Abstract

Permeabilized rat soleus muscle fibers were subjected to rapid shortening/restretch protocols (20% muscle length, 20 ms duration) in solutions with pCa values ranging from 6.5 to 4.5. Force redeveloped after each restretch but temporarily exceeded the steady-state isometric tension reaching a maximum value ∼2.5 s after relengthening. The relative size of the overshoot was <5% in pCa 6.5 and pCa 4.5 solutions but equaled 17% ± 4% at pCa 6.0 (approximately half-maximal Ca2+ activation). Muscle stiffness was estimated during pCa 6.0 activations by imposing length steps at different time intervals after repeated shortening/restretch perturbations. Relative stiffness and relative tension were correlated (p < 0.001) during recovery, suggesting that tension overshoots reflect a temporary increase in the number of attached cross-bridges. Rates of tension recovery (ktr) correlated (p < 0.001) with the relative residual force prevailing immediately after restretch. Force also recovered to the isometric value more quickly at 5.7 ≤ pCa ≤ 5.9 than at pCa 4.5 (ANOVA, p < 0.05). These results show that ktr measurements underestimate the rate of isometric force development during submaximal Ca2+ activations and suggest that the rate of tension recovery is limited primarily by the availability of actin binding sites.

INTRODUCTION

How quickly do cross-bridges generate force? One way of answering this important question is to measure the rate constants for each kinetic step in the cross-bridge cycle using solution chemistry techniques (reviewed by Howard (1)). Such experiments have provided much useful information over the years but cannot assess the importance of mechanical stress or geometrical constraints imposed by the filament lattice.

An alternative strategy is to measure the rate of force generation in an isolated muscle fiber. The obvious technique is to measure the rate of force development at the beginning of an isometric contraction, but this method cannot distinguish between the rate at which the cross-bridges generate force and the rate at which the contractile apparatus is activated. Experiments using permeabilized fibers are further complicated because of uncertainty in the time required for the myofibrilar free Ca2+ concentration to reach steady state (2).

Brenner (3) showed that it was possible to circumvent these issues by measuring the kinetics of force generation in chemically permeabilized fibers during sustained Ca2+-activated contractures. He argued that if the muscle was allowed to shorten and then rapidly restretched, the rate constant of force redevelopment kredev should equal the sum of the apparent rate constants fapp and gapp for cross-bridge attachment and detachment, respectively.

Brenner's analytical method has proved exceptionally useful (see review by Gordon et al. (4)), but in reality many experimental records deviate from the single exponential form predicted by his two-state model. Tension recovery in rabbit psoas fibers for instance is often more closely approximated by the sum of two exponential components than by a single exponential function (5,6). The recent work of Burton et al. (7) includes detailed examples.

Another type of deviation occurs when tension temporarily exceeds the steady-state value during recovery before declining back to the original isometric level. Such tension “overshoots” appear to be a general feature of tension recovery measurements. They are evident in published records from more than one research group (7–9) and have been observed using 1), permeabilized slow skeletal preparations (rat soleus fibers) (10), 2), permeabilized fast skeletal preparations (rabbit psoas fibers) (6–9), and 3), permeabilized cardiac preparations from rats, dogs, and pigs (K. S. Campbell, unpublished observations). The published records of Fitzsimons et al. (11) show that tension can also overshoot its steady-state value after photo-release of caged Ca2+ at fixed muscle length. This is an important finding because it shows that tension overshoots can occur during isometric force development not preceded by stretch.

Although tension overshoots were described in abstract form in 1993 (12) they do not appear to have been systematically examined before now. One reason they have not received further attention could be that most published figures illustrating tension recovery records show only a small portion of the return to steady state (see for example McDonald et al. (8)). This style of presentation minimizes the visual impact of the overshoot because the decline back to steady-state force is not apparent.

This work presents an analysis of tension overshoots observed in experiments utilizing permeabilized rat soleus fibers. The measurements demonstrate that the temporary increase in muscle force is accompanied by a comparable increase in fiber stiffness. Two additional novel findings are that 1), tension first reaches its steady-state value more quickly at submaximal levels of Ca2+ activation than in saturating Ca2+ solutions, and that 2), the rate of tension recovery correlates with the relative residual force prevailing immediately after restretch.

