Abstract

The capsid of herpes simplex virus has an icosahedral surface lattice with a nonskew triangulation number, T=16. Nevertheless, the proteins arrayed on this lattice necessarily have an intrinsic handedness. We have determined the handedness of both the herpes simplex virus type 1 capsid and its precursor procapsid by a cryoelectron microscopic tilting method.

Herpesviruses constitute an extensive family of viruses with linear genomes of double-stranded DNA ranging from ∼125 to ∼250 kbp with the same structural design. All of the herpesviruses identified to date have thick-walled icosahedral nucleocapsids, ∼1,250 Å in diameter, surrounded by a proteinaceous tegument and the viral envelope (12, 18, 20). They have the same triangulation number, T=16, that has yet to be observed in any other kind of virus, and the molecular architecture and complement of structural proteins appear to be closely conserved despite wide divergence at the amino acid sequence level.

The most detailed structural information available on herpesvirus capsids has emerged from cryoelectron microscopic reconstructions, initially of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (19) and equine herpes virus 1 (2) and now also covering cytomegalovirus, both the human (6) and simian (22) strains; Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (23, 26); and channel catfish virus (5). The capsid of HSV-1—and presumably of other herpesviruses as well—is first assembled as a precursor procapsid (15, 21) that differs markedly in structure, composition, and stability from the mature capsid. Three kinds of mature capsids, called A, B, and C capsids, may be isolated from the nuclei of infected cells, but they differ only with respect to contents, the surface shells being indistinguishable (4). For HSV-1 in particular, many aspects of capsid structure have been studied by cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) (e.g., references 16, 24, and 28), and these analyses have extended to progressively higher resolution (27). However, the handedness of the capsid has not been determined. Although T=16 is a nonskew triangulation number and therefore this lattice does not have levo and dextro enantiomorphs, the structure nevertheless has an intrinsic handedness that becomes apparent at resolutions higher than about 35 Å in such features as the orientation of the hexon protrusions, the asymmetric shape of the triplexes (heterotrimeric complexes at all threefold sites—local and icosahedral), and, on the inner surface, the shape of the opening to the axial channel that runs through each hexon (see Fig. 2 and 3). In our previous cryo-EM work on this system, we arbitrarily assigned a handedness in early studies and continued to observe this convention subsequently; other researchers have used the same assignment (e.g., references 7 and 27). We have now determined this property experimentally and found that the provisional assignment of handedness was, in fact, incorrect.

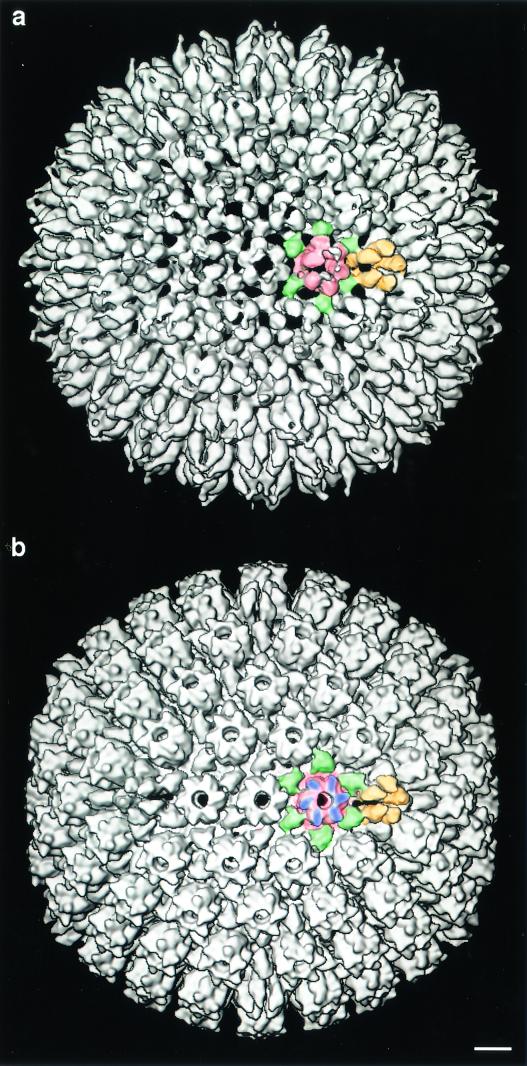

FIG. 2.

