Abstract

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels (SKCa channels) are heteromeric complexes of pore-forming main subunits and constitutively bound calmodulin. SKCa channels in neuronal cells are activated by intracellular Ca2+ that increases during action potentials, and their ionic currents have been considered to underlie neuronal afterhyperpolarization. However, the ion selectivity of neuronal SKCa channels has not been rigorously investigated. In this study, we determined the monovalent cation selectivity of a cloned rat SKCa channel, rSK2, using heterologous expression and electrophysiological measurements. When extracellular K+ was replaced isotonically with Na+, ionic currents through rSK2 reversed at significantly more depolarized membrane potentials than the value expected for a Nernstian relationship for K+. We then determined the relative permeability of rSK2 for monovalent cations and compared them with those of the intermediate- and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, IKCa and BKCa channels. The relative permeability of the rSK2 channel was determined as  indicating substantial permeability of small ions through the channel. Although a mutation near the selectivity filter mimicking other K+-selective channels influenced the size-selectivity for permeant ions, Na+ permeability of rSK2 channels was still retained. Since the reversal potential of endogenous SKCa current is determined by Na+ permeability in a physiological ionic environment, the ion selectivity of native SKCa channels should be reinvestigated and their in vivo roles may need to be restated.

indicating substantial permeability of small ions through the channel. Although a mutation near the selectivity filter mimicking other K+-selective channels influenced the size-selectivity for permeant ions, Na+ permeability of rSK2 channels was still retained. Since the reversal potential of endogenous SKCa current is determined by Na+ permeability in a physiological ionic environment, the ion selectivity of native SKCa channels should be reinvestigated and their in vivo roles may need to be restated.

INTRODUCTION

Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (or SKCa channels) are potassium-selective, voltage-independent, and are activated by intracellular calcium (1,2). These channels play important roles in a wide range of physiological processes, including neuronal excitability (3), rhythmic hormone release (4), smooth muscle tone (5,6), and gain control of the hearing organ (7,8). In many neurons, SKCa channels are thought to remain open after the action potential and to contribute to afterhyperpolarization (AHP), thereby modulating interspike interval and burst duration (9). Although SKCa channel currents were considered to underlie the medium and slow components of AHP (mAHP and sAHP, respectively) in various neurons, the functional role of these currents in different neurons has been controversial (10,11). Recent experimental evidence indicates that SKCa current is responsible for the intermediate, rather than the late, phase of AHP (12,13).

Three different but highly homologous membrane proteins, SK1–3, were identified as the main subunits of SKCa channels (14). These proteins can be classified as distinct members of the K+-channel superfamily with six transmembrane (TM) domains. However, it is the small region spanning the fifth and sixth TM domains and the pore-forming region (P-region) in between that shows high homology to other voltage-gated K+ channels. All three SKCa channel subunits contain the amino acid triplet, Gly-Tyr-Gly, essential for high potassium selectivity, in their P-regions. A series of functional and structural studies showed that the main subunits of SKCa channels bind an auxiliary protein, calmodulin, as the Ca2+-sensing gating machinery (15,16). Thus, functional SKCa channels are assembled as tetramers of identical or different subunits and four calmodulins constitutively bound at each carboxyl terminus. The opening of the channels is now understood as the result of the direct binding of cytosolic Ca2+ to calmodulin and the subsequent conformational change (16–18).

Although SKCa currents are known to play pivotal roles in the excitability of various neurons, it has been difficult to study the fundamental characteristics of the channels in neurons due to their heterogeneity in electrophysiology, pharmacology, and modulation (2). It is conceivable that individual neurons may express more than one type of SKCa channel subunit and that these subunits coassemble to form heteromultimers. In this study, we investigated one of the fundamental properties of an ion channel, the selectivity among permeant ions, for a cloned SKCa channel, SK2. SK2 channels are expressed most widely in the mammalian central nervous system, especially high in the hippocampal formations, the anterior olfactory nucleus, and the granular layer of the cerebellum (14). We expressed the rat SK2 channels in two different heterologous systems, mammalian cell lines and Xenopus oocytes. We initially noticed that the reversal potentials of SKCa channel currents deviated significantly from the Nernst relationship expected for channels of high K+ selectivity. To our surprise, the SK2 channel, known to be highly selective for K+, showed significant permeability for small ions such as Li+ and Na+. In fact, the permeability compared among monovalent cations showed the SK2 channel to be one of the least selective K+ channels known so far. These results are not only intriguing but alarming, since Na+ permeability of the SKCa channel means relatively depolarized reversal potentials for the SKCa currents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of rat SK2 channels in Xenopus oocytes

Wild-type and mutant rat SK2 channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes for electrophysiological studies. Xenopus laevis (XenopusOne, Dexter, MI) was maintained and handled as described previously in accordance with the highest standards of institutional guidelines (19). Complementary DNA for the rat SK2 channel (provided by Dr. Adelman, The Vollum Institute, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR), human IK (provided by Dr. Kaczmareck, Yale University, New Haven, CT), and rat Slo (the α-subunit of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel) (20) were subcloned into a modified pGH expression vector. The generation of a mutant rSK2 channel, S359A, was reported previously (21) and L358T mutant channel was constructed using PCR-based mutagenesis as described previously. Complementary RNAs for wild-type (rSK2, hIK, and rSlo) channels and two mutant rSK2 channels were synthesized in vitro from an NcoI-linearized plasmid using T7 polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). Oocytes were injected with ∼50 ng of RNA and incubated at 18°C for 3–7 days in ND96 solution containing 5 mM HEPES, 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin, pH 7.6 adjusted with NaOH.

Expression of rat SK2 channels in mammalian cells

The coding region of the rSK2 channel was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and expressed transiently in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells for electrophysiological recordings. Cells were maintained in F12K Nutrient Mixture medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The day before transfection, 1 × 105 CHO cells were seeded on coverslips coated with 10 μg/ml poly-l-lysine and allowed to grow for 24 h. Transfections were carried out with Polyfect reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the instruction of the manufacturer. For each transfection reaction, 1.5 μg of pcDNA3.1 vector harboring the channel gene and 100 ng of pEGFP-N3 were used.