METHODS

Preparations

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (150 g) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1 body weight) and subsequently killed by surgical excision of the heart. The soleus muscles were isolated, and bundles of ∼20 fibers were chemically permeabilized and stored as described (10). Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky.

Mechanical measurements

Segments of individual muscle fibers (length (l0) 1000 ± 30 μm, sarcomere length 2.59 ± 0.05 μm, cross sectional area (estimated assuming a circular profile) 6550 ± 3940 μm2, measurements performed in pCa (= −log10[Ca2+]) 9.0 solution, n = 24) were attached between a force transducer and a motor (312B, Aurora Scientific, Aurora, Ontario, Canada, step time 0.6 ms) as illustrated in Fig. 1 of Campbell and Moss (10). The experiments illustrated in Figs. 1 and 3–6 were performed using a commercially available force transducer (403, Aurora, resonant frequency 600 Hz). The measurements reported in Figs. 7–9 required a force transducer with a higher frequency response and utilized a silicon strain-gauge sensor (AE801, SensorOne Technologies, Sausalito, CA, resonant frequency 6.5 kHz). Additional mechanical damping (provided by a drop of light machine oil applied between the back of the sensor element and an adjacent end-stop) minimized inappropriate beam oscillation after rapid changes in muscle length.

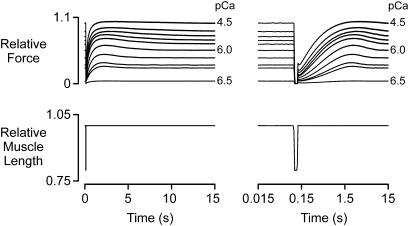

FIGURE 1.

Sarcomere length control. Force, sarcomere length, and muscle length records from a representative experiment. pCa 6.0. Steady-state force (Pss) was 0.48 of maximally Ca2+-activated tension (P0). Measured sarcomere length was held constant after restretch (SL control) in the second trial (shaded traces) using SLControl software (13). The left-hand panels are plotted using a conventional linear time axis. The right-hand panels are plotted using a logarithmic axis to clarify the muscle's behavior immediately after restretch. The horizontal dashed lines in the top panels indicate Pss.

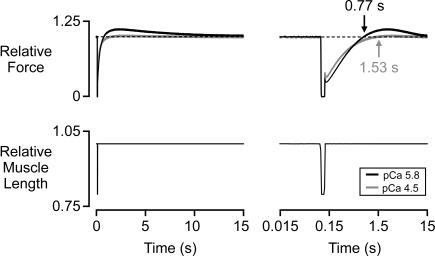

FIGURE 3.

Records obtained at different levels of Ca2+ activation. Superposed force and muscle length records (plotted on linear and logarithmic time axes for clarity) for a fiber subjected to the same rapid shortening/restretch protocol in each of 10 solutions. pCa values ranged from 6.5 (very low Ca2+ activation) to 4.5 (maximal activation). pCa 9.0 traces were recorded for each experiment but are omitted from this figure because Pss under these conditions was <1% of P0. Force records are normalized to P0.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of collated data. Symbols show mean ± SD (n = 10 fibers) for each parameter for an individual pCa value. (A) Relative Ca2+-activated tension (Pss/P0). Solid line is a best fit of the form  . (B) ktr values (defined as in Fig. 2). (C) Pmax/Pss (Fig. 2). The dashed line indicates a ratio of unity, i.e., no tension overshoot. Pmax/Pss was greater (ANOVA, Tukey multiple comparison test, p < 0.01) in pCa 6.0 solution (Pss/P0 = 0.55 ± 0.04) than during either pCa 6.5 (Pss/P0 = 0.05 ± 0.02) or pCa 4.5 (Pss/P0 ≡ 1) activations. (D) Crossing time tct (Fig. 2). Stars indicate the predicted tct values (−ln(0.03)/ktr) if tension recovered with an exponential time course and did not overshoot Pss.

. (B) ktr values (defined as in Fig. 2). (C) Pmax/Pss (Fig. 2). The dashed line indicates a ratio of unity, i.e., no tension overshoot. Pmax/Pss was greater (ANOVA, Tukey multiple comparison test, p < 0.01) in pCa 6.0 solution (Pss/P0 = 0.55 ± 0.04) than during either pCa 6.5 (Pss/P0 = 0.05 ± 0.02) or pCa 4.5 (Pss/P0 ≡ 1) activations. (D) Crossing time tct (Fig. 2). Stars indicate the predicted tct values (−ln(0.03)/ktr) if tension recovered with an exponential time course and did not overshoot Pss.

