Abstract

Cyclosporin A (CsA) is an important drug used to prevent graft rejection in organ transplantations. Its immunosuppressive activity is related to the inhibition of T-cell activation through binding with the proteins Cyclophilin (Cyp) and, subsequently, Calcineurin (CN). In the complex with its target (Cyp), CsA adopts a conformation with all trans peptide bonds and this feature is very important for its pharmacological action. Unfortunately, CsA can cause several side effects, and it can favor the excretion of calcium and magnesium. To evaluate the possible role of conformational effects induced by these two metal ions in the action mechanism of CsA, its complexes with Mg(II) and Ce(III) (the latter as a paramagnetic probe for calcium) have been examined by two-dimensional NMR and relaxation rate analysis. The conformations of the two complexes and of the free form have been determined by restrained molecular dynamics calculations based on the experimentally obtained metal-proton and interproton distances. The findings here ratify the formation of 1:1 complexes of CsA with both Mg(II) and Ce(III), with metal coordination taking place on carbonyl oxygens and substantially altering the peptide structure with respect to the free form, although the residues involved and the resulting conformational changes, including cis-trans conversion of peptide bonds, are different for the two metals.

INTRODUCTION

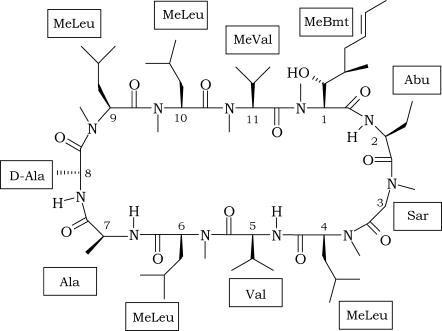

Cyclosporins are a group of cyclic oligopeptides of fungal origin. The most representative element of this family of compounds is Cyclosporin A (CsA), a powerful immunosuppressive drug, isolated for the first time from a soil fungus, Tolypocladium Inflatum, in 1976 (1), which has been extensively used in medicine to prevent graft rejection since 1978 (2). CsA is a neutral molecule containing 11 amino acids, with the following primary structure: MeBmt1-Abu2-Sar3-MeLeu4-Val5-MeLeu6-Ala7-D-Ala8-MeLeu9-MeLeu10-MeVal11 (Scheme 1).

SCHEME 1.

Chemical structure of the CsA molecule.

Many significant features characterize this molecule:

It contains a unique amino acid, MeBmt, which is a derivative of threonine (N-methyl-2-amino-3-idroxy-4-methyl-octa-6-enoic acid). Although MeBmt itself does not posses any bioactivity, any change in its structure greatly affects the immunosuppressive action of CsA (3);

Seven residues are N-methylated on the amide nitrogen, as a consequence of a nonribosomal synthesis, which is typical of fungi and bacteria (4);

The presence of N-methylated amino acids allows higher contents of cis peptide conformations;

The large content of aliphatic residues makes the peptide highly hydrophobic and determines such a low solubility in water (27.67 μg/mL at 25°C) that it is difficult to investigate the behavior of CsA in aqueous solution (5).

The conformation of CsA is widely dependent on the environment. In apolar solvents, such as CHCl3, THF, or CH3CN, one main stable conformer dominates, characterized, in CHCl3, by four stable intramolecular H-bonds involving all the amide hydrogens. These H-bonds cause residues 11–7 to form an antiparallel β-pleated sheet and residues 3–4 a type-II′ β-turn. Moreover one cis peptide bond between MeLeu9 and MeLeu10 is present and all hydrophobic carbon chains are exposed to solvent (6,7). When the polarity of the solvent increases, such as in acetone, dimethylsulfoxide, or MeOH, hydrogen bonds disappear and the structure loses its peculiar rigidity, leading to the coexistence of various stable conformers (7–9).

CsA elicits its immunosuppressive action binding to its intracellular receptor, Cyclophilin (Cyp) (10). In the complex with its target, CsA adopts a different conformation, characterized by a maximal number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the environment and by all trans peptide bonds; this feature has been shown to be important for the pharmacological action of the drug (11–14). The formed CsA-Cyp complex is a specific inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of Calcineurin (CN), a protein responsible for the activation and proliferation of T cells (15,16).

Despite its most powerful immunosuppressive action over the majority of natural or synthetic cyclosporins, clinical use of CsA is limited by the many and weighty side effects. In fact CsA can cause nephrotoxicity, hypertension, and diseases of lipid metabolism (17,18), and, above all, it can favor the excretion of essential elements, such as calcium and magnesium. The direct connection with magnesium and calcium levels has recently led to the investigation of CsA-metal complexes, revealing a strong association with Ca(II) and Mg(II) (19–21). Besides this, the mechanism of interconversion of the cis 9-10 peptide bond to the trans conformation, pivotal for the possible binding with Cyp, has been investigated in the case of the CsA-lithium complex (22). From this point of view, the encounter with metal ions may be expected to favor conformational changes in CsA that might affect the interaction with its target receptor (20,23,24).

With the aim of gaining information on the possible involvement of metal ions in the action mechanism of CsA, this work reports on NMR investigations of its interactions with magnesium(II) and cerium(III) as a paramagnetic probe for calcium. It is in fact well known that cerium and calcium have similar ionic radii and similar coordination modes (25,26), such that the lanthanide has been thoroughly exploited to probe calcium binding sites in proteins (27,28). NMR and circular dichroism studies on the Ca(II) and Mg(II) complexes with CsA have already been reported (21). Although the evaluated binding constants were consistent with the possible ionophoric properties of CsA, no structural details were obtained and compared with those of free CsA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NMR studies

CsA, obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and used without further purification was dissolved in CD3CN at a concentration of 16 mM. The desired concentrations of Mg(II) or Ce(III) ions were achieved by using stock solutions of either Mg(ClO4)2 or Ce(ClO4)3. TSP-d4, 3-trimethylsilyl-[2,2,3,3-d4] propionate sodium salt, was used as the internal reference standard. Mg(ClO4)2, Ce(ClO4)3, CD3CN, and TSP-d4 were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co.. NMR measurements were performed at 14.1 T with a Bruker (Karlsruhe, Germany) Avance 600 MHz spectrometer at controlled temperatures (±0.2 K) using a TBI (triple broadband inverse) probe. Water suppression was achieved by a presaturation pulse at the desired frequency. A typical NMR spectrum required eight transients acquired with a 10-μs 90° pulse and 2.0-s recycling delay. Proton resonance assignment was accomplished through correlation spectroscopy (COSY), total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY), nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY), and rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) standard experiments. Carbon and N-methyl proton resonance assignment was obtained through 1H-13C HMBC and HSQC standard 2D sequences. TOCSY spectra were obtained using the MLEV-17 pulse sequence with a mixing time of 75 ms. NOESY and ROESY spectra were obtained at different values of the mixing time. Spectra processing was performed on a Silicon Graphics (Mountain View, CA.) O2 workstation using the XWINNMR 2.6 software.

