Abstract

A luciferase reporter system with stably transfected oriP plasmids in Akata Burkitt's lymphoma cells provides a quantitative assay for the BZLF1 Zp promoter in response to B-cell receptor (BCR) activation by cross-linking with anti-immunoglobulin. In this system, detailed kinetic studies of promoter activity are possible. Previously reported promoter elements upstream of −221 from the transcription start and the ZIIR sequence had little effect on the Zp promoter, but the ZI and ZIIIA elements were essential for early activation. The ZIIIB element mediates autoactivation. Mutation of the ZV repressor sequence greatly increased the induction of the promoter but did not make it constitutively active. Zp transcription in response to BCR cross-linking declined after a few hours; this decline was reduced and delayed by acyclovir or phosphonoacetic acid, indicating that viral DNA replication or a late viral gene can play a role in the switch off of the Zp promoter. Late expression of the LMP1 protein may account for this.

Herpesviruses characteristically display latent persistence in their hosts and intermittent reactivation of replication. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) persists benignly in the great majority of the world's population but is also found in a latent state in the tumor cells of several types of human cancer, including Burkitt's lymphoma (15). Understanding the mechanisms by which latency of herpesviruses is determined requires cell culture systems which mimic in vivo latent persistence. Among the human herpesviruses, EBV is favorable for this because cell lines with latent (nonproductive) infections are readily available. Viral reactivation is induced in Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines by agents which are plausible physiological inducers of virus replication, namely, engagement of the B-cell receptor (BCR) (31, 32) and the cytokine transforming growth factor beta (2, 6, 7, 12). We have studied the efficient reactivation of the EBV lytic cycle induced by cross-linking surface immunoglobulin on Akata Burkitt's lymphoma cells so as to mimic the binding of antigen to the BCR and characterized many aspects of the induction process (14, 24, 29).

Previous experiments showed that Zp regulation and BZLF1 expression could be reconstituted in an EBV-negative cell line (Akata) when an episomal vector carrying Zp, BZLF1, oriP, and EBNA1 was stably transfected (14). BZLF1 protein levels and activation kinetics from the transfected plasmids after induction were similar to those from the endogenous viral genome of EBV-positive Akata cells. Several mechanisms for silencing of the Zp promoter were evaluated, such as antisense RNA, downregulation of BZLF1 by a viral product, and methylation of Zp. However, none of these mechanisms was found to play an essential role in Zp silencing. Instead, a mechanism was proposed which involves changes in the state of histone acetylation of chromatin containing Zp during reactivation. Zp chromatin changes from a hypo- to a hyperacetylated state to allow transcription from this promoter upon reactivation (14).

Our data on changes in histone acetylation during reactivation in Akata cells have recently been confirmed (10), and it has additionally been shown that modified versions of histone deacetylases 4 and 5 are able to associate with a transcription factor that binds to Zp. It was thus suggested (10) that those histone deacetylases could have a role in establishing or maintaining the hypoacetylated, inactive chromatin at Zp. Transcription factors which bind Zp and the autoactivation of Zp by BZLF1 have been reviewed extensively (30).

Our long-term objective in this work is to describe the molecular mechanism by which the inactivity of the Zp promoter is maintained in latency and how reactivation of the promoter is induced in response to physiologically relevant induction of the lytic cycle. Here we describe a quantitative system for measuring Zp activity in Akata cells and use it to measure the effects of transcription factor binding sites in Zp on the kinetics of promoter activation. Compared to the data obtained with this system, previously published work on the control of Zp is either nonquantitative or used mechanisms of reactivating the lytic cycle of doubtful physiological relevance. The results clarify our earlier studies, identify elements in the promoter that are important for induction, and reveal a new aspect to the termination of Zp activity after reactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and mutagenesis of Zp.

The luciferase reporter gene was excised from pGL2 (Promega) and cloned downstream of the wild-type Zp −552 promoter from plasmid p294:Zp-552Xwt (14), both being inserted between the BamHI and SalI sites of pHEBo (34) to create pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc. A corresponding negative control vector without the Zp promoter, pHEBo-luc, was created.

The published mutations in the Zp elements to give MIA, MIB, MIC, MII, MIIR, MIIIA, MIIIB, and MV (17, 18, 30) were introduced either by transferring the corresponding Zp fragments from the equivalent p294:Zp-552 plasmid (14) or by site-directed mutagenesis. The plasmid p294:Zp-MV-BZLF1 was made by transferring the Zp promoter from the pHEBo-MV-luc into p294:Zp-552Xwt. The nucleotides altered in these Zp modifications are summarized in the oligonucleotide list in reference 3.

Transfection and luciferase assays.

Plasmids were electroporated into Akata cells as described previously (14). Induction with anti-immunoglobulin (anti-Ig) was performed with a goat anti-human IgG antibody (Sigma) at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. For luciferase assays, cells were collected by centrifugation, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and then lysed in 100 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 min at room temperature. Debris was removed by centrifugation for 2 min in the microcentrifuge. A 20-μl sample of supernatant was assayed for 10 s on a Berthold Autolumat luminometer.

