Abstract

In order to ensure a productive life cycle, human papillomaviruses (HPVs) require fine regulation of their gene products. Uncontrolled activity of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 results in the immortalization of the infected epithelial cells and thus prevents the production of mature virions. Ectopically expressed E2 has been shown to suppress transcription of the HPV E6 and E7 region in cell lines where the viral DNA is integrated into the host genome, resulting in growth inhibition. However, it has been demonstrated that growth control of these cell lines can also occur independently of HPV E2 transcriptional activity in high-risk HPV types. In addition, E2 is unable to suppress transcription of the same region in cell lines derived from cervical tumors that harbor only episomal copies of the viral DNA. Here we show that HPV type 16 (HPV-16) E2 is capable of inhibiting HPV-16 E7 cooperation with an activated ras oncogene in the transformation of primary rodent cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate a direct interaction between the E2 and E7 proteins which requires the hinge region of E2 and the zinc-binding domain of E7. These viral proteins interact in vivo, and E2 has a marked effect upon both the stability of E7 and its cellular location, where it is responsible for recruiting E7 onto mitotic chromosomes at the later stages of mitosis. These results demonstrate a direct role for E2 in regulating the function of E7 and suggest an important role for E2 in directing E7 localization during mitosis.

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are a large family of small, double-stranded DNA viruses. They infect cutaneous and mucosal epithelial tissue at different anatomical locations, resulting in a variety of clinical symptoms ranging from benign warts to invasive genital cancers (13, 29). Infection with the high-risk types, most commonly HPV type 16 (HPV-16) and HPV-18, has been associated with the development of more than 99% of cervical cancer cases. The tumorigenicity of HPV is dependent on the activity of two virally encoded oncoproteins, E6 and E7. These bind at a high affinity and disrupt the function of p53 (46) and the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein pRB (6, 20), respectively. While E6 plays a role in inhibiting apoptosis and interfering with cell adhesion and polarity (30), E7 acts by driving S-phase progression, regulating gene expression, and interfering with the activities of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (23). In addition to inactivating the function of pRB, other cellular targets of E7 include the TATA box-binding protein (TBP) (31), TBP-associated factors (35), members of the AP-1 transcription factor family (2), and histone deacetylases (7). E7 is a small phosphoprotein that shares some sequence homology with the adenovirus E1a protein and the simian virus 40 large T antigen (8). E7 is 98 amino acids in length and contains a zinc-binding domain in the C-terminal region whose structural integrity is necessary for the activity of E7 (2, 26). While both E6 and E7 cooperate to induce immortalization of keratinocytes, expression of E7 alone is sufficient to induce DNA synthesis in differentiated keratinocytes (9) and invasive cervical cancer in transgenic mice (41).

Clinical studies have revealed a long latency period between primary infection with HPV and the development of invasive tumors (61). HPV-driven tumors are invariably characterized by elevated levels of E6 and E7 expression and the frequent integration of the viral episome into the host genome, which is accompanied by loss of some viral DNA sequences. These observations suggest a possible role for other viral proteins in controlling malignant progression. Integration of the virus genome generally involves the linearization, and thus breakage, of viral DNA within the coding sequence of viral transcriptional factor E2, thus disrupting its expression (10). Indeed, several studies have shown that ectopically expressed E2 protein can suppress expression of E6 and E7 in HPV-transformed cell lines (14, 24, 55), suggesting that loss of E2 transcriptional repression results in uncontrolled expression of the viral oncoproteins, which might contribute to HPV-induced malignancy.

Major functions of E2 involve regulating viral DNA replication and viral gene expression. E2 binds specifically as a homodimer to a consensus palindromic sequence (ACCN6GGT) (1), and several E2-binding sites are present in the long control region (LCR) of the viral genome. Two E2-binding sites in the LCR flank the viral origin of replication where E2 binds and recruits the viral helicase E1 (21). A third E2-binding site in the LCR is located directly upstream of the early promoter (p97 in HPV16 and p105 in HPV18) which controls the expression of E6 and E7 (42, 44). When transfected into HPV-transformed cell lines, E2 is thought to bind to this promoter region and suppresses the transcriptional expression of E6 and E7, which results in cell cycle arrest (14, 24). However, this activity of E2 was shown to be dependent on the DNA template (36) and the chromatin structure (4). E2 is only effective in controlling the expression of E6 and E7 from integrated, and not episomal, DNA in cell lines derived from cervical tumors. We were therefore interested in investigating possible roles for E2 in controlling the activity of E7 in a manner independent of its transcriptional function. By using baby rat kidney (BRK) transformation assays, we show that E2 inhibits E7-induced transformation and that this inhibition is not due to repression of E7 expression by the E2 protein. In addition, we show that E2 and E7 interact directly and that this binding maps to a region in the C-terminal half of E7 which overlaps the site of interaction of several important E7 binding partners. In addition, E2 stabilizes E7 and recruits it to mitotic chromosomes at telophase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and transfection.

U2OS (human osteosarcoma), BRK, and CaSKi (human cervical carcinoma, HPV16-positive) cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. U2OS and BRK cells were transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation as described previously (34).

Plasmids.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion plasmids were all cloned in pGEX-2T, including HPV-16 E2 (39), E7 (33), E1 (53), mutant forms of E2 (32), 11E2 (25), and TBP (31). The truncations below were cloned into pGEX-2T by PCR with the following primers: for the truncation of E2 with residues spanning positions 249 to 365, forward primer 5′ GACACCGGATCCCCCTGCCACACC and reverse primer 5′ GTTGTGAATTCAGTATCAAGATTTGTCATATA; for the N-terminal half of 16E7, forward primer 5′ ACGTAGGGATCCCCAGCTGTAATC and reverse primer 5′ CTGGAATTCCAGCTGGACCATCTAT; and for the C-terminal half of 16E7, forward primer 5′ CCAGGATCCCAAGCAGAACCGGAC and reverse primer 5′ CTCTTCCGAATTCGTACCTGCAGG. His-tagged E7 was cloned as described in reference 40. For in vitro translations, 16E7 was cloned in plasmid pSP64 (33), 16E2 was cloned in pcDNA (5), the N- and C-terminal halves of 16E2 were cloned in pSP64 (39), mutant forms of 16E7 were cloned in pSP64 (33), and 11E7 was cloned in pcDNA from pJ4Ω plasmids (54) at the EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites. For in vivo expression, the following plasmids were used: pGFP-N1 (Clontech), 16E2 in pCMV (5), pJ4Ω:16E7 (54), adenovirus E1a (47), and Ras (pEJ6.6) (52). The Δ3 and Δ4 mutant forms of E7 were cloned from plasmid pSP64 into pcDNA at the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites.

Antibodies.

