Abstract

The acquisition of a catalytic metal cofactor is an essential step in the maturation of every metalloenzyme, including manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD). In this study, we have taken advantage of the quenching of intrinsic protein fluorescence by bound metal ions to continuously monitor the metallation reaction of Escherichia coli MnSOD in vitro, permitting a detailed kinetic characterization of the uptake mechanism. Apo-MnSOD metallation kinetics are “gated”, zero order in metal ion for both the native Mn2+ and a nonnative metal ion (Co2+) used as a spectroscopic probe to provide greater sensitivity to metal binding. Cobalt-binding time courses measured over a range of temperatures (35–50°C) reveal two exponential kinetic processes (fast and slow phases) associated with metal binding. The amplitude of the fast phase increases rapidly as the temperature is raised, reflecting the fraction of Apo-MnSOD in an “open” conformation, and its temperature dependence allows thermodynamic parameters to be estimated for the “closed” to “open” conformational transition. The sensitivity of the metallated protein to exogenously added chelator decreases progressively with time, consistent with annealing of an initially formed metalloprotein complex (kanneal = 0.4 min−1). A domain-separation mechanism is proposed for metal uptake by apo-MnSOD.

INTRODUCTION

Superoxide dismutases (SODs) (Enzyme Commission No. [E.C. 1.15.1.1]) are essential elements of the cellular defense against reactive oxygen species (1–4). In eukaryotic cells, (Cu,Zn)SOD is the predominant form of SOD in the cytoplasm, and metalloenzyme, including manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) is primarily localized in the mitochondrion (5). In prokaryotic cells, MnSOD and FeSOD are both generally present in the cytoplasm (6), whereas in some cases a (Cu,Zn)SOD is expressed in the periplasm (7). A nickel-dependent SOD has also been reported (8). All of these forms contain a catalytic metal center, making metal binding an important aspect of their biological function. Genetic studies have shown that metal delivery to the eukaryotic (Cu,Zn)SOD requires a specific metallochaperone (9,10), reflecting the extreme toxicity of free copper in the cell (11). However, no chaperone requirement has yet been demonstrated for MnSOD metallation in either eukaryotes or prokaryotes. The relatively innocuous character of Mn2+ suggests the possibility that an intracellular pool of free metal ion may be available for binding to apo-MnSOD, without participation of a metallochaperone carrier protein, although other types of chaperones may be involved in facilitating insertion of the metal cofactor. Metal binding thus appears to be a function that may be intrinsic to Mn and Fe SODs as it is for a number of other proteins, including transferrins (12–15).

Mn and Fe SODs are highly conserved at all levels of structure, with amino acid sequences sharing a high level of similarity across all phyla (16–18). The proteins typically assemble into multimers (dimers or tetramers) of identical subunits, and crystal structures are now available for several of these enzymes (19–22), including Escherichia coli MnSOD (Protein Data Bank ID 1VEW (19); 1D5N (20)). Each subunit adopts a conserved fold, with distinct N- and C-terminal domains. An extensive buried surface is shared between subunits, and a number of side chains arising from the C-terminal domain (e.g., Glu-170, Tyr-174, E. coli MnSOD sequence numbering) span the interface and penetrate into the structure of the opposing subunit, stabilizing the multimer. The two domains within each subunit also share an extensive contact surface but lack the interdigitating side chains characteristic of the subunit interface.

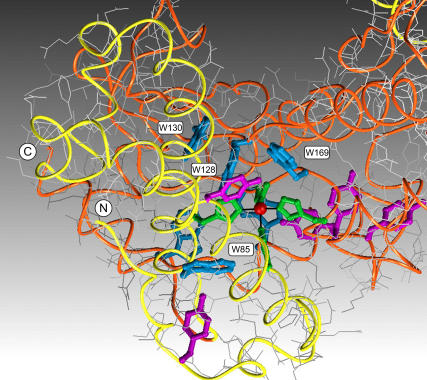

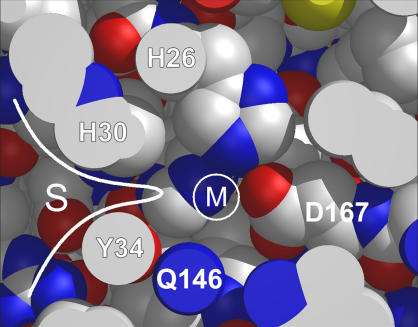

The metal center in the Mn,Fe SOD superfamily of proteins is buried in the protein interior and lies on the interface between N- and C-terminal domains, ligated by four amino acid side chains (His-26, His-81, Asp-167, His-181) (Fig. 1). Two of the metal ligands arise from the N-terminal and two from the C-terminal domain, effectively cross-linking the two domains via the metal complex. The metal binding site is embedded in a cluster of aromatic amino acids that may contribute to controlling the reactivity of the metal center during catalysis (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Environment of the manganese binding site in SOD. One subunit of the homodimeric enzyme is shown, with the active site Mn ion (red) buried in the interior of the protein coordinated by four amino acid side chains (green). Main chain tracing is color coded (yellow, N-terminal; orange, C-terminal), and aromatic amino acids are shown (tyrosine, violet; tryptophan, blue). (Based on Protein Data Bank ID 1VEW).

Although much has been done to investigate the structure and catalytic chemistry of MnSOD (4,23–25), very little is presently known about how the metal ion initially enters the protein to form the mature, catalytic complex. Using a relatively insensitive endpoint assay to analyze the metal binding process, we have previously demonstrated that the metal-free MnSOD apo-protein requires a degree of thermal excitation to bind the metal ion (26–28). This thermally triggered metallation has been interpreted in terms of a temperature-dependent conformational equilibrium of the protein structure, opening to allow access to the buried metal binding site in the higher temperature form (26). Similar behavior has been observed for SODs from hyperthermophilic crenarchae (Pyrobaculum aerophilum) (27), thermophilic eubacteria (Thermus thermophilus) (26), and mesophilic eubacteria (E. coli) (28), with the midpoint temperature of the structural transition roughly correlating with the optimal growth temperature of the source organism in each case. In this work, we have used the quenching of intrinsic protein fluorescence by metal ions in the active site to continuously monitor the metal binding reaction, permitting the first detailed kinetic characterization, to our knowledge, of the apo-MnSOD metal uptake mechanism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Biological materials

E. coli holo- and apo-MnSOD were prepared as previously described (23,28–33).

Metal substitution

Cobalt-substituted dimeric MnSOD (abbreviated Co2-MnSOD) was prepared by incubation of apo-MnSOD (0.5 mM) with cobalt chloride (5 mM) in 20 mM (3-[N-morpholino])propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer, pH 7 at 45°C for 1 h, followed by addition of EDTA (to 10 mM) and dialysis.

