Abstract

A fundamental question about the pathogenesis of spontaneous autoimmune diabetes is whether there are primary autoantigens. For type 1 diabetes it is clear that multiple islet molecules are the target of autoimmunity in man and animal models1,2. It is not clear whether any of the target molecules are essential for the destruction of islet beta cells. Here we show that the proinsulin/insulin molecules have a sequence that is a primary target of the autoimmunity that causes diabetes of the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse. We created insulin 1 and insulin 2 gene knockouts combined with a mutated proinsulin transgene (in which residue 16 on the B chain was changed to alanine) in NOD mice. This mutation abrogated the T-cell stimulation of a series of the major insulin autoreactive NOD T-cell clones3. Female mice with only the altered insulin did not develop insulin autoantibodies, insulitis or autoimmune diabetes, in contrast with mice containing at least one copy of the native insulin gene. We suggest that proinsulin is a primary autoantigen of the NOD mouse, and speculate that organ-restricted autoimmune disorders with marked major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction of disease are likely to have specific primary autoantigens.

Mice have two insulin genes, insulin 1 on chromosome 19, and insulin 2 on chromosome 7. Insulin 1 differs from insulin 2 by two amino acids at positions 9 and 29 on the B chain. Breeding a knockout of the insulin 2 gene (produced by J. Jami) into NOD mice results in an accelerated development of diabetes and an enhanced production of insulin autoantibodies4,5. In contrast, similar breeding of the insulin 1 knockout into the NOD mouse prevents most progression to diabetes but does not decrease the expression of insulin autoantibodies; most of these mice develop insulitis and a smaller subset progress to overt diabetes.

It has recently been reported6 that inducing recessive tolerance with a proinsulin 2 construct with an MHC class II invariant chain promoter in NOD mice greatly decreases the development of diabetes. The protection in terms of diabetes was incomplete despite low levels or absence of insulin-reactive T cells after immunization with proinsulin 1 and 2 and low levels or absence of anti-insulin autoantibodies. The authors concluded that insulin is a key but not essential antigen for diabetes of the NOD mouse. They did not use a proinsulin 1 construct; instead they showed cross-reactivity between insulin 1 and insulin 2 by in vitro assay. As the authors discussed, small numbers of insulin-reactive T cells that are not detected by their in vitro assay might mediate the incomplete prevention of autoimmune diabetes6, such as those recognizing insulin 1.

Most CD4 T cells infiltrating NOD islets react to insulin, and more than 90% recognize insulin B chain 9–23 peptide amino acids (insulin B:9–23) (ref. 7). An alanine scan of insulin B:9–23 indicated that changing the native tyrosine to alanine at insulin B chain position 16 (B16) abrogated the response of B:9–23-reactive CD4 T-cell clones3. In addition, it has been reported that a CD8 T-cell clone recognized insulin B:15–23 and the alternative mutation of tyrosine to alanine at B16 results in the failure to bind to the Kd class I MHC molecule8. We proposed that both the preproinsulin 1 and 2 B chain 9–23 sequences, differing only at position 9 (serine for insulin 2, proline for insulin 1), would be redundantly important for the development of diabetes in NOD mice and therefore produced NOD mice lacking both native insulin genes. To prevent diabetes in such mice lacking both native insulin genes (‘metabolic diabetes’) we developed preproinsulin-transgenic strains directly in NOD mice with a mutated sequence. The mutation (alanine rather than tyrosine at B16) was chosen to preserve insulin’s metabolic activity but to abrogate T-cell reactivity to B:9–23 (refs 1,3,7,9). The objective of the current study is to determine whether a complete lack of native insulin with B:9–23 sequence would abrogate the development of anti-islet autoimmunity.

Mutated preproinsulin-transgenic mice were produced directly in NOD mice. The transgene expression of two of the founder strains (strains E and H) were unable to prevent the development of diabetes in the absence of any native insulin genes (minimal expression of islet immunoreactive insulin (not shown)), with ‘early’ (for NOD) development of metabolic diabetes in the absence of insulitis (less than 10 weeks of age), whereas two other founder strains prevented this metabolic diabetes (strains B and F) and were used to analyse the development of immune-mediated diabetes in the absence of native insulin sequences.