Spin lattice relaxation rates (R1) were measured with inversion recovery (IR) pulse sequences. All rates were calculated by regression analysis of the initial recovery curves of longitudinal magnetization components leading to errors not larger than ±3%. Instead of the simple IR sequence, suitable for well-isolated signals, the IR-TOCSY sequence was applied to overlapping NMR resonances (29). The T1 values were determined by a three-parameter fit of peak intensities to the following equation:

|

where B is a variable parameter (<1) that considers nonideal magnetization. The obtained results were compared with those obtained from normal IR sequence. The agreement was found in the error limit of both experiments.

Structure determination and molecular dynamics calculations

The intensities of ROESY crosspeaks for free CsA, the CsA-Mg(II), and the CsA-Ce(III) complexes, referenced to crosspeaks related to proton pairs at fixed distances, were converted into proton-proton distance constraints; these constraints were then used to build a pseudopotential energy for structure determination through a simulated annealing (SA) procedure in torsion angle space with the program DYANA (30). For the CsA-Ce(III) complex, additional metal-proton distance constraints were obtained from the R1 values (vide infra).

The calculations were performed with 300 random starting structures of CsA and 10,000 steps of SA. Since only one molecule can be given as input in the program, for the complexes we linked the peptide to the metal ion through a long chain of linkers, i.e., residues made by atoms without van der Waals radius. These linkers could freely rotate around their bonds, without causing steric repulsions, allowing us to sample a large number of relative positions of the ligand with respect to the magnesium and cerium ions before the minimization step. CsA contains several nonstandard amino acids, so that the topologies of these residues had to be added to the DYANA library: this was achieved by building these residues with the program MOLMOL 2K 1.0 (31), starting from the corresponding standard amino acids and adding the necessary atoms, bond distances, angles, and dihedrals in a sequential way. Moreover an upper distance constraint of 1.34 Å with a force constant of 100 was imposed between the carbonyl carbon of residue 11 and the amide nitrogen of residue 1 to cyclize the peptide.

On the best structures obtained with this procedure we performed an energy minimization followed, for the magnesium complex, by a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation using the program GROMACS (32,33) with the ffG43a2 force field (34). In this case the nonstandard amino acids were already present in the chosen force field, and the cyclization of the peptide was explicitly taken into account adding to its topology the necessary bonds, angles, and dihedrals, involving residues 11 and 1, defined as in a standard peptide bond between two consecutive residues. The structure was first minimized in vacuo with the steepest descents method and then with conjugate gradient. Then it was solvated using a parallelepiped box of acetonitrile (35), with periodic boundary conditions imposing that the minimum distance between any atom of the peptide and the box edge be 1.5 nm. The charge of metal ions was balanced by adding, respectively, two Cl ions for the CsA-Mg(II) complex and three Cl ions in the case of the Ce(III) complex. The resulting systems were again energy minimized and subsequently, in the case of the CsA-Mg(II) complex, brought to the temperature of 298 K through six MD runs in each of which the temperature was raised by 50 K. Then an MD simulation of 100 ps at constant temperature T = 298 K was performed. During these simulations distance constraints of 0.19–0.26 nm were imposed between the metal and its coordinating oxygens (36).

The final structure of the CsA-Mg(II) complex (excluding the solvent), obtained by the simulation in acetonitrile, was then solvated in water and brought to the temperature of 298 K with the same procedure and parameters mentioned before for acetonitrile, and finally an MD run of 500 ps at T = 298 K was performed. During this trajectory in water the complex was kept fixed at its initial conformation, since our aim in this case was only to investigate possible interactions between the complex and the residual water present in the sample. In both simulations (in acetonitrile and in water) peptide and solvent separately were weakly coupled to a temperature bath at the chosen temperature and to a pressure bath at 1 atm, with relaxation times τT = 0.1 ps and τP = 0.5 ps, respectively, using Berendsen's weak coupling algorithm (37); bond lengths were constrained to equilibrium values using the SHAKE procedure (38), with a geometric tolerance of 10−4 and the time step set to 2 fs. Nonbonded interactions were treated using a twin range method (39): within a short-range cutoff of 0.8 nm all interactions were determined at every time step, whereas longer range contributions within a cutoff of 1.4 nm were evaluated each time the pair list was generated.

RESULTS

NMR studies on CsA in acetonitrile

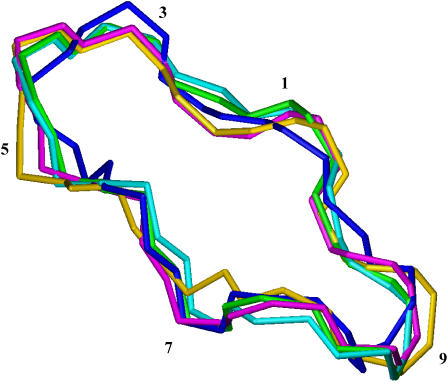

The 1H and 13C assignment of the free CsA sample in CD3CN was determined by means of homonuclear and heteronuclear 2D experiments, and it was in complete agreement with previous reports (20). The ROESY crosspeaks of free CsA were converted into distance restraints to obtain the motionally averaged ‘preferred’ conformation. The ROESY spectrum provided 54 intraresidue, 20 sequential, and nine medium-range rotating-frame Overhauser effects (ROEs), strongly suggesting the occurrence of some structuring in solution. Moreover the presence of a cis peptide bond between MeLeu9 and MeLeu10 was found, as already described (20). The backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the best four structures thus obtained was 0.01 nm, and the ROE violations are reported in Table S1. On the experimentally determined structure an energy minimization followed by an MD simulation in acetonitrile was performed. All the structures found are reported in Fig. 1.

