Abstract

The geometries of the transition states, intermediates, and prereactive enzyme-substrate complex and the corresponding energy barriers have been determined by performing hybrid quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) calculations on butyrylcholinesterase (BChE)-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)- and (+)-cocaine. The energy barriers were evaluated by performing QM/MM calculations with the QM method at the MP2/6-31+G* level and the MM method using the AMBER force field. These calculations allow us to account for the protein environmental effects on the transition states and energy barriers of these enzymatic reactions, showing remarkable effects of the protein environment on intermolecular hydrogen bonding (with an oxyanion hole), which is crucial for the transition state stabilization and, therefore, on the energy barriers. The calculated energy barriers are consistent with available experimental kinetic data. The highest barrier calculated for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)- and (+)-cocaine is associated with the third reaction step, but the energy barrier calculated for the first step is close to the highest and is so sensitive to the protein environment that the first reaction step can be rate determining for (−)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by a BChE mutant. The computational results provide valuable insights into future design of BChE mutants with a higher catalytic activity for (−)-cocaine.

INTRODUCTION

Cocaine abuse and dependence pose a major medical, social, and economic problem that continues to defy treatment (1–4). The disastrous medical and social consequences of cocaine addiction, such as violent crime, loss in individual productivity, illness, and death, have made the development of an effective pharmacological treatment a high priority (5,6). However, cocaine mediates its reinforcing and toxic effects by blocking neurotransmitter reuptake, and the classical pharmacodynamic approach has failed to yield small-molecule receptor antagonists due to the difficulties inherent in blocking a blocker (1–6). An alternative to receptor-based approaches is to interfere with the delivery of cocaine to its receptors and accelerate its metabolism in the body (6). An ideal molecule for this purpose should be a potent enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of cocaine into biologically inactive metabolites.

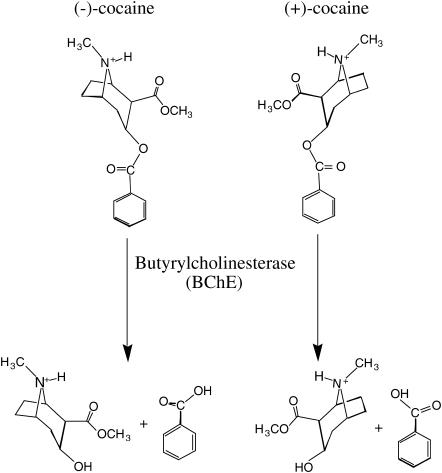

The dominant pathway for cocaine metabolism in primates is butyrylcholinesterase (BChE)-catalyzed hydrolysis at the benzoyl ester group (Fig. 1) and the metabolites are all biologically inactive (6,7). Only 5% of the cocaine is deactivated through oxidation by the liver microsomal cytochrome P450 system (8), and the oxidation produces norcocaine, which is hepatotoxic and a local anesthetic (9). Clearly, BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of cocaine at the benzoyl ester is the metabolic pathway most suitable for amplification, and enhancement of cocaine metabolism by administration of BChE has been recognized as a promising pharmacokinetic approach for treatment of cocaine abuse and dependence (6). However, the catalytic activity of this plasma enzyme is remarkably lower against the naturally occurring (−)-cocaine than that against the biologically inactive (+)-cocaine enantiomer (Fig. 1). Whereas (+)-cocaine can be cleared from plasma in seconds and before partitioning into the central nervous system, (−)-cocaine has a plasma half-life of ∼45−90 min, long enough for manifestation of the central nervous system effects, which peak in minutes (10,11). Hence, a BChE mutant with higher activity against (−)-cocaine are highly desirable for use as an exogenous enzyme in human.

FIGURE 1.

BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)- and (+)-cocaine.

For the purpose of rational design of high-activity mutants of BChE against (−)-cocaine, we first need to understand the detailed reaction mechanism concerning how cocaine is hydrolyzed in human BChE. Previous computational studies (12–23) revealed how cocaine binds with BChE, although only one (22) of the computational studies reported so far dealt with the reaction pathway for BChE-catalyzed cocaine hydrolysis. The molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the prereactive BChE-cocaine binding and ab initio reaction coordinate calculations with an active site model (22) demonstrated that, for both (−)- and (+)-cocaine, the fundamental reaction pathway for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of cocaine consists of acylation and deacylation stages. A total of four individual reaction steps are involved in the acylation and deacylation stages, which is similar to the mechanism for ester hydrolysis catalyzed by other serine hydrolases, and the calculated highest free energy barrier is associated with the third reaction step (22). Based on the computational modeling (22), amino acid residues S198, H438, and E325 clearly form a catalytic triad which is similar to that found for acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-catalyzed hydrolysis of neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) (24,25).

The key to the rational design of high-activity mutants of BChE against (−)-cocaine is to further understand the protein environmental effects on the reaction pathway, particularly the transition states involved and the corresponding energy barriers. This is because, to increase the catalytic activity of BChE for (−)-cocaine, we need to design necessary mutation(s) to modify the protein environment such that the modified protein environment can more favorably stabilize the transition states and, therefore, lower the energy barriers, particularly for the rate-determining step(s). Understanding the protein environmental effects on the reaction pathway and energy barriers should help to rationally design BChE mutants with a lower energy barrier and, therefore, a higher catalytic activity for (−)-cocaine. However, previous ab initio reaction coordinate calculations (22) with an active site model can only account for breaking and formation of covalent bonds during the catalytic reaction process; the more complicated protein environmental effects on the reaction pathway and energy barriers have not been examined yet. In this study, extensive hybrid quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) calculations were performed on the entire BChE-(−)-cocaine and BChE-(+)-cocaine systems to optimize the geometries of the transition states and the corresponding prereactive enzyme-substrate complexes and intermediates involved in the BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)- and (+)-cocaine and to predict the corresponding energy barriers. The calculated results reveal remarkable effects of the protein environment on the energy barriers and provide useful insights into future rational design of BChE mutants with lower energy barriers for the catalytic hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

