Abstract

Reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) from latency involves activation of the Zp promoter of the EBV BZLF1 gene. This occurs rapidly and efficiently in response to cross-linking the B-cell receptor on Akata Burkitt's lymphoma cells. After optimizing conditions for induction, signal transduction responses to B-cell receptor cross-linking were observed within 10 min, well before any autoactivation effects of BZLF1 protein. The primary events in reactivation were shown to involve dephosphorylation of the myocyte enhancer factor 2D (MEF-2D) transcription factor via the cyclosporin A-sensitive, calcium-mediated signaling pathway. This and other signal transduction events were correlated with the quantitative promoter analysis reported in the accompanying paper (U. K. Binné, W. Amon, and P. J. Farrell, this issue). Dephosphorylation of MEF-2D is known to be associated with histone acetylase recruitment, correlating with the histone acetylation at Zp during reactivation that we reported previously (Jenkins et al., J. Virol. 74:710-720, 2000). Histone deacetylation in response to phosphorylated MEF-2D can be mediated by class I or class II histone deacetylases (HDACs); HDAC 7 was the most readily detected class II HDAC in Akata and Raji cells, suggesting that it may be involved in Zp repression during latency.

Latency and reactivation are defining features of herpesviruses, and several common human diseases are caused by their reactivation. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is particularly favorable for the study of reactivation because efficient reactivation can be induced in some Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines in response to physiologically relevant stimuli such as B-cell receptor (BCR) stimulation (38, 39) and cytokine treatment (3, 12). The key step in reactivation of the lytic cycle is induction of the BZLF1 transcription factor through its promoter, Zp (4, 9). The mechanism of induction of Zp in response to cross-linking the BCR with anti-immunoglobulin (anti-Ig) is the subject of this study.

Initial studies of signaling to Zp were carried out with various signal transduction inhibitors to inhibit reactivation. Genistein (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) inhibited reactivation induced by BCR cross-linking (10), and a protein kinase C antagonist, staurosporine, completely blocked the appearance of BZLF1 after anti-Ig treatment (27). Treatment with the calcium ionophore A23187 increased Zp activity. When the calcium ionophore was used in conjunction with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate, a protein kinase C activator, Zp induction was synergistically enhanced. 1-(5-Isoquinolinylsulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine, an inhibitor of protein kinase C, inhibited the anti-Ig inducibility of Zp. Two calmodulin antagonists, compound R24571 and trifluoperazine, blocked Zp activation with anti-Ig. These findings suggested that Zp responds directly to changes in the activity of both protein kinase C and calcium- or calmodulin-dependent protein kinase.

A requirement for tyrosine kinase activation for anti-Ig-mediated Zp activation was also demonstrated through the use of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor herbimycin (11). Anti-IgG induced rapid phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in Akata cells. The phosphorylation was inhibited by the mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase-specific inhibitor PD98059. Expression of the EBV immediate-early BZLF1 mRNA and its protein product, ZEBRA, and early antigen was also prevented by the inhibitor. These results indicated that mitogen-activated protein kinase may be involved in the pathways of EBV activation (34).

In EBV-immortalized B-cell lines, the LMP1 and LMP2A proteins prevent reactivation of the lytic cycle (1, 28). The LMP1 mechanism is not yet known, but LMP2A protein prevents reactivation by interfering with BCR signaling. In EBV-infected cells in which LMP2A is expressed, cross-linking of secretory immunoglobulin fails to activate Lyn, Syk, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase C gamma 2, Vav, Shc, and mitogen-activated protein kinase. In contrast, cross-linking of secretory immunoglobulin on cells infected with EBV recombinants with null mutations in LMP2A resulted in transient tyrosine phosphorylation of Lyn, Syk, phospholipase C gamma 2, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, a transient increase in intracellular free calcium, and reactivation of lytic EBV infection. The block to surface immunoglobulin cross-linking-induced permissivity in cells expressing wild-type LMP2A could be bypassed by raising intracellular free calcium levels with an ionophore and by activating protein kinase C with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; all these components have been implicated in signaling to Zp (29, 30, 37).

Neither LMP1 nor LMP2A is significantly expressed in the Akata BL cell line which we have used to study EBV reactivation so reactivation can occur unimpeded by LMP proteins. Presumably the B cells from which EBV reactivates in vivo also do not express LMP1 or LMP2A, if antigen engagement of BCR is a physiological mechanism of reactivation. The memory B cells in which EBV persists in vivo and which are primed to respond to cognate antigen have been shown not to express the mRNAs for LMP1 and LMP2A (2), so it is logical that these might be cells from which this type of reactivation could occur.

Many molecular genetic analyses have resulted in identification of promoter elements within Zp that are involved in reactivation (21; reviewed in reference 36 and references contained therein). Previously published work involved use of disparate cell types and activation systems, many of which are of doubtful physiological relevance to the true control of EBV latency and reactivation. In the accompanying paper, we therefore determined the quantitative significance of Zp promoter elements in the response to cross-linking the BCR with anti-Ig with a system which accurately replicates the normal physiological control of Zp (5). This allows us to focus our biochemical studies of transcription factors that bind to Zp on those that bind to sequences which are quantitatively important in Zp regulation. The ZIA and -B sequences can bind the myocyte enhancer factor 2D (MEF-2D) transcription factor as well as Sp1 and Sp3 (6, 24, 25), the ZII sequence can bind AP-1, ATF, and CREB factors (16, 33, 41), and the ZIII sequences can bind BZLF1 (15, 40). Protein binding to the ZV sequence has been demonstrated (21), but the identity of the factor has not yet been described. For reference, proteins known to bind to Zp are shown diagrammatically in Fig. 5B.

