Abstract

Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), the prototypic rhabdovirus, has a nonsegmented negative-sense RNA genome with five genes flanked by 3′ leader and 5′ trailer sequences. Transcription of VSV mRNAs is obligatorily sequential, starting from a single 3′ polymerase entry site, and termination of an upstream mRNA is essential for transcription of a downstream gene. cis-acting signals for transcription of VSV mRNAs are present within the leader region, at the leader-N junction, and at the internal gene junctions. The gene junctions of VSV consist of a conserved 23-nucleotide region that includes the gene end sequence of the upstream gene, 3′-AUACU7-5′, a nontranscribed intergenic dinucleotide, 3′-G/CA-5′, and the gene start sequence, 3′-UUGUCNNUAG-5′, at the beginning of the gene immediately downstream. Previous work has shown that the gene end sequence and intergenic region are sufficient to signal polyadenylation and termination of VSV transcripts. Mutagenesis of the gene start sequence has determined the importance of this region in the processes of initiation and 5′-end modification of mRNAs. However, because the gene end sequence is positioned directly upstream of the gene start sequence in the gene junction, and because of the requirement for termination of the upstream gene prior to transcription of the downstream gene, it has not been possible to investigate whether the gene end sequence contributes to transcription of the downstream gene. In this study, we inserted an additional gene end sequence upstream of the gene junction in a subgenomic replicon of VSV, which extended the intergenic region from 2 to 88 nucleotides. This duplication of termination signals allowed us to separate the signals required for termination from those required for initiation. We investigated the effect that the upstream gene end sequences had on downstream mRNA transcription. Our data show that the U7 tract of the upstream gene end sequence is necessary for optimal transcription of the downstream gene, independent of its role in termination of the upstream gene. Altering the sequence or changing the length of the U tract directly upstream of the gene start sequence significantly decreased transcription of the downstream gene. These results show that the U tract is a multifunctional region that is required not only for polyadenylation and termination of the upstream mRNA but also for efficient transcription of the downstream gene.

Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is the prototype member of the family Rhabdoviridae. The VSV genome consists of 11,161 nucleotides (nt) of negative-sense RNA that are tightly encapsidated by the nucleocapsid (N) protein (7). This ribonucleoprotein complex serves as the template for transcription and replication by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, the viral components of which are the large (L) and phospho- (P) proteins (11).

The VSV genome has five genes that are flanked by 3′ leader (le) and 5′ trailer (tr) regions in the order of 3′-le-N-P-M-G-L-tr-5′. Transcription of VSV mRNAs is controlled by the use of a single 3′ polymerase entry site (10) and obligatorily sequential transcription of the genome (1, 3). Additionally, a transcribing polymerase responds to cis-acting signals present within the leader region, at the leader-N junction, and at the internal gene junctions (5, 6, 13, 16, 25-27, 31, 33). The single 3′ transcriptional entry site on the genome dictates that the upstream genes are transcribed prior to the downstream genes, and it has been shown that termination of each upstream transcript is required for transcription of the downstream gene(s) (5, 6, 13). These observations taken together support a stop-start model of mRNA transcription for VSV (4). The abundance of the individual mRNAs reflects their order on the genome: N > P > M > G > L (1, 3, 29), as approximately 30% less of each downstream mRNA is synthesized compared with the upstream mRNA in a process referred to as transcriptional attenuation (14). Gene expression is thus controlled by the position of a given gene relative to the 3′ terminus of the genome by transcriptional attenuation, which occurs specifically at each gene junction (2, 14, 30).

Each VSV gene contains a conserved 3′ gene start sequence and a conserved 5′ gene end sequence. Thus, the junction between two genes consists of a conserved 23-nt sequence: 3′-AUAC UUUUUUU G/CA UUGUCnnUAG-5′, where n is not conserved (18, 21). These sequences have been shown to contain the minimal signals necessary for transcription of monocistronic mRNAs from the VSV genome (23). Termination and polyadenylation of VSV mRNAs is signaled by the first 13 nt of the gene junction, which includes the gene end sequence 3′-AUAC UUUUUUU-5′ and the intergenic dinucleotide 3′-G/CA-5′ (5, 6, 13, 24, 27). Mutational analysis has shown that each nucleotide of the AUAC is important but that the C residue is essential for mRNA termination (5). In addition, the U tract must be a minimum of seven uninterrupted U residues, which is likely due to the need for reiterative addition of poly(A) tails to the 3′ end of VSV messages, a crucial step in the process of mRNA termination, which cannot occur on such shortened or interrupted U tracts (5, 13). When the polymerase fails to recognize the gene end signal, it reads through the gene junction and produces a dicistronic readthrough mRNA. Transcriptive readthrough of the gene junction results in the inhibition of mRNA initiation at the downstream gene start sequence (5, 13).

The intergenic dinucleotide 3′-G/CA-5′ has been shown to have a role in both mRNA termination and initiation (6, 26), although the complementary sequence has not been observed in either the upstream or downstream mRNA products. Transcriptive events at the gene junction are affected by the sequence and the length of the intergenic region (IGR), based on limited extension of the IGR (6, 26). The reason for this is unclear and, to date, no correlation has been observed between the composition of the sequences inserted between the gene end and gene start sequences and their effect on transcription (6, 26).

VSV mRNA initiation and 5′ modification are signaled by the gene start sequence, 3′-UUGUCnnUAG-5′ (27, 28). Although the gene start sequence is conserved for all VSV genes (21), the first 3 nt were identified as the most important for initiation (28). In particular, the second position has been implicated in 5′-end transcript modification, the third position has been identified to be involved in transcript initiation, and the first position, depending on the nucleotide, has a role in both processes (28). These studies were conducted in the context of a complete gene junction, however. The possibility that sequences present at the gene junction other than the gene start sequence are involved in mRNA initiation has not been proposed or tested.

