Abstract

In this article, we present the use of micron-sized lipid domains, patterned onto planar substrates and within microfluidic channels, to assay the binding of bacterial toxins via total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. The lipid domains were patterned using a polymer lift-off technique and consisted of ganglioside-populated distearoylphosphatidylcholine:cholesterol supported lipid bilayers (SLBs). Lipid patterns were formed on the substrates by vesicle fusion followed by polymer lift-off, which revealed micron-sized SLBs containing either ganglioside GT1b or GM1. The ganglioside-populated SLB arrays were then exposed to either cholera toxin B subunit or tetanus toxin C fragment. Binding was assayed on planar substrates by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy down to 100 pM concentration for cholera toxin subunit B and 10 nM for tetanus toxin fragment C. Apparent binding constants extracted from three different models applied to the binding curves suggest that binding of a protein to a lipid-based receptor is influenced by the microenvironment of the SLB and the substrate on which the bilayer is formed. Patterning of SLBs inside microfluidic channels also allowed the preparation of lipid domains with different compositions on a single device. Arrays within microfluidic channels were used to achieve segregation and selective binding from a binary mixture of the toxin fragments in one device. The binding and segregation within the microfluidic channels was assayed with epifluorescence as proof of concept. We propose that the method used for patterning the lipid microarrays on planar substrates and within microfluidic channels can be easily adapted to proteins or nucleic acids and can be used for biosensor applications and cell stimulation assays under different flow conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Specific recognition and binding form the basis of many biological assays such as immunoassays and DNA microarrays. A common feature of all arrayed assays is the requirement of a patterning method that reduces cross-contamination between patterned species while retaining the flexibility to incubate the array with complex mixtures of binding agents. Another desired feature of the patterning procedure is the possibility of reducing nonspecifically bound biomolecules that can increase noise and hinder detection at low analyte concentrations. Patterning arrays of biomolecules on planar substrates and within microfluidic channels with polymer lift-off can provide desired features for biosensing assays and for the study of interactions between surface patterned receptors and target analytes. Patterning arrays within channels can also exploit the advantages of microfluidic devices and offer the opportunity of integrating on-chip detection schemes, with areas of detection confined to the patterned arrays, and control areas defined by the surrounding environment of the patterned biomolecules. Furthermore, biomolecules confined to specific areas within the microfluidic channel can serve as concentration loci by increasing the local density of receptor molecules, and by providing a suitable microenvironment that enhances the avidity of target molecules to their receptors, thus enhancing the detection at low sample concentrations (1,2).

In detection of protein analytes the most commonly used receptors are other soluble proteins or small molecules. This is despite the fact that ∼30% of the genome codes for membrane proteins and many of the receptors in a cell are membrane components. The limited use of membrane receptors such as membrane proteins or lipids has been due to their limited solubility in water. Supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) have received considerable attention in recent years for their intrinsic properties related to biological systems. They offer the possibility to present lipids, carbohydrate-derivatized lipids, or transmembrane proteins in an environment similar to that encountered in cells. SLBs have been previously used for the study of cell activation (3), toxin detection (4), and as membrane (5,6) and membrane protein arrays (7). Patterning of SLBs has been accomplished in the past by a variety of methods, including quill-pin spotting (4), microcontact printing (5), barrier separation (6), microcontact displacement (8), and microfluidic networks (9–11). Nevertheless, these methods have limitations in the feature size that can be obtained when applied to lipids, cannot control the spreading of lipid bilayers without the use of a secondary blocking agent, or are cumbersome. Our group has previously shown the possibility and advantages of patterning biomolecules with a polymer lift-off technique (3,12,13). This lift-off technique obviates the need for etched barriers for domain formation. The polymer itself acts as a natural barrier delimiting the SLBs, and allows the creation of individual micron-sized domains. Furthermore, the removal of the polymer does not cause lipid bilayer spreading or deformation of the patterned features even after prolonged storage.

An important possible application of patterned SLBs is to detect proteins that attach to or interact with lipid-soluble receptors and to elucidate their binding characteristics (14). Examples of such proteins are bacterial toxins, which are usually targeted to specific components present at the surface of cell membranes. Gangliosides, a family of negatively charged ceramide-based glycolipids with one or more sialic residues, are membrane-imbedded receptors that several bacterial toxins recognize and bind to to infect the host cell (15). Cholera toxin is an oligomeric protein produced by Vibrio cholera. Its B subunit (CTB) is a 12-kDa domain of cholera toxin that binds in pentamers to the intestinal cell surface via five identical gangliosides GM1 (16). Similarly, tetanus neurotoxin released by the bacteria Clostridium tetanii binds to gangliosides present on the surface of neural cells (17). Tetanus toxin binds to gangliosides of the G1b series, binding with higher affinity to ganglioside GT1b (15). The carboxyl terminus of tetanus toxin (fragment C (TTC), 57 kDa) is responsible for binding to ganglioside GT1b. Cholera and tetanus toxins have been previously used as model systems for toxin detection since the isolated recombinant fragments responsible for binding to the ganglioside moieties are innocuous. Schemes developed to detect bacterial toxins that interact with gangliosides include liposome fluoroimmunoassays (18,19), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (1, 20,21), microarray scanners (4), and quartz crystal microbalances (22).

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) is one of the preferred techniques used for the study of binding events happening at surface-fluid interfaces. In TIRFM, a laser beam is internally reflected on the surface-fluid interface, and the evanescent field is used to excite fluorescent molecules located close to the interface, where the penetration depth (typically 45–200 nm) is determined by the laser and optics used. The illuminating field decays exponentially in the z axis, thus confining the excitation volume and selectively imaging surface-bound fluorescent molecules. The theoretical basis and applications of objective-based TIRFM have been discussed in the literature (23). TIRFM has been previously used in combination with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) to study binding kinetics of a membrane-imbedded protein receptor (14). In such a study, TIRFM was used to image the receptor-populated SLB, eliminating any background fluorescence, and FCS was used to extract the kinetic parameters of the binding. This suggests that TIRFM is a suitable technique for the imaging of bacterial toxin binding to ganglioside-populated SLBs.

