Abstract

It has been proposed that the ectodomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp41 (e-gp41), involved in HIV entry into the target cell, exists in at least two conformations, a pre-hairpin intermediate and a fusion-active hairpin structure. To obtain more information on the structure-sequence relationship in e-gp41, we performed in silico a full single-amino-acid substitution analysis, resulting in a Fold Compatible Database (FCD) for each conformation. The FCD contains for each residue position in a given protein a list of values assessing the energetic compatibility (ECO) of each of the 20 natural amino acids at that position. Our results suggest that FCD predictions are in good agreement with the sequence variation observed for well-validated e-gp41 sequences. The data show that at a minECO threshold value of 5 kcal/mol, about 90% of the observed patient sequence variation is encompassed by the FCD predictions. Some inconsistent FCD predictions at N-helix positions packing against residues of the C helix suggest that packing of both peptides may involve some flexibility and may be attributed to an altered orientation of the C-helical domain versus the N-helical region. The permissiveness of sequence variation in the C helices is in agreement with FCD predictions. Comparison of N-core and triple-hairpin FCDs suggests that the N helices may impose more constraints on sequence variation than the C helices. Although the observed sequences of e-gp41 contain many multiple mutations, our method, which is based on single-point mutations, can predict the natural sequence variability of e-gp41 very well.

Enveloped viruses enter target cells in a two-step process that involves recognition of the host cell and binding to cell surface receptors followed by fusion of cellular and viral membranes. In human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), these functions are performed by the viral envelope glycoprotein (Env) complex gp120-gp41 derived from an inactive precursor, gp160, following proteolytic cleavage (22, 25). gp41 is the transmembrane (TM) subunit that mediates fusion of cellular and viral membranes. The linear organization of gp41 includes an N-terminal fusion peptide that is thought to insert directly into the target membrane during the membrane fusion process, an ectodomain (e-gp41) that contains two types of hydrophobic heptat repeats, and a TM domain which precedes a cytoplasmic domain. The gp41 core is a six-helix bundle composed of three hairpins, each consisting of an N helix and a C helix in an antiparallel pairing by a disulfide-bonded loop region. The N helices form an interior trimeric coiled coil with conserved hydrophobic grooves wherein the C helix packs (6, 9, 37, 38, 46, 50, 54). This hairpin-like structure is conserved in TM protein core fragments from other enveloped viruses, such as influenza (hemagglutinin HA2) (7) and Ebola (Ebola GP2), and likely corresponds to the core of the fusion-active state of gp41 (10).

The mechanism of fusion of gp41 is not well understood but may be similar to fusion processes induced by conformational changes in the envelope protein hemagglutinin (6). The following model of gp41-mediated membrane fusion has been proposed (10, 51). Initially, gp41 exists in a prefusogenic conformation within the trimeric envelope glycoprotein spike. Binding of gp120/gp41 to CD4 induces initial conformational changes in gp120 that expose the coreceptor binding site, and the subsequent binding of gp120 to the coreceptor initiates the membrane fusion process itself (33, 43). Next, a transient pre-hairpin intermediate (prefusogenic state) is formed by exposure of the fusion-peptide region and concurrent formation of the N-terminal coiled-coil trimer (23). Subsequently, the N-terminal coiled coil and the C-terminal helix are assembled into a stable fusion-active (fusogenic) hairpin structure, leading to the local apposition of viral and cellular membranes (6, 50) and subsequent membrane fusion.

The folding of gp41 into its fusogenic conformation, an obligate step in virus entry into the target cell, implies that the conformational properties of both the prehairpin as well as the trimer-hairpin structures may play a critical role in driving membrane fusion. Hence, this motivates research efforts aiming at better understanding the conversion as well as the stability properties of these structures. As these properties are in turn determined by the underlying amino acid sequence of e-gp41, it is important to address the structure-sequence relationship in e-gp41.

HIV-1 is characterized by an unusually high degree of genetic variability in vivo (45). HIV-1 rapidly mutates during infection, resulting in the generation of viruses that can escape immune recognition or become resistant to the drugs that are administered to the patient. To develop successful effective strategies attacking HIV, it may be mandatory to target regions in the viral proteins that show a higher degree of sequence conservation than other regions. In view of the packing constraints in the triple-hairpin structure of e-gp41, this molecule may be an ideal target and undoubtedly this explains the current focus on e-gp41 as a target for drug discovery (5, 20, 21, 32, 44).

Most information on gp41 substitutions was obtained from sequence comparison (18) and from experimental studies (31, 34, 52) addressing changes in stability and in inhibitory activity between wild-type and mutant proteins. As it may be too time-consuming to test experimentally all possible mutations in a protein, we believe it is useful to employ predictive methods aiming at reducing the number of substitutions to be evaluated experimentally.

For that purpose, we used a novel tool, referred to as the FCD generator, for computer-aided design of single-site substitutions (D. Vlieghe, C. Boutton, J. L. Verschelde, I. Lasters, and J. Desmet, submitted for publication) that is based on the recently published FASTER algorithm (17), a new powerful high-throughput algorithm for side chain placement (16). FASTER searches in an iterative way the energetically most comfortable conformation, the so-called Global Minimum Energy Conformation (GMEC), of an arbitrary large collection of protein side chains positioned on a given protein backbone structure. The speed of the FASTER algorithm makes it possible not only to search for the most stabilizing conformation of the side chains but also to assess the energetic compatibility values of different amino acid types at any position throughout the protein, storing these values in a so-called Fold Compatible Database (FCD). More precisely, this database contains for each residue position in a given protein the energy cost of mutating this residue into each possible natural amino acid. These energy values are called Energy Compatible Objects (ECO) and are determined after a full relaxation of the protein environment, allowing the protein to adapt to the introduced mutation. Several methods to predict the response of a protein to point mutations have been published earlier. Some of them are just qualitative (53), and others try to be quantitative by statistical means (47) or by using known energy potentials (24). The advantage of the FCD over the other computational approaches is the fact that an all-atom physical energy function is used and that no average is taken over other protein folds like is done in knowledge-based prediction methods. Since ECO values estimate the compatibility of an amino acid with the current protein fold, ECO values can be seen as the theoretical analogs of experimental ΔΔG observations. However, to underline that the FCD values correspond to modeling predictions, we refer to these values as ECO values and not as ΔΔG values.

In this report, we describe the use of the FCD concept to explore the sequence variation that is compatible with the HIV-1 e-gp41 triple-hairpin structure as well as the pre-hairpin structure. Starting from a reference e-gp41 structure in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (PDB) (3), code 1AIK (9), all possible single amino acid substitutions were generated in silico and the ECO value of each substitution with the e-gp41 scaffold was evaluated. Using the ECO values equipped with a suitable threshold parameter, we studied the correlation of our predictions with the sequence variation as observed from patient data and from a large public database. While we realize that ECO calculations based on single amino acid substitutions have inherent limitations in their predictive value, the present work follows a clear systematic, scientific path wherein, before studying specific combinations of mutations, we address to what extent the e-gp41 observed sequence variation can be explained by considering all single (independent) substitutions within the context of a reference of fixed sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and virus stock preparation.

A total of 32 HIV-1 group M isolates of clades A to H were studied. HIV-1 samples were obtained from patients in Cameroon (CA1, CA4, CA5, CA10, CA13, CA16, CA18, CA20, CA9, and ANT70), Belgium (VI191, VI829, VI968, VI874, VI886, VI943, and VI313), Portugal (VI969), the United States (MN), Ivory Coast (CI13, CI15, CI22, and CI47), Democratic Republic of Congo (MAL, VI820, VI205, and VI761), and Gabon (VI525, VI526, G109, G139, and VI686). Sequence analyses of (parts of) gag and/or env coding regions of these isolates have been reported previously (12, 13, 26, 27, 28, 29, 35, 36, 39-41, 48, 55; W. Janssens, J. N. Nkengasong, L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, P. M. Ndumbe, E. Delaporte, M. Peeters, J. L. Perret, A. Ndoumou, C. Atende, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen, Letter, AIDS 8:1012-1013, 1994). All viruses have been passaged in peripheral blood mononuclear cells except for MAL and the laboratory strain of MN (MNlab), which has been passaged in a continuous cell line (H9 cells) before being carried in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. The primary isolate of MN (MNprim) was never passaged in a continuous cell line (8). Biological clones were derived from primary isolates and lab strains by using the limited dilution technique (2). Clones from obtained monoclonal viruses were expanded and stored for genetic and phenotypic analysis.

Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of biological clones.

Starting from cell-free virus supernatant of biologically cloned virus, the RNA extractions were performed as previously described (4). Viral RNA was transcribed into DNA by using the one-tube Reverse Transcriptase kit (Titan One Tube RT-PCR kit; Roche Diagnostics, Brussels, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For the first round of PCR of the group M viruses, primers SQ-S2 (5′ TACAGGGCTACTATTAACAAGAGA 3′) and WOU29 (5′ TGTAAGTCATTGGTCTTAAAGGTACCTG 3′) were used. The cycle protocol was 45 min at 48°C (cDNA reaction) followed by 2 min at 94°C; 40 cycles for 30, 30, and 120 s at 94, 50, and 68°C, respectively; and one cycle of 7 min at 68°C. Nested PCR was done using the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The primers used were H1E7169 (5′ CTGGAGGAGGAGATATGAGGGACAATT 3′) and WOU28_Not (5′ ccgGCGGCCGCTTTGACCACTTGCCACCCAT 3′). The cycle protocol was three cycles of 60, 60, and 60 s at 94, 55, and 72°C, respectively; 32 cycles of 15, 45, and 60 s at 94, 55, and 72°C, respectively; and one cycle of 7 min at 72°C. For the first round of PCR of the group O viruses, primers O-7755S (5′ GACTCTATGCACCTCCCATC 3′) and A70E9047 (5′ AGGGCTGCATTGTTTTGAGG 3′) were used. The cycle protocol was 45 min at 48°C (cDNA reaction) followed by 2 min at 94°C; 40 cycles for 30, 30, and 60 s at 94, 50, and 68°C, respectively; and one cycle of 7 min at 68°C. The primers used for nested PCR were A70E300 (5′ TGAAAGATATATGGAGAACTGA 3′) and A70E8967 (5′ AAAGTCGACCTGCAGAGGTGCACATGGTTCAGGCTC 3′). The cycle protocol was three cycles of 60, 60, and 60 s at 94, 55, and 72°C, respectively; 32 cycles of 15, 45, and 60 s at 94, 55, and 72°C, respectively; and one cycle of 7 min at 72°C. Sequence analysis of parts of the env/gag genes were performed to confirm the identity of the biological clones. Both DNA strands of a base pair fragment encoding part of the env product gp41 were sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the TREECON software as described previously (49). Syncytium formation was determined on an MT2 cell line as described previously (2). Determination of coreceptor usage was performed as described previously using GHOST cell lines (8).

In addition to the sequences determined at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), nucleotide sequences were determined by BaseClear (Leiden, The Netherlands) by using double-stranded sequencing. Quality of the returned sequences was verified with the APES software (42), which extracts reliable nucleotide sequences from trace files generated by automated sequencers. We also used this tool to disambiguate nucleotides that were not fully resolved by BaseClear's software. Using standard alignment tools, the nucleic acid sequences were aligned and subsequently translated into the corresponding amino acid sequence in the gp41 reading frame.

Generation of compatibility data for structures of e-gp41.

In this study, the three-hairpin and the pre-hairpin structures of e-gp41 were addressed. Several structures of the gp41 core fragments lacking the fusion peptide, the disulfide-bonded loop, and the membrane-spanning sequence have been solved by X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance. All these structures correspond to the fusogenic hairpin structure. We selected, as a reference for later conformation, the crystal structure of HIV-1 e-gp41 with PDB code 1AIK (9) for full single-amino-acid substitution analysis. This helical complex, solved at a resolution of 2.0 Å, is a three-fold symmetrical complex wherein each unit is composed of the peptides N36 (amino acids 546 to 581; residues are numbered according to their position in gp160) and C34 (amino acids 628 to 661). As no crystal structure is available for the pre-hairpin state, we chose to take the triple coiled-coil N36-core structure of 1AIK as a model for this intermediate conformation, since the N and C domains are exposed in this open structure. Of course, such a model is necessarily limited to one part (the N helices). To emphasize that this model lacks the C helices, we refer to this model as the N-core structure.

Using our FCD algorithm (D. Vlieghe, C. Boutton, J. L. Verschelde, I. Lasters, and J. Desmet, submitted for publication), which is based on our recently published FASTER paper (17), we computed for both states of gp41 the energetic compatibility (ECO) of all naturally occurring amino acids at each position in the structures. The ECO is defined as the difference between the global energy of the reference structure and the global energy of the point-mutated protein. Under this definition, at any position, the wild-type (wt) amino acid (from the reference structure) is characterized by a zero ECO value. Negative or slightly positive ECO values correspond to amino acid substitutions that are expected to be energetically compatible with the given protein fold. Conversely, for amino acid substitutions marked by higher positive ECO values, i.e., ECO values beyond a certain ECO threshold, one would expect that these would be incompatible with the underlying scaffold. The energy function used is the CHARMm force field as is the standard used in the Brugel package (14) supplemented with additional terms to account for solvation effects (D. Vlieghe, C. Boutton, J. L. Verschelde, I. Lasters and J. Desmet, submitted for publication). Taking into account the three-fold symmetry relation between the hairpin units, the structure of e-gp41 is systematically substituted by side chain replacements and side chain optimizations but the backbone conformation is assumed to be constant during the optimization process. To account for some limited main-chain flexibility, a set of perturbed backbone conformations is generated, clustered around the reference structure. These perturbed backbone conformations are prepared during a 100-ps restrained molecular dynamics simulation of the original structure, from which 50 snapshots are taken, followed by a restrained minimization procedure using the Brugel modeling program (14). The restraining forces are applied on the distances between two atoms by using a multiplication factor of 2.5 kcal/Å and the steepest descent minimization is terminated after 10,000 iteration steps or when the root mean square of the forces is below 0.02 kcal/mol/Å. Hence, each ECO is represented by a collection of 51 energy values, of which the minimum (minECO) is used to judge whether the gp41 protein scaffold is apt to tolerate a given amino acid type at a given residue position. The FCD algorithm operates on an SGI (IRIX 6.5) machine, taking a total of about 30 h to complete one FCD generation for the N-core structure and about 110 h for the triple-hairpin structure.

Relative entropy as measure of information content calculated at each position in HIV-1.

Relative entropy calculations are useful for identifying patterns in biological sequences (19) and are used here as a way of measuring the amino acid conservation at each position in e-gp41. At each position (pos), the probability Ppos(i) of each of the 20 amino acids (i) is calculated by using the Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1), where kT = 1 and Eipos denotes the minECO recorded in the FCD for amino acid i at position pos:

|

(1) |

Given the probabilities Ppos(i), the relative entropy Hpos (Eq. 2) (19) is defined as follows:

|

(2) |

where Qi is the position-independent frequency of occurrence of the 20 amino acids as observed in globular proteins (11). The relative entropy is always greater than or equal to zero. Typically, a low relative entropy at a given position indicates that the probability of different amino acid types at this position is not fundamentally different from a random, position-independent model. For example, in a fully position-independent situation [Ppos(i) = Q(i) for all i] and hence by equation 2, the relative entropy Ppos equals 0.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The HIV-1 gp41 nucleotide sequence data were deposited in the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ nucleotide sequence databases under the following accession numbers: AJ427989 to AJ428023.

RESULTS

Generation of biological clones.

Biological clones had previously been derived from CI47, CI15, G139, VI969, VI968, VI874, VI943, VI886, CI22, VI761, VI820, and G109 (55). Biological clones of CA1, CA5, CA4, CA9, CA20, VI191, and ANT70 had been generated without further genetic, phenotypic, or antigenic characterization. In addition, primary isolates used in previous neutralization experiments were also cloned: VI313, VI525, VI526, VI686, VI829, CI13, MAL, CA13, and CA10, as well as laboratory strains MNlab and MAL. Using the limiting dilution technique, monoclonal viruses could be obtained from all isolates. Several clones per isolate were expanded and preserved for genetic and phenotypic analyses.

Genotypic and phenotypic characterization.

For the genetic verification of the obtained biological clones, at least one clone derived from each of the primary and laboratory isolates was examined through either sequence analysis or a heteroduplex mobility assay (15). For all clones, genetic analysis was focused on the env gene except for the clones obtained from VI525 and VI526, where parts of both the env and gag genes were analyzed. The genetic subtype of the biological clones was compared to the genetic subtype of the original primary isolates with respect to the same region in that gene.

