Abstract

The fusion peptides of HIV and influenza virus are crucial for viral entry into a host cell. We report the membrane-perturbing and structural properties of fusion peptides from the HA fusion protein of influenza virus and the gp41 fusion protein of HIV. Our goals were to determine: 1), how fusion peptides alter structure within the bilayers of fusogenic and nonfusogenic lipid vesicles and 2), how fusion peptide structure is related to the ability to promote fusion. Fluorescent probes revealed that neither peptide had a significant effect on bilayer packing at the water-membrane interface, but both increased acyl chain order in both fusogenic and nonfusogenic vesicles. Both also reduced free volume within the bilayer as indicated by partitioning of a lipophilic fluorophore into membranes. These membrane ordering effects were smaller for the gp41 peptide than for the HA peptide at low peptide/lipid ratio, suggesting that the two peptides assume different structures on membranes. The influenza peptide was predominantly helical, and the gp41 peptide was predominantly antiparallel β-sheet when membrane bound, however, the depths of penetration of Trps of both peptides into neutral membranes were similar and independent of membrane composition. We previously demonstrated: 1), the abilities of both peptides to promote fusion but not initial intermediate formation during PEG-mediated fusion and 2), the ability of hexadecane to compete with this effect of the fusion peptides. Taken together, our current and past results suggest a hypothesis for a common mechanism by which these two viral fusion peptides promote fusion.

INTRODUCTION

Membrane fusion is fundamental to the life of eukaryotic cells. Cellular trafficking and compartmentalization, sexual reproduction, cell division, and protein sorting are dependent on this basic event. Membrane fusion mediated by the envelope glycoproteins of influenza virus (hemagglutinin, HA0) (1–3) and of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1; gp160) (4,5) has been extensively studied. Both envelope proteins consist of two associated parts: one binds a receptor (HA1/gp120) whereas the other promotes membrane fusion (HA2/gp41). Glycoprotein gp120 binds to the cell surface receptor CD4 (6) and chemokine receptors (7) and undergoes conformational changes that trigger binding to its companion peptide, gp41 (4,8). Similarly, the HA1 component of HA0 contains sialic acid binding sites that bind to the cell surface receptor, GM1. Both gp41 and HA2 form trimers and undergo a conformational change (HA2 at low pH and gp41 through its association with CD4-bound gp120) to a state that is able to catalyze fusion of the viral envelope with a cell membrane (surface membrane for gp41 and endosome membrane for HA) (9–12). These conformational changes in HA and gp41 expose N-terminal amphipathic, glycine-rich regions of 20–25 amino acids (11,13). Mutations in these regions can block fusion-mediated viral infection, so they are termed “fusion peptides” (14).

The fusion peptide regions of viral fusion proteins associate with target membranes (15,16) and, based on studies of the effect of synthetic fusion peptides, are widely viewed as destabilizing membranes to promote fusion (17–22). This view has been challenged by reports that the high peptide concentrations used in most studies compromise bilayer integrity rather than induce fusion (23,24). However, both peptides, when present at low surface concentrations, do promote fusion when poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or Ca2+ bring membranes into close contact (23–25). Under the condition of low surface concentration, these peptides promote fusion pore formation to a greater extent than they promote formation of an initial “hemifusion intermediate” (contacting bilayer leaflets joined but no stable pore formed) (23,24).

The mechanism by which N-terminal fusion peptides promote fusion is not clear, although the literature offers several suggestions. Several articles have suggested that some peptide secondary structures are fusogenic and some are not (25–28). Others have suggested that fusion peptides perturb the bilayer surface (i.e., increase surface tension and destabilize the bilayer) (29,30). Our observations led to the proposal that fusion peptides promote pore formation by filling space within intermediate nonbilayer structures to promote pore formation (23,24). The current study was undertaken to ask whether the structures of the peptides on a bilayer and the effects of peptides on different regions of the bilayer might be consistent with one or more of these interpretations. Because we found that these two fusion peptides promoted fusion only of highly curved membranes (23,24), we also asked here whether the peptides might behave differently on bilayers of different compositions and curvature.

To answer these questions, we have examined complexes formed by fusion peptides and lipid vesicles using intrinsic fluorescence, fluorescent probes of membrane order, circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD), and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Our measurements reveal no clear relationship between peptide structure and the ability to promote pore formation. However, both peptides increased chain packing or order within the hydrophobic core of the bilayer but had little change in the packing or structure of the interfacial region of the bilayer. These results argue against a role for fusion peptides in disrupting the surface packing of the unfused state but are consistent with our previous suggestion that fusion peptides occupy hydrophobic mismatch (HMM) regions of nonbilayer structures to promote fusion (23,24). A structural hypothesis is presented that proposes how two peptides with different secondary structures might have this common effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chloroform stock solutions of 1,2-dioleoyl-3-sn-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-3-sn-phosphatidylcholine (POPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-sn-phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-sn-phosphatidylserine (DOPS), bovine brain sphingomyelin (SM), 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl (6-7 dibromo)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (6-7 Bromo-PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl (11-12 dibromo)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (11-12 Bromo-PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-N-(4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole) aminohexanoyl phosphatidylcholine (C6-NBD-PC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL) and used without further purification. The concentration of all the stock lipids was determined by phosphate assay (31). Cholesterol (CH) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids and was further purified by published procedures (32). 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) and 1-(4-trimethyammonium)-6-phenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (TMA-DPH) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). N-[tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl]2-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid (TES) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Deuterium oxide (99.8% deuterated) was purchased from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, WI). All other reagents were of the highest purity grade available.

METHODS

Vesicle preparation

Vesicles were prepared from DOPC, POPC, or from a mixture of DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH in the molar ratio 35:30:15:20. Lipids at appropriate molar ratios in chloroform were freeze dried under high vacuum overnight. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared as reported previously (33). The dried lipid powders were suspended in an appropriate buffer for 1 h above the main phase transition. Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were prepared by the extrusion method (34), using 10 passes through a 0.1 μm polycarbonate filter (Nucleo Pore, Pleasantor, CA) at room temperature under a pressure of 100 psi of N2. Details of this method are described in an earlier publication (35). The buffer contained 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM CaCl2 at either pH 7.5 (adjusted with 10 mM TES), or pH 5.5 (adjusted with 10 mM MES). Measurements were carried out using 0.2 mM lipid.

Preparation of gp41 and HA peptides

The X-31 HA (native) and the gp41 fusion peptides (native and mutant) were chemically synthesized and purified by the peptide synthesis laboratory at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (David Klapper, director). The sequences of the peptides are GLFGAIAGFIENGWEGMIDG (X-31 HA, native), AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGARS (gp41, native) and AVGIGALWLGFLGAAGSTMGARS (gp41, mutant). The peptides were synthesized by the standard solid phase method using fMOC chemistry. Detailed descriptions of the synthesis and purification of these peptides are given in previous publications (23,24). Stock peptide solutions were prepared in DMSO solvent, and small aliquots of these solutions were added to vesicle suspensions. DMSO was always <1% of the buffer volume, and control experiments showed that this amount of DMSO had no effect on the surface properties of the bilayers.

DPH and TMA-DPH fluorescence anisotropy

Incorporation of DPH and TMA-DPH into membranes was accomplished by adding a small volume (0.04–0.08% of vesicle sample volumes) of stock solutions of either DPH or TMA-DPH in methanol to vesicle suspensions to achieve a final lipid/probe ratio of 200:1. The mixtures were vortexed thoroughly and incubated until the fluorescence intensity did not increase further with time (∼30 min). Aliquots of peptide were then added to the vesicle suspensions, and fluorescence anisotropy was recorded after10 min incubation. All fluorescence measurements were performed using an SLM 48000 spectrofluorometer (SLM Aminco, Urbana, IL). The excitation wavelength was 360 nm, with excitation slits of 4 and 4 nm and 450 cutoff filters in the T-format emission paths.