In the present study, we inserted a gene end sequence upstream of the wild-type gene junction in a subgenomic replicon of VSV. We found that mRNA transcription terminated at the inserted gene end sequence and that the polymerase traversed the IGR, now 88 nt instead of 2 nt, to efficiently transcribe the downstream cistron. Addition of a second upstream gene end signal separated the sequences used for termination of the upstream transcript from those used for initiation of the downstream transcript. This allowed us to investigate what role the gene end sequences immediately upstream in the gene junction had on transcription of the downstream gene. We found that the U tract of the gene end sequence, previously characterized as being involved exclusively in mRNA termination, was also required for efficient downstream transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid p(8)+NP, as described previously, provided a template for transcription by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase that, with coexpression of the N, P, and L proteins, produced an encapsidated positive-sense subgenomic replicon of VSV (6). One cycle of replication produced an encapsidated negative-sense template competent for VSV transcription. The subgenomic replicon contained two transcriptional units separated by the wild-type N-P gene junction (Fig. 1A). The IGR of the replicon was extended by insertion of an additional gene end sequence and intergenic dinucleotide, 3′-AUAC UUUUUUU GA-5′, 73 nt upstream of the wild-type gene junction by PCR mutagenesis and restriction fragment exchange. Mutations upstream of the mRNA2 gene start sequence (Fig. 1A, GS2) were introduced using standard techniques (22). All mutations were confirmed by sequence determination using T7 Sequenase (version 2.0; Amersham Life Science).

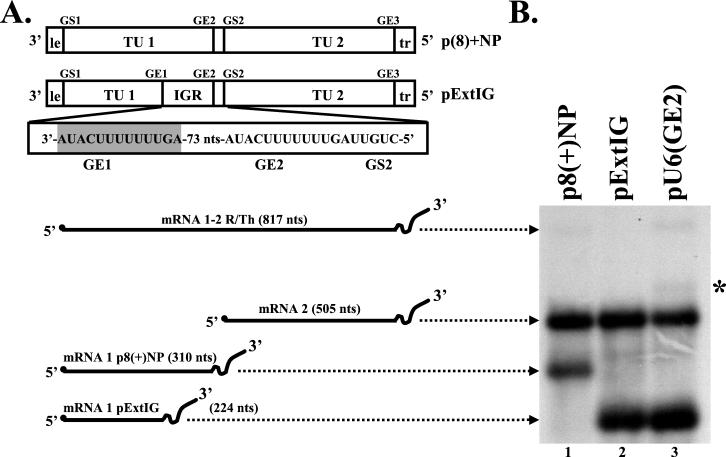

FIG. 1.

Effect on transcription of insertion of an additional gene end signal upstream of the wild-type gene junction in a dicistronic replicon. (A) Schematic diagram of the wild-type VSV bicistronic subgenomic replicon, p8(+)NP, the dicistronic replicon having an extended IGR, pExtIG, and the RNA species transcribed. Replicon p8(+)NP (top) contained two transcriptional units separated by a single gene junction and flanked by leader and trailer regions. Replicon pExtIG (bottom) contained an additional gene end signal (shaded sequence) inserted upstream of the wild-type gene junction. Replicon pU6(GE2) (not drawn) is a mutant of pExtIG that contains a U6 tract at GE2. Abbreviations: GS, gene start sequence; GE, gene end sequence; le, leader; tr, trailer; TU, transcriptional unit; nts, nucleotides; IGR, intergenic region; R/Th, readthrough. (B) Analysis of RNAs synthesized by VSV replicons p8(+)NP (lane 1), pExtIG (lane 2), or pU6(GE2) (lane 3). Plasmids encoding the indicated replicons were transfected into cells as described in Materials and Methods. Actinomycin D-resistant RNAs were metabolically labeled with [3H]uridine, harvested, and incubated with oligo(dT) and RNase H. The resultant RNAs were analyzed by electrophoresis on agarose-urea gels, and the labeled products were visualized by fluorography. Replicon pU6(GE2) (lane 3) generated a minor product (∗), which is described in the text.

Transfections.

Plasmids expressing a VSV subgenomic replicon and supporting N, P, and L proteins were transfected into BHK-21 cells previously infected with a vaccinia virus recombinant (vTF7-3) (12) expressing T7 RNA polymerase, as described previously (19, 31). At 14 to 16 h posttransfection, actinomycin D (10 μg/ml)-resistant RNAs were labeled metabolically with [3H]uridine (33 μCi/ml) for 6 h prior to harvest. Cytoplasmic RNAs were harvested and purified by phenol-chloroform treatment and ethanol precipitation (19, 31). The RNA was analyzed as described below.

Analysis of RNA synthesis.

A fraction of the harvested RNA was subjected to RNase H digestion in the presence of oligo(dT) for 20 min at 37°C to remove the poly(A) tails as described previously (6, 8). After ethanol precipitation, the RNA was resuspended and electrophoresed through a 1.75% agarose-urea gel, and the radiolabeled products were visualized by fluorography and autoradiography (19, 31).

A separate fraction of RNA was incubated with RQ1 DNase (0.13 U/μl; Promega) for 30 min at 37°C to digest any contaminating plasmid DNA remaining from the transfection. The DNase was then inactivated by the addition of EGTA (20 nmol) and incubation at 65°C for 10 min. The RNA was precipitated with ethanol, and the ratio of mRNA2 to mRNA1 was compared by primer extension analysis. Two oligonucleotide primers were used in each reaction that annealed to positive-sense products corresponding to the following regions of the VSV genome: the primer, 1Pext (5′-TTTGATTTTCTGAAGTAATCTGCCGGG-3′), corresponded to positions 170 to 144 of the VSV genome (in the N gene for mRNA1); the second primer, 2Pext (5′-ATCTCATCTATCTCTCCTACCGCC-3′), corresponded to positions 1475 to 1452 (in the P gene for mRNA2). The primers (5 μM) were separately end labeled in the presence of [γ-33P]ATP (0.5 μCi/μl) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (0.4 U/μl; Gibco BRL) for 30 min at 37°C and purified using a QIAquick nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen). The primers were annealed in excess to RQ1-treated RNA and extended with reverse transcriptase (20 U/μl; Superscript II; Gibco BRL) for 30 min at 42°C using reaction conditions recommended by the manufacturer. The radiolabeled cDNA products were electrophoresed through a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Where indicated, the appropriate end-labeled primer was used to generate a sequence ladder (T7 Sequenase, version 2.0; Amersham Life Science) from the appropriate plasmid template.

