Abstract

Vaccination by the nasal route has been successfully used for the induction of immune responses. Either the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT), the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue, or lung dendritic cells have been mainly involved. Following nasal vaccination of mice with human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) virus-like-particles (VLPs), we have previously shown that interaction of the antigen with the lower respiratory tract was necessary to induce high titers of neutralizing antibodies in genital secretions. However, following a parenteral priming, nasal vaccination with HPV16 VLPs did not require interaction with the lung to induce a mucosal immune response. To evaluate the contribution of the upper and lower respiratory tissues and associated lymph nodes (LN) in the induction of humoral responses against HPV16 VLPs after nasal vaccination, we localized the immune inductive sites and identified the antigen-presenting cells involved using a specific CD4+ T-cell hybridoma. Our results show that the trachea, the lung, and the tracheobronchial LN were the major sites responsible for the induction of the immune response against HPV16 VLP, while the NALT only played a minor role. Altogether, our data suggest that vaccination strategies aiming to induce efficient immune responses against HPV16 VLP in the female genital tract should target the lower respiratory tract.

Systemic and mucosal antibodies have been successfully induced following nasal vaccination using live vectors (32, 42, 44, 45), soluble proteins together with cholera toxin (48, 49), or microparticle-delivered antigens (20). Moreover, nasal vaccination has been the most effective method for inducing specific immunity in the genital tract (4, 12, 13, 15, 23, 34, 35, 40, 43). The inductive sites, where the immune response is mounted after nasal vaccination, remain so far unclear, but their identification is important for the design of efficient protocols for human vaccination. The nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) is a potential site from which both soluble and particulate antigens can be sampled following nasal administration (reviewed in references 1, 28, and 50). In humans the NALT is absent, but tissue equivalents are formed by the so-called Waldeyer's ring (tonsils, adenoids etc.) (6, 7). Following nasal vaccination, inhaled antigen may also come in contact with other mucosal surfaces, such as the trachea and the lung, where dendritic cells (DC) have been shown to take up antigen and migrate to draining lymph nodes (21, 51). Furthermore, in the lower respiratory tract, the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) (5) and the larynx-associated lymphoid tissue (26) have also been implicated (16). We have been particularly interested in the design of mucosal vaccination strategies against human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16), which is etiologically linked to more than 50% of cervical cancer (47). Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide, encouraging the development of a vaccine to prevent infection by these viruses. Recently we have shown that nasal vaccination of anesthetized mice with purified HPV16 virus-like-particles (VLPs) induced high levels of HPV16-neutralizing immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin A in genital secretions (4). Interaction of the antigen with the lung played a predominant role in the efficient induction of these antibodies, although interaction of the VLPs with the NALT was sufficient to induce a mucosal response after parenteral priming. In order to evaluate the respective roles of the upper and lower respiratory tracts in the induction of a specific genital immune response after nasal vaccination, in the present study we localized the sites of uptake and/or presentation of the HPV16 VLP and defined the cell types involved. For this purpose, we constructed a CD4+-T-cell hybridoma (HD9L1) specific for HPV16 L1, the major component of the VLP. HPV16 VLP presentation was examined in different tissues of the upper and lower respiratory tracts and in the corresponding draining LN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

BW5147 thymoma (H-2K α− β− HGPRT−), CTLL-2 cells, EL-4 cells, and 31.1.1 (anti-CD8), RL-172 (anti-CD4) (9), and AT83 (anti-Thy-1) (41) hybridomas were a gift from the Ludwig Institute, Lausanne Branch, Lausanne, Switzerland. The M5/114.15.2 (I-Abdq I-Edk) and GL1 (CD86) antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). BW5147 thymoma cells, 31.1.1, RL-172, and AT83 hybridomas, and CTLL-2 cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin/ml, 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) (all from Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and 20 μM (or 50 μM for CTLL-2) 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Five units of interleukin 2 (IL-2)/ml was added to the CTLL-2 cell medium. IL-2 was obtained from the supernatant of EL-4 cells stimulated with 10 ng of phorbol myristate acetate (Sigma)/ml. The hybridoma (HD9L1) was maintained in complete medium (cRPMI: RPMI 1640; Seromed, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin/ml, 0.1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% FCS (Life Technologies), 20 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 1× hypoxanthine thymidine (Life Technologies).

Antigen.

HPV16 L1/L2 VLPs were prepared from insect cells infected with a recombinant baculovirus expressing HPV16 L1 and L2 as described previously (27, 34). L1/L2 polypeptides and bovine serum albumin (BSA) polypeptides were obtained by chemical cleavage of HPV16 L1/L2 VLP or BSA with cyanogen bromide. HPV16 L1 VLPs were a gift from J. Schiller, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Md.). Bacterial HPV16 L1 antigen was prepared from the recombinant Escherichia coli χ6097 pYA3342L1, stably expressing HPV16 L1 from the constitutive trc promoter (38). Fifty milliliters of an overnight culture of the recombinant bacteria was centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Protease inhibitors (1:500 dilution of a stock containing 5 mg of pepstatin, 5 mg of leupeptin, 5 mg of antipain, and 25 mg of benzamidin per ml of dimethyl sulfoxide [Sigma]) were added to the bacterial suspension, which then was sonicated on ice. After centrifugation, the supernatant was used as source of L1 antigen.

Mice and immunization.

Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice (Iffa Credo, Arbresles, France) were used in all experiments. For nasal vaccination, anesthetized mice were immunized with 5 μg of HPV16 VLP diluted with PBS- 0.5 M NaCl to a final inoculum volume of 20 μl as described previously (4, 23). Subcutaneous immunization was performed by injecting 1 μg of HPV16 VLPs diluted in 20 μl of PBS into the hind footpad.

Construction of an HPV16-L1-specific T-cell hybridoma.