C6-NBD-PC and TMA-DPH lifetime measurements

C6-NBD-PC and TMA-DPH, both in methanol, were added to vesicle samples to give 200:1 lipid/probe ratios and incubated with stirring until constant fluorescence intensity was observed. For both probes, increasing quantities of peptide were titrated into a solution containing 0.2 mM DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH and DOPC vesicles, and phase shift and modulation ratios were collected from continuously stirred samples using the SLM 48000 MHF spectrofluorometer equipped with a Coherent Inova 90 argon-ion laser. Details of instrument setup, data acquisition, and analysis are described in an earlier publication (36).

Depth of tryptophan residue of fusion peptides in membranes

We have measured depth of penetration of the single peptide tryptophan residue inside the lipid bilayers using the parallax method (37). Lipids labeled with bromine at carbons 6-7 and 11-12 in the acyl chain were used as tryptophan quenchers (20 mol% brominated PCs in place of DOPC). Aliquots of peptide solution were added to vesicle suspensions to achieve a final peptide/lipid ratio of 1:400 and incubated for 10 min before recording tryptophan fluorescence intensity. The signal from an identical sample without peptide was subtracted from the data to reveal the Br quenching.

Depth of tryptophan was calculated according to published methods (37):

|

(1) |

where ZcF is the depth of fluorophore from the center of the bilayer, Lc1 is the distance of the center of the bilayer from the shallow quencher 1, L21 is the difference in depth between the two quenchers, and C is the two-dimensional quencher concentration in the plane of the membrane in units of molecules per unit area {(mol fraction of quencher lipid in total lipid)/(area of a PC molecule)}. F1 and F2 are the measured normalized fluorescence intensities from samples containing the 6-7 dibromo and 11-12 dibromo quenchers, respectively. The area of a PC molecule was taken as 70 Å2 (38), and the average bromine distances from the center of the bilayer were taken to be 10.8 and 6.3 Å for the 6-7 Br-PC and 11-12 Br-PC, respectively (39). Errors in the depth of penetration from repeats with a single vesicle preparation were 1–2% for HA peptide and 5–10% for gp41 peptide. The parallex method is valid when all peptides are bound to the membrane, which they should be under our conditions of excess lipid.

CD spectroscopy

Circular dichroism spectra were measured using an Applied Photophysics model PiStar-180 spectropolarimeter (Surrey, UK) located in the UNC Macromolecular Interactions Facility. Data were collected using 0.5-mm pathlength cells at wavelengths from 250 to 200 nm at intervals of 0.2 nm. Estimates of peptide secondary structure under different conditions were made using published procedures (40). The peptide concentration was 40 μM, and the lipid concentration was 2 mM. Small aliquots of peptide solution in DMSO were dried in thin films on the surface of 3.5-ml brown vials. The films were frozen using dry ice, and dried under high vacuum overnight. Preformed SUVs were added to the vials and vortexed for 30 min to transfer peptide to the membranes.

Infrared spectroscopy

Polarized attenuated total internal reflection Fourier-transform infrared (PATIR-FTIR) spectroscopy was performed using a FTS-60A spectrometer (BioRad Digilab, Waltham MA) equipped with a liquid-nitrogen cooled MCT detector coupled via a germanium internal reflection element to a lipid film balance as previously described (41). Monolayers were prepared by applying phospholipids dissolved in hexane/methanol (9:1) to the buffer surface in a Langmuir trough. The lipid spread at the air-water interface was compressed to a surface pressure of 20 mN/m, and applied onto the internal reflection element by placing an octadecyltrichlorosilane-treated germanium internal reflection crystal flat onto the monolayer (42,43).

After recording a baseline single-beam spectrum, aliquots of the peptide (∼10 μg) dissolved in deuterated DMSO were added to the continuously stirred buffer subphase to a final concentration of ∼0.8 μM. Minor contributions to the amide I spectrum arising from SM are included in the baseline spectrum, and therefore do not contribute to the final amide I spectrum of the peptide. The DMSO concentration in the buffer subphase was always <0.3 wt%. Polarized infrared absorption spectra were recorded by directing light from the Bio-Rad FTIR spectrometer through a polarizer oriented either parallel or perpendicular to the plane defined by the incident beam of light (incidence angle = 45°) and the perpendicular axis of the germanium crystal. After a series of internal reflections, the beam was directed to an external detector (42). The depth of evanescent field penetration into the buffer subphase at the site of each internal reflection is ∼0.5 μM, so that the contribution of peptide in bulk solution to the spectra is negligible, and virtually all the signal arises from membrane-bound peptide. All spectra were collected in the rapid scan mode as 1024 coadded interferograms, with a resolution of 2 cm−1, scanning speed of 20 MHz, triangular apodization, and one level of zero filling. All experiments were performed at 27°C. A single horizontal baseline correction was applied to each spectrum, but no smoothing, deconvolution, vapor subtraction, or other aesthetic processing.

Dichroic ratios,  were evaluated using linked analysis (43) and integrated areas of the amide I absorption bands,

were evaluated using linked analysis (43) and integrated areas of the amide I absorption bands,  arising from the backbone peptide groups. For an angle θ between the absorption moment and the surface normal,

arising from the backbone peptide groups. For an angle θ between the absorption moment and the surface normal,  indicates either isotropic disorder, uniform orientation at

indicates either isotropic disorder, uniform orientation at  (the magic angle), or any distribution of orientations for which

(the magic angle), or any distribution of orientations for which  Accordingly,

Accordingly,  indicates that absorption moments have preferential orientation more perpendicular to the plane of the membrane than the magic angle, whereas

indicates that absorption moments have preferential orientation more perpendicular to the plane of the membrane than the magic angle, whereas  indicates preferential orientation more parallel to the membrane than the magic angle. The range of possible values for the dichroic ratio has a physical minimum at RZ = 0.88, corresponding to an orientation that is perfectly parallel to the membrane (44). The fractional contributions of different band components to the overall amide I band were calculated for the conditions of internal reflection and polarized light as previously described (45).

indicates preferential orientation more parallel to the membrane than the magic angle. The range of possible values for the dichroic ratio has a physical minimum at RZ = 0.88, corresponding to an orientation that is perfectly parallel to the membrane (44). The fractional contributions of different band components to the overall amide I band were calculated for the conditions of internal reflection and polarized light as previously described (45).

RESULTS

Effect of peptide on bilayer properties

Effects of peptides on outer leaflet membrane packing

The effect of fusion peptides on membrane surface properties was examined using a fluorescent probe, C6-NBD-PC, which is reported to partition between the upper region of the bilayer and micelles (37). Because of this partitioning, the fluorescence lifetime of this probe reflects the lifetimes in both membrane and micelle environments, with the average lifetime reflecting the partition coefficient between these two phases (36), making C6-NBD-PC a sensitive function of membrane surface free energy (i.e., surface tension) and lipid packing within membrane outer leaflets (46). Measured phase shift and modulation ratios of frequency-modulated C6-NBD-PC fluorescence at different lipid/peptide ratios in vesicles composed of DOPC or DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH were well described by three lifetime components. The smallest of these components was independent of peptide/lipid ratio and was thus taken as the probe lifetime in a micelle, whereas the other two were taken to reflect C6-NBD-PC partitioned into the membrane. Fig. 1 shows the peptide-induced shift in the fluorescence lifetime of membrane-associated C6-NBD-PC (left panels), as well as the mol fraction of C6-NBD-PC in the membranes as a function of the ratio of added-peptide/total-lipid concentration (right panels). The average C6-NBD-PC lifetime in DOPC SUVs (panel A), DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs (panel B), and DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH LUVs (panel C) increased with increasing peptide concentrations for both HA (triangles) and gp41 (circles) fusion peptides. As expected from reports that HA peptide binds poorly to membranes at neutral pH (18,47), our data indicate that the HA peptide had no effect on C6-NBD-PC lifetime at pH 7.5 (panel A, open triangles). The effect of the gp41 peptide, on the other hand, was independent of pH (Fig. 1 A, solid circles, pH 7.5, and open circles, pH 5.5), consistent with reports that the gp41 peptide binds to membranes at both neutral and acidic pH (48). For these reasons, we performed most of our experiments with HA peptide at pH 5.5 and with gp41 peptide at pH 7.5. For all three lipid systems, the effect of the HA fusion peptide on C6-NBD-PC lifetime was greater than for gp41 peptide, although the difference was minimal for fusogenic DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of fusion peptides on the surface properties of fusogenic and nonfusogenic vesicles. The fluorescence lifetime of C6NBD-PC in the presence of peptide relative to the lifetime in the absence of peptide (Delta Lifetime) is presented as a function of gp41 (circles) and HA fusion (triangles) peptide/lipid ratios in panels A, B, and C. The mol fractions (Xmem) of C6-NBD-PC partitioned into DOPC SUVs (nonfusogenic), DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs (fusogenic), and LUVs (nonfusogenic) are shown in panels D, E, and F. Open and solid symbols show data obtained at pH 7.5 and 5.5, respectively, and 23°C.