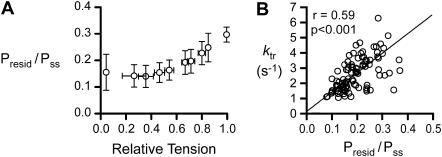

FIGURE 5.

Recovery times. Superposed force and muscle length records (shown on both linear and logarithmic timescales) for a fiber subjected to the same length perturbation in pCa 5.8 (Pss/P0 = 0.74) and pCa 4.5 solutions. Both force records are normalized to their respective steady-state values. Force reached Pss 0.77 s after the start of the record (0.65 s after restretch) in pCa 5.8 solution. This was 0.76 s earlier than the corresponding transition point in pCa 4.5 solution.

FIGURE 6.

Residual forces. (A) Presid/Pss (Fig. 2) plotted as a function of relative tension (Pss/P0). (B) ktr plotted against Presid/Pss. The solid line is a robust fit minimizing the absolute deviation between the experimental values and a linear model. (This technique is more appropriate than linear regression for experimental data with uncertainty in two dimensions (35).) ktr and Presid/Pss are correlated.

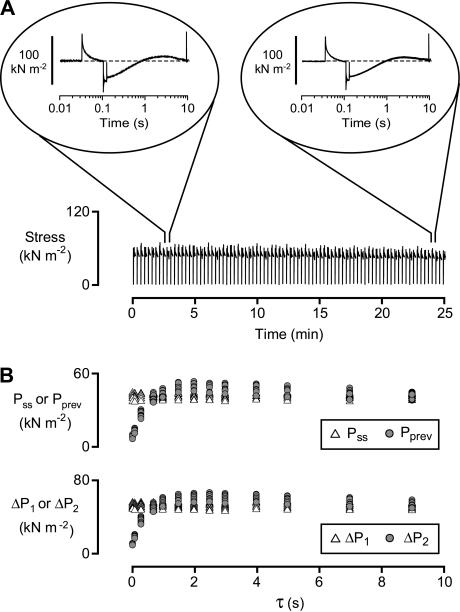

FIGURE 7.

Length step protocol. Force, sarcomere length, and muscle length records from a representative experiment. pCa 6.0. Pss/P0 = 0.50. The first step length change always occurred 60 ms before the shortening/restretch perturbation. τ varied between preset values ranging from 30 ms to 13 s in successive trials. Pprev is the prevailing tension immediately before the second step length change. Insets show force and sarcomere length traces on an expanded timescale. ΔP1 and ΔP2 are the force changes resulting from the first and second steps, respectively.

FIGURE 8.

Stability of the fiber preparation. (A) Slow time base recording of force during a prolonged activation in pCa 6.0 solution. Pss/P0 ∼ 0.55. Insets show force records for the 10th and 75th trials on an expanded (logarithmic) timescale. τ = 9 s for both trials. (B) Values of Pss, Pprev (top panel), and ΔP1, ΔP2 (bottom panel) calculated for each trial from the experiment shown in panel A. Pss and ΔP1 do not vary with the recovery time τ but are plotted aligned with their corresponding Pprev and ΔP2 values to enhance clarity.

FIGURE 9.

Relative stiffness and relative tension. (A) Pprev/Pss and ΔP2/ΔP1 values plotted as a function of the recovery time τ on linear (left-hand) and logarithmic (right-hand) axes. Each symbol indicates the mean ± SD of the appropriate ratio calculated from seven separate experiments using different muscle fibers. (B) ΔP2/ΔP1 values plotted as a function of Pprev/Pss. In this plot, each symbol represents the mean value observed at a single recovery time for a single fiber (n = 7 fibers). The solid line is a regression line constrained to pass through the origin.

Real-time measurement of sarcomere length was accomplished by projecting a HeNe laser beam through the central 0.5 mm segment of each fiber preparation and monitoring the position of a first-order diffraction line incident on a lateral effects photodiode detector (Model 1239 detector, 301-DIV amplifier, bandwidth 5 kHz, UDT Instruments, Baltimore, MD). Signals representing force, sarcomere length, and motor position (indicative of muscle length) were sampled at fixed rates of between 2 and 25 kHz depending on the experimental protocol and saved to computer files using SLControl software (http://www.slcontrol.com). Sarcomere length control was implemented in the experiments illustrated in Fig. 1 by updating the motor command voltage at 0.5 ms intervals in such a way as to minimize measured changes in sarcomere length. Full details of the feedback algorithm have been published (13).

