Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) sequences were detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in 8 of 13 HCV-positive patients. In four patients harboring different virus strains in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), CSF-derived virus was similar to that found in PBMC, which suggests that PBMC could carry HCV into the brain.

Patients with chronic hepatitis C are likely to have significant changes in their physical and mental well-being, most commonly manifested as fatigue and depression (5, 19), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) itself could affect cerebral function (4). Direct infection of the central nervous system (CNS) by HCV seems likely. HCV belongs to the family Flaviviridae, which includes well-known neurotropic viruses (e.g., yellow fever, dengue, and tick-borne encephalitis viruses), and in a recent study, we detected HCV RNA negative strand, which is a viral replicative intermediate, in brain tissue in HCV-infected patients (17). However, how HCV enters the CNS remains unclear. The present study was undertaken to determine whether circulating leukocytes could carry HCV into the CNS.

Thirteen patients who were anti-HCV positive and who underwent nontraumatic lumbar puncture for diagnostic purposes were studied. Clinical and laboratory data from these patients are presented in Table 1. Serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were collected on the same day and stored frozen at −80°C. RNAs were extracted from the whole CSF cell pellet or 5 × 106 to 1 × 107 PBMC by using a commercially available kit (Trizol; Gibco BRL) and were amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) as described previously (11).

TABLE 1.

Clinical and virological data for 13 patients for whom HCV RNA was analyzed in serum, PBMC, and CSF samples

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/ gendera | Clinical diagnosisb | Amt of serum HCV RNA (IU/ml)c | HIV-1 status/CD4+ count | CSF analysis

|

HCV RNA/genotyped

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cells/μl (% lymphocytes) | Amt of glucose (mg/dl) | Amt of protein (mg/dl) | Serum | PBMC | CSF supernatant | CSF cells | |||||

| 1 | 35/M | Aseptic meningitis, i.v. drug abuse | 1.32 × 104 | Positive/84 | 25 (99) | 29 | 240 | +/3a | +/1a | Negative | +/1ae |

| 2 | 25/M | Neurotoxoplasmosis, i.v. drug abuse | <600 | Positive/22 | 160 (100) | 25 | 160 | +/1a | +/4c | Negative | +/4c |

| 3 | 32/M | Neurotoxoplasmosis, i.v. drug abuse | 2.47 × 105 | Positive/5 | 23 (60) | 55 | 102 | +/1b | +/1b | Negative | +/1b |

| 4 | 24/M | Aseptic meningitis, i.v. drug abuse | 5.80 × 105 | Positive/370 | 28 (70) | 43 | 36 | +/1a | +/1a | +/1a | +/1ae |

| 5 | 33/M | Miliary tuberculosis | 1.08 × 106 | Positive/15 | 1 | 38 | 180 | +/1b | +/1b | Negative | Negative |

| 6 | 27/F | Neurotoxoplasmosis, i.v. drug abuse | <600 | Positive/85 | 4 (100) | 24 | 370 | +/1b | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 7 | 46/M | Aseptic meningitis | 5.74 × 105 | Negative | 150 (90) | 69 | 68 | +/1b | +/1b | +/1b | +/1b |

| 8 | 34/M | Aseptic meningitis | <600 | Negative | 53 (73) | 45 | 78 | +/1b | +/1b | Negative | +/1b |

| 9 | 64/M | Aseptic meningitis | 6.53 × 105 | Negative | 22 (89) | 52 | 54 | +/3a | +/3a | Negative | Negative |

| 10 | 21/M | Pneumonia, reactive meningitis, i.v. drug abuse | 1.06 × 106 | Positive/314 | 4 | 38 | 117 | +/1b | +/1be | Negative | +/1b |

| 11 | 28/F | Neurosyphilis, i.v. drug abuse | 6.30 × 105 | Positive/296 | 9 | 34 | 59 | +/4d | +/4d | Negative | Negative |

| 12 | 44/M | Multifocal leukoencephalopathy, i.v. drug abuse | 1.85 × 106 | Positive/46 | 3 | 62 | 52 | +/3a | +/3ae | Negative | +/3a |

| 13 | 27/M | Pulmonary tuberculosis, i.v. drug abuse | 3.04 × 105 | Positive/156 | 1 | 44 | 52 | +/4d | +/4d | Negative | Negative |

M, male; F, female

i.v., Intravenous.

HCV RNAs in sera were quantified with a commercial assay(Roche Amplicor Monitor assay, version 2.0).

