) | 17 (10.3%) | 13 (7.8%) | 5 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 4 |

Patient had clinical graft dysfunction.

DSA = Donor-specific antibody (ND = Not done); AMR = Antibody-mediated rejection; CDA = Clinical dysfunction of the allograft; 2nd Tx = Patient received a second heart transplant and AMR is present in the second heart.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of a heart biopsy from patient 5 in Table 3, 68 months after heart transplant during the episode of antibody-mediated rejection plotted in Figure 2A. IgM deposits (3+) are present in granular pattern around capillaries. Note the absence of deposits in perimyocyte location. (60×) (FITC anti-IgM). C1q deposits are barely detectable in the capillaries (60×) (FITC anti-C1q). C4d staining shows intense linear deposits in the capillary endothelium (cross sections as well as longitudinally oriented capillaries are shown) (60×) (FITC anti-C4d). C3d deposition is clearly positive in same linear pattern around capillaries, identical to that shown for the C4d deposits. (60×) (FITC anti-C3d).

Table 2 shows the complement deposition results for 20 patients of 165 (representing 12% of the total population studied), who had unambiguous complement deposits of C4d or C3d greater than 2+ in diffuse, linear capillary pattern in their biopsies. Thirteen patients (about 8%) had deposits of both C4d and C3d. Three patients (2.1%) had deposits of C4d only and 4 patients (2.4%) had deposits of C3d only.

Clinical data for transplants with complement deposits

Only 5 of 20 patients with complement deposition in their endomyocardial biopsies (EMB) had concurrent clinical evidence of hemodynamic compromise (shock, hypotension, decreased cardiac output/index and/or rise in capillary wedge pressure or pulmonary artery pressure) (Figure 2). The other 15 patients with complement deposits in their biopsies did not have any clinical symptom of dysfunction of the allograft at the time of biopsy.

Figure 2.

Example of developing antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) in a heart transplant patient (patient 1 from Table 3). (A) At 52 months after her 2nd transplant the ejection fraction (EF) began to drop. At 59 weeks while the EF continued to decrease, there was an increase in right atrial pressure (RA) and pulmonary capillary wedge pressures (PCW). (B) At this time there was also a change in the complement deposition grading in her endomyocardial biopsies and donor-specific antibodies were documented in this patient, which overlapped in time with the C4d and C3d deposits in the Endomyocardial biopsy. Thus, the hemodynamic changes correlate with pathologic evidence of AMR

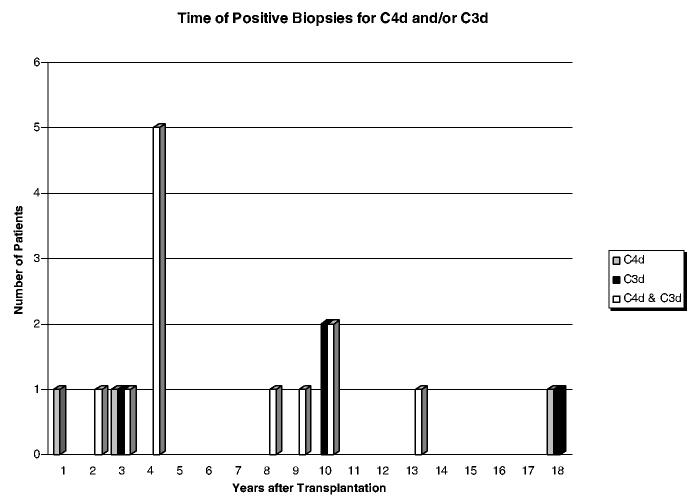

Although 34 of 165 patients were followed from the time of transplantation and there were an average of eight endomyocardial biopsies evaluated from the first 6 months after transplantation in this study, complement deposits and concomitant clinical dysfunction were late events in all the patients, occurring 60–163 months after transplantation. Figure 3 shows a plot of the 20 patients who had complement deposits. The appearance of complement deposits is plotted from the time of transplantation. Table 3 shows specific times in months after transplantion when the complement deposits were found. It also shows that there was no relationship to gender or ethnicity. As shown in Table 2 five patients received second heart transplants, three of whom developed AMR with graft dysfunction and two patients had complement deposits but no graft dysfunction. One patient had received a ventricular assist device and he had 10% panel reactive antibody profile pre-transplantation. All five patients underwent plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy with positive responses. Three patients had antibodies to donor-specific HLA antigens concurrent with C4d and C3d deposition and graft dysfunction. Two patients did not have detectable antibodies to donor-specific HLA antigens and required anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy (Rituximab) to control relapsing AMR.

