Abstract

Most bacterial chromosomes carry an analogue of the parABS systems that govern plasmid partition, but their role in chromosome partition is ambiguous. parABS systems might be particularly important for orderly segregation of multipartite genomes, where their role may thus be easier to evaluate. We have characterized parABS systems in Burkholderia cenocepacia, whose genome comprises three chromosomes and one low-copy-number plasmid. A single parAB locus and a set of ParB-binding (parS) centromere sites are located near the origin of each replicon. ParA and ParB of the longest chromosome are phylogenetically similar to analogues in other multichromosome and monochromosome bacteria but are distinct from those of smaller chromosomes. The latter form subgroups that correspond to the taxa of their hosts, indicating evolution from plasmids. The parS sites on the smaller chromosomes and the plasmid are similar to the “universal” parS of the main chromosome but with a sequence specific to their replicon. In an Escherichia coli plasmid stabilization test, each parAB exhibits partition activity only with the parS of its own replicon. Hence, parABS function is based on the independent partition of individual chromosomes rather than on a single communal system or network of interacting systems. Stabilization by the smaller chromosome and plasmid systems was enhanced by mutation of parS sites and a promoter internal to their parAB operons, suggesting autoregulatory mechanisms. The small chromosome ParBs were found to silence transcription, a property relevant to autoregulation.

Like all organisms, bacteria must actively segregate their chromosomes before cell division if new cells are to be viable. How they do this is still an open question. The early finding (42) that the replication origin regions of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas putida contain homologues of the parAB loci responsible for active partition of low-copy-number plasmids had suggested that the answer would be straightforward. In plasmids, ParB protein binds to a specific, centromere-like site, parS, and the complexes thus formed are presumed to interact to pair sibling plasmid copies: ParA protein, an ATPase, splits the pair and helps drive the plasmid molecules towards each pole (15). It appeared that this process, together with factors needed to facilitate the movement of the much bulkier chromosome such as dispersion of parS sites (18, 34) and the DNA-condensing properties of SMC proteins (14, 41), would suffice to explain chromosome partition.

Such has not proved to be the case, at least for the bacteria studied so far. The partition phenotype of chromosomal parAB mutants is often weak or conditional. In B. subtilis, parB (spo0J) mutants generate anucleate cells (17), but parA (soj) mutations do not (50), and positioning of origins is little affected by the deletion of spo0J (28). In P. putida, parAB mutations do generate anucleate cells, but this is restricted largely to cultures undergoing slow or decelerating growth (10, 33). Furthermore, the role of parAB homologues in partition may be difficult to analyze, owing to their participation in other activities, such as the regulation of the sporulation cascade in B. subtilis (39, 43) or of cell division in Caulobacter crescentus (38). It is also notable that certain species, e.g., Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae, lack parAB homologues altogether, implying that bacteria elaborate other types of partition system. Indeed, there have been several proposals and some evidence for other functions playing a major part in chromosome segregation. The motive force could be generated by replication itself (29), by the successive insertion of cotranslated gene products into the membrane (“transertion”) (51), or by release from sibling chromosome “cohesion” (3, 48). Active navigation could be provided by factors acting on a non-parS, origin-linked centromere (12, 21) or by actin-like MreB proteins (9, 20, 25). The only direct evidence that chromosomal parAB loci act in partition is their ability to stabilize unstable vectors carrying cognate parS sites (2, 10, 34, 52).

These findings are all based on studies of mitosis in single-chromosome species. We asked whether the need to coordinate the movement and positioning of two or more bulky nucleoids could demand a degree of precision that only parABS systems can provide. The study of partition in such bacteria might give a clearer view of the role of these systems. Accordingly, we have investigated the partition function of parABS determinants of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Burkholderia species are β-proteobacterial rods notable for their versatility of metabolism and habitat and for the multipartite nature of their genomes. Like many Burkholderia species, the B. cenocepacia isolate we have studied is a pathogen associated with cystic fibrosis. Its genome comprises three chromosomes (defined as carrying rRNA genes) and a low-copy-number plasmid.

The multichromosome state raises a potential problem. The chromosomal parS sites described so far are remarkably uniform, with most being minor variants of a canonical inverted repeat sequence, 5′-TGTTNCACGTGAAACA, present in the genomes of representatives of nearly all major bacterial divisions. Maintenance of this uniformity in a multipartite genome might require a mechanism to prevent ParAB from confusing and missegregating chromosomes. The three chromosomes of B. cenocepacia could either carry the same parS site and be partitioned, with the help of accessory anti-incompatibility functions, by a single, “master” ParAB protein duo or each have a distinct parS partitioned independently by its own ParAB. Alternatively, the parS sites might allow a degree of cross-reaction to help coordinate partition or be absent from one or more chromosomes that are segregated by a different mechanism. In this paper, we analyze parABS systems of B. cenocepacia and assess their partition activity in an attempt to determine which of the above strategies B. cenocepacia could have adopted to manage mitosis of its genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The B. cenocepacia isolate used was J2315, gemnovar III, of the ET12 lineage, which serves as the United Kingdom cystic fibrosis reference strain; it was purchased from the Belgian Coordinated Collection of Microorganisms (LMG16656). Its genome was sequenced by the Sanger Centre (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/bc/). Escherichia coli K-12 strain DH10B (13) was used as the host for transformation and stabilization tests, and strain MC1061 (4) was used as the host for silencing measurements. Plasmids are listed in Table 1, and maps of plasmid vectors are shown in Fig S1 (see the supplemental material). The vectors for expression of parAB were pBBR1mcs5 (high copy number) and pAM238 (pSC101 based). parS sites were tested for centromere function following insertion into pDAG203, a mini-F with a deletion of the entire sop locus, and for silencing by insertion upstream of the ldc promoter in pDAG123 (see below), followed by recombinational transfer to λRS88 (47) and lysogenization of MC1061.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| pDAG203 | Mini-F Δ(sopOPABC) cat+ (6.67 kb) | 30 |

