Abstract

Prior work by members of our laboratory and others demonstrated that adenovirus serotype 30 (Ad30), a group D adenovirus, exhibited novel transduction characteristics compared to those of serotype 5 (Ad5, belonging to group C). While some serotype D adenoviruses bind to the coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR), the ability of Ad30 fiber to bind CAR is unknown. We amplified and purified Ad30 and cloned the Ad30 fiber by overlap PCR. Alignment of Ad30 fiber with Ad3, Ad35, Ad5, Ad9, and Ad17 revealed that Ad30, like Ad9 and Ad17, has a shortened fiber sequence relative to that of Ad5. The knob region of fiber was 45% identical to that of the Ad5 knob regions. We made a chimeric recombinant virus (Ad5GFPf30) in which the Ad5 fiber (amino acids [aa]47 to 582) was replaced with Ad30 fiber sequences (aa 46 to 372), and CAR-mediated viral entry was determined on CAR-expressing Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. While CAR expression significantly increased Ad5GFP-mediated transduction in CHO cells (from 1 to 36%), it did not enhance Ad5GFPf30 gene transfer. Binding of radiolabeled Ad5GFPf30 or Ad30 wild-type virus was also not improved by the expression of CAR. These results suggest that Ad30 fiber is distinct from Ad5, Ad9, and Ad17 fibers in its inability to direct transduction via CAR.

Adenovirus (Ad) tropism is the result of specific binding of the virus to the target cell by means of a cellular receptor. The C-terminal portion of adenovirus fiber, or “knob,” is responsible for the specificity of receptor recognition. The 46-kDa human coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR) interacts with the fiber knobs of representative adenoviruses from most of the defined subgroups (serotypes 2, 4, 5, 9, 12, 15, 17, 19, 31, and 41) (2, 6, 14, 20, 23), indicating that CAR can function as their cellular receptor. The mouse homologue of CAR has also been isolated and shown to mediate infection of human Ad type 2 (Ad2) (3, 18).

CAR is a type I transmembrane protein containing a cytoplasmic COOH terminus and an N-terminal extracellular domain (2, 3, 18). The exoplasmic region contains two immunoglobulin (Ig)-related domains (IgV and IgC2) stabilized by intrachain disulfide bonds and two potential N-linked glycosylation sites. Ad5 fiber interactions with CAR occur within the N-terminal IgV domain (4, 6, 10). Prospective amino acid residues within the fiber required for binding to CAR have been identified (10, 13). By using competitive assays with recombinant fiber, it was found that two amino acids in the AB loop (Ser408 and Pro409), one in the DE loop (Tyr477), and one in the FG loop (Tyr491) were essential (13). A more recent surface plasmon resonance binding study with recombinant wild-type and mutant fibers and immobilized CAR unveiled the importance of Ala406 and Arg412 in the AB loop and Arg481 in β-strand F (10).

CAR is a putative cell adhesion molecule believed to have a role in the development of the brain (7). There is a high degree of sequence identity within the tail regions of human and murine CAR (3, 18). Interestingly, the tail and transmembrane domains are unnecessary for adenoviral binding and entry (10, 14, 20). In some instances, deletion or alteration of these sequences increased cell surface expression of CAR, leading to increased Ad-mediated gene transfer (19).

While the majority of adenoviral serotypes have been shown to interact with CAR, Ad3 and Ad35 are exceptions (16, 17). Of the D serotypes tested (serotypes 9, 15, and 19), all exhibited binding to CAR (14). We previously showed that another D-serotype virus, Ad30, infected primary endothelial and neuronal cells more efficiently than Ad5 (5). To begin to understand the mechanisms for this difference, we first sought to determine whether Ad30 fiber bound CAR. For these experiments, the Ad30 fiber was first cloned and sequenced. We then tested Ad30 fiber interactions with CAR, using both wild-type Ad30 and a recombinant Ad5 whose native fiber was replaced by that of Ad30.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were maintained in DMEM F12 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% FCS. Ad30 (VR-273) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and subsequently amplified by infection of HEK 293 cells. Viral particles were banded in CsCl gradients, dialyzed, and stored in 100-μl aliquots at −80°C. Ad5CMVhCAR (AdhCAR), produced by the University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core, was a kind gift from Joseph Zabner, University of Iowa. Ad5CMVntlacZ (Ad5lacZ), also produced by the University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core, is used routinely in the Davidson laboratory.

