Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals with HLA-B*35 allelic variants B*3502/3503/3504/5301 (B*35-Px) progress more rapidly to AIDS than do those with B*3501 (B*35-PY). The mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon are not clear. To examine whether cellular immune responses may differ according to HLA-B*35 genotype, we quantified HIV-1-specific CD8+-T-cell (CTL) responses using an intracellular cytokine-staining assay with specimens from 32 HIV-1-positive individuals who have B*35 alleles. Among them, 75% had CTL responses to Pol, 69% had CTL responses to Gag, 50% had CTL responses to Nef, and 41% had CTL responses to Env. The overall magnitude of CTL responses did not differ between patients bearing B*35-Px genotypes and those bearing B*35-PY genotypes. A higher percentage of Gag-specific CTL was associated with lower HIV-1 RNA levels (P = 0.009) in individuals with B*35-PY. A negative association between CTL activity for each of the four HIV antigens and viral load was observed among individuals with B*35-PY, and the association reached significance for Gag. No significant relationship between CTL activity and viral load was observed in the B*35-Px group. The relationship between total CTL activity and HIV RNA among B*35-Px carriers differed significantly from that among B*35-PY carriers (P < 0.05). The data are consistent with the hypothesis that higher levels of virus-specific CTL contribute to protection against HIV disease progression in infected individuals with B*35-PY, but not in those with B*35-Px.

Associations between major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I genotype and disease have been studied in many models (29). While most of these studies have involved autoimmune diseases, several associations have been consistently identified with infectious diseases. HLA-B*35 has a codominant susceptibility effect on the rate of progression to AIDS after human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (7, 22). In contrast, HLA-B*27 is associated with slower disease progression (17, 36), and B*5701 is overrepresented in long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs) (16, 31). B*27 and B*57 carriers also had the strongest responses by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) in recipients of candidate HIV vaccines (23). Our recent study indicates that the HLA-B*35/53 subtypes B*3502, B*3503, B*3504, and B*5301 (termed B*35-Px) correlate more strongly with rapid HIV-1 disease progression than does the common Caucasian and African-American subtype, B*3501 (termed B*35-PY) (14). The mechanisms responsible for MHC class I association with HIV disease progression are not known. It is well documented that MHC class I-mediated antigen presentation determines the magnitude of a CTL response, and CTL response is crucial in protection against viral infections (20). However, an association between resistance to HIV-1 infection and recognition of CTL epitopes distinct from those targeted in HIV+ individuals with the same HLA types has been reported, suggesting that there are significant qualitative differences in CTL responses against HIV-1 (24).

The magnitude, breadth, specificity, and avidity of a CTL response may all contribute to the control of HIV viremia levels. The importance of a high-magnitude CTL response has been described in numerous reports (6, 25, 35, 37). HIV-specific CTL frequencies are strong in patients with high CD4 counts and during earlier stages of infection, whereas they are often low in later stages of infection, particularly when patients' clinical situations deteriorate (6, 25). Further, HIV-infected LTNPs were shown to have higher CTL frequencies than those who progressed to AIDS (37), and an inverse association between CTL numbers and viremia levels has been also been observed (4, 9, 11, 18, 32, 35, 38). Nevertheless, recent data have indicated that not all CTL responses are equal and that rather than quantity, the quality of the CTL response may be most important in control of viral load and AIDS progression (2, 3, 31). Because of the importance of CTL in conferring protection, it is conceivable that the class I loci may affect rate of progression to AIDS through a number of mechanisms.

On average, individuals homozygous at class I loci present a more limited range of CTL epitopes than do heterozygous individuals. Thus, viral escape mutants may arise more quickly in homozygotes, leading to dissemination of the virus and earlier onset of disease. Genetic data support this model for involvement of HLA and CTL in progression to AIDS (7). It is also reasonable to expect that HLA class I genotypes vary in the degree to which they induce a protective CTL response and that a range of responses from weak to strong occurs depending on genotype. This in turn will affect how rapidly one develops disease. Alternatively, unknown host genes associated with class I loci may be responsible for the different rates of HIV-1 progression.

We hypothesize that HIV-1-specific CTL responses are stronger (quantitatively and/or qualitatively) in B*35-PY than in B*35-Px positive individuals. Here, a potential correlation between the frequency of HIV-specific CTL and viral load was tested, addressing whether quantity of specific CTL might explain to some degree the epidemiological difference between these groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Thirty-two individuals were selected from either the Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study or a cohort of homosexual men from New York City and Washington, D.C. (33, 34). The duration of infection at the time of blood draw ranged from 10.8 to 128.4 months in these patients, their CD4 counts ranged from 8 to 2,194 per μl, and baseline viremia levels ranged from 428 to 4,810,940 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml. All blood samples were collected prior to any antiretroviral treatment. All subjects have known subtypes of B*35/53 (Table 1). These subtypes have been classified as B*35-PY (B*3501), or B*35-Px (B*3502, B*3503, or B*5301) previously, based on their epitope preference (14).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study subjects with B*35-PY and B*35-Px genotypes

| Genotype and subject no. | HLA type | HLA allele

|

Age (yr) | HIV RNA copy no. (log10) | CD4 cells/μl | Duration of infection (mo) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | C1 | C2 | ||||||