Cell line characterization and luciferase data treatment.

For Southern blot analysis, 2 μg of DNA from cell lines was digested with EcoRI and electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels. After blotting to nitrocellulose, the filters were probed with pGL2 DNA (Promega) labeled by random priming. The blot was analyzed with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics) on the phosphorimager. The fraction of cells that were induced in response to anti-Ig was estimated by flow cytometry, staining the cells with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled BZ1 antibody to BZLF1 (3). Luciferase data from different cell lines and experiments were then related by normalizing the relative light units to the plasmid copy number from the Southern blot, the protein concentration of the extract determined by the Bradford assay, and the induction fraction data for each experiment.

Protein expression was assayed by Western blotting on nitrocellulose filters. Antibodies used were BZ1 hybridoma supernatant diluted 1:100, BdRF1 p40 (33) diluted 1:1,000, and LMP1 S12 antibody (20), followed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham).

RESULTS

Reporter system to analyze Zp regulation in the presence of the complete EBV genome.

Previous studies (14) used BZLF1 protein expression as a readout for Zp activity and were conducted in cells lacking EBV. Although the regulation of Zp appeared to be reconstituted correctly, one could be more certain that all regulatory systems are in place if the assay were performed in EBV-positive cells. Also, more quantitative measurement of gene expression from Zp was required, and for such accuracy, the method needs to take account of various copy numbers of transfected plasmids in the EBV-positive background and variations in the frequency of induction of the cells by anti-Ig. A system was thus devised in which the BZLF1 coding sequence was replaced with the reporter gene luciferase.

Since further experiments would be undertaken in an EBV-positive background, where EBNA1 is expressed constitutively from the EBV, the EBNA1 gene was omitted from the new plasmid, pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc (Fig. 1A). Also, for all subsequent experiments, EBV-positive Akata 2000 cells were used. AK2000 is an Akata cell clone (a kind gift from Kenzo Takada) that is similar to the previously used AK6 line (14) but with better anti-IgG inducibility and more stable retention of EBV (3). Stable cell lines carrying pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc or the empty vector control pHEBo-luc were isolated.

FIG. 1.

(A) Linearized representation of the pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc plasmid, which contains a luciferase reporter gene and the Zp promoter region from +12 to −552 relative to the transcription start site. Other elements shown are oriP and the genes for hygromycin (Hyg) and ampicillin (Amp) resistance. (B) Luciferase assay of AK2000/pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc cells treated with anti-Ig. A total of 5 × 106 cells per sample were treated with anti-IgG and harvested at various times postinduction (p.i.) as indicated. Cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity, shown in relative light units (RLU). (C) Western blot of cells analyzed in panel B for BZLF1 with PCNA (proliferating nuclear antigen) as a loading control. Co, control pHEBo-luc.

Figure 1B shows a representative luciferase assay, and Fig. 1C is the accompanying Western blot from the same samples for a time course of anti-IgG-induced AK2000/pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc cells. This experiment was repeated three times with similar results. Cells with similar plasmid copy numbers for pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc and pHEBo-luc were chosen, as measured by Southern blotting, and the frequency of BZLF1 induction of the clones was determined to be 13.5% ± 0.3% by cell sorting (data not shown) for both of the clones illustrated here.

The results in Fig. 1B and C indicate that the activity of the transfected Zp promoter measured by luciferase closely reflects the induction of BZLF1 protein from the EBV genome in the cells measured by Western blotting. Luciferase activity from the wild-type plasmid rose rapidly soon after addition of anti-Ig, and maximum levels were present at around 12 h postinduction. In the later phase, luciferase activity decreased slowly, reaching about half of the maximum after 48 h. In the Western blot, BZLF1 protein was readily detectable at 4 h after induction, the level peaked at around 12 h and decreased steadily thereafter. It seems clear from this time course that measuring Zp-directed protein expression or reporter gene expression 24 or 48 h after induction, as has been done in most of the published literature on this topic, is a very uncertain measurement of the true promoter activity. The luciferase reporter system will allow dissection of more subtle kinetic effects in the early activation of the Zp promoter.

Quantitative analysis of promoter elements in Zp.

Regulatory elements in the Zp promoter are divided into three groups, summarized in Fig. 2A. The positive elements (ZI, ZII, and ZIIIA) (9, 28) and negative elements (H1, ZIIR, ZIV, and ZV) (17, 18, 22, 23, 27) have been reported to respond to cell signaling and to bind to cellular transcription factors. The positive elements are believed to initiate Zp transcription. The third category is the autoactivation elements (ZIIIA and B), which can positively regulate the Zp promoter (8), binding the viral protein BZLF1 made during the initial activation phase.

FIG. 2.