Subsequent analysis utilized custom-written MATLAB routines (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Results are reported as mean ± SD. The steady-state isometric tension measured in pCa 9.0 solution was subtracted from each Presid value (defined as in Fig. 2) to correct for passive elastic properties.

FIGURE 2.

Definitions. Schematic traces of force and muscle length plotted using linear (left-hand panels) and logarithmic (right-hand panels) time axes. Annotations define steady-state isometric force (Pss), the residual force prevailing immediately after restretch (Presid), and the maximum force attained in the 5 s period after the length perturbation (Pmax). tct (the “crossing time”) is a measure of how long the muscle takes to regenerate Pss. In records where there is no clear tension overshoot, force approaches Pss asymptotically and the exact time at which force reaches Pss cannot be precisely determined. To overcome this difficulty, tct is defined in this work as the time required for force to rise from Presid to 0.97 Pss. ktr values were calculated as −ln(½)/(t½), where t½ is the time required for force to rise from Presid to ½ (Pmax + Presid). Similar experimental trends were observed in a comparable rate constant calculated by fitting a single exponential function to each force trace during the tmax interval. These values were, however, ∼0.1 s−1 slower than the ktr values calculated as above.

Solutions (pH 7.0) with pCa values ranging from 9.0 (1 nM free Ca2+) to 4.5 (32 μM free Ca2+) were prepared as described (10). All experiments were performed at 15°C. Steady-state isometric force in pCa 4.5 solution (P0) was 79 ± 29 kN m−2. pCa 9.0 steady-state tension averaged 0.006 ± 0.004 of P0.

RESULTS

When permeabilized muscle preparations are subjected to a rapid shortening/restretch protocol (0.2 l0, 20 ms duration), tension can temporarily exceed (or overshoot) the steady-state isometric value during the recovery process. Fig. 1 illustrates an experiment designed to test whether the overshoot arises as a result of series compliance in the muscle attachments.

The figure shows recordings of force, sarcomere length, and muscle length for two successive trials imposed during a prolonged contraction in submaximally activating pCa 6.0 solution. In the first trial (black traces), the motor was held at a fixed position after restretch (muscle length (ML) control). In the second trial (shaded traces, sarcomere length (SL) control), negative feedback was imposed 5 ms after restretch to minimize changes in measured sarcomere length. The magnitudes of the two tension overshoots are not markedly different.

Similar experiments were performed in pCa 6.0 solution using six additional fibers. Pmax/Pss (Fig. 2) averaged 1.14 ± 0.05 in ML control experiments. The corresponding statistic measured under SL control was 1.17 ± 0.06. These values are not significantly different (paired t-test, p > 0.05, n = 7), indicating that the tension overshoot is unlikely to reflect potential extension of the muscle fiber near its attachments.

Fig. 3 presents illustrative recordings from a fiber activated in solutions with different pCa values. The magnitude of the tension overshoot was small in pCa 6.5 and pCa 4.5 solutions but relatively large at Pss/P0 ∼ 0.5. Summary statistics from 10 fibers are shown in Fig. 4.

ktr values increased progressively with the level of Ca2+ activation for Pss/P0 values >0.2 (Fig. 4 B). This result might be interpreted as suggesting that soleus fibers generate force more quickly at higher levels of Ca2+ activation. However tct values (a measure of how long the muscle takes to regenerate Pss after the length perturbation) are lower (ANOVA, Tukey multiple comparison test, p < 0.05) for 5.7 ≤ pCa ≤ 5.9 activations (0.67 ≤ Pss/P0 ≤ 0.80) than in maximally activating pCa 4.5 solution (Fig. 4 D).

Fig. 5 reinforces this point with illustrative recordings. The soleus fiber in this example redeveloped isometric force 0.76 s earlier when immersed in pCa 5.8 solution than at maximal Ca2+ activation. This is despite the fact that ktr equaled 4.6 s−1 in pCa 4.5 solution and only 3.4 s−1 during the submaximal activation.

