Abstract

The transcriptional elongation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is mediated by the virally encoded transactivator Tat and its cellular cofactor, positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb). The human cyclin T1 (hCycT1) subunit of P-TEFb forms a stable complex with Tat and the transactivation response element (TAR) RNA located at the 5′ end of all viral transcripts. Previous studies have demonstrated that hCycT1 binds Tat in a Zn2+-dependent manner via the cysteine at position 261, which is a tyrosine in murine cyclin T1. In the present study, we mutated all other cysteines and histidines that could be involved in this Zn2+-dependent interaction. Because all of these mutant proteins except hCycT1(C261Y) activated viral transcription in murine cells, no other cysteine or histidine in hCycT1 is responsible for this interaction. Next, we fused the N-terminal 280 residues in hCycT1 with Tat. Not only the full-length chimera but also the mutant hCycT1 with an N-terminal deletion to position 249, which retained the Tat-TAR recognition motif, activated HIV-1 transcription in murine cells. This minimal hybrid mutant hCycT1-Tat protein bound TAR RNA as well as human and murine P-TEFb in vitro. We conclude that this minimal chimera not only reproduces the high-affinity binding among P-TEFb, Tat, and TAR but also will be invaluable for determining the three-dimensional structure of this RNA-protein complex.

The viral transcriptional transactivator Tat binds the transactivation response (TAR) element RNA stem-loop to activate the expression of genes from and replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (16, 24). TAR forms a stable hairpin at the 5′ end of all viral transcripts. Although Tat alone can bind to the 5′ bulge (from positions 23 to 25) of TAR in vitro, the central loop (from positions 31 to 36) of TAR is required for Tat transactivation in vivo (8, 16). A recent study suggested that the central loop binds the cellular cofactor of Tat, human cyclin T1 (hCycT1) (28). Thus, hCycT1 and Tat form a high-affinity complex with TAR (28, 29). This interaction results in the recruitment of Cdk9, the kinase partner of hCycT1. Cdk9 and hCycT1 or the related cyclins T2a, T2b, and K form different positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) complexes (9, 15, 20, 21). P-TEFb phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII), Spt5 from the DRB sensitivity-inducing factor, and possibly other proteins (14, 19, 20, 27). This enzymatic activity is required for the conversion of unphosphorylated (RNAPIIa) to phosphorylated (RNAPIIo) forms of RNAPII and the transition from initiation to elongation of eukaryotic transcription (21).

hCycT1 contains 726 residues (20, 28). From positions 1 to 250, 251 to 271, 370 to 430, 506 to 530, and 709 to 726, two conserved cyclin boxes, a Tat-TAR recognition motif (TRM), a coiled-coil region, a histidine-rich stretch, and the C-terminal PEST sequence, respectively, are found (28). In the TRM of hCycT1, the cysteine at position 261 forms a Zn2+-dependent interaction with other cysteines and/or histidines from positions 1 to 48 of Tat. Since the cysteine at position 261 is changed to tyrosine in the murine CycT1 (mCycT1), mCycT1 cannot support Tat transactivation (4, 6, 11, 13, 18). Although mCycT1 binds Tat with equal to slightly lower affinity than does hCycT1, its ability to coordinate TAR binding is reduced drastically (11, 13). As with mCycT1, hCycT1 from positions 1 to 250, which lacks the TRM, binds Tat more weakly and does not support Tat transactivation in cells (11). These observations indicate that cyclin boxes also bind Tat and that the TRM primarily positions the arginine-rich motifs (ARM) in Tat and hCycT1 for optimal TAR binding. Finally, hCycT1 cannot bind TAR in the absence of Tat (28).

The first 272 residues of hCycT1 are sufficient to bind Tat and TAR in vitro and to support Tat transactivation in vivo (28). However, the C-terminal region of hCycT1 plays an inhibitory role in the interaction among Tat, hCycT1, and TAR (7, 12). This inhibition can be alleviated by Tat-SF1, which is one of several cellular cofactors of Tat (7). Additionally, the autophosphorylation of Cdk9 is required for the binding of P-TEFb, Tat, and TAR (12). These observations indicate that P-TEFb, Tat, and TAR form a dynamic complex and suggest that detailed structural studies of this RNA-protein assembly could be very difficult. Indeed, to date, the complete structures of hCycT1, Cdk9, Tat, and/or TAR have not been delineated.