| pDAG123 | pRS551 (reppMB1bla+ KanrlacZYA) carrying pldc (12.6 kb) | 31, 47 |

| pAM238 | reppSC101aadA; polylinker of pUC18 (4.3 kb) | 8 |

| pBBR1MCS5 | reppBBR1mobRK2 Genr (4.77 kb) | 24 |

| pDAG551 | pDAG203 with single c1 parS between AflIII-SexAI | This work |

| pDAG552 | pDAG203 with single c2 parS between AflIII-Bsu36I | This work |

| pDAG553 | pDAG203 with single c3 parS between AflIII-Bsu36I | This work |

| pDAG554 | pDAG203 with single p1 parS between AflIII-Bsu36I | This work |

| pDAG555 | pDAG203 with c2 parS cluster between PmlI-Bsu36I | This work |

| pDAG556 | pDAG203 with c3 parS cluster between PmlI-Bsu36I | This work |

| pDAG557 | pDAG203 with p1 parS cluster between PmlI-Bsu36I | This work |

| pDAG558 | pAM238 with c1 parAB fragment (including 91 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-SphI | This work |

| pDAG559 | pAM238 with c2 parAB fragment (including 81 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-HindIII | This work |

| pDAG560 | pAM238 with c3 parAB fragment (including 141 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-SphI | This work |

| pDAG561 | pAM238 with p1 parAB fragment (including 126 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-SphI | This work |

| pDAG562 | pBBR1MCS5 with c1 parAB fragment (including 256 bp upstream of parA) between SpeI-HindIII | This work |

| pDAG563 | pBBR1MCS5 with c2 parAB fragment (including 81 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-BamHI | This work |

| pDAG564 | pBBR1MCS5 with c3 parAB fragment (including 267 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-BamHI | This work |

| pDAG565 | pBBR1MCS5 with p1 parAB fragment (including 126 bp upstream of parA) between XbaI-BamHI | This work |

| pDAG566 | pDAG563 with G→A in central CG of internal parS* | This work |

| pDAG567 | pDAG565 with C→T in central CG of internal parS | This work |

| pDAG568 | pDAG564 with T→A mutation of promoter −10 (TAAAATa) in c3 parA | This work |

| pDAG571 | pDAG123 with single c1 parS at EcoRI upstream of pldc::lacZYA | This work |

| pDAG572 | pDAG123 with single c2 parS at EcoRI upstream of pldc::lacZYA | This work |

| pDAG573 | pDAG123 with single c3 parS at EcoRI upstream of pldc::lacZYA | This work |

| pDAG574 | pDAG123 with single p1 parS at EcoRI upstream of pldc::lacZYA | This work |

The mutated base is underlined.

Growth conditions.

Bacteria were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium and, for plasmid stabilization tests, in M9-CSA (M9 salts, 0.4% glucose, 0.2% Casamino Acids). The following antibiotics (in micrograms per milliliter) were added as appropriate: chloramphenicol (Cm), 20; gentamicin, 2.5; spectinomycin, 20; kanamycin, 50.

Plasmid construction.

Single parS sites were synthesized as complementary 16-mers (Table 2) tailed for insertion into mini-F pDAG203 as described in Table 1. parS clusters of c2, c3, and p1 were amplified from J2315 DNA by PCR using oligonucleotide primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and DNA polymerase Pfu (Stratagene) or Phusion (Finnzyme) as 1,041-, 1,350- and 469-bp fragments and inserted into pDAG203 (Table 1). parAB genes were likewise amplified from J2315 DNA using oligonucleotides (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) designed for insertion downstream of the lac promoter in pBBR1mcs5 and pAM238.

TABLE 2.

parS oligonucleotides

| Replicon | Oligonucleotide name (FOP no.) | Sequencea (5′→3′ top, 3′←5′ bottom) | Restriction site(s) for:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insertion | Screeningb | |||

| c1 | 11 | cgtgTGTTTCACGTGAAACA | AflIII- | PmlI |

| 12 | ACAAAGTGCACTTTGTggacc | -SexAI | ||

| c2 | 22 | cgtgcccGTTTATGCGCATAAACccc | AflIII- | FspAI |

| 23 | gggCAAATACGCGTATTTGgggagt | -Bsu36I | ||

| c3 | 24 | cgtgcccGTTGTCACGTGACAACccc | AflIII- | PmlI |

| 25 | gggCAACAGTGCACTGTTGgggagt | -Bsu36I | ||

| p1 | 26 | cgtggggCTTGGCTCGAGCCAAGggg | AflIII- | XhoI |

| 27 | cccGAACCGAGCTCGGTTCcccagt | -Bsu36I | ||

Capital letters show parS sequence; lowercase letters show cohesive ends.

Sites present in the parS palindrome used to screen for insertion.

parS sites were placed near promoters for silencing assays by amplification from mini-F derivatives (pDAG551, pDAG552, pDAG553, and pDAG554) using flanking sequence primers (5′-CGCAATTGAAACTGGATGGCTTTCTTGC and 5′-CGCAATTGGGATGAATGGCAGAAATTCG) (MfeI sites are underlined) to generate fragments of 1,050 bp (c1) and 708 bp (c2, c3, and p1). After cleavage with MfeI, the fragments were inserted at the EcoRI site upstream of the pldc::lacZ fusion in pDAG123, and plasmid products with identically oriented inserts were selected to give the series pDAG571, pDAG572, pDAG573, and pDAG574 (parS of c1, c2, c3, and p1, respectively).

Mutagenesis of motifs internal to parAB.