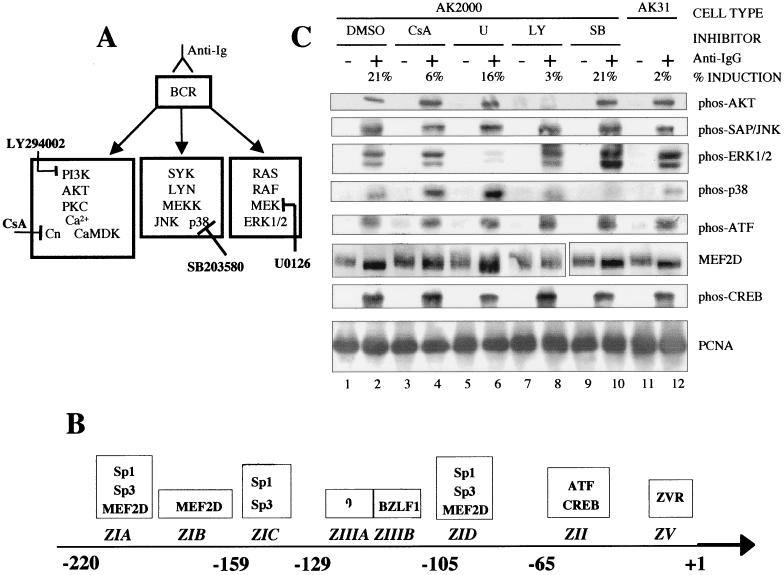

FIG. 5.

(A) Diagram of pathways activated upon BCR cross-linking and sites of action of inhibitors used. Cn, calcineurin, CaMDK, calmodulin-dependent kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKC, protein kinase C. (B) Diagram of Zp elements (not to scale) and proteins shown previously to bind to them. The numbers refer to the nucleic acid position relative to the transcription start site. (C) AK2000 cells were treated with various cell signaling inhibitors or, as a control, with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). They were then left (−) or induced with anti-IgG (+) for 10 min. A portion of the cells was removed, and protein extracts were made; the remainder of the cells were left at 37°C overnight. Aliquots of the protein extracts were assayed by Western blotting for the proteins indicated. Where phos precedes the protein name, the antibody was made against a phosphorylated form of the protein. AK31 cells were also induced and assayed along with the inhibitor-treated extracts. Percent induction corresponds to BZLF1-positive cells as determined by BZLF1-fluorescein isothiocyanate staining and flow cytometry analysis of the portion of cells left to induce overnight (Fig. 1B). CsA, cyclosporin A; U, U0126; LY, LY294002; SB, SB203580.

Only two previous studies have linked signaling to specific promoter elements. Transcriptional activation of a Zp reporter construct by CaMKIV/Gr was dependent on ZI and ZII elements and was greatly augmented by the Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (8, 25).

Previous studies have not detected modification of transcription factors that can regulate Zp or related any such changes to signal transduction pathways. Here, using the same cells for both investigations, we integrated biochemical studies with parallel molecular genetic analysis of the Zp promoter (5) and distinguished for the first time biochemical changes to transcription factors bound to Zp which occur rapidly after BCR stimulation. The changes are correlated with the signal transduction pathways involved and the reactivation of BZLF1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and induction of lytic replication.

The Akata and Jurkat cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated Serum Supreme (BioWhittaker). Induction of lytic replication was performed by treating exponentially growing cell cultures with 0.5% (vol/vol, final) rabbit anti-human IgG (Dako). For 2 days prior to induction, cells were split 1:2, and immediately prior to induction cells were resuspended at 106/ml in fresh medium. Where indicated, cells were treated with the inhibitors 4 μM cyclosporin A (Sigma), 10 μM U0126 (Cell Signaling Technology), 50 μM LY294002 (Cell Signaling Technology), and 5 μM SB203580 (Promega) for 1 h at 37°C and then induced as above in the presence of the inhibitor. Akata cells and the Akata clone we named AK2000 were kind gifts from K. Takada.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. (i) EBER RNA detection.

For analysis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, cells were fixed for 20 min at room temperature in 5% (vol/vol) acetic acid-4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and permeabilized for 10 min in 0.5% Tween 20 in PBS at room temperature. Hybridization with fluorescein peptide nucleic acid probes complementary to EBER RNA (Dako) (19) was done for 60 min at 56°C in 10% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate-10 mM NaCl-30% (vol/vol) formamide-0.1% (wt/vol) sodium pyrophosphate-0.2% (wt/vol) polyvinylpyrrolidone-0.2% (wt/vol) Ficoll-5 mM EDTA-50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5. After hybridization, cells were washed twice (10 and 30 min) with PBS containing 0.5% Tween at 56°C and resuspended in 0.5% Tween-PBS at room temperature.

(ii) BZLF1 detection.

Cells were fixed in methanol for 1 h at −20°C, rehydrated in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with BZ1 hybridoma supernatant for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times in PBS, cells were incubated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin-fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody (Dako) diluted 1:100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and finally washed three times in PBS and resuspended in PBS.

(iii) BCR detection.

Live cells were washed twice with ice-cold 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and then incubated for 1 h on ice in rabbit anti-human IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody (Dako) diluted 1:40 in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Cells were then washed three times in ice cold 0.1% bovine serum albumin-PBS and resuspended in PBS. The fluorescence signals were measured with a FACSort flow cytometer with the Cell Quest analysis program (Becton Dickinson). Total populations were gated to exclude doublets and cell debris.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Double-stranded oligonucleotides used were as follows: ZpIA/B, TGTCTATTTTTGACACCAGCTTATTTTAGAC; MIA/B, TGTGGATCCTTGACACCAGCGGATCCTAGAC; ZpIC, CCTCCTCTTTTAGAAACTAT; MIC, CCTCGGATCCTAGAAACTAT; ZpII, CCAAACCATGACATCACAGA; MII, CCAAACGAATTCATCACAGA; ZpIIIA, TGCATGAGCCACA; MIIIA, TGCAGAATTCACA; ZpIIIB, CAGGCATTGCTAATGTACCTCATAGACA; MIIIB, CAGGATCCGCTAATGTACCTCATAGACA; ZpV, ATGTTAGACAGGTAACTC; and MV, ATGTTAGACAGGCCACTC.