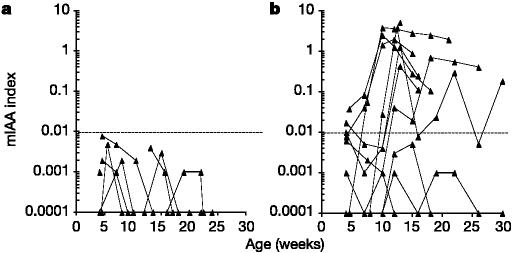

The NOD transgenic strains were combined with NOD insulin gene knockouts and prospectively evaluated for the production of insulin autoantibodies, insulitis and diabetes, relative to the presence or absence of the insulin 1 gene. As shown in Fig. 1, female mice lacking both native insulin genes (ins1-/- and ins2-/-) failed to produce insulin autoantibodies. In contrast, mice with the insulin 1 gene, despite lacking the insulin 2 gene, developed insulin autoantibodies (P < 0.0001; peak insulin auto-antibodies).

Figure 1.

Serum anti-insulin autoantibody levels. a, Insulin autoantibodies fail to occur in transgene+ mice in the absence of native insulin 1 and insulin 2 genes. b, Mice with insulin 1 gene (insulin 1+/-, insulin 2-/-, transgene+ or transgene-) produce insulin autoantibodies (IAA). Lines connect results for individual mice. mIAA, micro-IAA assay.

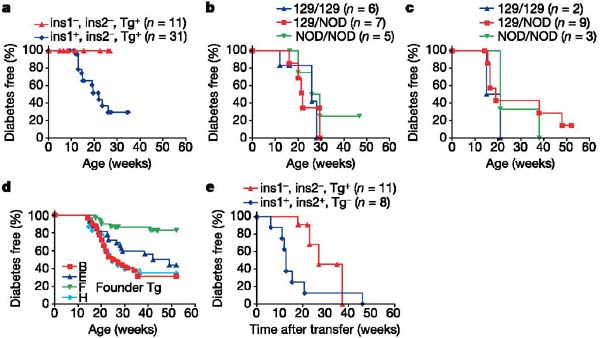

Figure 2 illustrates the histology of native insulin gene double knockout female NOD mice killed at the ages of 26 weeks (Fig. 2a–c; transgene founder strain B) or 23 weeks (Fig. 2d; transgene founder strain F). The pancreas was normal, with insulin-staining cells comprising 0.75% and 1.8%, respectively, of the pancreatic area (standard NOD mice less than 10 weeks of age (n = 10) showed an insulin-staining area ranging from 0.74% to 1.56% (median 1.2%)). There was no insulitis at 26 weeks (Fig. 2a, b) and 23 weeks (Fig. 2d) in the mice lacking native insulin. In contrast, sialitis was present at 26 weeks (Fig. 2c) and 23 weeks (not shown), indicating that as expected insulin knockouts do not prevent all autoimmunity of NOD mice but do prevent islet-specific autoimmunity. It is extremely unlikely that the insertion of the transgene disrupted a gene important for autoimmunity, given the presence of two founder strains with the same phenotype. In addition, in the presence of the native insulin genes the transgene does not prevent autoimmunity (see below).

Figure 2.

Histology of non-diabetic native insulin-negative mice (insulin 1-/-, insulin 2-/-, transgene+). Histology of pancreas and salivary gland of NOD mice lacking both native insulin 1 and 2 genes, with mutated (B16:alanine) preproinsulin transgene. a–c, Sections from a mouse killed at 26 weeks, showing islets stained for insulin (a), islets stained for glucagon (b) and salivary gland stained with haematoxylin and eosin (c). d, Islets from a mouse killed at 23 weeks, stained for insulin.