The internal c3 parA promoter −10, the c2 parS*, and the p1 parS were amplified by PCR using one oligonucleotide with the desired mutation (in boldface type below) and another with a site convenient for substituting the product for the wild-type sequence. For c3, K3PR (5′-AAAATTTCTTCACGCATTTTTGTTTTTCCATTGAC) and K3SM (5′-GCAGGATCCCGACCACAACGATCAACAAA) produced a 754-bp fragment that was substituted for the pDAG564 BamHI-DraI fragment to yield pDAG568. For c2, K2SMA (5′-ACATAAAGTCGGGCAGCTG) (the mutant parS* half-site is underlined) and FOP41 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) produced a 759-bp fragment that was substituted for the pDAG563 FspAI-BamHI fragment to yield pDAG566. For p1, PLSM (5′-GAACTTCATATGTCTGCCCAATTTCGTACTTCGTGGCACCTTGGCTTGAGCCAACCT) and FOP37 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) produced a 994-bp fragment that was substituted for the BamHI-NdeI fragment of pDAG565 to yield pDAG567. The mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

DNA procedures.

B. cenocepacia DNA was purified from strain J2315 as described previously for P. putida (10), except that digestion of the lysate with sodium dodecyl sulfate and protease K at 50°C was prolonged to 15 h and phenol extraction of the digest was repeated four times. Plasmids and DNA fragments were purified using QIAGEN kits. In vitro DNA methodology and electrotransformation were performed according to standard procedures.

Plasmid stabilization test.

Cultures of DH10B derivatives carrying a ParAB producer plasmid and a parS-bearing mini-F were started by 400-fold dilution from overnight cultures into M9-CSA with gentamicin and Cm (selective for pBBR1mcs5 and mini-F, respectively) and incubated at 37°C for five generations to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.2. Cells were then diluted in M9-CSA without Cm to allow growth of mini-F-free segregants, maintained in the exponential growth phase for 25 to 30 generations by sequential dilution, and assayed at intervals for maintenance of mini-F (Cm resistance) as follows. Cells were spread onto an initial layer of L agar, covered with a second layer, and incubated at 37°C overnight. The colonies were counted and then overlaid with a third layer, this one containing Cm, and again incubated overnight. Cmr colonies continued to grow and were counted as large colonies the next day. The number of generations was calculated from optical density measurements.

Silencing assay.

Cells of MC1061 derivatives lysogenic for λRS88 parS-Pldc::lacZYA were diluted from cultures grown overnight and were grown exponentially in LB plus kanamycin to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.25. Cultures were sampled and assayed for β-galactosidase as previously described (27).

RESULTS

Origin-proximal location of parAB loci.

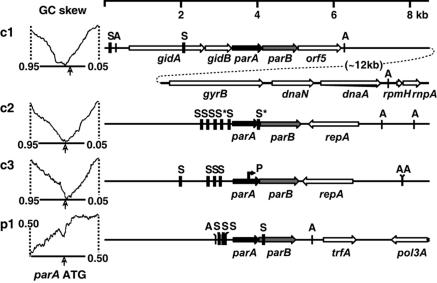

The B. cenocepacia J2315 genome comprises chromosomes of 3.87, 3.22, and 0.88 Mbp (c1, c2, and c3, respectively) and a 92.7-kbp plasmid (p1). It has been sequenced by the Sanger Centre. Using the BlastP program (46) with Soj and other ParA sequences as probes, we found several parA homologues but only four that are situated immediately upstream of open reading frames for ParB-like proteins, one in each replicon (Fig. 1). These parAB loci are close to the cumulative GC-skew minima in c1, c2, and c3, consistent with proximity to origins of bidirectionally replicated chromosomes (35). The GC skew in p1 changes direction only locally, possibly indicating overall unidirectional replication of the plasmid; parAB is situated at the most pronounced local minimum. The likelihood that the parAB loci do indeed lie in the origin regions is increased by their proximity to DnaA boxes; c1 and c2 have additional boxes (not shown) close to their GC-skew minima.

FIG. 1.

Location of parAB loci and parS sites. At left, arrows indicate the position of each parA homologue start codon relative to the GC skew of the 10th (0.95 to 0.05) of the replicon centered on the GC-skew minimum (c1 to c3) or of the whole replicon (p1). Genetic map sketches are aligned at parA homologue start codons and show only genes characteristic of chromosome origin regions or relevant to plasmid maintenance. orf5 is a gene of unknown function, named for its position in the gid-par operon. repA (c2 and c3) signifies generic resemblance to plasmid replication control genes; trfA indicates homology with the corresponding RK2 gene. S, parS sites (c1) or parS-like palindromes (c2, c3, and p1); S*, degenerate parS-like sequences; P, predicted promoter internal to parA of c3; A, predicted DnaA box motifs based on the consensus 5′-TTATCCAC.

The environment of the parAB loci reveals two types of replication origin domains (Fig. 1). In c1, it includes the only gidAB, dnaA, rpmH, rnpA, and gyrB genes in the genome, all characteristic of chromosomal origins; gidAB and parAB actually appear to belong to the same operon. In c2, c3, and p1, on the other hand, parAB is adjacent to elements typical of low-copy-number plasmids: a gene (repA/trfA) for a plasmid-like replication control/initiator protein and a cluster of directly repeated sequences similar to iterons (not shown). Thus, although the size, rRNA gene content, and GC skew qualify c2 and c3 as chromosomes, the replication control regions in which their parAB loci are embedded are typical of low-copy-number plasmids.

Diversity of parAB loci.

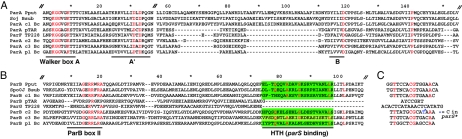

The ParA homologues of J2315, including that of the plasmid, resemble those of other bacterial chromosomes in sharing the A, A′, and B components of Walker box ATPase active sites and in lacking the extended N-terminal domain that regulates par operon transcription in many low-copy-number plasmids. However, alignment of their peptide sequences (Fig. 2A) showed that only the c1 ParA is closely related to known chromosomal ParAs. Those of c2, c3, and p1 differ chiefly in that they lack two peptide stretches that flank a predicted (46) helical region (centered on position 80 in Fig. 2A), which in c1 ParA is predicted to be relatively unstructured, indicating a taxonomic, and possibly functional, distinction. The ParAs of c2, c3, and p1 show notable similarity to ParA of the plasmid pTAR (23) and ParF of TP228 (1).