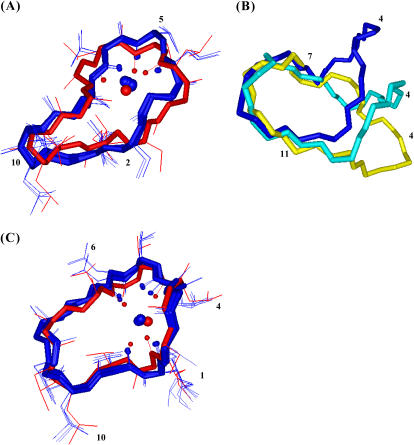

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of free CsA conformation obtained from experimental data with those at various stages of the MD simulation in acetonitrile. Color codes are the following: best structure resulting from DYANA program (blue), after energy minimization (EM) in vacuo (cyan), after EM in acetonitrile (green), brought to 298 K (gold), after 100 ps of MD at 298 K (magenta).

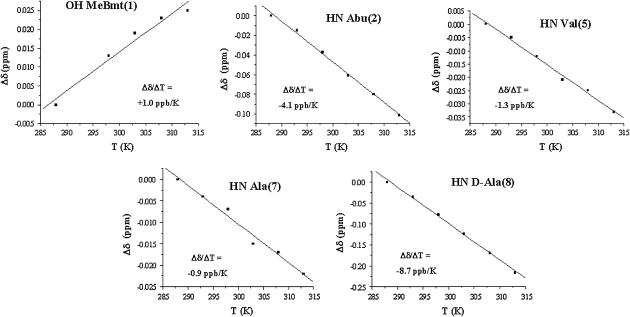

The involvement of mobile protons in hydrogen bonds was checked by measuring the temperature dependence of their chemical shift in the range 288–313 K. A temperature coefficient less negative than −4.5 ppb/K, in fact, supports the presence of a hydrogen bond (40). The calculated temperature coefficients (Figure S1A) indicate that only the Val5 amide proton is apparently involved in an intramolecular hydrogen bond. The analysis, during MD simulation, of intramolecular hydrogen bonds between the peptide mobile protons and their possible hydrogen bond partners confirms the involvement of Val5 amide proton in an H-bond with the carbonyl oxygen of Sar3 (Figure S1B).

NMR studies on the CsA-Mg(II) complex

The addition of 0.5 equivalents of Mg(II) to the CsA sample caused the appearance of additional sets of signals in the one-dimensional (1D) spectra (Fig. 2 A). Moreover, the addition of further 0.5 equivalents of Mg(II) resulted in the complete disappearance of the signals belonging to free CsA and the consequent increase in intensity of the new ones. This is in agreement with the formation of 1:1 CsA-Mg(II) complex in slow exchange with the free form on the NMR timescale, as previously reported for CsA complexes with Mg(II) and Ca(II) (20).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Comparison of 1D spectra of free CsA (bottom), CsA + 0.5 eq. Mg(II) (middle), and CsA + 1 eq. Mg(II) (top); (B) comparison of 1D spectra of free CsA (bottom), CsA + 0.5 eq. Ce(III) (middle), and CsA + 1 eq. Ce(III) (top).

The complete 1H and 13C assignments of the magnesium(II) complex are reported in Tables S2 and S3. The comparisons of proton and carbon chemical shifts of the complex with those of the free form are reported in Fig. 3 A. These data suggest coordination of Mg2+ to the carbonyl oxygens of residues 4, 5, and 6 based on the preferential coordination of magnesium to oxygen donors (41,42) and on the general observation that diamagnetic metals induce 13C downfield shifts of directly bound carbonyls (21). Based on the fact that magnesium is known to adopt octahedral coordination geometry (41,42), residual water molecules were hypothesized to be involved in completion of the metal coordination sphere.

FIGURE 3.

Chemical shift variations (Δδ = δ(complex) − δ(free)) of carbonyl carbon, α-carbon, and α-proton signals of (A) the CsA-Mg(II) complex and (B) the CsA-Ce(III) complex in acetonitrile at 298 K with respect to the free form.

The chemical shift temperature coefficients of mobile protons in the presence of mg(II) (Fig. 4) show that all the analyzed protons, except the amide proton of residue 8, have a coefficient larger than the threshold value. In particular, the disappearance of the exchange crosspeak between the hydroxyl proton of residue 1 (HG1(1)) and the residual water in the ROESY spectra of the complex indicates that this proton cannot exchange with other mobile protons in the system in the presence of magnesium, supporting its involvement in an H-bond.

FIGURE 4.

Plots of the chemical shift variations as a function of T for the mobile protons of the CsA-Mg(II) complex, with the temperature coefficients obtained by the fitting.

To better determine the effects caused by the metal ion, proton longitudinal relaxation rates (R1) were measured and compared with those of the free form. In fact a change in the R1 value can be due either to a different mobility of the molecule or to a change in the chemical environment of the observed proton; in the first case, however, a common effect on all α-protons should be measured. The observed proton relaxation rate variations ΔR1 (Table 1) of the various residues are instead affected to a different extent, suggesting a structural rearrangement of CsA upon Mg(II) coordination, rather than a global mobility change.

TABLE 1.

Longitudinal relaxation rates (R1) of CsA protons in the free form (R1 free) and in the magnesium complex (R1 Mg), and their variation (ΔR1 = R1 Mg − R1 free)

| Proton | R1_free (s−1) | R1_Mg (s−1) | ΔR1 (s−1) | Proton | R1_free (s−1) | R1_Mg (s−1) | ΔR1 (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeBmt1 HNMe | 1.49 | 1.68 | 0.19 | MeLeu6 HNMe | 1.44 | 1.57 | 0.13 |

