Abstract

Mice of the PERA/Ei strain (PE mice) are highly susceptible to tumor induction by polyomavirus and transmit their susceptibility in a dominant manner in crosses with resistant C57BR/cdJ mice (BR mice). BR mice respond to polyomavirus infection with a type 1 cytokine response and develop effective cell-mediated immunity to the virus-induced tumors. By enumerating virus-specific CD8+ T cells and measuring cytokine responses, we show that the susceptibility of PE mice is due to the absence of a type 1 cytokine response and a concomitant failure to sustain virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. (PE × BR)F1 mice showed an initial type 1 response that became skewed toward type 2. Culture supernatants of splenocytes from infected PE mice stimulated in vitro contained high levels of interleukin-10 and no detectable gamma interferon, while those from BR mice showed the opposite pattern. Differences in the innate immune response to polyomavirus by antigen-presenting cells in PE mice and BR mice led to polarization of T-cell cytokine responses. Adherent cells from spleens of infected BR mice produced high levels of interleukin-12, while those from infected PE and F1 mice produced predominantly interleukin-10. PE and F1 mice infected by polyomavirus responded with increases in antigen-presenting cells expressing B7.2 costimulatory molecules, whereas BR mice responded with increased expression of B7.1. Administration of recombinant interleukin-12 along with virus resulted in partial protection of PE mice and provided complete protection against tumor development in F1 animals.

Inbred strains of mice vary enormously in their responses to the potentially highly oncogenic polyomavirus. In highly susceptible strains, 100% of the animals rapidly develop multiple tumors. In highly resistant strains, no tumors develop in any animal over the entire life span. Some strains show intermediate phenotypes in which overall tumor incidences are low or in which tumors develop at some sites but not at others, as well as ones in which particular tumor types behave more aggressively than in other strains (3, 14). Efforts to understand the genetic and biological bases of these variations should provide important information about host responses that prevent and allow tumor development. They may also indicate ways of intervening to block the development of tumors in susceptible hosts.

Most resistant strains owe their resistance to effective cell-mediated immune responses against polyomavirus tumors. As one example, C57BR/cdJ mice (BR mice) infected as newborns show extensive virus spread but fail to develop tumors (11). This is due to an antitumor immune response mediated largely by Dk-restricted Vβ6+ CD8+ T cells specific for an immunodominant peptide derived from the viral middle T protein (13). A less common and distinctly different form of resistance has also been described in which virus spread is curtailed by an apparently nonimmunological mechanism (4).

Control of simian virus 40 tumor cell growth has been shown to depend on expansion of viral epitope-specific CD8+ T cells and production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (17). The generation and maintenance of functional CD8 T cells in persistent viral infections can be regulated at multiple levels (23). In the polyomavirus system, at least two distinct mechanisms underlie tumor susceptibility, each arising from an inability to mount or sustain CD8+ T-cell responses. One is found in certain of the classical inbred strains bearing the H-2k haplotype and is based on a specific endogenous mouse mammary tumor virus superantigen. This superantigen acts in a dominant manner by deleting Vβ6+ T cells that are essential on an H-2k background for elimination of polyomavirus tumors (5, 11).

A different basis of susceptibility is found among some more recent wild-derived inbred strains, such as the PERA/Ei strain (PE mice). PE mice carry the H-2k haplotype but are free of endogenous mammary tumor viruses (22). Despite the presence of the expected T-cell precursors, PE mice are highly susceptible and transmit their susceptibility as a dominant or codominant trait in crosses with BR mice (22). The basis of this superantigen-independent form of tumor susceptibility is unknown, but it is presumed to act by a mechanism that overrides the protective immune responses normally generated by BR mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains.

C57BR/cdJ (BR) and PERA/Ei (PE) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). All mice were bred and maintained in our virus antibody-free barrier facility prior to use in the experiments.

Virus inoculation.

The PTA and A2+ wild-type strains of polyomavirus were used (6). Newborn animals (<16 h old) were inoculated intraperitoneally with ∼50 μl of virus suspension containing ∼106 PFU. Animals were sacrificed at different times for immunological studies as indicated in the text or necropsied when moribund for tumor studies.

Recombinant IL-12 treatment.

For studies of T-cell functions, newborn mice were given a single intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 μg of recombinant murine interleukin-12 (IL-12; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.), followed 1 h later by virus. For tumor studies, mice received three intraperitoneal injections of IL-12, 0.25 μg on day 1, 0.5 μg on day 5, and 0.75 μg on day 10. Virus was given on day 1, 1 h after the first IL-12 injection.

Polyomavirus middle T peptide.

Dk-restricted polyomavirus middle T peptide (MT-389; RRLGRTLLL) was synthesized at the Biopolymer Laboratory, Harvard Medical School. The MT-389 peptide stock solution (2 mM) was made in distilled water and stored at −80°C. Shortly before use, the peptide was diluted in Iscove's modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) containing l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, penicillin-streptomycin, 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (complete IMDM).