Analytical methods

Protein concentrations were routinely determined by optical absorption measurements using the reported molar extinction coefficient (ɛ280 = 8.66 × 104 M−1cm−1) (30). Elemental metal analyses were performed using a Varian SpectrAA 20B atomic absorption spectrometer (Varian, Walnut Creek, CA) equipped with a GTA 96 graphite furnace. Calorimetric measurements were carried out as previously described (28) using a Model 6100 NanoII differential scanning calorimeter (Calorimetry Sciences, Linton, UT). Fluorescence measurements were performed using a Cary Eclipse Spectrofluorimeter (Varian) equipped with a Cary temperature controller and a Peltier 4-position multicell holder. The emission spectra were obtained by excitation of 100 μg/mL protein samples at 280 nm at 25°C, using a dynode voltage of 600 V. For metal uptake studies, 50 μg/mL protein samples were used, and emission intensity was monitored at 333 nm using a dynode voltage of 650 V. The relative contributions of tyrosine and tryptophan to the intrinsic protein fluorescence for apo-MnSOD and Co2-MnSOD were determined as previously described (34), based on the relative intensity of the long-wavelength (385 nm) emission resulting from 275 nm and 295 nm excitation.

Kinetic analysis

Metal binding time courses were initiated by adding an aliquot of the metal stock solution to a thermally equilibrated, stirred solution of apo-MnSOD (50 μg/mL in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7 buffer). Both the protein sample and the metal stock solution were equilibrated at the target temperature for 7 min before starting the reaction. Fluorescence emission intensity was recorded at 1 s−1 sampling frequency for 30 min after addition of metal salts. The kinetic time courses were imported into a data analysis program (Scientist, Micromath Research, St. Louis, MO) and fit to a multiexponential relaxation process. For Mn2+ binding kinetics, a two-exponential fitting analysis was applied to the entire kinetic time course. For Co2+ binding kinetics, the analysis included two exponential relaxation phases, a linear time-dependent term, and a constant offset. For EDTA metal extraction kinetics, the analysis comprised a single exponential phase and a linear time-dependent term.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Protein fluorescence

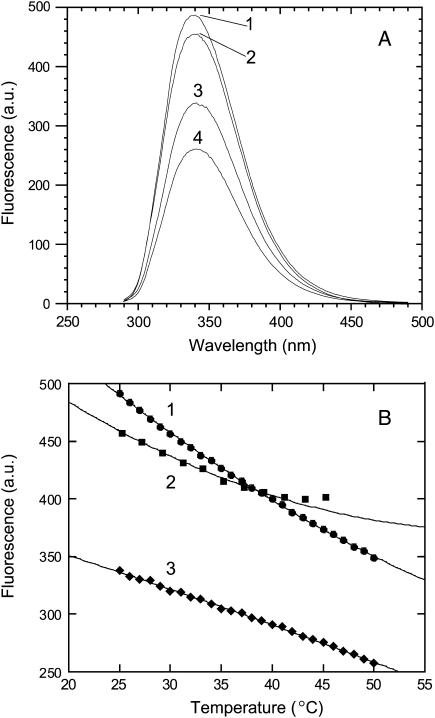

Fluorescence spectra recorded for apo-MnSOD and metallated species containing Mn2+, Mn3+, and Co2+ are shown in Fig. 2 A. All of these samples exhibit an emission maximum near 340 nm on excitation at 280 nm, arising from the intrinsic fluorescence of the aromatic amino acids (six tyrosines and six tryptophans) in the protein. The relative contributions of tyrosine and tryptophan residues to the observed fluorescence intensity can be estimated by measuring the relative emission intensity at long wavelength (385 nm, beyond the tyrosine emission band) under excitation at 275 and 295 nm (34). Based on this method, <5% of the total emission intensity derives from tyrosine for apo-MnSOD, and <1% derives from tyrosine for the homogeneously metallated (Co2+)2-MnSOD dimer. (Mn2+)2-SOD exhibits nearly 90% of the fluorescence intensity observed for the apoprotein, whereas emission from the Co2+ and Mn3+ derivatives is significantly lower (∼65% and 50%, respectively) due to quenching.

FIGURE 2.

Fluorescence properties of SOD derivatives. (A) Fluorescence emission spectra recorded for SOD derivatives, 100 μg/mL in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7 at 25°C, 280 nm excitation: 1), Mn2+ complex; 2), apo-protein; 3), Co2+ complex; and 4), Mn3+ complex. (B) Temperature dependence of fluorescence intensity for SOD derivatives, 100 μg/mL in 20 mM MOPS pH 7, 280 nm excitation as described in Experimental Procedures: 1), Mn2+ complex; 2), apo-protein; and 3), Co2+ complex.

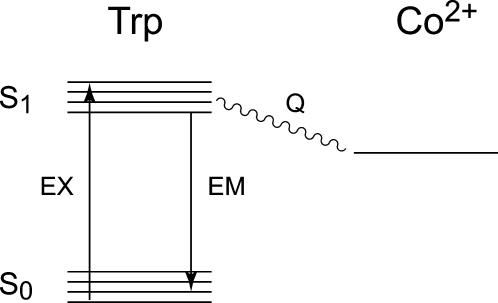

The quenching of fluorescence by metal ions is a consequence of efficient energy transfer between the excited tryptophan residues and the metal center via a Förster transition dipole coupling mechanism (Scheme 1). This mechanism requires the presence of low-lying electronic excited states for the metal complex, allowing it to serve as an acceptor in this process (35). Both Co2+ and Mn3+ complexes have low-lying ligand field and ligand-to-metal charge transfer excited states that overlap the energies of the emitting tryptophan state, accounting for the relatively strong fluorescence quenching effect observed for these two metal ions, whereas Mn2+ lacks low-lying excited states and is associated with little or no quenching of protein fluorescence. Förster energy transfer exhibits a very strong (r6) inverse distance dependence, so the quenching effect is strongest for the 2–3 tryptophan side chains nearest to the metal center (viz. Trp-128, 4.5 Å; Trp-169, 4.8 Å; Trp-85, 6.1 Å) (Fig. 1), qualitatively accounting for the fractional decrease of fluorescence intensity (30–50%) observed for the metallated species.