Figure 3.

Time of appearance of complement deposits in endomyocardial biopsies counted from the time of transplantation.

Table 3.

Serology for donor-specific antibodies, ventricular assistance as risk factor and treatment for antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) in 20 patients with complement deposits

| AMR patient | Month after transplantation | Gender | PRA | No sera | DSA done | DSA + | Specificity | VAD | Pheresis | IVIG | Ritux |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 223 | F | − | + | |||||||

| 4 | 218 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 17* | 163 | M | − | + | + | A2 B8 | + | + | |||

| 30 | 131 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 34 | 126 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 38 | 122 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 40 | 120 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 42 | 116 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 60* | 97 | M | 10% | + | + | DR7*, DRw53 | + | + | + | ||

| 65* | 93 | F | − | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 98 | 60 | F | − | + | |||||||

| 99* | 60 | F | − | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 103* | 60 | F | − | + | + | A26, DR5, B44, B45, DRx52 | + | + | |||

| 105 | 55 | F | − | + | |||||||

| 108 | 52 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 119 | 44 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 126 | 39 | F | − | + | |||||||

| 131 | 36 | M | − | + | + | ||||||

| 139 | 27 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 153 | 15 | M | − | + | |||||||

| 4 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 |

Patient had clinical graft dysfunction.

F = Female; M = Male; PRA = Panel Reactive antibodies; DSA = Donor-Specific Antibody; VAD = Ventricular assist device (pre-transplant); Pheresis = Plasmapheresis; IVIG = Intravenous immunoglobulin; Ritux = Rituximab.

Macrophages in biopsies

In the present study all 5 patients who had complement deposition of C4d and C3d and clinical evidence of dysfunction, also had prevalent intravascular macrophages in the paraffin embedded tissue from the same biopsy procedure (Table 2). Interstitial macrophages were also found in cases of AMR and in almost every case with a ISHLT cellular rejection grade of 1A of higher.

Clinical follow-up

Table 4 shows clinical follow-up in the 20 patients who had complement deposits of C4d or C3d that were graded >2+. Eight patients (40%) developed cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV). Four of the 5 patients with AMR (C4d and C3d deposits coinciding with graft dysfunction) developed CAV, while only 4 of the 15 other patients with C4d and/or C3d deposit developed CAV. Excluding CAV, there has been no evidence of graft dysfunction or hemodynamic compromise (shock, hypotension, decreased cardiac output/index and/or a rise in capillary wedge or pulmonary artery pressure) since the treatment for AMR in the living patients.

Table 4.

Follow-up of 20 patients with complement deposits

| Patient | Alive | Dead | Cause of death | CAV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | + | |||

| 4 | + | CAV | + | |

| 17* | + | Stroke | ||

| 30 | + | + | ||

| 34 | + | |||

| 38 | + | Lymphoma | ||

| 40 | + | |||

| 42 | + | |||

| 60* | + | + | ||

| 65* | + | + | ||

| 98 | + | |||

| 99* | + | CAV | + | |

| 103* | + | CAV | + | |

| 105 | + | |||

| 108 | + | |||

| 119 | + | CAV | + | |

| 126 | + | |||

| 131 | + | |||

| 139 | + | + | ||

| 153 | + | |||

| 14 | 6 | 8 |

Patient had clinical graft dysfunction.

CAV = Cardiac allograft vasculopathy.

Cytolytic therapy

Table 5 shows that 3 patients with complement deposits and allograft dysfunction had received ortho anti-T-cell monoclonal (OKT3) induction at the time of transplantation (i.e. many months before AMR became a clinical problem). One of these patients also received horse anti-thymocyte globulin. Finally, 1 additional patient out of 20, showed C3d deposits in one biopsy 233 months after transplant.

Table 5.

Cytolytic therapy in patients with complement deposits

| Patient | ATgam | OKT3 | RATG |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | + | + | + |

| 4 | |||

| 17* | + | + | + |

| 30 | |||

| 34 | + | ||

| 38 | |||

| 40 | + | ||

| 42 | |||

| 60* | |||

| 65* | |||

| 98 | + | ||

| 99* | + | ||

| 103* | + | ||

| 105 | |||

| 108 | |||

| 119 | |||

| 126 | |||

| 131 | |||

| 139 | |||

| 153 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 2 |

Patient had clinical graft dysfunction.