Preparation of MT-389/Dk tetramers.

The MT-389/Dk tetramers were obtained through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Tetramer Core Facility and the National Institutes of Health (Rockville, Md.) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The tetramers were prepared as previously described (12) by mixing biotinylated MT-389/Dk monomers with allophycocyanin-conjugated streptavidin in a 4:1 molar ratio.

Cytofluorometric analysis.

Total splenic leukocytes were obtained following lysis of erythrocytes in ammonium chloride solution (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM disodium EDTA). Spleen cells (106) were stained in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% FCS and 0.01% sodium azide. Cells were first incubated with purified rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 monoclonal antibody (MAb) and then with fluorochrome-labeled MAbs or isotype control immunoglobulins (PharMingen). Cells were incubated for 1 h at 4°C, followed by three washes in buffer, and fixed in PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde. Fluorescence-activated cell scanning (FACS) was performed on a Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, Calif.) FACScan with Cell-Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

For staining polyomavirus-specific T cells (12), splenocytes from infected mice were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8a MAb, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse Vβ6 MAb, and allophycocyanin-conjugated MT-389/Dk tetramers. Spleen cells from infected mice were double stained by incubation with FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse B220 or hamster anti-mouse CD11c and phycoerythrin-conjugated hamster anti-mouse B7.1 or rat anti-mouse B7.2 MAb.

Generation of cell culture supernatants.

Leukocytes (5 × 106) from spleens of infected mice were incubated in complete IMDM for 2 h at 37°C in 24-well tissue culture clusters. Subsequently, the nonadherent cells were removed by gentle aspiration of the cell suspension. The adherent cells were further cultured in complete IMDM for 36 h, and then the supernatants were harvested for cytokine analysis. Spleen cells were obtained from infected mice at different times and cultured in 24-well tissue culture clusters. Two million cells/well were stimulated with 10 μM MT-389 peptide in 0.5 ml of complete IMDM at 37°C for 36 h. The supernatants were harvested for cytokine analysis.

Ex vivo CTL assay.

Pools of spleen cells from three mice were collected at different times postinfection. Ten million cells were stimulated with 5 μM MT-389 peptide overnight at 37°C in 90-mm petri dishes. In some experiments, cells were stimulated as above in the presence of 100 U of murine IFN-γ (PharMingen) per ml. The cells were washed in complete IMDM and used as effector cells in the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay (22).

L929 (H-2k) cells from the American Type Culture Collection were maintained in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. L929 target cells (3 × 106) were radiolabeled by the addition of 200 μCi of Na251CrO4 (NEN, Boston, Mass.) in complete IMDM containing 5% FCS and simultaneously pulsed in the presence of 10 μM MT-389 peptide. The cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 90 min, washed three times in complete IMDM, and then used as the target in the CTL assay (22).

Targets (5 × 103 cells/well) were incubated in 96-well U-bottomed tissue culture clusters along with the effector cells (250 × 103 cells/well). After incubation for 4 h at 37°C, cell-free supernatant (100 μl) from each well was collected, and radioactivity was counted on a gamma counter. Spontaneous and total 51Cr release was counted from targets incubated with medium alone and with 1% Triton X-100, respectively. The spontaneous release in all assays was less than 15% of the total lysis. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as [(lysis with effector cells − spontaneous release)/(total lysis − spontaneous release)] × 100. Each assay was carried out in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least twice with essentially identical results.

Detection of cytokines.

A two-site capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to detect cytokines in the cell culture supernatants (21). Pairs of matched rat MAbs specific to murine IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-12 (p70) and the relevant recombinant proteins as standards were all purchased from PharMingen. Polystyrene microtiter plates (Dynex, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with 2 μg (50 μl/well) of murine cytokine-specific purified MAbs per ml. The plates were incubated overnight at 4°C, washed in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and blocked with PBS containing 10% FCS. The culture supernatants were then added to wells and incubated overnight at 4°C for capture of cytokines. The wells were washed, followed by addition of 1 μg (100 μl/well) of biotinylated MAbs per ml, and allowed to stand at room temperature for 2 h. Avidin-peroxidase (Sigma) was used as a detection system in the presence of tetramethylbenzidine as substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, Md.). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in an ELISA microplate reader (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.). Serial dilutions of recombinant cytokine proteins were included to construct a standard curve for quantitating the amount of cytokine in the culture supernatants.

RESULTS

Polyomavirus-specific T cells in spleens of infected parental and F1 mice.

PE mice bear the H-2k haplotype and are free of endogenous mouse mammary tumor viruses (22). They are thus expected to retain Vβ6+ CD8+ T cells with the potential to develop into polyomavirus-specific CTLs, as occurs in resistant BR mice, which also carry the H-2k haplotype and are free of the critical mammary tumor virus (11). To identify and determine the fate of virus-specific T cells, splenocytes were harvested from control and neonatally infected PE mice, BR mice, and (PE × BR)F1 mice at different times. Virus-specific Vβ6+ CD8+ T cells were enumerated by FACS with labeled Dk tetramers assembled with viral peptide MT-389.

