Abstract

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors have been shown to direct stable gene transfer and expression in hepatocytes, which makes them attractive tools for treatment of inherited disorders such as hemophilia B. While substantial levels of coagulation factor IX (F.IX) have been achieved using AAV serotype 2 vectors, use of a serotype 5 vector further improves transduction efficiency and levels of F.IX transgene expression by 3- to 10-fold. In addition, the AAV-5 vector transduces a higher proportion of hepatocytes (∼15%). The subpopulations of hepatocytes transduced with either vector widely overlap, with the AAV-5 vector transducing additional hepatocytes and showing a wider area of transgene expression throughout the liver parenchyma.

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors are derived from a replication-deficient member of the parvovirus family with a small (∼4.7-kb) single-stranded DNA genome. AAV vectors do not contain viral coding sequences and have been shown to efficiently transfer genes to nondividing target cells, such as hepatocytes, muscle fibers, neurons, and photoreceptors (1, 15, 16, 21). An excellent safety profile combined with reduced potential for activation of inflammatory or cellular immune responses has made this vector system attractive for clinical application and treatment of genetic disorders. Successful preclinical studies led to the initiation of phase I clinical trials based on muscle- or liver-directed gene transfer of an AAV vector expressing coagulation factor IX (F.IX) in patients with severe hemophilia B (F.IX deficiency) (8; H. Nakai, K. Ohashi, V. R. Arruda, A. McClelland, L. B. Couto, L. Meuse, T. Storm, M. D. Dake, C. S. Manno, B. Glader, K. A. High, and M. A. Kay, abstract from the American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting 2000, Blood 96(Suppl.):798a-799a, 2000). In a recent study, it was shown that infusion of comparatively low doses of an AAV-F.IX vector (1012 vector genomes [vg]/kg of body weight) into the portal circulation can result in sustained F.IX expression at levels of 5 to 12% of normal (and therefore nearly complete correction of the hemophilia B phenotype) in a large-animal model (10). Furthermore, hepatocyte-derived expression was associated with reduced likelihood of antibody formation against the transgene product (7, 10).

There are six described serotypes of AAV. The above-described studies have been carried out with the most extensively studied serotype, 2. Vectors of the other serotypes can be efficiently produced by cross-packaging of AAV-2 vector in the capsid of an alternate serotype (14). Recent experiments with AAV-1 and AAV-5 in skeletal muscle demonstrated that a particular combination of serotype and target tissue may increase levels of transgene expression due to the tropism of a particular capsid (5, 20). A marked increase in transduction efficiency of muscle fibers by use of AAV-1 may represent the most striking example of these observations (3). Rabinowitz et al. have shown that the relative efficiencies of gene transfer for the six known AAV serotypes differ, depending on the target cell type (14).

AAV-5 vector directs higher levels of transgene expression than AAV-2 in liver-directed gene transfer.

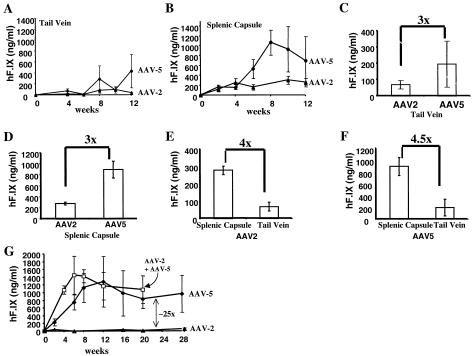

We produced AAV-2 and AAV-5 vectors by triple transfection of HEK-293 cells with (i) a vector plasmid containing an expression cassette for the human F.IX (hF.IX) cDNA (under transcriptional control of the human elongation factor-1α [EF1α] promoter) flanked by AAV-2 inverted terminal repeats, (ii) an adenoviral helper plasmid, and (iii) an AAV helper plasmid encoding AAV-2 rep functions and either AAV-2 or AAV-5 capsid genes. Both vectors were purified by repeated CsCl gradient centrifugation and yielded >1013 vg/ml as determined by quantitative slot blot hybridization. AAV-EF1α-hF.IX vectors were injected into the splenic capsule (for efficient delivery to the portal circulation) or into the tail vein of male C57BL/6 mice (4 to 6 weeks old; n = 4 per vector and route). Mice that received AAV-2 vector via splenic capsule injection reached a plateau of systemic hF.IX expression of 200 to 300 ng/ml of plasma by 4 weeks after gene transfer (Fig. 1B). These levels were identical to previously published results with the same dose of this vector administered directly into the portal vein of C57BL/6 mice (11). Expression levels from the AAV-5 vector were similar during the 1st month after vector administration but subsequently increased further to levels on average threefold higher (400 to 1,000 ng/ml of plasma, weeks 6 to 12) than those obtained with the AAV-2 vector (Fig. 1B and D). Expression levels were four- to fivefold lower following intravenous administration for either vector than with the splenic capsule route (Fig. 1A, C, E, and F). These data are consistent with previous findings by others demonstrating reduced efficacy for AAV-2 vector administration from a peripheral vein compared with that from the portal vein (12).