In the present study, we wanted to find the smallest complex consisting of hCycT1 and Tat that could be used for further structural studies of TAR. First, we determined that besides the cysteine at position 261, no other cysteines or histidines in hCycT1 are required for its Zn2+-dependent interaction with Tat. Second, we demonstrated that the fusion protein consisting of hCycT1 from positions 1 to 280 and Tat not only binds TAR in vitro but also activates the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) in murine cells. Surprisingly, in this chimera, N-terminal deletions to the TRM in hCycT1 supported Tat transactivation, which indicated that this fusion protein can interact with TAR in vivo. Finally, we demonstrated that this mutant chimera binds TAR in vitro. We conclude that the TRM and Tat form a minimal unit for high-affinity binding to TAR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions.

The plasmid reporter pHIVSCAT and the plasmid effector pcDNA3-Tat have been described previously (17). The plasmid phT280 was constructed by insertion of the PCR fragment corresponding to amino acids 1 to 280 of hCycT1 into pEF-BOS by using the BamHI and EcoRI sites. The mutant hCycT1 plasmids were constructed by using a Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech) with phT280 as the template. The plasmid for the hCycT1-Tat fusion protein (phT-Tat) was made by insertion of the PCR fragment corresponding to amino acids 1 to 101 of HIV-1 Tat into phT280 by using the EcoRI and SpeI sites. To construct the plasmids for N-terminal deletion mutagenesis, the indicated fragments were amplified by PCR by using appropriate primers with BamHI and SpeI sites from phT-Tat. Amplified fragments were inserted into the BamHI and SpeI sites of pEF-BOS or into the BamHI and SmaI sites of pGEX-2TK (Pharmacia) after the 3′ end of each fragment was filled in with T4 DNA polymerase (Roche). All of the hCycT1 constructs contained the c-Myc epitope at the C terminus of hCycT1. Western blotting using the polyclonal anti-Myc antibody A14 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) confirmed the expression of the mutant fusion proteins. The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers are available from the authors upon request.

Transient transfection and CAT assay.

NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with pHIVSCAT (0.1 μg) and mutant hCycT1 plasmids (0.5 μg) in the presence of pcDNA3-Tat (0.1 μg) (Fig. 1) or plasmids for hCycT1-Tat chimeras (0.5 μg) in the absence of pcDNA3-Tat (Fig. 2) with Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed and the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activities were measured as described previously (10).

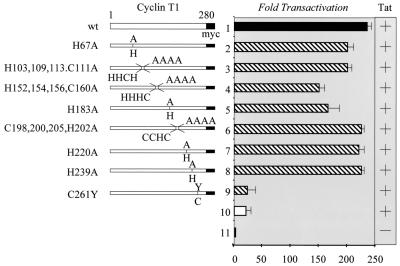

FIG. 1.

Only the cysteine at position 261 in hCycT1 participates in Tat transactivation. No other cysteines or histidines in hCycT1 are required. There are 17 cysteines and histidines in the first 280 residues of hCycT1 (left). All were mutated singly or in combination to alanines. These mutant hCycT1 proteins were then coexpressed with Tat and the HIV-1 LTR linked to the CAT reporter gene (pHIVSCAT) in NIH 3T3 cells. Levels of Tat activity are presented as increases in transactivation (n-fold) (right). Baseline values (bar 11) and those for hCycT1 and Tat are represented with black bars. The white bar indicates the activity of Tat alone on pHIVSCAT. Striped bars represent all experiments with pHIVSCAT and Tat in the presence of different mutant hCycT1 proteins. The presence of Tat is denoted by the plus sign on the right. Abbreviations: wt, wild type; H, histidine; C, cysteine; A, alanine; Y, tyrosine; myc, Myc epitope tag. Data are representative of three independent assays, with the standard errors of the means shown with error bars.