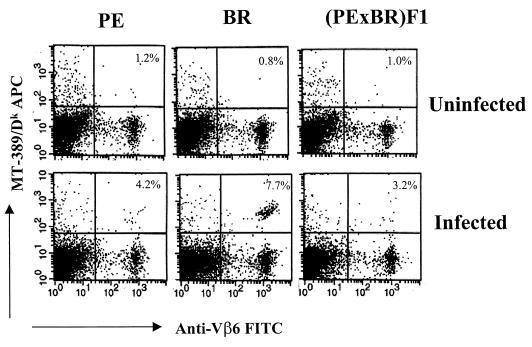

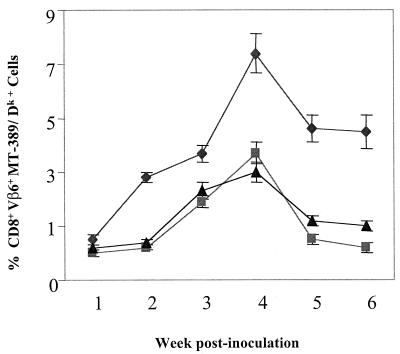

At 4 weeks postinfection, cells from infected BR animals showed a nearly 10-fold increase in triple-positive cells (Vβ6+, CD8+, and MT-389/Dk+) compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 1). PE mice and F1 mice also contained triple-positive cells and responded to infection with increases of three- to fourfold. These results confirm that susceptible PE mice and their F1 progeny harbor the essential T-cell precursors and indeed generate an initial response to the virus. Neonatally infected mice were tested weekly over a 6-week period (Fig. 2). The response in BR mice peaked at around 4 weeks and fell off only slightly thereafter. In contrast, the initial responses seen in PE mice and F1 mice were not sustained. By 5 to 6 weeks, triple-positive cells in these mice fell to background levels of around 1%, i.e., levels that were similar to or lower than those found in infected non-H2k mice expressing Vβ6 (2.2%) or H-2k mice from which Vβ6 cells were deleted (1.5%).

FIG. 1.

Enumeration of polyomavirus-specific CD8 T cells in spleen. Spleen cells from uninfected or polyomavirus-infected (PTA strain, intraperitoneally) mice were harvested at 4 weeks postinfection. Spleen cells were pooled from at least three mice in each group. One million cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD8a, allophycocyanin-conjugated MT-389/Dk tetramers, and FITC-labeled anti-Vβ6. The stained cells were analyzed on a FACScan. Each panel is a representative of one of three experiments in each group. The FACS events shown were gated on CD8+ T cells. The values in the upper right-hand corners are the percentages of MT-389/Dk+ Vβ6+ among the CD8+ T cells. The percentages of positive cells in the spleens of C3H/BiDa (H-2k haplotype, with no Vβ6 T cells) and CZECH II/Ei (non-H-2k haplotype, with Vβ6+ T cells) control mice were 1.5 and 2.2%, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Polyomavirus-specific CD8 T cells: time kinetics. Spleen cells from polyomavirus-infected mice were harvested at the indicated times postinfection, stained, and then analyzed as described for Fig 1. Symbols represent the mean ± standard error of three experiments performed at the indicated time points. ♦, BR mice; ▪, PE mice; ▴, F1 mice.

Spleen cells harvested from infected mice at different times were stimulated overnight with viral peptide and incubated with 51Cr-labeled target cells at a 50:1 effector-to-target cell ratio (Fig. 3). The results show that in PE and F1 as well as BR mice, CTL activity rose over the first 4 weeks, roughly in parallel with the appearance of triply positive cells, as enumerated by FACS analysis (Fig. 2). However, CTL activity declined sharply over weeks 5 and 6 in PE mice and F1 mice but was maintained in BR mice. Thus, susceptible PE mice and their F1 progeny mount an initial virus-specific CTL response that is not sustained.

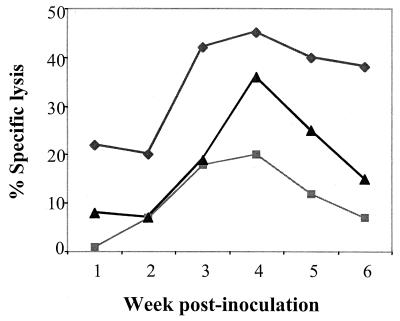

FIG. 3.