In this article, we present the use of micron-sized lipid arrays to evaluate the binding constants of bacterial toxins on a solid support. Patterned arrays contained on planar substrates and within microfluidic channels were used as binding elements to selectively capture fluorescently labeled CTB and TTC fragments from solution. Concentrations of 1 nM for CTB and 100 nM for TTC could be detected by TIRFM as distinct patterns determined by the lipid domains. Lower concentrations could be resolved as individual fluorescent patches. Fitting the binding curves obtained from the fluorescence data allowed the determination of binding constants for both bacterial toxins. Comparison of the obtained binding constants with previously published data suggests that the avidity of the lipid-based receptors is strongly influenced by the composition of the SLB and by the substrate on which the bilayer is formed. Also, to demonstrate long-term stability, the patterned substrates were stored at 4°C for up to a year. Although the possible expansion of the SLBs was not fully characterized, no noticeable deformation of the patterned shape or loss of ganglioside functionality was observed. Finally, by using the polymer lift-off technique to pattern lipid arrays within microfluidic channels, it is shown that two toxin fragments can be segregated from a mixed solution and bound to their corresponding receptors with high specificity. All these characteristics suggest that this approach is suitable for use in biosensor applications or cell stimulation studies and can be extended to protein or DNA microarray patterning. Patterning arrays of biomolecules within channels provides on-chip negative controls side by side with sensing areas, allowing facile detection of positive signal with a local background reference. We propose that the patterns in the microfluidic channels can be integrated with existing sensing techniques such as TIRFM, SPR, diffraction sensing, electrochemical signaling, and voltammetry, to allow on-chip detection with the advantage of multiplexing capabilities provided by microfluidic integration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Gangliosides GT1b and GM1; cholesterol; lipid L-α-distearophosphatidylcholine (DSPC); and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Labeled fluorescein-dehexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoetanolamine (DHPE-FITC) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). To avoid hazards due to exposure we used commercially available recombinant toxin fragments. Cholera toxin B subunit was obtained from Sigma Chemical and tetanus toxin C fragment was obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Di-para-xylylene (Parylene-C) was obtained from Specialty Coating Systems (Indianapolis, IN). Sylgard 184 poly-dimethyl siloxane elastomer and hardener kit was obtained from Down Corning (Midland, MI).

Lipid vesicle preparation

The preparation of GT1b and GM1 containing liposomes was done by extrusion as reported elsewhere (18). Liposomes containing gangliosides GT1b or GM1 had a DSPC/cholesterol/GT1b-GM1 molar composition of 47.5:47.5:5. Fluorescently labeled lipid mixtures had a DSPC/cholesterol/GT1b/DHPE-FITC molar composition of 45:45:5:5. All lipids were resuspended in 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4. Mean vesicle diameter after extrusion process was ∼100 nm. Liposome solutions were kept in storage at 4°C and bath-sonicated in a Branson 2510 Sonicator for 20 min before incubation.

Substrate fabrication

Two types of substrates were prepared: planar substrates for toxin binding studies with TIRFM, and microfluidic substrates for multiplexed detection of two bacterial toxins.

Planar substrate

A uniform 1.5-μm coating of Parylene-C was vapor-deposited on silicon or 100 μm high refractive index (n = 1.81) glass wafers in a PDS-2010 Labcoater 2 Parylene deposition system (Specialty Coating Systems, Indianapolis, IN). SPR 955CM-2.1 positive photoresist was spun on the parylene-coated wafers at 4000 rpm for 45 s to obtain a nominal resist thickness of 1.8 μm and prebaked at 90°C. Photolithography was performed using a GCA (Escondido, CA) 6300 DSW 10× i-line (365-nm) stepper. The exposed photoresist was developed in AZ300-MIF developer for 60 s, rinsed in deionized water, and then dried under a nitrogen stream. Exposed regions of the parylene film were reactive ion etched (RIE) in an oxygen plasma chamber. Residual photoresist was removed by washing successively with acetone and isopropanol.

Microfluidic substrate

The following process was performed to create channels etched into silicon. P-20 adhesion promoter was spun onto a blank wafer at 3000 rpm for 45 s. Afterward, SPR 1813 photoresist was spun at 4000 rpm for 45 s to obtain a nominal resist thickness of 1.3 μm and prebaked at 90°C. Photolithography was performed on the wafer using a GCA 6300 DSW 5× g-line (436-nm) stepper. The exposed photoresist was developed in AZ300-MIF developer for 60 s, rinsed with deionized water, and then dried under a nitrogen stream. The exposed regions of the silicon were etched in a Unaxis SLR 770 inductively coupled plasma/reactive ion etcher (Bosch fluorine process) to obtain an etch depth of 10 μm. Residual photoresist was removed by washing successively with acetone and isopropanol, and stripped in a GaSonics, Aura 1000, Downstream Photoresist Stripper. Channels 100 μm wide, 3 mm long, and 10 μm deep were obtained. After the fabrication of the channels, a uniform 1.5-μm coat of Parylene-C was vapor deposited on the whole wafer. Photolithography was performed as described above to place patterns within the channels. Before incubation with biological materials all substrates were oxygen plasma treated for 2 min in a Harrick (Ossining, NY) PDC-001 Plasma Cleaner to oxidize the silicon. A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) slab was created to help seal the etched channels.

Patterning of SLBs and characterization

Liposomes containing GM1 and GT1b gangliosides were bath-applied on planar substrates or flowed into the respective channels in microfluidic substrates, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C to allow vesicle fusion and lipid bilayer formation. Excess lipids were removed with consecutive buffer washes. The sealing PDMS slab was removed after this step from the multiple-composition SLB substrates. Parylene was lifted off, revealing the lipid bilayer patterns containing toxin-specific ganglioside receptors. Solutions containing CTB and TTC fragments were bath-applied onto the patterned lipids and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Excess protein was removed by consecutive buffer washes.

Lipid vesicle fusion and formation of SLBs was characterized by using epifluorescence, fluid-cell tapping mode atomic force microscopy (FC-TMAFM) and fluorescence photobleach recovery (FPR). Epifluorescence images of patterned lipids were obtained using an Olympus AX70 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) using a 40× physiological objective, NA 0.8, and a RT color spot camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Edinburgh, UK). FC-TMAFM micrographs were obtained using a Dimension 3000 scanning probe microscope with v-shaped contact-mode silicon nitride cantilevers; force constant 0.58 N/m (Veeco Instruments, Woodbury, NY). Scan rates used for imaging were 0.5–3 Hz with a driving frequency of 4.293 kHz and amplitude of 2500 mV. AFM images were analyzed and processed with WSxM freeware (www.nanotec.es). FPR data from Alexa 488-labeled TTC bound to GT1b-containing domains was obtained with two-photon excitation using a lab-built multiphoton system described elsewhere (13). A 100-nm radius spot was photobleached by a 10-μs pulse at 900 nm (100-fs pulse width), using a 60×/0.9 NA water immersion lens. Fluorescence recovery was recorded for 80 ms, and each FPR curve was averaged over 50 traces. Data was fit using a single component Fickian model for two-dimensional diffusion and two-photon bleaching (24,25). The diffusion coefficient (D) was determined using a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm.