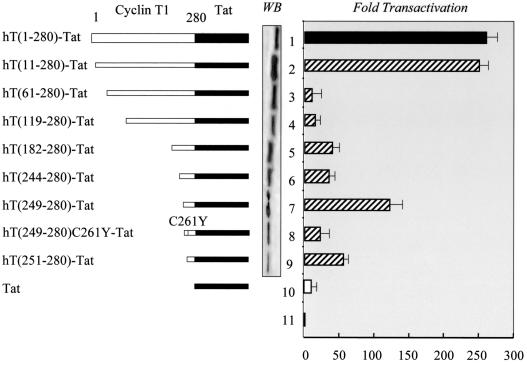

FIG. 2.

The chimera of hCycT1 and Tat activates the HIV-1 LTR in murine cells. Hybrid proteins containing hCycT1 (hT) (white bars) from positions 1 to 280 and the full-length Tat (black bars) were constructed (left). Further N-terminal deletions were introduced into hCycT1, and these mutants were examined for levels of transactivation in NIH 3T3 cells. The expression of hybrid hCycT1-Tat proteins was visualized by Western blotting using the anti-Myc antibody (WB). The activity of Tat in these chimeras is presented as increases in transactivation (n-fold). Baseline values (bar 11) and those for the wild-type hCycT1-Tat chimera are represented by black bars. The white bar indicates the activity of Tat alone on pHIVSCAT. Striped bars represent the results with pHIVSCAT and mutant hCycT1-Tat chimeras. Data are representative of three independent assays, with the standard errors of the means shown with error bars.

EMSA.

RNA probes for 32P-labeled TAR and TAR bearing a deletion of four nucleotides in the central loop (Δloop) were prepared by in vitro transcription of linearized plasmid template as described previously (11). TAR RNA was incubated with 0.5 μg of purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins in electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) buffer [30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 70 mM KCl, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, 5.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 13% glycerol, 20 μg of poly(dI-dC)/ml, 20 μg of poly(I-C)/ml] for 10 min at 30°C. RNA-protein complexes were separated by a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (4 W; 2 h at 4°C). Gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography (Fig. 3) or with a PhosphorImager (Bio-Rad) (Fig. 4).

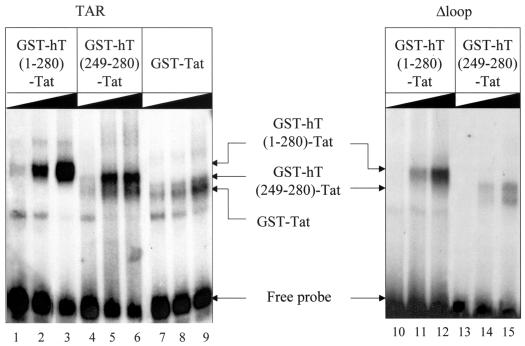

FIG. 3.

The chimera of hCycT1(249-280) and Tat binds TAR RNA. Increasing amounts (0.1 μg [lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, and 13], 0.25 μg [lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, and 14], and 0.5 μg [lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15]) of the hybrid GST-hCycT1-Tat protein [GST-hT(1-280)-Tat or GST-hT(249-280)-Tat] or the GST-Tat chimera were incubated with 32P-labeled TAR or Δloop TAR RNA probes for 10 min at 30°C as described in Materials and Methods. The RNA-protein complexes were separated in nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography. Arrows indicate the RNA-protein complexes and the free probe.

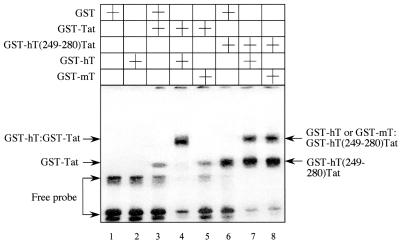

FIG. 4.