The spleen was taken from a mouse that received three 5-μg nasal doses of HPV16 VLP at weeks 0, 1, and 2 and then boosted subcutaneously 3 months later with 1 μg of HPV16 VLP. The mouse was sacrificed 2 weeks after the booster. Cells were prepared by mechanical dissociation (see below), and L1/L2 polypeptides were added to stimulate activated T cells in cRPMI. Three days later 200 U of IL-2/ml was added for 1 week. Cells (12 × 106) were then fused at a ratio of 1:2 with the BW5147 thymoma line as described previously (25). Ninety-nine growing hybrids resulted from the fusion between HPV16 VLP-activated splenic T cells and the BW5147 fusion partner. Among these 99 growing hybrids, 61 were HPV16 VLP specific. Antigen specificity of growing hybrids was tested by incubating 105 cells of each hybrid for 24 h with 2 × 105 irradiated naive splenic feeder cells loaded with 2 μg of L1/L2-polypeptides/ml in 150 μl of cRPMI. Antigen-dependent production of IL-2 was measured as described below. Antigen sensitivity of the growing hybrids was tested by incubating 105 cells of each hybrid for 24 h with 2 × 105 irradiated naive splenic feeder cells loaded with 1 μg of L1/L2-polypeptides/ml or 9 μg of L1/L2 polypeptides/ml in 150 μl of total antigen presentation assay medium. The clone which produced the highest amount of IL-2 was amplified and designed HD9L1.

Antigen presentation assays.

Antigen presentation assays were performed in cRPMI. The L1 antigen-presenting activity of antigen-presenting cells (APC) was assessed by using the HD9L1 hybridoma. Cells isolated from immunized mice or loaded in vitro with antigen were prepared as described below. Up to 3 × 105 APC were incubated in duplicate with 105 HD9L1 in a final volume of 150 μl for 24 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a 96-well microtiter plate. IL-2 production was measured as described below. Threshold activation of HD9L1 was defined as the mean background of CTLL-2 proliferation plus three times the standard deviation (SD). Activity of presentation was expressed in units as the reciprocal minimal number of cells necessary to activate HD9L1 × 106. The level of detection was between 33 and 5 U depending on the maximal number of cells that could be tested from each organ/tissue (30,000 to 200,000).

IL-2 measurement.

In each experiment, measurement of IL-2 was performed by transferring 50 μl of the culture supernatant into a new microtiter plate and adding 6,000 CTLL-2 cells in 50 μl of cRPMI. After 24 h of incubation, 0.5 μCi of tritiated thymidine was added in each well and plates were further incubated for at least 8 h. Cells were harvested on a Unifilter plate (Packard Instruments, Groningen, The Netherlands), and incorporated tritiated thymidine was measured with a beta counter (Topcount, Packard Instruments).

Cell suspensions.

Total immune cells were prepared from organs by mechanical dissociation or collagenase D (Boehringer, Manheim, Germany) digestion followed by T-cell depletion. For mechanical dissociation, organs were squashed on a 70-μm-pore-size nylon filter (Falcon, BD, Franklin Lakes, N.J.), and cells were collected into a 50-ml conical tube by rinsing the filter with 15 ml of cRPMI containing 2% FCS (cRPMI 2%). Cell suspensions were washed twice and filtered again through a 40-μm-pore-size nylon filter (Falcon). For collagenase D digestion, LN or lymphoid tissues were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in cRPMI without 2-mercaptoethanol but containing 1 mg of collagenase D (Sigma)/ml. Cell suspensions were then filtered through a 50-μM-pore-size filter set on a serum cushion (5 ml of serum for 5 ml of cell suspension). After centrifugation for 15 min at 400 × g, total cells were washed three times in cRPMI-2% FCS. For erythrocyte lysis, cells were incubated for 5 min in 5 ml of lysing buffer (pH 7.2) (NH4Cl [0.15 M], KHC03 [1 mM], Na2EDTA [0.1 mM]) and washed three times in 2% cRPMI. T cells were depleted by incubating total cells with 250 μl of supernatant of anti-CD4 (RL172-4) and anti-CD8 (31.1.1) hybridomas and 500 μl of supernatant of anti-Thy-1 (AT83) hybridoma (15 min) on ice. Four milliliters of cRPMI-2% FCS and rabbit complement (Saxon Europe, Suffolk, United Kingdom) to a final concentration of 1/20 were added. Cells were further incubated for 1 h at 37°C on a wheel and washed three times with RPMI-2% FCS.

Purification by MACS.

Cells prepared from T-cell-depleted organs were incubated with anti-B220-coated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany) in magnetic antibody cell sorting (MACS) buffer (0.5% BSA-2 mM EDTA in PBS) and separated by positive selection on MACS MS+ columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). The positive fraction was used as a source of B-cell APC, and the flow-through (FT) fraction was used as a source of non-B-cell APC. For popliteal LN (PLN), the T-depleted cells were sorted in a DC cell fraction by using anti-CD11c-coated microbeads and in a B-cell fraction by using anti-B220-coated microbeads.

Preparation of BMDC.

bone marrow DCs (BMDC) were prepared as described previously (29). Briefly, bone marrow was collected from tibias and femurs of female BALB/c mice. Cells were incubated in BMDC medium (RPMI 1640 glutamax, 5% FCS, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 20-μg/ml gentamicin [Life Technologies], 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol [Sigma]) and passed through a 70-μm-pore-size filter (Falcon). Cells were resuspended in BMDC medium and incubated in culture dishes (Nunclone, Life Technologies) for 2 h. Nonadherent cells were collected and placed in 24-well plates (Nunclone, Life Technologies) at a concentration of 106 cells/well in BMDC medium supplemented with 150 U of murine recombinant granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rGM-CSF) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.)/ml. On day 3, two-thirds of the medium was replaced. On days 5 and 7, nonadherent cells were collected and incubated in 3-cm-diameter culture dishes (Nunclone; 2 × 106 cells/2 ml of BMDC medium supplemented with 150 U of rmGM-CSF/ml). On day 9, nonadherent cells were used as a source of BMDC in subsequent experiments.