FIG. 1.

Systemic levels of transgene expression following liver-directed gene transfer with AAV vectors. Plasma levels of hF.IX (as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay specific for hF.IX [18]) as a function of time after AAV-EF1α-hF.IX vector (1011 vg; n = 4 per vector and route) was injected into the tail vein (A) or splenic capsule (B) of C57BL/6 mice. Data points are average with vertical bars indicating standard deviation. Data for animals transduced with the AAV-2 vector are shown as triangles; data from the AAV-5 vector are shown as diamonds. (C to F) Expression levels averaged for time points for weeks 6 to 12 are shown in bar graphs for comparison of expression from AAV-2 and AAV-5 after tail vein injection (C) or splenic capsule injection (D), as well as for comparison of expression from AAV-2 (E) or AAV-5 (F) vector depending on the route of administration. (G) Levels in plasma of hF.IX as a function of time after injection of AAV-EF1α-hF.IX vector (2.5 × 1011 vg) into the tail vein of C57BL/6 mice (triangles, AAV-2 vector [n = 4]; diamonds, AAV-5 [n = 8]). Open squares represent a cohort of mice (n = 6) that received tail vein injection of a mix of AAV2- and AAV5-EF1α-hF.IX vectors (2.5 × 1011 vg/vector).

Improved expression levels from the AAV-5 vector are achieved by increased proportion of transduced hepatocytes.