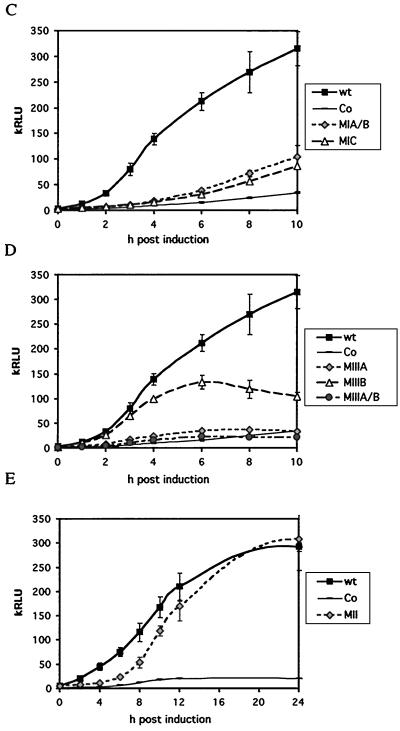

(A) Relative positions of published elements in the Zp promoter. (B) Example of Southern blot of Zp mutants to determine the copy number of plasmids present in stably transfected AK2000 cell lines. Zp mutations which incorporated an additional EcoRI site at the mutation (MIIR, MIIIA, and MIIIA/B) gave short fragments of characteristic lengths. pHEBo-luc lacks Zp and gives a shorter fragment than the wild type (wt). Two lines are shown for each plasmid. (C) Luciferase assay for pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc, MIA/B, and MIC. Cells were induced with anti-IgG and harvested at the times indicated. The proportion of the different cell lines that was induced in response to anti-Ig was determined by flow cytometry of cells stained with BZ1 antibody to be 15% ± 1% (data not shown). The luciferase activity in relative light units (RLU) has been normalized for the plasmid copy number, protein concentration, and proportion of cells induced. Averages for values from two clones and independent experiments are shown. (D) Luciferase assay for pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc, MIIIA, MIIIB, and MIIIA/B. Cells were induced with anti-IgG and harvested at the times indicated. The luciferase activity was normalized and averaged as for panel C (induction frequency was 14% ± 2%). (E) Luciferase assay for MII mutant data, performed as in panel D. Co, control pHEBo-luc.

To test the significance of the previously reported promoter elements in this more quantitative system, pHEBo:Zp-luc constructs carrying mutations in the ZI, ZII, ZIII, and ZV motifs were transfected into EBV-positive AK2000 cells, and stable cell lines were isolated. Cell lines were assayed for plasmid DNA by Southern blotting, and lines maintaining approximately equal amounts of plasmids were chosen (an example of the Southern blots used in this study is shown in Fig. 2B). Some of the mutations introduced an additional EcoRI site and therefore gave a different pattern of digestion. Quantitation with the phosphorimager showed that an average copy number of 22 ± 8 episomes per cell were stably maintained in the different cell lines selected.

First, the mutations in ZIA/B and ZIC were tested for their impact on anti-IgG responsiveness. Figure 2C shows a luciferase assay for an activation time course for MIA/B and MIC. The data are averages for two clones, each assayed in duplicate. The time course supports earlier observations that determined these sites to be very important in the anti-IgG signal response of the Zp promoter. Both mutations rendered the Zp promoter unresponsive in EBV-negative cells (14). The luciferase assay in Fig. 2C shows that these mutations rendered the promoter unresponsive to anti-IgG signaling for the first 6 to 8 h postinduction. There was a small activation at later time points, perhaps reflecting activation through other elements or BZLF1 produced from the EBV genome present in the same cells eventually overcoming the repression of the promoter in latency. During the early part of this time course (0 to 6 h), however, the two mutants were virtually unresponsive to anti-IgG, giving luciferase activity similar to that in a vector control.

This result indicates that during the early phase of Zp activation, the ZIA/B and ZIC sites are indispensable for anti-IgG-induced reactivation. Also, without the MI elements, the Zp promoter on the stably transfected episome does not respond effectively to BZLF1 transactivation via its ZIII sites, since BZLF1 protein is available to bind the ZIII sites as early as 30 min postinduction on the wild-type promoter (3). A mechanism that protects wild-type EBV from Zp reactivation thus appears to be present on these episomal vectors, supporting the argument that this system closely mimics viral reactivation through the wild-type Zp promoter.

The role of the autoactivation elements was then investigated. Figure 2D shows a luciferase assay for an activation time course for MIIIA, MIIIB, and MIIIA/B. Averages for two clones and independent experiments are shown. The result shown in Fig. 2D distinguishes the different roles played by ZIIIA and ZIIIB upon reactivation. A mutation in the ZIIIA site was sufficient to render the Zp promoter unresponsive to anti-IgG signaling. This result is identical to that obtained in EBV-negative Akata cells (14) and indicates that ZIIIA, normally considered a BZLF1 binding sequence, is a crucial element for the primary reactivation by anti-Ig signal transduction.