Sequencing Ad30 fiber protein.

Viral DNAs from purified Ad30 particles were isolated by standard protease treatment and ethanol precipitation methods. Primers to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fiber gene, designed by means of comparison of the known sequences of four D-serotype viruses, (Ad8, Ad9, Ad15, and Ad17), are AdDfiberF (5′-CGGGATCCGCCACCATGTCAAAGAGGCTCCGG-3′) and the degenerate primer AdDfiberR (5′-CGGGATCCTRATTCTTGGGCYATATAGG-3′), respectively. The fiber gene was completely sequenced in both directions.

Construction of Ad5GFPf30.

The endogenous fiber sequence of Ad5 (nucleotides 31042 to 32787) was replaced with the Ad30 sequence by overlapping PCR. The Ad30 fiber was amplified such that it contained the first 147 bp of the Ad5 tail (bp 31042 to 31189). Overlapping primers specific for the tail-shaft boundary containing 18 bp of Ad5 and 18 bp of Ad30 were generated. In the first phase of the overlapping PCR, two DNA fragments corresponding to the Ad5 tail region and the Ad30 shaft and knob regions were amplified. The tail was generated using primer Ad5fiberforBamH1 (5′-CGCGGATCCGCGATGAAGCGCGCAAGA-3′; bp 31042 to 31189) and 17Ad5overtail (5′-GATTGGGTCAGCCAGTTTCAAAGAGAGTACCCCAGG-3′) with Biolase. The shaft-knob region was amplified with the primers 5Ad17overtail (5′-CCTGGGGTACTCTCTTTGAAACTGGCTGACCCA-3′) and Ad30fRevSpe1 (5′-AAAACTAGTTCATTCTTGGGCGATATA-3′). Primers to the 5′ and 3′ ends were designed to incorporate the restriction enzyme recognition sites BamHI and SpeI, respectively. After 30 PCR cycles, the Ad5 tail and Ad30 shaft-knob region products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and then mixed, and the mixture was used as a template with primers Ad5fiberforBamHI and Ad30fRevSpe1 to amplify the entire chimeric 5/30 fiber. The 1,119-bp-long chimeric 5/30 fiber product, containing the Ad5 tail and the Ad30 shaft and knob domains, was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, digested with NdeI and SpeI, and ligated into pBS/B2HI (22) cut with NdeI and SpeI. The resulting plasmid, pBS-5/30, linearized with NotI and BamHI, and pTG3602/RSVeGFP/Swa1, based on Xia et al. (22), linearized with SwaI to drive homologous recombination in the region of fiber, were used to cotransform the RecA+ Escherichia coli strain BJ5183. We screened the resulting recombinants by PCR and direct sequencing. Positive recombinants contained the entire Ad5 genome, flanked by PacI sites with the following modifications: replacement of the E1 region by an expression cassette in which Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) LTR drives expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and replacement of the endogenous Ad5 fiber with the chimeric 5/30 fiber. This plasmid was then digested by PacI and transfected into HEK 293 cells for the production of viral particles as previously described (1). Cytopathic effect (CPE) was evident 14 days posttransfection in 60-mm2 dishes of HEK 293 cells. Lysates of Ad5RSVeGFPf30 (Ad5GFPf30) were used for further amplification. CPE was evident 40 h postinfection. The virus was harvested and purified by standard methods as described previously (1). The Ad5RSVeGFP control virus (Ad5GFP), with nonrecombinant fiber, was similarly generated. Both viruses were analyzed by plaque assay on HEK 293 or A549 cells. By this method, the titer of Ad5GFPf30 was found to be 4 × 109 PFU/ml and that of Ad5GFP was 1 × 1010 PFU/ml. For all experiments, equivalent particle concentrations were used.

