Abstract

Retroviruses utilize an unspliced version of their primary transcription product as an RNA template for synthesis of viral Gag and Pol structural and enzymatic proteins. Cytoplasmic expression of the gag-pol RNA is achieved despite the lack of intron removal and the presence of a long and highly structured 5′ untranslated region that inhibits efficient ribosome scanning. In this study, we have identified for the first time that the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) facilitates Rev/Rev-responsive element-independent expression of HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA. The MPMV RU5 region of the LTR is necessary and directs functional interaction with cellular posttranscriptional modulators present in human 293 and monkey COS cells but not in quail QT-6 cells and does not require any viral protein. Deletion of MPMV RU5 decreases the abundance of spliced mRNA but has little effect on cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced gag-pol RNA despite complete elimination of detectable Gag protein production. MPMV RU5 also exerts a positive effect on the cytoplasmic expression of intronless luc RNA, and ribosomal profile analysis demonstrates that MPMV RU5 directs subcellular localization of the luc transcript to polyribosomes. Our findings have a number of similarities with those of reports on 5′ terminal posttranscriptional control elements in spleen necrosis virus and human foamy virus RNA and support the model that divergent retroviruses share 5′ terminal RNA elements that interact with host proteins to program retroviral RNA for productive cytoplasmic expression.

Retroviruses need to subvert typical cellular posttranscriptional control mechanisms to produce progeny virions. Typical pre-mRNAs are assembled in ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes during transcription and RNA maturation that qualify processed transcripts for nuclear export and efficient cytoplasmic expression (11, 24, 26, 30). By contrast, retroviral pre-mRNA recruits viral or cellular posttranscriptional modulators that activate efficient nuclear export and cytoplasmic expression despite lack of intron removal (2, 12, 25, 44). Once in the cytoplasm, the unspliced viral transcript exhibits dual function as mRNA template for translation of Gag precursor protein and Gag-Pol polyprotein and as genomic RNA that is packaged into progeny virions (6). The RNA packaging signal is a series of RNA structural motifs within the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) that are recognized by the Gag nucleocapsid protein, which directs assembly of the unspliced RNA into progeny virions (1, 35). Structured 5′ UTRs typically inhibit efficient translation by steric hindrance of ribosome scanning from the 5′ cap to the proximal start codon (19, 29, 34). Mutational analysis of structural motifs in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) 5′ UTR has verified that they inhibit efficient translation (18, 31, 33). Thus, the unspliced viral RNA subverts typical barriers to both nuclear export and efficient translation to achieve productive cytoplasmic expression of viral structural and enzymatic proteins.

HIV-1 is a complex retrovirus that encodes the viral posttranscriptional regulatory protein Rev. Rev interacts with newly synthesized viral RNA (22) at the Rev-responsive element (RRE) present in distal intronic sequences to activate nuclear export despite lack of intron removal (8, 20, 21, 28, 46). Rev connects RRE-containing RNA to the CRM1/exportin 1 nuclear export receptor, which is typically utilized by 5S rRNA and shuttling proteins that contain a leucine-rich nuclear export sequence (17, 32). Genetically simpler retroviruses lack a viral Rev protein. However, the type D Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) and simian retrovirus type 1 contain a functional homolog of RRE, which is designated the constitutive transport element (CTE). The CTE is a redundant stem-loop structure that is positioned in the 3′ UTR and facilitates nuclear export of intron-containing RNA in transfected cells (5, 15, 16, 38, 42). CTE facilitates nuclear export by interaction with Tap and cofactor NXT1, which have been implicated as global modulators of the nuclear export of fully processed cellular mRNAs (4, 25, 44). Recently, studies of two other retroviruses have identified 5′ proximal RNA sequences encoded by the long terminal repeat (LTR) that facilitate cytoplasmic expression of intron-containing viral RNA but do not function solely as nuclear export elements.

The spleen necrosis virus (SNV) 5′ LTR contains a positive posttranscriptional control element (PCE) that facilitates Rex/RxRE-independent expression of bovine leukemia virus structural and enzymatic proteins in studies of hybrid SNV-bovine leukemia virus genomes (3). Analysis of hybrid SNV-HIV-1 reporter plasmids indicates that the SNV 5′ LTR also facilitates Rev/RRE-independent expression of the intron-containing HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA and that the RU5 region, which corresponds to the 5′ RNA terminus, is sufficient for activity (7). Quantitative RNA and protein analysis demonstrates that low levels of gag-pol reporter RNA accumulate in the cytoplasm in the presence and absence of SNV RU5 but are not translated unless RU5 is present. SNV RU5 functions in an orientation- and position-dependent manner to facilitate the cytoplasmic expression of HIV-1 gag-pol RNA and also to augment the cytoplasmic expression of nonviral luciferase (luc) RNA (7, 36). Ribosomal profile analysis indicates that SNV RU5 increases the subcellular localization of these reporter RNAs with polyribosomes. Reporter gene assays with bicistronic reporter RNAs eliminate the possibility that SNV RU5 is an internal ribosome entry site and indicate that SNV RU5 enhances translational initiation by a distinct mechanism (36). Results of RNA transfection and of conventional reporter gene assays demonstrate that nuclear interactions are necessary for stimulation of cytoplasmic expression by SNV RU5 (13). The nuclear export pathway of SNV RU5-containing RNA is distinct from the leucine-rich nuclear export sequence-dependent CRM1 pathway accessed by Rev/RRE. However, when Rev is tethered by the RRE to an SNV RU5-containing RNA, Rev/RRE acts dominantly to sequester the transcript to the CRM1 nuclear export pathway and eliminates translational enhancement by SNV RU5. The data support the model that Rev/RRE acts upstream of SNV RU5 or disrupts interaction between SNV RU5 and nuclear posttranscriptional modulators that program SNV RU5-containing RNAs for efficient cytoplasmic expression.