Anti-hemagglutinin (HA) monoclonal antibody 12CA5 (Roche) was used to detect HA-tagged proteins in Western blot and immunofluorescence assays. Mouse monoclonal antibody against E2 and anti-E2 polyclonal antibody have been described previously (27, 32). In addition, the following commercial antibodies were used: anti-β-gal (anti-β-galactosidase; Promega), polyclonal rabbit anti-α-actin (Sigma), mouse anti-16E7 (ED17; Santa-Cruz), and polyclonal rabbit anti-HA (Santa-Cruz).

BRK transformation assay.

Primary BRK cells from 9-day-old Wistar rats were transfected with 6 μg of either pJ4Ω:HPV-16E7 or an adenovirus E1a-encoding plasmid along with 3 μg of EJ-ras and 3 μg of pcDNA encoding neomycin resistance, with or without the indicated amounts of 16E2. Cells were placed under selection in growth medium containing 200 μg/ml G418 for 2 weeks and then fixed, and colonies were stained with Giemsa Blue (Diagnostica Merck).

Fusion protein purification and in vitro binding assays.

GST- and His-tagged fusion proteins were expressed and purified as described previously (56). The purity of the fusion proteins was tested by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Coomassie staining. In vitro translations were performed with rabbit reticulocyte lysate or wheat germ extract and the Promega TNT system, and radiolabeling was done with [35S]cysteine (Amersham). Equal amounts of in vitro-translated proteins were added to GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione resin and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. After extensive washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.25% NP-40, or as otherwise indicated, the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Binding assay results were quantified with a PhosphorImager, and the percentage of binding with respect to the inputs was calculated.

GST pulldown from cellular extracts was performed by incubating GST fusion proteins immobilized on resin with cell extract for 1 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel. The resin was then washed extensively with the extraction buffer, and bound proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blot assay with the appropriate antibodies.

Direct binding assays were performed by incubating GST fusion proteins immobilized on resin with purified His-tagged 16E7 that had been eluted with imidazole-containing buffer for 1 h at 4°C. After extensive washing, the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-16E7 antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Total cellular extracts were prepared by directly lysing cells from six-well dishes in SDS loading buffer. To obtain the soluble and insoluble cellular fractions separately, cells were lysed in E1A buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 0.1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor cocktail I [Calbiochem]). After incubation on ice for 20 min, lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 1,300 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant (soluble fraction) and pellet (insoluble fraction) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot assays as described previously (25).

For coimmunoprecipitation, U2OS cells were transfected with the appropriate plasmids encoding HA-tagged E7 and E2. At 24 h later, E1A extraction was performed and the soluble fraction was incubated with anti-HA beads (Sigma) for 3 to 4 h on a rotating wheel at 4°C. Precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-E2 polyclonal antibody.

Half-life experiments.

CaSKi cells were transfected with 3 μg of a plasmid expressing E2 by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated for different times (0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min) with cycloheximide (50 μg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) to block protein synthesis. Total cellular extracts were then analyzed by Western blot assay, and the intensities of the bands on the X-ray film were measured with Adobe Photoshop. The standard deviation was calculated from three independent assays.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from CaSKi cells (transfected as above) and BRK cells (transfected as in the transformation assay) 24 h after transfection with TRI Reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1 μg of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) with the RETROscript system (Ambion). A control without reverse transcriptase was also added for assaying contamination with DNA. PCR was performed with 20 cycles and an annealing temperature of 55°C for E2, green fluorescent protein (GFP), and actin and 58°C for E7. PCR primers for actin, E7 (59), and GFP (25) have been described previously. 16E2 primers were as follows: forward, 5′ ATGGAGACTCTTTGCCAA; reverse, 5′ TCATATAGACATAAATCCAGTAGACAC.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy.

Cells were stained and fixed for immunofluorescence as described previously (25). Briefly, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antibodies were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C, followed by extensive washing in PBS and incubation for 30 min at 37°C with secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody conjugated with fluorescein or rhodamine (Molecular Probes). For visualization of chromosomes, cells were stained with Hoechst stain (bisbenzimide; Sigma no. 33258). Samples were then washed several times with water and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories Inc.) on glass slides.

Slides were analyzed with either a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope equipped with a Leica photo camera (A01M871016) or a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with two lasers giving excitation lines at 480 and 510 nm. The data were collected with a 100× objective oil immersion lens.

RESULTS

HPV-16 E2 inhibits E7-induced transformation.

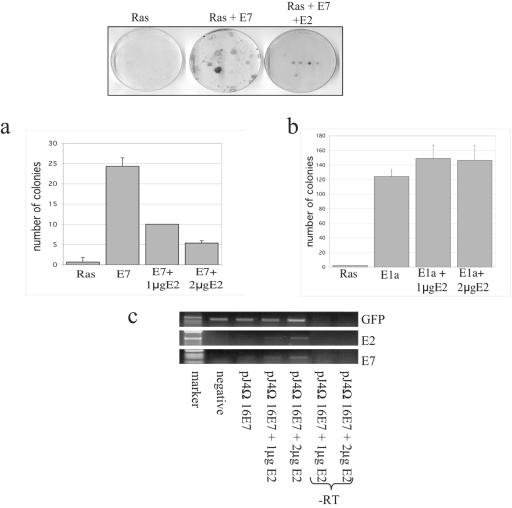

Previous studies have shown that overexpression of the E2 protein resulted in growth arrest in cell lines containing integrated HPV DNA due to suppression of E6 and E7 gene transcription (14, 22). We were interested in whether E2 had any direct effects upon the transformation activity of E7 in the absence of an E2-responsive promoter. To do this, we used primary BRK cells transfected with HPV-16 E7 and EJ-ras, with or without HPV-16 E2 (31). For comparison, we also included in parallel adenovirus E1a and EJ-ras transfections. After 2 weeks of selection, the cells were fixed and stained and the colonies counted. The results obtained are shown in Fig. 1a, where it can be seen that HPV-16 E2 is a potent inhibitor of E7 transforming activity. This effect of E2 appears to be specific since, in contrast, E2 has no effect on the transforming activity of adenovirus E1a (Fig. 1b). To verify that the expression of E7 from the pJ4Ω plasmid was not inhibited by the E2 expression plasmid, we analyzed the level of E7 gene expression 24 h after transfection into BRK cells by RT-PCR analysis. Figure 1c shows that E2 does not inhibit E7 expression in this assay system, suggesting that E2 suppression of E7-induced transformation is at the posttranscriptional level.

FIG. 1.