Both hCycT1 and mCycT1 can supershift the complex containing the GST-hCycT1(249-280)-Tat and TAR RNA. The purified GST or GST fusion proteins [GST-hT(249-280) or GST-Tat] were incubated with 32P-labeled TAR in the presence of 0.5 μg of GST or the GST-hCycT1 (GST-hT) or GST-mCycT1 (GST-mT) chimeras (the plus signs indicate the presence of each in the lanes). EMSA was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3 and in Materials and Methods. The gel was analyzed by a PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

Except for the cysteine at position 261, other cysteines or histidines in CycT1 are not required for Tat binding.

The interaction between hCycT1 and Tat depends on divalent metal cations such as Zn2+ or Cd2+. In particular, the cysteine at position 261 in hCycT1 is required for this binding; it is located in the TRM and is changed to tyrosine in mCycT1. However, mCycT1 as well as hCycT1 from positions 1 to 250 still bind Tat in vitro (4, 11, 13). Moreover, other Zn2+-dependent interactions between hCycT1 and Tat have not been ruled out. Indeed, the N-terminal 280 residues of hCycT1 contain 17 cysteines and histidines (H67, H103, H109, C111, H113, H152, H154, H156, C160, H183, C198, C200, H202, C205, H220, H239, and C261 [Fig. 1]). Since hCycT1 from positions 1 to 280 supports Tat transactivation in vivo, only these cysteines and histidines were examined further.

To determine whether these additional cysteines or histidines are involved in the interaction between CycT1 and Tat, they were mutated to alanines (Fig. 1). Several residues in close proximity to each other (such as H103, H109, C111, and H113; H152, H154, H156, and C160; and C198, C200, H202, and C205) were mutated collectively to alanines. The activities of these mutant hCycT1 proteins in murine NIH 3T3 cells were compared to that of the wild-type protein. The pHIVSCAT plasmid reporter, which contained the HIV-1 LTR linked to the CAT gene, was coexpressed with Tat and wild-type or mutant hCycT1 proteins from positions 1 to 280. The cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter directed the syntheses of Tat and hCycT1 proteins. Since mCycT1 cannot support Tat transactivation, the activities of exogenously introduced hCycT1 proteins in NIH 3T3 cells could be measured without considering the contribution from the endogenous mCycT1. As shown in Fig. 1, in these cells, all of our mutant hCycT1 proteins except that carrying the C261Y mutation supported Tat transactivation to the levels seen with the wild-type protein. These results indicate that all of these mutant hCycT1 proteins interact with Tat and TAR in vivo. We conclude that no other cysteines and histidines except the cysteine at position 261 are required for the interaction among Tat, hCycT1, and TAR.

Towards a minimal complex containing hCycT1, Tat, and TAR.

To map the region in hCycT1 that is required for Tat and TAR binding, we fused hCycT1 from positions 1 to 280 to Tat from positions 1 to 101 (from HIV-1SF2) and measured its activity on the HIV-1 LTR in NIH 3T3 cells [Fig. 2, hT(1-280)-Tat and bar 1]. The levels of transactivation with this chimera were comparable to those seen with the coexpression of hCycT1 and Tat (Fig. 1 and 2, compare bars 1). This finding indicated that the hCycT1 portion of the fusion protein binds Tat, Cdk9, and TAR in cells. The activity of this chimera was abolished when arginines between positions 251 and 254, which are critical for the interaction between hCycT1 and TAR in vitro, were changed to alanines, thus confirming the specificity of the fusion protein (data not shown).

