Abstract

An endothelial cell-tropic and leukotropic human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) clinical isolate was cloned as a fusion-inducing factor X-bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli, and the ribonucleotide reductase homolog UL45 was deleted. Reconstituted virus RVFIX and RVΔUL45 grew equally well in human fibroblasts and human endothelial cells. Thus, UL45 is dispensable for growth of HCMV in both cell types.

With the advent of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) technology (9), many human herpesviruses have been cloned as BACs in Escherichia coli (1, 2, 4, 8, 11-13, 18, 21, 23). Owing to the slow replication kinetics and cell-associated growth of clinical isolates of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), it was impossible to date to construct deletion mutants of clinical strains of HCMV. To overcome this problem, cloning of a clinical strain of HCMV as a BAC was needed, in order to obtain standard genetic reference material to be utilized in mutagenesis experiments with the tools of bacterial genetics (1, 2, 14). Recently, it was reported (3) that the murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) ribonucleotide reductase homolog (encoded by the M45 open reading frame) is indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells. In fact, disruption of M45 induced apoptosis in MCMV-infected endothelial cells. These findings linked endothelial cell tropism of cytomegalovirus to the ability of the murine ribonucleotide reductase homolog M45 to protect cells from apoptosis. Since the HCMV homolog of M45 (UL45) also encodes an homolog of the large subunit (R1) of the human ribonucleotide reductase, it was inferred that deletion of UL45 in the context of a clinical endothelial cell-tropic HCMV may render the virus replication incompetent in endothelial cells.

For the present report, a clinical isolate of HCMV (VR1814), previously shown to be leukotropic and endothelial cell tropic (17), was cloned as a BAC (fusion-inducing factor X [FIX]-BAC). The FIX-BAC reconstituted virus (RVFIX) was shown to preserve the wild-type characteristics of the parental strain. Analysis of a virus deletion mutant of UL45 showed that the ribonucleotide reductase homolog is dispensable for growth of HCMV in human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELF) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC).

Cloning and characterization of FIX-BAC.

A clinical HCMV isolate (VR1814) was recovered from a cervical swab of a pregnant woman. VR1814 was shown to grow efficiently on HUVEC and to be capable of transferring virus material to polymorphonuclear leukocytes (17). Therefore, VR1814 was cloned as a BAC in E. coli by adapting a previously reported protocol (2). Briefly, 107 human foreskin fibroblasts were transfected with 35 μg of plasmid pEB1997 containing a tk-gpt-bac-cassette flanked with HCMV homologous sequences of US1-US2 (nucleotides [nt] 192648 to 193360) on the right side and US6-US7 (nucleotides 195705 to 197398) on the left side of the cassette. After 24 h the cell monolayer was infected with VR1814 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. Cells were cultured until a 100% cytopathic effect was reached. Infected cells were then subjected to three rounds of selection with 100 μM xanthine and 25 μM mycophenolic acid. Circular viral intermediates were obtained by a modified Hirt extraction (2). DNA was electroporated into E. coli DH10B using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II (2.5 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω). Bacteria were then plated onto agar containing 12.5 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. After 24 h colonies were picked and grown in liquid culture for bacmid preparation as previously described (2). The BAC-cloned VR1814 genome was referred to as FIX-BAC.