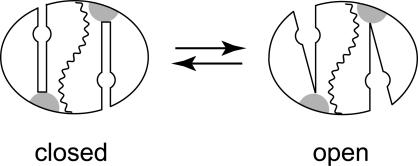

SCHEME 1.

The fluorescence emission intensity observed for all of these samples is temperature dependent (Fig. 2 B). For the metallated complexes, there is a smooth decrease in fluorescence intensity with increasing temperature, whereas for the apo-protein, an anomalous rise in intensity is apparent at higher temperatures (above ∼40°C). At this higher temperature range, apo-MnSOD undergoes a slow aggregation that is detected as an increase in the scattering background in the fluorescence measurements.

Manganese binding kinetics

The change in fluorescence behavior of the protein between apo and metallated states allows the metal binding reaction to be monitored fluorimetrically as a continuous, real-time process. Fig. 3 shows the fluorimetric response to addition of Mn2+ to apo-MnSOD. An initial abrupt decrease in fluorescence, approaching the mixing timescale for this experiment, is followed by two relatively slow phases with oppositely signed amplitudes. The slower relaxation processes can be deconvoluted into two first-order exponential kinetic phases, associated with rate constants (kslow,1 = 0.17 min−1; kslow.2 = 0.05 min−1). Varying the concentration of Mn2+ ion from 10 μM to 300 μM (4.5–130 times the protein concentration) has a negligible effect on both rates, i.e., the reaction is experimentally found to be zero order in Mn2+ ion. This is in contrast to the results observed in the endpoint analysis of the tetrameric thermophilic and hyperthermophilic SODs, which indicated a first-order dependence on Mn2+ ion. For the dimeric E. coli protein, both endpoint (data not shown) and real-time, continuous analyses yield zero-order Mn2+ ion dependence. The lack of metal concentration dependence suggests that the kinetics are “gated”; that is, the rate-limiting step is isomerization of the protein rather than formation of the metal complex. Although the large amplitude of the fluorescence change between apo-MnSOD and the Mn3+ complex (Fig. 2 A) would appear to provide much greater sensitivity to the metal uptake process, the redox instability of the Mn3+ ion in solution precludes using the oxidized metal ion in the metal uptake experiments.

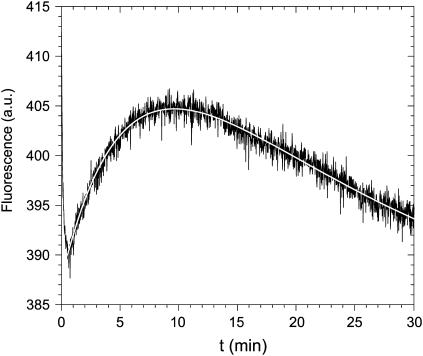

FIGURE 3.

Fluorescence time course for manganese binding. Apo-MnSOD (50 μg/mL) in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7 was equilibrated at 45°C in a thermostated cell holder as described in Experimental Procedures and MnCl2 was added (to a final concentration of 10 μM) to initiate the reaction. A theoretical fit to the data based on two-exponential relaxation is shown (open line).

Cobalt binding kinetics

The small amplitude of the fluorescence emission change resulting from binding Mn2+ makes it difficult to monitor the SOD metallation process with the native metal ion. However, the low specificity of metal interactions that is characteristic of this family of proteins makes it possible to use other metal ions as spectroscopic probes of metal uptake by the apoprotein. Divalent cobalt is known to form an active site complex with SOD (29) and exhibits redox stability in aqueous solution and electronic properties, e.g., the presence of low-lying electronic states that allow it to serve as an efficient excitation acceptor in Förster energy transfer processes.

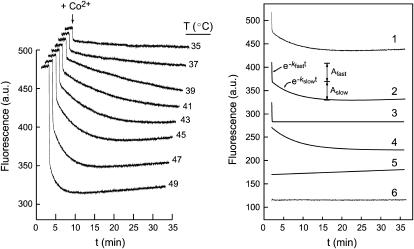

In the presence of Co2+, the fluorescence of apo-MnSOD exhibits complex kinetics (Fig. 4), dominated by two large-amplitude phases (Fig. 4, traces 3 and 4). As observed for Mn2+ binding, the fast phase approaches the mixing timescale for this experiment. The slower phase is consistent with a single-exponential decay associated with a rate constant, kslow = 0.175 min−1, nearly identical to the rate constant of the first slow phase of the Mn2+ binding reaction. The rate is independent of the Co2+ ion concentration (zero-order kinetics). These observations demonstrate the underlying similarity of Mn2+ and Co2+ metal binding reactions, justifying the use of Co2+ as a spectroscopic probe of metal uptake by apo-MnSOD. Although the molecular mechanisms of Co2+ and Mn2+ binding to SOD appear to be the same, the greater quenching associated with Co2+ provides greater sensitivity in the data analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Fluorescence time courses for cobalt binding. (Left) The reaction of apo-MnSOD (50 μg/mL in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7) with Co2+ was monitored at temperatures 35–50°C. The protein was equilibrated in a thermostated cell holder as described in Experimental Procedures, and CoCl2 was added to initiate the reaction. (Right) Each time course was resolved into four components as illustrated for the 45°C data: 1), raw data; 2), sum of slow and fast exponential terms; 3), fast exponential term; 4), slow exponential term; 5), linear term; and 6), residuals.