The genotype was determined by sequencing of the 5′UTR. In all 13 sera and in all other samples from patients 1 to 3 and 12, the genotype was confirmed by sequencing of the NS5 region.

Presence of HCV RNA negative strand.

Strand-specific RT-PCR.

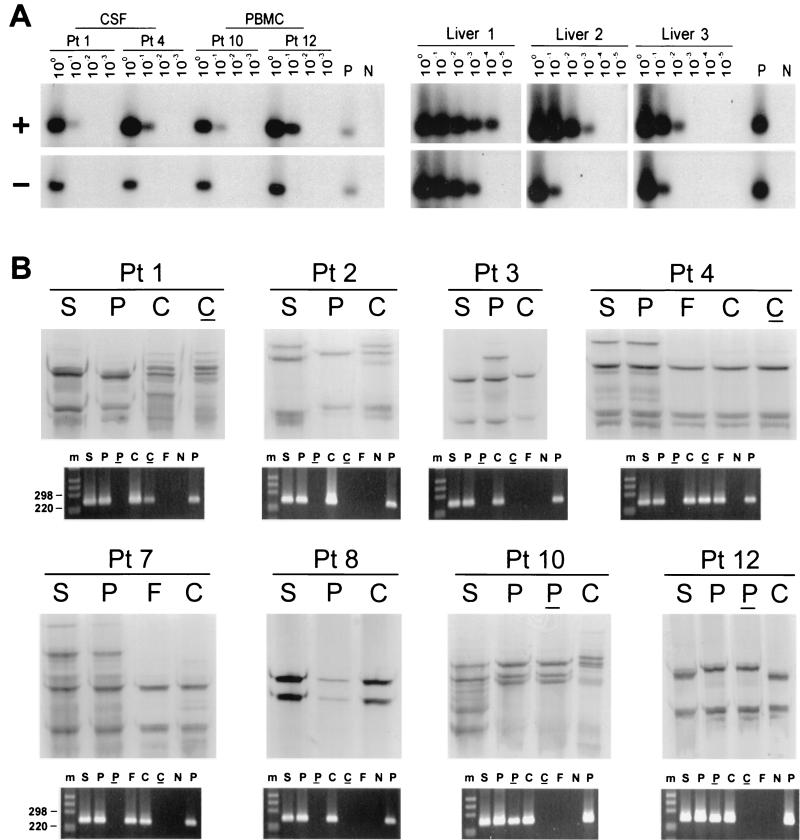

The strand specificity of our RT-PCR was ascertained by conducting cDNA synthesis at high temperature with the thermostable enzyme Tth. A detailed description of the assay was published previously (12). The assay was capable of detecting approximately 100 genomic eq molecules of the correct strand while unspecifically detecting ≥108 genomic eq of the incorrect strand. To determine its performance with samples containing replicating virus, we tested serial dilutions of RNA extracted from liver tissue samples from chronically infected patients. HCV RNA negative strand was detected in all three livers analyzed at a titer 1 to 2 logs lower than that of the positive strand (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Detection of HCV RNA positive strand (+) and negative strand (−) in CSF cells from patients (Pt) 1 and 4 and PBMC from patients 10 and 12, as well as in three liver tissue samples from HCV-infected patients. Tenfold serial dilutions of extracted RNA were tested for the presence of positive- and negative-strand HCV RNAs by Tth-based RT-PCR followed by Southern blotting and hybridization to a 32P-labeled probe. The amount of RNA loaded into the reaction mixture at dilution 100 corresponds to approximately 5 × 103 and 1 × 106 cells for CSF and PBMC samples, respectively. In the case of liver tissue samples, the first dilution corresponds to 1 μg of total RNA. Negative controls (lanes N) consisted of RNA extracted from PBMC and liver tissue from uninfected subjects, and positive controls (lanes P) consisted of 103 genomic eq of the correct synthetic strand mixed with 1 μg of RNA from an uninfected liver or RNA extracted from 106 PBMC. (B) Analysis by SSCP of 5′UTR HCV sequences amplified from serum (S), PBMC (P), and CSF from eight patients. Viral sequences were amplified from CSF cell pellets (C) for all patients and from CSF supernatant (F) for 2 patients. The RT-PCR products analyzed are also shown fractionated on NuSieve 2% agarose gels. Positive (P) and negative (N) controls consisted of RNA extracted from 106 PBMC from uninfected control subjects with and without the addition of 103 genomic eq of HCV RNA synthetic template. An underline represents the negative strand, and m represents the 1-kb molecular ladder (Gibco/BRL).