Outer surfaces of the HSV-1 procapsid (a) and mature capsid (b) with the correct handedness. The particles are viewed down an icosahedral twofold axis. A few examples of the molecules that make up the surface lattice (reviewed in reference 20) are color coded: six copies of major capsid protein VP5 (150 kDa) make up each hexon (red), and five copies of VP5 make up each penton (yellow). Each triplex (green) is a heterotrimer of VP19c (50 kDa; one copy) and VP23 (35 kDa; two copies). In the mature capsid (b), six copies of VP26 (12 kDa; blue) bind around the outer rim of each hexon but not to pentons. VP26 is not present on the procapsid (a). Handedness manifests itself in features such as the connections of the triplex proteins to the hexon and penton protrusions, the vorticity of the hexon caps (six copies of 12-kDa VP26) on the mature capsid, and the twist of the outward-protruding portions of the pentons and hexons. The images shown here and in Fig. 3 were recalculated from previously published data (17). Bar =100 Å.

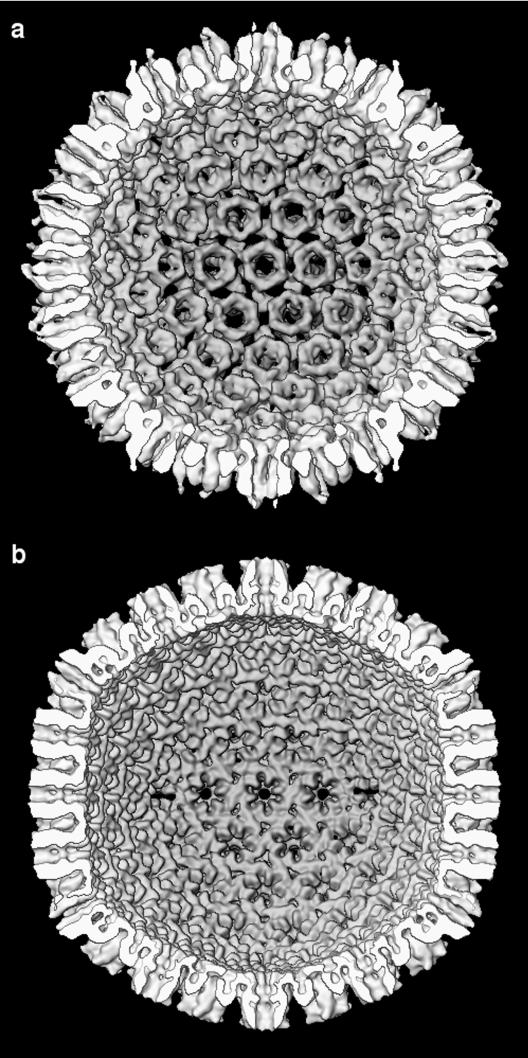

FIG. 3.

Inner surfaces of the HSV-1 procapsid (a) and mature capsid (b) with the correct handedness. The particles are viewed down an icosahedral twofold axis. The asymmetrical relationship of the triplexes to the hexons is evident on the procapsid but obscured in the mature capsid by the more continuous “floor.” The orientation of the sixfold orifice underlying the hexons (and pentons) exhibits handedness, particularly for the mature capsid.

An ambiguity in handedness arises in transmission EM because these images are projections and, a priori, it is ambiguous whether a particle in a given image has been viewed from the back or the front. In calculating a reconstruction, each image in the data set is matched with the corresponding reprojection of the current three-dimensional density map. In this way, handedness can be consistently assigned within a data set; however, it must still be determined which of the two possible hands is correct. Belnap et al. (3) developed a general method of handedness determination based on tilting, following from an earlier method (13). In this approach, particles are imaged twice—once at zero tilt and again after tilting of the specimen through a small angle—typically 5 or 10o—in a conventionally fixed direction. Reference models (density maps) are prepared for both enantiomers—the models can be preexisting, or they can be calculated from the zero-tilt data—and the orientation angles are determined for each particle in the data set (1). The two enantiomeric models are then rotated according to the experimental tilt, reprojected, and matched with the image of the tilted particle. A high correlation will be observed only with the correct enantiomer (e.g., Fig. 1). This procedure is repeated for each particle in the data set. Handedness is calibrated by passing a known structure through the procedure, identically applied. For this purpose, we used the Prohead II procapsid of bacteriophage HK97. This particle has a T=7 levo triangulation geometry as established both by this method, using polyomavirus as a reference (14), and by X-ray crystallography of the mature capsid (25).