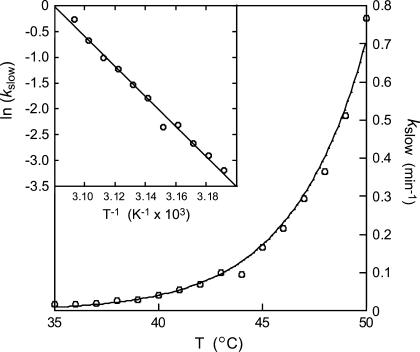

The time courses observed for Co2+ binding by apo-MnSOD have been recorded over a temperature range 35–50°C (Fig. 4). Each trace was fit to a multiphase kinetic process, including two (fast and slow) exponential decays associated with metal binding, a linear term (modeling a scattering contribution from slow aggregation of the protein solution), and a constant offset. The full amplitude of the reaction was fixed by the fluorescence intensity measured for apo-MnSOD and Co2-SOD at each temperature (Fig. 2 B). The rate of the fast exponential phase (kfast) appears to be roughly constant over the entire temperature range, although this may in part reflect the limitations of the instrumentation. On the other hand, the slow-phase rate constant (kslow) steadily increases over this range (Fig. 5). Arrhenius analysis of these data is based on the expression

|

(1) |

where B is the preexponential factor and Ea,slow is the activation energy for the rate process that gates metal uptake by apo-SOD. An Arrhenius plot of the temperature dependence of the rate data (Fig. 5, inset) yields an activation energy Ea,slow = 240 kJ/mol associated with the slow-phase binding reaction.

FIGURE 5.

Temperature dependence of the slow-phase rate constant. The values of kslow for Co2+ binding are shown for the temperature range 35–50°C. An Arrhenius plot of the data is shown (inset) together with theoretical fits for an activation barrier Ea,slow = 240 kJ/mol.

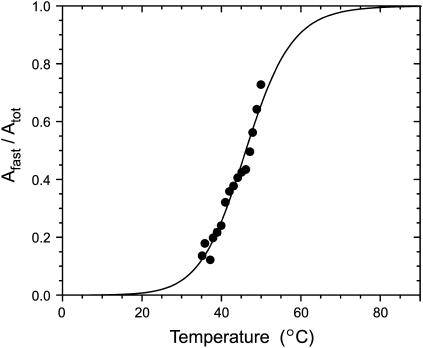

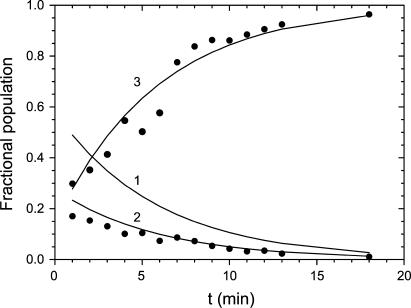

The relative amplitudes of the slow and fast phases (Aslow and Afast, respectively) also vary. The fast phase, a minority of the overall process at 35°C, becomes the majority component at 50°C. The fast amplitude exhibits a step-like temperature dependence (Fig. 6), similar to that previously reported for thermally triggered metal binding by apo-MnSOD based on single-point endpoint analysis (26–28). This suggests that an underlying two-state structural transition in the protein is responsible for the two-phase metal uptake kinetics (36). The ratio of amplitudes (Afast/Aslow) thus reflects the temperature-dependent distribution between two conformational states, a “closed” form stable at low temperature that is unable to bind metal ions directly (with fractional population Fclosed) and an “open” form stable at elevated temperature that supports rapid metal binding (with fractional population Fopen). The ratio Fopen/Fclosed corresponds to the temperature-dependent equilibrium constant, Keq:

|

(2) |

A van't Hoff analysis may be applied to the temperature dependence of the ratio of amplitudes to extract thermochemical parameters for the transition. This analysis yields estimates of the van't Hoff enthalpy (ΔHvH = 146 kJ/mol) and entropy (ΔSvH = 440 J/mol/K), defining a midpoint temperature for the transition, Tm = 46°C, which allow a refinement of the values previously determined by endpoint assay analysis (28).

FIGURE 6.

Temperature dependence of the ratio of amplitudes for fast and slow phases of the cobalt binding reaction. The fractional ratio of the amplitude for the fast phase of the cobalt binding reaction (Afast/Atot) (solid circles) is shown together with a theoretical line (—) corresponding to a process characterized by a temperature-dependent equilibrium with van't Hoff enthalpy ΔHvH = 146 kJ/mol; entropy ΔSvH = 460 J/mol/K; Tm = 46°C.

In contrast to the gated, zero-order kinetics observed for the slow phases of the metal uptake reaction, the rate of the fast phase is sensitive to the metal ion concentration for both Mn2+ and Co2+ binding processes, although the concentration dependence falls short of first-order behavior (data not shown). This suggests that a nongated but saturable metal binding step is associated with this phase, consistent with a metal binding affinity in the range of 106 M−1 for the formation of this initial complex.