The influence of both peptides on C6-NBD-PC lifetime reached a saturating level at high peptide concentration, but had not saturated by a peptide/lipid ratio of roughly 1/30 for DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH LUVs or DOPC SUVs. As a control, we monitored binding of both peptides to the different vesicles used in this study as described previously (23,24). The resulting binding parameters are collected in Table 1. The fraction of membrane surface sites occupied (fS) on DOPC SUVs was calculated (49) from these binding parameters. For reference, we give values at low surface occupancy (P/L = 1/200 ⇒ fS = 0.06 for HA and 0.05 for gp41 peptides) and high surface occupancy (P/L = 1/25 ⇒ fS = 0.51 for HA and 0.39 for gp41 peptides). At low P/L, both peptides were well below surface saturation. Under these conditions, nearly all peptide was bound. At high P/L, surface occupancy was still fairly low, but surface crowding cannot be ignored at high peptide concentration.

TABLE 1.

Binding parameters for the association of fusion peptides with vesicle membranes

These observations suggest that peptide binding caused either: 1), C6-NBD-PC to partition deeper into the membrane outer leaflet, 2), water not to penetrate as deeply into the outer leaflet, or 3), inhibited motions and increased packing order in the neighborhood of the probe. We addressed all three possibilities with additional experiments reported below.

For all three lipid systems, increasing peptide/lipid ratio decreased the mol fraction of C6-NBD-PC partitioned into the membranes, although the effects were qualitatively quite different for curved and uncurved vesicles (compare panels D and E of Fig. 1 to panel F). The two peptides inhibited C6-NBD-PC partitioning into uncurved vesicles equally, but had very different effects for curved vesicles (panels D and E). Even a small amount of HA peptide significantly inhibited C6-NBD-PC partitioning from micelles into all three membrane systems. However, binding of gp41 peptide to SUVs seemed to occur with no effect on C6-NBD-PC partitioning into these membranes up to a P/L ratio of 1:50, whereupon partitioning decreased dramatically as it did for HA peptide. These results suggest that both fusion peptides reduced free volume in the membrane outer leaflet (i.e., increased lateral packing pressure), although the gp41 peptide had to reach a critical surface concentration on highly curved membranes before this effect was observed. Because lifetime data in the left panels indicate that the gp41 peptide binds to DOPC and DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs, it may be that it assumes a different structure on these membranes at low and high surface concentrations. Interestingly, HA peptide (23) is more active in destabilizing membrane vesicles than is the gp41 peptide (24) at low peptide concentrations in the absence of PEG. Thus, the abilities of these two peptides to destabilize vesicles correlate with their abilities to increase lateral pressure in the vesicle outer leaflet. However, the gp41 peptide at low peptide surface concentrations still enhanced the rate of PEG-mediated DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUV fusion (24), meaning that the gp41 structure at low surface occupancy can promote fusion, whereas at high surface occupancy it promotes rupture.

Effects of peptides on acyl chain packing

DPH locates in the hydrocarbon region of phospholipid bilayers and its fluorescence anisotropy has long been used to monitor chain-packing order in that region (50). Fig. 2 shows the change of DPH fluorescence anisotropy as a function of HA (left panels) and gp41 (right panels) peptide/lipid ratio in highly curved DOPC SUVs (nonfusogenic), DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs (fusogenic), and uncurved DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH LUVs (nonfusogenic). As we saw for lateral packing pressure as detected by C6-NBD-PC partitioning, the gp41 peptide had little effect on DPH anisotropy at low surface occupancies of peptide but did cause an increase in chain packing order above a critical peptide/lipid ratio of ∼1:67. The HA peptide also caused an increase in acyl chain packing as reported by DPH, but it did so at all peptide surface occupancies. The results show that both peptides increase packing in the acyl chain region, but, along with the effects on surface packing recorded in Fig. 1, suggest that the HA and gp41 peptides have different effects on membranes at low surface occupancies. These results further support the conclusion that the gp41 peptide has a different conformation at low (<1:67) and high surface concentrations.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of fusion peptides on acyl chain packing. DPH fluorescence emission anisotropy in DOPC SUVs, DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH (35:30:15:20) SUVs and DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH LUVs as a function of HA (left panels) and gp41 (right panels) peptide/lipid ratio. The experiment was done at 23°C.

Effect of peptides at the interface

TMA-DPH locates close to the membrane interface and senses membrane structure in this region (51). The fluorescence anisotropy of TMA-DPH was thus used as a measure of the chain packing in the upper reaches of the bilayer outer leaflet. In Fig. 3, we present the fluorescence emission anisotropy of TMA-DPH in DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs and LUVs and in DOPC SUVs as a function of HA (triangles) and gp41 (circles) fusion peptide/lipid ratio. TMA-DPH anisotropy increased somewhat with peptide concentration in all cases. Although TMA-DPH fluorescence anisotropy was different for different membranes, the results show that the packing in the interfacial region of all membrane bilayers increased similarly with addition of both fusion peptides (3–4% over a range of 0–1:25 peptide/lipid). This increase in packing order was much smaller than the increase in packing induced in the lower regions of the bilayer (Fig. 2; 21 and 10% for HA and gp41 peptides, respectively). These results suggest that both peptides increased packing order in the acyl chain region more than at the interface. We note that a critical gp41 surface concentration was not needed to see the effect on interfacial packing.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of fusion peptides on the interfacial region of vesicle membranes. The TMA-DPH fluorescence emission anisotropy in DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH (35:30:15:20) SUVs, LUVs, and DOPC SUVs is shown as a function of HA (▴) and gp41 (•) peptide/lipid ratio. All values represent the average of three measurements with representative error bars shown.

Effects of fusion peptides on bilayer water penetration

Water penetration into the interface region causes a drop in TMA-DPH fluorescence lifetime due to an exchangeable hydrogen atom that should be located in the interface region of the bilayer (51). The drop in lifetime is reversed by replacement of H2O with D2O (36). We determined the two lifetime components required to describe the excited state behavior of TMA-DPH in DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs at various lipid/peptide ratios. To judge water penetration, we calculated average lifetimes measured in D2O ( ) and in H2O (

) and in H2O ( ) (36). The closer the

) (36). The closer the  :

: ratio is to 1, the less water penetrates into the interface region of the membrane outer leaflet (51). Our results (figure shown as a supplement) clearly showed that neither peptide affected water penetration into the outer leaflet interface region of either fusogenic (DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH) or nonfusogenic (DOPC) SUVs, even at high peptide concentrations.

ratio is to 1, the less water penetrates into the interface region of the membrane outer leaflet (51). Our results (figure shown as a supplement) clearly showed that neither peptide affected water penetration into the outer leaflet interface region of either fusogenic (DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH) or nonfusogenic (DOPC) SUVs, even at high peptide concentrations.