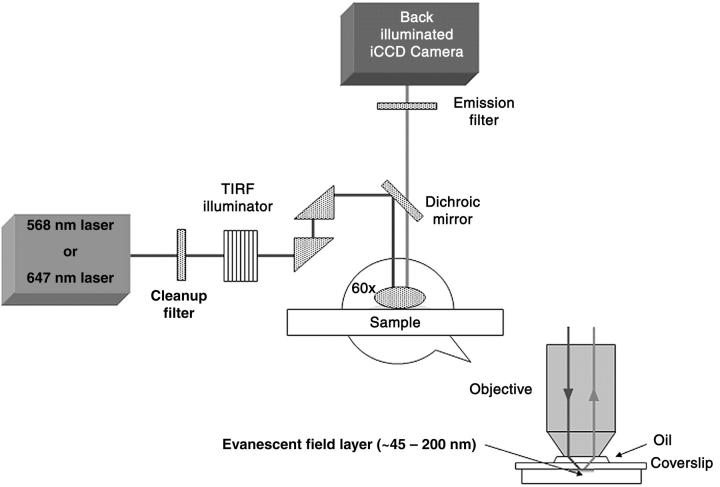

TIRFM setup

Toxins bound to ganglioside-containing SLB arrays were imaged by TIRFM using a lab-built setup (Fig. 1). All images were obtained using a modified commercially available Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope (Olympus), integrated with a Prior ProScan stage (Prior Scientific, Rockland, MA) and an Argon-krypton mixed gas tunable laser (Melles Griot Laser Group, Carlsbad, CA). The laser beam was precisely coupled to an optical fiber, which on the other end was coupled to an IX2 total internal reflection illumination system (Olympus). The illuminator allowed for precise control of the depth of the evanescent field by varying the angle of incidence α of the laser beam at the back aperture of the objective. The evanescent field could be varied between 45 and 200 nm. Upon entering the main body of the microscope, a dichroic mirror (ranging from 480 to 660 nm) reflected the laser light toward the sample, where an Olympus PLAPON 60× OTIRFM coverslip-corrected oil immersion objective or an Olympus 100× APO-TIRFM oil immersion objective was used to focus the laser beam for excitation of and collection of fluorescence from the sample. Light collected with the objective was directed back through the dichroic mirror to the emission filter. The fluorescence signal was then directed to an ICCD camera (Cascade:512B, PhotoMetrics, Allentown, NJ), capable of single fluorophore detection.

FIGURE 1.

Objective-based total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy setup. Samples were prepared either directly on a 100-μm glass or on silicon substrates and then mounted on a 170-μm glass coverslip.

For TIRFM illumination, the light entering the microscope is slightly shifted so that it shines on the specimen at an angle α from the normal. As the light illuminates the specimen, it is internally reflected, creating an evanescent field above the substrate surface, with a penetration given by

|

(1) |

where d is the penetration depth, λ0 is the laser wavelength, α is the incidence angle, n1 is the refractive index of water or oil immersion oil, and n2 is the refractive index of glass (23). For the setup described above, the values used were λ0 = 488 or 647, α = 60–80°, n1 = 1.518 or 1.78, and n2 = 1.433 or 1.81 (for 100× TIRFM objective). With these numbers the penetration depth for our setup was calculated to be between 45 and 200 nm.

Binding assays

Binding assays were performed on planar substrates. Decreasing concentrations of the toxin fragments were used and digital images taken until no discernible fluorescence could be recorded. Image analysis was performed on the recorded digital images using an algorithm written in Matlab that calculates signal and background values of areas cropped from the digital images. The size of the cropped image was selected to minimize uneven illumination introduced by the TIRFM setup. Signal and background were computed as averages from 20 images at each concentration. The resulting binding curves were fit to the following three models: the logistic model,

|

(2) |

where F is the fluorescence intensity, x is the toxin concentration, A1 and A2 are the asymptotic values as x→0 and x→∞, K0 is the half dissociation constant, and p is a parameter related to the slope of the binding curve (18); the Michaelis-Menten model,

|

(3) |

where F is the fluorescence intensity, x is the toxin concentration, Vmax is the maximum binding rate, and Km is the half dissociation constant; and the Hill-Waud model,

|

(4) |

where F is the fluorescence intensity, Vmax is the maximum binding rate, KH is the half dissociation constant, and n is the Hill coefficient of cooperativity (26). These models were used to determine the best fit and to evaluate binding cooperativity.

Nonspecific binding assays were performed by using FITC-labeled BSA and recording fluorescence intensity by epifluorescence. Toxin fragments were also incubated with both gangliosides to assess cross-reactivity between receptors. For segregation of the toxins from a binary mixture, the pH was optimized to find the range at which both toxin fragments would bind simultaneously to their specific receptors, minimizing nonspecific binding. Once the suitable pH was determined, different concentrations of toxin fragment mixtures containing both TTC and CTB in equal amounts were prepared and incubated with the lipid microarrays formed within microfluidic channels. Toxin fragments bound to their respective ganglioside domains within the channels were imaged by epifluorescence.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Substrate fabrication and SLB patterning