Analysis of recombinant fiber.

Purified Ad5GFP and Ad5GFPf30 (2 × 1010 particles) were boiled at 95°C for 15 min in Laemli buffer and fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature (RT), and incubated with a monoclonal antibody to the N terminus of Ad5 fiber (4D2.5, a kind gift of Jeffrey Engler) (11) that was diluted 1:2,500 in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 overnight at 4°C. The membrane was then washed four times for 5 min with PBS-0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.) diluted 1:2,500 in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at RT. Membranes were washed as previously done and then developed with enhanced-chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Labeling of Ads with [methyl-3H]thymidine.

Ad5GFP, Ad5GFPf30, and wild-type Ad30 were labeled with [methyl-3H]thymidine as described previously (12). Briefly, 150-mm2 dishes were seeded with 2.5 × 107 HEK 293 cells in 15 ml of DMEM-10% FCS. Twenty-four hours later, these cells were infected with recombinant Ad at a multiplicity of infection of 50 or higher. Ten hours postinfection, 1.25 mCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (3.03 TBq/mmol, 82.0 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) was added to the medium and cells were further incubated at 37°C until ∼30 h postinfection. Cells were then harvested, pelleted, washed once with PBS, and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. Virus was released from the cells by four freeze-thaw cycles. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and viral material was subjected to ultracentrifugation in a CsCl gradient and subsequent dialysis against PBS-3% sucrose. Virion-specific radioactivity, measured by liquid scintillation (Packard Tri-Carb 1500 liquid scintillation analyzer), ranged from 9 × 10−6 to 4 × 10−5 cpm per virion.

CAR transfection studies.

CHO cells were plated 24 h prior to infection at a density of 3 × 105 cells per 60-mm2 dish. CHO cells were transfected with Ad5lacZ or Ad5hCAR previously precipitated with CaPi. Ad5lacZ or Ad5hCAR (4 μl of 1012 particles/ml) was added to 1 ml of MEM, precipitated by the addition of 25 μl of 1 M CaCl2, lightly vortexed, and then incubated at RT for 20 min. Medium was removed from CHO cells, and 1 ml of MEM containing the Ad-CaPi precipitant was added to each dish. Cells were incubated with precipitated Ad5lacZ or Ad5hCAR at ∼13,000 particles/cell for 30 min at 37°C, washed with fresh medium, and then incubated with 3 ml of fresh medium for an additional 24 h at 37°C. Twenty-four hours after CaPi-mediated infections, CHO cells were incubated with 500 particles of Ad5GFP or Ad5GFPf30/cell for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed and incubated an additional 24 h at 37°C before fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

FACS analysis.

Infected cells were detached from dishes by incubation with trypsin for 5 min at 37°C followed by pelleting, resuspension in medium with propidium iodide, and FACS analysis for GFP expression. FACS analyses were performed on a Becton Dickinson (San Jose, Calif.) flow cytometer equipped with a 488-nm-diameter argon laser. To detect CAR expression, cells were detached from dishes with EDTA, spun down, resuspended in 1% fetal bovine serum-PBS at 2 × 105 cells/ml, and incubated with monoclonal antibodies against CAR (RmcB; a kind gift from Jeffrey Bergelson, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pa.) (2, 8) for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were pelleted, washed, and resuspended with R-phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 45 min at 4°C, prior to FACS analysis.

Binding assays.

The studies were performed as previously described (21). CHO cells were transfected with AdhCAR previously prepared with CaPi as described above. Forty-eight hours after CAR transfection, transfected or nontransfected cells were incubated for 1 h on ice with equal amounts of 3H-labeled Ad5GFP, Ad5GFPf30, or wild-type Ad30 particles in 1 ml of ice-cold MEM. Cells were washed twice with 1 ml of ice-cold MEM and harvested with trypsin, and the cell-associated radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of human Ad30 fiber gene has been deposited in GenBank by Lane Law under accession no. AF447393.

RESULTS

The Ad30 fiber gene.

