Abstract

When tethered in cis to DNA, the transcriptional corepressor mSin3B inhibits polyomavirus (Py) ori-dependent DNA replication in vivo. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) appear not to be involved, since tethering class I and class II HDACs in cis does not inhibit replication and treating the cells with trichostatin A does not specifically relieve inhibition by mSin3B. However, the mSin3B L59P mutation that impairs mSin3B interaction with N-CoR/SMRT abrogates inhibition of replication, suggesting the involvement of N-CoR/SMRT. Py large T antigen interacts with mSin3B, suggesting an HDAC-independent mechanism by which mSin3B inhibits DNA replication.

The mammalian Sin3 (mSin3) transcriptional corepressor is associated with many distinct protein complexes, among which, the mSin3/histone deacetylases (HDAC)/RbAp48 complex is predominant (reviewed in references 4 and 59). This complex is recruited by unliganded nuclear hormone receptors through N-CoR/SMRT (nuclear receptor corepressor/silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptors) (2, 32, 34, 45, 57, 102), the methylated CpG-binding protein MeCP2 (40, 58), Mad/Max and Mxi/Max heterodimers (71), p53 (56), and other proteins (reviewed in reference 15) to repress the transcription of specific targets.

At least two forms of mSin3B are found in mammalian cells due to alternative mRNA splicing: the full-length mSin3B (mSin3BLF) containing four paired amphipathic α-helix (PAH) and a short form mSin3B (mSin3BSF) containing only the first two PAH domains and lacking the HDAC1/2-interacting domain (2). HDAC1 and -2 interact with mSin3A (or -B) protein through domains within the C terminus, starting at PAH3 (2, 92), and HDAC7 interacts with PAH1 of mSin3 (42), whereas HDAC5, as well as HDAC7, indirectly interacts with mSin3 through N-CoR/SMRT (37, 42). N-CoR/SMRT also acts as a corepressor in an mSin3-HDAC complex (2, 32, 34, 45, 57, 102). The L59P substitution in PAH1 impairs interaction with N-CoR/SMRT and partially reduces corepressor activity (2). Not all active Sin3 complexes require either HDAC activity or even the presence of HDACs (2, 41, 45, 92, 100).

HDAC-dependent p53-mediated transcriptional repression requires mSin3 (56, 103). The p53 protein also represses in vitro replication of simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA and polyomavirus (Py) DNA (19, 55, 82, 86) and nuclear DNA replication in the Xenopus egg extracts (14). Whether or not mSin3 is required for p53 mediated repression of DNA replication is not known.

HDAC complexes recruited by pRB to deacetylate histones and nonhistone proteins important for transcription also contain mSin3 (8, 46, 50, 51). pRB's control of cell cycle progression and DNA replication depends, at least in part, upon repressing transcription of E2F-regulated genes through both HDAC-dependent and -independent mechanisms (31, 46). That control of DNA replication by pRB might involve mechanisms besides transcriptional repression is suggested by observations including: (i) interaction of pRB with the replication-licensing factor MCM7 inhibits DNA replication in vitro (79); (ii) association of Drosophila pRB-E2F complex with origin recognition complex (ORC) restricts DNA amplification at the chorion gene replication origin (7, 68); and (iii) pRB inhibits Py ori-DNA replication by altering the phosphorylation state of Py large T antigen (PyLT) (65). Moreover, p107, a pRB-family protein, prevents the assembly of SV40 large T antigen at the origin, and the complex of p107 and SV40 large T antigen is unable to bind to DNA polymerase α, thereby inhibiting initiation of SV40 DNA replication (3).

Together with the recent finding that a subunit of mouse DNA polymerase ɛ can recruit the Sin3-HDAC corepressor complex to DNA (85), these observations suggest that Sin3-HDAC complexes might function to modulate DNA replication. However, direct roles of mSin3 in replication/origin function have not been examined. Here, we demonstrate that mSin3B strongly represses Py ori-DNA replication, but without a detectable requirement for HDACs. Rather, mSin3B and its mutants bind to PyLT in vivo, suggesting an HDAC-independent mechanism for inhibiting DNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

pBSPyΔE (Fig. 1A) contains at the XhoI site of pBluescript (Stratagene), Py sequences between nucleotide (nt) 4999 (AccI) and nt 372 (DraI) encompassing the Py origin with the viral enhancer (sequences between nt 5047 and 5291) replaced by an XhoI site. PBSPyGal (Fig. 1A) is a derivative of pBSPyΔE with five Gal4-binding sites from pG5-E4T (10) cloned at the XhoI site of pPyXhoI (93). pMKSO11 contains the entire Py genome with defective ori cloned in pMK16 (83).

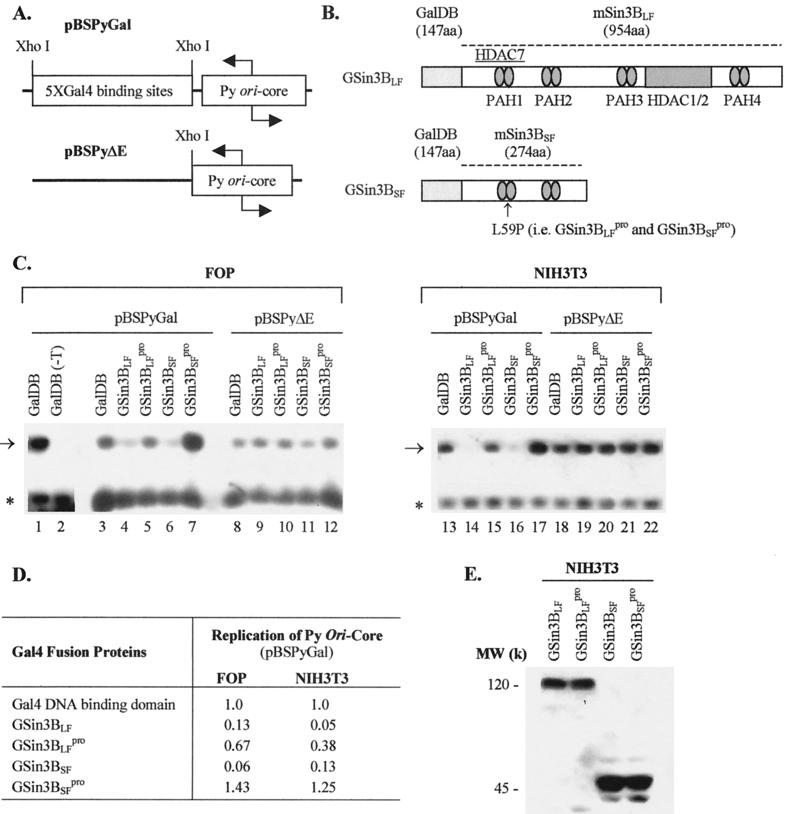

FIG. 1.

Analysis of Py ori-core DNA replication with mSin3B. (A) Structures of the origin regions of test plasmids used for replication assays. (B) Structures of mSin3B and its variants fused to Gal4 DNA-binding domains. Four paired amphipathic α-helix domains (PAH) of mSin3BLF and its interaction domains for HDAC1/2 and HDAC7 are indicated. mSin3BSF only contains the first two PAH domains. The proline substitution for leucine (L to P) at residue 59 that disrupts the interaction with the C terminus of N-CoR is noted. (C) Examples of replication assays performed with the test plasmids pBSPyGal and pBSPyΔE in FOP (left panel) and NIH 3T3 (right panel) cells. Test plasmids and cotransfected expression vectors are indicated above lanes. Additional amount of PyLT was provided by pMKSO11 for baseline replications with one exception indicated as GalDB (−T), where pMKSO11 was not cotransfected. The arrow and the asterisk, respectively, indicate the positions of replicated test DNA (upper band) and the nonreplicated test DNA as a reference (lower band). (D) Average from three independent transfection assays represented by panel C. (E) Protein expression of Gal4 fusion proteins in NIH 3T3 cells analyzed by Western blotting. The molecular weights of these proteins are indicated on the left side of the blot.