Similar to SNV RU5, the R region in the human foamy virus (HFV) 5′ LTR has been shown to confer productive cytoplasmic expression of intron-containing viral RNA (37). HFV R functions in an orientation- and position-dependent manner and is necessary and sufficient for detectable HFV Gag and Pol protein synthesis. HFV R also has minimal effect on the cytoplasmic accumulation of HFV unspliced gag RNA but is necessary for detectable Gag production (37). Similar levels of HFV gag RNA accumulate in the cytoplasm in both the presence and absence of R; however, Gag protein is exclusively expressed from the R-containing transcripts. Because HFV R is necessary for HFV Gag translation, Russell and colleagues postulate that R directs the RNA to a proper cytoplasmic environment that is necessary for expression of the unspliced gag RNA (37). The potential positive effect of HFV R on RNA localization with polyribosomes has not been determined.

Studies herein demonstrate that the RU5 region of the MPMV 5′ LTR facilitates Rev/RRE-independent expression of HIV-1 gag-pol RNA. MPMV RU5 functions independently of any MPMV protein and is active in human and simian but not avian cell lines, implying that MPMV RU5 recruits cellular posttranscriptional modulators. Quantitative RNA and protein analyses indicate that MPMV RU5 has minimal effect on cytoplasmic accumulation but is necessary for cytoplasmic expression of the intron-containing HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA and also augments cytoplasmic expression of intronless luc reporter RNA. Ribosome profile analysis on RU5-luc RNA demonstrates that MPMV RU5 increases the cytoplasmic localization of luc RNA with polyribosomes. Taken together, this and previous studies indicate that MPMV and SNV RU5 and HFV R sequences share a common ability to facilitate cytoplasmic expression of intron-containing RNA. We suggest that 5′ terminal PCEs are a feature shared by divergent retroviruses to facilitate translation despite lack of intron removal and the presence of a long and highly structured 5′ UTR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The construction of cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early promoter/enhancer and 5′ SNV LTR HIV-1 gag-pol reporter plasmids was previously described (7). To create the MPMV reporter plasmids, the SNV LTR sequence in pYW100 was replaced with PCR amplification products that contain either the 5′ MPMV U3RU5 (nucleotides [nt] 1 to 350) or U3 (MPMV ΔRU5) (nt 1 to 105) from pSHRM (a kind gift of E. Hunter, University of Alabama, Birmingham) at NdeI and BamHI sites. The luc reporter plasmids were constructed by replacing the entire HIV-1 sequence with luc from pGL3 (Promega) at BamHI and XbaI sites. gag sequences of p37 M1-4 (a kind gift of B.K. Felber, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md.), which contain inactivated inhibitory sequences (INS-1) (40), were introduced into MPMV to create MPMVM1-4.

DNA transfection and analysis of protein production.

Triplicate reporter gene assays were performed on protein from 105 293 cells transfected by a CaPO4 protocol (7) or 3 × 105 COS or QT-6 cells transfected by a Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) protocol (7) in three replicate 33-mm-diameter plates. The cells were harvested 48 h later in phosphate-buffered saline, centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 3 min, and resuspended in 0.2 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40). HIV Gag levels were quantified by a Gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter Corp., Miami, Fla.) and normalized to Luc activity from cotransfected pGL3 (Promega). Luc assays were performed with 10 μl of lysate and 100 μl of Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) and quantified in a Lumicount luminometer (Packard, Meriden, Conn.). Dual measurement of the Lucs expressed from the firefly (Photinus pyralis) luc and sea pansy (Renilla reniformis) ren genes was performed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

RNA preparation.

RNA was harvested 48 h posttransfection of 106 293 cells in 100-mm-diameter plates. For preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA, cells were resuspended in 0.4 ml of hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) and placed on ice for 10 min, followed by gentle vortexing for 10 s (45). Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 2 min at 4°C. The cytoplasmic supernatant was subjected to a second centrifugation, the clarified supernatant was mixed with 3 volumes of Tri-Reagent LS (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio), and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol. The nuclear fraction was washed once in 0.5 ml of hypotonic buffer and treated with 1 ml of Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). All RNA preparations were treated three times with DNase (Promega) and were subjected to phenol chloroform extraction, chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation.

For ribosomal profile analysis, 107 293 cells in T150 flasks were transfected and treated 48 h later with 100 μg of cycloheximide/ml for 15 min at 37°C. The cells were harvested in phosphate-buffered saline, and the cytoplasmic fraction was isolated by the hypotonic buffer protocol. The cytoplasmic supernatant was then layered onto a 10-ml linear gradient of 15 to 45% sucrose in 10 mM HEPES containing 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 7 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol and was centrifuged at 36,000 × g at 4°C for 3.5 h in a Beckman SW41 rotor (39). Gradients were fractionated, and the A254 was monitored using an ISCO (Lincoln, Nebr.) fractionation system. Each fraction was subjected to phenol chloroform and chloroform extraction, and the RNA was precipitated with ethanol.

RNA analysis.