| B*35-PY | |||||||||||

| 1 | 3501 | 201 | 301 | 702 | 3501 | 401 | 702 | 16.8 | 3.78 | 460 | 56.2 |

| 2 | 3501 | 301 | 2402 | 3501 | 702 | 401 | 702 | 40.4 | 5.28 | 268 | 46.8 |

| 3 | 3501 | 6801 | 101 | 3501 | 5701 | 400 | 602 | 33.7 | 3.15 | 2,196 | 50.1 |

| 4 | 3501 | 2402 | 1101 | 3501 | 702 | 702 | 401 | 23.6 | 3.52 | 622 | 92.3 |

| 5 | 3501 | 201 | 301 | 3501 | 1501 | 303 | 400 | 16.7 | 5.24 | 701 | 57.0 |

| 6 | 3501 | 301 | 2601 | 3501 | 3801 | 401 | 1203 | 42 | 3.05 | 445 | 83.0 |

| 7 | 3501 | 201 | 3303 | 3501 | 1501 | 401 | 401 | 27.7 | 4.90 | 69 | 89.9 |

| 8 | 3501 | 201 | 302 | 3501 | 1801 | 400 | 700 | 28.3 | 5.19 | 428 | 85.6 |

| 9 | 3501 | 101 | 2402 | 3501 | 4402 | 401 | 501 | 26.4 | 4.37 | 622 | 76.0 |

| 10 | 3501 | 101 | 2601 | 1501 | 3501 | 303 | 401 | 31.2 | 4.24 | 562 | 102.1 |

| 11 | 3501 | 201 | 201 | 3501 | 5601 | 102 | 401 | 37 | 3.89 | 266 | 102.6 |

| 12 | 3501 | 201 | 201 | 3501 | 5701 | 401 | 602 | 36.6 | 2.60 | 725 | 93.5 |

| 13 | 3501 | 201 | 301 | 3501 | 4001 | 304 | 401 | 69 | 5.41 | 105 | 128.4 |

| 14 | 3501 | 301 | 6801 | 4001 | 3501 | 400 | 304 | 50.7 | 4.82 | 617 | 32.7 |

| 15 | 3501 | 200 | 300 | 3501 | 1501 | 401 | 102 | 14.2 | 5.37 | 8 | 117.4 |

| 16 | 3501 | 301 | 6801 | 3501 | 5101 | 401 | 1502 | 10.9 | 4.95 | 322 | 83.8 |

| B*35-Px | |||||||||||

| 1 | 3502 | 201 | 2601 | 3801 | 3502 | 1203 | 400 | 35 | 3.12 | 326 | 74.9 |

| 2 | 3502 | 2402 | 3303 | 1302 | 3502 | 400 | 602 | 23.9 | 4.59 | 486 | 54.1 |

| 3 | 3502 | 101 | 2601 | 2705 | 3502 | 102 | 401 | 43.9 | 6.10 | 665 | 68.1 |

| 4 | 3503 | 201 | 2402 | 3503 | 5701 | 701 | 1203 | 18.8 | 3.67 | 734 | 64.8 |

| 5 | 3503 | 101 | 2402 | 2705 | 3503 | 200 | 400 | 23 | 5.36 | 230 | 97.0 |

| 6 | 3503 | 6801 | 3303 | 3503 | 1402 | 401 | 802 | 39.9 | 4.50 | 638 | 58.2 |

| 7 | 3503 | 201 | 6801 | 3503 | 1402 | 401 | 802 | 38.4 | 5.16 | 508 | 73.6 |

| 8 | 3503 | 101 | 2501 | 801 | 3503 | 401 | 701 | 23.3 | 5.35 | 131 | 83.1 |

| 9 | 3503 | 201 | 201 | 1516 | 3503 | 401 | 1402 | 38.9 | 5.25 | 278 | 97.6 |

| 10 | 3503 | 201 | 2501 | 3503 | 1801 | 1203 | 1203 | 10.4 | 6.02 | 325 | 44.3 |

| 11 | 3503 | 301 | 1101 | 3503 | 5101 | 401 | 1202 | 42.3 | 6.68 | 336 | 100.9 |

| 12 | 3503 | 2402 | 3101 | 3503 | 5101 | 401 | 1502 | 22.1 | 3.83 | 689 | 10.8 |

| 13 | 5300 | 300 | 6802 | 700 | 5300 | 700 | 400 | 7.4 | 2.94 | 981 | 49.6 |

| 14 | 5301 | 201 | 3002 | 5301 | 5701 | 302 | 602 | 31.1 | N.A.a | 326 | 90.1 |

| 15 | 5301 | 301 | 6802 | 3801 | 5301 | 401 | 602 | 27.8 | 4.54 | 190 | 80.8 |

| 16 | 5301 | 201 | 6802 | 5301 | 5101 | 401 | 1402 | 22.3 | 5.30 | 374 | 111.4 |

Information not available.

HIV-1 viral load measurement.

HIV-1 RNA levels were quantified using the Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, N.J.), which has a detection limit of 200 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml. The HIV-1 RNA levels in study subjects were expressed as log10 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml.

HLA typing.

Genomic DNA was isolated from patients' lymphoblastoid B-cell lines and amplified with a panel of 96 sequence-specific primers for HLA-A, -B, and -C. PCR products were electrophoresed on agarose gels containing ethidium bromide, and predicted size products were visualized under UV light. Finer typing for B*35-related subtypes was achieved by direct sequencing of the PCR products with the ABI Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems Division/Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). Primers in the first and third introns of HLA-A, -B, and -C were used for locus-specific amplification of exons 2 and 3. The amplified products were subjected to cycle sequencing in both orientations. The samples were then run on an ABI 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems Division/Perkin-Elmer), and the sequences were analyzed with the Match Tools and MT navigator allele identification software (Applied Biosystems Division/Perkin-Elmer).