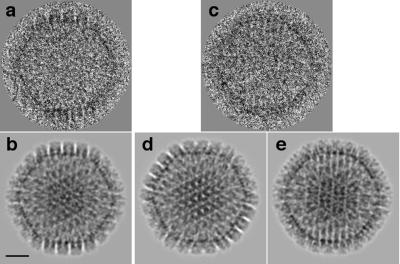

FIG. 1.

Example of matching of the correct enantiomeric model of HSV-1 capsid to a tilted cryo-EM image. (a) Micrograph of the untilted particle; (b) reprojection of the model(s) (enantiomers [A and B] give identical projections); (c) second exposure of the same particle tilted through 10o; (d) reprojection of model A, similarly rotated, giving a poor match with panel c; (e) reprojection of model B, similarly rotated, matching well with panel c. Bar = 250 Å.

HSV-1 m100 procapsids were prepared as previously described (17), as were A capsids (16). Samples were vitrified over holey carbon films and imaged at ×38,000 magnification on a CM200-FEG electron microscope (FEI, Mahwah, N.J.) as previously described (8). Micrographs were recorded at defocus settings such that the first contrast transfer function zeros were at frequencies of 20 to 25 Å−1. Micrographs were digitized on an SCAI scanner (Z/I Imaging, Huntsville, Ala.) at 7 μm/pixel and binned to give 21-μm pixels (5.53 Å at the specimen). Particles were extracted and preprocessed by using X3D (10). Initial estimates of the orientation angles were determined with the polar Fourier transform (PFT) algorithm (1), by using as starting models pre-existing maps of A capsids (11), procapsids (21), and Prohead II (9) scaled to match the current data. In each case, a density map was calculated and fed into several subsequent cycles of PFT-based refinement, leading to the final map. Handedness determination calculations were performed by using an updated implementation of the formalism described by Belnap et al. (3). This program, HAND, is available online at http://lsbr.niams.nih.gov. Data were analyzed to a frequency limit of 25 Å−1.

The results are summarized in Table 1. In the control experiment with HK97 Prohead II, hand A, which is the correct levo enantiomer, was consistently identified as such for all 86 particles in the data set. Duplicate independent determinations were performed with both HSV-1 mature capsids and procapsids. Model A had the handedness used in previous studies; model B was the opposite enantiomer. These data reproducibly reveal that hand B is correct for both the capsid and procapsid (Table 1). Even with the correct handedness, the correlation coefficients fell slightly for the tilted images, presumably as a consequence of incipient radiation damage and the focal gradient across the tilted micrographs. The correlation coefficients were systematically lower for the procapsid than for the capsid and Prohead II—this is simply an intrinsic property of this particle. As an additional control, to rule out inadvertent switching of the relative handedness of HK97 and HSV capsids at some step in the respective analyses, we performed an experiment in which the samples were mixed before imaging. The results obtained (Table 1, experiment 2) confirmed the other data.

TABLE 1.

Determination of HSV-1 capsid and procapsid handedness by correlation analysis of tilted electron micrographsa

| Expt no. | <CCu> ± SD (untilted) | Tilt angle (°) | NA | <CCA> ± SD (tilted model with hand A) | NB | <CCB> ± SD (tilted model with hand B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, A capsid | 0.391 ± 0.030 | 5 | 0 | 0.084 ± 0.034 | 69 | 0.347 ± 0.030 |

| 2, A capsid | 0.401 ± 0.045 | 10 | 0 | 0.051 ± 0.041 | 331 | 0.335 ± 0.051 |

| 2, HK97 Prohead II | 0.347 ± 0.041 | 10 | 63 | 0.301 ± 0.053 | 7 | 0.220 ± 0.033 |

| 3, Procapsid | 0.237 ± 0.057 | 5 | 1 | 0.056 ± 0.023 | 40 | 0.194 ± 0.062 |

| 4, Procapsid | 0.262 ± 0.029 | 10 | 0 | 0.034 ± 0.032 | 91 | 0.208 ± 0.042 |

| 5, HK97 Prohead II | 0.529 ± 0.042 | 5 | 86 | 0.436 ± 0.042 | 0 | 0.266 ± 0.050 |