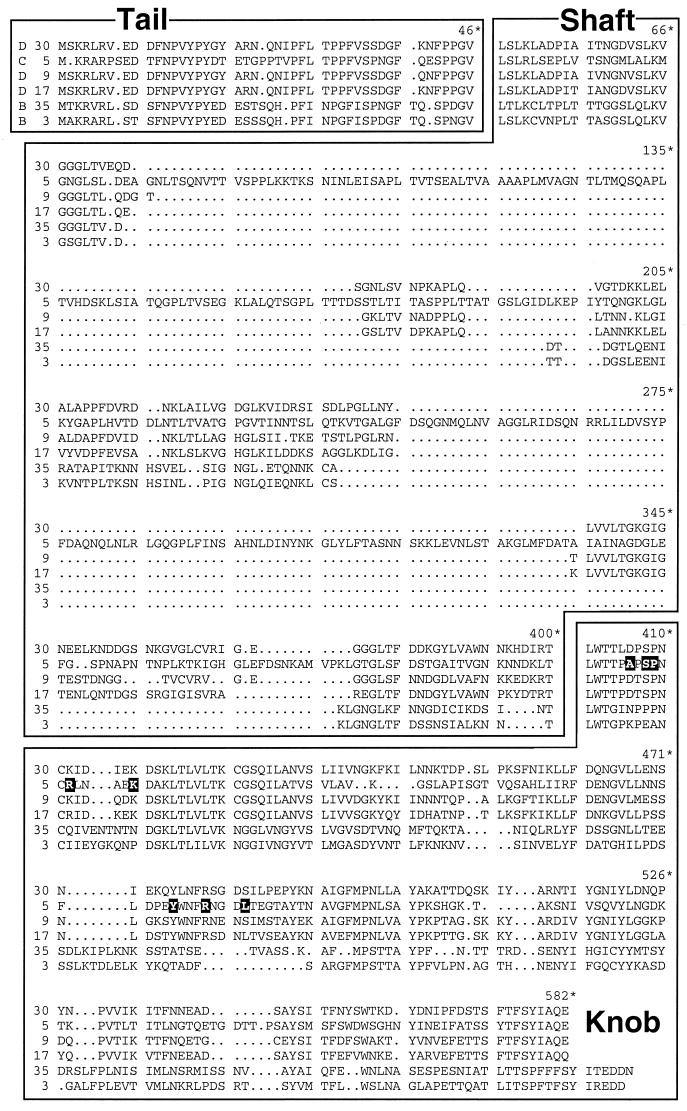

A study of the properties of the Ad30 fiber necessitated cloning and sequencing of the gene. Ad30 genomic DNA was isolated from wild-type particles, which had been propagated in HEK 293 cells and purified. The fiber gene was amplified by means of degenerate primers based on the known sequences of other D-serotype fibers. As sequence data were acquired, further specific primers were designed and employed until the entire sequence of the Ad30 fiber gene was obtained. The amino acid sequence of Ad30 is shown in Fig. 1. Ad30 fiber is very similar to other known D-serotype fibers, namely, Ad9 and Ad17, and less so to Ad3 or Ad35 fiber. We found the most divergence between Ad30 and Ad5 fibers.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of adenoviral fibers from the subgroup D Ads (serotypes 30, 9, and 17) with those from subgroup C (serotype 5) and subgroup B (serotypes 35 and 3). The amino acid positions are based on those of Ad5. Blocked letters indicate amino acids found to be important for CAR binding (residues at positions 406, 408, 409, 412, 417, 477, 481, and 485, based on the Ad5 protein sequence).

At the protein level, Ad30 fiber shares 25% overall identity with Ad5 fiber. When analyzed according to regions within the fiber protein, 61, 11, and 45% identities were found in the tail, shaft, and knob regions, respectively. The 11% identity in the shaft region resulted primarily from differences in the shaft lengths of the two fibers. Ad30 fiber is 209 amino acids shorter than Ad5. In contrast, 98, 55, and 66% identities were found between the Ad30 and Ad9 tail, shaft, and knob regions, respectively. Ad30 fiber was 66% identical to the Ad9 fiber.