Ex vivo CTL activity in spleens of polyomavirus-infected mice. Spleen cells from polyomavirus-infected mice at the indicated times postinfection were stimulated overnight at 37°C with 5 μM MT-389 peptide, washed in IMDM containing 10% FCS, and subsequently used as the effector cells in the CTL assay. The MT-389 (10 μM) peptide-pulsed, 51Cr-labeled L929 (H-2k) cells were used as the targets. The CTL assays were carried out in the wells of 96-well U-bottomed plates at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 50:1. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown are the means of triplicate wells at each point. The experiment was repeated twice with identical results. The lysis of scrambled MT-389-pulsed L929 cells by spleens of infected mice and the lysis of MT-389-pulsed L929 cells by normal splenocytes were 2% and 3%, respectively. ♦, BR mice; ▪, PE mice; ▴, F1 mice.

Cytokine production in vitro by splenocytes from infected mice.

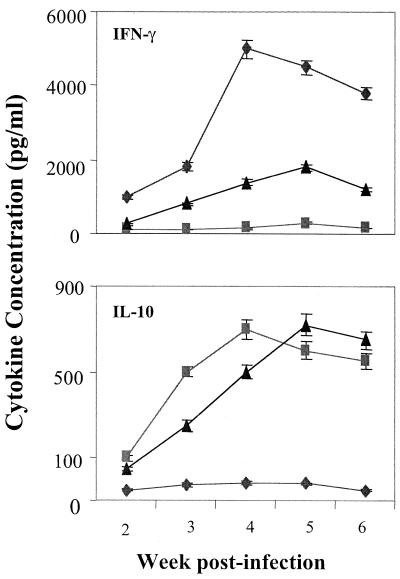

IFN-γ, a key type 1 cytokine, is critical for generating sustained CD8 T-cell responses, while type 2 cytokines such as IL-10 oppose the functions of type 1 T cells (1). To determine whether tumor resistance versus susceptibility correlates with type 1 versus type 2 cytokine responses, splenocytes were harvested at different times from infected mice and stimulated in vitro with viral peptide. Levels of secreted IFN-γ and IL-10 were measured (Fig. 4). IFN-γ levels rose rapidly to very high levels in cultures from BR mice but remained at barely detectible levels in cultures from PE mice throughout the 6-week period. Splenocytes from F1 animals produced low levels of IFN-γ that rose slightly and then declined. In contrast, IL-10 rose sharply in PE mice but remained low in BR mice. F1 mice also showed a strong IL-10 response that was similar in magnitude but slightly delayed compared to that of the PE mice. Among other cytokines tested, IL-2 levels rose equally in response to viral peptide in splenocyte cultures from infected PE mice, BR mice, and F1 mice, while IL-4 and IL-5 levels remained undetectable in cultures from all three mouse strains (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cytokine responses to MT-389 stimulation. Spleen cells from polyomavirus-infected mice at the indicated times postinfection were stimulated in vitro with 10 μM MT-389 peptide in IMDM containing 10% FCS. The cells were cultured at 37°C for 36 h, and then the supernatants were harvested. The levels of cytokines were measured by double-sandwich ELISA. Values shown are the mean ± standard error of three experiments. The cytokine levels of spleen cells from uninfected age-matched controls stimulated with MT-389 peptide and the spleen cells from infected mice stimulated with scrambled MT-389 were all less than 25 pg/ml. ♦, BR mice; ▪, PE mice; ▴, F1 mice.

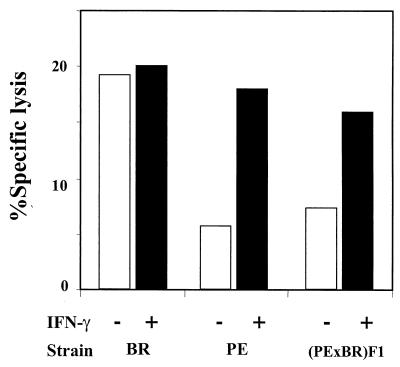

To confirm that PE mice and F1 mice are not constitutively unable to produce IFN-γ, splenocytes from uninfected mice were stimulated in vitro with surface-bound anti-CD3. Levels of secreted IFN-γ rose sharply and equally in splenocyte cultures regardless of the mouse strain background, going from <25 pg/ml in unstimulated cultures to roughly 40,000 pg/ml 40 h after exposure to anti-CD3. The ability of splenocytes from infected PE mice and F1 mice to respond to exogenous IFN-γ was measured in a CTL assay (Fig. 5). Splenocytes were harvested from animals 2 weeks postinoculation and cultured overnight with viral peptide in the presence or absence of added IFN-γ. Exogenous IFN-γ boosted CTL activity by PE and F1 splenocytes to levels approaching those observed in BR mice, which apparently respond maximally through their own production of IFN-γ.

FIG. 5.

Effect of exogenous IFN-γ on ex vivo CTL activity. The ex vivo CTL activity was determined as described for Fig. 3. The vertical bars represent the specific lysis induced by spleen cells of polyomavirus-infected mice at 2 weeks postinfection cultured in vitro in the presence (+) or absence (−) of exogenous IFN-γ (100 U/ml). The values are means of triplicate wells in each group.