Next, since the sequence from positions 250 to 272 had been identified as the TRM, we constructed a series of N-terminal truncations of hCycT1 in the chimera (Fig. 2). The activities of these fusion proteins on the HIV-1 LTR in NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 2) were measured. In these cells, the N-terminal 10 residues that contain several basic residues were dispensable for the activity of the chimera (Fig. 2, bar 2). Additional N-terminal truncations to positions 60, 118, 181, and 243 abolished or greatly diminished the activity of our mutant chimeras. These data suggest that these mutant fusion proteins lost their ability to bind Cdk9, which requires intact cyclin boxes in hCycT1 (4; K. Fujinaga and B. M. Peterlin, unpublished data). Western blotting using the A14 polyclonal antibody confirmed the expression of these Myc epitope-tagged fusion proteins (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, a further N-terminal truncation to position 248 restored up to 50% of the activity of the wild-type chimera (Fig. 2, compare bars 1 and 7). This activity depended on the cysteine at position 261 (Fig. 2, bar 8). Another 50% decrease from these levels was observed with a further truncation to position 250 in hCycT1 (Fig. 2, bar 9). This observation is consistent with the involvement of a phenylalanine at position 250 in the interaction among hCycT1, Tat, and TAR in vitro (13). From these results, we conclude first that the TRM of hCycT1 interacts with TAR in vivo and second, since the other interacting surfaces in the cyclin boxes were removed, that Tat in the fusion protein binds the endogenous mCycT1 and recruits the murine P-TEFb to TAR.

The CycT1-Tat fusion protein binds TAR in vitro.

The preceding data indicated that hCycT1 from positions 249 to 280 linked to Tat interacts with TAR in vivo. To confirm this hypothesis, EMSAs were performed. The hCycT-Tat fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli as GST fusion proteins and purified by glutathione-Sepharose affinity chromatography. Increasing amounts of purified chimeras were incubated with 32P-labeled TAR RNA at 30°C for 10 min. The complexes consisting of hCycT1, Tat, and TAR were visualized by autoradiography after nondenatured polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 3, the hCycT1-Tat fusion protein bound TAR strongly in vitro (lanes 1 to 3). The affinity of this chimera for TAR was much higher than that of Tat alone (Fig. 3, compare lanes 2 and 8). The shorter hCycT1(249-280)-Tat chimera also bound TAR efficiently (Fig. 3, lanes 4 to 6). Since a mutation from cysteine to tyrosine at position 261 blocked the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat chimera from activating transcription from the HIV-1 LTR, this binding was also dependent on the cysteine at position 261 in the TRM (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Importantly, the shorter hCycT1(249-280)-Tat chimera bound TAR bearing a deletion of four nucleotides in the central loop (Δloop) even less well than did the hCycT1-Tat fusion protein (Fig. 3, compare lanes 11 and 14 and lanes 12 and 15). Since the hCycT1-Tat chimera requires this central loop and the 5′ bulge and Tat requires only the 5′ bulge in TAR (8, 16, 28), these data indicate that the same situation pertains to the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat fusion protein, i.e., it binds TAR indistinguishably from the complex of P-TEFb and Tat.

Previous results obtained with the transient expression assay (Fig. 2) and EMSA (Fig. 3) indicated that the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat protein binds TAR, which allows the endogenous mCycT1 to activate HIV-1 transcription via the direct interaction between mCycT1 and the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat chimera. This hypothesis was confirmed by a supershift assay in vitro (Fig. 4). GST, GST-Tat, or GST-hCycT1(249-280)-Tat fusion proteins were incubated with 32P-labeled TAR RNA in the presence of GST (Fig. 4, lanes 1, 3, and 6), GST-hCycT1 (lanes 2, 4, and 7), or GST-mCycT1 (lanes 5 and 8). Neither GST-mCycT1 nor GST-hCycT1 fusion proteins bound TAR RNA in the absence of the GST-Tat chimera (Fig. 4, lane 2, and data not shown). Only hybrid GST-hCycT1 protein bound TAR in the presence of the GST-Tat chimera, resulting in the supershift of the complex consisting of the GST-Tat chimera and TAR (Fig. 4, lanes 4 and 5). These results are consistent with previous observations that hCycT1 can interact with TAR only in the presence of Tat (11, 13). In contrast, both the GST-mCycT1and GST-hCycT1 chimeras supershifted the complex containing the hybrid hCycT1(249-280)-Tat protein and TAR (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 8). We conclude that the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat fusion protein, which requires the 5′ bulge and central loop of TAR, forms the optimal surface for the binding of TAR and allows mCycT1 to interact with Tat in the chimera, resulting in the activation of HIV-1 transcription in murine cells.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we determined first that of all the possible cysteines and histidines, only the cysteine at position 261 in hCycT1 is involved in the interaction between P-TEFb and Tat. Potentially, 16 and 4 additional such residues in hCycT1 and Tat, respectively, could have participated in their constrained binding to TAR. Next, we constructed a chimera of hCycT1 and Tat that supported Tat transactivation in murine cells. Deletion of the N-terminal sequence of hCycT1, leaving TRM and Tat intact, resulted in function that was almost equivalent to that of wild-type proteins in this system. Thus, we successfully separated the activation of hCycT1 and Tat from their RNA-binding functions (Fig. 5). This minimal chimera will facilitate structural studies of the ternary complex containing hCycT1, Tat, and TAR.