For RNA protection assays (RPA), 15 μg of nuclear RNA and 25 μg of cytoplasmic RNA were analyzed as previously described (7). For Northern blot analysis, 10 μg of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA was separated on 1.2% agarose gels containing 5% formaldehyde, transferred to Duralon-UV membranes (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and incubated with either luc or cyclophilin (cp) gene DNA probes. The probes were prepared by a random-primer DNA-labeling system (Gibco-BRL) with gel-purified luc or cp PCR products and [α-32P]dCTP. The hybridization products were subjected to PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) analysis with ImageQuant version 4.2 (Molecular Dynamics). For ribosomal profile analysis, the entire RNA sample from each fraction was used and the membranes were prepared as described above and incubated with uniformly labeled luc RNA probe synthesized with MAXscript T7 polymerase (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The hybridization products were subjected to quantification by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) analysis.

RESULTS

MPMV 5′ LTR facilitates Rev/RRE-independent HIV-1 Gag production.

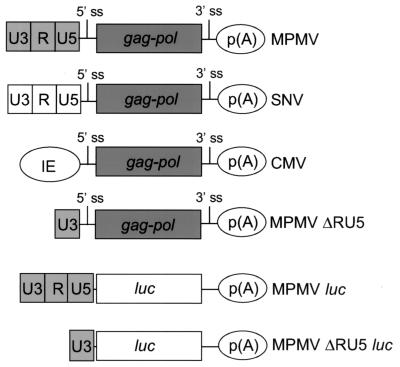

A collection of HIV-1 gag-pol reporter plasmids was used to investigate the potential positive effect of the 5′ MPMV LTR on posttranscriptional gene expression (Fig. 1). The reporter plasmids were analyzed for Rev/RRE-independent Gag production by HIV-1 Gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on cell-associated protein from transfected 293 cells. The MPMV reporter plasmids were compared to two previously characterized reporter plasmids (7). The negative control CMV reporter plasmid has been shown to produce less than detectable levels of Gag, while the SNV 5′ LTR reporter plasmid exhibits Rev/RRE-independent Gag production. Three independent reporter gene assays were performed in triplicate, and the results indicate that Gag is produced from the MPMV and SNV LTR reporter plasmids but not from the negative control (Table 1). The data indicate that the MPMV LTR facilitated a ≥100-fold increase in Gag production. For example, Rev/RRE-independent Gag production was 10.3 ± 0.5 ng/ml for MPMV, 37.9 ± 10.8 ng/ml for SNV, and less than 0.1 ng/ml for CMV. Deletion of RU5 from the MPMV LTR gag-pol reporter plasmid (MPMV ΔRU5) eliminated Rev/RRE-independent Gag production (Table 1). These results demonstrate that MPMV RU5 is necessary for Rev/RRE-independent Gag production. To determine the effectiveness of the MPMV LTR, we compared its level of Gag production to that produced in response to Rev/RRE or CTE. The 293 cells were transfected with equivalent amounts of previously characterized reporter plasmids: pSVgagpol; pSVgagpol-rre in the presence and absence of pRev; and pSVgagpol-MPMV, which contains the MPMV CTE (5). As expected, the negative control pSVgagpol and pSVgagpol-rre reporter plasmids produced less than detectable levels of Gag (≤0.1 ng/ml). Cotransfection of pRev with pSVgagpol-rre or introduction of MPMV CTE to pSVgagpol (pSVgagpol-MPMV) yielded a Gag level of 57.2 ± 2.9 or 31.8 ± 5.4 ng/ml, respectively. The data indicate that HIV-1 Gag production facilitated by MPMV RU5 is comparable in magnitude to that produced in response to Rev/RRE or MPMV CTE.

FIG. 1.

Summary of the structures of the gag and luc reporter plasmids. Shown in light gray are the U3, R, and U5 regions of the MPMV LTR; shown in white are the U3, R, and U5 regions of the SNV LTR; 5′-terminal oval, CMV immediate-early (IE) promoter-enhancer; dark gray rectangles, HIV gag-pol coding region; 5′ and 3′ ss, splice sites; white rectangles, luc coding regions; and 3′ terminal oval labeled “p(A),” polyadenylation signal.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Gag protein production

| Expt no. | Plasmid | Gag concn (ng/ml)a in 293 cells (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MPMV | 10.3 ± 0.5 |

| SNV | 37.9 ± 10.8 | |

| CMV | <MDb | |

| MPMV ΔRU5 | <MD | |

| 2 | MPMV | 24.4 ± 11.0 |

| SNV | 67.0 ± 3.0 | |

| CMV | <MD | |

| MPMV ΔRU5 | <MD | |

| 3 | MPMV | 11.4 ± 1.0 |

| SNV | 19.7 ± 2.2 | |

| CMV | <MD | |

| MPMV ΔRU5 | <MD |

Cell-associated Gag levels measured from triplicate transfections normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

<MD, less than minimum detectable (0.1 ng/ml).

Next we analyzed whether Rev/RRE-independent Gag production by MPMV RU5 is augmented by mutation of INS-1. The cis-acting INS sequences interact with host cell factors and confer instability of HIV-1 RNA, which is derepressed by Rev association with RRE or by point mutation (9, 27, 40, 41). Consistent with published results, two independent reporter gene assays performed in triplicate demonstrated that INS-1 mutation increased Gag production from the previously characterized p37 HIV-1 control plasmid in 293 cells (36, 40). For example, Gag production from p37 increased from less than 0.1 to 27.1 ± 6.4 ng/ml upon mutation of INS-1 (p37 M1-4). By contrast, INS-1 mutation had no significant effect on Gag production from the MPMV reporter plasmid (26.2 ± 2.6 and 35.8 ± 1.3 ng/ml for wild-type MPMV and MPMV with an INS-1 mutation [MPMVM1-4], respectively). These results indicate that MPMV RU5 facilitates gag expression independently of INS-1.

Cell-type-dependent host proteins modulate MPMV RU5 activity.