Oligonucleotides were end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase. To prepare nuclear extracts, cells were washed in PBS and then resuspended in buffer A (10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1% NP-40, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Boehringer Mannheim] and 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and II [Sigma]) and left on ice for 5 min. After brief centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the nuclei were suspended in buffer B (25% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl, 10 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and II) and mixed at 4°C for 15 min.

Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad DC protein assay. Aliquots were snap-frozen and stored at −70°C. Reactions were carried out as described by Borras et al. (6) except that 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and II was included in buffer D. When anti-BZLF1 antibody was used to supershift complexes, 5 μl of BZ1 hybridoma supernatant was added in the first incubation prior to the addition of labeled probe. Samples were electrophoresed on 4% polyacrylamide gels in 0.3× Tris-borate-EDTA and were detected with a phosphorimager.

Western blotting.

Extracts were prepared by diluting cells into ice-cold PBS, washing twice in ice-cold PBS, and resuspending (4 × 106 cells/100 μl) in a mixture containing ice-cold 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim), and 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and II (Sigma). Cells were then sonicated briefly on ice and centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. Aliquots of the supernatant were then snap-frozen and stored at −70°C. Proteins were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes.

After blocking for 1 h at room temperature with 5% milk powder made up in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), the membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies at the indicated dilutions in blocking solution. Phosphorylated protein-specific antibodies were diluted and blocked in 2% bovine serum albumin made up in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-0.1% Tween 20 (TBST). The antibodies used were anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473), anti-AKT, anti-phospho-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein (ERK1/2) kinase (Thr202/Tyr204), anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), anti-phospho-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (Thr180/Tyr182), anti-CREB, anti-phospho-CREB (Ser133) (also recognizes phospho-ATF), rabbit polyclonal antibodies used at 1:1,000 (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-MEF-2D (1:2,500) (Transduction Laboratories), sheep anti-ATF (1:500) (Upstate Biotechnology), anti-PCNA hybridoma supernatant (1:100), mouse anti-SP1 (1:500) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-SP3 (1:1,000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit anti-histone deacetylases (HDACs) 4 to 7 (1:200) (Cell Signaling Technology). After washing with PBST or TBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse Ig, goat anti-rabbit Ig, and rabbit anti-sheep Ig (Dako) all diluted 1:2,000 in 5% milk-PBST or 2% bovine serum albumin-TBST. After further washes, bound immunocomplexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Dephosphorylation.

To investigate the phosphorylation status of MEF-2D, extracts were prepared as above or without phosphatase inhibitors or without phosphatase inhibitors and with 5 U/100 μl of λ phosphatase (New England BioLabs) and incubated at 30°C for 5 min prior to loading on the gel.

RESULTS

In the accompanying paper (5), we have shown how Zp regulation can be reconstituted on plasmids stably maintained in an EBV-positive clone of the Akata cell line (AK2000 cells). The accurate quantitation of promoter activity provided by the luciferase reporter in those cells has brought a much greater precision to the analysis of promoter activity than was previously possible. To undertake biochemical analysis of the transcription factors and signal transduction pathways involved, we sought to optimize the induction conditions and investigate variables that might affect induction rate so that these could be controlled properly in the experiments.

Other EBV-positive Akata clones we have isolated have tended to lose their EBV progressively, but AK2000 seems relatively resistant to loss of its EBV in prolonged culture. Even after 1 year in culture, it retained episomal EBV (assessed by Gardella gel analysis; data not shown). A quantitative assay for EBV retention based on EBER RNA expression and flow cytometry was used to assess the proportion of cells that were EBV positive. Hybridization of a fluorescein isothiocyanate-peptide nucleic acid to the EBER RNA in the cells shown in Fig. 1A showed that about 90% of the AK2000 cells retained EBER expression and hence retained EBV. This was stable over a 1-year period of continuous passage in culture. EBV-negative clones AK31 and AK1 served as negative controls in these assays, and other EBV-positive clones used previously were found to range from only 26 to 41% EBER positive.

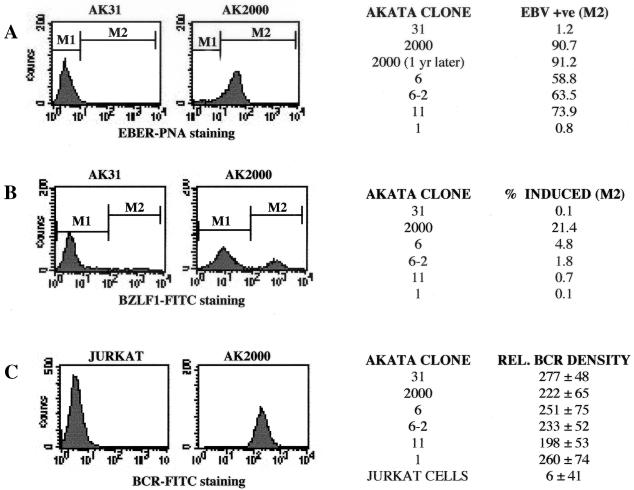

FIG. 1.