RESULTS

Cloning of the L1-specific T-cell hybridoma HD9L1.

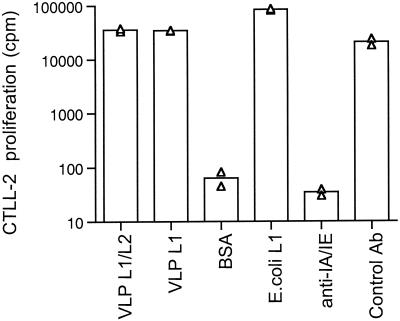

To better characterize the immune-inductive sites involved by nasal vaccination, we constructed an L1-specific CD4+-T-cell hybridoma able to detect L1-presenting cells in mice. To assess the specificity of HD9L1 for the L1 protein of HPV16, two other sources of the L1 protein were tested, i.e., purified HPV16 VLPs exclusively composed of the protein L1 or a sonicate of recombinant bacteria expressing L1 (χ6097 pYA3342L1) (38). Cyanogen bromide-digested BSA (BSA polypeptides) was used as an unrelated antigen. Only L1-containing antigens, regardless of their origin, can activate HD9L1 (Fig. 1), demonstrating that it was specific to the L1 protein. Moreover, the L1-induced activation of HD9L1 was prevented by the addition of anti-I-Abdq I-Edk antibodies (Fig. 1) and was specific for BMDC originating from BALB/c H-2d mice, since BMDC from C57Bl/6 H-2b mice were not able to present L1 to HD9L1 (data not shown). Altogether these data demonstrate that HD9L1 is specific to an H-2d major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted L1 peptide.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of the HD9L1 T-cell hybridoma. BMDC (5 × 104) were loaded in duplicate, as indicated, with the following: 1 μg of HPV16 VLP L1/L2/ml (VLP L1/L2), 1 μg of HV16 VLP L1/ml (VLP L1), 10 μg of BSA polypeptides/ml (BSA), 3 μl of E. coli χ6097 pYA3342L1 lysate (E.Coli L1), 1 μg of HPV16 VLP L1/L2 plus 0.4 μg of purified antibodies against I-Abdq I-Edk/ml (anti-IA/IE), and 1 μg of HPV16 VLP L1/L2 plus 0.4 μg of purified antibodies against CD86/ml as a control antibody (control Ab). IL-2 produced upon activation of the HD9L1 T-cell hybridoma was measured by tritiated thymidine incorporation in CTLL-2 (cpm).

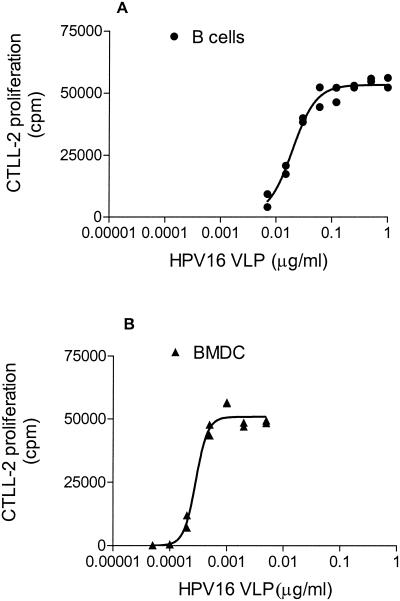

Presentation of HPV16 VLPs by BMDC and B cells in vitro.

The ability of splenic B cells and BMDCs to function as APC for HD9L1 was examined. B220+ B cells were prepared from the spleen of naive mice. The BMDCs were prepared from tibia and femur of naive mice and stimulated with murine rGM-CSF for 9 days (29). The latter displayed low levels of CD11c on their surface, intermediate levels of B7.2, and intermediate to high levels of major histocompatibility complex class II (data not shown) as described previously (29). Two hundred thousand B cells or BMDC were incubated with decreasing amounts of HPV16 VLPs. Best-fitting sigmoidal curves from duplicates cultures were drawn (GraphPad; Prism). A representative curve from three independent experiments for each cellular type is shown in Fig. 2A and B. Antigen doses required to induce 50% activation of HD9L1 as determined by Prism were 20 ng/ml (95% confidence interval [CI], 14 to 26 ng/ml) for B cells and 0.29 ng/ml (95% CI, 0.24 to 0.34 ng/ml) for BMDC. This shows that both B cells and BMDC are able to present HPV16 VLP in vitro, although, as expected, the latter were significantly more efficient in doing so (P < 0.001 by unpaired t test).

FIG. 2.

Antigen requirements for DC and B cells. L1 presentation to HD9L1 by 2 × 105 B cells (A) or BMDC (B) incubated with twofold dilutions of HPV16 VLPs. IL-2 produced upon activation of the HD9L1 T-cell hybridoma was measured by tritiated thymidine incorporation in CTLL-2 (cpm). Best-fitting sigmoidal curves were drawn with GraphPad (Prism).

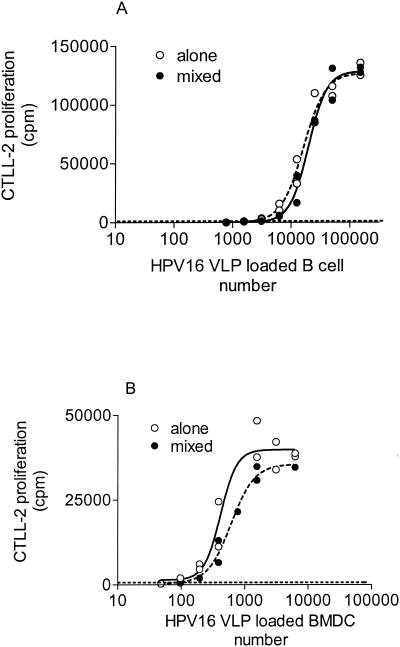

Sensitivity of HD9L1 for the detection of L1-presenting BMDC and B cells.