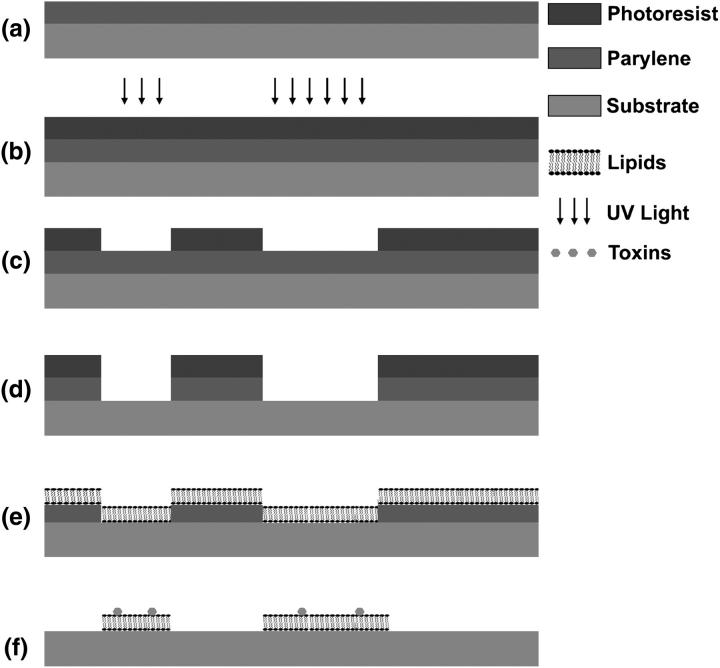

Planar substrates, fabricated with polymer deposition and etching (Fig. 2), were used to pattern SLBs into 0.5- to 76-μm features. Lipid vesicles were incubated with the oxidized substrates and allowed to form SLBs in the exposed areas. When incubating the liposome solution on the planar substrates, we observed a change in hydrophilicity of the Parylene coating after plasma treatment, and calculated it to correspond to a change in surface free energy from the critical value of 20 J/m2 to ∼65 J/m2. This change in surface free energy resulted from the inclusion of oxygen into the polymer coating, roughening of the surface, and generation of carbonyl groups on the surface, and agrees with data published by Lee and colleagues (27) regarding the surface treatment of Parylene. The change in the surface properties resulted in a constraint where different lipid-type domains could only be obtained if the separation between spots of the lipid vesicle solution was large enough to avoid mixing or PDMS wells were used to confine the droplets (images not shown). This amounted to spotting in a similar fashion to that used for common DNA microarrays with the added restriction that patterned lipids had to remain in an aqueous environment.

FIGURE 2.

Patterning procedure for the deposition of supported lipid bilayers on planar substrates with polymer lift off. (a) Polymer film is deposited on a silicon substrate by vapor deposition. (b) Photoresist is spun on the coated substrate and exposed with ultraviolet light. (c) Photoresist is developed, and removed in areas where it has been exposed. (d) Polymer is etched away by oxygen plasma in the areas where photoresist was removed. Micron-sized features of exposed silicon substrate are left after photoresist removal. (e) Substrates are oxidized and incubated with lipid vesicles, which fuse down and form bilayers. (f) Polymer is peeled off and ganglioside-populated lipid bilayer patterns are left behind. Subsequent incubation with bacterial toxins specific to such receptors yields toxin binding to patterned areas.

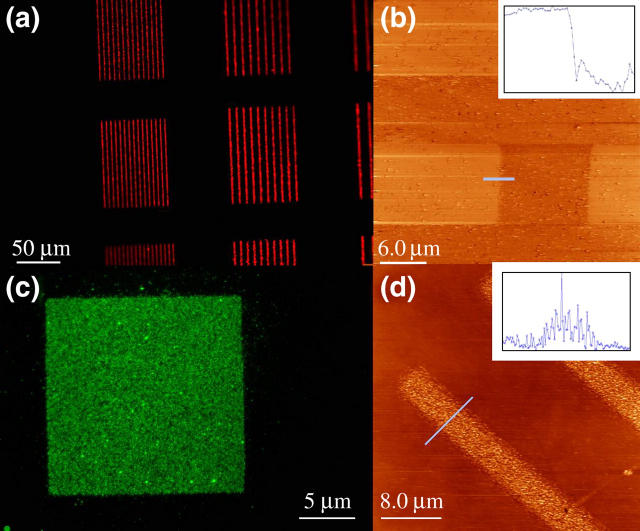

Planar substrates were then used to characterize the patterned lipids for SLB formation by epifluorescence, FC-TMAFM, and fluorescence photobleach recovery (FPR). Epifluorescence images taken after polymer lift-off showed lipid patterns (Fig. 3, a and c), but did not confirm the formation of a bilayer. FC-TMAFM was used to further characterize the patterned lipids. Atomic force micrographs showed marked topographical distinctions between the lipid mixtures incubated at room temperature and those incubated at 37°C. This was expected because the DSPC/cholesterol mixture (50:50 molar ratio) has a transition temperature close to 37°C. The lower transition temperature results from the interaction between DSPC and cholesterol as the content of the latter is increased (28,29), as well as from the inclusion of a significant percentage of ganglioside receptors. Samples containing DSPC and cholesterol mixed with gangliosides GM1 or GT1b that were incubated above the transition temperature formed bilayers with heights of ∼7 nm (Fig. 3 b). On the other hand, those incubated at room temperature showed vesicle deposition on the substrate surface with heights going from tens of nanometers to >100 nm, but no bilayer formation (Fig. 3 d). The height obtained for the bilayers is consistent with those reported in the literature (30–32) for bilayers and mixtures containing a uniform distribution of GM1 in phosphocholine domains. Further confirmation of lipid bilayer formation was performed with FPR. Measurements obtained from lipid mixtures incubated at 37°C, and taken at the center of patterns with different sizes and shapes yielded a mean diffusion coefficient D = 6 ± 1 × 10−8 cm2/s, consistent with previously reported diffusion coefficients for fluid SLBs (13), but slightly higher than the reported values for pure DSPC/cholesterol vesicles (29). No significant difference was obtained in diffusion coefficients for different pattern size or shape. Although this diffusion coefficient is slightly higher than that expected for a pure DSPC/cholesterol mixture, the variation can be attributed to the inclusion of the ganglioside (5% molar ratio) in the bilayer.

FIGURE 3.

Epifluorescence and TMAFM images were taken from two different incubation conditions for the lipid vesicles to assess SLB formation. (a and b) Images of an SLB formed by vesicles containing DSPC and gangliosides, incubated at 37°C. (Inset) Scan corresponding to blue line in picture. Mean height of bilayer above the substrate is ∼7 nm. (c and d) Images of adhered vesicles containing DSPC and gangliosides incubated at room temperature. Vesicles do not fuse completely to form a bilayer. (Inset) Scan corresponding to blue line in picture, maximum height 40 nm.