The subtypes of the env gene coding for part of gp41 for the biological clones that are listed in Table 1 were determined by phylogenetic analysis. The subtyping of the biological clones was done according to preexisting env subtype information as reported for the various primary and laboratory isolates. Phylogenetic analysis also revealed high homology between the original isolates and their derived clone(s) (data not shown). However, for the biological clones derived from VI525 and VI526, discordance in subtypes was found. Although VI525 and VI526 were originally subtyped as G in the env gene and subtype H in the gag gene (35, 36), we found other results. In total, 6 biological clones were derived from VI525 and 12 biological clones were derived from VI526. For VI525, only one clone was subtyped as G for the env and H in the gag gene, just as for the original primary isolate, while five out of six clones were subtyped A for both the env and gag genes, indicating a mixed infection. For VI526, 3 out of 12 clones were subtyped G for env and A for the gag gene, 8 out of 12 were subtyped A for both the env and gag genes, and 1 out of 12 was subtyped A for the gag gene and remained unclassified for the env gene.

TABLE 1.

Set of nonredundant patient sequences of infectious HIV-1 e-gp41 clones

| Clone | Origina | Subtypeb | No. of substitutionsc | Sequenced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N helix set | ||||

| Packinge | ..de.ga..de.ga..de.ga..de.ga..de.ga. | |||

| 1AIKf | B | 0 | SGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQLTVWGIKQLQARIL | |

| CI13 3 | CI | D | 1 | ..................................V. |

| VI886 2 | BE | B | 1 | .......S............................ |

| VI968 1 | BE | B | 1 | ...................M................ |

| CA10 3 | CM | CRF01 | 2 | .......S..........................V. |

| CA16 5 | CM | F2 | 2 | ...........K......................L. |

| CA5 1 | CM | B | 2 | C.................................V. |

| G109 1 | GA | D | 2 | ...................M....I........... |

| MNPRIM3 | US | B | 2 | ...................M..............V. |

| VI205 1 | CD | D | 2 | .....H............................V. |

| VI820 1 | CD | A | 2 | .....................K............V. |

| MNLAB 1 | US | B | 2 | ...................T..............V. |

| CA13 1 | CM | H | 3 | .......S.............K............V. |

| CA20 1 | CM | F2 | 3 | .......S...K......................L. |

| CI15 2 | CI | A | 3 | ...........K.........K............V. |

| VI191 1 | BE | A | 3 | .......S.........H................V. |

| VI313 1 | BE | A | 3 | ..............K......K............V. |

| VI829 1 | BE | C | 3 | .......S...........M..............V. |

| VI969 3 | PT | B | 3 | ...........N.........R............V. |

| VI525 1 | GA | A | 4 | .......S......K......K............V. |

| VI526 2 | GA | A | 4 | ......S.............K.........R..V. |

| CA1 1 | CM | CRF11 | 5 | .......S...K......Q..K............V. |

| G139 7 | GA | D | 5 | .......S...K......Q..R............V. |

| ANT70 1 | CM | O | 9 | K......D......Q...Q..R.S....R..R..L. |

| CA9 4 | CM | O | 9 | K......D......Q...E..R.S....R..R..L. |

| VI686 1 | GA | O | 10 | K......D......QQ..R.S....R..R....L.. |

| Chelix set | ||||

| Packing | a..a...d...a..d...a..d...a..d...a. | |||

| 1 AIKf | B | 0 | WMEWDREINNYTSLIHSLIEESQNQQEKNEQELL | |

| VI886 2 | BE | B | 4 | ....E...G......LY................. |

| VI205 1 | CD | D | 5 | ....E...D...G..Y.......T.......... |

| VI943 1 | BE | B | 5 | ....E...D...G..Y...............D.. |

| CI13 3 | CI | D | 6 | ....E...D...G..Y.......T......K... |

| VI968 1 | BE | B | 6 | ....E...D......YL...A............. |

| CA5 1 | CM | B | 7 | ....E...D...D..Y....K..K...Q...... |

| CI22 1 | CI | B | 7 | ..Q.E..D...D..Y.....A............. |

| VI525 5 | GA | G | 7 | ....E...S...K.Y.......I........D.. |

| MNLAB 1 | US | B | 7 | ..Q.E...D......Y..L.K..T.......... |

| CA1 1 | CM | CRF11 | 8 | .L..E...S...Q.Y...L............... |

| CA18 1 | CM | A | 8 | .LQ..K..S...NI..Y................. |

| CI47 25 | CI | A | 8 | .LQ.....S...D..YD......K.......D.. |

| G109 1 | GA | D | 8 | ....E...D...G..YN......I...Q..K... |

| G139 7 | GA | D | 8 | .LQ..K..S...QI.YN................. |

| VI191 1 | BE | A | 8 | .LQ..K..D...Q..YG..............D.. |

| VI525 1 | GA | A | 8 | .LQ..K..S...QI.YE................. |

| VI969 3 | PT | B | 8 | ....EK..D...EV.YN...K............. |

| CI15 2 | CI | A | 8 | .LQ..K..S...N....Y.............D.. |

| MNPRIM3 | US | B | 9 | ..Q.E...D....T.YE.L.K..........D.. |

| VI313 1 | BE | A | 9 | .LQ..K..S...DI.Y.......I.......D.. |

| VI820 1 | CD | A | 9 | .LQ.EK..S...D..YD...Q............. |

| VI874 5 | BE | B | 9 | .KQ.ET..D......YT.L......K........ |

| VI761 2 | CD | D | 9 | ..Q.E...D...GI.YQ......T......K... |

| CA13 1 | CM | H | 10 | .Q.EK..S...DT.YR...............D.. |

| MAL 5 | CD | D | 10 | ..Q.EK..S...GI.YN......I......K... |

| CA10 3 | CM | CFR11 | 11 | .I..E.......KQ.YE.LT.......R..KD.. |

| CA4 1 | CM | F2 | 11 | ..Q.EK..S...GT.YR...VA.....Q...... |

| VI829 1 | BE | C | 11 | ..Q.....E...GT.Y.L.D..I......KD... |

| CA20 1 | CM | F2 | 12 | .IQ.EK...S...DT.YR...GA.........D. |

| CA16 5 | CM | F2 | 13 | ..Q.E...S...GE.YK...DA.T..DR...D.. |

| ANT70 1 | CM | O | 15 | .Q....Q...IS.T.YEE.QKA.V...Q..KK.. |

| CA9 4 | CM | O | 15 | .Q....Q...VS.I.YEE.QKA.V...E..KK.. |

| VI686 1 | GA | O | 17 | .Q...QQ.D.ISNT.YDE.QKA.V...Q...K.. |

Origin of the patient from which the HIV-1 isolate was obtained. The country codes are as follows: BE, Belgium; CM, Cameroon; GA, Gabon; CI, Ivory Coast; PT, Portugal; CD, The Democratic Republic of the Congo; US, the United States.

Subtype of the env gene coding for part of gp41.

Number of substituted amino acids relative to 1AIK.

Only the substitutions relative to 1AIK are indicated.

Residues in the a and d positions in opposing N helices make homotrimeric interaction stabilizing the coiled-coil structure (10). The residues in the e and g positions pack against residues at the a and d positions of the external anti-parallel C helices as well as helices in the coiled coil itself (51).

1AIK sequence (9), which was used as a reference in this study.

Phenotypic characterization.

In order to examine the phenotypic resemblance between primary isolates and their biological clones, two parameters were examined: the syncytium-inducing (SI) versus non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) capacity and the coreceptor usage. Again, at least one clone derived from each of the primary isolates was examined. For all clones, similar coreceptor usage and SI/NSI capacity were found compared to those of the original primary isolate. Primary isolates VI525 and VI526 are dual-tropic viruses with SI capacity and were shown in the genotypic analysis of the biological clones to be a mixture of viruses with different subtypes (VI526, env G/gag A and env A/gag A; VI525, env A/gag A and env G/gag H). The phenotypic analysis of these clones revealed that the VI525 and VI526 clones subtyped env A/gag A were NSI and exclusively R5 using, while the single VI525 clone subtyped as env G/gag H and the VI526 clones subtyped as env G/gag A are SI and exclusively X4 using.

Sets of nonredundant e-gp41 amino acid sequences.