The transformation activity of E7 is inhibited in the presence of E2. Primary BRK cells from 9-day-old Wistar rats were transfected with 6 μg of plasmids expressing HPV-16 E7 (a) or adenovirus E1a (b) together with Ras as a cooperating oncogene and pcDNA carrying a selectable marker. Cells were maintained in medium containing 200 μg/ml G418 for 2 weeks and then fixed and stained, and the colonies were counted (as shown at the top). The chart shows the mean of three independent experiments, and error lines indicate standard deviations. (c) BRK cells treated as described for panel a were transiently transfected with 6 μg of plasmid pJ4Ω expressing E7 and increasing amounts of E2, along with a GFP-expressing plasmid as a control for transfection efficiency. One microgram of total cell RNA was reverse transcribed, and the expression of E2, E7, and GFP was analyzed by PCR with specific primers. -RT, controls without RT.

E2 and E7 bind directly.

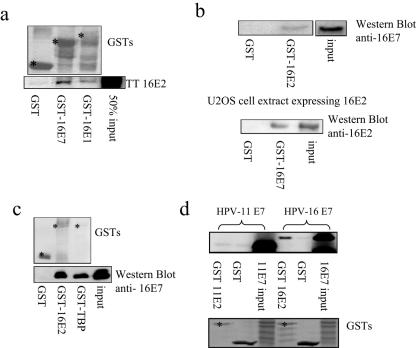

The above result indicates a specific effect of E2 on E7 function that is independent of E2's transcriptional activities with respect to the HPV promoter. Since previous studies have shown that E2 interacts with E6 (25), we were interested in investigating whether E2 could also associate with E7 and thereby modulate E7 activities. To do this, we performed GST pulldown assays with bacterially expressed, GST-tagged proteins immobilized on resin. All binding assays were performed for 1 h on ice, and the reaction mixture was extensively washed with a detergent-containing buffer. As shown in Fig. 2a, HPV-16 E2 bound strongly to the positive control of GST-16E1, as well as to GST-16E7. No interaction was detected with GST alone. To investigate whether E7 could also pull down E2 expressed in vivo, GST-16E7 was incubated with an extract from U2OS cells transiently transfected with a 16E2 expression plasmid and, as can be seen in Fig. 2b (bottom), GST-16E7 retained significant amounts of 16E2 from the cell extract. In addition, with a CaSKi cell extract as a source of E7 protein, significant binding was detected with a GST-16E2 fusion protein (Fig. 2b, top).

FIG. 2.

E2 and E7 interact in vitro. (a) In vitro-translated and radiolabeled 16E2 in reticulocyte lysate was incubated with GST, GST-16E7, and GST-16E1. The 50% input of E2 (TT E2) is shown, and bound proteins were assessed by autoradiography (bottom) and the input GST fusion proteins were visualized by staining the gels with Coomassie blue (top). (b) Extracts from U2OS cells expressing 16E2 and CaSKi cells expressing 16E7 were incubated with GST-16E7 and -16E2, respectively. Bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-E2 polyclonal (bottom) and anti-E7 monoclonal (top) antibodies. (c) A direct binding assay was performed with GST-16E2 incubated with purified, His-tagged 16E7. GST alone and GST-TBP were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-E7 monoclonal antibodies (bottom), and GST protein inputs were visualized by staining the membrane with Ponceau stain (top). (d) Comparison of E2 and E7 derived from different HPV types. GST-tagged HPV-11 and -16 E2 proteins were incubated with in vitro-translated HPV-11 and -16 E7 proteins, respectively, and bound proteins assessed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Fifty percent of the total input protein is also shown, and the input GST fusion proteins are shown at the bottom. The asterisks denote full-length fusion proteins.

The in vitro interaction between E2 and E7 shown above might be direct or mediated through other, unknown, proteins present in the reticulocyte lysate or in the cell extracts. To investigate this, we performed a direct binding assay in which both proteins were expressed and purified from bacteria. Soluble, purified, His-tagged 16E7 was incubated with purified GST-16E2 immobilized on glutathione resin, as well as with GST-TBP as a positive control and GST alone as a negative control. After 1 h of incubation at 4°C, the resin was extensively washed and the amount of E7 retained was then detected by Western blotting with an anti-E7 monoclonal antibody. The results, shown in Fig. 2c, demonstrate that E7 binds E2 directly and that this interaction is comparable to the interaction between E7 and TBP. No interaction was seen between E7 and GST alone.

Having found that HPV-16E2 and HPV-16E7 could interact, we wanted to asses whether this was conserved between low- and high-risk HPV types. To do this, we assayed binding between the respective E2 and E7 proteins derived from HPV-11 and HPV-16. As can be seen in Fig. 2d, HPV-16 E7 binds HPV-16 E2 at a significantly higher level than that seen between HPV-11 E2 and E7, suggesting that the E2-E7 interaction is stronger for the high-risk HPV type.

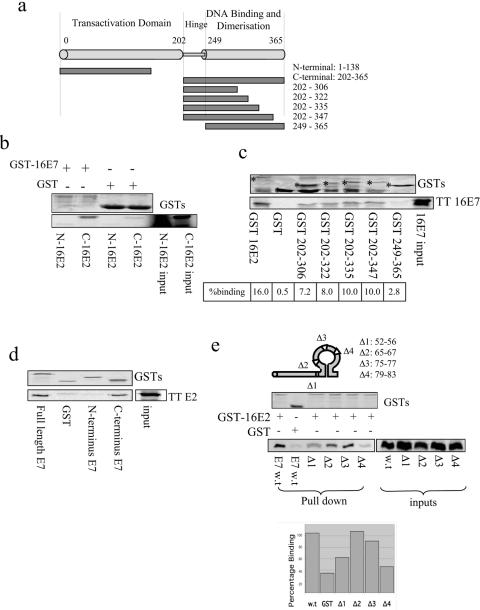

We then proceeded to map the sites of interaction between HPV-16 E2 and E7. The N- and C-terminal halves of E2 (as indicated in Fig. 3a) were first in vitro translated and incubated with GST-16E7 bound to resin. After extensive washing, the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Figure 3b shows that E7 binds preferentially to the C-terminal half of E2. To further map the site of interaction, a series of truncations along the C-terminal region of E2 fused to GST were purified and tested for the ability to bind in vitro-translated E7. As can be seen in Fig. 3c, E7 only interacts with those E2 proteins which retain an intact hinge region, thereby mapping the E7 site of interaction on E2 to a region spanning amino acid residues 202 to 249, although a role for additional amino acid residues extending to position 306 cannot be excluded.

FIG. 3.