Six Akata clones were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe directed against EBER RNA (A), with anti-BZLF1 monoclonal antibody and then a secondary anti-mouse Ig-fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (B), and with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BCR antibody (C). The percentage of positive cells was determined with linear gates M1 set at 1% on unstained AK2000 cells and M2 corresponding to a fluorescence signal greater than this. The relative BCR density was the mean FL1 (fluorescence signal from fluorescein isothiocyanate) value. In each case, an example of staining is shown, followed by a table of values for other clones. The two AK2000 values in panel A represent results of EBER flow cytometry analysis taken before and after cells were passaged continuously for 1 year.

A quantitative flow cytometric assay was also developed for induction of the lytic cycle based on fluorescein isothiocyanate staining of BZLF1 protein in the cells. This showed that about 20% of the AK2000 cells were induced by anti-Ig under the conditions used for Fig. 1B. This contrasted with 1 to 5% of some other EBV-positive lines tested. The variation in induction between cell lines was not a consequence of different BCR expression on the lines (Fig. 1C). These quantitative assays allowed investigation of variables that might explain the variations and thus identify the most consistent conditions for induction of the lytic cycle by anti-Ig.

We tested whether cell density, serum concentration, or addition of fresh medium affected the degree of induction by anti-Ig (data not shown). The optimal conditions were a cell density of about 106/ml with the cells resuspended in new medium just before the addition of anti-Ig. Surprisingly, over the short time course of the experiments, it made little difference to the induction of BZLF1 whether serum was present or not during the anti-Ig treatment. The most useful procedure seemed to be resuspension in new medium immediately prior to anti-Ig treatment. We thus chose standard conditions for subsequent experiments of cells at about 106/ml resuspended in fresh medium with 10% fetal calf serum for treatment with anti-Ig.

The level of expression of LMP1 and LMP2A in AK2000 cells was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR analysis (data not shown). The levels of these RNAs were less than 1% of the levels present in an EBV-immortalized B-cell line transformed with Akata EBV. There was no measurable effect of the resuspension and anti-Ig treatment on this expression level and no significant variation in the LMP1 and LMP2A RNA from the Akata cells over a 6-month period in culture.

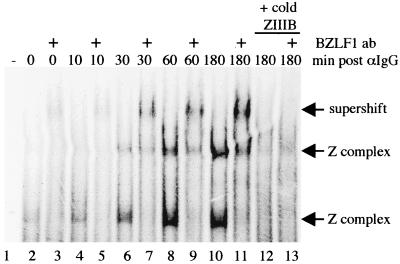

BZLF1 binds to Zp within 30 min of anti-Ig treatment.

Our objective was to identify signal transduction pathways and biochemical changes in transcription factors that mediate reactivation from latency. Autoactivation by BZLF1 is a very important secondary mechanism by which Zp is induced (15), but the key transition from latency to the reactivated state occurs prior to BZLF1 autoactivation. To define the time scale in which the primary events should be investigated, we therefore measured the time at which increased BZLF1 binding to the corresponding Zp promoter element began so that our studies could be conducted prior to that.

Cell extracts were prepared at various times after addition of anti-Ig to AK2000 cells and tested in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay for BZLF1 binding to the ZIIIB element (Fig. 2). The identity of the shifted band containing BZLF1 was confirmed by supershift with a monoclonal antibody to BZLF1. There is a low background of BZLF1 in the extracts because of a low degree of spontaneous activation of a few cells in the AK2000 cultures. This can be seen in the 0- and 10-min time points in Fig. 2. It is clear that the BZLF1 binding increases with time, the first detectable difference from the time zero value being at 30 min after addition of anti-Ig. There was no detectable difference between the 0- and 10-min time points, so we therefore restricted subsequent analysis of the primary induction events to 10 min after addition of anti-Ig.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay with an oligonucleotide spanning the ZIIIB region of Zp and nuclear extracts prepared over a time course after anti-IgG treatment. Complexes were shown to contain BZLF1 by supershifting with BZ1 anti-BZLF1 monoclonal antibodies (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13). Complexes were tested for specificity by competition with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled ZIIIB oligonucleotide (lanes 12 and 13). Specific complexes are marked by arrows. The uncomplexed probe was electrophoresed off the gel.

No changes in Zp binding detected 10 min after anti-Ig treatment.

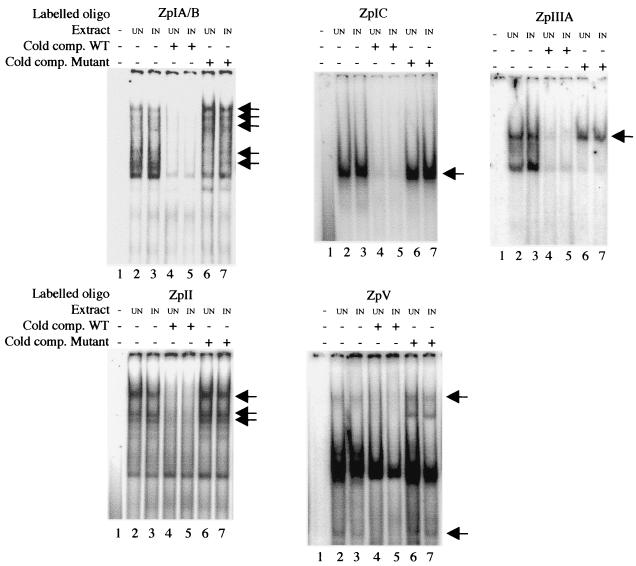

Earlier investigation of transcription factors binding to Zp sequences which used extracts of EBV-negative DG75 cells gave the first insight into factors that bind various elements of Zp (23-25). While mutation of the transcription factor binding sites has been shown to disrupt reactivation, changes in transcription factor binding have not been observed. The studies in the accompanying paper in AK2000 cells (5) and previous studies (21, 36) define some sequences that play a role in the reactivation, particularly the ZI, ZII, ZIIIA, and ZV elements that all affect the early stages of reactivation.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay experiments were conducted to compare protein binding to these elements by extracts of either AK2000 cells or the same cells treated for 10 min with anti-Ig. Various shifted bands were detected, but no differences were seen between the control and anti-Ig-treated electrophoretic mobility shift assay profiles (Fig. 3). Competition with matched or mismatched double-stranded oligonucleotides was used to distinguish specific from nonspecific complexes, but there were still no differences detectable in response to anti-Ig stimulation. It may be that signal transduction-dependent modifications to the relevant transcription factors do not alter DNA binding or the mobility of the complexes sufficiently to be detectable by this method.

