Abstract

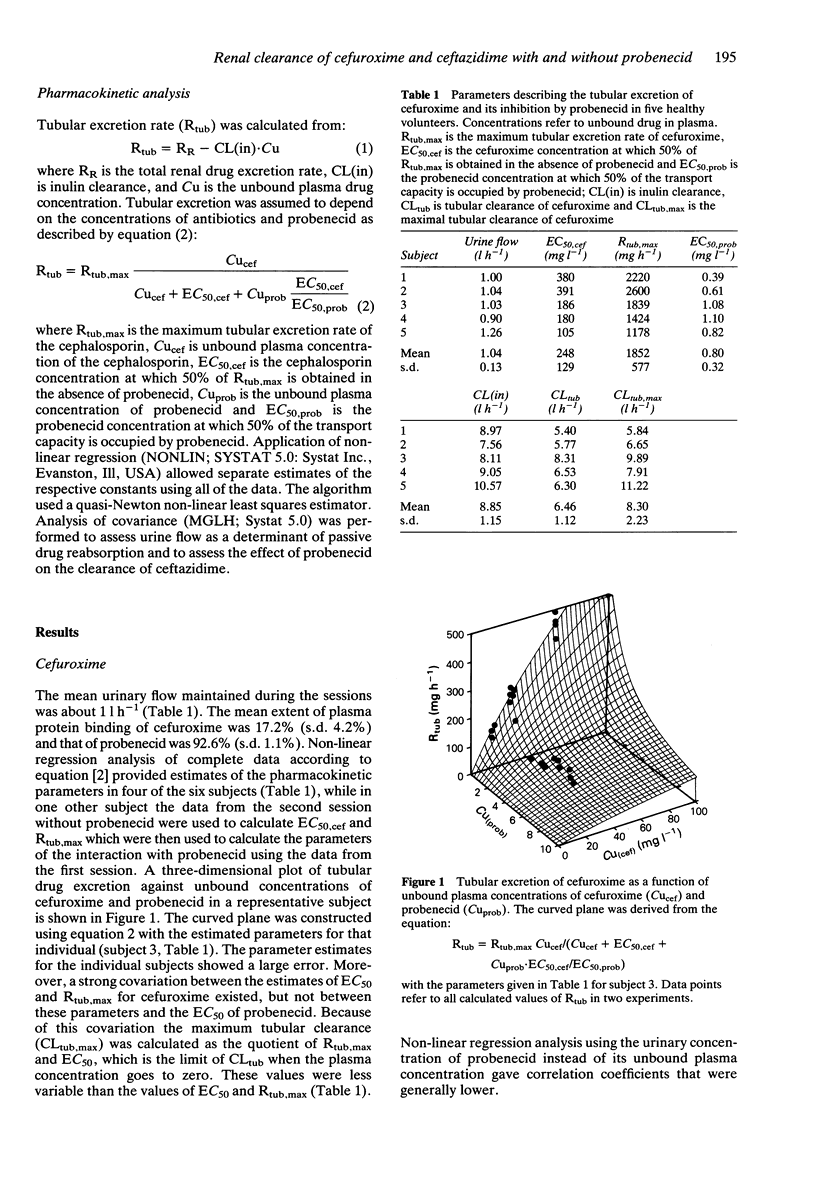

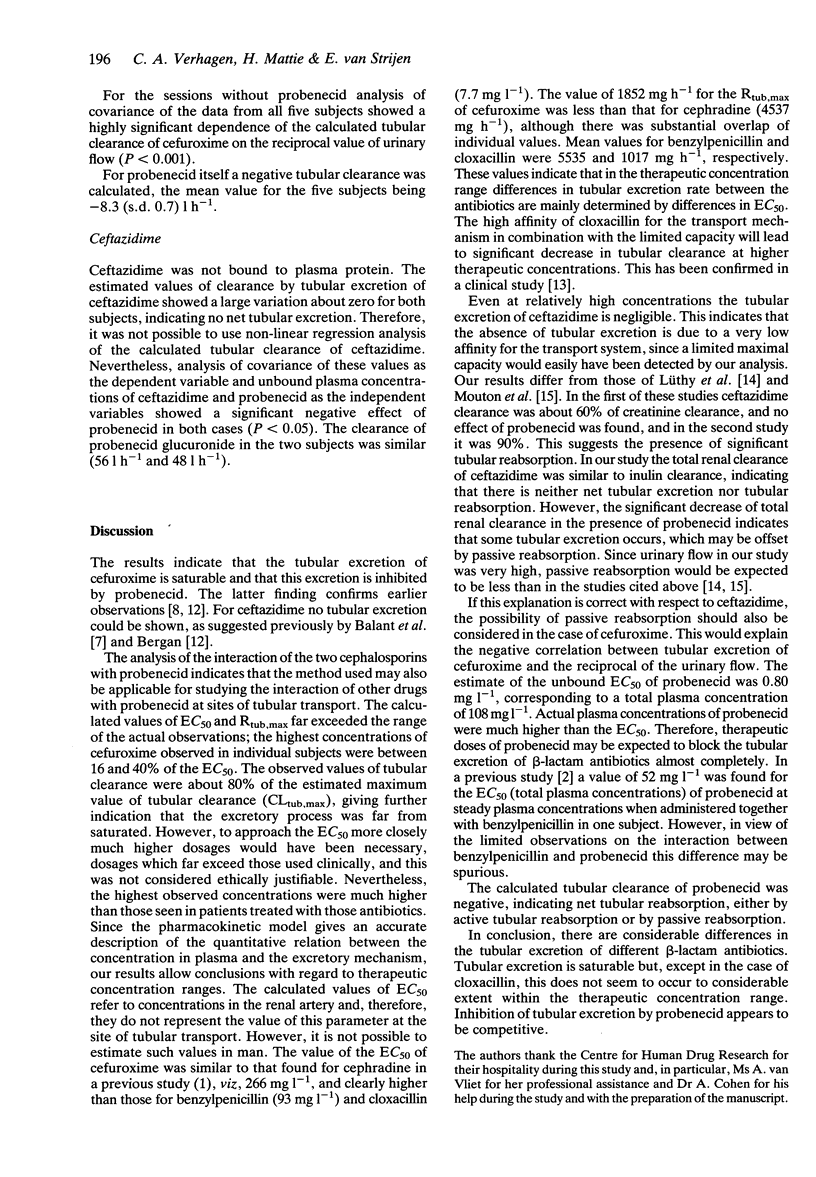

1. The renal tubular excretion of cefuroxime and ceftazidime in relation to the coadministration of probenecid was investigated in eight and two healthy subjects, respectively. 2. Cefuroxime or ceftazidime were administered by i.v. infusion and 1 g probenecid was administered orally after steady state plasma concentrations of the cephalosporin were reached. 3. In a second session the same antibiotic was administered at increasing infusion rates such that three different levels of plasma drug concentration were achieved. 4. The renal clearance of antibiotic was calculated based upon unbound plasma concentration, and tubular clearance was estimated by subtracting inulin clearance from the renal clearance of the antibiotic. 5. Non-linear regression analysis was used to estimate parameters describing the saturability of tubular excretion and the effect of probenecid inhibition, i.e. EC50 and Rtub,max, could be established for cefuroxime: EC50 was 248 (s.d. 130) mg l-1 and Rtub,max was 1.852 (s.d. 0.577) mg h-1. Tubular excretion of ceftazidime was practically zero. The EC50 of probenecid for inhibition of the tubular excretion of cefuroxime was 0.80 (s.d. 0.31) mg l-1. 6. The results indicate that in the therapeutic plasma concentration range of cefuroxime its renal clearance is not saturated. Probenecid at therapeutic doses will block tubular excretion of cefuroxime almost completely.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Balant L., Dayer P., Auckenthaler R. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the third generation cephalosporins. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985 Mar-Apr;10(2):101–143. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198510020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergan T. Pharmacokinetic properties of the cephalosporins. Drugs. 1987;34 (Suppl 2):89–104. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198700342-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bins J. W., Mattie H. Saturation of the tubular excretion of beta-lactam antibiotics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988 Jan;25(1):41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb03280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogden R. N., Heel R. C., Speight T. M., Avery G. S. Cefuroxime: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacological properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1979 Apr;17(4):233–266. doi: 10.2165/00003495-197917040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham R. F., Israili Z. H., Dayton P. G. Clinical pharmacokinetics of probenecid. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1981 Mar-Apr;6(2):135–151. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198106020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEYROVSKY A. A new method for the determination of inulin in plasma and urine. Clin Chim Acta. 1956 Sep-Oct;1(5):470–474. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(56)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthy R., Blaser J., Bonetti A., Simmen H., Wise R., Siegenthaler W. Comparative multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime, moxalactam, and ceftazidime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Nov;20(5):567–575. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattie H., van der Voet G. B. The relative potency of amoxycillin and ampicillin in vitro and in vivo. Scand J Infect Dis. 1981;13(4):291–296. doi: 10.3109/inf.1981.13.issue-4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton J. W., Horrevorts A. M., Mulder P. G., Prens E. P., Michel M. F. Pharmacokinetics of ceftazidime in serum and suction blister fluid during continuous and intermittent infusions in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 Dec;34(12):2307–2311. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.12.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbosch D., Van Gulpen C., Hermans J., Mattie H. The effect of probenecid on the renal tubular excretion of benzylpenicillin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988 Jan;25(1):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb03281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennick B. R. Renal tubule transport of organic cations. Am J Physiol. 1981 Feb;240(2):F83–F89. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.240.2.F83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser L. G., Arnouts P., van Furth R., Mattie H., van den Broek P. J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of continuous intravenous administration of penicillins. Clin Infect Dis. 1993 Sep;17(3):491–495. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels J. F., Huysmans F. T., Koene R. A. Creatinine as a marker of glomerular filtration rate. Neth J Med. 1988 Oct;33(3-4):144–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gulpen C., Brokerhof A. W., van der Kaay M., Tjaden U. R., Mattie H. Determination of benzylpenicillin and probenecid in human body fluids by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1986 Sep 5;381(2):365–372. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]