ICS.

The intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay has been used for measuring HIV-specific CTL responses by several groups (3, 21, 31). There are, however, major differences in ways by which the cells are stimulated. We use HIV antigen-expressing recombinant vaccinia virus-infected autologous antigen-presenting cells to stimulate a CD8+ T-cell response (21), while others use either overlapping HIV peptides (3) or recombinant vaccinia virus-infected B-lymphoblastoid cells (31). Briefly, an aliquot of 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from each patient was infected with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing B-clade HIV-1 Env, Gag, Pol, Nef, or control Eco antigens (Virogenetics, Troy, N.Y.) at a multiplicity of infection of 2 for 20 to 22 h at 37°C. Brefeldin A (10 μg/ml; Golgiplug; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) was added during the last 5 h of incubation. The cells were stained with anti-CD3PE, -CD4APC, -CD8PerCP in the pilot experiment as previously described (21) and with anti-CD69PE, -CD3APC, -CD8PerCP (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) antibodies for 30 min at 4°C in the main experiment presented in Fig. 3 and 4. After washing and permeabilization with CytoFix/Cytoperm solution (PharMingen), the cells were stained intracellularly by an anti-gamma interferon (anti-IFN-γ) fluorescein isothiocyanate antibody (PharMingen) before being analyzed using a FACScalibur flow cytometer. The fluorescence-activated cell sorter data were analyzed with CellQuest software by gating on small CD3+ CD4− T cells first, followed by displaying CD69 versus IFN-γ staining. Stimulation by a 5-μg/ml concentration of a superantigen, staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), was used as a positive control in all assays. Only samples containing at least 1% of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells, after SEB stimulation, were included in the final calculations. All experimental results were expressed as a percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells, with the background IFN-γ production from control samples subtracted. When stimulated with control antigens, we detected little IFN-γ production from CD8+ T cells (0.02% to 0.03%, n = 195) (21) and therefore contend that the assay sensitivity is sufficient and variation is minimal.

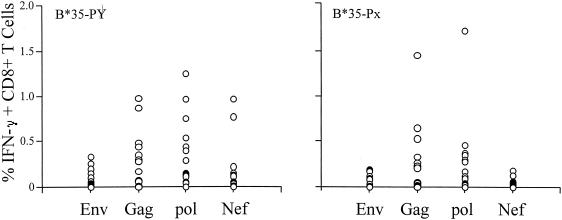

FIG. 3.

Broadly reactive antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were detected in both B*35-Px and -PY groups. The percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells specific for HIV-1-antigens Env, Gag, Pol, and Nef in each patient was expressed as one open circle. Data for 16 B*35-Px individuals and 16 B*35-PY individuals were included in each plot.

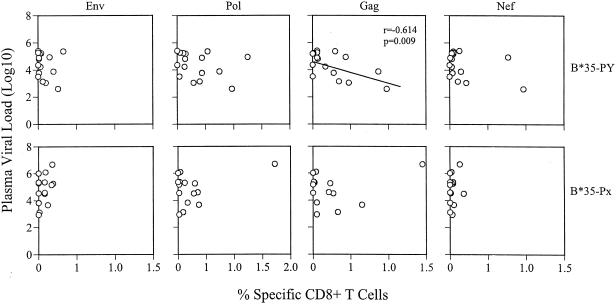

FIG. 4.

Association between viral loads and HIV-1-specific CTL numbers at the time of blood draw. Plots on the upper row are correlations between viremia (log10) levels and Env, Pol, Gag, and Nef specific CTL numbers in the B*35-PY group of patients; those on the lower row are the same correlations for the B*35-Px group of patients. Each open circle represents one patient. There is a significant inverse correlation between Gag-specific CTL and viral load in the B*35-PY group (r = −0.614; P = 0.009).

Data analysis.

To assess whether CTL levels affected HIV RNA levels among individuals carrying B*35-Px or those carrying B*35-PY, we performed a linear regression analysis for each genotype. To examine if the effect of CTL levels differed by genotype, we created homogeneity-of-slopes models that compared the relationship between CTL and HIV RNA among B*35-Px carriers to that among B*35-PY carriers. These analyses were performed using the PROC GLM program in the SAS package (6.12 ed.; SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). The interval from seroconversion to the time of the blood draw, from which both the CTL and viral load measurements were taken, was considered to be a confounding covariate in both analyses. Relative hazard (RH) and P values in the survival analysis were calculated by Cox model analysis (10).

RESULTS

Rate of progression to AIDS among individuals with B*35-Px versus B*35-PY.