Expression vectors for Gal4 fusion mouse Sin3B proteins (Fig. 1B) and others include the following: pcDNA3GalDB for GalDB (93), pGalSin3BLF for GSin3BLF, pGalSin3BLFpro for GSin3BLFpro, pGalSin3BSF for GSin3BSF, pGalSin3BSFpro for GSin3BSFpro, pGalHDAC1 for GHDAC1, pGalHDAC2 for GHDAC2, pGalHDAC3 for GalHDAC3, pCMX-GalHDAC5 for GHDAC5, pCMX-GalHDAC7 for GalHDAC7, pCMX-GalNCoR-RD1 for GRD1, and pCMX-GalSMRT-RD3 for GRD3. Expression vectors for Gal4 fusion mouse Sin3B were described previously (2). Expression vectors for class I human HDACs (HDAC1 and -2) were described elsewhere (95). Original expression vectors for class II mouse HDACs (HDAC5 and -7) and pMH100-TK-Luc were kindly provided by R. M. Evans (18). The original expression vectors for GRD1 and GRD3 have been described (37). The Py origin was removed from the original pCMX-backboned vectors to prevent competition for replication proteins with test plasmids in in vivo DNA replication assays.

In vivo replication assays.

NIH 3T3 cells were seeded in 12-well plates (1.5 × 105 cells/well), and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were transfected by using Lipofectamine PLUS (Invitrogen) with expression plasmids (0.2 μg) for Gal4 fusion proteins and a test plasmid pBSPyGal4 (0.2 μg) containing the Py ori-core flanked by five Gal4-binding sites or pBSPyΔE (0.2 μg) containing only the Py ori-core (Fig. 1A). PyLT required for replication was provided by cotransfected pMKSO11 (0.08 μg). The total amount of DNA (0.48 μg) was kept constant by adding vector DNA if necessary. After incubation of the cells with a DNA-Lipofectamine PLUS mix for 4 to 5 h in 400 μl of serum-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM), the transfection solution was replaced with 1 ml of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum.

Similarly, FOP cells (1.5 × 106 cells/well), a mouse mammary carcinoma cell line that constitutively expresses PyLT (5), were transfected by using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) with expression plasmids (0.5 μg) for Gal4 fusion proteins and a test plasmid pBSPyGal4 (0.2 μg) or pBSPyΔE (0.2 μg) in 12-well plates. Expression of additional PyLT was achieved by cotransfection with pMKSO11 (0.5 μg). After the cells were incubated with DNA (1.2 μg)-Lipofectamine mix for 6 h in 350 μl of serum-free DMEM, 800 μl of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added.

The medium was changed at 12 h, and cells were incubated for another 24 h. Trichostatin A (TSA; Sigma, prepared as a 1-mg/ml solution in dimethyl sulfoxide), an HDAC inhibitor (98), was added to the medium to 100 ng/ml at 24 h after transfection, as indicated. DNAs were isolated by the Hirt procedure (36), digested with RNase A (0.2 μg/μl) and with EcoRI and HindIII to linearize plasmids, and with DpnI in the presence of 200 mM NaCl to distinguish methylated (input) DNA from unmethylated DNA replicated in animal cells (62, 69). The replicated DpnI-resistant DNA was resolved from DpnI-digested DNA by electrophoresis in an 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and detected by Southern blotting with probes generated from the test plasmid, labeled, and visualized by the North2South detection kit (Pierce). Transfection efficiencies were normalized by using DpnI-digested input nonreplicated test DNA. For analysis of protein expression, an identical set of transfections was performed, except without test plasmids. Cells were lysed with single-detergent lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1× Complete protease inhibitors [Roche], 1% Triton X-100) 36 h after transfection. Proteins in lysates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and expression of Gal4 fusion proteins was detected by Western blotting with anti-GalDB monoclonal antibody sc-510 (Santa Cruz, Inc.).

Luciferase reporter assays.

NIH 3T3 and FOP cells were transiently transfected as described above with expression plasmids for Gal4 fusion proteins, a reporter plasmid pMH100-TK-Luc (Fig. 2A), and an expression plasmid pRL-CMV (Promega; Fig. 2A) for Renilla luciferase as an internal control. TSA (100 ng/ml) was added to the medium at 24 h after transfection as indicated. At 40 to 48 h after transfection, extracts were prepared by using passive lysis buffer (Promega), and the luciferase activities were assayed according to the protocol from the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Luciferase activities were normalized with Renilla luciferase activities. All transfections were repeated at least three times. Luciferase activities were calculated relative to the basal activity of a transfected Gal4 DNA-binding domain (pcDNA3Gal4DB) set as 1, and the fold repression was determined as the reciprocal of each relative luciferase activity. Results were represented as the means and standard deviations of the fold repression from triplicates in each independent experiment. For analysis of protein expression, portions of the whole-cell extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE and expression of Gal4 fusion proteins was detected by Western blotting with anti-GalDB monoclonal antibody sc-510.

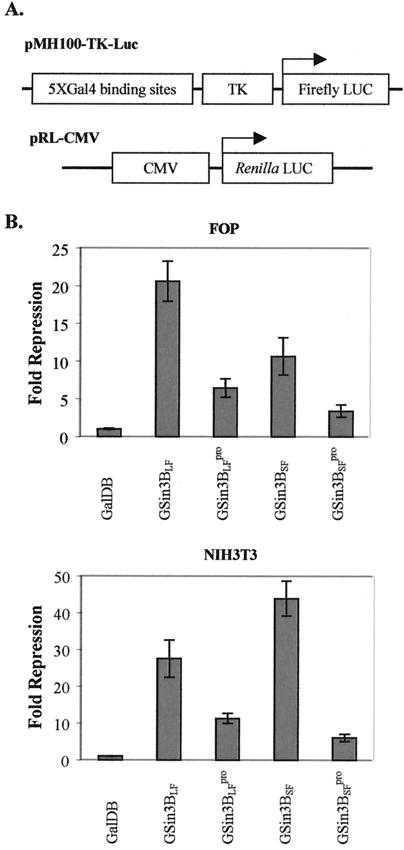

FIG. 2.

Repression of gene expression by mSin3B. (A) Structure of the test plasmids. pMH100-TK-Luc contains five Gal4-binding sites located upstream of the thymidine kinase (TK) promoter and the firefly luciferase gene as a reporter. pRL-CMV contains the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and Renilla luciferase gene as a reference for transfection assays. (B) Summary of data collected from the luciferase assays with mSin3B in FOP (top chart) and NIH 3T3 (bottom chart) cells. The luciferase assays were done with FOP and NIH 3T3 cell extracts prepared 36 to 48 h posttransfection as described in Materials and Methods. The fold repression from three independent transfection assays is shown as the mean ± the standard deviation. The fold repression for each protein is relative to that of GalDB alone.

ChIP assays.