The minimal number of antigen-loaded B cells or BMDC necessary to activate HD9L1 was determined by using a saturating amount of HPV16 VLPs (2 μg/ml) and twofold dilutions of B cells or BMDC. Best-fitting sigmoidal curves from duplicate cultures were drawn, and a representative curve from independent experiments is shown for each cellular type (see Fig. 3A and B). Fifty percent activation of HD9L1 was obtained with 418 BMDC (95% CI, 305 to 573) or 16′193 B cells (95% CI, 13,444 to 19,504). This shows that on a cell number basis, L1-presenting BMDC are more easily detectable than L1-presenting B cells (P < 0.001 by unpaired t test). Since in vivo only a small percentage of cells expressed the antigen, we determined the sensitivity of the assay in the presence of bystander cells not expressing the antigen. Decreasing amounts of B cells or BMDC were incubated with HPV16 VLPs at saturating concentrations (2 μg/ml) and were supplemented up to 2 × 105 cells with additional B cells or BMDC, respectively. To avoid presentation by these naive cells, B cells were irradiated with 3,000 rad (2) and BMDC were fixed for 10 s at room temperature with 0.05% glutaraldehyde. These treatments completely abolished the antigen-presenting functions of these cells (data not shown). However, no statistically significant differences in HD9L1 activation were observed when homogeneous or mixed cell populations were compared (P > 0.05 by unpaired t test; see Fig. 3A and B). We then determined the minimal number of antigen-loaded cells that induced a detectable activation of HD9L1 (CTLL-2 proliferation greater than the background of CTLL-2 proliferation plus 3 SD). Using this criteria, 50 BMDC or 1,500 B cells were necessary to induce a detectable activation of HD9L1. This suggests that HD9L1 can detect L1-presenting BMDC or B cells when they represent only 0.025 and 0.75%, respectively, of the total cell population.

FIG. 3.

Efficiency of detection of L1-primed APC in a homogenous or mixed cell population. L1 presentation by B cells (A) and BMDC (B) to HD9L1 was measured by tritiated thymidine incorporation in CTLL-2 (cpm). (A) Twofold dilutions of in vitro L1-primed B cells alone (dashed line) or supplemented up to 2 × 105 with irradiated B cells (solid line) were tested. (B) Twofold dilutions of in vitro L1-primed BMDC alone (dashed line) or supplemented up to 2 × 105 with fixed BMDC (solid line) were tested. Best-fitting sigmoidal curves were drawn with GraphPad (Prism). Threshold activation of HD9L1 (dotted line) was defined as the mean background of CTLL-2 proliferation plus three times the SD.

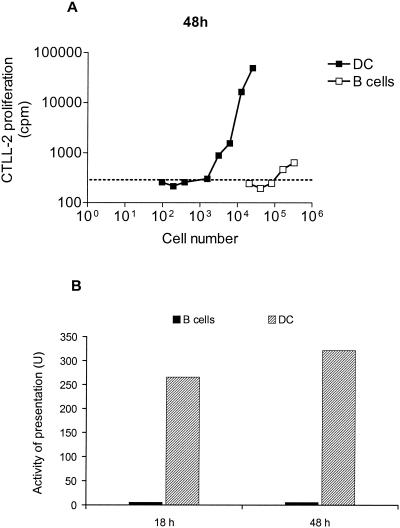

Presentation of HPV16 VLP in PLN.

To test the ability of HD9L1 to detect L1-APC primed in vivo, we immunized the mice at a site where the draining LN is well characterized (3). Ten mice were immunized in the hind footpad with 1 μg of HPV16 VLP, and PLN were taken 18 or 48 h later. PLN cells were separated into a B-cell fraction by MACS-positive selection with anti-B220-coated microbeads and a DC fraction by MACS positive selection with anti-CD11c-coated microbeads. Cytometric analysis revealed that the B-cell fraction was 98% B220+ and the DC fraction was 70% CD11c+ (data not shown). Twofold dilutions of these cell fractions were then tested for their ability to activate HD9L1. Similar dose-response curves were obtained 18 and 48 h after immunization, and results for the 48-h time point are shown in Fig. 4A. Three thousand DC isolated from the immune PLN 48 h after immunization were sufficient to induce detectable activation of HD9L1, whereas 1.5 × 105 B cells were required. To compare the efficiency of L1 presentation between different experiments and/or time points, antigen presentation activity was expressed in arbitrary units (reciprocal minimal number of cells necessary to induce detectable activation of HD9L1 × 106; see Fig. 4B). High L1 presentation activities in the DC fractions of the PLN isolated 18 and 48 h after immunization were observed (266 and 322 U, respectively), whereas only a low L1 presentation activity was measured for B cells (6 U). These results indicate that HD9L1 can recognize L1-antigenic complexes on the surface of APC primed in vivo.

FIG. 4.

L1 presentation by B cells or DCs in PLN of mice immunized in the hind footpad. (A) L1 presentation in PLN 48 h after immunization was measured by incorporation of tritiated thymidine in CTLL-2 (cpm). Twofold dilutions of B cells (open squares) or DC (closed squares) were tested. Threshold activation of HD9L1 (dotted line) was defined as the mean background of CTLL-2 proliferation plus three times the SD. (B) Activity of presentation in the PLN 18 and 48 h after immunization in arbitrary units (U, reciprocal minimal number of cells necessary to activate HD9L1 × 106).

DC and B cells of lung, trachea, and tracheobronchial LN (TBLN) rapidly take up HPV16 VLP after nasal vaccination of mice.