The obtained SLB patterns showed no significant deformation after polymer lift-off and storage. Fluorescently labeled lipids and lipids containing ganglioside-bound toxin fragments retained the patterned shape after storage at 4°C for 1 year, showing that under such storing conditions no spreading or membrane desorption occurs. SLBs in storage can expand slightly as previously reported by Cremer (33), but no noticeable size increase could be detected with our setup. It has also been reported that SLBs patterned with PDMS microfluidic channels form finger-like extensions outside the patterned area when the PDMS mold has been removed unless a secondary blocking agent is added (11). We did not observe such behavior after polymer lift-off. The lack of spreading and membrane deformation on silicon substrates can be attributed to the difference in surface characteristics that arises between the areas of the silicon substrate that have been exposed to oxygen plasma and those that were not because they were protected by the polymer coating. Such a difference acts as a confinement agent that gives the patterned bilayers further stability against desorption when stored under the appropriate conditions.

Binding assays

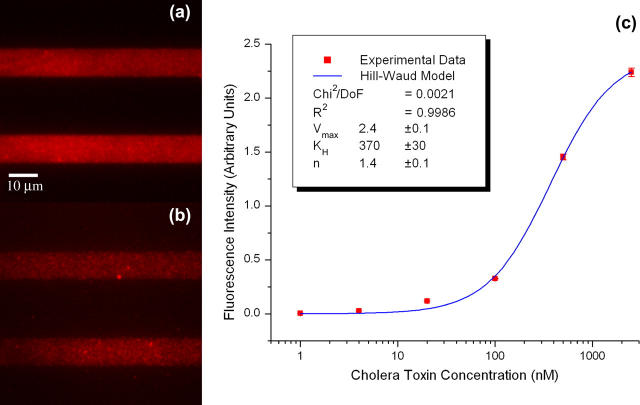

Binding assays were performed on planar substrates to determine the binding constants of both CTB and TTC, as well as to establish the limit of detection and binding specificity for the SLB arrays. Concentrations from 10 μM to 100 pM were used in successive dilutions and TIRFM images were taken to assess the amount of toxin binding to the patterned SLBs under equilibrium conditions (Figs. 4, a and b, for CTB, and 5, a and b, for TTC). Twenty images were analyzed for each concentration and the average fluorescence intensity for the signal and background were computed. The fluorescence images obtained reflected the number of ganglioside receptors within the SLB that are bound to the bacterial toxin. In all cases the images were cropped to eliminate effects from nonuniform illumination resulting from the optics used for TIRFM imaging. The images were also taken minimizing the exposure to light to avoid photobleaching effects. The limit of detection for these assays was defined as the minimum concentration where a recognizable pattern could be reconstructed by bound events. For CTB, the limit of detection was found to be 1 nM, whereas for TTC it was found to be 100 nM. Lower concentrations than these could be detected down to the picomolar range, not as recognizable patterns but as isolated binding events (see Fig. 6 for isolated CTB binding events). This suggests that at lower concentrations binding events can be studied as single molecules and the on/off rates calculated to extract the association/dissociation constants.

FIGURE 4.

Binding assays for CTB. Fluorescence images of CTB incubated with patterned SLBs containing GM1 receptors at (a) 2500 and (b) 100 nM. (c) Intensity versus concentration plot for successive dilutions. (Inset) Hill-Waud model fit parameters.

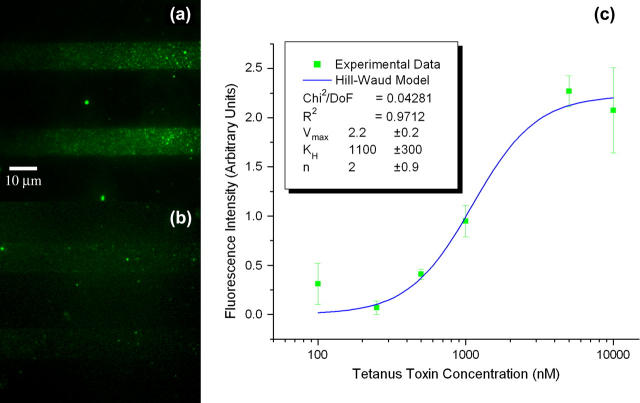

FIGURE 5.

Binding assays for TTC. Fluorescence images of TTC incubated with patterned SLBs containing GT1b receptors at (a) 10,000 and (b) 250 nM. (c) Intensity versus concentration plot for successive dilutions. (Inset) Hill-Waud model fit parameters.

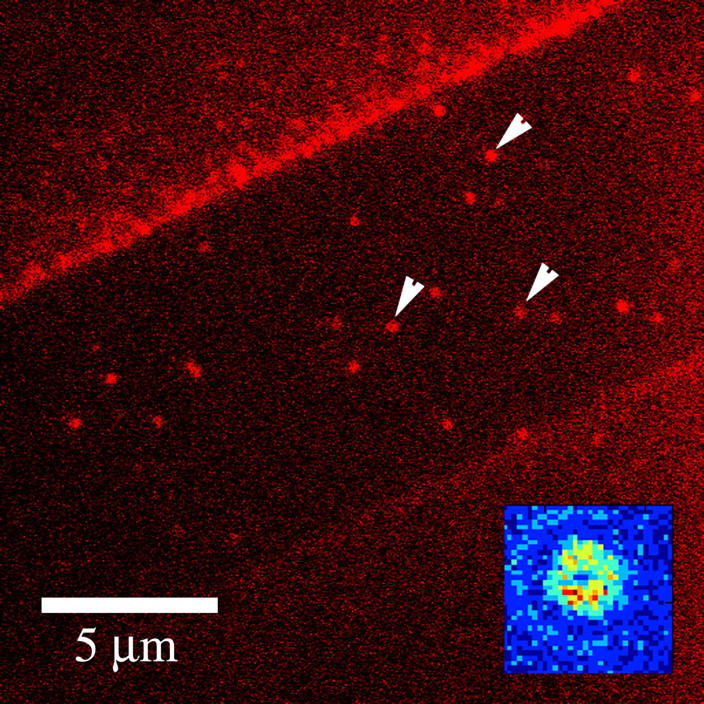

FIGURE 6.

Isolated binding events for CTB observed via TIRFM. Binding events (arrows) observed in patterned SLB (strip in center, 10 μm wide) without removal of polymer coating (brighter flanking regions). (Inset) False color intensity plot of a single bound event.