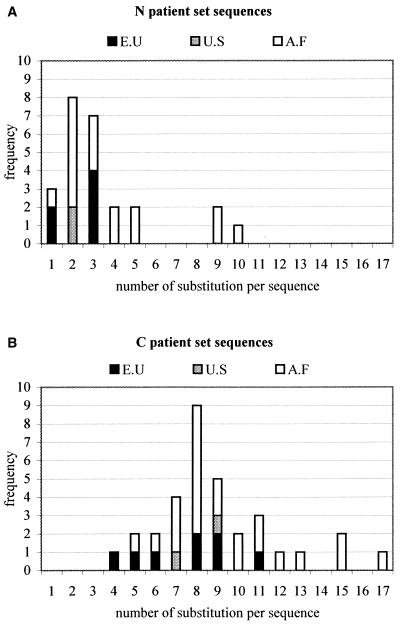

For 35 HIV-1-infected clones derived from HIV-seropositive patients, the gp41 fragment was sequenced both in house as well as by BaseClear (Leiden, The Netherlands). Using standard sequence alignment methods and guided by visual inspection of the alignment, the N-peptide and C-peptide DNA regions were identified and subsequently translated into amino acid sequences by using the gp41 reading frame. For a few clones, the alignment showed insertions. Since these could not be handled by our current modeling tools, those sequences were necessarily discarded. Finally, we applied a redundancy filter at the level of the obtained amino acid sequences. This filter safeguards that only unique sequences are retained and is used to avoid bias in the analysis of the prediction scores. Table 1 shows the alignment of the resulting sequence data set, referred to below as the “patient sequence set.” This set contains 25 N and 33 C nonredundant amino acid sequences. This table also lists the origin of the patient from which the HIV-1 isolate was obtained. It is clear that the majority (about 70%) of the patients are of African origin. Table 1 also includes the 1AIK sequence, used as a reference in this study. It is clear that this reference sequence, subtyped B for the env gene, resembles most the European sequences and the other group M subtypes. The fact that the nonredundant set contains more C sequences than N sequences suggests that the C helix, which in the triple-hairpin structure surrounds the N core, is marked by a higher sequence diversity and concomitantly by a larger number of substitutions per sequence, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Frequency of sequences found in patient sequence set as function of number of substitutions per sequence for N sequences (A) and C sequences (B). The origin of the patient from which the HIV-1 isolate was obtained is indicated: E.U, Europe; U.S, United States; A.F, Africa.

We also performed a blast search (BLASTP [1] on the National Center for Biotechnology Information website) for the N (36 residues) and C (34 residues) peptides, taken from our reference structure 1AIK, against the nonredundant NCBI protein database, resulting in 1,066 nonredundant peptide sequences (ITM sequences included) to form a data set that comprises 185 N and 881 C sequences. This sequence set is referred to below as the “full sequence set.” Clearly, the fact that the nonredundant set contains about five times more C sequences than N sequences is in agreement with the above suggestion that the C helix is more variable than the N helix.

As the outcome of the retrospective analysis was dependent on the quality of the experimental set, it was crucial to work with sequences that were expected to be highly reliable. For this purpose, we defined a third set comprising, in addition to the patient sequence set, all sequences that were found at least two times in the blast search. The latter criterion is based on the universally accepted principle that independently observed and thus reproducible data are more accurate. However, it is noted that sequences not selected by this criterion are not necessarily bad data. This set will be referred to as the “validated sequence set” and contains 236 nonredundant peptide sequences partitioned in 68 N and 168 C sequences.

In the patient sequences, 53% (37 out of 70) of amino acid positions are mutated, resulting in a total of 83 different amino acid substitutions. If only the validated sequence set is taken into account, 69% (48 out of 70) of the positions are mutated at least once, totaling 152 different amino acid substitutions. Considering all the sequences, 93% (65 out of 70) of the positions are mutated at least once, totaling 308 different amino acid substitutions.

Correlation between predicted and observed sequence variation.

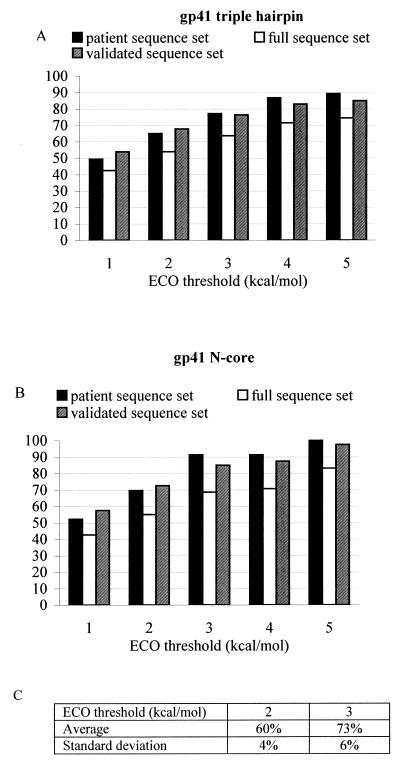

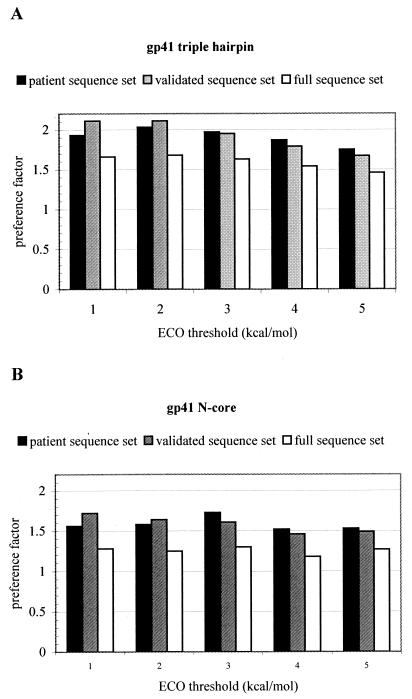

The different variants of e-gp41 from the patient, validated, and full-sequence sets were correlated with the predicted sets of compatible mutations derived from the FCDs of the triple-hairpin and the N-core structures. This analysis involves the usage of a threshold parameter on the compatibility (minECO) values. All amino acid substitutions having a minECO lower than a chosen threshold were considered to be compatible with the underlying scaffold. For both forms of e-gp41, the percentages of observed substitutions for the three sequence sets that were predicted to be fold compatible by the FCD continuously increased when higher threshold values (1 to 5 kcal/mol) were chosen (Fig. 2A and B). As the threshold was raised from 1 to 5 kcal/mol, more and more amino acid variation was found to be compatible with the underlying scaffold, as is shown in Table 2 for the FCDs of both the triple-hairpin and N core structures. Evidently, as the threshold rises, the FCD is bound to become more permissive, tolerating more sequence variation. In the limit of an infinite threshold, the FCD is fully permissive and any amino acid change would be qualified as scaffold compatible. For any minECO threshold, we define the permissiveness of the FCD as the fraction of amino acid changes in the FCD having a minECO value smaller than or equal to the given minECO threshold. To assess to what extent the observed amino acid variation is specifically explained by the FCD, we introduce the notion of preference factor. At any minECO threshold, the preference factor is defined as the ratio between the number of observed substitutions that are in agreement with FCD values and the expected number of these substitutions that would be explained by the FCD just in view of the permissiveness of the FCD. Clearly, at an infinite minECO threshold, the preference factor is necessarily unity. Despite the fact that, at higher minECO thresholds, more of the ECOs are considered to be compatible with the current fold, the preference factor relative to random situation is still significantly higher than would be expected from the FCD permissiveness (Fig. 3), suggesting that the FCD is capable of recognizing the natural sequence variation that is compatible with the e-gp41 structures. For minECO thresholds higher than 5 kcal/mol, the prediction scores start saturating while the preference factor monotonically decreases to 1 (data not shown). This suggests that for minECO thresholds higher than 5 kcal/mol, we gradually move towards a situation wherein the FCD loses specificity. For example, at a minECO threshold of 15 kcal/mol, all prediction scores are 100% with a preference factor of 1, meaning that predictions at this high threshold are the necessary consequence of the full permissiveness of the FCD at such a high minECO threshold.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of observed substitutions for three sequence sets that were predicted to be fold compatible by FCD. (A) Triple-hairpin structure. (B) N core. (C) Percentage of expected substitutions at thresholds of 2 and 3 kcal/mol, considering a set the same size as the patient sequence set but randomly sampled from the full-sequence set for the N helices.

TABLE 2.

Amino acid substitution compatibility

| Structure | % of substitutions compatible at minECO threshold (kcal/mol) ofa:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Triple hairpin | 26 | 32 | 39 | 46 | 51 |

| N core | 33 | 44 | 53 | 60 | 65 |

Shown is the percentage of all possible amino acid substitutions compatible with the underlying scaffold for the FCDs of the triple-hairpin structure and the N-core structure at a given minECO threshold.