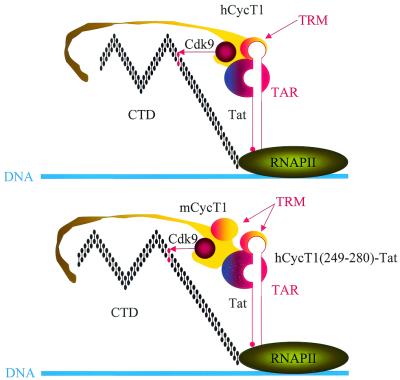

FIG. 5.

The proposed model for the activation of HIV-1 transcription by the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat chimera. The upper panel shows the activation of HIV-1 transcription by human CycT1. hCycT1 forms a stable complex with Tat and TAR via TRM and with the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNAPII via its C-terminal region, which allows its kinase partner, Cdk9, to phosphorylate the CTD (horizontal red arrow) (25). The lower panel shows the activation of HIV-1 transcription by the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat chimera in murine cells. Since the hCycT1(249-280)-Tat fusion protein provides the binding surface for TAR RNA, the endogenous P-TEFb can be recruited via the direct interaction between mCycT1 and Tat, resulting in the hyperphosphorylation of the CTD of RNAPII.

Some of the additional cysteines and histidines in hCycT1 and Tat could have contributed to their binding. Modeling hCycT1 on the basis of the known structure of another C-type cyclin, cyclin H, led to the prediction that some of these residues would be found on the same side of the cyclin boxes that bind Tat (2, 24). Additionally, like that from cyclin H, data from equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV), where the N-terminal sequence in the equine CycT1 binds leucines flanking the ARM in Tat, revealed that the N-terminal and C-terminal α-helices, one upstream and one downstream of the cyclin boxes, must lie next to each other (1, 23). Thus, additional cysteines and histidines in hCycT1 and Tat subserve other functions. Since only the cysteine at position 261 is required for Tat transactivation and RNA binding of the complex, the other three coordinated residues must come from Tat. These would be the one histidine at position 33 and the two cysteines at positions 34 and 36. They are expected to form a modified intermolecular Zn2+ finger. In this scenario, the N-terminal four cysteines at positions 22, 25, 27, and 30 in Tat coordinate the binding of another Zn2+ molecule (8). As these cysteines are missing in Tat from EIAV and as a minimal chimera of the activation domain and ARM from Tat proteins from EIAV and HIV, respectively, functions on TAR from HIV-1, their primary role must be to stabilize the structure of HIV-1 Tat.

Our data also suggest that cyclin boxes form the main surface that binds Tat and that the cysteine at position 261 correctly positions the RNA-binding domains of hCycT1 and Tat. Moreover, progressive N-terminal deletions of hCycT1 in the chimera revealed that cyclin boxes from the fusion protein could interfere with the binding between Tat and the murine P-TEFb. Thus, the best chimera contained only TRM and Tat. Nevertheless, additional truncations could be made. For example, the C-terminal boundary of TRM is at position 272, making the C terminal 8 residues shorter than in our fusion protein. The Myc epitope tag, which was essential for monitoring the expression of the proteins in cells, could be deleted. The lessons learned with Tat from EIAV also suggest that N-terminal sequences up to the histidine at position 33 in Tat could be removed. The same is true of sequences C-terminal to ARM in Tat. Although these truncations could result in an inactive protein in cells, the chimera should still bind TAR with high affinity and specificity. Importantly, these strategies would remove additional cysteines that can oxidize and/or form intermolecular bridges that could complicate detailed structural analyses.