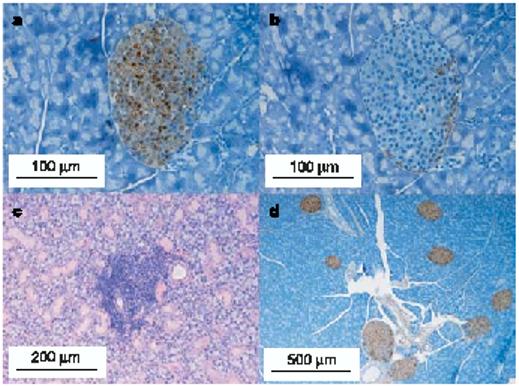

Figure 3 illustrates the histology of female mice expressing native insulin that were killed after 10 weeks of age. As expected, all diabetic mice (n = 15 of 15; three shown in Fig. 3 representing different genotypes) with at least one insulin 1 or insulin 2 gene and with or without the mutated transgene showed insulitis. Similarly, almost all non-diabetic mice killed after 20 weeks of age (n = 25 of 26, three shown in Fig. 3 representing different genotypes) showed insulitis (P < 0.01 versus double knockouts for insulin). None of the 27 insulin 1- insulin 2- islets had insulitis, in contrast to mice with native insulin genes (insulin 1+ insulin 2-: 18 islets with no insulitis (14%), 22 with peri-islet insulitis, 88 with intra-islet insulitis; insulin 1- insulin 2+: 99 with no insulitis (50%), 47 with peri-islet insulitis, 54 with intra-islet insulitis; insulin 1+ insulin 2+: 10 with no insulitis (23%), 16 with peri-islet insulitis, 18 with intraislet insulitis; P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Histology of native insulin-positive mice. Histology showing marked insulitis of NOD mice with one or more copies of the insulin 1 or insulin 2 gene, with or without the mutated preproinsulin (B16:alanine) transgene. a, Insulin 1+/+, insulin 2-/-, transgene-, killed at 14 weeks, diabetic at 14 weeks. b, Insulin 1+/+, insulin 2-/-, transgene-, killed at 10.5 weeks, diabetic at 10.5 weeks. c, Insulin 1+/-, insulin 2-/-, transgene+, killed at 15 weeks, diabetic at 15 weeks. d, Insulin 1-/-, insulin 2+/+, transgene-, killed at 20 weeks, not diabetic. e, Insulin 1-/-, insulin 2+/+, transgene+, killed at 21 weeks, not diabetic. f, Insulin 1-/-, insulin 2+/-, transgene+, killed at 35 weeks, not diabetic.

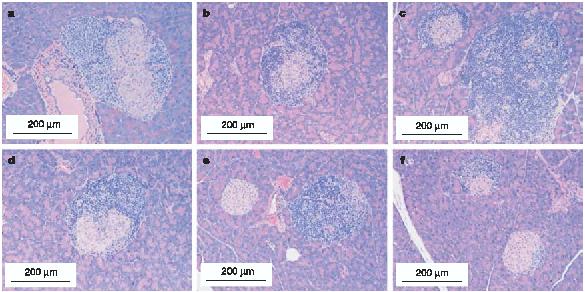

As shown in Fig. 4a, none of the mice lacking the native sequences of both insulin 1 and insulin 2 developed diabetes, which is consistent with their lack of insulitis. In contrast, the presence of insulin 1 restored the development of diabetes (75% of mice were diabetic at 25 weeks, by life-table analysis; Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Life tables of diabetes development. a, Lack of progression to diabetes of NOD mice lacking both insulin native genes. b, c, Lack of difference in progression to diabetes for speed congenic female NOD mice with control regions from the 129 mouse surrounding the insulin genes (insulin 1 region (b); insulin 2 region (c)). d, Progression to diabetes of the four transgenic founder strains with the mutated preproinsulin gene on NOD background (insulin 1+/+, insulin 2+/+, transgene+). Founder strain F was significantly different (P < 0.01) from the others. e, NOD.SCID recipients of splenocytes from mice lacking both native insulin genes had delayed progression to diabetes compared with insulin 1+, insulin 2+ mice (P < 0.02). ins, insulin; Tg, transgene.