FIG. 3.

Preference factors computed at various minECO threshold levels (x axis) for the triple-hairpin (A) and N-core (B) structures in the patient sequence, validated-sequence, and full-sequence sets. The preference factor, defined in the text, describes to what extent the observed sequence variation is specifically explained by the FCD.

The percentages of well-predicted substitutions of the patient and validated sequence sets were higher than those of the full-sequence set (Fig. 2A and B). To assess whether these higher scores were not entirely due to the smaller sizes of the patient and validated sequence sets, we considered a set of the same size as the patient data set, randomly sampled from the full-sequence set for the N core structure. We performed the random selection 25 times and observed an average prediction score of 60% at a 2 kcal/mol ECO threshold and 73% for an ECO threshold of 3 kcal/mol. The standard deviations on these prediction scores were 4 and 6%, respectively. At the same thresholds, we observed prediction scores of, respectively, 70 and 91% for the patient set and 73 and 85% for the validated set (Fig. 2B), indicating that the sequence variation in the patient and validated sets are indeed significantly better predicted than in the full-sequence set.

Comparison of predicted and observed sequence variations in patient sequence set.

The set corresponding to a minECO value of 5 kcal/mol was compared with the patient sequence set. Out of the 83 substitutions, 74 (89%) were FCD compatible with the trimeric hairpin structure of 1AIK and 9 (11%) were predicted to be destabilizing (Table 3). With regard to the N-helix part of the trimeric hairpin structure, it was found that 17 out of 23 (74%) of the substitutions were FCD compatible, whereas 57 out of 60 (95%) of the C-helix substitutions were FCD compatible. Also, at lower minECO thresholds, it was observed that the C-helix substitutions were more FCD compatible than the N-helix substitutions (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Substitutions present in infectious sequencesa

| Amino acid | Substitution |

|---|---|

| N peptide | |

| S546 | 1C, 3K |

| Q551 | 1H |

| N553 | 10S, 3D |

| R557 | 1N 5K |

| E560 | 3Q, 2K |

| A561 | 1T |

| Q563 | 1H |

| H564 | 1E, 4K |

| L565 | 1T 4M |

| Q567 | 7K, 5R |

| T569 | 3S |

| V570 | 1I |

| K574 | 3R |

| Q577 | 4R |

| I580 | 17V, 5L |

| C peptide | |

| M629 | 2I, 10L, 3Q, 1K |

| E630 | 19Q |

| D632 | 22E |

| R633 | 1T, 13K, 1Q |

| E634 | 3Q |

| N636 | 1G, 14S, 14D, 1E |

| Y638 | 1V, 2I |

| T639 | 3S |

| S640 | 9G, 7D, 3N, 1E, 4Q, 2K |

| L641 | 1V, 8T, 7I, 1E, 2Q, |

| S644 | 1G, 4T, 3D, 5N, 5E, 1Q, 1K, 4R, 1A |

| L645 | 2E |

| I646 | 7L |

| E647 | 3Q, 1T |

| E648 | 1G, 2A, 2D, 1Q, 7K, 1V |

| S649 | 6A |

| N651 | 3V, 5T, 5I, 2K |

| Q653 | 1K |

| E654 | 1D |

| K655 | 1E, 5Q, 2R |

| Q658 | 8K |

| E659 | 12D, 3K |

Substitutions in bold are FCD compatible (minECO ≤ 5.0 kcal/mol) with a trimeric hairpin structure. The destabilizing (minECO > 5.0 kcal/mol) predicted substitutions are in lightface italic type.

Considering only the N-core structure (as a model of part of the pre-hairpin structure), all (100%) the 23 different substitutions (implying 15 residue positions) were found to be FCD compatible. Hence, the sequence variation for the N-helix part of e-gp41 appears to be better captured by the N-core FCD than the FCD for the triple-hairpin structure.

Two of the badly predicted substitutions according to our criteria can be considered borderline cases, with ECO values of 5.1 and 5.02 kcal/mol for L565M and Y638I, respectively. Most of the other badly predicted mutants appear to correlate with HIV isolates that are highly variable in sequence compared to our reference sequence. For example, the variants VI526_2, ANT70_1, VI686-1, and CA9_4, containing the A561T and/or the Q577R substitutions in the N sequence (Table 1), also contain other substitutions that are spatially close but located in their related C sequences (Table 1; the C sequence of VI526_2 is identical to VI525_1). The inconsistency with FCD predictions at these positions of the N helix packing against residues of the C helix could be attributed to correlated mutations between the N and C helices. This result suggests that a more pronounced rearrangement of the protein main chain may be necessary to account for all these multiple substitutions. Clearly, as such rearrangements are not encompassed by the current FCD, some inconsistencies with the FCD may arise when analyzing the sequence variation for some of the sequences that show many substitutions with respect to the reference sequence.

Prediction score as function of sequence distance.

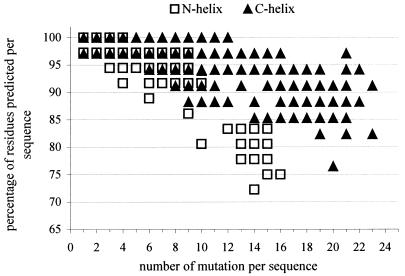

Figure 4 shows for the sequences of the full-sequence set the percentages of residues that are compatible with the FCD for the triple-hairpin structure by using a minECO threshold of 3 kcal/mol as a function of the distance between each of the sequence and the reference sequence taken from 1AIK. This distance corresponds with the number of substitutions relative to the reference sequence. As expected, the largest distances were observed for the C helices. Interestingly, in the distance regime where the prediction score for the N helices significantly dropped (distance > 12), the scores remained very high for the C helices, indicating that the C helices were more permissive to incorporating amino acid variation as opposed to the N helix which is buried within the triple-hairpin structure.

FIG. 4.

Percentage of residues compatible with FCD for triple-hairpin structure as a function of the distance between each of the sequences (full set) and reference sequence 1AIK. This distance corresponds to the number of substitutions relative to the 1AIK sequence. The minECO threshold used was 3 kcal/mol.

FCD predictions for SIV e-gp41.

Comparing e-gp41 of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), it is seen that both structures have dissimilar crossing angles found between the inner N helix and outer C helix (6, 9, 37, 50). However, the central N-helix bundle is structurally similar between HIV-1 and SIV, as these helices superimpose with a root mean square deviation of 0.4 Å using the geometrical fit procedures of the Brugel modelling software (14). Consequently, one could expect that reliable predictions can be derived from our FCD for HIV-1 e-gp41 variants for those parts in SIV e-g41 that do not exhibit marked structural changes compared to the reference structure that was used to build the FCD. To evaluate this view, we attempted to predict the effect of some substitutions in SIV e-gp41 for which detailed experimental data are available.

Recently, it was found that the T586I substitution in SIV e-gp41 strongly stabilizes the trimer of hairpins (30). In HIV, the implied position corresponds to residue I573, which is involved in the N-N interface. Interestingly, all our FCDs showed that Thr at this position would be destabilizing. To verify whether the FCD can successfully predict the scaffold compatibility for T586I in the SIV e-gp41 context, we generated the slightly asymmetrical 2SIV structure (37), an FCD for the T586I substitution, by the same procedure that was followed for the generation of the HIV e-gp41 FCDs. It is seen that the minECO for the T586I substitution is strongly negative (−8 kcal/mol), in agreement with the experimental observation that the SIV T586I substitution is strongly stabilizing (30).

DISCUSSION

Prediction scores.

Recall that the permissiveness of the FCD is defined as the fraction of amino acid changes in the FCD having a minECO value smaller than or equal to the given ECO threshold. It was observed that despite the greater permissiveness of the FCD at higher threshold levels, the sequence variation as observed in the three sequence sets is well recognized by the FCD (Fig. 2). This assertion is also confirmed by the preference factors shown in Fig. 3 computed at the various minECO threshold levels. A preference factor of 1 corresponds to a situation wherein the observed sequence variation would merely follow from the permissiveness of the FCD. A higher preference ratio, at a given minECO threshold, indicates that the biologically observed sequence variation is preferentially confined to the given energy limit. Evidently, if the minECO threshold is taken as very high (infinity is the limit), the preference ratio will unavoidably drop to 1.

Determination of regions permissive and conservative to mutagenesis.