The 5′ ends of RNA products transcribed from the extended IGR were mapped by primer extension as described above, except that a single primer was used in the extension reaction. One oligonucleotide primer, IGR Pext (5′-TTTTCATATGTAGCATAATATATAATAGG-3′), was designed to anneal to positive-sense products from the extended IGR complementary to nucleotides 1380 to 1352 of the VSV genome (in the N gene) (Fig. 2A). A second oligonucleotide primer, R/Th Pext (5′-TAGGACTTGAGATACTCACG-3′), was designed to anneal to positive-sense products complementary to positions 1436 to 1417 of the VSV genome (in the P gene). This primer was designed to measure initiation events within the IGR that had read through a mutated GE2, compared with initiation events from GS2 (Fig. 2A).

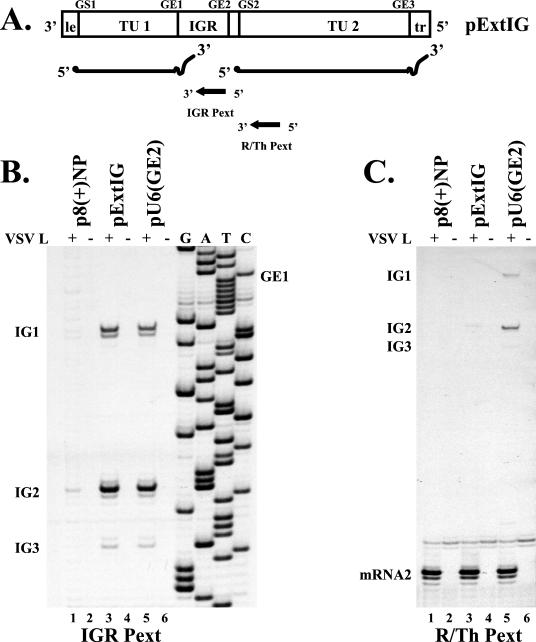

FIG. 2.

Primer extension analysis of positive-sense RNA transcribed from VSV subgenomic replicons. (A) Schematic of replicon pExtIG, positive-sense RNA products, and orientation and position of primer IGR Pext and primer R/Th Pext. (B) Primer extension analysis using end-labeled primer IGR Pext. Lanes 1 and 2, replicon p8(+)NP with (+) and without (−) VSV L, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, replicon pExtIG with (+) and without (−) VSV L, respectively; lanes 5 and 6, replicon pU6(GE2) with (+) and without (−) VSV L, respectively. Reverse transcription was carried out as described in Materials and Methods, and the cDNA products were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. VSV L-dependent products are labeled as IG1, IG2, and IG3. A sequence ladder generated from the pExtIG template using end-labeled primer IGR Pext is shown. GE1 is indicated for reference. (C) Primer extension analysis using end-labeled primer R/Th Pext. Lane assignment is the same as for panel B. VSV L-dependent products are labeled based on comparison with data presented in panel B and a sequence ladder using pExtIG as the template and R/Th Pext as the primer (data not shown).

Quantitation.

The quantity of VSV-specific primer extension products was determined by densitometric analysis of autoradiographs using a Howtek Scanmaster 3 and DNA Quantity One software on a PDI model 320i densitometer. The effect of various mutations on mRNA2 transcription was expressed as a percentage of mRNA2 from the indicated control primer extension products. The cDNA product corresponding to mRNA2 was compared with the cDNA product corresponding to mRNA1, using mRNA1 as an internal standard for VSV polymerase-dependent transcription.

RESULTS

Effect of inserting a gene end sequence upstream of the VSV gene junction.

Transcription of VSV mRNAs is thought to occur by a stop-start model of transcription (4), in that there is a single 3′ polymerase entry site (10), transcription of the genome is obligatorily sequential (1, 3), and transcription and termination of an upstream gene is required before transcription of the downstream gene can occur (5, 6, 13). Because of these characteristics of VSV transcription, it has not been possible to examine the involvement of the upstream gene end sequence on transcription of the downstream gene at a wild-type VSV gene junction. In contrast, previous work has shown that VSV mRNA termination can occur with near-wild-type efficiency in the absence of a gene start sequence immediately downstream (5). To investigate the role of upstream sequences in transcription of the downstream gene, we placed an additional gene end sequence and intergenic dinucleotide, 3′-AUAC UUUUUUU GA-5′, 86 nt upstream of the wild-type gene start sequence. This extended the IGR, defined as the sequence between the last nucleotide of the upstream U tract and the first nucleotide of the downstream gene start sequence, from the wild-type 2 nt to 88 nt (Fig. 1A). The RNA transcripts expressed from the bicistronic subgenomic replicon encoded by this plasmid, pExtIG, were compared to those from the wild-type bicistronic replicon p8(+)NP by transfection with plasmids encoding the VSV N, P, and L proteins into cells previously infected with a vaccinia virus recombinant (vTF7-3) (12) expressing T7 RNA polymerase (19, 31) (Fig. 1B).

Two major RNA products were synthesized from the wild-type p8(+)NP template (mRNA1, 310 nt, and mRNA2, 505 nt; Fig. 1B, lane 1), as described previously (6). A third minor product, just visible on this exposure, was a dicistronic readthrough mRNA (817 nt) that was produced when the polymerase failed to terminate at the gene end sequence for mRNA1 and read through the gene junction (5). Readthrough of a wild-type gene junction occurred infrequently [≈1% for the p8(+)NP template] but increased significantly with certain alterations in the gene end sequence (5). Comparison of the products from p8(+)NP and pExtIG showed that the VSV polymerase terminated mRNA1 transcription in pExtIG at the newly inserted gene end sequence, which was now the first gene end sequence encountered, GE1, as shown by the presence of a truncated, faster-migrating mRNA1 (224 nt; lane 2). Replicon pExtIG was able to direct the efficient synthesis of mRNA2. These data showed that the VSV IGR could be extended up to 88 nt without compromising transcription of the up- or downstream gene. We conclude that transcription by the VSV polymerase was not significantly affected by the extended IGR and the polymerase could efficiently respond to the gene start signals downstream.