Characterization of TSPy5 chromatin by microccocal nuclease (MNase) was performed as described by Kingston (44). TSPy5 (Fig. 5A) is an SV40 virus whose genome includes the Py ori-core and flanking five Gal4-binding sites (93). Accessibility of the Py ori-core in TSPy5 chromatin was analyzed by digestion with excess restriction endonucleases as described by Hermansen et al. (35). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described elsewhere (93). Briefly, Cos7 cells were infected for 1 h with SV40 virus containing TSPy5 DNA and then transfected with an expression plasmid (8 μg) for Gal4 fusion proteins by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Aphidicolin (Sigma; 10 μg/ml), a DNA polymerase inhibitor (26) was added to the medium to block DNA replication 16 h after transfection. After 24 h of additional incubation, cells were cross-linked with 11% formaldehyde cross-linking solution. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of 0.55 ml of 2.5 M glycine, and the cells were scraped and collected by centrifugation and then washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline plus 0.5 mM PMSF and resuspended in 120 μl of 5 mM PIPES (pH 8.0), 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 1× Complete protease inhibitors for 20 min on ice. The lysates were sonicated by using a Vibra-Sonicator and then digested for 10 min by MNase (0.5 U/μl) at room temperature to reduce the DNA length to between 200 and 1,000 bp. Debris was removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000 × g at 4°C, and the supernatant was diluted in 1.2 ml of IP buffer (0.01% SDS; 1.1% Triton X-100; 1.2 mM EDTA; 16.7 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1; 16.7 mM NaCl; 1 mM PMSF; and 1× Complete protease inhibitors). The chromatin solution was precleared with 50 to 80 μl of a 50% protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) slurry containing 0.2 μg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA/μl and 0.5 μg of bovine serum albumin/μl in TE (10 mM Tris; 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 0.05% sodium azide) for 30 min at 4°C with agitation. Sepharose beads were pelleted at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and 500 μl of supernatant was immunoprecipitated with 5 μg of anti-acetyl histone H3 and H4 polyclonal antibodies (Upstate) each for 12 h at 4°C with rotation. A portion of the supernatant (50 μl) was kept as an input chromatin control. Immune complexes were collected with 60 μl of 50% protein A-Sepharose slurry containing 0.2 μg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA/μl and 0.5 μg of BSA/μl in TE buffer for 1 h at 4°C with rotation. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed five times with washing buffers. Immune complexes were eluted by two washes with 250 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3). Then, 5 M NaCl (20 μl) was added to the combined eluates, and cross-links, including the input chromatin control, were reversed by incubation at 65°C for at least 4 h. Proteinase K (2 μl of 10 mg/ml) was added to the eluate and incubated for 1 h at 45°C. DNA was recovered by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation with 20 μg of glycogen as a carrier, denatured in 100 μl of denaturation solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaOH), and transferred onto nylon membranes by using a slot blot apparatus. Sequences from immunoprecipitated and input control DNAs were detected by using North2South detection kit with Py ori probe generated from the BamHI-MluI small fragment of TSPy5 and SV40 ori probe generated from BglI-NgoMI small fragment of TSPy5 (Fig. 5A).

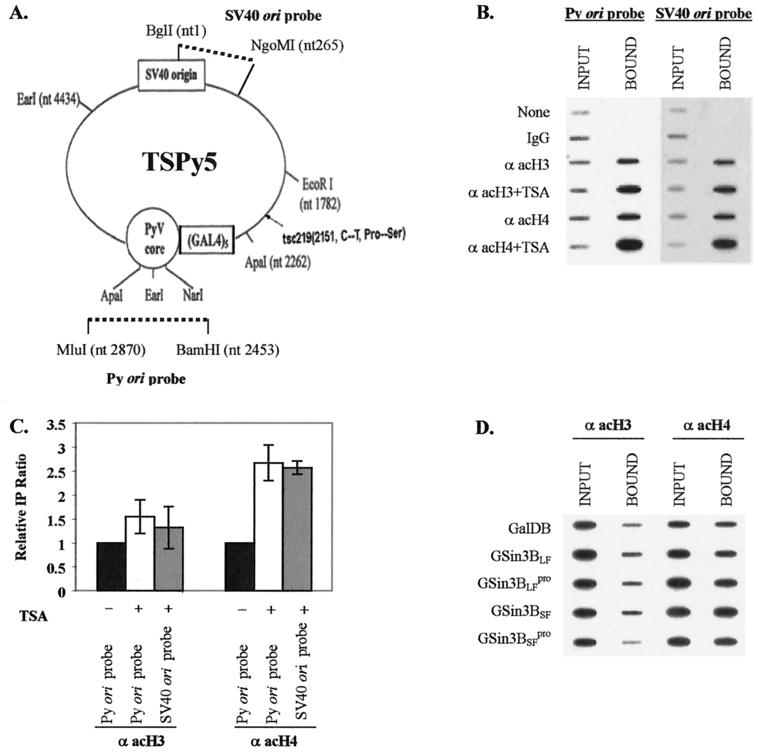

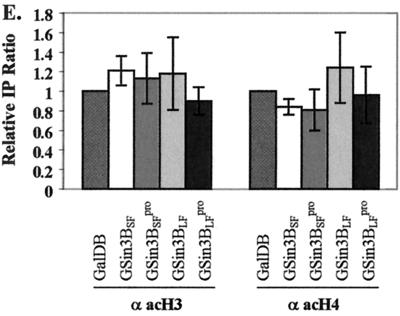

FIG. 5.

Acetylation changes of nucleosomal histones around Py ori-core with mSin3B. (A) Schematic representation of TSPy5 with location and orientation of the Py ori-core and adjacent Gal4-binding sites. Insertion position and orientation for the Py ori-core and adjacent Gal4-binding sites in the SV40 tsc219 genome are indicated. Fragments used to generate Py ori probe and SV40 ori probe for ChIP assays are indicated with broken lines. (B) Example of ChIP assays from TSA-treated or untreated cells. TSPy5 chromatin fragments immunoprecipitated with antiacetylated H3 and H4, and DNA input (INPUT) and DNA immunoprecipitated (BOUND) analyzed by Py ori and SV40 ori probes as indicated above the lanes. Antibodies used for ChIP assays and with or without TSA treatment are indicated to the left to the corresponding rows. (C) Average from three independent experiments represented in panel B. The immunoprecipitation (IP) ratio for each Gal4 chimera protein was calculated as the ratio of BOUND DNA intensity to INPUT DNA intensity quantified from slot blots. Relative IP ratio was measured by comparing each IP ratio relative to that (set as 1) for cells without TSA treatment. (D) Example of ChIP assays with mSin3B by using Py ori probe. DNA input (INPUT) and coimmunoprecipitated chromatin DNA (BOUND) with anti-acetyl H3 (α acH3) or H4 antibody (α acH4) analyzed by slot blot with Py ori probe are indicated above lane and Gal4 chimera proteins cotransfected are indicated at the left. (E) Average from three independent experiments represented in panel B. Relative IP ratio (mean value) was measured by comparing each IP ratio relative to that for GalDB set as 1. The standard deviation is indicated as a bar.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

NIH 3T3 cells (ca. 2.5 × 106) were transfected with expression vectors for Gal4 fusion proteins by using Lipofectamine PLUS in a 100-mm plate. After 36 h, the cells were extracted with 500 μl of single-detergent lysis buffer for 1 h at 4°C, and lysates were cleared by centrifugation twice at 13,000 × g for 10 min each. After we obtained 10 μl for a protein input control, we incubated the remaining supernatants with 10 μg of rabbit anti-GalDB polyclonal antibody sc-577 (Santa Cruz, Inc.) overnight at 4°C and collected the immune complexes by adding 80 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads and incubating samples for 2 h at 4°C, followed by five washes with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 4 mM NaF, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate). After the fifth wash, pelleted beads were suspended in 40 μl of 1× SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 100 mM dithiothreitol, 4% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) boiled for 10 min and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. Samples of 20 μl of the supernatant were removed for SDS-PAGE. After SDS-PAGE and the transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the bound T antigen was detected with mouse KF4 antibody (61) by Western blot analysis. For estimation of Gal4 fusion protein and PyLT expression, 20 μl of the whole-cell extract was resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting with anti-GalDB polyclonal antibody sc-577 and KF4, respectively, and subsequently incubated with secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, followed by chemiluminescence detection.