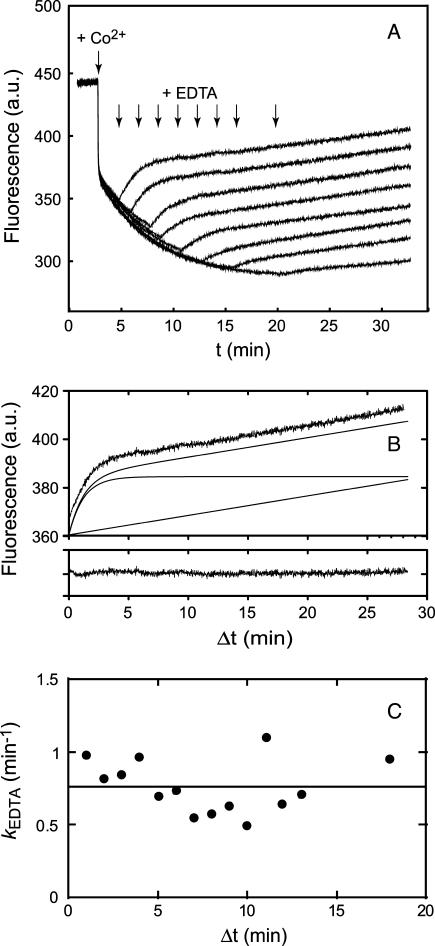

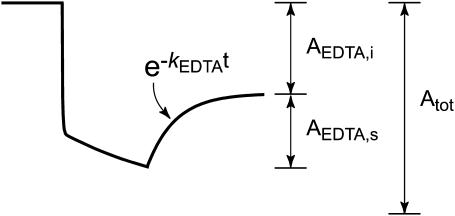

EDTA sensitivity

The presence of a second slow phase in the Mn2+ binding reaction (Fig. 3) suggests the possibility that the first-formed metal complex undergoes an additional relaxation to the final, stable complex. This second slow phase is not resolved in the Co2+ binding reaction, probably because there is very little difference in fluorescence quenching between initial and final complexes. However, it is possible to detect a change in sensitivity of the metallated SOD to an exogenous metal chelator, EDTA, added at various time points during the reaction (Fig. 7). In these experiments, the EDTA is present in large excess over the Co2+ ion both in solution and in the protein, and changes in fluorescence observed after addition of EDTA must be the result of extraction of Co2+ from the metallated protein. Any residual Co2+ in solution is efficiently sequestered by the chelator, effectively blocking further metal uptake. The fluorescence changes associated with addition of EDTA are relatively simple and were analyzed in terms of a single exponential phase plus a linear term that represents the increase in scattering due to protein aggregation during the reaction (Fig. 7 B). The kinetics of metal extraction by EDTA were measured over a range of EDTA concentrations from 30 μM to 160 μM, and the reaction was found to be independent of the chelator concentration (zero order in EDTA), indicating that metal extraction also follows gated kinetics. Addition of EDTA (80 μM) at various time points after the initiation of metal uptake by addition of Co2+ (Fig. 7 A) shows that the rate of metal extraction by EDTA is essentially independent of the time at which the chelator is added (kEDTA = 0.75 min−1) (Fig. 7 C). The amplitude of the EDTA phase does, however, systematically vary with the time of addition. This change in sensitivity to EDTA was evaluated in terms of an EDTA-sensitive amplitude (AEDTA,s) and an EDTA-insensitive amplitude (AEDTA,i) measured for each EDTA reaction time course (Scheme 2). The ratio of these amplitudes to the total amplitude for the reaction in the absence of EDTA (AEDTA,s/Atot and AEDTA,i/Atot) may be interpreted as fractions of the protein sample that have been converted to initial (Co-SODi) and final (Co-SODf) metallated complexes, respectively.

FIGURE 7.

EDTA sensitivity of intermediates in the cobalt binding reaction. (A) Fluorescence time courses observed for reaction of apo-MnSOD (50 μg/mL in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7, 45°C) with reaction initiated by addition of CoCl2 and subsequently interrupted by addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 80 μM. (B) Decomposition of the fluorescence time course observed for addition of EDTA 1 min after initiating cobalt uptake. Raw data (top trace) was decomposed into a single exponential relaxation plus a linear term (lower traces). The residuals resulting from the fit are shown below. (C) Variation of rate constant for cobalt extraction by EDTA with time. The values of kEDTA from analysis of the kinetic traces (open circles) is shown together with the regression line for a constant value (kEDTA = 0.75 min−1).

SCHEME 2.

The time dependence of the EDTA metal extraction amplitudes may be used to determine the elementary kinetic rate constants for the annealing of the protein during metal binding. Experimental amplitude ratios for the EDTA reaction (AEDTA,s/Atot and AEDTA,i/Atot) evaluated at discrete time points during the reaction were fit to the evolution equations for metal binding (Fig. 8). This analysis included the formation and decay of an intermediate, EDTA-sensitive initial complex, incorporating the biphasic uptake behavior that results from the equilibrium mixture of open and closed apoprotein species at the temperature at which the reaction was performed (45°C). Population of the initial complex at various times after addition of Co2+ is uniquely determined by the rate constants for consecutive binding and annealing steps. In the absence of EDTA, the formation and decay of the initial complex is defined by the rate law for a series of sequential reactions and is limited by the gated kinetics of conversion between closed and open forms of apo-MnSOD:

|

(3) |

After addition of EDTA, further metal uptake is blocked by sequestration of free Co2+ in solution, whereas the annealing reaction continues and some of the bound metal ion is extracted by the chelator, leading to a competition between two simultaneous and parallel reactions:

|

(4) |

FIGURE 8.

Analysis of EDTA reaction amplitudes. Experimental results (solid circles) are shown together with theoretical lines representing the fraction of the sample comprising 1), apo-protein; 2), initial EDTA-sensitive metal complex; and 3), final EDTA-insensitive metal complex based on rate constants defined in the Results and Discussion.

In this picture, the EDTA-sensitive protein amplitude evaluated during the EDTA phase is given by the population of Co-SODi at the instant of EDTA addition multiplied by a factor determined by the amplitude of the EDTA extraction reaction in competition with the (simultaneous and parallel) annealing reaction, [kEDTA/(kEDTA + kanneal)]. Similarly, the amplitude of the EDTA-insensitive fraction at that time point will be defined by the population of Co-SODi at the instant of EDTA addition multiplied by a factor determined by the amplitude of the annealing reaction in competition with EDTA-extraction of the metal ion, [kanneal/(kEDTA+kanneal)].

The experimental data were analyzed in terms of this kinetic model. Fixing the EDTA extraction rate constant (kEDTA) and kfast and kslow to the values observed in the earlier experiments allows kanneal to be estimated: kanneal = 0.40 min−1. The theoretical populations of apoprotein (Fig. 8, trace 1) and initial (Fig. 8, trace 2) and final (Fig. 8, trace 3) complexes based on this analysis are superimposed on the data (Fig. 8).