We next tested whether transcription of mRNA2 required the presence of a functional gene end sequence (GE2) immediately upstream of the gene start sequence GS2. Although the extended IGR of pExtIG contained no wild-type gene start sequences, the requirements for initiation of VSV mRNAs are provided by the sequence 3′-UYG-5′ (27, 28); thus, it remained possible that the polymerase could have transcribed the extended IGR by initiation at nonconsensus gene start sequences. By terminating transcription of these transcripts at GE2, the polymerase could then initiate transcription at the adjacent GS2 (Fig. 1A). Transcriptive products made from the extended IGR would not be detected by our gel analysis assay because of their small size and low uridine content. The U7 tract of the pExtIG GE2 sequence was shortened to a U6 tract (Fig. 1B, lane 3); this mutation had been previously shown to inhibit mRNA termination at a wild-type gene junction (5). The U6 mutation in GE2 allowed transcription of mRNA2, albeit at a slightly reduced level (Fig. 1B, compare mRNA2, lanes 2 and 3; Fig. 3D). These data showed that a functional termination signal at GE2 was not required for efficient transcription of either the up- or downstream gene and indicated that the extended IGR was not being transcribed to a level or in a manner similar to that of the upstream and downstream cistrons.

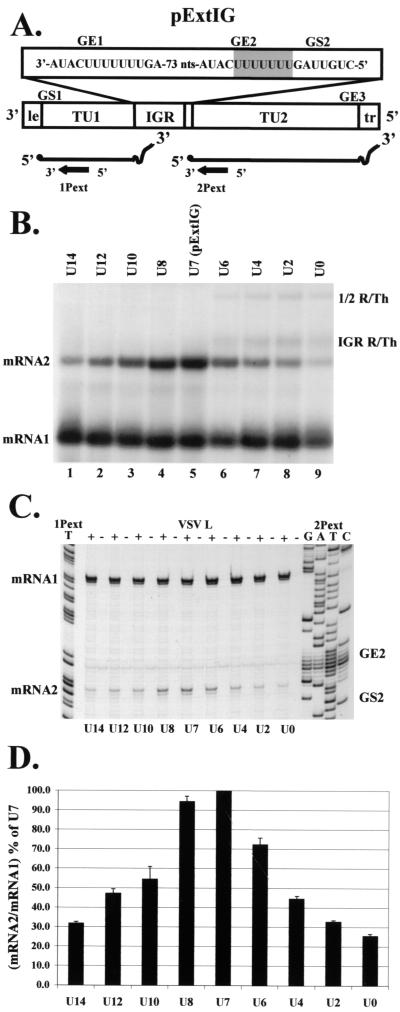

FIG. 3.

Analysis of RNAs transcribed by subgenomic replicons with altered U tract lengths in GE2. (A) Replicon pExtIG, mRNA products, and primer orientation are shown schematically, with the mutated region of pExtIG shaded. (B) Analysis of RNAs synthesized from replicon pExtIG (lane 5) or replicons in which the wild-type U7 tract of GE2 was increased to lengths of 14, 12, 10, or 8 U residues (lanes 1 to 4, respectively) or shortened to lengths of 6, 4, 2, or 0residues (lanes 6 to 9, respectively). RNAs were generated and analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Positions of the RNA products are indicated. (C) Primer extension analysis of RNAs synthesized from replicons described in the legend for panel A, using the end-labeled primers 1Pext and 2Pext as described in Materials and Methods. Sequence ladders were generated from the pExtIG template using the indicated end-labeled primer. Lanes are labeled according to the size of the GE2 U tract and the presence (+) or absence (−) of the VSV L support plasmid in the transfection. The positions of mRNA1, mRNA2, GE2, and GS2 are indicated. (D) Quantitation of primer extension products from three separate transfections and primer extensions, including that shown in panel C. The cDNA products were quantitated, the mRNA2/mRNA1 ratio was calculated, and this was plotted as the mean percentage of the mRNA2 synthesis from pExtIG (U7). Error bars represent one standard deviation from the mean of three primer extension experiments. Where error bars are not visible, the standard deviation was negligible.

However, a minor product was observed in the absence of termination at GE2 (Fig. 1B, lane 3), which indicated that some initiation may have occurred within the extended IGR. Based on its size, it was likely that this product was derived from low-efficiency polymerase initiation events within the extended IGR that had read through the nonfunctioning GE2.

Transcription of the extended IGR.

To identify where these transcripts initiated within the extended IGR, RNAs harvested from cells transfected with p8(+)NP, pExtIG, or pU6(GE2) were analyzed by primer extension by using either a primer that annealed to positive-sense products corresponding to the extended IGR (Fig. 2B) or a primer that annealed to mRNA2 (Fig. 2C). Three VSV L-dependent primer extension products were detected that aligned to sequences within the extended IGR of pExtIG and pU6(GE2) (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 5). These products consist of two bands each and are labeled as IG1, IG2, and IG3. It is likely that the uppermost band in each case was the result of reverse transcriptase adding a nucleotide to the nascent cDNA in response to the cap structure (9). The lowermost band in each case was attributed to the initiating nucleotide of VSV L-dependent transcripts. These products map to the following sequences within the extended IGR: IG1, 3′-CCGUUCAUAC-5′; IG2, 3′-CUGUUUACUG-5′; and IG3, 3′-CUGGGAUAUU-5′, with the corresponding initiation nucleotide underlined. These sequences resemble the wild-type gene start sequence, 3′-UUGUCnnUAG-5′, especially in the first three residues, which have been shown to be critical for initiation (28).

To compare the abundance of the IG1, IG2, and IG3 products with mRNA2, we used a 33P-end-labeled oligonucleotide that annealed to mRNA2 and would detect initiation events at GS2 as well as those within the extended IGR that had read through the mutated gene end sequence present in the pU6(GE) replicon (Fig. 1B). The major product detected by primer extension analysis for each of the replicons [p8(+)NP, pExtIG, and pU6(GE2)] corresponded to VSV polymerase-dependent initiation events at GS2 (Fig. 2C, mRNA2, lanes 1, 3, and 5). Two less abundant primer extension products were detected in lane 5 that mapped to sequences within the extended IGR that correspond to IG1 and IG2 (Fig. 2C). IG3 was seen only faintly in lane 5 after long exposures, which agrees with its relative abundance shown in Fig. 2B. It is likely that these initiation events are responsible for the low abundance product observed in Fig. 1B that migrated slightly slower than mRNA2. Thus, while transcriptional products that initiated within the extended IGR were detected, they were of relatively minor abundance and consequently had little effect on mRNA2 synthesis (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 5, and 1B, lanes 2 and 3). A product of minor abundance was also detected (Fig. 2C, lane 3) that comigrated with the IG2 product visible in lane 5. The distance between the initiation nucleotide of IG2 and GE2 is 62 nt. Thus, this product is likely the result of inefficient polymerase termination at GE2 due to the observed inability of the VSV polymerase to efficiently terminate transcription of messages containing less than 70 nt (32).