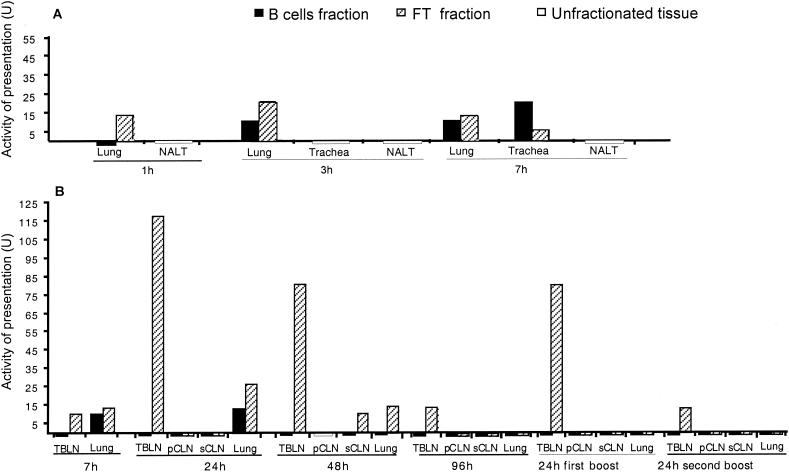

Mice were immunized with 5 μg of HPV16 VLP intranasally under anesthesia. This resulted in inhalation of ca. 30% of the inoculum after 15 min, while the rest remained in the nasal tissue (4) but was probably swallowed later on. Since oral immunization is not efficient at this dose of VLPs (4), it is unlikely that the gut-associated lymphoid tissue is induced following intranasal immunization of anesthetized mice. Thus, either the NALT, the BALT, the trachea, or the lung, alone or together, could act as mucosal inductive sites. We therefore decided to examine all these tissues and/or their draining LN for their ability to activate HD9L1. Mice were sacrificed at different time points after immunization (1 to 96 h). The lung, trachea, TBLNs (a double chain of LNs located along the trachea and the bronchi), superficial and posterior cervical LNs (sCLN and pCLN), and NALT were taken, digested with collagenase D, and depleted of T cells. In addition, PLN and/or the spleen were taken as sources of regionally distant APCs. When enough cells were available, they were further positively selected by MACS with anti-B220-coated microbeads. This resulted in B-cell fractions which were 95 to 98% pure, according to B220+ staining, and in FT fractions which were enriched in DC (10 to 15% CD11c+ CD11b+ cells in TBLN, CLN, and the lung and ca. 25% CD11c+ CD11b+ in the trachea) as determined by FACS analysis of naïve mice (data not shown). The B cells and the FT fractions were analyzed separately. All cell fractions were able to activate HD9L1 when purified HPV16 VLPs (2 μg/ml) were added in vitro, demonstrating that they contained functional APC and no suppressive activity (data not shown). The NALT, the lung, and the trachea, which are the first sites of contact with the antigen, were analyzed 1 (only lung and NALT), 3, and 7 h after immunization (Fig. 5A). L1-presenting activity was first detected in the FT fraction of the lung at 1 h (13 U), while it was then measured in both B cells and FT fractions of the lung at 3 h (10 and 20 U, respectively) and at 7 h (10 and 13 U, respectively) as well as in the trachea at 7 h (20 and 5 U, respectively). The presence of L1-presenting cells was analyzed 7, 24, 48, and 96 h after the first immunization, as well as 24 h after the second and the third immunizations in the corresponding draining LNs (pCLN, sCLN, and TBLN) and in the lung. Activity of L1 presentation persisted in the lung until 48 h (10 to 26 U) (see Fig. 5B). L1 presentation in the TBLN and the sCLN was found only in the FT fractions. Low L1 presentation activity was already detected in the TBLN at 7 h (13 U), while, high activity was measured at 24 and 48 h (117 and 80 U; see Fig. 5B), and it then decreased to 13 U at 96 h. Activity of presentation raised to 80 U 24 h after the first boost, while only 13 U was measured after the second one. To further characterize the APC responsible for the high activity of L1 presentation in TBLN 24 h after vaccination, TBLN from 10 mice were positively selected by MACS with anti-CD11c-coated microbeads. The cells recovered yielded an L1 presentation activity of 150 U (data not shown). This confirms that L1 presentation activity in the FT fraction is mainly due to CD11c+ DC. Low L1 presentation activity was detected only in the sCLN isolated at 48 h (10 U). As the sCLN drains the nasal epithelium, this data, together with the absence of detection of L1 presentation in the NALT and pCLN, suggested that uptake and/or presentation at this site was not efficient. As expected, L1-presenting cells were not detected in regionally distant LN or in organs, i.e., PLN or the spleen, which are not in immediate contact with the antigen inoculum (data not shown). Altogether, our results suggest that after nasal vaccination of anesthetized mice, the lung and the trachea are the major mucosal sites where HPV16 VLPs are taken up. L1 is presented either locally or in TBLN where high activity of L1 presentation by immigrating DCs was detected.

FIG. 5.

L1 presentation after nasal vaccination with HPV16 VLPs: activity of presentation (U) in the lung, the trachea, and the NALT (A) at 1, 3, and 7 h after immunization or in draining LNs and the lung (B) from 7 to 96 h after the first immunization and 24 h after the second and the third immunizations. Activities of presentation (U) were calculated as the reciprocal minimal number of cells necessary to activate HD9L1 × 106. Unfractionated tissues are represented by white bars, B cell fractions are represented by black bars, and FT fractions are represented by hatched bars.

