Abstract

CD4 and the chemokine receptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, serve as receptors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Binding of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein to the chemokine receptors normally requires prior interaction with CD4. Mapping the determinants on gp120 for the low-affinity interaction with CXCR4 has been difficult due to the nonspecific binding of this viral glycoprotein to cell surfaces. Here we examine the binding of a panel of gp120 mutants to paramagnetic proteoliposomes displaying CXCR4 on their surfaces. We show that the gp120 β19 strand and third variable (V3) loop contain residues important for CXCR4 interaction. Basic residues from both elements, as well as a conserved hydrophobic residue at the V3 tip, contribute to CXCR4 binding. Removal of the gp120 V1/V2 variable loops allows the envelope glycoprotein to bind CXCR4 in a CD4-independent manner. These results indicate that although some variable gp120 residues contribute to the specific binding to CCR5 or CXCR4, gp120 elements common to CXCR4- or CCR5-using strains are involved in the interaction with both coreceptors.

The entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) into target cells requires the fusion of the viral and cellular membranes (78). This step allows the core of the virus to be delivered into the cytoplasm of the cell. The fusion process is not fully understood; however, much evidence suggests that it follows multiple steps and involves at least four molecules. First, gp120, the surface envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1, binds CD4, which is the primary receptor for HIV-1 (15, 36). This induces conformational modifications of gp120 that result in the exposure of CD4-induced (CD4i) epitopes (56, 77). Regions of gp120 near these epitopes are responsible for binding a coreceptor belonging to the family of the chemokine receptors (1, 12, 18, 25, 66, 74). Finally, the formation of the CD4/gp120/coreceptor complex is thought to provoke additional conformational changes in gp120. These changes include the exposure of the fusion peptide located at the amino terminus of gp41, the HIV-1 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein, and its insertion into the membrane of the target cell. The subsequent formation of a six-helix bundle involving the membrane-distal and -proximal domains of the gp41 ectodomain then brings the viral and cytoplasmic membranes together and eventually results in membrane fusion (for reviews, see references 10, 17, 59, 62, 73, and 78).

CCR5 and CXCR4 are the two main chemokine receptors that, along with CD4, are used by HIV-1 for entry (1, 12, 16, 18, 25, 66, 74). Macrophage-tropic viruses (referred to herein as R5 viruses) infect macrophages and activated CD4+ T lymphocytes through CCR5 (18, 25) and are responsible for most cases of horizontal and vertical transmission (68, 80). The R5 viruses persist throughout the course of HIV-1 infection. Lymphotropic viruses (X4 viruses) or dual-tropic viruses (R5X4 viruses) (27) emerge later in the course of HIV-1 infection and use CXCR4 as a coreceptor (1, 12). As CXCR4 and CCR5 are found on 80% and 15% of CD4+ T lymphocytes, respectively (28), the shift from CCR5 to CXCR4 usage by HIV-1 is believed to be responsible for the accelerated destruction of CD4+ T lymphocytes preceding the onset of AIDS (57, 63) (for a review, see reference 41).

A number of studies based on the construction of chimeric envelope glycoproteins of X4 and R5 strains have demonstrated that the third hypervariable loop (V3) of gp120 is the primary determinant for cell tropism and coreceptor usage (29, 32, 33, 60), although other domains of gp120 are also involved (11, 54). Moreover, it has been reported that V3 loop-derived peptides can inhibit viral entry into target cells or syncytium formation between cells expressing the envelope glycoproteins of HIV-1 and cells that co-express CD4 and CCR5 or CXCR4 in a coreceptor-specific manner (55, 69). Mutagenic studies (32, 58, 60, 70) have implicated specific V3 loop residues in the entry of HIV-1 variants into cells expressing CCR5 or CXCR4. Panels of HIV-1 gp120 mutants, created and analyzed in conjunction with structural studies (40, 76), have been used to study the binding of soluble gp120 to CCR5 expressed on Cf2Th cells in the presence of soluble CD4 (sCD4) (14, 52, 53). These CCR5 binding studies revealed that, in addition to the V3 loop, a highly conserved structure in the β19 strand of gp120 is critical for the interaction with CCR5. We wished to apply this method to the characterization of the interaction between gp120 derived from the X4 strain of HIV-1, HIV-1HXBc2, and CXCR4. However, the nonspecific binding of HXBc2 gp120 to the surfaces of both CXCR4-positive and -negative cells impeded such studies (2). Recently, Babcock et al. (2) have successfully incorporated human CXCR4 into paramagnetic proteoliposomes (PMPLs), thus providing a pure, stable source of native CXCR4. PMPLs proved to be a highly useful tool for the study of the specific interaction between CXCR4 and X4 HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins, as well as that between CXCR4 and its natural ligand, SDF-1α (2).

In this study, we analyzed the impact of alanine substitutions in the V3 loop and the β19 strand of HXBc2 gp120 on its binding to CXCR4 displayed on the surface of PMPLs. We also examined the effects of deleting portions of the gp120 V1 and V2 variable loops on the ability of the envelope glycoprotein to interact with CXCR4 in the absence and presence of CD4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)-100 IU of penicillin/ml-100 μg of streptomycin/ml-10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Transfected Cf2Th cells, stably expressing CCR5 or CXCR4 (2, 43), were grown in the same medium supplemented with 0.5 μg of G418 (Cellgro, Herndon, Va.)/ml at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Both purified and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CCR5 (2D7) and -CXCR4 (12G5) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and the purified isotype control (mouse immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a]) were obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). The anti-gp120 D7324 antibody (Ab) directed against the carboxy-terminal domain of soluble gp120 was purchased from International Enzyme, Inc. (Fallbrook, Calif.). The anti-gp120 MAbs F105 and 17b were obtained from Marshall Posner and James Robinson, respectively. The anti-gp120 C11 MAb was purified from hybridoma supernatants as described elsewhere (47). The 1D4 MAb, which reacts with a C9 peptide, was obtained from the National Cell Culture Center. Secondary reagents were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-coupled avidin, peroxidase (PX)-coupled goat anti-human IgG (Fc specific) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and PE-coupled goat anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.). Recombinant secreted CD4-Ig containing the D1-D2 fragment of CD4 fused to the Fc portion of human IgG was a kind gift from Michael Farzan, Harvard Medical School. Four-domain sCD4 was purchased from ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc. (Woburn, Mass.).

Production of wild-type and mutant HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins.

Using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), mutations were introduced into the pSVIIIenv plasmid encoding soluble HXBc2 gp120. The gp120-coding region of each mutant plasmid was then sequenced to confirm the presence of the desired mutation and the absence of any other mutation.

293T cells were cotransfected with the plasmid encoding wild-type or mutant HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins and a plasmid encoding HIV-1 Tat (9:1, wt/wt), using the Geneporter transfection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, Calif.). Sixteen hours after the transfection, the medium was removed, cells were washed with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, and serum-free IS GRO medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, Calif.) supplemented with 100 IU of penicillin/ml-100 μg of streptomycin/ml-10 mM HEPES-12 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies) was added. Cells were allowed to grow for an additional 24 h. The supernatant was harvested, centrifuged at 270 × g for 10 min at 4°C, filtered through a 0.2-μm-diameter-pore filter (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and kept at 4°C until concentration. Fresh serum-free medium supplemented with 3 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma) was added, and cells were allowed to grow for an additional 36 h. The supernatant was harvested, centrifuged and filtered as described above, and pooled with the first batch. Cleared supernatants were then concentrated to approximately 1/30 of the initial volume with a Centricon device (Millipore) and kept frozen at −20°C.

Preparation of PMPLs.