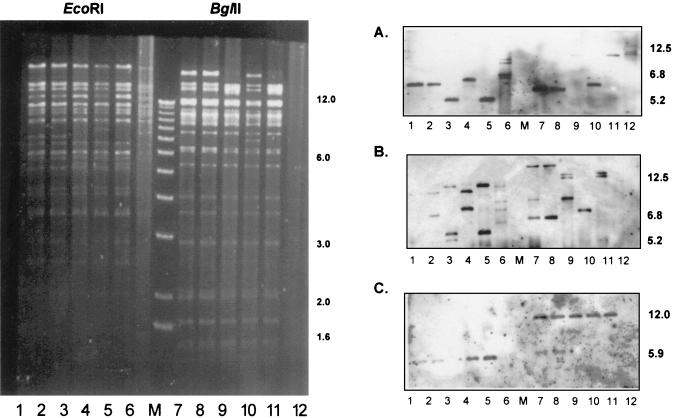

DNA of five (nos. 1, 6, 7, 11, and 14) representative clones of FIX-BAC (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 5 and 7 to 11) and of the parental strain VR1814 (Fig. 1, lanes 6 and 12) was digested with either EcoRI (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 6) or BglII (Fig. 1, lanes 7 to 12) and separated on a 0.5% agarose gel (Fig. 1). Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 1A to C) was performed using the following probes: the US1-specific probe (Fig. 1A) was isolated as a 750-bp SalI-NotI fragment from plasmid pON2244 (1), the α sequence-specific probe (Fig. 1B) was an XhoI-linearized plasmid p226X (kindly provided by M. McVoy, Richmond, Va.), and the BAC-specific probe (Fig. 1C) was a 1.4-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment from plasmid pKSO (2). The US1-specific probe detected EcoRI fragments of about 6.8 and 5.2 kb. The α sequence-specific probe detected the internal α repeats present in the US1-specific fragment and additionally a roughly 12.5-kb EcoRI fragment containing the terminal α sequence repeats. The BAC-specific probe detected the expected 5.9-kb EcoRI fragment representing the newly introduced BAC cassette. Since no sequence information of the parental strain VR1814 is presently available, specific predictions of the restriction enzyme pattern were not possible. The size variation of the α sequence containing internal and terminal repeat fragments can be explained by the various copy numbers of α sequences in individual bacmid clones. One representative bacmid clone (no. 7) was used for subsequent deletion of UL45.

FIG. 1.

EcoRI (lanes 1 to 6) and BglII (lanes 7 to 12) restriction patterns of the endothelial cell-tropic HCMV clinical isolate VR1814 (lanes 6 and 12) and of FIX-BAC clones 1, 6, 7, 11, and 14 (lanes 1 to 5 and 7 to 11). Southern blot hybridization was performed with US1 (A)-, α sequence (B)-, and BAC (C)-specific probes. M, 1-kb ladder molecular size marker. Numerals on right of panels indicate kilobases.

Construction of a ΔUL45 mutant virus.

Deletion of UL45 was achieved by linear recombination with a PCR fragment in a recombination-proficient E. coli strain containing FIX-BAC and expressing bacteriophage λ recombinases (redαβγ) (22). Briefly, a PCR fragment was generated using the kanamycin resistance gene from plasmid pAcyc177 (New England Biolabs) as a template. The primers used for amplifying the kanamycin resistance gene were designed to introduce an approximately 60-bp (boldface) HCMV-homologous sequence on the 5′ and 3′ ends of the PCR product (P-45.1, 5′-GCC AGT GGT ACC ACT TGA GCA TCC TGG CCA GAA GCA CGT CGG GCG TCA TCC CCG AGT CAT AGT AGC GAT TTA TTC AAC AAA GCC ACG-3′; and P-45.2, 5′-ACA CAT CGC ACA CAG ACT TTA TAA ACC GTA GTT GTC GGC GCC ATC TAG ACT CAC TTT ATT GAA AGC CAG TGT TAC AAC CAA TTA ACC-3′). Structural analyses of FIX-BAC and ΔUL45-BAC as well as of the reconstituted virus (RVFIX) and mutant virus (RVΔUL45) were performed by DNA digestion with EcoRI and HindIII and subsequent separation on a 0.5% agarose gel. In addition, digested DNA was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization for the presence of the kanamycin resistance cassette.