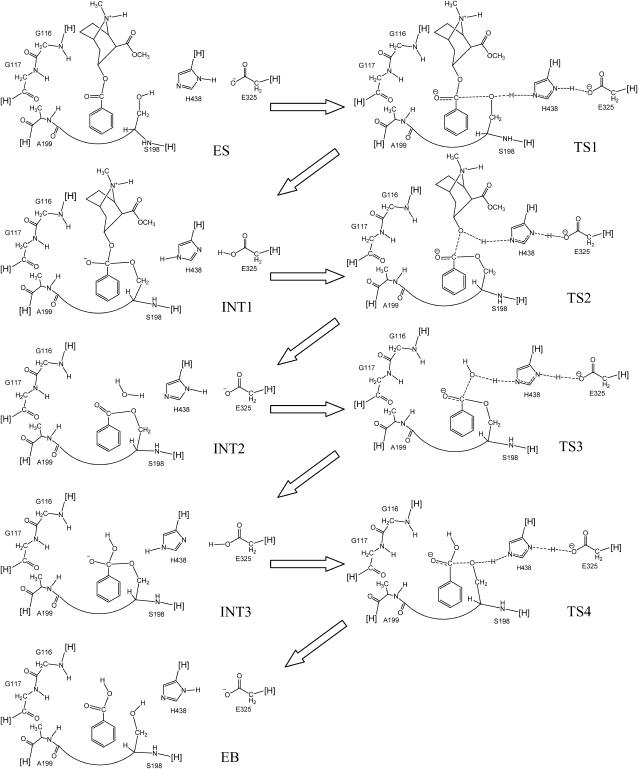

The initial geometries used for the geometry optimizations with the QM/MM approach were prepared based on MD simulations on the entire BChE-(−)-cocaine and BChE-(+)-cocaine systems in water by using the AMBER7 program package (26). As known in the previous reaction coordinate calculations on (−)-cocaine with a simplified active site model of BChE (22), the reaction coordinate is characterized by gradually breaking and forming some covalent bonds during the reaction process, as seen in Fig. 2. The MD simulations on the transition states were performed in such a way that bond lengths of the partially formed and partially broken covalent bonds in the transition states were all constrained to be the same as those obtained from our previous ab initio reaction coordinate calculations on the model reaction system (22). A sufficiently long MD simulation in this way should lead to a reasonable protein environment stabilizing the reaction center in the transition state structure simulated.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the pathway for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine; the pathway for (+)-cocaine is the same in terms of the covalent bond formation and breaking, as the only difference between (−)-cocaine and (+)-cocaine is the position of the methyl ester group. Only the QM-treated high-layer part of the reaction system in the ONIOM (QM/MM) calculations are drawn. Notation [H] refers to a nonhydrogen atom in the MM-treated low-layer part of the protein, and the cut covalent bond with this atom is saturated by a hydrogen atom. The dashed lines in the transition state structures represent the covalent bonds that form or break during the reaction steps.

Our previous MD simulations (23) on the prereactive BChE-cocaine binding started from the x-ray crystal structure (27) deposited in the Protein Data Bank (pdb code: 1POP) (28,29). Starting from the simulated prereactive BChE-cocaine complexes and the geometries obtained from the previous ab initio reaction coordinate calculations (22) on (−)-cocaine with a simplified model of the BChE active site, we were able to construct starting structures of the transition states for performing MD simulations on these transition-state structures with the entire BChE structure in water. To construct each of these starting structures used for MD simulations, the active site atoms in the optimized geometry obtained from the ab initio reaction coordinate calculations were superimposed with the corresponding atoms in the simulated prereactive BChE-cocaine complex. Thus, in these starting structures used for MD simulations, the geometric parameters (i.e., the lengths of covalent bonds that form or break during the reaction) within the reaction center are the same as those obtained from our previous ab initio reaction coordinate calculations on the model reaction system (22). The difference is that the initial geometries constructed in this study include the entire protein environment. So, the interaction of the reaction center with its protein environment can be examined through computational studies on the entire reaction system.

The partial atomic charges for the nonstandard residue atoms, including cocaine atoms, were calculated by using the RESP protocol implemented in the Antechamber module of the AMBER7 package following electrostatic potential (ESP) calculations at ab initio HF/6-31G* level. The geometries used in the ESP calculations came from those obtained from the previous ab initio reaction coordinate calculations (22), but the functional groups representing the oxyanion hole were removed. Thus, residues G116, G117, and A199 were the standard residues in the MD simulations. The general procedure for carrying out the MD simulations in water is essentially the same as that used in our previously reported other computational studies (22,23,30–32). Each aforementioned starting structure during the reaction process was neutralized by adding chloride counterions and was solvated in a rectangular box of TIP3P water molecules (33) with a minimum solute-wall distance of 10 Å. The total numbers of atoms in the solvated protein structures for the MD simulations are nearly 70,000, although the total number of atoms of BChE and cocaine is only 8417. All of the MD simulations were performed by using the Sander module of the AMBER7 package. The solvated systems were carefully equilibrated and fully energy minimized. These systems were gradually heated from T = 10 K to T = 298.15 K in 30 ps before production MD simulation of 1 ns or longer, making sure that we obtained a stable MD trajectory for each of the simulated structures. The time step used for the MD simulations was 2 fs. Periodic boundary conditions in the constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature ensemble at T = 298.15 K with Berendsen temperature coupling (34) and P = 1 atm with isotropic molecule-based scaling (34) were applied. The SHAKE algorithm (35) was used to fix all covalent bonds containing hydrogen atoms. The nonbonded pair list was updated every 10 steps. The particle mesh Ewald method (36) was used to treat long-range electrostatic interactions. A residue-based cutoff of 10 Å was utilized for the noncovalent interactions. The coordinates of the simulated systems were collected every 1 ps during the production MD stages.