RESULTS

Inhibition of Py ori-dependent DNA replication by mSin3B.

Py ori-dependent DNA replication in the absence of an active enhancer and stimulatory enhancer-binding proteins requires the expression of very high amounts of PyLT to promote its efficient binding to the origin (30; W. J. Tang and W. R. Folk, unpublished data). In both FOP cells (that constitutively express PyLT) and NIH 3T3 cells, high-level expression of PyLT by pMKSO11 supports replication of pBSPyGal or pBSPyΔE (Fig. 1A) without the need of the enhancer or stimulatory enhancer binding proteins (Fig. 1C, lanes 1, 3, 8, 13, and 18). However, coexpression in these cells of either mSin3BLF or mSin3BSF as Gal4 fusion proteins (Fig. 1B) inhibited replication of pBSPyGal but not pBSPyΔE, which lacks Gal4-binding sites (Fig. 1C and D). The L59P mutation (i.e., GSin3BLFpro and GSin3BSFpro) that blocks interaction between mSin3B and N-CoR/SMRT (2) impaired or abolished the inhibitory effect, and for GSin3BSFpro even slightly stimulated DNA replication (Fig. 1C and D).

Western blot analysis demonstrated nearly equivalent levels of expression of both mSin3BLF or mSin3BSF and the L59P mutants in NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 1E), but their expression was not detected in FOP cells, possibly due to low transfection efficiency or protein instability.

The Gal4 mSin3B protein repressed expression of the firefly luciferase reporter gene in pMH100-TK-Luc (Fig. 2A and B), and repression by the L59P mutants (GSin3BLFpro and GSin3BSFpro) was reduced to some extent (Fig. 2B), indicating that these proteins are active transcriptional corepressors when expressed in FOP and NIH 3T3 cells.

Inhibition of Py ori-DNA replication by mSin3 does not require HDACs.

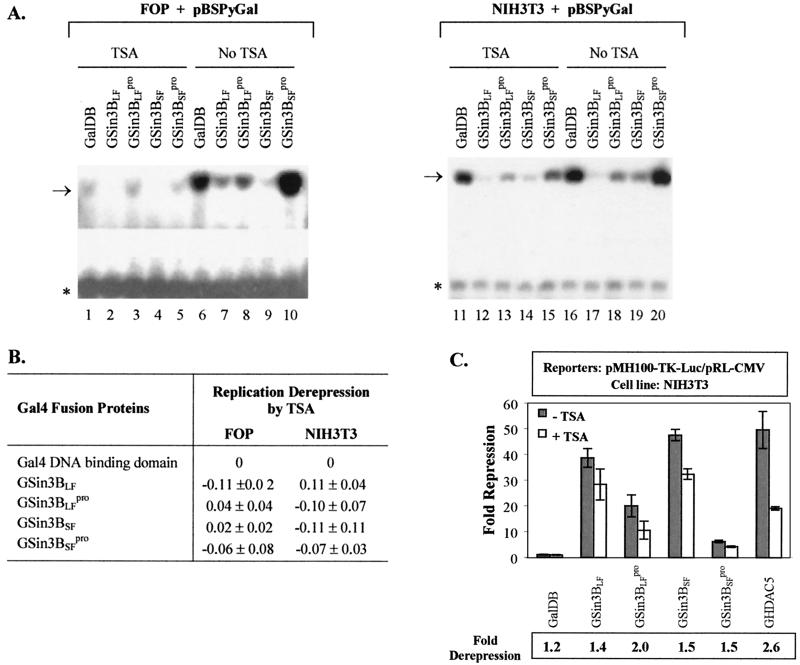

Treatment with inhibitors of HDACs, such as sodium butyrate or TSA, induces arrest of the cell cycle at the G1 checkpoint (43, 73; reviewed in references 81 and 99) and globally inhibits Py ori-DNA replication (73) in FOP cells (Fig. 3A). TSA treatment did not specifically relieve repression by mSin3B proteins of Py ori-DNA replication in either FOP or NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3A and B). These data suggest that HDACs are not involved in the inhibition of Py ori-DNA replication by mSin3B. In NIH 3T3 cells, mSin3BLF, mSin3BSF and mSin3BSFpro repression of luciferase expression was modestly relieved by TSA, which also reduced repression by HDAC5 (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Effects of TSA on repression of Py DNA replication by mSin3B. (A) Examples of replication assays performed with TSA treatment as described in Materials and Methods. Additional PyLT were provided by pMKSO11 for baseline replications in FOP and NIH 3T3 cells. Test plasmid pBSPyGal, treatments with or without TSA, and test proteins are indicated above lanes. The arrow and the asterisk, respectively, indicate the positions of replicated test DNA (upper band) and the nonreplicated test DNA as a reference (lower band). (B) Replication derepression measured from three independent transfection assays represented by panel A. Fold derepression for each Gal4 fusion protein was calculated as the ratio of the level of pBSPyGal replication with TSA treatment to that without treatment. Replication derepression by TSA, represented as the difference in fold derepression between each Gal4 fusion protein and GalDB alone, is shown as the mean ± standard deviation of values from three independent transfection assays. (C) Effects of TSA on repression of gene expression by repressors. Test proteins with (+) or without (−) TSA treatment are indicated along the x axis. The fold repression from three independent transfection assays is shown as the mean ± standard deviation. The fold repression for each protein is relative to that for GalDB alone, set as 1. The fold derepression for each protein, calculated as the ratio of luciferase expression with TSA treatment to that without TSA, is also shown as the average of values from three independent transfection assays.

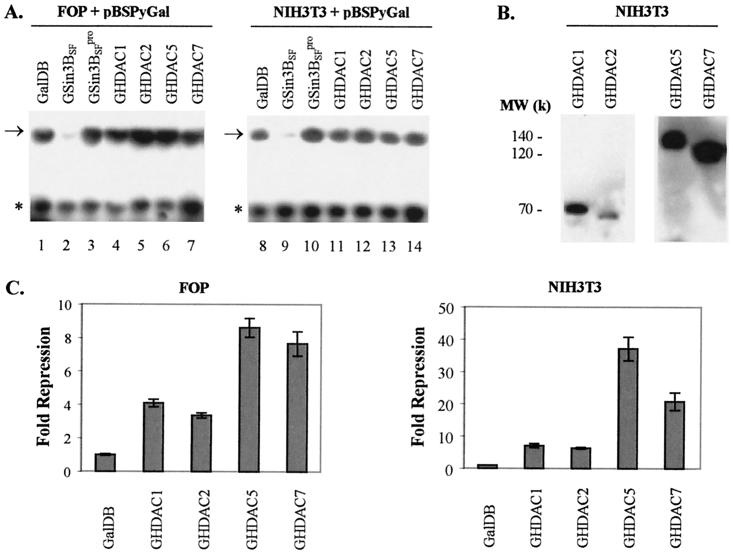

To further assess whether HDACs contribute to the inhibition of Py ori-core DNA replication by mSin3B, Gal4 fusion HDACs were tethered near the Py ori-core and replication measured. Neither class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1 and HDAC2) nor class II histone deacetylases (HDAC5 and HDAC7) tethered near the Py origin inhibited Py DNA replication in FOP and NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 4A). These Gal4 fusion HDACs were expressed in NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 4B), but their expression was not detected in FOP cells (data not shown). Furthermore, these proteins repressed gene expression of the firefly luciferase reporter in FOP and NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of Py ori-core DNA replication with histone deacetylases. (A) Examples of replication assays performed with HDACs in FOP (left panel) and NIH 3T3 (right panel) cells as described in Materials and Methods. PyLT provided by pMKSO11 was required for baseline replication in both cell lines. Test plasmid pBSPyGal and cotransfected expression vectors are indicated above lanes. The arrow and the asterisk, respectively, indicate the positions of replicated test DNA (upper band) and the nonreplicated test DNA as a reference (lower band). (B) Protein expression of Gal4 fusion proteins in NIH 3T3 cells. Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. Molecular weights of these proteins are indicated on the left side of the blot. (C) Summary of data collected from the luciferase assays with HDACs in FOP (left chart) and NIH 3T3 (right chart) cells. The fold repression from three independent transfection assays is shown as the mean ± the standard deviation. The fold repression for each protein is relative to that of GalDB alone.