Whole-cell voltage clamp recording of SKCa channels expressed in CHO cells

Whole-cell currents of rSK2 channel were measured from transfected CHO cells using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). The recordings were made at room temperature (23°C) 1–2 days after transfection. Pipettes prepared from thin-walled borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) had resistance of 3–4 MΩ. Signals were filtered at 1 kHz using a four-pole low-pass Bessel filter, digitized at the rate of 200 samples/ms using Digidata 1200 (Axon Instruments), and stored in a personal computer. pClamp8 software (Axon Instruments) was used to control the amplifier and to acquire the data. The cell membrane was held at 0 mV and ramped from −100 to 100 mV over 1 s. The pipette (or intracellular) solution contained 116 mM KOH, 4 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, and 2 μM CaCl2, and was adjusted to pH7.2 with MES. The bath (or extracellular) solution contained 116 mM NaOH, 4 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, and 2 mM EGTA (pH 7.2), and was perfused throughout the experiment. In a serial change of extracellular K+ concentrations, K+ was substituted by isotonic concentrations of other ions such as Na+ or NMDG+ (N-methyl-d-glucamine).

Inside-out patch clamp recording of SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa channels

Ionic currents carried by rSK2 (wild-type and mutants), hIK, and rSlo channels were recorded from patches of Xenopus oocyes or CHO cell membrane in the inside-out configuration. Patch recordings were made at room temperature (23°C) 3–7 days after injection or 1–3 days after transfection. Preparation of patch pipettes and electrophysiological instruments were the same as described above. To measure the reversal potentials under the bi-ionic Na+ and NMDG+ conditions, pipette (or extracellular) solutions were prepared to contain 120 mM NaOH, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, and 4 mM HCl, or 120 mM NMDG, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, and 4 mM HCl. The membrane was held at 0 mV and ramped from −130 to 50 mV for 0.8 s, and the intracellular solution contained 116 mM KOH, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, and 4 mM KCl. In macroscopic current recordings of rSK2 and hIK channels, the membrane was held at 0 mV and ramped from −100 to 100 mV over 1 s. For macroscopic current recordings of rSlo channels, the membrane was held at −140 mV and ramped from −50 to 150 mV over 1 s. Pipette extracellular solutions contained 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, 116 mM KOH, and 4 mM KCl. Excised patches were perfused with an intracellular solution containing 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, 4 mM HCl. For bi-ionic experiments using various monovalent cations, 120 mM K+ was substituted with the same concentrations of other monovalent cations, Na+, Li+, Rb+,  or Cs+. Hydroxylated forms were used for all of the ions tested, which remain the concentration of both intracellular and extracellular solutions at 120 mM after adjusting the pH to 7.2 with MES and 4 mM HCl. To activate channel currents, the concentration of free Ca2+ in the intracellular solution was adjusted to 2 μM for SKCa, intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated (IKCa), and BKCa K+ channels. Membrane patches bearing <30 pA of currents at −100 mV under symmetrical K+ in the absence of intracellular Ca2+ were used for bi-ionic experiments, and leaks were not subtracted.

or Cs+. Hydroxylated forms were used for all of the ions tested, which remain the concentration of both intracellular and extracellular solutions at 120 mM after adjusting the pH to 7.2 with MES and 4 mM HCl. To activate channel currents, the concentration of free Ca2+ in the intracellular solution was adjusted to 2 μM for SKCa, intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated (IKCa), and BKCa K+ channels. Membrane patches bearing <30 pA of currents at −100 mV under symmetrical K+ in the absence of intracellular Ca2+ were used for bi-ionic experiments, and leaks were not subtracted.

RESULTS

Sub-Nernstian relationship between extracellular K+ and reversal potential of rat SK2 channel

