Summary

Some AIDS researchers and activists have criticized public health efforts to warn communities of a possible new strain of HIV

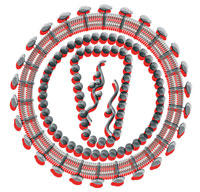

In mid-February this year, New York City Health Commissioner Thomas Frieden called a press conference to announce that a case of rapidly progressing, multidrug-resistant HIV/AIDS had been identified. Although drug resistance is common, and rapid progression to AIDS is rare but not unheard of, it is the combination of both factors in one patient that raised the fear among public health officials that a new, particularly virulent 'super-strain' of HIV/ AIDS had emerged. The virus, described in March by Martin Markowitz and colleagues at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York (Markowitz et al, 2005), where the patient was referred, was deemed to be replication-competent in vitro—unusual for a resistant form—and had other features rarely seen in a newly diagnosed patient. The patient, a gay man in his 40s who had had unprotected sex with scores of partners, had been infected anywhere from 4 to 20 months before his diagnosis in December 2004.

So far, none of the patient's partners have been found to have the same strain, according to an update issued April 1, but laboratories performing resistance testing have identified several patients whose strains may be related. In the meantime, the patient is responding to a complex course of drug treatment. Testing of his sexual contacts is ongoing, and may take weeks to months to complete, according to the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

At the press conference, Frieden used strong language to warn of the possibility of a new strain of HIV, and of risky behaviour among homosexual men that could encourage its spread. “This case is a wake-up call to men who have sex with men, particularly those who may use crystal methamphetamine,” he said, referring to the patient's use of the drug to improve his sexual experience. His comments unleashed a torrent of criticism among some researchers, clinicians and AIDS activists, who believe that the case was prematurely publicized without sufficient facts, and that the announcement was unnecessarily alarming and stigmatizing of the gay community. As well as stirring up long-standing issues of public health policy, the event has heightened emotions about AIDS at a time when HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases are once again on the rise.

Several critics said that if this case turned out to be an anomaly...it would be like the boy who cried 'wolf'...

“Some felt that stating that this case represents a new 'strain' is ripe for misunderstanding,” said Richard Jefferys, basic science project director at the Treatment Action Group, an advocacy group in New York City. Robert Gallo, co-discoverer of the AIDS virus and director of the Institute for Human Virology (Baltimore, MD, USA) had even stronger words: “This is not a discovery, and releasing the information at a press conference is not normal science.” In fact, it is not yet clear whether this case amounts to a deadly new strain or not. Whereas the average time for untreated HIV to progress to AIDS is about a decade, about 1%–3% of HIV/AIDS patients are rapid progressors and about 8%–20% of patients are already resistant to one drug when diagnosed. Although this patient had none of the approximately 20 known genetic characteristics that would make him a rapid progressor, other unknown factors might produce a host–virus interaction that could lead to rapid decline, some researchers said. “This case did not come as a surprise,” noted Cal Cohen, Research Director of the Community Research Initiative of New England (Boston, MA, USA), a community-based treatment and research group. “We don't know if this case is a result of a bad virus, the patient's genetics or life choices [use of methamphetamine and unprotected sex],” he added. “But if it happened to him, it could happen to others.”

In fact, Julio Montaner, head of the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS in Vancouver, Canada, reported two similar cases in 2003 (Chan et al, 2003). “What bothers me about [Frieden's] report is not that it didn't mention our earlier experience, but that the message seems to be 'now we really have to be careful about AIDS', as if the regular virus was not bad enough,” Montaner said. “We shouldn't be fear-mongering on the basis of a possible super-bug; we must protect against HIV, period.”

Much of the criticism has therefore focused on the way Frieden announced the case. “[The announcement] characterized the patient as a sex- and drug-crazed addict, and sought to create a new fear-based message,” said Howard Grossman, Executive Director of the American Academy of HIV Medicine, an organization of physicians who specialize in HIV/AIDS care. “We're beyond fear; it's not like in the 1980s, when we didn't know that much about AIDS, when fear created changes in behaviour. At this point, the community can't sustain more fear—it will boomerang.” Several critics said that if this case turned out to be an anomaly, like the Vancouver cases, it would be like the boy who cried 'wolf'—when there is a real emergency, no one will listen.

Part of the problem...was that at the early stage of the epidemic, public health authorities adopted politically correct language, or 'AIDSpeak', to discuss the epidemic without insulting anyone...