ATgam = horse anti-thymocyte globulin; OKT3 = ortho anti-T-cell monoclonal; RATG = rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin.

Discussion

AMR has been also called vascular humoral rejection (8). This type of rejection has been reported to occur most frequently within the first month after transplant and to affect most notably the components of the capillary network of the heart (8). Due to the lack of standardized criteria for the evaluation of AMR (3), we sought to evaluate in a prospective unbiased manner the usefulness of diagnostic tools previously used in the diagnosis of AMR such as immunoglobulins and C1q, and also to use more sensitive reagents such as antibodies to C4d and C3d. Our data show that the most useful tools are C3d and C4d IF. In the renal transplant literature, C4d staining has been considered an independent predictor of kidney graft dysfunction, and a reliable specific marker for antibody-dependent graft injury (9).

There are only limited reports of the pathological findings of AMR in cardiac allografts using currently available reagents for immunohistology in a large cohort of biopsies from a single transplant center. The present study included 665 consecutive endomyocardial biopsies from 165 patients followed at a single center. We established a stringent definition of AMR using combined clinical and immunopathological criteria. In order to meet these criteria a patient needed to have clinical evidence of cardiac dysfunction (elevated right atrial pressure or capillary wedge pressure) or heart failure (a significant drop of ejection fraction) and immunopathological evidence of complement activation in the biopsy (deposition of C4d and/or C3d).

Only 20 patients had deposition of C1q, C4d and/or C3d in their endomyocardial biopsies. One of the 34 patients studied from the time of transplantation had C4d or C3d deposits in the biopsies within the first year after transplantation. This is distinct from two other studies in which C4d deposition was examined as a marker for AMR (10,11). This discrepancy may be explained in part by the differences in patient populations. Most of our patients had no evidence of sensitization (0% PRA) and few of our patients had left ventricular assist devices in place prior to transplantation as shown in Table 4. However, three of the five patients, who experienced AMR, had received a second heart (Table 2).

The five patients who met the criteria of concurrent clinical and immunopathological evidence of AMR, had completed 56–163 months after transplantation at the time of diagnosis. Further support for the diagnosis of AMR was the demonstration of antibodies to donor-specific HLA antigens in three of these patients, and the beneficial effect of treatment with plasmapheresis and IVIG in all the five patients. In addition, all the five patients were demonstrated to have prevalent intra-vascular CD68-positive macrophages in their biopsies (Table 2). This feature of AMR has been identified by two groups (4,12) as well as anecdotally (7). Other light microscopic features described in the literature including capillary endothelial cell swelling, vasculitis, hemorrhage and neutrophilic infiltrates (4) were not common findings. Similarly, the presence of immunoglobulins (IgM, IgG or IgA) was not helpful in the diagnosis in that deposits of these proteins were frequently found, but their localization rarely coincided with the complement components studied.

All the five patients that met our criteria for AMR had both C4d and C3d deposits in a diffuse linear pattern on the capillary endothelium in their biopsies at the time of diagnosis. Fifteen other patients had C4d and/or C3d deposition in a similar pattern in their biopsies: 8 patients had both C4d and C3d depositions, while 3 patients had only C4d and 4 patients had only C3d deposits. It is possible that these 15 patients had ‘subclinical antibody mediated rejection’ (13). C4d deposition has been reported by two groups in ABO incompatible renal transplants in the presence of low levels of circulating hemagglutinin antibodies and no evidence of graft dysfunction has been reported (14-16). It has been suggested that complement regulatory proteins can successfully terminate the complement cascade after activation in these renal transplants to achieve a state of accommodation (17-19). Thus the mere presence of complement deposition should not be equated with AMR. Like the patients with accommodated renal transplants, our patients with C4d and/or C3d deposits in the absence of cardiac allograft dysfunction did not require any therapy for rejection. Indeed, it has been shown in kidney transplants that some patients do not have dysfunction of the allograft despite the presence of C4d deposition (20,21) Furthermore, these investigators have documented the presence of CD59 and CD55 (decay accelerating factor) in these biopsies, which can function to prevent injury to the graft (21). Whether or not the presence of complement deposits in asymptomatic patients represents accommodation or sub-clinical AMR cannot be answered by this study. However, there was less evidence of long-term consequences of complement deposition in asymptomatic patients. Four of the 5 patients meeting the criteria for AMR developed CAV, whereas only 4 of 15 patients with C4d and/or C3d deposits in the absence of concurrent graft dysfunction developed CAV.

