Abstract

The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) 2-kb latency-associated transcript (LAT) is a stable intron, which accumulates in cells both lytically and latently infected with HSV-1. We have used a tetracycline-repressible expression system to determine the half-life of the 2-kb LAT RNA intron in the human neuroblastoma cell line SY5Y. Using Northern hybridization analyses of RNA isolated from transiently transfected SY5Y cells over time after repression of LAT expression, we measured the half-life of the 2-kb LAT to be approximately 24 h. Thus, unlike typical introns that are rapidly degraded in a matter of seconds following excision, the 2-kb LAT intron has a half-life similar to those of some of the more stable cellular mRNAs. Furthermore, a similar half-life was measured for the 2-kb LAT in transiently transfected nonneuronal monkey COS-1 cells, suggesting that the stability of the 2-kb LAT is neither cell type nor species specific. Previously, we found that the determinant responsible for the unusual stability of the 2-kb LAT maps to the 3′ terminus of the intron. At this site is a nonconsensus intron branch point located adjacent to a predicted stem-loop structure that is hypothesized to prevent debranching by cellular enzymes. Here we show that mutations which alter the predicted stem-loop structure, such that branching is redirected, either reduce or abolish the stability of the 2-kb LAT intron.

Individuals infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) harbor a lifelong latent infection of neurons in the sensory ganglia, with occasional recurrences of an acute infection at the site of initial infection (for a review, see reference 47). In a latent infection of neurons, the HSV-1 latency-associated transcripts (LATs) are the only transcripts produced at readily detectable levels (12, 36, 39). Two major species of LAT are observed during a latent infection and have apparent molecular sizes of 2.0 and 1.5 kb (29, 36–39, 45). Expression of LAT, however, is not exclusive to latent infections, since the 2-kb LAT species is also expressed during acute infections with late-gene kinetics (37, 44). These RNAs are now known to be introns (14, 50), with the less abundant 1.5-kb LAT being encoded entirely within the 2-kb LAT (50). The high level of these LAT species within the nuclei of latently infected cells suggests that these introns are expressed at very high levels or are unusually stable. In fact, it has been shown that these introns are indeed unusually stable (21, 30, 48, 50). This is in contrast to typical cellular introns that are rapidly degraded following excision from the pre-mRNA (23).

The function of LAT during latent and acute infections is not known, although recent studies have shed light upon why the LAT intron is stable. Two independent studies have mapped the branch point of the 2-kb LAT intron to either a guanosine (50) or an adenosine (48) residue present within a nonconsensus branch point sequence. This nonconsensus branch point sequence is located immediately upstream of a potential stem-loop structure with a predicted ΔG of −39.7 kcal/mol (50). Although the precise branch point nucleotide is disputed, it is clear that the unusual branch point region and/or sequences within the stem-loop are required for stability of the intron (21). The mechanism of the stability is hypothesized to involve the inability of the intron lariat to be debranched in vivo (30, 49). In this regard, guanosine branch points are poor substrates for mammalian debranching activity and are debranched at approximately 50% of the rate for adenosine branch points in vitro (4). Furthermore, the stable stem-loop structure that potentially forms between the LAT intron branch point and its polypyrimidine tract may potentially mediate the unusual stability of this intron by further blocking the progression of debranching enzymes (21, 50).

Although the stability of the LATs has been confirmed (21, 50), a half-life value has not been measured. Here, we have employed a tetracycline-repressible system to measure the half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron in the human neuroblastoma cell line SY5Y. In contrast to most cellular introns (23), the HSV-1 2-kb LAT is extraordinarily stable, with a measured half-life of approximately 24 h, which is similar to the half-lives of the more stable cellular mRNAs. This stability is not cell type or species specific, because a half-life of approximately 24 h was measured in transiently transfected monkey COS-1 cells. However, the selected branch point does correlate with the stability of the intron. Specifically, a guanosine branch point intron is the most stable, a uridine or cytidine branch point is less stable, and an adenosine branch point is unstable.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Construction of plasmid pcDNA3/PstI-MluI was described previously (50). This construct contains the PstI-MluI fragment from HSV-1 strain F encompassing the 2-kb LAT coding region (see Fig. 2C). The pTet-LAT plasmid was constructed by inserting the HindIII-DraIII fragment of pcDNA3/PstI-MluI, which includes the entire PstI-MluI LAT fragment and the downstream polyadenylation signal of pcDNA3, into the corresponding sites of the pTet-Splice plasmid (Gibco-BRL). The plasmids pTet-CONS and pTet-BAM were produced similarly but using LAT fragments from the plasmids pCons and pBam, which were described previously (21). The mouse α-globin gene (GenBank accession no. NM-008218) was obtained by reverse transcription-PCR of RNA isolated from mouse liver and subcloned into the SalI and HindIII sites of pTet-Splice to generate pTet-globin. The pTet-IL-2 construct was produced by subcloning the full-length cDNA of interleukin 2 (IL-2) from pGEM4Z-IL-2 (9) into the HindIII and EcoRV sites of the pTet-Splice plasmid (Gibco-BRL).