Peptide structure on the membrane

Depth of peptide penetration

The fusion peptides we have studied both have a single Trp residue. We have used these residues as reporter groups to judge the location of the peptides in the bilayer. The locations of these Trp residues were gauged by quenching of Trp indole fluorescence intensity based on the parallax method (37). We used two dibromo lipids (6-7 and 11-12 Br-PC) as quenchers. Trp fluorescence was quenched (quenching results are not shown here, but are given in a supplement) more by the 6-7 Br-PC than by the 11-12 Br-PC, suggesting that the indole moiety was closer to the C6-C7 carbons in the lipid acyl chain than to the C11-C12 carbons. Equation 1 in Methods was used to estimate the location of indole moieties in HA and gp41 peptides in the bilayers of membranes of different compositions, with the distances of indoles from the center of the bilayer reported in Table 2. These results indicate that both peptides penetrate into the acyl chain region of lipid bilayers. The quenching efficiency was less for the gp41 than for the HA peptide and consequently the error of depth estimation was greater for the gp41 peptide, even though we obtained reproducible results with both peptides. Our results (8.8–9.3 Å from the bilayer center) for HA peptide are reasonably consistent with previous estimates (52,53), but differ slightly (just beyond the limits of precision) between membranes of different inherent fusogenicity and curvature stress.

TABLE 2.

Distance of indole group of Trp residue of HA and gp41 fusion peptide from the center of the bilayer of membrane vesicles

| Peptide | L/P ratio | Vesicles | Distance from bilayer center (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gp41 | 400:1 | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH, SUV | 8.67 |

| 400:1 | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH, LUV | 8.60 | |

| 400:1 | DOPC, SUV | 8.65 | |

| 50:1 | DOPC, SUV | 8.60 | |

| 50:1 | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH, SUV | 8.55 | |

| HA | 400:1 | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH, SUV | 8.88 |

| 400:1 | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH, LUV | 8.97 | |

| 400:1 | DOPC, SUV | 9.30 |

To achieve a 50:1 lipid/peptide ratio in some experiments with gp41 peptide, we have added wild-type (no Trp) peptide along with the mutant peptide. This maintained a low surface concentration of Trp-mutant peptide (L/P of 400:1) that allowed us to measure Trp depth in the membrane without interference from high lipid to Trp containing peptide ratio but over all high peptide concentration.

The distance of gp41 peptide Trp indole from the bilayer center was roughly the same for the more fusogenic and less fusogenic lipid compositions, at least within the precision of these measurements. For both peptides, the apparent Trp location was independent of bilayer curvature. Penetration of gp41 peptide into the bilayer was independent of peptide concentration. Penetration of gp41 was unchanged even at peptide/lipid ratios (1:50) above the threshold of aggregation/rupture (∼1:250 when PEG and peptide are both present). This result demonstrates that high leakage or rupture of vesicle in the presence of high peptide concentrations is not simply due to greater penetration of peptide into the acyl chain region.

Secondary structure/orientation of fusion peptides on vesicles

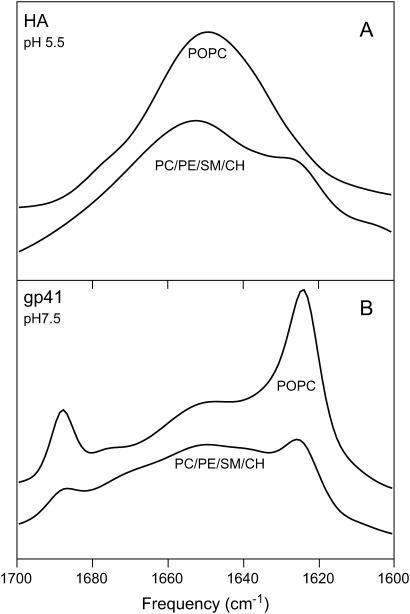

Numerous CD experiments have established that the HA fusion peptide adopts a largely α-helical structure when it associates with membranes (18), and we have therefore not pursued further CD studies of this peptide. We did, however, examine this peptide by PATIR-FTIR, because previous FTIR studies of dried HA-peptide-lipid suspensions suggest that the peptide helix orients at an intermediate angle to the bilayer normal (45–70°) (54). In our hands, the HA peptide did not adsorb well to monolayer membranes of either type at pD 7.5, consistent with results obtained using lipid vesicles (Fig. 1 A). Due to weak signals and inconsistent results, spectra collected under these conditions were not quantitatively analyzed. HA peptide at pD 5.5 adsorbed well onto POPC monolayers, exhibiting a single major broad amide I component centered at 1649 cm−1 and a minor component at 1677 cm−1 (Fig. 4 A), characteristic of α-helix. Compared to POPC monolayers, spectra collected on DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH monolayers exhibit an additional distinct component at 1625 cm−1 (Fig. 4 A), suggesting a small and ill-defined change in secondary structure (perhaps some β or more complex structure). Our PATIR-FTIR results agree with previously published CD (17–19,47,55–57) and FTIR (58–60) studies of the HA fusion peptide in showing an α-helix conformation when this peptide binds to liposome membranes at low pH. However, our studies differ from previous studies in that they were performed on well-oriented lipid monolayers, making them suitable for quantitative analysis of peptide orientation (43). Assuming that the peptide is predominantly helical under these conditions, this analysis yields dichroic ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, indicating either that the peptide exhibits only a modest amount of orientational order or is oriented roughly at the magic angle with respect to the bilayer plane.

FIGURE 4.

PATIR-FTIR amide I spectra of HA peptide (A) and gp41 peptide (B) on monolayers of POPC and DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH. Parallel-polarized spectra are shown; perpendicularly polarized spectra had similar shapes but slightly lower amplitudes.

The structure of gp41 peptide on neutral membranes is less extensively characterized in the literature, and thus the secondary structure of the HIV gp41 fusion peptide bound to vesicles and monolayers was examined by both CD and PATIR-FTIR spectroscopy. CD spectra of gp41 indicate that it had negligible helical content on fusogenic DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH SUVs and nonfusogenic DOPC vesicles (figure shown as a supplement). Similar results were obtained with DOPC vesicles containing 5 and 10 mol% DOPS. Apparent helicity increased to ∼20% in vesicles containing 50 mol% DOPS (figure shown as a supplement), consistent with most earlier studies showing that the gp41 peptide forms an α-helix on charged membranes (22,25,61–63).

PATIR-FTIR spectra of gp41 fusion peptide exhibited a widely split amide I band on POPC monolayers at pD 5.5 (data not shown) and at pD 7.5 (Fig. 4 B). The band components at 1625 and 1688 cm−1 that dominated the amide I spectrum in POPC monolayers, are present but less prominent in DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH monolayers. This widely split amide I band is characteristic of antiparallel β-sheet secondary structure (64,65). Quantitative analysis indicates that gp41 was highly ordered under all conditions, with dichroic ratios between 1.2 and 1.4 for its 1625 cm−1 component (Table 3). This component is aligned parallel to the hydrogen bonds in an antiparallel β-sheet, so these dichroism results indicate that hydrogen bonds in the sheet are parallel to the membrane surface. If we view the β-sheet as a thin rectangle with one minor axis parallel to the H-bonds and a long axis being the run of the sheet, the H-bond axis is parallel to the plane of the membrane but the long axis may be parallel or at an angle to the membrane normal. Other components in the spectra reveal little order, and do not support specific interpretations.

TABLE 3.