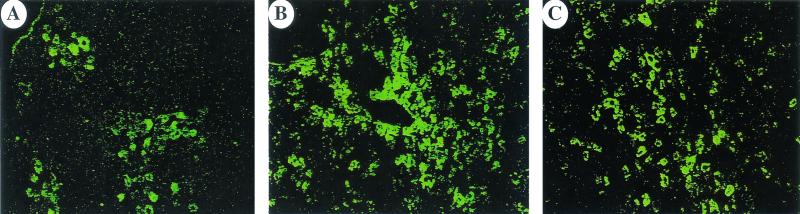

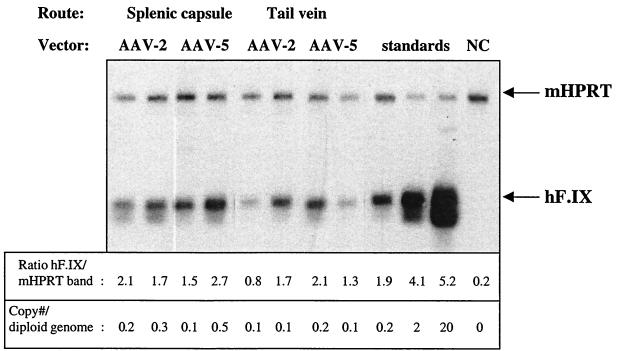

Previous experiments by Miao et al. have shown that stable AAV-2-mediated gene transfer to liver is limited to ∼5% of hepatocytes (9). Consistent with these findings, immunohistochemical analysis of liver cross sections from animals sacrificed 3 months after gene transfer (splenic capsule injections) revealed hF.IX transgene expression in 5.4% ± 4% of hepatocytes of AAV-2-transduced livers (examination of sections from two or three hepatic lobes per animal; n = 3 per vector, image analysis of random fields as described by Nakai et al. [11]). In contrast, 14.8% ± 5.4% of hepatocytes stained positive for hF.IX in AAV-5-transduced livers (Fig. 2A to C). Thus, the increase in systemic F.IX levels can be correlated with an increase in the proportion of hepatocytes showing productive transduction with the AAV-5 vector. Hepatocytes were the only cell type identified to express the transgene, indicating that change of serotype did not alter the target cell population for AAV-mediated transduction within the liver. Previous reports with AAV-2 vectors localized the AAV genome exclusively to hepatocytes using in situ hybridization or histochemical staining for transgene expression (16). Therefore, AAV tropism is distinct from that of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors, for example, which have been shown to predominantly transduce sinusoidal cells following introduction to the liver (13). It is unclear which step during infection of hepatocytes is limiting for stable transduction with AAV. Miao et al. have shown that only a constantly changing 5% subpopulation of hepatocytes can be transduced with AAV-2 and that transduction is independent of the cell cycle status (9). Data from that study suggest that binding, internalization, and translocation to the nucleus are not limiting steps for transduction, as the vector genome was found initially in a large proportion of hepatocytes. However, only a fraction of these cells retained the vector genome, thereby allowing stable transgene expression. Data collected by Duan et al. on AAV-5-mediated gene transfer to myocytes also suggest a postentry mechanism for enhanced transduction efficiency (5). Our results demonstrate that use of an AAV-5 vector allows us to overcome some of the limitations to in vivo transduction of hepatocytes, thereby allowing transgene expression in a substantially higher proportion of hepatocytes than previously described. There is evidence that AAV-2 vectors have reduced infectivity when purified using CsCl gradients, which could in theory explain lower levels of transduction with AAV-2 (22). However, Miao et al. have shown that portal vein injection of ∼1011 vg of a CsCl-purified AAV-2 vector results in infection of a large number of hepatocytes but in stable transduction of only 5% of hepatocytes. Therefore, it is unlikely that infectivity of the AAV-2 vector is limiting for efficiency of transduction. To the best of our knowledge, transduction of 15% of hepatocytes at these vector doses has not been demonstrated before using an AAV vector, and recent data from others have also demonstrated improved efficacy of hepatic gene transfer with the AAV-5 serotype (L. Wang, T. C. Nichols, M. S. Read, D. A. Bellinger, I. M. Verma, and J. M. Wilson, abstract from the American Society of Gene Therapy Annual Meeting 2002, Mol. Ther. 5:S83, 2002). Interestingly, the AAV-2 vector gave two- to fourfold-higher levels of F.IX expression in vitro than did the AAV-5 vector following transduction of human hepatoma HepG2 cells (data not shown). Taking all these data together, the likeliest conclusion is that use of the AAV-5 capsid protein is responsible for the increase in productive transduction in hepatocytes, thereby resulting in higher levels of transgene expression derived from a larger number of expressing cells. This may be of particular importance for diseases such as familial hypercholesterolemia that may require gene delivery to a larger proportion of cells rather than particular levels of systemic expression for successful treatment (4). With the AAV-2 vector, hepatocytes positive for hF.IX expression were mostly present in clusters typically found near blood vessels (Fig. 2A; see also reference 11), while there was much more widespread transduction of hepatocytes throughout the liver parenchyma with the AAV-5 vector (Fig. 2B and C). Quantitative PCR using biotinylated primer pairs for multiplex amplification of the hF.IX cDNA (5′-GAA TCA CCA GGC CTC ATC AC-3′ and 5′-CGC ATC TGC CAT TCT TAA TGT-3′) and the endogenous HPRT gene (5′-GCT GGT GAA AAG GAC CTC T-3′ and 5′-CAC AGG ACT AGA ACA CCT GC-3′) did not reveal a substantial difference in gene copy number for AAV-2- and AAV-5-transduced livers (3-month time point) but on average showed reduced gene copy numbers for the intravenous route of vector delivery (Fig. 3). Gene copy numbers were similar to those reported for the liver of a hemophilia B dog infused with 3 × 1012 AAV vg/kg via the mesenteric vein for hepatic gene transfer (10).

FIG. 2.

Immunofluorescence staining of AAV-transduced mouse livers. (A to C) Stain for hF.IX (green) using goat anti-hF.IX (Affinity Biologicals) and rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (DAKO Corp.) 3 months after AAV2-EF1α-hF.IX vector administration (6). (A) AAV2-EF1α-hF.IX vector. (B and C) AAV5-EF1α-hF.IX vector. Magnification, ×88.

FIG. 3.

Estimation of vector gene copy number in AAV-transduced livers by quantitative PCR (3 months after vector administration). A 350-bp fragment of the hF.IX cDNA as present in the AAV-EF1α-hF.IX vector was coamplified with a 1.1-kb fragment from the endogenous murine HPRT gene using biotinylated primers (20 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, separated on a 2% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and visualized with the Southern light detection system from Applied Biosystems. Template for PCR was as follows: 100 ng of genomic DNA extracted from several random pieces of liver and subsequently combined for each individual animal. Each sample column represents an individual animal. standards, linearized plasmid pAAV-EF1α-hF.IX (0.01, 0.1, or 1 pg) mixed with 100 ng of genomic mouse DNA (extracted from untransduced animal); NC, negative control (template, genomic DNA from untransduced animal). Bands were analyzed by densitometric scanning, and intensities were quantitated with NIH Image 6.16 software. Shown is one representative blot. Ratios of band intensities (hF.IX band/mAAT band) are for the blot shown. Gene copy number estimates are average for two experiments.