The method used to synthesize CCR5- and CXCR4-PMPLs has been described previously (2, 44). Briefly, Cf2Th cells, stably expressing full-length CCR5 or CXCR4 with the C9 epitope tag fused to their carboxyl termini, were grown in selection medium, harvested with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mM EDTA, pelleted, and stored at −80°C. The pellet of approximately 108 Cf2Th cells expressing CCR5 or CXCR4 was lysed in 1 ml of buffer A {100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 20% glycerol, 1% 3-[(-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxyl-1-propanesulfonic acid (CHAPSO [Anatrace, Maumee, Ohio])} and 1× complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) for 30 min at 4°C. The cell lysate was then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove insoluble material, and the cleared lysate was incubated for 4 h at 4°C with 0.5 × 109 M-280 Dynal beads (Dynal, Lake Success, N.Y.) (250 μl) previously coated with 125 μg of the 1D4 MAb specific for the C9 peptide. The beads were washed five times in buffer A and resuspended in 900 μl of buffer A and 100 μl of sonicated lipids. The lipid mixture consisted of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerophosphate (DOPG) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, Ala.) at 6:3:1 (wt/wt/wt) (the final concentration was 10 mg/ml in PBS). Where indicated, 20 μg of biotinylated DOPG (Avanti Polar Lipids) was also added in the lipid mixture. The beads were then injected in a Slide-A-Lyzer with a 10,000 molecular weight cutoff (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and dialyzed at 4°C against buffer A prepared without CHAPSO. After a 16-h dialysis, PMPLs were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in 500 μl of PBS-0.5% bovine serum albumin-0.02% sodium azide and stored at 4°C.

Liposome staining and FACS analysis.

The native conformation of chemokine receptors captured on PMPLs was assessed by staining with the 2D7 and 12G5 MAbs, which recognize discontinuous epitopes on CCR5 and CXCR4, respectively (21, 75). PMPLs (2 × 106 in 2 μl of buffer) were incubated with 20 μl of PE-coupled 2D7 or 12G5 for 45 min at 20°C. Alternatively, when indicated, 106 biotinylated and 106 nonbiotinylated PMPLs were mixed and simultaneously incubated with PE-coupled 2D7 or 12G5 as described above and with FITC-coupled avidin (1:50). PMPLs were washed in PBS, centrifuged for 2 min at 3,000 × g, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS).

The binding of HXBc2 gp120 to PMPLs was assessed as follows. Approximately 106 CXCR4-PMPLs and 106 biotinylated CCR5-PMPLs were mixed in PBS with 4% FCS (PBS-FCS) supplemented with 4 μl of concentrated wild-type or mutant HXBc2 gp120 supernatant and 100 nM sCD4 in a final volume of 50 μl. After a 45-min incubation at 20°C, the anti-gp120 C11 MAb was added at a final concentration of 10 nM and the incubation continued for another 45 min at 20°C. The PMPLs were washed in PBS-FCS, centrifuged for 2 min at 3,000 × g, resuspended in 20 μl of PBS-FCS supplemented with PE-coupled anti-human IgG (1:20) and FITC-coupled avidin (1:50), and incubated for an additional 30 min at 20°C in the dark. The PMPLs were then washed in PBS, centrifuged for 2 min at 3,000 × g, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and analyzed by FACS. All FACS analyses were performed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan apparatus with CellQuest software.

ELISA.

Each enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) step was carried out in a 100-μl well. Microtiter plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) were coated with the D7324 MAb at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml in 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) for 2 h at 37°C. The D7324 MAb recognizes the HIV-1 gp120 C terminus (45, 46). The wells were then washed four times in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked for 16 h at 4°C with PBS-T supplemented with 5% nonfat dry milk (PBS-TM). The wells were then washed as described above and incubated with concentrated supernatant containing wild-type or mutant HXBc2 gp120 at a 1:2,000 dilution in PBS-T for 2 h at 37°C. The wells were then washed and incubated with various concentrations of the indicated ligands (F105, CD4-Ig, and 17b) in PBS-TM for 1 h at 37°C. Incubations with 17b were performed either without sCD4 or in the presence of 100 nM sCD4. The wells were then washed and incubated with PX-coupled anti-human IgG Ab (1:2,000 in PBS-TM) for 45 min at 37°C. The wells were then washed and incubated with the substrate of PX (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) for 10 to 20 min at 20°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 2 M HCl/well. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm.

RESULTS

Establishment of a gp120-CXCR4 binding assay.

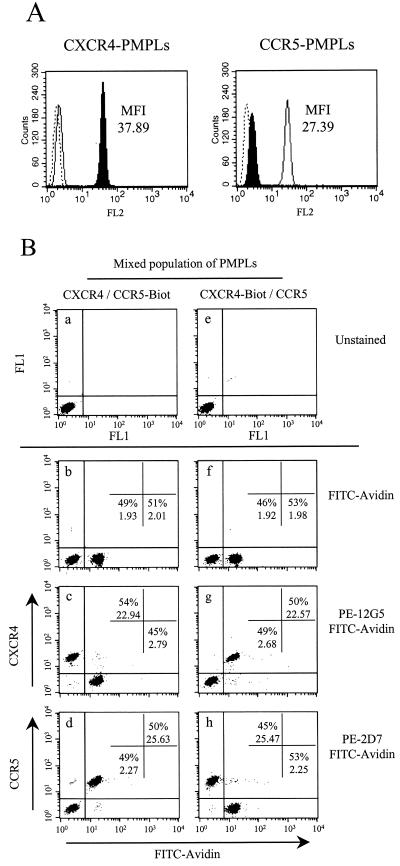

Babcock et al. previously demonstrated that the interaction between gp120 from the X4 strain HXBc2 and CXCR4 cannot be readily studied by using CXCR4-expressing cells because of a high level of nonspecific binding of the gp120 to cell surface molecules (2). We therefore created CXCR4-PMPLs to provide a surface displaying CXCR4 and devoid of other cell surface molecules. CCR5-PMPLs (44) were used as controls in these experiments. To test whether CXCR4 and CCR5 retained their conformations during the preparation process, PMPLs were stained with the PE-coupled 2D7 and 12G5 MAbs, which recognize discontinuous epitopes on CCR5 and CXCR4, respectively. Figure 1A shows FACS profiles of PMPLs stained as indicated and demonstrates that 2D7 and 12G5 efficiently recognized CCR5 and CXCR4 displayed on the respective PMPLs. Together with the previous results of Babcock et al. (2), this confirms that the coreceptors displayed on PMPLs and on the cell surface exhibit similar conformations.

FIG. 1.

Detection of discontinuous epitopes on chemokine receptors incorporated into PMPLs. (A) Approximately 2 × 106 CXCR4-PMPLs (left panel) or CCR5-PMPLs (right panel) in 2-μl volumes were separately stained with 20 μl of the PE-coupled anti-CXCR4 MAb 12G5 (filled profile), the PE-coupled anti-CCR5 MAb 2D7 (empty profile), or an irrelevant Ab (dotted lines). PMPLs were then washed and analyzed by FACS. The MFI values of CXCR4- and CCR5-PMPLs stained with 12G5 (left panel) and 2D7 (right panel), respectively, are indicated. (B) CXCR4-PMPLs and CCR5-PMPLs were mixed and analyzed simultaneously. Approximately 106 CXCR4-PMPLs and 106 CCR5-Biot-PMPLs, each in 1 μl of buffer, were mixed (panels a to d). Alternatively, CXCR4-Biot-PMPLs and CCR5-PMPLs were mixed (panels e to h). PMPLs were left unstained (panels a and e), stained with FITC-coupled avidin (1:50) alone (panels b and f), or stained with FITC-coupled avidin in the presence of 20 μl of PE-coupled 12G5 (panels c and g) or 2D7 (panels d and h) and analyzed by FACS. The percentage of events in each population and the MFI of each population are indicated. Representative results of experiments performed at least three times are shown.