FIG. 3.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay with oligonucleotides spanning regions of Zp (as indicated above each gel). Extracts used were from AK2000 cells untreated (UN) or treated with anti-IgG for 10 min (IN). Specificity of complexes was demonstrated by competition with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled wild-type (WT, lanes 4 and 5) or mutant oligonucleotide (lanes 6 and 7).

Factors binding Zp become modified rapidly upon BCR cross-linking.

Since we planned to seek biochemical changes only 10 min after addition of anti-Ig, we first tested whether known signal transduction events that result from BCR cross-linking (7) and illustrated in Fig. 5A were detectable in the AK2000 cells. A time course with phosphorylated protein-specific antibodies of the phosphorylation of AKT, p38, ERK1/2, and SAP/JNK kinase (Fig. 4), which are all known targets of BCR signal transduction, demonstrated the rapid appearance of the phosphorylated forms, peaking 5 to 15 min after addition of anti-Ig. PCNA was blotted as a control protein that did not change over the time course to demonstrate comparability of the cell extracts.

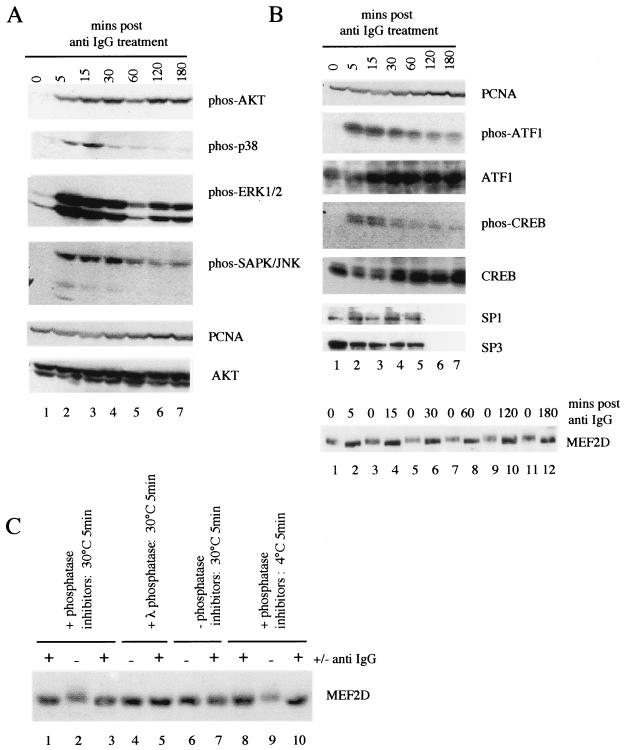

FIG. 4.

(A and B) Cells were treated with anti-IgG and extracts were prepared in a time course. Aliquots were assayed by Western blotting for the proteins indicated. Where phos precedes the protein name, the antibody was made against a phosphorylated form of the protein. (C) Cells were treated with anti-IgG or left untreated for 10 min, and then extracts were prepared. Aliquots were then incubated with or without phosphatase inhibitors or with 5 U of λ phosphatase for 5 min at the temperature indicated and assayed by Western blotting for MEF-2D.

The phospho-AKT was stable over a 3-h time course, but some of the modifications were very transient (Fig. 4A), emphasizing the importance of studying the reactivation mechanism for this herpesvirus in a highly defined system and within the correct time window. Studying factors binding to Zp 10 min after addition of anti-Ig appeared optimal for detection of changes relevant to the primary mechanism of reactivation. Since transcription factors which bind to the various sequence elements in Zp are known (Fig. 5B), we measured the expression and gel mobility of some of these factors 10 min after addition of anti-Ig.

It was clear (Fig. 4B) that phosphorylation of ATF1 and CREB occurred within 10 min of anti-Ig addition, but this phosphorylation was then rapidly reversed. There was also a small but characteristic and reproducible mobility shift in the MEF-2D protein; this modification remained for at least 180 min post-Ig treatment (Fig. 4B). After treatment with anti-Ig or extraction in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors or after λ phosphatase treatment, MEF-2D protein migrated more rapidly in the gel than protein from untreated extracts containing phosphatase inhibitors (Fig. 4C). This is consistent with dephosphorylation of MEF-2D upon BCR cross-linking. No modification of Sp1 or SP3 could be detected (Fig. 4B).

Correlation of reactivation, signaling events, and transcription factor modifications.

Three main signal transduction pathways which have been established from the BCR in response to cross-linking with anti-Ig (reviewed in reference 7) are illustrated in Fig. 5A. Specific chemical inhibitors of these pathways (cyclosporin A, LY294002, SB203580, and U0126) have been described, and the steps which they are thought to block are also shown in Fig. 5A. These inhibitors were tested for their ability to block the induction of the EBV lytic cycle (Fig. 5C). The solvent control dimethyl sulfoxide gave 21% induction and SB203580 showed no effect on induction of BZLF1-positive cells in this assay. Cyclosporin A and LY294002 both greatly reduced the activation from latency, but U0126 had only a modest effect.