To directly address whether deacetylation around the Py ori-core is involved in inhibition of Py DNA replication by mSin3B, ChIP assays were performed with an SV40 virus whose genome contained the Py origin sequences (TSPy5, Fig. 5A ). MNase digestion of extracts of TSPy5 virus-infected Cos7 cells has indicated that the TSPy5 genome is assembled into chromatin, and restriction enzyme analyses of TSPy5 minichromosomes have revealed that the Py ori-core region is occupied by nucleosomes (data not shown).

To validate ChIP assays as a means to study TSPy5 chromatin acetylation, we analyzed whether TSA treatment of Cos7 cells infected with TSPy5 viruses changed the acetylation status of TSPy5 chromatin. HDAC inhibitors such as TSA cause hyperacetylation of core histones (especially H4) in cellular chromatin (reviewed in references 81 and 99) and SV40 minichromosomes (1). ChIP assays with probes for Py ori-core and SV40 ori demonstrated that the acetylation of H4 was increased by 2.6-fold, and acetylation of H3 slightly increased in TSPy5 minichromosomes extracted from TSA-treated cells, compared to minichromosomes from untreated cells (Fig. 5B and C; also see reference 93).

In contrast, we did not detect changes in H3 or H4 acetylation when either Gal4 mSin3B or its variants were introduced into Cos7 cells together with TSPy5 (Fig. 5D and E). Expression of these Gal4 chimeras was confirmed by Western slot blot analysis (data not shown). These results indicate that histone deacetylases active in FOP and NIH 3T3 cells have no direct effect on Py ori-core DNA replication and suggest that mSin3B inhibits DNA replication via alternative mechanisms.

mSin3B binds PyLT.

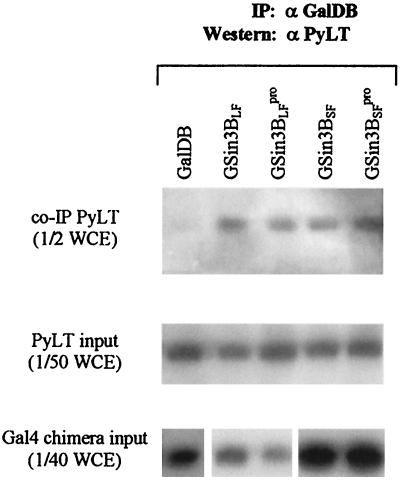

As mSin3B inhibits Py ori-core DNA replication in an HDAC-independent manner, a likely alternative mechanism is its interacting with key replication proteins to modify their activities. To assess whether mSin3B interacts with PyLT, NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids for PyLT and Gal4 fusion proteins, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GalDB antibody, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-T antisera. PyLT associated with all four forms of Gal4 mSin3B protein, but not with GalDB alone (Fig. 6, top panel). Expression of PyLT and Gal4 fusion proteins was comparable (Fig. 6, middle and bottom panels).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of PyLT coimmunoprecipitated with Gal4 fusion mSin3B. Cells extracts from NIH 3T3 cells transiently cotransfected with expression vector for PyLT and one of the expression vectors for Gal4 fusion proteins incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-GalDB antibody are displayed. One-half of the immune complexes (top panel), equivalent to one-half of whole-cell extracts (WCE), one-fiftieth of WCE for measurement of input PyLT (middle panel), and one-fortieth of WCE for measurement of input Gal4 chimera (bottom panel) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-PyLT antisera and rabbit polyclonal anti-GalDB antibody. Gal4 chimera transfected are indicated above lane. α PyLT, anti-PyLT antibody; α GalDB, anti-GalDB antibody.

This interaction is possibly required for mSin3B to inhibit PyLT and thus DNA replication. Since mSin3BSFpro also interacts with PyLT but slightly promotes Py ori-core DNA replication, additional components such as N-CoR/SMRT might be needed for mSin3B to inhibit PyLT function in replication.

DISCUSSION

Transcription factors bound to the enhancer adjacent to the Py ori-core can both activate and repress transcription, and mSin3B complexes are likely to be required for the latter. For example, resistance of F9 undifferentiated embryonal carcinoma cells to Py infection has been suggested to be due to a cell-specific transcriptional repressor bound to the enhancer (70, 77, 89). YY1/NF-D and c/EBP, which have binding sites within the Py enhancer (11, 52, 53), function as both activators and repressors of transcription (52, 63, 72, 75). c-Ets-1 can abolish c-Jun-stimulated transcription in a construct containing the PEA3/AP1 element of the Py enhancer (27). PEA2 and PEA3 have repressor-like activities on late transcription under nonreplicating conditions (76). Py tumor antigens also may repress early gene expression at late times (20) and late gene expression at early times (9). Many members of protein families that bind the Py enhancer have been found to interact with Sin3-HDAC corepressor complex (94, 96).

What functions might these repressor activities play in the viral life cycle? The repressor activities of transcription factors may participate in the early to late switch of transcription in the lytic cycles of Py and SV40 (49, 91): when late gene expression is activated, repressor complexes might be disassociated from transcription factors and replaced by activator complexes containing histone acetyltransferase activities. This might be achieved by titration through replicating viral DNA (49, 91, 97) or by direct modification of transcription factors or repressor complexes through middle T- and/or small t-mediated signaling (13). Similar control may be exerted upon DNA replication during the viral life cycle. DNA replication of many small DNA tumor viruses switches from a uniquely theta mode to rolling-circle replication, perhaps to improve replication efficiency (6, 16, 22, 64) and to enhance late RNA synthesis (12). Inhibition of initiation at the viral origin for theta mode replication by repressors such as mSin3B might facilitate such switching. Also, inhibition of theta mode replication, along with availability of replication and maturation proteins, is likely to facilitate the removal of viral DNA from pools susceptible to rereplication and thus promote the initiation of virion assembly (66, 67, 87, 88).

The following observations indicate that mSin3B inhibits Py ori-core DNA replication when tethered adjacent to the origin, and the inhibition is HDAC independent: (i) mSin3BSF lacking the ability to bind class I histone deacetylases HDAC1 and -2 inhibits Py ori-core DNA replication; (ii) TSA, a specific HDAC inhibitor, does not specifically relieve inhibition of Py ori-core DNA replication by mSin3B; (iii) direct tethering of HDACs (HDAC1, -2, -5, and -7) near the Py origin has no effect on Py ori-core DNA replication; (v) no significant deacetylation around the Py ori-core is detected in cells expressing Gal4 fusion mSin3B; and (iv) SMRT repressive domain 3 (RD3), which requires HDAC4/5/7's interaction to repress transcription (37), did not inhibit Py ori-core DNA replication (data not shown).