Ex vivo production of cytokines by adherent spleen cells from infected mice.

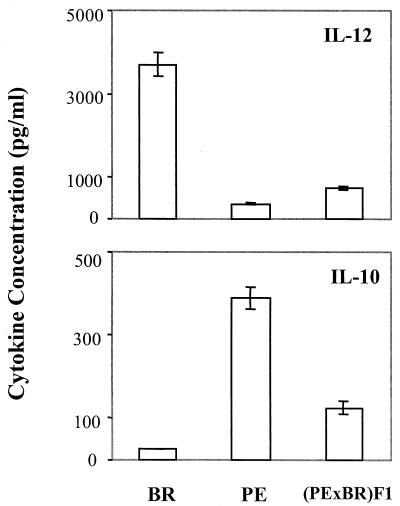

Resistant BR mice respond to polyomavirus by an IFN-γ-dominated type 1 cytokine response, while susceptible PE mice and F1 mice respond by an IL-10-dominated type 2 response. Polarization of these cytokine responses by T cells could be dictated by earlier events at the level of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). IL-12 production by APCs plays an essential role in stimulating NK cells and T cells to produce IFN-γ (7). To test the possibility that differential responses by APCs underlie tumor susceptibility versus resistance, plastic-adherent cells from BR mice, PE mice, and F1 mice were harvested 1 week after virus inoculation. Levels of IL-10 and IL-12 in the culture supernatants were measured after 36 h of cultivation without stimulation (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Ex vivo cytokine synthesis by spleens from acutely polyomavirus-infected mice. Plastic-adherent spleen cells from a pool of three polyomavirus-infected animals in each group were prepared at 1 week postinfection. The adherent cells were cultured for 36 h at 37°C in complete IMDM. The levels of cytokine in the culture supernatants were tested by double-sandwich ELISA. The vertical bars represent the means ± standard error for three experiments in each group. The concentrations in normal spleen cell cultures were less than 25 pg/ml.

Adherent cells from infected BR mice produced high levels of IL-12, while those from PE mice produced high levels of IL-10. Adherent cells from infected F1 mice appeared to contain subpopulations able to secrete either cytokine, although the levels of IL-12 produced were similar to those in PE mice. IL-4 was not detected in culture supernatants of adherent cells from any of the mouse strains used (data not shown). These results demonstrate a difference in the cytokine responses of APCs from virus-infected susceptible versus resistant mice and suggest that polarization of T-cell responses may arise from differences at the level of APCs.

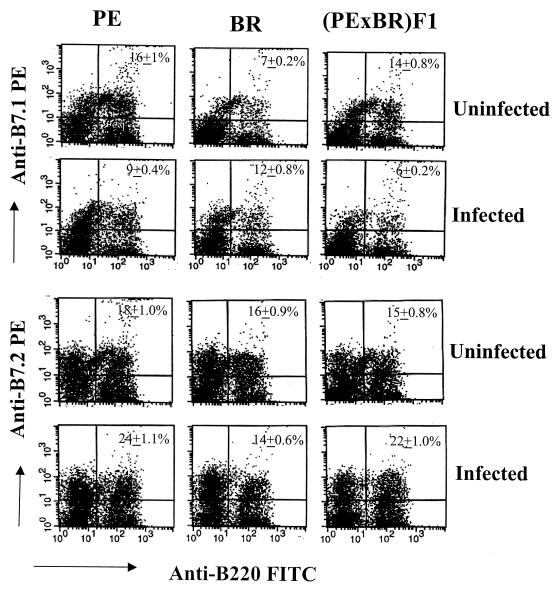

Expression of costimulatory molecules on APCs of infected mice.

Differential expression of costimulatory molecules on APCs leads to differential T-cell responses, with B7.1 favoring type 1 and B7.2 favoring type 2 responses (8). Polyomavirus infection might therefore be expected to lead to upregulation of B7.1 on APCs in BR mice and of B7.2 in PE mice. Spleen cells were harvested from infected mice 2 weeks after virus inoculation and stained for dendritic cells with anti-CD11c, for macrophages with anti-CD11b, and for B cells with anti-B220. Expression of B7.1 and B7.2 was measured separately in these three populations. Dendritic cells from infected BR mice responded by upregulation of B7.1, while those from infected PE mice responded by upregulation of B7.2 (Table 1). F1 animals responded similarly to PE mice, with decreased expression of B7.1 and increased expression of B7.2. B cells also responded in the same manner, with upregulation of B7.1 in BR mice and of B7.2 in PE and F1 mice (Fig. 7). Similar results were seen in the macrophage population (data not shown). These results further support the conclusion that polarization of responses to polyomavirus in resistant versus susceptible mice is determined at the level of APCs.

TABLE 1.