The effects of the signal transduction inhibitors allowed a correlation between induction of the lytic cycle, the individual signal transduction pathways from the BCR, the transcription factor modifications, and the significance of the promoter sequences in the transcription assays shown in the accompanying paper (5) and previous studies. The objective was to identify the pathways which mediate reactivation. The effects of the inhibitors cyclosporin A, U0126, LY294002, and SB203580 on the signaling molecules shown in Fig. 5A verified that the inhibitors were functioning in these cells and displaying their proper specificities (Fig. 5C). Cyclosporin A had little effect on phosphorylation of AKT, SAP/JNK, MEK, or p38. U0126 greatly reduced the phosphorylation of MEK (and seemed to enhance phosphorylation of p38) but did not affect other signaling. LY294002 only prevented the phosphorylation of AKT, and SB203580 prevented the phosphorylation of p38 alone.

None of the inhibitors affected the phosphorylation of ATF1 as measured in this assay (Fig. 5B), but the mobility shift of MEF-2D in response to anti-Ig was prevented by cyclosporin A and LY294002. U0126 and SB203580 did not affect the MEF-2D mobility shift, indicating that the modification is a consequence of signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Ca2+ pathway (Fig. 5A). Cyclosporin A and LY294002 also inhibited reactivation.

The ZI elements which can bind MEF-2D are essential for the early steps in Zp reactivation (5), and cyclosporin A and LY294002 inhibit the MEF-2D modification and the induction of the lytic cycle. These experiments, in which efficiency of reactivation and timing of biochemical events have been carefully controlled, thus directly link the modification of MEF-2D via Ca2+ signaling to the primary reactivation process.

CREB has been shown to bind to the ZII element (36). ZII is shown in the accompanying paper to contribute to the early activation process but not to be essential for reactivation, since the MII mutant eventually catches up with the wild-type promoter once the BZLF1 autoactivation mechanism becomes active. U0126 modestly reduced CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 5B) and had a similar modest effect on induction of BZLF1-positive cells, consistent with phosphorylation of CREB via the Ras/ERK pathway mediating the CREB response through ZII.

HDAC 7 is the most readily detected class II HDAC in AK2000 cells.

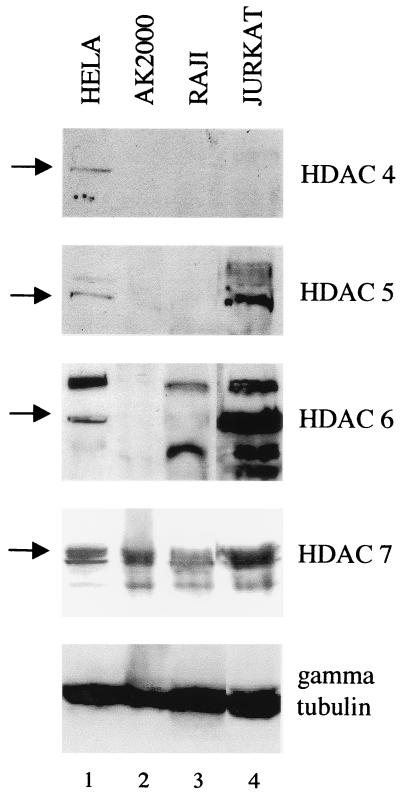

We have shown previously that histone acetylation is involved in reactivation and that the ZI elements which bind MEF-2D modulate this effect (18). MEF2 proteins are known to associate with HDACs, and a histone deacetylated state at Zp is found in latency (18). Association of HDACs with MEF-2D causes transcriptional repression (26, 31, 42, 43). The increase in histone acetylation at Zp during induction has been confirmed, and it was proposed that HDACs 4 and 5 are the HDACs which might mediate repression of Zp (17). Direct measurement of the expression of class II HDACs in Akata and Raji cells showed that HDACs 4 and 5 were undetectable but HDAC 7 was readily observed (Fig. 6). It thus seems unlikely that HDACs 4 and 5 mediate Zp repression in EBV latency. Our results imply that HDAC 7 would be the class II HDAC to be involved in repression of Zp in latency.

FIG. 6.

Total protein (50 μg) from four different cell lines was assayed by Western blotting for the indicated HDACs. The arrows mark the specific bands.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this work was to identify physiologically relevant mechanisms by which the reactivation of EBV from latency occurs. We have developed systems in which molecular genetic studies on Zp function can be linked to biochemical analysis by using the same cells for both types of assay. This will lead to a complete description of how latency is maintained and reactivation occurs. It was clear from the timing of increased BZLF1 binding to Zp that by 30 min autoactivation could have replaced the initial reactivation events. Previous studies have been focused too late after reactivation to observe the initial transient changes on Zp which are the key to reactivation. By studying events 10 min after anti-Ig stimulation, we detected, for the first time in these cells, modification of factors known to bind constitutively to Zp.

There have been many studies on the control of Zp during EBV reactivation, but we have brought together biochemical and molecular genetic analyses into the same system so that the results can be interpreted more rigorously. It is clear from the data shown here that signal transduction events from the BCR mediated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Ca2+ pathway result in modification of MEF-2D, which is able to bind to the ZI elements which are essential to reactivation. Calcium mobilization leads to activation of calcineurin, a calcium-dependent phosphatase, and to activation of calcium-dependent kinases such as CaMKIV/Gr. Previous data suggest that both are important for reactivation (8, 25). We found that MEF-2D is dephosphorylated in a cyclosporin A-sensitive manner upon BCR cross-linking, suggesting that calcineurin is involved in the modification, but our data do not exclude additional phosphorylation events. Dephosphorylated MEF-2D has been shown previously to be the transcriptionally active form of MEF-2D, while the phosphorylated form is transcriptionally inactive (13, 14, 22, 32). One study indicated that phosphorylated MEF-2D can be the active form (20).