FIG. 2.

Parts of the aligned ParA (A) and ParB (B) amino acid sequences that distinguish subgroups. Residues that are identical (A) or nearly so (B) in all examples shown are in red. Numbers above show distances, not coordinates, and double hatch marks denote sequences not shown (18 residues just after the A box in A). The Walker A (nucleotide binding), A′ (catalytic), and B (Mg binding) motifs constitute the ATPase active site. ParBII is a motif identified previously (52). The helix-turn-helix (HTH) motifs are shaded green. The HTH of c3 is weakly predicted relative to the others. Note the short A′-B-box interval in the c2, c3, and p1 ParAs, very similar to the pTAR and TP228 homologues, and the absence of all HTH region homology in the latter ParBs. (C) Aligned parS and parS-like sequences with fully conserved bases in red. Note the dissimilarity of the pTAR and TP228 par region repeats.

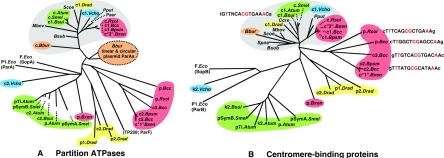

The B. cenocepacia ParB-like sequences (Fig. 2B) are more divergent than the ParAs but contain the motifs typical of the ParB group (52). The relationship with the pTAR and TP228 homologues shown by the ParAs is not maintained by the ParBs, particularly with respect to the DNA-binding motif, which is predicted to be a helix-turn-helix in the B. cenocepacia homologues but in TP228 is of a different type, termed ribbon-helix-helix, located at the C terminus (11). More general relationships within the ParB group came to light upon an examination of the phylogeny of ParAs and ParBs in bacteria known to have multipartite genomes (Fig. 3). This analysis showed first that the phylogeny of ParB proteins broadly follows that of their ParA partners, presumably reflecting their coevolution. Second, and more strikingly, it shows that the differentiation of the largest chromosome, c1, from the others is characteristic of all multipartite genomes: the ParABs of these chromosomes are more similar to each other and to those of monochromosomal bacteria than to their smaller chromosome or megaplasmid cohabitants. In contrast, the secondary replicon ParABs of each species and its close relatives tend strongly to form distinct clusters that correspond to host phyla (Fig. 3), indicating host selection at some level for compatibility or performance of these ParA-ParB pairs.

FIG. 3.

Phylogeny of partition proteins of bacteria with multipartite genomes. Predicted amino acid sequences of ParA homologues (A) and ParB homologues (B) were aligned and phylogenetically compared using ClustalX. Large blocks of heterology, such as N-terminal extensions present in some ParAs but absent from others, were discarded from the analysis. The option “tree-correct for multiple substitutions” was used. Phylogenetic trees were viewed using Treeview. Homologues of individual multipartite genomes or closely related groups are indicated in color, and others are single-chromosome species included as markers. All branches are of the correct length, but some are extended by dotted lines for clarity. Abbreviations for full species names are as follows: Atum, Agrobacterium tumefaciens; Bbur, Borrelia burgdorferi; Bcc, Burkholderia cenocepacia; Bpsm, Burkholderia pseudomallei; Bsub, Bacillus subtilis; Bsui, Brucella suis; Bxen, Burkholderia xenovorans; Ccre, Caulobacter crescentus; Drad, Deinococcus radiodurans; Eco, Escherichia coli; Mbov, Mycobacterium bovis; Paer, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Pput, Pseudomonas putida; Rsol, Ralstonia solenacearum; Scoe, Streptomyces coelicolor; Smel, Sinorhizobium meliloti; Spne, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Vcho, Vibrio cholerae. The group comprising the largest chromosome of every species, denoted as c or c1, forms a distinct cluster, as shown by the shaded area. Secondary replicons are shown as c2 and c3 or in the case of megaplasmids by their given names or p1 and p2. Large and small replicons of B. xenovorans were named chromosomes 2 and 1, respectively (Joint Genome Institute) and are thus shown in quote marks here. The Borrelia burgdorferi secondary replicon ParBs are less well defined than the ParA group and are not shown. In B, the canonical parS sequence is shown next to the large chromosome group and the parS-like palindromes of B. cenocepacia and R. solanacearum are shown beside their replicons, with conserved bases in red.

Replicon specificity of candidate parS sequences.

To identify parS sites, we first searched the genome for examples of the “universal” centromere sequence (34). Only two were found, both upstream of the parAB locus in c1 (Fig. 1). However, a search of the parAB regions for inverted repeat sequences of any kind revealed novel but related palindromes in c2, c3, and p1 (Fig. 2B and 3C). These putative parS sites share with the “universal” parS an inverted repeat of 7 bp with T and C at positions 2 and 7, respectively. Among themselves, they share a singular arrangement distinct from the c1 parS sites: on all three replicons, the candidate parS sites are clustered at similar positions with respect to their parAB loci (Fig. 1), and the sequences of the sites on a given replicon are identical and specific to that replicon (Fig. 2). The only exceptions are on c2, whose putative parS cluster and parA-parB intergenic region each include a single imperfect parS-like palindrome (Fig. 1 [denoted S*] and 2C), and p1, which carries an additional site in its parB N terminus.

The location of the parS-like sites strongly suggested that they are linked functionally to the putative parAB loci.