Our study provides, for the first time, the information of systematic determination of complement deposits in a prospective manner, in a population of nonsensitized heart transplant recipients as judged by pre-transplant PRA's. About 10% of our patients showed evidence of complement deposition in their biopsy specimens, but only 3% had complement deposition and clinical dysfunction of the graft. This is a much lower percentage than reported in other retrospective or selective studies of cardiac or renal transplant patients (22,23). Our findings are similar to the data reported from a multicenter study of protocol biopsies from renal transplant recipients (24,25). Moreover, this multicenter study of renal biopsies reported that centers with a high proportion of sensitized patients found a greater incidence of C4d positivity.

One feature that distinguishes our patient population is the fact that pre-sensitization by ventricular assist device implantation was not common. In addition, none of the patients in this series received therapy with horse anti-thymocyte globulin during the study period, which we have found is correlated with C4d and C3d deposition in endomyocardial biopsies (26).

Another striking feature in our patient population is the fact that AMR occurred years after transplantation; this finding of late de novo AMR is also more common in renal transplant patients in centers with low proportions of sensitized recipients (24).

Three of our five patients with AMR and clinical dysfunction of the graft had donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies. This is concordant with other studies in which AMR correlates well with the presence of anti-HLA antibodies in the serum (27). In this study, serum specimens were obtained within an average of 1.8 days around the time of biopsy and analyzed for anti-HLA antibodies. Done in this manner, there was very good correlation between the presence of these antibodies and the finding of linear deposits of immunoglobulins or complement components in the biopsies (26). However, two of our five patients with AMR and dysfunction had no donor-specific anti-HLA. Thus the identification of other molecules such as endothelial (28) or other cellular antigens (29,30) as the targets of the antibodies responsible for AMR is a very important future task.

In the present study, we did not find a correlation between early ischemic injury and complement deposits as a predictor of subsequent episodes of rejection (31). This may reflect changes in the clinical practice such as the use of improved preservation solutions and harvesting procedures.

In summary, our data indicate that, when combined with clinical information, the detection of C4d and C3d deposits in endomyocardial biopsies is useful in the diagnosis of AMR even late after transplantation. However, the finding of complement deposition in an endomyocardial biopsy per se does not mean that the patient has AMR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the grants of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute P01HL056091, R01AI042387 and P01HL070295

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online:

Table S1. Patient demographics, serology for donor-specific antibodies.