To exclude the possibility that the prevention of diabetes was related to the chromosomal region from 129 mice of the knockouts bred into the NOD or of the mutated preproinsulin transgene, we analysed the progression to diabetes of multiple control crosses. Figure 4 shows that fixing the control (non-knockout) chromosomal region surrounding the insulin genes (speed congenics backcross no. 6 for the insulin 1 region, backcross no. 4 for the insulin 2 region) on the NOD background did not alter the development of diabetes (Fig. 4b, insulin 1 region; Fig. 4c, insulin 2 region). In addition, all transgenic founder strains with the mutated preproinsulin gene showed progression to diabetes (Fig. 4d) and insulitis (not shown), with founder strain F having a modest decrease in progression to diabetes and the highest thymic expression of insulin messenger RNA (mRNA data not shown), which might affect autoreactive or regulatory T-cell development with the modified B:9–23 insulin (B16:alanine) or other proinsulin epitopes of the transgene.

To determine whether functional ‘diabetogenic’ splenocytes could be detected in the insulin knockout mice, we harvested spleen cells from insulin gene double-knockout and wild-type NOD mice and transferred them into immunodeficient (severe combined immunodeficiency; SCID) NOD recipients. Splenocytes were obtained from mice between 9 and 26 weeks of age, a time at which accelerated transfer of diabetes is observed for standard NOD mice. Whereas 75% of recipients were diabetic by 8 weeks after the transfer of wild-type splenocytes, recipients of splenocytes from insulin gene double-knockout NOD mice had a marked delay in developing diabetes (Fig. 4e; P < 0.02). These splenocytes from the insulin gene double-knockout NOD mouse induced diabetes 2–4 months after transfer into the NOD.SCID mice. The recipient mice expressed native insulin 1 and insulin 2 in their islets, but this experiment does not prove that normal insulin or insulin B:9–23 is the major target of the transferred cells. The long period to diabetes induction by splenocytes from mice lacking native insulin genes, when transferred into mice with native-insulin-containing islets, indicates the possible development of pathogenic T-cell responses after splenocyte transfer.

Type 1A diabetes is characterized by specific destruction of the cells within the pancreas that produce insulin10, and alleles of class II MHC genes are major determinants of disease in both humans and animal models11,12. Risk of type 1A diabetes varies by more than 1,000-fold depending on the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) DQ genotypes in man. One hypothesis to account for these potent MHC associations and beta-cell-specific destruction is to posit that the immune response for a given genotype (with immune dysregulation and environmental factors) is dependent on an antigen whose targeting is essential for disease. T-cell clones reacting with multiple antigens of the islets, including novel molecules induced to be expressed within islets, are able to transfer diabetes, providing strong evidence that multiple actual and potential islet targets exist. However, there is evidence that glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65), insulinoma antigen 2 (IA-2), IA-2b /phogrin and heat shock protein 60 (hsp60) are not essential autoantigens of the spontaneous NOD mouse, in that mice develop diabetes despite the removal of the antigen or antigen-responding T cells13–17.

Our studies indicate that insulin peptide B:9–23 might be an essential target of the immune destruction of the NOD mouse, although it is possible that the processing of other epitopes in the proinsulin molecule might be affected by the single amino-acid mutation at position B16, and there is the caveat that mutated proinsulin (B16:alanine) transgene expression might not be permissive for islet autoimmunity. There is at present considerable evidence that insulin is an important target molecule, despite evidence for many additional relevant targets18–20. Expression of proinsulin in transgenic lymphoid organs or modulating the immune response to insulin can greatly decrease the development of diabetes6,21,22.

Our studies provide evidence that the development of insulin autoantibodies, insulitis and diabetes is dependent on native insulin gene sequences. Absence of insulitis in the presence of sialitis indicates that this influence might be organ-specific. Multiple studies indicate that both insulin 1 and insulin 2, which differ by only 2 of 51 amino acids, can be the target of autoimmunity. If primary autoantigenic targets exist for specific autoimmune disorders with specific MHC genotypes, we believe it likely that deletional therapies may allow potent disease prevention. Such deletional therapies may be more robust than regulatory experimental manipulations, which usually do not abrogate insulitis23,24. At a minimum, the induction of this deletional tolerance might be a preventive pathway synergistic to the harnessing of regulatory T-cell responses. □

Methods

Mice

Insulin 1 and insulin 2 knockout NOD mice were established by breeding the original insulin knockouts provided by J. Jami into NOD/Bdc mice with the use of speed congenic techniques5. The original insulin knockout mice were produced in 129S1/SvImJ embryonal cell lines25. Mutated preproinsulin-transgenic NOD mice were produced by the microinjection of mutated preproinsulin 2 complementary DNA constructs ligated to the pRIP7 (rat insulin 7) promoter directly into fertilized NOD oocytes as described previously26. Female mice were used for the study.