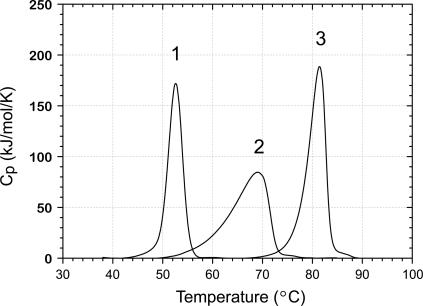

Calorimetric analysis of cobalt binding

The binding affinity for Co2+ may be estimated from the stabilization of the protein by the bound metal ion, as previously demonstrated for Fe and Mn complexes of MnSOD. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis of the unfolding transition for apo-MnSOD, Mn2+, and Co2+ complexes is shown in Fig. 9. Note that the global unfolding transition for apo-MnSOD is four times more endothermic than the transition between open and closed forms of the protein obtained from the van't Hoff analysis (see above). The relatively small magnitude of the domain-opening transition, combined with the slow equilibration rate (kslow = 0.2 min−1 at 46°C) compared to the scan rate (1.5 K/min) may account for the absence of a resolved heat-capacity peak below the global unfolding transition for apo-MnSOD. Thermodynamic parameters for the unfolding transitions for the three species, evaluated from the curves, are given in Table 1. Based on these data, the binding affinity of the Co2+ complex may be estimated:

|

(5) |

Brandt's tight-binding analysis has been applied to indirectly estimate the magnitude of Co2+ binding affinity to the protein based on these data, using an expression for the equilibrium binding affinity derived from the theory of the coupled metal binding and protein unfolding equilibria (28,37–39):

|

(6) |

where KCo(TCo) is the equilibrium binding affinity for formation of the protein-Co2+ complex at the transition temperature for unfolding Co2-MnSOD, ΔHApo is the transition enthalpy for Apo-MnSOD, TApo is the transition temperature for unfolding of Apo-MnSOD, TCo is the transition temperature for unfolding Co2-MnSOD, and ΔCp is the heat capacity change for unfolding Apo-MnSOD. Based on this expression, with the observed ΔH and ΔCp values for MnSOD, a 10°C shift in Tm corresponds to an ∼105-fold increase in KCo. The calorimetric data obtained for samples of Apo-MnSOD and Co2-MnSOD yields an estimate for KCo = 2 × 1014 M−1. The stability of the final complex is thus similar to that of the native Mn3+ form and is somewhat greater than that of the Mn2+ form (4.5 × 109 M−1 in this study, similar to the earlier value reported in a previous study (3 × 109 M−1)(28)), indicating a slightly larger driving force for forming the final complex for Co2+ compared to Mn2+ even though both are believed to bind in the same site in the protein (29).

FIGURE 9.

Unfolding transitions for MnSOD derivatives. Samples for DSC were prepared with 2 mg/mL protein in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7 and scanned at 1.5 K/min: 1), Apo-MnSOD; 2), (Mn2+)2-SOD; and 3), (Co2+)2-SOD.

TABLE 1.

Calorimetric data for MnSOD samples

| Sample* | Tm (°C) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔCp (kJ/mol·K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apo-MnSOD | 52.6 | 582† | 13† |

| (Mn+2)2-MnSOD‡ | 69.1 | 797 | n.d.§ |

| (Co+2)2-MnSOD¶ | 81.4 | 869 | n.d.§ |

Samples contained (final concentration) 2 mg/mL protein in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7 prepared as described in Experimental Procedures.

(27).

Homogeneous Mn2+-metallated dimeric MnSOD.

Not determined.

Homogeneous Co2+-metallated dimeric MnSOD.

Mechanism for metal uptake by Apo-MnSOD

X-ray structures have been solved for both apo-MnSOD and the Mn-containing complex of P. aerophilum SOD (40). The two forms have nearly identical crystal structures, differing essentially only in the presence or absence of the metal ion. E. coli apo-MnSOD is expected to be similar, accounting for the inability of metal ions to readily bind to the vacant active site. Access to the binding site is sterically constrained by the “gateway” residues (including His-30 and Tyr-34), which restrict access in the substrate funnel to only the smallest ions and molecules (Fig. 10). In addition, the presence of conserved cationic residues (e.g., Lys-29, Arg-181) that are thought to function as electrostatic guides for the anionic substrate create a large electrostatic barrier to binding cationic metal ions in the closed form of the protein.

FIGURE 10.

Steric constraints on access to the metal binding site in MnSOD in the native folded state. A cross-sectional view of the active site of E. coli MnSOD is shown, with viewing plane oriented on the only surface-accessible channel to the buried metal binding site. The position of the coordinated metal ion (M) is shown relative to ligating residues (H-26 and D-167 in the inner sphere, Q-146 in the outer sphere) and gateway residues (H-30 and Y-34) that restrict access to the active site from within the substrate channel (S). A metal ion entering the buried binding site from solution must penetrate the gateway barrier (white line), which would be expected to require complete desolvation of the metal cation.

As has been previously noted, the two domains of each subunit are linked via a short “hinge” peptide, located on each subunit opposite the substrate funnel. This peptide serves as a constraint on the relative motions of the two domains and may be expected to be a fixed point in the dynamics of the domain interface. The transition between closed and open forms of the protein (Scheme 3) likely involves a rotation of the peptide dihedrals within the hinge linker (represented by the shaded region in Scheme 3), allowing the two domains to separate to a greater or lesser extent. Domain separation is expected to be relatively facile because there are no side chains spanning the domain interface. This is quite different from the subunit interface, which is similarly a buried surface but includes a number of residues that cross over between subunits and insert into the packing of the opposing subunit. The domain interface is largely hydrophilic and includes several buried water molecules. As a result, exposing this surface to solvent by separating the domains is not expected to be unfavorable. The equilibrium between closed and open forms of the apoprotein is temperature dependent, favoring the closed form below and the open form above the midpoint temperature (Tm = 46°C), and there is also a substantial activation barrier associated with this process. Based on earlier studies of thermally triggered metal uptake by mesophilic, thermophilic, and hyperthermophilic SODs, the dynamical behavior of each protein has evolved to match the open/closed transition to the physiological growth temperature of the source organism. For T. thermophilus and P. aerophilum SODs, Tm values are elevated to 65°C and 75°C, respectively. Metal binding to the open form of the apoprotein is expected to be very fast, whereas metal uptake by the closed form of the protein requires conversion to the open form, and interconversion between closed and open forms becomes the rate limiting step to metallation. In this case, metal binding becomes independent of the metal ion concentration in solution and is associated with gated kinetics as observed in these experiments.

SCHEME 3.