MIIIA was not activated by the endogenous BZLF1 that could bind to ZIIIB, which is intact in this mutation and is the higher affinity site for BZLF1 (8, 16). Therefore, either BZLF1 needs both ZIII sites to bind and activate its own promoter or an additional signal is needed during the initial activation phase conferred by ZIIIA. Since mutating the ZIIIA site is already sufficient to render Zp unresponsive to anti-IgG signaling, it is not surprising that the double mutation MIIIA/B does not decrease this level of unresponsiveness any further (Fig. 2D).

In contrast, the MIIIB mutant showed biphasic behavior. During the early phase of activation (up to about 3 h postinduction), the MIIIB mutant displayed kinetics similar to the wild-type Zp. However, between 4 and 6 h postinduction, the luciferase activity peaked and then decreased. ZIIIB therefore was dispensable for the initial phase of activation but was important in mediating the autoactivation (after approximately 2 to 3 h). Since ZIIIB is the higher affinity site for BZLF1 binding, the activity of the MIIIB construct may be that which can be achieved without the ZIIIB component of the autoactivation loop. We reported previously that MIIIB had little effect on Zp responsiveness in EBV-negative Akata cells (14), but this discrepancy might be explained by the late time point analyzed in those experiments, allowing accumulation of BZLF1 protein.

Mutation of the ZII element has previously been reported to have little effect on the Zp promoter in the presence of BZLF1 but to be important for the effects of tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate in the absence of BZLF1 (9). Kinetic analysis of the MII mutant showed that the ZII element is required for the rapid early activation of the promoter, but eventually the MII mutant luciferase activity catches up with the wild-type promoter (Fig. 2E).

Negative regulatory elements on Zp.

Sequences of the Zp promoter that are relatively distal to the transcription start site (−554 to −221) have been reported to repress Zp through HI and ZIV sites (22, 23, 27). Figure 3A shows a cartoon of the elements implicated in repression by this region. The HI sites were reported to be bound by unknown transcription factors which dissociate from Zp upon tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate induction (as judged by footprinting assays). The region from −551 to −227 had a repressive effect on heterologous enhancer promoters in EBV-negative cells, and mutations in the HI elements derepressed this construct in EBV-immortalized B-cell lines (27). The ZIV elements have been reported to bind to the cell transcription factor YY1, which can act as a repressor or an activator. Small repressive effects were observed for the −551 to −221 region on basal levels of transcription from the Zp reporter construct when YY1 was overexpressed (22, 23).

FIG. 3.

(A) Reported negative elements in the distal part of Zp (−554 to −221). The positions of each element in Zp relative to the transcription start site are shown (not to scale). (B) Luciferase assay of Zp deletion mutant plasmids in AK2000 cell lines. Luciferase activity in relative light units (RLU) was determined as for Fig. 2C; the proportion of cells that were induced was 10% ± 2%. (C) Comparison of basal levels of Zp-luc activity in AK2000. Untreated cells from AK2000 cell lines containing the indicated plasmids were assayed for luciferase activity in relative light units (RLU), and data were normalized and averaged as for Fig. 2C. Co, control pHEBo-luc.

To evaluate the role of these repressive elements in our more quantitative system, which closely mimics the normal regulation of Zp, sequential deletions were made in this region. The deletions are illustrated in Fig. 3A. Luciferase vectors carrying these Zp deletion mutants were transfected into EBV-positive AK2000, and cells stably maintaining the plasmids were isolated.

Figure 3B shows a luciferase assay for an anti-Ig activation time course of the deletion mutants. Averages for two clones and independent experiments are shown. Deleting the entire distal region (Zp-221) caused only a very modest effect on the luciferase activity of this mutant compared to the wild type. The basal level of transcription was not raised (for a more detailed graph, see Fig. 3C), and the maximal activity at 12 h postinduction increased only slightly. Partial deletions of this region also had little effect on Zp activity. None of the mutations had a major effect on the basal level of the Zp promoter without anti-Ig induction. Thus, the distal region most likely does not account for the repressed state of Zp in latency. The plasmid −221ZpXBZLF1 was found to produce more protein than −554ZpXBZLF1 when stably transfected into EBV-negative Akata cells (14), but the difference was small, and those experiments were not controlled for plasmid copy number and induction rate of the cell lines as accurately as those described here.

Two other regions of Zp have been reported to mediate repression or silencing of the promoter, ZIIR (18) and ZV (17) (see diagram in Fig. 1A). Mutation of ZIIR was reported to cause to a 5- to 10-fold increase in basal transcriptional activity and tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate-induced activity of Zp over the wild type in transient-transfection assays in EBV-negative DG75 cells. In EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma cells (P3HR1), the effect was approximately sevenfold, but no cellular binding factor could be found (18). Mutation of the ZV site (17) was shown to relieve the repression of Zp about fourfold and to cause a superactivation of Zp (about 20-fold over the wild-type level) when induced with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate in DG75 cells in transient transfections. The factor binding to ZV, called ZVR, was shown not to dissociate from Zp upon induction with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate. The identity of this factor is not known, but it was suggested (17) to be ZEB (zinc finger E-box binding protein). Both potential repressor sites were tested only in transient-transfection assays and only with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate induction.