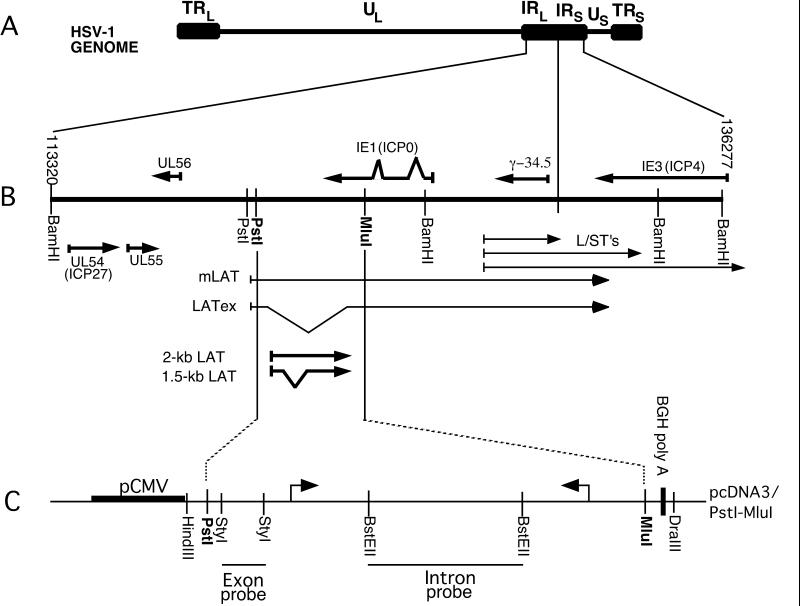

FIG. 2.

LAT locus of the HSV-1 genome. (A) The linear, 152-kb HSV-1 genome with the unique long (UL) and unique short (US) regions flanked by inverted repeat elements, called terminal repeat long (TRL), terminal repeat short (TRS), internal repeat long (IRL), and internal repeat short (IRS). (B) Enlargement of the LAT region of HSV-1 to show the different transcripts that map to this locus. (C) The pcDNA3/PstI-MluI minigene expression cassette. The PstI-MluI fragment harboring part of the LAT gene was cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector as described previously (50). Arrows represent splice donor and acceptor sites used to produce the 2-kb LAT. Relevant restriction enzyme sites and the DNA fragments used as probes in Northern hybridization analyses are indicated.

Cell culture and transfection of expression plasmids.

The human neuroblastoma cell line SY5Y (7) was grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, and COS-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum. Both cell lines were maintained in the presence of penicillin and streptomycin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

SY5Y cells (2.5 × 106) or COS-1 cells (1 × 106) were seeded into 60-mm-diameter dishes and grown overnight. The SY5Y and COS-1 monolayers at approximately 90% confluency were then transfected with 5 μg each of plasmids pTet-TAk and pTet-LAT (or pTet-Cons, -Bam, -globin, or -IL-2) using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. At 24 (SY5Y) or 16 (COS-1) h posttransfection, gene expression was repressed by incubating the cells in medium containing 3.0 (SY5Y) or 3.5 (COS-1) μg of tetracycline (Sigma) per ml, and RNA was isolated at the specified time postrepression as described below.

RNA extraction and Northern hybridization.

Total cell RNA was harvested directly from the dishes using Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL) as recommended by the manufacturer. Northern analyses were performed as previously described (36) with some modifications. Ten micrograms of RNA and 1 μg of RNA Millennium Size Markers (Ambion) were denatured in dimethyl sulfoxide and glyoxal and separated by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel. The RNA was stained with acridine orange to verify equal loading of samples and was vacuum blotted to a nylon membrane (GeneScreen Plus; NEN). The glyoxalation of RNA on the membrane was reversed by washing with boiling 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), followed by UV cross-linking (Stratalinker; Stratagene). DNA probes for the LAT region were subfragments of the HSV-1 strain F BamHI fragment B (27). These subfragments were generated by restriction digestion, isolated by gel electrophoresis, and purified. The positions of these fragments relative to the LAT locus are indicated below (see Fig. 2). The entire mouse α-globin and IL-2 cDNAs were used for their respective DNA probes. Membrane-bound RNA was hybridized to heat-denatured, random-primed 32P-labeled DNA probes overnight (36). Membranes were washed twice each in 1×, 0.5×, and 0.1× SSPE (1×SSPE is 180 mM NaCl, 10 mM monobasic sodium phosphate [pH 7.7], and 1.0 mM EDTA) with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 20 min at 65°C (24). Membranes were either exposed to Biomax film (Kodak) or exposed to phosphor screens (Molecular Dynamics) for the analyses described below.

Data analyses.

Northern blot membranes were exposed to phosphor screens (Molecular Dynamics), and the data were gathered using a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The data were analyzed using Imagequant version 1.2 for Macintosh (Molecular Dynamics) software. Volume reports were generated for the RNA of interest at each time point and for the “always tet” control. To account for the dilution of the RNA of interest due to continued cell division during the course of the experiment, volume reports were normalized by multiplying each point by e(t)ln2/tD (where t is the time of tetracycline repression, and tD is the doubling time of the cells) as described by Thanes et al. (41). Under our experimental conditions, where cells are nearly confluent at the start of the experiment, the doubling times for SY5Y cells and COS-1 cells are approximately 96 and 45 h, respectively. Since the “always tet” control represents background, or leaky, transcription, the normalized volume of this signal was subtracted from each time point value. These values were then expressed as a fraction of the normalized value at 0 h post-tetracycline repression. The results of two to four experimental samples were averaged and plotted using Cricket Graph version 1.5.1 (Computer Associates International, Inc., Islandia, N.Y.). A linear equation was generated using this software, and this equation was used to determine the approximate half-life of the RNA of interest. Regression analysis of the LAT half-life in SY5Y cells was performed using StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, Calif.).

RESULTS

A tetracycline-repressible gene expression system to measure RNA half-life.

A tetracycline-repressible gene expression system (17, 35) was employed to measure the stability of the 2-kb LAT intron in transiently transfected SY5Y cells. In this system, the gene of interest is subcloned into the pTet-Splice plasmid (Gibco-BRL) between a minimal hCMV immediate-early promoter regulated by the Tn10 tetracycline resistance operon (Tetp) and the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal from plasmid pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). This construct is cotransfected with the plasmid pTet-tTAk (Gibco-BRL), which encodes a fusion protein of the tetracycline DNA binding domain and the transactivation domain of HSV VP16, also under the control of Tetp. In the absence of tetracycline, the pTet-tTAk-encoded activator binds to operator sequences in Tetp and transcription of both genes occurs. In the presence of tetracycline, the activator cannot bind to the DNA strand, allowing only a low level of basal transcription to occur.