Presid, the residual force prevailing immediately after restretch (Fig. 2), also varied systematically with the level of Ca2+ activation. Fig. 6 A shows Presid/Pss as a function of relative steady-state isometric tension; Fig. 6 B illustrates the relationship between Presid/Pss and ktr. The two parameters are correlated (p < 0.001).

During tension overshoots at submaximal levels of Ca2+ activation, isometric force is elevated above its steady-state value. In principle this “extra” force could reflect 1), a temporary increase (relative to steady-state conditions) in the number of attached cross-bridges, 2), a temporary increase in the mean force per cross-bridge, or 3), some combination of the two mechanisms.

Fig. 7 illustrates an experimental approach designed to distinguish between these possibilities. Single soleus fibers were activated in pCa 6.0 solution and subjected to repeated trials, each consisting of two 1% step length changes (motor step time 0.6 ms) interposed by a single shortening/restretch perturbation (0.2 l0, 20 ms duration). Recordings lasted for 15 s, after which the fiber was returned to l0 and held at that length for at least 6 s before the next trial was initiated. τ, the time interval from restretch to the second length step, was adjusted between pseudorandomly ordered preset values in successive trials.

Soleus muscle fibers are ideal preparations for this type of experiment because they remain mechanically stable during prolonged activations (see, for example, Fig. 3 of Campbell and Moss (10)). Fig. 8 A shows force traces recorded during a sustained activation which exceeded 25 min in duration. Tension overshoots recorded near the end of the experiment were not noticeably different from those recorded near the beginning of the activation. Calculated values of Pss, Pprev, ΔP1, and ΔP2 (Fig. 7) from each trial are plotted in Fig. 8 B. The values are remarkably consistent given the prolonged nature of the experiment.

Pprev/Pss and ΔP2/ΔP1 ratios are plotted as functions of τ in Fig. 9 A. Both ratios reached maximum values ∼2.5 s after restretch and declined gradually back to unity thereafter. F-tests showed that functions of the form y = α – β × e−γ×τ + δ× e−ɛ×τ, where α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ are all greater than zero fitted both the Pprev/Pss and the ΔP2/ΔP1 parameter plots significantly better than single exponential recoveries (p < 0.001). This result indicates that both ratios significantly exceed their steady-state values during the recovery process.

Fig. 9 B shows that the ratios are also correlated (p < 0.001). Since step sarcomere length changes did not vary with τ (ANOVA, p > 0.05), this result demonstrates that the temporary increase in force observed during the tension overshoot is accompanied by a comparable increase in fiber stiffness.

DISCUSSION

Although tension overshoots have been observed in a wide range of different permeabilized preparations (6–11), they have not been systematically examined before now, to the best of my knowledge. There are at least three reasons why they deserve careful attention.

First, tension overshoots share many similarities with stretch activation responses observed after much smaller length changes (14–17) and may arise from a similar mechanism. Second, during an overshoot muscle's force generating capacity is temporarily increased above its steady-state value. Discovering how this happens increases our understanding of how muscles work. Third, the fact that tension overshoots occur at all has significant implications for measurements of ktr, an important parameter in most models of contractile regulation. This discussion focuses on the second and third points above. Stretch activation is the subject of a recent review by Moore (18).

Underlying mechanism

One possibility before these experiments were carried out was that the temporary elevation in muscle force characteristic of a tension overshoot reflected the development of sarcomere length inhomogeneities during tension recovery (19). Three separate arguments suggest that this is unlikely to be the case: 1), Pmax/Pss ratios during pCa 6.0 activations were unaffected when sarcomere length was held constant after restretch (Fig. 1). 2), Sarcomere length heterogeneity should be greatest at the highest levels of Ca2+ activation, whereas the relative size of the tension overshoot drops at Ca2+ concentrations greater than pCa50 (Fig. 4 C). 3), Since sarcomere length heterogeneities are by definition unstable, they seem unlikely to be capable of producing consistent mechanical behavior during activations sustained in excess of 25 min (Fig. 8).

Neither are overshoots likely to reflect viscoelastic mechanisms due to structural elements such as titin (20,21). Such effects would be greatest at low levels of Ca2+ activation (where passive components form the greatest proportion of measured tension), whereas Pmax/Pss ratios peak at about pCa50. Potential Ca2+-dependent changes in titin stiffness (22) can probably be discounted as well because the tension overshoots occur in fibers immersed in solutions with fixed free Ca2+ concentrations. The most likely alternatives seem to involve some sort of cross-bridge mechanism.