Importantly, the RNA-binding and activating functions of Tat from HIV-1 have been successfully separated in this study, i.e., a complete and separable RNA-binding module could be created in the chimera. This finding nicely complements those from previous studies that mapped the activation domain of Tat via a heterologous RNA tethering system by using Rev of HIV-1 and/or coat protein of bacteriophage MS2/R17 (22, 26). Additionally, it correlates with the finding that Tat from bovine immunodeficiency virus does not need hCycT1 to bind TAR (3, 5). The longer ARM of Tat from bovine immunodeficiency virus represents the sum of the RNA-binding residues of hCycT1 and Tat proteins from HIV-1 and EIAV (23). Thus, the minimal activation domain, which contains the core and C-terminal cysteine-rich regions, is by itself sufficient to recruit P-TEFb to the transcription complex.

The ultimate goal is to determine the precise three-dimensional structure of the complex containing P-TEFb, Tat, and TAR. Our minimal chimera should reveal how the complex binds RNA. Additionally, the central loop in TAR should now be fixed, allowing for its precise delineation. Moreover, the core region in Tat, its activation domain, should also be constrained by the cysteine-rich region and ARM, binding TRM and the 5′ bulge in TAR, respectively. Finally, the size of this peptide makes it amenable to nuclear magnetic resonance and X-ray crystallography, which should reveal the dynamic and fixed structures of this RNA-protein complex. Indeed, large amounts of this chimera as a soluble protein can be expressed and purified from E. coli (data not shown). This three-dimensional structure will be invaluable for the future rational design of new antiviral compounds and therapeutic intervention of Tat transactivation and HIV-1 replication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paula Zupanc-Ecimovic for expert secretarial assistance and Thomas James, David Price, Wes Sundquist, and members of the Peterlin laboratory for help with the work and comments on the manuscript.