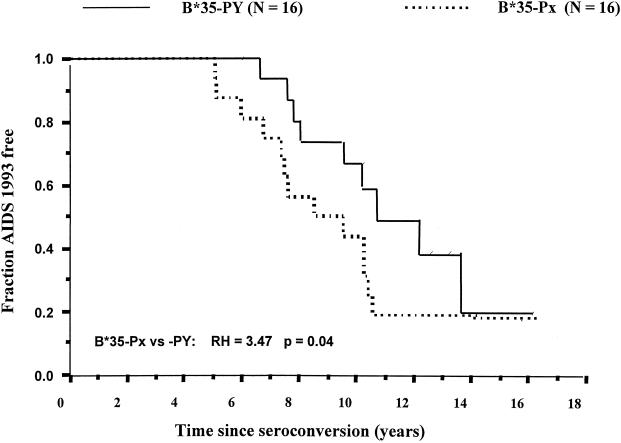

To confirm that the survival advantage of B*35-PY over -Px was true in this smaller set of patients, we compared the survival times of 16 B*35-Px and 16 B*35-PY patients. The B*35-PY group had a significantly longer survival time for the outcome AIDS 1993 (8a) (RH = 3.4; P = 0.04) (Fig. 1), but not for the later outcomes AIDS 1987 ( 8b) (RH = 1.6; P = 0.48) or AIDS-related death (RH = 1.03; P = 0.97) (data not shown). Although the sample size is small, the results were generally consistent with the previously observed results (14). The results for AIDS 1993 correspond to a median time to AIDS that is 3 years longer for the B*35-PY subjects than for the B*35-Px subjects.

FIG. 1.

Survival analysis of B*35-Px- and B*35-PY-positive individuals free of AIDS. Data for 16 B*35-Px individuals were compared with data for 16 B*35-PY individuals. RH and P were calculated by Cox model analyses.

Detection of HIV-1-specific CTL using the ICS assay.

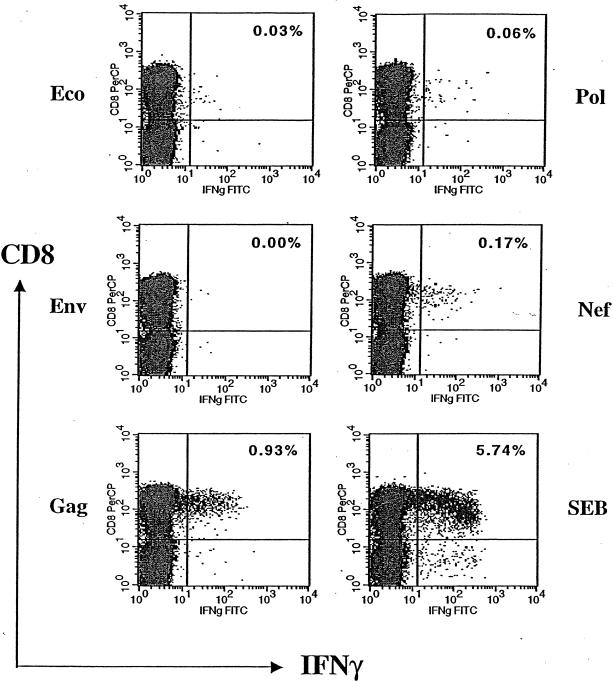

To assess the percentage of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, we developed an assay to quantify, at the single-cell level, the number of cells capable of producing IFN-γ after stimulation with HIV-1 antigens (21). This ICS assay is similar to those described previously (3, 31), differing primarily in the protocol used to stimulate the CTL (see Materials and Methods). An example of a pilot experiment using this method is illustrated in Fig. 2, where aliquots of cryopreserved PBMC from one HIV-1-infected patient were simulated with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIV-1 Env, Gag, Pol, Nef, or control Eco antigens. The percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells was enumerated as described in the Materials and Methods. In this sample, a background percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells (0.03%) was detected when stimulated with the negative control antigen Eco, and 5.74% CD8+ T cells produced IFN-γ after simulation with the positive control SEB. As expected, HIV-1 antigens activated various percentages of CD8+ T cells. Gag, Nef, and Pol stimulated 0.93, 0.17, and 0.06% CD8+ T cells, respectively, whereas Env did not activate enough CTL to be detectable. Because these percentages fall within the normal range of the frequency of HIV-specific CTL as reported by most investigators (30), we proceeded to quantify the HIV-1-specific CTL in patients bearing different HLA-B*35 subtypes.

FIG. 2.

Quantifying HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells by intracellular cytokine staining. Aliquots of PBMC from one HIV-1-infected individual were stimulated by recombinant vaccinia virus expressing negative control Eco, HIV-1 antigens (Env, Gag, Pol, and Nef), and positive control SEB first, followed by staining with anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, and -IFN-γ antibodies. The antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were enumerated and expressed as a percentage, shown on the upper right quadrant of each plot. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Lack of an overall quantitative difference in HIV-1-specific CTL responses between the B*35-Px and -PY groups.