Effect of altering the length of the upstream U tract on downstream transcription.

Taken together, the above data showed that the VSV polymerase could traverse an extended IGR of 88 nt and efficiently transcribe the downstream gene. Thus, the cis-acting signals required for termination of the upstream mRNA were spatially separated from those sequences required for initiation of the downstream mRNA, beyond that of the wild-type 2 nt, by the addition of a second upstream gene end sequence. This allowed us to investigate whether sequences upstream of the gene start sequence could affect downstream transcription, independent of their established role in termination.

To analyze the role of the upstream gene end U tract in downstream transcription, we examined the effect of altering the length of the U tract on transcription of the downstream mRNA. A series of mutations were introduced into GE2 of pExtIG that either shortened or lengthened the U tract in increments of 2: U14, U12, U10, U8, U6, U4, U2, and U0. The RNA products from cells transfected with these plasmids were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3B) and by primer extension (Fig. 3C and D). The primer extension assay used two 33P-end-labeled primers in the same extension reaction. The primer 1Pext annealed to mRNA1 and measured GS1-derived initiation events, while primer 2Pext annealed to mRNA2 to measure GS2-derived initiation events (Fig. 3A). Transcript initiation at GS1 was used as an internal standard for VSV polymerase-dependent products to compare changes in GS2 initiation products. The primer extension products were quantitated, and the ratio of mRNA2/mRNA1 was calculated and plotted as a percentage of mRNA2 synthesis from the pExtIG subgenomic replicon (Fig. 3D).

Alteration of the U tract of GE2 by either increasing or decreasing its length reduced the synthesis of mRNA2, as determined both by direct labeling of RNA (Fig. 3B) and by primer extension analysis (Fig. 3C and D). For the most extreme U tract alterations, U14 or U2, downstream mRNA2 synthesis was reduced to very low levels compared to that from the wild-type U7 tract (Fig. 3D). Deletion of the U tract altogether reduced mRNA2 synthesis further still, compared to that of the U7 tract. An additional band was evident among the products of the U6-U0 mutants (Fig. 3B, lanes 6 to 9) and, as described above, this band likely resulted from infrequent initiation events within the extended IGR that read through the nonfunctional GE2. While these readthrough RNAs would account for a portion of the decrease in transcription of the downstream mRNA2, they are insufficient to explain the remaining decrease in mRNA2 production. The larger U tracts, on the other hand, would still be able to direct the termination of the IG1, -2, and -3 readthrough transcripts (5). The U8 tract directed mRNA2 synthesis to near wild-type levels, whereas the U10, U12, and U14 tracts were less efficient in directing mRNA2 production. This raised the possibility that the polymerase has difficulty in traversing large homopolymeric sequences, as suggested previously (5). The U tract of seven residues was previously shown to be essential for polyadenylation and termination of the upstream transcript. The data presented here define a new role for the U7 tract in the efficient transcription of a downstream gene.

Effect of the U14 tract on downstream transcription.

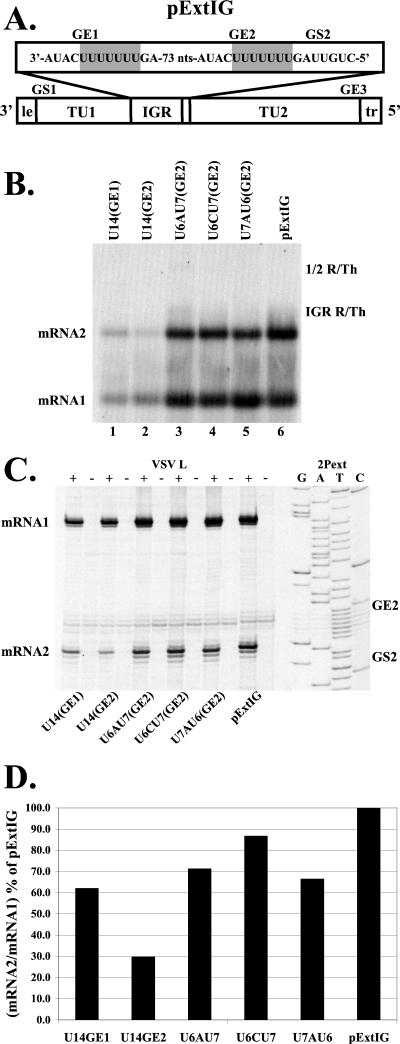

Previously, a U14 tract in the context of an otherwise wild-type gene junction directed efficient termination of the upstream mRNA, but downstream mRNA synthesis was severely reduced (5). Interestingly, the U14(GE2) replicon shown in Fig. 3 directed mRNA2 synthesis that likewise was severely reduced in abundance, although termination and polyadenylation of the upstream mRNA was signaled by the upstream gene end sequence GE1. This suggested that the VSV polymerase had difficulty in crossing large homopolymeric U tracts, even in the absence of their use as templates for polyadenylation. Alternatively, another possible explanation for the results presented in Fig. 3 is that altering the length of the U tract perturbed the spacing between the gene start sequence and an unidentified upstream sequence element(s), possibly including 3′-AUAC-5′ of the gene end sequence or an A/U-rich region upstream of each gene junction in VSV (21). To further investigate the effect that larger U tracts had on mRNA synthesis, the template with a U14 tract at GE2 was used as the basis for further mutation. The homopolymeric U14 tract of GE2 was mutated at position 7 to either an A or a C residue (U6AU7 and U6CU7; Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4) or mutated at position 8 to an A residue (U7AU6; lane 5), thus preserving the length of 14 residues but interrupting the U tract. Also, a U14 tract was separately introduced at GE1 of pExtIG (Fig. 4B, lane 1) to test the effect of a U14 tract that would be used as a template for polyadenylation in the context of the extended IGR. These plasmids, along with U14(GE2) (lane 2) and pExtIG (lane 6), were transfected into cells and the effects of these mutations on mRNA2 synthesis were analyzed.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of RNAs transcribed by subgenomic replicons with U14 tracts in either GE1 or GE2. (A) Replicon pExtIG is shown schematically with the mutated regions shaded. (B) Analysis of RNAs synthesized from replicon pExtIG (lane 6) or from replicons that contained a U14 tract at GE1 [U14(GE1); lane 1], a U14 tract at GE2[U14(GE2); lane 2], or U14 tracts at GE2 interrupted at residue 7 with either A or C (U6AU7 [lane 3] and U6CU7 [lane 4]) or at residue 8 with an A (U7AU6; lane 5). RNAs were generated and analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Positions of the RNA products are indicated. (C) Primer extension analysis of the RNAs synthesized from the replicons described in the legend for panel B. Reverse transcriptions were performed as described in Materials and Methods, using the end-labeled primers 1Pext and 2Pext. A sequence ladder generated from the pExtIG template using the end-labeled 2Pext primer is shown for reference. (D) Quantitation of primer extension products shown in panel C. The cDNA products were quantitated, and the mRNA2/mRNA1 ratio was calculated and plotted as a percentage of the mRNA2 synthesis from pExtIG.