Recovered amide I components dichroic ratios for fusion peptides

| gp41 (pD 7.5)*

|

HA (pD 5.5)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPC | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH | POPC | DOPC/DOPE/SM/CH | ||

| 1614 cm−1 | RZ | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | – | – |

| % | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | – | – | |

| 1625 cm−1 | RZ | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | – | 1.2 ± 0.0 |

| % | 35.9 ± 2.7 | 20.3 ± 5.3 | – | 19.0 ± 7.2 | |

| 1632 cm−1 | RZ | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | – | – |

| % | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | – | – | |

| 1649 cm−1 | RZ | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| % | 22.1 ± 1.2 | 30.2 ± 3.0 | 81.5 ± 1.1 | 73.1 ± 6.4 | |

| 1677 cm−1 | RZ | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.0 |

| % | 13.5 ± 1.3 | 25.3 ± 4.7 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 3.2 | |

| 1688 cm−1 | RZ | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | – | – |

| % | 6.9 ± 0.0 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | – | – | |

| Minor components | % | 7.8 | 3.8 | 12.3 | 0.0 |

Values listed are the average and range of two measurements. The β-sheet orientation, γ, is calculated as described in methods. Percentages in each column are amide I component areas and total 100%.

DISCUSSION

Effects of fusion peptides on bilayer structure

The HA peptide had a somewhat greater effect on bilayer structure than gp41 peptide. Consistent with this, the gp41 peptide had to reach a critical surface concentration (P/L ∼ 1:60) to have the same effects on outer leaflet free volume (Fig. 1) and interior acyl chain order (Fig. 2). This implies that the HA peptide penetrates the outer leaflet different from the gp41 peptide. Nonetheless, both peptides increased packing in the interface region of the outer leaflet to some extent (Fig. 3) but to a much smaller extent than they increased interior packing (Fig. 2). These results were certainly unanticipated, because it is often assumed that the ability of fusion peptides to promote fusion is related to their ability to disrupt the target membrane outer leaflet, a process that would expose the hydrocarbon interior to water and increase surface tension.

Determining fusion peptide structure on bilayers

The fusogenic conformation of fusion peptides remains difficult to define for several reasons. First, it is inherently difficult to determine the structure of membrane-associated proteins, and especially of peptides, whose structure is usually less well defined than for a protein. Second, the structure of a fusion peptide may depend on the nature of the surface to which it is bound (18,55,56,66,67). Third, the structure may also depend on the concentration of peptide or other components (water, ions) at the surface (68–70). We turned to a combination of fluorescence, CD, and PATIR-FTIR spectroscopies to gain insights into peptide structure. Because infrared spectra are always weak relative to UV spectra, it is necessary to use high P/L ratios (in our case, nominally 1:10) to obtain interpretable data for clearly defined lipid monolayers interacting with peptide under full hydration and defined buffer conditions. Thus, our results on peptide structure on membranes (CD) or monolayers (PATIR-FTIR) are obtained at much higher surface concentrations (P/L = 1/50 for CD and P/L = 1/10 for FTIR) than we have used to study peptide enhancement of PEG-mediated fusion (P/L < 1:200) (23,24). We acknowledge that the chemical nature of membrane interface and thus the peptide structure may be different at the high P/L ratios at which our CD and FTIR experiments are performed than they are at the low ratios at which we have examined the effects of peptides on fusion. This is an ambiguity with which nearly any structural studies must live, and we acknowledge this in our discussion. Although other FTIR studies have been performed at much lower P/L ratios, the price of doing so is that these studies are performed on lipid pastes in which solution conditions are obscure. We accept the uncertainty associated with a saturated surface concentration of peptide to examine peptide structure under defined solution conditions of hydration, pH, ionic strength, and lipid structure (71).

Fusion peptide structure and fusogenicity

A recently published model of HA fusion peptide structure (72) is based on NMR data obtained with detergent-solubilized peptide and then electron spin resonance data on membrane-bound peptide. In this model, an N-terminal helix penetrates the bilayer at roughly 30° to the bilayer surface. A C-terminal distorted helix lies roughly along the bilayer surface at pH 7, allowing E-11 and N-12 to be in the aqueous layer above the membrane. These helical regions are linked by a region suggested by molecular dynamics simulation to be flexible (73) and containing G-13 as part of a helix-breaking motif crucial to fusion peptide function (27). This model was obtained with the fusion peptide acting as a “guest” attached to a hydrophilic C-terminal “host” peptide, meaning that the C-terminal portion attached to the host could be distorted from the structure formed by a host-free peptide.

Our results indicate that Trp-14 is located fairly near the interface with its indole side chain located ∼9 Å from the center of the bilayer (Table 2). Our PATIR-FTIR data support a largely helical structure. Our model places the N-terminal region at roughly a 30° angle to the surface so that hydrophobic residues can locate to the midsection of the monolayer. This is based on our fluorescence results that the hydrophobic packing in the membrane is increased due to peptide binding and on the dichroic ratio of the helical amide I band (Table 3). The arrangement of polar residues in the C-terminus (i,i + 4) suggests a distorted helix. To satisfy the FTIR result, we assumed that the small helical region at the C-terminus is also bent into the monolayer but at a small angle of opposite sign to the penetration of the N-terminus. The chain then returns to the surface to place Asp-19 in the water layer above the bilayer. This model of the HA fusion peptide is displayed in Fig. 5. The rough agreement of our qualitative model for HA fusion peptide with the NMR-based model (72) both suggests that the host peptide used to obtain the NMR model did not significantly distort the HA fusion peptide structure and lends credence to the reasoning behind the model adopted here.

FIGURE 5.

Model of HA and gp41 peptides associated with lipid bilayers based on depth of penetration and FTIR results. The detailed arguments that led to these models are described in the Discussion. The models reflect our hypothesis that, even though the two peptides adopt somewhat different secondary structures, they interact with the bilayer with basically the same structural organization, and promote fusion by the same mechanism. This involves bilayer penetration by the hydrophobic N-terminus, thereby compensating for hydrophobic mismatch and stabilizing fusion intermediates leading to pore formation.

Unlike the HA peptide, the literature on the gp41 fusion peptide suggests a mixture of secondary structures, with many opinions on what determines the balance between structures: 1), surface concentration; 2), peptide oligomeric state; 3), membrane composition; and 4), membrane curvature. Because of experimental limitations, we could not address sensitivity to membrane curvature, although we have addressed all the other issues mentioned.

Although there is agreement that the gp41 peptide is primarily helical on acidic-lipid-containing membranes (25,61,63), there is disagreement about the conformation on a neutral membrane. Some report α-helix at P/L ratios from 1:25 to 1:2000 (29), whereas most find β-structure from 1:50 to 1:800 P/L (22,61,63), but there are no reports of a variation in gp41 peptide structure with change in surface concentration. Consistent with this, our results show that the indole of Trp-8 in the gp41 mutant is located similarly with respect to the bilayer center at low (P/L = 1:400) and high (P/L = 1:50) surface concentrations (Table 2), although this does not absolutely rule out a change in secondary structure with surface concentration. At both 1:50 and 1:10 P/L ratios, our results indicate a highly ordered structure with the dominant secondary structure being antiparallel β-sheet. This could be intra- or intermolecular β-sheet, as illustrated in Fig. 5 (bottom and top right panels). Our observation that a threshold surface concentration was needed to see the effects of gp41 fusion peptide on membrane outer-leaflet structure (Figs. 1 and 2) supports an intermolecular β-sheet model at surface concentrations above ∼1:60. Both possibilities are presented in the lower panel of Fig. 5. Both our models (intra- or intermolecular β-sheet) locate the C-terminal charged residues (also with an i, i + 4 repeat consistent with a distorted amphipathic helical turn) at the membrane interface and confine the β-sheet to the N-terminal region. Either model properly places the indole relative to the membrane center and places hydrophobic residues so that they reach into the interior of the bilayer, where our fluorescence data indicate that a portion of the peptide must be located. The angle between the β-sheet axis and the plane of the membrane is not implied by our PATIR-FTIR data, but is consistent with these data and allows for penetration of the hydrophobic residues into the regions of the bilayer most affected by peptide binding to membranes.

Recent solid-state NMR studies provide direct spin-coupling demonstration of β-sheet conformation involving residues V2, F8, F11, and A15 at P/L of 1:20, although it was not possible to distinguish between interpeptide or intrapeptide (74). This same solid-state NMR study failed to detect significant structure in the C-terminal region, also consistent with the model presented here.