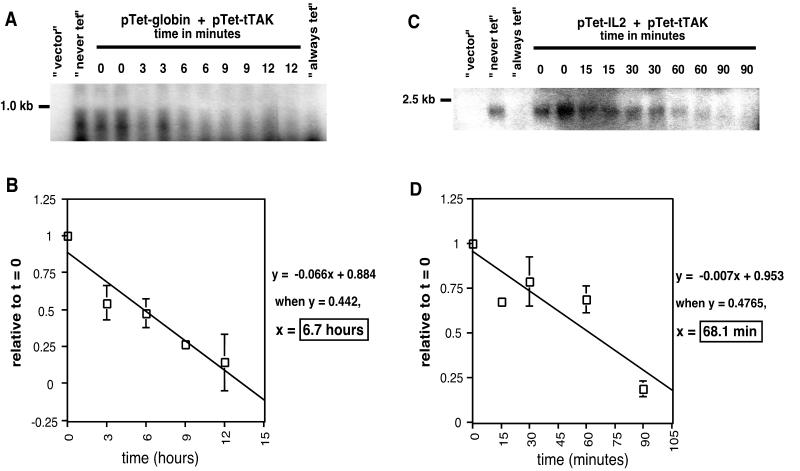

To determine whether this expression system would be useful for half-life measurements in a transient-transfection assay, we measured the half-lives of cellular transcripts with known half-lives. The α-globin mRNA, which has a known half-life of 15 to 60 h depending on the cell type used for analysis (20, 41), was chosen as an example of a stable cellular mRNA. As an example of a cellular mRNA with a very short half-life, we chose IL-2, which has a published half-life of 30 min to 2 h, also depending on cellular conditions (8, 34). The pTet-globin or pTet-IL-2 plasmid was cotransfected with pTet-tTAk into SY5Y cells and incubated for 24 h to allow transcripts to accumulate. RNA was isolated at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h or 0, 15, 30, 60, and 90 min post-tetracycline repression and analyzed by Northern blotting. Controls, harvested at the final time point, were transfected cells where transcription is never repressed with tetracycline (“never tet”), transfected cells where transcription is repressed beginning at the time of transfection throughout the course of the experiment (“always tet”), and cells transfected with pcDNA vector alone. Northern blots were hybridized to either an α-globin- or an IL-2-specific probe and visualized by autoradiography. Representative blots are shown in Fig. 1A and C. Specific radioactive transcript bands were quantitated using phosphorimager analyses and normalized as described in Materials and Methods. The mean level of each transcript at specific times is presented as a percentage of the transcript level at 0 h postrepression, and the graphed linear decrease in expression was used to determine the half-life (Fig. 1B and D). The average half-life of α-globin mRNA in SY5Y cells was determined to be 6.7 h (Fig. 1B), which is less than other reported half-lives in other cell types and culture conditions. This result suggests that for stable transcripts, half-life measurements using this tetracycline-repressible system may be underestimated. Consistent with published results, the average half-life of IL-2 mRNA in SY5Y cells was determined to be 68 min (Fig. 1D), suggesting that this system may more accurately measure the half-lives of less stable or unstable transcripts.

FIG. 1.

Half-lives of α-globin and IL-2 transcripts as measured with a tetracycline-repressible transient-transfection system. SY5Y cells were transfected with pTet-tTAk and pTet-globin or pTet-IL-2 and incubated for 24 h. Transcription was repressed with tetracycline, and RNA was isolated at the times indicated postrepression. (A and C) RNA was analyzed by Northern hybridization using either an α-globin-specific probe (A) or an IL-2-specific probe (C). The half-lives of α-globin and IL-2 were quantitated as described in Materials and Methods. (B and D) The mean levels of α-globin (n = 2 for t = 3 and 9 h; n = 4 for t = 0, 6, and 12 h) (B) and IL-2 (n = 2) (D) over time relative to 0 h or 0 min post-tetracycline repression are presented. Error bars represent standard deviations.

The half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron in transiently transfected SY5Y cells is 23.5 h.

Previous experiments, by our group and others, demonstrated that the HSV-1 2-kb LAT RNA is a stable intron readily detectable at 40 h post-transient transfection or 16 h postinfection (21, 30, 49, 50). To determine the half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron, we utilized the neuron-like human neuroblastoma cell line SY5Y (7).