However, not everyone was critical of Frieden for releasing early information on a case that many consider disturbing. “Had Tom Frieden not alerted the community to a possible novel, more difficult-to-treat strain of the virus, and it spread, the AIDS community would have had his head on a platter,” said Mervyn Silverman, former president of the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AmfAR; New York, NY, USA). Silverman has a unique perspective: as Director of Public Health in San Francisco at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, he was among the first to confront the public health challenge of the emerging virus among the city's large gay community. Before the cause of the disease was eventually identified as a retrovirus that was transmitted sexually and through blood, Silverman had the responsibility of developing public service announcements about safer sex and drug use, and ultimately, he closed the bathhouses in the city.

In his chronicle of the early days of the epidemic, And the Band Played On, Randy Shilts observed that Silverman was well liked in the city, but that he acted too slowly in the interest of not offending his constituencies (Shilts, 1987). “At last, a local public health official had said that AIDS was an extraordinary situation requiring extraordinary action. Political rhetoric bowed to biological reality; saving lives was more important than saving face,” Shilts wrote. “What made the San Francisco [bathhouse] closure so anticlimactic, however, was that it came so late...by the time the baths were closed and a truly comprehensive education program was started in San Francisco, about two-thirds of the local gay men destined to be infected...already carried the virus. The health officials who...defended their inaction in New York and Los Angeles were...acknowledging that, in truth they could have closed the barn door before the horses galloped out. Instead, they did nothing, letting infection run loose and defending further inaction by saying it was too late to do anything, because infection was already loose in the land. Later, everybody agreed the baths should have been closed sooner...”

Part of the problem, according to Shilts, was that at the early stage of the epidemic, public health authorities adopted politically correct language, or 'AIDSpeak', to discuss the epidemic without insulting anyone, but this was ineffective in changing behaviour. “With politicians talking like public health officials, and public health officials behaving like politicians, the new vernacular allowed virtually everyone to avoid challenging the encroaching epidemic in medical terms,” Shilts wrote.

Some suspect that Frieden was blasted because he was direct in sharing potentially important information and attempting to change high-risk behaviour rather than using AIDSpeak at his press conference. And he might be correct, given that public health officials are increasingly concerned about a return to riskier sexual practices and drug abuse in the gay community (Boddiger, 2005; van der Snoek et al, 2005). Nevertheless, Julie Davids, Executive Director of the Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization Project (New York, NY, USA) thinks it was overkill: “Frieden's message sounded vaguely punitive. There's a feeling that it was an attempt to bully the gay community into having safe sex.” She and others in the AIDS activist community would have preferred if he had waited for more information and, in the meantime, alerted physicians to the case.

Frieden knows something about combating infectious diseases. As New York City's Assistant Commissioner of Health for Tuberculosis Control in the early 1990s, he battled skyrocketing rates of difficult-to-treat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Frieden fought to secure funding for 'directly observed therapy', a labour-intensive and expensive public health measure ensuring that patients consistently take a complex regimen of antibiotics for six months to two years or longer until they are infection-free. If a patient was not drug-compliant, he or she could be legally detained. By dealing swiftly and effectively, Frieden was able to bring MDR-TB infection rates to an all-time low. Similar to HIV/AIDS, the MDR-TB epidemic involved sensitive issues: many patients were poor, immigrants, drug addicts and/or infected with HIV/AIDs, which required the city to deal deliberately but tactfully without stigmatizing these populations. But some AIDS activists see Frieden's interest in stemming the spread of a potentially more resistant and rapidly progressing form of HIV/AIDS as ominous.

As part of his current efforts, Frieden issued a health alert to doctors and hospitals to test all newly diagnosed patients for anti-HIV drug susceptibility, and is developing a long-term monitoring system with the state. He has contacted labs to find similar cases of drug-resistant HIV/AIDS infection in newly diagnosed patients, and is asking physicians to do more HIV prevention counselling and testing. He is also trying to improve the notification of partners of HIV-infected patients, and the monitoring of treatment and drug resistance, and is reportedly considering mandatory reporting of drug resistance, and making HIV/AIDS testing routine.

However, Davids, Jefferys and other AIDS activists object to this and other measures, and maintain that HIV/AIDS cannot be dealt with using the same approaches that are used to combat TB and other infectious diseases. Instead, they would prefer to have the state and city monitor physician prescription patterns, rather than tracking patients themselves. “Do we want to invite scrutiny of patients?” asked Davids. In a press release, the Gay Men's Health Crisis also expressed concern that Frieden's announcement “occurred at a time when HIV prevention efforts in the US are seriously underfunded and increasingly censored...when the federal government is shifting focus toward HIV prevention initiatives that are increasingly based on scientifically discredited abstinence-only approaches, and moving away from effective primary prevention work. [...] Research on sexuality and drug use has been under increasing attack by federal government officials” (GMHC, 2005).