For each transition state structure examined, after the MD simulation was completed and a stable MD trajectory was obtained, all of the collected snapshots of the simulated structure, excluding those before the trajectory was stabilized, were averaged. The average structure was energy minimized again. The energy minimized average coordinates of each simulated transition state structure were used as an initial geometry to carry out further transition state geometry optimization by using the ONIOM approach (37) implemented in the Gaussian03 program (38). Two layers were defined in our ONIOM calculations: the high layer (depicted in Fig. 2) was calculated quantum mechanically at the ab initio HF/3-21G level, and the low layer was calculated molecular mechanically by using the AMBER force field as used in our MD simulations and energy minimizations with the AMBER7 program. The ONIOM calculations at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level in this study are a type of QM/MM calculation (39,40). As depicted in Fig. 2, for all of these QM/MM calculations, the same part of the protein was included in the QM-treated high layer; the total number of the QM-treated atoms is 99 for each QM/MM calculation on the acylation stage. So, the QM-treated high layer included the three residues (G116, G117, and A199) of the possible oxyanion hole, key functional groups from the catalytic triad (S198, H438, and E325), and cocaine, whereas the entire protein structure of BChE was included in the MM-treated low layer (8417 atoms). In addition, a water molecule was also included in the QM-treated high layer for the calculations on the structures involved in the deacylation stage of the reaction. We developed a C program to automatically generate the input files for the ONIOM calculations following the MD simulations and subsequent energy minimizations to make sure that the atom types used for all low-layer atoms are the same as what we used in the AMBER7.

The goal of the ONIOM-based QM/MM calculations for each transition state was to find the desired transition state geometry associated with a first-order saddle point on the potential energy surface (PES). Although this enzymatic reaction system is too large to calculate the QM/MM force constant matrix required in the automated search for a first-order saddle point on the PES, we were able to perform a series of partial geometry optimizations with a key C–O bond length (which is the primary component of the reaction coordinate for the specific step of the reaction) (22) fixed at different values. The C atom in such a key C–O bond is always the carbonyl carbon of cocaine benzoyl ester. The O atom in such a key C–O bond is the Oγ atom of S198 in TS1 and TS4, the ester oxygen of cocaine benzoyl ester in TS2, or the O atom of a water molecule in TS3. So, we determined a simplified one-dimensional PES and obtained the length of the key C–O bond associated with a saddle point on the PES for each transition state. Such a saddle point on the simplified one-dimensional PES is also a first-order saddle point on the multiple-dimensional PES, since the selected key C–O bond length dominates the reaction coordinate according to our previous reaction coordinate calculations with an active site model (22). Thus, we determined the geometries of transition states TS1–TS4. Starting from the geometry optimized for each transition state, we were able to further optimize geometry of the corresponding prereactive enzyme-substrate (ES) complex (for TS1) or intermediate (INT1 for TS2 or INT2 for TS3 or INT3 for TS4) associated with a local minimum connecting with the first-order saddle point on the PES.

The geometries optimized at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level for the transition states, intermediates, and prereactive BChE-cocaine complexes were used to perform single-point energy calculations at the MP2/6-31+G*:AMBER level for evaluating the energy barriers. In these QM/MM calculations, the total number of contacted basis functions used for the MP2 calculations on the high-layer atoms is as large as 1048. To examine whether the HF/3-21G level for the high layer is adequate or not for the geometry optimization, the geometries of TS3 and INT2 optimized at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level were further refined at the more sophisticated B3LYP/6-31+G*:AMBER level, followed by the single-point energy calculations at the MP2/6-31+G*:AMBER level.

Most of the QM/MM calculations were performed in parallel on an HP supercomputer (Superdome, with 256 shared-memory processors) at the Center for Computational Sciences, University of Kentucky. Some computations were carried out on a 34-processors IBM ×335 Linux cluster and SGI Fuel workstations in our own lab.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Geometries