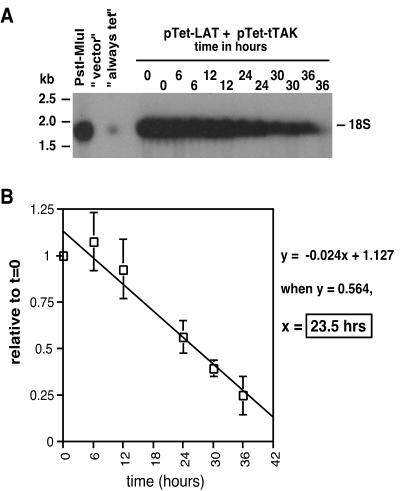

The plasmid pTet-LAT (Fig. 2) contains the PstI-MluI fragment of HSV-1 strain F, encompassing the 2-kb LAT intron. When transcribed, this PstI-MluI fragment expresses a truncated mLAT primary transcript, the 1.4-kb spliced exons of mLAT, and the 2-kb LAT intron (50). SY5Y cells were transfected with pTet-LAT and pTet-tTAk in the absence of tetracycline. Transcription was repressed by the addition of tetracycline at 24 h posttransfection, and total cellular RNA was harvested at 0, 6, 12, 24, 30, and 36 h postrepression. The controls “always tet,” “never tet,” and “vector” were harvested at 36 h after repression of transcription (60 h posttransfection). RNA purified from these cells was analyzed by Northern hybridization using a LAT intron-specific DNA probe (Fig. 3A). We should note that in our hands, the 2-kb LAT intron migrates faster than the 2-kb fragment of the RNA Millennium Size Markers (Ambion). The amount of LAT detected at each time point was determined using phosphorimager analysis and was normalized and quantitated as described above and in Materials and Methods. We also performed linear regression analysis of these data, which is presented in Fig. 3B. The r2 value obtained is very high (0.947), indicating that the decrease in relative levels of LAT over time is linear. From the generated linear curve, the average half-life of the 2-kb LAT in this neuronal-like cell line was determined to be 23.5 h, which indicates that this intron is extraordinarily stable and confirms previous observations (21, 30, 49, 50).

FIG. 3.

Half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron in transiently transfected SY5Y cells. SY5Y cells were transfected with plasmids pTet-tTAk and pTet-LAT. LAT expression was repressed by the addition of tetracycline at 24 h posttransfection, and total RNA was isolated from cells at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 h post-tetracycline repression. (A) RNA was analyzed by Northern hybridization, and the amount of 2-kb LAT detected at each time point was determined and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Mean level of 2-kb LAT (n = 3) over time relative to that at 0 h postrepression. Regression analysis of these data (r2 value) is indicated. Error bars represent standard deviations.

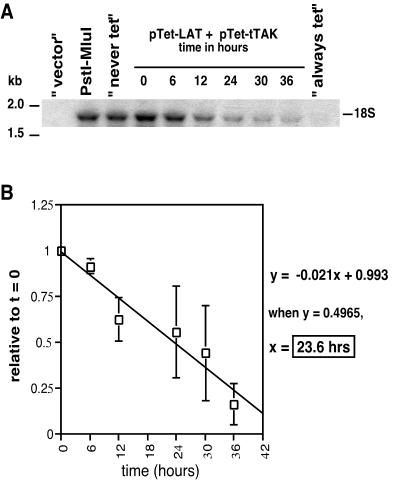

The half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron is not cell type specific.

To examine whether the long half-life of the 2-kb LAT is specific to neuronal-like cells, COS-1 monkey kidney cells were transfected, similarly to the human SY5Y cells, and transcription was repressed at 16 h posttransfection. As with SY5Y cells, COS-1 cells were harvested at 0, 6, 12, 24, 30, and 36 h after repression with tetracycline, and controls were harvested at the final time point. LAT intron-specific RNAs were analyzed, normalized, and quantitated in a way similar to that for the SY5Y experiments, with the exception that a different doubling time for COS-1 cells was factored into the normalization (see Materials and Methods). A representative Northern blot is shown in Fig. 4A, and the compiled data and analyses are shown in Fig. 4B. Using the generated linear curve, the average half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron in COS-1 cells was determined to be 23.6 h. This number is very similar to the number calculated for the half-life of LAT in SY5Y cells and indicates that the stability of LAT is neither cell type nor species specific in these dividing cells.

FIG. 4.

Half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron in transiently transfected COS-1 cells. COS-1 cells were transfected as described for Fig. 3. (A) After 16 h, transcription was repressed and RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blotting and quantitated as described for Fig. 3. (B) Mean level of 2-kb LAT (n = 4, except for t = 36 h, where n = 2) over time relative to that at 0 h postrepression. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Mutations that alter the branch point selection site alter the half-life of the 2-kb LAT.

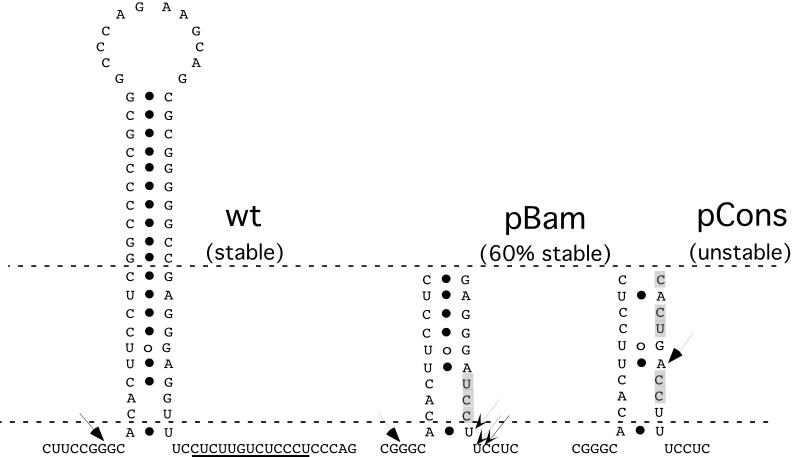

Previous experiments in our laboratory indicated that the stability of LAT is influenced by a putative stable stem-loop structure located between the nonconsensus branch point and the consensus polypyrimidine tract. It was hypothesized that this stem-loop dictates the location of the intron branch point (21). From these studies, we utilized two mutants with different stabilities, pCons and pBam (Fig. 5), in our tetracycline-repressible system to determine how these mutations affect the half-life of the 2-kb LAT. The sequences, proposed stem-loop structure, and proposed branch point selection sites of these two mutants in comparison to the wild type are illustrated in Fig. 5. The pCons mutant has five nucleotides in the base of the stem-loop mutated to generate a consensus branch point sequence, and this mutant intron is not detectable at 40 h posttransfection in COS-1 cells. The pBam mutation consists of three nucleotide substitutions at the base of the putative stem-loop and introduces a BamHI restriction enzyme site (21). This mutant intron was detected at 40 h posttransfection in COS-1 cells at levels approximately 60% of those of the wild-type 2-kb LAT (21). There were two possible hypotheses for this observation. First, all of the introns were less stable than the wild-type 2-kb LAT. Second, the reduced average stability could represent two populations of molecules: one that is stable and one that is unstable or less stable than the wild type.