| MeBmt1 Hβ | 1.91 | 1.87 | −0.04 | MeLeu6 Hα | 1.66 | 1.86 | 0.20 |

| MeBmt1 OH | 1.18 | 1.24 | 0.06 | Ala7 HN | 1.86 | 1.77 | −0.09 |

| Abu2 HN | 2.05 | 2.38 | 0.33 | Ala7 Hα | 0.78 | 1.78 | 1.00 |

| Abu2 Hα | 1.14 | 1.52 | 0.38 | D-Ala8 HN | 1.39 | 1.69 | 0.30 |

| Sar3 HNMe | 1.27 | 1.59 | 0.32 | D-Ala8 Hα | 1.27 | 2.12 | 0.85 |

| Sar3 Hα | 2.17 | 2.95 | 0.78 | MeLeu9 HNMe | 1.37 | 1.45 | 0.08 |

| Sar3 Hα′ | 1.77 | 2.76 | 0.99 | MeLeu9 Hα | 2.37 | 2.50 | 0.13 |

| MeLeu4 HNMe | 1.40 | 1.36 | −0.04 | MeLeu10 HNMe | 1.18 | 1.52 | 0.34 |

| MeLeu4 Hα | 1.13 | 1.99 | 0.86 | MeLeu10 Hα | 2.47 | 2.43 | −0.04 |

| Val5 HN | 1.62 | 2.75 | 1.13 | MeVal11 HNMe | 1.47 | 1.60 | 0.13 |

| Val5 Hα | 1.33 | 1.82 | 0.49 | MeVal11 Hα | 1.36 | 1.43 | 0.07 |

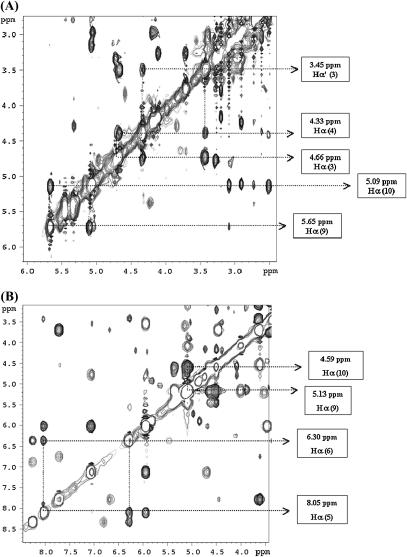

From the analysis of the ROESY spectrum of the CsA-Mg(II) complex, besides the cis peptide bond between MeLeu9 and MeLeu10, an additional one was found between Sar3 and MeLeu4 as strongly supported by the presence of a dipolar crosspeak between the α-protons of these two residues (Fig. 5 A).

FIGURE 5.

(A) Part of the ROESY spectrum of the CsA-Mg(II) complex, showing the crosspeaks between Hα of MeLeu9 and Hα of MeLeu10, and between Hα (1 and 2) of Sar3 and Hα of MeLeu4; (B) part of the ROESY spectrum of the CsA-Ce(III) complex, showing the crosspeaks between Hα of MeLeu9 and Hα of MeLeu10, and between Hα of Val5 and Hα of MeLeu6.

In the same way as for free CsA, 48 intraresidue, 16 sequential, and six medium-range ROEs, obtained from the analysis of 2D ROESY spectra of the CsA-Mg(II) complex, were converted into distance constraints and were used to obtain the final structures reported in Fig. 6 A. Additional metal-carbonyl oxygen distance constraints for residues MeLeu4, Val5, and MeLeu6 were used to take into account the observed coordination behavior of the metal. The backbone RMSD of the best four structures was 0.01 nm. The ROE violations are reported in Table 2. A comparison between the best structure of free and Mg(II)-bound families is shown in Fig. 6 B. An energy minimization, followed by an MD simulation in acetonitrile (md1) were performed on the obtained structure, using as restraints only the oxygen-metal ion distances already imposed for the structure calculation (36) to determine the intramolecular hydrogen bonds. A further simulation in water (md2) (Fig. 7) was performed to detect the presence of hydrogen bonds with water. Our approach consisted of keeping the peptide structure fixed during the md2 simulation to avoid dramatic solvent-dependent conformational changes. It is, in fact, well known that CsA can adopt different conformations in polar and in apolar solvents (9). This latter simulation was thus focused only on looking for water accessibility to the cyclic CsA peptide in the presence of the Mg2+ ion and on the possible stabilization of metal-bound water molecules by hydrogen bonds with the peptide.

FIGURE 6.

Best four structures of the CsA-Mg(II) complex (blue) superimposed with the one obtained after minimization (red) (A); comparison between the best structures obtained for free CsA (yellow), for the CsA-Mg(II) (blue), and the CsA-Ce(III) complex (cyan) (B); best four structures of the CsA-Ce(III) complex (blue) superimposed with the one obtained after minimization (red) (C). In panels A and C, the metal and its coordinating oxygens are shown as spheres.

TABLE 2.

ROE violations of the best four structures of the CsA-Mg(II) complex

| Maximum violation (nm) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeBmt1 HNMe | MeBmt1 OH | 0.01 | – | – | * | + |

| MeBmt1 OH | MeBmt1 Hγ | 0.02 | + | * | + | + |

| MeBmt1 OH | Ala7 Hα | 0.01 | + | + | + | * |

| MeBmt1 Hζ | MeBmt1 Hδ | 0.04 | + | + | + | * |

| MeBmt1 Hδ | MeBmt1 Hγ | 0.015 | + | + | + | * |

| Abu2 Hβ | Abu2 Hβ′ | 0.02 | + | + | + | * |

| Sar3 HNMe | Ala7 Hβ | 0.02 | * | + | + | + |

| Sar3 Hα′ | D-Ala8 Hβ | 0.01 | * | – | – | – |

| MeLeu4 Hα | MeLeu4 Hβ | 0.02 | * | + | + | + |

| Ala7 Hα | D-Ala8 HN | 0.03 | + | + | * | + |

| D-Ala8 Hα | MeLeu9 HNMe | 0.04 | + | * | + | + |

| MeLeu9 HNMe | MeLeu9 Hα | 0.07 | + | * | + | + |

| MeLeu9 HNMe | MeLeu9 Hβ | 0.01 | – | * | – | – |

| MeLeu9 Hα | MeVal11 HNMe | 0.02 | * | + | + | + |

| MeLeu10 Hβ | MeLeu10 Hγ | 0.03 | + | * | + | + |

| MeVal11 HNMe | MeVal11 Hβ | 0.01 | – | – | * | + |

The “+” symbol indicates a violation and the “*” symbol indicates the structure with the maximum violation.