Five sets of micrographs were analyzed (experiments 1 to 5). Experiment 2 was performed with a mixture of HSV-1 A capsids with HK97 Prohead II. Micrographs were first recorded without tilting the specimen and then after tilting it through 5 or 10°. <CCu> is the average correlation coefficient (1) for the untilted images with the corresponding reprojections from a three-dimensional map calculated from that data set. This coefficient has the same value for both models (the projection of the model with A handedness is identical to the projection of the model with B handedness after a 180° in-plane rotation). Appropriately tilted reprojections of both models were calculated and matched with the tilted images, giving correlation coefficients <CCA> and <CCB>, respectively. In each column is listed the number of particles (NA) for which <CCA> > <CCB> and vice versa for NB. In experiment 2, the correlation coefficients for the HK97 Prohead II particles are lower than those in experiment 5, reflecting somewhat lower quality data. As a result of the higher noise level in these images, 7 of 70 particles were misidentified with respect to handedness. Nevertheless, even this experiment gives a conclusive result: if the 70 particles were to be randomly assigned with respect to handedness, the expected partition would be 35 of each, with a standard deviations of ∼6 from counting statistics. Thus, the seven particles assigned handedness B in the experiment would represent a result that is almost 5 standard deviations (29/6) from the expected mean.

The outer and inner surfaces of the capsid and procapsid are shown with the correct handedness at 18 Å resolution in Fig. 2 and 3. It is noteworthy that the penton protrusions are very similar in both developmental states (Fig. 2), but the hexon protrusions, in addition to regularizing, undergo a gross rotation between the procapsid state and the mature state. In addition, a major remodeling of the floor layer takes place (21; Fig. 3). In previous studies, we have noted that the inner surface of the floor is closely conserved among different herpesviruses (Fig. 4 of reference 23). This feature could be used to cross-calibrate the handedness of other herpesviruses.

Knowledge of capsid handedness will be helpful as structural studies—which will likely include the docking of crystal structures of capsid proteins or fragments thereof into cryo-EM density maps—proceed to higher resolution. Since the crystal structures are expected to have the correct handedness, it is essential for the two kinds of data to be consistent in this respect.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Duda and R. Hendrix for providing HK97 Prohead II, J. Conway for a density map of Prohead II, J. B. Heymann for help with programming, and Z. Mark for help with writing the HAND program.