Potential cross-bridge explanations for tension overshoots can be subdivided into three broad categories: those which involve 1), a temporary increase (relative to steady-state conditions) in the number of attached cross-bridges, 2), a temporary increase in the mean force per cross-bridge, and 3), some combination of 1 and 2. The experimental results presented in Fig. 9 suggest that the first explanation, a temporary surfeit of attached cross-bridges ∼2.5 s after rapid shortening and restretch, is the most likely.

This conclusion follows from the fact that ΔP2/ΔP1 (a measure of the muscle's relative stiffness) correlated with Pprev/Pss (the muscle's relative tension) during the recovery process. If instead tension overshoots were to have resulted from a temporary increase in the mean force per cross-bridge, ΔP2/ΔP1 should not have exceeded unity.

Two points require further consideration. The ΔP1 and ΔP2 values (Fig. 7) measured in this work are underestimates of T1 forces (23) which could potentially have been measured using faster instrumentation (length steps complete in ∼0.1 ms as opposed to the 0.6 ms steps used in these experiments). This is a limitation of these experiments, but it is unlikely to have affected the current interpretation. ΔP1 and ΔP2 were not regarded in this study as separate measures of the preparation's “instantaneous” stiffness but instead used to evaluate the muscle's relative stiffness at different time points in the recovery process. Expressing ΔP2 relative to the corresponding ΔP1 value obviates most potential concerns relating to the finite frequency response of the experimental apparatus.

The remaining issue relates to the precise relationship between the ΔP2/ΔP1 ratio and the relative number of attached cross-bridges. Muscle stiffness used to be regarded as a good measure of the number of attached cross-bridges (24), but later measurements of thick and thin filament compliance (25–28) brought the relationship into question. Filament compliance effects can of course be included in stiffness calculations (29), but these approaches inevitably incorporate assumptions about which sections of the sarcomere extend the most. In the absence of definitive evidence, ΔP2/ΔP1 ratios have been assumed in this work to increase with the relative number of attached cross-bridges. This is undoubtedly a simplification but it is probably not wholly inaccurate, particularly at the lower levels of Ca2+ activation at which tension overshoots are most apparent.

One question that has not been addressed in this work is how the temporary increase in attached cross-bridges might occur. There are many possibilities: rapid filament movements might dislodge tropomyosin molecules from their normal positions, cross-bridges bound immediately after restretch could take many seconds to detach from the thin filament, etc. An additional and intriguing possibility is that the overshoot reflects “compliant realignment” of thick and thin filaments (30).

Implications for analysis of ktr measurements

Large shortening/restretch perturbations similar to those used in this work (0.2 l0, 20 ms duration) are commonly used to measure cross-bridge kinetics in permeabilized muscle preparations. The basic technique was developed by Brenner (3) who argued that tension should redevelop after such a perturbation at a rate (kredev) equal to the sum of the apparent cross-bridge attachment (fapp) and detachment (gapp) rate constants.

gapp can be calculated from ATPase measurements and appears to be insensitive to the prevailing free Ca2+ concentration (3). kredev on the other hand increases with the relative level of Ca2+ activation in a wide variety of different muscle preparations (3,5,6,9,31–33). The implication is that cross-bridge attachment is Ca2+ dependent (i.e., fapp increases with the free Ca2+ concentration) though whether this reflects Ca2+ sensitivity of one or more myosin state transitions or an increase in actin binding site availability is uncertain. The field has been reviewed by Gordon et al. (4).

This work analyzes the time course of tension recovery using two separate parameters (Fig. 2). ktr is a rate constant calculated from the time required for force to rise from Presid to ½ (Pmax + Presid). tct is a direct measure of the time required for force to rise from Presid to 97% of Pss. The two parameters would exhibit one-to-one mapping if tension recovered with an exponential time course and did not exceed Pss.

Fig. 4 B shows that ktr values increased progressively for all activations with Pss/P0 values >0.2 (31). tct values in contrast fall significantly below the mean pCa 4.5 value during pCa 5.9, 5.8, and 5.7 activations. The conclusions must be that 1), the ktr and tct parameters are not measures of the same physical processes, and that 2), the ktr parameter underestimates the rate at which soleus fibers redevelop Pss at submaximal levels of Ca2+ activation.