Differential expression of costimulatory molecules on splenic dendritic cells

| Mouse strain | Virus inoculationa | % Double-positive cellsb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| B7.1+ CD11c+ | B7.2+ CD11c+ | ||

| BR | − | 8.4 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.2 |

| + | 16.5 ± 1.0 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | |

| PE | − | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 11.6 ± 1.0 |

| + | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 16.5 ± 1.0 | |

| F1 | − | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| + | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | |

Newborn mice (<16 h old) were inoculated intraperitoneally with the PTA strain of polyomavirus.

Spleen cells were harvested at 2 weeks postinfection, stained with FITC-labeled anti-CD11c and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-B7.1 or -B7.2 antibodies, and analyzed by FACS. The percent double-positive cells was determined on a live-gated lymphocyte population. Numbers shown are the mean ± standard error for three animals in each group.

FIG. 7.

Levels of B7.1 and B7.2 costimulatory molecules in splenic B cells. Spleen cells from uninfected and polyomavirus-infected mice were harvested at 2 weeks postinfection and double stained with FITC-labeled anti-B220 and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-B7.1 or anti-B7.2 MAb. FACS events shown are the percentages of positive cells on the live-gated lymphocyte population. The values given in the upper right-hand corners are means ± standard error for double-positive cells from three animals in each group. The differences in percentages of positive cells in infected versus uninfected mice were significant (P < 0.05).

Administration of IL-12 to susceptible mice confers resistance to tumor development.

Production of IL-12 by APCs supports the activation, differentiation, and expression of effector functions of CTLs via IFN-γ (20). The failure of APCs from PE mice and F1 mice to produce IL-12 in response to polyomavirus may underlie their susceptibility to tumor induction by the virus. Administration of IL-12 to infected PE and F1 mice might therefore potentiate the antiviral CTL response and possibly result in a reduction in tumor frequency or delayed tumor growth.

Newborn PE mice and F1 mice were injected intraperitoneally with IL-12, followed 1 h later by virus (Table 2). Levels of Vβ6+ CD8+ virus-specific T cells were significantly elevated in infected PE mice and F1 mice treated with IL-12 compared to untreated controls. IL-12 treatment also led to a sharp increase in IFN-γ production by splenocytes from PE mice. Untreated F1 mice produced moderate amounts of IFN-γ, but the level was elevated three- to fourfold following IL-12 treatment. CTL activity was also elevated in PE and F1 mice treated with IL-12. T-cell functions in infected BR mice which express IL-12 endogenously were relatively unaffected by administration of IL-12. In parallel with rises in CTL functions, IL-12-treated, virus-infected PE mice and F1 mice also showed rises in APCs expressing B7.1 over B7.2. Among CD11c-positive cells, the percentage of B7.1-positive cells rose from 6.4% (without IL-12) to 12.5% (with IL-12) in PE mice and from 4.4% to 16.6% in F1 animals 2 weeks after IL-12 administration. The same animals showed decreases in B7.2-positive cells, from 16.5% to 11.7% in PE mice and from 9.6% to 4.8% in F1 animals. The APC profiles in BR mice, which respond to virus with IL-12 on their own, were not significantly altered by exogenous IL-12.

TABLE 2.

Effects of exogenous IL-12 on antiviral T-cell responsesa

| Mouse strain | Virus | IL-12 | % Dk/MT-389+ Vβ6+ CD8 T cells | IFN-γ (pg/ml) | CTL (% lysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BR | + | − | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 4,700 ± 240 | 42 |

| + | + | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 5,800 ± 270 | 44 | |

| PE | + | − | 3.5 ± 0.7 | < 25 | 14 |

| + | + | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 2,900 ± 170 | 30 | |

| F1 | + | − | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 1,200 ± 80 | 16 |

| + | + | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 4,200 ± 140 | 41 |

Newborn mice were given a single injection of recombinant IL-12 (0.5 μg/animal), followed 1 h later by virus inoculation. Control mice were injected with phosphate-buffered saline, followed by virus. The percentages of triple-positive T cells were enumerated by FACS with cells from spleens at 4 weeks postinfection. Values are given as the mean ± standard error for three animals in each group. Levels of IFN-γ in viral peptide-stimulated culture supernatants were measured by ELISA at 4 weeks postinfection. Values are given as the mean ± standard error for three animals in each group. CTL activities in spleen cells were tested by specific lysis at 3 weeks postinfection.

To test for an effect of IL-12 treatment on tumor development, PE mice and F1 mice were inoculated with IL-12 and virus as newborns and further treated with IL-12 on days 5 and 10 (Table 3). Tumors developed at a significantly reduced frequency and with a nearly twofold delay in the PE mice that were treated compared to untreated controls. In F1 mice, administration of the cytokine resulted in complete protection against tumor development. These results clearly demonstrate a protective effect of IL-12 and support the conclusion that tumor susceptibility in PE mice and their offspring results in large part from a failure of APCs to elaborate this important cytokine and to sustain an antiviral CTL response.

TABLE 3.