Mapping of the sites of interaction between E2 and E7. (a) Scheme showing the E2 deletion mutant forms used in this study. (b) GST-16E7 was incubated with the N- and C-terminal halves of radiolabeled 16E2 in wheat germ extract. After extensive washing, bound proteins were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The 50% inputs of the N- and C-terminal halves of E2 are shown (bottom). Staining of the GST and GST-16E7 proteins is shown at the top. (c) Truncation mutant forms of 16E2 were produced as GST fusion proteins, bound to resin, and incubated with in vitro-translated 16E7, and bound proteins were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The 50% input of E7 (TT E7) is shown at the bottom, and the percentage of bound protein is also indicated. The staining of the GST fusion proteins is shown at the top, with asterisks marking the respective full-length fusion proteins. (d) The N- and C-terminal halves of 16E7 were expressed as GST fusion proteins and incubated with in vitro-translated 16E2. At the bottom is the pattern of bound protein, with TT E2 representing 50% of the input E2 protein. The upper part shows the staining of the GST fusion proteins. (e) Deletion mutant forms of E7 (as indicated in the upper scheme) were in vitro translated and incubated with GST-16E2. The staining of GST fusion proteins is shown in the upper gel. Bound proteins were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (lower left gel), and 50% inputs of the deletion mutant forms of E7 are also included (lower right gel). At the bottom is a bar chart of percent binding as calculated with a PhosphorImager as the mean of three independent assays. w.t, wild type.

We then performed a similar mutational analysis to map the site of interaction of E2 on the E7 protein. As can be seen in Fig. 3d, in vitro-translated E2 binds preferentially to the GST-tagged C-terminal half of E7. With a series of deletion mutant forms of E7 (31) translated in vitro, it can be seen that the E7 mutant lacking residues 79 to 83 (Δ4) is defective in the ability to bind GST-tagged E2 (Fig. 3e). In contrast, the other three mutant forms with changes within the zinc-binding domain of E7 still retain the ability to bind E2.

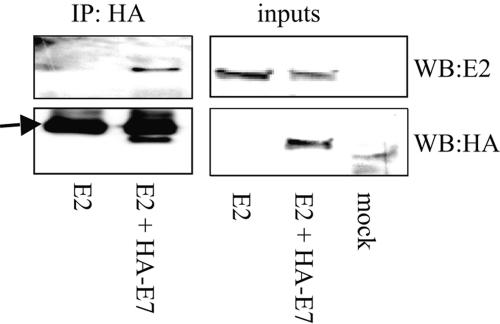

HPV-16 E2 and E7 interact in vivo.

Having shown that E2 and E7 can interact in vitro, we then proceeded to investigate whether we could detect the interaction in vivo. U2OS cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged 16E7 and untagged 16E2, and after 24 h cell extracts were incubated with anti-HA antibody cross-linked to agarose beads (Sigma). After extensive washing, the precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with a polyclonal antibody against 16E2 (32). As shown in Fig. 4, E2 coimmunoprecipitates with E7 but is not precipitated by the anti-HA antibody if E7 is absent. These results demonstrate that E2 and E7 can form a complex in vivo.

FIG. 4.

E2 and E7 interact in vivo. U2OS cell extracts expressing 16E2 alone or with HA-16E7 were incubated with anti-HA antibody linked to agarose beads, and the immunoprecipitated (IP) proteins were detected by Western blotting (WB) with anti-E2 or anti-HA antibody. Fifteen percent of each cell extract used for the precipitation was included as inputs. The arrow indicates the immunoglobulin G light chain.

HPV-16 E2 increases the stability of HPV-16 E7.

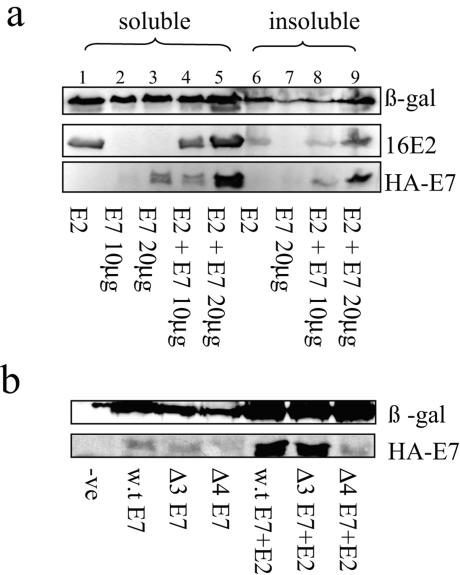

Upon the coexpression of E2 and E7 in U2OS cells, we consistently observed that E7 levels were increased in the presence of E2, compared with the expression of E7 alone. As shown in Fig. 5a (lanes 2, 3, and7), E7 is weakly detectable when expressed alone in either the soluble or the insoluble fraction of the cellular extract (see Materials and Methods), compared with the expression of β-gal, which was used as a marker of transfection efficiency. However, in the presence of E2 the levels of E7 increase markedly (Fig. 5a, lanes 4, 5, 8, and 9). To investigate whether this increase in the levels of E7 in the presence of E2 was due to the interaction between the two proteins, we repeated the assay but included two E7 mutant forms. The results obtained are shown in Fig. 5b, where it can be seen that the mutant form of E7 (Δ4) that is defective for E2 binding is unaffected by the presence of E2 while the Δ3 mutant form of E7, which retains E2-binding activity, is stabilized by E2 in a manner similar to that seen with wild-type E7.

FIG. 5.

16E7 protein levels are stabilized when 16 E7 is coexpressed with 16E2 in U2OS cells. (a) Different amounts of HA-tagged E7 were transfected with or without E2. Shown are Western blot assays of soluble and insoluble fractions of the cellular extracts expressing different combinations of E2 and E7 probed with polyclonal anti-E2 and monoclonal anti-HA antibodies. The expression of β-gal was used as a control for transfection efficiency. (b) Cells grown in six-well dishes were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-tagged 16E7 and the Δ3 and Δ4 mutant forms of HA-16E7 with or without E2. Total cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot assay with anti-HA or anti-β-gal antibody. -ve, negative; w.t, wild type.

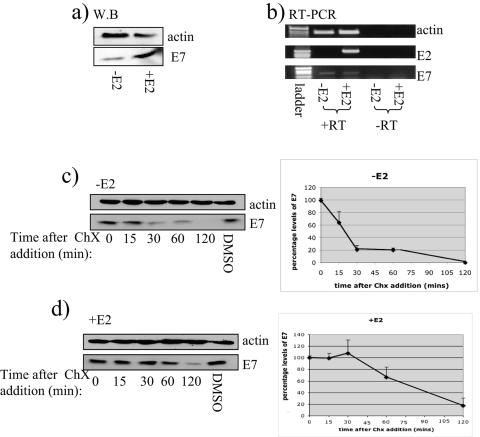

We were then interested in investigating the effects of E2 on E7 protein expressed endogenously in CaSKi cells. Therefore, CaSKi cells were transfected with E2 and the levels of E7 protein in a total cell extract were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against E7 and actin as a loading control. As demonstrated in Fig. 6a, the levels of E7 protein are markedly increased in the presence of E2. This is independent of E7's mRNA levels, as tested by RT-PCR on cells transfected in a parallel experiment (Fig. 6b). To test whether the increase in the levels of E7 was due to its increased stability, CaSKi cells were transfected with E2 and 24 h later cycloheximide was added to block protein synthesis. Cell extracts were then made at different time points and E7 expression analyzed by Western blotting. As can be seen in Fig. 6c, the levels of E7 by itself are significantly decreased between 15 and 30 min into the chase, compared with the levels of actin, which was used as a loading control for equal levels of cell extract. In contrast, in the presence of E2, the initial level of E7 is approximately twofold higher and this remains constant for much longer and can still be detected up to 2 h into the chase (Fig. 6d). Similar results were also obtained by transient transfection in U2OS cells, which again was independent of any effects on E7 gene expression (data not shown). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that E2 increases the stability of the E7 protein.