DISCUSSION

Tracing antigen-specific cellular interactions in vivo is essential for understanding the development of immune responses. Interaction of the antigen at different sites or with different APC can determine whether immunity occurs. The efficiency of a prophylactic vaccine against HPV16 relies on the ability to induce a neutralizing immune response in genital secretions. Many reports suggested the importance of the NALT in the induction of a specific mucosal immune response after intranasal immunization (11, 18, 46, 49). However, we have previously shown that nasal vaccination with low doses of HPV16 VLP was inefficient if the antigen did not contact the lung of the mice (4). This showed that the NALT alone was not sufficient for the induction of the immune response against HPV16 VLP, although nasal boosting of parentally primed mice suggested that HPV16 VLPs might be sampled at this site (4). In this study, we localized the major sites involved in the immune response observed after nasal vaccination of mice with HPV16 VLPs. In vitro analysis showed that BMDC were very efficient APC for HPV16 VLPs. Naive B cells loaded with small amounts of VLPs or low numbers of B cells loaded with saturating amount of VLPs were also efficient at presenting HPV16 VLP in vitro. This is in contrast to what is reported for other antigens, where high amounts (>100 μg) or high numbers of B cells (>50′000) are usually necessary to activate a hybridoma (10, 31). It is generally assumed that B cells are not efficient APC except for rare repetitive antigens that can bind and cross-link specifically the B-cell receptor (33). There is no evidence yet that HPV16 VLPs behave similarly, and the role of HPV16 VLP presentation by the B cells in vivo remains unclear. After hind footpad immunization, L1-primed DCs were found in the draining LN within 18 h, similar to what was observed with hen egg white lysozyme antigen (17). These findings are in agreement with the migration pattern described by Austyn et al. for injected radiolabeled DC (3). Low L1 presentation activity was also found in the B-cell fraction of the PLN. However, it is unlikely that some free HPV16 VLP antigen is drained to the B-cell zone of this LN, and L1 presentation activity in the B-cell fraction is most probably caused by contaminating DC.

After nasal vaccination of anesthetized mice, we found a low level of L1 presentation activity for both B cells and DCs in the trachea and the lung. In contrast to the case with the PLN, the presentation activity detected in the B-cell fraction cannot be due to some DC contaminations, since the presentation activity level was not higher in the FT fraction of these tissues. This finding might be due to L1 presentation occurring in BALT for the lung or in larynx-associated lymphoid tissue for the trachea preparation that contained a rather high content of B cells after T-cell depletion (40%; data not shown), suggesting that some lymphoid tissue remained associated. A high L1 presentation activity was detected only in the FT or in the CD11c+ fraction of the draining TBLN, within 24 h. This probably reflects the migration pathways of DCs that have been primed in the lungs and trachea, where they reside in great numbers (19, 21, 22). A low-level and transient activity of presentation was also detected in the FT fraction of the sCLN at 48 h. This may result from the migration of DC primed in the nasal mucosa (28), and it suggests that L1 presentation did not occur in the NALT or was below the limit of detection. This is in agreement with results obtained in immunization experiments (4), suggesting that HPV16 VLP are sampled in the nasal lumen, but not efficiently. Our results suggest that the trachea, the lungs, and the TBLN are the major sites responsible for the development of the specific genital immune response after nasal vaccination of anesthetized mice with HPV16 VLP. Antibody-secreting cells committed in the TBLN may acquire a mucosal homing for the genital tract, suggesting that the TBLN act both as a systemic and mucosal inductive sites, as has been described for the mesenteric LN (8). Although nasal vaccination has often been used to induce efficient immune responses in the genital tract, to our knowledge, this paper is the first demonstration that presentation of the antigen in the lower respiratory tract and/or draining lymph nodes is necessary to do so. This finding might be linked to the particulate nature of the VLP antigen, which is folded in icosahedric particles of 55 nm in diameter, exhibiting repetitive structures on their surface (27). It has been proposed that soluble antigens were preferentially taken up by the epithelial cells in the nasal mucosa, while particles (1 to 5 μm in diameter [14, 24, 36]) were instead taken up by M cells (for a review, see reference1). Given the intermediate size of the particulate HPV16 VLP antigen, it is unclear where and how they would be taken up in the nasal lumen. It is also possible that our inability to detect VLP presentation in the NALT or pCLN relates to the low doses of antigen used in our experiments. Indeed, larger doses (>50 μg) or use of mucosal adjuvants, mainly the cholera toxin, were necessary when other soluble or particulate antigens were shown to be delivered through the nasal mucosa (18, 37, 40). Similarly, it was shown that high doses of VLPs (3 × 50 μg) were able to induce specific humoral responses when given by the oral route (39), thus suggesting that delivery through the gut-associated lymphoid tissue was efficient at this dose of VLPs and that this might also be the case with delivery through the NALT. The ability of HPV16 VLP to induce strong immune responses in the absence of adjuvant and at low doses probably relates to the highly efficient uptake and/or presentation by DC, as demonstrated here with BMDC in vitro, together with the recently reported acute activation of these cells by HPV16 VLPs (30). It is thus most probably the high abundance of DC in the trachea and lungs (21) that rendered the lower respiratory tract so efficient for HPV VLP vaccination.