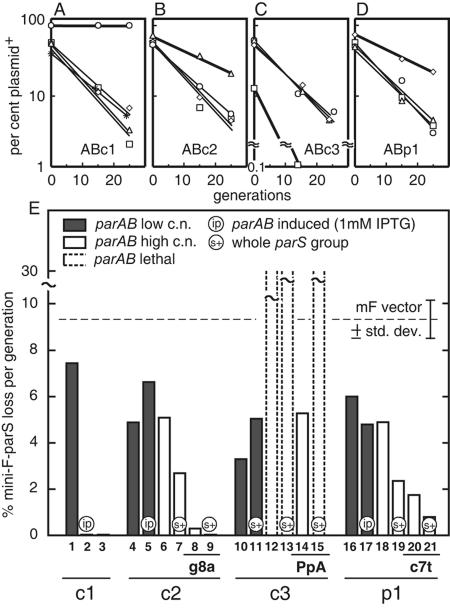

Partition activity of parABS systems.

To assess partition function, we examined the ability of parAB expressed from plac on a multicopy vector to stabilize mini-F plasmids carrying single parS or parS-like sites in E. coli. This foreign-host assay has been used previously to demonstrate the stabilization capacity of the B. subtilis soj-spo0J-parS and the P. putida parABS systems (10, 52). As an initial approach, it is preferable to one employing B. cenocepacia itself in that it avoids the complications of incompatibility with the resident replicons and of possible pleiotropy of parAB mutants (which we have not yet isolated). Figure 4A to D shows the effects of producing ParA and ParB proteins without IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction on the loss of mini-F-parS plasmids during ∼25 generations of exponential growth. In each case, mini-F-parS responded only to its own parAB module, with noncognate parS plasmids being lost at rates not significantly different from that of pDAG203, the original mini-F vector (∼9% per generation). The parABS systems are thus specific.

FIG. 4.

Partition activity of B. cenocepacia parABS elements in E. coli. Shown is the effect of pBBRmcs5 carrying parAB of (A) c1, (B) c2, (C) c3, or (D) p1 on the loss rates of mini-F vector pDAG203 carrying a single parS-like unit of c1 (○), c2 (▵), c3 (□), p1 (⋄), or none (* [shown only in A]). Slight differences in slope, e.g., parS of c2 and p1 in A, are not significant. The y axis in C is broken to accommodate the accelerated loss of the c3 parS plasmid caused by its own ParAB. (E) Effects of modifying parAB and parS elements on mini-F stabilization. Empty and shaded bars show loss rates for plac-parAB at high (pBBRmcs5) and low (pAM238) copy numbers (c.n.), respectively; dotted-line bars indicate that growth with selection for the mini-F was so perturbed and variable that loss rates could not be reproducibly measured; the horizontal dotted line shows the spontaneous loss rate of the mini-F vector; below the bar numbers, mutations in parS* (g8a), parB promoter in parA (PpA), and parS (c7t) are shown. Variability of loss rate was ≤18% (standard deviation). Cognate ParAB-parS interactions shown by thicker lines in A to D are represented by columns 3, 6, 12, and 18, respectively.

The nature of the stability change varied, however: parAB of c1 conferred complete stability on mini-F carrying c1 parS, parAB of c2 and p1 increased stability of their mini-Fs only modestly, and parAB of c3 strongly destabilized the mini-F carrying its parS-like site. Suspecting that this destabilization resulted from an oversupply of the Par proteins, we repeated the tests using an expression vector with a ∼4-fold-lower copy number (Fig. 4E, shaded bars). Reducing the c3 parAB gene dosage eliminated destabilization and actually improved the stability of its mini-F-parS about threefold relative to that of pDAG203 (Fig 4E, bar 10). Thus, all the parAB loci can increase the stability of their cognate parS plasmids. The palindromes found in c2, c3, and p1 can be considered true parS sites, and their parABS ensembles can be considered genuine partition systems.

The other replicons showed various responses to lowered ParAB levels. Stability of the c1 mini-F-parS (Fig. 4E, bar 3) was almost completely lost at a low parAB copy number (bar1) but was restored upon induction of parAB expression with IPTG (bar 2), presumably because the B. cenocepacia sequence upstream of parA in the ParAB producer plasmid does not contain an E. coli promoter. In contrast, the modest stabilizing effect of the c2 and p1 proteins (bars 6 and 18) was essentially unaffected by the induction of their parABs or the reduction their copy number (bars 4 and 5 and 16 and 17, respectively), reflecting the presence of promoters in the upstream B. cenocepacia sequences; some factor other than parAB copy number or ParAB concentration appears to limit stabilization in these cases.

Inefficiency of a single parS site relative to its cluster was one such factor. Repeating the tests with mini-F plasmids carrying entire parS clusters resulted in a twofold reduction in the loss rate for c2 and p1 (Fig. 4E, bars 6 and 7 and 18 and 19, respectively). Again, the c3 system was different; its parS cluster aggravated destabilization (bars 11 and 13). Functional motifs internal to the parAB operons, the parS-like sites near the 5′ end of c2 and p1 parB and a predicted promoter in the c3 parA gene (Fig. 1), also appeared to be potential influences on stabilization capacity. Silent mutations in the conserved central positions of the extra parS sites improved stabilization by the resulting parAB loci (Fig. 4E, bars 8 and 20) and improved it still further when coupled with mini-Fs carrying full parS clusters (bars 9 and 21), providing essentially complete stability in the case of c2. The mutated c2 parAB continued to stabilize after reinsertion of the normal parS* at an ectopic site (data not shown), indicating that centromere-based incompatibility had not been responsible for the limited stabilization. Mutation of the promoter in c3 parA abolished the destabilization of the single parS mini-F (bar 14) but was insufficient to stabilize the parS cluster plasmid (bar 15). No effect on noncognate parS plasmid stability was observed in tests with the more efficient mutant parAB loci (data not shown).

The beneficial effects of these mutations on partition activity suggested that the motifs in question might normally be used to regulate partition through the modulation of parAB expression. One way in which they might do this is through ParB-mediated silencing: partition complexes of several plasmids are known to be able to further recruit molecules of their centromere-binding protein and so spread along neighboring DNA, silencing it (53).