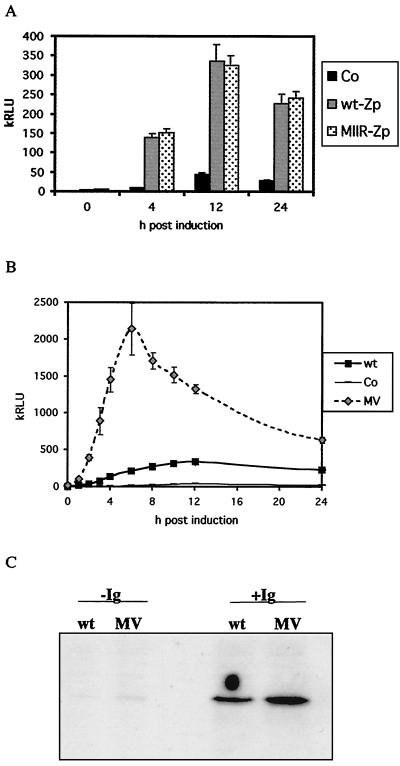

Mutations in the ZIIR or ZV sequences were introduced into pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc, the plasmids were transfected into EBV-positive AK2000 cells, and stable clones were isolated. Figure 4A shows a luciferase assay for the MIIR mutant. Averages for two clones and independent experiments are shown. The luciferase assay in Fig. 4A shows no significant difference between wild-type and MIIR luciferase activities. Thus, mutation in ZIIR did not influence the anti-IgG responsiveness of Zp or the timing of activation in response to anti-Ig induction in EBV-positive Akata cells. The effect of MIIR on the basal levels of Zp transcription was also very small. As shown in Fig. 3C, MIIR elevated basal transcription about 1.6-fold compared to the wild-type level. The data therefore suggest that ZIIR does not play a major role in Zp repression.

FIG. 4.

(A) Luciferase assay of Zp mutant plasmids in AK2000 cell lines. The proportion of cells that were induced was 14% ± 1% (data treated as for Fig. 2C). (B) Luciferase assay for pHEBo:MV-Zp-luc in AK2000 cells. The proportion of cells that were induced was 13% ± 2% (data treated as for Fig. 2C). (C) Transient-transfection assay for p294:Zp-MV-BZLF1 in AK31 cells. Cells were transfected by electroporation with 10 μg of p294:Zp-MV-BZLF1 or p294:Zp-552Xwt plasmid DNA and then incubated for 16 h to recover. Cells were then treated with anti-Ig (+Ig) or left untreated (−Ig) and harvested 24 h later. Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting probed with the BZ1 antibody. Transfection efficiency was measured by cotransfection of pCMV-βgal. Amounts of extract loaded on the gel were corrected for β-galactosidase activity and protein concentration. Lanes: wt, transfected with p294:Zp-wt-BZLF1; MV, transfected with p294:Zp-MV-BZLF1. Co, control pHEBo-luc.

When the mutation in ZV was tested, the luciferase assay (Fig. 4B) showed rapid activation of the MV mutant in response to anti-Ig. The change of scale required to display the very high activity of MV makes the Zp wild-type curve look flatter than normal. As early as 1 h postinduction, the MV luciferase activity exceeded that of the wild type. The maximum activity was reached after 6 h, half the time taken by the wild-type Zp to peak. The maximum was about eightfold higher than the wild-type level, after which activity levels for MV declined. MV also affected the basal level of transcription. Figure 3C shows that MV was the only mutation that significantly derepressed Zp. Basal levels for MV mutant cell lines were almost fivefold higher than that of the wild type. Thus, the ZV element is a regulating element of Zp that can also function as a transcriptional silencing element in the uninduced state in EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma cells. The position downstream of the TATA box makes this a likely site for repressor binding. It was concluded in earlier work (17) that ZVR does not dissociate from Zp upon induction by tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate, and ZVR may also remain bound to the Zp promoter to limit this activation during anti-Ig induction.

Partial relief of repression on Zp might cause limited BZLF1 expression and subsequent activation of the autoactivation loop, leading to a constitutively active Zp promoter. To test this in the Zp-BZLF1 system used previously (14), the MV mutation was cloned back into p294:-554ZpXBZLF1 (14) and transiently transfected into EBV-negative AK31 cells. For this experiment, transient transfections were used because constitutive BZLF1 expression is thought to be toxic for the transfected cells and could result in selection of nonrepresentative cells in stably transfected lines. Figure 4C shows a Western blot of BZLF1 expressed in the transient-transfection assay. Without anti-Ig induction, MV slightly increased BZLF1 expression but did not render the Zp promoter constitutively active. In the anti-Ig-induced cells, the mutation in MV caused a higher level of BZLF1 expression, although the difference between the wild type and MV was only about threefold here, compared to eightfold in the luciferase assay. Thus, it appears that induction of Zp involves overcoming both a repressive chromatin structure via the factors on the ZI elements and the repressive effects of the ZV binding protein ZVR.