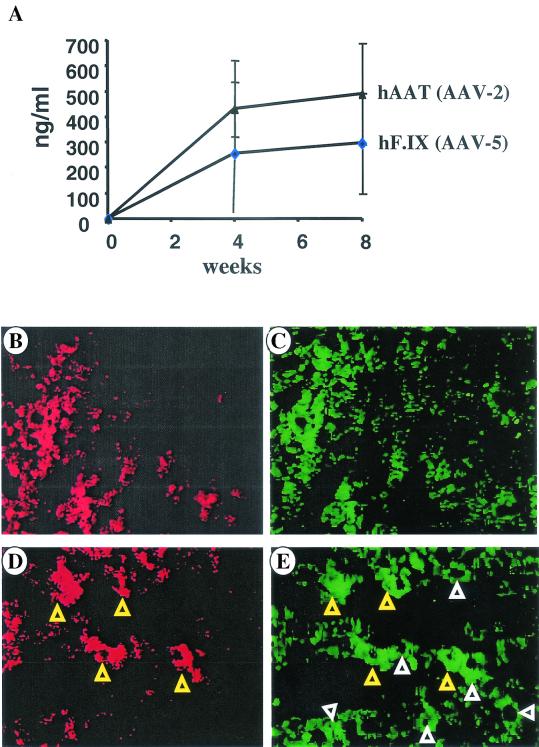

Cotransduction of hepatocytes by AAV-2 and AAV-5 vectors demonstrates overlap in populations of transduced cells.

Since the proportion of hepatocytes transduced with the two different AAV serotypes differed by approximately threefold, we wanted to test whether these represented distinct or overlapping populations of cells. C57BL/6 mice (n = 4) received splenic capsule injections of an equimolar mix of the AAV5-EF1α-hF.IX vector and an AAV-2 vector expressing human α1-antitrypsin (hAAT) from an albumin promoter (AAV2-alb-hAAT [1011 vg/vector]). All mice expressed both transgenes as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on plasma samples for 1- and 2-month time points (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, mice were sacrificed and analyzed by immunofluorescence costaining for hF.IX and hAAT transgene products. These experiments show overlap in the areas positive for both transgene products with more widespread positivity for hF.IX (i.e., the gene delivered with the AAV-5 vector [Fig. 4B and C]). Viewed at higher magnification, hepatocytes positive for hAAT (i.e., AAV-2-transduced cells) were also positive for hF.IX, indicating cotransduction of these cells with both vectors (Fig. 4D and E). Adjacent to hAAT-positive cells are hepatocytes positive for hF.IX but negative for hAAT. In summary, AAV-2 and AAV-5 vectors transduce widely overlapping populations (>90%) of hepatocytes with the AAV-5 vector transducing additional hepatocytes. Coadministration of these vectors may therefore not have an additive effect for the percentage of cells transduced. However, based on observations by Miao et al., namely, that the population of hepatocytes transduced with the AAV vector is changing over time, serial injections of the two different serotypes as part of a readministration protocol should have an additive effect on gene transfer and expression (9).

FIG. 4.

(A) Levels in plasma of hF.IX (diamonds) and hAAT (triangles) as a function of time after injection of a mix of AAV5-EF1α-hF.IX and AAV2-alb-hAAT vector (1011 vg/vector) into the splenic capsule of C57BL/6 mice (n = 4). (B to E) Simultaneous staining for hF.IX (green stain in panels C and E, goat anti-hF.IX conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate; Affinity Biologicals) and hAAT (red stain in panels B and D, rabbit anti-hAAT σ and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to rhodamine [Chemicon Corp.]) expressed by AAV2-alb-hAAT/AAV5-EF1α-hF.IX-cotransduced livers 2 months after vector administration. Yellow triangles in panels D and E indicate hepatocytes transduced with both vectors; white triangles indicate hepatocytes transduced with AAV-5 only. Original magnifications: ×100 (B and C) and ×400 (D and E).

High levels of F.IX expression after intravenous administration of the AAV-5 vector.