FIG. 5.

Structures of the pCons and pBam mutants of the 2-kb LAT intron. Nucleotide differences are shaded. The branch points of the wild-type (wt) 2-kb LAT and of the two mutants, which are indicated with arrows (major branch point, thick arrows; minor branch points, thin arrows), were determined previously (21). The predicted stem-loop structure of the wild-type 2-kb LAT is illustrated. This stem-loop is conserved in both mutants but is not shown. The figure is adapted from reference 21.

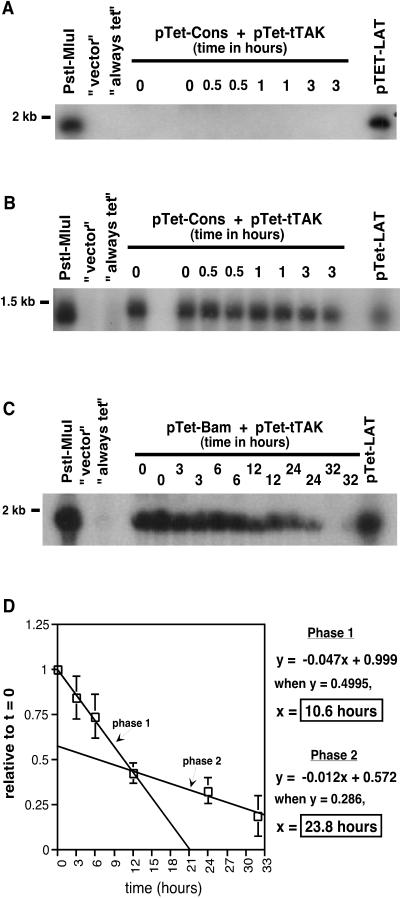

The pTet-Cons and pTet-Bam plasmids were cotransfected with pTet-tTAk into SY5Y cells as in the experiments described above. RNA was isolated at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h or at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 32 h post-tetracycline repression for pTet-Cons and pTet-Bam, respectively. Controls, harvested at the final time point, were “always tet” and “vector,” as well as pTet-LAT as a positive control never repressed with tetracycline. Consistent with previous results, the pTet-Cons mutant intron could not be detected at any time point during tetracycline repression (Fig. 6A). Stripping of this blot and rehybridizing with an exon-specific probe verified that transcription was indeed occurring from the pTet-Cons plasmid (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Half-life analyses of the Cons and Bam mutants of the 2-kb LAT intron. SY5Y cells were transfected with pTet-tTAk and pTet-Cons or pTet-Bam, and transcription was repressed with tetracycline as described for Fig. 3. (A and B) For the Cons mutant, Northern blot analyses for the 2-kb LAT intron were performed on RNAs isolated at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h postrepression (A). The blot was then stripped and rehybridized with a LAT exon-specific probe (see Fig. 2) to verify transcription (B). (C and D) For the Bam mutant, Northern blot analyses for the 2-kb LAT intron were performed on RNAs isolated at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 32 h postrepression (C). LAT-specific bands were analyzed and quantitated as described in Materials and Methods, and the mean level of the 2-kb LAT (n = 4) over time relative to that at 0 h postrepression is presented (D). Error bars represent standard deviations.

Unlike the pTet-Cons intron, the pTet-Bam intron was readily detectable during the course of the experiment (Fig. 6C). Intron bands were quantitated, normalized, and analyzed as described above for wild-type pTet-LAT. Interestingly, the graph generated appeared to be biphasic (Fig. 6D), suggesting the presence of two populations of 2-kb LAT with different stabilities. A linear curve and equation were generated for each phase (Fig. 6D). The average half-life for the first phase or population was determined to be 10.6 h. Strikingly, the average half-life of the second phase or population was determined to be 23.8 h, which is nearly identical to the half-life of the wild-type 2-kb LAT intron. The results confirm that some of the Bam mutant introns formed have wild-type stability and that some are less stable than the wild type but more stable than the Cons mutant.

DISCUSSION

The 2-kb LAT intron has long been postulated to be stable based on its striking abundance in HSV-1-infected cells, compared to the absence of detectable spliced exons of its pre-mRNA, mLAT (13, 14). Rodahl and Haarr (30) have previously examined the stability of the 2-kb LAT intron in productively infected PC12 cells by using the inhibitor actinomycin D. From the start of LAT gene transcription at 12 h postinfection until cell lysis at 24 h postinfection, no change in the amount of the 2-kb LAT intron was observed. This result suggested that the LAT intron is very stable, yet an RNA half-life measurement was not obtained.

Stability of RNAs can be affected by the different techniques utilized to measure RNA half-lives. Specifically, measurements of mRNA half-lives using inhibitors such as actinomycin D and inducible expression systems have been reported to be widely divergent (31). Here, we used a tetracycline-repressible system that was initially characterized with an immunoglobulin gene V(D)J recombination assay (17, 35). A similar transient-transfection tetracycline-repressible system was also previously employed for measuring the stability of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIa and rabbit α-globin mRNA (41). By using a tetracycline-repressible expression system, we have determined the average half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron to be approximately 24 h in transiently transfected SY5Y cells. Since most introns are rapidly degraded within seconds of release from spliceosomes in vivo (23), the stability of the 2-kb LAT intron by comparison is extraordinary. The half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron in cell culture is comparable to the half-lives of stable mRNAs such as actin (20) and globin (32, 41, 43), but the 2-kb LAT intron is not as stable as the rRNAs, which have half-lives of 60 h (43) (Table 1). In addition, because we determined a shorter half-life for α-globin mRNA than what others have reported, it is likely that the average half-life of the 2-kb LAT presented here is an underestimation.