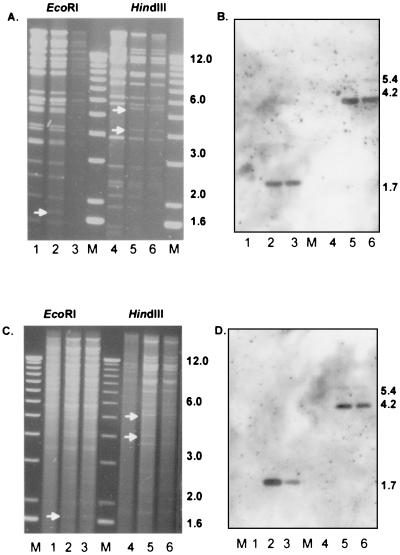

Reconstitution of RVFIX and RVΔUL45 was obtained by transfection of FIX-BAC and ΔUL45-BAC DNA into fibroblasts (MRC-5) as reported earlier (2). Two independent RVΔUL45 virus mutants were generated by transfection of ΔUL45-BAC DNA from independently generated clones (nos. 6 and 11). Figure 2 shows FIX-BAC and ΔUL45 DNA profiles of the bacmids (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 6) and reconstituted viruses (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 to 6) after digestion with EcoRI (Fig. 2, lanes 1 to 3) and HindIII (Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 6). In the EcoRI digest the deletion of the UL45 gene shifts a 3.4-kb fragment to a 1.7-kb fragment. In the HindIII digest the 11.3-kb fragment (corrected sequence according to reference 5) of the FIX-BAC parental clone is cleaved into two subfragments of 4.2 and 5.4 kb in ΔUL45 after insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette. A UL45-specific probe detected the expected 3.4-kb (EcoRI) and 11.3-kb (HindIII) fragments in RVFIX but not in the RVΔUL45 mutant viruses (data not shown). Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2B and D) confirmed the presence of kanamycin resistance sequences in ΔUL45 bacmid and reconstituted viruses, and sequencing of RVΔUL45 virus mutant confirmed the correct deletion of UL45 from nt 56756 to nt 59409.

FIG. 2.

EcoRI (lanes 1 to 3) and HindIII (lanes 4 to 6) restriction pattern of FIX-BAC (A) (lanes 1 and 4) and FIX-BAC-ΔUL45 deletion mutant (A) (lanes 2 and 3 and 5 and 6). (B) Southern blot hybridization using pAcyc as a probe indicates the correct insertion of the kanamycin cassette. Newly arising fragments are marked with a white arrow. (C) EcoRI (lanes 1 to 3) and HindIII (lanes 4 to 6) restriction patterns of reconstituted viruses RVFIX (lanes 1 and 4) and RVΔUL45 (lanes 2 and 3 and 5 and 6). (D) Southern blot hybridization using pAcyc as a probe. M, 1-kb ladder molecular size marker. Numerals on right of panels indicate kilobases.

Growth characteristics of RVFIX and RVΔUL45 on fibroblasts and HUVEC.

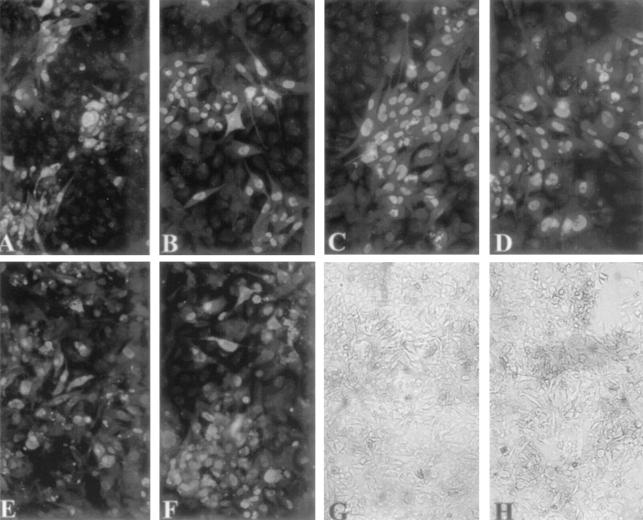

Growth characteristics of RVFIX and RVΔUL45 (clones 6 and 11) on fibroblasts and HUVEC were analyzed after infection of the relevant cells with either parental or mutant virus with an MOI of 1. At days 1, 4, 7, 10, and 14, virus titers from either sonicated infected cells (cell-associated virus) or supernatants (cell-free virus) were determined by detecting single virus-infected cells 48 h postinfection (p.i.) by a p72-specific monoclonal antibody and the indirect immunoperoxidase technique (6). Growth curves of RVFIX and RVΔUL45 on HELF showed no significant impairment in replication kinetics of the mutant virus (Fig. 3). Most importantly, infection of HUVEC with the RVΔUL45 mutant virus did not impair virus replication in endothelial cells (Fig. 3). Additionally, adaptation to growth in HUVEC of RVFIX and RVΔUL45 was attempted by mixing virus-infected HELF and uninfected HUVEC at a ratio of 1:2. Subsequently, the infected cell mixture was propagated on uninfected HUVEC weekly for five passages. Afterwards, infected cell cultures were sonicated and cell-free viruses were seeded onto uninfected HUVEC. Subsequent passages were performed by seeding infected onto uninfected HUVEC (17). Indirect immunofluorescence staining was performed with a combination of monoclonal antibodies against p72 (nuclear staining) and gB (cytoplasmic staining). As shown in Fig. 4 RVΔUL45 mutants could be successfully passaged over several rounds (>20 times) on HUVEC, confirming the dispensability of UL45 for virus growth in endothelial cells.