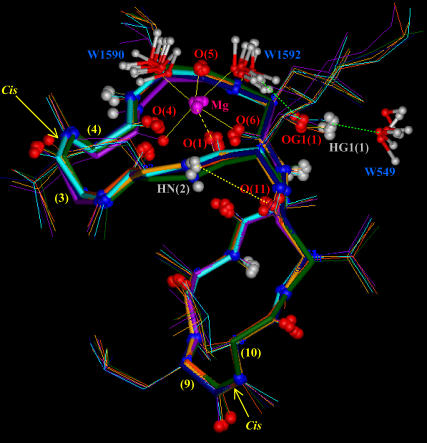

FIGURE 7.

Snapshots taken during the MD simulation of the CsA-Mg(II) complex in water (md2), showing the octahedral coordination of the Mg2+ ion with the carbonyl oxygens of residues 1, 4, 5, and 6 and with the oxygens of two water molecules (W1590 and W1592). The figure also shows the H-bond between the amide proton of Abu2 and the carbonyl oxygen of MeVal11, and the H-bonds between the oxydril oxygen of MeBmt1 side chain and the hydrogen of water W1592, and between the corresponding oxydril proton and the oxygen of water W549.

NMR studies on the CsA-Ce(III) complex

A new set of signals in the proton NMR spectra was detected after the addition of 0.5 equivalents of Ce(III) to the CsA sample (Fig. 2 B), with a behavior similar to the magnesium complex when adding further 0.5 equivalents of Ce(III). This is in agreement with the formation of a 1:1 complex in slow exchange with the free form on the NMR timescale also in the case of cerium. Addition of cerium in a 1:1 ratio to the CsA-Mg(II) complex results in the appearance of the CsA-Ce(III) complex signals and in the disappearance of the CsA-Mg(II) complex signals (data not shown), indicating that cerium has a higher affinity than magnesium for CsA. This is not in contrast with the previously reported similar affinities for calcium and magnesium binding to CsA (20,21); in fact it must be considered that trivalent lanthanide ions generally have greater binding constants than calcium although sharing the same mode of coordination (43).

The complete 1H and 13C assignments of the cerium(III) complex are shown in Tables S4 and S5. The comparisons of proton and carbon chemical shifts with those of the free form (Fig. 3 B) indicate that the most affected carbonyl signals belong to residues 1, 4, 6, and 11, strongly supporting involvement of the corresponding carbonyl oxygens in Ce(III) binding.

Longitudinal relaxation rates (R1) were measured for the CsA-Ce(III) complex and used to obtain metal-proton distance constraints (Table 3), based on the Solomon and Curie equations in the appropriate form for lanthanides (44), taking into account the paramagnetic nature of the metal:

|

|

|

where μo is the magnetic permeability of vacuum, μB is the electron Bohr magneton, J is the total angular momentum quantum number of the paramagnetic species, gJ is the corresponding g factor, γI is the proton magnetogyric ratio, ωI and ωS are the proton and electron precession frequencies, τr is the rotational correlation time of the protein, τM is the lifetime of the metal-peptide complex, τe is the electronic relaxation time of the metal ion, and r is the proton-metal distance.

TABLE 3.

Paramagnetic relaxation rates measured for the Ce(III)-CsA complex and the corresponding metal-proton distances obtained through the Solomon-Curie equation

| Proton | R1 (s−1) | r (nm) τe = 0.4 ps | r (nm) τe = 0.1 ps |

|---|---|---|---|

| MeBmt1 HNMe | 3.03 | 0.65 | 0.57 |

| MeBmt1 Hβ | 11.23 | 0.53 | 0.46 |

| MeLeu4 HNMe | 3.99 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| Val5 HN | 5.28 | 0.60 | 0.52 |

| MeLeu6 HNMe | 7.09 | 0.57 | 0.49 |

| MeLeu6 Hα | 6.17 | 0.58 | 0.50 |

| Ala7 Hβ | 13.7 | 0.51 | 0.44 |

| D-Ala8 HN | 3.89 | 0.63 | 0.54 |

| MeLeu10 HNMe | 2.42 | 0.68 | 0.59 |

| MeVal11 HNMe | 10.42 | 0.53 | 0.46 |

| MeVal11 Hα | 3.89 | 0.63 | 0.54 |

Curie spin relaxation may be significant when the dipolar coupling described by the Solomon equation is governed by the electronic relaxation times, that is, when the latter are much smaller than the rotational correlation times. As for the determination of the correlation time, in the Solomon part of the equation, the electronic relaxation time dominates over the exchange and the rotational correlation time, being in the range of 0.1–0.4 ps. For the Curie part of the equation the rotational correlation time 0.28 ns, calculated from the Stokes equation, was used. Two different sets of distances were calculated (Table 3) by using τe = 0.4 ps or 0.1 ps, respectively, and they were used as upper and lower limits for structure determination.

The analysis of the ROESY spectrum of the CsA-Ce(III) complex shows that residues 9 and 10 conserve a cis peptide bond and a new cis bond appears between residues 5 and 6 (Fig. 5 B).

Forty-five intraresidue and 17 sequential ROEs obtained from the analysis of 2D ROESY spectra were converted into interproton distance constraints which were used, together with proton-metal distance constraints obtained from the R1 values, to obtain the final structures reported in Fig. 6 C. Additional metal-carbonyl oxygen distance constraints were imposed for the coordinating residues (MeBmt1, MeLeu4, MeLeu6, and MeVal11). The backbone RMSD of the best four structures was 0.03 nm. The ROE violations are reported in Table 4. A comparison between the best structure of free and Ce(III)-bound families is shown in Fig. 6 B. An energy minimization was performed on the obtained CsA-Ce(III) structure, using only the oxygen–metal ion distances already imposed for the structure calculation as restraints (36).

TABLE 4.

ROE violations of the best four structures of the CsA-Ce(III) complex

| Maximum violation (nm) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeBmt1 HNMe | MeBmt1 Hα | 0.02 | * | + | + | + |

| Ala7 HN | Ala7 Hα | 0.01 | + | * | – | – |

| MeLeu9 Hα | MeLeu9 Hβ | 0.01 | * | + | + | + |

| MeLeu10 Hβ | MeVal11 HNMe | 0.01 | + | + | + | * |

The “+” symbol indicates a violation and the “*” symbol indicates the structure with the maximum violation.