One aspect that makes muscle-directed gene transfer with an AAV vector attractive is the minimal invasiveness of the procedure, as opposed to a surgical procedure required to gain access to the portal vein or an alternative blood vessel for efficient delivery to the hepatic circulation. We rationalized that increased hepatic gene transfer with the AAV-5 vector would partially compensate for the loss of efficacy associated with infusion of vector via a peripheral vein. In a follow-up experiment, we infused 2.5 × 1012 vg of the AAV-EF1α-hF.IX vector into the tail vein of C57BL/6 mice (n = 4 for the AAV-2 vector and n = 6 for the AAV-5 vector [Fig. 1G]). In this experiment, expression levels in AAV-5-transduced mice were on average 25-fold higher than those obtained with the AAV-2 vector and comparable to those obtained with 1011 vg of the AAV-5 vector injected into the splenic capsule (see above). These data illustrate that it is possible to achieve high levels of F.IX expression (∼20% of normal hF.IX levels and thus well within the therapeutic range) by intravenous infusion of an AAV vector following optimization of serotype and dose. Coadministration of AAV2- and AAV5-EF1α-hF.IX vector (2.5 × 1011 vg/vector) into the tail vein of C57BL/6 mice gave levels of hF.IX expression similar to those observed with AAV-5 vector alone (Fig. 1G). Results from this experiment and from the cotransduction experiment outlined above (Fig. 3A and C to F) suggest little competition between AAV-2 and AAV-5 vectors for in vivo transduction, thus further supporting the hypothesis that these two serotypes utilize distinct receptors and entry pathways for gene transfer (17, 19).

It is likely that using a stronger enhancer/promoter combination will lower vector doses required for therapeutic transgene expression following vector injection into a peripheral vein. In our experience, the hepatocyte-specific combination of ApoE enhancer and hAAT promoter directs at least fivefold-higher levels of F.IX expression for a given vector dose than the EF1α promoter (10; unpublished results). Prior to clinical application, it will be helpful to evaluate these points in large-animal models such as hemophilia B dogs in order to better model volumes of distribution and sizes of blood vessels of a human patient. A recent report suggests that increased efficacy of hepatic gene transfer by an AAV-5 vector, as demonstrated here for mice, is also observed in the canine model (Wang et al., Mol. Ther. 5:S83, 1996). Furthermore, it will be necessary to assess the risk of transduction of gonadal germ cells with AAV-5 prior to translation to the clinic (2).

In summary, AAV-5-mediated gene transfer to the liver directs higher levels of transgene expression as the result of an increased proportion of transduced hepatocytes than does the traditional AAV-2 vector. These data further encourage development of the AAV vector system as a delivery vehicle for hepatic gene transfer.

Acknowledgments

F.M. and J.S. contributed equally to this work.

We thank Yu Qin Wang and Wei Zhao for technical assistance.