To address potential cell-type-dependent differences in activity, we evaluated the MPMV LTR gag-pol reporter plasmids in monkey COS cells, which are fully permissive for MPMV replication (15), and quail QT-6 cells, which are deficient for posttranscriptional expression of MPMV CTE reporter RNA (23). Similar to 293 cells, COS cells supported Rev/RRE-independent Gag production from the MPMV LTR reporter plasmid (31.2 ± 4.2 ng/ml) but exhibited less than the minimum detectable concentration of Gag (≤0.1 ng/ml) from the MPMV ΔRU5 reporter plasmid.

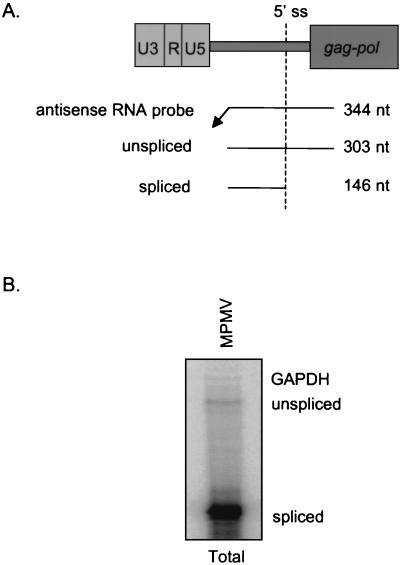

By contrast, the MPMV LTR reporter plasmid did not exhibit Rev/RRE-independent Gag production in quail QT-6 cells. Consistent with previous work in quail cells (23), CTE-containing reporter pSVgagpol-MPMV also lacked Gag production, whereas pSVgagpol-rre plus pRev exhibited Gag production (data not shown). RNA analysis was used to determine whether or not the MPMV LTR was transcriptionally active in QT-6 cells. RPA was performed on total cellular RNA from the transfected cells with a uniformly labeled antisense RNA probe that spans the HIV-1 5′ UTR and detects both unspliced and spliced transcripts (Fig. 2A). RPA analysis detected ample spliced transcript and a low but detectable amount of unspliced gag transcript (Fig. 2B). The data indicate that the lack of Rev/RRE-independent Gag production in QT-6 cells is not attributable to lack of RNA synthesis. Taken together, the data indicate that MPMV RU5 facilitates Rev/RRE-independent Gag production in conjunction with host cell proteins present in human and monkey but not quail cells.

FIG. 2.

RPA of total cellular RNA from transfected QT-6 quail cells verifies reporter RNA synthesis. (A) Relationship among the gag-pol reporter plasmid, the uniformly labeled antisense runoff HIV-1 5′ UTR RNA probe, and protected unspliced and spliced transcripts with sizes indicated. (B) Forty-eight hours posttransfection total RNA was isolated and treated with DNase. Twenty micrograms was subjected to RPA with uniformly labeled antisense HIV-1 5′ UTR and gapdh RNA probes and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Labels indicate the reporter plasmid, RNA preparation, and protected transcripts.

MPMV RU5 positively affects cytoplasmic expression of HIV-1 gag-pol RNA.

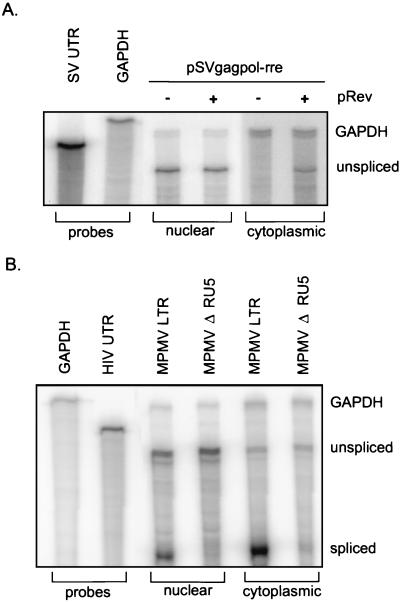

Quantitative RPAs were used to determine the effect of MPMV RU5 on RNA processing and cytoplasmic accumulation. To assess the quality of our nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fractionation, RNA was analyzed from 293 cells transfected with pSVgagpol-rre in the absence or presence of pRev. The RPA probe is complementary to the pSVgagpol-rre 5′ UTR and detects the unspliced gag RNA as a 290-nt RNase protection product. To assess equal sample loading, we utilized a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) cellular RNA probe that detects a 433-nt RNase protection product. Appropriate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation of the gag RNA is indicated by the observation of unspliced gag RNA from pSVgagpol-rre in the cytoplasm solely in the presence of Rev (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

RPA of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA from transfected 293 cells reveals that deletion of MPMV RU5 does not reduce the steady-state unspliced gag RNA level but does reduce the spliced RNA level. Forty-eight hours posttransfection RNAs were isolated and treated with DNase. Nuclear (15 μg) and cytoplasmic (25 μg) RNAs were subjected to RPA with uniformly labeled antisense 5′ UTR and gapdh RNA probes and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Labels indicate the reporter plasmid, RNA preparation, and protected transcript. (A) Analysis of pSVgagpol-rre reporter RNA in the presence or absence of pRev. (B) Analysis of MPMV LTR and MPMV ΔRU5 reporter RNA.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA was harvested from 293 cells transfected with MPMV or MPMV ΔRU5 gag-pol reporter plasmids. We detected the expected 303- and 146-nt RNase protection products of the unspliced and spliced reporter transcripts, respectively (Fig. 3B). As noted above, equal sample loading was confirmed by gapdh hybridization. The results consistently demonstrate that deletion of MPMV RU5 decreased the abundance of the spliced transcript (Table 2). Notably, deletion of MPMV RU5 had minimal affect on the overall steady-state level or cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced gag RNA, despite elimination of detectable Gag protein synthesis. The data indicate that MPMV RU5 affects RNA processing and increases the splicing efficiency of the reporter transcript. Together the RPA and protein analysis results demonstrate that RU5 is necessary for productive cytoplasmic expression of the HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of HIV-1 gag reporter RNAa