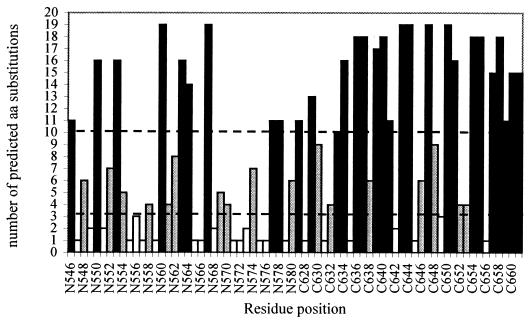

From the FCD, we can determine regions in the triple hairpin that are permissive and less permissive to mutagenesis. For each position, we counted the number of predicted mutations by the FCD for a minECO threshold of 3 kcal/mol (Fig. 5). The N-helix positions 547, 549, 551, 555 to 557, 559, 565 to 566, 568, 571-573, 575 to 576, and 579 and the C-helix positions 628, 631, 635, 642, 645, 649, and 656 all showed fewer than two predicted substitutions and hence were considered conservative. On the other hand, a position may be considered very permissive if more than 10 different amino acid substitutions are predicted. This is applicable to the N-helix positions 546, 550, 553, 560, 563, 564, 567, 577, 578, and 581 and C-helix positions 629, 633, 634, 636, 637, 639 to 641, 643, 644, 647, 650, 651, 654, 655, and 657 to 661. All other positions have intermediate permissiveness.

FIG. 5.

Number of predicted amino acids at each position for minECO threshold of 3 kcal/mol. The classes of permissiveness are defined by thresholds, indicated by the dashed horizontal lines. Very permissive regions (number of predicted substitutions higher than or equal to 10) are marked by black bars. White bars represent the conserved regions (number of predicted amino acid substitutions is lower than 3).

(i) Higher sequence diversity of helix C.

The higher number of predicted FCD-compatible substitutions at a given minECO threshold (in the range of 1 to 5 kcal/mol) for the C helix than for the N-helix in the triple-hairpin FCD (Table 4; Fig. 5) suggests that the e-gp41 structure is permissive for C-helix sequence variation. For example, for a minECO threshold of 3 kcal/mol, only 28% of N positions were very permissive while almost 60% of the C positions were highly mutatable (Fig. 5). This is in agreement with observations that the C helix is more variable than the N helix (Fig. 1), and this correlates with the higher number of nonredundant C helices in both the patient sequence set (Table 1) and the full set. Markedly, comparing Tables 2 and 4, it is seen that the fraction of predicted FCD-compatible substitutions for the N helix in the context of the N core is about the same as that for the C helix in the context of the triple-hairpin structure. As 67% of residue positions of the N helices in the N-core structure are solvent exposed (accessible surface area [ASA] > 25 Å), as are 65% of residue positions of the C helices in the triple-hairpin structure, one may expect that solvent-exposed regions have elevated FCD permissiveness. This explains also why the C helices can adopt larger sequence distances (Fig. 4) while maintaining a high degree of compatibility with the FCD. It is striking that our FCD, which at present models single amino acid variation only within the context of a given reference sequence (1AIK), predicts reasonably well the sequence variation for the more-variable C sequences, indicating that the e-gp41 C helix which shows much more diversity in sequence is likely to be structurally well conserved in most variants, including the group O type.

TABLE 4.

Predicted FCD-compatible substitutionsa

| Structure | % of compatible substitutions at min ECO threshold (kcal/mol) of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| N+C helices | 26 | 32 | 39 | 46 | 51 |

| N helix | 17 | 21 | 27 | 33 | 37 |

| C helix | 35 | 44 | 52 | 61 | 66 |

Data are percentages of predicted FCD-compatible substitutions at a given minECO threshold (kcal/mol) for the N helix and the C helix in the triple-hairpin FCD. For comparison purposes, the results from Table 2 for the ensemble of N helix plus C helix are also shown.

(ii) High conservation for cavity positions.

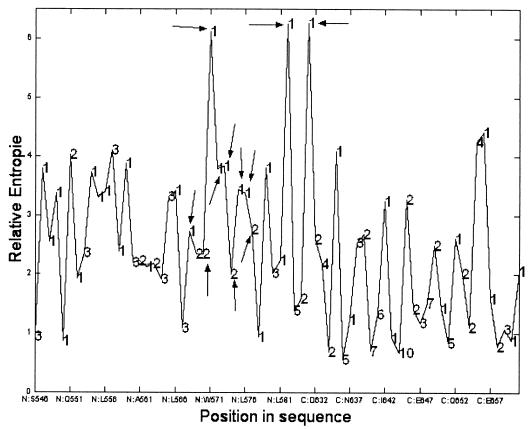

The limited sequence variation in the N helix cavity was remarkably well predicted by the FCD. For cavity residues 568, 570, 571, 572, 573, 574, 575, and 576 (Fig. 5), most of the possible substitutions were marked by high minECO values correlating with the conserved nature of this cavity (37). Interestingly, the few amino acid substitutions in the cavity region observed in the patient data set (V570I and K574R) match with FCD substitutions having the same minECO as the wt amino acid (minECO = 0). Also, residues from the C peptide that pack into the cavity (W628, W631, and I635) were predicted to be very conservative (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the conserved character of this cavity is, to a certain extent, corroborated by the relative entropy computed on the triple-hairpin FCD, as shown in Fig. 6. We observe that the positions with the highest relative entropy that are marked by a pattern of possible amino acid variation that deviates strongly from a random situation imply residues located in the cavity (W571) or filling up the cavity (W628 and W631).

FIG. 6.

Relative entropy plot computed on FCD of triple hairpin of 1AIK. The arrows highlight the residues in the cavity. The numbers superimposed on this plot correspond to the number of different amino acid types observed in the patient sequence set.

Variants from patient sequence set correlate with set of predicted compatible mutants.

The data show that at a moderate minECO threshold (5 kcal/mol), about 90% of the observed sequence variation is encompassed by the FCD predictions of the triple-hairpin state (Fig. 2).

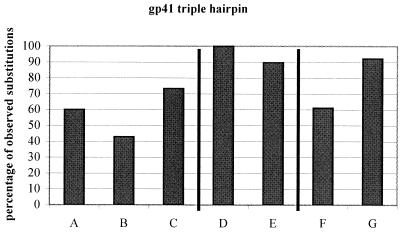

A small fraction (11% at a minECO threshold of 5 kcal/mol) of the sequence variation was not in agreement with FCD predictions of the triple-hairpin structure. However, in these cases, the sequences were generally highly variable compared to our reference sequence. We compared the FCD predictions for the validated-sequence set for different groups of residues according to their packing interactions. The percentages of predicted substitutions were the lowest for residues of the N helices involved in N-C interfaces (Fig. 7). In principle, this decreased score could be attributed to correlated multiple mutations between the N and C helices. To test the hypothesis of correlated mutations, we generated, starting from 1AIK, two mutated structures. One contained the single Q577R substitution in the N regions. The second one contained the double mutation Q577R-K574R and the double mutation M629Q-E634Q in the C regions, corresponding to the variants VI686-1, ANT70_1, and CA9_4. Comparing the minimized energies of these two mutated structures (−922 kcal/mol for the Q577R mutant and −879 kcal/mol for the double mutant) to that of 1AIK (−977 kcal/mol), we saw that both mutated structures were less stable than the wild type, suggesting that the three extra mutations (K574R, M629Q, and E634Q) did not compensate for a predicted destabilizing effect of the single Q577R mutant in 1AIK. Furthermore, this analysis suggests that the N and C helices may be packed in some flexible way allowing e-gp41 to accommodate to some of the highly substituted sequences. This hypothesis is supported by the comparison of the structures of SIV (6, 9, 37, 50) and Visna Virus (38) with HIV. If the N-terminal coiled-coil cores are superimposed, the C peptides are shifted by more than 2 Å along the groove, resulting in a reorientation of the C peptides to the inner N core. Such adjustments are not modeled in our current FCD version that operates on a set of slightly perturbed structures not containing the linking loop between the N and C regions.

FIG. 7.

Percentage of observed substitutions for the validated sequence set that are predicted to be fold compatible by the FCD in the trimer of the hairpin structure. The residues are partitioned into the following groups: residues involved in the N-N (A) and N-C (B) interfaces (10, 51), N-helix residues not implied in such interfaces (C), residues of the C helices (10, 51) (D) and the other residues (E), buried residues (ASA ≤ 25 Å) (F), and those exposed to solvent (G). The minECO threshold used was 5 kcal/mol.