Plots of the observed average fluorescence intensity versus concentration (Figs. 4 c and 5 c) yielded binding curves that allowed the extraction of apparent dissociation constants. For bacterial toxin binding several fitting models have been proposed. Singh et al. (18) used a logistic fit in a fluorescent liposome assay to extract apparent dissociation constants of several bacterial toxins to ganglioside receptors in DSPC/cholesterol lipid mixtures. The logistic model provides a sigmoidal function with asymptotic behavior and four degrees of freedom, which allow it to fit most binding curves but do not give much insight as to the biological mechanisms underlying the binding events. On the other hand, Lencer and collaborators (26) used both Michaelis-Menten and Hill-Waud models as fitting functions to extract constants for CTB binding to GM1 present at the intestinal microvillus membrane in rats. Michaelis-Menten kinetics assumes one-to-one binding between the toxins and their receptors, thus ignoring any cooperativity. Use of this model can be justified if the receptor density is in excess of the applied toxin, and the cooperativity of binding subunits is small. On the other hand, the Hill-Waud model takes into account the binding cooperativity through the introduction of the Hill coefficient n, which can serve to estimate how strong the cooperative binding is between subunits. In the case of CTB, it has been shown that it binds cooperatively in pentameric form to five identical GM1 gangliosides (16), whereas TTC has been observed to bind in one-to-one fashion to GT1b (15). This would suggest that a Hill-Waud model would more accurately describe CTB binding, whereas either Hill-Waud or Michaelis-Menten models would serve to describe TTC binding. All three models were used to fit the binding curves for both toxins. The logistic fit was found to yield better fits in all cases (R2 = 0.9992 for CTB, and R2 = 0.9960 for TTC) because of the added degrees of freedom, whereas the other two models yielded fits with slightly decreased accuracy (Hill-Waud model, R2 = 0.9985 for CTB and R2 = 0.9712 for TTC; Michaelis-Menten model, R2 = 0.9941 for CTB and R2 = 0.9440 for TTC). We expected that from the biological perspective, a Hill-Waud model would be more accurate to describe the behavior of both bacterial toxins, because it accounts for the cooperative binding of CTB and in the case of TTC it should reduce to Michaelis-Menten kinetics as the Hill coefficient tends to 1. We found that CTB agreed with this prediction and the Hill coefficient obtained from the fit of the fluorescent data was 1.4 ± 0.1, which matches data published on the in vivo study of binding kinetics of CTB to intestinal microvillus membrane (26). The obtained Hill coefficient denotes positive cooperativity between the subunits of the cholera toxin. This result is expected from the pentameric nature of CTB. On the other hand, TTC did not meet the same expectations, as the results obtained from the Hill-Waud model did not reduce to the Michaelis-Menten fit. This is explained by the large error at the lower concentration data point, which yielded a large uncertainty in the Hill coefficient.

The apparent dissociation constants obtained from the fluorescence intensity of the bound bacterial toxins at different concentrations were calculated from all three models and were: 370 ± 30 nM for CTB and 1.1 ± 0.3 μM for TTC as calculated from the Hill-Waud model; 490 ± 80 nM for CTB and 2.0 ± 0.9 μM for TTC as calculated from the Michaelis-Menten model, and 370 ± 30 nM for CTB and 1.2 ± 0.2 μM for TTC as calculated from the logistic model. Notice that the values from the logistic and Hill-Waud models agree, and are essentially the same to within the experimental error, whereas the Michaelis-Menten values for both toxins yielded greater errors and are significantly different. Overall, the extracted values and uncertainties follow the expected accuracy from each of the three models, where Hill-Waud and logistic models agree closely, whereas the Michaelis-Menten is not as accurate for CTB, but should be for TTC. This discrepancy is again attributed to the large error at the lowest concentration detected for the TTC assays. We found that the dissociation constants of previously published data for CTB and TTC have a very wide range of values. Lencer (26) reports an apparent dissociation constant of 200–400 pM for CTB binding to rat intestinal microvillus membrane assayed with radiolabeling. Masserini (34) reports a value of 10 nM for CTB binding to GM1 on rat glioma cells assayed with isothermal titration calorimetry. Kuziemko (1) reports a value of 5 pM in studies of CTB binding to a supported lipid monolayer of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-phosphocholine (POPC)/GM1 (95:5 molar ratio) assayed via SPR. Also using SPR, but using liposome-anchored gangliosides, MacKenzie (20) reports a value of 1 nM. Janshoff (22) reports a value of 5 nM for CTB binding to GM1 imbedded in POPC bilayers assayed by quartz crystal microbalance frequency shift. Singh (18) reports a value of 6 nM for the apparent dissociation constant as obtained from a liposome fluoroimmunoassay where GM1 were contained in liposomes of DSPC/cholesterol/rhodamine-DHPE (42.5:42.5:10 molar ratio). For TTC, Janshoff (22) reports an apparent binding constant of 500 nM for binding to GT1b imbedded in POPC bilayers assayed by quartz crystal microbalance. MacKenzie (20) reports a value of 170 nM for binding to liposome-anchored GT1b gangliosides through SPR. Singh (18) reports a value of 8 nM as obtained from liposome fluoroimmunoassays where GT1b gangliosides were contained in liposomes of DSPC/cholesterol/rhodamine-DHPE (42.5:42.5:10 molar ratio). Krell (35), using microcalorimetry titration on ganglioside micelles, finds a biphasic binding behavior, where a strong binding occurs with an apparent dissociation constant of 55 nM and weaker binding occurs with an apparent dissociation constant of 666 nM. The values we found are higher than the reported values for dissociation constants from bacterial toxins, especially if compared to those reported for studies performed with SLBs. Yet, the tendency of TTC to have a dissociation constant two orders of magnitude higher than that of CTB, which has been observed in most experimental trials of these two toxins, is preserved in our system. From reviewing the available literature and comparing the different reported dissociation constants we find that the variation in the reported values could be associated, to a certain extent, with the experimental setup. This may be a result of the microenvironment resulting from the lipid composition of the mono- or bilayer, liposome, or micelle, the presence or absence of a supporting substrate, hindrance introduced by the attached fluorophores on the bacterial toxins, and, hence, the avidity of the ganglioside receptors embedded in the membrane for the toxins. Previous fluorescent liposome assays performed with a similar lipid mixture (DSPC:cholesterol:rhodamine-DHPE:GM1, 42.5:42.5:10:5 molar ratio (18)) would be the closest comparison to the results obtained with our TIRFM imaging. We propose that the difference observed between the reported values for the binding constants is strongly influenced by the membrane or liposome composition and the substrate that serves as the support. This in turn directly affects the microenvironment that the target analytes encounter and either enhances or reduces the avidity of the ganglioside receptors for the bacterial toxins, as has been previously reported by Kuziemko (1). To elucidate the effect that phospholipid headgroups, substrate charge, and ionic strength of the solution have on the binding characteristics of these toxins, it is necessary to conduct a characterization of the ganglioside avidity as a function of the membrane composition and the supporting substrate. This is beyond the scope of our work but can be addressed in a subsequent study.