To rule out potential effects of 129S1/SvImJ genes in linkage with the insulin gene, the mice, which have the 129S1/SvImJ gene at insulin 1 (position 49 cM at chromosome 19) or insulin 2 (position 69.1 cM at chromosome 7) locus on the NOD background, were produced with the use of speed congenic methods. We bred 129S1/SvImJ mice with NOD/Bdc mice, and NOD diabetogenic loci (idd 1–14) were fixed by backcross 3. Both strains were further backcrossed into NOD/Bdc mice. 129S1/SvImJ genomic regions flanking each insulin gene locus are less than 18 cM for the insulin 1 region-fixed mice and less than 19 cM for the insulin 2 region mice; the central 129 regions without the knockouts spanned these regions. Female mice were studied.

Immunodeficient NOD mice (NOD.SCID) for the adaptive transfer experiment were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal colony at Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes using an approved protocol from the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

Insulin autoantibody (IAA) assay

IAAs were measured with a 96-well filtration plate micro-IAA assay as described previously27 and expressed as an index. A value of 0.01 or greater is considered positive.

Histology

The pancreata and salivary glands obtained from the mice were fixed in 10% formalin, then embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and parallel sections were also stained with polyclonal guinea-pig anti-insulin or anti-glucagon antibodies (Linco Research Inc.), followed by incubation with a peroxidase-labelled anti-guinea-pig IgG antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). For the scoring of insulitis, each islet was scored as no insulitis, peri-islet insulitis and intra-islet insulitis by a reader blinded to the categories of the mice. To calculate the insulin-positive area we modified the method of measurement of beta-cell mass in ref. 28. An Olympus BX51 microscope connected to a high-resolution digital camera (Pixera) and the software Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) was used. Pancreas and islet areas were measured in a randomly selected 10–15 views at a final magnification of ×400. Subsequently, islet area and insulin-positive area were measured at ×1,000 magnification. The insulin-positive area divided by the pancreatic area was calculated as (insulin-positive area at ×1,000/islet area at ×1,000)/(islet area at ×400/pancreatic area at ×400).

Diabetes

Glucose was measured weekly with the FreeStyle blood glucose monitoring system (TheraSense), and the mice were considered diabetic after two consecutive blood glucose values of more than 250 mg dl-1.

Adoptive transfer experiments

Splenocytes (3 × 107) from native insulin-negative NOD mice or standard NOD mice were injected intraperitoneally into 8-week-old NOD.SCID mice and the mice were followed for the development of hyperglycaemia.