DISCUSSION

The obtained structure of free CsA in acetonitrile (Fig. 1) is similar to those reported in the literature for free CsA in apolar solvents (6,7). A single cis peptide bond, between residues MeLeu9 and MeLeu10, is found, and a turn formed by residues Sar3, MeLeu4, and Val5 is detected, supported by the presence of a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen of Sar3 and the amide proton of Val5. On the other hand, no other hydrogen bonds have been identified, resulting in the lack of a regular β-sheet structure in the region spanning residues 11–7.

A comparison of the CsA-Mg(II) complex chemical shifts with those of the free form suggests binding of magnesium to the carbonyl oxygens of residues from 4 to 6. In particular, the downfield shift observed for MeLeu4, Val5, MeLeu6 carbonyl signals in the CsA-Mg(II) complex (Fig. 3 A) indicates a direct metal coordination, whereas the upfield shift of MeBmt1, Sar3, Ala7, and MeLeu10 should be correlated to conformational changes or secondary binding effects (19). The involvement in metal binding of residues from 4 to 6 is supported also by the effects recorded on their α-carbon and α-proton shifts (Fig. 3 A) and by the strong relaxation rate variations (Table 1). In addition to the above mentioned findings, which are in agreement with those previously reported (20,21), the conformation of Mg(II)-complexed CsA has been determined by restrained SA based on the obtained NMR data (Fig. 6 A). Upon Mg(II) complexation, a bending of the polypeptide chain in correspondence with the α-carbons of residues 1 and 6 occurs (Fig. 6 B). Regarding the presence of secondary structure elements, the CsA-Mg(II) complex shows a bend spanning residues 3–6 and a β-bridge extending from MeVal11 to Abu2. Metal binding to residues 4–6 can explain the bend-like structure found in this region and the observed trans-cis isomerization of the Sar3-MeLeu4 peptide bond.

As shown in Fig. 6 A, only the metal position is better arranged after energy minimization and MD simulation of the CsA-Mg(II) complex, as a consequence of consideration of electrostatic contributions arising from atomic charges, whereas the overall peptide conformation is quite conserved, also in the absence of any constraints except those between the Mg(II) ion and its three coordinating oxygens. A remarkable feature of the obtained structures is the position of the carbonyl oxygen of residue 1, whose distance to the metal remains fixed to the binding value of 0.20 nm along all the md1 trajectory, without imposing on it any distance restraint, suggesting its coordination to the metal ion. Such a result is not in agreement with the NMR MeBmt1 carbonyl chemical shift variation shown in Fig. 3. In fact this shift, although large, exhibits an opposite sign compared to those of residues MeLeu4, Val5, and MeLeu6 ruling out, in principle, the involvement in metal coordination. Such behavior could be due to a stronger binding of magnesium to residues 4, 5, and 6 with respect to residue 1, which determines a redistribution of the electronic density, resulting in a deshielding effect on the former three residues and in a shielding effect on residue 1. Since magnesium is known to adopt a octahedral coordination geometry (41,42), the involvement of the oxygens of two water molecules to complete the Mg(II) coordination sphere was hypothesized; it is in fact reasonable to think that the peptide cannot provide further donors to the metal, since no other peptide atoms, except carbonyl oxygens of residues 4, 5, 6, and 1, remain within binding distance from magnesium along the MD simulation in acetonitrile (md1). Therefore an MD simulation of the CsA-Mg(II) complex in water (md2) was performed. In all the snapshots reported in Fig. 7, the oxygens of two water molecules (W1590 and W1592) were found within Mg(II) binding distance. The Mg(II)-O(W1590) and Mg(II)-O(W1592) distances have therefore been monitored every picosecond along the whole MD trajectory (Fig. 8), showing that their values remain in the range of 0.18–0.21 nm, typical of Mg-O binding. These findings strongly suggest that magnesium maintains a pseudo-octahedral binding geometry, where residues MeLeu4, Val5, and MeLeu6 are coordinated more strongly than MeBmt1, and the two water molecules W1590 and W1592 complete the coordination sphere.

FIGURE 8.

Mg(II)-O(W1590) and Mg(II)-O(W1592) distances during the MD simulation of the CsA-Mg(II) complex in water.

The involvement of mobile protons in intramolecular hydrogen bonds was also analyzed during the MD simulation in acetonitrile, and only Abu2 NH and MeVal11 CO were found within H-bond distance (Fig. 7). Therefore the solvent accessibility of mobile protons was monitored during the md2 trajectory (Figure S2, Supplementary Material) to verify the presence of water-peptide hydrogen bonds. The oxygen of water molecule W549 stabilizes after 200 ps of simulation at a distance 0.18–0.23 nm from the OH proton of MeBmt1; the corresponding OH oxygen of MeBmt1, in turn, is involved in an H-bond with the hydrogens of water molecule W1592, directly involved by itself in Mg(II) coordination; the figure points out that the two water hydrogens are alternatively at a distance of ∼0.20 nm from OG1 (1). The other mobile protons of the peptide seem to be simply exposed to the solvent and not able to form stable H-bonds with water.

As for the CsA-Ce(III) complex, interpretation of chemical shift variations with respect to the free form takes advantage of Ce(III) being a paramagnetic shift reagent, such that this effect is expected to largely prevail on diamagnetic effects, although no direct correlation can be made in this case between the sign of the chemical shift and metal binding. Indeed the observed variations are in general larger than in the case of magnesium, particularly for carbonyl carbons (Fig. 3 B). These data suggest metal coordination to the carbonyl oxygens of residues MeBmt1, MeLeu4, MeLeu6, and MeVal11. Since CsA slowly exchanges from the cerium complex in the NMR timescale, the measured R1 values can be directly used to obtain information on metal-proton distances through the Solomon and Curie equations (Table 3). The largest R1 values are found for the β-proton of MeBmt1, the N-methyl and α-protons of MeLeu6, the β-proton of Ala7, the N-methyl proton of MeVal11. Taking into account the lack of information on the remaining residues, these data are in agreement with the above mentioned coordination mode. Moreover, two cis peptide bonds are found, one between MeLeu9 and MeLeu10 and another between Val5 and MeLeu6. The conformation of Ce(III)-complexed CsA here obtained from ROE and R1 data (Fig. 6 C) shows a bend including residues 4–6 and a β-bridge going from MeVal11 to MeBmt1.