We then asked whether it was possible to mix CCR5- and CXCR4-PMPLs and analyze each subpopulation separately by FACS. To accomplish this, we synthesized PMPLs with biotinylated DOPG, in addition to the POPC, POPE and DOPG lipids. CCR5- or CXCR4-PMPLs synthesized with biotinylated lipids (referred to herein as CCR5-Biot- or CXCR4-Biot-PMPLs, respectively) were mixed with nonbiotinylated CXCR4- or CCR5-PMPLs, respectively, at a 1:1 ratio. The PMPL mixtures were stained with either PE-coupled 2D7 or 12G5 and with FITC-coupled avidin and then analyzed by FACS. Panels b, c, and d of Fig. 1B show that FITC-coupled avidin staining can specifically separate the population of CCR5-Biot-PMPLs from that of the CXCR4-PMPLs. Only the FITChigh population was specifically stained with the 2D7 MAb against CCR5. Conversely, only the FITClow population was specifically stained with the 12G5 MAb against CXCR4. The 2D7 and 12G5 MAbs were also able to discriminate between CCR5-PMPLs and CXCR4-Biot-PMPLs (Fig. 1B, panels f, g, and h). These results demonstrate that little or no spontaneous lipid exchange occurs between heterologous PMPLs and that the binding activities of CXCR4- and CCR5-specific ligands can be analyzed simultaneously by using a mixed population of biotinylated and non-biotinylated PMPLs.

HIV-1 gp120 binding to CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs.

FACS analysis was used to assess the binding of gp120 variants to CXCR4-PMPLs. The wild-type and mutant gp120 glycoproteins were produced transiently in serum-free medium, concentrated 30-fold, and incubated with a mixture of CXCR4-PMPLs and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs. Bound gp120 was detected with the C11 anti-gp120 MAb, followed by staining with a PE-coupled anti-human IgG Ab. The amounts of gp120, sCD4, and C11 giving the best staining profiles were determined empirically (data not shown) and used for the entire panel of mutants.

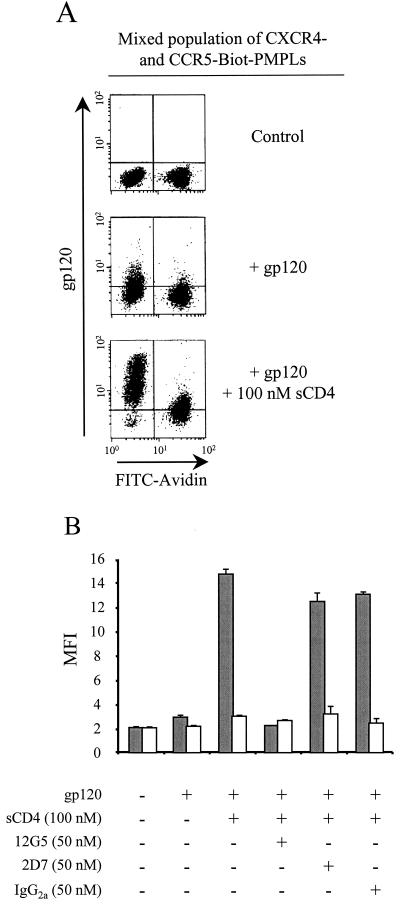

Figure 2A shows that only very weak binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4-PMPLs was detected in the absence of sCD4 (middle panel). In the presence of sCD4, HXBc2 gp120 strongly and selectively bound to CXCR4-PMPLs, with only a slight background signal detected on CCR5-Biot-PMPLs. sCD4 also induced specific binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4-Biot-PMPLs but not to CCR5-PMPLs (data not shown), indicating that the presence of biotinylated lipids does not prevent the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to PMPLs.

FIG. 2.

Binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4- and CCR5-PMPLs. (A) Equal numbers (106 each) of CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs were mixed and incubated with HXBc2 gp120 (middle and lower panels) and 100 nM of sCD4 (lower panel). Bound gp120 was then detected by an additional incubation with the anti-gp120 C11 MAb and with a PE-coupled secondary Ab (all panels). In addition, PMPLs were stained with FITC-coupled avidin (1:50) to detect the CCR5-Biot-PMPLs (all panels). Stained PMPLs were washed and analyzed by FACS. (B) Equal numbers (106 each) of CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs were mixed and incubated with or without HXBc2 gp120 and sCD4 in the presence of 12G5, 2D7, or an irrelevant MAb. Bound gp120 was then detected by staining PMPLs with the anti-gp120 C11 MAb and a PE-coupled anti-human IgG Ab. In addition, PMPLs were stained with FITC-coupled avidin (1:50) to sort the CCR5-Biot-PMPLs. The MFI values of the gp120 staining for the CXCR4-PMPLs (filled bars) and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs (open bars) are reported.

To confirm the specificity of the HXBc2 gp120-CXCR4 interaction observed in this model, CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs were mixed and incubated with concentrated supernatant containing HXBc2 gp120, sCD4, and CXCR4- and CCR5-specific MAbs. PMPLs were then stained as described previously and analyzed by FACS. The relative binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs, represented by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) obtained in the FL2 channel, is shown in Fig. 2B. The HXBc2 gp120-CXCR4 interaction is CD4 dependent, since only minimal binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4-PMPLs was observed in the absence of sCD4. The 12G5 MAb directed against CXCR4 inhibited the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4-PMPLs. Neither the isotype-matched control nor the 2D7 MAb inhibited this interaction. Altogether, these results suggest that the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4 displayed on PMPLs is specific and can be studied on a mixed population of CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs.

Production and quantitation of HXBc2 gp120 mutants.

Previous studies (14, 52, 53) suggested that the V3 loop and the β19 strand of gp120 cooperate to form a binding site for CCR5. To determine whether equivalent regions of an X4 gp120 are important for CXCR4 binding, a panel of alanine-substitution gp120 mutants was created and analyzed for the ability to bind CXCR4-PMPLs in the assays described above. We also analyzed the impact of the removal of the V2 variable loop and both the V1 and V2 loops on the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4. In the ΔV2 and ΔV1/V2 mutants, the V2 loop (amino acids 162 to 191) and the V1 and V2 loops (amino acids 128 to 194), respectively, had been replaced by a glycine-alanine-glycine linker.

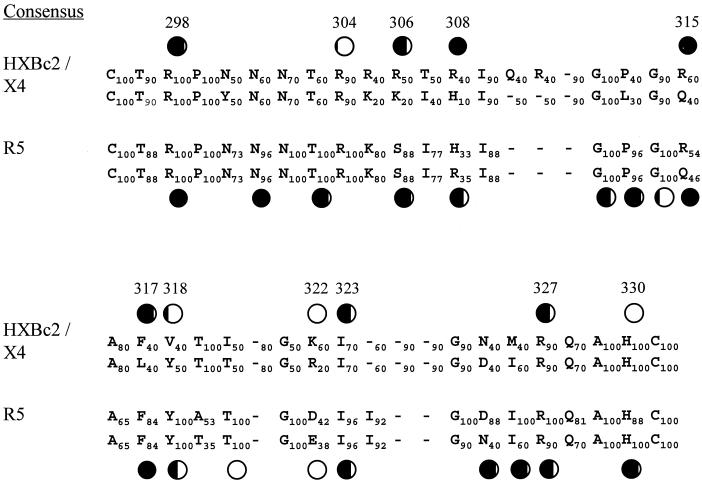

Our mutagenesis work on the V3 loop of HXBc2 gp120 was guided by the previously assembled consensus amino acid sequences of the V3 loops from X4, R5, and dual-tropic HIV-1 strains (Fig. 3) (32, 71). Basic amino acids conserved in both X4 and R5 HIV-1 strains, corresponding to R298, R304, R308, R327, and H330 in HXBc2 gp120, were altered. We also wanted to assess the contribution of basic V3 loop amino acids (R306 and K322) that are highly conserved only in X4 strains. Four additional V3 loop residues were also selected for alteration. Positions 317 and 318, where F and Y residues are highly conserved in R5 strains and are important for CCR5 binding (52, 53), are allowed some flexibility in X4 strains. In X4 strains, two different hydrophobic amino acid residues occur with approximately equal frequencies at these positions (Fig. 3). We also altered residues 315, where R and Q are equally represented in both X4 and R5 strains, and I323, which is conserved in X4 and R5 strains.