Cross-reactivity assays were run incubating the toxin fragments with mismatched gangliosides. CTB exhibited 100-fold stronger binding to ganglioside GM1 than to GT1b when incubated at a concentration of 5 μM. Similarly, TTC exhibited a 10-fold stronger binding to ganglioside GT1b than to GM1 when incubated at a concentration of 5 μM. Binding observed in the cross-reactivity assays was higher than the nonspecific binding of these toxin fragments to a bare silicon substrate. Low cross-reactivity was expected as it has been shown that the binding specificity of the toxins is related to the number of sialic residues present in each of the gangliosides (17). Nonspecific binding assays were also performed on both types of ganglioside-containing domains by incubating them with fluorescently labeled BSA. Weak binding was observed mainly in the areas devoid of lipids, with fluorescence intensity values below those observed for the cross-reactivity assays. The observed binding behavior is explained, as BSA readily adsorbs onto silicon surfaces and is used frequently as a blocker for nonspecific adhesion of analytes.

Patterning within microfluidic channels

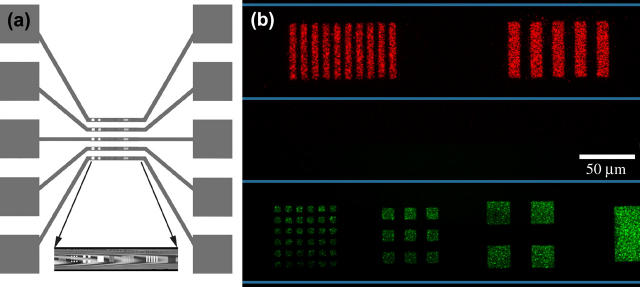

A microfluidic approach was used to deposit SLBs of different compositions in separate channels of a Si microchip as shown in Fig. 7 a. Silicon substrates with etched trenches were coated with Parylene, and 2- to 50-μm features were etched into the polymer. A slab of PDMS containing microfluidic connections was attached to the top of the device by noncovalent surface adhesion. This cover gave a seal to prevent cross-contamination between the channels filled with different lipid compositions and the flexibility to remove it after lipid patterning for subsequent incubation with targeted analytes. Lipid vesicle solutions containing either ganglioside GM1 or GT1b were delivered into the reservoirs and flowed into each channel. The total volume needed to fill a single reservoir and channel was ∼150 nL. In this way, microarrays of SLBs containing different gangliosides were obtained on a single chip.

FIGURE 7.

SLB arrays within microfluidic channels. (a) Top view scheme of designed microfluidic trenches and reservoirs (orange) and patterned features at the bottom of these trenches (colored marks in central portion). (Inset) Bright field image of top view of patterned trench. (b) Alexa 594-CTB and Alexa 488-TTC conjugated toxin fragments segregated from a binary mixture and bound to SLB arrays in the microfluidic channels (the channel boundary is represented by the thin horizontal lines).

The microfluidic substrates containing patterned SLB arrays with different lipid compositions were used to segregate toxin fragments from binary mixtures. The mixture pH was optimized to 6.5 to allow specific fragment binding to the corresponding gangliosides and segregation from the binary mixture (Fig. 7 b), with low nonspecific binding. Incubation of the patterned microfluidic substrates with a single toxin fragment concentrations yielded results similar to those obtained with planar substrates. With this experiment we show proof of concept of a method for patterning functional SLBs within microfluidic channels.

CONCLUSIONS

We have shown that ganglioside-populated SLB arrays can be patterned on planar substrates and within microfluidic channels with polymer lift-off. The patterned SLBs, once the polymer is removed, are stable and functional over a long period of time when stored under the appropriate conditions. We have found that the diffusion coefficient of the patterned bilayers is 6 × 10−8 cm2/s. We have also shown that the bilayers are functional and can be used to detect bacterial toxins. Imaging bound events with TIRFM allowed the extraction of kinetic data from the fluorescence resulting from concentration gradient. In this way, apparent dissociation constants of 370 nM and 1.1 μM have been calculated for CTB and TTC, respectively. We have also shown that with TIRFM it is possible to image single fluorescent domains, which could be used in combination with FCS to extract other kinetic parameters, such as on-off rates. After comparing our results with those previously published, we have come to the conclusion that the binding of a bacterial toxin to a ganglioside imbedded in a membrane or liposome is strongly influenced by the lipid composition, toxin labeling, and substrate on which the experiment is conducted. This suggests that a subsequent study should undertake the task of performing experiments to elucidate the impact of each of these factors on bacterial toxin binding. We have also shown that patterning of SLB microarrays in microfluidic channels can be used to segregate toxins from a binary mixture and detect them independently. The technique for patterning SLBs within microfluidic channels can be easily extended to generate protein or DNA patterns. The possibility to pattern arrays in microfluidic channels gives the opportunity of integrating on-chip detection schemes to microfluidic devices, with detection areas confined to the patterned arrays, and to perform cell stimulation studies with different agents in individual channels for a single cell population. This technique extends the advantages of microfluidic devices to biosensing arrays.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. D. McMullen and W. R. Zipfel for FPR assistance.

This work was supported by Sandia National Laboratories under the Campus Executive Program, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and the Nanobiotechnology Center, a Science and Technology Centers program of the National Science Foundation (agreement ECS-9876771).