We have shown previously that histone acetylation is involved in reactivation and that the ZI elements which bind MEF-2D mediate this effect (18). MEF2 proteins are known to associate with HDACs, causing transcriptional repression (26, 31, 42, 43). HDAC II molecules can interact directly with MEF2; when the HDAC binding domain of MEF2 has been phosphorylated by calmodulin-dependent kinase I or IV, the MEF2/HDAC II complex dissociates, allowing histone acetyltransferases to associate and MEF2 to become transcriptionally active (26). If class II HDACs mediate Zp repression during latency, our data suggest that HDAC 7 would be the most likely HDAC to be involved since it was the most readily detected class II HDAC in Akata and Raji cells.

MEF-2D can also be associated with class I HDACs via a corepressor Cabin1 and mSin3 complex (42, 43). Upon calcium ion influx, activated calmodulin binds to Cabin1, causing its dissociation from MEF-2D. In addition, activated calcineurin dephosphorylates NFAT, which then binds to MEF-2D. The MEF-2D and NFAT then synergize to bind the histone acetylase p300 (42, 43). Calcineurin remains associated with NFAT, maintaining dephosphorylation and therefore activation (35). Our data appear more compatible with calcineurin-mediated activation, since we observed net dephosphorylation of MEF-2D. The sustained dephosphorylation of MEF-2D would also be consistent with the calcineurin-NFAT mechanism.

U0126 modestly reduced CREB phosphorylation and had a similar modest effect on induction of BZLF1-positive cells, consistent with phosphorylation of CREB via the Ras/ERK pathway mediating the CREB response through ZII. None of the other inhibitors affected CREB phosphorylation, but it is likely that other pathways not studied (e.g., phosphorylation by calcium-dependent kinases) also contribute to CREB phosphorylation and activation (8). ZII was required for the rapid early induction of Zp; in the presence of BZLF1, the MII promoter eventually caught up with the wild-type Zp (5, 15). There may be a relationship between the transient nature of the CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 4B) and the transient delay in promoter activation, but this will require further investigation. The effects of the inhibitors on BZLF1 expression were assayed 16 h after anti-Ig addition (Fig. 5), so it is possible that a transient inhibition by U0126 was underestimated, allowing the possibility that this arm of the BCR signaling pathway participates in Zp reactivation.

The promoter mutation analysis showed that the ZIIIA and ZV elements also greatly affect reactivation of Zp (5, 11, 15, 16, 21). ZIIIA has been primarily studied as a BZLF1 binding site, but ZIIIA has an essential role in early activation (5). ZIIIA is similar to an AP-1 site, but the precise sequence of ZIIIA has been tested previously in a study of the binding specificity of c-Jun and shown not to bind (40). The identity of the factor that mediates the primary induction effects through ZIIIA has thus yet to be determined. The ZV element binds a repressor of reactivation (21), but the identity of this factor has also not yet been determined. Further understanding of these promoter elements and the signaling to them will depend on identification of the factors that bind to them