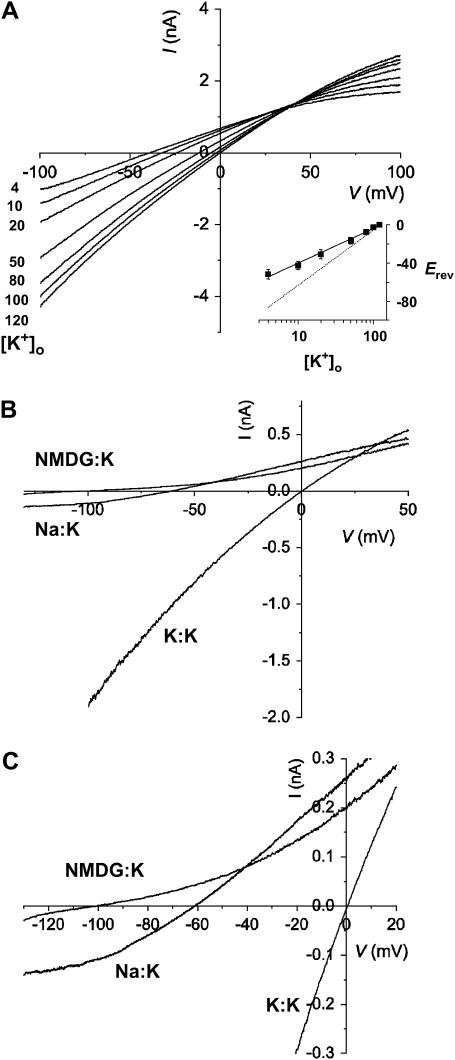

Although the SKCa channel underlying the apamin-sensitive K+ currents is assumed to be highly selective for K+, the ion selectivity of cloned SKCa channels has not been investigated rigorously. We thus expressed rat SK2 channels in two different heterologous systems, a mammalian cell line and Xenopus oocyte, and examined their permeation characteristics. We first examined the selectivity of the rSK2 channel by varying extracellular K+ concentration with a fixed intracellular K+ at 120 mM. As the extracellular K+ was isotonically substituted for Na+, the reversal potentials (Erevs) shifted to more negative values (Fig. 1 A). When the Erevs were plotted against the concentrations of extracellular K+, [K+]o, the slope was estimated as 39.8 mV per 10-fold change of [K+]o (Fig. 1 A, inset, solid line). This value is much smaller than the expected slope of ∼59 mV at room temperature (Fig. 1 A, inset, dotted line) for a perfectly selective K+ channel. The sub-Nernstian relationship between the reversal potential and the external K+ indicates that rSK channel has substantial permeability for Na+, the substituting ion.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of extracellular K+ on reversal potentials of rSK2 channel. (A) Current-voltage (I/V) relationships of rSK2 channel expressed in CHO cell in various concentrations of extracellular K+. Whole-cell K+ currents were measured using 1-s ramp pulse from −100 to 100 mV. [K+]o was varied from 120 to 4 mM with isotonic replacement of Na+. Intracellular (pipette) solution contained 120 mM K+ and 2 μM free Ca2+ for channel activation. The number beside the trace indicates the concentration of external potassium (in mM). (Inset) Reversal potentials (Erev) were plotted against various [K+]o and the slope was estimated as 39.8 mV per 10-fold change of [K+]o (solid line). Relationship between Erev and [K+]o, expected for perfect K+ selectivity (or Nernst equation) was also shown with the slope of 59 mV per 10-fold increase (dotted line). (B) I/V relationships of rSK2 channel in bi-ionic conditions. rSK2 currents were measured in inside-out configuration under symmetrical K+ (extracellular) versus K+ (intracellular) (K/K), NMDG+ versus K+ (NMDG/K) and Na+ versus K+ (Na/K) solutions. The currents were evoked by a 1-s ramp pulse from −100 to 100 mV (K/K) or 0.8-s ramp pulse from −130 to 50 mV (NMDG/K and Na/K). The concentration of all testing ions was fixed at 120 mM and the intracellular solution contained 2 μM free Ca2+. (C) The current traces were shown in expanded scales for K/K, NMDG/K, and Na/K.

To confirm the result shown above, we compared the reversal potentials of rSK2 channels in the presence of three different extracellular ions, K+, Na+, and NMDG+, in the inside-out configuration (Fig. 2, B and C). Throughout the experiments the extracellular (pipette) solution was fixed at 120 mM K+ and the intracellular (perfusion) solution contained 2 μM free Ca2+ to activate rSK2 channels. In the presence of symmetrical K+, rSK2 channel currents exhibited an inwardly rectified current-voltage (I/V) relationship reversing at the origin (K/K) as previously reported (22). When the intracellular solution was completely replaced by 120 mM NMDG+, the I/V relationship showed outward rectification and the currents reversed near −100 mV (NMDG:K) indicating that NMDG+ is virtually impermeable to rSK2 channel. However, subsequent replacement of extracellular solution to 120 mM Na+ gave a quite different outcome. We observed a significant amount of inward currents reversing around −60 mV (Na/K). Since the intracellular side of the membrane was continuously perfused with Ca2+-containing Na+ (or NMDG+) solutions, the internal accumulation of K+ from extracellular (pipette) solution should be negligible. In fact, the reversal potentials were independent of the direction of voltage ramps (data not shown). These results are not only surprising but also intriguing, since it has been generally assumed that native SKCa channels are highly selective for K+ and play a critical role in hyperpolarizing the membrane potential upon activation.

FIGURE 2.

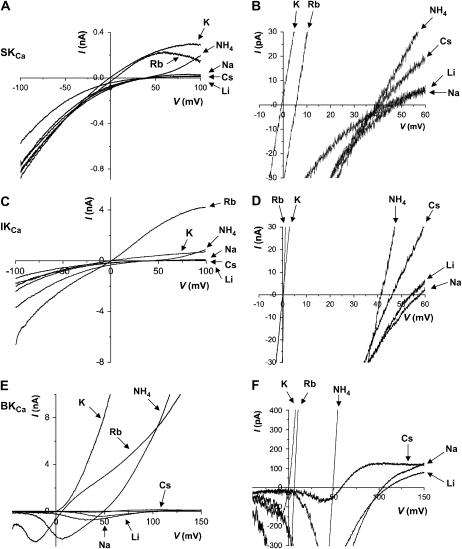

Monovalent cation selectivity of SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa channels under bi-ionic conditions. Representative traces of macroscopic K+ currents measured from excised inside-out patches containing cloned SKCa (rSK2) (A), IKCa (hIK) (C), and BKCa (rSlo) channels (E) in K+ versus various monovalent cations (Li+,  Rb+, K+, Cs+, or Na+). All recording solutions contained 120 mM of testing ions and the intracellular solutions included 2 μM Ca2+. Although SKCa and IKCa channel currents were evoked by a ramp pulse from −100 to 100 mV in 1 s, BKCa channel currents were from −50 to 150 mV in 1 s. Since the half-activation voltage of rSlo was estimated at ∼25 mV in the presence of 2 μM intracellular Ca2+ (41), the channel open probability is expected to be near maximum at 110 mV, where bi-ionic reversal potentials of Na+ and Li+ were measured. Each current trace of different extracellular monovalent cation was indicated by arrows. The current traces in expanded scales were also shown for SKCa (B), IKCa (D), and BKCa channels (F). Notice the difference in voltage scale in B and D versus F.

Rb+, K+, Cs+, or Na+). All recording solutions contained 120 mM of testing ions and the intracellular solutions included 2 μM Ca2+. Although SKCa and IKCa channel currents were evoked by a ramp pulse from −100 to 100 mV in 1 s, BKCa channel currents were from −50 to 150 mV in 1 s. Since the half-activation voltage of rSlo was estimated at ∼25 mV in the presence of 2 μM intracellular Ca2+ (41), the channel open probability is expected to be near maximum at 110 mV, where bi-ionic reversal potentials of Na+ and Li+ were measured. Each current trace of different extracellular monovalent cation was indicated by arrows. The current traces in expanded scales were also shown for SKCa (B), IKCa (D), and BKCa channels (F). Notice the difference in voltage scale in B and D versus F.