FIG. 3.

V3 loop sequence comparison between CXCR4- and CCR5-using viruses. The consensus sequences of the V3 loops from X4 and R5 strains are compared, with the upper row in the CXCR4 consensus corresponding to the sequence of HXBc2 gp120. The number next to each residue indicates the frequency at which Hung et al. (32) found the corresponding residue. A hyphen without any number denotes a deletion in the consensus sequence. The amino acids are numbered according to the sequence of HXBc2 gp120 (39). The circles are located above residues in which single amino acid changes have been introduced, and the resulting mutants were assessed for ability to bind CXCR4 or CCR5 (references 14, 52, and 53 and this study). The ability of the mutant to bind the chemokine receptor, relative to that of the wild-type gp120, is indicated by the amount of the circle that is filled (completely open, wild-type binding; completely filled, no detectable binding).

In addition to the V3 loop, we studied the R419-I420-K421-Q422 motif located in the gp120 β19 strand. Together with the stem of the V1 and V2 loops, this region is involved in the formation of a four-stranded, antiparallel β sheet (40, 76). This motif has been implicated in the binding of YU2 gp120 to CCR5 (14, 52, 53). An alanine was substituted in place of each of these four residues in the HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein.

Following 293T cell transfection, wild-type and mutant HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins were produced transiently and concentrated. To ensure that the same amount of gp120 was added in each binding assay to PMPLs, the concentrations of the HXBc2 gp120 mutants were normalized to that of the wild-type gp120 by dot blotting, using a rabbit serum raised against the core of gp120 (data not shown).

Assessment of the conformational integrity of the gp120 mutants.

To assess the conformational integrity of the mutant gp120 glycoproteins, we developed an ELISA to measure the binding of conformation-dependent ligands, including a MAb (F105) directed against a gp120 epitope (CD4BS epitope) that overlaps the CD4 binding site (50, 65). We also compared the binding of CD4-Ig to wild-type and mutant HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins. Finally, we analyzed the integrity of the CD4i epitope (64), which is recognized by the 17b MAb, in the absence and presence of CD4. Figure 4 illustrates the binding of F105, CD4-Ig, and 17b to wild-type HXBc2 gp120. The binding curves allowed us to calculate the apparent dissociation constants (KD) of the HXBc2 gp120/F105 and HXBc2 gp120/CD4-Ig interactions (∼3 and 4 nM, respectively). As expected (64), the binding of the 17b MAb to immobilized HXBc2 gp120 increased when sCD4 was added, reflecting an increased affinity of 17b for HXBc2 gp120 in the presence of sCD4. The apparent KD values calculated from the curves were ∼30 nM in the absence and ∼2 nM in the presence of sCD4.

FIG. 4.

Measurements of HXBc2 gp120 affinity for various ligands by ELISA. Microtiter plates previously coated with the D7324 Ab were incubated with a 1:2,000 dilution of concentrated cell culture supernatant containing HXBc2 gp120. Increasing concentrations of F105 (upper panel), CD4-Ig (middle panel), and 17b (lower panel) were then incubated with the immobilized gp120 and detected by a PX-coupled anti-human IgG Ab. The binding of the 17b MAb to gp120 was studied in the absence (open circles) or the presence (filled circles) of sCD4. The apparent KD values, which were estimated according to the ligand concentration that yielded an optical density (OD) value that was half that obtained at saturation, are noted. Representative results of the ELISA, which was performed at least three times, are shown.

Binding characteristics of HXBc2 gp120 mutants.

Binding assays on PMPLs were performed as described above. The value for binding of wild-type HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4-PMPLs in the presence of sCD4 was arbitrarily set to 100, and the other binding data were normalized to this value. The apparent KD values of the interactions between the HXBc2 gp120 mutants and F105, CD4-Ig, and 17b were determined using the above-described ELISA. The results are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Binding of wild-type and mutant HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins to CXCR4, CCR5, CD4, and antibodies

| HXBc2 gp120 variantf | CXCR4 binding (MFI)a

|

CCR5 binding (MFI)a

|

KD (nM) with:c,e

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +CD4 | −CD4 | +CD4 | −CD4 | F105 | CD4-Ig | 17b

|

||

| +CD4 | −CD4 | |||||||

| Mock | 13.6 ± 1.4 | 13.6 ± 1.4 | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 13.7 ± 1.5 | ||||

| WT | 100 | 23 ± 1.2 | 31 ± 4.9 | 22 ± 4.8 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 23.8 ± 9.6 |

| Alanine substitutions (V3 loop) | ||||||||

| R298A | 22.4 ± 3.4 | 13.8 ± 1.3 | 23.3 ± 4.2 | 15.0 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 2.5 | 4.8 ± 2.9 | >100d |

| R304A | 79.7 ± 9.0 | 14.9 ± 1.4 | 23.3 ± 3.1 | 16.4 ± 3.1 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 30.0 ± 0.0 |

| R306A | 29.5 ± 2.2 | 14.1 ± 1.3 | 21.2 ± 2.1 | 15.2 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 15.0 ± 8.2 |

| R308A | 16.6 ± 1.5 | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 26.1 ± 5.0 | 16.7 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 17.5 ± 7.5 |

| R315A | 16.8 ± 1.5 | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 26.8 ± 3.9 | 17.2 ± 3.2 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 22.5 ± 7.5 |

| F317A | 19.6 ± 1.8 | 14.4 ± 1.4 | 34.9 ± 5.0 | 20.4 ± 3.6 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 15.0 ± 5.0 |

| V318A | 68.7 ± 9.4 | 15.1 ± 1.4 | 38.0 ± 5.1 | 20.3 ± 2.3 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 20.0 ± 0.0 |

| K322A | 102.9 ± 9.2 | 17.0 ± 1.0 | 24.6 ± 1.4 | 17.3 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 17.5 ± 7.5 |

| I323A | 37.4 ± 5.8 | 15.5 ± 1.3 | 18.1 ± 2.1 | 14.9 ± 1.8 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 25.0 ± 5.0 |

| R327A | 39.1 ± 4.0 | 14.3 ± 1.4 | 22.5 ± 4.8 | 14.8 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.5 | >100d |

| H330A | 115.4 ± 13.7 | 21.7 ± 0.4 | 25.5 ± 2.2 | 17.9 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 22.5 ± 7.5 |

| Alanine substitutions (β19 strand) | ||||||||

| R419A | 78.3 ± 8.5 | 14.4 ± 1.2 | 23.3 ± 4.8 | 14.8 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | >100d |

| I420A | 27.0 ± 0.2b | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 21.6 ± 0.2 | 18.4 ± 0.5 | >100d | >100d | — | — |

| K421A | 23.1 ± 3.0 | 13.5 ± 1.3 | 16.3 ± 2.1 | 17.4 ± 4.1 | — | 4.8 ± 0.3 | — | — |

| Q422A | 47.1 ± 4.9 | 14.1 ± 1.4 | 21.9 ± 4.3 | 15.2 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | — | — |

| Deletions (V1 and/or V2 loop) | ||||||||

| ΔV2 | 68.8 ± 2.3 | 37.7 ± 1.0 | 25.7 ± 0.5 | 20.5 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 1.5 |

| ΔV1/V2 | 173.4 ± 0.5 | 141.5 ± 0.2 | 37.6 ± 0.7 | 32.7 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

The binding of wild-type and mutant HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins to a mixed population of CXCR4- and CCR5-Biot-PMPLs, without or in the presence of 100 nM sCD4, was measured as described in the Fig. 2 legend. The MFI corresponding to the binding of wild-type HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4-PMPLs in the presence of sCD4 was set to 100, and the other MFI values were normalized to this.