Once a metal ion enters the active site, a relatively unstable initial complex is formed that is distinguished from the final complex in its susceptibility to extraction of the metal ion by chelators in solution. Like metal uptake, extraction of the metal ion by chelators appears to require a conformational change in the protein, gating the EDTA metal extraction process and giving rise to zero-order EDTA kinetics. The remodeling of the protein between the initial and final states is reflected not only in a progressive change in the EDTA sensitivity of the Co2+-bound protein (Figs. 7 and 8), but also in a slow relaxation phase observed in the Mn2+ binding experiments (Fig. 3). The buried metal center in the initial complex can become accessible to EDTA, indicating that the side-chain packing and metal interactions across the domain interface may not be well formed at this stage. The interface may be expected to resemble the “molten globule” stage of protein folding, where the elements of secondary structure are formed but defects remain in the packing of individual amino acid side chains (41). The analysis of the EDTA interaction kinetics provides an estimate of the rate constant for resolution of the side-chain packing in the maturation of the metallated MnSOD, kanneal = 0.4 min−1, which is four times faster than the slowest relaxation phase observed for Mn2+ binding (kslow,2 = 0.05 min−1), suggesting the possibility of a multistep annealing process, although it may also reflect the different stabilities of the final complexes.

CONCLUSIONS

The acquisition of a metal cofactor is an essential stage in the expression of biological function for a metalloenzyme. Although metallochaperones have been found to be required for metallation of certain classes of metalloenzymes, particularly when toxic metals (Cu, Ni) (9–11,42,43) or complex cofactor structures (e.g., nitrogenase FeMoCo) (44) are involved, other proteins may acquire their metal cofactor without assistance of a specific chaperone. Mechanisms of metal uptake are poorly understood for the vast majority of metalloproteins and metalloenzymes (42), with some notable exceptions. Iron binding and release by transferrins in particular has been extensively studied and shown to depend on a discrete conformational transition involving separation of domains. In that case, the role of the hinge domain linker peptide in the conformational change has been established by crystallographic analysis of both open and closed forms (12–15).

For the Mn,Fe family of SODs, studies on metal interactions are just beginning. Previous work aimed at defining the metal binding affinity of MnSOD for both native and nonnative metal ions revealed a surprisingly low value of the formation constant (Kf) for the metal complex (28). This relatively low binding affinity appears to be at odds with the well-documented difficulty in extracting the metal cofactor from the metallated proteins, and, together with the thermally triggered metal uptake that is characteristic of this family of proteins (26–28), suggests a kinetic rather than a thermodynamic basis for the apparent stability of the metal complex. In this work, the elementary steps involved in the apo-MnSOD metal insertion process have been resolved and characterized for the first time through continuous monitoring of intrinsic protein fluorescence during uptake of metal ions from solution. The results are consistent with a simple model that reveals important new roles for the well-known structural features in this family of proteins. The two-domain organization of each subunit defines a metal-binding unit that must undergo a conformational change, opening the domain interface in order for metal binding to occur. We propose that the domain linker peptide in MnSOD (corresponding to a conserved proline and glycine-rich sequence element, residues 90–94) plays a key role in this process. This is consistent with the observation that only limited unfolding appears to be required for metal uptake by E. coli MnSOD at temperatures well below the temperature of the global unfolding transition for the apoprotein. The transition from the closed to the open form of apo-MnSOD (Scheme 3) may be thought of as a change of state for the molecule, analogous to the melting of a molecular solid (45). Some degree of thermal excitation is required for metal binding, not only to overcome the activation barrier to domain opening, which controls the rate of metal uptake and is reflected in the gated uptake kinetics, but to shift the distribution of protein conformations in favor of the open form, which permits rapid metal binding to occur.

It is still unclear whether the in vitro metal uptake process that is described here is identical to in vivo metallation. The lack of evidence for manganese chaperones in any biological system and the relatively low metal selectivity demonstrated for intracellular metallation of MnSOD leave open the possibility of a chaperone-independent metallation in vivo. Even in the absence of a metal-delivery chaperone, the metallation process could be facilitated by interactions with ancillary proteins that lower the activation barrier for domain opening. The in vitro metal uptake system that we have developed may in fact be useful in assaying for putative chaperones or ancillary factors for SOD metallation. It is also possible that in vivo, apo-MnSOD acquires its metal cofactor cotranslationally, before the nascent peptide completely anneals into the closed form. Experiments are currently in progress to investigate these possibilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant GM42680 (to J.W.W.) and a grant from Shriners Hospital (to H.P.B.).