| Reporter | Amt in PhosphorImager units (105)b of nuclear RNA

|

Nuclear RNA SEc | Amt in PhosphorImager units (105) of cytoplasmic RNA

|

Cytoplasmic RNA SE | CAd

|

CEe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | Concn of Gagf | Unspliced | Spliced | Unspliced | Spliced | Unspliced | Spliced | |||

| MPMV | 10.0 | 69.2 (1.0)g | 163.7 (2.4) | 2.4 | 33.3 (1.0) | 471.2 (14.1) | 14.1 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| MPMV ΔRU5 | <MD | 100.0 (1.4) | 62.2 (0.9) | 0.6 | 35.7 (1.1) | 55.7 (1.7) | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | <MDh |

Transfected 293 cells were analyzed for Gag production and gag RNA expression.

RNA was extracted 48 h posttransfection, treated with DNase, subjected to RPA with HIV-1 5′ UTR and gapdh probes, and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. The data are standardized to gapdh RNA level and cotransfected Luc values.

SE, splicing efficiency. Ratio of spliced RNA to unspliced RNA.

CA, cytoplasmic accumulation. Ratio of cytoplasmic RNA to nuclear RNA.

CE, cytoplasmic expression. Ratio of Gag protein to unspliced cytoplasmic RNA.

Cell-associated Gag levels in nanograms per milliliter normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

Amounts in parentheses signify RNA level relative to unspliced MPMV gag reporter RNA level.

<MD, less than minimum detectable.

MPMV RU5 augments cytoplasmic expression of nonviral luc RNA.

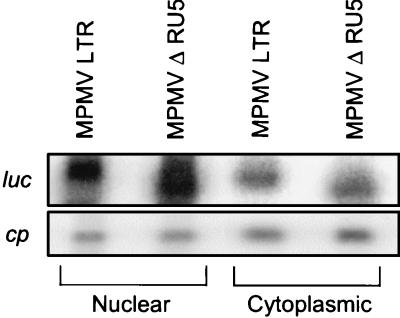

We used luc reporter RNA to evaluate whether or not MPMV RU5 also augments expression of a nonviral reporter RNA. The MPMV 5′ LTR was inserted upstream of the luc open reading frame of pGL3, which is a constitutively expressed, intronless cDNA. Similar to results with pGL3 (data not shown), MPMV ΔRU5 luc reporter RNA exhibited robust and constitutive expression independently of any retroviral posttranscriptional control element (Table 3). The addition of MPMV RU5 increased Luc production three- to fourfold in 293 cells and also increased Luc production in COS cells (data not shown). As expected, robust levels of cytoplasmic luc RNA are detected from MPMV ΔRU5 by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Addition of RU5 had minimal effect on the steady-state level of luc RNA in the nucleus or the cytoplasm. Therefore, the increase in Luc production in response to RU5 is not attributable to increased steady-state levels or cytoplasmic accumulation of luc reporter RNA. These results indicate that RU5 exerts a positive effect on the cytoplasmic expression of both nonviral luc and HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNAs. Notably, the magnitude-positive effect of RU5 is 25- to 30-fold greater in HIV-1 gag-pol RNA. We postulate that this significant difference is attributable to structural differences between the RNAs. Luc protein is produced from a cDNA that lacks a complex 5′ UTR, intronic and instability sequences that are present in HIV-1 gag-pol RNA. In subsequent experiments we sought to directly address the role of SNV RU5 in polysome loading. We chose to study the luc reporter RNA in order to evaluate translational efficiency independently of the complicating variables presented in HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA.

TABLE 3.

Analysis of nonviral luc RNAa

| Expt no. | Plasmid | Amt of Lucc | Amt in PhosphorImager units (105)b of:

|

CAd | CEe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear RNA | Cytoplasmic RNA | |||||

| 1 | MPMV ΔRU5 luc | 19.3 | 109.8 (1.0)f | 41.4 (1.0) | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| MPMV LTR luc | 57.8 | 96.4 (0.8) | 52.2 (1.2) | 0.5 | 1.1 | |

| 2 | MPMV ΔRU5 luc | 12.9 | NDg | 46.9 (1.0) | ND | 0.3 |

| MPMV LTR luc | 55.5 | ND | 30.7 (0.6) | ND | 1.8 | |

Duplicate transfections of 293 cells were analyzed for Luc production and luc RNA expression.

RNA was extracted 48 h posttransfection, treated with DNase, subjected to Northern blot analysis with luc and cp probes, and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. The data are standardized to cp RNA level.

Cell-associated Luc level (relative light units, 103) normalized to cotransfected Ren values.

CA, cytoplasmic accumulation. Ratio of cytoplasmic RNA to nuclear RNA.

CE, cytoplasmic expression. Ratio of Luc protein to unspliced cytoplasmic RNA.

Amounts in parentheses signify RNA level relative to MPMV ΔRU5 luc reporter RNA level.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA from transfected 293 cells reveals that MPMV RU5 has minimal effect on the steady-state luc RNA level or cytoplasmic accumulation. Forty-eight hours posttransfection RNAs were isolated and treated with DNase. Ten-microgram aliquots were subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel with 5% formaldehyde, transferred to a Duralon-UV membrane, and hybridized to α-32P-labeled DNA probes complementary to luc and cp. The blots were subjected to PhosphorImager analysis. Labels indicate the reporter plasmid and RNA fraction.