The binding of the I420A mutant to PMPLs was also measured in large excesses of sCD4 (500 nM and 5 μM) to overcome the lower affinity of this mutant for CD4, but the results of the PMPL binding assay were not significantly different from those shown. Binding assays on PMPLs were performed at least three times.

The KD values for the binding of the envelope glycoproteins to the indicated ligands were determined as described in the Fig. 3 legend.

Minimal KD values were estimated in cases in which saturation could not be achieved.

Dashes indicate cases in which no ligand binding was detectable. ELISAs were performed at least twice in duplicate.

WT, wild type; Mock, concentrated supernatant of cells transfected with the Tat-expressing plasmid only.

Alanine substitutions introduced into some V3 loop residues (R304, K322, and H330) did not significantly affect the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4 in the presence of sCD4. By contrast, some substitutions (R306A, V318A, I323A, and R327A) partially decreased the binding of HXBc2 gp120 mutants to CXCR4. Four V3 loop changes (R298A, R308, R315A, and F317A) dramatically reduced or completely abolished CXCR4 binding. None of the changes significantly increased gp120 binding to CXCR4 or resulted in a CD4-independent binding phenotype. All of the V3 loop mutants bound the F105 MAb comparably to that of the wild-type HXBc2 gp120. Binding of the V3 loop mutants to CD4-Ig was also efficient. Two of the mutants (R298A and R327A) with changes in the base of the V3 loop were not recognized by the 17b Ab in the absence of sCD4. However, 17b binding was restored in the presence of CD4, a phenotype that has been observed for other V3 mutants (53, 77). These results suggested that the attenuation of CXCR4 binding observed for some of the V3 mutants is specific and not due to global changes in gp120 conformation.

In the β19 strand, all but one (R419A) of the alanine substitutions strongly reduced the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4. These substitutions also dramatically reduced the affinity of 17b for HXBc2 gp120 mutants (KD > 1,000 nM, both in the presence and in the absence of sCD4). This is consistent with the known contacts of the 17b Ab with these residues (52, 53). The K421A mutant bound CD4-Ig similarly to wild-type gp120, indicating that the mutant is not globally misfolded. The affinity of F105 for this mutant was dramatically reduced (KD > 1,000 nM), consistent with prior studies mapping the F105 epitope (65). The I420A substitution dramatically reduced binding to all of the conformation-dependent ligands and therefore appears to have significantly disrupted gp120 conformation.

In the absence of sCD4, the gp120 variants lacking the V2 loop bound CXCR4 more efficiently than the wild-type gp120. The CD4-independent binding of the ΔV1/V2 mutant was particularly robust, exceeding that of the wild-type gp120 in the presence of sCD4. Both ΔV2 and ΔV1/V2 glycoproteins bound CXCR4 in the presence of sCD4. The estimated KD values associated with the binding of the V1/V2 mutants to F105 or CD4-Ig were close to the KD values obtained with wild-type HXBc2 gp120. The affinities of 17b for the ΔV2 and the ΔV1/V2 mutants in the absence of sCD4 were higher than that of wild-type gp120 and were nearly identical to the affinity of 17b for wild-type HXBc2 gp120 in the presence of sCD4 (KD = 1 to 3 nM). The affinity of 17b for both deletion mutants increased slightly in the presence of sCD4.

The binding of all of these mutants was also analyzed on CXCR4-PMPLs prepared from HeLa cells overexpressing CXCR4, with similar results (data not shown). Thus, the binding pattern observed was independent of the cell type in which CXCR4 is produced.

The binding of the HXBc2 gp120 mutants to CCR5-PMPLs in the presence of sCD4 was close to that of wild-type gp120. Thus, nonspecific binding to CCR5 or to the PMPL surface was not increased by the introduced changes in HXBc2 gp120.

DISCUSSION

Although the ability of HIV-1 mutants to infect cells expressing CD4 and CXCR4 has been studied (11, 33, 35, 58, 60, 69, 71), direct studies of the binding of HIV-1 gp120 to CXCR4 have been hampered by the nonspecific interactions between X4 gp120 glycoproteins and cell surfaces and by the low affinity of the gp120-CXCR4 association (2, 31). The use of CXCR4-PMPLs in binding assays allowed the evaluation of specific gp120-CXCR4 interactions (2). Furthermore, by examining the effects of a panel of anti-gp120 MAbs on CXCR4 binding, we could implicate particular gp120 regions in CXCR4 binding (2). Here, we employed alanine substitution mutagenesis to investigate the importance of specific gp120 residues in CXCR4 binding. These studies were facilitated by devising methods for concentrating the gp120 mutants and for simultaneous study of gp120 binding to CXCR4- and CCR5-PMPLs. The latter innovation provided a valuable internal control that allowed us to assess any nonspecific binding exhibited by the gp120 mutants.

Our results demonstrate the importance of the V3 loop and the β19 strand of an X4 gp120 glycoprotein in binding CXCR4. We hypothesized that these gp120 elements contribute to contacts with CXCR4, based upon the observations of Babcock et al. that Abs directed against the V3 loop and CD4i epitopes blocked the interaction of gp120-CD4 complexes with CXCR4 (2). These two elements on the gp120 surface also mediate the interaction with CCR5 (14, 52, 53), underscoring the generality of models of chemokine receptor binding that have been proposed based on studies of the gp120-CCR5 association (53, 78). Our results suggest that the ability of certain CXCR4 mutants to serve as coreceptors for R5 HIV-1 isolates (9, 72) may involve structural features of gp120 that are conserved between R5 and X4 HIV-1 strains.

Several amino acid residues in the V3 loop make key contributions to CXCR4 binding. These consist of basic and hydrophobic-aromatic residues. Alanine substitutions for five arginine residues at positions 298, 306, 308, 315, and 327 significantly reduced or abolished gp120 binding to CXCR4 but did not affect the ability to bind CD4. These basic residues on the V3 loop, which is well exposed on the gp120 surface (45), likely contribute to electrostatic interactions and the formation of specific salt bridges with CXCR4. This is consistent with the acidic nature of the CXCR4 N terminus and extracellular loops. Specific acidic residues on CXCR4 (E2, D10, E14, E15, D20, D22, and E26 in the amino terminus and D97, D193, and D262 in the extracellular loops) have been implicated in the ability of this chemokine receptor to serve as an efficient coreceptor for at least a subset of HIV-1 strains (4, 8, 9, 34, 49, 72, 79).

Arginines 306 and 308 are located in a stretch of basic residues in the amino-terminal portion of the V3 loops of CXCR4-using viruses (Fig. 3). Arginine or lysine is found at residue 306 in the majority of X4 virus sequences, whereas serine is found at the analogous position in almost all R5 viruses. This suggests a role for this residue in determining the specificity of coreceptor use. Additional evidence supports this hypothesis. The introduction of an arginine at this position in the V3 loop of the R5 HIV-1NH2 isolate enabled this virus to utilize CXCR4 for entry into target cells under certain circumstances (35). Moreover, the S306R substitution in a peptide derived from the V3 loop of an R5 HIV-1 strain allowed the peptide to inhibit the infection of CXCR4-expressing cells by HIV-1LAI but not the infection of CCR5-positive cells by an R5 virus, HIV-1BX08 (69). Substitution of an alanine for serine 306 in the gp120 glycoprotein of an R5 HIV-1 isolate resulted in a significant reduction in CCR5 binding (14).

Some of the basic V3 loop residues implicated in CXCR4 binding (arginines 298, 308, 315, and 327) are conserved among X4 and R5 HIV-1 strains (Fig. 3). Thus, these residues may contribute to the binding of HIV-1 to both of its major coreceptors. Indeed, alteration of each of these four residues has been shown to disrupt the interaction with CCR5 of gp120 glycoproteins from R5 HIV-1 isolates (14, 52). Consistent with a role for arginine 298 in receptor binding, an R298A substitution, but not the more conservative substitution R298K, abolished the ability of the ConB virus to infect HOS-CD4 cells expressing CCR5 (70). The proximity of residues 298 and 327, located in the base of the V3 loop, to the gp120 β19 strand (40) suggests that these elements may contribute to a discontinuous surface that binds the chemokine receptor.