R.W.H. is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Hemophilia Foundation. This work was supported by NIH grants P01 HL64190 and U01 HL66948 to K.A.H. and R01 HL69051-01 ?l2;6qto W.X.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acland, G. M., G. D. Aguirre, J. Ray, Q. Zhang, T. S. Aleman, A. V. Cideciyan, S. E. Pearce-Kelling, V. Anand, Y. Zeng, A. M. Maguire, S. G. Jacobson, W. W. Hauswirth, and J. Bennett. 2001. Gene therapy restores vision in a canine model of childhood blindness. Nat. Genet. 28:92-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arruda, V. R., P. A. Fields, R. Milner, L. Wainwright, M. P. De Miguel, P. J. Donovan, R. W. Herzog, T. C. Nichols, J. A. Biegel, M. Razavi, M. Dake, D. Huff, A. W. Flake, L. Couto, M. A. Kay, and K. A. High. 2001. Lack of germline transmission of vector sequences following systemic administration of recombinant AAV-2 vector in males. Mol. Ther. 4:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao, H., Y. Liu, J. Rabinowitz, C. Li, R. J. Samulski, and C. E. Walsh. 2000. Several log increase in therapeutic transgene delivery by distinct adeno-associated viral serotype vectors. Mol. Ther. 2:619-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, S. J., D. J. Rader, J. Tazelaar, M. Kawashiri, G. Gao, and J. M. Wilson. 2000. Prolonged correction of hyperlipidemia in mice with familial hypercholesterolemia using an adeno-associated viral vector expressing very-low-density lipoprotein receptor. Mol. Ther. 2:256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan, D., Z. Yan, Y. Yue, W. Ding, and J. F. Engelhardt. 2001. Enhancement of muscle gene delivery with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus type 5 correlates with myoblast differentiation. J. Virol. 75:7662-7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herzog, R. W., J. N. Hagstrom, Z.-H. Kung, S. J. Tai, J. M. Wilson, K. J. Fisher, and K. A. High. 1997. Stable gene transfer and expression of human blood coagulation factor IX after intramuscular injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5804-5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzog, R. W., J. D. Mount, V. R. Arruda, K. A. High, and C. D. J. Lothrop. 2001. Muscle-directed gene transfer and transient immune suppression result in sustained partial correction of canine hemophilia B caused by a null mutation. Mol. Ther. 4:192-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay, M. A., C. S. Manno, M. V. Ragni, P. J. Larson, L. B. Couto, A. McClelland, B. Glader, A. J. Chew, S. J. Tai, R. W. Herzog, V. Arruda, F. Johnson, C. Scallan, E. Skarsgard, A. W. Flake, and K. A. High. 2000. Evidence for gene transfer and expression of factor IX in haemophilia B patients treated with an AAV vector. Nat. Genet. 24:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miao, C. H., H. Nakai, A. R. Thompson, T. A. Storm, W. Chiu, R. O. Snyder, and M. A. Kay. 2000. Nonrandom transduction of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in mouse hepatocytes in vivo: cell cycling does not influence hepatocyte transduction. J. Virol. 74:3793-3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mount, J. D., R. W. Herzog, D. M. Tillson, S. A. Goodman, N. Robinson, M. L. McCleland, D. Bellinger, T. C. Nichols, V. R. Arruda, C. D. Lothrop, Jr., and K. A. High. 2002. Sustained phenotypic correction of hemophilia B dogs with a factor IX null mutation by liver-directed gene therapy. Blood 99:2670-2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakai, H., R. Herzog, J. N. Hagstrom, J. Kung, J. Walter, S. Tai, Y. Iwaki, G. Kurtzman, K. Fisher, L. Couto, and K. A. High. 1998. AAV-mediated gene transfer of human blood coagulation factor IX into mouse liver. Blood 91:4600-4607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakai, H., Y. Iwaki, M. A. Kay, and L. B. Couto. 1999. Isolation of recombinant adeno-associated virus vector-cellular DNA junctions from mouse liver. J. Virol. 73:5438-5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeifer, A., T. Kessler, M. Yang, E. Baranov, N. Kootstra, D. A. Cheresh, R. M. Hoffman, and I. M. Verma. 2001. Transduction of liver cells by lentiviral vectors: analysis in living animals by fluorescence imaging. Mol. Ther. 3:319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinowitz, J. E., F. Rolling, C. Li, H. Conrath, W. Xiao, X. Xiao, and R. J. Samulski. 2002. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 76:791-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skorupa, A. F., K. J. Fisher, J. M. Wilson, M. K. Parente, and J. H. Wolfe. 1999. Sustained production of beta-glucuronidase from localized sites after AAV vector gene transfer results in widespread distribution of enzyme and reversal of lysosomal storage lesions in a large volume of brain in mucopolysaccharidosis VII mice. Exp. Neurol. 160:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder, R. O., C. H. Miao, G. A. Patijn, S. K. Spratt, O. Danos, D. Nagy, A. M. Gown, B. Winther, L. Meuse, L. K. Cohen, A. R. Thompson, and M. A. Kay. 1997. Persistent and therapeutic concentrations of human factor IX in mice after hepatic gene transfer of recombinant AAV vectors. Nat. Genet. 16:270-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Summerford, C., and R. J. Samulski. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 72:1438-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walter, J., Q. You, J. N. Hagstrom, M. Sands, and K. A. High. 1996. Successful expression of human factor IX following repeat administration of adenoviral vector in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3056-3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters, R. W., S. M. Yi, S. Keshavjee, K. E. Brown, M. J. Welsh, J. A. Chiorini, and J. Zabner. 2001. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20610-20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao, W., N. Chirmule, S. C. Berta, B. McCullough, G. Gao, and J. M. Wilson. 1999. Gene therapy vectors based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J. Virol. 73:3994-4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao, X., J. Li, and R. J. Samulski. 1996. Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J. Virol. 70:8098-8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zolotukhin, S., B. J. Byrne, E. Mason, I. Zolotukhin, M. Potter, K. Chesnut, C. Summerford, R. J. Samulski, and N. Muzyczka. 1999. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 6:973-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]