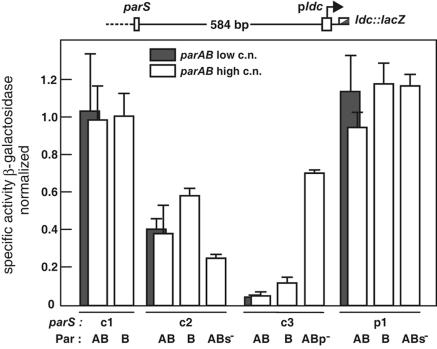

Silencing by the Par proteins.

To assess the silencing capacity of the B. cenocepacia Par proteins, we inserted each of the parS sites upstream of an E. coli ldc promoter-lacZ fusion integrated at attλ and measured the effect of ParB, with and without ParA, on β-galactosidase synthesis (Fig. 5). The c2 and c3 ParB proteins reduced lacZ expression about 1.7- and 8-fold, respectively, and reduced it slightly more in the presence of ParA. No silencing was seen in strains carrying noncognate parS sites (data not shown). The lowered expression did not alter significantly following a ∼4-fold decrease in parAB copy number (Fig. 5, shaded bars), implying that variation in silencing among the parABS systems results less from limitations in protein supply than from differences in the properties of ParB proteins. Nevertheless, the moderate increase in silencing that occurred upon mutating the parS site in c2 parAB could reflect an increased availability of ParB once a competing site has gone, and the reduction in silencing by c3 parAB mutated at the internal promoter presumably results from the decreased synthesis of c3 ParB protein. Although these interpretations must remain provisional pending a direct measurement of protein concentrations, the results suggest that silencing by ParB could play an autoregulatory role in the functioning of the c2 and c3 partition systems.

FIG. 5.

parABS-mediated silencing. Exponential-phase cultures of strains carrying parAB on a plasmid and a parS-pldc::lacZ module in an integrated λ prophage were assayed for β-galactosidase, and specific activities were normalized to those of the same strains without parAB (∼250 Miller units). Error bars are standard deviations. ABs− and ABp− carry the mutations shown in Fig. 4.

DISCUSSION

Species of the genus Burkholderia are notable for the breadth of their physiology and habitat (36). It is reasonable to assume, in view of their relatively large genomes, that they have achieved this versatility through the addition of new genetic material to the basic genome needed for a free-living existence. While imported DNA could in principle be accommodated by integration into the chromosome, it is clear that Burkholderia spp. have opted for keeping it on separate replicons. This choice can be expected to place extra demands on the mechanism that ensures orderly segregation, especially since three of the replicons are large enough to qualify as chromosomes. Our results show that each B. cenocepacia replicon harbors a single parAB locus and a group of parS centromere sites, that each parABS set can partition an unstable plasmid vector, and that each parAB functions only with the parS of its own replicon. These parABS systems thus have the potential to confer specificity and direction to the partition process in their mother organism. How this potential is realized should become evident from future studies based on parAB mutants of B. cenocepacia.

Of the three strategies for managing chromosome segregation that we considered, B. cenocepacia appears to have adopted independent action of ParAB proteins at individualized parS clusters in preference to collective partition by a single master parAB locus. Coordinated partition by cross-reaction among parABS systems is not entirely ruled out, because we have not yet measured the ability of B. cenocepacia ParA proteins to stabilize through the interaction with noncognate ParBs. However, in other ParB family proteins, it is the amino acids of a relatively unstructured N terminus that determine the specificity of interaction with ParAs (32, 44, 45, 49). If the same is true for B. cenocepacia ParBs, the dissimilarity of their N-terminal primary sequences (not shown) suggests that noncognate ParA-ParB interactions are unlikely to occur. A possibility of another type, which we have not investigated here, is the prevention of ori/par region interference by localization at distinct and specific intracellular sites. The origins of the two chromosomes of Vibrio cholerae were clearly seen to occupy distinct locations (6), whereas the separation of the Sinorhizobium meliloti chromosome and megaplasmid origins appeared less clear cut (22). The involvement of parABS systems in the positioning of these origins has not been reported.

Our conclusions are based on the use of E. coli to test the function of exotic partition systems. This raises the issue of their relevance to behavior in their natural Burkholderia host. The c1 and modified c2 parABS systems stabilize mini-F as effectively as the vector's own system (sop). This observation directly demonstrates their independence of host-specific partition factors, thus removing the doubt on this issue which previous reports of partial stabilization (2, 10, 52) had allowed to persist. Participation of the host must either be at a general level, via the membrane or the nucleoid, for example, or involve a structurally conserved factor such as the bacterial actin MreB (9, 25, 37). The weak partition activity of the unmodified c2, c3, and p1 systems may be partly a consequence of intrinsic inefficiency, sensed even in Burkholderia, whereas the efficient c1 parAB is normally supplemented with only two isolated parS sites, and those of c2, c3, and p1 are accompanied by three to four nearby parS sites in a clustered arrangement which may serve to compensate for a lower effectiveness of its protein partners. On the other hand, the finding that mutations expected to alter Par protein supply enhanced stabilization by the c2, c3, and p1 systems suggests that imbalances in Par protein levels interfere with partition in E. coli, as previously observed for plasmid systems (7, 19, 26), and points to the existence of host-specific regulatory mechanisms. Regulation of chromosomal parABS systems, at any level, has not been described. The presence of parS sites or promoters internal to the B. cenocepacia parAB operons (Fig. 1) and the ability of c2 and c3 ParB proteins to silence a nearby promoter suggest that there are mechanisms for autoregulating Par protein production that are distinct from the classic promoter repression mode of autoregulation described so far for parAB operons. Such possibilities will be best explored in B. cenocepacia itself, where the full complement of relevant regulators is present.