FIG. 3.

Growth curves of bacmid-reconstituted virus RVFIX and RVΔUL45 virus deletion mutant. Titers were measured as both cell-free and cell-associated virus in HELF cultures at days 1, 4, 7, 10, and 14 p.i. using an immunoperoxidase staining technique (3).

FIG. 4.

HUVEC growth adaptation of RV-FIX (A, C, E, and G) and RVΔUL45 (B, D, F, and H) after passage 3 (A and B), passage 5 (C and D), and passage 15 (E to H) performed according to a reported protocol (7). Medium-sized plaques in panels A and B became larger plaques in panels C and D until the spreading of viral infection to the entire cell monolayer in panels E through H. (A to F) Indirect immunofluorescence staining with a combination of monoclonal antibodies to p72 (nuclear staining) and gB (cytoplasmic staining). The gB monoclonal antibody was kindly provided by Lenore Pereira (University of California, San Francisco). (G and H) Cytopathic effect of infected HUVEC as observed in living cells at passage 15.

Apoptosis.

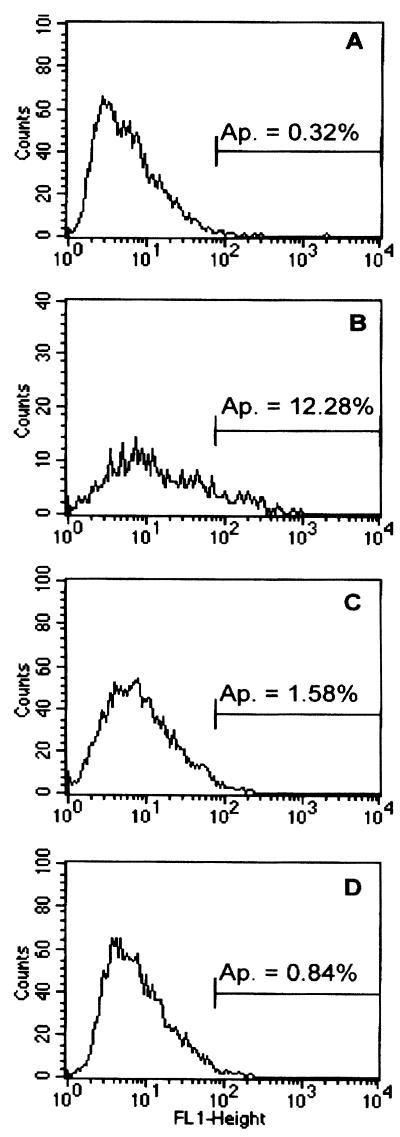

Induction of apoptosis in RVFIX- and RVΔUL45-infected HUVEC was analyzed using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling staining (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's guidance. Briefly, HUVEC were infected at an MOI of 1 and harvested at 24 h p.i. Cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium citrate. Fragmented cellular DNA was labeled with dUTP-fluorescein isothiocyanate using the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase enzyme. Finally, the number of fluorescent cells was determined by flow cytometry. Uninfected HUVEC untreated or treated with cytochalasin D were analyzed in parallel as negative or positive controls, respectively. As demonstrated in Fig. 5 a negligible percentage of apoptotic cells was observed in uninfected cells or endothelial cells infected with either RVFIX or RVΔUL45 (<1.6%).

FIG. 5.