In conclusion, this study suggests that human protocols of vaccination against HPV16 genital infection should be designed in such a way that they specifically target the lower respiratory tract. We are currently testing this hypothesis by comparing aerosol versus nasal spray vaccination with purified HPV16 VLPs in female volunteers.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Majcherczyk and S. Wirth-Dulex for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Fonds de Service of the Department of Gynecology and by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31-52892.97 and 631-057969.99) to D.N.-H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida, A. J., and H. O. Alpar. 1996. Nasal delivery of vaccines. J. Drug Target. 3:455-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashwell, J. D., M. K. Jenkins, and R. H. Schwartz. 1988. Effect of gamma radiation on resting B lymphocytes. II. Functional characterization of the antigen-presentation defect. J. Immunol. 141:2536-2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austyn, J. M., J. W. Kupiec-Weglinski, D. F. Hankins, and P. J. Morris. 1998. Migration patterns of dendritic cells in the mouse. Homing to T cell-dependant areas of spleen, and binding with marginal zones. J. Exp. Med. 67:646-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balmelli, C., R. B. S. Roden, A. Potts, J. T. Schiller, P. De Grandi, and D. Nardelli-Haefliger. 1998. Nasal immunization of mice with human papillomavirus type 16 particles elicits neutralizing antibodies in mucosal secretions. J. Virol. 72:8220-8229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bienenstock, J., N. Johnston, and D. Y. E. Perey. 1973. Bronchial lymphoid tissue. I. Morphologic characteristics. Lab. Investig. 28:686-692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandtzaeg, P., and T. S. Halstensen. 1992. Immunology and immunopathology of tonsils. Adv. Otorhinol. 47:64-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandtzaeg, P., P. L. Jahnsen, I. N. Farstad, and G. Haraldsen. 1997. Mucosal immunology of the upper respiratory tract. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 820:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briskin, M., D. Winsor-Hines, A. Shyjan, N. Cochran, S. Bloom, J. Wilson, L. M. McEvoy, E. C. Butcher, N. Kassam, C. R. Mackay, W. Newman, and D. J. Ringler. 1997. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 151:97-110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceredig, R., J. W. Lowenthal, M. Nabholz, and H. R. MacDonald. 1985. Expression of interleukin-2 receptors as a differentiation marker on intrathymic stem cells. Nature 314:98-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesnut, R. W., S. M. Colon, and H. M. Grey. 1982. Antigen presentation by normal B cells, B cell tumors, and macrophages: functional and biochemical comparison. J. Immunol. 128:1764-1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debard, N., D. Buzoni-Gatel, and D. Bout. 1996. Intranasal immunization with SAG1 protein of toxoplasma gondii in association with cholera toxin dramatically reduces development of cerebral cyst after oral infection. Infect. Immun. 64:2158-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehaan, A., J. F. Tomee, J. P. Huchshorn, and J. Wilschut. 1995. Liposomes as an immunoadjuvant system for stimulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses against inactivated measles virus administered intranasally to mice. Vaccine 13:1320-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Tommaso, A., G. Saletti, M. Pizza, R. Rappuoli, G. Dougan, S. Abrignani, G. Douce, and M. T. De Magistris. 1996. Induction of antigen-specific antibodies in vaginal secretions by using a nontoxic mutant of heat-labile enterotoxin as a mucosal adjuvant. Infect. Immun. 64:974-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eldridge, J. H., C. J. Hammond, J. A. Meulbroek, J. K. Staas, R. W. Gilley, and T. R. Tice. 1990. Controlled vaccine released in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. I. Orally administered biodegradable microspheres target the Peyer's patches. J. Control. Release 11:205-214. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallichan, W. S., and K. L. Rosenthal. 1995. Specific secretory immune responses in the female genital tract following intranasal immunization with a recombinant adenovirus expressing glycoprotein B of herpes simplex 2 virus. Vaccine 13:1589-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gebert, A., and R. Pabst. 1999. M cells at locations outside the gut. Semin. Immunol. 11:165-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guéry, J.-C., F. Ria, and L. Adorini. 1996. Dendritic cells but not B cells present antigenic complexes to class II-restricted T cells after administration of protein in adjuvant. J. Exp. Med. 183:751-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hameleers, D. M. H., I. van der Ven, J. Biewenga, and T. Sminia. 1991. Mucosal and systemic antibody formation in the rat after intranasal administration of three different antigens. Immunol. Cell Biol. 69:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havenith, C. E. G., P. P. M. C. Miert, A. J. Breedijk, M. G. H. Betjes, R. H. J. Beelen, and E. C. M. Hoefsnit. 1993. Migration of dendritic cells into the draining lymph nodes of the lung after intratracheal instillation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Biol. Mol. 9:484-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heritage, P. L., M. A. Brook, B. J. Underdown, and M. R. McDermott. 1998. Intranasal immunization with polymer-grafted microparticles activates the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue and draining lymph nodes. Immunology 93:249-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holt, P. G., M. A. Schon-Hegrad, J. Olivier, B. J. Holt, and P. G. McMenamin. 1990. A contiguous network of dendritic antigen presenting cells within the respiratory epithelium. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 91:155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holt, P. G., M. A. Schon-Hegrad, M. J. Phillips, and P.-G. McMenamin. 1989. Ia-positive dendritic cells form a tightly meshed network within human airway epithelium. Clin. Exp. Allergy 19:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopkins, S., J.-P. Kraehenbuhel, F. Schödel, A. Potts, D. Peterson, P. De Grandi, and D. Nardelli-Haefliger. 1995. A recombinant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine induces local immunity by four different routes of immunization. Infect. Immun. 63:3279-3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jani, P., G. W. Halbert, J. Langridge, and A. T. Florence. 1990. Nanoparticle uptake by the rat gastrointestinal mucosa: quantitation and particle size dependency. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 42:921-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kappler, J. W., B. Skidmore, J. White, and P. Marrack. 1981. Antigen-inducible, H-2 restricted, interleukin-2-producing T cell hybridomas. J. Exp. Med. 153:1198-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kihara, T., Y. Fujimura, J. Uchida, Miyashima, and S. Nagasaki. 1986. Structure and origin of microfold cells (M cells) in solitary lymphoid follicle of human larynx. J. Electron Microsc. 