Interestingly, some alanine substitutions, although involving basic amino acids that are highly conserved among X4 strains (R304, K322, and H330 in HXBc2 gp120), did not significantly modify the binding of the corresponding mutants to CXCR4. Arginine 304 and histidine 330 are also highly conserved in R5 strains (Fig. 3). It has been reported that the R304A substitution did not prevent the infection of CCR5-expressing cells by HIV-1 ConB (70). This demonstrates that the V3 loop exhibits conserved features that do not seem to be necessary either for coreceptor binding or for virus entry in vitro. Thus, conservation of these residues apparently results from selective pressure on X4 and R5 viruses other than the requirement to preserve gp120 structures involved in the binding to CXCR4/CCR5 or the entry process. By contrast, an alanine substitution for histidine 330 in the gp120 from an R5 HIV-1 isolate did specifically attenuate CCR5 binding (52). Thus, this conserved residue may make direct or indirect contributions to maintenance of a binding site for CCR5 but may be less critical for CXCR4 binding.

The lack of effect of the K322A substitution on CXCR4 binding was surprising, given the evidence that the presence of basic and acidic amino acids at this position strongly correlates with the use of CXCR4 and CCR5, respectively, by HIV-1 isolates (6, 7, 42). Likewise, alteration of the aspartic or glutamic acids at residue 322 did not reduce the binding of gp120 from R5 HIV-1 strains to CCR5 (14, 52). The presence of basic or acidic residues at position 322 (and thus coreceptor preference) correlates with the presence of acidic/uncharged or basic residues, respectively, at position 440 in the gp120 sequence (6, 7, 42, 48). The interaction of residues 322 and 440 may contribute to contacts between the V3 loop and the gp120 core that differ in a coreceptor-dependent manner and facilitate aspects of HIV-1 infection not measured herein.

The tip of the V3 loop is thought to contain a β-turn, based upon the presence of a highly conserved glycine-proline-glycine motif and upon X-ray crystal and nuclear magnetic resonance structures of V3 peptides complexed with Abs (26, 61, 67). Residue 315, which immediately follows this β-turn, is either an arginine or glutamine in both X4 and R5 HIV-1 isolates (39). This suggests that structural elements common to these residues (Cβ-Cγ and associated atoms) may be critical to V3 loop function. Alanine substitutions at residue 315 completely attenuated CXCR4 or CCR5 binding (14), which is consistent with this model. Residues 316 to 318 in the V3 tip are also similar in all HIV-1 strains, with residue 317 almost always a phenylalanine or leucine. Both of these residues share common side chain elements (Cβ, Cγ, Cδ1, and Cδ2) and a hydrophobic character. Hydrophobic pockets exist on the surface of many chemokine-binding G protein-coupled receptors, and studies with CCR5-directed inhibitors suggest that these may interact with such a pocket on CCR5 (20). The phenylalanine or leucine at position 317 in the V3 loop tip is a likely candidate for occupying such a hydrophobic pocket on CXCR4 or CCR5. Indeed, changes in residue 317 dramatically disrupt chemokine receptor binding of gp120 glycoproteins from both X4 and R5 viruses (Table 1) (14, 53).

Rizzuto et al. previously reported the involvement of the R419-I420-K421-Q422 motif in the gp120 β19 strand in the binding of YU2 gp120 to CCR5 (52, 53). The β19 strand of the gp120 glycoprotein of R5 HIV-1 isolates has been implicated in the binding of the sulfated CCR5 amino terminus (13, 14, 24). The amino terminus of CXCR4 appears to be less critical for its coreceptor function than the analogous region on CCR5 (3, 4, 8, 9, 19, 22, 23, 30, 34, 49, 51, 72, 79). It will be of interest to determine whether the β19 region of X4 gp120 glycoproteins interacts with the CXCR4 N terminus or with other parts of the molecule. We addressed whether this motif is involved in the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4. The K421A mutant bound CD4 efficiently, indicating that the mutant protein is folded in a native conformation, but was very attenuated for CXCR4 binding. This mutant was not recognized efficiently by the F105 and 17b Abs, consistent with previous studies indicating the involvement of lysine 421 in the epitopes for these Abs (40, 53, 64, 65). CXCR4 binding of the alanine-substitution mutant in the adjacent glutamine 422 was also lower than that of the wild-type gp120 glycoprotein, despite efficient recognition of this mutant by F105 and CD4. These results suggest that residues in the β19 strand of gp120 contribute to CXCR4 binding. Alteration of arginine 419 had less of an effect on CXCR4 binding; of the four residues in the 419 to 422 motif, arginine 419 also appears to be the least critical for CCR5 binding (52, 53). Isoleucine 420 has been shown to be important for CCR5 binding (52, 53), but because of the general conformational disruption resulting from the alanine substitution in the HXBc2 protein, we were unable to evaluate its specific contribution to CXCR4 binding.

We studied the involvement of the V1 and V2 loops in the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4. The ΔV2 and ΔV1/V2 mutants exhibited similar affinities for F105, CD4-Ig, and 17b. Interestingly, both mutants bound to 17b in a CD4-independent manner as efficiently as the wild-type gp120 in the presence of sCD4. This confirms that, in HXBc2 gp120, the CD4i epitope recognized by 17b is partially masked by the V1 and V2 loops (77). Although the removal of either the V2 loop or both the V1 and V2 loops resulted in the exposure of this epitope, the removal of both loops was required to confer a CD4-independent phenotype to the gp120-CXCR4 interaction. This indicates that the CD4i epitopes recognized by 17b and the epitopes involved in CXCR4 binding only partially overlap. It also demonstrates that the V1 and V2 loops are not required for the binding of HXBc2 gp120 to CXCR4. Kolchinsky et al. previously reported that the displacement or removal of the V1 and V2 loops in the gp120 derived from HIV-1ADA was sufficient to render the binding of the corresponding mutants to CCR5 independent of CD4 (37, 38). Thus, it seems that in both X4 and R5 strains, the V1 and V2 loops are positioned to influence the accessibility of the coreceptor binding site. In the case of at least one R5 virus, removal of the V1/V2 loops resulted in CD4-independent infection of CCR5-expressing cells (37, 38). However, removal of the V1/V2 loops from the X4 HXBc2 virus resulted in a virus that was replication competent but still dependent on CD4 for infection (5). The requirements for CD4-independent infection apparently extend beyond exposure of the chemokine receptor-binding region on gp120 and may include sufficient affinity for the coreceptor and the ability to negotiate other conformational changes normally favored by CD4 binding.