One interpretation of these results is that tct values are dominated by the rates at which cross-bridges attach to and detach from the thin filament near the beginning of the recovery process, whereas the ktr parameter incorporates additional recruitment of a new pool of cycling cross-bridges. This additional pool is only temporarily available at submaximal levels of Ca2+ activation and manifests as a tension overshoot.

Why then does tension not exceed Pss in pCa 4.5 solution? The answer might be that cross-bridges once recruited at maximal Ca2+ activation are not released and continue to contribute to isometric force.

Intact preparations

Although tension overshoots are a common feature of tension recovery measurements performed using permeabilized muscles, they have not yet been reported in intact muscle fibers, to my knowledge. This suggests that the underlying mechanism may be an artifact of the permeabilization process, but an alternative possibility is that overshoots are negligibly small in the intracellular conditions pertaining to a fused tetanus. Tension overshoots are most noticeable in permeabilized soleus fibers at approximately half-maximal Ca2+ activation. This experimental condition is difficult to reproduce in an intact muscle fiber.

Evidence supporting cooperative activation

Fig. 6 B shows that ktr correlated with the Presid/Pss ratio. If this ratio is indicative of the proportion of cross-bridges attached between the filaments immediately after restretch (34), the linear relationship between ktr and Presid/Pss can be explained by a mechanism in which attached cross-bridges activate adjacent actin binding sites through cooperative mechanisms in the thin filament, leading in turn to additional cross-bridge binding.

The low value of the y-intercept in Fig. 6 B indicates that this would be the dominant mechanism in rat soleus fibers and thus that the rate of tension recovery is controlled primarily by the availability of actin binding sites and not by Ca2+ regulation of a cross-bridge state transition.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks D. P. Fitzsimons, M. V. Jones, R. L. Moss, J. R. Patel, J. E. Stelzer (Dept. of Physiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison), and F. H. Andrade (Dept. of Physiology, University of Kentucky) for helpful discussions, and one of the referees for a valuable comment regarding the calculation of Presid. Several pilot experiments for this study were conducted with R. L. Moss at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and reported in Abstract form. A. M. Holbrooke provided technical assistance at the University of Kentucky.

This work was supported by the University of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund.

References

- 1.Howard, J. 2001. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. 234–238.

- 2.Moisescu, D. G. 1976. Kinetics of reaction in calcium-activated skinned muscle fibres. Nature. 262:610–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner, B. 1988. Effect of Ca2+ on cross-bridge turnover kinetics in skinned single rabbit psoas fibers: implications for regulation of muscle contraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:3265–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon, A. M., E. Homsher, and M. Regnier. 2000. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol. Rev. 80:853–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swartz, D. R., and R. L. Moss. 1992. Influence of a strong-binding myosin analogue on calcium-sensitive mechanical properties of skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 267:20497–20506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chase, P. B., D. A. Martyn, and J. D. Hannon. 1994. Isometric force redevelopment of skinned muscle fibers from rabbit activated with and without Ca2+. Biophys. J. 67:1994–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton, K., H. White, and J. Sleep. 2005. Kinetics of muscle contraction and actomyosin NTP hydrolysis from rabbit using a series of metal-nucleotide substrates. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 563:689–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald, K. S., M. R. Wolff, and R. L. Moss. 1997. Sarcomere length dependence of the rate of tension redevelopment and submaximal tension in rat and rabbit skinned skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 501(Pt.3):607–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regnier, M., D. A. Martyn, and P. B. Chase. 1998. Calcium regulation of tension redevelopment kinetics with 2-deoxy-ATP or low [ATP] in rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 74:2005–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell, K. S., and R. L. Moss. 2002. History-dependent mechanical properties of permeabilized rat soleus muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 82:929–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzsimons, D. P., J. R. Patel, and R. L. Moss. 1999. Aging-dependent depression in the kinetics of force development in rat skinned myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 276:H1511–H1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson, L., M. L. Greaser, and R. L. Moss. 1993. Extraction of C-protein eliminates the delayed overshoot of isometric tension due to stretch of mammalian skeletal muscles. Biophys. J. 64:A253. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell, K. S., and R. L. Moss. 2003. SLControl: PC-based data acquisition and analysis for muscle mechanics. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 285:H2857–H2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pringle, J. W. 1978. The Croonian Lecture, 1977. Stretch activation of muscle: function and mechanism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 201:107–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andruchov, O., Y. Wang, O. Andruchova, and S. Galler. 2004. Functional properties of skinned rabbit skeletal and cardiac muscle preparations containing alpha-cardiac myosin heavy chain. Pflugers Arch. 448:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linari, M., M. K. Reedy, M. C. Reedy, V. Lombardi, and G. Piazzesi. 2004. Ca-activation and stretch-activation in insect flight muscle. Biophys. J. 87:1101–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis, J. S., S. Hassanzadeh, S. Winitsky, H. Lin, C. Satorius, R. Vemuri, A. H. Aletras, H. Wen, and N. D. Epstein. 2001. The overall pattern of cardiac contraction depends on a spatial gradient of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation. Cell. 107:631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore, J. R. 2004. Stretch activation: toward a molecular mechanism. In Nature's Versatile Engine: Insect Flight Muscle Inside and Out. J. Vigoreaux, editor. Landes Bioscience, Georgetown, TX. 44–60. In press.