TABLE 1.

Half-lives of cellular RNAs

Several factors may potentially affect the half-life of the 2-kb LAT intron. The stability of cellular mRNAs has been observed to be cell type specific in some cases (5, 6, 31). However, we did not detect a difference in the half-life of LAT between human neuron-like SY5Y cells and monkey COS-1 cells. Although the SY5Y cells were not terminally differentiated, in an undifferentiated state they express the dopamine-β-hydroxylase neurotransmitter at levels similar to those of rat cervical ganglia, as well as producing neurite processes, and are thus considered neuron like (7). Nevertheless, a difference in the stability of the 2-kb LAT between cells in culture and acutely or latently infected cells in the peripheral nervous system cannot be ruled out. For instance, Colgin et al. saw a rapid decrease in the number of neurons expressing LAT in cultured rat dorsal root ganglia induced to reactivate by either nerve growth factor (NGF) withdrawal or addition of forskolin (10), suggesting that LAT may have a shorter half-life in this context. However, those authors attribute this decrease to a down-regulation of the LAT promoter and not to stability of the 2-kb LAT RNA itself.

The stability of the 2-kb LAT may also be affected during productive infection by the presence of other viral proteins, perhaps in a cell type-specific manner. In this regard, the turnover of the 2-kb LAT intron may be different during productive infection compared to latent infection, since no viral protein expression has been detected during a latent infection. One viral protein which may affect the LAT stability is the virion shutoff protein, a tegument protein that disrupts cellular protein synthesis and increases the turnover of cellular and viral mRNAs (15, 16, 19, 33, 40). The virion shutoff protein has recently been demonstrated to possess an mRNase activity (possibly in conjunction with other factors) (51). If the 2-kb LAT intron is a substrate for this mRNase activity, LAT intron turnover may be increased. Alternatively, if LAT itself is not degraded by this mRNase, its stability could be enhanced relative to other mRNAs in the cell.

Results presented here (Fig. 6) and previously (21) clearly demonstrate that the branch point is essential for the stability of the 2-kb LAT. As evidenced by the Cons mutant, placement of a mammalian consensus branch point site at the base of the stem-loop favors branching of the LAT lariat at an adenosine and results in an unstable intron (21). For the Bam mutant, it was previously determined that the predominant branch point selected was a guanosine at the wild-type location, and it was postulated that 60% of introns produced branched at this location. In addition, three other branch point sites were also determined to be utilized on the opposite side of the stem-loop and were postulated to be the branch points of 40% of the introns produced (21). Two of these sites were uridines, and the third was a cytidine. Our results suggest that the presence of these three base pair changes in the stem-loop does not prevent wild-type stability in a fraction of the molecules. Instead, our results suggest that these three mutations can dictate changes in branching which significantly reduce the average stability of the intron. However, these misbranched introns, at the uridines or the cytidine, are not completely unstable like the Cons mutant or typical cellular introns, both of which branch at an adenosine nucleotide. Other cellular introns have been found to branch at nonadenosines as well. For example, the first intron of human growth hormone pre-mRNA branches at a cytidine (18), and the third intron of calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide branches at a uridine (1, 2). Although these introns do not appear to be unusually stable, the nonadenosine branch point of the intron is proposed to regulate splicing of the genes because selection of the nonadenosine branch point results in inefficient splicing (28).

The nonadenosine branching of the 2-kb LAT as a function to regulate the splicing of mLAT is not likely, since no protein products are detected from mLAT and the exon RNA itself from mLAT is not readily detectable. In addition, splicing occurs efficiently in the in vitro system described here (50). A more reasonable hypothesis is that one function of the nonadenosine branching, and thus the stable 2-kb LAT intron, may be to sequester cellular splicing factors to inhibit general cellular splicing. It has been proposed that the stable stem-loop structure of the 2-kb LAT intron may mediate the unusual stability of this intron by blocking the progression of debranching enzymes (21, 50). In this regard, our laboratory has recently discovered that the 2-kb LAT can be found associated with general splicing factors within the nuclei of both transfected and infected cells (3), yet this observation could also be indicative of the fact that the 2-kb LAT is a spliced intron.

Our results with the Bam and Cons mutants also indicate that modification of the stem-loop alters the stability of the 2-kb LAT intron, most likely by altering branch point selection (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, the integrity of the stem-loop may also influence the stability of 2-kb LAT in other fashions. In this regard, histone mRNA is stable, but in a cell cycle-dependent manner (46). Similar to the case for the 2-kb LAT intron, the mechanism of histone mRNA stability maps to a stem-loop structure at its 3′ end (25). This stem-loop, however, serves to regulate mRNA stability by binding to a cellular protein which itself is regulated by the cell cycle (46). A similar protein(s) may bind to the 2-kb LAT and influence debranching and/or the stability of the intron, and mutations such as Bam and Cons may affect the binding of this protein(s). Interestingly, if the half-life of the 2-kb LAT is actually similar in the cultured rat dorsal root ganglion reactivation model described above (10), then down-regulation of the LAT promoter alone would not account for the rapid decrease seen in LAT-positive neurons. Instead, the rapid decrease may indicate a role for an additional factor(s) to decrease the amount of LAT present.