K.F. is the recipient of an NIH training grant (TG AI2441-11). This work was supported by the NIH (RO1 AI49104-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, T. R., L. H. Lund, and M. A. Garcia-Blanco. 2000. Canine cyclin T1 rescues equine infectious anemia virus Tat trans-activation in human cells. Virology 268:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen, G., D. Busso, A. Poterszman, J. R. Hwang, J. M. Wurtz, R. Ripp, J. C. Thierry, J. M. Egly, and D. Moras. 1997. The structure of cyclin H: common mode of kinase activation and specific features. EMBO J. 16:958-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barboric, M., R. Taube, N. Nekrep, K. Fujinaga, and B. M. Peterlin. 2000. Binding of Tat to TAR and recruitment of positive transcription elongation factor b occur independently in bovine immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 74:6039-6044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bieniasz, P. D., T. A. Grdina, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 1998. Recruitment of a protein complex containing Tat and cyclin T1 to TAR governs the species specificity of HIV-1 Tat. EMBO J. 17:7056-7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogerd, H. P., H. L. Wiegand, P. D. Bieniasz, and B. R. Cullen. 2000. Functional differences between human and bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat transcription factors. J. Virol. 74:4666-4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, D., Y. Fong, and Q. Zhou. 1999. Specific interaction of Tat with the human but not rodent P-TEFb complex mediates the species-specific Tat activation of HIV-1 transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2728-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong, Y. W., and Q. Zhou. 2000. Relief of two built-in autoinhibitory mechanisms in P-TEFb is required for assembly of a multicomponent transcription elongation complex at the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5897-5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel, A. D., D. S. Bredt, and C. O. Pabo. 1988. Tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus forms a metal-linked dimer. Science 240:70-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu, T. J., J. Peng, G. Lee, D. H. Price, and O. Flores. 1999. Cyclin K functions as a CDK9 regulatory subunit and participates in RNA polymerase II transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34527-34530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujinaga, K., T. P. Cujec, J. Peng, J. Garriga, D. H. Price, X. Grana, and B. M. Peterlin. 1998. The ability of positive transcription elongation factor B to transactivate human immunodeficiency virus transcription depends on a functional kinase domain, cyclin T1, and Tat. J. Virol. 72:7154-7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujinaga, K., R. Taube, J. Wimmer, T. P. Cujec, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Interactions between human cyclin T, Tat, and the transactivation response element (TAR) are disrupted by a cysteine to tyrosine substitution found in mouse cyclin T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1285-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garber, M. E., T. P. Mayall, E. M. Suess, J. Meisenhelder, N. E. Thompson, and K. A. Jones. 2000. CDK9 autophosphorylation regulates high-affinity binding of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-P-TEFb complex to TAR RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6958-6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garber, M. E., P. Wei, V. N. KewalRamani, T. P. Mayall, C. H. Herrmann, A. P. Rice, D. R. Littman, and K. A. Jones. 1998. The interaction between HIV-1 Tat and human cyclin T1 requires zinc and a critical cysteine residue that is not conserved in the murine CycT1 protein. Genes Dev. 12:3512-3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivanov, D., Y. T. Kwak, J. Guo, and R. B. Gaynor. 2000. Domains in the SPT5 protein that modulate its transcriptional regulatory properties. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2970-2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanov, D., Y. T. Kwak, E. Nee, J. Guo, L. F. Garcia-Martinez, and R. B. Gaynor. 1999. Cyclin T1 domains involved in complex formation with Tat and TAR RNA are critical for tat-activation. J. Mol. Biol. 288:41-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones, K. A., and B. M. Peterlin. 1994. Control of RNA initiation and elongation at the HIV-1 promoter. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:717-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao, S. Y., A. F. Calman, P. A. Luciw, and B. M. Peterlin. 1987. Anti-termination of transcription within the long terminal repeat of HIV-1 by tat gene product. Nature 330:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwak, Y. T., D. Ivanov, J. Guo, E. Nee, and R. B. Gaynor. 1999. Role of the human and murine cyclin T proteins in regulating HIV-1 tat-activation. J. Mol. Biol. 288:57-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall, N. F., J. Peng, Z. Xie, and D. H. Price. 1996. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27176-27183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng, J., Y. Zhu, J. T. Milton, and D. H. Price. 1998. Identification of multiple cyclin subunits of human P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 12:755-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price, D. H. 2000. P-TEFb, a cyclin-dependent kinase controlling elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2629-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selby, M. J., and B. M. Peterlin. 1990. Trans-activation by HIV-1 Tat via a heterologous RNA binding protein. Cell 62:769-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taube, R., K. Fujinaga, D. Irwin, J. Wimmer, M. Geyer, and B. M. Peterlin. 2000. Interactions between equine cyclin T1, Tat, and TAR are disrupted by a leucine-to-valine substitution found in human cyclin T1. J. Virol. 74:892-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taube, R., K. Fujinaga, J. Wimmer, M. Barboric, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Tat transactivation: a model for the regulation of eukaryotic transcriptional elongation. Virology 264:245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taube, R., X. Lin, D. Irwin, K. Fujinaga, and B. M. Peterlin. 2002. Interaction between P-TEFb and the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II activates transcriptional elongation from sites upstream or downstream of target genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:321-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiley, L. S., S. J. Madore, M. H. Malim, and B. R. Cullen. 1992. The VP16 transcription activation domain is functional when targeted to a promoter-proximal RNA sequence. Genes Dev. 6:2077-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Ferdous, T. Imai, S. Hirose, S. Sugimoto, K. Yano, G. A. Hartzog, F. Winston, S. Buratowski, and H. Handa. 1998. DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity, is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev. 12:343-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei, P., M. E. Garber, S. M. Fang, W. H. Fischer, and K. A. Jones. 1998. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell 92:451-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, J., N. Tamilarasu, S. Hwang, M. E. Garber, I. Huq, K. A. Jones, and T. M. Rana. 2000. HIV-1 TAR RNA enhances the interaction between Tat and cyclin T1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34314-34319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]