A characteristic that has united all genomes with parABS systems described to date is the virtual identity of the parS sites found on their chromosomes (34). Moreover, these sites had not been seen in smaller chromosomes and plasmids. It was therefore surprising to find that the secondary replicons of B. cenocepacia contain parS elements whose sequence is distinct from but strongly resembles that of the principal parS, a 14- to 16-bp palindrome with a 5′-CG-3′ center and no spacer. These parS sites exhibit some notable features. They are present, and function better, as clusters rather than as dispersed copies typical of the arrangement of the canonical parS. The c2 parS is also found in the secondary chromosomes of other Burkholderia species (Fig. 2), but we found no examples of these parSs in other multipartite genomes outside the Burkholderia group (the secondary replicon of the closely related Ralstonia solenacearum carries its own, similar parS). Also striking is that the p1 replicon, which in other respects is a typical conjugative plasmid, carries a parS whose uninterrupted palindrome structure and general sequence relate it more closely to the canonical chromosome parS than to any known plasmid centromere. Any type of plasmid centromere should have sufficed if replicon compatibility were the only issue. It is possible that certain types of parS sites, or parS-ParB partners, function better than others in Burkholderia species and are therefore preferentially established upon entry into the cell. The replicons carrying this kind of parS would then, by accretion of DNA from the chromosome or from further imports and by suitable reorganization, become secondary chromosomes. The p1 plasmid might be in the initial stages of this process, as witnessed by the possible beginnings of a GC skew (Fig. 1). The smaller of the two chromosomes in the other Burkholderia genomes characterized, Burkholderia pseudomallei (16) and Burkholderia mallei (40), possesses parABS systems very similar to that of B. cenocepacia c2, including an identical parS (Fig. 3), suggesting that these species are following the evolutionary track already traveled by B. cenocepacia. The phylogenetic distinction between c1 ParA and ParB proteins and those of the other replicons support this view. The second chromosome of Vibrio cholerae also betrays a plasmid ancestor through the phylogeny of its ParA (48) as well as by the nature of its replication origin (5). In examining partition in B. cenocepacia itself, we not only might come to understand the role of the parABS systems in the mechanism but might also gain insight into the evolution of the multichromosome state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Annie Godfrin-Estevenon, Jérôme Rech, Jérôme Castandet, Katja Müeller, and Sif-Allah Touil for their contributions to this project and other members of the Dynamique des Réplicons Bactériens group for discussions.

This project was financed by the soutien de base du LMGM and by a Bonus Qualité Recherche de l'Université Paul Sabatier.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barilla, D., M. F. Rosenberg, U. Nobbmann, and F. Hayes. 2005. Bacterial DNA segregation dynamics mediated by the polymerizing protein ParF. EMBO J. 24:1453-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartosik, A. A., K. Lasocki, J. Mierzejewska, C. M. Thomas, and G. Jagura-Burdzy. 2004. ParB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interactions with its partner ParA and its target parS and specific effects on bacterial growth. J. Bacteriol. 186:6983-6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates, D., and N. Kleckner. 2005. Chromosome and replisome dynamics in E. coli: loss of sister cohesion triggers global chromosome movement and mediates chromosome segregation. Cell 121:899-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138:179-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan, E. S., and M. K. Waldor. 2003. Distinct replication requirements for the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Cell 114:521-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fogel, M. A., and M. K. Waldor. 2005. Distinct segregation dynamics of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 55:125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funnell, B. E. 1988. Mini-P1 plasmid partitioning: excess ParB protein destabilizes plasmids containing the centromere parS. J. Bacteriol. 170:954-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gil, D. 1990. Elaboration et caractérisation d'un nouveau type de vecteur de clonage à nombre de copies régulable. PhD thesis. Université de Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France.