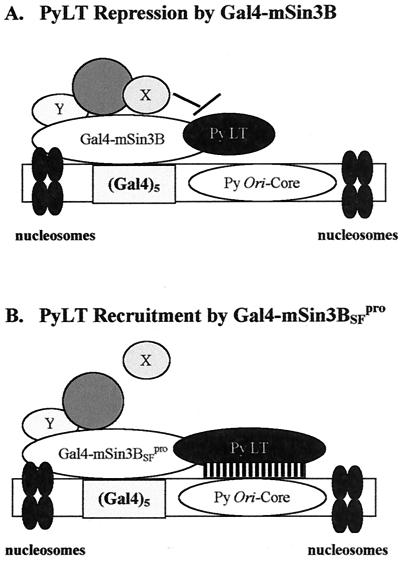

The mSin3B interaction with PyLT provides a possible mechanism for the inhibition of Py ori-core DNA replication. That the mSin3BL59P mutation, which impairs the interaction with the corepressor N-CoR/SMRT (2), abolishes mSin3B inhibition of Py ori-core DNA replication suggests participation of N-CoR/SMRT in this inhibition. The slight stimulation of Py ori-DNA replication by mSin3BSFpro might be explained by its capacity to interact with PyLT and thereby recruit LT to the origin, as occurs with c-Jun and VP16 (30, 33, 39; O. Kenzior, B. Ulmasov, and W. R. Folk, unpublished data). Although N-CoR/SMRT directly interacts with HDAC3 (28, 29, 48, 90) and class II histone deacetylases HDAC4/5/7 (37, 42), it is likely that other non-HDAC proteins, including N-CoR/SMRT, may be recruited by mSin3B to inhibit PyLT function in DNA replication (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Possible roles of mSin3B in Py ori-core DNA replication. (A) Schematic suggesting mSin3B interacts with PyLT and uses repressive activities or components (X) other than HDACs to repress activity of PyLT, thereby inhibiting Py ori-core DNA replication. (B) mSin3BSFpro, one of L59P mutants, lacks repression possibly due to disrupted interaction with components (X), including N-CoR/SMRT. Recruitment of PyLT through interaction instead helps stimulate DNA replication.

We recognize that negative evidence that HDAC proteins are not involved in repression of Py replication cannot be conclusive. Acetylation of PyLT appears to be important for DNA replication (93), and hence, a novel or TSA-resistant HDAC activity that deacetylates PyLT might be involved in the repression we have observed here. Biochemical fractionation of the Sin3 complexes and use of acetylated LT as a substrate might reveal such activities.

HDACs are components of heterochromatin (38, 47, 78). Together with other heterochromatin proteins that associate with ORC subunits (23, 24, 60, 74, 84), they may help establish repressive heterochromatin structures around cellular origins and thus determine the timing of initiation (17, 21, 25, 54, 80); for example, Sir4, a major component of heterochromatin, when tethered near a yeast origin by Gal4 binding sites, delays the initiation of this origin (101). It is possible that mSin3B repression of DNA replication might also function in the selection of cellular origins and the determination of late firing or silent cellular origins. The mSin3B inhibition of Py ori-DNA replication might thus serve as model for repressors utilized to assist selection of initiation sites and replication timing in response to specific cellular signals in eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Folk laboratory for helpful and insightful discussions and Sarah Scanlon for her invaluable support and assistance. We also thank R. A. Depinho for expression vectors for mSin3B; R. M. Evans for pMH100-TK-luc, pCMX-GalHDAC5, and pCMX-GalHDAC7; E. Seto for pGalHDAC1 and -2; and M. A. Lazar for pCMX-GalNCoR-RD1 and pCMX-GalSMRT-RD3.