- 19.Julian, F. J., and D. L. Morgan. 1979. The effect on tension of non-uniform distribution of length changes applied to frog muscle fibres. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 293:379–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minajeva, A. V. E., M. Kulke, J. M. Fernandez, and W. A. Linke. 2001. Unfolding of titin domains explains the viscoelastic behavior of skeletal myofibrils. Biophys. J. 80:1442–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulke, M., S. Fujita-Becker, E. Rostkova, C. Neagoe, D. Labeit, D. J. Manstein, M. Gautel, and W. A. Linke. 2001. Interaction between PEVK-titin and actin filaments: origin of a viscous force component in cardiac myofibrils. Circ. Res. 89:874–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labeit, D., K. Watanabe, C. Witt, H. Fujita, Y. Wu, S. Lahmers, T. Funck, S. Labeit, and H. Granzier. 2003. Calcium-dependent molecular spring elements in the giant protein titin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:13716–13721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huxley, A. F., and R. M. Simmons. 1971. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature. 233:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford, L. E., A. F. Huxley, and R. M. Simmons. 1981. The relation between stiffness and filament overlap in stimulated frog muscle fibres. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 311:219–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima, H., A. Ishijima, and T. Yanagida. 1994. Direct measurement of stiffness of single actin filaments with and without tropomyosin by in vitro nanomanipulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:12962–12966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higuchi, H., T. Yanagida, and Y. E. Goldman. 1995. Compliance of thin filaments in skinned fibers of rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 69:1000–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huxley, H. E., A. Stewart, H. Sosa, and T. Irving. 1994. X-ray diffraction measurements of the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments in contracting muscle. Biophys. J. 67:2411–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakabayashi, K., Y. Sugimoto, H. Tanaka, Y. Ueno, Y. Takezawa, and Y. Amemiya. 1994. X-ray diffraction evidence for the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments during muscle contraction. Biophys. J. 67:2422–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linari, M., I. Dobbie, M. Reconditi, N. Koubassova, M. Irving, G. Piazzesi, and V. Lombardi. 1998. The stiffness of skeletal muscle in isometric contraction and rigor: the fraction of myosin heads bound to actin. Biophys. J. 74:2459–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniel, T. L., A. C. Trimble, and P. B. Chase. 1998. Compliant realignment of binding sites in muscle: transient behavior and mechanical tuning. Biophys. J. 74:1611–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metzger, J. M., and R. L. Moss. 1990. Calcium-sensitive cross-bridge transitions in mammalian fast and slow skeletal muscle fibres. Science. 247:1088–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolff, M. R., K. S. McDonald, and R. L. Moss. 1995. Rate of tension development in cardiac muscle varies with level of activator calcium. Circ. Res. 76:154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sweeney, H. L., and J. T. Stull. 1990. Alteration of cross-bridge kinetics by myosin light chain phosphorylation in rabbit skeletal muscle: implications for regulation of actin-myosin interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:414–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sleep, J., M. Irving, and K. Burton. 2005. The ATP hydrolysis and phosphate release steps control the time course of force development in rabbit skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 563:671–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Press, W. H., S. A. Teukolsky, W. T. Vetterling, and B. P. Flannery. 1992. Robust estimation. In Numerical Recipes in C—The Art of Scientific Computing, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 699–706.