Flow cytometry analyses of HUVEC stained by the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling technique. (A) Uninfected HUVEC; (B) uninfected HUVEC stained in the presence of cytochalasin D for 24 h; and (C and D) HUVEC infected at an MOI of 1 for 24 h with RVFIX or RVΔUL45. The percentage of apoptotic cells (Ap.) is indicated in each panel.

This study describes the successful cloning of a clinical isolate of HCMV with preserved wild-type characteristics of clinical isolates (FIX-BAC) and provides for the first time standard genetic material of a clinical strain suitable for mutagenesis in E. coli. Deletion of UL45 in the context of the clinical strain of HCMV did not affect the ability of the virus mutant to efficiently replicate on endothelial cells. It is known that laboratory strains (AD169, Towne, and Davis) of HCMV lose the ability to replicate in endothelial cells after extensive passaging on fibroblasts (6, 10, 16, 17). However, clinical isolates of HCMV are fully capable of replicating in a variety of cell types, including endothelial cells (19). The prediction from a recent report (3) was that an endothelial cell-tropic HCMV would induce apoptosis and lose tropism for endothelium if the M45 homolog UL45 was missing. Provided that UL45 is present in the genome of laboratory strains, one assumption was that the UL45 gene product of clinical isolates could be substantially different from that encoded by laboratory strains. However, sequence comparisons of AD169 and an endothelial cell-tropic HCMV strain did not reveal any significant sequence variation (G. Hahn, unpublished observation). To directly assess the role of UL45 of HCMV with respect to HUVEC tropism, we deleted the ribonucleotide reductase homolog UL45 in the context of FIX-BAC. The endothelial cell-tropic phenotype of the RVΔUL45 mutant was found to be comparable to that of the parental wild-type strain RVFIX, as demonstrated by growth curves in HELF and HUVEC. Thus, the dispensability of UL45 for HCMV growth in HUVEC was documented. In addition, an increase in levels of apoptotic death of HUVEC infected with RVΔUL45 mutant with respect to RVFIX was not observed. This finding may indicate a different function of UL45 with respect to its homolog M45 or the expression of additional antiapoptotic genes in clinical strains of HCMV (7, 20)

The difference in function of M45 (3) compared to that of UL45 might be surprising, given the extensive homology of M45 and UL45 to the R1 enzyme core. However, a recent report (15) suggests that the antiapoptotic function of the R1 homolog of herpes simplex virus type 2 (ICP10) is restricted to the N-terminal protein kinase domain of the enzyme (ICP10 PK), which activates the MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase survival pathway. Provided that ICP10 PK shows a greater homology to M45 than to UL45, it might be intriguing to speculate whether UL45 could complement the endothelial cell growth defect observed in an M45 deletion mutant (3). In addition, it is worth noting that the M45 studies were performed using different endothelial cells (vascular endothelial cells [SVEC4-10]) and a macrophage cell line (IC-21); therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the cell source might contribute to the differences observed. In conclusion, differential mechanisms and genes governing endothelial cell tropism in HCMV versus MCMV remain to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sylvia Rhiel and Dietlind Rose for excellent technical assistance and M. Wagner for providing the plasmid pAcyc.