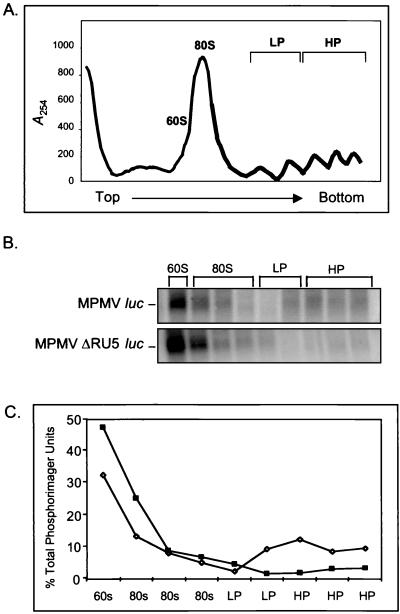

MPMV RU5 augments polyribosome association of luc reporter RNA.

We performed ribosomal profile analysis to test the hypothesis that MPMV RU5 increased cytoplasmic expression of luc RNA by augmentation of translational efficiency. As expected, similar ribosomal profiles were observed from 293 cells transfected with MPMV or MPMV ΔRU5 luc reporter plasmids or mock transfected (Fig. 5A, representative profile from two replicate experiments). RNA was harvested from fractionated 15 to 45% sucrose gradients and was subjected to Northern blot analysis with a uniformly labeled antisense luc RNA probe. As expected, luc RNA was not detected in the fractions from mock-transfected cells (data not shown). The cytoplasm of cells transfected with the MPMV or MPMV ΔRU5 luc reporter plasmids exhibited luc transcripts in several fractions (Fig. 5B). PhosphorImager analysis was used to quantify the abundance of luc transcript across the gradients (Fig. 5C). In agreement with the results of Fig. 4, MPMV RU5 did not significantly increase the overall abundance of luc RNA in the cytoplasm. The combined luc RNA signal across the entire cytoplasmic gradient for MPMV RU5 was 6 × 106 U and for MPMV ΔRU5 was 8 × 106 U. In the absence of RU5, low but detectable levels of luc RNA are observed on light and heavy polyribosomes, consistent with constitutive expression of Luc protein. The presence of RU5 increased luc RNA levels on the light and heavy polyribosome fractions, indicating increased translational efficiency. MPMV RU5 increased this signal intensity by 4.4-fold, which is proportional to the increase observed in Luc protein production. The results demonstrate that MPMV RU5 increased Luc production by stimulation of ribosome loading onto luc mRNA.

FIG. 5.

Northern blot of luc reporter RNAs across the ribosomal profile reveals that MPMV RU5 redistributes cytoplasmic RNA to the light and heavy polyribosomes (LP and HP). (A) Representative ribosomal profile of transfected 293 cells. Cytoplasmic extracts were subjected to sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, fractionation, and spectrophotometry (A254). Positions of the 60S ribosomal subunit, 80S monosomes, light polyribosomes (two to three ribosomes), and heavy polyribosomes (four to six ribosomes) are indicated. The arrow indicates the direction of the gradient. (B) Each fraction was subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel with 5% formaldehyde, transferred to a Duralon-UV membrane, and hybridized to a α-32P-labeled RNA probe complementary to luc. RNA levels were quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. Labels indicate the reporter plasmid and the fraction of the ribosomal profile. (C) Shown is quantification of luc RNA levels across the ribosomal profile, which were tallied and expressed as percentages of total PhosphorImager units. ⋄, MPMV luc; ▪, MPMV ΔRU5 luc.

DISCUSSION

MPMV RU5 facilitates Rev/RRE-independent cytoplasmic expression of HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA.

Results of our transient transfection assays indicate that the RU5 region of the MPMV 5′ LTR functions in a cell-type-dependent manner and independently of INS-1 to facilitate Rev/RRE-independent expression of intron-containing HIV-1 gag-pol RNA. Similar to SNV RU5 (7) and HFV R (37), MPMV RU5 has little effect on cytoplasmic accumulation of gag RNA but is absolutely necessary for detectable Gag protein production.

MPMV RU5 redistributes cytoplasmic luc reporter RNA with polyribosomes.

MPMV RU5 also exerts a positive effect on cytoplasmic expression of nonviral luc reporter RNA. Similar to the trends in HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA, MPMV RU5 has little effect on the steady-state level or cytoplasmic accumulation of luc mRNA but increases the production of Luc protein. Reminiscent of previous results with SNV RU5 (36), we observe that MPMV RU5 increases polyribosome loading of luc reporter RNA by 4.4-fold. The results imply that at least one function of MPMV RU5 is to increase translation initiation. Ribosome sedimentation analysis has previously verified that SNV RU5 also increases ribosome association of HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA (7). We expect that ribosome sedimentation experiments with MPMV RU5 and HFV R will reveal a comparable result. The observation that MPMV RU5 produces a significantly greater effect in HIV-1 gag-pol RNA than in luc RNA (25- to 30-fold) implies that RU5 exerts functional activities in addition to increasing translational efficiency.

5′ RNA termini of divergent retroviruses facilitate cytoplasmic expression.