In summary, biochemical modification of transcription factors has been linked directly to genetic analysis of sequences involved in Zp reactivation, and a coherent biochemical explanation for reactivation of EBV has emerged. Latency and reactivation are key features of herpesvirus biology. Different herpesviruses characteristically become latent in different cell types, and their reactivation will have evolved to depend on transcription factors that relate to those cell types. However, the basic principle of repressive chromatin structure in latency that is overcome during reactivation may prove to be a paradigm for this group of viruses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, B., E. Schaadt, B. Kempkes, U. Zimber-Strobl, B. Baier, and G. W. Bornkamm. 2002. Control of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation by activated CD40 and viral latent membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:437-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G. J., D. Hochberg, and A. D. Thorley-Lawson. 2000. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity 13:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, G., P. Hofler, and M. Simon. 1982. Epstein-Barr virus induction by a serum factor. Characterization of the purified factor and the mechanism of its activation. J. Biol. Chem. 257:11411-11415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biggin, M., P. J. Farrell, and B. G. Barrell. 1984. Transcription and DNA sequence of the BamHI L fragment of B95-8 Epstein-Barr virus. EMBO J. 3:1083-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binné, U. K., W. Amon, and P. J. Farrell. 2002. Promoter sequences required for reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 76:10282-10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Borras, A. M., J. L. Strominger, and S. H. Speck. 1996. Characterization of the ZI domains in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 gene promoter: role in phorbol ester induction. J. Virol. 70:3894-3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, K. S. 1999. Signal transduction from the B cell antigen-receptor. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:256-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatila, T., N. Ho, P. Liu, S. Liu, G. Mosialos, E. Kieff, and S. H. Speck. 1997. The Epstein-Barr virus-induced Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase type IV/Gr promotes a Ca2+-dependent switch from latency to viral replication. J. Virol. 71:6560-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Countryman, J., and G. Miller. 1985. Activation of expression of latent Epstein-Barr herpesvirus after gene transfer with a small cloned subfragment of heterogeneous viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:4085-4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daibata, M., I. Mellinghoff, S. Takagi, R. E. Humphreys, and T. Sairenji. 1991. Effect of genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, on latent EBV activation induced by cross-linkage of membrane IgG in Akata B cells. J. Immunol. 147:292-297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daibata, M., S. H. Speck, C. Mulder, and T. Sairenji. 1994. Regulation of the BZLF1 promoter of Epstein-Barr virus by second messengers in anti-immunoglobulin-treated B cells. Virology 198:446-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.di Renzo, L., A. Altiok, G. Klein, and E. Klein. 1994. Endogenous TGF-beta contributes to the induction of the EBV lytic cycle in two Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Int. J. Cancer. 57:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn, S. E., E. R. Chin, and R. N. Michel. 2000. Matching of calcineurin activity to upstream effectors is critical for skeletal muscle fiber growth. J. Cell Biol. 151:663-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn, S. E., A. R. Simard, R. Bassel-Duby, R. S. Williams, and R. N. Michel. 2001. Nerve activity-dependent modulation of calcineurin signaling in adult fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45243-45254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Autoregulation of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J. Virol. 64:1227-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Identification of phorbol ester response elements in the promoter of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J. Virol. 64:1217-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruffat, H., E. Manet, and A. Sergeant. 2002. MEF2-mediated recruitment of class II HDAC at the EBV immediate early gene BZLF1 links latency and chromatin remodeling. EMBO Rep. 3:141-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins, P., U. Binné, and P. Farrell. 2000. Histone acetylation and reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 74:710-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Just, T., H. Burgwald, and M. K. Broe. 1998. Flow cytometric detection of EBV (EBER snRNA) with peptide nucleic acid probes. J. Virol. Methods 73:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato, Y., M. Zhao, A. Morikawa, T. Sugiyama, D. Chakravortty, N. Koide, T. Yoshida, R. I. Tapping, Y. Yang, T. Yokochi, and J. D. Lee. 2000. Big mitogen-activated kinase regulates multiple members of the MEF2 protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18534-18540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraus, R. J., S. J. Mirocha, H. M. Stephany, J. R. Puchalski, and J. E. Mertz. 2001. Identification of a novel element involved in regulation of the lytic switch BZLF1 gene promoter of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 75:867-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, M., D. A. Linseman, M. P. Allen, M. K. Meintzer, X. Wang, T. Laessig, M. E. Wierman, and K. A. Heidenreich. 2001. Myocyte enhancer factor 2A and 2D undergo phosphorylation and caspase-mediated degradation during apoptosis of rat cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurosci. 21:6544-6552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, P., S. Liu, and S. Speck. 1998. Identification of a negative cis element within the ZII domain of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch BZLF1 gene. J. Virol. 72:8230-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, S., A. M. Borras, P. Liu, G. Suske, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Binding of the ubiquitous cellular transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 to the ZI domains in the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch BZLF1 gene promoter. Virology 228:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, S., P. Liu, A. Borras, T. Chatila, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Cyclosporin A-sensitive induction of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch is mediated via a novel pathway involving a MEF2 family member. EMBO J. 16:143-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu, J., T. A. McKinsey, R. L. Nicol, and E. N. Olson. 2000. Signal-dependent activation of the MEF2 transcription factor by dissociation from histone deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4070-4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellinghoff, I., M. Daibata, R. E. Humphreys, C. Mulder, K. Takada, and T. Sairenji. 1991. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus genome expression after activation: regulation by second messengers of B cell activation. Virology 185:922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, C. L., J. H. Lee, E. Kieff, and R. Longnecker. 1994. An integral membrane protein (LMP2) blocks reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency following surface immunoglobulin crosslinking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:772-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, W. E., H. S. Earp, and N. Raab-Traub. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Virol. 69:4390-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, W. E., R. H. Edwards, D. M. Walling, and N. Raab-Traub. 1994. Sequence variation in the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2729-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miska, E. A., C. Karlsson, E. Langley, S. J. Nielsen, J. Pines, and T. Kouzarides. 1999. HDAC4 deacetylase associates with and represses the MEF2 transcription factor. EMBO J. 18:5099-5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ornatsky, O. I., and J. C. McDermott. 1996. MEF2 protein expression, DNA binding specificity and complex composition, and transcriptional activity in muscle and non-muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24927-24933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruf, I. K., and D. R. Rawlins. 1995. Identification and characterization of ZIIBC, a complex formed by cellular factors and the ZII site of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J. Virol. 69:7648-7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satoh, T., Y. Hoshikawa, Y. Satoh, T. Kurata, and T. Sairenji. 1999. The interaction of mitogen-activated protein kinases to Epstein-Barr virus activation in Akata cells. Virus Genes 18:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibasaki, F., E. R. Price, D. Milan, and F. McKeon. 1996. Role of kinases and the phosphatase calcineurin in the nuclear shuttling of transcription factor NF-AT4. Nature 382:370-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speck, S., T. Chatila, and E. Flemington. 1997. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus: regulation and function of the BZLF1 gene. Trends Microbiol. 5:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swart, R., I. K. Ruf, J. Sample, and R. Longnecker. 2000. Latent membrane protein 2A-mediated effects on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J. Virol. 74:10838-10845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takada, K. 1984. Cross-linking of cell surface immunoglobulins induces Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Int. J. Cancer. 33:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takada, K., and Y. Ono. 1989. Synchronous and sequential activation of latently infected Epstein-Barr virus genomes. J. Virol. 63:445-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor, N., E. Flemington, J. L. Kolman, R. P. Baumann, S. H. Speck, and G. Miller. 1991. ZEBRA and a Fos-GCN4 chimeric protein differ in their DNA-binding specificities for sites in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J. Virol. 65:4033-4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, Y. C., J. M. Huang, and E. A. Montalvo. 1997. Characterization of proteins binding to the ZII element in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter: transactivation by ATF1. Virology 227:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Youn, H. D., T. A. Chatila, and J. O. Liu. 2000. Integration of calcineurin and MEF2 signals by the coactivator p300 during T-cell apoptosis. EMBO J. 19:4323-4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Youn, H. D., and J. O. Liu. 2000. Cabin1 represses MEF2-dependent Nur77 expression and T cell apoptosis by controlling association of histone deacetylases and acetylases with MEF2. Immunity 13:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]