From the dissimilarity in scores in the N-C interface (higher scores for the C-helix residues implied in the N-C interface than for the N helix), we also suggest that the coiled coil of the central N-core helices is imposing more structurally driven restrains on sequence variation than the more-exposed C helices.

Interestingly, the FCD predictions in the N-C peptide complex of the N helices are better correlated with observed group M subtype sequences. Since our reference scaffold 1AIK belongs to group M subtype B, it can be inferred that there is a high level of structural conservation in the N domain of the different group M subtypes. In contrast, the subtype O N helices may, in view of their more pronounced sequence distance relative the 1AIK sequence, adopt structural adaptations in the triple-hairpin conformation (relative to the group M) to maintain the packing interactions between the N and C peptides (6, 10). To accommodate the sequence differences, the packing arrangement between the N and C helices might be somewhat different between the M and O clades. This hypothesis is supported by the dissimilar crossing angles found between the inner N helix and outer C helix of SIV compared to those of HIV-1 (6, 9, 37, 50).

Comparison of predictions for three sequence data sets.

From Fig. 2, it may be suggested that FCD predictions are in better agreement with sequence data that correspond to gp41 variants of well-validated sequences than with sequence variation taken from a large database lacking such rigorous characterization. The results from the random sampling analysis (Fig. 2C) (taking random sets from the full-sequence set that were the same size as the patient sequence set) suggest that the difference in data size between both sets cannot fully explain the difference in score. This view is also corroborated by the preference factors in Fig. 3 showing that these are systematically the highest for the patient and the validated-sequence sets. This analysis suggests that perhaps some of the sequences in the public databases (i.e., those occurring only once) may correspond to noninfected e-gp41 variants archived in the course of routine sequencing work. This hypothesis is supported by the higher score (78%) of predicted FCD compatible substitutions at a threshold of 5 kcal/mol when excluding from the full sequence set all substitutions that occur only once, compared to 70% if all sequences are taken (Fig. 2A).

Comparison between N-core and triple-hairpin FCDs.

The FCD for N-core e-gp41 is apparently more compatible with the N-helix sequence variation than the FCD for the triple-hairpin structure. Indeed, we observed that about 74 and 100% of the sequence variation in the N helices can be explained by the triple-hairpin and N-core FCDs, respectively. To judge the meaning of these results, it is useful to complement these scores with the corresponding preference factors. For the minECO thresholds of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 kcal/mol, the preference factors for the N-helix sequence variation (taken from the patient sequence set) in context of the triple-hairpin structure are 2.78, 2.58, 2.5, 2.4, and 1.96, respectively. These values are much higher than those of the same preference factors determined for the N-core FCD (1.56, 1.58, 1.73, 1.52, and 1.53) (Fig. 3B). We suggest that this again indicates that within the context of the triple-hairpin structure, the sequence variation that is tolerated on the N-helix part of the structure imposes more constraints on sequence variation than cases where the N helix is more solvent exposed, such as possibly in the pre-hairpin structure.

This view is also confirmed by considering only the predictions that result from considering only negative FCD values (corresponding to single-amino-acid substitutions that are predicted to be more preferred than the reference sequence). For the triple-hairpin FCD, it is seen that 13 and 38% of the possible substitutions in the N helices and C helices, respectively, have a negative minECO value. Interestingly, 23 and 37% of the sequence variation observed for the N helix and the C helix, respectively, in the full-sequence set matches with negative minECO values. As for the C helix, the percentage (at minECO values) of possible substitutions (37%) almost exactly matches the FCD-explained sequence variation (37%); we hypothesize that there may not be a strong pressure on the C helix to select for sequence variation that is restrained to the region of negative ECO values (enhanced stability). Such a pressure may well be applicable for the N helix, as considerably more sequence variation (23%) is explained by the FCD than would be expected from considering the fraction of negative minECO values (13%). Moreover, considering the N-core FCD, it is also seen that the fraction of explained N-helix sequence variation (33%) at negative minECO is considerably higher than the fraction of negative minECO values (23%). Hence, the above inferred sequence pressure may also apply for the pre-hairpin form of e-gp41 and may reflect an intrinsic characteristic of the N helix which is implied in specific packing interactions with neighboring N-helices forming a trimeric coiled-coil structure.

This higher pressure on sequence conservation should be explored in drug discovery programs targeting gp41. More in particular, we believe that the FCD will be of great practical use in the design of proteins wherein well-balanced sequence variation is engineered, based on the FCD compatibility values, scattered over a plurality of residues in e-gp41.

The FCD concept appears to be an efficient tool for restricting the number of substitutions that must be tested experimentally. It can be used to search for substitutions in the triple-hairpin structure that are (de)stabilizing (e.g., favoring [or not favoring] the triple-hairpin structure over the pre-hairpin structure). The reduction will of course depend on the used ECO threshold (i.e., the stringency level that is used). If we would, e.g., like to engineer substitutions that are expected to markedly stabilize the triple-hairpin structure, we could use a low minECO threshold of, say, −2 kcal/mol. This would yield 84 candidate substitutions out of a total of 1,440 single-amino-acid substitutions in the triple-hairpin structure, reducing by 94% the number of substitutions that have to be evaluated in a brute force approach. For future work, we propose applying the FCD concept to identify a limited set of substitutions to engineer pre-hairpin e-gp41 structural variants for use in drug screening programs.

In conclusion, we can state that although we worked with a prediction method developed for single-point mutations, the natural sequence variability of e-gp41 can be very well explained. This suggests that the e-gp41 scaffold can accommodate a large variety of sequences while remaining structurally intact and thereby not jeopardizing the key role that e-gp41 plays in viral uptake by the target cell.