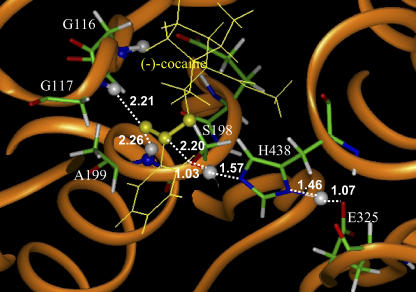

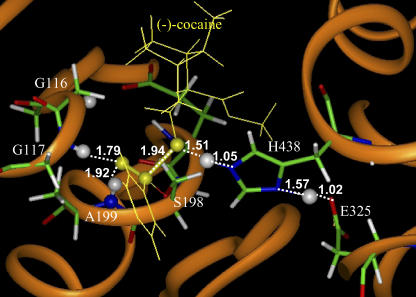

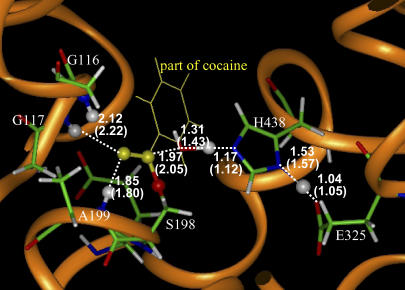

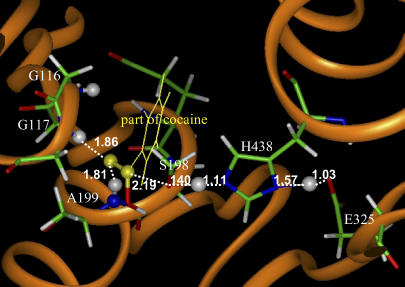

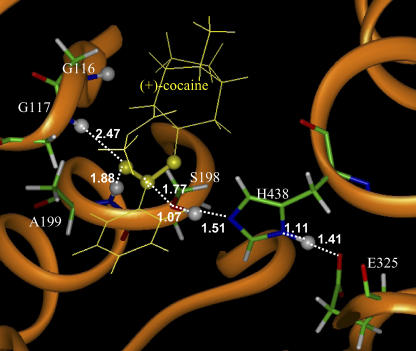

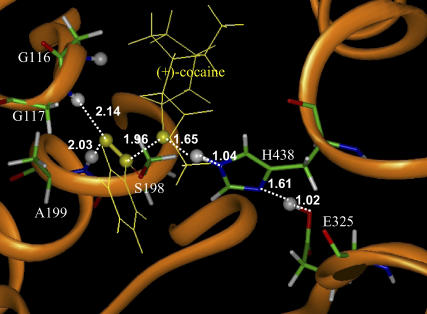

By performing the geometry optimizations using the QM/MM methods as described above, we obtained the converged geometries of the transition states (TS1, TS2, TS3, and TS4) and the corresponding prereactive BChE-cocaine complex (ES) and intermediates (INT1, INT2, and INT3) for the hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine catalyzed by human BChE. The geometries of transition states TS1–TS4 optimized at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level are depicted in Figs. 3–8, respectively, where key internuclear distances optimized are indicated. We note that the BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine share the same TS3 and TS4 structures. Indicated in the figures are the optimized lengths of the covalent bonds that are forming or breaking during the individual reaction step associated with the transition state, along with the H…O distances involved in the N-H…O hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen of cocaine benzoyl ester and backbones of G117 and A199. For comparison, we also indicated in Fig. 5 the corresponding internuclear distances optimized at the B3LYP/6-31+G*:AMBER level for TS3. As seen in Fig. 5, the internuclear distances optimized at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level are all reasonably close to the corresponding distances optimized at the B3LYP/6-31+G*:AMBER level. The most important internuclear distance in TS3 is the forming C–O bond between the carbonyl carbon atom of cocaine and the oxygen atom of a water molecule. This C–O distance was optimized to be 1.97 Å at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level and 2.05 Å at the B3LYP/6-31+G*:AMBER level. The C–O distance optimized at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level is only 0.08 Å longer than that optimized at the B3LYP/6-31+G*:AMBER level. The largest difference, 0.12 Å, in internuclear distance between the geometries optimized at the two levels is associated with the length (1.31 Å versus 1.43 Å) of the breaking O–H bond in a water molecule. These geometric parameters suggest that the QM/MM calculations at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level are reliable for the optimization of the transition state geometries involved in this enzymatic reaction system.

FIGURE 3.

Part of the QM/MM-optimized geometry of the transition state for the first step (TS1) of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the wild-type BChE. The atoms highlighted as balls include several key H atoms (gray balls) and the C and O atoms in the carboxylate group of cocaine (yellow balls).

FIGURE 4.

Part of the QM/MM-optimized geometry of the transition state for the second step (TS2) of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the wild-type BChE. The atoms highlighted as balls include several key H atoms (gray balls) and the C and O atoms in the carboxylate group of cocaine (yellow balls).

FIGURE 5.

Part of the QM/MM-optimized geometry of the transition state for the third step (TS3) of (−)/(+)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the wild-type BChE. The atoms highlighted as balls include several key H atoms (gray balls) and the C and O atoms in the carbonyl group of cocaine (yellow balls).

FIGURE 6.

Part of the QM/MM-optimized geometry of the transition state for the fourth step (TS4) of (−)/(+)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the wild-type BChE. The atoms highlighted as balls include several key H atoms (gray balls) and the C and O atoms in the carbonyl group of cocaine (yellow balls).

FIGURE 7.

Part of the QM/MM-optimized geometry of the transition state for the first step (TS1) of (+)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the wild-type BChE. The atoms highlighted as balls include several key H atoms (gray balls) and the C and O atoms in the carboxylate group of cocaine (yellow balls).

FIGURE 8.

Part of the QM/MM-optimized geometry of the transition state for the second step (TS2) of (+)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the wild-type BChE. The atoms highlighted as balls include several key H atoms (gray balls) and the C and O atoms in the carboxylate group of cocaine (yellow balls).

In addition, we also tested another partial geometry optimization on the TS3 structure for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of cocaine starting from the final snapshot of the MD-simulated TS3 structure. In the partial geometry optimization, the forming C–O bond between the carbonyl carbon atom of cocaine and the oxygen atom of the water molecule in the TS3 structure was fixed at the value used in the MD simulation. The optimized geometric parameters for the high layer atoms are essentially the same as the corresponding geometric parameters (shown in Fig. 5) optimized starting from the average structure of the MD-simulated TS3 structure. This suggests that it would not matter whether the average structure or the final snapshot of the MD-simulated structure was used as the initial guess of the QM/MM geometry optimization for a transition state.

The QM/MM-optimized geometries of the transition states, intermediates, and prereactive BChE-cocaine complex and their connections on the PES are consistent with the assumed enzymatic reaction pathway involving four reaction steps depicted in Fig. 2. For example, in the first step associated with TS1, the hydroxyl oxygen of S198 gradually attacks the carbonyl carbon of cocaine benzoyl ester, while the proton of the hydroxyl group gradually transfers to a nitrogen atom of an H438 side chain, and the H438 side chain gradually transfers another proton to an oxygen atom of an E325 side chain. This reaction step and the third reaction step (associated with TS3) both belong to the standard general base-catalysis mechanism, whereas both the second and fourth steps (associated with TS2 and TS4) follow the standard specific acid-catalysis mechanism. The results obtained from the QM/MM calculations qualitatively confirm the fundamental reaction pathway proposed for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of cocaine based on the previous reaction coordinate calculations with a simplified active site model (22). It follows that the protein environment neglected in the previous reaction coordinate calculations (22) do not change the fundamental reaction pathway for this enzymatic reaction, as far as the breaking and formation of covalent bonds are concerned.

However, the protein environment significantly affects the hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl oxygen of cocaine and the oxyanion hole (G116, G117, and A199) during the enzymatic reaction process. This type of hydrogen bonding with the oxyanion hole is crucial for the transition state stabilization, particularly for the first and third reaction steps because the carbonyl oxygen atom in TS1 and TS3 possesses more negative charge than that in ES and INT2. As seen in Figs. 3–8, the peptidic NH groups of G117 and A199 form N-H…O hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen of cocaine benzoyl ester, but the peptidic NH group of G116 cannot form an N-H…O hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen of cocaine benzoyl ester. The role of the oxyanion hole in BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine is remarkably different from the known role of a similar oxyanion hole in AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh (24) in terms of the number of N-H…O hydrogen bonds, although the oxyanion hole always stabilizes the transition states. AChE and BChE have very similar active sites, including the same type of catalytic triad and the same type of oxyanion hole. In terms of mouse AChE, the catalytic triad consists of S203, H447, and E334 and the oxyanion hole consists of G121, G122, and A204. The only significant difference is that the cavity of the BChE active site is larger so that it can accommodate a larger substrate like cocaine. McCammon et al. (24,41,42) reported QM/MM calculations on the initial step of AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh; the computational strategy (including the determination of a one-dimensional PES using the C–O bond length as the variable) used in their QM/MM calculations on AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh is similar to that used in our QM/MM calculations on BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine. Their QM/MM results clearly indicate that three hydrogen bonds exist between the carbonyl oxygen of ACh and the peptidic NH groups of G121, G122, and A204 in the transition state (24).