Recent work investigated the binding of recombinant fibers to immobilized CAR and found specific residues important in CAR binding (9, 10, 13). Of the four residues shown to be critical for CAR binding (Ser408, Pro409, Tyr477, and Leu485), all but one (Leu485) were conserved in Ad30 fiber (10, 13). Of the three amino acid residues which may peripherally affect CAR binding, (Ala406, Arg412, and Arg481), only one (Arg481) has been conserved. These similarities and differences are illustrated in Fig. 1.

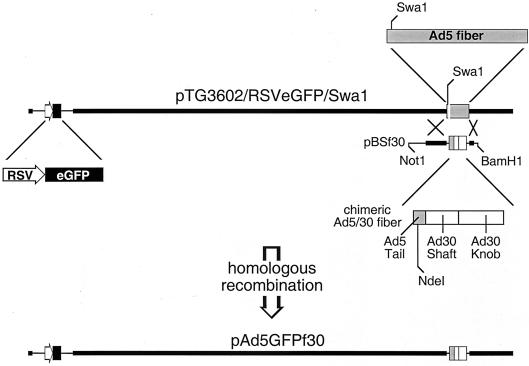

Chimeric fiber.

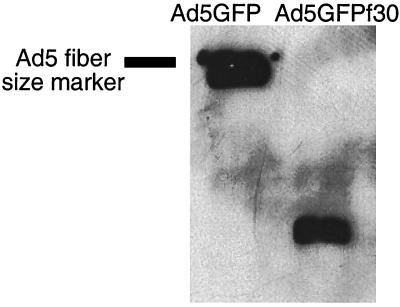

To test the properties of the Ad30 fiber independent of the Ad30 virion, a chimeric virus (Ad5GFPf30) was generated by homologous recombination in E. coli. (1). The Ad30 fiber gene was generated by overlapping PCR and, similar to earlier work with Ad17 fiber (5), was designed to retain the Ad5 tail and replace Ad5 shaft and knob sequences with those from Ad30. The fiber fragment was cloned into the Ad5 backbone in place of the endogenous Ad5 fiber as depicted in Fig. 2. Sequence analysis of plasmid pAd5GFPf30 confirmed the presence of the chimeric fiber. pAd5GFPf30 was linearized by PacI and transfected into HEK 293 cells to generate virus (1). Western blot analysis of purified particles verified the expression of the shortened chimeric fiber (Fig. 3). Ad5GFPf30-induced CPE was delayed relative to that of Ad5GFP (45 versus 30 h), and viral yields (numbers of particles and infectious units) were lower by two- to threefold. The titer of Ad5GFPf30 was 4 × 109 PFU/ml, and that for Ad5GFP was 1 × 1010 PFU/ml.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of homologous recombination in BJ5183 cells to generate pAd5GFPf30.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of Ad5GFP and Ad5GFPf30 fibers by Western blot analysis. Purified Ad5GFP and Ad5GFPf30 were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and viral proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated with a primary antibody to the N terminus of Ad5 fiber and then with a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Membranes were developed with enhanced-chemiluminescence reagent. The gel is representative of at least three independent experiments from different viral isolates.

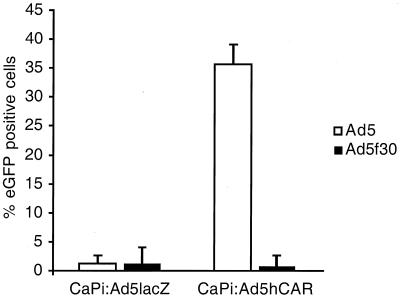

Ad5 has been shown to infect cells via CAR (2, 6, 14, 20, 23). To assess the potential use of CAR by the hybrid virus, CHO cells were used. This cell type has been shown to express little if any endogenous receptor (16, 18) but, when made to express CAR, can direct Ad5-mediated gene transfer. Ad5GFP infected 1% of control-virus-transfected CHO cells (Fig. 4), confirming previously published data (2, 18). Similar results were seen with Ad5GFPf30 (Fig. 4). To convert to a CAR-expressing phenotype, CHO cells were incubated with an Ad5hCAR-CaPi coprecipitant for 30 min at 37°C, resulting in 96% of cells being positive for CAR expression as determined by FACS analysis (data not shown). CAR expression resulted in significant increases in Ad5GFP-mediated gene transfer, from 1 to 36% of GFP-positive cells. In contrast, the introduction of CAR had no appreciable impact on the level of infection efficiency of Ad5GFPf30, which remained at ≤1% (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