Acknowledgments

N.B., C.B., J.-L.V., and I.L thank the “Vlaams Instituut voor de bevordering van het Wetenschappelijk-Technologisch onderzoek in de Industrie” (IWT) for financial support (IWT-project 990255). This work was supported in part by the Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology (VIB), Ghent, Belgium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beirnaert, E., P. Nyambi, B. Willems, L. Heyndrickx, B. Colebunders, W. Janssens, and G. van der Groen. 2000. Identification and characterization of sera from HIV-infected individuals with broad cross-neutralizing activity against group M (env clade A-H) and group O primary HIV-1 isolates. J. Med. Virol. 61:14-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein, F. C., T. F. Koetzle, G. J. B. Williams, E. F. Meywe, Jr., M. D. Brice, J. R. Rodgers, O. Kennard, T. Shimanoushi, and M. Tasumi. 1977. The Protein Data Bank: a computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Biol. 112:535-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boom, R., C. J. Sol, M. M. Salimans, C. L. Jansen, P. M. Wertheim-van Dillen, and J. van der Noordaa. 1990. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:495-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buzko, O. V., and K. M. Shokat. 1999. Blocking HIV entry. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:906-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey, M., M. Cai, J,. Kaufman, S. J. Stahl, P. T. Wingfiel, D. G. Covell, A. M. Gronenborn, and G. M. Clore. 1998. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J. 17:4572-4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr, C. M., C. Chaudhry, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14306-14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecilia, D., V. N. KewalRamani, J. O'Leary, B. Volsky, P. Nyambi, S. Burda, S. Xu, D. R. Littman, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 1998. Neutralization profiles of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates in the context of coreceptor usage. J. Virol. 72:6988-6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan, D. C., Fass, J. M. Berger, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan, D. C., and P. S. Kim. 1998. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93:681-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creighton, T. E. 1993. Proteins: structures and molecular properties, 2nd ed. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Delaporte, E., W. Janssens, M. Peeters, A. Buvé, G. Dibanga, J. L. Perret, V. Ditsambou, J. R. Mba, M. C. G. Courbot, A. Georges, A. Bourgeois, B. Samb, D. Henzel, L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, G. van der Groen, and B. Larouzé. 1996. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of HIV infection in Gabon, 1986-1994. AIDS 10:903-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Leys, R., B. Vanderborght, M. vanden Haesevelde, L. Heyndrickx, A. van Geel, C. Wauters, R. Bernaerts, E. Saman, P. Nijs, B. Willems, H. Taelman, G. van der Groen, P. Piot, T. Tersmette, J. G. Huisman, and H. Van Heuverswyn. 1990. Isolation and partial characterization of an unusual human immunodeficiency retrovirus from two persons of west-central African origin. J. Virol. 64:1207-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delhaise, P., M. Bardiaux, and S. Wodak. 1984. Interactive computer animation of macromolecules. J. Mol. Graph. 2:103-106. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delwart, E. L., E. G. Shpaer, J. Louwagie, F. E. McCutchan, M. Grez, H. Rubsamen-Waigmann, and J. I. Mullins. 1993. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science 262:1257-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Maeyer, M., J. Desmet, and I. Lasters. 1997. All in one: a highly detailed rotamer library improves both accuracy and speed in the modeling of side-chains by dead-end elimination. Folding Design 2:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desmet, J., J. Spriet, and I. Lasters. 2002. Fast and accurate side-chain topology and energy refinement (FASTER) as a new method for protein structure optimization. Proteins 48:31-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Dong, X-N, Y. Xiao, M. P. Dierich, and Y-H Chen. 2001. N- and C-domains of HIV-1 gp41: mutation, structure and functions. Immunol. Lett. 75:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durbin, R., S. Eddy, A. Krogh, and G. Mitchinson. 1998. Biological sequence analysis: probabilistic models for proteins and nucleic acids, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 20.Eckert, D. M., V. N. Malashkevich, L. H. Hong, P. A. Carr, and P. S. Kim. 1999. Inhibition HIV-1 entry: discovery of D-peptide inhibitors that target the gp41 coiled-coil pocket. Cell 99:103-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer, M., T. M. Kapoor, T. Strassmaier, W. Weissenhorn, J. J. Skehel, D. Oprian, S. L. Schreiber, D. C. Wiley, and S. C. Harrison. 1999. Selection of gp41-mediated HIV-1 cell entry inhibitors from biased combinatorial libraries of non-natural binding elements. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:953-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freed, E. O., and M. A. Martin. 1995. The role of human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope glycoproteins in virus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 270:23883-23886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuta, R. A., C. T. Wild, Y. Weng, and C. D. Weiss. 1998. Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:26-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilis, D., and M. Rooman. 2000. PoPMuSiC, an algorithm for predicting protein mutant stability changes: application to prion proteins. Protein Eng. 13:849-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallenberger, S., M. Moulard, M. Sordel, H. D. Klenk, and W. Garten. 1997. The role of eukaryotic subtilisin-like endoproteases for the activation of human immunodeficiency virus glycoproteins in natural host cells. J. Virol. 71:1036-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyndrickx, L., W. Janssens, S. Coppens, K. Vereecken, B. Willems, K. Fransen, R. Colebunders, M. Vandenbruaene, and G. van der Groen. 1998. HIV type 1 C2V3 env diversity among Belgian individuals. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1291-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssens, W., L. Heyndrickx, Y. Van de Peer, A. Bouckaert, K. Fransen, J. Motte, G. M. Gershy-Damet, M. Peeters, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen. 1994. Molecular phylogeny of part of the env gene of HIV-1 strains isolated in Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS 8:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janssens, W., L. Heyndrickx, G. Van der Auwera, J. Nkengasong, E. Beirnaert, K. Vereecken, S. Coppens, B. Willems, K. Fransen, M. Peeters, P. Ndumbe, E. Delaporte, and G. van der Groen. 1999. Interpatient genetic variability of HIV-1 group O. AIDS 13:41-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janssens, W., T. Laukkanen, M. O. Salminen, J. K. Carr, G. Van der Auwera, L. Heyndrickx, G. van der Groen, and F. E. McCutchan. 2000. HIV-1 subtype H near-full genome reference strains and analysis of subtype-H-containing inter-subtype recombinants. AIDS 14:1533-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jelesarov, I., and M. Lu. 2001. Thermodynamics of trimer-of-hairpins formation by the SIV gp41 envelope protein. J. Mol. Biol. 307:637-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji, H., W. Shu, F. T. Burling, S. Jiang and M. Lu. 1999. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity by the gp41 core: role of a conserved hydrophobic cavity in membrane fusion. J. Virol. 73:8578-8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kliger, Y., and Y. Shai. 2000. Inhibition of HIV-1 entry before gp41 folds into its fusion-active conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 295:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu, M., H. Ji, and S. Shen. 1999. Subdomain folding and biological activity of the core structure from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41: implications for viral membrane fusion. J. Virol. 73:4433-4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Louwagie, J., W. Janssens, J. Mascola, L. Heyndrickx, P. Hegerich, G. van der Groen, F. E. McCutchan, and D. S. Burke. 1995. Genetic diversity of the envelope glycoprotein from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates of African origin. J. Virol. 69:263-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louwagie, J., F. E. McCutchan, M. Peeters, T. P. Brennan, E. Sanders-Buell, G. A. Eddy, G. van der Groen, K. Fransen, G. M. Gershy-Damet, R. Deleys, and D. Burke. 1993. Phylogenetic analysis of gag genes from 70 international HIV-1 isolates provides evidence for multiple genotypes. AIDS 7:769-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malashkevich, V. N., C. Chan, C. T. Chutkowski, and P. S. Kim. 1998. Crystal structure of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gp41 core: conserved helical interactions underlie the broad inhibitory activity of gp41 peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9134-9139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malashkevich, V. N., M. Singh, and P. S. Kim. 2001. The trimer-of-hairpins motif in membrane fusion: Visna virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8502-8506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCutchan, F. E., J. K. Carr, M. Bajani, E. Sanders-Buell, T. O. Harry, T. C. Stoeckli, K. E. Robbins, W. Gashau, A. Nasidi, W. Janssens, and M. L. Kalish. 1999. Subtype G and multiple forms of A/G intersubtype recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Nigeria. Virology 254:226-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nkengasong, J. N., W. Janssens, L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, P. M. Ndumbe, J. Motte, A. Leonaers, M. Ngolle, J. Ayuk, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen. 1994. Genotypic subtypes of HIV-1 in Cameroon. AIDS 8:1405-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nkengasong, J. N., M. Peeters, P. Zhong, B. Willems, W. Janssens, L. Heyndrickx, K. Fransen, P. M. Ndumbe, G. M. Gershy-Damet, P. Nys, L. Kestens, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen. 1995. Biological phenotypes of HIV-1 subtypes A and B strains of diverse origins. J. Med. Virol. 47:278-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pletinckx, J., A. Janssen, J. van Oeveren, P. Stas, I. Lasters, and R. van Schaik. 2000. ISMB 2000, 9th International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, p. 63.

- 43.Rizzuto, C. D., R. Wyatt, N. Hernandez-Ramos, Y. Sun, P. D. Kwong, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. Sodroski. 1998. A conserved HIV gp10 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science 280:1949-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Root, M. J., M. S. Kay, and P. S. Kim. 2001. Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science 291:884-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saag, M. S., B. H. Hahn, J. Gibbons, Y. Li, E. S. Parks, W. P. Parks, and G. M. Shaw. 1988. Extensive variation of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in vivo. Nature 334:440-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan, K., J. Liu, J. Wang, S. Shen, and M. Lu. 1997. Atomic structure of the thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12303-12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Topham, C. M., N. Srinivasan, and T. L. Blundell. 1997. Prediction of the stability of protein mutants based on structural environment-dependent amino acid substitution and propensity tables. Protein Eng. 10:7-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.vanden Haesevelde, M., J. L. Decourt, R. J. De Leys, B. Vanderborght, G. van der Groen, H. van Heuverswijn, and E. Saman. 1994. Genomic cloning and complete sequence analysis of a highly divergent African human immunodeficiency virus isolate. J. Virol. 68:1586-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van de Peer, Y., and R. De Wachter. 1994. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1997. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387:426-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, L. J. Calder, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1999. Structural basis for membrane fusion b enveloped viruses. Mol. Membr. Biol. 16:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weng, Y., Z. Yang, and C. D. Weiss. 2000. Structure-function studies of the self-assembly domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41. 74:5368-5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wright, J. D., and C. Lim. 2001. A fast method for predicting amino acid mutations that lead to unfolding. Protein Eng. 14:479-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, Z. N., T. C. Mueser, J. Kaufman, S. J. Stahl, P. T. Wingfield, and C. C. Hyde. 1999. The crystal structure of the SIV gp41 ectodomain at 1.47 Å resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 126:131-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong, P., M. Peeters, W. Janssens, K. Fransen, L. Heyndrickx, G. Vanham, B. Willems, P. Piot, and G. van der Groen. 1995. Correlation between genetic and biological properties of biologically cloned HIV type 1 viruses representing subtypes A, B, and D. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:239-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]