Energy barriers

Summarized in Table 1 are the energy barriers predicted for (−)- and (+)-cocaine hydrolysis by performing the QM/MM calculations at the MP2/6-31+G*:AMBER level for all of the reaction steps, along with the corresponding energy barriers calculated previously for the (−)-cocaine hydrolysis with a simplified active site model of BChE (neglecting the protein environment) for comparison. A comparison between the two sets of energy barriers listed in Table 1 reveals that the protein environmental effects dramatically change the energy barrier calculated for the first reaction step of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis. The energy barriers calculated for the other steps are relatively less sensitive to the inclusion of the protein environment. The protein environmental effects increase the energy barrier for the first step of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis by ∼9 kcal/mol, decrease the energy barriers for the second and third steps by ∼2–3 kcal/mol, and slightly increase the energy barrier for the fourth step. As a result, the second reaction step becomes almost barrierless and the energy barrier calculated for the fourth step is still much lower than that calculated for the third step. Based on the QM/MM results listed in Table 1, the third reaction step has the highest energy barrier, 14.2 kcal/mol; the energy barrier of 13.0 kcal/mol calculated for the first step of the (−)-cocaine hydrolysis is close to the barrier calculated for the third step. The energy barrier of 12.1 kcal/mol calculated for the first step of the (+)-cocaine hydrolysis is slightly lower than that of the first step of the (−)-cocaine hydrolysis.

TABLE 1.

Energy barriers (ΔEa) calculated for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)- and (+)-cocaine

| ΔEa (kcal/mol)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method and substrate | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

| Neglecting protein environment* | (−)-cocaine | 4.0 | 3.1 | 16.6 (17.0) | 6.5 |

| Including protein environment†

|

(−)-cocaine | 13.0 | 0.1 | 14.2 | 7.2 |

| (+)-cocaine | 12.1 | 0.4 | 14.2 | 7.2 | |

Calculated for a simplified model system (22) at the MP2/6-31+G*//HF/3-21G level. The value in parentheses was calculated at the MP2/6-31+G*//B3LYP/6-31G* level.

Calculated for the real enzymatic reaction system by using the QM/MM method at the MP2/6-31+G*:AMBER level with the geometries optimized at the HF/3-21G:AMBER level.

We note that the third and fourth reaction steps of BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (+)-cocaine are the same as the third and fourth reaction steps of BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine. The highest energy barrier being associated with the third step means that (−)- and (+)-cocaine should be hydrolyzed by BChE at the same rate if the chemical reaction process is the rate-determining stage for both (−)- and (+)-cocaine. Further, if the chemical reaction process is the rate-determining stage, the catalytic rate constant kcat should be dependent on the pH of the reaction solution, because H438 in the catalytic triad can be protonated and lose its catalytic role at low pH. However, BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (+)-cocaine (kcat = 1.07 × 102 s-1 and KM = 8.5 μM) was observed to be three orders of magnitude faster than BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine (kcat = 6.5 × 10−2 s−1 and KM = 9.0 μM) (19) and only the kcat value for (+)-cocaine was pH dependent. So, the experimental data (19) clearly indicated that the rate-determining stage should be the chemical reaction process for (+)-cocaine, whereas the formation of the prereactive BChE-substrate (ES) binding complex should be the rate-determining stage for (−)-cocaine. Our calculated energy barriers further demonstrate that the third reaction step is the rate-determining step for (+)-cocaine.

The highest energy barrier calculated for BChE-catalyzed cocaine hydrolysis is ∼3.7 kcal/mol higher than that (10.5 kcal/mol) calculated at the similar level, i.e., MP2(6-31+G*) QM/MM, by McCammon et al. (24) for the first step of the AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh (the first step was recognized as the rate-determining step for the enzymatic reaction). The difference in the energy barrier between the two enzymatic reactions can be attributed to the aforementioned difference in the number of N-H…O hydrogen bonds of the substrate with the oxyanion hole of the enzyme during the reaction processes.

The difference between the QM/MM-calculated energy barriers for the rate-determining steps of the two enzymatic reaction systems is consistent with the experimental observation that the kcat value (1.6 × 104 s−1) (43) for AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh was ∼150-fold larger than that (kcat = 1.07 × 102 s−1) (19) for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (+)-cocaine. Based on the widely used classical transition-state theory (44), the experimental kcat difference of ∼150-fold suggests an energy barrier difference of ∼3.0 kcal/mol when T = 298.15 K, which is in good agreement with the calculated barrier difference of ∼3.7 kcal/mol.

Insights into rational design of BChE mutants

Generally speaking, for rational design of a mutant enzyme with a higher catalytic activity against a given substrate, one needs to design a mutation that can accelerate the rate-determining step of the catalytic reaction process, whereas the other steps are not significantly slowed down by the mutation. It has been known (19) that the formation of the prereactive BChE-(−)-cocaine complex (ES) is the rate-determining step of BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine. Hence, the reported rational design of BChE mutants have been focused on how to speed up the ES formation process; for example, the A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE has been found to have a ∼9.4-fold improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) against (−)-cocaine (20). However, it has not been clear whether the energy barrier for the first step of BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine is higher than that for the third step or not. If the energy barrier for the first step were significantly higher than that for the third step, it would mean that the catalytic activity of BChE against (−)-cocaine should still be significantly lower than that against (+)-cocaine even if the chemical reaction process became rate determining. In that case, the site-directed mutagenesis designed to only speed up the ES formation process can be expected to make a limited improvement of the catalytic activity against (−)-cocaine. If the energy barrier for the third reaction step were the highest within the chemical reaction process, the catalytic activity of BChE against (−)-cocaine would be the same as that against (+)-cocaine when the chemical reaction process became rate determining. The energy barriers determined by our QM/MM calculations on BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine further demonstrate that the third reaction step indeed has the highest energy barrier (14.2 kcal/mol) within the chemical reaction processes, but the energy barrier of 13.0 kcal/mol calculated for the first step of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis is close to that for the third step. Further, the energy barrier for the first step is rather sensitive to the change of the protein environment because the protein environmental effects dramatically increase the energy barrier calculated for the first step, although the energy barriers for the subsequent steps look less sensitive to the change of the protein environment. These computational results suggest that it would be possible to design a BChE mutant which has a catalytic activity against (−)-cocaine comparable to wild-type BChE against (+)-cocaine if the designed mutation could considerably speed up the ES formation process without significantly changing the energy barrier for any step of the chemical reaction process. However, a mutation designed to speed up the ES formation process could also change the energy barriers for the chemical reaction steps, especially for the first reaction step because the energy barrier calculated for this step is so sensitive to the protein environmental effects. So, future rational design of the high activity mutants of BChE against (−)-cocaine should also pay attention to whether the mutation could also increase or decrease the energy barrier(s) for the first and/or third step of the chemical reaction process.