Effect of recombinant IL-12 on polyomavirus-induced tumor developmenta

| Strain | Treatment | No. of animals with tumor(s)/total no. infected | Avg age (range) at necropsy (days) | Tumor frequency index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | Control | 7/7 | 54 (51-71) | 5.4 |

| IL-12 | 14/14 | 91 (74-133) | 3.7 | |

| F1 | Control | 30/34 | 72 (52-161) | 2.0 |

| IL-12 | 0/22 | >330 | 0 |

Newborn mice were given three injections of recombinant IL-12 1 h prior to virus inoculation and again at 5 and 10 days postinfection. Control mice were virus infected and injected with phosphate-buffered saline in lieu of IL-12. The tumor frequency index is the average number of gross tumors per mouse at necropsy.

T-cell-independent antibody responses have been shown to control virus load in T-cell-deficient mice (18). To monitor antibody responses, hemagglutination inhibition titers were measured in the serum of infected mice. Titers were in the range of 1,250 to 1,750 at 3 weeks and rose to 4,500 to 5,120 at 5 weeks postinfection, with no differences noted between PE mice, BR mice, and F1 mice. Furthermore, the titers of antiviral antibody were unaffected by administration of IL-12. Protection against tumor development in PE mice and F1 mice treated with IL-12 thus appears to depend on enhanced CTL functions and not on humoral immunity.

DISCUSSION

The immunological basis of susceptibility to tumor induction by polyomavirus in PE mice has been identified. Susceptibility arises due to a type 2 cytokine response to the virus, resulting in the inability to mount a sustained CTL antitumor immune response. This form of susceptibility differs from that of classical inbred strains, which express a particular endogenous mouse mammary tumor virus superantigen that prevents tumor immunity by deletion of essential T-cell precursors (11). PE mice lack the endogenous superantigen and therefore possess the CD8+ Vβ6+ T cells which are required for protection against polyomavirus tumors in H-2k mice (22). Newborn PE mice inoculated with polyomavirus respond by a transient rise in CD8+ Vβ6+ virus-specific T cells but fail to sustain a CTL response.

BR mice resemble PE mice in major histocompatibility complex type and in being free of superantigen that targets Vβ6, yet they are highly resistant to polyomavirus tumor induction. The difference between these strains lies in the cytokine responses of their APCs to polyomavirus. APCs from BR mice respond with a type 1 response, producing predominantly IL-12 and leading to high levels of IFN-γ production. In contrast, APCs from infected PE mice secrete predominantly IL-10, and T cells from these mice produce no detectable IFN-γ. It is the absence of IFN-γ production that leads to the failure of PE mice to sustain CTL immunity, since addition of IFN-γ to cultures of T cells from infected PE mice restores CTL activity to levels comparable to those seen in infected BR mice.

The interpretation that the critical difference between PE mice and BR mice lies at the level of the innate immune response by APCs is supported by the results of administration of recombinant IL-12. Administration of this cytokine to newborn PE mice infected by the virus leads to restoration of CTL functions, a reduction in tumor frequency, and a significant delay in the appearance of tumors compared to untreated controls. Remarkably, infected F1 animals were completely protected from developing tumors by IL-12. Induction of a protective immune responses by IL-12 has been observed in a number of murine as well as human disease states (2, 9, 10, 15, 16, 19). These involve augmentation of CTL responses in both antiviral (2) and antitumor (2, 10, 16) immunity.

Susceptibility of PE mice is transmitted as a dominant or codominant (i.e., dosage dependent) trait in crosses with BR mice (22). This result is consistent with the observed cytokine response of F1 animals to polyomavirus infection. These animals show a transient type 1 response that rapidly becomes skewed toward type 2. Studies of tumor frequency in F1 × BR backcross mice previously indicated results consistent with a single dominant susceptibility gene in PE mice (22). However, the lack of complete penetration and the complexities of tumor development in this system leave open the possibility that multiple genes affect susceptibility. Attempts to map the genetic determinant(s), together with physiological and molecular studies of APCs and their interactions with virus, should lead to a better understanding of how polarization of cytokine responses is regulated in the parental strains and how the switch from type 1 to type 2 is controlled in F1 animals.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by grants R35 CA44343 and RO1 CA 90992 from the National Cancer Institute.