FIG. 6.

Increase in the stability and half-life of endogenous E7 in the presence of E2. CaSKi cells were plated at 8 × 104 per well in six-well dishes and transfected with 3 μg of an empty plasmid or a plasmid expressing 16E2. At 24 h later, the levels of E7 were analyzed in total cell extracts by Western blot (W.B) assay with monoclonal anti-E7 and anti-α-actin antibodies (a) or by RT-PCR with specific primers to amplify E2, E7, and actin (b). Controls without RT (-RT) were included as a control for RNA purity. (c and d) CaSKi cells transfected with an empty plasmid (c) or a plasmid expressing 16E2 (d) were treated at different times with cycloheximide (ChX) in DMSO or with DMSO alone for 120 min. Cells were harvested at different times (0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min) after cycloheximide treatment, and the levels of E7 protein were analyzed by Western blot assay with a monoclonal antibody against 16E7 or α-actin. The intensities of the bands were measured with Adobe Photoshop, and the mean results from three independent experiments are shown together with standard deviations (c and d, right side).

E7 colocalizes with E2 on mitotic chromosomes.

Having shown that E2 binds and stabilizes the E7 protein (Fig. 5 and 6) but at the same time inhibits its transforming activity (Fig. 1), we were next interested in investigating the potential effects of E7 upon E2 function. To do this, we analyzed the effects of E7 upon E2 transcriptional activity and upon the ability of E2 to bind DNA. In both cases, no significant effects were observed (data not shown).

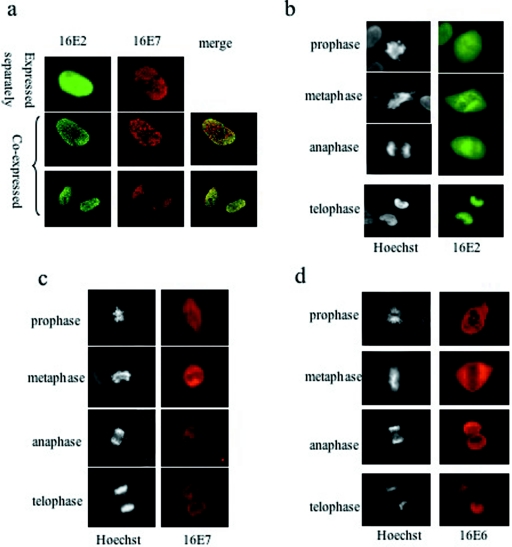

A recently described novel function of the E2 protein involves binding to mitotic chromosomes, which is thought to be important for the segregation of viral genomes into daughter cells. This activity of E2 has mainly been studied with the E2 protein derived from bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1), which was shown to require binding to the cellular protein Brd-4 in mitotic cells (60). Prior to investigating the potential effects of E7 upon E2 localization during mitosis, we first sought to examine whether HPV-16 E2 could bind to mitotic chromosomes similarly to what has been reported for BPV E2. To do this, E2 was overexpressed in U2OS cells and 48 h later the cells were fixed and E2 was detected with a polyclonal antibody against HPV-16 E2. The cells were also stained with Hoechst stain to visualize cellular chromosomes. The cells were not synchronized by drug treatment, and visualization of the chromosomal patterns was used to determine the stage of mitosis (48) in which the cells were fixed. As can be seen in Fig. 7a, HPV-16 E2 shows diffused nuclear staining in interphase cells and during the initial stages of mitosis it is excluded from condensed chromosomes (Fig. 7b). As the cell enters telophase, E2 localizes to mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 7b, bottom).

FIG. 7.

Localization of E2, E7, and E6 in U2OS cells. U2OS cells grown on coverslips in six-well dishes were transfected with plasmids expressing 16E2 and/or HA-tagged 16E7 and 16E6. At 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed and probed with rabbit anti-E2 and mouse anti-HA antibodies, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (green, for E2) and rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse (red, for E7 and E6) antibodies. The slides were scanned with a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope. (a) Interphase U2OS cells were visualized for separate expression or coexpression of the E2 and E7 proteins. Localization of 16E2 (b), 16E7 (c), and 16E6 (d) at different stages of mitosis is shown. Chromosomes were visualized with Hoechst stain.

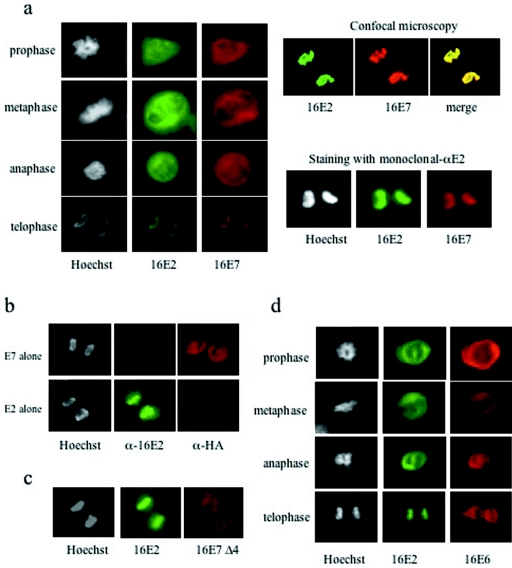

Since both E6 and E7 are known to induce chromosomal segregation defects (19), we were then interested to see whether they exert these effects by binding directly to the chromosomal arms. Neither E7 nor E6, when transfected alone, was detected on mitotic chromosomes in any of the stages of mitosis; instead, they showed diffuse staining and chromosomal exclusion (Fig. 7c and d). However, when E7 was coexpressed with E2 it could clearly be detected on mitotic chromosomes together with E2 at telophase (Fig. 8a, bottom). The colocalization of E2 and E7 was also confirmed by scanning confocal microscopy (Fig. 8a, upper right part). As an additional control, E2 was also detected with a previously described monoclonal antibody (27) together with a rabbit anti-HA antibody to detect E7 (Fig. 8a, lower right part), and a similar pattern of expression was observed. To further verify the specificity of the antibodies used in the fluorescence experiments, telophase cells expressing either E2 or HA-tagged E7 alone were also stained with both rabbit anti-E2 and mouse anti-HA antibodies. Figure 8b shows that in the absence of the antibody-specific protein, very low background staining was obtained, indicating no cross-reaction between the different antibodies and proteins. To verify that E2-induced relocalization of E7 onto chromosomes was dependent upon the association between E2 and E7, we repeated the assay with the Δ4 mutant form of E7 which cannot bind to E2. As can be seen in Fig. 8c, E2 shows clear costaining with the chromosomes while the E7 Δ4 mutant form does not. Finally, the specificity of the relocalization was further confirmed by the inclusion of HA-tagged 16E6, which was previously shown to interact with E2 (25) and where no E2-induced alteration of the pattern of E6 expression was seen during mitosis (Fig. 8d). These results demonstrate a specific relocalization of the E7 protein onto mitotic chromosomes as a direct result of its interaction with E2 during telophase.