References

- 1.Baldwin WM, III, Halloran PF. Antibody-mediated rejection. In: Racusen LC, Solez K, Burdick JF, editors. Kidney transplant rejection. Marcel Decker; New York: 1998. pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billingham ME, Cary NR, Hammond ME, et al. Heart Rejection Study Group The International Society for Heart Transplantation A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart and lung rejection. J Heart Transplant. 1990;9:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez ER. The pathology of heart transplant biopsy specimens: revisiting the 1990 ISHLT working formulation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lones MA, Czer LS, Trento A, Harasty D, Miller JM, Fishbein MC. Clinical-pathologic features of humoral rejection in cardiac allografts: a study in 81 consecutive patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14(1 Pt 1):151–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaels PJ, Espejo ML, Kobashigawa J, et al. Humoral rejection in cardiac transplantation: risk factors, hemodynamic consequences and relationship to transplant coronary artery disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:58–69. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zachary AA, Delaney NL, Lucas DP, Leffell MS. Characterization of HLA class I specific antibodies by ELISA using solubilized antigen targets: I. Evaluation of the GTI QuikID assay and analysis of antibody patterns. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:228–235. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duong Van Huyen JP, Fornes P, Guillemain R, et al. Acute vascular humoral rejection in a sensitized cardiac graft recipient: diagnostic value of C4d immunofluorescence. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond EH, Yowell RL, Nunoda S, et al. Vascular (humoral) rejection in heart transplantation: pathologic observations and clinical implications. J Heart Transplant. 1989;8:430–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohmig GA, Exner M, Habicht A, et al. Capillary C4d deposition in kidney allografts: a specific marker of alloantibody-dependent graft injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1091–1099. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1341091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behr TM, Feucht HE, Richter K, et al. Detection of humoral rejection in human cardiac allografts by assessing the capillary deposition of complement fragment C4d in endomyocardial biopsies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:904–912. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chantranuwat C, Qiao JH, Kobashigawa J, Hong L, Shintaku P, Fishbein MC. Immunoperoxidase staining for C4d on paraffin-embedded tissue in cardiac allograft endomyocardial biopsies: comparison to frozen tissue immunofluorescence. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2004;12:166–171. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200406000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratliff NB, McMahon JT. Activation of intravascular macrophages within myocardial small vessels is a feature of acute vascular rejection in human heart transplants. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14:338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takemoto SK, Zeevi A, Feng S, et al. National conference to assess antibody-mediated rejection in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1033–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren DS, Zachary AA, Sonnenday CJ, et al. Successful renal transplantation across simultaneous ABO incompatible and positive crossmatch barriers. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:561–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonnenday CJ, Ratner LE, Zachary AA, et al. Preemptive therapy with plasmapheresis/intravenous immunoglobulin allows successful live donor renal transplantation in patients with a positive cross-match. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1614–1616. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fidler ME, Gloor JM, Lager DJ, et al. Histologic findings of antibody-mediated rejection in ABO blood-group-incompatible living-donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:101–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6135.2003.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Platt JL. C4d and the fate of organ allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2417–2419. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000030140.74450.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JM, Holzknecht ZE, Plummer TB, Lin SS, Brunn GJ, Platt JL. Acute vascular rejection and accommodation: divergent outcomes of the humoral response to organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:1471–1478. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000140770.81537.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin WM, III, Kasper EK, Zachary AA, Wasowska BA, Rodriguez ER. Beyond C4d: other complement-related diagnostic approaches to antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiebeler A, Mengel M, Merkel S, Haller H, Schwarz A. Diffuse C4d deposition and morphology of acute humoral rejection in a stable renal allograft. Transplantation. 2003;76:1132–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000076468.64893.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornell LD, Colvin RB. Chronic allograft nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14:229–234. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000165888.83125.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemnitz J, Restrepo-Specht I, Haverich A, Cremer J. Acute humoral rejection: a new entity in the histopathology of heart transplantation. J Heart Transplant. 1990;9:447–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonnaud EN, Lewis NP, Masek MA, Billingham ME. Reliability and usefulness of immunofluorescence in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14:163–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poduval RD, Kadambi PV, Josephson MA, et al. Implications of immunohistochemical detection of C4d along peritubular capillaries in late acute renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2005;79:228–235. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000148987.13199.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mengel M, Bogers J, Bosmans JL. Incidence of C4d stain in protocol biopsies from renal allografts: results from a multicenter trial. Am J Transplantation. 2005;5:1050–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldwin WM, III, Armstrong LP, Samaniego-Picota M, et al. Antithymocyte globulin is associated with complement deposition in cardiac transplant biopsies. Human immunol. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.05.015. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cherry R, Nielsen H, Reed E, Reemtsma K, Suciu-Foca N, Marboe CC. Vascular (humoral) rejection in human cardiac allograft biopsies: relation to circulating anti-HLA antibodies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992;11(1 Pt 1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferry BL, Welsh KI, Dunn MJ, et al. Anti-cell surface endothelial antibodies in sera from cardiac and kidney transplant recipients: association with chronic rejection. Transpl Immunol. 1997;5:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(97)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose ML. Role of antibodies in transplant-associated cardiac allo-graft vasculopathy. Z Kardiol. 2000;89(Suppl 9):IX/11–IX/15. doi: 10.1007/s003920070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takenouchi T, Miyashita N, Ozutsumi K, Rose MT, Aso H. Role of caveolin-1 and cytoskeletal proteins, actin and vimentin, in adipo-genesis of bovine intramuscular preadipocyte cells. Cell Biol Int. 2004;28:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldwin WM, III, Samaniego-Picota M, Kasper EK, et al. Complement deposition in early cardiac transplant biopsies is associated with ischemic injury and subsequent rejection episodes. Transplantation. 1999;68:894–900. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199909270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.