Na+ permeability of rSK2 revealed by bi-ionic experiments

We then investigated ion permeability of rSK2 channel under bi-ionic conditions using excised inside-out patches. With fixed extracellular K+ of 120 mM, the intracellular medium was substituted with other monovalent cations: Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+ Cs+, and  and ionic currents were measured in the presence of 2 μM intracellular Ca2+. Fig. 2 A shows the typical current traces of ionic currents measured by a ramp pulse of −100 to 100 mV for each ion tested. Although most of the ions showed an inwardly rectifying relationship of I/V, internal

and ionic currents were measured in the presence of 2 μM intracellular Ca2+. Fig. 2 A shows the typical current traces of ionic currents measured by a ramp pulse of −100 to 100 mV for each ion tested. Although most of the ions showed an inwardly rectifying relationship of I/V, internal  exhibited outwardly rectifying currents at extreme positive voltages. We were able to estimate Erev accurately from expanded I/V curves such as those shown in Fig. 2 B.

exhibited outwardly rectifying currents at extreme positive voltages. We were able to estimate Erev accurately from expanded I/V curves such as those shown in Fig. 2 B.

From such traces, the relative permeability (PX/PK) of rSK2 was estimated for tested ions against K+ using Eq. 1,

|

(1) |

where PX/PK is the permeability of the test ion X+ relative to K+ and Erev is the reversal potential (Table 1). Like other known K+ channels, the rSK2 channel was highly permeable for Rb+ (PRb/PK = 0.8) and less permeable for larger ions (PNH4/PK = 0.19 and PCs/PK = 0.19). Unlike other members of K+ channels, however, this channel showed significant permeability for Li+ (PLi/PK = 0.14) and Na+ (PNa/PK = 0.12), and thus further confirmed the initial indication that rSK2 should have appreciable permeability for Na+.

TABLE 1.

Bi-ionic reversal potentials (Erev) and permeability ratios (PX/PK) of cloned SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa channels, and SKCa channel mutants

| Li+ | Na+ | K+ | Rb+ |  |

Cs+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rSK2 | Erev (mV) | 50.8 ± 4.7 | 54.2 ± 3.5 | 0 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 42.7 ± 1.6 | 42.8 ± 1.6 |

| PX/PK | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 1 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | |

| hIK | Erev (mV) | 55.1 ± 1.9 | 57.9 ± 1.5 | 0 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0.36 | 39.2 ± 0.9 | 44.8 ± 1.1 |

| PX/PK | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 1 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | |

| rSlo | Erev (mV) | 110.5 ± 3.1 | 110.8 ± 2.2 | 0 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 52.1 ± 0.8 | 59.3 ± 0.9 |

| PX/PK | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 1 | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | |

| rSK2 (L358T) | Erev (mV) | 48.5 ± 1.6 | 58.9 ± 1.4 | 0 ± 0.1 | −9.3 ± 0.6 | 42.7 ± 1.6 | 22.4 ± 0.7 |

| PX/PK | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 1 | 1.45 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | |

| rSK2 (S359A) | Erev (mV) | 38.4 ± 0.5 | 23.0 ± 0.7 | 0 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 25.0 ± 1.7 | 34.4 ± 0.8 |

| PX/PK | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 1 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | |

| rSK2 (S359T) | Erev (mV) | 46.6 ± 1.9 | 51.3 ± 0.6 | 0 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 37.1 ± 0.6 | 36.4 ± 0.4 |

| PX/PK | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 1 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

We also measured the ion selectivity of another subclass of Ca2+-activated K+ channels, the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (IKCa) channel (Fig. 2, C and D). Human IK, a close homolog of the SKCa channel, showed a similar permeability series, with significant permeability for both Li+ (PLi/PK = 0.11) and Na+ (PNa/PK = 0.10) (Table 1). However, there are notable differences between SKCa channel and IKCa channel. First, the outward Rb+ currents of IKCa channel were much greater than the K+ currents, indicating that Rb+ may conduct significantly better than K+. Second, it is noteworthy that even inward currents, carried by extracellular K+, are significantly larger with Rb+ on the intracellular side of the membrane. Third, hIK channels are almost as selective for Rb+ as for K+ (PRb/PK = 0.97).

To confirm these results and rule out possible experimental artifacts, we measured the ion selectivity of BKCa channels, which belong to still another class of Ca2+-activated K+ channel with a quite different molecular structure and are proved to be highly selective for K+. The ion selectivity for BKCa channels was very different from that of either SKCa or IKCa channels. Under bi-ionic conditions using identical recording solutions, rat Slo channel, the α-subunit of rat BKCa channel, gave the rank order of  (Table 1). The permeability ratio of 0.01 estimated for Li+ and Na+ might be somewhat underestimated due to the large positive values of Erev >110 mV. Still, the permeability obtained using the rat Slo in this study is in a good agreement with a previous report for native BKCa channels (23).

(Table 1). The permeability ratio of 0.01 estimated for Li+ and Na+ might be somewhat underestimated due to the large positive values of Erev >110 mV. Still, the permeability obtained using the rat Slo in this study is in a good agreement with a previous report for native BKCa channels (23).

In Fig. 3 A, the relative permeability of various monovalent cations was plotted against their ionic radii. Permeability of small ions is prominent for both SKCa and IKCa channels. Although K+ is >100-fold more permeable than Na+ for rSlo, the permeability of rSK2 channel for K+ is <10-fold better compared with that of Na+.