What limits Zp activity and makes Zp go off?

It is evident from the time course of luciferase expression of wild-type Zp in pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc that the induction of Zp by anti-Ig is transient, with luciferase peaking at about 12 h after addition of anti-Ig (Fig. 1). The luciferase protein seemed to be less stable than BZLF1 in Akata cells but still has a significant half-life which tends to mask the transient nature of Zp activity. Nuclear run-on experiments indicated that Zp is active for about 3 h after anti-Ig induction (21). One obvious factor limiting Zp activity may be the transient nature of the signaling from anti-Ig induction. This presumably limits the presence of activated forms of the transcription factors that bind to the various promoter elements described above. BZLF1 is also involved in lytic replication of the viral genome.

We investigated whether viral DNA replication might be involved in limiting Zp activity by testing whether prevention of DNA replication affects the time course of Zp induction. Phosphonoacetic acid and acyclovir inhibit viral DNA replication and prevented EBV late-gene expression from the EBV genome in the cells (Fig. 5C), but prolonged Zp induction of the plasmid and delayed the subsequent decline in luciferase activity after anti-Ig induction (Fig. 5A). An analogous increase in BZLF1 protein expression from the endogenous EBV genome was observed in the presence of phosphonoacetic acid (Fig. 5B). There thus appears to be a mechanism involving replication of the viral DNA or a late gene product that limits Zp activity. There was no ori-lyt sequence in the Zp plasmid, so this seems unlikely to be a consequence of lytic replication of the reporter plasmid. Testing the decay of luciferase activity in the presence of cycloheximide showed no difference in the half-life of the luciferase enzyme caused by phosphonoacetic acid or acyclovir (the half-life for the luciferase activity was about 50 h; data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effect of phosphonoacetic acid (PAA) and acyclovir on Zp-luciferase induction. (A) pHEBo:Zp-wt-luc in AK2000 cells was induced with anti-Ig with or without 0.85 mM phosphonoacetic acid or 100 μg of acyclovir per ml, and samples were assayed at the indicated times for luciferase (data treated as for Fig. 2C). (B to D) Protein samples taken from the experiment shown in panel A were analyzed by Western blotting for BZLF1 (B), BdRF1 (C), or LMP1 (D). Lane BM in panel D contains an extract of the EBV-immortalized B-cell line BM+Akata, a positive control for Akata LMP1.

We previously described how the late lytic cycle protects Akata cells against apoptosis caused by inducers of the lytic cycle (13). This apoptosis might be expected to reduce the reporter activity measured, so the true increase in luciferase expression caused by phosphonoacetic acid or acyclovir might be even greater than that shown in Fig. 5. As reported earlier (26), induction of the LMP1 protein was observed in response to anti-Ig treatment of the Akata cells (Fig. 5D), and this was prevented by phosphonoacetic acid treatment. It has been shown recently that LMP1 can suppress Zp activity (1), so this may be the mechanism.

It was noticeable that the MV mutant luciferase activity peaked earlier than that of the wild-type promoter (Fig. 4B). This could result from MV activity being limited by a different mechanism from the wild type; for example, the MV activity may be limited by the availability of other cooperating transcription factors on Zp, whereas the wild-type activity is limited by the factors operating through ZV. The results do not, however, exclude the possibility that ZV also affects Zp shutoff.

DISCUSSION

The luciferase reporter system described here reconstitutes the proper control of Zp on small plasmids that was reported in our earlier work (14) but provides much more quantitative data and allows study of the time course of reporter gene expression. By working with EBV-positive cells, we ensure that trans-acting viral factors are provided from the endogenous EBV with the correct timing and at physiologically normal concentrations.

The ZIA, ZIB, ZII, and ZIIIA elements are all essential for the early induction of Zp in response to anti-Ig. ZIA and ZIB have been reported to bind the MEF-2D transcription factor (19), and rapid modification of MEF-2D (involving protein dephosphorylation) in response to BCR signaling has been found in the accompanying paper to correlate with the induction (3). We showed previously that reactivation of Zp involves histone deacetylation of the chromatin containing Zp, and the role of the ZI elements in reactivation can be substituted for by trichostatin A treatment of the cells (14). Since MEF-2D is known to be able to bind histone deacetylases in resting T cells but switches to an activating form in response to calcium-mediated signaling (reviewed in reference 5), similar to that which is induced in B cells in response to BCR activation, all the data indicate that signaling through MEF-2D bound to the ZI elements is part of the primary mechanism of reactivation of EBV from latency. The cell factors which bind to the ZIIIA site have not yet been identified, but it is clear that this site is also involved in the primary activation. Mutation of the ZII site greatly reduces the initial activation, but eventually the luciferase activity catches up with the wild-type promoter.