Since cerium is known to adopt the same mode of coordination of calcium (25,26), these results can be compared with those reported in the literature for the CsA-Ca(II) complex (20,21), suggesting that Ca(II) coordination more strongly involves the region including residues 11–5, and the conservation of the cis bond between residues 9 and 10.

A comparison among free, Mg(II)-complexed, and Ce(III)-complexed CsA conformations highlights a bending of the two metal complexes with respect to free CsA at residues 11/1 and 6, which can be explained by the fact that metal binding occurs in both cases in the region spanning residues 11–6, leaving almost unaffected the complementary region (including the presence of the MeLeu9-MeLeu10 cis bond), in agreement with previous data (21).

The two metal complexes show a similar pattern of secondary structural elements but have the second cis peptide bond in different positions, in agreement with the different binding mode displayed by magnesium and cerium.

The findings here ratify the formation of strong 1:1 complexes of CsA with both magnesium(II) and cerium(III) in acetonitrile, in agreement with previous reports (20,21). In both cases metal coordination takes place at carbonyl oxygens and yields substantial changes in conformation when compared to the average structure assumed by free CsA. However, the residues involved in metal coordination and the resulting conformational changes are different for the two metals.

The magnesium ion binds to the carbonyl oxygens of MeLeu4, Val5, and MeLeu6 and, more weakly, to the carbonyl oxygen of MeBmt1, and the oxygens of two residual water molecules complete the Mg(II) pseudo-octahedral coordination sphere. Magnesium complexation causes a bending of the peptide in correspondence of residues MeBmt1 and MeLeu6, the trans-cis isomerization of the peptide bond between Sar3 and MeLeu4, and a variation of the global H-bond pattern.

The cerium ion binds to the carbonyl oxygens of residues MeBmt1, MeLeu4, MeLeu6, and MeVal11. This type of coordination is accompanied by a bending of the peptide and by the trans-cis isomerization of the Val5-MeLeu6 peptide bond. The large effect on peptide conformation is in agreement with the fact that Ce(III) binds to atoms placed in different regions of the molecule, which are quite far from one another in free CsA.

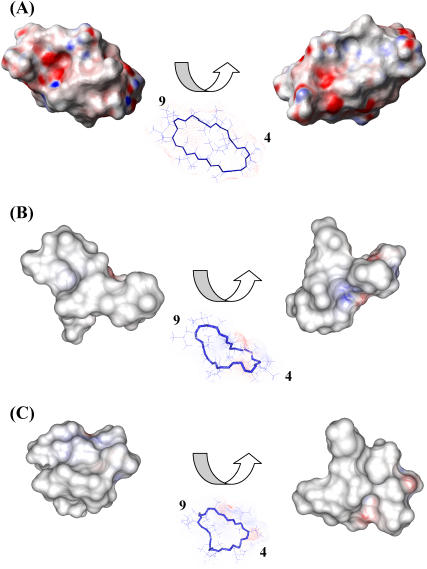

Upon binding the two metal ions, the electrostatic potential surface of CsA is modified, as shown in Fig. 9, in a way that increases the hydrophobicity of the molecule.

FIGURE 9.

Electrostatic potential surface of free CsA (A), the CsA-Mg(II) complex (B), and the CsA-Ce(III) complex (C); positively charged regions are shown in blue, negatively charged ones in red, and hydrophobic ones in white/gray. For each structure two views are shown, rotated by 180° with respect to one another.

The conformational changes that metal ions, especially calcium, induce on CsA in a lipophilic environment such as that provided by acetonitrile, may be revealing for the connection between calcium homeostasis and the mechanism of action of CsA. In particular the extensive bending of the CsA molecule around Ce(III) and the increased hydrophobic surface may be relevant in accounting for a possible role of CsA in acting as ionophore for calcium.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

The 600 MHz TOCSY and ROESY spectra of the peptide in the presence of cerium were recorded at the PARABIO Large Scale Facility in Florence; the support of the European Community (Access to Research Infrastructure action of the Improving Human Potential Program) is kindly acknowledged.

We acknowledge the CIRMMP (Consorzio Interuniversitario Risonanze Magnetiche di Metalloproteine Paramagnetiche) for financial support.