Our study demonstrates that general features of the chemokine receptor-binding surface of gp120 are shared by R5 and X4 HIV-1 isolates. How the relatively subtle adjustments in the V3 loop result in coreceptor choice needs to be explored further. The identification of structures important for receptor binding of all HIV-1 isolates should assist efforts in defining targets for intervention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI24755, AI31783, AI41851, and AI24030), by a Center for AIDS Research grant (AI42848), and by gifts from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation and the late William F. McCarty-Cooper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib, G., C. Combadiere, C. C. Broder, Y. Feng, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272:1955-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G. J., T. Mirzabekov, W. Wojtowicz, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Ligand binding characteristics of CXCR4 incorporated into paramagnetic proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38433-38440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanpain, C., B. Lee, J. Vakili, B. J. Doranz, C. Govaerts, I. Migeotte, M. Sharron, V. Dupriez, G. Vassart, R. W. Doms, and M. Parmentier. 1999. Extracellular cysteines of CCR5 are required for chemokine binding, but dispensable for HIV-1 coreceptor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18902-18908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brelot, A., N. Heveker, M. Montes, and M. Alizon. 2000. Identification of residues of CXCR4 critical for human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor and chemokine receptor activities. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23736-23744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao, J., N. Sullivan, E. Desjardin, C. Parolin, J. Robinson, R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 1997. Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 71:9808-9812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrillo, A., and L. Ratner. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism for T-lymphoid cell lines: role of the V3 loop and C4 envelope determinants. J. Virol. 70:1301-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrillo, A., D. B. Trowbridge, P. Westervelt, and L. Ratner. 1993. Identification of HIV1 determinants for T lymphoid cell line infection. Virology 197:817-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabot, D. J., and C. C. Broder. 2000. Substitutions in a homologous region of extracellular loop 2 of CXCR4 and CCR5 alter coreceptor activities for HIV-1 membrane fusion and virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23774-23782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chabot, D. J., P. F. Zhang, G. V. Quinnan, and C. C. Broder. 1999. Mutagenesis of CXCR4 identifies important domains for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 X4 isolate envelope-mediated membrane fusion and virus entry and reveals cryptic coreceptor activity for R5 isolates. J. Virol. 73:6598-6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan, D. C., D. Fass, J. M. Berger, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho, M. W., M. K. Lee, M. C. Carney, J. F. Berson, R. W. Doms, and M. A. Martin. 1998. Identification of determinants on a dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein that confer usage of CXCR4. J. Virol. 72:2509-2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choe, H., M. Farzan, Y. Sun, N. Sullivan, B. Rollins, P. D. Ponath, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, G. LaRosa, W. Newman, N. Gerard, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell 85:1135-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cormier, E. G., M. Persuh, D. A. Thompson, S. W. Lin, T. P. Sakmar, W. C. Olson, and T. Dragic. 2000. Specific interaction of CCR5 amino-terminal domain peptides containing sulfotyrosines with HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5762-5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cormier, E. G., D. N. Tran, L. Yukhayeva, W. C. Olson, and T. Dragic. 2001. Mapping the determinants of the CCR5 amino-terminal sulfopeptide interaction with soluble human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120-CD4 complexes. J. Virol. 75:5541-5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalgleish, A. G., P. C. Beverley, P. R. Clapham, D. H. Crawford, M. F. Greaves, and R. A. Weiss. 1984. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature 312:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doms, R. W., and D. Trono. 2000. The plasma membrane as a combat zone in the HIV battlefield. Genes Dev. 14:2677-2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doranz, B. J., J. Rucker, Y. Yi, R. J. Smyth, M. Samson, S. C. Peiper, M. Parmentier, R. G. Collman, and R. W. Doms. 1996. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell 85:1149-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragic, T., A. Trkola, S. W. Lin, K. A. Nagashima, F. Kajumo, L. Zhao, W. C. Olson, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, G. P. Allaway, T. P. Sakmar, J. P. Moore, and P. J. Maddon. 1998. Amino-terminal substitutions in the CCR5 coreceptor impair gp120 binding and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J. Virol. 72:279-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dragic, T., A. Trkola, D. A. Thompson, E. G. Cormier, F. A. Kajumo, E. Maxwell, S. W. Lin, W. Ying, S. O. Smith, T. P. Sakmar, and J. P. Moore. 2000. A binding pocket for a small molecule inhibitor of HIV-1 entry within the transmembrane helices of CCR5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5639-5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endres, M. J., P. R. Clapham, M. Marsh, M. Ahuja, J. D. Turner, A. McKnight, J. F. Thomas, B. Stoebenau-Haggarty, S. Choe, P. J. Vance, T. N. Wells, C. A. Power, S. S. Sutterwala, R. W. Doms, N. R. Landau, and J. A. Hoxie. 1996. CD4-independent infection by HIV-2 is mediated by fusin/CXCR4. Cell 87:745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farzan, M., H. Choe, L. Vaca, K. Martin, Y. Sun, E. Desjardins, N. Ruffing, L. Wu, R. Wyatt, N. Gerard, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1998. A tyrosine-rich region in the N terminus of CCR5 is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and mediates an association between gp120 and CCR5. J. Virol. 72:1160-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farzan, M., T. Mirzabekov, P. Kolchinsky, R. Wyatt, M. Cayabyab, N. P. Gerard, C. Gerard, J. Sodroski, and H. Choe. 1999. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of CCR5 facilitates HIV-1 entry. Cell 96:667-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farzan, M., N. Vasilieva, C. E. Schnitzler, S. Chung, J. Robinson, N. P. Gerard, C. Gerard, H. Choe, and J. Sodroski. 2000. A tyrosine-sulfated peptide based on the N terminus of CCR5 interacts with a CD4-enhanced epitope of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein and inhibits HIV-1 entry. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33516-33521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghiara, J. B., E. A. Stura, R. L. Stanfield, A. T. Profy, and I. A. Wilson. 1994. Crystal structure of the principal neutralization site of HIV-1. Science 264:82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glushakova, S., Y. Yi, J. C. Grivel, A. Singh, D. Schols, E. De Clercq, R. G. Collman, and L. Margolis. 1999. Preferential coreceptor utilization and cytopathicity by dual-tropic HIV-1 in human lymphoid tissue ex vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 104:R7-R11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grivel, J. C., and L. B. Margolis. 1999. CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 are equally cytopathic for their T-cell targets in human lymphoid tissue. Nat. Med. 5:344-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henkel, T., P. Westervelt, and L. Ratner. 1995. HIV-1 V3 envelope sequences required for macrophage infection. AIDS 9:399-401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill, C. P., D. Worthylake, D. P. Bancroft, A. M. Christensen, and W. I. Sundquist. 1996. Crystal structures of the trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein: implications for membrane association and assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3099-3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman, T. L., G. Canziani, L. Jia, J. Rucker, and R. W. Doms. 2000. A biosensor assay for studying ligand-membrane receptor interactions: binding of antibodies and HIV-1 Env to chemokine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:11215-11220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung, C. S., N. Vander Heyden, and L. Ratner. 1999. Analysis of the critical domain in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 utilization. J. Virol. 73:8216-8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang, S. S., T. J. Boyle, H. K. Lyerly, and B. R. Cullen. 1991. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science 253:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kajumo, F., D. A. Thompson, Y. Guo, and T. Dragic. 2000. Entry of R5X4 and X4 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains is mediated by negatively charged and tyrosine residues in the amino-terminal domain and the second extracellular loop of CXCR4. Virology 271:240-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato, K., H. Sato, and Y. Takebe. 1999. Role of naturally occurring basic amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype E envelope V3 loop on viral coreceptor usage and cell tropism. J. Virol. 73:5520-5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klatzmann, D., E. Champagne, S. Chamaret, J. Gruest, D. Guetard, T. Hercend, J. C. Gluckman, and L. Montagnier. 1984. T-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAV. Nature 312:767-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolchinsky, P., E. Kiprilov, P. Bartley, R. Rubinstein, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Loss of a single N-linked glycan allows CD4-independent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by altering the position of the gp120 V1/V2 variable loops. J. Virol. 75:3435-3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolchinsky, P., T. Mirzabekov, M. Farzan, E. Kiprilov, M. Cayabyab, L. J. Mooney, H. Choe, and J. Sodroski. 1999. Adaptation of a CCR5-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate for CD4-independent replication. J. Virol. 73:8120-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korber, B., C. Kuiken, B. Foley, S. Pillai, and J. Sodroski. 1998. Numbering positions in HIV relative to HXBc2. In Human retroviruses and AIDS. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N. Mex.