This work was supported by grants from the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (to G.H.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to G.H.), the Italian Ministero della Salute, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Programma Nazionale di Ricerca sull'AIDS (50D.12 to G.G.), Ricerca Finalizzata (820RFM99/01 and ICS120.5/RF00.124 to G.G.), and Ricerca Corrente (80206 to G.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., M. Messerle, M. Wagner, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Cloning and mutagenesis of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. J. Virol. 74:6964-6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borst, E. M., G. Hahn, U. H. Koszinowski, and M. Messerle. 1999. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J. Virol. 73:8320-8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brune, W., C. Menard, J. Heesemann, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2001. A ribonucleotide reductase homolog of cytomegalovirus and endothelial cell tropism. Science 291:303-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delecluse, H. J., T. Hilsendegen, D. Pich, R. Zeidler, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1998. Propagation and recovery of intact infectious Epstein-Barr virus from prokaryotic to human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8245-8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragan, D. J., F. E. Jamieson, J. Maclean, A. Dolan, C. Addison, and D. J. McGeoch. 1997. The published DNA sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169 lacks 929 base pairs affecting genes UL42 and UL43. J. Virol. 71:9833-9836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerna, G., M. G. Revello, E. Percivalle, M. Zavattoni, M. Parea, and M. Battaglia. 1990. Quantification of human cytomegalovirus viremia by using monoclonal antibodies to different viral proteins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:2681-2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldmacher, V. S., L. M. Bartle, A. Skaletskaya, C. A. Dionne, N. L. Kendresha, C. A. Vater, J. W. Han, R. J. Lutz, S. Watanabe, E. D. Cahir McFarland, E. D. Kieff, E. S. Mocarski, and T. Chittenden. 1999. A cytomegalovirus-encoded mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis structurally unrelated to Bcl-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12536-12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horsburgh, B., M. M. Hubinette, D. Qiang, M. L. MacDonald, and F. Tufaro. 1999. Allelle replacement: an application that permits rapid manipulation of herpes simplex virus type 1 genomes. Gene Ther. 6:922-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luckow, V. A., S. C. Lee, G. F. Barry, and P. O. Olins. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 67:4566-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacCormac, L. P., and J. E. Grundy. 1999. Two clinical isolates and the Toledo strain of cytomegalovirus contain endothelial cell tropic variants that are not present in the AD169, Towne or Davis strain. J. Med. Virol. 74:7720-7729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchini, A., H. Liu, and H. Zhu. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus with IE-1 (UL122) deleted fails to express early lytic genes. J. Virol. 75:1870-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGregor, A., and M. R. Schleiss. 2001. Molecualr cloning of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Metab. 72:15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messerle, M., I. Crnkovic, W. Hammerschmidt, H. Ziegler, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1997. Cloning and mutagenesis of a herpesvirus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14759-14763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messerle, M., G. Hahn, W. Brune, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Cytomegalovirus bacterial artificial chromosomes: a new herpesvirus vector approach. Adv. Virus Res. 55:463-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins, D., E. F. R. Pereira, M. Gober, P. J. Yarowsky, and L. Aurelian. 2002. The herpes simplex virus type 2 R1 protein kinase (ICP10 PK) blocks apoptosis in hippocampal neurons, involving activation of the MEK/MAPK survival pathway. J. Virol. 76:1435-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revello, M. G., E. Percivalle, E. Arbustini, R. Pardi, S. Sozzani, and G. Gerna. 1998. In vitro generation of human cytomegalovirus pp65 antigenemia, viremia, and leukoDNAemia. J. Clin. Investig. 101:2686-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revello, M. G., F. Baldanti, E. Percivalle, A. Sarasini, L. De-Giuli, E. Genini, D. Lilleri, N. Labò, and G. Gerna. 2001. In vitro selection of human cytomegalovirus variants unable to transfer virus and virus products from infected cells to polymorphonuclear leukocytes and to grow in endothelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1429-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saeki, Y., T. Ichikawa, A. Saeki, E. A. Chiocca, K. Tobler, M. Ackermann, X. O. Breakefield, and C. Fraefel. 1998. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA amplified as bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: rescue of replication-competent virus progeny and packaging of amplicon vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:2782-2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinzger, C., A. Grefte, B. Plachter, A. S. H. Gouw, T. H. The, and G. Jahn. 1999. Fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells are major targets for human cytomegalovirus infection in lung and gastrointestinal tissues. J. Gen. Virol. 76:741-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skaletskaya, A., L. M. Bartle, T. Chittenden, A. L. McCormick, E. S. Mocarski, and V. S. Goldmacher. 2001. A cytomegalovirus-encoded inhibitor of apoptosis that suppresses caspase-8 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7829-7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith, G. A., and L. W. Enquist. 1999. Construction and transposon mutagenesis in Escherichia coli of a full-length infectious clone of pseudorabies virus, an alphaherpesvirus. J. Virol. 73:6405-6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner, M., Z. Ruzsics, and U. H. Koszinowski. Herpesvirus genetics has come of age. Trends Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Yu, D., G. A. Smith, L. W. Enquist, and T. Shenk. 2002. Construction of a self-excisable bacterial artificial chromosome containing the human cytomegalovirus genome and mutagenesis of the diploid TRL/IRL13 gene. J. Virol. 76:2316-2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]