References

- 1.Ruegger, A., M. Kuhn, H. Lichti, H. R. Loosli, R. Huguenin, C. Quiquerez, and A. von Wartburg. 1976. Cyclosporin A, a peptide metabolite from Trichoderma polysporum Rifai, with a remarkable immunosuppressive activity. Helv. Chim. Acta. 59:1075–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenger, R. M. 1985. Synthesis of cyclosporine and analogues: structural requirements for immunosuppressive activity. Angew. Chem. 24:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghavan, S., and M. A. Rasheed. 2004. Modular and stereoselective formal synthesis of MeBmt, an unusual amino acid constituent of cyclosporin A. Tetrahedron. 60:3059–3065. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter, B., R. A. Palmer, R. Withnall, T. C. Jenkins, and B. Z. Chowdhry. 2003. Two new cyclosporin folds observed in the structures of the immunosuppressant cyclosporin G and the formyl peptide receptor antagonist cyclosporin H at ultra-high resolution. Org. Biomol. Chem. 1:1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu, W., S. L. Heald, M. W. Harding, R. E. Handschumacher, and I. M. Armitage. 1990. Structural elements pertinent to the interaction of cyclosporin A with its specific receptor protein, cyclophilin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 40:131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loosli, H., H. Kessler, H. Oschkinat, H.-P. Weber, T. J. Petcher, and A. Widmer. 1985. Peptide conformations. Part 31. The conformation of cyclosporin A in the crystal and in solution. Helv. Chim. Acta. 68:682–703. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler, H., H. R. Loosli, and H. Oschkinat. 1985. Peptide conformations. Part 30. Assignment of the 1H-, 13C-, and 15N-NMR spectra of cyclosporin A in CDCl3 and C6D6 by a combination of homo- and heteronuclear two-dimensional techniques. Helv. Chim. Acta. 68:661–681. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ran, Y., L. Zhao, Q. Xu, and S. H. Yalkowsky. 2001. Solubilization of cyclosporin A. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2:E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Tayar, N., A. E. Mark, P. Vallat, R. M. Brunne, B. Testa, and W. F. van Gunsteren. 1993. Solvent-dependent conformation and hydrogen-bonding capacity of cyclosporin A: evidence from partition coefficients and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Med. Chem. 36:3757–3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neri, P., R. Meadows, G. Gemmecker, E. Olejniczak, D. Nettesheim, T. Logan, R. Simmer, R. Helfrich, T. Holzman, J. Severin, and S. Fesik. 1991. 1H, 13C and 15N backbone assignments of cyclophilin when bound to cyclosporin A (CsA) and preliminary structural characterization of the CsA binding site. FEBS Lett. 294:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber, C., G. Wider, B. von Freyberg, R. Traber, W. Braun, H. Widmer, and K. Wuthrich. 1991. The NMR structure of cyclosporin A bound to cyclophilin in aqueous solution. Biochemistry. 30:6563–6574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fesik, S. W., R. T. Gampe, T. F. Holzman, D. A. Egan, R. Edalji, J. R. Luly, R. Simmer, R. Helfrich, V. Kishore, and D. H. Rich. 1990. Isotope-edited NMR studies show cyclosporin A has a trans 9,10-amide bond when bound to cyclophilin. Science. 250:1406–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theriault, Y., T. M. Logan, R. Meadows, L. Yu, E. T. Olejniczak, T. F. Holzman, R. L. Simmer, and S. W. Fesik. 1993. Solution structure of the cyclosporin A/cyclophilin complex by NMR. Nature. 361:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wüthrich, K., B. von Freyberg, C. Weber, G. Wider, R. Traber, H. Widmer, and W. Braun. 1991. Receptor-induced conformation change of the immunosuppressant cyclosporin A. Science. 254:953–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber, S. L., M. W. Albers, and E. J. Brown. 1993. The cell cycle, signal transduction, and immunophilin-ligand complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 26:412–420. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klee, C. B., H. Ren, and X. Wang. 1998. Regulation of the calmodulin-stimulated protein phospatase, calcineurin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13367–13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahan, B. D. 1989. Cyclosporine. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:1725–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda, S., and S. Koyasu. 2000. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporin. Immunopharmacology. 47:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dancer, R. J., A. Jones, and D. P. Fairlie. 1995. Binding of the immunosuppressant peptide cyclosporin A to calcium, zinc and copper. Is cyclosporin A an Ionophore? Aust. J. Chem. 48:1835–1841. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carver, J. A., N. H. Rees, D. L. Turner, S. J. Senior, and B. Z. Chowdhry. 1992. NMR studies of the Na+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ complexes of cyclosporin A. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 22:1682–1684. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cusack, R., L. Grondhal, D. Fairlie, G. Hanson, and L. Gahan. 2003. Studies of the interaction of potassium(I), calcium(II), magnesium(II) and copper(II) with CsA. J. Inorg. Biochem. 97:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kofron, J. L., P. Kuzmic, V. Kishore, G. Gemmecker, S. W. Fesik, and D. H. Rich. 1992. Lithium Chloride perturbation of cis-trans peptide bond equilibria: effect on conformational equilibria in cyclosporin A and on time-dependent inhibition of cyclophilin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:2670–2675. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw, R., H. H. Mantsch, and B. Z. Chowdhry. 1994. Conformational changes in the cyclic undecapeptide cyclosporin induced by interaction with metal ions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 16:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kock, M., D. Seebach, H. Kessler, and A. Thaler. 1992. Novel backbone conformation of CsA: the complex with lithium chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:2676–2686. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon, R. D. 1976. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. A. A32:751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horrocks, W., and D. R. Sudnick. 1981. Lanthanide ion luminescence probes of the structure of biological macromolecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 14:384–392. [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Amelio, N., E. Gaggelli, N. Gaggelli, F. Mancini, E. Molteni, D. Valensin, and G. Valensin. 2003. The structure of the Ce(III)-Angiotensin II complex as obtained from NMR data and molecular dynamics calculations. J. Inorg. Biochem. 95:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertini, I., M. B. Janik, Y. M. Lee, C. Luchinat, and A. Rosato. 2001. Magnetic susceptibility tensor anisotropies for a lanthanide ion series in a fixed protein matrix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123:4181–4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber, J. G., J. M. Moulis, and J. Gaillard. 1996. Use of 1H longitudinal relaxation times in the solution structure of paramagnetic proteins. application to [4Fe-4S] proteins. Biochemistry. 35:12705–12711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Güntert, P., C. Mumenthaler, and K. Wüthrich. 1997. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273:283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koradi, R., M. Billeter, and K. Wüthrich. 1996. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindahl, E., B. Hess, and D. van der Spoel. 2001. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J. Mol. Model. (Online). 7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berendsen, H., D. van der Spoel, and R. van Drunen. 1995. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Comm. 91:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Gunsteren, W. F., X. Daura, and A. Mark. 1998. GROMOS force field. Encyclopaedia of Computational Chemistry. 2:1211–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guàrdia, E., R. Pinzón, J. Casulleras, M. Orozco, and F. J. Luque. 2001. Comparison of different three site interaction potentials for liquid acetonitrile. Mol. Simul. 26:287–306. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torda, E. A., R. M. Scheek, and W. F. van Gunsteren. 1989. Time-dependent distance restraints in molecular dynamics simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 157:289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berendsen, H., J. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, A. Di Nola, and J. Haak. 1984. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryckaert, J., G. Ciccotti, and H. Berendsen. 1977. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berendsen, H. 1995. Treatment of long range forces in molecular dynamics. In Molecular Dynamics and Protein Structure. J. Hermans, editor. Polycrystal Book Service, Western Springs, IL. 18–22.

- 40.Baxter, N. J., and M. P. Williamson. 1997. Temperature dependence of 1H chemical shifts in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 9:359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glusker, J., A. Kats, and C. Bock. 1999. Metal ions in biological systems. The Rigaku Journal. 16:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bock, C., J. Glusker, and A. Kaufman. 1994. Coordination of water to magnesium cations. Inorg. Chem. 33:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sillèn, L. G., and A. Martell. 1971. Stability constants. The Chemical Society, London, Special Publication No. 25.

- 44.Bertini, I., and C. Luchinat. 1996. NMR of paramagnetic substances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 150:1–292. [Google Scholar]