References

- 1.Fridovich, I. 1997. Superoxide anion radical, superoxide dismutases, and related matters. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18515–18517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCord, J. M. 1993. Oxygen-derived free radicals. New Horiz. 1:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fridovich, I. 1995. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittaker, J. W. 2000. Manganese superoxide dismutase. Met. Ions Biol. Syst. 37:587–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisiger, R. A., and I. Fridovich. 1973. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Site of synthesis and intramitochondrial localization. J. Biol. Chem. 248:4793–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton, L., and I. Fridovich. 1977. Intracellular localization of the superoxide dismutases of Escherichia coli: a reevaluation. J. Bacteriol. 131:815–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benov, L., L. Y. Chang, B. Day, and I. Fridovich. 1995. Copper, zinc superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli: periplasmic localization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 319:508–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youn, H. D., E. J. Kim, J. H. Roe, Y. C. Hah, and S. O. Kang. 1996. A novel nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces spp. Biochem. J. 318:889–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenzweig, A. C., and T. V. O'Halloran. 2000. Structure and chemistry of the copper chaperone proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 4:140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field, L. S., E. Luk, and V. C. Culotta. 2002. Copper chaperones: personal escorts for metal ions. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 34:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rae, T. D., P. J. Schmidt, R. A. Pufahl, V. C. Culotta, and T. V. O'Halloran. 1999. Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science. 284:805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker, H. M., and E. N. Baker. 2004. Lactoferrin and iron: structural and dynamic aspects of binding and release. Biometals. 17:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pakdaman, R., M. Petitjean, and J.-M. El Hage Chahine. 1998. Transferrins—a mechanism for iron uptake by lactoferrin. Eur. J. Biochem. 254:144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdallah, F. B., and J.-M. El Hage Chahine. 1999. Transferrins, the mechanism of iron release by ovotransferrin. Eur. J. Biochem. 263:912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeffrey, P. D., M. C. Brewley, R. T. A. MacGilliveray, A. B. Mason, R. C. Woodworth, and E. N. Baker. 1998. Ligand-induced conformational change in transferrins: crystal structure of the open form of the N-terminal half-molecule of human transferrin. Biochemistry. 37:13978–13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker, M. W., and C. C. Blake. 1988. Iron- and manganese-containing superoxide dismutases can be distinguished by analysis of their primary structures. FEBS Lett. 229:377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker, M. W., C. C. Blake, D. Barra, F. Bossa, M. E. Schinina, W. H. Bannister, and J. V. Bannister. 1987. Structural identity between the iron- and manganese-containing superoxide dismutases. Protein Eng. 1:393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin, M. E., B. R. Byers, M. O. Olson, M. L. Salin, J. E. Arceneaux, and C. Tolbert. 1986. A Streptococcus mutans superoxide dismutase that is active with either manganese or iron as a cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9361–9367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards, R. A., H. M. Baker, M. M. Whittaker, J. W. Whittaker, G. B. Jameson, and E. N. Baker. 1998. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli manganese superoxide dismutase at 2.1 Å resolution. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 3:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borgstahl, G. E., M. Pokross, R. Chehab, A. Sekher, and E. H. Snell. 1999. Cryotrapping the six-coordinated, distorted-octahedral active site of manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Mol. Biol. 296:951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lah, M. S., M. M. Dixon, K. A. Pattridge, W. C. Stallings, J. A. Fee, and M. L. Ludwig. 1995. Structure-function in Escherichia coli iron superoxide dismutase: comparisons with the manganese enzyme from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry. 34:1646–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borgstahl, G. E., H. E. Parge, M. J. Hickey, W. F. Beyer Jr., R. A. Hallewell, and J. A. Tainer. 1992. The structure of human mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase reveals a novel tetrameric interface of two 4-helix bundles. Cell. 71:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittaker, J. W., and M. M. Whittaker. 1991. Active site spectral studies on manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:5528–5540. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bull, C., E. C. Niederhoffer, T. Yoshida, and J. A. Fee. 1991. Kinetic studies of superoxide dismutases: properties of the manganese-containing protein from Thermus thermophilus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:4069–4076. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu, J. L., Y. Hsieh, C. Tu, D. O'Connor, H. S. Nick, and D. N. Silverman. 1996. Catalytic properties of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17687–17691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittaker, M. M., and J. W. Whittaker. 1999. Thermally triggered metal binding by recombinant Thermus thermophilus manganese superoxide dismutase, expressed as the apo-enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34751–34757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whittaker, M. M., and J. W. Whittaker. 2000. Recombinant superoxide dismutase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrobaculum aerophilum. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 5:402–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuno, K., M. M. Whittaker, H. P. Bächinger, and J. W. Whittaker. 2004. Calorimetric studies on the tight binding metal interactions of Escherichia coli manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 279:27339–27344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ose, D. E., and I. Fridovich. 1979. Manganese-containing superoxide dismutase from Escherichia coli: reversible resolution and metal replacements. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 194:360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beyer, W. F. Jr., J. A. Reynolds, and I. Fridovich. 1989. Differences between the manganese- and the iron-containing superoxide dismutases of Escherichia coli detected through sedimentation equilibrium, hydrodynamic, and spectroscopic studies. Biochemistry. 28:4403–4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vance, C. K., and A.-F. Miller. 1998. A simple proposal that can explain the inactivity of metal-substituted superoxide dismutases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:461–467. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittaker, M. M., and J. W. Whittaker. 1998. A glutamate bridge is essential for dimer stability and metal selectivity in manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22188–22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quijano, C., D. Hernandez-Saavedra, L. Castro, J. M. McCord, B. A. Freeman, and R. Radi. 2001. Reaction of peroxynitrite with Mn-superoxide dismutase. Role of the metal center in decomposition kinetics and nitration. J. Biol. Chem. 276:11631–11638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yélamos, B., E. Núñez, J. Gómez-Guitiérrez, M. Datta, B. Pacheco, D. L. Peterson, and F. Gavilanes. 1999. Circular dichroism and fluorescence spectroscopic properties of the major core protein of feline immunodeficiency virus and its tryptophan mutants. Assignment of the individual contribution of the aromatic sidechains. Eur. J. Biochem. 266:1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horrocks, W. D. Jr. 1993. Luminescence spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 226:495–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whittaker, J. W. 2003. The irony of manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:1318–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandts, J. F., C. Q. Hu, and L.-N. Lin. 1989. A simple model for proteins with interacting domains. Applications to scanning calorimetry data. Biochemistry. 28:8588–8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandts, J. F., and L.-N. Lin. 1990. Biochemistry. 29:6927–6940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, L.-N., A. B. Mason, R. C. Woodworth, and J. F. Brandts. 1993. Calorimetric studies of the N-terminal half-molecule of transferrin and mutant forms modified near the Fe(3+)-binding site. Biochem. J. 293:517–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jameson, G. B., J. J. Adams, P. D. Hempstead, B. F. Anderson, I. Morgenstern-Badarau, J. W. Whittaker, and E. N. Baker. 2003. Superoxide dismutases from hyperthermophiles: clues to metal-ion specificity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 96:70. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levitt, M., M. Gerstein, E. Huang, S. Subbiah, and J. Tsai. 1997. Protein folding: the endgame. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:549–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuchar, J., and R. P. Hausinger. 2004. Biosynthesis of metal sites. Chem. Rev. 104:509–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blokesch, M., A. Paschos, E. Theodoratou, A. Bauer, M. Hube, S. Huth, and A. Böck. 2002. Metal insertion into NiFe-hydrogenases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30:674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dos Santos, P. C., D. R. Dean, Y. Hu, and M. W. Ribbe. 2004. Formation and insertion of the nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor. Chem. Rev. 104:1159–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whittaker, J. W. 1997. A model for local melting of metalloprotein structure. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:674–677. [Google Scholar]