- 40.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miedema, F., L. Meyaard, M. Koot, M. R. Klein, M. T. Roos, M. Groenink, R. A. Fouchier, A. B. Van't Wout, M. Tersmette, P. T. Schellekens, et al. 1994. Changing virus-host interactions in the course of HIV-1 infection. Immunol. Rev. 140:35-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milich, L., B. H. Margolin, and R. Swanstrom. 1997. Patterns of amino acid variability in NSI-like and SI-like V3 sequences and a linked change in the CD4-binding domain of the HIV-1 Env protein. Virology 239:108-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirzabekov, T., N. Bannert, M. Farzan, W. Hofmann, P. Kolchinsky, L. Wu, R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 1999. Enhanced expression, native purification, and characterization of CCR5, a principal HIV-1 coreceptor. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28745-28750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirzabekov, T., H. Kontos, M. Farzan, W. Marasco, and J. Sodroski. 2000. Paramagnetic proteoliposomes containing a pure, native, and oriented seven-transmembrane segment protein, CCR5. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:649-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore, J. P., Q. J. Sattentau, R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 1994. Probing the structure of the human immunodeficiency virus surface glycoprotein gp120 with a panel of monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 68:469-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore, J. P., and J. Sodroski. 1996. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 70:1863-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore, J. P., R. L. Willey, G. K. Lewis, J. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 1994. Immunological evidence for interactions between the first, second, and fifth conserved domains of the gp120 surface glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:6836-6847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison, H. G., F. Kirchhoff, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1993. Evidence for the cooperation of gp120 amino acids 322 and 448 in SIVmac entry. Virology 195:167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Picard, L., D. A. Wilkinson, A. McKnight, P. W. Gray, J. A. Hoxie, P. R. Clapham, and R. A. Weiss. 1997. Role of the amino-terminal extracellular domain of CXCR-4 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. Virology 231:105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Posner, M. R., T. Hideshima, T. Cannon, M. Mukherjee, K. H. Mayer, and R. A. Byrn. 1991. An IgG human monoclonal antibody that reacts with HIV-1/GP120, inhibits virus binding to cells, and neutralizes infection. J. Immunol. 146:4325-4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rabut, G. E. E., J. A. Konner, F. Kajumo, J. P. Moore, and T. Dragic. 1998. Alanine substitutions of polar and nonpolar residues in the amino-terminal domain of CCR5 differently impair entry of macrophage- and dualtropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:3464-3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rizzuto, C., and J. Sodroski. 2000. Fine definition of a conserved CCR5-binding region on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:741-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzuto, C. D., R. Wyatt, N. Hernandez-Ramos, Y. Sun, P. D. Kwong, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. Sodroski. 1998. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science 280:1949-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ross, T. M., and B. R. Cullen. 1998. The ability of HIV type 1 to use CCR-3 as a coreceptor is controlled by envelope V1/V2 sequences acting in conjunction with a CCR-5 tropic V3 loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7682-7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakaida, H., T. Hori, A. Yonezawa, A. Sato, Y. Isaka, O. Yoshie, T. Hattori, and T. Uchiyama. 1998. T-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-derived V3 loop peptides directly bind to CXCR-4 and inhibit T-tropic HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 72:9763-9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sattentau, Q. J., and J. P. Moore. 1991. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J. Exp. Med. 174:407-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schuitemaker, H., M. Koot, N. A. Kootstra, M. W. Dercksen, R. E. Y. de Goede, R. P. van Steenwijk, J. M. A. Lange, J. K. M. E. Schattenkerk, F. Miedema, and M. Tersmette. 1992. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus population. J. Virol. 66:1354-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shioda, T., J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1992. Small amino acid changes in the V3 hypervariable region of gp120 can affect the T-cell-line and macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9434-9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sodroski, J. G. 1999. HIV-1 entry inhibitors in the side pocket. Cell 99:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Speck, R. F., K. Wehrly, E. J. Platt, R. E. Atchison, I. F. Charo, D. Kabat, B. Chesebro, and M. A. Goldsmith. 1997. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J. Virol. 71:7136-7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stanfield, R., E. Cabezas, A. Satterthwait, E. Stura, A. Profy, and I. Wilson. 1999. Dual conformations for the HIV-1 gp120 V3 loop in complexes with different neutralizing fabs. Struct. Fold. Des. 7:131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tan, K., J. Liu, J. Wang, S. Shen, and M. Lu. 1997. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12303-12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tersmette, M., R. E. Y. de Goede, B. J. Al, I. N. Winkel, R. A. Gruters, H. T. Cuypers, H. G. Huisman, and F. Miedema. 1988. Differential syncytium-inducing capacity of human immunodeficiency virus isolates: frequent detection of syncytium-inducing isolates in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. J. Virol. 62:2026-2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thali, M., J. P. Moore, C. Furman, M. Charles, D. D. Ho, J. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 1993. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J. Virol. 67:3978-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thali, M., U. Olshevsky, C. Furman, D. Gabuzda, M. Posner, and J. Sodroski. 1991. Characterization of a discontinuous human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitope recognized by a broadly reactive neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. J. Virol. 65:6188-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trkola, A., T. Dragic, J. Arthos, J. M. Binley, W. C. Olson, G. P. Allaway, C. Cheng-Mayer, J. Robinson, P. J. Maddon, and J. P. Moore. 1996. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature 384:184-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tugarinov, V., A. Zvi, R. Levy, Y. Hayek, S. Matsushita, and J. Anglister. 2000. NMR structure of an anti-gp120 antibody complex with a V3 peptide reveals a surface important for co-receptor binding. Struct. Fold. Des. 8: 385-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van't Wout, A. B., N. A. Kootstra, G. A. Mulder-Kampinga, N. Albrecht-van Lent, H. J. Scherpbier, J. Veenstra, K. Boer, R. A. Coutinho, F. Miedema, and H. Schuitemaker. 1994. Macrophage-tropic variants initiate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection after sexual, parenteral, and vertical transmission. J. Clin. Investig. 94:2060-2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verrier, F., A. M. Borman, D. Brand, and M. Girard. 1999. Role of the HIV type 1 glycoprotein 120 V3 loop in determining coreceptor usage. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:731-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, W. K., T. Dudek, Y. J. Zhao, H. G. Brumblay, M. Essex, and T. H. Lee. 1998. CCR5 coreceptor utilization involves a highly conserved arginine residue of HIV type 1 gp120. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5740-5745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, W. K., C. N. Lee, T. Dudek, S. Y. Chang, Y. J. Zhao, M. Essex, and T. H. Lee. 2000. Interaction between HIV type 1 glycoprotein 120 and CXCR4 coreceptor involves a highly conserved arginine residue in hypervariable region 3. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1821-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang, Z. X., J. F. Berson, T. Y. Zhang, Y. H. Cen, Y. Sun, M. Sharron, Z. H. Lu, and S. C. Peiper. 1998. CXCR4 sequences involved in coreceptor determination of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 tropism. Unmasking of activity with M-tropic Env glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15007-15015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1997. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387:426-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu, L., N. P. Gerard, R. Wyatt, H. Choe, C. Parolin, N. Ruffing, A. Borsetti, A. A. Cardoso, E. Desjardin, W. Newman, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature 384:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu, L., W. A. Paxton, N. Kassam, N. Ruffing, J. B. Rottman, N. Sullivan, H. Choe, J. Sodroski, W. Newman, R. A. Koup, and C. R. Mackay. 1997. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 185:1681-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wyatt, R., P. D. Kwong, E. Desjardins, R. W. Sweet, J. Robinson, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. G. Sodroski. 1998. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature 393:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wyatt, R., J. Moore, M. Accola, E. Desjardin, J. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 1995. Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J. Virol. 69:5723-5733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wyatt, R., and J. Sodroski. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou, H., and H. H. Tai. 2000. Expression and functional characterization of mutant human CXCR4 in insect cells: role of cysteinyl and negatively charged residues in ligand binding. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 373:211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu, T., H. Mo, N. Wang, D. S. Nam, Y. Cao, R. A. Koup, and D. D. Ho. 1993. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 patients with primary infection. Science 261:1179-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]