Analysis of HCV sequences.

The analysis was conducted with the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), because a small number of expected viral variants within quasispecies allows for reliable comparison, and we have previously found that variations in this region may correlate with extrahepatic replication (10, 11). Nested protocols were used to maximize the yield of PCR product, and HCV quasispecies were compared by the single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) assay as described elsewhere (11). The products analyzed were sequenced directly in both directions with a Perkin-Elmer ABI 377 automatic sequencer. The HCV genotypes were determined by sequencing the NS5b region (13).

HCV RNA was found in all sera and in 12 PBMC samples (Table 1). When CSF samples were analyzed, HCV RNA was detected in 8 of 13 cellular pellets and in 2 supernatants. The HCV RNA negative strand was not detected in any of the sera analyzed; however, it was detected in two PBMC samples and two CSF cell pellets. These reactions were unlikely to represent false-positive results, because nonspecific detection of the incorrect strand might be expected when the latter is present at a high number: at least 108 genomic eq/reaction. However, the concentration of HCV RNA in samples containing viral negative strand was no more than 103 genomic eq/reaction (Fig. 1A). Patients in whom HCV RNA could not be amplified from CSF were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Next, viral sequences amplified from CSF were compared by SSCP with respective viral sequences amplified from serum and PBMC. As seen in Fig. 1B, only in patient 8 were the band patterns of viral sequences amplified from serum, PBMC, and CSF identical. In patients 4 and 7, the serum patterns were identical to those of PBMC, while there were fewer CSF bands. However, the dominant SSCP bands were identical in all samples from each of these two patients.

In the remaining five patients (subjects 1 to 3, 10, and 12), viral sequences recovered from CSF were different from those derived from serum. Importantly, in patients 1, 2, 10, and 12, PBMC-derived HCV band patterns were also different from serum sequences.

Direct sequencing confirmed the presence of identical 5′UTR consensus sequences in serum, PBMC, and CSF in patients 4, 7, and 8. In patient 3, “master” sequences amplified from CSF differed by 1 nucleotide substitution from serum and PBMC sequences, but the difference was more substantial in the NS5 region (14 substitutions in the 226-nucleotide-length fragment [data not shown]). In patients 1 and 2, sequences recovered from CSF cells were classified as belonging to a different genotype from those found in serum. However, the latter were of the same genotype as sequences amplified from PBMC (Table 1). These differences in viral genotypes between serum, PBMC, and, CSF were confirmed by sequencing of the NS5b region.