As described above, U14(GE2) directed synthesis of mRNA2 that was reduced compared with that of pExtIG (Fig. 4D). However, interrupting the U14 tract with either an A or C residue at position 7 or an A residue at position 8 substantially restored mRNA2 transcription (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that the reduction of mRNA2 transcription seen with U14(GE2) (Fig. 4) and other alterations in the size of the U tract (Fig. 3) was not due to a disruption of the spacing between the downstream gene start sequence and upstream sequences, but rather was due to the size of the homopolymeric U tract itself. Placing a U14 tract at GE1 reduced the abundance of mRNA2 transcription compared with mRNA1 synthesis (≈60% of pExtIG; Fig. 4D), suggesting that the polymerase may have difficulty in traversing the homopolymeric tract and that this effect was greater when the U14 tract was placed immediately upstream of the gene start sequence. There was a reproducible decrease in overall mRNA synthesis from templates containing U14 tracts (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1 and 2 with 3 to 5). This may be due to an effect on replication of the subgenomic replicons with U14 tracts or an effect on synthesis of the primary T7 transcript.

Effect of altering the sequence of the U tract on downstream transcription.

We next investigated the requirement of a homopolymeric U tract sequence for the production of mRNA2. Mutations that altered the base composition of the U tract region of GE2 were introduced into pU6(GE2). The U6 tract was exchanged for homopolymeric tracts of A6, C6, G6, and mixed purine-pyrimidine tracts of (UA)3 (UAUAUA), (GC)3 (GCGCGC), U3A3 (UUUAAA), and A3U3 (AAAUUU). The effects of these mutations on transcription of mRNA2 are shown in Fig. 5 . Some of the larger readthrough mRNA products in Fig. 5B have altered mobilities due to the agarose-urea gel system used, which separates products based both on size and on base composition (15).

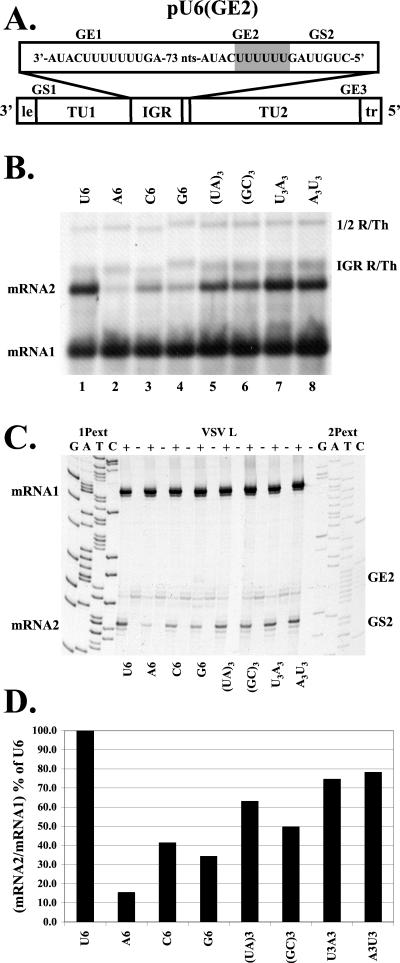

FIG. 5.

Analysis of RNAs transcribed by subgenomic replicons with altered U tract sequences in GE2. (A) Replicon pU6(GE2) is shown schematically with the mutated region shaded. (B) Analysis of RNAs synthesized by a replicon that contained a U6 tract at GE2 [pU6(GE2); lane 1] or replicons where the U6 tract at GE2 was altered to A6 (lane 2), C6 (lane 3), G6 (lane 4), UAUAUA [(UA)3; lane 5], GCGCGC [(GC)3; lane 6], UUUAAA (U3A3; lane 7), or AAAUUU (A3U3; lane 8). RNAs were generated and analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Positions of the RNA products are indicated. (C) Primer extension analysis of the subgenomic replicons shown in panel B. Reverse transcriptions were performed as described inMaterials and Methods, using the end-labeled primers 1Pext and 2Pext. Sequence ladders were generated from the pExtIG template using the indicated end-labeled primer. (D) Quantitation of primer extension products shown in panel C. The cDNA products were quantitated, and the mRNA2/mRNA1 ratio was calculated and plotted as a percentage of the mRNA2 synthesis from pU6(GE2).

In all cases, alteration of the U tract of pU6(GE2) reduced transcription of mRNA2 relative to mRNA1 (Fig. 5B, C, and D). Quantitation of mRNA2 synthesis (Fig. 5D) showed a trend for efficient transcription of mRNA2 in response to the sequence content of the U tract region: U6 > U3A3/A3U3 > (UA)3 > (GC)3 > C6 > G6 ≫ A6. Taken together, these data indicate that efficient downstream transcription specifically required a U tract sequence upstream of the gene start sequence. All of the alterations in the base composition of the U tract region of GE2 maintained the same number of nucleotides upstream of the gene start sequence. These results, in conjunction with those presented in Fig. 4, indicate that the U tract is not required solely to separate the mRNA2 gene start sequence from an upstream sequence element. Rather, the U tract appears to be necessary for efficient downstream transcription.

Effect of altering the AUAC tetranucleotide sequence on downstream transcription.