These computational insights help us to understand available experimental data better. It has been found that the catalytic rate constant kcat of A328W/Y332A BChE is pH dependent for both (−)- and (+)-cocaine hydrolyses and that the A328W/Y332A mutation does not change the catalytic activity against (+)-cocaine (21). The experimental kinetic data show that the chemical reaction process becomes rate determining for both (−)- and (+)-cocaine hydrolyses catalyzed by the A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE, but the energy barriers for the rate-determining step of the two reactions must be different. Taking these experimental data and our QM/MM results into account together, it is very likely that the rate-determining step of (+)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE is still the third reaction step. However, the rate-determining step of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE becomes the first reaction step and has a significantly higher energy barrier than the third step. A closer look at the detailed TS1 structure optimized for hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine catalyzed by wild-type BChE reveals that the TS1 structure is likely stabilized by a cation-π interaction between the protonated tropane nitrogen of (−)-cocaine and the benzene ring of a Y332 side chain. The QM/MM-optimized distance between the protonated tropane nitrogen of (−)-cocaine and the center of the benzene ring of Y332 side chain was ∼4.9 Å. Such a cation-π interaction will disappear when Y332 changes to Ala. Hence, although the Y332A mutation can help to remove the hindrance for the ES formation, the Y332A mutation may also destabilize the TS1 structure for (−)-cocaine hydrolysis. The Y332A mutation having no significant effect on the third reaction step may be explained by the fact that the tropane group of (−)-cocaine has left the active site after the second reaction step, as seen in Fig. 2. Thus, there is no cation-π interaction in the TS3 structure whether Y332 changes to Ala or not. This mechanistic understanding suggests that starting from the A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE, the rational design of further mutation(s) to improve the catalytic activity against (−)-cocaine should primarily aim to decrease the energy barrier for the first reaction step without significantly affecting the ES formation and other chemical reaction steps.

In particular, it is possible to decrease the energy barrier for the first reaction step of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis by designing a mutation to enhance the overall hydrogen bonding of the (−)-cocaine carbonyl oxygen with the oxyanion hole of BChE in the transition state TS1. The overall hydrogen bonding with the oxyanion hole of BChE in the TS1 structure could be enhanced through one of two possible types of mutations. One possible type of mutations could be designed to change the environment of residue G116 so that the peptidic NH group of G116 becomes available to form a possible hydrogen bond with the (−)-cocaine carbonyl oxygen. The other possible type of mutation (e.g., A199S or A199C) could be designed to have a hydrophilic side chain on a residue within the oxyanion hole (G116, G117, and A199) such that the hydrophilic side chain forms another possible hydrogen bond with the (−)-cocaine carbonyl oxygen. To theoretically test this idea, we carried out MD simulations on the TS1 structures for the (−)-cocaine hydrolysis with two new mutants A199S/A328W and A199S/A328W/Y332A of BChE in water, as we did on the TS1 structures for (−)- and (+)-cocaine hydrolyses with wild-type BChE. The MD simulations clearly revealed that in addition to the two hydrogen bonds between the (−)-cocaine carbonyl oxygen and the peptidic NH groups of residues at positions No. 117 and No. 199, the new residue at position No. 199, i.e., S199, also forms a hydrogen bond with the (−)-cocaine carbonyl oxygen through the hydroxyl group of the S199 side chain in the simulated TS1 structures (see Fig. 9 for an example). These modeling studies suggest that the TS1 structure for BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine may be more stable when A199 is replaced by a serine and, therefore, the A199S mutation could lower the energy barrier for the first reaction step. Although extensive wet experimental tests on various mutants of BChE for examining these computational insights are currently under way at University of Kentucky, College of Pharmacy, completed experimental tests on the A199S/A328W mutant (Y. Pan, W. Yang, H. Cho, H.-H. Tai, and C.-G. Zhan, unpublished data) have already revealed that A199S/A328W BChE has a ∼(28 ± 3)-fold improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) against (−)-cocaine compared to the wild-type against (−)-cocaine. The encouraging experimental outcome supports the aforementioned computational insights.

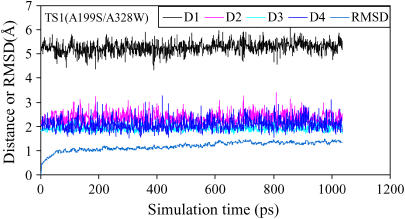

FIGURE 9.

Plots of the key internuclear distances (in angstroms) versus the time in the simulated TS1 structure for (−)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by A199S/A328W BChE. Traces D1, D2, and D3 refer to the distances between the carbonyl oxygen of (−)-cocaine and the NH hydrogen of G116, G117, and S199, respectively. Trace D4 is the internuclear distance between the carbonyl oxygen of (−)-cocaine and the hydroxyl hydrogen of the S199 side chain in A199S/A328W BChE. RMSD represents the root mean-square deviation (in angstroms) of the simulated positions of the protein backbone atoms from those in the initial structure.