The rapid rate of progression to AIDS among individuals with HLA-B*35-Px relative to those with B*35-PY could be explained by quantitative and/or qualitative differences in CTL activity. The frequency of CTL specific for each of the four HIV antigens was measured to determine whether a gross quantitative difference in CTL could account for the observed genetic effects. All individuals selected in this study were heterozygous at the HLA-B locus, and all but five individuals were heterozygous at HLA-A and -C (three were homozygous at HLA-A and two were homozygous at HLA-C [Table 1]). Thus, CTL restricted by at least five different HLA types would be expected to contribute to the total CTL measured for each antigen. Both the B*35-Px and -PY groups showed CD8+-T-cell responses to various HIV-1 antigens, as illustrated in Fig. 3, and the level of response to HIV-1 antigens did not differ between the B*35-Px and B*35-PY groups. Among the 32 patients studied, 75% had CTL responses to Pol, 69% had CTL responses to Gag, 50% had CTL responses to Nef, and 41% had CTL responses to Env (Fig. 3). The magnitude of these responses was variable according to antigens tested. The strongest responses were to Gag and Pol, with a mean of 0.25% + 0.34% (ranging from 0.00 to 1.45%) and 0.30% ± 0.39% (ranging from 0.00 to 1.72%), respectively. Weaker responses to Nef (0.10% ± 0.21%) and Env (0.07% ± 0.09%) were observed. The data suggest that CTL responses restricted by all HLA alleles may not differ significantly between the B*35-Px and -PY groups, although statistical power issues in the data set may hinder our ability to detect small differences. If other quantitative CTL differences between the B*35-Px and -PY groups were responsible for the observed disparity between these groups, then among the four major HIV antigens examined, they should be most evident in the response against Gag and Pol since responses to these antigens were stronger than those against Nef and Env in our data set.

Small differences in association of CTL quantity with viral load in the B*35 subgroups.

Individuals with one copy of HLA-B*35-Px progress to AIDS significantly faster than those who are homozygous for other alleles at the HLA-B locus (8), suggesting that HLA-B*35-Px may interact with HIV in a manner that results in an actively negative phenotype, rather than simply as a null allele. Based on these epidemiological findings, we propose that higher CTL numbers may not control virus in individuals with B*35-Px relative to those with other HLA-B types, because CTL restricted by individuals with B*35-Px may actually contribute to the susceptibility observed. On the other hand, higher CTL percentages might be expected to be associated with better viral control in the B*35-PY group, since CTL restricted by B*35-PY should be relatively protective. To test this hypothesis, we determined whether the frequency of CTL specific for each HIV antigen was associated with viral load in the B*35-Px and -PY groups.

For individuals with B*35-PY alleles, higher percentages of CTL specific for each of the HIV-1 antigens was associated with lower HIV RNA levels (Table 2), and the association with Gag was significant (P = 0.009). While the association between CTL and viral load did not reach significance for the other HIV antigens, the trend was observed in the analysis where CTL against all antigens were combined (P = 0.087). In contrast, no indication of a negative correlation between viral load and frequencies of CTL specific for any HIV protein tested was observed for the B*35-Px group.

TABLE 2.

Linear model analysis of effect of anti-HIV CTL levels on viral load

| Variant group | CTL category | Regression coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| B*35-Pxa | Total | 0.263 | 0.432 |

| Env | 3.996 | 0.340 | |

| Gag | 0.305 | 0.692 | |

| Pol | 0.699 | 0.301 | |

| Nef | 1.947 | 0.725 | |

| B*35-PYa | Total | −0.449 | 0.087c |

| Env | −2.419 | 0.374 | |

| Gag | −2.002 | 0.009c | |

| Pol | −0.727 | 0.302 | |

| Nef | −1.271 | 0.155 | |

| B*35-Px vs B*35-PYb | Total | 0.786 | 0.049 |

| Env | 7.383 | 0.101 | |

| Gag | 2.486 | 0.018 | |

| Pol | 1.590 | 0.092 | |

| Nef | 3.935 | 0.445 |

Data for B*35-Px and for B*35-PY show effects of CTL level on viral load for these groups considered separately. Regression coefficient is the slope.

Data for B*35-Px vs B*35-PY show difference in effect of CTL level on viral load. Regression coefficient is the comparison of B*35-Px and -PY.

Boldface type indicates P < 0.05.

It had been shown previously that the numbers of A2-restricted CTL are inversely associated with viral load (35); we therefore examined whether the same is true in our study population. A significant negative correlation was observed between CTL level and viral load for the A*02 positive individuals in this study (P = 0.003 for total CTL and P = 0.0005 for Gag-specific CTL) but not for the remainder of samples. Because A*02 is evenly distributed in the B*35-Px and -PY group of patients we studied (seven in each group), the observed difference in CTL and viral load association between the B*35-Px and -PY groups is unlikely due to the A*02 effect. However, such a deduction cannot be formally proved due to a substantial reduction in sample size if A*02-bearing subjects are excluded from the analysis used in Fig. 3 and 4 as well as Table 2.

We used a homogeneity-of-slopes model to compare the relationships of CTL frequency to viral load levels between the B*35-Px and -PY groups for each antigen and all antigens combined (Table 2). Significantly different relationships between the B*35-Px and -PY carriers were observed for all CTL combined (P = 0.049) and also for Gag alone (P = 0.018). The homogeneity-of-slopes test showed striking differences in viral load versus CTL correlations between subjects bearing and lacking A*02, for all CTL (P = 0.002), Gag-specific CTL (P = 0.001), and Pol-specific CTL (P = 0.004). These data suggest that increasing frequency of HIV-specific CTL confers protection among A*02- and B*35-PY-positive individuals but not among B*35-Px-positive individuals.