We duly acknowledge the kind gift of tetramers from Aron Lukacher, the help of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Tetramer Facility, and the services of Roderick Bronson and the Rodent Histopathology Core of the Dana-Farber Cancer Center (grant 2P30 CA 06516-37).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas, A. K., K. M. Murphy, and A. Sher. 1996. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature 383:787-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arulanandam, B. P., J. N. Mittler, W. T. Lee, M. O'Toole, and D. W. Metzger. 2000. Neonatal administration of IL-12 enhances the protective efficacy of antiviral vaccines. J. Immunol. 164:3698-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin, T. L. 2001. Polyomavirus: old findings and new challenges. Virology 289:167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll, J. P., J. S. Fung, R. T. Bronson, E. Razvi, and T. L. Benjamin. 1999. Radiation-resistant and radiation-sensitive forms of host resistance to polyomavirus. J. Virol. 73:1213-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey, D. C., R. T. Bronson, J. Dahl, J. P. Carroll, and T. L. Benjamin. 2000. Accelerated development of polyomavirus tumors and embryonic lethality: different effects of p53 loss on related mouse backgrounds. Cell Growth Differ. 11:231-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freund, R., C. J. Dawe, and T. L. Benjamin. 1988. Duplication of noncoding sequences in polyomavirus is required for the development of thymic tumors in mice. J. Virol. 62:3896-3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubin, M., M. Kamoun, and G. Trinchieri. 1994. Interleukin 12 synergizes with B7/CD28 interaction in inducing efficient proliferation and cytokine production of human T cells. J. Exp. Med. 180:211-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuchroo, V. K., M. P. Das, J. A. Brown, A. M. Ranger, S. S. Zamvil, R. A. Sobel, H. L. Weiner, N. Nabavi, and L. H. Glimcher. 1995. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell 80:707-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee, P., F. Wang, J. Kuniyoshi, V. Rubio, T. Stuges, S. Groshen, C. Gee, R. Lau, G. Jeffery, K. Margolin, V. Marty, and J. Weber. 2001. Effects of interleukin-12 on the immune response to a multiple vaccine for resected metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 19:3836-3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lui, V. W., Y. He, L. Falo, and L. Huang. 2002. Systemic administration of naked DNA encoding interleukin 12 for the treatment of human papillomavirus DNA-positive tumor. Hum. Gene Ther. 13:177-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukacher, A. E., Y. Ma, J. P. Carroll, S. R. Abromson-Leeman, J. C. Laning, M. E. Dorf, and T. L. Benjamin. 1995. Susceptibility to tumors induced by polyomavirus is conferred by an endogenous mouse mammary tumor virus superantigen. J. Exp. Med. 181:1683-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukacher, A. E., J. M. Moser, A. Hadley, and J. D. Altman. 1999. Visualization of polyomavirus-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo during infection and tumor rejection. J. Immunol. 163:3369-3379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukacher, A. E., and C. S. Wilson. 1998. Resistance to polyomavirus-induced tumors correlates with CTL recognition of an immunodominant H-2Dk-restricted epitope in the middle T protein. J. Immunol. 160:1724-1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser, J. M., and A. E. Lukacher. 2001. Immunity to polyomavirus infection and tumorigenesis. Viral Immunol. 14:199-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nanni, P., G. Nicoletti, C. De Giovanni, L. Landuzzi, E. Di Carlo, F. Cavallo, S. M. Pupa, I. Rossi, M. P. Colombo, C. Ricci, A. Astolfi, P. Musiani, G. Forni, and P. L. Lollini. 2001. Combined allogenic tumor cell vaccination and systemic interleukin 12 prevents mammary carcinogenesis in HER-2/neu transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 194:1195-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rook, A. H., M. H. Zaki, M. Wysocka, G. S. Wood, M. Duvic, L. C. Showe, F. Foss, M. Shapiro, T. M. Kuzel, E. A. Olsen, E. C. Vonderheid, R. Laliberte, and M. L. Sherman. 2001. The role for interleukin-12 therapy of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 941:177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schell, T. D., and S. S. Tevethia. 2001. Control of advanced choroid plexus tumors in SV40 T antigen transgenic mice following priming of donor CD8+ T lymphocytes by the endogenous tumor antigen. J. Immunol. 167:6947-6956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szomolanyi-Tsuda, E., and R. M. Welsh. 1996. T-cell-independent antibody-mediated clearance of polyomavirus in T-cell-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 183:403-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatsumi, T., T. Takehara, T. Kanto, T. Miyagi, N. Kuzushita, Y. Sugimoto, M. Jinushi, A. Kasahara, Y. Sasaki, M. Hori, and N. Hayashi. 2001. Administration of interleukin-12 enhances the therapeutic efficacy of dendritic cell-based tumor vaccines in mouse hepatocelluar carcinoma. Cancer Res. 61:7563-7577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trinchieri, G. 1993. Interleukin-12 and its role in the generation of TH1 cells. Immunol. Today 14:335-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velupillai, P., and D. A. Harn. 1994. Oligosaccharide-specific induction of interleukin 10 production by B220+ cells from schistosome-infected mice: a mechanism for regulation of CD4+ T-cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:18-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velupillai, P., I. Yoshizawa, D. C. Dey, S. R. Nahill, J. P. Carroll, R. T. Bronson, and T. L. Benjamin. 1999. Wild-derived inbred mice have a novel basis of susceptibility to polyomavirus-induced tumors. J. Virol. 73:10079-10085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsh, R. M. 2001. Assessing CD8 T-cell number and dysfunction in the presence of antigen. J. Exp. Med. 193:F19-F22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]