FIG. 8.

E2 recruits E7 to mitotic chromosomes at telophase. U2OS cells were processed as described for Fig. 7. (a) Coexpression of E2 and E7 at different stages of mitosis. Telophase cells were scanned by confocal microscopy (upper right), where E2 is green, E7 is red, and the merged image shows clear confocality. The same assay was also done with anti-E2 monoclonal antibodies (mono-αE2) together with rabbit anti-HA antibodies to detect E7 (lower right). (b) The specificity of the antibodies used in panel a (left) was verified by staining telophase cells expressing either HA-tagged E7 alone (top) or E2 alone (bottom) with both rabbit anti-E2 and mouse anti-HA antibodies. (c) Localization of E2 and the E7 Δ4 deletion mutant form during telophase. Note the chromosomal localization of E2 but chromosomal exclusion of the E7 mutant form. (d) Localization of HA-tagged 16E6 protein coexpressed with E2 throughout mitosis, showing no recruitment of E6 onto mitotic chromosomes.

DISCUSSION

Unlike lytic viruses, HPVs can replicate their DNA and release infectious virions without resulting in cellular death or transformation. The virus initially infects the basal layer of the epithelium, and production of mature virions is only observed in the upper granular layer (29). With respect to the papillomavirus life cycle, cellular immortalization and viral genome integration are both disadvantageous for the virus; the replicative capacity of the virus is lost with the loss of the E2 protein, and immortalized cells are unable to differentiate into the stratum corneum, where mature virions are formed and shed. Therefore, to ensure an efficient and reproductive life cycle, HPVs finely modulate the activities of cellular proteins and their own viral gene products through various interactions.

Several studies have shown the regulation of expression of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 by the E2 protein (14, 24). In this study, we have identified a direct interplay between the HPV-16 E2 and E7 proteins. Initially, we observed E2 inhibition E7's growth-promoting function in the absence of any E2-mediated transcriptional modulation (Fig. 1). This result provides evidence of a transcription-independent ability of E2 to counteract the activity of the viral oncoprotein. This is in agreement with previously published data showing that both HPV-16 and -18 E2 proteins can induce apoptosis in HPV-positive cell lines in the absence of their DNA-binding domains (11, 58). In addition, it has been previously shown that mutations in the E2-binding sites proximal to the p97 promoter do not fully alleviate E2-mediated repression of HPV-16-induced immortalization of primary human keratinocytes (43). By providing evidence of a direct interaction between E2 and E7, both in vivo and in vitro, we propose a novel mechanism by which E2 interferes with the oncogenicity of E7. The transforming activity of E7 depends on its interference with the activity of cell cycle regulatory proteins. Although binding to and disrupting the function of pRB are considered to be the major activities of E7, many studies have shown that this binding is dispensable in some E7-induced phenotypes and is insufficient for E7-induced transformation (3, 18, 50). In vitro binding assays showed that E2 binds directly to the C-terminal half of E7 at a region where several cellular targets of E7 bind, such as TBP (31), the Mi2β-NURD histone deacetylase complex (7), and the AP1 transcription factor (2). This suggests that the binding of E2 to E7 might compete with the binding of E7 to some of its cellular targets and thus inhibits its activity. Another mechanism by which E2 could repress the activity of E7 could be by reducing the cellular levels of the E7 protein. However, our data do not support this hypothesis. The cellular levels of E7, both endogenous and overexpressed, were markedly stabilized by the addition of E2. Although E2 can act as both a transcriptional activator and a repressor in a concentration-dependent manner (51), we excluded the role of E2's transcriptional activity in increasing the levels of E7 for the following reasons. First, E7's levels were stabilized by E2 even in the absence of an E2-binding site on the E7 promoter when both proteins were overexpressed in U2OS cells. Second, in the CaSKi cell line, which contains the LCR, the half-life of E7 was increased, independently of the HPV mRNA levels at the specific concentrations used in this study. Finally, the levels of the Δ4 mutant form of E7, which is defective in binding E2, were not changed upon the introduction of E2, thus providing further evidence that the stability of E7 is increased due to direct protein-protein interaction between E2 and E7. Since E7 has been shown to be ubiquitinated and cleaved by the SCF-ubiquitin ligase complex (37), it will be interesting to investigate whether E2 perturbs this activity.

In this study, we observed both a repression of E7's transforming activity and an increase in its stability in the presence of E2; we were then interested in seeing whether E7 might interfere with the functions of E2. While we saw no effects on E2-mediated transcriptional activation or DNA-binding activity, we found intriguing colocalization of E7 with E2 on mitotic chromosomes. The first suggestion that a papillomavirus-encoded protein can associate with mitotic chromosomes came from a study of BPV E2 (49). BPV-1 E2 was shown to bind to the bromodomain-containing protein Brd4 (60), which attaches to acetylated chromatin during interphase and mitosis (12). Although BPV and HPV E2 proteins display identical DNA sequence specificities and similar functions, they vary in some of their characteristics (5, 28). Here, we have found that E2 from HPV-16 also possesses a chromosome-binding phenotype but, unlike BPV-1 E2, binds chromosomes only at late stages of mitosis. Therefore, we anticipate that 16E2 may use an alternative method to that used by BPV-1 E2 to localize to and bind mitotic chromosomes. Previously, HPV E2 was shown to be excluded from metaphase chromosomes (57). Here we confirm the exclusion of 16E2 from mitotic chromosomes in metaphase; however, in contrast to that study (57), we did not observe a pattern of HPV-16 E2 expression that indicates its localization to mitotic spindles or centrosomes. This difference might be due to the use of different cell lines, different E2 expression constructs, and different detection and fixation procedures. Further studies are required to clarify these issues.