Autoactivation of the Zp promoter by BZLF1 protein is an important part of the reactivation mechanism (30), and this could be seen in the time course of the ZIIIB mutant (Fig. 2D), which initially induced normally but then failed at about 4 h after addition of anti-Ig, when BZLF1 expression was evident (Fig. 1C). ZIIIB has the higher affinity of the two BZLF1 binding sites in Zp (8, 16). We could not assess autoactivation through the ZIIIA element in our system because it was essential for the primary induction.

The Zp promoter elements that have been reported to lie upstream of −221 did not appear to have any significant effect in the assays shown here. It might be expected that the key elements for Zp would lie in the intergenic region between the BRLF1 and BZLF1 coding sequences, but the proposed elements upstream of −221 lie under the BRLF1 coding sequence. It should be noted, however, that in our Zp plasmids, an influence of oriP possibly masking the effects of these elements cannot be excluded, since oriP is located much closer to Zp than is normally the case in the EBV genome.

When introduced singly, none of the mutations studied here resulted in a constitutively active Zp promoter. The MV mutation raised the background expression from Zp about fivefold and increased the peak anti-Ig induction about 15-fold over the wild-type promoter, but MV remained highly dependent on BCR signaling for activity. The MV mutant activity peaked earlier than the wild-type promoter after anti-Ig induction. It thus appears that the factor bound to the ZV sequence attenuates the promoter activity substantially, as reported in the earlier transient assays (17). The ZVR factor that binds to the ZV element has not yet been identified, but it is an important negative modulator of the promoter. Potential variation of expression of the factors that bind to these sites on Zp in different cell types would be expected to influence Zp activity and might affect permissivity for the virus in different cell types.

The time course of luciferase activity is consistent with an earlier nuclear run-on study in which Zp transcription was found to have peaked and reduced again by 4 h after anti-Ig induction (21). Zp switch-off probably largely reflects the transient nature of the BCR signaling (3), but there also appears to be a component of the switch-off that involves late viral gene function. Acyclovir and phosphonoacetic acid increased luciferase expression from the wild-type Zp promoter. Since there is no ori lyt sequence in the luciferase plasmids used here, this is not likely to involve plasmid replication or relocation to intranuclear sites of replication. One possible explanation is induction of the LMP1 protein in response to anti-Ig treatment of Akata cells (26). Although only the truncated, lytic LMP1 RNA behaved as a late mRNA in B95-8 cells (11), expression of both the full-length and lytic forms was prevented by phosphonoacetic acid in Akata cells (Fig. 5D). It has been shown recently that LMP1 can suppress Zp activity (1), and this may be the mechanism by which late-gene expression limited Zp activity in our experiments.

Cancer therapy depends on exploiting differences between tumor cells and normal cells. The presence of the virus in EBV-associated cancers is a major difference between the tumor cells and most normal cells in the body. Reactivation of the viral lytic cycle, perhaps blocking viral DNA synthesis with acyclovir to avoid production of virus particles, is one mechanism by which the presence of the virus could be exploited in cancer therapy. Since BZLF1 is highly antigenic (25) and also causes cell cycle arrest in some tumor cells (4), nontoxic compounds which can induce the EBV lytic cycle could be useful. The luciferase assay system described here could be suitable for high-throughput screening for inducers of the Zp promoter and hence the lytic cycle of EBV. Such a screen might provide lead compounds for therapy of tumors containing latent EBV.