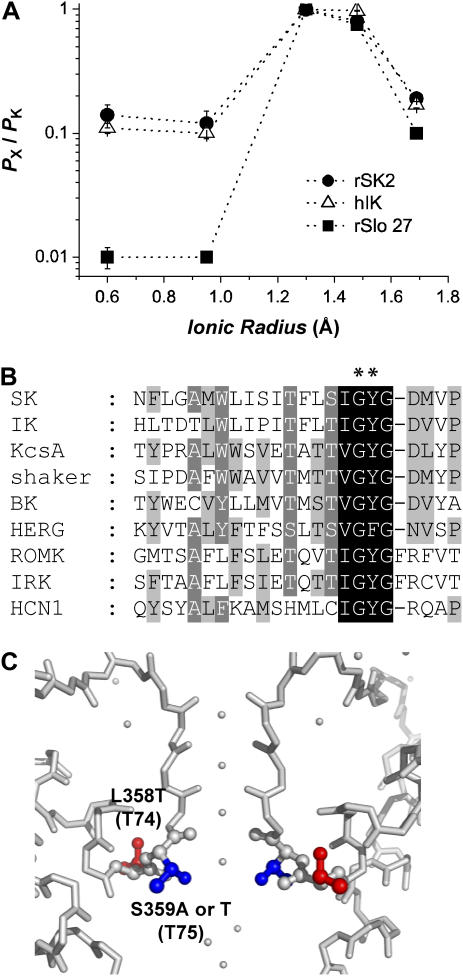

FIGURE 3.

Size selectivity of SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa channels for monovalent cations. (A) Comparison of monovalent cation permeability among three members of KCa channels. Permeability ratios of rSK2, hIK, and rSlo were plotted against the radii of different monovalent cations, Li+ (0.6 Å), Na+ (0.95 Å), K+ (1.33 Å), Rb+ (1.48 Å), and Cs+ (1.98 Å). (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of pore-forming regions of various potassium channels. Amino acid residues comprising the K+ selectivity filter were highlighted in black. Two residues (Leu-358 and Ser-359) of rSK2 mutated in this study were indicated with asterisks. GenBank number of each K+ channel is as follows: SK (AAB09563), IK (NP_075410), KcsA (Q54327), Shaker (BC054804), BK (AF 135265), HERG channels (NM_000238), ROMK (P35560), IRK (Q64273), HERG channels (NM_000238), and HCN1 (NM_000238). (C) K+-selectivity filter of KcsA channel and the predicted location of L358 and S359 in SKCa channels. The peptide backbones of two diagonally positioned KcsA K+ channel subunits were shown with the side-chain atoms of Thr-74 (corresponding to L358 in rSK2) and Thr-75 (S359 in rSK2) colored in red and blue, respectively. The figure was prepared from the crystallographic coordinates of KcsA (PDB; 1K4C) determined by Zhou et al. (25).

Effects of mutations in the pore-forming region of rSK2 channels on ion permeation

Intrigued by their Na+ permeability, we compared amino acid sequences of the pore-forming region of SKCa and IKCa channels with those of other K+ channels (Fig. 3 B). The pore-forming regions of both SKCa and IKCa channels are well conserved among other K+ channels. In particular, the amino acid sequence of the K+-selectivity filter in rSK2, is virtually identical to those K+ channels with a high K+ selectivity, such as inward rectifier K+ channels. However, we noticed that a hydrophobic residue, Leu, precedes the selectivity filter in both SKCa and IKCa channels, e.g., Leu358 in rSK2 (Fig. 3 B, asterisk). In most K+ channels, the corresponding positions are occupied by either Thr or Ser residue bearing a hydroxyl group (Fig. 3 C).

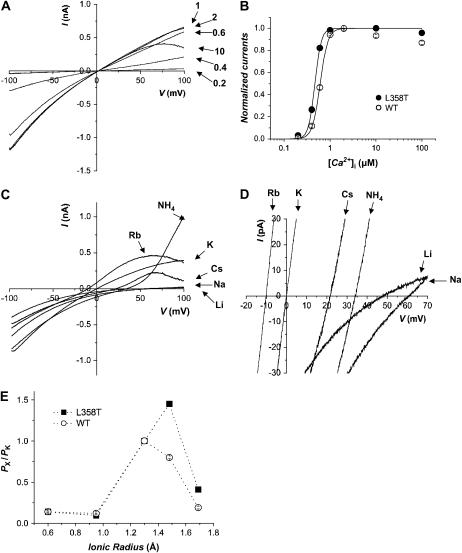

Thus we asked whether we could increase the selectivity of the rSK2 channel for K+ over other monovalent cations by mutating the Leu residue to a Thr. L358T mutant channel was expressed well in Xenopus oocytes and activated by a submicromolar concentration of intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 4 A). The Ca2+-activation curve of L358T mutant channel, with Hill coefficient n = 6.2 (half-activation constant K1/2 = 0.47), was similar to that of wild type (n = 5.1, K1/2 = 0.61) (Fig. 4 B). We then measured the ion selectivity of the mutant channel under bi-ionic conditions. The mutation did not improve the selectivity of SKCa channel for K+ over Na+ (Fig. 4, C and D) and the permeability ratios for Na+ and Li+ were almost identical to those of wild-type channels (Table 1). The most prominent effect of this Leu-to-Thr mutation was increased permeability for large cations, Rb+ and Cs+ (Fig. 4, C and D). In fact, Rb+ permeates much better than K+ in L358T mutant channel with PRb/PK of 1.45 (Table 1). It is also noteworthy that the current carried by  shows a sharp outward rectification suggesting large conductance of

shows a sharp outward rectification suggesting large conductance of  through the mutant channel. Thus, the higher selectivity for K+ was not achieved by specific substitution of the hydrophobic residue near the cytosolic end of the K+-selectivity filter to a conserved hydroxyl-bearing residue alone.

through the mutant channel. Thus, the higher selectivity for K+ was not achieved by specific substitution of the hydrophobic residue near the cytosolic end of the K+-selectivity filter to a conserved hydroxyl-bearing residue alone.