Most interestingly, we observed that 16E2 relocalizes E7, but not E6, to mitotic chromosomes at telophase. This suggests that the relocalization of E7 by E2 is a highly specific event. This was further borne out by the use of an E7 mutant form that fails to bind E2, which likewise also failed to colocalize with E2 on mitotic chromosomes. We cannot exclude the possibility that this E7 mutant form has other properties which preclude E2 stabilization and recruitment to chromosomes, and future studies will aim to clarify this by using E2 mutant forms that are defective for binding to E7. The biological function of this specific localization is also still unidentified, and it remains to be determined whether E2 alters E7's patterns of expression in the context of a normal viral life cycle. Studies are in progress to investigate this in raft culture models of HPV infection. However, these studies are particularly intriguing when one considers the effects of E6 and E7 upon mitosis, where both have been shown to separately induce mitotic abnormalities when stably expressed in cultured cell lines or cells derived from transgenic mice (17, 38, 45). Further dissection of the role of each protein showed that when each protein is transiently expressed, only E7 results in immediate chromosomal abnormalities (15, 16). This suggests that E7 has a direct effect in inducing centrosomal abnormalities, while the effects induced by E6 might be an indirect consequence of the abrogation of p53 function. Provided with the direct role of E7 in interfering with the mitotic machinery, the tethering of E7 to mitotic chromosomes may be required to directly inhibit cellular checkpoint proteins that might be activated in response to the detection of E2 on mitotic chromosomes, thus avoiding cell cycle arrest in mitosis. Another possible function would be to segregate E7 itself and thus ensure that appropriate amounts of the protein will be present in newly divided daughter cells. E7 might also be required to stabilize the binding of E2 to the viral episomes or mitotic DNA during cell division, and current studies are aimed toward assessing the effects of E7 upon E2 during exit from mitosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro.