The 5′-terminal PCEs identified share a number of similarities in addition to their absolute requirement for Gag production from unspliced viral RNA. First, deletion of MPMV or SNV RU5 (7) does not reduce steady-state level or cytoplasmic accumulation of intron-containing reporter RNA. A speculative explanation for this intriguing observation is that RNP components are recruited by U3 promoter elements that facilitate cytoplasmic accumulation of the unspliced viral RNA. Previous identification of promoter-dependent recruitment of RNA-splicing (10) and polyadenylation factors (14), SF2/ASF and CPSF, respectively, validates the prediction that RNP factors recruited by the promoter to the pre-mRNA can modulate posttranscriptional steps of gene expression.

Another similarity between these PCEs is that MPMV RU5, SNV RU5, and HFV R increase RNA splicing efficiency, which implies that PCE activity involves recognition of splicing signals. Our reporter gene assays with luc cDNA indicate that intron recognition is not necessary for translational enhancement by MPMV or SNV RU5. The significantly greater level of MPMV and SNV RU5 activity in HIV-1 gag-pol RNA is expected to be attributable to overcoming the repressive effect of lack of intron removal on posttranscriptional gene expression. Functional linkage between the process of mammalian pre-mRNA splicing and translational efficiency has been observed in the Xenopus oocyte system, wherein the translational efficiency of reporter RNA is potently affected by the process of splicing of the β-globin intron (30).