DISCUSSION

Our initial approach to understanding the functional basis for the difference in AIDS progression between individuals with B*35-Px versus those with B*35-PY was to examine potential differences in overall CTL frequency mediated through all the HLA genes present in each individual, instead of those restricted only by either the B*35-Px or -PY molecules. We did not observe a significant difference in CTL percentages between the B*35-Px and B*35-PY groups, either for total or individual HIV antigens, suggesting that the quantity of HIV-1-specific CTL overall does not account for the different rates of disease progression between these two groups. This result was not unexpected since these individuals should have CTL restricted by all other HLA types present in addition to B*35. Furthermore, we propose that B*35-Px exerts an actively negative effect on disease progression, where CTL recognizing HIV peptides in the context of B*35-Px may actually cause damage in a manner similar to that observed in autoimmune diseases. This hypothesis is based on epidemiological data showing that individuals with B*35-Px progress to AIDS significantly more rapidly than do individuals who are homozygous for other alleles at HLA-B (8), indicating that B*35-Px cannot simply be considered a null allele (i.e., where CTL recognizing HIV peptides in the context of B*35-Px are simply missing or inactive). These data correlate with a previous report which indicated that although HLA-B*57 is overrepresented in the HIV-1-infected LTNPs, there is no quantitative difference in the total HIV-1-specific CTL between B*57-positive LTNPs and B*57-positive progressors (15, 31).

Although an obvious, overall quantitative difference in frequencies of HIV-specific CTL between the two patient groups was not observed, the B*35-PY group did show an inverse relationship between CTL levels and viral loads for each HIV antigen examined. However, significance was reached only in the case of Gag-specific CTL, and the inverse correlations observed for B*35-PY were not nearly as pronounced as those for A*02. The relationship for the B*35-Px group actually tended in the opposite direction, and the difference between the B*35-Px and B*35-PYgroups in their relationships between total HIV-specific CTL level (combined CTL percentages for all four antigens) and viral loads was marginally significant (P < 0.05) (Table 2). This difference may be weakened by the presence of CTL restricted by other non-B*35 subtypes in the same individuals.

The data presented herein serve as a foundation for further studies that address activity of CTL restricted by B*35-PY versus -Px specifically. The difference between the B*35-Px and -PY groups in their association between HIV-specific CTL percentages and viral load, particularly of CTL against Gag, might be explained by several possibilities, some of which are (i) B*35-Px-bearing individuals present a similar set of peptide epitopes, but do so less effectively than those bearing the B*35-PY allele; (ii) CTL escape mutants are more frequently generated in B*35-Px-positive patients than -PY-positive patients; (iii) B*35-Px and -PY molecules present different epitopes, and those presented by CTL generated in B*35-PY are protective, but those presented by B*35-Px are not; and (iv) B*35-Px molecules suppress the CTL activity mediated through the other HLA molecules in the same individuals.

Alternatively, some HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells (i.e., those in the B*35-Px group) may not be fully functional, in that they contain less perforin or produce fewer β-chemokines, for example. Indeed, recent studies have reported the existence of HIV-1-specific CTL that lack perforin (2) and melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells that are not cytolytic (28). Further experiments using specific tetramers in combination with cytokine staining may help to test these other possibilities in patients with various subtypes.

CTL specific for some HIV antigens may be more protective against high viral load and HIV disease progression than others. Several studies concluded that CTL to early HIV or simian immunodeficiency virus gene products, such as Nef and Tat, are the most effective (1, 12, 13, 19, 26), because these CTL recognize and kill virus-infected cells before viral particles are produced. CTL specific for env gene product have been detected during primary HIV infection and appear to exert strong selective pressure on HIV genetic variation (5, 27, 32, 39). Gag sequences are highly conserved, and CTL specific for the molecule are readily detected in most patients at all stages of HIV infection (6, 25, 35, 37), suggesting that Gag-specific CTL responses could potentially restrict HIV replication. Data described herein would support a protective role for Gag-specific CTL responses after HIV infection, though qualitative effects of CTL against HIV molecules—which are not measured by methods employed here—cannot be ruled out.

While CTL are important in controlling viral replication, other factors that might contribute to the different rates of HIV-1 disease progression in HLA-B*35-bearing individuals should also be considered. Genetic factors in linkage disequilibrium with B*35 may contribute to the predisposition of these subjects to HIV-1 disease progression, as opposed to B*35 itself, though the fact that B*35-Px is associated with rapid progression in both Caucasians and African-Americans argues against this possibility (14). Furthermore, immunological factors other that CD8+ T cells, such as natural killer (NK) and CD4+ T cells, may also be important in controlling HIV-1 replication differentially through specific B*35 subtypes. Therefore, in order to fully elucidate the mechanisms of MHC class I-associated variability in rates of HIV-1 disease progression, it will be necessary to examine characteristics of these other cells as well.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Chen for graphics and Michael Plankey for the advice on statistics.