This work was supported by NIH grant CA38538 and in part by U.S. Army grant DAMD17-98-1-8321.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexiadis, V., L. Halmer, and C. Gruss. 1997. Influence of core histone acetylation on SV40 minichromosome replication in vitro. Chromosoma 105:324-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alland, L., R. Muhle, H. Hou, J. Potes, L. Chin, N. Schreiber-Agus, and R. A. Depinho. 1997. Role for N-CoR and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 387:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin, A. A., Y. Murakami, and J. Hurwitz. 1994. Initiation of DNA replication by simian virus 40 T antigen is inhibited by the p107 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7735-7743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayer, D. E. 1999. Histone deacetylases: transcriptional repression with Siners and NuRDs. Trends Cell Biol. 9:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett-Cook, E. R., and J. A. Hassell. 1991. Activation of polyomavirus DNA replication by yeast GAL4 is dependent on its transcriptional activation domains. EMBO J. 10:959-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjursell, G. 1978. Effects of 2′-deoxy-2′-azidocytidine on polyoma virus DNA replication: evidence for rolling circle-type mechanism. J. Virol. 26:136-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosco, G., W. Du, and T. L. Orr-Weaver. 2001. DNA replication control through interaction of E2F-RB and the origin recognition complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brehm, A., E. A. Miska, D. J. McCance, J. L. Reid, A. J. Bannister, and T. Kouzarides. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature 391:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cahill, K. B., and G. G. Carmichael. 1989. Deletion analysis of the polyomavirus late promoter: evidence for both positive and negative elements in the absence of early proteins. J. Virol. 63:3634-3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey, M. Y., Y. S. Lin, M. R. Green, and M. Ptashne. 1990. A mechanism for synergistic activation of a mammalian gene by GAL4 derivatives. Nature 345:361-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caruso, M., C. Iacobini, C. Passananti, A. Felsani, and P. Amati. 1990. Protein recognition sites in polyomavirus enhancer: formation of a novel site for NF-1 factor in an enhancer mutant and characterization of a site in the enhancer D domain. EMBO J. 9:947-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, L., and M. Fluck. 2001. Kinetic analysis of the steps of the polyomavirus lytic cycle. J. Virol. 75:8368-8379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, L., and M. M. Fluck. 2001. Role of middle T-small T in the lytic cycle of polyomavirus: control of the early-to-late transcriptional switch and viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 75:8380-8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox, L. S., T. Hupp, T., C. A. Midgley, and D. P. Lane. 1995. A direct effect of activated human p53 on nuclear DNA replication. EMBO J. 14:2099-2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cress, W. D., and E. Seto. 2000. Histone deacetylases, transcriptional control, and cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 184:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deichaite, I., Z. Laver-Rudich, D. Dorsett, and E. Winocour. 1985. Linear simian virus 40 DNA fragments exhibit a propensity for rolling-circle replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:1787-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DePamphilis, M. L. 1999. Replication origins in metazoan chromosomes: fact or fiction? Bioessays 21:5-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downes, M., P. Ordentlich, H. Y. Kao, J. G. Alvarez, and R. M. Evans. 2000. Identification of a nuclear domain with deacetylase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10330-10335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutta, A., J. M. Ruppert, J. C. Aster, and E. Winchester. 1993. Inhibition of DNA replication factor RPA by p53. Nature 365:79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmerie, W. G., and W. R. Folk. 1984. Regulation of polyomavirus transcription by large tumor antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:6919-6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson, B. M., and W. L. Fangman. 1992. A position effect on the time of replication origin activation in yeast. Cell 68:333-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flores, E. R., and P. F. Lambert. 1997. Evidence for a switch in the mode of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA replication during the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 71:7167-7179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox, C. A., A. E. Ehrenhofer-Murray, S. Loo, and J. Rine. 1997. The origin recognition complex, SIR1, and the S phase requirement for silencing. Science 276:1547-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner, K. A., and C. A. Fox. 2001. The Sir1 protein's association with a silenced chromosome domain. Genes Dev. 15:147-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert, D. M. 2001. Making sense of eukaryotic DNA replication origins. Science 294:96-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert, D. M., A. Neilson, H. Miyazawa, M. L. DePamphilis, and W. C. Burhans. 1995. Mimosine arrests DNA synthesis at replication forks by inhibiting deoxyribonucleotide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 270:9597-9606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg, Y., M. Treier, J. Ghysdael, and D. Bohmann. 1994. Repression of AP-1-stimulated transcription by c-Ets-1. J. Biol. Chem. 269:16566-16573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guenther, M. G., O. Barak, and M. A. Lazar. 2001. The SMRT and N-CoR corepressors are activating cofactors for histone deacetylase 3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6091-6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guenther, M. G., W. S. Lane, W. Fischle, E. Verdin, M. A. Lazar, and R. Shiekhattar. 2000. A core SMRT co-repressor complex containing HDAC3 and TBL1, a WD40-repeat protein linked to deafness. Genes Dev. 14:1048-1057. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo, W., W. J. Tang, X. Bu, V. Bermudez, M. Martin, and W. R. Folk. 1996. AP1 enhances polyomavirus DNA replication by promoting T-antigen-mediated unwinding of DNA. J. Virol. 70:4914-4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harbour, J. W., and D. C. Dean. 2000. The Rb/E2F pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 14:2393-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassig, C. A., T. C. Fleischer, A. N. Billin, S. L. Schreiber, and D. E. Ayer. 1997. Histone deacetylase activity is required for full transcriptional repression by mSin3A. Cell 89:341-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He, Z., B. T. Brinton, J. Greenblatt, J. A. Hassell, and C. J. Ingles. 1993. The transactivator proteins VP16 and GAL4 bind replication factor A. Cell 73:1223-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinzel, T., R. M. Lavinsky, T. M. Mullen, M. Soderstrom, C. D. Laherty, J. Torchia, W. M. Yang, G. Brard, S. D. Ngo, and J. R. Davie. 1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermansen, R., M. A. Sierra, J. Johnson, M. Friez, and B. Milavetz. 1996. Identification of simian virus 40 promoter DNA sequences capable of conferring restriction endonuclease hypersensitivity. J. Virol. 70:3416-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirt, B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 26:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang, E. Y., J. Zhang, E. A. Miska, M. G. Guenther, T. Kouzarides, and M. A. Lazar. 2000. Nuclear receptor co-repressors partner with class II histone deacetylases in a Sin3-independent repression pathway. Genes Dev. 14:45-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imai, S., C. M. Armstrong, M. Kaeberlein, and L. Guarente. 2000. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403:795-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito, K., M. Asano, P. Hughes, H. Kohzaki, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, T. Kerppola, T. Curran, Y. Murakami, and Y. Ito. 1996. C-Jun stimulates origin-dependent DNA unwinding by polyomavirus large T antigen. EMBO J. 15:5636-5646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones, P. L., G. J. Veenstra, P. A. Wade, D. Vermaak, S. U. Kass, N. Landsberger, J. Strouboulis, and A. P. Wolffe. 1998. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat. Genet. 19:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadosh, D., and K. Struhl. 1998. Histone deacetylase activity of Rpd3 is important for transcriptional repression in vivo. Genes Dev. 12:797-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kao, H. Y., M. Downes, P. Ordentlich, and R. M. Evans. 2000. Isolation of a novel histone deacetylase reveals that class I and class II deacetylases promote SMRT-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 14:55-66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kijima, M., M. Yoshida, K. Sugita, S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1993. TRAPOXIN, an antitumor cyclic tetrapeptide, is an irreversible inhibitor of mammalian histone deacetylase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22429-22435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kingston, R. E. 1999. Chromatin assembly and analysis, p. 21.0.1-21.1.15. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 45.Laherty, C. D., W. M. Yang, J. M. Sun, J. R. Davie, E. Seto, and R. N. Eisenman. 1997. Histone deacetylases associated with the mSin3 co-repressor mediate mad transcriptional repression. Cell 89:349-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai, A., B. K. Kennedy, D. A. Barbie, N. R. Bertos, X. J. Yang, M. C. Theberge, S. C. Tsai, E. Seto, Y. Zhang, A. Kuzmichev, W. S. Lane, D. Reinberg, E. Harlow, and P. E. Branton. 2001. RBP1 recruits the mSin3-histone deacetylase complex to the pocket of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor family proteins found in limited discrete regions of the nucleus at growth arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2918-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Landry, J., A. Sutton, S. T. Tafrov, R. C. Heller, J. Stebbins, L. Pillus, and R. Sternglanz. 2000. The silencing protein SIR2 and its homologs are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5807-5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li, J., J. Wang, J. Wang, Z. Nawaz, J. M. Liu, J. Qin, and J. Wong. 2000. Both co-repressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. EMBO J. 19:4342-4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, Z., and G. G. Carmichael. 1993. Polyoma virus early-late switch: regulation of late RNA accumulation by DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8494-8498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo, R. X., A. A. Postigo, and D. C. Dean. 1998. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell 92:463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magnaghi-Jaulin, L., R. Groisman, I. Naguibneva, P. Robin, S. Lorain, J. P. Le Villain, F. Troalen, D. Trouche, and A. Harel-Bellan. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature 391:601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martelli, F., C. Iacobini, M. Caruso, and A. Felsani. 1996. Characterization of two novel YY1 binding sites in the polyomavirus late promoter. J. Virol. 70:1433-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin, M. E., J. Piette, M. Yaniv, W. J. Tang, and W. R. Folk. 1988. Activation of the polyomavirus enhancer by a murine activator protein 1 (AP1) homolog and two contiguous proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:5839-5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mechali, M. 2001. DNA replication origins: from sequence specificity to epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:640-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller, S. D., G. Farmer, and C. Prives. 