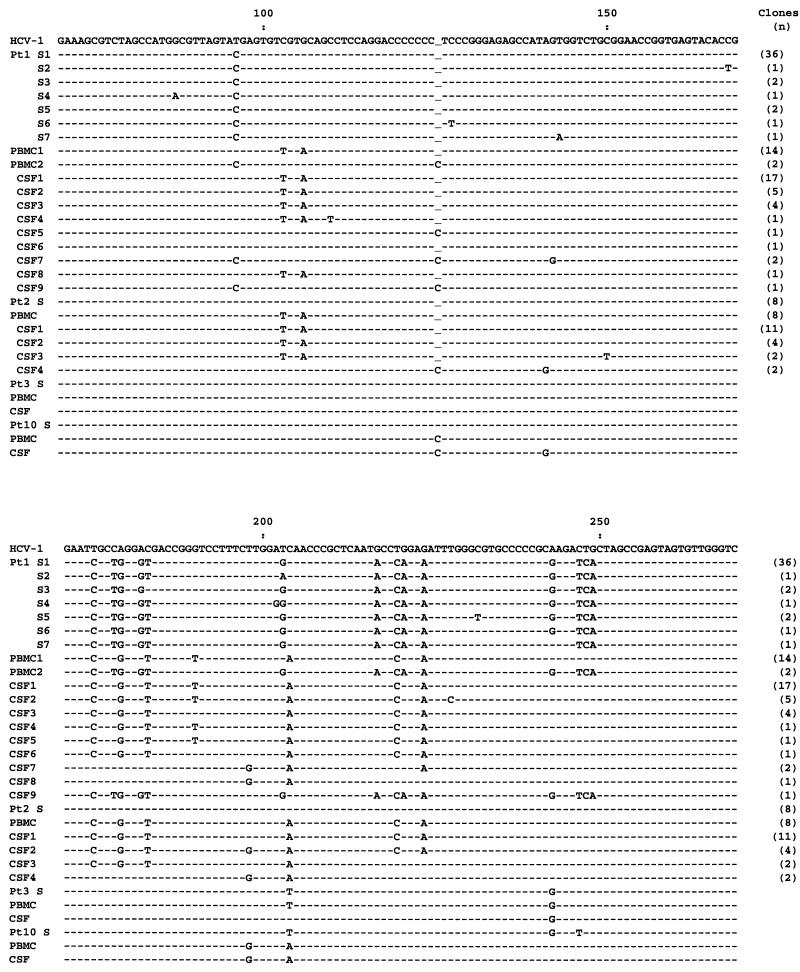

To better study the HCV sequences in patients 1 and 2, the respective amplicons were cloned (Invitrogen TA cloning system). All 44 clones derived from serum of patient 1 harbored closely related type 3a sequences (Fig. 2). However, 87 and 88% of clones derived from PBMC and CSF, respectively, harbored a different sequence, which was classified as type 1a. In patient 2, all serum-derived clones contained identical type 1a viral sequence, while PBMC- and CSF-derived clones harbored a number of closely related sequences that were different from those found in serum. These sequences were classified as belonging to genotype 4c (15).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence alignment of the 5′UTR fragment of HCV recovered from serum (S), PBMC, and cell pellet from CSF from patients (Pt) 1, 2, 3, and 10. In patients 1 and 2, the respective RT-PCR products were cloned, while in the other patients, RT-PCR products were sequenced directly. Sequences were compared with the prototype sequence published by Choo et al. (2) shown on the top line. Dashes show sequence identity, and underlines show gaps introduced to preserve sequence alignment.

In patient 12, direct sequencing of the 5′UTR revealed the presence of slightly different sequences in the serum, PBMC, and CSF compartments. Although these differences were too subtle to determine the origin of the virus present in CSF, analysis of the NS5 region was more conclusive, because PBMC- and CSF-derived sequences shared five unique substitutions compared to the serum virus (data not shown). Also in patient 10, 5′UTR sequences amplified from CSF seemed to be more closely related to the PBMC viral fraction than to the virus circulating in serum (Fig. 2).

All basic groups of leukocytes—T cells, B cells, macrophages/monocytes, and NK cells—have the ability to enter the brain under certain conditions (6). Certain monocyte family members are constantly being replaced as part of normal physiology (8, 20), while the entry of T cells and B cells appears dependent only on the activation state of the leukocyte and not on CNS factors (7, 9). Since HCV can replicate in leukocytes (1, 10, 11, 14, 18), it might be expected that these cells could carry the virus into the CNS. Our study supports this conjecture, because the presence of HCV RNA was found in the CSF cellular pellet in 8 of 13 patients studied. Moreover, HCV replicative forms were detected in two of these samples, providing direct evidence that the virus associated with CSF cells may be actively replicating and not just passively adsorbed. The lymphoid origin of HCV in CSF is supported by the findings that in four patients in whom PBMC- and serum-derived viral sequences were different, the HCV RNA found in CSF was closely related to the former, but dissimilar from the latter. Thus, HCV neuroinvasion could be related to trafficking of infected leukocytes through the blood-brain barrier, in a process similar to that postulated for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (16, 21). Subsequently, there could be a secondary spread of HCV to permissive cells within the brain. The most likely target would be the brain microglial cells, which are essentially tissue-resident macrophages of blood monocytic origin (3).

Interestingly, in patients 1, 2, 10, and 12, SSCP and sequencing analysis revealed that CSF-derived viral sequences contained a number of variants that were present neither in serum nor in PBMC. This suggests an independent viral evolution in the cells present in CSF and is an argument for the presence of an independent viral compartment in the CNS.