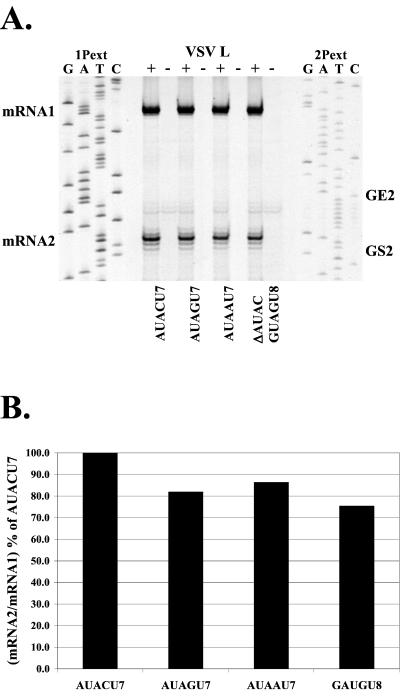

The U7 tract is only one part of the functional gene end signal. Therefore, we also investigated the role of the upstream gene end 3′-AUAC-5′ tetranucleotide on downstream mRNA2 synthesis. The AUAC tetranucleotide was altered at a single position to yield 3′-AUAGU7-5′ and 3′-AUAAU7-5′, or the tetranucleotide was deleted altogether to yield the sequence 3′-GAUGU8-5′ (ΔAUAC). Primer extension analysis of RNA synthesis from these replicons and quantitation of the products are shown in Fig. 6. The results show that alterations to the AUAC of GE2 had little to no effect on the efficiency of mRNA2 synthesis. Synthesis of mRNA2 was reduced in all three mutants to ≈80% of wild type (Fig. 6B). This was in a similar range to that seen with a U6 tract (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the decrease of mRNA2 production in mutants AUAGU7, AUAAU7, and ΔAUAC was due to the failure of the polymerase to terminate synthesis of transcripts initiated at IG1, -2, and -3, as described above (Fig. 2). Thus, the AUAC of GE2 did not contribute significantly to the efficiency of mRNA2 transcription.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of RNAs transcribed by subgenomic replicons with mutated GE2 AUAC sequences. (A) Primer extension analysis of RNA products synthesized by subgenomic replicon pExtIG or replicons in which the 3′-AUACU7-5′ of GE2 was altered to either 3′-AUAGU7-5′, 3′-AUAAU7-5′, or the 3′-AUAC-5′ was deleted (ΔAUAC) to yield 3′-GAUGU8-5′. Reverse transcriptions were performed as described in Materials and Methods, using the end-labeled primers 1Pext and 2Pext. Sequence ladders were generated from the pExtIG template using the indicated end-labeled primer. (B) Quantitation of primer extension products shown in panel A. The cDNA products were quantitated, and the mRNA2/mRNA1 ratio was calculated and plotted as a percentage of the mRNA2 synthesis from pExtIG (3′-AUACU7-5′).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have inserted a gene end sequence upstream of the wild-type gene junction in a subgenomic replicon of VSV. Transcription of the upstream mRNA was terminated at the inserted gene end sequence, and the downstream mRNA was initiated at the downstream gene start sequence. The addition of a gene end sequence upstream of the gene junction extended the IGR from the wild-type 2 nt to 88 nt, and it separated the signals responsible for termination from those for initiation. This allowed us to investigate the role of sequences in the gene end immediately upstream of the second gene on downstream transcription. We found that the U tract of the gene end sequence was important for efficient downstream transcription, independent of its function in termination. Alteration of the size or sequence of the U tract region affected the abundance of the downstream transcript in vivo. A wild-type U tract of seven residues was optimal to direct the efficient synthesis of the downstream mRNA.

Previously it was shown that the VSV polymerase polyadenylated and terminated upstream mRNAs in response to the cis-acting gene end sequence 3′-AUAC UUUUUUU-5′ (5, 13). Initiation and 5′ modification of the downstream mRNA was affected by the gene start sequence 3′-UUGUCnnUAG-5′ (27, 28), with the intergenic 3′-G/CA-5′ having a role in both processes (6, 26). Our data show that for VSV these two RNA synthetic events are linked in both function and sequence. That is, not only is mRNA termination required prior to initiation, but the upstream U tract, which was previously thought to be involved solely in termination, is also required for efficient downstream transcription in a manner that is independent of its role in termination.

A recent report suggested that the U tract of the SV5 SH-HN gene junction acted as a spacer element that separated the gene start sequence from that of the gene end sequence (20). If the U tract of VSV was functioning as a spacer element between the gene start sequence and upstream sequences, this effect was minimal as indicated by our data (Fig. 4 and 5). Indeed, deleting the 3′-AUAC-5′ of the gene end sequence did not significantly reduce mRNA2 synthesis beyond that due to the readthrough of transcripts that had initiated within the extended IGR (Fig. 6). Taking this into account, the sequence required for efficient in vivo initiation in VSV could be expanded from 3′-UUGUCnnUAG-5′ to 3′-UUUUUUU GA UUGUCnnUAG-5′. Support for this also comes from the leader-N junction of VSV-IND, where the sequence immediately upstream of the nontranscribed 3′-GAAA-5′ is a U-rich region with C residues interspersed. This region has been shown to be involved in transcription of the N mRNA (16, 33). It would be interesting to determine if this sequence of the leader can support efficient transcription of a downstream gene.

Our results clearly demonstrate that the U tract has an effect on downstream transcription. Both the length of the U tract and its sequence composition are important. The data presented here, however, do not distinguish what step in mRNA synthesis the U tract affects. It is possible that the U tract may serve as a signal for efficient recognition of the gene start sequence. In this case, it is conceivable that the polymerase recognizes the U7 tract, after polyadenylation, as a signal to reset and initiate transcription at the appropriate nucleotide. Shortening the U tract, as presented in Fig. 3, would remove that part of the gene start signal. Conversely, an extended U tract may perturb this signal and perhaps also cause the polymerase to dissociate from the template. Interruption of an extended U14 tract, which decreased downstream transcription, restored the context of an efficient gene start sequence. The polymerase may efficiently recognize the gene start sequence in the context of the gene junction, perhaps explaining the conservation in size of the intergenic dinucleotide in VSV gene junctions (18, 21). One exception to the IGR conservation is in the VSV-NJ genome that contains a 21-nt IGR between the G gene end and the L gene start sequences (17). This region has been proposed to downregulate L expression (6, 26). The results presented here suggest that separation of the U tract from the gene start sequence may contribute to reduced L mRNA transcription in the case of VSV-NJ.