The functional activity of these PCEs is distinct from the posttranscriptional activity identified in the R region of MuLV. While MPMV and SNV RU5 and HFV R exert little effect on the level of cytoplasmic unspliced RNA, deletion of MuLV R reduces the level of cytoplasmic unspliced RNA by a factor of 5 (43). Secondly, the positive effect on RNA splicing efficiency is not observed for MuLV R; deletion or mutation of MuLV R produces little change in the level of spliced RNA. Furthermore, in unpublished experiments, we observed that MuLV RU5 is not sufficient to confer Rev/RRE-independent expression of the HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA (S. Hull and K. Boris-Lawrie, unpublished findings). These results indicate that the functional activity of the MPMV, SNV, and HFV PCEs is not conserved in MuLV. We speculate that the 5′ PCE activity in these three divergent retroviruses provides a shared mechanism to overcome barriers to efficient cytoplasmic expression of unspliced viral RNA. We propose that MPMV PCE recruits particular RNP components to the pre-mRNA that programs their functional interaction with ribosomes and efficient cytoplasmic expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick Green, Tiffiney Roberts, and Melinda Butsch for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Ohio Division, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R29A140851), and the National Cancer Institute (P30CA16058).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkowitz, R., J. Fisher, and S. P. Goff. 1996. RNA packaging. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214:177-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boris-Lawrie, K., T. M. Roberts, and S. Hull. 2001. Retroviral RNA elements integrate components of post-transcriptional gene expression. Life Sci. 69:2697-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boris-Lawrie, K., and H. M. Temin. 1995. Genetically simpler bovine leukemia virus derivatives can replicate independently of Tax and Rex. J. Virol. 69:1920-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun, I. C., A. Herold, M. Rode, E. Conti, and E. Izaurralde. 2001. Overexpression of TAP/p15 heterodimers bypasses nuclear retention and stimulates nuclear mRNA export. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20536-20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray, M., S. Prasad, J. W. Dubay, E. Hunter, K. T. Jeang, D. Rekosh, and M. L. Hammarskjold. 1994. A small element from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication Rev-independent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1256-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butsch, M., and K. Boris-Lawrie. 2002. Destiny of unspliced retroviral RNA: ribosome and/or virion? J. Virol. 76:3089-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butsch, M., S. Hull, Y. Wang, T. M. Roberts, and K. Boris-Lawrie. 1999. The 5′ RNA terminus of spleen necrosis virus contains a novel posttranscriptional control element that facilitates human immunodeficiency virus Rev/RRE-independent Gag production. J. Virol. 73:4847-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cochrane, A. W., C. H. Chen, and C. A. Rosen. 1990. Specific interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus Rev protein with a structured region in the env mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:1198-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochrane, A. W., K. S. Jones, S. Beidas, P. J. Dillon, A. M. Skalka, and C. A. Rosen. 1991. Identification and characterization of intragenic sequences which repress human immunodeficiency virus structural gene expression. J. Virol. 65:5305-5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer, P., J. F. Caceres, D. Cazalla, S. Kadener, A. F. Muro, F. E. Baralle, and A. R. Kornblihtt. 1999. Coupling of transcription with alternative splicing: RNA pol II promoters modulate SF2/ASF and 9G8 effects on an exonic splicing enhancer. Mol. Cell 4:251-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen, B. R. 2000. Connections between the processing and nuclear export of mRNA: evidence for an export license? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullen, B. R. 2000. Nuclear RNA export pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4181-4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dangel, A. W., S. Hull, T. M. Roberts, and K. Boris-Lawrie. 2002. Nuclear interactions are necessary for translational enhancement by spleen necrosis virus RU5. J. Virol. 76:3292-3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dantonel, J. C., K. G. Murthy, J. L. Manley, and L. Tora. 1997. Transcription factor TFIID recruits factor CPSF for formation of 3′ end of mRNA. Nature 389:399-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst, R. K., M. Bray, D. Rekosh, and M. L. Hammarskjold. 1997. A structured retroviral RNA element that mediates nucleocytoplasmic export of intron-containing RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:135-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst, R. K., M. Bray, D. Rekosh, and M. L. Hammarskjold. 1997. Secondary structure and mutational analysis of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus RNA constitutive transport element. RNA 3:210-222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fornerod, M., M. Ohno, M. Yoshida, and I. W. Mattaj. 1997. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell 90:1051-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geballe, A. P., and M. K. Gray. 1992. Variable inhibition of cell-free translation by HIV-1 transcript leader sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:4291-4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grens, A., and I. E. Scheffler. 1990. The 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of ornithine decarboxylase mRNA affect the translational efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 265:11810-11816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadzopoulou-Cladaras, M., B. K. Felber, C. Cladaras, A. Athanassopoulos, A. Tse, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1989. The rev (trs/art) protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affects viral mRNA and protein expression via a cis-acting sequence in the env region. J. Virol. 63:1265-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heaphy, S., C. Dingwall, I. Ernberg, M. J. Gait, S. M. Green, J. Karn, A. D. Lowe, M. Singh, and M. A. Skinner. 1990. HIV-1 regulator of virion expression (Rev) protein binds to an RNA stem-loop structure located within the Rev response element region. Cell 60:685-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacampo, S., and A. Cochrane. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev function requires continued synthesis of its target mRNA. J. Virol. 70:8332-8339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang, Y., and B. R. Cullen. 1999. The human Tap protein is a nuclear mRNA export factor that contains novel RNA-binding and nucleocytoplasmic transport sequences. Genes Dev. 13:1126-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Hir, H., M. J. Moore, and L. E. Maquat. 2000. Pre-mRNA splicing alters mRNP composition: evidence for stable association of proteins at exon-exon junctions. Genes Dev. 14:1098-1108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levesque, L., B. Guzik, T. Guan, J. Coyle, B. E. Black, D. Rekosh, M. L. Hammarskjold, and B. M. Paschal. 2001. RNA export mediated by tap involves NXT1-dependent interactions with the nuclear pore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44953-44962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo, M. J., and R. Reed. 1999. Splicing is required for rapid and efficient mRNA export in metazoans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14937-14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maldarelli, F., M. A. Martin, and K. Strebel. 1991. Identification of posttranscriptionally active inhibitory sequences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA: novel level of gene regulation. J. Virol. 65:5732-5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malim, M. H., J. Hauber, S. Y. Le, J. V. Maizel, and B. R. Cullen. 1989. The HIV-1 rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNA. Nature 338:254-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzella, J. M., and P. J. Blackshear. 1990. Regulation of rat ornithine decarboxylase mRNA translation by its 5′-untranslated region. J. Biol. Chem. 265:11817-11822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto, K., K. M. Wassarman, and A. P. Wolffe. 1998. Nuclear history of a pre-mRNA determines the translational activity of cytoplasmic mRNA. EMBO J. 17:2107-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miele, G., A. Mouland, G. P. Harrison, E. Cohen, and A. M. Lever. 1996. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 5′ packaging signal structure affects translation but does not function as an internal ribosome entry site structure. J. Virol. 70:944-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neville, M., F. Stutz, L. Lee, L. I. Davis, and M. Rosbash. 1997. The importin-beta family member Crm1p bridges the interaction between Rev and the nuclear pore complex during nuclear export. Curr. Biol. 7:767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkin, N. T., E. A. Cohen, A. Darveau, C. Rosen, W. Haseltine, and N. Sonenberg. 1988. Mutational analysis of the 5′ non-coding region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects of secondary structure on translation. EMBO J. 7:2831-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelletier, J., and N. Sonenberg. 1985. Insertion mutagenesis to increase secondary structure within the 5′ noncoding region of a eukaryotic mRNA reduces translational efficiency. Cell 40:515-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rein, A. 1994. Retroviral RNA packaging: a review. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 9:513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts, T. M., and K. Boris-Lawrie. 2000. The 5′ RNA terminus of spleen necrosis virus stimulates translation of nonviral mRNA. J. Virol. 74:8111-8118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell, R. A., Y. Zeng, O. Erlwein, B. R. Cullen, and M. O. McClure. 2001. The R region found in the human foamy virus long terminal repeat is critical for both Gag and Pol protein expression. J. Virol. 75:6817-6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saavedra, C., B. Felber, and E. Izaurralde. 1997. The simian retrovirus-1 constitutive transport element, unlike the HIV-1 RRE, uses factors required for cellular mRNA export. Curr. Biol. 7:619-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoenberg, D. R., and K. S. Cunningham. 1999. Characterization of mRNA endonucleases. Methods 17:60-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz, S., M. Campbell, G. Nasioulas, J. Harrison, B. K. Felber, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1992. Mutational inactivation of an inhibitory sequence in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in Rev-independent gag expression. J. Virol. 66:7176-7182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz, S., B. K. Felber, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1992. Distinct RNA sequences in the gag region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 decrease RNA stability and inhibit expression in the absence of Rev protein. J. Virol. 66:150-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabernero, C., A. S. Zolotukhin, A. Valentin, G. N. Pavlakis, and B. K. Felber. 1996. The posttranscriptional control element of the simian retrovirus type 1 forms an extensive RNA secondary structure necessary for its function. J. Virol. 70:5998-6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trubetskoy, A. M., S. A. Okenquist, and J. Lenz. 1999. R region sequences in the long terminal repeat of a murine retrovirus specifically increase expression of unspliced RNAs. J. Virol. 73:3477-3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiegand, H. L., G. A. Coburn, Y. Zeng, Y. Kang, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 2002. Formation of Tap/NXT1 heterodimers activates Tap-dependent nuclear mRNA export by enhancing recruitment to nuclear pore complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:245-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wodrich, H., A. Schambach, and H. G. Krausslich. 2000. Multiple copies of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive RNA transport element lead to enhanced HIV-1 Gag expression in a context-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:901-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zapp, M. L., and M. R. Green. 1989. Sequence-specific RNA binding by the HIV-1 Rev protein. Nature 342:714-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]