Statistics

The peaks of insulin autoantibodies were analysed with Student's t-tests. The presence of insulitis was analysed with the Fisher exact test. Survival curves were analysed with the log-rank test. Statistical tests used PRISM software (Graphpad).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the NIH, the Diabetes Endocrine Research Center, the Autoimmunity Prevention Center, the Immune Tolerance Network, the American Diabetes Association, the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation and the Children's Diabetes Foundation. M.N. was supported by a fellowship from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation and the Naito Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Wegmann DR, Norbury-Glaser M, Daniel D. Insulin-specific T cells are a predominant component of islet infiltrates in pre-diabetic NOD mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:1853–1857. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman SM, et al. Identification of the β cell antigen targeted by a prevalent population of pathogenic CD8 T cells in autoimmune diabetes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8384–8388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932778100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abiru N, et al. Dual overlapping peptides recognized by insulin peptide B:9–23 T cell receptor AV13S3 T cell clones of the NOD mouse. J. Autoimmun. 2000;14:231–237. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thébault-Baumont K, et al. Acceleration of type 1 diabetes mellitus in proinsulin 2-deficient NOD mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:851–857. doi: 10.1172/JCI16584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriyama H, et al. Evidence for a primary islet autoantigen (preproinsulin 1) for insulitis and diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10376–10381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaeckel E, Lipes MA, von Boehmer H. Recessive tolerance to preproinsulin 2 reduces but does not abolish type 1 diabetes. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:1028–1035. doi: 10.1038/ni1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniel D, Gill RG, Schloot N, Wegmann D. Epitope specificity, cytokine production profile and diabetogenic activity of insulin-specific T cell clones isolated from NOD mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:1056–1062. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong FS, Moustakas AK, Wen L, Papadopoulos GK, Janeway CA., Jr. Analysis of structure and function relationships of an autoantigenic peptide of insulin bound to H-2Kd that stimulates CD8 T cells in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5551–5556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072037299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simone E, et al. T cell receptor restriction of diabetogenic autoimmune NOD T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2518–2521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mordes JP, Bortell R, Blankenhorn EP, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Rat models of type 1 diabetes: genetics, environment, and autoimmunity. ILAR J. 2004;45:278–291. doi: 10.1093/ilar.45.3.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Todd JA, Bell JI, McDevitt HO. HLA-DQβ gene contributes to susceptibility and resistance to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Nature. 1987;329:599–604. doi: 10.1038/329599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellerman KE, Like AA. Susceptibility to diabetes is widely distributed in normal class IIu haplotype rats. Diabetologia. 2000;43:890–898. doi: 10.1007/s001250051466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubosaki A, et al. Targeted disruption of the IA-2β gene causes glucose intolerance and impairs insulin secretion but does not prevent the development of diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2004;53:1684–1691. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaeckel E, Klein L, Martin-Orozco N, von Boehmer H. Normal incidence of diabetes in NOD mice tolerant to glutamic acid decarboxylase. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1635–1644. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kash SF, Condie BG, Baekkeskov S. Glutamate decarboxylase and GABA in pancreatic islets: lessons from knock-out mice. Horm. Metab. Res. 1999;31:340–344. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birk OS, et al. A role of Hsp60 in autoimmune diabetes: analysis in a transgenic model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1032–1037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubosaki A, Miura J, Notkins AL. IA-2 is not required for the development of diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetologia. 2004;47:149–150. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiLorenzo TP, et al. During the early prediabetic period in NOD mice, the pathogenic CD8+ T-cell population comprises multiple antigenic specificities. Clin. Immunol. 2002;105:332–341. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathis D, Benoist C. Back to central tolerance. Immunity. 2004;20:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson JD, Haskins K. Transfer of diabetes in the NOD-scid mouse by CD4 T-cell clones. Differential requirement for CD8 T-cells. Diabetes. 1996;45:328–336. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.French MB, et al. Transgenic expression of mouse proinsulin II prevents diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Diabetes. 1996;46:34–39. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee R, Chaturvedi P, Qin HY, Singh B. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells generated in response to insulin B:9–23 peptide prevent adoptive transfer of diabetes by diabetogenic T cells. J. Autoimmun. 2003;21:221–237. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatenoud L, Primo J, Bach JF. CD3 antibody-induced dominant self tolerance in overtly diabetic NOD mice. J. Immunol. 1997;158:2947–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bluestone JA, Tang Q. Therapeutic vaccination using CD4+ CD25+ antigen-specific regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(suppl 2):14622–14626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405234101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duvillié B, et al. Phenotypic alterations in insulin-deficient mutant mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5137–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakayama M, et al. Establishment of native insulin-negative NOD mice and the methodology to distinguish specific insulin knockout genotypes and a B:16 alanine preproinsulin transgene. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2004;1037:193–198. doi: 10.1196/annals.1337.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu L, et al. Early expression of antiinsulin autoantibodies of humans and the NOD mouse: evidence for early determination of subsequent diabetes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1701–1706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040556697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sreenan S, et al. Increased β-cell proliferation and reduced mass before diabetes onset in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Diabetes. 1999;48:989–996. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]