CONCLUSION

The geometries of the transition states, intermediates, and prereactive enzyme-substrate complex (ES) involved in BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine and the corresponding energy barriers have been determined by performing hybrid QM/MM calculations on the entire enzymatic reaction systems. The extensive QM/MM calculations allow us to account for the protein environmental effects on the reaction pathway and the energy barriers of these enzymatic reactions for the first time. The QM/MM results reveal that the protein environmental effects significantly influence the crucial hydrogen bonding between the oxyanion hole (consisting of G116, G117, and A199) and the carbonyl oxygen of cocaine benzoyl ester, during the enzymatic reaction process. Due to the protein environmental effects, the role of the oxyanion hole in BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine is remarkably different from the known role of a similar oxyanion hole in AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh in terms of the number of N-H…O hydrogen bonds, although the oxyanion hole always stabilizes the transition states. Hence, the calculated highest energy barrier (14.2 kcal/mol) for the BChE-catalyzed hydrolyses of (−)- and (+)-cocaine is ∼3.7 kcal/mol higher than that (10.5 kcal/mol) for the AChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of ACh calculated previously at a similar QM/MM level of theory. The calculated barrier difference of ∼3.7 kcal/mol is consistent with the available experimental kinetic data suggesting an energy barrier difference of ∼3.0 kcal/mol.

The QM/MM results indicate that the highest energy barrier calculated for the BChE-catalyzed hydrolysis of (−)-cocaine is associated with the third reaction step, but the energy barrier (13.0 kcal/mol) calculated for the first reaction step is close to that for the third step (14.2 kcal/mol) and is rather sensitive to the change of the protein environment. This implies that the first reaction step could become the rate-determining step when the protein environment changes through mutagenesis. The QM/MM results in comparison with available experimental data lead to a better understanding of the recently reported experimental observations and provide valuable insights into future design of BChE mutants with a higher catalytic activity against (−)-cocaine. For example, a detailed analysis of the calculated results and the previously reported experimental kinetic data reveals that the rate-determining step of (−)-cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by the A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE becomes the first reaction step and has a significantly higher energy barrier than the third step. Therefore, starting from the A328W/Y332A mutant of BChE, the rational design of BChE mutants to further improve the catalytic activity against (−)-cocaine can primarily aim to decrease the energy barrier for the first reaction step (say through enhancing the hydrogen bonding of the oxyanion hole with the carbonyl oxygen of the substrate) without significantly affecting the ES formation and other chemical reaction steps.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Center for Computational Sciences at the University of Kentucky for supercomputing time on Superdome (a shared-memory supercomputer, with 4 nodes and 256 processors).

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01DA013930 to C.-G. Zhan).

References

- 1.Gawin, F. H., and E. H. Ellinwood Jr. 1988. Cocaine and other stimulants: actions, abuse, and treatment. N. Eng. J. Med. 318:1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landry, D. W. 1997. Immunotherapy for cocaine addiction. Sci. Am. 276:42–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh, S. 2000. Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists. Chem. Rev. 100:925–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paula, S., M. R. Tabet, C. D. Farr, A. B. Norman, and W. J. Ball Jr. 2004. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling of cocaine binding by a novel human monoclonal antibody. J. Med. Chem. 47:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparenborg, S., F. Vocci, and S. Zukin. 1997. Peripheral cocaine-blocking agents: new medications for cocaine dependence: an introduction to immunological and enzymatic approaches to treating cocaine dependence reported by Fox, Gorelick and Cohen in the immediately succeeding articles. Drug Alcohol Depend. 48:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorelick, D. A. 1997. Enhancing cocaine metabolism with butyrylcholinesterase as a treatment strategy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 48:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamendulis, L. M., M. R. Brzezinski, E. V. Pindel, W. F. Bosron, and R. A. Dean. 1996. Metabolism of cocaine and heroin is catalyzed by the same human liver carboxylesterases. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 279:713–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poet, T. S., C. A. McQueen, and J. R. Halpert. 1996. Participation of cytochromes P4502B and P4503A in cocaine toxicity in rat hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 24:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan, W.-J., and M. A. Hedaya. 1999. Cocaine and alcohol interactions in the rat: contribution of cocaine metabolites to the pharmacological effects. J. Pharm. Sci. 88:468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gateley, S. J. 1991. Activities of the enantiomers of cocaine and some related compounds as substrates and inhibitors of plasma butyrylcholinesterase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 41:1249–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatley, S. J., R. R. MacGregor, J. S. Fowler, A. P. Wolf, S. L. Dewey, and D. J. Schlyer. 1990. Rapid stereoselective hydrolysis of (+)-cocaine in baboon plasma prevents its uptake in the brain: implications for behavioral-studies. J. Neurochem. 54:720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masson, P., P. Legrand, C. F. Bartels, M.-T. Froment, L. M. Schopfer, and O. Lockridge. 1997. Role of aspartate 70 and tryptophan 82 in binding of succinyldithiocholine to human butyrylcholinesterase. Biochemistry. 36:2266–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masson, P., W. Xie, M. T. Froment, V. Levitsky, P. L. Fortier, C. Albaret, and O. Lockridge. 1999. Interaction between the peripheral site residues of human butyrylcholinesterase, D70 and Y332, in binding and hydrolysis of substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1433:281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie, W., C. V. Altamirano, C. F. Bartels, R. J. Speirs, J. R. Cashman, and O. Lockridge. 1999. An improved cocaine hydrolase: the A328Y mutant of human butyrylcholinesterase is 4-fold more efficient. Mol. Pharmacol. 55:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duysen, E. G., C. F. Bartels, and O. Lockridge. 2002. Wild-type and A328W mutant human butyrylcholinesterase tetramers expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells have a 16-hour half-life in the circulation and protect mice from cocaine toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 302:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nachon, F., Y. Nicolet, N. Viguie, P. Masson, J. C. Fontecilla-Camps, and O. Lockridge. 2002. Engineering of a monomeric and low-glycosylated form of human butyrylcholinesterase: expression, purification, characterization and crystallization. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhan, C.-G., and D. W. Landry. 2001. Theoretical studies of competing reaction pathways and energy barriers for alkaline ester hydrolysis of cocaine. J. Phys. Chem. A. 105:1296–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkman, C. E., G. E. Underiner, and J. R. Cashman. 1997. Stereoselective inhibition of human butyrylcholinesterase by phosphonothiolate analogs of (+)- and (−)-cocaine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 54:1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun, H., J. El Yazal, O. Lockridge, L. M. Schopfer, S. Brimijoin, and Y. P. Pang. 2001. Predicted Michaelis-Menten complexes of cocaine-butyrylcholinesterase: engineering effective butyrylcholinesterase mutants for cocaine detoxication. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9330–9336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun, H., M. L. Shen, Y. P. Pang, O. Lockridge, and S. Brimijoin. 2002. Cocaine metabolism accelerated by a re-engineered human butyrylcholinesterase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 302:710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun, H., Y. P. Pang, O. Lockridge, and S. Brimijoin. 2002. Re-engineering butyrylcholinesterase as a cocaine hydrolase. Mol. Pharmacol. 62:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan, C.-G., F. Zheng, and D. W. Landry. 2003. Fundamental reaction mechanism for cocaine hydrolysis in human butyrylcholinesterase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:2462–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamza, A., H. Cho, H.-H. Tai, and C.-G. Zhan. 2005. Molecular dynamics simulation of cocaine binding with human butyrylcholinesterase and its mutants. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:4776–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, Y., J. Kua, and J. A. McCammon. 2002. Role of the catalytic triad and oxyanion hole in acetylcholinesterase catalysis: an ab initio QM/MM study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:10572–10577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuxreiter, M., and A. Warshel. 1998. Origin of the catalytic power of acetylcholinesterase: computer simulation studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Case, D. A., D. A. Pearlman, J. W. Caldwell, T. E. Cheatham III, J. Wang, W. S. Ross, C. L. Simmerling, T. A. Darden, K. M. Merz, R. V. Stanton, A. L. Cheng, J. J. Vincent, M. Crowley, V. Tsui, H. Gohlke, R. J. Radmer, Y. Duan, J. Pitera, I. Massova, G. L. Seibel, U. C. Singh, P. K. Weiner, and P. A. Kollman. 2002. AMBER 7. University of California, San Francisco.