Understanding the mechanism of LAT stability has potential implications for gene therapy applications. For instance, it might be possible to express a therapeutic gene that has a normally unstable transcript, such as IL-2, and increase its stability and thus its expression levels when expressed from within the LAT intron. However, we recently demonstrated that the 2-kb LAT intron did not serve as an mRNA in vitro for expression of the green fluorescent protein (22). A more promising possibility is using the 2-kb LAT splice donor and branch point-stem-loop region to increase the stability of therapeutic ribozymes. In particular, the hammerhead ribozyme has demonstrated promise for the use in treating viral diseases, such as that caused by human immunodeficiency virus, and genetic diseases, such as Marfan syndrome (reviewed in reference 26). Hammerhead ribozymes designed to cleave the multidrug resistance gene 1 as well as oncogenes like c-fos, H-ras, and HER2/neu have also shown potential for cancer treatment (reviewed in reference 42). These ribozymes can be delivered into cells by (i) in vitro synthesis followed by exogenous delivery or (ii) placement into an expression cassette followed by endogenous delivery via a virus or cationic lipids (42). Accordingly, problems arise for both these methods. Exogenously delivered ribozymes require chemical modifications to prevent degradation by cellular RNases. A problem for endogenously delivered ribozymes is that often the transcripts are not localized to the proper compartment where the target exists (i.e., nucleus versus cytoplasm) (42). By engineering these ribozymes to harbor the 2-kb LAT splice donor and branch point-stem-loop regions, it may not be necessary to extensively chemically modify the ribozymes to increase their stability and/or prevent their degradation. In addition, since the 2-kb LAT localizes to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm of cells, directing a ribozyme containing LAT sequences to its proper target within the cell might be facilitated. Certainly, using the 2-kb LAT stability elements to potentially enhance stability of ribozymes and, ultimately, enhance their effectiveness is an avenue worth exploring.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tulia Lindsten for generously contributing her pGEM4Z-IL-2 plasmid. We also thank the Fraser laboratory for helpful discussions and Jennifer Kent and William Giang of the Fraser laboratory for technical assistance.