The U tract may also affect 5′ modification of the downstream mRNA, by the U tract serving as part of the signal for the polymerase to modify the 5′ end of the nascent transcript. Alternatively, the U tract may recruit factors that either modify the nascent transcript or modify the polymerase. Further study will be required to understand the interaction of the cis-acting signals involved in the regulation of VSV transcription.

The results of this study show that transcriptive events at the VSV gene junctions are more complex than previously thought. There appears to be an overlap of function for the sequences involved in termination and initiation. Our data show that the U tract, formerly thought to be involved only in polyadenylation and termination, is also necessary for efficient downstream transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sean Whelan and the members of the G. W. Wertz and L. A. Ball laboratories for helpful discussions during the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by PHS grant R37-AI12464 from NIAID to G.W.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, G., and A. K. Banerjee. 1976. Sequential transcription of the genes of vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:1504-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, L. A., C. R. Pringle, B. Flanagan, V. P. Perepelitsa, and G. W. Wertz. 1999. Phenotypic consequences of rearranging the P, M, and G genes of vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 73:4705-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball, L. A., and C. N. White. 1976. Order of transcription of genes of vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:442-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, A. D., G. Abraham, and R. J. Colonno. 1977. Vesicular stomatitis virus: mode of transcription. J. Gen. Virol. 34:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr, J. N., S. P. Whelan, and G. W. Wertz. 1997. cis-acting signals involved in termination of vesicular stomatitis virus mRNA synthesis include the conserved AUAC and the U7 signal for polyadenylation. J. Virol. 71:8718-8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr, J. N., S. P. Whelan, and G. W. Wertz. 1997. Role of the intergenic dinucleotide in vesicular stomatitis virus RNA transcription. J. Virol. 71:1794-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartwright, B., C. J. Smale, and F. Brown. 1970. Dissection of vesicular stomatitis virus into the infective ribonucleoprotein and immunizing components. J. Gen. Virol. 7:19-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanagh, D., and T. Barrett. 1988. Pneumovirus-like characteristics of the mRNA and proteins of turkey rhinotracheitis virus. Virus Res. 11:241-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davison, A. J., and B. Moss. 1989. Structure of vaccinia virus early promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 210:749-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerson, S. U. 1982. Reconstitution studies detect a single polymerase entry site on the vesicular stomatitis virus genome. Cell 31:635-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emerson, S. U., and Y. Yu. 1975. Both NS and L proteins are required for in vitro RNA synthesis by vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 15:1348-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuerst, T. R., E. G. Niles, F. W. Studier, and B. Moss. 1986. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:8122-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang, L. N., N. Englund, and A. K. Pattnaik. 1998. Polyadenylation of vesicular stomatitis virus mRNA dictates efficient transcription termination at the intercistronic gene junctions. J. Virol. 72:1805-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iverson, L. E., and J. K. Rose. 1981. Localized attenuation and discontinuous synthesis during vesicular stomatitis virus transcription. Cell 23:477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehrach, H., D. Diamond, J. M. Wozney, and H. Boedtker. 1977. RNA molecular weight determinations by gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions, a critical reexamination. Biochemistry 16:4743-4751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, T., and A. K. Pattnaik. 1999. Overlapping signals for transcription and replication at the 3′ terminus of the vesicular stomatitis virus genome. J. Virol. 73:444-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luk, D., P. S. Masters, D. S. Gill, and A. K. Banerjee. 1987. Intergenic sequences of the vesicular stomatitis virus genome (New Jersey serotype): evidence for two transcription initiation sites within the L gene. Virology 160:88-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGeoch, D. J. 1979. Structure of the gene N:gene NS intercistronic junction in the genome of vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell 17:673-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pattnaik, A. K., L. A. Ball, A. W. LeGrone, and G. W. Wertz. 1992. Infectious defective interfering particles of VSV from transcripts of a cDNA clone. Cell 69:1011-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rassa, J. C., G. M. Wilson, G. A. Brewer, and G. D. Parks. 2000. Spacing constraints on reinitiation of paramyxovirus transcription: the gene end U tract acts as a spacer to separate gene end from gene start sites. Virology 274:438-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose, J. K. 1980. Complete intergenic and flanking gene sequences from the genome of vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell 19:415-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Schnell, M. J., L. Buonocore, M. A. Whitt, and J. K. Rose. 1996. The minimal conserved transcription stop-start signal promotes stable expression of a foreign gene in vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 70:2318-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schubert, M., J. D. Keene, R. C. Herman, and R. A. Lazzarini. 1980. Site on the vesicular stomatitis virus genome specifying polyadenylation and the end of the L gene mRNA. J. Virol. 34:550-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smallwood, S., and S. A. Moyer. 1993. Promoter analysis of the vesicular stomatitis virus RNA polymerase. Virology 192:254-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stillman, E. A., and M. A. Whitt. 1998. The length and sequence composition of vesicular stomatitis virus intergenic regions affect mRNA levels and the site of transcript initiation. J. Virol. 72:5565-5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stillman, E. A., and M. A. Whitt. 1997. Mutational analyses of the intergenic dinucleotide and the transcriptional start sequence of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) define sequences required for efficient termination and initiation of VSV transcripts. J. Virol. 71:2127-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stillman, E. A., and M. A. Whitt. 1999. Transcript initiation and 5′-end modifications are separable events during vesicular stomatitis virus transcription. J. Virol. 73:7199-7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villarreal, L. P., M. Breindl, and J. J. Holland. 1976. Determination of molar ratios of vesicular stomatitis virus induced RNA species in BHK21 cells. Biochemistry 15:1663-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wertz, G. W., V. P. Perepelitsa, and L. A. Ball. 1998. Gene rearrangement attenuates expression and lethality of a nonsegmented negative strand RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3501-3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wertz, G. W., S. Whelan, A. LeGrone, and L. A. Ball. 1994. Extent of terminal complementarity modulates the balance between transcription and replication of vesicular stomatitis virus RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:8587-8591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whelan, S. P., J. N. Barr, and G. W. Wertz. 2000. Identification of a minimal size requirement for termination of vesicular stomatitis virus mRNA: implications for the mechanism of transcription. J. Virol. 74:8268-8276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whelan, S. P. J., and G. W. Wertz. 1999. Regulation of RNA synthesis by the genomic termini of vesicular stomatitis virus: identification of distinct sequences essential for transcription but not replication. J. Virol. 73:297-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]