FIGURE 4.

Ion selectivity of L358T mutant channel. (A) Representative current traces of L358T mutant channel activated by various concentrations of intracellular Ca2+. (B) Effects of Leu-to-Thr substitution at position 358 on calcium-dependent channel activation. The channel currents measured at −90 mV were normalized with maximum current obtained at 2 μM for wild-type (○) and L358T mutant channel (•). Each data point was plotted against [Ca2+]i and fitted to a Hill equation. Half-activation constants (K1/2) and Hill coefficients (n), respectively, were estimated as 0.61 μM and 5.18 for wild-type rSK2, and 0.47 μM and 6.23 for L359T. (C) Representative traces of macroscopic currents measured from excised inside-out patches containing L359T mutant channel in K+ versus various monovalent cations. The currents were evoked by a ramp pulse from −100 to 100 mV in 1s. All recording solutions contained 120 mM of testing ions and the intracellular solutions included 2 μM Ca2+. Each current trace of different extracellular monovalent cation was indicated by an arrow. The current traces in expended scales were also shown (D). (E) Effect of mutation on size selectivity of rSK2 channel. Permeability ratios of wild-type rSK2 and L358T mutant were coplotted against the radius of each monovalent cation.

We also examined the effects of mutations at the adjacent residue, Ser-359, on monovalent cation selectivity (Fig. 3, B and C). Since the Ser residue was revealed to interact with divalent cations from the intracellular side and to be responsible for the rectified I/V relationship of rSK2 channel (21), the residue should also be involved in the permeation of K+ and other monovalent caions. In the case of the KcsA channel, the hydroxyl group of a Thr-residue (T74 in Fig. 3 C) counterpart of Ser-359 in rSK2 channel is involved in the direct coordination of K+ at the most cytosolic site (“Site 1”) of the four K+-binding sites in the selectivity filter (24,25).

The current traces of two different mutants, S359A and S359T, are shown in Fig. 5, A and B, and C and D, respectively. The Ser-to-Ala mutation rendered significant changes in the selectivity for monovalent cations (Fig. 5 E). First of all, Rb+ was almost as permeable as K+ in S359A channels. Second, the permeability of smaller ions increased dramatically; the relative permeability of S359A for Na+ increases from 0.12 to 0.40 (Table 1). The apparent conductance of small ions, Li+ and Na+, also increases significantly. Third, the permeability of lager ions was increased slightly but significantly, from 0.19 to 0.26 for Cs+ (Table 1). When the Ser-359 was replaced with a conserved Thr residue, the permeation characteristics of wild-type channel were restored and only a minor change was observed in both selectivity and conductance among different monovalent cations (Fig. 5 E and Table 1). Thus, these results indicate that the hydroxyl group at Ser-359 is critical not only for high-affinity interaction of intracellular divalent cations as shown in a previous study (21) but also for size selectivity among permeant ions of monovalence.

FIGURE 5.

Mutational effects of ion permeation at intracellular divalent cation-binding site. Representative traces of macroscopic K+ currents evoked by S359A (A) and S359T (C) under bi-ionic conditions. The current traces in expanded scales were also shown for S359A (B) and S359T (D). (E) Permeability ratios (PX/PK) of S359A and S359T mutant channels were coplotted with those of the wild-type against the ionic radius of different monovalent cations.

DISCUSSION

Potassium channels are generally considered to exhibit high selectivity for K+. In the physiological ionic environment, selective permeation of K+ over Na+ is a challenging task that K+-selective ion channels must fulfill. All K+ channels contain a narrow region, the K+-selectivity filter, at which K+ is selected against other ions (26,27). A stretch of amino acids, the K+-channel signature sequence, determines the structure of the selectivity filter and provides the carbonyl oxygens that create the K+-binding sites (24,25,28). As members of the K+-channel family, the SKCa channels contain the amino acid sequence TFLSIGYG (14), highly homologous to the canonical “K+-channel signature”, TXXTXGYG (29). The high selectivity for K+ is believed to be critical for the presumed physiological function of SKCa channels in inducing membrane hyperpolarization and modulating neuroexcitability. Although SKCa channels are known to underlie the prolonged afterhyperpolarization (or slow AHP) after trains of action potentials, AHP differs among tissues in time course (30,31) and pharmacology (32,33).

Based on the measurements of reversal potentials under bi-ionic conditions, we determined the selectivity of rSK2 channel for monovalent cations. Calculated permeability ratios (PX/PK) for the wild-type rSK2 yielded the order of  (Table 1). The channel exhibits surprisingly high permeability for Li+ and Na+. Moreover, the IKCa channel, which is highly homologous to the SKCa channel, also shows a similar Na+ permeability. The permeability (PX/PK) of native SKCa currents was determined in chromaffin cells (34) and reported as

(Table 1). The channel exhibits surprisingly high permeability for Li+ and Na+. Moreover, the IKCa channel, which is highly homologous to the SKCa channel, also shows a similar Na+ permeability. The permeability (PX/PK) of native SKCa currents was determined in chromaffin cells (34) and reported as  markedly in contradiction to the results reported here. At this point the cause for this discrepancy is unclear. However, we wonder whether the endogenous SKCa currents in the previous study were properly measured for bi-ionic Na+ versus K+ and Li+ versus K+ conditions, since rapid run-down occurred after replacement of external K+ with Na+ or Li+ and the resulting currents were extremely small (<40 pA). We experienced no such run-down of rSK2 currents after serial replacement with various extracellular monovalent cations.

markedly in contradiction to the results reported here. At this point the cause for this discrepancy is unclear. However, we wonder whether the endogenous SKCa currents in the previous study were properly measured for bi-ionic Na+ versus K+ and Li+ versus K+ conditions, since rapid run-down occurred after replacement of external K+ with Na+ or Li+ and the resulting currents were extremely small (<40 pA). We experienced no such run-down of rSK2 currents after serial replacement with various extracellular monovalent cations.