This work was supported in part by the NIH IATAP program (to A.C.S.) and grants NIH R-01 AI41644-04 and NSF MCB-9904879 to J.C.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, T. S., and R. H. Cheng. 1996. A model-based approach for determining orientations of biological macromolecules imaged by cryoelectron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 116:120-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, T. S., W. W. Newcomb, F. P. Booy, J. C. Brown, and A. C. Steven. 1990. Three-dimensional structures of maturable and abortive capsids of equine herpesvirus 1 from cryoelectron microscopy. J. Virol. 64:563-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belnap, D. M., N. H. Olson, and T. S. Baker. 1997. A method for establishing the handedness of biological macromolecules. J. Struct. Biol. 120:44-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booy, F. P., W. W. Newcomb, B. L. Trus, J. C. Brown, T. S. Baker, and A. C. Steven. 1991. Liquid-crystalline, phage-like, packing of encapsidated DNA in herpes simplex virus. Cell 64:1007-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booy, F. P., B. L. Trus, A. J. Davison, and A. C. Steven. 1996. The capsid architecture of channel catfish virus, an evolutionarily distant herpesvirus, is largely conserved in the absence of discernible sequence homology with herpes simplex virus. Virology 215:134-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butcher, S. J., J. Aitken, J. Mitchell, B. Gowen, and D. J. Dargan. 1998. Structure of the human cytomegalovirus B capsid by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction. J. Struct. Biol. 124:70-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, D., J. Jakana, D. McNab, J. Mitchell, Z. H. Zhou, M. Dougherty, W. Chiu, and F. J. Rixon. 2001. The pattern of tegument-capsid interactions in the herpes simplex virus type 1 virion is not influenced by the small hexon-associated protein VP26. J. Virol. 75:11863-11867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, N., J. F. Conway, N. R. Watts, J. F. Hainfeld, V. Joshi, R. D. Powell, S. J. Stahl, P. E. Wingfield, and A. C. Steven. 1999. Tetrairidium, a four-atom cluster, is readily visible as a density label in three-dimensional cryo-EM maps of proteins at 10-25 Å resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 127:169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conway, J. F., R. L. Duda, N. Cheng, R. W. Hendrix, and A. C. Steven. 1995. Proteolytic and conformational control of virus capsid maturation: the bacteriophage HK97 system. J. Mol. Biol. 253:86-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conway, J. F., B. L. Trus, F. P. Booy, W. W. Newcomb, J. C. Brown, and A. C. Steven. 1993. The effects of radiation damage on the structure of frozen hydrated HSV-1 capsids. J. Struct. Biol. 111:222-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway, J. F., B. L. Trus, F. P. Booy, W. W. Newcomb, J. C. Brown, and A. C. Steven. 1996. Visualization of three-dimensional density maps reconstructed from cryoelectron micrographs of viral capsids. J. Struct. Biol. 116:200-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homa, F. L., and J. C. Brown. 1997. Capsid assembly and DNA packaging in herpes simplex virus. Rev. Med. Virol. 7:107-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klug, A., and J. T. Finch. 1968. Structure of viruses of the papilloma-polyoma type. IV. Analysis of tilting experiments in the electron microscope. J. Mol. Biol. 31:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lata, R., J. F. Conway, N. Cheng, R. L. Duda, R. W. Hendrix, W. R. Wikoff, J. E. Johnson, H. Tsuruta, and A. C. Steven. 2000. Maturation dynamics of a viral capsid: visualization of transitional intermediate states. Cell 100:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb, W. W., F. L. Homa, F. P. Booy, D. R. Thomsen, B. L. Trus, A. C. Steven, J. V. Spencer, and J. C. Brown. 1996. Assembly of the herpes simplex virus capsid: characterization of intermediates observed during cell-free capsid formation. J. Mol. Biol. 263:432-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newcomb, W. W., B. L. Trus, F. P. Booy, A. C. Steven, J. S. Wall, and J. C. Brown. 1993. Structure of the herpes simplex virus capsid: molecular composition of the pentons and triplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 232:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newcomb, W. W., B. L. Trus, N. Cheng, A. C. Steven, A. K. Sheaffer, D. J. Tenney, S. K. Weller, and J. C. Brown. 2000. Isolation of herpes simplex virus procapsids from cells infected with a protease-deficient mutant virus. J. Virol. 74:1663-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rixon, F. J. 1993. Structure and assembly of herpesviruses. Semin. Virol. 4:135-144. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrag, J. D., B. V. Prasad, F. J. Rixon, and W. Chiu. 1989. Three-dimensional structure of the HSV1 nucleocapsid. Cell 56:651-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steven, A. C., and P. G. Spear. 1997. Herpesvirus capsid assembly and envelopment, p. 312-351. In W. Chiu, R. M. Burnett, and R. L. Garcea (ed.), Structural biology of viruses. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 21.Trus, B. L., F. P. Booy, W. W. Newcomb, J. C. Brown, F. L. Homa, D. R. Thomsen, and A. C. Steven. 1996. The herpes simplex virus procapsid: structure, conformational changes upon maturation, and roles of the triplex proteins VP19c and VP23 in assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 263:447-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trus, B. L., W. Gibson, N. Cheng, and A. C. Steven. 1999. Capsid structure of simian cytomegalovirus from cryoelectron microscopy: evidence for tegument attachment sites. J. Virol. 73:2181-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trus, B. L., J. B. Heymann, K. Nealon, N. Cheng, W. W. Newcomb, J. C. Brown, D. H. Kedes, and A. C. Steven. 2001. Capsid structure of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, a gammaherpesvirus, compared to those of an alphaherpesvirus, herpes simplex virus type 1, and a betaherpesvirus, cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 75:2879-2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trus, B. L., W. W. Newcomb, F. P. Booy, J. C. Brown, and A. C. Steven. 1992. Distinct monoclonal antibodies separately label the hexons or the pentons of herpes simplex virus capsid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:11508-11512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wikoff, W. R., L. Liljas, R. L. Duda, H. Tsuruta, R. W. Hendrix, and J. E. Johnson. 2000. Topologically linked rings of covalently joined protein subunits form the dsDNS bacteriophage HK97 capsid. Science 289:2129-2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu, L., P. Lo, X. Yu, J. K. Stoops, B. Forghani, and Z. H. Zhou. 2000. Three-dimensional structure of the human herpesvirus 8 capsid. J. Virol. 74:9646-9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou, Z. H., M. Dougherty, J. Jakana, J. He, F. J. Rixon, and W. Chiu. 2000. Seeing the herpesvirus capsid at 8.5 Å. Science 288:877-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou, Z. H., B. V. V. Prasad, J. Jakana, F. J. Rixon, and W. Chiu. 1994. Protein subunit structures in the herpes simplex virus capsid determined from 400-kV spot-scan electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 242:456-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]