19:5-6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirnbauer, R. F., F. Booy, N. Cheng, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1992. Papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 89:12180-12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuper, C. F., P. J. Koornstra, D. M. H. Hameleers, J. Biewenga, B. J. Spit, A. M. Duijvestijn, P. J. C. V. B. Viesman, and T. Sminia. 1992. The role of nasopharyngeal lymphoid tissue. Immunol. Today 13:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labeur, M. S., B. Roters, B. Pers, A. Mehling, T. A. Luger, T. Schwarz, and S. Grabbe. 1999. Generation of tumor immunity by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells correlates with dendritic cell maturation stages. J. Immunol. 162:168-175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenz, P., P. M. Day, Y. Y. S. Pang, S. A. Frye, P. N. Jensen, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 2001. Papillomavirus-like particles induce acute activation of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 166:5346-5355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malynn, B. A., D. T. Romeo, and H. H. Wortis. 1985. Antigen-specific B cells efficiently present low doses of antigen for induction of T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 135:980-988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuo, K., T. Yoshikawa, T. Asanuma, T. Iwasaki, Y. Hagiwara, Z. Chen, S.-E. Kadowaki, H. Tsujimoto, T. Kurata, and S.-I. Tamura. 2000. Induction of immunity by nasal influenza vaccine administered in combination with an adjuvant (cholera toxin). Vaccine 18:2713-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milich, D. R., M. Chen, F. Schödel, D. L. Peterson, J. E. Jones, and J. L. Hughes. 1997. Role of B cells in antigen presentation of the hepatitis B core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14648-14653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nardelli-Haefliger, D., R. B. S. Roden, J. Benyacoub, R. Sahli, J.-P. Kraehenbuhl, J. T. Schiller, P. Laschat, A. Potts, and P. D. Grandi. 1997. Human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like-particles expressed in attenuated Salmonella typhimurium elicit mucosal and systemic neutralizing antibodies in mice. Infect. Immun. 65:3328-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pal, S., E. M. Peterson, and L. D. L. Maza. 1996. Intranasal immunization induces long-term protection in mice against a Chlamydia trachomatis genital challenge. Infect. Immun. 64:5341-5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payne, J. M., B. F. Sansom, R. J. Garner, A. R. Thomson, and B. J. Miles. 1960. Uptake of small resin particles (1-5 μm diameter) by the alimentary canal of the calf. Nature 188:586-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porgador, A., H. F. Staats, Y. Itoh, and B. L. Kelsall. 1998. Intranasal immunization with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope peptide and mucosal adjuvant cholera toxin: selective augmentation of peptide-presenting dendritic cells in nasal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Infect. Immun. 66:5876-5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Revaz, V., J. Benyacoub, W. M. Kast, J. T. Schiller, P. De Grandi, and D. Nardelli-Haefliger. 2001. Mucosal vaccination with a recombinant Salmonella typhimurium expressing human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) L1 virus-like particles (VLPs) or HPV16 VLPs purified from insect cells inhibits the growth of HPV16-expressing tumor cells in mice. Virology 279:354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose, R. C., C. Lane, S. Wilson, J. A. Suzich, E. Rybicki, and A. L. Williamson. 1999. Oral vaccination of mice with human papillomavirus virus-like particles induces systemic virus-neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine 17:2129-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell, M. W., Z. Moldoveanu, P. L. White, G. J. Sibert, J. Mestecky, and S. M. Michalek. 1996. Salivary, nasal, genital, and systemic antibody responses in monkeys immunized intranasally with a bacterial protein antigen and the cholera toxin B subunit. Infect. Immun. 64:1272-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarmiento, M., M. R. Loken, and F. W. Fitch. 1981. Structural differences in cell surface T25 polypeptides from thymocytes and cloned T cells. Hybridoma 1:13-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw, D. M., B. Gaerthe, R. J. Leer, G. M. M. Van der Stap, C. Smittenaar, M.-J. Heijne den Bak-Glashouwer, J. E. R. Thole, F. J. Tielen, P. H. Pouwels, and C. E. G. Havenith. 2000. Engineering the microflora to vaccinate the mucosa: serum immunoglobulin G responses and activated draining cervical lymph nodes following mucosal application of tetanus toxin fragment C-expressing lactobacilli. Immunology 100:510-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staats, H. F., W. G. Nichols, and T. J. Palker. 1996. Mucosal immunity to HIV-1: systemic and vaginal antibody responses after intranasal immunization with the HIV-1 C4/V3 peptides T1SP10 MN(A). J. Immunol. 157:462-472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamura S., T. Iwasaki, A. H. Thompson, H. Asunama, Z. Chen, Y. Suzuki, C. Aizawa, and T. Kurata. 1998. Antibody-forming cells in the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue during primary influenza virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 79:291-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tebbey, P. W., C. A. Scheuer, J. A. Peek, D. Zhu, N. A. LaPierre, B. A. Green, E. D. Phillips, A. R. Ibraghimov, J. H. Eldridge, and G. E. Hancock. 2000. Effective mucosal immunization against respiratory syncytial virus using purified F protein and a genetically detoxified cholera holotoxin, CT-E29H. Vaccine 18:2723-2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ugozzoli, M., D. T. O'Hagan, and G. S. Ott. 1998. Intranasal immunization with simplex herpes virus type 2 recombinant gD2: the effect of adjuvants on mucosal serum antibody response. Immunology 93:563-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walboomers, J. M. M., M. V. Jacobs, M. M. Manos, F. X. Bosch, J. A. Kummer, K. V. Shah, P. J. S. Sniders, J. Peto, C. J. L. M. Meier, and N. Munoz. 1999. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 189:12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, H.-Y., E. B. Nikilova, K. W. Beagley, and M. W. Russel. 1996. Induction of antibody-secreting cells and T-helper and memory cells in murine nasal lymphoid tissue. Immunology 88:493-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, H.-Y., and M. W. Russel. 1993. Induction of mucosal immunity by intranasal application of a streptococcal surface protein antigen with the cholera toxin B subunit. Infect. Immun. 61:314-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, H. Y., and M. W. Russell. 1997. Nasal lymphoid tissue, intranasal immunization, and compartmentalization of the common mucosal immune system. Immunol. Res. 16:187-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia, W., C. E. Pinto, and R. L. Kradin. 1995. The antigen-presenting activities of Ia+ dendritic cells shift dynamically from lung to lymph node after an airway challenge with soluble antigen. J. Exp. Med. 181:1275-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]