But it is not only the federal government who are on the attack. Last year, a right-wing US-based church group, the Traditional Values Coalition (TVC; Washington, DC, USA) drew up what some called a 'hit list' of more than 150 publicly funded scientists who were conducting behavioural research on HIV/AIDS transmission (Brower, 2004). Calling the work “prurient”, “smarmy” and “provocative”, the Coalition pressured the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Bethesda, MD, USA) and Congress to justify the research, much of which dealt with the motivation behind high-risk behaviour. The TVC asked NIH Director Elias Zerhouni to provide a written explanation for several grants, according to an official at AmfAR.

There are also questions, and controversy, as to how illegal drug use might have a role in rapid disease progression or drug resistance

However, Cohen and others maintain that research on risk-taking behaviour and psychosocial factors is exactly what is needed to develop effective prevention measures. There are also questions, and controversy, as to how illegal drug use might have a role in rapid disease progression or drug resistance. In addition to its role in the rise of unsafe sex and its impact on neurocognitive health, some research indicates that methamphetamines may affect the immune system by modifying inflammatory cytokine expression and may have additive effects with HIV on brain metabolite abnormalities (Rippeth et al, 2004; Chang et al, 2005). Other evidence indicates that these commonly used drugs may interfere with anti-viral medicines (Ellis et al, 2003).

More information and time is needed to tell whether the New York City case is a harbinger of a more resistant, virulent type of HIV/AIDS, or whether it is an anomaly. “The existence of a cluster of such cases would help determine whether this is a unique virus–host interaction or a new virus type,” said AIDS researcher John Moore, from Cornell University's Weill Medical College (New York, NY, USA). “It is also possible that this case may represent a superinfection or dual infection, which a complete sequence of the virus would clarify.” Moore and others noted that in vitro replication competence would not predict how easily the virus is transmitted among humans. “I am among those considering that this 'superbug' is unlikely to be transmitted at a high frequency, and if transmitted, will have a completely different biological behaviour in a second host,” said Luc Perrin, a virologist at the Geneva University Hospital in Switzerland, who recently showed that drug-resistant viruses are transmitted with a lower efficiency than wild-type (Jost et al, 2002).

Since the beginning of the AIDS crisis, we may have come full circle. As Shilts described, public health and government officials failed to act proactively to stem the spread of HIV in the early 1980s. However, activists are now criticizing Frieden for doing just that. What is undisputed, though, is that HIV infection is on the rise again, due in part to an increase in unprotected sex and drug use. “We will see more of these cases, though I doubt we have an epidemic in the making,” Montaner predicted.

References

- Boddiger D (2005) Metamphetamine use linked to rising HIV transmission. Lancet 365: 1217–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower V (2004) List of 'prurient' research stirs fear, anger among US scientists. Nat Med 10: 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KC, Galli RA, Montaner JS, Harrigan PR (2003) Prolonged retention of drug resistance mutations and rapid disease progression in the absence of therapy after primary HIV infection. AIDS 17: 1256–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Speck O, Grob CS (2005) Additive effects of HIV and chronic methamphetamine use on brain metabolite abnormalities. Am J Psychiatry 162: 361–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Childers ME, Chermer M, Lazzaretto D, Letendre S, Grant I; HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group (2003) Increased human immunodeficiency virus loads in active methamphetamine users are explained by reduced effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 188: 1820–1826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GMHC (2005) MDR HIV case: where we stand. Press release, 23 Feb. www.gmhc.org

- Jost S, Bernard MC, Kaiser L, Yerly S, Hirschel B, Samri A, Autran B, Goh LE, Perrin L (2002) A patient with HIV-1 superinfection. N Engl J Med 347: 731–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz M et al. (2005) Infection with multidrug resistant, dual-tropic HIV-1 and rapid progression to AIDS: a case report. Lancet 365: 1031–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Gonzalez R, Wolfson T, Grant I; HNRC Group (2004) Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. J Int Neuropsych Soc 10: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilts R (1987) And the Band Played On. New York, NY, USA: St Martin's Press [Google Scholar]

- van der Snoek EM, de Wit JB, Mulder PG, van der Meijden WI (2005) Incidence of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection related to perceived HIV/AIDS threat since highly active antiretroviral therapy availability in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 32: 170–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]