Effect of membrane structure on peptide structure

Aside from the clear effect of basic membrane charge on the gp41 peptide, we cannot derive from our results (Fig. 4 and Table 3) a clear correlation between membrane structure (fusogenic versus nonfusogenic) and either HA or gp41 fusion peptide structure beyond acknowledging that the structures of these fusion peptides are sensitive to the structure of the membrane on which it is located, even for neutral membranes.

Analogous HA and gp41 fusion peptide structures: a hypothesis for a structure/fusion relationship

A recent two-dimensional NMR structure of gp41 fusion peptide associated with sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles shows the N-terminus as mainly micelle-embedded α-helix, with a flexible Gly-bend region (Leu-12-Gly-13-Ala-14-Ala-15-Gly-16) joining this to a surface-located C-terminus (62). This arrangement is quite analogous to that described for the HA fusion peptide in dodecylphosphocholine micelles (72). Basic polar residue pairs on the C-terminal side of the flexible link (Ser-17-Thr-18, Arg-22-Ser-23) of gp41 and the acidic residues in the C-terminus of HA fusion peptide (Glu-15, Asp-19) should be exposed to water. The (i,i + 4 or 5) repeat of these polar residues in both the gp41 and HA fusion peptides is consistent with a distorted helix, with the polar residues bending this so that they can occupy the membrane interface. The regions of both the HA and gp41 fusion peptides on the N-terminal side of the flexible region are hydrophobic. Because either a β-sheet or an α-helix will satisfy the H-bonding requirements of these hydrophobic N-terminal portions, either structure should be roughly equivalent thermodynamically, except that there is not a clear β-turn motif in the middle of either N-terminal sequence. However, the turn potential for the gp41 peptide is greater than for the HA peptide, which has a more clear helical propensity. Thus, we suspect that either peptide, under appropriate surface conditions, could adopt either secondary structure.

In the models presented in Fig. 5, both fusion peptides have roughly an inverted V-shape. Our hypothesis is that the angle of the V determines the fusogenic conformation of either fusion peptide and depends on the charge on the membrane and on the charged C-terminal residues of the peptides. In this hypothesis, both the Gly-bend region in the middle of the peptides and the polar residues in the bend and C-terminus (Ser-17, Thr-18 and Arg-22, Ser-23 pairs in gp41 and Glu-15 and Asp-19 in HA) are critical to the fusion conformation. The polar residues dictate the orientation of the bend/C-terminus with respect to the membrane surface and thus make the structure of each peptide very sensitive to pH (HA peptide) and to both the charge and packing of the membrane (gp41 peptide). We suggest that a fusion-promoting conformation of either peptide is one that allows the C-terminal polar residues the most freedom to leave the aqueous interface and penetrate the membrane outer leaflet (i.e., adopt a more bent conformation). The low pH conformation α-helical form of the HA fusion peptide is widely accepted as fusogenic (18,26,56), and the NMR-based model for HA peptide shows that this conformation allows greater penetration of the hydrophobic N-terminus into the outer leaflet than does the neutral pH conformation (72). The gp41 peptide promotes fusion on neutral, well-packed, and highly curved membranes (24), which we show here support a β-sheet in its N-terminus. Based on the fact that the gp41 peptide has a different effect on membrane packing than the α-helical HA peptide (Figs. 1 and 2), we conclude that the fusogenic conformation of the gp41 peptide under our experimental conditions is an intrapeptide β-sheet that allows the N-terminal half of the peptide to penetrate the outer leaflet, although not as effectively as the α-helix of the HA peptide. On membranes containing acidic lipids, the basic C-terminal residues of gp41 would be more tightly anchored to the aqueous region just above the membrane surface, leading to the α-helical N-terminus that would nonetheless be inactive because of a less bent conformation.

This offers a possible biological rationalization for the gp41 peptide's sensitivity to negative surface charge. The gp41 peptide has basic residues in the same C-terminal helical turn positions where the HA peptide has acidic amino acids. Apoptotic lymphocytes are rapidly coated with exposed phosphatidylserine (75,76). If our hypothesis is correct, this surface would favor an α-helical N-terminal region, whereas the phosphatidylserine-depleted surface of a healthy lymphocyte would favor an N-terminal β-sheet that favored fusion and infection.

The role of fusion peptides in promoting fusion: intrinsic curvature versus HMM

The simian immunodeficiency virus destabilizes lamellar and promotes hexagonal phase, leading to the speculation that it has an effective negative intrinsic curvature (77). This would be expected to frustrate packing, especially of the highly positively curved outer leaflet of SUVs. Instead, both peptides had the opposite effect: they decreased surface tension and filled hydrophobic space within the outer monolayer, especially for SUVs (Fig. 1 B) than for LUVs (Fig. 1 C). Consistent with this, neither peptide promoted water penetration of the outer leaflet. Indeed, if these peptides can relieve the curvature stress of SUVs, they should inhibit fusion of these vesicles. Instead they promote PEG-mediated fusion only of highly curved membranes, except in the presence of hexadecane, when they inhibit fusion (23,24). Hexadecane is a hydrocarbon shown to occupy space in the hydrophobic mismatch (HMM) region of hexagonal phase (78). Its presence in a membrane favors fusion by promoting conversion of initial intermediate to a pore (79,80) and competes with the fusion promoting effect of fusion peptides (24). Thus, both the effects of fusion peptides on bilayer structure (Figs. 1 and 2) and their effects on fusion (23,24) support the hypothesis that the ability to fill space within the hydrophobic region of the outer monolayer promotes fusion. It may be that fusion peptides also contribute an effective negative intrinsic curvature (77), but this possibility must be addressed by determining their effect on the hexagonal phase transition in the presence of hexadecane to eliminate the possibility that the peptides act by reducing unfavorable HMM free energy. These experiments are underway, as are experiments to determine the importance of the Gly-bends and hydrophobic N-terminals, other key elements of our hypothesis.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ashetosh Tripathy of the University of North Carolina Macromolecular Interactions Facility for help with CD measurements.

This work was supported by the United States Public Health Service (GM32707 to B.R.L., GM54617 to P.H.A., and HL68186 to V.K.).

Abbreviations used: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HA, hemagglutinin of infuenza virus; DOPC, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-sn-phosphatidylcholine; DOPS, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-sn-phosphatidylserine; POPG, palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol; POPC, palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine; SOPC, 1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-3sn-phosphatidylcholine; 6-7 Bromo-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl (6-7 dibromo)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; 11-12 Bromo-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl (6-7 dibromo)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; SM, sphingomyelin (bovine brain); CH, cholesterol; gp41, transmembrane subunit of the HIV envelope glycoprotein; DPH, 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene; TMA-DPH, 1-[(4-trimethylamino)phenyl]-6-phenylhexa-1,3,5-triene; C6-NBD-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-N-(4-nitrobenxo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole)aminohexanoyl-phosphatidyl-choline; SUV, small unilamellar vesicles; LUV, large unilamellar vesicles; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); TES, N-[tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]2-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid.