1995. p53 inhibits DNA replication in vitro in a DNA-binding-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6554-6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murphy, M., J. Ahn, K. K. Walker, W. H. Hoffman, R. M. Evans, A. J. Levine, and D. L. George. 1999. Transcriptional repression by wild-type p53 utilizes histone deacetylases, mediated by interaction with mSin3a. Genes Dev. 13:2490-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagy, L., H. Y. Kao, D. Chakvarkti, R. J. Lin, C. A. Hassig, D. E. Ayer, S. L. Schreiber, and R. M. Evans. 1997. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3a, and histone deacetylase. Cell 89:373-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nan, X., H. H. Ng, C. A. Johnson, C. D. Laherty, B. M. Turner, R. N. Eisenman, and A. Bird. 1998. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 393:386-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ng, H. H., and A. Bird. 2000. Histone deacetylases: silencers for hire. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pak, D., M. Pflumm, I. Chesnokov, D. Huang, R. Kellum, J. Marr, P. Romanowski, and M. Botchan. 1997. Association of the origin recognition complex with heterochromatin and HP1 in higher eukaryotes. Cell 91:311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pallas, D. C., C. Schley, M. Mahoney, E. Harlow, B. S. Schaffhausen, and T. M. Roberts. 1986. Polyomavirus small T antigen: overproduction in bacteria, purification, and utilization for monoclonal and polyclonal antibody production. J. Virol. 60:1075-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peden, K. W., J. M. Pipas, S. Pearson-White, and D. Nathans. 1980. Isolation of mutants of an animal virus in bacteria. Science 209:1392-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pei, D. Q., and C. H. Shih. 1990. Transcriptional activation and repression by cellular DNA-binding protein C/EBP. J. Virol. 64:1517-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pfuller, R., and W. Hammerschmidt. 1996. Plasmid-like replicative intermediates of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic origin of DNA replication. J. Virol. 70:3423-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reynisdottir, I., S. Bhattacharyya, D. Zhang, and C. Prives. 1999. The retinoblastoma protein alters the phosphorylation state of polyomavirus large T antigen in murine cell extracts and inhibits polyomavirus origin DNA replication. J. Virol. 73:3004-3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roman, A. 1979. Kinetics of reentry of polyoma progeny form I DNA into replication as a function of time postinfection. Virology 96:660-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roman, A., and R. Dulbecco. 1975. Fate of polyoma form I DNA during replication. J. Virol. 16:70-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Royzman, I., R. J. Austin, G. Bosco, S. P. Bell, and T. L. Orr-Weaver. 1999. ORC localization in Drosophila follicle cells and the effects of mutations in dE2F and dDP. Genes Dev. 13:827-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanchez, J. A., D. Marek, and L. J. Wangh. 1992. The efficiency and timing of plasmid DNA replication in Xenopus eggs: correlations to the extent of prior chromatin assembly. J. Cell Sci. 103:907-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sassone-Corsi, P., C. Fromental, and P. Chambon. 1987. A trans-acting factor represses the activity of the polyoma virus enhancer in undifferentiated embryonal carcinoma cells. Oncogene Res. 1:113-119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schreiber-Agus, N., and R. A. Depinho. 1998. Repression by the Mad(Mxi1)-Sin3 complex. Bioessays 20:808-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seto, E., Y. Shi, and T. Shenk. 1991. YY1 is an initiator sequence-binding protein that directs and activates transcription in vitro. Nature 354:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shadan, F. F., L. M. Cowsert, and L. P. Villarreal. 1994. N-Butyrate, a cell cycle blocker, inhibits the replication of polyomaviruses and papillomaviruses but not that of adenoviruses and herpesviruses. J. Virol. 68:4785-4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shareef, M. M., C. King, M. Damaj, R. Badagu, D. W. Huang, and R. Kellum. 2001. Drosophila heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1)/origin recognition complex (ORC) protein is associated with HP1 and ORC and functions in heterochromatin-induced silencing. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:1671-1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi, Y., E. Seto, L. S. Chang, and T. Shenk. 1991. Transcriptional repression by YY1, a human GLI-Kruppel-related protein, and relief of repression by adenovirus E1A protein. Cell 67:377-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shivakumar, C. V., and G. C. Das. 1998. The A enhancer of polyomavirus: protein-protein interactions for the differential early and late promoter function under nonreplicating conditions. Intervirology 41:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sleigh, M. J., T. J. Lockett, J. Kelly, and D. Lewy. 1987. Competition studies with repressors and activators of viral enhancer function in F9 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:4307-4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith, J. S., C. B. Brachmann, I. Celic, M. A. Kenna, S. Muhammad, V. J. Starai, J. L. Avalos, J. C. Escalante-Semerena, C. Grubmeyer, C. Wolberger, and J. D. Boeke. 2000. A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6658-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sterner, J. M., S. Dew-Knight, C. Musahl, S. Kornbluth, and J. M. Horowitz. 1998. Negative regulation of DNA replication by the retinoblastoma protein is mediated by its association with MCM7. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2748-2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stevenson, J. B., and D. E. Gottschling. 1999. Telomeric chromatin modulates replication timing near chromosome ends. Genes Dev. 13:146-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Struhl, K. 1998. Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev. 12:599-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sturzbecher, H. W., R. Brain, T. Maimets, C. Addison, K. Rudge, and J. R. Jenkins. 1988. Mouse p53 blocks SV40 DNA replication in vitro and downregulates T antigen DNA helicase activity. Oncogene 3:405-413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tang, W. J., and W. R. Folk. 1989. Asp-286-Asn-286 in polyomavirus large T antigen relaxes the specificity of binding to the polyomavirus origin. J. Virol. 63:242-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Triolo, T., and R. Sternglanz. 1996. Role of interactions between the origin recognition complex and Sir1 in transcriptional silencing. Nature 381:251-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wada, M., H. Miyazawa, R. S. Wang, T. Mizuno, A. Sato, M. Asashima, and F. Hanaoka. 2002. The second largest subunit of mouse DNA polymerase epsilon, DPE2, interacts with SAP18 and recruits the Sin3 co-repressor protein to DNA. J. Biochem. 131:307-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang, E. H., P. N. Friedman, and C. Prives. 1989. The murine p53 protein blocks replication of SV40 DNA in vitro by inhibiting the initiation functions of SV40 large T antigen. Cell 57:379-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang, H. T., and A. Roman. 1981. Cessation of reentry of simian virus 40 DNA into replication and its simultaneous appearance in nucleoprotein complexes of the maturation pathway. J. Virol. 39:255-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang, H. T., S. H. Larsen, and A. Roman. 1985. A cis-acting sequence promotes removal of simian virus 40 DNA from the replication pool. J. Virol. 53:410-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wasylyk, B., J. L. Imler, B. Chatton, C. Schatz, and C. Wasylyk. 1988. Negative and positive factors determine the activity of the polyoma virus enhancer α domain in undifferentiated and differentiated cell types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:7952-7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wen, Y. D., V. Perissi, L. M. Staszewski, W. M. Yang, A. Krones, C. K. Glass, M. G. Rosenfeld, and E. Seto. 2000. The histone deacetylase-3 complex contains nuclear receptor co-repressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7202-7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wiley, S. R., R. J. Kraus, F. Zuo, E. E. Murray, K. Loritz, and J. E. Mertz. 1993. SV40 early-to-late switch involves titration of cellular transcriptional repressors. Genes Dev. 7:2206-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wong, C. W., and M. L. Privalsky. 1998. Transcriptional repression by the SMRT-mSin3 co-repressor: multiple interactions, multiple mechanisms, and a potential role for TFIIB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5500-5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xie, A-Y, V. P. Bermudez, and W. R. Folk. 2002. Stimulation of DNA replication from the polyomavirus origin by PCAF and GCN5 acetyltransferases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7907-7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang, W. M., C. Inouye, Y. Zeng, D. Bearss, and E. Seto. 1996. Transcriptional repression by YY1 is mediated by interaction with a mammalian homolog of the yeast global regulator RPD3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:12845-12850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang, W. M., Y. L. Yao, J. M. Sun, J. R. Davie, and E. Seto. 1997. Isolation and characterization of cDNAs corresponding to an additional member of the human histone deacetylase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28001-28007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang, S. H., E. Vickers, A. Brehm, T. Kouzarides, and A. D. Sharrocks. 2001. Temporal recruitment of the mSin3A-histone deacetylase co-repressor complex to the ETS domain transcription factor Elk-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2802-2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yoo, W., M. E. Martin, and W. R. Folk. 1991. PEA1 and PEA3 enhancer elements are primary components of the polyomavirus late transcription initiator element. J. Virol. 65:5391-5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yoshida, M., M. Kijima, M. Akita, and T. Beppu. 1990. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17174-17179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoshida, M., S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1995. Trichostatin A and trapoxin: novel chemical probes for the role of histone acetylation in chromatin structure and function. Bioessays 17:423-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yu, F., J. Thiesen, and W. H. Stratling. 2000. Histone deacetylase-independent transcriptional repression by methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2201-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zappulla, D. C., R. Sternglanz, and J. Leatherwood. 2002. Control of replication timing by a transcriptional silencer. Curr. Biol. 12:869-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang, Y., R. Iratni, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and D. Reinberg. 1997. Histone deacetylases and SAP18, a novel polypeptide, are components of a human Sin3 complex. Cell 89:357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zilfou, J. T., W. H. Hoffman, M. Sank, D. L. George, and M. Murphy. 2001. The co-repressor mSin3A interacts with the proline-rich domain of p53 and protects p53 from proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3974-3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]