The effects of CAR expression on Ad5GFP- and Ad5GFPf30-mediated transduction. CHO cells were transfected with Ad5lacZ- or Ad5hCAR-CaPi coprecipitants as described in Materials and Methods. Twenty-four hours later, transfected cells were infected with Ad5GFP or Ad5GFPf30 (500 particles/cell) for 30 min at 37°C, followed by a 24-h incubation. Cells were subsequently harvested, and GFP expression was analyzed by FACS analysis. Data are means ± standard deviations from two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

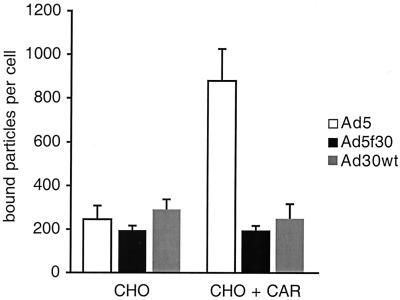

Binding studies were done to determine if the lack of transduction of CAR-expressing CHO cells was due to limited binding or to inhibited entry. Ad5GFP, Ad5GFPf30, and wild-type Ad30 were metabolically labeled with [methyl-3H]thymidine and applied to CHO cells or CHO cells that had been transfected by the Ad5hCAR-CaPi coprecipitant as described above. Cells were incubated with equivalent numbers of labeled particles, and unbound virus was removed. While the presence of CAR resulted in a 3.6-fold increase in bound Ad5GFP particles, CAR expression had no effect on Ad5GFPf30 or wild-type Ad30 binding (Fig. 5). These data indicate that Ad5GFPf30 and wild-type Ad30 do not bind CAR.

FIG. 5.

Effect of CAR on the binding of wild-type Ad30, Ad5GFPf30, and Ad5GFP to CHO cells. CHO cells were transfected with AdhCAR, as described in the legend to Fig. 4, or mock transfected. Cells were then incubated with 3H-labeled Ad5GFP, Ad5GFPf30, or wild-type Ad30 (Ad30wt) for 1 h on ice. Cell-associated radioactivity was determined, and the number of viral particles bound per cell was calculated. The data are means ± standard deviations and are representative of five independent experiments. Two independent viral isolations were used in these experiments.

DISCUSSION

We cloned, sequenced, and analyzed Ad30 fiber for its ability to bind CAR. A direct amino acid sequence comparison of Ad30 fiber with that from Ad5 demonstrated disparate as well as highly homologous regions. Sequences within the tail were most conserved, followed by the knob region. Within the knob, there was surprising conservation of amino acid sequences, and in the region of the knob shown to be important in CAR binding by competitive or cell-free surface plasmon resonance assays (10, 13), there were homologous or conservative amino acid substitutions in seven of nine instances. We presumed that this would allow Ad30 fiber-directed binding of Ads to CAR. When we tested wild-type Ad30 or a recombinant Ad5 virus with its endogenous fiber shaft and knob sequences replaced with those from Ad30, we found that Ad30 fiber does not bind CAR.

Within the knob, residues Ser408, Pro409, Lys417, Lys420, Tyr477, and Arg481, shown to be important in CAR binding, were found to be identical between Ad5 and Ad30. Mutations at Ala406, Arg412, and Leu485 of Ad5 diminish CAR binding (10). At these sites, Ad30 differs. However, these substitutions (Asp406, Lys412, and Asp485) are also present in Ad9 and/or Ad17, indicating that these changes alone are probably not sufficient for inhibiting binding to CAR.