The system described here provides the molecular genetic analysis of the Zp promoter that is the basis for subsequent biochemical investigation of the transcription factors that bind to Zp and mediate reactivation of EBV in Akata cells. This is described in the accompanying paper (3).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenzo Takada for the AK2000 cells and Jaap Middeldorp for the BdRF1 antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, B., E. Schaadt, B. Kempkes, U. Zimber-Strobl, B. Baier, and G. W. Bornkamm. 2002. Control of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation by activated CD40 and viral latent membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:437-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer, G., P. Hofler, and M. Simon. 1982. Epstein-Barr virus induction by a serum factor. Characterization of the purified factor and the mechanism of its activation. J. Biol. Chem. 257:11411-11415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant, H., and P. J. Farrell. 2002. Signal transduction and transcription factor modification during reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 76:10290-10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Cayrol, C., and E. K. Flemington. 1996. The Epstein-Barr virus bZIP transcription factor Zta causes G0/G1 cell cycle arrest through induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. EMBO J. 15:2748-2759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corcoran, E. E., and A. R. Means. 2001. Defining Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascades in transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2975-2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.di Renzo, L., A. Altiok, G. Klein, and E. Klein. 1994. Endogenous TGF-beta contributes to the induction of the EBV lytic cycle in two Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 57:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahmi, H., C. Cochet, Z. Hmama, P. Opolon, and I. Joab. 2000. Transforming growth factor beta 1 stimulates expression of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 immediate-early gene product ZEBRA by an indirect mechanism which requires the MAP kinase pathway. J. Virol. 74:5810-5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Autoregulation of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J. Virol. 64:1227-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Identification of phorbol ester response elements in the promoter of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J. Virol. 64:1217-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruffat, H., E. Manet, and A. Sergeant. 2002. MEF2-mediated recruitment of class II histone deacetylase at the EBV immediate early gene BZLF1 links latency and chromatin remodeling. EMBO Rep. 3:141-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson, G. S., P. J. Farrell, and B. G. Barrell. 1985. Two related but differentially expressed potential membrane proteins encoded by the EcoRI Dhet region of Epstein-Barr virus B95-8. J. Virol. 53:528-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inman, G., and M. Allday. 2000. Apoptosis induced by TGF-β1 in Burkitt's lymphoma cells is caspase 8 dependent but death receptor independent. J. Immunol. 165:2500-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inman, G. J., U. K. Binne, G. A. Parker, P. J. Farrell, and M. J. Allday. 2001. Activators of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic program concomitantly induce apoptosis, but lytic gene expression protects from cell death. J. Virol. 75:2400-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins, P., U. Binné, and P. Farrell. 2000. Histone acetylation and reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 74:710-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kieff, E., and A. Rickinson. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication, p. 2511-2573. In D. Knipe and P. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 16.Kouzarides, T., G. Packham, A. Cook, and P. J. Farrell. 1991. The BZLF1 protein of EBV has a coiled coil dimerisation domain without a heptad leucine repeat but with homology to the C/EBP leucine zipper. Oncogene 6:195-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraus, R. J., S. J. Mirocha, H. M. Stephany, J. R. Puchalski, and J. E. Mertz. 2001. Identification of a novel element involved in regulation of the lytic switch BZLF1 gene promoter of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 75:867-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, P., S. Liu, and S. Speck. 1998. Identification of a negative cis element within the ZII domain of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch BZLF1 gene. J. Virol. 72:8230-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, S., P. Liu, A. Borras, T. Chatila, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Cyclosporin A-sensitive induction of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch is mediated via a novel pathway involving a MEF2 family member. EMBO J. 16:143-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann, K. P., D. Staunton, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1985. Epstein-Barr virus encoded protein found in plasma membrane in transformed cells. J. Virol. 55:710-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellinghoff, I., M. Daibata, R. E. Humphreys, C. Mulder, K. Takada, and T. Sairenji. 1991. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus genome expression after activation: regulation by second messengers of B cell activation. Virology 185:922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montalvo, E. A., M. Cottam, S. Hill, and Y. J. Wang. 1995. YY1 binds to and regulates cis-acting negative elements in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J. Virol. 69:4158-4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Montalvo, E. A., Y. Shi, T. E. Shenk, and A. J. Levine. 1991. Negative regulation of the BZLF1 promoter of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 65:3647-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Packham, G., M. Brimmell, D. Cook, A. Sinclair, and P. Farrell. 1993. Strain variation in Epstein-Barr virus immediate early genes. Virology 192:541-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rickinson, A. B., and D. J. Moss. 1997. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:405-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowe, M., A. L. Lear, D. Croom-Carter, A. H. Davies, and A. B. Rickinson. 1992. Three pathways of Epstein-Barr virus gene activation from EBNA1-positive latency in B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 66:122-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarzmann, F., N. Prang, B. Reichelt, B. Rinkes, S. Haist, M. Marschall, and H. Wolf. 1994. Negatively cis-acting elements in the distal part of the promoter of Epstein-Barr virus trans-activator gene BZLF1. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1999-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu, N., and K. Takada. 1993. Analysis of the BZLF1 promoter of Epstein-Barr virus: identification of an anti-immunoglobulin response sequence. J. Virol. 67:3240-3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinclair, A. J., M. Brimmell, F. Shanahan, and P. J. Farrell. 1991. Pathways of activation of the Epstein-Barr virus productive cycle. J. Virol. 65:2237-2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speck, S., T. Chatila, and E. Flemington. 1997. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus: regulation and function of the BZLF1 gene. Trends Microbiol. 5:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takada, K. 1984. Cross-linking of cell surface immunoglobulins induces Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Int. J. Cancer 33:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takada, K., and Y. Ono. 1989. Synchronous and sequential activation of latently infected Epstein-Barr virus genomes. J. Virol. 63:445-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Grunsven, W. M., E. C. van Heerde, H. J. de Haard, W. J. Spaan, and J. M. Middeldorp. 1993. Gene mapping and expression of two immunodominant Epstein-Barr virus capsid proteins. J. Virol. 67:3908-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yates, J., N. Warren, D. Reisman, and B. Sugden. 1984. A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:3806-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]