D.L.T. and M.L. were supported by NIH training grant T23 AI07324. This work was supported by Public Health Service Program project grant N533768 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adema, G. J., R. A. L. Bovenberg, H. S. Jansz, and P. C. Baas. 1988. Unusual branch point selection involved in splicing of the alternatively processed calcitonin/CGRP-1 pre-mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:9513–9526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adema, G. J., K. L. vonHulst, and P. D. Baas. 1990. Uridine branch acceptor is a cis-acting element involved in regulation of the alternative processing of calcitonin/CGRP-1 pre-mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5365–5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed, M., and N. W. Fraser. 2001. Herpes simplex virus type 1 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript intron associates with ribosomal proteins and splicing factors in vivo. J. Virol. 75:12070–12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arenas, J., and J. Hurwitz. 1987. Purification of a RNA debranching activity from HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 262:4274–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastos, R. N., and H. Aviv. 1977. Theoretical analysis of a model for globin messenger RNA accumulation during erythropoiesis. J. Mol. Biol. 110:205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastos, R. N., Z. Volloch, and H. Aviv. 1977. Messenger RNA population analysis during erythoid differentiation: a kinetical approach. J. Mol. Biol. 110:191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biedler, J. L., S. Roffler-Tarlov, M. Schachner, and L. S. Freedman. 1979. Multiple neurotransmitter synthesis by human neuroblastoma cell lines and clones. Cancer Res. 38:3751–3757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bill, O., C. G. Garlisi, D. S. Grove, G. E. Holt, and A. M. Mastro. 1994. IL-2 mRNA levels and degradation rates change with mode of stimulation and phorbol ester treatment of lymphocytes. Cytokine 6:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark, S. C., S. K. Arya, F. Wong-Staal, M. Matsumoto-Kobayashi, R. M. Kay, R. J. Kaufman, E. L. Brown, C. Shoemaker, T. Copeland, S. Oroszlan, K. Smith, M. G. Sarngadhran, S. G. Lindner, and R. C. Gallo. 1984. Human T-cell growth factor: partial amino acid sequence, cDNA cloning, and organization and expression in normal and leukemic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:2543–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colgin, M. A., R. L. Smith, and C. L. Wilcox. 2001. Inducible cyclic AMP early repressor produces reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in neurons in vitro. J. Virol. 75:2912–2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dani, C., J. M. Blanchard, M. Piechaczyk, S. El Sabouty, L. Marty, and P. Jeanteur. 1984. Extreme instability of myc mRNA in normal and transformed human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7046–7450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deatly, A. M., J. G. Spivack, E. Lavi, and N. W. Fraser. 1987. RNA from an immediate early region of the HSV-1 genome is present in the trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:3204–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobson, A. T., F. Sederati, G. Devi-Rao, J. Flanagan, M. J. Farrell, J. G. Stevens, E. K. Wagner, and L. T. Feldman. 1989. Identification of the latency-associated transcript promoter by expression of rabbit beta-globin mRNA in mouse sensory nerve ganglia latently infected with a recombinant herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 63:3844–3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell, M. J., A. T. Dobson, and L. T. Feldman. 1991. Herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is a stable intron. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:790–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenwick, M. L., and M. M. McMenamin. 1984. Early virion associated suppression of cellular protein synthesis by herpes simplex virus is accompanied by inactivation of mRNA. J. Gen. Virol. 65:1225–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenwick, M. L., and M. J. Walker. 1978. Suppression of the synthesis of cellular macromolecules by herpes simplex virus. J. Gen. Virol. 41:37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gossen, M., and H. Bujard. 1992. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5547–5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmuth, K., and A. Barta. 1988. Unusual branch point selection in processing of human growth hormone pre-mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:2011–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krikorian, C. R., and G. S. Read. 1991. In vitro mRNA degradation system to study the virion host shutoff function of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 65:112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krowczynska, A., R. Yenofsky, and G. Brawerman. 1985. Regulation of messenger RNA stability in mouse erythroleukemia cells. J. Mol. Biol. 181:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krummenacher, C., J. M. Zabolotny, and N. W. Fraser. 1997. Selection of a nonconsensus branch point is influenced by an RNA stem-loop structure and is important to confer stability to the herpes simplex virus 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript. J. Virol. 71:5849–5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lock, M., C. Miller, and N. W. Fraser. 2001. Analysis of protein expression from within the region encoding the 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:3413–3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore, M. J., C. C. Query, and P. A. Sharp. 1993. Splicing of precursors to messenger RNAs by the spliceosome, p.1–30. In R. F. Gesteland and J. F. Atkins (ed.), The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Nicosia, M., J. M. Zabolotny, R. P. Lirette, and N. W. Fraser. 1994. The HSV-1 2 kb latency-associated transcript is found in the cytoplasm comigrating with ribosomal subunits during productive infection. Virology 204:717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandey, N. B., and W. F. Marzluff. 1987. The stem-loop structure at the 3′ end of histone mRNA is necessary and sufficient for regulation of histone mRNA stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:4557–4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phylactou, L. A., M. W. Kilpatrick, and M. J. A. Wood. 1998. Ribozymes as therapeutic tools for genetic disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7:1649–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Post, L. E., A. J. Conley, E. S. Mocarski, and B. Roizman. 1980. Cloning of reiterated and nonreiterated herpes simplex virus 1 sequences as BamHI fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:4201–4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Query, C. C., S. A. Strobel, and P. A. Sharp. 1996. Three recognition events at the branch-site adenine. EMBO J. 15:1392–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rock, D. L., A. B. Nesburn, H. Ghiasi, J. Ong, T. L. Lewis, J. R. Lokensgard, and S. M. Wechsler. 1987. Detection of latency related viral RNAs in trigeminal ganglia of rabbits latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 61:3820–3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodahl, E., and L. Haarr. 1997. Analysis of the 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript expressed in PC12 cells productively infected with herpes simplex virus type 1: evidence for a stable, nonlinear structure. J. Virol. 71:1703–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross, J. 1995. mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol. Rev. 59:423–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross, J., and T. D. Sullivan. 1985. Half-lives of beta and gamma globin messenger RNAs and of protein synthesis capacity in cultured human reticulocytes. Blood 66:1149–1154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schek, N., and S. L. Bachenheimer. 1985. Degradation of cellular mRNAs induced by a virion-associated factor during herpes simplex virus infection of Vero cells. J. Virol. 55:601–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw, J., K. Meerovitch, R. C. Bleackley, and V. Paetkau. 1988. Mechanisms regulating the level of IL-2 mRNA in T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 140:2243–2248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shockett, P., M. Difilippantonio, N. Hellman, and D. G. Schatz. 1995. A modified tetracycline-regulated system provides autoregulatory inducible gene expression in cultured cells and transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6522–6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spivack, J. G., and N. W. Fraser. 1987. Detection of herpes simplex type 1 transcripts during latent infection in mice. J. Virol. 61:3841–3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spivack, J. G., and N. W. Fraser. 1988. Expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts in the trigeminal ganglia of mice during acute infection and reactivation of latent infection. J. Virol. 62:1479–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens, J. G., L. Haar, D. Porter, M. L. Cook, and E. K. Wagner. 1988. Prominence of the herpes simplex virus latency associated transcript in trigeminal ganglia from seropositive humans. J. Infect. Dis. 158:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens, J. G., E. K. Wagner, G. B. Devi-Rao, M. L. Cook, and L. T. Feldman. 1987. RNA complementary to a herpes virus gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science 235:1056–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strom, T., and N. Frenkel. 1987. Effects of herpes simplex virus on mRNA stability. J. Virol. 61:2198–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thames, E. L., D. A. Newton, S. A. Black, and L. H. Bowman. 2000. Role of mRNA stability and translation in the expression of cytochrome c oxidase during mouse myoblast differentiation: instability of the mRNA for the liver isoform of subunit VIa. Biochem. J. 351:133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner. P. C. 2000. Ribozymes. Their design and use in cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 465:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volloch, V., and D. Housman. 1981. Stability of globin mRNA in terminally differentiating murine erythroleukemia cells. Cell 23:509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner, E. K., W. M. Flanagan, G. Devi-Rao, Y. F. Zhang, J. M. Hill, K. P. Anderson, and J. G. Stevens. 1988. The herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is spliced during the latent phase of infection. J. Virol. 62:4577–4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wechsler, S. L., A. B. Nesburn, R. Watson, S. M. Slanina, and H. Ghiasi. 1988. Fine mapping of the latency-related gene of herpes simplex virus type 1: alternate splicing produces distinct latency-related RNAs containing open reading frames. J. Virol. 62:4051–4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitfield, M. L., L.-X. Zheng, A. Baldwin, T. Ohta, M. M. Hurt, and W. F. Marzluff. 2000. Stem-loop binding protein, the protein that binds the 3′ end of histone mRNA, is cell cycle regulated by both translational and posttranslational mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4188–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitley, R. J. 1996. Herpes simplex virus, p.2297–2342. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 48.Wu, T. T., Y. H. Su, T. M. Block, and J. M. Taylor. 1998. Atypical splicing of the latency associated transcripts of herpes simplex type 1. Virology 243:140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, T. T., Y. H. Su, T. M. Block, and J. M. Taylor. 1996. Evidence that two latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 are nonlinear. J. Virol. 70:5962–5967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zabolotny, J. M., C. Krummenacher, and N. W. Fraser. 1997. The herpes simplex virus type 1 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript is a stable intron which branches at a guanosine. J. Virol. 71:4199–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zelus, B. D., R. S. Stewart, and J. Ross. 1996. The virion host shutoff protein of herpes simplex type 1: messenger ribonucleolytic activity in vitro. J. Virol. 70:2411–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]