More distinctive between Ad30 and the CAR-binding viruses are the amino acids surrounding these critical regions. The Ala406 in Ad5 or the Asp406 in Ad30, Ad9, and Ad17 is an example. In Ad5, Ad9, and Ad17, there is an invariable proline at amino acid position 405 and a serine or threonine at position 407. Ad30 possesses a leucine and proline at positions 405 and 407, respectively. And although Tyr477 is conserved in Ad30, Ad5, Ad9, and Ad17, the residues flanking Tyr477 are distinct when Ad30 is compared to the CAR-binding fibers.

The Ad30 fiber shaft, similar to those of other D-serotype viruses, was found to be short relative to the Ad5 shaft. Nonetheless, we found significant homology for the first 70 amino acids, as well as for regions near the hinge regions, notably from residues at positions 378 to 400. Serotype B viruses Ad35 and Ad3 also have short shaft lengths relative to that of Ad5. A study by Shayakhmetov and Lieber suggests that shaft length is important in CAR binding for Ad5 and Ad9; when Ad5 or Ad9 knobs were placed onto shorter shafts, CAR interactions were impaired (15). However, fiber length was not critical for Ads entering cells via a non-CAR-dependent pathway, as was evident for Ad35 (15). The rationale for this difference is suggested to be a charge repulsion between the negatively charged region within hypervariable region 1 of Ad5 hexon and acidic proteins on the cell surface. The hexon sequence of Ad30 is not presently available. As such, it would be interesting to test if the Ad30 knob, placed onto a longer shaft, would ameliorate the inability of Ad5GFPf30 to bind CAR.

Ad30 wild-type and the chimeric AdGFPf30 viruses were propagated in HEK 293 cells at levels similar to each other but less efficiently than were Ad5 fiber-expressing viruses. It is possible that Ad30, like Ad9, is more dependent on penton base interactions with cell surface integrins for viral entry (10, 12), although the presence of RGD motifs in the Ad30 penton base is currently unknown. Similarly, the shorter shaft of the Ad30 fiber may allow for more appropriate contact between the Ad5 penton base on Ad5GFPf30 capsids and cell surface αv-integrins (12).

In summary, we sequenced and analyzed the fiber from Ad30, a D-serotype virus, and found it to possess characteristics different from those of previously reported D-serotype virus fibers. It does not bind CAR, although it retains many of the sequences within the knob region predicted to be involved in CAR binding. We speculate that the Ad30 fiber may be advantageous for directing gene transfer to non- or low-level-CAR-expressing cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine McLennan for assistance with the manuscript and Maria Scheel, University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core, for assistance with viral production and assays.