In an attempt to rationalize the high Na+ permeability in terms of amino acid sequence near the K+-selectivity filter, we compared the amino acid sequence of the P-regions in SKCa channels to that in other K+ channels (Fig. 3 B). Although both SKCa and IKCa channels contain a virtually perfect K+-channel signature sequence in their pore, the selectivity filter, or K+-binding sequence SIGYG, is preceded by a hydrophobic residue, Leu, instead of Thr or Ser in other K+ channels. Whereas three different residues, Thr, Ala, and Ser, at this position produced K+-selective channels, the mutation to Gly or Asn failed to express functional Shaker K+ channels (35). Intriguingly, the hyperpolarization-activated channel, HCN4, which is much less selective for K+, also has Leu at the corresponding position (36). However, the simple replacement of Leu with Thr in rSK2 failed to restore the high K+ selectivity seen in other K+ channels. Rather, L358T increased the permeability of larger ions, Rb+ and Cs+. It is also worth pointing out that the permeability of Rb+ becomes higher than K+ in the mutant channel. Although it is impossible to interpret these results without structural information at a high resolution, we can appreciate the fact that the identity of neighboring residues near the selectivity filter and the subtle changes in protein conformation in this area can influence permeation properties of ion channels, as observed in many previous studies.

The most important aspect of the results we report here is the physiological significance of the Na+ permeability of SKCa channels. Under the physiological ionic condition, i.e., 145 mM Na+ and 5 mM K+ in the extracellular milieu versus 12 mM Na+ and 140 mM K+ in cytoplasm, the relative permeability of Na+ (PNa/PK) measured for homomeric SK2 channel, 0.12, yields a membrane Erev of −46 mV. This value is significantly less negative than the reversal voltage that might be expected for afterhyperpolarization currents, IAHP. In recent studies using knock-out models and a dominant negative SKCa channel subunit, the SKCa channel was shown to underlie only the apamin-sensitive component of the medium-duration AHP and none of the three SKCa channel subunits contributes to the longer-lasting sAHP (12,13).

One intriguing possibility is the involvement of Na+-activated K+ channels in the generation of sAHP. Although the relative conductance of Na+ (GNa/GK) is small compared to that of K+, estimated as 0.11 based on the slope conductance at 0 mV under bionic condition (Fig. 2, A and B), we expect that the opening of SKCa channels allows significant Na+ permeation in the negative voltage range. In turn, the influx of Na+ might evoke Na+-activated K+ (KNa) channels that are known to express in many neuronal cells (37,38). These channels exhibit diverse characteristics depending on cell type and recording condition. Single-channel conductances of KNa channels are large (100–200 pS) and the channels are activated by tens of millimoles of intracellular Na+. Although KNa channels have been implicated in an apamin-insensitive and Na+-dependent slow afterhyperpolarization after a burst of action potentials (37), it remains questionable whether the concentration of intracellular Na+ can increase enough to activate the channel. Recently, the products of two different genes, slack and slick, were proposed as the subunits for Na+-activated K+ channels (39,40). Both Slack (Slo2.2) and Slick (Slo2.1) are highly expressed in the brain and generate Na+-activated K+ currents in heterologous systems. Thus, it will be critical to determine whether native SKCa channels also show significant permeability for Na+ under physiological condition and whether the local concentration of cytosolic Na+ can be high enough to activate Na+-activated K+ currents, especially in neuronal cells. It also remains to be shown whether the heteromerization of different subunits affects the selectivity of SKCa channel.

In summary, we determined the relative permeability of a cloned SKCa channel, rSK2, and recognized the significant permeability of Na+ through this channel. Although the mutations at the pore-forming region mimicking other K+-selective pores altered the size selectivity for permeant ions, they failed to restore a high K+ selectivity for SKCa channel. Since the permeability for Na+ determines the reversal potential of endogenous SKCa current in a physiological ionic environment, the ion selectivity of native SKCa channels should be determined and the role of Na+ permeability in neuronal excitability needs to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the members of the Laboratory of Molecular Neurobiology at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology for their valuable comments and timely help throughout this work, and Dr. C. Miller at Brandeis University for his critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by research grant's from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Korea, 21C Frontier (03K2201-00320) to C.S.P. and Systems Biology (M1050 301001) to D.H.K.