- 9.Gitai, Z., N. A. Dye, A. Reisenauer, M. Wachi, and L. Shapiro. 2005. MreB actin-mediated segregation of a specific region of a bacterial chromosome. Cell 120:329-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godfrin-Estevenon, A. M., F. Pasta, and D. Lane. 2002. The parAB gene products of Pseudomonas putida exhibit partition activity in both P. putida and Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 43:39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golovanov, A. P., D. Barilla, M. Golovanova, F. Hayes, and L. Y. Lian. 2003. ParG, a protein required for active partition of bacterial plasmids, has a dimeric ribbon-helix-helix structure. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1141-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon, G. S., R. P. Shivers, and A. Wright. 2002. Polar localization of the Escherichia coli oriC region is independent of the site of replication initiation. Mol. Microbiol. 44:501-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant, S. G., J. Jessee, F. R. Bloom, and D. Hanahan. 1990. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4645-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graumann, P. L. 2000. Bacillus subtilis SMC is required for proper arrangement of the chromosome and for efficient segregation of replication termini but not for bipolar movement of newly duplicated origin regions. J. Bacteriol. 182:6463-6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiraga, S. 2000. Dynamic localization of bacterial and plasmid chromosomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34:21-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden, M. T., R. W. Titball, S. J. Peacock, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, T. Atkins, L. C. Crossman, T. Pitt, C. Churcher, K. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. Sebaihia, N. R. Thomson, N. Bason, I. R. Beacham, K. Brooks, K. A. Brown, N. F. Brown, G. L. Challis, I. Cherevach, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, B. Crossett, P. Davis, D. DeShazer, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, Z. Hance, H. Hauser, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, K. E. Keith, M. Maddison, S. Moule, C. Price, M. A. Quail, E. Rabbinowitsch, K. Rutherford, M. Sanders, M. Simmonds, S. Songsivilai, K. Stevens, S. Tumapa, M. Vesaratchavest, S. Whitehead, C. Yeats, B. G. Barrell, P. C. Oyston, and J. Parkhill. 2004. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14240-14245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ireton, K., N. W. Gunther IV, and A. D. Grossman. 1994. spo0J is required for normal chromosome segregation as well as the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:5320-5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakimowicz, D., K. Chater, and J. Zakrzewska-Czerwinska. 2002. The ParB protein of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) recognizes a cluster of parS sequences within the origin-proximal region of the linear chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1365-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen, R. B., M. Dam, and K. Gerdes. 1994. Partitioning of plasmid R1. The parA operon is autoregulated by ParR and its transcription is highly stimulated by a downstream activating element. J. Mol. Biol. 236:1299-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, L. J., R. Carballido-Lopez, and J. Errington. 2001. Control of cell shape in bacteria: helical, actin-like filaments in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 104:913-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadoya, R., A. K. Hassan, Y. Kasahara, N. Ogasawara, and S. Moriya. 2002. Two separate DNA sequences within oriC participate in accurate chromosome segregation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 45:73-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahng, L. S., and L. Shapiro. 2003. Polar localization of replicon origins in the multipartite genomes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 185:3384-3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalnin, K., S. Stegalkina, and M. Yarmolinsky. 2000. pTAR-encoded proteins in plasmid partitioning. J. Bacteriol. 182:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruse, T., J. Moller-Jensen, A. Lobner-Olesen, and K. Gerdes. 2003. Dysfunctional MreB inhibits chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 22:5283-5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusukawa, N., H. Mori, A. Kondo, and S. Hiraga. 1987. Partitioning of the F plasmid: overproduction of an essential protein for partition inhibits plasmid maintenance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 208:365-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane, D., J. Cavaille, and M. Chandler. 1994. Induction of the SOS response by IS1 transposase. J. Mol. Biol. 242:339-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, P. S., D. C. Lin, S. Moriya, and A. D. Grossman. 2003. Effects of the chromosome partitioning protein Spo0J (ParB) on oriC positioning and replication initiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 185:1326-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemon, K. P., and A. D. Grossman. 2000. Movement of replicating DNA through a stationary replisome. Mol. Cell 6:1321-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemonnier, M., J. Y. Bouet, V. Libante, and D. Lane. 2000. Disruption of the F plasmid partition complex in vivo by partition protein SopA. Mol. Microbiol. 38:493-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemonnier, M., and D. Lane. 1998. Expression of the second lysine decarboxylase gene of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 144:751-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonard, T. A., P. J. Butler, and J. Lowe. 2005. Bacterial chromosome segregation: structure and DNA binding of the Soj dimer—a conserved biological switch. EMBO J. 24:270-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis, R. A., C. R. Bignell, W. Zeng, A. C. Jones, and C. M. Thomas. 2002. Chromosome loss from par mutants of Pseudomonas putida depends on growth medium and phase of growth. Microbiology 148:537-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin, D. C., and A. D. Grossman. 1998. Identification and characterization of a bacterial chromosome partitioning site. Cell 92:675-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobry, J. R. 1996. A simple vectorial representation of DNA sequences for the detection of replication origins in bacteria. Biochimie 78:323-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. A. Urban, and J. B. Goldberg. 2005. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:144-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolin, W. 2005. Bacterial mitosis: actin in a new role at the origin. Curr. Biol. 15:R259-R261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohl, D. A., J. Easter, Jr., and J. W. Gober. 2001. The chromosome partitioning protein, ParB, is required for cytokinesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 42:741-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mysliwiec, T. H., J. Errington, A. B. Vaidya, and M. G. Bramucci. 1991. The Bacillus subtilis spo0J gene: evidence for involvement in catabolite repression of sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 173:1911-1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nierman, W. C., D. DeShazer, H. S. Kim, H. Tettelin, K. E. Nelson, T. Feldblyum, R. L. Ulrich, C. M. Ronning, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, T. D. Davidsen, R. T. Deboy, G. Dimitrov, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. L. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, H. Khouri, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, Y. Mohammoud, W. C. Nelson, D. Radune, C. M. Romero, S. Sarria, J. Selengut, C. Shamblin, S. A. Sullivan, O. White, Y. Yu, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. Structural flexibility in the Burkholderia mallei genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14246-14251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niki, H., R. Imamura, M. Kitaoka, K. Yamanaka, T. Ogura, and S. Hiraga. 1992. E. coli MukB protein involved in chromosome partition forms a homodimer with a rod-and-hinge structure having DNA binding and ATP/GTP binding activities. EMBO J. 11:5101-5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogasawara, N., and H. Yoshikawa. 1992. Genes and their organization in the replication origin region of the bacterial chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 6:629-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piggot, P. J., and J. G. Coote. 1976. Genetic aspects of bacterial endospore formation. Bacteriol. Rev. 40:908-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radnedge, L., B. Youngren, M. Davis, and S. Austin. 1998. Probing the structure of complex macromolecular interactions by homolog specificity scanning: the P1 and P7 plasmid partition systems. EMBO J. 17:6076-6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ravin, N. V., J. Rech, and D. Lane. 2003. Mapping of functional domains in F plasmid partition proteins reveals a bipartite SopB-recognition domain in SopA. J. Mol. Biol. 329:875-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rost, B., G. Yachdav, and J. Liu. 2004. The PredictProtein Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W321-W326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sunako, Y., T. Onogi, and S. Hiraga. 2001. Sister chromosome cohesion of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1233-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Surtees, J. A., and B. E. Funnell. 1999. P1 ParB domain structure includes two independent multimerization domains. J. Bacteriol. 181:5898-5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webb, C. D., P. L. Graumann, J. A. Kahana, A. A. Teleman, P. A. Silver, and R. Losick. 1998. Use of time-lapse microscopy to visualize rapid movement of the replication origin region of the chromosome during the cell cycle in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:883-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woldringh, C. L. 2002. The role of co-transcriptional translation and protein translocation (transertion) in bacterial chromosome segregation. Mol. Microbiol. 45:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaichi, Y., and H. Niki. 2000. Active segregation by the Bacillus subtilis partitioning system in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14656-14661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yarmolinsky, M. 2000. Transcriptional silencing in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.