In summary, we documented the presence of HCV in CSF of infected patients. The virus was associated with CSF cells, and in patients harboring different viral strains in serum and PBMC, it was more closely related to PBMC- than serum-derived virus, which suggests that HCV-infected leukocytes carry the virus into the CNS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DA13760. M.R. was supported by grant 6PO5A01120 from the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bain, C., A. Fatmi, F. Zoulim, J. P. Zarski, C. Trepo, and G. Inchauspe. 2001. Impaired allostimulatory function of dendritic cells in chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology 120:512-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choo, Q. L., K. H. Richman, J. H. Han, K. Berger, C. Lee, C. Dong, C. Gallegos, D. Coit, R. Medina-Selby, P. J. Barr, A. J. Weiner, D. W. Bradley, G. Kuo, and M. Houghton. 1991. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2451-2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis, E. J., T. D. Foster, and W. E. Thomas. 1994. Cellular forms and functions of brain microglia. Brain Res. Bull. 34:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forton, D. M., J. M. Allsop, J. Main, G. R. Foster, H. C. Thomas, and S. D. Taylor-Robinson. 2001. Evidence for a cerebral effect of the hepatitis C virus. Lancet 358:38-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster, G. R. 1999. Hepatitis C virus infection: quality of life and side effects of treatment. J. Hepatol. 31:250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey, W. F. 1999. Leukocyte traffic in the central nervous system: the participants and their roles. Semin. Immunol. 11:125-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hickey, W. F., B. L. Hsu, and H. Kimura. 1991. T-lymphocyte entry into the central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res. 28:254-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickey, W. F., K. Vass, and H. Lassmann. 1992. Bone marrow-derived elements in the central nervous system: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural survey of rat chimeras. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 51:246-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knopf, P. M., C. J. Harling-Berg, H. F. Cserr, D. Basu, E. J. Sirulnick, S. C. Nolan, J. T. Park, G. Keir, E. J. Thompson, and W. F. Hickey. 1998. Antigen-dependent intrathecal antibody synthesis in the normal rat brain: tissue entry and local retention of antigen-specific B cells. J. Immunol. 161:692-701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, A. Piasek, M. Nowicki, A. Horban, J. Cianciara, and J. Rakela. 2000. Hepatitis C virus in lymphoid cells of patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence of active replication in monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 181:442-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, L. F. Wang, S. J. Jang, H. Vargas, and J. Rakela. 1998. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies in patients infected with HIV-1: correlation with extrahepatic viral replication. Virology 248:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, L.-F. Wang, H. Vargas, and J. Rakela. 1997. Lack of evidence for hepatitis G virus replication in the livers of patients coinfected with hepatitis C and G viruses. J. Virol. 71:7804-7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laskus, T., L.-F. Wang, M. Radkowski, H. Vargas, M. Nowicki, J. Wilkinson, and J. Rakela. 2001. Exposure of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA-positive recipients to HCV RNA-positive blood donors results in rapid predominance of a single donor strain and exclusion and/or suppression of the recipient strain. J. Virol. 75:2059-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerat, H., S. Rumin, F. Habersetzer, F. Berby, M. A. Trabaud, C. Trepo, and G. Inchauspe. 1998. In vivo tropism of hepatitis C virus genomic sequences in hematopoietic cells: influence of viral load, viral genotype, and cell phenotype. Blood 91:3841-3849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morice, Y., D. Roulot, V. Grando, J. Stirnemann, E. Gault, V. Jeantils, M. Bentata, B. Jarrousse, O. Lortholary, C. Pallier, and P. Deny. 2001. Phylogenetic analyses confirm the high prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) type 4 in the Seine-Saint-Denis district (France) and indicate seven different HCV-4 subtypes linked to two different epidemiological patterns. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1001-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price, R. W., J. Sidtis, and M. Rosenblum. 1988. The AIDS dementia complex: some current questions. Ann. Neurol. 23:S27-S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radkowski, M., J. Wilkinson, M. Nowicki, D. Adair, H. Vargas, C. Ingui, J. Rakela, and T. Laskus. 2002. Search for hepatitis C virus negative-strand RNA sequences and analysis of viral sequences in the central nervous system: evidence of replication. J. Virol. 76:600-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sansonno, D., A. R. Iacobelli, V. Cornacchiulo, G. Iodice, and F. Dammacco. 1996. Detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) proteins by immunofluorescence and HCV RNA genomic sequences by non-isotopic in situ hybridization in bone marrow and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronically HCV-infected patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 103:414-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh, N., T. Gayowski, M. M. Wagener, and I. R. Marino. 1999. Quality of life, functional status, and depression in male liver transplant recipients with recurrent viral hepatitis C. Transplantation 67:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unger, E. R., J. H. Sung, J. C. Manivel, M. L. Chenggis, B. R. Blazar, and W. Krivit. 1993. Male donor-derived cells in the brains of female sex-mismatched bone marrow transplant recipients: a Y-chromosome specific in situ hybridization study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 52:460-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng, J., and H. E. Gendelman. 1997. The HIV-1 associated dementia complex: a metabolic encephalopathy fueled by viral replication in mononuclear phagocytes. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 10:319-325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]