References

- 1.Maylie, J., C. T. Bond, P. S. Herson, W. S. Lee, and J. P. Adelman. 2004. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels and calmodulin. J. Physiol. 554:255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sah, P., and E. S. Faber. 2002. Channels underlying neuronal calcium-activated potassium currents. Prog. Neurobiol. 66:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stocker, M., M. Krause, and P. Pedarzani. 1999. An apamin-sensitive Ca2+-activated K+ current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4662–4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tse, A., and B. Hille. 1992. GnRH-induced Ca2+ oscillations and rhythmic hyperpolarizations of pituitary gonadotropes. Science. 255:462–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doughty, J. M., F. Plane, and P. D. Langton. 1999. Charybdotoxin and apamin block EDHF in rat mesenteric artery if selectively applied to the endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 276:H1107–H1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrera, G. M., T. J. Heppner, and M. T. Nelson. 2000. Regulation of urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions by ryanodine receptors and BK and SK channels. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 279:R60–R68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver, D., N. Klocker, J. Schuck, T. Baukrowitz, J. P. Ruppersberg, and B. Fakler. 2000. Gating of Ca2+-activated K+ channels controls fast inhibitory synaptic transmission at auditory outer hair cells. Neuron. 26:595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vetter, D. E., J. R. Mann, P. Wangemann, J. Liu, K. J. McLaughlin, F. Lesage, D. C. Marcus, M. Lazdunski, S. F. Heinemann, and J. Barhanin. 1996. Inner ear defects induced by null mutation of the isk gene. Neuron. 17:1251–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madison, D. V., and R. A. Nicoll. 1984. Control of the repetitive discharge of rat CA 1 pyramidal neurones in vitro. J. Physiol. 354:319–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stocker, M. 2004. Ca2+-activated K+ channels: molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5:758–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bond, C. T., J. Maylie, and J. P. Adelman. 2005. SK channels in excitability, pacemaking and synaptic integration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15:305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villalobos, C., V. G. Shakkottai, K. G. Chandy, S. K. Michelhaugh, and R. Andrade. 2004. SKCa channels mediate the medium but not the slow calcium-activated afterhyperpolarization in cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 24:3537–3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bond, C. T., P. S. Herson, T. Strassmaier, R. Hammond, R. Stackman, J. Maylie, and J. P. Adelman. 2004. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel knock-out mice reveal the identity of calcium-dependent afterhyperpolarization currents. J. Neurosci. 24:5301–5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohler, M., B. Hirschberg, C. T. Bond, J. M. Kinzie, N. V. Marrion, J. Maylie, and J. P. Adelman. 1996. Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science. 273:1709–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keen, J. E., R. Khawaled, D. L. Farrens, T. Neelands, A. Rivard, C. T. Bond, A. Janowsky, B. Fakler, J. P. Adelman, and J. Maylie. 1999. Domains responsible for constitutive and Ca2+-dependent interactions between calmodulin and small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 19:8830–8838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia, X. M., B. Fakler, A. Rivard, G. Wayman, T. Johnson-Pais, J. E. Keen, T. Ishii, B. Hirschberg, C. T. Bond, S. Lutsenko, J. Maylie, and J. P. Adelman. 1998. Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 395:503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher, M. A., A. F. Rivard, H. P. Bachinger, and J. P. Adelman. 2001. Structure of the gating domain of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel complexed with Ca2+/calmodulin. Nature. 410:1120–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wissmann, R., W. Bildl, H. Neumann, A. F. Rivard, N. Klocker, D. Weitz, U. Schulte, J. P. Adelman, D. Bentrop, and B. Fakler. 2002. A helical region in the C terminus of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels controls assembly with apo-calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 277:4558–4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park, C. S., and R. MacKinnon. 1995. Divalent cation selectivity in a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. Biochemistry. 34:13328–13333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha, T. S., S. Y. Jeong, S. W. Cho, H. Jeon, G. S. Roh, W. S. Choi, and C. S. Park. 2000. Functional characteristics of two BKCa channel variants differentially expressed in rat brain tissues. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:910–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soh, H., and C. S. Park. 2002. Localization of divalent cation-binding site in the pore of a small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel and its role in determining current-voltage relationship. Biophys. J. 83:2528–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soh, H., and C. S. Park. 2001. Inwardly rectifying current-voltage relationship of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels rendered by intracellular divalent cation blockade. Biophys. J. 80:2207–2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blatz, A. L., and K. L. Magleby. 1984. Ion conductance and selectivity of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 84:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morais-Cabral, J. H., Y. Zhou, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature. 414:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou, Y., J. Morais-Cabral, A. Kaufman, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 Å resolution. Nature. 414:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKinnon, R. 2003. Potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 555:62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miloshevsky, G. V., and P. C. Jordan. 2004. Permeation in ion channels: the interplay of structure and theory. Trends Neurosci. 27:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle, D. A., J. Morais Cabral, R. A. Pfuetzner, A. Kuo, J. M. Gulbis, S. L. Cohen, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 1998. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 280:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heginbotham, L., M. LeMasurier, L. Kolmakova-Partensky, and C. Miller. 1999. Single streptomyces lividans K+ channels: functional asymmetries and sidedness of proton activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:551–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennefather, P., B. Lancaster, P. R. Adams, and R. A. Nicoll. 1985. Two distinct Ca-dependent K currents in bullfrog sympathetic ganglion cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 82:3040–3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lancaster, B., and P. R. Adams. 1986. Calcium-dependent current generating the afterhyperpolarization of hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 55:1268–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sah, P., and E. M. McLachlan. 1991. Ca2+-activated K+ currents underlying the afterhyperpolarization in guinea pig vagal neurons: a role for Ca2+-activated Ca2+ release. Neuron. 7:257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sah, P. 1993. Kinetic properties of a slow apamin-insensitive Ca2+-activated K+ current in guinea pig vagal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 69:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park, Y. B. 1994. Ion selectivity and gating of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in cultured rat adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Physiol. 481:555–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heginbotham, L., Z. Lu, T. Abramson, and R. MacKinnon. 1994. Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophys. J. 66:1061–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stieber, J., A. Thomer, B. Much, A. Schneider, M. Biel, and F. Hofmann. 2003. Molecular basis for the different activation kinetics of the pacemaker channels HCN2 and HCN4. J. Biol. Chem. 278:33672–33680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dryer, S. E. 1994. Na+-activated K+ channels: a new family of large-conductance ion channels. Trends Neurosci. 17:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franceschetti, S., T. Lavazza, G. Curia, P. Aracri, F. Panzica, G. Sancini, G. Avanzini, and J. Magistretti. 2003. Na+-activated K+ current contributes to postexcitatory hyperpolarization in neocortical intrinsically bursting neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 89:2101–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan, A., C. M. Santi, A. Wei, Z. W. Wang, K. Pollak, M. Nonet, L. Kaczmarek, C. M. Crowder, and L. Salkoff. 2003. The sodium-activated potassium channel is encoded by a member of the Slo gene family. Neuron. 37:765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhattacharjee, A., W. J. Joiner, M. Wu, Y. Yang, F. J. Sigworth, and L. K. Kaczmarek. 2003. Slick (Slo2.1), a rapidly-gating sodium-activated potassium channel inhibited by ATP. J. Neurosci. 23:11681–11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ha, T. S., M. S. Heo, and C. S. Park. 2004. Functional effects of auxiliary β4 subunit on rat large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Biophys. J. 86:2871–2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]