This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract NO1-CO-12400.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, T. M., D. H. O'Connor, P. Jing, J. L. Dzuris, B. R. Mothe, T. U. Vogel, E. Dunphy, M. E. Liebl, C. Emerson, N. Wilson, K. J. Kunstman, X. Wang, D. B. Allison, A. L. Hughes, R. C. Desrosiers, J. D. Altman, S. M. Wolinsky, A. Sette, and D. I. Watkins. 2000. Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes select for SIV escape variants during resolution of primary viraemia. Nature 407:386-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appay, V., D. F. Nixon, S. M. Donahoe, G. M. Gillespie, T. Dong, A. King, G. S. Ogg, H. M. Spiegel, C. Conlon, C. A. Spina, D. V. Havlir, D. D. Richman, A. Waters, P. Easterbrook, A. J. McMichael, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2000. HIV-specific CD8+ T cells produce antiviral cytokines but are impaired in cytolytic function. J. Exp. Med. 192:63-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betts, M. R., J. P. Casazza, B. A. Patterson, S. Waldrop, W. Trigona, T. M. Fu, F. Kern, L. J. Picker, and R. A. Koup. 2000. Putative immunodominant human immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses cannot be predicted by major histocompatibility complex class I haplotype. J. Virol. 74:9144-9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betts, M. R., J. F. Krowka, T. B. Kepler, M. Davidian, C. Christopherson, S. Kwok, L. Louie, J. Eron, H. Sheppard, and J. A. Frelinger. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity is inversely correlated with HIV type 1 viral load in HIV type 1-infected long-term survivors. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1219-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, X. P. Wei, M. S. Horwitz, N. Peffer, H. Meyers, J. A. Nelson, J. E. Gairin, B. H. Hahn, M. B. A. Oldstone, and G. M. Shaw. 1997. Antiviral pressure exerted by HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during primary infection demonstrated by rapid selection of CTL escape virus. Nat. Med. 3:205.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmichael, A., X. Jin, P. Sissons, and L. Borysiewicz. 1993. Quantitative analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response at different stages of HIV-1 infection: differential CTL responses to HIV-1 and Epstein Barr virus in late disease. J. Exp. Med. 177:249-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrington, M., G. W. Nelson, M. P. Martin, T. Kissner, D. Vlahov, J. J. Goedert, R. Kaslow, S. Buchbinder, K. Hoots, and S. J. O'Brien. 1999. HLA and HIV-1: heterozygote advantage and B*35-Cw*04 disadvantage. Science 283:1748-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrington, M., and S. J. O'Brien. The influence of HLA genotype on AIDS. Annu. Rev. Med, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8a.Centers for Disease Control. 1992. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 41(RR-17):1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Centers for Disease Control. 1987. Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 36(Suppl. 1):3S-15S. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connick, E., R. L. Schlichtemeier, M. B. Purner, K. M. Schneider, D. M. Anderson, S. MaWhinney, T. B. Campbell, D. R. Kuritzkes, J. M. Douglas, F. N. Judson, and R. T. Schooley. 2001. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes and virus load after recent HIV-1 seroconversion. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1465-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox, D. R., and D. Oakes. 1984. Analysis of survival data. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 11.Edwards, B. H., A. Bansal, S. Sabbaj, J. Bakari, M. J. Mulligan, and P. A. Goepfert. 2002. Magnitude of functional CD8+ T-cell responses to the gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 correlates inversely with viral load in plasma. J. Virol. 76:2298-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, D. T., D. H. O'Connor, P. Jing, J. L. Dzuris, J. Sidney, J. da Silva, T. M. Allen, H. Horton, J. E. Venham, R. A. Rudersdorf, T. Vogel, C. D. Pauza, R. E. Bontrop, R. DeMars, A. Sette, A. L. Hughes, and D. I. Watkins. 1999. Virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses select for amino-acid variation in simian immunodeficiency virus Env and Nef. Nat. Med. 5:1270-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallimore, A., M. Cranage, N. Cook, N. Almond, J. Bootman, E. Rud, P. Silvera, M. Dennis, T. Corcoran, J. Stott, and et al. 1995. Early suppression of SIV replication by CD8+ nef-specific cytotoxic T cells in vaccinated macaques. Nat. Med. 1:1167-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao, X.-J., G. W. Nelson, P. Karacki, M. P. Martin, J. Phair, R. Kaslow, J. J. Goedert, S. Buchbinder, K. Hoots, D. Vlahov, S. J. O'Brien, and M. Carrington. 2001. Effect of a single amino acid change in MHC class I molecules on the rate of progression to AIDS. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1668-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gea-Banacloche, J. C., S. A. Migueles, L. Martino, W. L. Shupert, A. C. McNeil, M. S. Sabbaghian, L. Ehler, C. Prussin, R. Stevens, L. Lambert, J. Altman, C. W. Hallahan, J. C. de Quiros, and M. Connors. 2000. Maintenance of large numbers of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected progressors and long-term nonprogressors. J. Immunol 165:1082-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goulder, P. J., M. Bunce, P. Krausa, K. McIntyre, S. Crowley, B. Morgan, A. Edwards, P. Giangrande, R. E. Phillips, and A. J. McMichael. 1996. Novel, cross-restricted, conserved, and immunodominant cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes in slow progressors in HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:1691-1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulder, P. J. R., R. E. Phillips, R. A. Colbert, S. McAdam, G. Ogg, M. A. Nowak, P. Giangrande, G. Luzzi, B. Morgan, A. Edwards, A. J. McMichael, and S. Rowland-Jones. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat. Med. 3:212.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenough, T. C., D. B. Brettler, M. Somasundaran, D. L. Panicali, and J. L. Sullivan. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), virus load, and CD4 T cell loss: evidence supporting a protective role for CTL in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 176:118-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haas, G., U. Plikat, P. Debre, M. Lucchiari, C. Katlama, Y. Dudoit, O. Bonduelle, M. Bauer, H. G. Ihlenfeldt, G. Jung, B. Maier, A. Meyerhans, and B. Autran. 