References

- 1.White, J. M. 1990. Viral and cellular membrane fusion proteins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 52:675–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leikina, E., I. Markovic, L. V. Chernomordik, and M. M. Kozlov. 2000. Delay of influenza hemagglutinin refolding into a fusion-competent conformation by receptor binding: a hypothesis. Biophys. J. 79:1415–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markosyan, R. M., G. B. Melikyan, and F. S. Cohen. 1999. Tension of membranes expressing the hemagglutinin of influenza virus inhibits fusion. Biophys. J. 77:943–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitrov, D. S., H. Golding, and R. Blumenthal. 1991. Initial stages of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated cell fusion monitored by a new assay based on redistribution of fluorescent dyes. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 7:799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freed, E. O., D. J. Myers, and R. Risser. 1990. Characterization of the fusion domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:4650–4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasky, L. A., G. Nakamura, D. H. Smith, C. Fennie, C. Shimasaki, E. Patzer, P. Berman, T. Gregory, and D. J. Capon. 1987. Delineation of a region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein critical for interaction with the CD4 receptor. Cell. 50:975–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dragic, T., V. Litwin, G. P. Allaway, S. R. Martin, Y. Huang, K. A. Nagashima, C. Cayanan, P. J. Maddon, R. A. Koup, J. P. Moore, and W. A. Paxton. 1996. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC–CKR-5. Nature. 381:667–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson, D. 1996. Cofactors provide the entry keys. HIV-1. Curr. Biol. 6:1051–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broder, C. C., and D. S. Dimitrov. 1996. HIV and the 7-transmembrane domain receptors. Pathobiology. 64:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore, J. P., B. A. Jameson, R. A. Weiss, and Q. Sattentau. 1993. The HIV-Cell Fusion Reaction. J. Bentz, editor. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, Ann Arbor, MI, London, UK, and Tokyo, Japan.