This work was supported by the NIH and the Carver Trust (HL07638-15, DK54759, and HD33531).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, R. D., R. E. Haskell, H. Xia, B. J. Roessler, and B. L. Davidson. 2000. A simple method for the rapid generation of recombinant adenovirus vectors. Gene Ther. 7:1034–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergelson, J. M., J. A. Cunningham, G. Droguett, E. A. Kurt-Jones, A. Krithivas, J. S. Hong, M. S. Horwitz, R. L. Crowell, and R. W. Finberg. 1997. Isolation of a common receptor for coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 275:1320–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergelson, J. M., A. Krithivas, L. Celi, G. Droguett, M. S. Horwitz, T. Wickham, R. L. Crowell, and R. W. Finberg. 1998. The murine CAR homolog is a receptor for coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses. J. Virol. 72:415–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bewley, M. C., K. Springer, Y.-B. Zhang, P. Freimuth, and J. M. Flanagan. 1999. Structural analysis of the mechanism of adenovirus binding to its human cellular receptor, CAR. Science 286:1579–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chillon, M., A. Bosch, J. Zabner, L. Law, D. Armentano, M. J. Welsh, and B. L. Davidson. 1999. Group D adenoviruses infect primary central nervous system cells more efficiently than those from group C. J. Virol. 73:2537–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freimuth, P., K. Springer, C. Berard, J. Hainfeld, M. Bewley, and J. Flanagan. 1999. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor amino-terminal immunoglobulin V-related domain binds adenovirus type 2 and fiber knob from adenovirus type 12. J. Virol. 73:1392–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honda, T., H. Saitoh, M. Masuko, T. Katagiri-Abe, K. Tominaga, I. Kozakai, K. Kobayashi, T. Kumanishi, Y. G. Watanabe, S. Odani, and R. Kuwano. 2000. The coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor protein as a cell adhesion molecule in the developing mouse brain. Mol. Brain Res. 77:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu, K.-H. L., K. Lonberg-Holm, B. Alstein, and R. L. Crowell. 1988. A monoclonal antibody specific for the cellular receptor for the group B coxsackieviruses. J. Virol. 62:1647–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby, I., E. Davison, A. J. Beavil, C. P. C. Soh, T. J. Wickham, P. W. Roelvink, I. Kovesdi, B. J. Sutton, and G. Santis. 1999. Mutations in the DG loop of adenovirus type 5 fiber knob protein abolish high-affinity binding to its cellular receptor CAR. J. Virol. 73:9508–9514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirby, I., E. Davison, A. J. Beavil, C. P. C. Soh, T. J. Wickham, P. W. Roelvink, I. Kovesdi, B. J. Sutton, and G. Santis. 2000. Identification of contact residues and definition of the CAR-binding site of adenovirus type 5 fiber protein. J. Virol. 74:2804–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullis, K. G., R. S. Haltiwanger, G. W. Hart, R. B. Marchase, and J. A. Engler. 1990. Relative accessibility of N-acetylglucosamine in trimers of the adenovirus types 2 and 5 fiber proteins. J. Virol. 64:5317–5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roelvink, P. W., I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1996. Comparative analysis of adenovirus fiber-cell interaction: adenovirus type 2 (Ad2) and Ad9 utilize the same cellular fiber receptor but use different binding strategies for attachment. J. Virol. 70:7614–7621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roelvink, P. W., G. M. Lee, D. A. Einfeld, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1999. Identification of a conserved receptor-binding site on the fiber proteins of CAR-recognizing adenoviridae. Science 286:1568–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roelvink, P. W., A. Lizonova, J. G. M. Lee, Y. Li, J. M. Bergelson, R. W. Finberg, D. E. Brough, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1998. The coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor protein can function as a cellular attachment protein for adenovirus serotypes from subgroups A, C, D, E, and F. J. Virol. 72:7909–7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shayakhmetov, D. M., and A. Lieber. 2000. Dependence of adenovirus infectivity on length of the fiber shaft domain. J. Virol. 74:10274–10286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shayakhmetov, D. M., T. Papayannopoulou, G. Stamatoyannopoulos, and A. Lieber. 2000. Efficient gene transfer into human CD34+ cells by a retargeted adenovirus vector. J. Virol. 74:2567–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevenson, S. C., M. Rollence, B. White, L. Weaver, and A. McClelland. 1995. Human adenovirus serotypes 3 and 5 bind to two different cellular receptors via the fiber head domain. J. Virol. 69:2850–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomko, R. P., R. Xu, and L. Philipson. 1997. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackieviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3352–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van’t Hoff, W., and R. G. Crystal. 2001. Manipulation of the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains alters cell surface levels of the coxsackie-adenovirus receptor and changes the efficiency of adenovirus infection. Hum. Gene Ther. 12:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, X., and J. M. Bergelson. 1999. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains are not essential for coxsackievirus and adenovirus infection. J. Virol. 73:2559–2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wickham, T. J., P. Mathias, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1993. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia, H., B. Anderson, Q. Mao, and B. L. Davidson. 2000. Recombinant human adenovirus: targeting to the human transferrin receptor improves gene transfer to brain microcapillary endothelium. J. Virol. 74:11359–11366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zabner, J., M. Chillon, T. Grunst, T. O. Moninger, B. L. Davidson, R. Gregory, and D. Armentano. 1999. A chimeric type 2 adenovirus vector with a type 17 fiber enhances gene transfer to human airway epithelia. J. Virol. 73:8689–8695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]