1996. Dynamics of viral variants in HIV-1 Nef and specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. J. Immunol. 157:4212-4221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harty, J. T., A. R. Tvinnereim, and D. W. White. 2000. CD8+ T cell effector mechanisms in resistance to infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:275-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin, X., M. Ramanathan Jr, Jr., S. Barsoum, G. R. Deschenes, L. Ba, J. Binley, D. Schiller, D. E. Bauer, D. C. Chen, A. Hurley, L. Gebuhrer, R. El Habib, P. Caudrelier, M. Klein, L. Zhang, D. D. Ho, and M. Markowitz. 2002. Safety and immunogenicity of ALVAC vCP1452 and recombinant gp160 in newly human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients treated with prolonged highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 76:2206-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaslow, R. A., M. Carrington, R. Apple, L. Park, A. Munoz, A. J. Saah, J. J. Goedert, C. Winkler, S. J. O'Brien, C. Rinaldo, R. Detels, W. Blattner, J. Phair, H. Erlich, and D. L. Mann. 1996. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2:405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaslow, R. A., C. Rivers, J. Tang, T. J. Bender, P. A. Goepfert, R. El Habib, K. Weinhold, and M. J. Mulligan. 2001. Polymorphisms in HLA class I genes associated with both favorable prognosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 infection and positive cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses to ALVAC-HIV recombinant canarypox vaccines. J. Virol. 75:8681-8689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaul, R., T. Dong, F. A. Plummer, J. Kimani, T. Rostron, P. Kiama, E. Njagi, E. Irungu, B. Farah, J. Oyugi, R. Chakraborty, K. S. MacDonald, J. J. Bwayo, A. McMichael, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2001. CD8+ lymphocytes respond to different HIV epitopes in seronegative and infected subjects. J. Clin. Investig. 107:1303-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein, M. R., C. A. van Baalen, A. M. Holwerda, S. R. KerkhofGarde, R. J. Bende, I. P. M. Keet, J.-K. M. Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, H. Schuitemaker, and F. Miedema. 1995. Kinetics of gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses during the clinical course of HIV-1 infection: a longitudinal analysis of rapid progressors and long-term asymptomatics. J. Exp. Med. 181:1365-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenig, S., A. J. Conley, Y. A. Brewah, G. M. Jones, S. Leath, L. J. Boots, V. Davey, G. Pantaleo, J. F. Demarest, and C. Carter. 1995. Transfer of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to an AIDS patient leads to selection for mutant HIV variants and subsequent disease progression. Nat. Med. 1:330-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koup, R. A., J. T. Safrit, Y. Cao, C. A. Andrews, G. McLeod, W. Borkowsky, C. Farthing, and D. D. Ho. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune response with the initial control of viremia in primary HIV-1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, P. P., C. Yee, P. A. Savage, L. Fong, D. Brockstedt, J. S. Weber, D. Johnson, S. Swetter, J. Thompson, P. D. Greenberg, M. Roederer, and M. M. Davis. 1999. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat. Med. 5:677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh, S. G. E., P. Parham, and L. D. Barber. 2000. HLA and disease, p. 79-83, The HLA facts book. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 30.McMichael, A., and T. Hanke. 2002. The quest for an AIDS vaccine: is the CD8+ T-cell approach feasible? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:283-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Migueles, S. A., M. S. Sabbaghian, W. L. Shupert, M. P. Bettinotti, F. M. Marincola, L. Martino, C. W. Hallahan, S. M. Selig, D. Schwartz, J. Sullivan, and M. Connors. 2000. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2709-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musey, L., J. Hughes, T. Schacker, T. Shea, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 1997. Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Brien, T. R., W. A. Blattner, D. Waters, E. Eyster, M. W. Hilgartner, A. R. Cohen, N. Luban, A. Hatzakis, L. M. Aledort, P. S. Rosenberg, W. J. Miley, B. L. Kroner, and J. J. Goedert. 1996. Serum HIV-1 RNA levels and time to development of AIDS in the Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study. JAMA 276:105-110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien, T. R., P. S. Rosenberg, F. Yellin, and J. J. Goedert. 1998. Longitudinal HIV-1 RNA levels in a cohort of homosexual men. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 18:155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogg, G. S., X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffe, R. P. Dunbar, M. A. Nowak, S. Monard, J. P. Segal, Y. Cao, S. L. Rowland-Jones, V. Cerundolo, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. F. Nixon, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science 279:2103-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips, R. E., S. Rowland-Jones, D. F. Nixon, F. M. Gotch, J. P. Edwards, A. O. Ogunlesi, J. G. Elvin, J. Rothbard, C. R. M. Bangham, C. R. Rizza, and A. J. McMichael. 1991. Human immunodeficiency virus genetic variation that can escape cytotoxic T cell recognition. Nature 354:453-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinaldo, C., X. L. Huang, Z. Fan, M. Ding, L. Beltz, A. Logar, D. Panicali, G. Mazzara, J. Liebmann, M. Cottrill, and P. Gupta. 1995. High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J. Virol. 69:5838-5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Baalen, C. A., O. Pontesilli, R. C. Huisman, A. M. Geretti, M. R. Klein, F. de Wolf, F. Miedema, R. A. Gruters, and A. D. Osterhaus. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev- and Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte frequencies inversely correlate with rapid progression to AIDS. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1913-1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolinsky, S. M., B. T. M. Korber, A. U. Neumann, M. Daniels, K. J. Kunstman, A. J. Whetsell, M. R. Furtado, Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, J. T. Safrit, and R. A. Koup. 1996. Adaptive evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during the natural course of infection. Science 272:537-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]