- 11.Durell, S. R., I. Martin, J. M. Ruysschaert, Y. Shai, and R. Blumenthal. 1997. What studies of fusion peptides tell us about viral envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 14:97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughson, F. M. 1995. Structural characterization of viral fusion proteins. Curr. Biol. 5:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore, J. P., B. A. Jameson, R. A. Weiss, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1993. Viral Fusion Mechanisms. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 14.Gething, M. J., R. W. Doms, D. York, and J. White. 1986. Studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion: site-specific mutagenesis of the hemagglutinin of influenza virus. J. Cell Biol. 102:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stegmann, T., J. M. Delfino, F. M. Richards, and A. Helenius. 1991. The HA2 subunit of influenza hemagglutinin inserts into the target membrane prior to fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 266:18404–18410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsurudome, M., R. Gluck, R. Graf, R. Falchetto, U. Schaller, and J. Brunner. 1992. Lipid interactions of the hemagglutinin HA2 NH2-terminal segment during influenza virus-induced membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 267:20225–20232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wharton, S. A., S. R. Martin, R. W. Ruigrok, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1988. Membrane fusion by peptide analogues of influenza virus haemagglutinin. J. Gen. Virol. 69:1847–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lear, J. D., and W. F. DeGrado. 1987. Membrane binding and conformational properties of peptides representing the NH2 terminus of influenza HA-2. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6500–6505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murata, M., Y. Sugahara, S. Takahashi, and S. Ohnishi. 1987. pH-dependent membrane fusion activity of a synthetic twenty amino acid peptide with the same sequence as that of the hydrophobic segment of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 102:957–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kliger, Y., A. Aharoni, D. Rapaport, P. Jones, R. Blumenthal, and Y. Shai. 1997. Fusion peptides derived from the HIV type 1 glycoprotein 41 associate within phospholipid membranes and inhibit cell-cell fusion. Structure- function study. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13496–13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin, I., F. Defrise-Quertain, E. Decroly, M. Vandenbranden, R. Brasseur, and J. M. Ruysschaert. 1993. Orientation and structure of the NH2-terminal HIV-1 gp41 peptide in fused and aggregated liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1145:124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira, F. B., F. M. Goni, A. Muga, and J. L. Nieva. 1997. Permeabilization and fusion of uncharged lipid vesicles induced by the HIV-1 fusion peptide adopting an extended conformation: dose and sequence effects. Biophys. J. 73:1977–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haque, M. E., A. J. McCoy, J. Glenn, J. Lee, and B. R. Lentz. 2001. Effects of hemagglutinin fusion peptide on poly(ethylene glycol)-mediated fusion of phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochemistry. 40:14243–14251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haque, M. E., and B. R. Lentz. 2002. Influence of gp41 fusion peptide on the kinetics of poly(ethylene glycol)-mediated model membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 41:10866–10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieva, J. L., S. Nir, A. Muga, F. M. Goni, and J. Wilschut. 1994. Interaction of the HIV-1 fusion peptide with phospholipid vesicles: different structural requirements for fusion and leakage. Biochemistry. 33:3201–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray, C., S. A. Tatulian, S. A. Wharton, and L. K. Tamm. 1996. Effect of the N-terminal glycine on the secondary structure, orientation, and interaction of the influenza hemagglutinin fusion peptide with lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 70:2275–2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto, T. 1999. Membrane destabilizing activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin-based synthetic peptide: implications of critical glycine residue in fusion peptide. Biophys. Chem. 79:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pecheur, E. I., I. Martin, A. Bienvenue, J. M. Ruysschaert, and D. Hoekstra. 2000. Protein-induced fusion can be modulated by target membrane lipids through a structural switch at the level of the fusion peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3936–3942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtain, C., F. Separovic, K. Nielsen, D. Craik, Y. Zhong, and A. Kirkpatrick. 1999. The interactions of the N-terminal fusogenic peptide of HIV-1 gp41 with neutral phospholipids. Eur. Biophys. J. 28:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epand, R. M., and R. F. Epand. 1994. Relationship between the infectivity of influenza virus and the ability of its fusion peptide to perturb bilayers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202:1420–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen, P. S., Jr., T. Y. Toribara, and H. Warner. 1956. Microdetermination of phosphorus. Anal. Chem. 28:1756–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwenk, E., and N. T. Werthessen. 1952. Studies on the biosynthesis of cholesterol. III. Purification of C(14)-cholesterol from perfusions of livers and other organs. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 40:334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lentz, B. R., T. J. Carpenter, and D. R. Alford. 1987. Spontaneous fusion of phosphatidylcholine small unilamellar vesicles in the fluid phase. Biochemistry. 26:5389–5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hope, M. J., M. B. Bally, G. Webb, and P. R. Cullis. 1985. Production of large unilamellar vesicles by a rapid extrusion procedure: characterization of size distribution, trapped volume and ability to maintain a membrane potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 812:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lentz, B. R., G. F. McIntyre, D. J. Parks, J. C. Yates, and D. Massenburg. 1992. Bilayer curvature and certain amphipaths promote poly(ethylene glycol)-induced fusion of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 31:2643–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, J., and B. R. Lentz. 1997. Outer leaflet-packing defects promote poly(ethylene glycol)-mediated fusion of large unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 36:421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chattopadhyay, A., and E. London. 1987. Parallax method for direct measurement of membrane penetration depth utilizing fluorescence quenching by spin-labeled phospholipids. Biochemistry. 26:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis, B. A., and D. M. Engelman. 1983. Lipid bilayer thickness varies linearly with acyl chain length in fluid phosphatidylcholine vesicles. J. Mol. Biol. 166:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntosh, T. J., and P. W. Holloway. 1987. Determination of the depth of bromine atoms in bilayers formed from bromolipid probes. Biochemistry. 26:1783–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sreerama, N., and R. W. Woody. 2000. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 287:252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silvestro, L., and P. H. Axelsen. 1998. Infrared spectroscopy of supported lipid monolayer, bilayer, and multibilayer membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 96:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Axelsen, P. H., W. D. Braddock, H. L. Brockman, C. M. Jones, R. A. Dluhy, B. K. Kaufman, and F. J. Puga II. 1995. Use of internal reflectance infrared spectroscopy for the in-situ study of supported lipid monolayers. Appl. Spectrosc. 49:526–531. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silvestro, L., and P. H. Axelsen. 1999. Fourier transform infrared linked analysis of conformational changes in annexin V upon membrane binding. Biochemistry. 38:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Axelsen, P. H., and M. J. Citra. 1996. Orientational order determination by internal reflection infrared spectroscopy. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 66:227–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silvestro, L., and P. H. Axelsen. 2000. Membrane-induced folding of cecropin A. Biophys. J. 79:1465–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slater, S. J., M. B. Kelly, F. J. Taddeo, C. Ho, E. Rubin, and C. D. Stubbs. 1994. The modulation of protein kinase C activity by membrane lipid bilayer structure. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rafalski, M., A. Ortiz, A. Rockwell, L. C. van Ginkel, J. D. Lear, W. F. DeGrado, and J. Wilschut. 1991. Membrane fusion activity of the influenza virus hemagglutinin: interaction of HA2 N-terminal peptides with phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 30:10211–10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pecheur, E. I., J. Sainte-Marie, A. Bienvenüe, and D. Hoekstra. 1999. Peptides and membrane fusion: towards an understanding of the molecular mechanism of protein-induced fusion. J. Membr. Biol. 167:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koppaka, V., and B. R. Lentz. 1996. Binding of bovine factor Va to phosphatidylcholine membranes. Biophys. J. 70:2930–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lentz, B. R. 1993. Use of fluorescent probes to monitor molecular order and motions within liposome bilayers. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 64:99–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stubbs, C. D., C. Ho, and S. J. Slater. 1995. Fluorescence techniques for probing water penetration into lipid bilayers. J. Fluo. 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Clague, M. J., J. R. Knutson, R. Blumenthal, and A. Herrmann. 1991. Interaction of influenza hemagglutinin amino-terminal peptide with phospholipid vesicles: a fluorescence study. Biochemistry. 30:5491–5497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhelev, D. V., N. Stoicheva, P. Scherrer, and D. Needham. 2001. Interaction of synthetic HA2 influenza fusion peptide analog with model membranes. Biophys. J. 81:285–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luneberg, J., I. Martin, F. Nussler, J. M. Ruysschaert, and A. Herrmann. 1995. Structure and topology of the influenza virus fusion peptide in lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27606–27614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burger, K. N., S. A. Wharton, R. A. Demel, and A. J. Verkleij. 1991. The interaction of synthetic analogs of the N-terminal fusion sequence of influenza virus with a lipid monolayer. Comparison of fusion-active and fusion-defective analogs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1065:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi, S. 1990. Conformation of membrane fusion-active 20-residue peptides with or without lipid bilayers. Implication of alpha-helix formation for membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 29:6257–6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murata, M., S. Takahashi, S. Kagiwada, A. Suzuki, and S. Ohnishi. 1992. pH-dependent membrane fusion and vesiculation of phospholipid large unilamellar vesicles induced by amphiphilic anionic and cationic peptides. Biochemistry. 31:1986–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishiguro, R., N. Kimura, and S. Takahashi. 1993. Orientation of fusion-active synthetic peptides in phospholipid bilayers: determination by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 32:9792–9797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ishiguro, R., M. Matsumoto, and S. Takahashi. 1996. Interaction of fusogenic synthetic peptide with phospholipid bilayers: orientation of the peptide alpha-helix and binding isotherm. Biochemistry. 35:4976–4983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luneberg, J., I. Martin, F. Nussler, J. M. Ruysschaert, and A. Herrmann. 1995. Structure and topology of the influenza virus fusion peptide in lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27606–27614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rafalski, M., J. D. Lear, and W. F. DeGrado. 1990. Phospholipid interactions of synthetic peptides representing the N- terminus of HIV gp41. Biochemistry. 29:7917–7922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang, D. K., S. F. Cheng, and W. J. Chien. 1997. The amino-terminal fusion domain peptide of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gp41 inserts into the sodium dodecyl sulfate micelle primarily as helix with a conserved glycine at the micelle-water interface. J. Virol. 71:6593–6602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bodner, M. L., C. M. Gabrys, P. D. Parkanzky, J. Yang, C. A. Duskin, and D. P. Weliky. 2004. Temperature dependence and resonance assignment of 13C NMR spectra of selectively and uniformly labeled fusion peptides associated with membranes. Magn. Reson. Chem. 42:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krimm, S., and J. Bandekar. 1986. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 38:181–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wimley, W. C., K. Hristova, A. S. Ladokhin, L. Silvestro, P. H. Axelsen, and S. H. White. 1998. Folding of beta-sheet membrane proteins: a hydrophobic hexapeptide model. J. Mol. Biol. 277:1091–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slepushkin, V. A., S. M. Andreev, M. V. Sidorova, G. B. Melikyan, V. B. Grigoriev, V. M. Chumakov, A. E. Grinfeldt, R. A. Manukyan, and E. V. Karamov. 1992. Investigation of human immunodeficiency virus fusion peptides. Analysis of interrelations between their structure and function. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 8:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Terletskaya, Y. T., I. O. Trikash, E. S. Serdyuk, and S. M. Andreev. 1995. Fusion of negatively charged liposomes induced by peptides of the N-terminal fragment of HIV-1 transmembrane protein. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 60:1309–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gordon, L. M., C. C. Curtain, Y. C. Zhong, A. Kirkpatrick, P. W. Mobley, and A. J. Waring. 1992. The amino-terminal peptide of HIV-1 glycoprotein 41 interacts with human erythrocyte membranes: peptide conformation, orientation and aggregation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1139:257–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martin, I., H. Schaal, A. Scheid, and J. M. Ruysschaert. 1996. Lipid membrane fusion induced by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 N-terminal extremity is determined by its orientation in the lipid bilayer. J. Virol. 70:298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang, J., C. M. Gabrys, and D. P. Weliky. 2001. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for an extended beta strand conformation of the membrane-bound HIV-1 fusion peptide. Biochemistry. 40:8126–8137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koppaka, V., L. Silvestro, J. A. Engler, C. G. Brouillette, and P. H. Axelsen. 1999. The structure of human lipoprotein A-I. Evidence for the “belt” model. J. Biol. Chem. 274:14541–14544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Han, X., J. H. Bushweller, D. S. Cafiso, and L. K. Tamm. 2001. Membrane structure and fusion-triggering conformational change of the fusion domain from influenza hemagglutinin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vaccaro, L., K. J. Cross, J. Kleinjung, S. K. Straus, D. J. Thomas, S. A. Wharton, J. J. Skehel, and F. Fraternali. 2005. Plasticity of influenza haemagglutinin fusion peptides and their interaction with lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 88:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang, J., and D. P. Weliky. 2003. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for parallel and antiparallel strand arrangements in the membrane-associated HIV-1 fusion peptide. Biochemistry. 42:11879–11890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clodi, K., K. O. Kliche, S. Zhao, D. Weidner, T. Schenk, U. Consoli, S. Jiang, V. Snell, and M. Andreeff. 2000. Cell-surface exposure of phosphatidylserine correlates with the stage of fludarabine-induced apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and expression of apoptosis-regulating genes. Cytometry. 40:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mourdjeva, M., D. Kyurkchiev, A. Mandinova, I. Altankova, I. Kehayov, S. Kyurkchiev, K. Clodi, K. O. Kliche, S. Zhao, D. Weidner, T. Schenk, U. Consoli, et al. 2005. Dynamics of membrane translocation of phosphatidylserine during apoptosis detected by a monoclonal antibody. Cell-surface exposure of phosphatidylserine correlates with the stage of fludarabine-induced apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and expression of apoptosis-regulating genes. Apoptosis. 10:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Colotto, A., I. Martin, J. M. Ruysschaert, A. Sen, S. W. Hui, and R. M. Epand. 1996. Structural study of the interaction between the SIV fusion peptide and model membranes. Biochemistry. 35:980–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen, Z., and R. P. Rand. 1998. Comparative study of the effects of several n-alkanes on phospholipid hexagonal phases. Biophys. J. 74:944–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Malinin, V. S., P. Frederik, and B. R. Lentz. 2002. Osmotic and curvature stress affect PEG-induced fusion of lipid vesicles but not mixing of their lipids. Biophys. J. 82:2090–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malinin, V., and B. R. Lentz. 2004. Energetics of vesicle fusion intermediates: comparison of calculations with observed effects of osmotic and curvature stresses. Biophys. J. 86:2951–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.