- 27.Nicolet, Y., O. Lockridge, P. Masson, J. C. Fontecilla-Camps, and F. Nachon. 2003. Crystal structure of human butyrylcholinesterase and of its complexes with substrate and products. J. Biol. Chem. 278:41141–41147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein, F. C., T. F. Koetzle, G. J. Williams, E. F. Meyer, M. D. Brice, J. R. Rodgers, O. Kennard, T. Shimanouchi, and M. Tasumi. 1977. Protein data bank: computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Biol. 112:535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/.

- 30.Zhan, C.-G., O. Norberto de Souza, R. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Ornstein. 1999. Determination of two structural forms of catalytic bridging ligand in zinc-phosphotriesterase by molecular dynamics simulation and quantum chemical calculation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:7279–7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koca, J., C.-G. Zhan, R. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Ornstein. 2001. Mobility of the active site bound paraoxon and sarin in zinc-phosphotriesterase by molecular dynamics simulation and quantum chemical calculation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123:817–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koca, J., C.-G. Zhan, R. C. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Orstein. 2003. Coordination number of zinc ions in the phosphotriesterase active site by molecular dynamics and quantum mechanics. J. Comput. Chem. 24:368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, and M. L. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berendsen, H. J. C., J. P. M. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, A. DiNola, and J. R. Haak. 1984. Molecular-dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryckaert, J. P., G. Ciccotti, and H. J. C. Berendsen. 1977. Numerical-integration of Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular-dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darden, T. A., H. Lee, and L. G. Pedersen. 1993. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dapprich, S., I. Komaromi, K. S. Byun, K. Morokuma, and M. J. Frisch. 1999. A new ONIOM implementation in Gaussian98. Part I. The calculation of energies, gradients, vibrational frequencies and electric field derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 461:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frisch, M. J., G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, J. A. Montgomery Jr., T. Vreven, K. N. Kudin, J. C. Burant, J. M. Millam, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, M. Cossi, G. Scalmani, N. Rega, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, M. Klene, X. Li, J. E. Knox, H. P. Hratchian, J. B. Cross, C. Adamo, J. Jaramillo, R. Gomperts, R. E. Stratmann, O. Yazyev, A. J. Austin, R. Cammi, C. Pomelli, J. W. Ochterski, P. Y. Ayala, K. Morokuma, G. A. Voth, P. Salvador, J. J. Dannenberg, V. G. Zakrzewski, S. Dapprich, A. D. Daniels, M. C. Strain, O. Farkas, D. K. Malick, A. D. Rabuck, K. Raghavachari, J. B. Foresman, J. V. Ortiz, Q. Cui, A. G. Baboul, S. Clifford, J. Cioslowski, B. B. Stefanov, G. Liu, A. Liashenko, P. Piskorz, I. Komaromi, R. L. Martin, D. J. Fox, T. Keith, M. A. Al-Laham, C. Y. Peng, A. Nanayakkara, M. Challacombe, P. M. W. Gill, B. Johnson, W. Chen, M. W. Wong, C. Gonzalez, and J. A. Pople. 2003. Gaussian 03, Revision A.1. Gaussian, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA.

- 39.Vreven, T., and K. Morokuma. 2000. The ONIOM (our own N-layered integrated molecular orbital plus molecular mechanics) method for the first singlet excited (S-1) state photoisomerization path of a retinal protonated Schiff base. J. Chem. Phys. 113:2969–2975. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vreven, T., K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, H. B. Schlegel, and M. J. Frisch. 2003. Geometry optimization with QM/MM, ONIOM, and other combined methods. I. Microiterations and constraints. J. Comput. Chem. 24:760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tai, K., T. Shen, U. Börjesson, M. Philippopoulos, and J. A. McCammon. 2001. Analysis of a 10-ns molecular dynamics simulation of mouse acetylcholinesterase. Biophys. J. 81:715–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kua, J., Y. K. Zhang, A. C. Eslami, J. R. Butler, and J. A. McCammon. 2003. Studying the roles of W86, E202, and Y337 in binding of acetylcholine to acetylcholinesterase using a combined molecular dynamics and multiple docking approach. Protein Sci. 12:2675–2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberry, T. L. 1975. Catalysis by acetylcholinesterase: evidence that rate-limiting step for acylation with certain substrates precedes general acid-base catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 72:3834–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

44.Alvarez-Idaboy, J. R., A. Galano, G. Bravo-Pérez, and M. E. Ruíz. 2001. Rate constant dependence on the size of aldehydes in the

aldehydes reaction. An explanation via quantum chemical calculations and CTST. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123:8387–8395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

aldehydes reaction. An explanation via quantum chemical calculations and CTST. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123:8387–8395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]