We are grateful to Merilyn Hibma for kindly providing the anti-E2 monoclonal antibody, to Miranda Thomas and David Pim for comments on the manuscript, and to Daniela Gardiol for help with experimental work and manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Androphy, E. J., D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1987. Bovine papillomavirus E2 trans-activating gene product binds to specific sites in papillomavirus DNA. Nature 325:70-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antinore, M. J., M. J. Birrer, D. Patel, L. Nader, and D. J. McCance. 1996. The human papillomavirus type 16 E7 gene product interacts with and trans-activates the AP1 family of transcription factors. EMBO J. 15:1950-1960. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balsitis, S. J., J. Sage, S. Duensing, K. Munger, T. Jacks, and P. F. Lambert. 2003. Recapitulation of the effects of the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncogene on mouse epithelium by somatic Rb deletion and detection of pRb-independent effects of E7 in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:9094-9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bechtold, V., P. Beard, and K. Raj. 2003. Human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein has no effect on transcription from episomal viral DNA. J. Virol. 77:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvard, V., A. Storey, D. Pim, and L. Banks. 1994. Characterization of the human papillomavirus E2 protein: evidence of trans-activation and trans-repression in cervical keratinocytes. EMBO J. 13:5451-5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer, S. N., D. E. Wazer, and V. Band. 1996. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 56:4620-4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brehm, A., S. J. Nielsen, E. A. Miska, D. J. McCance, J. L. Reid, A. J. Bannister, and T. Kouzarides. 1999. The E7 oncoprotein associates with Mi2 and histone deacetylase activity to promote cell growth. EMBO J. 18:2449-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chellappan, S., V. B. Kraus, B. Kroger, K. Munger, P. M. Howley, W. C. Phelps, and J. R. Nevins. 1992. Adenovirus E1A, simian virus 40 tumor antigen, and human papillomavirus E7 protein share the capacity to disrupt the interaction between transcription factor E2F and the retinoblastoma gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4549-4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, S., D. C. Schmidt-Grimminger, T. Murant, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1995. Differentiation-dependent up-regulation of the human papillomavirus E7 gene reactivates cellular DNA replication in suprabasal differentiated keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 9:2335-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corden, S. A., L. J. Sant-Cassia, A. J. Easton, and A. G. Morris. 1999. The integration of HPV-18 DNA in cervical carcinoma. Mol. Pathol. 52:275-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demeret, C., A. Garcia-Carranca, and F. Thierry. 2003. Transcription-independent triggering of the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis by human papillomavirus 18 E2 protein. Oncogene 22:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dey, A., F. Chitsaz, A. Abbasi, T. Misteli, and K. Ozato. 2003. The double bromodomain protein Brd4 binds to acetylated chromatin during interphase and mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8758-8763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doorbar, J. 2005. The papillomavirus life cycle. J. Clin. Virol. 32(Suppl. 1):S7-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowhanick, J. J., A. A. McBride, and P. M. Howley. 1995. Suppression of cellular proliferation by the papillomavirus E2 protein. J. Virol. 69:7791-7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duensing, S., A. Duensing, C. P. Crum, and K. Munger. 2001. Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein-induced abnormal centrosome synthesis is an early event in the evolving malignant phenotype. Cancer Res. 61:2356-2360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duensing, S., L. Y. Lee, A. Duensing, J. Basile, S. Piboonniyom, S. Gonzalez, C. P. Crum, and K. Munger. 2000. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins cooperate to induce mitotic defects and genomic instability by uncoupling centrosome duplication from the cell division cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10002-10007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duensing, S., and K. Munger. 2002. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins independently induce numerical and structural chromosome instability. Cancer Res. 62:7075-7082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duensing, S., and K. Munger. 2003. Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein can induce abnormal centrosome duplication through a mechanism independent of inactivation of retinoblastoma protein family members. J. Virol. 77:12331-12335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duensing, S., and K. Munger. 2004. Mechanisms of genomic instability in human cancer: insights from studies with human papillomavirus oncoproteins. Int. J. Cancer 109:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyson, N., P. M. Howley, K. Munger, and E. Harlow. 1989. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 243:934-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enemark, E. J., G. Chen, D. E. Vaughn, A. Stenlund, and L. Joshua-Tor. 2000. Crystal structure of the DNA binding domain of the replication initiation protein E1 from papillomavirus. Mol. Cell 6:149-158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis, D. A., S. I. Schmid, and P. M. Howley. 2000. Repression of the integrated papillomavirus E6/E7 promoter is required for growth suppression of cervical cancer cells. J. Virol. 74:2679-2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funk, J. O., S. Waga, J. B. Harry, E. Espling, B. Stillman, and D. A. Galloway. 1997. Inhibition of CDK activity and PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21 is blocked by interaction with the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 11:2090-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin, E. C., and D. DiMaio. 2000. Repression of human papillomavirus oncogenes in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells causes the orderly reactivation of dormant tumor suppressor pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12513-12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grm, H. S., P. Massimi, N. Gammoh, and L. Banks. 2005. Crosstalk between the human papillomavirus E2 transcriptional activator and the E6 oncoprotein. Oncogene 24:5149-5164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helt, A. M., and D. A. Galloway. 2001. Destabilization of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 is not sufficient to overcome cell cycle arrest in human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 75:6737-6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibma, M. H., K. Raj, S. J. Ely, M. Stanley, and L. Crawford. 1995. The interaction between human papillomavirus type 16 E1 and E2 proteins is blocked by an antibody to the N-terminal region of E2. Eur. J. Biochem. 229:517-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hines, C. S., C. Meghoo, S. Shetty, M. Biburger, M. Brenowitz, and R. S. Hegde. 1998. DNA structure and flexibility in the sequence-specific binding of papillomavirus E2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 276:809-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howley, P. M., and D. R. Lowy. 2001. Virology, vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 30.Mantovani, F., and L. Banks. 2001. The human papillomavirus E6 protein and its contribution to malignant progression. Oncogene 20:7874-7887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massimi, P., D. Pim, and L. Banks. 1997. Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 binds to the conserved carboxy-terminal region of the TATA box binding protein and this contributes to E7 transforming activity. J. Gen. Virol. 78(Pt. 10):2607-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massimi, P., D. Pim, C. Bertoli, V. Bouvard, and L. Banks. 1999. Interaction between the HPV-16 E2 transcriptional activator and p53. Oncogene 18:7748-7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massimi, P., D. Pim, A. Storey, and L. Banks. 1996. HPV-16 E7 and adenovirus E1a complex formation with TATA box binding protein is enhanced by casein kinase II phosphorylation. Oncogene 12:2325-2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matlashewski, G., J. Schneider, L. Banks, N. Jones, A. Murray, and L. Crawford. 1987. Human papillomavirus type 16 DNA cooperates with activated ras in transforming primary cells. EMBO J. 6:1741-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzarelli, J. M., G. B. Atkins, J. V. Geisberg, and R. P. Ricciardi. 1995. The viral oncoproteins Ad5 E1A, HPV16 E7 and SV40 TAg bind a common region of the TBP-associated factor-110. Oncogene 11:1859-1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimura, A., T. Ono, A. Ishimoto, J. J. Dowhanick, M. A. Frizzell, P. M. Howley, and H. Sakai. 2000. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus E2-mediated repression of viral oncogene expression and cervical cancer cell growth inhibition. J. Virol. 74:3752-3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh, K.-J., A. Kalinina, J. Wang, K. Nakayama, K. I. Nakayama, and S. Bagchi. 2004. The papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein is ubiquitinated by UbcH7 and Cullin 1- and Skp2-containing E3 ligase. J. Virol. 78:5338-5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel, D., A. Incassati, N. Wang, and D. J. McCance. 2004. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 cause polyploidy in human keratinocytes and up-regulation of G2-M-phase proteins. Cancer Res. 64:1299-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piccini, A., A. Storey, P. Massimi, and L. Banks. 1995. Mutations in the human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein identify multiple regions of the protein involved in binding to E1. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Pt. 11):2909-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prathapam, T., C. Kuhne, and L. Banks. 2001. The HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein binds Skip and suppresses its transcriptional activity. Oncogene 20:7677-7685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riley, R. R., S. Duensing, T. Brake, K. Munger, P. F. Lambert, and J. M. Arbeit. 2003. Dissection of human papillomavirus E6 and E7 function in transgenic mouse models of cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 63:4862-4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rohlfs, M., S. Winkenbach, S. Meyer, T. Rupp, and M. Durst. 1991. Viral transcription in human keratinocyte cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus type-16. Virology 183:331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romanczuk, H., and P. M. Howley. 1992. Disruption of either the E1 or the E2 regulatory gene of human papillomavirus type 16 increases viral immortalization capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3159-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sang, B. C., and M. S. Barbosa. 1992. Increased E6/E7 transcription in HPV 18-immortalized human keratinocytes results from inactivation of E2 and additional cellular events. Virology 189:448-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schaeffer, A. J., M. Nguyen, A. Liem, D. Lee, C. Montagna, P. F. Lambert, T. Ried, and M. J. Difilippantonio. 2004. E6 and E7 oncoproteins induce distinct patterns of chromosomal aneuploidy in skin tumors from transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 64:538-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheffner, M., B. A. Werness, J. M. Huibregtse, A. J. Levine, and P. M. Howley. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider, J. F., F. Fisher, C. R. Goding, and N. C. Jones. 1987. Mutational analysis of the adenovirus E1a gene: the role of transcriptional regulation in transformation. EMBO J. 6:2053-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scholey, J. M., I. Brust-Mascher, and A. Mogilner. 2003. Cell division. Nature 422:746-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skiadopoulos, M. H., and A. A. McBride. 1998. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 genomes and the E2 transactivator protein are closely associated with mitotic chromatin. J. Virol. 72:2079-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Southern, S. A., M. H. Lewis, and C. S. Herrington. 2004. Induction of tetrasomy by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein is independent of pRb binding and disruption of differentiation. Br. J. Cancer 90:1949-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steger, G., and S. Corbach. 1997. Dose-dependent regulation of the early promoter of human papillomavirus type 18 by the viral E2 protein. J. Virol. 71:50-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Storey, A., and L. Banks. 1993. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene cooperates with EJ-ras to immortalize primary mouse cells. Oncogene 8:919-924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Storey, A., A. Piccini, P. Massimi, V. Bouvard, and L. Banks. 1995. Mutations in the human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein identify a region of the protein involved in binding to E1 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Pt 4):819-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Storey, A., D. Pim, A. Murray, K. Osborn, L. Banks, and L. Crawford. 1988. Comparison of the in vitro transforming activities of human papillomavirus types. EMBO J. 7:1815-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thierry, F., and P. M. Howley. 1991. Functional analysis of E2-mediated repression of the HPV18 P105 promoter. New Biol. 3:90-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas, M., P. Massimi, and L. Banks. 1996. HPV-18 E6 inhibits p53 DNA binding activity regardless of the oligomeric state of p53 or the exact p53 recognition sequence. Oncogene 13:471-480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Tine, B. A., L. D. Dao, S. Y. Wu, T. M. Sonbuchner, B. Y. Lin, N. Zou, C. M. Chiang, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 2004. Human papillomavirus (HPV) origin-binding protein associates with mitotic spindles to enable viral DNA partitioning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4030-4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webster, K., J. Parish, M. Pandya, P. L. Stern, A. R. Clarke, and K. Gaston. 2000. The human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 E2 protein induces apoptosis in the absence of other HPV proteins and via a p53-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 275:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshinouchi, M., T. Yamada, M. Kizaki, J. Fen, T. Koseki, Y. Ikeda, T. Nishihara, and K. Yamato. 2003. In vitro and in vivo growth suppression of human papillomavirus 16-positive cervical cancer cells by E6 siRNA. Mol. Ther. 8:762-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.You, J., J. L. Croyle, A. Nishimura, K. Ozato, and P. M. Howley. 2004. Interaction of the bovine papillomavirus E2 protein with Brd4 tethers the viral DNA to host mitotic chromosomes. Cell 117:349-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.zur Hausen, H. 1986. Intracellular surveillance of persisting viral infections. Human genital cancer results from deficient cellular control of papillomavirus gene expression. Lancet ii:489-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]