References

- 1.Kuziemko, G. M., M. Stroh, and R. C. Stevens. 1996. Cholera toxin binding affinity and specificity for gangliosides determined by surface plasmon resonance. Biochemistry 35:6375–6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeung, C., and D. Leckband. 1997. Molecular level characterization of microenvironmental influences on the properties of immobilized proteins. Langmuir. 13:6746–6754. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orth, R. N., M. Wu, D. A. Holowka, H. G. Craighead, and B. A. Baird. 2003. Mast cell activation on patterned lipid bilayers of subcellular dimensions. Langmuir. 19:1599–1605. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang, Y., A. G. Frutos, and J. Lahiri. 2003. Ganglioside microarrays for toxin detection. Langmuir. 19:1500–1505. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovis, J., and S. G. Boxer. 2001. Patterning and composition arrays of supported lipid bilayers by microcontact printing. Langmuir. 17:3400–3405. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groves, J. T., and S. G. Boxer. 2002. Micropattern formation in supported lipid membranes. Acc. Chem. Res. 35:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang, Y., A. G. Frutos, and J. Lahiri. 2002. Membrane protein microarrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:2394–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, T., E. E. Simanek, and P. Cremer. 2000. Creating addressable aqueous microcompartments above solid supported phospholipid bilayers using lithographically patterned poly(dimethylsiloxane) molds. Anal. Chem. 72:2587–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, T., S. Jung, H. Mao, and P. Cremer. 2001. Fabrication of phospholipid bilayer-coated microchannels for on-chip immunoassays. Anal. Chem. 73:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuenneke, S., and A. Janshoff. 2002. Visualization of molecular recognition events on microstructured lipid-membrane compartments by in situ scanning force microscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 1:314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burridge, K. A., M. A. Figa, and J. Y. Wong. 2004. Patterning adjacent supported lipid bilayers of desired composition to investigate receptor-ligand binding under shear flow. Langmuir. 20:10252–10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilic, B., and H. G. Craighead. 2000. Topographical patterning of chemically sensitive biological materials using a polymer-based dry lift off. Biomed. Microdevices. 2:317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orth, R. N., J. Kameoka, W. R. Zipfel, B. Ilic, W. W. Webb, T. G. Clark, and H. G. Craighead. 2003. Creating biological membranes on the micron scale: Forming patterned lipid bilayers using a polymer lift-off technique. Biophys. J. 85:3066–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieto, A. M., R. C. Cush, and N. L. Thompson. 2003. Ligand-receptor kinetics measured by total internal reflection with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 85:3294–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angstrom, J., S. Tenneberg, and K. A. Karlsson. 1994. Delineation and comparison of ganglioside-binding epitopes for the toxins of Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli, and Clostridium tetani: evidence for overlapping epitopes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:11859–11863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merritt, E. A., S. Sarfaty, F. van den Akker, C. L'Hoir, J. A. Martial, and W. G. Hol. 1994. Crystal-structure of cholera toxin B-pentamer bound to receptor GM1 pentasaccharide. Protein Sci. 3:166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herreros, J., and G. Schiavo. 2002. Lipid microdomains are involved in neurospecific binding and internalisation of clostridial neurotoxins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh, A. K., S. H. Harrison, and J. S. Schoeniger. 2000. Gangliosides as receptors for biological toxins: development of sensitive fluoroimmunoassays using ganglioside-bearing liposomes. Anal. Chem. 72:6019–6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn-Yoon, S., T. R. DeCory, A. J. Baeumner, and R. A. Durst. 2003. Ganglioside-liposome immunoassay for the ultrasensitive detection of cholera toxin. Anal. Chem. 75:2256–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKenzie, C. R., T. Hirama, K. K. Lee, E. Altman, and N. M. Young. 1997. Quantitative analysis of bacterial toxin affinity and specificity for glycolipid receptors by surface plasmon resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5533–5538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naimushin, A. N., S. D. Soelberg, D. K. Nguyen, L. Dunlap, D. Bartholomew, J. Elkind, J. Melendez, and C. E. Furlong. 2002. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B at femtomolar levels with a miniature integrated two-channel surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 17:573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janshoff, A., C. Steinem, M. Sieber, A. Baya, M. A. Schmidt, and H. J. Galla. 1997. Quartz crystal microbalance investigation of the interaction of bacterial toxins with ganglioside containing solid supported membranes. Eur. Biophys. J. 26:261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axelrod, D. 2001. Selective imaging of surface fluorescence with very high aperture microscope objectives. J. Biomed. Opt. 6:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown, E. B., E. S. Wu, W. R. Zipfel, and W. W. Webb. 1999. Measurement of molecular diffusion in solution by multiphoton fluorescence photobleaching recovery. Biophys. J. 77:2837–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zipfel, W. R., and W. W. Webb. 2001. In vivo diffusion measurements using multiphoton excited fluorescence photobleaching recovery (MPFPR) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (MPFCS). In Methods in Cellular Imaging. A. Periasamy, editor. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. 216–235.

- 26.Lencer, W. I., S. W. Chu, and A. Walker. 1987. Differential binding kinetics of cholera toxin to intestinal microvillus membrane during development . Infect. Immun. 55:3126–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, J. H., K. S. Hwang, T. S. Kim, J. W. Seong, K. H. Yoon, and S. Y. Ahn. 2004. Effect of oxygen plasma treatment on adhesion improvement of Au deposited on Pa-c substrates. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 44:1177–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson, T. G., and H. M. McConnel. 2001. Condensed complexes and the calorimetry of cholesterol-phospholipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 81:2774–2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scherfeld, D., N. Kahya, and P. Schwille. 2003. Lipid dynamics and domain formation in model membranes composed of ternary mixtures of unsaturated and saturated phosphatidylcholines and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 85:3758–3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Last, J. A., T. A. Waggoner, and D. Y. Sasaki. 2001. Lipid membrane reorganization induced by chemical recognition. Biophys. J. 81:2737–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janshoff, A., and C. Steinem. 2001. Scanning force microscopy of artificial membranes. ChemBioChem. 2:798–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan, C., J. Furlong, P. Burgos, and L. J. Johnston. 2002. The size of lipid rafts: an atomic force microscopy study of ganglioside GM1 domains in sphingomyelin/DOPC/cholesterol membranes. Biophys. J. 82:2526–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cremer, P. S., and S. G. Boxer. 1999. Formation and spreading of lipid bilayers on planar glass supports. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103:2554–2559. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masserini, M., E. Freire, P. Palestini, E. Calappi, and G. Tettamanti. 1992. Fuc-GM1 ganglioside mimics the receptor function of GM1 for cholera toxin. Biochemistry 31:2422–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krell, T., F. Greco, M. C. Nicolai, J. Dubayle, G. Renauld-Mogenie, N. Poisson, and I. Bernard. 2003. The use of microcalorimetry to characterize tetanus neurotoxin, pertussis toxin and filamentous haemagglutinin. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 38:241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]